Abstract

Intracellular, protozoan parasites are responsible for wide-spread infectious diseases. These unicellular pathogens have complex, multi-host life cycles, which present challenges for investigating their basic biology and for discovering vulnerabilities that could be exploited for disease control. Throughout development, parasite proteomes are dynamic and support stage-specific functions, but detection of these proteins is often technically challenging and complicated by the abundance of host proteins. Thus, to elucidate key parasite processes and host-pathogen interactions, labeling strategies are required to track pathogen proteins during infection. Herein, we discuss the application of bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging and proximity-dependent labeling to broadly study protozoan parasites and include outlooks for future applications to study Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria. We highlight the potential of these technologies to provide spatiotemporal labeling with selective parasite protein enrichment, which could enable previously unattainable insight into the biology of elusive developmental stages.

Keywords: Plasmodium, Apicomplexan, Bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT), Proximity-dependent labeling

Introduction

Intracellular protozoan parasites survive by exploiting the resources of their host cell and evading immune responses. These single cell organisms remain a global burden to human health. Plasmodium species of the Apicomplexa phylum cause malaria, with >600,000 associated mortalities in 2021 [1]. Other Apicomplexan parasites, including Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium, as well as other protozoan parasites, such as Leishmania and Trypanosoma, are also responsible for human diseases [2]. These pathogens complete complex life cycles with distinct developmental stages, with many relying on vectors for transmission to human hosts. The Anopheles mosquito, for example, transmits Plasmodium to humans, where parasites complete an asymptomatic liver stage before progressing to a symptomatic blood infection [3]. In both stages, Plasmodium resides and replicates within a parasitophorous vacuole (PV), surrounded by the PV membrane (PVM), which provides protection and regulates nutrient and protein exchange, enabled by their translocon of export (PTEX) system [4,5]. Consequently, these parasites have dynamic proteomes that change throughout their life cycle and includes the active exchange of proteins with host cells [6,7].

To further understand the complex processes that support parasite survival, it is essential to resolve protein dynamics throughout infection. Mapping these protein fluxes requires the implementation of labeling strategies that can track and enrich pathogen proteins. Technologies that enable temporal or spatial control of protein labeling allow proteome and exportome analyses at distinct developmental stages and subcellular localizations, respectively. These capabilities are invaluable to define host-pathogen interactions, investigate parasite development, and aid in drug development studies. While many methods are developed and utilized in model systems, including some eukaryotes, protozoan parasites present numerous additional complications for study. As one example, low infection rates and the inability to isolate pathogen proteins from the abundance of host proteins can complicate analysis [8,9]. The selective lysis of host cells to enrich for parasites is feasible in some but not all instances, such as the Plasmodium blood and liver stages, respectively. Promisingly, development of sophisticated labeling strategies is allowing spatiotemporal resolution as well as selective enrichment of parasite proteins. The continued adaption of such methods provides much-needed routes to circumvent the inherent challenges associated with studying these protozoans to address questions critical to their pathogenesis. Concurrently, advances in mass spectrometry continue to increase sensitivity, allowing detection of low abundance proteins in complex mixtures (reviewed in depth [10-12]). Herein, we describe key principles and progress in adapting two such labeling techniques: bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT) and proximity-dependent labeling; to study protozoan parasites with an outlook on the potential of these technologies for understanding the biology of Plasmodium, the most lethal of these pathogens.

Bioorthogonal Non-Canonical Amino Acid Tagging (BONCAT)

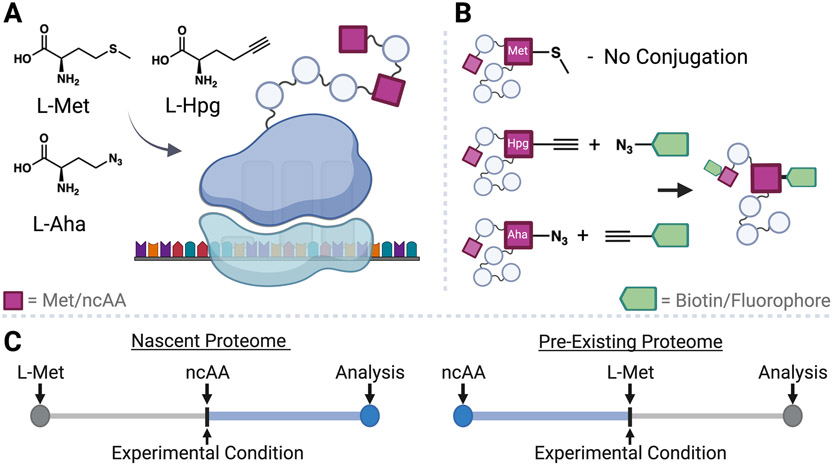

BONCAT has been leveraged as a valuable tool to label proteins as they are synthesized in diverse biological systems. BONCAT labeling is facilitated by replacing L-methionine (L-Met) in proteins with functionalized non-canonical amino acids (ncAA) [13]. Generally, L-azidohomoalanine (L-Aha) or L-homopropargylglycine (L-Hpg) are employed for global substitution, as they are incorporated into proteins during endogenous translation in organisms from every kingdom (Figure 1A) [13-15]. These surrogates contain an azide or alkyne moiety, respectively, enabling their conjugation to reporter tags via click chemistry (Figure 1B) [16]. Specifically, fluorescent tags allow for microscopy analysis or in-gel visualization, whereas biotin tags enable affinity purification and identification of labeled proteins with mass spectrometry (MS) [17,18]. This methodology is amenable to tracking the intracellular and exported proteome. For example, L-Aha labeling has been applied in Leishmania mexicana to identify newly synthesized proteins induced by starvation [19] and to validate exportation changes after retrograde transport inhibition [20]. Labeling is initiated by supplementing ncAA in place of L-Met; thus, it is employed like isotope pulse-chase experiments, but with the advantage of being non-radioactive and permitting protein enrichment. BONCAT affords temporal control of labeling, which is particularly beneficial to directly interrogate protein-level changes in relation to a stimulus, like environmental stressors and drug administrations.

Figure 1.

Global methionine substitution for bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT). (A) The non-canonical amino acids (ncAA) L-azidohomoalanine (L-Aha) or L-homopropargylglycine (L-Hpg) are incorporated in place of L-methionine (L-Met) at initiator and internal codon sites via endogenous translation in both translationally active host and parasite cells. (B) After incorporation into proteins, ncAA can be conjugated through a click chemistry ligation reaction between the azide handle of L-Aha and an alkyne-containing tag, or, conversely, the alkyne handle of L-Hpg and an azide-containing tag. Conjugation to biotin enables affinity purification of labeled proteins, which can be identified and quantified by mass spectrometry. Alternatively, conjugation to a fluorophore enables visualization of labeled proteins by gel electrophoresis or microscopy. (C) BONCAT enables temporal control over protein labeling based on the time of ncAA addition. Adding ncAA concurrent to an experimental treatment followed by analysis enables interrogation of the nascent proteome, whereas adding ncAA prior to its replacement with L-Met enables labeling of the pre-existing proteome.

As a notable example, BONCAT enabled temporal resolution of the L. mexicana promastigote (extracellular vector-stage) nascent proteome after inhibiting Hsp90, an essential molecular chaperone [21]. Parasites were initially grown with L-Met, which was replaced with L-Aha concurrent with Hsp90 inhibitor administration. After varying timeframes, labeled proteins were conjugated to biotin, isolated via affinity resin, and identified/quantified using a MS workflow. This approach specifically labeled newly translated proteins and measured differences resulting from Hsp90 inhibition. Analysis of this data revealed decreased production of ribosomal components, proposed to contribute to inhibitor lethality, and increased translation of Hsp90 itself and related chaperones, which is suggested as a compensatory response [21]. This study illustrates the potential of BONCAT to support mechanism of action and drug-induced adaptations in therapeutic development. While this study focused on the newly translated proteome, conducting ncAA labeling prior to inhibitor administration would enable interrogation of the pre-existing proteome (Figure 1C) [22,23]. Of note, these parasites have extensive post-transcriptional regulation that make mRNA transcript studies poor predictors of protein-levels [24] and Apicomplexa exhibit notable translational repression [6,25]. Thus, BONCAT is a powerful tool to directly measure global protein expression. Moreover, unlike endpoint proteome quantification, the robust temporal resolution of BONCAT can define the persistence of existing proteins or the production of new ones; such insights support a more comprehensive understanding on the timing and mechanism of proteome changes between conditions.

These BONCAT studies were conducted on axenic and extracellular Leishmania promastigotes, emphasizing a limitation in global methionine substitution: proteins from translationally active hosts will also be labeled. Thus, L-Aha and L-Hpg are useful when pathogen protein isolation is feasible or unnecessary. However, there is an ncAA incorporation bias in faster translating cells [26,27], which could be utilized in some instances to attain preferential labeling of pathogen proteins. In erythrocytic infections, host red blood cells are clear of translating ribosomes [28]. Correspondingly, L-Aha labeling has been successfully employed in the Plasmodium blood stage to monitor translation after N-myristoyltransferase inhibition [29]. Contrastingly, during hepatic infections, host translation could impede BONCAT studies. To date, it is uncertain whether fast replicating pathogens, like Plasmodium liver schizonts, would exhibit a labeling bias compared to their translationally active hosts that could be exploited to enable detection of their proteins. Regardless, the propensity to label both host and parasite proteins prohibits some applications of L-Aha and L-Hpg labeling in intracellular pathogens.

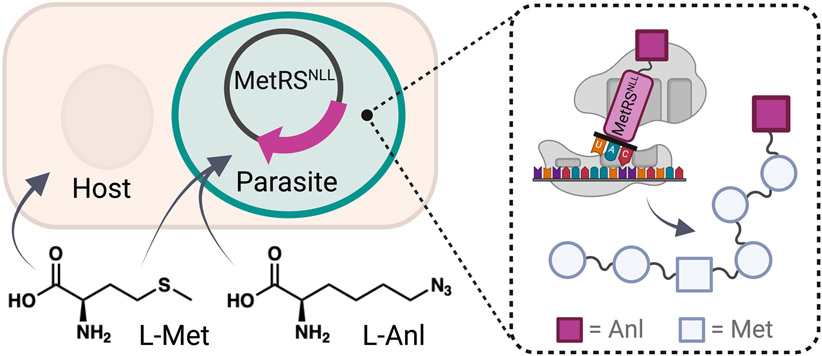

A particular BONCAT variant makes it possible to selectively label intracellular pathogen proteins by employing engineered methionyl-tRNA synthetases (MetRS) to charge ncAAs that are incompatible with endogenous translation (Figure 2) [30,31]. For this method, the bacterial-derived MetRSNLL is commonly employed to charge L-azidonorleucine (L-Anl), which contains an azide handle similar to L-Aha. Contrary to global methionine replacement, only cells expressing MetRSNLL will add L-Anl into their proteins [30,32], specifically at the initiator site in eukaryotes and without requiring methionine-deficient conditions [33,34]. L-Met is then incorporated as per usual at internal codons, in cells not expressing MetRSNLL, and in the absence of the ncAA. Thus, this method affords both cell-specific and temporal control. While not yet widely adopted in protozoan parasites, MetRSNLL has been successfully expressed and shown to incorporate L-Anl in Toxoplasma gondii as a proof-of-principle [34]. This study validated the utility of BONCAT to selectively label and isolate parasite proteins; however, enrichment of exported proteins was hindered due to their frequent N-terminal cleavage during export. Future developments could expand L-Anl incorporation at internal codons to enable tracking of parasite protein export. Overall, and further corroborated by successful implementation in diverse intracellular bacteria [35-37], this example demonstrates the ability of this technology to enable temporal resolution and specific enrichment of proteomes from challenging intracellular protozoan parasites across their developmental stages.

Figure 2.

Cell-specific incorporation of L-azidonorleucine (L-Anl). Parasite proteins can be specifically labeled with L-Anl by expression of a MetRSNLL synthetase in the pathogen. In eukaryotes, MetRSNLL charges initiator tRNA with L-Anl to facilitate its incorporation into proteins at the start codon. L-Met is incorporated at internal codons or in the absence of L-Anl. Since L-Anl is incompatible with endogenous translation, L-Met rather than L-Anl is also incorporated in host cells not expressing MetRSNLL.The L-Anl azide moiety enables biotin/fluorophore conjugation and downstream analysis with the advantage of cell-specific (parasite not host) incorporation.

Proximity-Dependent Labeling

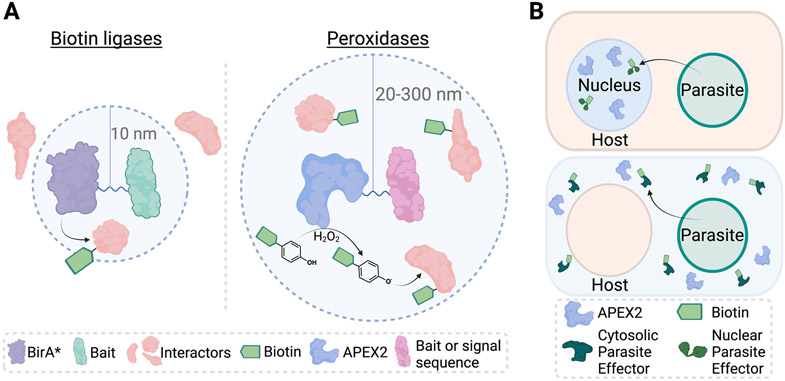

Proximity-dependent labeling that employs enzymes to biotinylate nearby proteins has emerged as a valuable method to map subcellular components and protein-protein interactions (reviewed in depth [38]). In BioID, a fusion protein consisting of the mutant biotin ligase BirA* linked to a protein of interest can be expressed to promiscuously label nearby (within ~10 nm) proteins after supplementing exogenous biotin (Figure 3A) [39,40]. BirA* covalently attaches biotin at lysine residues, enabling affinity enrichment and identification of labeled proteins. The linked ligases can label interactors of the fusion protein, or, alternatively, the linked protein of interest may target the biotin ligase to a cellular location (i.e., organelle, membrane, etc) to enable spatial labeling. The same methodology has been adapted with a smaller ligase termed BioID2, which is less likely to hinder the tagged protein’s function [41]. These approaches have been applied in T. gondii, as well as the Plasmodium blood and gametocyte stages [42-58].

Figure 3.

Mechanisms and applications for enzyme-based proximity biotinylation. (A) BirA* and its derivatives fused to a bait protein can use exogenous biotin to covalently tag nearby interacting proteins (within 10 nm) at lysine residues. Peroxidases like APEX2 can be fused to a bait protein or to a signal sequence to enable trafficking to different subcellular localizations. APEX2 enzymes use hydrogen peroxide and biotin phenol to form a phenoxyl radical, which readily reacts with nearby proteins at electron rich residues up to 300 nm away. Labeling radius for biotin ligases and peroxidases indicated (dashed circles). (B) APEX2 (in blue) can be expressed in the host nucleus (top) or host cytosol (bottom) to biotinylate parasite effectors in cells.

Notably, BioID was implemented to map components of the P. berghei blood stage PVM [47]. To localize the ligase, BirA* was fused to the PVM-resident protein EXP1, which identified 61 known and new PVM proteins. While the utility of this method has been demonstrated in diverse systems, this study showcased the power of BioID for spatial labeling at a host-pathogen interface. Recently, a novel dimerization-induced BioID variant was leveraged to study the link between Kelch13 and artiminisin resistance [59]. Kelch13 and BirA* were tagged with a FK506 binding protein or FKBP–rapamycin binding domain, respectively. Upon rapamycin analog addition, the ligase was recruited to Kelch13 to label nearby interactors. The method allows for conditional identification of interactors and can reduce false-positive results by comparing biotinylated proteins from samples treated with or without the dimerization-inducing molecule. Recent efforts in proximity labeling have focused on improving biotin ligase kinetics to enable detection of short-lived interactions, a limitation in BioID. TurboID was engineered to increase biotin affinity, where it is capable of labeling in 5-10 minutes what BioID accomplishes in 15-18 hours [60]. Unfortunately, TurboID can also biotinylate using cellular biotin levels, which increases labeling background and decreases spatiotemporal control upon biotin supplementation; thus, hit validation becomes more critical. To address this challenge, studies can be completed in biotin-reduced media (dialyzed serum) to reduce off-targets [61]. As an example application of TurboID, the protein was fused to the mitochondrially-targeted chaperone PfHsp60 to identify Plasmodium falciparum mitochondrial proteins. The localization of 5 MS-identified hits to the P. falciparum mitochondria was confirmed using microscopy, hinting at the potential for this method to spatially define the Plasmodium proteome [62].

As a faster alternative that retains greater temporal resolution compared to promiscuous biotin ligases, the engineered ascorbate peroxidases APEX and APEX2 (a variant with improved catalytic efficiency) have been adapted for proximity labeling [63,64]. Like BioID, APEX/APEX2 can be expressed in cells as fusion proteins or with encoded signaling sequences to enable targeting to specific organelles (Figure 3A). Upon supplementation with biotin-phenol and hydrogen peroxide, these enzymes produce highly reactive biotin-phenoxyl radicals that will label proteins within 20-300 nm at electron-rich residues like tyrosine or tryptophan. This rapid reaction (<1 min) must be quenched quickly to avoid damage from reactive oxygen species but enables complete spatiotemporal control with increased sensitivity for transient protein-protein interactions. Thus, APEX/APEX2-labeled proteins reflect the immediate cellular state, which can capture shorter-lived or rapidly changing parasite life-stages. Accordingly, APEX2 was employed to study Plasmodium berghei ookinetes—a short-lived (~21 hours) mosquito stage parasite form—its only implementation in Plasmodium reported to date [65]. APEX2 fused to the ookinete micronemal protein SOAP helped identify 81 proteins that putatively localize to the microneme, an apical organelle required for host invasion. Through validation studies, a previously unannotated protein (termed akratin) was found to have a novel and essential role in parasite transmission, as the protein was required to complete sexual development in mosquito vectors. This discovery highlights the promise of this method to resolve key molecular events in transient and elusive parasite forms.

Proximity platforms enable the selective enrichment of parasite proteins when the fusion enzymes are expressed in the pathogen, a requirement which could limit their use in less genetically tractable life-stages. In an innovative application that circumvents this challenge, APEX2 with either nuclear or cytoplasmic signaling sequences was overexpressed in HeLa cells and infected with T. gondii to identify parasite proteins exported into the host cell (Figure 3B) [66]. This strategy bypasses the need to genetically modify parasites, relying instead on the standard transfection of mammalian cells. Importantly, this approach recovered known T. gondii effectors and was able to discover a new parasite protein with a role in preventing host cell death (which could clear infection). Host proteins are also labeled with this APEX2-overexpression approach, which hinders detection of lower abundance exported parasite proteins. Recent improvements in the sensitivity of mass spectrometry and data-indepdendent acquisition approaches can facilitate the quantification of these low abundance proteins to tackle more challenging pathogen systems in the future [67,68]. Thus, APEX2 provides a much-needed path to interrogate parasite effectors capable of modulating host processes. Overall, biotin ligase- and peroxidase-proximity platforms are useful for mapping intercellular localizations and identifying protein-protein interactions; therefore, they have great promise to uncover elusive parasite biology and host-pathogen interactions.

Conclusions

Continued development of protein labeling technologies is improving their versatility to probe diverse systems, including protozoan parasites. As noted, MetRSNLL limits L-Anl incorporation to the initiator site in these eukaryotes, which hinders recovery of processed exported proteins. This is because MetRSNLL is bacterial-derived and maintains compatibility with the eukaryotic initiator but not elongator methionyl-tRNA [34]. In bacteria, MetRSNLL charges L-Anl to both methionyl-tRNAs types, and thus has been successfully applied to study intracellular bacterial pathogen protein export [69]. Recent efforts have demonstrated that point mutations in MetRS from varied eukaryotic organisms enable L-Anl incorporation into their proteins at both the initiator and internal methionine codons [70,71]. It has yet been determined if an engineered eukaryotic-derived or parasite synthetase would allow ncAA incorporation at internal codons in protozoan pathogens. However, if achieved, incorporation of L-Anl at every methionine site would enable enrichment of all (intracellular and exported) parasite proteins.

BONCAT and proximity-dependent labeling are powerful tools to track protozoan parasite proteins. Currently, there is unrealized potential in adapting these technologies across various parasite life cycles. For example, protein analysis in the Plasmodium liver stage is traditionally challenging due to low in vitro infection rates (about 1%) and the abundance of proteins from translationally active host cells [8,9]. The development of an L-Anl-incorporating Plasmodium line could enable the selective enrichment of scarce parasite proteins at this stage to provide an unprecedented means to temporally monitor the proteome changes that occur as they dedifferentiate and dramatically replicate (~10,000-fold) [3]. Additionally, BioID or APEX2 could be conjugated to specific liver stage parasite proteins to identify proteins in subcellular compartments. Conversely, BioID constructs or APEX2 can be expressed in the host cell to identify effector proteins in a similar manner as discussed above with T. gondii. However, BioID studies for Plasmodium liver infection would be challenging to complete in vivo since the liver is rich in biotin and background biotinylation could complicate results. Emerging proximity-labeling variants such as UltraID may also improve the recovery of low abundance parasite proteins. UltraID requires less biotin supplementation and therefore decreases background labeling and toxicity concerns related to excessive biotin (BioID) or peroxide (APEX) exposure [72]. While generating the requisite transgenic Plasmodium parasite lines to implement some of these methods in liver stage studies is laborious [73], these approaches could enable previously unattainable spatiotemporal resolution of this historically elusive point in parasite development. Additionally, these methods could be applied to short-lived parasite sexual development stages that occur in the mosquito vector as well as other life-stages of apicomplexan parasites. Thus, we are optimistic in the potential of these technologies to enable novel insights into protozoan parasite protein dynamics throughout their life cycles.

Acknowledgements

Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Funding

We would like to thank the Sloan Research Fellowship Program and Duke University for financial support. Additional fellowship support was provided to C.R.M by a NIH Biotechnology Training Grant (T32GM008555) through the Duke University Center for Biomolecular and Tissue Engineering.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interest to declare.

References

- 1.WHO: World malaria report 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibley LD: Invasion and Intracellular Survival by Protozoan Parasites. Immunol Rev 2011, 240:72–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prudêncio M, Rodriguez A, Mota MM: The silent path to thousands of merozoites: the Plasmodium liver stage. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4:849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Koning-Ward TF, Gilson PR, Boddey JA, Rug M, Smith BJ, Papenfuss AT, Sanders PR, Lundie RJ, Maier AG, Cowman AF, et al. : A newly discovered protein export machine in malaria parasites. Nature 2009, 459:945–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg DE, Zimmerberg J: Hardly Vacuous: The Parasitophorous Vacuolar Membrane of Malaria Parasites. Trends in Parasitology 2020, 36:138–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall N, Karras M, Raine JD, Carlton JM, Kooij TWA, Berriman M, Florens L, Janssen CS, Pain A, Christophides GK, et al. : A comprehensive survey of the Plasmodium life cycle by genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses. Science 2005, 307:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parthasarathy A, Kalesh K: Defeating the trypanosomatid trio: proteomics of the protozoan parasites causing neglected tropical diseases. RSC Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 11:625–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raphemot R, Toro-Moreno M, Lu K-Y, Posfai D, Derbyshire ER: Discovery of Druggable Host Factors Critical to Plasmodium Liver-Stage Infection. Cell Chemical Biology 2019, 26:1253–1262.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu K-Y, Mansfield CR, Fitzgerald MC, Derbyshire ER: Chemoproteomics for Plasmodium Parasite Drug Target Discovery. ChemBioChem 2021, 22:2591–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couvillion SP, Zhu Y, Nagy G, Adkins JN, Ansong C, Renslow RS, Piehowski PD, Ibrahim YM, Kelly RT, Metz TO: New mass spectrometry technologies contributing towards comprehensive and high throughput omics analyses of single cells. Analyst 2019, 144:794–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor MJ, Lukowski JK, Anderton CR: Spatially Resolved Mass Spectrometry at the Single Cell: Recent Innovations in Proteomics and Metabolomics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2021, 32:872–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, Chu S, Tan S, Yin X, Jiang Y, Dai X, Gong X, Fang X, Tian D: Towards Higher Sensitivity of Mass Spectrometry: A Perspective From the Mass Analyzers. Front Chem 2021, 9:813359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dieterich DC, Link AJ, Graumann J, Tirrell DA, Schuman EM: Selective identification of newly synthesized proteins in mammalian cells using bioorthogonal noncanonical amino acid tagging (BONCAT). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103:9482–9487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatzenpichler R, Connon SA, Goudeau D, Malmstrom RR, Woyke T, Orphan VJ: Visualizing in situ translational activity for identifying and sorting slow-growing archaeal–bacterial consortia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113:E4069–E4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichart NJ, Jay ZJ, Krukenberg V, Parker AE, Spietz RL, Hatzenpichler R: Activity-based cell sorting reveals responses of uncultured archaea and bacteria to substrate amendment. ISME J 2020, 14:2851–2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best MD: Click Chemistry and Bioorthogonal Reactions: Unprecedented Selectivity in the Labeling of Biological Molecules. Biochemistry 2009, 48:6571–6584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieterich DC, Lee JJ, Link AJ, Graumann J, Tirrell DA, Schuman EM: Labeling, detection and identification of newly synthesized proteomes with bioorthogonal non-canonical amino-acid tagging. Nat Protoc 2007, 2:532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.tom Dieck S, Müller A, Nehring A, Hinz FI, Bartnik I, Schuman EM, Dieterich DC: Metabolic Labeling with Noncanonical Amino Acids and Visualization by Chemoselective Fluorescent Tagging. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2012, 0 7:Unit7.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalesh K, Denny PW: A BONCAT-iTRAQ method enables temporally resolved quantitative profiling of newly synthesised proteins in Leishmania mexicana parasites during starvation. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13:e0007651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig E, Huyghues-Despointes C-E, Yu C, Handy EL, Sello JK, Kima PE: Structurally optimized analogs of the retrograde trafficking inhibitor Retro-2cycl limit Leishmania infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11:e0005556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kalesh K, Sundriyal S, Perera H, Cobb SL, Denny PW: Quantitative Proteomics Reveals that Hsp90 Inhibition Dynamically Regulates Global Protein Synthesis in Leishmania mexicana. mSystems 2021, 6:e00089–21. **Using BONCAT, the authors assessed the effects of Hsp90 inhibitors on the Leishmania mexicana nascent proteome, establishing a decreased production of ribosomal components and increased production of chaperones upon compound administration. The study is one of the most extensive implementations of BONCAT in protozoan parasites to date.

- 22.Zhang J, Wang J, Ng S, Lin Q, Shen H-M: Development of a novel method for quantification of autophagic protein degradation by AHA labeling. Autophagy 2014, 10:901–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morey TM, Esmaeili MA, Duennwald ML, Rylett RJ: SPAAC Pulse-Chase: A Novel Click Chemistry-Based Method to Determine the Half-Life of Cellular Proteins. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9:722560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Pablos LM, Ferreira TR, Dowle AA, Forrester S, Parry E, Newling K, Walrad PB: The mRNA-bound Proteome of Leishmania mexicana: Novel Genetic Insight into an Ancient Parasite. Mol Cell Proteomics 2019, 18:1271–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang M, Joyce BR, Sullivan WJ, Nussenzweig V: Translational Control in Plasmodium and Toxoplasma Parasites. Eukaryotic Cell 2013, 12:161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatzenpichler R, Scheller S, Tavormina PL, Babin BM, Tirrell DA, Orphan VJ: In situ visualization of newly synthesized proteins in environmental microbes using amino acid tagging and click chemistry. Environ Microbiol 2014, 16:2568–2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couradeau E, Sasse J, Goudeau D, Nath N, Hazen TC, Bowen BP, Chakraborty R, Malmstrom RR, Northen TR: Probing the active fraction of soil microbiomes using BONCAT-FACS. Nat Commun 2019, 10:2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moras M, Lefevre SD, Ostuni MA: From Erythroblasts to Mature Red Blood Cells: Organelle Clearance in Mammals. Frontiers in Physiology 2017, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright MH, Clough B, Rackham MD, Rangachari K, Brannigan JA, Grainger M, Moss DK, Bottrill AR, Heal WP, Broncel M, et al. : Validation of N-myristoyltransferase as an antimalarial drug target using an integrated chemical biology approach. Nature Chem 2014, 6:112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngo JT, Champion JA, Mahdavi A, Tanrikulu IC, Beatty KE, Connor RE, Yoo TH, Dieterich DC, Schuman EM, Tirrell DA: Cell-Selective Metabolic Labeling of Proteins. Nat Chem Biol 2009, 5:715–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grammel M, Zhang MM, Hang HC: Orthogonal alkynyl-amino acid reporter for selective labeling of bacterial proteomes during infection. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2010, 49:5970–5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanrikulu IC, Schmitt E, Mechulam Y, Goddard WA, Tirrell DA: Discovery of Escherichia coli methionyl-tRNA synthetase mutants for efficient labeling of proteins with azidonorleucine in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106:15285–15290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngo JT, Schuman EM, Tirrell DA: Mutant methionyl-tRNA synthetase from bacteria enables site-selective N-terminal labeling of proteins expressed in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110:4992–4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wier GM, McGreevy EM, Brown MJ, Boyle JP: New Method for the Orthogonal Labeling and Purification of Toxoplasma gondii Proteins While Inside the Host Cell. mBio 2015, 6:e01628–14. *In this study, L-azidonorleucine was successfully incorporated into Toxoplasma gondii proteins utilizing a bacterial-derived synthetase. The study demonstrated the feasibility of selective labeling and enrichment of parasite proteins inside host cells using BONCAT.

- 35.Chande AG, Siddiqui Z, Midha MK, Sirohi V, Ravichandran S, Rao KVS: Selective enrichment of mycobacterial proteins from infected host macrophages. Sci Rep 2015, 5:13430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babin BM, Atangcho L, van Eldijk MB, Sweredoski MJ, Moradian A, Hess S, Tolker-Nielsen T, Newman DK, Tirrell DA: Selective Proteomic Analysis of Antibiotic-Tolerant Cellular Subpopulations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. mBio 2017, 8:e01593–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franco M, D’haeseleer PM, Branda SS, Liou MJ, Haider Y, Segelke BW, El-Etr SH: Proteomic Profiling of Burkholderia thailandensis During Host Infection Using Bio-Orthogonal Noncanonical Amino Acid Tagging (BONCAT). Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8:370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimmel J, Kehrer J, Frischknecht F, Spielmann T: Proximity-dependent biotinylation approaches to study apicomplexan biology. Molecular Microbiology 2022, 117:553–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi-Rhee E, Schulman H, Cronan JE: Promiscuous protein biotinylation by Escherichia coli biotin protein ligase. Protein Science 2004, 13:3043–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roux KJ, Kim DI, Raida M, Burke B: A promiscuous biotin ligase fusion protein identifies proximal and interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Journal of Cell Biology 2012, 196:801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim DI, Jensen SC, Noble KA, Kc B, Roux KH, Motamedchaboki K, Roux KJ: An improved smaller biotin ligase for BioID proximity labeling. Mol Biol Cell 2016, 27:1188–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen AL, Kim EW, Toh JY, Vashisht AA, Rashoff AQ, Van C, Huang AS, Moon AS, Bell HN, Bentolila LA, et al. : Novel Components of the Toxoplasma Inner Membrane Complex Revealed by BioID. mBio 2015, 6:e02357–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen AL, Moon AS, Bell HN, Huang AS, Vashisht AA, Toh JY, Lin AH, Nadipuram SM, Kim EW, Choi CP, et al. : Novel insights into the composition and function of the Toxoplasma IMC sutures. Cellular Microbiology 2017, 19:e12678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaji RY, Johnson DE, Treeck M, Wang M, Hudmon A, Arrizabalaga G: Phosphorylation of a Myosin Motor by TgCDPK3 Facilitates Rapid Initiation of Motility during Toxoplasma gondii egress. PLOS Pathogens 2015, 11:e1005268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nadipuram SM, Kim EW, Vashisht AA, Lin AH, Bell HN, Coppens I, Wohlschlegel JA, Bradley PJ: In Vivo Biotinylation of the Toxoplasma Parasitophorous Vacuole Reveals Novel Dense Granule Proteins Important for Parasite Growth and Pathogenesis. mBio 2016, 7:e00808–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nessel T, Beck JM, Rayatpisheh S, Jami-Alahmadi Y, Wohlschlegel JA, Goldberg DE, Beck JR: EXP1 is required for organisation of EXP2 in the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite vacuole. Cellular Microbiology 2020, 22:e13168. *Using EXP2-BioID2 and HSP101-BioID2 fusion proteins, the authors identified proteins at the PVM in Plamodium falciparum-infected blood cells and investigated the role of EXP1 during infection. This study was the first to identify a role for EXP1 and its interaction with EXP2 at the PVM.

- 47. Schnider CB, Bausch-Fluck D, Brühlmann F, Heussler VT, Burda P-C: BioID Reveals Novel Proteins of the Plasmodium Parasitophorous Vacuole Membrane. mSphere 2018, 3:e00522–17. *The authors used a fusion protein of EXP1 and BirA* to identify PVM proteins during Plasmodium berghei infection of blood cells and validated the localization of 7 proteins in the blood and liver stages. This study highlights the use of BioID in the liver-infection model P. berghei and begins to characterize the liver stage PVM, which has not been fully characterized.

- 48.Kehrer J, Frischknecht F, Mair GR: Proteomic Analysis of the Plasmodium berghei Gametocyte Egressome and Vesicular bioID of Osmiophilic Body Proteins Identifies Merozoite TRAP-like Protein (MTRAP) as an Essential Factor for Parasite Transmission. Mol Cell Proteomics 2016, 15:2852–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khosh-Naucke M, Becker J, Mesén-Ramírez P, Kiani P, Birnbaum J, Fröhlke U, Jonscher E, Schlüter H, Spielmann T: Identification of novel parasitophorous vacuole proteins in P. falciparum parasites using BioID. Int J Med Microbiol 2018, 308:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wichers JS, Wunderlich J, Heincke D, Pazicky S, Strauss J, Schmitt M, Kimmel J, Wilcke L, Scharf S, von Thien H, et al. : Identification of novel inner membrane complex and apical annuli proteins of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell Microbiol 2021, 23:e13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geiger M, Brown C, Wichers JS, Strauss J, Lill A, Thuenauer R, Liffner B, Wilcke L, Lemcke S, Heincke D, et al. : Structural Insights Into PfARO and Characterization of its Interaction With PfAIP. J Mol Biol 2020, 432:878–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long S, Anthony B, Drewry LL, Sibley LD: A conserved ankyrin repeat-containing protein regulates conoid stability, motility and cell invasion in Toxoplasma gondii. Nat Commun 2017, 8:2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Long S, Brown KM, Drewry LL, Anthony B, Phan IQH, Sibley LD: Calmodulin-like proteins localized to the conoid regulate motility and cell invasion by Toxoplasma gondii. PLOS Pathogens 2017, 13:e1006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seidi A, Muellner-Wong LS, Rajendran E, Tjhin ET, Dagley LF, Aw VY, Faou P, Webb AI, Tonkin CJ, van Dooren GG: Elucidating the mitochondrial proteome of Toxoplasma gondii reveals the presence of a divergent cytochrome c oxidase. eLife 2018, 7:e38131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan M, Li M, Li L, Song Y, Hou L, Zhao J, Shen B: Identification of Novel Dense-Granule Proteins in Toxoplasma gondii by Two Proximity-Based Biotinylation Approaches. J Proteome Res 2019, 18:319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koreny L, Zeeshan M, Barylyuk K, Tromer EC, van Hooff JJE, Brady D, Ke H, Chelaghma S, Ferguson DJP, Eme L, et al. : Molecular characterization of the conoid complex in Toxoplasma reveals its conservation in all apicomplexans, including Plasmodium species. PLOS Biology 2021, 19:e3001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tu V, Tomita T, Sugi T, Mayoral J, Han B, Yakubu RR, Williams T, Horta A, Ma Y, Weiss LM: The Toxoplasma gondii Cyst Wall Interactome. mBio 2020, 11:e02699–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nadipuram SM, Thind AC, Rayatpisheh S, Wohlschlegel JA, Bradley PJ: Proximity biotinylation reveals novel secreted dense granule proteins of Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites. PLOS ONE 2020, 15:e0232552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Birnbaum J, Scharf S, Schmidt S, Jonscher E, Hoeijmakers WAM, Flemming S, Toenhake CG, Schmitt M, Sabitzki R, Bergmann B, et al. : A Kelch13-defined endocytosis pathway mediates artemisinin resistance in malaria parasites. Science 2020, 367:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Branon TC, Bosch JA, Sanchez AD, Udeshi ND, Svinkina T, Carr SA, Feldman JL, Perrimon N, Ting AY: Efficient proximity labeling in living cells and organisms with TurboID. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:880–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.May DG, Scott KL, Campos AR, Roux KJ: Comparative Application of BioID and TurboID for Protein-Proximity Biotinylation. Cells 2020, 9:1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lamb IM, Rios KT, Shukla A, Ahiya AI, Morrisey J, Mell JC, Lindner SE, Mather MW, Vaidya AB: Mitochondrially targeted proximity biotinylation and proteomic analysis in Plasmodium falciparum. PLOS ONE 2022, 17:e0273357. *To uncover mitochondrial Plasmodium falciparum proteins, TurboID was conjugated to the mitochondria-resident chaperone Hsp60. This study identified a list of putative mitochondrial proteins that could serve as new targets for antimalarial interventions.

- 63.Rhee H-W, Zou P, Udeshi ND, Martell JD, Mootha VK, Carr SA, Ting AY: Proteomic Mapping of Mitochondria in Living Cells via Spatially Restricted Enzymatic Tagging. Science 2013, 339:1328–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lam SS, Martell JD, Kamer KJ, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Mootha VK, Ting AY: Directed evolution of APEX2 for electron microscopy and proximity labeling. Nat Methods 2015, 12:51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kehrer J, Ricken D, Strauss L, Pietsch E, Heinze JM, Frischknecht F: APEX-based proximity labeling in Plasmodium identifies a membrane protein with dual functions during mosquito infection. 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.09.29.318857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rosenberg A, Sibley LD: Toxoplasma gondii secreted effectors co-opt host repressor complexes to inhibit necroptosis. Cell Host & Microbe 2021, 29:1186–1198.e8. **Here, standard transfection protocols were employed to ectopically overexpress APEX2 in the nucleus or cytosol of HeLa cells, which were subsequently infected with Toxoplasma gondii. From this study,the parasite protein TgNSM was found to be responsible for altering host signaling pathways during the chronic bradyzoite stage. This documents the first use of APEX2 expressed in the host cell to study parasite infection.

- 67.Gillet LC, Navarro P, Tate S, Röst H, Selevsek N, Reiter L, Bonner R, Aebersold R: Targeted Data Extraction of the MS/MS Spectra Generated by Data-independent Acquisition: A New Concept for Consistent and Accurate Proteome Analysis*. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2012, 11:O111.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Siddiqui G, De Paoli A, MacRaild CA, Sexton AE, Boulet C, Shah AD, Batty MB, Schittenhelm RB, Carvalho TG, Creek DJ: A new mass spectral library for high-coverage and reproducible analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum–infected red blood cell proteome. GigaScience 2022, 11:giac008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mahdavi A, Szychowski J, Ngo JT, Sweredoski MJ, Graham RLJ, Hess S, Schneewind O, Mazmanian SK, Tirrell DA: Identification of secreted bacterial proteins by noncanonical amino acid tagging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Erdmann I, Marter K, Kobler O, Niehues S, Abele J, Müller A, Bussmann J, Storkebaum E, Ziv T, Thomas U, et al. : Cell-selective labelling of proteomes in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Commun 2015, 6:7521. *This is one of the first studies employing an engineered eukaryotic methionyl-tRNA synthetase to incorporate L-azidonorleucine into proteins. This enabled efficient incorporation at internal methionine codons, which previously limited labeling of exported proteins when employing bacterial-derived synthetases in eukaryotic systems.

- 71.Mahdavi A, Hamblin GD, Jindal GA, Bagert JD, Dong C, Sweredoski MJ, Hess S, Schuman EM, Tirrell DA: Engineered Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase for Cell-Selective Analysis of Mammalian Protein Synthesis. J Am Chem Soc 2016, 138:4278–4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kubitz L, Bitsch S, Zhao X, Schmitt K, Deweid L, Roehrig A, Barazzone EC, Valerius O, Kolmar H, Béthune J: Engineering of ultraID, a compact and hyperactive enzyme for proximity-dependent biotinylation in living cells. Commun Biol 2022, 5:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thathy V, Ménard R: Gene targeting in Plasmodium berghei. Methods Mol Med 2002, 72:317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]