Abstract

Background

Diabetes and hypertension are major synergistic risk factors for microvasculopathy, microangiopathy, and neuropathy problems among patients with chronic disorder. Control of hypertension and diabetes have significant value in delaying these complications. The key for delaying complications in diabetes and hypertension is the quality of care.

Objective

This study explored the quality of diabetes-hypertension care in health care facilities with high disease burden in Sidama region.

Methodology

An institution-based cross-sectional study was carried out. Patients with diabetes and hypertension were included in the study. In this study, we included 844 patients were included in the study. For data collection, the application software Kobo Collect was utilized. For data analysis, SPSS version 25 was used. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with quality of care. To measure quality, we employed patient outcome indicators focusing on long-term complications of the eye, heart, fasting blood pressure, and neuropathic complications. Ethical approval clearance was obtained from Hawassa University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences ethical review board.

Results

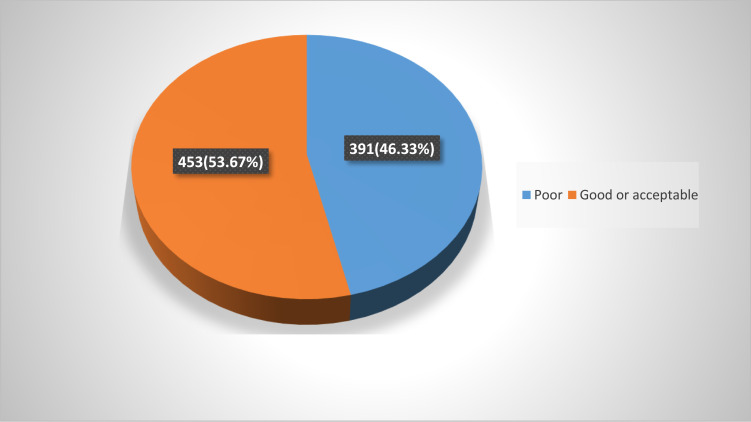

The mean age of patients was 47.99 ± 15.26 years, with a range of 18–90 years, while men make up 62% of the overall number of respondents. In terms of marital status, 700 (82.9%) were married. Concerning place of residence; 433 (51.3%) were from rural area. The primary diagnosis is diabetes for 419 (49.6%) patients, and nearly 23% of patients have both diabetes and hypertension. In terms of blood pressure, the average systolic pressure was 129.6 mmHg and the average diastolic pressure was 82.6 mmHg. Among the study participants, 391 (46.33%) patients received poor quality of chronic disease care. Patients living alone, patients who have professional work, fasting blood glucose in normal range, patients with higher education, and patients with serum creatinine receive relatively good chronic illness care.

Keywords: high blood glucose, high blood pressure, diabetes-hypertension, Sidama, Ethiopia

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) take the lion's share of morbidity, mortality, and disability. Every year, more than 41 million people die from NCDs like heart attacks, stroke, cancer, and diabetes. That is more than 70% of all deaths worldwide. Besides, the burden of NCDS has a catastrophic economic impact.1

Statistical and Physiologic relationship exists between the two common non-communicable disorders: diabetes and hypertension or high blood pressure. Individuals with diabetes are at a much greater risk of developing high blood pressure. Hypertension is twice as common in those with diabetes as in non-diabetic individuals.2

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension coexist more frequently than reported, ranging from up to 60% to 65% of coexistence. It is also known that high blood pressure is two to three times more frequent in diabetic patients. These pathologies are independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease and when they coexist there is an increase of two to eight times in morbidity for cardiovascular disease and the mortality for those diseases is duplicated.3

The magnitude of hypertension was high. However, only 9% of all hypertensives were controlled. Moreover, one-fifth of hypertensives who were diagnosed but untreated end up in hypertensive crisis.4

According to international diabetic’s federation (IDF) in 2019, 463 million peoples were diabetic globally. More than 321,100 deaths in the Africa Region could be attributed to diabetes; 79.0% of those deaths occurred in people under the age of 60, the highest proportion of any region in the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, where resources are often lacking and governments may not prioritize screening for diabetes, the proportion of people with diabetes who are undiagnosed is as high as 90% in some countries.5

Research on the determinants of diabetes and hypertension control is sparse. This is most likely owing to the numerous influencing elements that interact and influence many of the disease’s results in various areas. Data from a few studies that have looked into this topic may not be particularly useful because most of the elements that influence better disease control are reliant on specific variables, such as the country and population analyzed. Furthermore, healthcare delivery systems, co-morbidities, and cultural and socioeconomic factors differ from one country to the next.

Identifying factors particular to the places where patients receive care can have a substantial impact on enhancing care quality and helping to improve and reduce mortality caused by the consequences of these medical conditions. Furthermore, comprehending and applying this information will be critical to the nation’s economic success. As a result, pinpointing particular elements that affect each disease’s quality of care can increase patients’ outcome.

Objectives

The ultimate objective of this study project is to evaluate the quality of diabetes/hypertension care provided by health care facilities in high disease burden communities in the Sidama Region.

Specific objectives

Assess the level of chronic disease (diabetes, hypertension) care provided by medical facilities in the Sidama Region.

To identify the parameters that influence the quality of chronic disease (diabetes-hypertension) in patients with diabetes-hypertension in medical institutions in Sidama Region high disease burden areas.

Methodology

Study Area

Sidama region is one of the ten regions of Ethiopia. Hawassa city is the capital of the newly formed Sidama Region. Bona, Yaye, and Daye hospitals were where we collected the data.

Study Design and Period

The multi-center, institution-based, cross-sectional study was conducted between May to August 2022.

Source Population

For care quality, the source population was all patients diagnosed with diabetes/hypertension and have follow-up in Bona, Daye, and Yaye hospitals.

Study Population

All sampled diabetic/hypertensive patients who have follow-up care visit at selected hospitals of Sidama regional state Bona District health care institutions during the study period.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

All patients registered for follow-up care in Bona, Daye, and Yaya hospitals who have at least more than three months of follow-up.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients below 18 years of age. Patients presented with complications and presented to the hospital for the first time at the time of data collection. Patients come from outside the study district and have visited health institutions outside the study area more than three times.

Study Variables

Dependent Variables

We assessed intermediate outcome indicators. To measure the care quality, we computed the presence of complications in the eye, foot, respiratory, cardiac, measure of blood pressure, level of fasting blood glucose, and measure of serum creatinine.6

Independent Variables

Demographic admission data: age, marital status, educational level, monthly income, smoking status, usual residency, occupation, living status,

Comorbidities: COPD, heart failure, chronic renal, cirrhosis, HIV infection,

Clinical factors: such as FBS/RBS, blood pressure, BMI, glycosylated hemoglobin, pharmacologic drugs,

Metabolic syndrome and lipid profile,

Knowledge.

Sample Size Determination

The proportion of diabetic care quality and hypertensive care quality is unknown in the study area. The proportion for both diabetic and hypertensive care quality was set at 50%. The chosen margin of error was 5%, considering 10% none response rate, and 95% confidence interval.

The required sample size was determined using a single population formula for both diabetic and hypertensive care quality.

|

where n = sample size

Z = reliability coefficient with 95% confidence interval

P = prevalence of the outcome of interest

d = standard error allowed

The maximum possible sample size is 384. Considering a 10% non-response rate, the total is 422. Considering a design effect of 2, we had 844 patients.

Sampling Procedure

Consecutive sampling technique was used for this study. Patients who have at least three-month follow-up in the health institution of the district during the study period.

Data Collection Tool and Procedures

Data was collected using interviewer-administered structured questionnaire, observation checklist, and medical chart review. The questionnaire contains two parts: patient socio-demographic and clinical characteristics.

The questionnaire was translated from English to Afo-Sidama and Amharic languages by native speakers of the languages who are proficient in English and then back translated to English by other translators to check its consistency in translation. Ten nurses collected the data.

Data Quality Management

Three days of intensive training was given for data collectors and supervisors about data collection methods and how to handle ethical issues. Pre-test was conducted on 5% of sample size at Hawassa University's Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and Adare General Hospital among patients with diabetes/hypertension was conducted. This was done to identify impending problems with data collection instruments, check the consistency of the questionnaires, and assess the performance of the data collectors. Regular supervision by the supervisors and the principal investigator was made to ensure that all necessary data are properly collected. Each day during the data collection, filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and consistency by supervisors and principal investigator. Incomplete questionnaires were discarded.

Data Management and Analysis Plan

The data was processed with SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM) for cleaning, coding, and analysis. Data transformation was done via automatic recoding, and certain variables were sorted according to the recorded outcomes. Where required, descriptive statistics such as means, ranges, standard deviations, and p-values were given. To find the determinants influencing quality of care, logistic regression modeling was used because the outcome variable was categorical. In the multivariate model, every independent variable in the bivariate analysis with p-values less than 0.25 was included. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 and the results were presented as regression coefficients (expβ) with 95% confidence intervals.

Operational Definition

Quality diabetic/hypertension care: based on intermediate outcome analysis, patients with less than or equal to two complications were considered to as getting quality care.

Poor quality of care: based on intermediate outcome analysis, patients with more than or equal to three complications were considered as getting poor quality of care.

Result

Sociodemographic Characteristics

We reviewed and interviewed 844 patients diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes. The mean age of the patients was 47.99 ± 15.26 years, with a range of 18–90 years. Of the total number of respondents, 523 (62.0%) of them were men. Regarding marital status, 700(82.9%) were found to be married. Concerning place of residence, 433 (51.3%) of the inhabitants were rural. Moreover, 266 (31.5%) of the participants had no formal education or were unable to read and write. More details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Diabetes/Hypertension Attending Medical Follow-Up Clinics in Sidama Region High Disease Burden Area, Ethiopia, May 1 to August 30/2022 (N = 844)

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | Mean age ± SD | 47.99 ± 15.26 | |

| Sex | Male | 523 | 62.0 |

| Female | 321 | 38.0 | |

| Marital status | Married | 700 | 82.9 |

| Single | 77 | 9.1 | |

| Widowed | 33 | 3.9 | |

| Divorced/separated | 34 | 4.0 | |

| Educational status | Secondary not completed | 332 | 39.3 |

| Unable to write and read | 266 | 31.5 | |

| Secondary completed | 99 | 11.7 | |

| Certificate/diploma | 88 | 10.4 | |

| Tertiary completed | 59 | 7.0 | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 296 | 35.1 |

| Merchant | 194 | 23.0 | |

| Government Employee | 149 | 17.7 | |

| Others specify | 123 | 14.6 | |

| House wife | 83 | 9.8 | |

| Unemployed | 55 | 6.5 | |

| Students | 22 | 2.6 | |

| Retired | 20 | 2.4 | |

| Others | 25 | 2.9 | |

| Residence | Rural | 433 | 51.3 |

| Urban | 411 | 48.7 | |

| Income | Low income | 633 | 75.0 |

| Lower middle income | 201 | 23.8 | |

| Upper middle income | 8 | 0.9 | |

| High income | 2 | 0.2 | |

Clinical and Behavioral Characteristics

Among the 844 participants in the study, 167 (19.8%) had chronic comorbidities excluding hypertension or diabetes. Diabetes was the primary diagnosis for 419 (49.6%) patients, with nearly 23% having both diabetes and hypertension. The average systolic blood pressure was 129.6 mmHg, and the average diastolic blood pressure was 82.6 mmHg. Additionally, the mean fasting blood glucose level was 81.14 mg/dl. Among patients with hypertension as the primary diagnosis, the average systolic blood pressure was 139.86 ± 19.01 mmHg, and the average diastolic blood pressure was 86.11 ± 14.175 mmHg. For further details on other clinical and behavioral factors, refer to Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical and Behavioral Factors of Patients with Diabetes/Hypertension Attending Medical Follow-Up Clinics in Sidama Region High Disease Burden Area, Ethiopia, May 1/2022 to August 30/2022 (N = 844)

| Variables (N=844) | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of disease diagnosis | Both Diabetes and Hypertension | 193 | 22.9 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 419 | 49.6 | |

| Hypertension | 232 | 27.5 | |

| Comorbidity other than hypertension and or diabetes mellitus | No | 677 | 80.2 |

| Yes | 167 | 19.8 | |

| Current alcohol use | No | 729 | 86.4 |

| Yes | 115 | 13.6 | |

| Hx of readmission to hospital | No | 390 | 46.2 |

| Yes | 454 | 53.8 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 73 | 8.6 |

| Health weight | 473 | 56.0 | |

| Over weight | 218 | 25.8 | |

| Obese | 66 | 7.8 | |

| Eye finding | Normal | 620 | 73.5 |

| Complications sees | 224 | 26.5 | |

| Findings on the foot | No foot finding | 700 | 82.9 |

| Oedematous leg | 46 | 5.5 | |

| Weakness of lower extremity | 13 | 1.5 | |

| Foot ulcer | 60 | 7.1 | |

| Pain | 25 | 3.0 | |

| Respiratory findings | No finding | 801 | 94.9 |

| Problem of breathing pattern or SOB | 43 | 5.1 | |

| Cardiovascular findings | No cardiac finding | 695 | 82.3 |

| Murmurs, Arrhythmias or Heart failure or tachycardia | 149 | 17.7 | |

| Neurologic finding | No | 827 | 98.0 |

| Yes | 17 | 2.0 | |

| Serum creatinine | No record | 185 | 21.9 |

| Low | 171 | 20.3 | |

| Normal serum creatinine level | 351 | 41.6 | |

| High serum creatinine | 135 | 16.0 | |

| Outlier | 2 | 0.2 | |

| FBS measure | Normal | 268 | 31.8 |

| High or lower | 511 | 60.5 | |

| Not measures | 65 | 7.7 | |

| Physical need | No unmet need | 271 | 32.1 |

| Physical need unmet | 573 | 67.9 | |

| Health system information need | Met | 456 | 54.0 |

| Unmet | 388 | 46.0 | |

| Rx side effect | No | 643 | 76.2 |

| Yes | 201 | 23.8 | |

| Additional salt use | No | 493 | 58.4 |

| Yes | 351 | 41.6 | |

| Blood pressure | Mean DBP(SD) | 82.6 ±13.39 mmHg | |

| Mean SBP(SD) | 129.5 ±19.56 mmHg | ||

| Triglyceride N 257 | 121.79 ± 20.50 mg/dl | ||

| LDL N = 251 | 98.72 ± 22.57 mg/dl | ||

| Mean Waist circumference (SD) | 79.11 ± 10.26 cm | ||

| Mean Hip circumference (SD) | 87.42 ± 11.54 cm | ||

| Mean FBS(SD) N = 777 | 81.14 ± 9.81mg/dl | ||

Quality of Care

In order to evaluate the quality of care, we looked at eight intermediate outcome indicators: blood pressure readings, serum creatinine levels, and the existence of complications in different body systems after a diagnosis of diabetes or hypertension, such as neurological, cardiovascular, respiratory, eyes, and feet, in addition to fasting blood glucose levels. Based on this assessment method, we found that 391 people (46.33%) did receive poor quality of care. Less than 4% of the patients had no problems at all in terms of complications. For illustration, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Quality of care for patients with diabetes/hypertension attending medical follow-up clinics in Sidama region high disease burden area, Ethiopia, May 1/2022 to August 30/2022.

Factors Affecting Quality of Care of Diabetes/Hypertension

Logistic regression analysis showed that quality of care for patients living alone is 1.5 times more likely to be good as compared to those living with their sexual partner (AOR1.57, CI 1.04–2.43). Univariate logistic regression indicates that higher formal education has a positive association with quality of care. As an illustration, patients with higher education were 1.5 times more likely to get good quality of care as compared to patients who were unable to read and write while keeping all other factors constant (COR 1.512, CI 1.004–2.275). With regard to Occupation, professional work or office work has a positive impact on the quality of care. The odd of getting good quality of care is 1.9 times that of farmers (AOR1.92, CI 1.21, 3.05); for more details, refer Table 3.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Quality of Care Among Patients with Diabetes/Hypertension Attending Medical Follow-Up Clinics in Sidama Region High Disease Burden Area, Ethiopia, May 1 to August 30/2022

| Variables | Quality of care | COR(CI) | AOR(CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | ||||

| Living with | Partner | 362 | 338 | 1 | |

| Alone | 91 | 53 | 1.603 (1.108, 2.32) | 1.57 (1.014, 2.431) | |

| FBG | Normal | 210 | 58 | 1 | |

| High/low | 234 | 278 | 0.233 (0.166, 0.377) | 0.115 (0.074, 0.179) | |

| Not measured | 9 | 58 | 0.044 (0.021, 0.95) | 0.051 (0.02, 0.12) | |

| Educational status | Higher education | 89 | 58 | 1.512 (1.004, 2.275) | |

| 2ry education | 230 | 201 | 1.127 (0.83, 1.531) | ||

| No formal Education | 132 | 134 | 1 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 146 | 150 | 1 | |

| Professional or office | 94 | 62 | 1.558 (1.05, 2.31) | 1.92 (1.21, 3.05) | |

| Merchant | 109 | 85 | 1.317 (0.916, 1.896) | 1.36 (0.891, 2.081) | |

| Unemployed | 41 | 34 | 1.239 (0.745, 2.06) | 1.118 (0.622, 2.009) | |

| Others | 63 | 60 | 1.079 (0.701, 1.643) | 1.08 (0.666, 1.750) | |

| BMI | Normal | 265 | 208 | 1 | |

| Abnormal | 188 | 183 | 0.806 (0.614, 1.059) | ||

| Type of chronic disease | Diabetes | 258 | 161 | 1 | |

| Hypertension | 103 | 129 | 0.498 (0.360, 0.690) | 0.249 (0.152, 0.409) | |

| Both DM & Hypertension | 92 | 101 | 0.568 (0.403, 0.802) | 0.438 (0.296, 0.650) | |

| Creatinine measure | Normal value | 228 | 123 | 1 | |

| Not normal value | 225 | 268 | 0.453 (0.342, 0.600) | 0.319 (0.229, 0.444) | |

| Recurrence fear | Yes | 170 | 124 | 1.293 (0.972, 1.721) | |

| No | 283 | 267 | 1 | ||

| Rx side effect | No | 344 | 299 | 1 | |

| Yes | 109 | 92 | 0.707 (0.488, 1.025) | ||

Discussion

The health care system of Ethiopia has many obstacles to overcome in the quest to improve chronic disease care quality, specifically hypertension and diabetes. These difficulties might include things like equipping the health institutions with adequate and up-to-date equipment, the growing burden of chronic NCDs, and making sure that everyone in society receives health care equally. Measuring the quality of care for chronic illnesses like diabetes and hypertension is a contentious and challenging task. The glycated hemoglobin (HgA1C) test was thought to be a reliable indication of both good glycemic management and healthcare quality;7 however, finding this investigation in our study setup was impossible. In a 1990 report, the Institute of Medicine defined quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”8 Various literature sources employ different metrics to assess the quality of diabetes care. For instance, a study carried out in Kenya utilized indicators such as changes in glycated hemoglobin levels, body mass index, and the occurrence of complication.9

A number of measures were widely recognized as process indicators for quality of care evaluation. These may include the proportion of patients who had at least one yearly HbA1c test, the proportion of patients who had at least one annual LDL cholesterol test, and the proportion of patients who had at least one microalbuminuria test. Furthermore, it is possible to evaluate quality through yearly documentation of smoking status, at least one annual foot exam, and identifying dilated eye exams.6 These process indicators are not available in our study location. From a procedural viewpoint, the absence of diagnostic studies or treatment approaches that provide information on the care process prevents us from making any judgments regarding the quality of care in terms of care delivery. Because there were not enough resources in the medical facilities, we were unable to take advantage of quality from the standpoint of the care delivery process. Most hospitals in our study setting do not have the infrastructure, diagnostic machines, and supplies needed to perform the tests indicated above.

To assess the quality of care for chronic diseases, we used a variety of criteria, such as the detection of complications or abnormalities during eye exams, neurological evaluations, respiratory or cardiovascular problems, foot complications, serum creatinine levels, and blood pressure readings. Three or more problems were considered signs of poor care. Because there were no measures available for glycated hemoglobin, it was disregarded as a measure of the quality of care.

The quality of care differs from one institution to the next. According to the findings of the current study, the quality of diabetes care in Jimma was much beyond the suggested threshold.10 As of our study, nearly half of patients were not receiving the acceptable quality of care. The possible reason behind this may be the absence of recommended diagnostic investigations in the settings where we conducted the study. As an illustration, no patient has A1C measure as an indicator of glycemic control. On top of this, nearly one-fourth of patients have investigation related to lipid profile.

Regarding quality indicators through HgA1c, none of the patients underwent this test, indicating that fasting blood glucose was the sole parameter utilized for glycemic control in our study area. A Tunisian study revealed that less than 5% of diabetic patients had an HbA1c measurement documented in their medical records.11 Though this is not as of the standard for diabetes care, it is better than our study area. This indicates that the care delivery for patients with diabetes is below the recommended approach in our study setting. Furthermore, annual lipid profiles and microalbuminuria tests were not frequently carried out. This may have to do with the fact that the majority of those tests are available at the tertiary and comprehensive specialty hospital level.

For hypertensive patients, we computed the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Those above the mean were leveled as poorly controlled cases. The mean systolic blood pressure in our study area was 140 mmHg, which is the cut of point for diagnosis of this case. In high-income nations, 20–30% of hypertensive patients do not have controlled blood pressure, and this percentage is much higher in low-income countries, 70–90% of hypertensive patients in the general population are not optimally controlled.12 Despite the availability of numerous effective antihypertensive medicines, hypertension control remains inadequate. In both high- and low-income countries, 27% and 10% of hypertension patients have reached their goal blood pressure levels, respectively.13

Education has a substantial effect on human life. With regard to this study, we found that patients with higher educational level have better odds of getting acceptable quality of care as compared to those with no formal education. However, this study does not demonstrate association between quality of care and sociodemographic factors like age and place of residence. In addition, the usual classification of marital status has no association with quality of care. The finding for the current study is also supported by a study conducted in twelve health centers in Tunisia.11

We have used data recording on patient medical record and analyzed that as our indicator of quality, as there is evidence that the quality of record keeping is positively correlated with increased quality of care.14 Although there has been recent concern about the validity and reliability of using medical records to assess quality of care,15 studies in countries such as ours are not at present able to use measures such as complication rates or HbA1c results.

Conclusion and Recommendation

The overall quality of diabetes-hypertension care in Sidama region high disease burden areas is below the standard and the recommended practice. Only a handful of patients were free of complications. Patient medical record documentation was poor. Patients living alone, patients who have professional work, fasting blood glucose in normal range, patients with higher education, and patients with serum creatinine receive relatively good chronic illness care. We recommend all health care settings request laboratory investigation and record diabetes care outcome indicators. Additionally, we urge health offices, particularly stakeholders, especially regional health office and MOH, to give special attention in equipping health care settings to deliver all essential services for chronic illness. No health setting in the study areas has HA1C test. This makes glycemic control unrealistic. For health care providers: to document all investigations and findings on a patient’s medical record. For patients: to have at least annual HA1C and lipid profile tests.

Acknowledgments

Above all, we would like to thank Hawassa University College for funding this research. We would also like to thank the data collectors for their endeavor and interest in taking part in data collection. Our heartfelt gratitude extends to health institutions and patients who willingly gave us all the information we needed without any reservation.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Hawassa University. However, there is no funding for publication charge.

Data Sharing Statement

By implementing the recommended strategies, we can foster a more open and transparent research environment, thereby enhancing the reproducibility, reliability, and impact of scientific findings. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, subject to certain conditions such as the signing of data use agreements or additional permissions from the institutions involved in the research.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted as of the declaration of Helsinki and obtained received ethical approval from Hawassa University’s College of Medicine and Health Sciences’ health ethical review board. Besides, the university wrote the same permission letter to the Hawassa city authority. The goal of the study was communicated to the respondents, and all study participants provided informed consent. For illiterate and unconscious participants, informed consent was obtained from their legal guardians after reading and addressing the concerns and the requirements of participants. Furthermore, all participants were informed of the possibility of publishing the findings. The right to leave the study at any time was guaranteed. To preserve participant confidentiality, coding was utilized to remove names and other personal identifiers of respondents throughout the study procedure. Throughout this investigation, we followed and adhered to all research rules and regulations concerning human subjects.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the drafting, revising, and critical review of the article; they gave final approval on the manuscript to be published. They also agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted, and they all made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that be in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

References

- 1.Chigom E. Non-Communicable Diseases. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P. The treatment of hypertension in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):134–147. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contreras F, Rivera M, Vasquez J, De PMA, Velasco M. Diabetes and hypertension physiopathology and therapeutics. J Human Hypertens. 2000;14:S26–S31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tapela NM, Clifton L, Tshisimogo G, et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in Botswana: a nationally representative population-based survey. Int J Hypertens. 2020;2020:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2020/8082341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IDF. IDF diabetes atlas IDF diabetes atlas online atlas diabetes IDF; 2021. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/. Accessed February 19, 2024.

- 6.Rothe U, Kugler J, Schulze J, Schulze J. Quality criteria / key components for high quality of diabetes management to avoid diabetes-related complications. J Public Health. 2021;29:1235–1241. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01227-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joynt JKE. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1175–1177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1300122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohr KNE. A strategy for quality assurance; 1990.

- 9.Pastakia SD, Nuche-Berenguer B, Pekny CR, et al. Retrospective assessment of the quality of diabetes care in a rural diabetes clinic in Western Kenya. BMC Endocr Disord. 2018;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12902-018-0324-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gudina EK, Amade ST, Tesfamichael FA, Ram R. Assessment of quality of care given to diabetic patients at Jimma University Specialized Hospital diabetes follow-up clinic, Jimma, Ethiopia. BMC Endocr Disord. 2011;11:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-11-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberti H, Boudriga N, Nabli M. Factors affecting the quality of diabetes care in primary health care centres in Tunis. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2005;68(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertens Dallas Tex. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Hypertension; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/hypertension/#tab=tab_1. Accessed February 19, 2024.

- 14.Kahn KL, Rogers WH, Rubenstein LV, et al. Measuring quality of care with explicit process criteria before and after implementation of a DRG-based prospective payment system. JAMA. 1990;264:1969–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03450150069033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goudswaard AN, Lam K, Stolk RP, Rutten GE. Quality of recording of data from patients with type 2 diabetes is not a valid indicator of quality of care: a cross-sectional study. Fam Pr. 2003;20(2):173–177. doi: 10.1093/fampra/20.2.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

By implementing the recommended strategies, we can foster a more open and transparent research environment, thereby enhancing the reproducibility, reliability, and impact of scientific findings. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, subject to certain conditions such as the signing of data use agreements or additional permissions from the institutions involved in the research.