Abstract

Protein O-glycosylation is a nutrient signaling mechanism that plays an essential role in maintaining cellular homeostasis across different species. In plants, SPINDLY (SPY) and SECRET AGENT (SEC) posttranslationally modify hundreds of intracellular proteins with O-fucose and O-linked N-acetylglucosamine, respectively. SPY and SEC play overlapping roles in cellular regulation, and loss of both SPY and SEC causes embryo lethality in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Using structure-based virtual screening of chemical libraries followed by in vitro and in planta assays, we identified a SPY O-fucosyltransferase inhibitor (SOFTI). Computational analyses predicted that SOFTI binds to the GDP-fucose–binding pocket of SPY and competitively inhibits GDP-fucose binding. In vitro assays confirmed that SOFTI interacts with SPY and inhibits its O-fucosyltransferase activity. Docking analysis identified additional SOFTI analogs that showed stronger inhibitory activities. SOFTI treatment of Arabidopsis seedlings decreased protein O-fucosylation and elicited phenotypes similar to the spy mutants, including early seed germination, increased root hair density, and defective sugar-dependent growth. In contrast, SOFTI did not visibly affect the spy mutant. Similarly, SOFTI inhibited the sugar-dependent growth of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings. These results demonstrate that SOFTI is a specific SPY O-fucosyltransferase inhibitor that can be used as a chemical tool for functional studies of O-fucosylation and potentially for agricultural management.

Structure-based virtual screening and experimental validation identify chemical inhibitors of the plant O-fucosyltransferase SPINDLY.

IN A NUTSHELL.

Background: Like phosphorylation, O-glycosylation is a form of protein posttranslational modification that mediates intracellular signal transduction and regulation. SPINDLY (SPY) and its homolog SECRET AGENT (SEC) mediate O-fucosylation and O-GlcNAcylation, respectively, of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins in Arabidopsis. Loss-of-function mutation of both SPY and SEC causes embryonic lethality, showing their importance and the need for tools that conditionally and reversibly inactivate SPY and SEC. Alphafold has recently generated protein structures and made it possible to identify small molecule inhibitors of proteins using structure-based virtual screening (computation-based molecular docking).

Question: Can we identify chemical inhibitors using the Alphafold-predicted structure of SPINDLY? If so, can SPY inhibitors reveal phenotypes of conditional SPY inactivation in the wild-type and sec backgrounds?

Findings: We identified a small molecule compound as SPY O-fucosyltransferase inhibitor (SOFTI), using structure-based virtual screening followed by experimental tests. We further identified 2 derivatives of SOFTI, SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20, to be more potent inhibitors of SPY. The SOFTs inhibit SPY activity in vitro and in vivo, causing spy-like phenotypes in Arabidopsis and tomato. Our work identifies chemical tools for conditional inhibition of SPY, which enables functional and mechanistic studies of O-glycosylation in broad systems, overcoming the limitations of genetic approaches.

Next steps: Using SOFTIs, one can study the dynamic responses to a temporal reduction of O-fucosylation, the postembryonic phenotypes of loss of both SPY and SEC (SOFTI treatment of sec mutant), and the function of O-fucosylation in crops that lack a spy mutant. Identification of a SEC inhibitor will enable conditional manipulation of both SPY and SEC activities and analysis of the overlapping functions of SPY/O-fucosylation and SEC/O-GlcNAcylation in diverse plant organisms. It is possible to identify inhibitors for SPY and SEC with better specificity and potency by screening larger chemical spaces.

Introduction

Like phosphorylation, O-glycosylation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins plays a crucial role in cellular signaling and regulation. O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification catalyzed by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) is known to mediate nutrient sensing and regulate a variety of biological processes in animals (Hart et al. 2007). While there is only one OGT in mammals, the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome encodes 2 OGT homologs, SPINDLY (SPY) and SECRET AGENT (SEC). Genetic studies indicated overlapping functions of SPY and SEC in a wide range of developmental processes including shared functions essential for viability. SPY and SEC catalyze protein O-fucosylation and O-GlcNAcylation, respectively, utilizing GDP-fucose and UDP-GlcNAc as their respective donor substrates (Zentella et al. 2016; Zentella et al. 2017; Sun 2021). Hundreds of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins with regulatory roles are modified by O-fucose and O-GlcNAc; how the modifications regulate their functions remains largely unknown (Xu et al. 2017; Bi et al. 2023; Zentella et al. 2023).

The loss of SPY or SEC affects many phytohormone and growth responses. The Arabidopsis spindly (spy) mutant was identified for its gibberellic acid (GA) hypermorphic phenotypes, including slender shoot organs, GA-independent seed germination, and early flowering. Subsequent studies uncovered spy's GA-independent phenotypes including cytokinin hyporesponse, aberrant trichome branching and root hair patterning, altered inflorescence phyllotaxis, reduced fertility (Silverstone et al. 2007), and sugar-promoted seedling growth (Bi et al. 2023). In contrast, loss of SEC results in rather mild phenotypes, showing decreased sensitivity to plant hormone GA and early flowering under short-day conditions (Zentella et al. 2016; Xing et al. 2018). The spy sec double mutant is embryonic lethal, which indicates their importance in an essential process and makes it difficult to dissect their shared functions (Hartweck et al. 2002).

SPY/O-fucosylation and SEC/O-GlcNAcylation regulate the functions of several key proteins. One of the most thoroughly studied examples is DELLA, a growth repressor protein that negatively regulates GA signaling. DELLA is antagonistically regulated by O-fucose and O-GlcNAc modifications, which, respectively, enhance and inhibit its interaction with downstream transcription factors, including BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) and PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORs (PIF3 and PIF4) (Zentella et al. 2016; Zentella et al. 2017). SPY facilitates cytokinin signaling by stabilizing the TEOSINTE BRANCHED, CYCLOIDEA AND PCF (TCP) transcription factors TCP14 and TCP15 (Steiner et al. 2012; Steiner et al. 2016). SPY also plays a role in the regulation of alternative RNA splicing events by O-fucosylation of ACINUS, a component of the splicing complex that is involved in the regulation of seed germination, flowering, and ABA signal transduction (Bi et al. 2021). Furthermore, SPY O-fucosylates PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR5 (PRR5) to regulate circadian rhythms (Wang et al. 2020).

Consistent with the redundant functions of SPY and SEC for viability, proteomic studies revealed significant overlaps between proteins modified by O-GlcNAc or O-fucose (Bi et al. 2023; Zentella et al. 2023). For example, about 49% (128/262) of the O-GlcNAcylated proteins are modified by O-fucose (Bi et al. 2023). Many O-GlcNAcylated proteins are also substrates of the BIN2 (BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2) kinase, a key component of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway, whereas the O-fucosylated proteins tend to be targets of the Target of Rapamycin kinase, which mediates nutrient signaling (Bi et al. 2023; Kim et al. 2023). Thus, the proteomic data indicate that the nutrient-signaling and phytohormone-signaling pathways crosstalk through O-glycosylation and phosphorylation of common target proteins. Considering the lethality of the spy sec double mutant, elucidating the independent and shared functions of SPY or SEC requires conditional inactivation of each protein.

In animals, small molecule inhibitors of OGT have been instrumental in the functional study of O-GlcNAc modification (Alteen et al. 2021). Small molecules have also advanced many aspects of plant biology (Lepri et al. 2023). However, chemical inhibitors are yet to be identified for the functional study of O-glycosylation in plants. Traditionally, the identification of small molecule inhibitors involves phenotype-based or assay-based screening of large chemical libraries (Lepri et al. 2023). Structure-based virtual screening has been widely used in human drug discovery research but requires 3D structure of the target protein and has not been widely used in plant research. Recently, a breakthrough in computational structure prediction has generated structures of all proteins of Arabidopsis and major crops (Varadi et al. 2022). Whether the predicted structures are reliable for virtual screening for chemical binders remains arguable (Wong et al. 2022; Scardino et al. 2023).

Here, we identify small molecule inhibitors of SPY through structure-based virtual screening based on the SPY structure predicted by AlphaFold (Jumper et al. 2021). Following computational docking of over 13,890 compounds, we tested the top candidates by in vitro binding and enzyme inhibition assays as well as by in vivo treatment of plants. We identified small molecule compounds as SPY O-fucosyltransferase inhibitors (SOFTIs). We show that SOFTI treatment reduces protein O-fucosylation in Arabidopsis seedlings and causes phenotypes that resemble the spy mutants. Our study demonstrates the promise of AlphaFold-enabled virtual screening and identifies powerful tools for the investigation of protein O-fucosylation.

Results

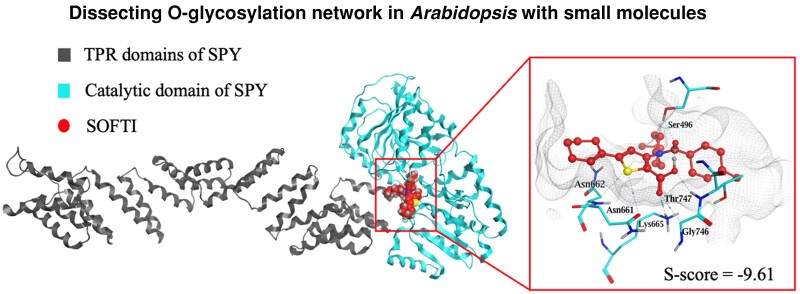

Structure-based virtual screening and in vitro binding assays identify 6 SPY-binding compounds

To find small molecule inhibitors of SPY, we performed structure-based virtual screening for compounds that fit the ligand binding pocket of the O-fucose transferase (OFT) domain of SPY using the AlphaFold-predicted structure of SPY (uniport ID: A0A654F7U9). A library containing 13,890 compounds with broad diversity in chemical scaffolds or bioactivities was screened using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), a commercial molecular docking software. MOE calculates the affinity of a protein–ligand interaction into a numerical value called S-score. The compounds were further selected according to the following criteria: 1) an S-score lower than −6; 2) predicted to form more than 3 polar interactions with the amino acid residues within the SPY ligand-binding pocket; and 3) adopt a relatively simple structure for better cell permeability and convenience for future structural optimization. The virtual screening identified 130 compounds that meet the criteria and thus were considered candidates for inhibitors that compete with the donor substrate GDP-fucose (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Virtual and experimental screening for SPY O-fucosyltransferase interactors. A) A schematic illustration of primary screening using virtual docking. The tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) and catalytic (OFT) domains of the AlphaFold-predicted structure (Jumper et al. 2021) of SPY are shown. B) Summary of the top 6 compounds among 130 candidates that passed the 3 rounds of experimental screening (N.D., not tested). C) The chemical structure of SOFTI. D) Protein thermal shift assay of SPY in response to varying concentrations of SOFTI. E) Quantification of the changes in melting temperature (Tm) of SPY in response to varying concentrations of SOFTI. Error bars indicate ± Sd. F) Bio-layer interferometry assay of the interaction kinetics of SOFTI with SPY.

To narrow down these candidate compounds, we tested the binding of 130 compounds to the full-length recombinant SPY protein purified from Escherichia coli (Supplemental Fig. S1) using the protein thermal shift assay (TSA). Six of these compounds (SPI-1 to SPI-6) affected the thermal stability of SPY by more than 3° at 50 μM concentration (Fig. 1B), indicating their direct binding to SPY. We further tested their binding to SPY using biolayer interferometry (BLI; Abdiche et al. 2008), which measures the binding kinetics between SPY and each compound. One of these compounds showed a concentration-dependent effect on the melting temperature (Tm) of SPY (Fig. 1, C to E) and a dissociation constant (Kd) value of 37 μM in BLI assay (Fig. 1F). We named this compound SPINDLY O-fucosyltransferase inhibitor (SOFTI).

SOFTI inhibits the O-fucosyltransferase activity of SPY in vitro and in vivo

We tested the effects of SOFTI on SPY activity in vitro. SPY O-fucosylates 462 proteins including itself and the Arabidopsis putative ortholog of mammalian NEURAL PRECURSOR CELL EXPRESSED, DEVELOPMENTALLY DOWNREGULATED GENE 1 (NEDD1), which is O-fucosylated on multiple sites (Bi et al. 2023). Therefore, we selected 3TPR-SPY (N-terminal truncated SPY with 3 tetratricopeptide repeats) and NEDD1 as representative substrates to study SOFTI inhibition of SPY activity.

SOFTI displayed concentration-dependent inhibition of the self-fucosylation of recombinant 3TPR-SPY proteins, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 13.32 μM (Fig. 2, A and B). Similarly, SOFTI also blocked the in vitro O-fucosylation of immuno-purified NEDD1-myc proteins (Fig. 2C). To test whether SOFTI is a competitive inhibitor of GDP-fucose binding to SPY, we included 100 μM SOFTI and various concentrations (10, 50, 100, and 200 μM) of GDP-fucose in the enzymatic reaction. In the absence of SOFTI, the effect of increasing GDP-fucose concentration on SPY O-fucosylation saturated at 100 μM, with no further increase at 200 μM of GDP-fucose (Fig. 2, D and E). However, in the presence of SOFTI, which reduced the overall O-fucosylation level, 200 μM GDP-fucose further increased the O-fucosylation level compared with 100 μM GDP-fucose (Fig. 2, D and E), consistent with SOFTI competing with GDP-fucose for the substrate-binding pocket of SPY.

Figure 2.

SOFTI inhibits the enzymatic activity of SPY in vivo and in vitro. A) Immunoblots showing the effects of various concentrations (3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) of SOFTI on the self-fucosylation of recombinant 3TPR-SPY proteins in the presence of 50 μM GDP-fucose. The numbers below the image show the relative band intensity of the AAL-biotin blot normalized to mock-treated control (DMSO). B) Determination of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of SOFTI via nonlinear regression fitting; the 3 points shown in the plot were from 3 biological replicates. C) Immunoblots showing the effects of SOFTI on the in vitro O-fucosylation of NEDD1-myc proteins. The NEDD1-myc proteins were immunoprecipitated from 12-d-old NEDD1-myc/nedd1 spy-23 seedlings and then incubated in vitro with purified 3TPR-SPY proteins, 50 μM GDP-fucose, and increasing concentrations (3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) of SOFTI for 90 min. D) Immunoblots show the competitive effect of SOFTI on the self-fucosylation. 3TPR-SPY proteins were incubated with increasing concentrations of GDP-fucose and 0 (DMSO) or 100 μM of SOFTI. E) Quantification of data shown in D), n = 3 biological replicates. Error bar indicates ± Sd. F and G) Immunoblots show the effects of SOFTI on the O-fucosylation levels of SPY-GFP or NEDD1-myc proteins immunoprecipitated (IP) from 12-d-old seedlings of SPY-GFP/spy-23F) or NEDD1-myc/nedd1G) transgenic lines grown on ½ MS medium and treated with liquid ½ MS medium containing 10 μM (+) or 30 μM (++) of SOFTI for another 2 d. The spy-23 and NEDD1-myc/nedd1 spy-23 were used as negative controls.

We tested the in vivo inhibitory effect of SOFTI. We treated SPY-GFP/spy-23 and NEDD1-myc/nedd1 transgenic seedlings with 10 or 30 μM of SOFTI. We immunoprecipitated the SPY-GFP and NEDD1-myc proteins and analyzed their O-fucosylation by immunoblotting. SOFTI treatment of seedlings reduced the O-fucosylation of both SPY and NEDD1 in vivo, indicating that SOFTI is a cell-permeable inhibitor of SPY (Fig. 2, F and G). We further performed AAL gel blot analysis of the nuclear and cytosolic proteins of wild-type plants treated with SOFTI or mock solution. The results showed that SOFTI treatment reduced the intensity of bands that were also decreased or absent in the spy mutant but had no obvious effects on the SPY-independent bands of the nuclear fraction (Supplemental Fig. S2A). None of the bands detected by AAL in the cytosolic fraction were substantially affected by either spy mutation or SOFTI treatment (Supplemental Fig. S2B). These results are consistent with SPY O-fucosylating mostly nuclear proteins and demonstrate that SOFTI inhibits SPY but has little effect on the O-fucosyltransferases in the endoplasmic reticulum.

SOFTI treatment partially mimics spy mutant phenotypes

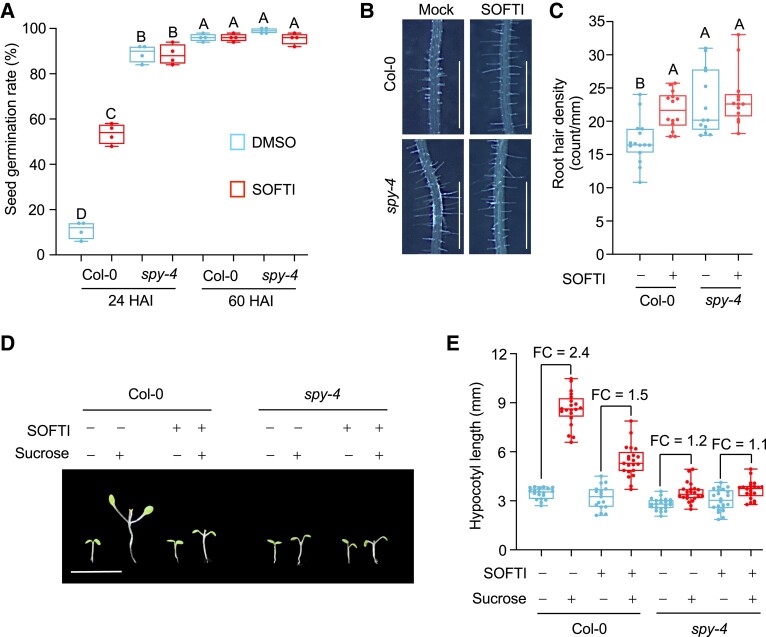

To evaluate the bioactivity and specificity of SOFTI as a SPY inhibitor, we analyzed whether SOFTI treatment causes phenotypes similar to the spy mutant. First, the O-fucosylation of DELLA proteins are known to inhibit GA signaling (Zentella et al. 2017), and spy mutants have been reported to display early-germination phenotypes (Silverstone et al. 2007). At 24 HAI, nearly all the spy-4 seeds germinated, whereas only about 10% of the wild-type (Col-0) seeds germinated. Adding SOFTI to the medium increased the germination rate of wild type to about 50% but had no obvious effect on spy-4. Sixty hours after imbibition, all the seeds germinated (Fig. 3A). Another phenotype of spy is the increased root hair density. Wild-type seedlings treated with SOFTI exhibited higher root hair density than untreated seedlings, and this response to SOFTI was not displayed by the spy-4 mutant (Fig. 3, B and C).

Figure 3.

SOFTI treatment causes spy-like phenotypes. A) Seed germination rates of Col-0 and spy-4 mutant at 24 HAI and 60 HAI in the presence or absence of 30 μM SOFTI. Boxes with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.01, n = 4 for 4 biological replicates each containing 100 seeds. B and C) Root hair phenotype of 8-d-old Col-0 or spy-4 seedlings grown on ½ MS (1% mannitol) medium containing 0 or 10 μM of SOFTI. Bar = 1 mm. C) Statistical analysis of root hair density (number of root hair per millimeter root length) of seedlings shown in B); boxes with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.01. D and E) The Col-0 and spy-4 seedlings were grown under long-day conditions for 4 d on 1/2 MS plates containing 1% sucrose and then transferred into liquid ½ MS medium supplemented with 1% sucrose (+) or mannitol (−) and 0 μM (−) or 30 μM (+) of SOFTI in darkness for 5 d. Bar = 1 cm. E) Statistical analysis of the phenotype shown in D). FC, fold change. n ≥ 15. For A), C), and E), significance levels were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA (Tukey's multiple comparison test). The center line refers to the median, box limits refer to the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers mark the maximum and minimum.

We recently reported that the spy mutant is defective in sugar-promoted seedling growth in the dark (Bi et al. 2023). Sugar (1% w/v sucrose) increased the growth of wild-type seedlings after transferring from light into darkness. The spy mutant seedlings showed an impaired growth response to sugar. The wild-type seedlings treated with SOFTI showed impaired growth response to sugar similar to spy. SOFTI treatment had no obvious effect on the growth of spy on the sugar-containing media (Fig. 3, D and E). These results show that the treatment of wild-type Arabidopsis with SOFTI causes spy-like phenotypes, whereas the spy-4 mutant is insensitive to SOFTI treatment, indicating that SOFTI inhibits SPY specifically in vivo and has no obvious SPY-independent, off-target effect on plant growth.

SOFTI interacts with conserved residues of the SPY substrate-binding pocket

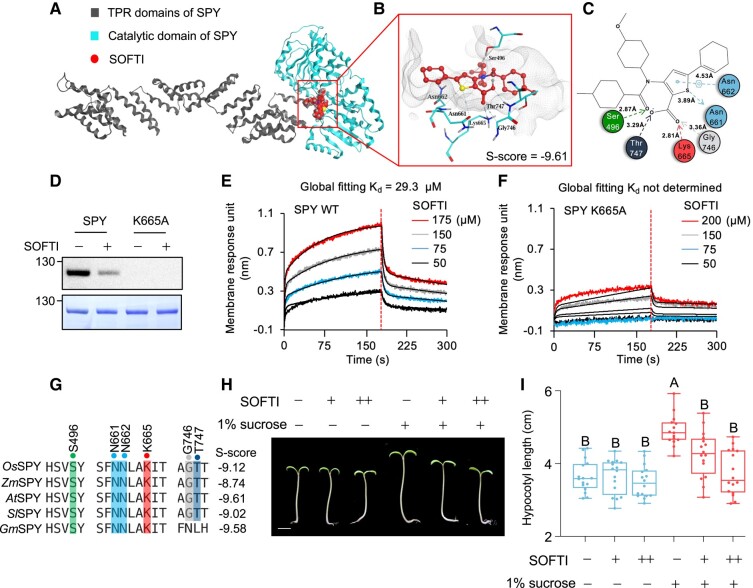

We analyzed how SOFTI interacts with specific residues within the solved structure of the substrate-binding pocket of SPY. For our screen, we used a structure predicted by AlphaFold; however, the structure of SPY has recently been determined by crystallography and cryo-EM (Zhu et al. 2022; Kumar et al. 2023). We performed molecular docking between SOFTI and the crystal structure of SPY. SOFTI was docked to the substrate-binding pocket of SPY within the C-terminal catalytic domain (Fig. 4A). The docking analysis showed that the electronegative atoms of SOFTI form several hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues in the substrate-binding pocket. Specifically, the annular sulfate atom acts as a hydrogen bond donor to form a hydrogen bond with N661 at 3.89 Å. The carbonyl oxygen and the 2 carbonyl oxygen atoms act as hydrogen bond acceptors to form hydrogen bonds with S496, T747, K665, and G746 at 2.87, 3.29, 2.81, and 3.36 Å, respectively. The sulfate-containing, 5-membered ring forms aromatic π-hydrogen interactions with N662 at 4.53 Å (Fig. 4, B and C).

Figure 4.

SOFTI interacts with conserved residues of the active site of SPY. A to C) Simulation of SOFTI docked in the active site of SPY. A) Structure of full-length SPY with SOFTI in the active site. B) Structure of SOFTI (red) docked in the substrate-binding pocket of SPY (gray lines). Key residues interacting with SOFTI are shown in cyan. C) A 2D illustration of the interactions between SOFTI and the amino acid residues in the SPY ligand-binding pocket in B). D) Immunoblot shows the auto-O-fucosylation of the wild-type and K665A mutant SPY proteins in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 300 μM SOFTI. E–F)BLI assay of the kinetics of interaction between SOFTI and the wild-type (WT) SPY (E) or mutant SPY-K665A (F) proteins. The vertical dashed line indicates the boundary between binding and dissociation processes. G) Multiple sequence alignment displaying conserved amino acid residues within the ligand binding pocket of SPY in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, Zea mays, Solanum lycopersicum, and Glycine max. The numbers on the right panel indicate the predicted S-score between SPY orthologs and SOFTI, the lower the score, the higher the predicted binding affinity. H) SOFTI inhibits the sugar-dependent growth response of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Seedlings were grown on 1/2MS medium containing 1% sucrose (+) or mannitol (−) and 10 (+) or 30 (++) μM of SOFTI under light for 3 d followed by 2 d in the dark. Bar = 1 cm. I) Statistical analysis of the hypocotyl lengths showed in H). n = 16 seedlings. Data marked with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.01. Significance levels were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA (Tukey's multiple comparison test), n ≥ 15. The center line refers to the median, box limits refer to the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers mark the maximum and minimum.

Superposition of SOFTI and GDP-fucose showed that they partially overlapped within the pocket (Supplemental Fig. S3A). SOFTI, a structurally simpler molecule, overlapped with the phosphate-phosphate-fucose moiety of the donor substrate GDP-fucose, but not the guanosine part. The 3 amino acid residues N662, K665, and T747 involved in SOFTI–SPY interaction also form hydrogen bonds with the pyrophosphate group of GDP-fucose according to the cryo-EM structure of SPY–GDP–fucose complex (Kumar et al. 2023). In the spy-19 allele, K665 is mutated (Zentella et al. 2017). We expressed SPY-K665A mutant protein in E. coli and used it in vitro. SPY-K665A showed no detectable O-fucosyltransferase activity (Fig. 4D) and barely detectable binding to SOFTI (Kd not determined, compared with 29.3 μM for wild-type SPY; Fig. 4, E and F). The results indicate that SOFTI mimics GDP-fucose and competes for the substrate-binding pocket of SPY, as suggested by the results of our competition assays (Fig. 2D).

SPY belongs to a highly conserved GT41 family of glycosyltransferases (Olszewski et al. 2010). Multiple sequence alignment of SPY in several crop species, including rice (Oryza sativa), maize (Zea mays), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and soybean (Glycine max), showed that the key amino acid residues involved in SPY–SOFTI interaction are highly conserved across different species (Fig. 4G). Docking simulation between SOFTI and the AlphaFold-predicted structures of SPY orthologs from crops showed comparable binding affinity with AtSPY (Fig. 4G). Consistent with the structural prediction, SOFTI inhibited the sugar-dependent growth of tomato seedlings in darkness but had no significant effects on seedlings grown on media without sugar (Fig. 4, H and I), similar to the observation in Arabidopsis (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the catalytic pocket of SPY is highly conserved and that SOFTI can inhibit SPY in different plant species.

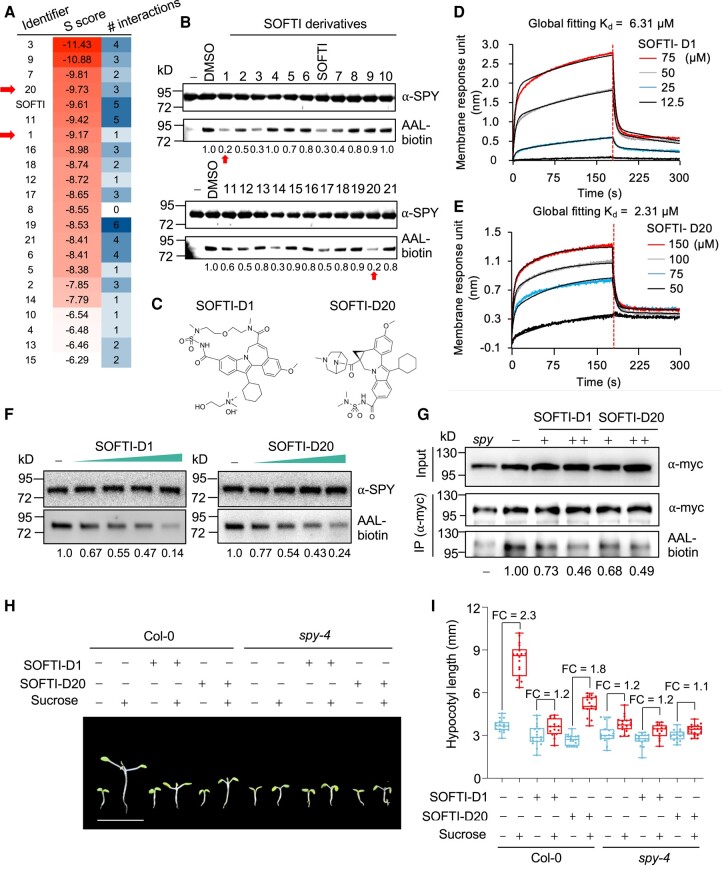

The SOFTI derivatives screen identifies SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20 as alternative SPY inhibitors

Docking simulation showed that SOFTI occupies the part in the SPY substrate-binding pocket that originally binds to the phosphate-phosphate-fucose moiety of GDP-fucose, but not the spaces occupied by the guanosine (Fig. 4D). Therefore, we searched for commercially available compounds that possess the structures of SOFTI that interact with SPY and additional bulkier structures that better occupy the substrate-binding pocket of SPY. We found 21 derivatives of SOFTI and named them SOFTI-D1 to SOFTI-D21 (Supplemental Fig. S4). The derivatives were docked into SPY's substrate-binding pocket and sorted based on their affinity score (the lower the score, the stronger the predicted interaction). Four of these derivatives were predicted to have higher SPY-binding affinity than SOFTI (Fig. 5A). We also tested the effects of all 21 derivatives on the self-fucosylation of 3TPR-SPY and found 2, SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20, that showed stronger inhibition of SPY self-fucosylation than SOFTI (Fig. 5, B and C). SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20 also showed stronger binding to SPY in BLI assays, with Kd = 6.31 μM and 2.31 μM, respectively (Fig. 5, D and E).

Figure 5.

Identification of SOFTI derivatives as SPY inhibitors. A) Docking simulation of the interactions between SOFTI derivatives and SPY; the S score indicates the calculated affinity: lower S score indicates stronger predicted interactions. Number of interactions (# interactions) stands for the number of interacting amino acid residues within the ligand binding pocket of SPY. B) Immunoblots show the effects of 100 μM of SOFTI and its derivatives on the self-fucosylation (AAL-biotin) of recombinant 3TPR-SPY proteins. C) Chemical structures for SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20, marked by red arrows in A) and B). BLI assays of the interaction kinetics of SOFTI-D1 D) and SOFTI-D20 E) with SPY. The vertical dashed line indicates the boundary between binding and dissociation processes. F) The effect of 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM of SOFTI-D1 or SOFTI-D20 on the enzymatic activity of 3TPR-SPY. G) Immunoblots showing the effects of 10 μM (+) or 30 μM (++) of SOFTI-D1 or SOFTI-D21 on the O-fucosylation level (AAL-biotin) of NEDD1-myc proteins immunoprecipitated (IP) from 7-d-old transgenic NEDD1-myc/nedd1 seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium supplemented with inhibitors. NEDD1-myc/nedd1 spy-23 (spy) was used as a negative control. H) Phenotypes of Col-0 and spy-4 seedlings grown under long-day conditions for 4 d on solid 1/2 MS medium containing 1% sucrose and then transferred into liquid ½ MS medium supplemented with 1% sucrose (+) or mannitol (−) and 30 μM of SOFTI-D1 or SOFTI-D20 or DMSO only (−) in darkness for 5 d. Bar = 1 cm. I) Statistical analysis of the phenotype shown in H), n ≥ 15 seedlings. FC, fold change. The center line refers to the median, box limits refer to the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers mark the maximum and minimum.

We, therefore, performed molecular docking and superposed SOFTI-D1/D20 with GDP-fucose to understand the structural basis for inhibitor binding. SOFTI-D1 appears to occupy the same site in the pocket as SOFTI, but SOFTI-D20 competed with the GDP part of the donor substrate GDP-fucose (Supplemental Fig. S3, B and C). Although both derivatives showed more prominent inhibitory effects in vitro than SOFTI (Fig. 5F), their effects on the in vivo O-fucosylation of NEDD1 and on sugar-dependent growth appear comparable with SOFTI (Fig. 5, G to I). This is possibly due to their lower cell permeability compared with SOFTI. According to Crippen's fragmentation (Ghose and Crippen 1987), the LogP values of SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20 (3.05 and 4.09, respectively) are greater than that of SOFTI (2.58), suggesting that they have lower cell permeabilities than SOFTI.

SOFTI and SOFTI-D1 specifically inhibit the growth of sec-2 mutant

To test the relative specificity of the 3 inhibitors, we grew wild-type, spy, and sec mutants on solid media containing various concentrations (0, 3, 10, and 30 μM) of SOFTI, SOFTI-D1, and SOFTI-D20 (Fig. 6). A specific SPY inhibitor is expected to cause no phenotypic changes in the spy null mutant. Based on the known lethal phenotype of spy sec double mutants, we expect that the inhibition of SPY in sec and inhibition of SEC in spy would inhibit growth and the inhibition of other enzymes would cause phenotypic changes in wild-type and both mutants. Our results show that the root growth of sec-2 was inhibited by all inhibitors at all the concentrations tested, indicating they inhibit SPY. At 30 μM, SOFTI-D20 severely inhibited the growth of both wild-type and spy-4, suggesting that high concentrations of SOFTI-D20 have side effects independent of SPY and SEC. By contrast, SOFTI and SOFTI-D1 did not affect the normal development of wild-type and the spy-4 mutant (Fig. 6), indicating that they do not inhibit SEC or other proteins required for normal growth under these conditions. Indeed, in vitro O-GlcNAcylation assays showed that SOFTI does not inhibit the SEC-catalyzed O-GlcNAcylation of substrate proteins (Supplemental Fig. S5). Together, these results show that SOFTI and SOFTI-D1 are specific inhibitors of SPY O-fucosyltransferase.

Figure 6.

The specificity of SOFTIs. A) Phenotypes of Col-0, spy-4, and sec-2 mutant seedlings grown on ½ MS medium containing 1% mannitol, 0.8% agar, and the indicated concentrations of inhibitors (SOFTI, SOFTI-D1, and SOFTI-D20) for 8 d. DMSO was the solvent and was used as the mock control. Bars = 1 cm. B) Statistical analysis of the phenotype shown in A). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, and unlabeled groups indicate no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) compared with the DMSO-treated control seedlings; significance levels were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA (Tukey's multiple comparison test), n > 20. Error bars indicate ± Sd.

Discussion

Protein posttranslational modifications by O-glycosylation are important cellular signal transduction mechanisms essential for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis in both animals and plants (Hart et al. 2007; Bi et al. 2023; Zentella et al. 2023). While the single mutants of the Arabidopsis O-glycosyltransferases SEC and SPY show various mild developmental defects, the double mutant is embryonic lethal (Hartweck et al. 2002). Conditional inhibition is required to further study the function of O-glycosylation, particularly in postembryonic development stages. Small molecule inhibitors of human OGT have been well-characterized and widely used (Ortiz-Meoz et al. 2015; Martin et al. 2018). We found, however, that these OGT inhibitors do not inhibit SPY even at high concentrations (Supplemental Fig. S6, A to C), reflecting the need to develop small-molecule inhibitors for the plant O-glycosyltransferases. Therefore, using virtual screening followed by in vitro and in vivo tests, we identified SOFTI, a small-molecule inhibitor of SPY.

Our virtual screening identified candidate chemicals that bind to the catalytic pocket of SPY. In vitro experiments, including TSA and BLI assays, demonstrate that SOFTI directly interacts with SPY (Fig. 1). Further, the molecular docking of SOFTI to the catalytic pocket of SPY showed that SOFTI interacts with multiple key amino acid residues that interact with the donor substrate GDP-fucose according to the crystal and cryo-EM structures (Zhu et al. 2022; Kumar et al. 2023; Fig. 4, A to D). These include K665, which is essential for both enzyme activity and SOFTI binding (Fig. 4, E and F). By screening derivatives of SOFTI virtually and then experimentally, we identified SOFTI-D1 and D20 as more potent inhibitors of SPY (Fig. 5).

The SPY inhibitor activities of SOFTI, SOFTI-D1, and SOFTI-D20 were confirmed by in vitro and in vivo assays. We show that SOFTIs inhibit SPY's self-fucosylation activity and SPY O-fucosylation of NEDD1 in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 2 and 5). SOFTI treatments of wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings reduced protein O-fucosylation and caused spy-like phenotypes including early seed germination, increased root hair density, sugar-insensitive growth arrest in the dark, and growth arrest in the sec mutant background (Figs. 3 and 5). Importantly, SOFTI and SOFTI-D1 caused no significant phenotypic change in the spy mutant (Figs. 3, 5, and 6), whereas SOFTI-D20 inhibited the growth of the spy mutant at a high concentration of 30 mM, indicating that SOFTI and SOFTI-D1 are specific SPY inhibitors with little SPY-independent effects on plant growth but SOFTI-D20 can have off-target effects. Considering that the spy sec double mutation is lethal, inhibition of SPY in the sec mutant background, or inhibition of SEC in spy, is expected to cause growth arrest. SOFTIs caused growth arrest in sec but not in spy compared with wild type (Fig. 6), indicating that SOFTIs inhibit SPY but not SEC. Indeed, in vitro O-GlcNAcylation assays showed no effect of SOFTI on the SEC-catalyzed O-GlcNAcylation of substrate proteins (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Structure-based virtual screening greatly simplifies the candidate selection process compared with the traditional phenotype-based or assay-based high-throughput screening approaches. However, virtual screening relies on a high-quality 3D structure of the target protein. As crystal structures remain unavailable for most plant proteins, virtual screening has not been widely used for plant research. Recently, structural predictions have become available from AlphaFold. Whether the structures predicted by AlphaFold are accurate and reliable enough for virtual screening remains unclear, as conflicting conclusions have been reported (Wong et al. 2022; Scardino et al. 2023). Our study represents a successful case using AlphaFold-predicted protein structure to identify small-molecule inhibitors.

Our study illustrates how the development of computational structural biology can advance the discovery of chemical tools for plant biology and agriculture. The crystal and cryo-EM structures of SPY have been recently determined (Zhu et al. 2022; Kumar et al. 2023), providing a timely opportunity to compare predicted and solved structures. Structure-based superposition of the crystal structure and the AlphaFold-predicted structure of the full-length SPY showed an overall root means square deviation (RMSD) of 9.339 Å, indicating a substantial deviation between the 2 structures (Supplemental Fig. S7, A and B). However, the superposition of only the catalytic domain of SPY resulted in an RMSD of 0.665 Å between the AlphaFold-predicted and the solved crystal structures or of 0.61 Å between the AlphaFold-predicted and Cryo-EM structures (Supplemental Fig. S7C), which are similar to the median backbone accuracy of overall AlphaFold structures (0.96 Å RMSD95; Jumper et al. 2021). Consistent with the accuracy of the simulated structure and docking simulation, some residues of SPY predicted to interact with SOFTI were found to form hydrogen bonds with GDP-fucose in the cryo-EM structure (Fig. 4D). While no crystal or Cryo-EM structure is available for most plant proteins, our results indicate that the structures predicted by AlphaFold provide a viable option for virtual screening for chemical binders. As AlphaFold predicts the structure of all proteins, virtual screening, as illustrated in our study, will have a broad impact on plant science.

SOFTI is a useful tool for functional studies of O-fucosylation in plants. For example, when combined with genetic mutants, chemical inhibitors applied spatiotemporally can overcome the lethality problem and uncover the postembryonic functions shared by SPY and SEC. The rapid inhibition of SPY by a small molecule inhibitor will also enable the analysis of the dynamics of molecular and cellular responses, such as transcriptomic and proteomic responses, to the alteration of protein O-fucosylation in vivo. Furthermore, the residues in the Arabidopsis SPY ligand-binding pocket involved in GDP-fucose–binding and SOFTI-docking are conserved. Consistent with the idea that this conservation is functionally significant, SOFTI showed a similar growth-inhibition effect in tomato as in Arabidopsis (Fig. 4).

SOFTI thus can be used as a selective inhibitor of O-fucosyltransferases in agriculturally important plants, where spy mutants are mostly lacking, enabling broad functional studies of O-fucosylation as an essential sugar-sensing mechanism. O-fucosylation plays an important role in plant development, and the loss of SPY activity leads to important agricultural phenotypes such as enhanced seed germination, early flowering, as well as increased drought tolerance (Silverstone et al. 2007; Qin et al. 2011). Therefore, it is conceivable that SOFTI and its derivatives can be developed into agrochemicals that improve food production, in addition to their application in basic plant biology research.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and culture conditions

All Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) materials used in this study are in Col-0 accession and grown in a long-day growth chamber under a 16 h light and 8 h dark photoperiod (with light intensity about 82 μmol m−2 s−1 from fluorescent bulbs) at 22 °C. The seeds were surface-sterilized by immersing in 75% (v/v) ethanol for 10 min followed by rinsing with autoclaved water for 3 times and then placed on half-strength MS (1/2MS) culture medium containing 1.2% (w/v) agar and supplied with 1% mannitol or 1% sucrose as indicated. The T-DNA insertion lines spy-4 (Bi et al. 2023), spy-23, sec-2 (Bi et al. 2021), and transgenic line NEDD1-myc/nedd1 (Zeng et al. 2009) have been described previously. The NEDD1-myc/nedd1 spy-23 transgenic line was generated via genetic crossing.

Plasmid construction

The coding sequences of full-length SPY and the truncated 3TPR-SPY were amplified with primers shown in Supplemental Table S1. The PCR amplified sequences were cloned onto the pET28sumo expression vector with a 6xHis-SUMO tag at the N-terminus. The point mutant K665A SPY was generated via Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB, E0552S). All plasmids were sequenced to ensure accuracy.

Protein expression and purification

The full-length or 3TPR-truncated cDNA sequence of SPY was amplified from Arabidopsis cDNA with appropriate primers (listed in Supplemental Table S1) and cloned into the RSFDuet-SUMO vector (Wang et al. 2019), which adds a 6xHis-SUMO tag to the N-terminus of the protein of interest. The plasmid carrying SPY full-length sequence or 3-TPR truncated sequence was transformed into Rosetta DE3 E. coli strains for protein expression. The transformed bacteria were then cultured to OD = 0.8 at 37 °C and then cooled to 16 °C, followed by the addition of 300 μM (final concentration) isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). After overnight culture, the cell pellets were then collected and resuspended in 1×PBS (2.7 mM KCl, 2 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and pH = 7.4). The proteins were then affinity purified with Ni2+ columns (Invitrogen, R901-01), and the eluted proteins were further purified via gel filtration chromatography with a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). The final protein product was stored in 1×PBS at 1 mg/mL at −80 °C.

Protein TSA

Purified proteins were thawed on ice and mixed with 1× SPYRO Orange dye and compounds at the indicated concentration (1% dimethyl sulfoxide final), followed by incubation on ice for 30 min and then put into a QuantStudio Q6 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for the detection of fluorescence. The program gradually increases the sample temperature from 25 °C to 99 °C with a speed of 0.05 °C/s. The derivative of the fluorescence curve was then generated with Protein Thermal Shift software, and Boltzmann fit was utilized to determine the Tm temperature of each sample. Four technical replicates were included for each protein sample and each concentration of the compounds.

Biolayer interferometry

The BLI was performed as previously described (Xie et al. 2022) using Octet R2 Protein Analysis System (Sartorius, Fig. 1) or Gator-plus (Gator Bio. Figs. 4 and 5) with some modifications. Briefly, 100 μL of 1 mg/mL purified SPY full-length protein was biotinylated at a 1:2 (protein:biotin) ratio, and free biotin was separated with a desalting column (#G-MM-ITG, www.bomeida.com). Super Streptavidin sensors (Fortebio) were dipped into the protein solutions for 15 min for loading and then dipped into various concentrations of SOFTI (0 to 100 μM). The dissociation constant Kd was calculated via Fortebio analysis software based on the classical kinetics method (ratio of Koff/Kon values) based on global fitting of several curves generated from serial dilutions of the ligand. For Figs. 4E, 4F, 5D, and 5E, BLI was performed with a similar protocol but on Gator Plus Biosensor System (Gator Bio) with Small Molecule Analysis Probes (Gator Bio, 160011).

Molecular docking and virtual screening

The crystal structure of SPY was obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB ID: 7Y4I, and the AlphaFold-predicted structure of SPY was downloaded from https://alphafold.com. Virtual screening, protein structural superposition, and molecular docking simulations were performed with the commercial software MOE (Chemical Computing Group, 2020.09) purchased from https://www.chemcomp.com. The binding affinity of small molecules and proteins was predicted based on the Generalized Born solvation model (GBVI), which is a scoring function of the free energy of the protein bound to each molecule. For SOFTI docking with SPY protein, 1,000 random poses of SOFTI were generated and docked one-by-one into the substrate-binding pocket of SPY with the induced fit model, and the pose with the lowest estimated free energy was analyzed and displayed.

Protein immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Arabidopsis seedlings were grown on 1/2 MS plates with or without treatment for 12 d. One hundred milligrams of tissue of the whole plant seedling was harvested and ground into powder in liquid nitrogen. One hundred fifty microliters of ice-cold IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol, 0.25% v/v Triton-X 100, 0.25% v/v NP40, 1 mM PMSF, 1× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail [Thermo Scientific], 1× Pierce phosphatase inhibitor [Thermo Scientific]) was added into the powder and lysed on ice for 10 min. The samples were then ultrasonicated for 1 min with 5 s on/5 s off cycle to release nuclear proteins and centrifuged at 20,817 g (14,000 rpm) for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were then incubated with 20 µL anti-myc (Thermo Scientific, 88,843) or anti-GFP (SMART lifesciences, SM038005) magnetic beads for 1 h. After 2 rounds of washing with IP buffer, the proteins were eluted from the beads via adding 2×SDS loading buffer (60 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 25% v/v glycerol, 2% SDS, 200 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% bromophenol) and boiled at 95 °C for 10 mins.

For immunoblotting, the protein samples were loaded onto 10% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA to exclude nonspecific binding and then probed with anti-myc (Cell Signaling Technology, 9B11, 1:2000 dilution), anti-GFP (Transgene, Q20329, 1:2000 dilution), anti-SPY (PhytoAB, PHY1737S, 1:1000 dilution), anti-O-GlcNAc (Cell Signaling Technology, #9875, 1:2000 dilution), or biotinylated Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL, Vector Laboratories, ZF0305, 1:10,000 dilution) in 3% BSA. After 3 rounds of washing with 1×PBST (0.1% Tween-20), 6 min each, the membrane was then probed with antimouse, antirabbit secondary antibodies (STAR132 and STAR121, BIO-RAD, 1:5000 dilution) or Pierce HRP-conjugated Streptavidin (Thermo Scientific, 1:10,000 dilution).

SPY and SEC in vitro O-glycosyltransferase assay

To determine the O-fucosyltransferase activity of SPY, 5 μg of 3TPR-SPY recombinant protein (for the case of NEDD1-myc protein, 5 μg 3TPR-SPY protein and 5 μL of anti-myc beads were added together) was added into a 30 μL reaction volume containing 1×PBS and 5 mM MgCl2 with the compounds at indicated concentration (in 1% v/v dimethyl sulfoxide). The reagents were incubated on ice for 30 min for proper binding of the small molecules to SPY. Then, 50 μM (final concentration) of GDP-fucose was added, and the tubes were placed on a rotator for 1.5 h at 22 °C. The reaction was terminated with the addition of 2×SDS loading buffer and boiling at 95 °C for 10 min.

To determine the OGT activity of SEC, 7.5 μg of 6xHis-MBP-5TPR-SEC and 7.5 μg of GST-MKK5 recombinant protein were added into a 30 μL reaction containing PBS, 5 mM MgCl2, and various amounts of the inhibitors. The reaction was started by adding 200 μM (final concentration) of UDP-GlcNAc as the donor substrate. After incubation on a rotator for 2.5 h at 22 °C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 2×SDS loading buffer and boiling at 95 °C for 10 min. The proteins were analyzed by anti–O-GlcNAc immunoblotting.

Statistical assays

Statistical assays were conducted as described in the figure legends, and statistical data can be found in Supplemental Data Set 1.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following accession numbers: SPINDLY (SPY): AT3G11540; SECRET AGENT (SEC): AT3G04240; NEURAL PRECURSOR CELL EXPRESSED, DEVELOPMENTALLY DOWNREGULATED GENE 1 (NEDD1): AT5G05970.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Bo Liu from University of California, Davis, for sharing the NEDD1-myc/nedd1 transgenic lines.

Contributor Information

Yalikunjiang Aizezi, Department of Plant Biology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; Department of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; Institute of Plant and Food Science, Department of Biology, School of Life Sciences, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China.

Hongming Zhao, Institute of Plant and Food Science, Department of Biology, School of Life Sciences, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China.

Zhenzhen Zhang, Department of Plant Biology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Yang Bi, Department of Plant Biology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Qiuhua Yang, Institute of Plant and Food Science, Department of Biology, School of Life Sciences, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China.

Guangshuo Guo, Institute of Plant and Food Science, Department of Biology, School of Life Sciences, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China.

Hongliang Zhang, Department of Plant Biology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Hongwei Guo, Institute of Plant and Food Science, Department of Biology, School of Life Sciences, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China.

Kai Jiang, Institute of Plant and Food Science, Department of Biology, School of Life Sciences, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China.

Zhi-Yong Wang, Department of Plant Biology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Author contributions

Z.-Y.W. and Y.A. designed the research; Y.A., H.Zhao., and K.J. performed the virtual chemical screening and docking simulations; Y.A., Q.Y., and G.G. performed the experimental chemical screening and ligand-protein binding assay with supervision by H.G. and K.J.; Y.A., Q.Y., and G.G. purified the proteins for enzymatic assays; Y.A. performed the enzymatic assays with assistance from Y.B., Z.Z., and H.Z.; Y.B. and Z.Z. constructed the transgenic plant materials; Z.-Y.W. supervised the project; Z.-Y.W. and Y.A. wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified full-length SPY protein and truncated 3TPR-SPY protein.

Supplemental Figure S2. Effect of SOFTI on O-fucosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins.

Supplemental Figure S3. SOFTI-D1 and SOFTI-D20 compete with GDP-fucose for SPY binding.

Supplemental Figure S4. Chemical structures of SOFTI derivatives.

Supplemental Figure S5. SOFTI does not inhibit plant SEC.

Supplemental Figure S6. OGT inhibitors do not inhibit SPY enzyme activity.

Supplemental Figure S7. Structural superposition of the AlphaFold-predicted SPY structure and SPY crystal structure.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in molecular cloning.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Statistical information.

Funding

This work is supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM066258 (to Z.-Y.W.) and grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21907049 to K.J. and Grant No. 3191154007091740203 to H.G.).

Data availability

All data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

References

- Abdiche Y, Malashock D, Pinkerton A, Pons J. Determining kinetics and affinities of protein interactions using a parallel real-time label-free biosensor, the Octet. Anal Biochem. 2008:377(2):209–217. 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alteen MG, Tan HY, Vocadlo DJ. Monitoring and modulating O-GlcNAcylation: assays and inhibitors of O-GlcNAc processing enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021:68:157–165. 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Deng Z, Ni W, Shrestha R, Savage D, Hartwig T, Patil S, Hong SH, Zhang Z, Oses-Prieto JA. et al. Arabidopsis ACINUS is O-glycosylated and regulates transcription and alternative splicing of regulators of reproductive transitions. Nat Commun. 2021:12(1):945. 10.1038/s41467-021-20929-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Shrestha R, Zhang Z, Hsu CC, Reyes AV, Karunadasa S, Baker PR, Maynard JC, Liu Y, Hakimi A. et al. SPINDLY mediates O-fucosylation of hundreds of proteins and sugar-dependent growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2023:35(5):1318–1333. 10.1093/plcell/koad023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose AK, Crippen GM. Atomic physicochemical parameters for three-dimensional-structure-directed quantitative structure-activity relationships. 2. Modeling dispersive and hydrophobic interactions. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1987:27(1):21–35. 10.1021/ci00053a005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. Cycling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature. 2007:446(7139):1017–1022. 10.1038/nature05815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartweck LM, Scott CL, Olszewski NE. Two O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase genes of Arabidopsis thaliana L. Heynh. Have overlapping functions necessary for gamete and seed development. Genetics. 2002:161(3):1279–1291. 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Bates R, Žídek A, Potapenko A. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021:596(7873):583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Park CH, Hsu CC, Kim YW, Ko YW, Zhang Z, Zhu JY, Hsiao YC, Branon T, Kaasik K. et al. Mapping the signaling network of BIN2 kinase using TurboID-mediated biotin labeling and phosphoproteomics. Plant Cell. 2023:35(3):975–993. 10.1093/plcell/koad013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Dillard L, Li F-W, Sciandra CA, Sui N, Zentella R, Zahn E, Shabanowitz J. et al. Structure and dynamics of the Arabidopsis O-fucosyltransferase SPINDLY. Nat Commun. 2023:14(1):1538. 10.1038/s41467-023-37279-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepri A, Longo C, Messore A, Kazmi H, Madia VN, Di Santo R, Costi R, Vittorioso P. Plants and small molecules: an up-and-coming synergy. Plants (Basel). 2023:12(8):1729. 10.3390/plants12081729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SES, Tan Z-W, Itkonen HM, Duveau DY, Paulo JA, Janetzko J, Boutz PL, Törk L, Moss FA, Thomas CJ. et al. Structure-based evolution of low nanomolar O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2018:140(42):13542–13545. 10.1021/jacs.8b07328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski NE, West CM, Sassi SO, Hartweck LM. O-GlcNAc protein modification in plants: evolution and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010:1800(2):49–56. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Meoz RF, Jiang J, Lazarus MB, Orman M, Janetzko J, Fan C, Duveau DY, Tan ZW, Thomas CJ, Walker S. A small molecule that inhibits OGT activity in cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2015:10(6):1392–1397. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Kodaira KS, Maruyama K, Mizoi J, Tran LS, Fujita Y, Morimoto K, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. SPINDLY, a negative regulator of gibberellic acid signaling, is involved in the plant abiotic stress response. Plant Physiol. 2011:157(4):1900–1913. 10.1104/pp.111.187302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardino V, Di Filippo JI, Cavasotto CN. How good are AlphaFold models for docking-based virtual screening? iScience. 2023:26(1):105920. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone AL, Tseng TS, Swain SM, Dill A, Jeong SY, Olszewski NE, Sun TP. Functional analysis of SPINDLY in gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007:143(2):987–1000. 10.1104/pp.106.091025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner E, Efroni I, Gopalraj M, Saathoff K, Tseng TS, Kieffer M, Eshed Y, Olszewski N, Weiss D. The Arabidopsis O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase SPINDLY interacts with class I TCPs to facilitate cytokinin responses in leaves and flowers. Plant Cell. 2012:24(1):96–108. 10.1105/tpc.111.093518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner E, Livne S, Kobinson-Katz T, Tal L, Pri-Tal O, Mosquna A, Tarkowská D, Mueller B, Tarkowski P, Weiss D. The putative O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase SPINDLY inhibits class I TCP proteolysis to promote sensitivity to cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 2016:171(2):1485–1494. 10.1104/pp.16.00343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP. Novel nucleocytoplasmic protein O-fucosylation by SPINDLY regulates diverse developmental processes in plants. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021:68:113–121. 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, Nair S, Natassia C, Yordanova G, Yuan D, Stroe O, Wood G, Laydon A. et al. AlphaFold protein structure database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022:50(D1):D439–d444. 10.1093/nar/gkab1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Bosc C, Ryul Choi S, Boulan B, Peris L, Olieric N, Bao H, Krichen F, Chen L, Andrieux A. et al. Structural basis of tubulin detyrosination by the vasohibin-SVBP enzyme complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019:26(7):571–582. 10.1038/s41594-019-0241-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, He Y, Su C, Zentella R, Sun TP, Wang L. Nuclear localized O-fucosyltransferase SPY facilitates PRR5 proteolysis to fine-tune the pace of Arabidopsis circadian clock. Mol Plant. 2020:13(3):446–458. 10.1016/j.molp.2019.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong F, Krishnan A, Zheng EJ, Stärk H, Manson AL, Earl AM, Jaakkola T, Collins JJ. Benchmarking AlphaFold-enabled molecular docking predictions for antibiotic discovery. Mol Syst Biol. 2022:18(9):e11081. 10.15252/msb.202211081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Zhu Y, Wang N, Luo M, Ota T, Guo R, Takahashi I, Yu Z, Aizezi Y, Zhang L. et al. Chemical genetic screening identifies nalacin as an inhibitor of GH3 amido synthetase for auxin conjugation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022:119(49):e2209256119. 10.1073/pnas.2209256119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L, Liu Y, Xu S, Xiao J, Wang B, Deng H, Lu Z, Xu Y, Chong K. Arabidopsis O-GlcNAc transferase SEC activates histone methyltransferase ATX1 to regulate flowering. EMBO J. 2018:37(19):e98115. 10.15252/embj.201798115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SL, Chalkley RJ, Maynard JC, Wang W, Ni W, Jiang X, Shin K, Cheng L, Savage D, Huhmer AF. et al. Proteomic analysis reveals O-GlcNAc modification on proteins with key regulatory functions in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017:114(8):E1536–E1543. 10.1073/pnas.1610452114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng CJ, Lee YR, Liu B. The WD40 repeat protein NEDD1 functions in microtubule organization during cell division in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009:21(4):1129–1140. 10.1105/tpc.109.065953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella R, Hu J, Hsieh WP, Matsumoto PA, Dawdy A, Barnhill B, Oldenhof H, Hartweck LM, Maitra S, Thomas SG. et al. O-GlcNAcylation of master growth repressor DELLA by SECRET AGENT modulates multiple signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2016:30(2):164–176. 10.1101/gad.270587.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella R, Sui N, Barnhill B, Hsieh WP, Hu J, Shabanowitz J, Boyce M, Olszewski NE, Zhou P, Hunt DF. et al. The Arabidopsis O-fucosyltransferase SPINDLY activates nuclear growth repressor DELLA. Nat Chem Biol. 2017:13(5):479–485. 10.1038/nchembio.2320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella R, Wang Y, Zahn E, Hu J, Jiang L, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Sun TP. SPINDLY O-fucosylates nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins involved in diverse cellular processes in plants. Plant Physiol. 2023:191(3):1546–1560. 10.1093/plphys/kiad011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Wei X, Cong J, Zou J, Wan L, Xu S. Structural insights into mechanism and specificity of the plant protein O-fucosyltransferase SPINDLY. Nat Commun. 2022:13(1):7424. 10.1038/s41467-022-35234-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.