Abstract

CD40-CD40L interactions are critical for controlling Pneumocystis infection. However, which CD40-expressing cell populations are important for this interaction have not been well-defined. We used a cohousing mouse model of Pneumocystis infection, combined with flow cytometry and qPCR, to examine the ability of different populations of cells from C57BL/6 mice to reconstitute immunity in CD40 knockout (KO) mice. Unfractionated splenocytes, as well as purified B cells, were able to control Pneumocystis infection, while B cell depleted splenocytes and unstimulated bone-marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were unable to control infection in CD40 KO mice. Pneumocystis antigen-pulsed BMDCs showed early, but limited, control of infection. Consistent with recent studies that have suggested a role for antigen presentation by B cells, using cells from immunized animals, B cells were able to present Pneumocystis antigens to induce proliferation of T cells. Thus, CD40 expression by B cells appears necessary for robust immunity to Pneumocystis.

Introduction

Pneumocystis jirovecii causes life-threatening disease, Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), in immunocompromised individuals [1, 2]. Although historically associated with HIV/AIDS patients, PCP also affects individuals receiving immunosuppressive therapy for a variety of medical conditions, as well as individuals with congenital immunodeficiencies, especially severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) or X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome, which is due to a defect in CD40-CD40L interactions [3–6].

There are multiple Pneumocystis species, each of which appears to infect one or a limited number of closely related mammalian species [7]. Mouse models of P. murina infection have provided important insights into relevant host-organism interactions [8]. Pneumocystis enters the host via the respiratory tract and attaches primarily to type I alveolar epithelial cells [9]. Antigen-presenting cells presumably take up and process Pneumocystis antigens, such as surface glycoproteins, then migrate to peripheral lymphoid organs and present antigen to CD4+ T cells via the MHC II complex. For a robust T cell response, multiple interactions with costimulatory molecules need to occur between a T cell and an antigen presenting cell, resulting in T cell activation.

CD4+ T cells are essential for clearing Pneumocystis, and CD40-CD40L interactions appear to play a critical role [10–14]. We and others have previously demonstrated that infection of CD40 knockout (CD40 KO) or CD40L knockout (CD40L KO) mice with P. murina results in uncontrolled infection and eventual death, supporting the importance of these interactions in clearing Pneumocystis infection [12, 14, 15]. Microarray studies from our group have demonstrated largely absent immune responses in CD40L KO mice at a time that robust responses developed in immunocompetent mice following infection, suggesting an early role for the CD40-CD40L interaction in controlling infection [13].

CD40L is expressed predominantly on activated T cells, but during inflammation can also be expressed by activated B cells, monocytes, basophils, mast cells, natural killer cells, and platelets [16, 17]. CD40 is expressed primarily by B cells, dendritic cells and macrophages, all of which can function as antigen presenting cells (APCs) [16, 17]. B cells have been increasingly found to play a critical role in host immune responses to Pneumocystis, potentially for their role as APCs in addition to their role as antibody producers [18–22].

Given the importance of CD4+ T cells and the CD40-CD40L interaction to the control and clearance of Pneumocystis, we sought to determine, in a mouse model, which cell types expressing CD40 are the most critical to generating an effective immune response against Pneumocystis infection.

METHODS

Animals

Healthy C57BL/6 mice (expressing CD45.2) were obtained from the National Cancer Institute. CD40 ligand knock-out mice, (CD40L KO, strain B6, 129S-Tnfsf5tm1lmx/J), CD40 knock-out mice (CD40 KO, strain B6, 129P2-Cd40tm1Kik/J) and C57BL/6 mice expressing CD45.1 (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mouse strains were subsequently bred at the NIH Clinical Center animal facility, Bethesda, Maryland. Mice were housed in microisolator cages and kept in ventilated racks. All animal work was performed under an animal study protocol approved by the NIH Clinical Center Office of Animal Care and Use.

Experimental design

We utilized a model of Pneumocystis infection that simulates naturally acquired infection [13, 15, 23]. CD40 KO mice were co-housed with a P. murina-infected CD40L KO seeder mouse, with a maximum of 11 animals per cage. Cells from naïve C57BL/6 mice, expressing CD45.1 as a congenic marker, were injected by tail-vein, as described below, into recipient CD40 KO mice expressing CD45.2 at ~20–27 days after the start of cohousing. At ~35, 65 and 90 days post-initial exposure, CD40 KO mice were sacrificed and spleens, blood, and lungs were collected. Because of the limited numbers of mice that could be housed per cage, and the need to co-house mice that received cells together with mice that received only saline, to ensure similar exposure to the seeders, data from multiple replicate cages were combined.

Adoptive transfer of splenic cells and B cells

Immune reconstitution of CD40 KO mice was performed by tail vein injection. Briefly, spleens were collected from naïve C57BL/6 (CD45.1+) and a single cell suspension was obtained by incubation with Liberase Blendzyme 3 (Roche, Bradford, CT) and DNase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 10 minutes at 37°C, followed by washing and removal of erythrocytes by ACK lysis buffer. Cells were counted and re-suspended in PBS, and splenocytes (~50 ×106/mouse in 300 μl) were injected by tail vein into CD40 KO mice that had been exposed to P. murina for ~3–4 wks.

CD19+ B cells were purified by positive magnetic separation using CD19 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Gaithersburg, MD) and MS or LS columns, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For CD19-depleted cells, the unlabeled cells that passed through the column during CD19+ cell purification were collected and further purified by application onto an LD column (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells derived from 3–4 mice were utilized in order to inject ~30–50×106 CD19+ cells/mouse or 15–25 ×106 CD19− cells/mouse in 300 μl PBS. Control mice were injected with 300μl of PBS alone.

Because tail vein injection was not always successful, and CD45.1+ cells were easily detectable in most mice that received splenic cells, data from mice scheduled to receive cells that had no detectable CD45.1+ cells in the lungs or spleen were excluded from analysis.

Adoptive transfer of dendritic cells

Femurs collected from C57BL/6 WT mice expressing CD45.1 were flushed to obtain bone marrow cells, which were washed twice, then incubated in complete differentiation medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 5 mM glutamine (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), 50 μM 2-ME (Sigma) and 30 ng/ml GM-CSF (Peprotech, Cranbury, NJ)), which was replaced every 2–3 days, to generate bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) [24, 25]. Non-adherent and loosely adherent cells were collected after 7–8 days and the immature BMDCs were magnetically sorted based on the expression of CD11c. Briefly, the cells were counted and incubated with mouse CD11c magnetic beads (Miltenyi, Biotec) for 15 minutes at 4°C. After washing, the cells were applied to LS columns with a pre-filter (Miltenyi, Biotech) and magnetically sorted following the manufacturer’s instructions. Eluted CD11c+ cells were washed and then either rested or primed with 20 μg/ml crude P. murina antigen in complete differentiation medium overnight at 37°C. For antigen preparation, Pneumocystis organisms were partially purified by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation [26], then disrupted with glass beads followed by sonication; the supernatant remaining after centrifugation was utilized as the antigen. BMDCs were collected and re-suspended in 300 μl of PBS. Each CD40 KO mouse received ~ 2.5–10 × 106 BMDCs, or PBS alone by tail vein injection. An aliquot was saved for flow cytometry analysis to verify the maturation stage of the BMDCs. Because no CD45.1+ cells were detected in mice receiving BMDCs, all mice were included in the analyses.

Quantification of P. murina organism load

DNA was extracted from mouse lung tissue (stored at −80°C), using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Intensity of P. murina infection was quantitated by qPCR using a single-copy gene (dhfr), as previously described [15]; organism loads are expressed as dhfr copies per mg lung tissue.

Detection of anti-P. murina antibodies by ELISA

Serum anti-P. murina antibodies were detected by ELISA using a crude P. murina antigen, prepared as noted above, as previously described [27]. An optical density > 0.2 after subtracting background was used as a cutoff for a positive antibody response.

Flow cytometry analysis of lung and spleen

Freshly removed lungs were incubated with collagenase (Gibco, Waltham, MA) and DNase (Sigma) at 37°C for 30 minutes to obtain single cell suspensions. After washing the cells with RPMI-10% FCS (Invitrogen), erythrocytes were removed with ACK lysis buffer and cells were washed twice more. Spleens were processed as described above to obtain single cells suspension. The cell suspensions (lung or spleen) were filtered with cell strainer, counted, and stained with LIVE/DEAD fixable Near-IR or violet dead cell kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). The cells were stained with the following fluorochrome-conjugated anti-murine antibodies: CD3-FITC or CD3-PE, CD4-PerCP, CD8-PerCP, CD19-PE or CD19-APC, CD11c-PE, CD11b-PerCP, CD45.1-PerCP-Cy5.5, and CD45.2 APC (all BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and run on a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences); data were analyzed using FlowJo (BD Life Sciences, Ashland, OR).

In vitro antigen presentation assays

To evaluate antigen presentation in vitro, mice were immunized with 20 μg of a crude P. murina antigen, prepared as noted above, together with Freund’s complete (first immunization) or incomplete (booster immunizations) adjuvant; 3 booster immunizations were administered approximately 2 weeks apart. Mice immunized with adjuvant alone served as controls. Spleen cells were processed as above, and cells from 3–4 mice were combined for sorting by flow cytometry, which was performed by the NHLBI core flow cytometry facility. The following fluorochrome-conjugated anti-murine antibodies: CD3-FITC, CD4-PE-Cy7, CD19-PE, CD11c-APC, and CD11b-APC (all BD Biosciences) together with LIVE-DEAD violet dead cell stain (Invitrogen) were utilized for sorting. Sorted CD4+ T cell and B cell purity was >95%, and DC/monocyte (CD11b+ and/orCD11c+) purity was ~85%, as confirmed by flow cytometry. To evaluate antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells, CD4+ T cells (CD3+CD4+) were cultured either alone or with B cells (CD19+) or combined DCs/monocytes (CD11c+ and/or CD11b+) in the presence of 20 μg/ml of a crude P. murina antigen, 10 μg/ml of purified P. murina major surface glycoprotein (Msg) prepared as previously reported [27], or no antigen, for 5 days, after which proliferation was measured using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proliferation results are presented as the stimulation index (mean proliferation, in relative light units (RLU), for antigen co-incubation divided by the mean RLU for the no antigen control).

Statistics

For cell transfer studies, organism loads at individual time-points for mice receiving cell transfers were compared to organism loads in control mice, and for in vitro proliferation studies, the RLU for cells with antigen co-incubation were compared to the RLU for the no antigen control, using unpaired, 2-sided Student’s T-test, using Prism (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA) or Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

Spleen cells from wild type mice can reduce Pneumocystis burden in the lungs of CD40 KO mice

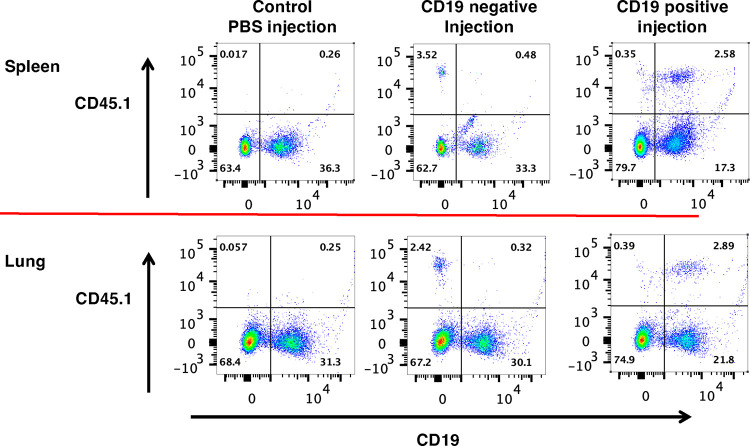

To determine whether reconstituting the CD40-CD40L interaction in immune cells is enough to control Pneumocystis infection, we adoptively transferred splenic cells from naïve wild-type C57BL/6 mice into CD40 KO mice after approximately 3 weeks of continuous co-housing with a P. murina-infected seeder. In preliminary experiments, transferring splenic cells simultaneously with initial exposure to the seeder did not impact infection, and no CD45.1+ cells were detected in the lungs of reconstituted mice. CD45.1+ cells were easily detected in both the lungs and spleen of mice following cell transfer at 3 weeks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow cytometry analysis of lung and spleen cells following transfer of CD19− cells or CD19+ B cells; gating was on live cells, then lymphocytes, then CD19 and CD45.1. Representative results are shown for spleen and lung cells from CD40 KO mice exposed to a Pneumocystis-infected seeder for 65 days. The exposed mice were reconstituted at day 20 with PBS (control) or with CD19+ B cells (positive), or with CD19 depleted (negative) spleen cells. Transferred B cells (CD45.1+/CD19+) were detected in the spleen and lung of the mouse that received CD19+ B cells, while transferred non-B cells were detected in the mouse that received cells that had been depleted of CD19+ B cells. Neither population was detected in the mouse that had received PBS.

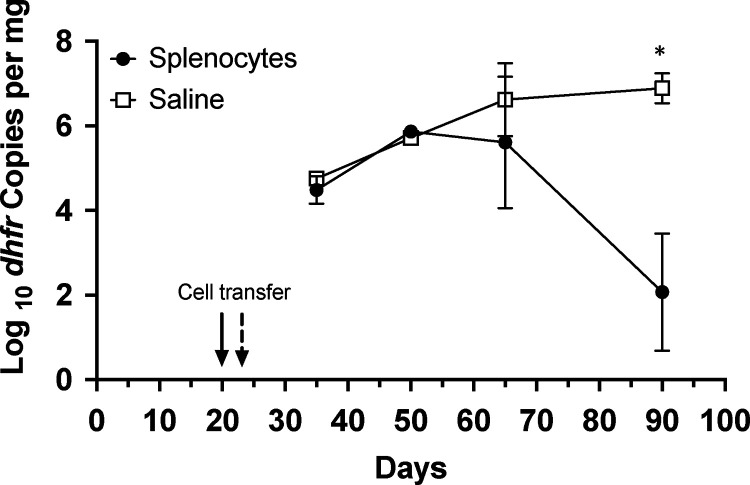

By 65 days post initial exposure, CD40 KO mice receiving wild-type splenic cells had a trend toward reduced P. murina compared to mice receiving saline (Figure 2). By 90 days, P. murina burden was significantly reduced (p=0.02) in the group receiving splenic cells compared to controls. As noted above, transferred CD45.1+ cells were detected in the spleen as well as in the lungs of recipient animals (Figure 1), and anti-Pneumocystis antibodies were detected in splenic cell recipients but not controls by days 65 and 90 (data not shown). These data demonstrate that reconstitution of the CD40-CD40L interaction by splenic cells protects CD40 KO mice from progressive P. murina infection.

Figure 2.

Transfer of splenocytes controls P. murina infection in CD40 KO mice. CD40 KO mice were cohoused with a P. murina infected seeder beginning at day 0. At day 20 (Cage 1) or 24 (cage 2) mice were injected via tail-vein with either PBS or ~50 million splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice. Organism loads were deteremined by qPCR targeting the single copy dfhr gene, and are expressed as dhfr copies per mg lung tissue. Data represent the geometric mean ± SD for 2–4 mice per time-point for the splenocyte group, and 1 (day 50) to 2 mice per time-point for the PBS control group. P value is shown for the difference between the 2 groups, using Student’s unpaired t-test. *, p<0.05

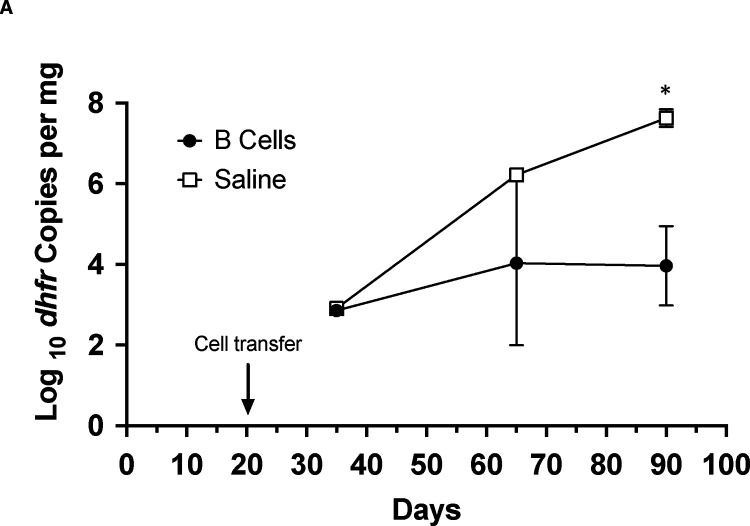

CD19+ B cell transfer is sufficient to reduce Pneumocystis burden in CD40 KO mice

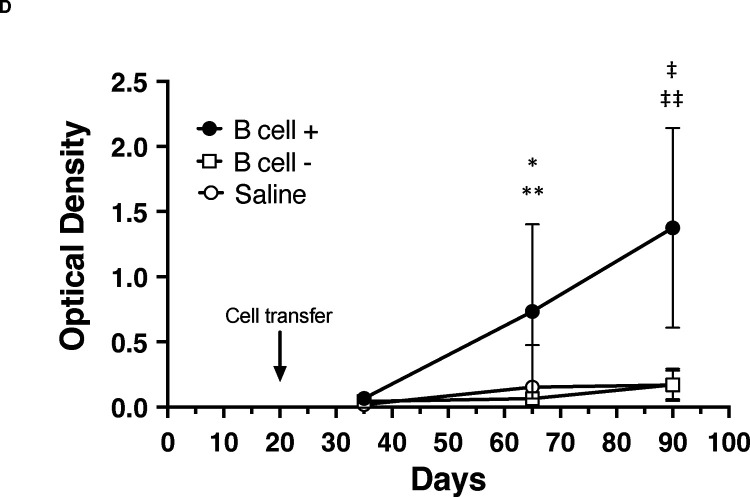

Recently, B cells were shown to have potential additional roles, aside from antibody production, in controlling Pneumocystis infection, including antigen presentation, resulting in priming of CD4+ T cells and regulating the T helper response [19–22, 28]. Transfer of wild-type CD19+ B cells alone was able to control infection, with a nearly 4 log decline in organism load by day 90 compared to saline controls (Figure 3A). To explore this further, we adoptively transferred wild-type CD19+ cells or CD19− cells into CD40 KO mice approximately three weeks after initial exposure to P. murina; by 65 days post initial exposure, CD19+ B cells again resulted in a significant decline in Pneumocystis burden compared to either CD19− cells or saline (Figure 3B). This difference was more pronounced by 90 days post infection, with a nearly 3 log decline. Donor cells (CD45.1+) could be detected in both the lungs and spleens of mice that received either CD19+ or CD19− cells but not in the mice that received saline (Figure 1). No differences in CD4+ or CD8+T cell numbers were seen among the different groups at either day 65 or day 90 (Figure 3C). Furthermore, an increase in serum anti-Pneumocystis Ig levels was present in the CD40 KO mice that received CD19+ cells but not in those that received CD19− cells or saline alone, confirming reconstitution of an anti-P. murina humoral response (Figure 3D). Together, these data demonstrate that CD19+ B cells play a major role in controlling and clearing Pneumocystis infection via a mechanism mediated by the CD40-CD40L interaction, while CD19− cells, which would include DCs, macrophages, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as other cell types, were unable to control infection.

Figure 3.

Transfer of B cells is sufficient to control P. murina infection in CD40 KO mice.

A. CD40 KO mice were cohoused with a P. murina infected seeder beginning at day 0. At day 20 mice were injected via tail-vein with either PBS or ~28 million CD19+ B cells from C57BL/6 mice. For A and B, organism loads were deteremined by qPCR targeting the single copy dfhr gene, and are expressed as dhfr copies per mg lung tissue. Data represent the geometric mean ± SD for 2–3 mice per time-point for the splenocyte group, and 1 (days 25 and 65) to 2 (day 90) mice per time-point for the PBS control group. Student’s unpaired t-test was used to compare the groups at each time-point. *, p=0.02

B. CD40 KO mice cohoused as above received either CD19+ B cells (B cell+, ~50 million cells/mouse), splenocytes that had been depleted of CD19+ B cells (B cell-, ~15–25 million cells/mouse) or saline at day 20. For these studies the focus was on later time-points (days 65 and 90), when the differences were seen in the prior studies, to allow for greater numbers of mice at each of these time-points, given the restrictions on the number of mice permitted per cage. In one experiment, no flow data were available due to technical difficulties at the day 65 timepoint; all animals from that time-point were included in the analysis. Data represent the geometric mean ± SD; number of mice per time-point is as follows: day 35, n=1 for each group; day 65, 7 to 12 per group; day 90, 6 to 9 per group. Student’s unpaired t-test was used to compare the different groups at each time-point. *, p=0.02 for B cell+ vs B cell−; **, p=0.02 for B cell+ vs saline; ‡, p=0.005 for B cell+ vs B cell−; ‡ ‡, p=0.0002 for B cell+ vs saline.

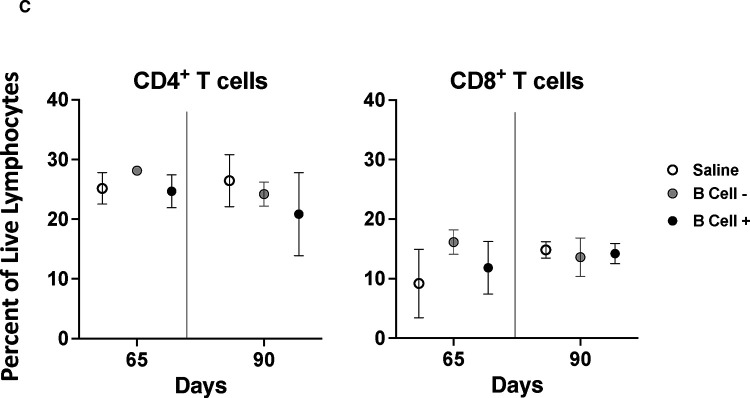

C. CD4+ (left) and CD8+ (right) T cells, as determined by flow cytometry and shown as a percent of live lymphocytes, for the 3 groups at days 65 and 90. Symbols represent mean, error bars represent standard deviation. No significant differences were seen among the groups at either time-poiint.

D. Anti-Pneumocystis antibodies, as determined by ELISA, for the animals in B, demonstrated that mice receiving CD19+ B cells developed antibodies by day 65 with a further increase by day 90, while no antibodies developed in the other 2 groups. Data represent the mean ± SD. Student’s unpaired t-test was used to compare the different groups at each time-point. *, p=0.02 for B cell+ vs B cell−; **, p=0.03 for B cell+ vs saline; ‡, p=0.001 for B cell+ vs B cell−; ‡ ‡, p=0.0003 for B cell+ vs saline.

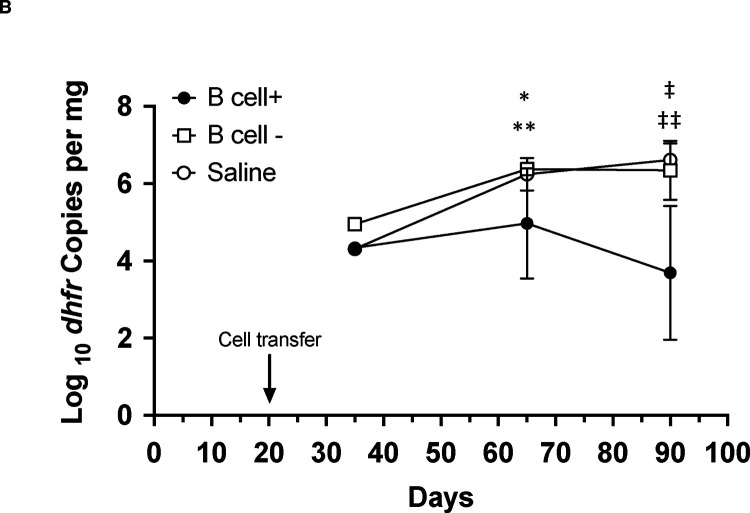

BMDC cell transfer provides limited control of Pneumocystis burden in the CD40 KO mouse model

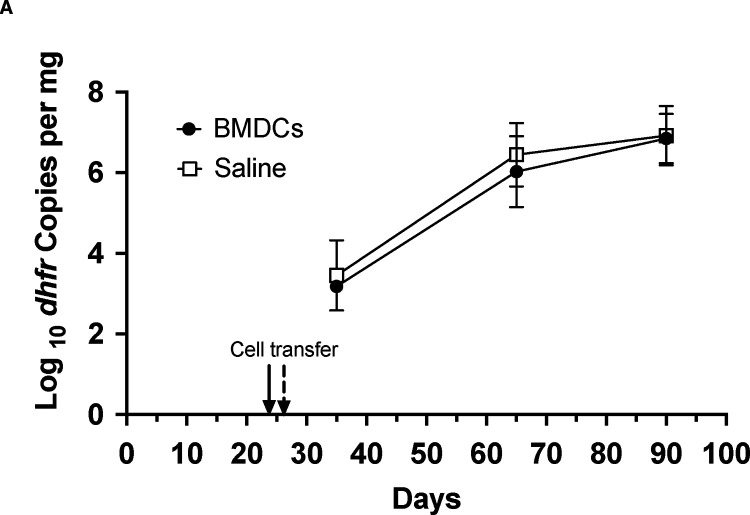

In mice, as in humans, a major cell subset responsible for presenting antigen to T and B cells is the DC population. DCs increase their surface expression of CD40 along with other co-stimulator molecules following activation by antigen stimulation, aiding in antigen presentation and full stimulation of B or T cells. In order to elucidate the contribution of CD11c+ cells to control of Pneumocystis infection via CD40-CD40L interaction, we adoptively transferred unprimed wild-type BMDCs into CD40 KO mice approximately 3 weeks after initial exposure to P. murina. There was no significant difference in P. murina burden in the lungs of CD40 KO that received CD11c+ cells compared to saline alone, at any of the three time points assessed (Figure 4A). Notably, no transferred BMDCs were detected by flow cytometry in either the lungs or spleens of these mice.

Figure 4.

Transfer of BMDCs is insufficient to control P. murina infection in CD40 KO mice.

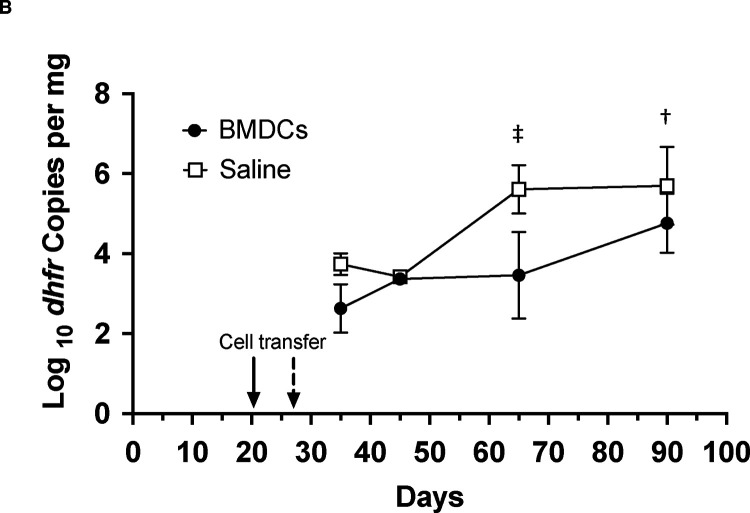

A. CD40 KO mice were cohoused with a P. murina infected seeder beginning at day 0. At day 24–26 mice were injected via tail-vein with either PBS or ~2.5–12 million BMDCs from C57BL/6 mice. For A and B, organism loads were deteremined by qPCR targeting the single copy dfhr gene, and are expressed as dhfr copies per mg lung tissue. Data represent the geometric mean ± SD for 2–5 mice per time-point for the BMDC group, and 2–3 mice per time-point for the PBS control group.

B. CD40 KO mice cohoused as above received either PBS or 10 million antigen-primed BMDCs at day 20 (5 cages) or 27 (1 cage); the BMDCs had been incubated with a crude P. murina antigen overnight prior to trasfer. For the latter cage one mouse from each group was harvested at day 45 rather than day 35 as the earliest time-point. For the other times, data represent the geometric mean ± SD for 4–15 mice per time-point for the BMDC group, and 2–11 mice per time-point for the PBS control group. Student’s unpaired t-test was used to compare the groups at each time-point. †, p=0.01; ‡, p=0.001

Since antigen stimulation is critical to CD40 expression on DCs and may aid in DC trafficking, we repeated the previous experiments with BMDCs that were primed with Pneumocystis antigen overnight. Priming resulted in a delay in the increase of P. murina infection in CD40 KO mice compared to saline alone, with an ~2 log decrease at 65 days, but only an ~1 log decrease at day 90 (Figure 4B). Collectively, this data suggests that while CD11c+ DCs may contribute to the CD40-CD40L interaction associated with clearance of Pneumocystis infection, the contribution is modest and on its own not adequate to have a major impact on the outcome of infection in this model.

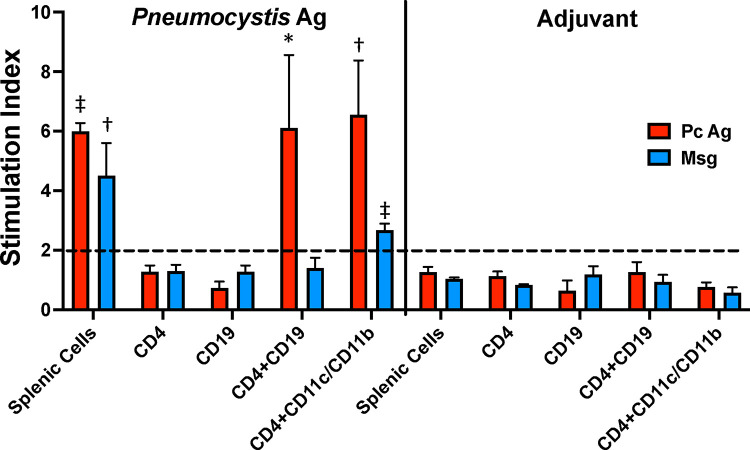

In vitro antigen presentation

To determine if B cells can serve as antigen-presenting cells for Pneumocystis antigens, we utilized an in vitro proliferation assay to examine the ability of sorted CD4+ T cells to proliferate when incubated with a crude Pneumocystis antigen preparation or with purified Msg (the most abundant surface protein of Pneumocystis [29, 30]), either alone or when combined with purified CD19+ B cells, or a combination of CD11b+ and/or CD11c+ DCs and monocytes. Cells from animals immunized with adjuvant alone were unable to proliferate in response to either antigen, likely because P. murina-specific CD4+ T cells are rare in naïve mice. As shown in Figure 5, splenocytes from mice immunized with P. murina antigens proliferated in response to either antigen preparation. CD4+T cells alone were unable to proliferate to either antigen. However, there was proliferation to a crude Pneumocystis antigen when CD4+T cells were co-incubated with B cells or DCs/monocytes. Intriguingly, Msg induced proliferation when presented by DCs/monocytes, but not when presented by B cells.

Figure 5.

B cells can present P. murina antigens in vitro.

A cell proliferation assay was used to determine if Pneumocystis antigens, presented by B cells or dendritic cells plus monocytes, could induce CD4+ T cells to proliferate. Spleen cells from 3–4 C57BL/6 mice that had been previously immunized with 20 μg crude P. murina antigen or adjuvant alone were combined and purified by cell sorting to provide populations of CD4+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and CD11c+/CD11b+ DCs and monocytes. Purified CD4+ T cells (44,000/well) were cultured for 5 days either alone or co-incubated with B cells (50,000/well) or DCs/monocytes (5,000 cells/well) incubated with P. murina antigen (20 μg/ml), purified Msg (10 μg/ml) or media alone; results are shown as the stimulation index. CD4+ T cells or B cells cultured alone and unpurified splenocytes served as controls. Results are shown as mean stimulation index of 3 replicates for each condition, and are shown for one of 2 experiments with similar results. P values are shown for the difference between the RLU of the antigen incubated wells vs. no antigen control wells, using Student’s unpaired t-test. *, p<0.05; †, p<0.01; ‡, p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we have demonstrated in a mouse model that CD19+ B cells perform a critical role in the control and clearance of Pneumocystis infection, one that is mediated by CD40-CD40L interaction. The reconstitution of wild-type CD19+ cells in the CD40 KO mouse is sufficient to substantially control P. murina infection in the lungs. Notably, BMDCs did not confer the same level of control, even after priming with Pneumocystis antigens.

Previous studies have established that disruption of the CD40-CD40L interaction results in susceptibility to PCP both in humans and mice [3, 13, 20, 31]. We found that adoptive transfer of wild-type splenic cells was sufficient to protect CD40 KO mice from progressive P. murina infection. Surprisingly, however, when we utilized specifc subsets of splenocytes to clarify their roles, the decline in organism burden was associated primarily with CD19+ cells. The CD19− splenocyte population, which would include CD40-expressing monocytes and DCs, appeared unable to control infection.

B cells have been increasingly recognized as playing an important role in controlling Pneumocystis infection through a mechanism that is independent of antibody production [18]. Antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells appears to be a major component of this mechanism, as MHC II deficient B cells are unable to reconstitute anti-Pneumocystis responses in a highly susceptible B cell deficient (μMT) mouse model [19, 32]. A Pneumocystis-specific B cell receptor appears to be required for antigen presentation, although in 1 of 2 experiments egg lysozyme specific B cells were able to substantially control infection [21]. Optimal priming of CD4+ T cells in the latter study required the presence of B cells during the first 2 to 3 days after infection. In addition to antigen presentation, TNF-α production by B cells may also contribute to CD4+ T cell activation and subsequent control of infection [22].

Given the potential importance of antigen presentation by B cells, we utilized an in vitro proliferation assay to demonstrate that B cells are able to present P. murina antigens to CD4+ T cells. This required cells from previously immunized mice, potentially because there were too few T cells recognizing Pneumocystis antigens in control mice. Notably, B cells induced proliferation when using a crude Pneumocystis antigen preparation, but not when using purified Msg, while CD11b+/CD11c+ cells were able to present both antigen preparations. The reason for these differences is uncertain, but support the concept that Msg facilitates evasion of host immune responses [27].

Anti-Pneumocystis antibodies play a role in limiting infection but by themselves appear insufficient to totally control/clear infection [11, 21, 33, 34]. In our studies, the decline in organism burden was associated with the production of anti-Pneumocystis antibodies, suggesting a role in clearance of infection; alternatively, however, this may simply reflect reconstitution of B cell function following restoration of CD40-CD40L interactions.

An important caveat for prior studies is that most utilized an intratracheal model of Pneumocystis infection that delivers a bolus of live and dead organisms as well as host lung cells/cell fragements that can impact the immune response. Dead and damaged Pneumocystis organisms will expose highly inflammatory β-glucans present in the Pneumocystis cysts, as well as other potential pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) which may skew responses. We have previously shown that β-glucans are largely masked in cysts in situ, which likely minimizes their inflammatory effects, and that β-glucans are major contributors to lung inflammation [35]. In the current study we have utilized a co-housing model which more closely mimics transmission and presumably immune reponses in humans [15].

Using this co-housing model, in prior microarray studies we identified a cell-mediated, interferon-γ related immune signature in immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice at approximately 5 weeks (peak of infection), followed by a robust B cell signature about a week later that persisted through 10 weeks [13]. Notably, immune reponses were essentially absent at the same time-points in CD40L KO mice despite progressive infection.

Our results using B cell depleted splenocytes as well as BMDCs suggest that other cell populations cannot replace B cells in providing optimal immunity, at least in CD40 KO mice. The limited contribution by CD11c+ cells to clearance of infection may have been due to ineffective trafficking of donor CD11c+ cells to recipient lungs. Further, BMDCs may not function identically to native DCs [36, 37]. However, based on the more prominent control seen at day 65 vs. day 90 when using primed BMDCs, we speculate that the contribution of these cells is primarily early in infection, resulting in a delay in progression kinetics, but ultimately in an inability to clear infection.

Intriguingly, in an intratracheal inoculation model, μMT mice that were reconstituted with chimeric bone marrow cells in which B cells did not express CD40, while other cells including DCs and macrophages, expressed CD40, were able to clear Pneumocystis infection, albeit with delayed kinetics compared to mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow cells [20]. This suggests that CD40 expression by B cells is not an absolute requirement, and alternative mechanisms to activate T cells are operational. Timing of reconstitution, trafficking effects, or CD40 expression by other cell populations that are reconstituted following bone marrow transplantation may account for the differences between the studies.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health. All authors report no conflicts of interest. We thank Rene Costello for providing animal care, and the NHLBI core flow cytometry facility for support of the cell sorting studies.

References

- 1.Kovacs JA, Masur H. Evolving health effects of Pneumocystis: one hundred years of progress in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA 2009;301:2578–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas CF Jr., Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2487–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy J, Espanol-Boren T, Thomas C, et al. Clinical spectrum of X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. J. Pediatr. 1997;131:47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maini R, Henderson KL, Sheridan EA, et al. Increasing Pneumocystis pneumonia, England, UK, 2000–2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:386–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin SI, Fishman JA. Pneumocystis pneumonia in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2013;13 Suppl 4:272–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roux A, Canet E, Valade S, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with or without AIDS, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1490–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cisse OH, Ma L, Dekker JP, et al. Genomic insights into the host specific adaptation of the Pneumocystis genus. Commun Biol 2021;4:305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesnay A, Paget C, Heuze-Vourc’h N, Baranek T and Desoubeaux G. Pneumocystis Pneumonia: Pitfalls and Hindrances to Establishing a Reliable Animal Model. J Fungi (Basel) 2022;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida Y, Matsumoto Y, Yamada M, Okabayashi K, Yoshikawa H and Nakazawa M. Pneumocystis carinii: electron microscopic investigation on the interaction of trophozoite and alveolar lining cell. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 1984;256:390–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masur H, Ognibene FP, Yarchoan R, et al. CD4 counts as predictors of opportunistic pneumonias in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 1989;111:223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roths JB, Sidman CL. Both immunity and hyperresponsiveness to Pneumocystis carinii result from transfer of CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells into severe combined immunodeficiency mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:673–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuta T, Nagata T, Kikuchi T and Kikutani H. Fatal spontaneous pneumocystosis in CD40 knockout mice. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2001;Suppl:129S–130S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez-Novoa B, Bishop L, Logun C, et al. Immune responses to Pneumocystis murina are robust in healthy mice but largely absent in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;84:420–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiley JA, Harmsen AG. CD40 ligand is required for resolution of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in mice. J. Immunol. 1995;155:3525–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestereng VH, Bishop LR, Hernandez B, Kutty G, Larsen HH and Kovacs JA. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain-reaction assay allows characterization of Pneumocystis infection in immunocompetent mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:1540–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elgueta R, Benson MJ, de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Guo Y and Noelle RJ. Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2009;229:152–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laman JD, Claassen E and Noelle RJ. Functions of CD40 and Its Ligand, gp39 (CD40L). Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2017;37:371–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolls JK. An Emerging Role of B Cell Immunity in Susceptibility to Pneumocystis Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017;56:279–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund FE, Hollifield M, Schuer K, Lines JL, Randall TD and Garvy BA. B cells are required for generation of protective effector and memory CD4 cells in response to Pneumocystis lung infection. J. Immunol. 2006;176:6147–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lund FE, Schuer K, Hollifield M, Randall TD and Garvy BA. Clearance of Pneumocystis carinii in mice is dependent on B cells but not on P carinii-specific antibody. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1423–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Opata MM, Hollifield ML, Lund FE, et al. B Lymphocytes Are Required during the Early Priming of CD4+ T Cells for Clearance of Pneumocystis Infection in Mice. J. Immunol. 2015;195:611–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opata MM, Ye Z, Hollifield M and Garvy BA. B cell production of tumor necrosis factor in response to Pneumocystis murina infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:4252–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ripamonti C, Bishop LR and Kovacs JA. Pulmonary Interleukin-17-Positive Lymphocytes Increase during Pneumocystis murina Infection but Are Not Required for Clearance of Pneumocystis. Infect. Immun. 2017;85:e00434–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldszmid RS, Idoyaga J, Bravo AI, Steinman R, Mordoh J and Wainstok R. Dendritic cells charged with apoptotic tumor cells induce long-lived protective CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immunity against B16 melanoma. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5940–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 1999;223:77–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs JA, Halpern JL, Swan JC, Moss J, Parrillo JE and Masur H. Identification of antigens and antibodies specific for Pneumocystis carinii. J. Immunol. 1988;140:2023–20231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishop LR, Helman D and Kovacs JA. Discordant antibody and cellular responses to Pneumocystis major surface glycoprotein variants in mice. BMC Immunol 2012;13:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rong HM, Li T, Zhang C, et al. IL-10-producing B cells regulate Th1/Th17-cell immune responses in Pneumocystis pneumonia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2019;316:L291–L301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundgren B, Lipschik GY and Kovacs JA. Purification and characterization of a major human Pneumocystis carinii surface antigen. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;87:163–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma L, Chen Z, Huang DW, et al. Diversity and Complexity of the Large Surface Protein Family in the Compacted Genomes of Multiple Pneumocystis Species. mBio 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Saud BK, Al-Sum Z, Alassiri H, et al. Clinical, immunological, and molecular characterization of hyper-IgM syndrome due to CD40 deficiency in eleven patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 2013;33:1325–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcotte H, Levesque D, Delanay K, et al. Pneumocystis carinii infection in transgenic B cell-deficient mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1996;173:1034–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gigliotti F, Hughes WT. Passive immunoprophylaxis with specific monoclonal antibody confers partial protection against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonitis in animal models. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;81:1666–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng M, Shellito JE, Marrero L, et al. CD4+ T cell-independent vaccination against Pneumocystis carinii in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1469–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kutty G, Davis AS, Ferreyra GA, et al. β-glucans are masked but contribute to pulmonary inflammation during Pneumocystis pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;214:782–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helft J, Bottcher J, Chakravarty P, et al. GM-CSF Mouse Bone Marrow Cultures Comprise a Heterogeneous Population of CD11c(+)MHCII(+) Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2015;42:1197–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Naik SH and Kershaw MH. Differential development of murine dendritic cells by GM-CSF versus Flt3 ligand has implications for inflammation and trafficking. J. Immunol. 2007;179:7577–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]