Abstract

The Xenopus TFIIIA gene is transcribed very efficiently in oocytes. In addition to a TATA element at −30, we show that from −425 to +7 the TFIIIA gene contains only two positive cis elements centered at −267 (element 1) and −230 (element 2). This arrangement of the cis elements in the TFIIIA gene is striking because these two elements are positioned very close to each other yet separated from the TATA element by approximately 190 nucleotides. We show that the 190-nucleotide spacing between the TATA element and the upstream cis elements (elements 1 and 2) is critical for efficient transcription of the gene in oocytes and that a nucleosome is positioned in this intervening region. This nucleosome may act positively on TFIIIA transcription in oocytes by placing transcription factors bound at elements 1 and 2 in a favorable position relative to the transcription complex at the TATA element.

The Xenopus laevis TFIIIA gene encodes a 38-kDa zinc finger protein that can both act as a positive transcription factor for 5S rRNA gene expression and bind 5S rRNA (4, 23, 32). Since high levels of RNA are stored in developing oocytes, genes such as TFIIIA are expressed at very high levels during oogenesis. TFIIIA expression changes abruptly during early Xenopus development; mRNA levels decline from 5 × 106 copies per oocyte to less than 10 copies per somatic cell in tadpoles (6, 34). Several groups have mapped cis elements in the TFIIIA promoter necessary for transcription in stage VI Xenopus oocytes (8, 15, 26, 30). The −425 to +7 region of the gene appears to be sufficient for high levels of expression in stage VI oocytes, and two positive-acting cis elements are consistently reported at −267 (element 1) and −230 (element 2). Several other elements are inconsistently observed; they include positive elements at −167 to −122, −144 to −101, and −93 to −78 and negative elements at −306 to −289 and −235 to −175 (8, 30). Most of these elements lie between element 2 and the TATA element, which is also a region thought to be important in the repression of TFIIIA expression in embryonic cells (26).

A Xenopus factor termed B1 binds to element 1 at −267 and appears to be the Xenopus homolog of USF (major late transcription factor). This activator was first characterized in the adenovirus major late promoter (7, 8, 10, 30). Counterintuitively, USF appears to be a ubiquitous factor that is involved in the control of many developmentally regulated genes (2, 3, 19, 24, 31, 42). The regulatory function of USF for these genes has not been determined. B2 is a distinct factor that binds to element 2 at −230 in the TFIIIA gene. B2 has been suggested to be the Xenopus homolog of Sp1 (23a). Sp1 is a transcriptional activator used by a large number of genes and was recently shown to be absolutely required for early development in mice (27). Both B1 (USF) and B2 (Sp1) appear to be altered during early Xenopus development, as demonstrated by electrophoretic mobility shift assays. These differences in mobility of the DNA-protein complexes are concomitant with changes in TFIIIA transcription (10, 26).

We have extended the cis-element mapping studies and show that the TFIIIA gene contains only two positive-acting elements, at −267 (element 1) and −230 (element 2), which are required for efficient transcription in stage VI oocytes. DNase footprinting analysis also has shown that the binding sites for these two proteins abut one another on the TFIIIA gene sequences (23a). In this report, we show that the spacing between these two cis elements and the TATA box can dramatically affect the efficiency of transcription from the TFIIIA promoter. This observation probably accounts for the variable results in other cis-element mapping studies of the gene. A positive role for chromatin structure on transcription was first proposed a number of years ago for the Drosophila hsp26 gene (12, 35). This has recently been shown to be true in transgenic flies (13). Schild et al. have also demonstrated that a nucleosome-dependent static loop potentiates estrogen-stimulated transcription of the vitellogenin B1 promoter (29). In the vitellogenin gene, the nucleosome position is determined by the DNA sequences themselves. However, in the TFIIIA gene, the location of the nucleosome appears to be dictated primarily by factor binding sites in the TFIIIA promoter region, more like the case for the hsp26 gene. We find that a nucleosome is positioned on TFIIIA templates between element 2 and the TATA box on templates injected into oocytes. This phased nucleosome appears to act positively on transcription by placing B1 and B2 bound to their cognate elements in a favorable position relative to the basic transcriptional machinery at the TATA box.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The construction of the TFIIIA-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) plasmids F9, F41, 76b, F64, F65, and F53 has been described previously (26). All deletions were constructed by recombining linker scanning mutations in the TFIIIA gene upstream sequences by using the restriction sites produced by the linker scanning mutation. F125 has the sequences between −188 and −103 deleted in this fashion. One copy of an 85-bp Sau3A fragment from pBR322 was inserted into the deletion site of F125 to form plasmid F127, which has wild-type spacing. Two copies of the 85-bp Sau3A fragment were inserted into F125 to produce F128. The other deletion constructs made include F141, in which the sequences between −225 and −35 are replaced by the sequence ATTGCAT for a total spacing change of 183 bp. F142 has a deletion of the sequences between −165 and −35 replaced by the sequence AGCTA for a total deletion of 125 bp. In plasmid F143, the sequences between −139 and −35 were replaced by the sequence GCTA for a total deletion of 100 bp. For F144, sequences between −199 and −34 were replaced by TTGCAT, resulting in a deletion size of 158 bp. F145 was prepared with the sequences from the TFIIIA gene from −207 to −35 replaced by TTGCAT, yielding a spacing change of −166 bp. F146 and F147 were prepared from F143 and F144, respectively, with a PCR fragment from pUC19 inserted into the deletion sites to generate wild-type spacing for F146 and a deletion of 58 bp for F147. The authenticity of all plasmid constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Oocyte injection, primer extension assay, and nuclear isolation.

Oocyte injections and primer extension assays were performed exactly as described previously (26), including the use of the plasmid F64 as an internal standard. Unless otherwise noted, 4 nl of a solution containing 0.1 mg of plasmid DNA per ml in sterile H2O was injected, followed by incubation of the oocytes at 18°C overnight (20 to 24 h). In the experiment where nonspecific (pUC19) DNA was included with constant amounts of template, the indicated concentrations of pUC19 were added to a solution containing 0.1 mg of F9 or F125 per ml. For nuclease mapping studies, nuclei were isolated from injected oocytes (F9, F65, F125, or F127) after an overnight incubation at 18°C. The nuclei were isolated in OR2 medium by tearing open the oocytes and teasing out the nucleus (germinal vesicle). The germinal vesicles were collected and stored on ice until 40 nuclei which had been injected with these plasmids were collected.

Isolation of mononucleosomes and ligation-mediated PCR (LMPCR).

The nuclei isolated as described above were suspended in a final volume of 150 μl of 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5)–50 mM NaCl–0.25 M sucrose, and 15 μl of 100 mM MgCl2–10 mM CaCl2 was added. Micrococcal nuclease digestion was initiated by the addition of micrococcal nuclease to a final concentration of 500 U/ml. This mixture was then incubated for 8 min at 25°C, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 15 μl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). For the uninjected control, 40 ng of the appropriate plasmid was added immediately after the micrococcal nuclease. Digested nuclei were then added to HeLa cell nuclei (optical density at 260 nm of 7.5) which had been previously treated with micrococcal nuclease in exactly the same fashion as the oocyte nuclei. This mixture was loaded on 5 to 25% sucrose gradients prepared in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)–35 mM NaCl–1 mM EDTA–1 mM benzamidine–0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The gradients were centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 10 h at 4°C in an SW41 rotor. The gradients were fractionated into 0.5-ml fractions, sodium dodecyl sulfate was added to 1%, and proteinase K was added to 200 μg/ml. After a 3-h incubation at 65°C, the fractions were extracted with phenol-CHCl3 and CHCl3 and then ethanol precipitated. The fractions were resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–1 mM EDTA, and one-fifth of each fraction then loaded on a 1.5% agarose gel. Fractions containing a DNA fragment of approximately 150 to 200 bp (the mononucleosome fraction) were pooled and then treated with polynucleotide kinase in the presence of 1 mM ATP. This reaction mixture was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 30 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–1 mM EDTA.

The pooled mononucleosome fractions (5 μl) were then used in LMPCR as described previously (17), using the following oligonucleotide pairs. The oligonucleotides used to determine the 5′ boundary of nucleosome binding to F9 and F65 were dCCTGTGTCCCTTGCAGCTTT (F9-5′ oligonucleotide 1) and dCCTGTGTCCCTTGCAGCTTTAGCCTT (F9-5′ oligonucleotide 2). The 3′ boundaries on F9 and F65 were determined by the use of dTTACTGAAGGCTAAAGCTGC (F9-3′ oligonucleotide 1) and dGCAAGGGACACAGGAAAGGACTGATTGCC (F9-3′ oligonucleotide 2). For mapping the position of nucleosomes on F125, the following oligonucleotides were used: dATTATCGCACATGCATCGG (F125-5′ oligonucleotide 1), dGTTTTGCGATGTCTGAAAGGATTGGC (F125-5′ oligonucleotide 2), dTCTAAGCCAATCCTTTCAGAC (F125-3′ oligonucleotide 1), and dTCAGACATCGCAAAACTTCCCGATGC (F125-3′ oligonucleotide 2). Mapping of nucleosomes on F127 was accomplished using dAAAGATAGCATTCTTAGTGG (F127-5′ oligonucleotide 1), dTTAGTGGTTTAGAAGGGATGAAACAGC (F127-5′ oligonucleotide 2), dCAGCCTGAGCTGTTTCATCCC (F127-3′ oligonucleotide 1), and dCATCCCTTCTAAACCACTAAGAATGC (F127-3′ oligonucleotide 2). The conditions used for the PCRs were denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 45 to 55°C for 2 min, and extension at 76°C for 3 min, using a total of 18 cycles of amplification. The labeling reactions involved two cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 55 to 65°C for 2 min, and extension at 76°C for 10 min. Annealing temperatures varied within the above ranges for each primer-template combination. Following the labeling reaction, the products were split into three aliquots each and ethanol precipitated. Precipitates were resuspended in sequencing loading buffer and loaded on a sequencing gel with 32P-labeled HpaII-digested pBR322 as a standard.

RESULTS

Contribution of element 1 and element 2 to TFIIIA gene expression in stage VI oocytes.

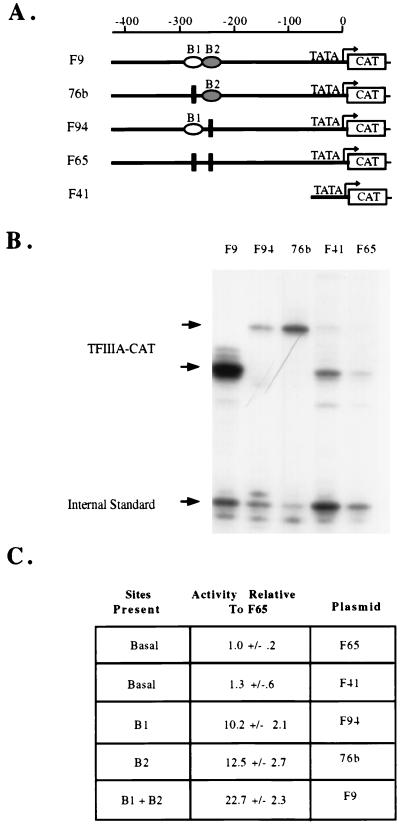

The existence of cis elements (element 1 and element 2) in the region of the TFIIIA gene from sequences from −280 to −220 is well documented (8, 10, 15, 30). Figure 1C reaffirms the activity of these elements and further demonstrates that the effect they have on TFIIIA gene regulation is additive and not cooperative or synergistic (compare F9 to F94 and 76b). DNase footprinting has demonstrated that the regions protected from digestion by B1 and B2 directly abut one another on the TFIIIA gene sequences (23a). These and other experiments have demonstrated that no other DNA binding proteins can be mapped to the region between −58 and the B2 binding site (23a). The data in Fig. 1 demonstrate that no other cis elements which affect TFIIIA gene regulation appear to be present in this region. A plasmid with mutations of elements 1 and 2 (F65) yields the same basal level of transcription as does deletion of all sequences 5′ of −58 (F41). Sequences from −223 to −58 thus have little or no effect on TFIIIA gene regulation in oocytes. This is contrary to other reports of transcriptional regulatory elements in the TFIIIA gene (10, 14). The data presented in Fig. 1 and our previous studies differ from those other reports only in the type of mutations used. Linker scanning and point mutations were used here and previously (26), in contrast to the internal deletions, which alter the spacing between the cis elements, used in other studies (10, 15). To examine the effects of deletions of the sequences between element 2 and −58, we performed the studies described below.

FIG. 1.

Activities of TFIIIA-CAT reporter constructs. (A) Schematic diagram of TFIIIA-CAT reporter constructs. F9 is a wild-type construct containing TFIIIA gene sequences from −425 to +7; 76b has the same sequences with a point mutation which disables element 1. F94 contains a linker scanning mutation which disables element 2; F65 has both the 76b and F94 mutations, while F41 contains only sequences between −58 and +7. (B) The plasmids shown in panel A were injected into oocytes and subjected to primer extension analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The upper two arrows point out the TFIIIA-CAT products, and the lower arrow marks the position of the product from the F64 internal standard. (C) Quantification of the data in panel B. The radioactivity in the bands was determined with an Instantimager (Packard), and the data were averaged over four determinations. The data were then normalized to the expression of the internal standard and presented as activity relative to basal expression (expression of a plasmid without elements 1 and 2).

Spacing between the cis elements of the TFIIIA gene is essential for high levels of expression.

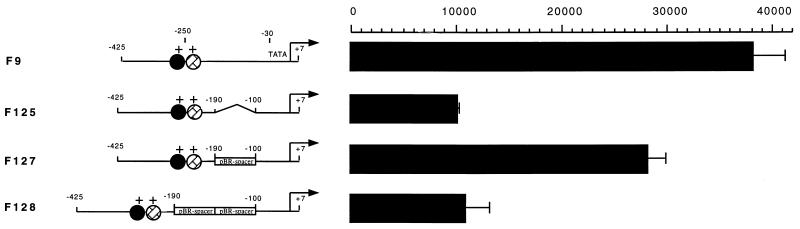

During our studies of the dependence of TFIIIA transcription on the presence of cis elements in the upstream region of the gene, it was observed that deletions of sequences between element 2 and the TATA box caused approximately a fourfold decrease in transcription. As shown in Fig. 2, the F125 construct contains a deletion of 85 bp between element 2 and the TATA box. In this case, the activity of this construct in stage VI oocytes is approximately three- to fourfold lower than in the wild-type construct, F9. When the missing 85 bp of the F125 construct are replaced by pBR322 sequences (F127), the activity of this construct returns to near the wild-type level (Fig. 2). The DNA fragment in F127 used to replace deleted sequences of F125 is unrelated to those in the TFIIIA gene upstream sequences. When these facts are considered, the data indicate that the spacing change, not the lack of those specific sequences, is responsible for the decrease in activity found with the F125 and F140 deletion constructs. F128 was also derived from F125, but 170 bp of pBR322 sequence replace the 85 bp deleted from the TFIIIA upstream region in F125. This generates a plasmid with an additional 85 bp inserted between element 2 and the TATA box. F128 has approximately three- to fourfold less activity than the wild-type plasmid, just as the deletion constructs did, indicating that an insertion in this region is as detrimental as a deletion. Therefore, it appears that the spacing between element 2 and the TATA box is essential for the full activity of the TFIIIA gene in stage VI oocytes.

FIG. 2.

Alterations in the spacing between elements 1 and 2 and the TATA box of the TFIIIA gene repress gene activity. Schematic diagrams of plasmids F9, F125, F127, and F128 are shown on the left. The exact extents and locations of the deletions and insertions are described in Materials and Methods. Activities are represented as counts per minute recovered from primer extension reactions as described previously (26).

Chromatin structure regulates TFIIIA gene transcription in stage VI oocytes.

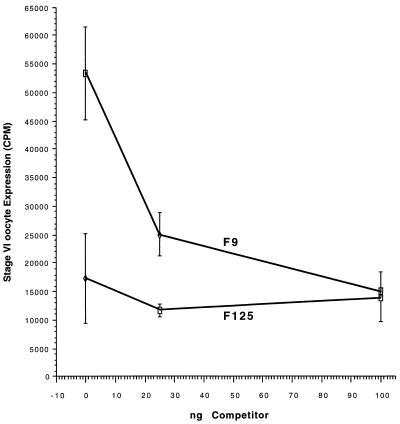

Approximately 190 bp separate the end of element 2 from the TATA box of the TFIIIA gene (26, 37). A nucleosome repeat occupies approximately this interval on a stretch of DNA (39). To examine the possibility that a phased nucleosome can activate transcription of the TFIIIA gene, we performed experiments in which a constant amount of template DNA (wild type or containing deletions between the upstream elements and the TATA box) was injected into oocytes with increasing amounts of a nonspecific competitor DNA. Similar experiments have been performed in the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter system and have been used to demonstrate that the formation of chromatin on the MMTV constructs inhibits transcription of these constructs (24). The basis of this experiment is that the nonspecific competitor will inhibit the packaging of the injected templates into chromatin by competing for histones and/or chromatin assembly factors. It is important at this point to mention that at the level of DNA injected into oocytes in the experiments described here (0.4 ng), chromatin assembly on injected templates is quite efficient (11). MMTV constructs transcribed in oocytes showed a marked increase in transcription with increasing amounts of nonspecific DNA, consistent with a negative role for chromatin in the transcription of these constructs (25). As demonstrated in Fig. 3, the wild-type TFIIIA construct (F9) demonstrated a decrease in transcription with increasing concentrations of nonspecific DNA in stage VI oocytes. This is exactly opposite the behavior of the MMTV construct in the same procedure. Such a result suggests that rather than being inhibited by the packaging of the template DNA into chromatin, the wild-type TFIIIA gene construct used here may be activated by the incorporation of the injected DNA into chromatin. The behavior of the F125 template (containing a 90-bp deletion in the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box) is also interesting (Fig. 3). There was essentially no change in activity with increasing amounts of nonspecific competitor added to a constant amount of template with a 90-bp deletion (F125). These data imply that the deletion of sequences between element 2 and the TATA box may alter the assembly of nucleosomes onto the TFIIIA gene sequences included in these constructs. Further consideration of these data suggests that a nucleosome is positioned between element 2 and the TATA box in the wild-type TFIIIA constructs. It is possible that the positioned nucleosome functions to bring the proteins bound at elements 1 and 2 (the upstream elements) into the vicinity of the basic transcriptional initiation complex at the TATA box. The proximity of these two protein complexes might lead to increased interactions between them and potentiate transcription initiation of the TFIIIA gene.

FIG. 3.

Competition with pUC19 DNA. Plasmids F9 (wild type) and F125 (deletion [Fig. 2]) (4 nl; 0.1 mg/ml) were injected into stage VI oocytes along with the indicated amount of competitor DNA. Expression is represented as counts per minute recovered from a primer extension reaction.

Mapping the position of nucleosomes on TFIIIA gene constructs in stage VI oocytes.

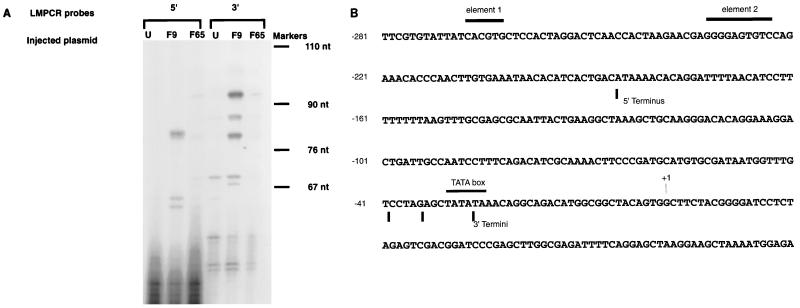

The experimental findings presented above are suggestive of a role for a nucleosome positioned between element 2 and the TATA box in the activation of the TFIIIA gene. To physically map the position of a nucleosome on the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box, various mapping techniques were tried. The large size of a stage VI oocyte, 1.5 mm in diameter, makes it impossible to obtain sufficient quantities of oocyte nuclei to map the location of nucleosomes on the endogenous gene. When attempts were made to use standard techniques on oocyte nuclei which had been injected with constructs containing wild-type TFIIIA gene sequences (F9 [Fig. 2]), the mapping experiments were plagued by high backgrounds. However, it has been demonstrated that a normal micrococcal nuclease ladder can be generated from the TFIIIA constructs injected into oocyte nuclei (data not shown). Yenidunya et al. mapped nucleosomes by first digesting nuclei with micrococcal nuclease to generate mononucleosomes (41). These mononucleosomes were then purified on gradients, and the DNA from the mononucleosome fraction was digested with restriction enzymes, run on agarose gels, and blotted with probes from the gene of interest. We combined this technique with LMPCR (17) detection of TFIIIA gene sequences. Oocyte nuclei were injected with the wild-type TFIIIA construct F9 or plasmid F65, in which both elements 1 and 2 are mutated. The oocytes from each set of injections were incubated overnight, to permit chromatin assembly, and then the nuclei were isolated and digested with micrococcal nuclease. Digested nuclei were combined with digested nuclei from HeLa cells and fractionated on 5 to 25% sucrose gradients. Fractions containing mononucleosomes were pooled and subjected to LMPCR using the primer pairs described in Materials and Methods. The LMPCR mixtures were loaded on a 6% sequencing gel, and the sizes of the products were estimated from the standards. Figure 4A shows the products of the LMPCR. As shown in Fig. 4A, strong signals were present only when a plasmid containing wild-type TFIIIA gene sequences was present (compare F9 with F65 and the uninjected control). While bands are not visible in the F65 lane of Fig. 4A, overexposure of the gel shows very weak signals at the same positions as those for F9. 5′ primers yield a major product approximately 81 nucleotides (nt) in length. Using the 3′ primer set, the major products are at 81, 86, and 93 nt. Other primer sets which were designed to detect phasing directly over the TATA box gave no products (data not shown). Limits of micrococcal nuclease protection are determined from the lengths of the LMPCR products as shown in Fig. 4A. The 5′ boundary was at −185, and the 3′ terminus was from −40 to −28. These sites map the position of the nucleosome on the upstream sequences of the TFIIIA gene. Therefore, Fig. 4B illustrates that a nucleosome is positioned between element 2 and the TATA box of the TFIIIA gene in stage VI oocytes.

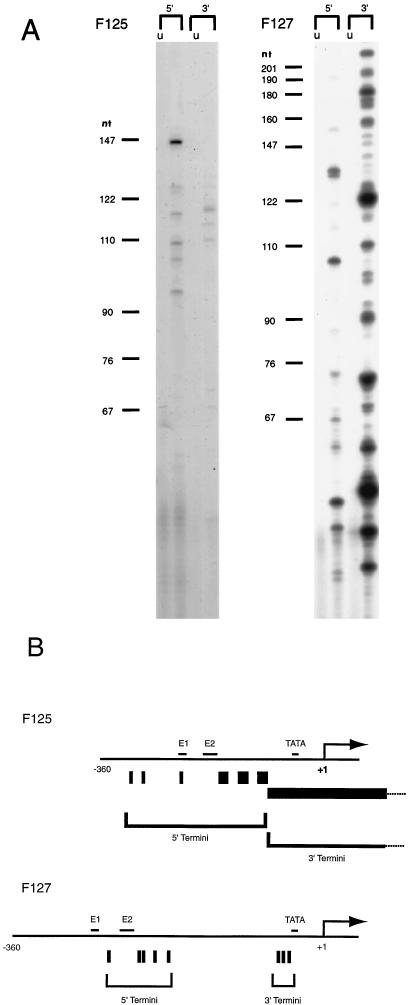

FIG. 4.

Positions of nucleosomes on the TFIIIA gene sequences between element 2 and the TATA box. (A) Oocytes were injected with either the wild-type TFIIIA-CAT reporter plasmid (F9) or plasmid F65, in which both elements 1 and 2 are mutated. Uninjected samples (U) are naked DNA controls (F9 or F65 added to uninjected nuclei after nuclease). Mononucleosomes were generated and analyzed by LMPCR as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of molecular size markers are denoted by bars. (B) LMPCR products from isolated mononucleosomal DNA are shown superimposed on the TFIIIA gene sequences. Vertical bars indicate the termini of the major products of the LMPCR. Horizontal bars mark the positions of the core sequences of element 1, element 2, and the TATA box.

The positioning of nucleosomes on templates in which the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box had been deleted (F125) or deleted and replaced with pBR322 DNA (F127) was also determined (Fig. 5). Figure 5 demonstrates that when injected into oocytes, the F127 construct, which maintains the spacing between element 2 and the TATA box, has a positioned nucleosome. The LMPCR analysis shows bands at 95, 101, 109, 116, and 146 nt with the 5′ primers and at 110, 113, and 118 nt with the 3′ primers (Fig. 5A). When these positions are projected onto the sequences of the F127 construct, it can be seen that most of these sites would indicate that a nucleosome is positioned between element 2 and the TATA box on this construct as well as on the F9 construct (compare F9 and F127 in Fig. 4 and 5). The presence of one anomalous band on the 5′ side (the 146-nt band) might indicate that in some cases the position of the nucleosome includes the element 2 sequence. However, since this band represents a position between elements 1 and 2, it could be an artifact of transcription factor binding to those sequences.

FIG. 5.

Mapping of nucleosome positions on mutated TFIIIA gene constructs. (A) Oocytes were injected with F125, which contains an 85-bp deletion between element 2 and the TATA box, or with F127, in which this 85-bp deletion has been replaced by sequences from pBR322. Uninjected samples (u) are naked DNA controls (plasmids added to uninjected nuclei after nuclease). Mononucleosomes were generated and analyzed by LMPCR as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of molecular size markers are denoted by bars. (B) Positions of LMPCR products are shown on TFIIIA gene sequences. Vertical bars represent termini of the major products; the heavy horizontal bar represents the large number of sites found on the F125 template. Nucleotide positions represent those of the wild-type TFIIIA gene construct (F9).

In contrast to the positioning of nucleosomes on plasmids F9 and F127, the TFIIIA gene construct containing a deletion of 85 bp between element 2 and the TATA box (F125) appears not to have a positioned nucleosome in this region. The LMPCR products from this template injected into oocytes show a diffuse pattern of bands covering nearly all of the sequences which could be expected from mononucleosomes found on this plasmid. While preferred registers for the nucleosomes appear to exist, they are widely spaced and positioning of the nucleosome is not apparent. A difference can be noted between the digestion patterns of two templates on which no nucleosome phasing seems to occur, F65 in Fig. 4A and F125 in Fig. 5A. When gels using mononucleosomes from F65 are severely overexposed, distinct bands in addition to those noted above can be seen in a very high background. Experiments also indicate that under the conditions used, the F125 LMPCR primer-template combination amplifies much more efficiently than F65 with its cognate primers. Therefore, the presence of distinct bands on the F125 template in Fig. 5A but not for F65 in Fig. 4A is not surprising.

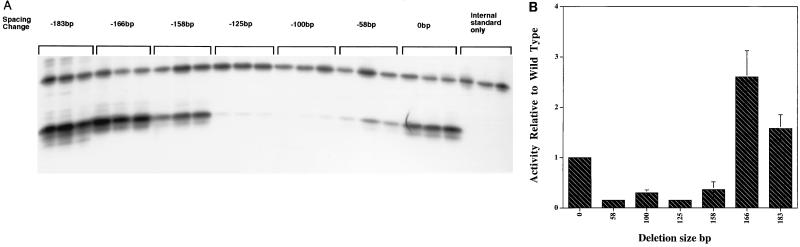

Effects of proximity between the upstream elements and the TATA box.

We wished to further examine the possibility that a positioned nucleosome might indeed activate the TFIIIA gene by bringing the complexes at the upstream elements into close proximity to the complex at the TATA sequence. It was hypothesized that if this were true, upstream elements which were brought close enough to the TATA box might activate the gene. Activation in this case would be due to the proximity of the two complexes. In Fig. 6, this idea is confirmed. One can see that constructs in which between 58 and 158 bp of the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box are deleted have activity between 4- and 10-fold lower than the wild-type level. However, when larger deletions (between 166 and 183 bp) are used, the activity of the constructs increases to 2.2- and 1.3-fold above the wild-type level. The contiguity of elements 1 and 2 and their cognate binding proteins with the TATA box and factors bound there, in the constructs with larger deletions, seems to bring about activation of the TFIIIA gene. These findings and those presented in Fig. 2 demonstrate the importance of the spatial relationship of elements 1 and 2 with the TATA box for wild-type levels of TFIIIA gene transcription in oocytes. A positive role for chromatin structure in TFIIIA transcription in these cells is also supported by these experiments.

FIG. 6.

Transcription of progressive deletions of sequences between element 2 and the TATA box. Plasmids containing these progressive deletions were injected into stage VI oocytes, and expression was measured in triplicate by primer extension analysis. Construction of the deletions are described in Materials and Methods. (A) Results from primer extension gel the upper band represents the expression of the internal standard, F64 (26), and the lower bands represent the activities of the deletions. (B) The data from panel A were quantified and are represented in graphic form. Activities presented are relative to the internal standard F64.

DISCUSSION

Xenopus oogenesis occurs over a 6-month period, during which TFIIIA expression is very high. Xenopus oocytes are arrested in meiotic prophase I and do not reenter the cell cycle until hormone-induced maturation occurs. In the absence of DNA replication, the TFIIIA gene is transcribed at a very high level over a relatively long period. Mechanisms must exist to maintain the activated state of the gene during this time. We have examined the effects of alterations in spacing between the upstream elements of the TFIIIA gene and the TATA element in stage VI oocytes of the species X. laevis. Data presented here indicate that a change in the spacing between element 2 and the TATA sequences dramatically alters transcription from the TFIIIA promoter. The basis of the dependence of TFIIIA gene activation on element spacing appears to be the presence of a positioned nucleosome on the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box.

Moderate deletions or insertions of the sequences separating element 2 and the TATA box of the TFIIIA gene dramatically decrease the transcription of this gene in oocytes. Convincing arguments for the alteration in spacing being the cause of inhibition of expression of the gene, and not the elimination of positive elements within the deleted region, are found in Fig. 2. Replacing the deleted sequences of the F125 construct with unrelated sequences to give the F127 construct restores most of the activity of the wild-type TFIIIA constructs (Fig. 2). In contrast to the inhibition of transcription seen with deletions and insertions of 90 to 180 bp seen in Fig. 2, larger deletions of 166 and 183 bp in Fig. 5 actually show stimulation of transcription over wild-type spacing. The proximity of elements 1 and 2 to the TATA box in these constructs with larger deletions probably accounts for this increase in transcriptional activity. These data suggest that interactions occur between the upstream elements (elements 1 and 2), via their bound activators (B1 and B2), and the basic transcription complex at the TATA box. Also implied is the existence of a similar mechanism, most likely a positioned nucleosome, for bringing these complexes together in the wild-type plasmid. Figure 3 presents further evidence which suggests that a phased nucleosome plays a role in the activation of TFIIIA gene transcription in stage VI oocytes. In this experiment, a nonspecific competitor was used to compete with the injected template for factors involved in chromatin assembly on these injected DNAs. Similar examinations of the MMTV promoter demonstrated that when chromatin assembly on these templates was repressed by the injection of large amounts of nonspecific DNA, the resulting templates were more transcriptionally active (25). Our investigations have exactly the opposite results. In the case of the TFIIIA gene, chromatin assembly on the injected DNA caused a stimulation of transcription and competition for factors involved in assembly inhibited TFIIIA gene transcription. However, when a template containing a deletion in the intervening sequences between element 2 and the TATA box was tested, no change in expression was seen with elevated concentrations of plasmid competitor. These observations point to activation of the TFIIIA gene by a chromatin template instead of the repression seen in the MMTV system.

Further evidence for the involvement of a positioned nucleosome comes from the experiment presented in Fig. 6, in which moderate deletions of the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box repress transcription. However, deletions which eliminate almost this entire region stimulate transcription. These larger deletions may serve the same purpose hypothesized for the positioned nucleosome, to bring element 1 and element 2 and the factors bound to them into juxtaposition with the transcriptional machinery at the TATA box. This may also be the case for a phased nucleosome in the Drosophila hsp26 gene. While the effects of smaller alterations in spacing have not been tested on the hsp26 gene, elimination of the entire sequence occupied by the positioned nucleosome has no effect on the transcription of this gene (13). These data suggest that the elimination of the sequences normally bound to a nucleosome in the hsp26 gene serves the same purpose as the positioned nucleosome in the TFIIIA gene.

With all of the functional data for the involvement of a phased nucleosome in the activation of TFIIIA gene transcription, it was necessary to demonstrate the positioning of a nucleosome on the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box. Mapping was done by a combination of two methods. First, after nuclear injection of template and overnight incubation, mononucleosomes were isolated from the nuclei as described previously (41). Elimination of background by this procedure resulted from the removal of any templates which were not assembled into chromatin. Next, to allow detection of small amounts of template, LMPCR was performed on DNA isolated from these mononucleosomes (17). The abolition of background and increased sensitivity of this combined procedure resulted in the determination of a binding site for a positioned nucleosome on TFIIIA gene sequences between element 2 and the TATA box only on templates where the spacing between these sites is maintained (Fig. 4 and 5). DNA exit and entry points on nucleosomes in H1 containing chromatin has been suggested to be in close proximity (39). Therefore, placement of a nucleosome between the upstream elements (elements 1 and 2) and the TATA sequences of the TFIIIA gene might well be expected to bring DNA-protein complexes in these regions into close enough proximity to stimulate transcription.

A similar type of static loop involving a single nucleosome has been demonstrated to potentiate transcription of the Xenopus vitellogenin B1 promoter in vitro (29). The hsp26 promoter has also been found to be activated in a similar fashion (12, 13, 35). Stimulation of TFIIIA gene transcription by a positioned nucleosome, while very similar to these other examples, is somewhat different. In both the vitellogenin B1 and hsp26 systems, the static loop brings together two different regions where trans activators bind. However, in the TFIIIA promoter, the positioning of a nucleosome brings activators into proximity with the basic transcription complex at the TATA box. Thus, this example points out that a nucleosome-dependent static loop can activate transcription at two different steps in transcriptional activation.

Mechanisms by which nucleosomes are positioned may also be of interest here. The binding site of the nucleosome which forms the static loop in the vitellogenin B1 promoter is determined by the DNA sequence. In the TFIIIA gene, the cause of nucleosome positioning has not yet been determined, but templates assembled in vitro appear not to have phased nucleosomes (26a). Additionally, comparisons of chromatin assembly on the wild-type TFIIIA gene sequences, F9, to assembly of nucleosomes on a plasmid in which elements 1 and 2 are mutated are illustrative. In this experiment the positioning of a nucleosome is much less efficient on TFIIIA gene sequences when elements 1 and 2 are not active or capable of binding B1 or B2 with high affinity, indicating that the position of the nucleosome is most likely determined by the position of elements 1 and 2 relative to the TATA box. Other specific DNA binding proteins have been demonstrated to be able to direct the positioning of nucleosomes (1, 5, 20, 21, 28, 33, 36, 38). In one case the occupancy of sites for DNA binding proteins was demonstrated to be necessary to maintain nucleosome positioning (22). Thus, there is a possibility that the positioning of a nucleosome on the TFIIIA gene regulatory region is directed by the presence of other DNA-protein complexes. Several lines of evidence suggest this possibility. First, the distance between the end of element 2 and the TATA element of the TFIIIA gene is approximately 190 bp, approximately the length of one nucleosome repeat. Additionally, the B1 protein is the Xenopus homolog of USF. In several cases USF binding sites have been associated with nucleosome-free regions of DNA (25, 40). The B2 protein has been suggested to be Sp1, which has been implicated in the formation of an active chromatin structure in the globin promoter (27). The positioning of a nucleosome on the Drosophila hsp26 gene may represent another, similar example (see above). Collectively, these investigations intimate a role for activator binding sites and the basic transcription complex in forming a location for a nucleosome to bind and activate the TFIIIA gene. However, replacement of the sequences between element 2 and the TATA box with a fragment of pBR322 does not restore all of the wild-type TFIIIA gene activity (compare F9 and F127 in Fig. 2). Additionally, the nucleosome position on the F127 construct appears to be less closely defined than that on the wild-type construct, F9 (compare Fig. 4B and 5B). These observations suggest that sequences in the TFIIIA gene between element 2 and the TATA box may augment nucleosome positioning on this region as well.

Several studies on TFIIIA gene regulation in stage VI (mature) oocytes have appeared over the years. The first of these described one positive cis-acting region between −283 and −238 with respect to the TFIIIA mRNA start site and possibly another between −167 and −122 (15). Another investigation of TFIIIA gene transcription described several positive and negative cis elements in the upstream region of the TFIIIA gene (30). The positive cis elements localized in this study were found centered at −270, −230, −130, in addition to a CAAT box at −80 and a TATA box at −35. Scotto et al. (30) also found two negative elements in oocytes, one centered at −300 and another at −175. The activities of the positive elements at −270, −230 (which represent elements 1 and 2, respectively), and the TATA box, all of which function in stage VI oocytes, have been confirmed (26). However, the existence in stage VI oocytes of any other positive or negative elements operative on the TFIIIA gene has not been confirmed. In fact, the data from Fig. 1 and 2 imply that no other positive or negative elements exist between element 2 at −230 and −58 in the TFIIIA gene. The reason for this discrepancy is almost certainly that the internal deletions used by Scotto et al. (30) and Matsumoto and Korn (15) altered the spacing between the elements 1 and 2 and the TATA box. Figures 2 and 4 both demonstrate that these internal deletions would have a large effect on transcription by disrupting the positioning of a nucleosome on these sequences. While this repression of transcription is real, it does not result from the elimination of cis elements involved in the expression of the TFIIIA gene.

It is interesting to speculate on what role chromatin structure might play in the repression of the TFIIIA gene in somatic cells. We have previously found that a CAAT element centered at −92 of the TFIIIA gene is active in embryos but not in oocytes (26). This site is occupied by the positioned nucleosome in oocytes, where the element has no activity (Fig. 4B). Element 2 (−234 to −224) is only 130 bp from the CAAT box. With a nucleosome core particle occupying 146 bp, it is possible that if the CAAT element is bound by a CAAT binding protein in somatic cells, the positioning of a nucleosome between this site and element 2 is not possible. This may indicate a difference in the positioning of the nucleosome in oocytes and somatic cells. Investigations are currently under way to test this possibility.

We have demonstrated the role of a positioned nucleosome in the activation of TFIIIA gene transcription in oocytes. The activation of TFIIIA mRNA transcription by this nucleosome is similar but not identical to the potentiation of vitellogenin B1 and hsp26 promoter activity by a nucleosome-dependent static loop (13, 29). As mentioned above, the TFIIIA gene is expressed at high levels during oogenesis for a relatively long time. Therefore, it is of interest to determine whether similar structures play a role in the regulation of other genes which are actively transcribed during oogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alan Wolffe, Harry Jarrett, Roland Stein, and Tony Weil for reviewing the manuscript and for their many helpful suggestions during the course of this study.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM 39234 to W.L.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong J A, Emerson B M. NF-E2 disrupts chromatin structure at human β-globin locus control region hypersensitive site 2 in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5634–5644. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carthew R W, Chodosh L A, Sharp P A. The major late transcription factor binds to and activates the mouse metallothionein I promoter. Genes Dev. 1987;1:973–980. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.9.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chodosh L A, Carthew R W, Morgan J W, Crabtree G R, Sharp P A. An adenovirus major late transcription factor activates the γ-fibrinogen promoter. Science. 1987;238:684–688. doi: 10.1126/science.3672119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelke D R, Ng S Y, Shastry B S, Roeder R G. Specific interaction of a purified transcription factor with an internal control region of 5S RNA genes. Cell. 1980;19:717–728. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(80)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedor M J, Lue L F, Kornberg R D. Statistical positioning of nucleosomes by specific protein binding to an upstream activating sequence in yeast. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:109–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginsberg A M, King B O, Roeder R G. Xenopus 5S gene transcription factor, TFIIIA: characterization of a cDNA clone and measurement of RNA levels throughout development. Cell. 1984;39:479–489. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregor P D, Sawadogo M, Roeder R G. The adenovirus major late transcription factor USF is a member of the helix-loop-helix group of regulatory proteins and binds to DNA as a dimer. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1730–1740. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall R K, Taylor W L. Transcription factor IIIA gene expression in Xenopus oocytes utilizes a transcription factor similar to the major late transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5003–5011. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honda B M, Roeder R G. Association of a 5S gene transcription factor with 5S RNA and altered levels of the factor during cell differentiation. Cell. 1980;22:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaulen H, Pognonec P, Gregor P D, Roeder R G. The Xenopus B1 factor is closely related to the mammalian activator USF and is implicated in the developmental regulation of TFIIIA gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:412–424. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landsberger N, Wolffe A P. Role of chromatin and Xenopus laevis heat shock transcription factor in the regulation of transcription from the X. laevis hsp70 promoter in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6013–6024. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Q, Wallrath L L, Elgin S C R. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation. J Cell Biochem. 1994;55:83–92. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240550110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Q, Wallrath L L, Elgin S C R. The role of a positioned nucleosome at the Drosophila hsp26 promoter. EMBO J. 1995;14:4738–4746. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin M, Karis A, Visser P, Grosveld F, Philipsen S. Transcription factor Sp1 is essential for early embryonic development but dispensable for cell growth and differentiation. Cell. 1997;89:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto Y, Korn L J. Upstream sequences required for transcription of the TFIIIA gene in Xenopus oocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:3801–3813. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.9.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxam A, Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPherson C E, Shim E, Friedman D S, Zaret K S. An active tissue-specific enhancer and bound transcription factors existing in a precisely positioned nucleosomal array. Cell. 1993;75:387–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80079-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller J, McLachlan A D, Klug A. Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor TFIIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1985;4:1609–1614. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller P R, Salser S J, Wold B. Constitutive and metal-inducible protein:DNA interactions at the mouse metallothionein I promoter examined by in vivo and in vitro footprinting. Genes Dev. 1988;2:412–427. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pazin M, Kamakaka R T, Kadonaga J T. ATP-dependent nucleosome reconfiguration and transcriptional activation from preassembled chromatin templates. Science. 1994;266:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.7801129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazin M J, Sheridan P L, Cannon K, Cao Z, Keck J G, Kadonaga J T, Jones K A. NF-κB-mediated chromatin reconfiguration and transcriptional activation of the HIV-1 enhancer in vitro. Genes Dev. 1996;10:37–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazin M J, Bhargava P, Geiduschek E P, Kadonaga J T. Nucleosome mobility and the maintenance of nucleosome positioning. Science. 1997;276:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelham H R B, Brown D D. A specific transcription factor that can bind either the 5S RNA gene or 5S RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4170–4174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Penberthy, W. T., D. Griffin, R. K. Hall, and W. L. Taylor. Unpublished data.

- 24.Peritz L N, Fodor E J, Silversides D W, Cattini P A, Baxter J D, Eberhardt N L. The human growth hormone gene contains both positive and negative control elements. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5005–5007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlman T, Wrange O. Inhibition of chromatin assembly in Xenopus oocytes correlates with the derepression of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5259–5265. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaff S L, Hall R K, Hart G C, Taylor W L. Regulation of the Xenopus laevis transcription factor IIIA gene during oogenesis and early embryogenesis: negative elements repress the O-TFIIIA promoter in embryonic cells. Dev Biol. 1991;145:241–254. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90123-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Pfaff, S. L., and W. L. Taylor. Unpublished data.

- 27.Pondel M D, Murphy S, Pearson L, Craddock C, Proudfoot N J. Sp1 functions in a chromatin dependent manner to augment human α-globin promoter activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7237–7241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth S Y, Shimizu M, Johnson L, Grunstein M, Simpson R T. Stable nucleosome positioning and complete repression by the yeast α2 repressor are disrupted by amino-terminal mutations in histone H4. Genes Dev. 1992;6:411–425. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schild C, Claret F, Wahli W, Wolffe A P. A nucleosome-dependent static loop potentiates estrogen-regulated transcription from the Xenopus vitellogenin B1 promoter in vitro. EMBO J. 1993;12:423–433. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scotto K W, Kaulen H, Roeder R G. Positive and negative regulation of the gene for transcription factor IIIA in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Genes Dev. 1989;3:651–662. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seal S N, Davis D L, Burch J B E. Mutational studies reveal a complex set of positive and negative control elements within the chicken vitellogenin II promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2704–2717. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segall J, Matsui T, Roeder R G. Multiple factors are required for the accurate transcription of purified genes by RNA polymerase III. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11986–11991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu M, Roth S Y, Szent-Gyorgi C, Simpson R T. Nucleosomes are positioned with base pair precision adjacent to the α2 operator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1991;10:3033–3041. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor W, Jackson I J, Siegel N, Kumar A, Brown D D. The developmental expression of the gene for TFIIIA in Xenopus laevis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6185–6195. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.15.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas G H, Elgin S C R. Protein/DNA architecture of the DNase I hypersensitive region of the Drosophila hsp26 promoter. EMBO J. 1988;7:2191–2201. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukiyama T, Becker P B, Wu C. ATP-dependent nucleosome disruption at a heat shock promoter mediated by binding of GAGA transcription factor. Nature. 1994;367:525–532. doi: 10.1038/367525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tso J Y, Van Den Berg D J, Korn L J. Structure of the gene for Xenopus transcription factor IIIA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:2187–2200. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.5.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wall G, Varga-Weisz P D, Sandaltzopoulos R L, Becker P B. Chromatin remodeling by GAGA factor and heat shock factor at the hypersensitive Drosophila hsp26 promoter in vitro. EMBO J. 1995;14:1727–1736. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolffe A P. Chromatin structure and function. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Workman J L, Roeder R G, Kingston R E. An upstream transcription factor, USF (MLTF), facilitates the formation of preinitiation complexes during in vitro chromatin assembly. EMBO J. 1990;9:1299–1308. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yenidunya A, Davey C, Clark D, Felsenfeld G, Allan J. Nucleosome positioning on chicken and human globin gene promoters in vitro. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:401–414. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zwartkruis F, Hoeijmakers T, Deschamps J, Meijlink F. Characterization of the murine Hox-2.3 promoter: involvement of the transcription factor USF (MLTF) Mech Dev. 1991;33:179–190. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]