Abstract

Background

Burnout is common among medical trainees. Whether brief periods of training on the internal medicine ward leads to resident burnout is unknown.

Methods

A survey-based study was conducted at a single academic institution. Medical residents undertaking four-week rotations on the internal medicine ward were included. Burnout was measured at the beginning and end of each rotation using the Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey. Burnout was defined as either an emotional exhaustion score of ≥ 27 or a depersonalization score of ≥ 10. Self-reported workplace conditions, behaviors and attitudes were recorded.

Results

The survey response rate was 71% and included 148 participants. The overall prevalence of burnout was 17% higher at the end of the rotation compared to the beginning of the rotation (71% vs. 54%; P < 0.001). Forty-three percent of residents without pre-rotation burnout developed post-rotation burnout. Residents with post-rotation burnout were more likely to report at least one suboptimal behavior or attitude related to patient care or professionalism (84% vs. 35%; P < 0.001). Respondents with new onset burnout were less likely to report being appreciated for their work, having their role as a learner emphasized, and receiving satisfactory support from allied healthcare professionals. New onset burnout was inversely associated with completing a second consecutive internal medicine ward rotation (adjusted OR 0.19; 95% CI, 0.04–0.90; P = 0.04).

Conclusion

Seven in ten residents are in a state of burnout after completing internal medicine ward rotations. Interventions to mitigate burnout development during periods of high intensity clinical training are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Burnout is defined as a work-related syndrome involving emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment.1 Burnout affects approximately one-half of medical residents and has been associated with medical errors, 2, 3 malpractice, unprofessional behavior, substance abuse and depression in healthcare professionals.4–7

The internal medicine ward represents a high intensity clinical training environment that poses numerous challenges for medical residents, including high acuity patient care, long work hours, and a perceived lack of support.8 Such factors may contribute to an increase in burnout among residents participating on these rotations, and interventions tailored to this setting could promote resilience. On the other hand, it is possible that the duration of these rotations is too short to impact burnout development.

To explore this issue, we undertook a survey-based study to assess the incidence and prevalence of resident burnout on the internal medicine ward. We also determined whether resident burnout was associated with self-reported performance measures and workplace-related factors. Finally, we assessed for possible risk factors associated with the development of new onset burnout.

METHODS

Participants

Residents assigned to clinical rotations on the internal medicine ward at three tertiary care hospitals affiliated with McMaster University (Hamilton, Canada) were invited to participate in the study. Participants were recruited between April and September 2018. Residents in postgraduate years 1 to 3 were eligible to participate. Rotations were four weeks in length with an average overnight on-call frequency of one every four to five days. Participation was voluntary and results were anonymized following the completion of data collection. The study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

Data Collection

The study was conducted over the course of six consecutive blocks of rotations. We electronically surveyed residents at the beginning and end of each rotation. A unique identification number was assigned to each participating resident to match pre- and post-rotation surveys. We sent participants an e-mail containing a link to an electronic survey form, three days prior to the rotation start and end date. We provided non-responders two e-mail reminders and allowed for a maximum of seven days to complete the survey. Baseline demographics were collected on pre-rotation surveys. A validated tool was used to measure burnout on the pre- and post-rotation surveys. Items pertaining to self-reported attitudes, behaviors, and workplace conditions were recorded on the post-rotation surveys.

Survey Instruments

Burnout

The Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS, hereby “MBI”) was used to measure burnout. The MBI is a 22-item questionnaire which was developed and validated for the measurement of burnout in healthcare professionals.1 The MBI is considered the gold standard for measuring burnout for healthcare professionals9 and has been extensively used to study resident burnout.10–12 The MBI consists of three categories including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. We defined burnout as either an emotional exhaustion score of ≥ 27 or a depersonalization score of ≥ 10, consistent with existing convention. 11, 13–15

Self-Reported Performance Outcomes

To determine whether burnout was associated with self-reported suboptimal patient care and professional behaviors, we provided statement selections reflecting those previously used in the literature.11 The frequency of suboptimal behaviors and attitudes were quantified on a 5-point scale (i.e., never, once monthly, once weekly, several times per week, daily). We designated each of these outcomes to be “suboptimal” if reported to occur at least once per week.16–18

Self-Reported Workplace Conditions

To determine whether new onset burnout was associated with workplace conditions, we constructed statements related to aspects of the learner’s role on the clinical team and the team’s perceived supportiveness based on a review of the existing literature.3, 19, 20 Responses to these statements were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”.

Statistical Analysis

We performed paired comparisons to assess the prevalence of burnout for participants that reported both pre- and post-rotation MBI scores using the McNemar test and compared changes in their MBI scores using paired t-tests. We conducted sensitivity analyses which included only the first participating rotation for each resident.

We assessed for associations between post-rotation burnout and suboptimal self-reported behaviors and attitudes using Chi-squared tests. In the subset of respondents without pre-rotation burnout, we compared the proportion of respondents answering “Agree” or “Strongly Agree” to statements regarding workplace conditions between those with and without post-rotation burnout using Chi-squared tests. We used Fischer’s exact tests instead of Chi-squared tests if any cell count was less than 5.

We undertook hierarchical forward stepwise logistic regression to identify possible risk factors for the development of new onset burnout. Entry and exit p-values of 0.05 and 0.10 were used, respectively. We excluded respondents with pre-rotation burnout and those without both pre- and post-rotation MBI scores from the analysis. Pre-rotation emotional exhaustion and depersonalization scores were forced into the model. Candidate variables included age greater or less than 28 years, White versus non-White race, male versus female gender, single versus partnered relationship status, first versus other postgraduate training year, internal medicine versus other training program, Canadian versus international medical graduate, prior versus no prior medical training in the same city, preceding versus no preceding rotation on the internal medicine ward, and personal debt of greater or less than $100,000 CAD. To assess the robustness of our findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using hierarchical backward stepwise regression using the same entry and exit criteria. We additionally performed a sensitivity analysis using a model which included whether the preceding rotation was in an acute care setting (i.e., internal medicine ward, intensive care unit, surgery, internal medicine night float, emergency medicine), as opposed to the internal medicine ward alone.

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA/SE 16.0 (StataCorp LLC). A two-sided p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

Survey Response

The overall survey response rate was 71% (326/458). Pre-rotation and post-rotation surveys were completed in 78% (179/229) and 75% (172/229) of cases, respectively. Paired pre- and post-rotation survey MBI scores were available in 68% of cases (156/229).

Demographics

A total of 148 unique respondents participated in the study, of whom 11 did not complete the pre-rotation survey and demographic information was therefore unavailable. Of the remaining 137 participants, about half were female and half self-identified as White (Table 1). Most participants were Canadian medical graduates, in their first postgraduate training year, between ages 25 and 28, and in an internal medicine training program. Two-thirds were in a relationship or married and very few had dependent children.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| < 24 | 10 (7) |

| 25–28 | 94 (69) |

| 29–32 | 22 (16) |

| > 33 | 11 (8) |

| Race | |

| White | 65 (47) |

| Chinese | 16 (12) |

| Arab | 15 (11) |

| South Asian | 13 (10) |

| Southeast Asian | 8 (6) |

| Other | 6 (4) |

| Not Disclosed | 14 (10) |

| Male Gender | 63 (46) |

| Dependent Children | 8 (6) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married | 31 (23) |

| Partner | 59 (43) |

| Single | 47 (34) |

| Training Level† | |

| PGY1 | 104 (76) |

| PGY2 | 31 (22) |

| PGY3 | 8 (6) |

| Home Program | |

| Internal Medicine | 81 (59) |

| Family Medicine | 18 (13) |

| Psychiatry | 14 (10) |

| Surgical | 5 (4) |

| Other | 19 (14) |

| Undergraduate Medical Training | |

| Canadian Graduate | 109 (79) |

| International Graduate | 28(21) |

| Previous Medical Training in Same City | 89 (65) |

| Internal Medicine Ward on Last Rotation‡ | 58 (32) |

| Debt (CAD) | |

| None | 24 (18) |

| 0 – 50 000 | 23 (17) |

| 50 000 – 100 000 | 19 (14) |

| 100 000 – 150 000 | 25 (18) |

| 150 000 – 200 000 | 23 (17) |

| > 200 000 | 23 (17) |

* PGY: postgraduate year

† Total exceeds 100% as some participants completed more than one rotation and in different levels of training

‡ Total represents the number of rotations evaluated. Some participants completed more than one rotation

Burnout Prevalence and Scores

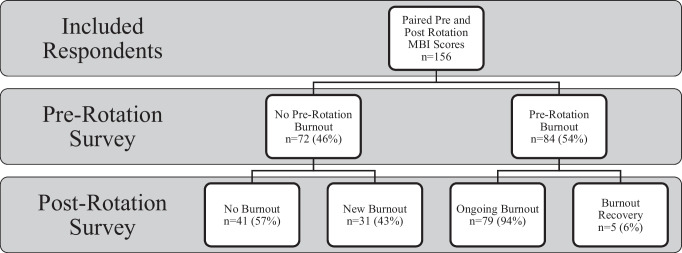

The overall prevalence of burnout was 17% higher on the post-rotation surveys compared to the pre-rotation surveys (54% vs. 71%, p < 0.001). An increase in emotional exhaustion (24.5 vs. 28.8; P < 0.001) and depersonalization (9.7 vs. 12.0; P < 0.001) scores was observed at the end of the rotation, but there was no difference in personal achievement scores (36.7 vs. 36.4; P = 0.17). The sensitivity analyses demonstrated similar findings. Of the respondents without pre-rotation burnout, 43% (31/72) developed new onset burnout by the end of the rotation. Of the respondents with pre-rotation burnout, 6% (5/84) recovered from burnout by the end of the rotation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Change in burnout status between pre- and post-rotation surveys, in respondents with paired pre- and post-rotation Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) scores.

Behaviors and Attitudes

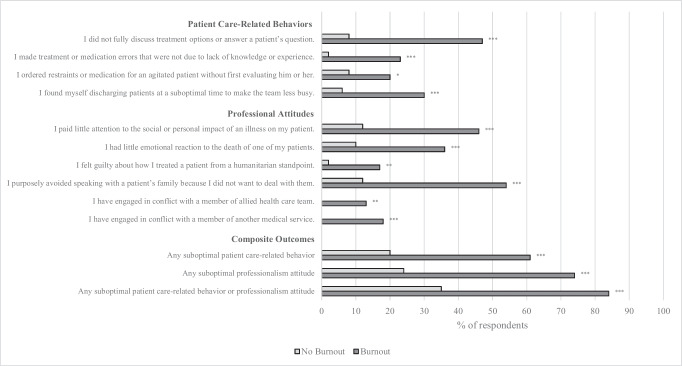

The frequency of suboptimal patient-care related behaviors and professional attitudes are shown in Figure 2. The proportion of respondents reporting at least one suboptimal patient-care related behavior or professional attitude was 49% higher in those with versus without post-rotation burnout (84% vs. 35%; P < 0.001). Both the proportion of respondents reporting at least one suboptimal patient-care related behavior (61% vs. 20%; P < 0.001) and professional attitude (74% vs. 24%; P < 0.001) were higher in those with post-rotation burnout. The most frequently reported suboptimal behaviors and attitudes in those with burnout were the purposeful avoidance of speaking with a patient’s family (54%), not fully discussing treatment options or answering a patient’s question (47%), and paying little attention to the social or personal impact of illness to a patient (46%).

Figure 2.

Frequency of suboptimal self-reported patient care-related behaviors and professional attitudes, in respondents with versus without post-rotation burnout (N = 172); p ≤ 0.05*, p ≤ 0.01**, p ≤ 0.001***.

Workplace Conditions

Associations between workplace conditions and new onset burnout are shown in Table 2. Compared to respondents that developed new onset burnout, those who did not develop burnout were more likely to report that their work and accomplishments were appreciated by the team (98% vs. 70%; P = 0.002), that their role as a learner was emphasized during the rotation (90% vs. 47%; P < 0.001), and that they were well supported by allied healthcare professionals (65% vs. 37%; P = 0.02). Respondents that did not develop burnout were less likely to report spending a significant amount of time doing academically unproductive (‘scut’) work (18% vs. 57%; P = 0.001). There were no differences in the perceived supportiveness of the attending physician or other medical residents.

Table 2.

Associations of Workplace Factors with the Development of New Onset Burnout by end of Rotation (N = 70)

| No Post-Rotation Burnout, Agree or Strongly Agree n (%) | Post-Rotation Burnout, Agree or Strongly Agree n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learner Responsibilities | |||

| My daily work and accomplishments were appreciated within my team | 39 (98) | 21 (70) | 0.002 |

| My role as a learner was emphasized during my rotation | 36 (90) | 14 (47) | < 0.001 |

| I spent a significant amount of time doing academically unproductive (“scut”) work | 7 (18) | 17 (57) | 0.001 |

| I felt I had appropriate autonomy in patient care for my training level | 38 (95) | 27 (90) | NS |

| I had ample time during the day for self-care (e.g., eat lunch, go to bathroom) | 13 (33) | 9 (30) | NS |

| Team Supportiveness | |||

| I felt well supported (comfortable discussing my frustrations, seeking help when overwhelmed, seeking assistance when faced with challenging situation) by: | |||

| My junior residents | 36 (90) | 26 (87) | NS |

| My senior residents | 353 (88) | 42 (84) | NS |

| My attending physician | 31 (78) | 19 (64) | NS |

| My allied health care team (i.e., nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, social work) | 26 (65) | 11 (37) | 0.02 |

Risk Factors for New Onset Burnout

Seventy respondents were included in the multivariable regression model. New onset burnout was inversely associated with participating in a second consecutive rotation on the internal medicine ward (odds ratio [OR] 0.19; 95%CI, 0.04–0.90; P = 0.04). New onset burnout was also associated with higher pre-rotation depersonalization scores (OR 1.24 per point; 95%CI, 1.01–1.53; P = 0.05). No association was demonstrated between new onset burnout and pre-rotation emotional exhaustion scores (OR 1.08 per point; 95%CI, 0.98–1.20; P = NS). Our sensitivity analysis did not demonstrate an association between having a preceding rotation in an acute care setting and new onset burnout.

DISCUSSION

In this single centre survey study, we found that seven in ten residents had burnout at the end of their internal medicine ward rotations. We also found that 43% of residents without pre-existing burnout developed new onset burnout over the course of their rotations. Burnout was associated with adverse behaviors and attitudes related to patient care and professionalism. Our findings suggest that even brief periods of high-intensity training on the internal medicine ward can promote burnout development and adversely affect trainee performance.

Although the prevalence of resident burnout has been previously well documented,21 little is known about the effect of specific training rotations on burnout development. Several small studies have suggested that short periods of exposure to high intensity training environments contribute to new onset burnout. For example, a study of 60 pediatric residents found that the proportion of learners meeting criteria for burnout increased over the course of intensive care rotations.22 Another study of 27 orthopedic residents found that those participating in trauma rotations had higher levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion when compared to other training environments.23 These data are consistent with our findings, which demonstrated that a significant proportion of residents experienced new onset burnout over the course of their internal medicine ward rotations. It is possible that the high levels of burnout observed on high-intensity rotations are driven by moral distress, which has been considered by some to be an important cause of burnout.24 Moral distress can be defined broadly as “when one has made a moral judgement but is unable to act upon it”.25 While we did not measure moral distress as part of our study, one study of 88 internal medicine residents found that moral distress was higher for those participating in internal medicine ward and intensive care rotations.8 Excessive workload related to call frequency and duty hours may also be an important driver of burnout on high-intensity rotations. In support of this notion, a pre-post study of duty hour restrictions for internal medicine residents demonstrated a trend towards less residents having high depersonalization after the intervention (61% vs. 55%; P = 0.13).26 Finally, a lack of flexible scheduling on some high-intensity rotations could promote burnout by failing to accommodate personal needs such as home responsibilities, sleep hygiene, and maintenance of social connections.27

Supportive learning environments may promote resilience against burnout. In a study of 1,231 residents, a strong inverse association was observed between burnout and the quality of the learning environment.28 Consistent with these findings, we demonstrated that residents with new onset burnout were less likely to feel that their role as a learner was sufficiently emphasized and that they performed an excess amount of academically unproductive ‘scut’ work. Examples of scut duties can include performing less urgent procedures, obtaining consent, filling out test requisitions, and completing less urgent hospital admissions.29 Our findings are similar to those reported in a survey of Japanese medical residents, in which excessive paperwork was independently associated with burnout (OR 2.24; 95%CI, 1.32–3.80).30 Although these tasks often seem mundane, mastery of these processes is arguably needed in order to provide comprehensive care and to gain a full understanding of health systems.31 Directly addressing the value of scutwork during teaching activities could improve residents’ perceptions of their role as a learner. On the other hand, trainees frequently perceive clinical paperwork to be excessive and a barrier to providing patient care.32 Implementation of organization-led strategies to reduce such burdens could improve workload management, which may in turn prevent burnout.

Despite physician burnout being widespread, there are few high-quality interventional studies on burnout prevention. A meta-analysis of eight studies found that organization-led interventions led to a small reduction in burnout (standardized mean difference 0.45; 95%CI, 0.38 to 0.62).33 The largest of these studies was a cluster-crossover trial which demonstrated that 2-week attending physician inpatient rotations led to less burnout than 4-week rotations.34 By contrast, our study found that longer periods of exposure to the internal medicine ward was protective against resident burnout. One possible explanation is that increased periods of exposure to the same training setting leads to enhanced autonomy over time, thereby promoting resiliency.30 Although our study did not demonstrate an overall association between post-rotation burnout and autonomy, it remains plausible that incremental changes in autonomy could have a protective effect against burnout. Given the limitations of our sample size, our finding should be considered exploratory in nature and requires future replication. However, this finding does at least suggest that the completion of a second consecutive internal medicine ward rotation is unlikely to increase the incidence of new onset burnout. Whether wellness initiatives are effective for preventing burnout on high-intensity rotations is unclear. Previous studies have investigated the use of reflection, meditation, and stress management for resident wellness, but have generally been of poor methodological quality.35 Nevertheless, until higher quality data are available, training programs should consider targeting their existing wellness initiatives towards residents participating in high-intensity rotations to maximize the potential benefit from such interventions.

Our study has limitations. First, approximately one-third of surveys were not completed. It is possible that those who chose not to complete surveys were more or less likely to experience burnout. Second, behaviors and attitudes were self-reported, which may not necessarily reflect a true change in clinical performance. Third, the regression analysis we performed for risk factors of burnout was limited by our small sample size and may be affected by residual confounding. Fourth, we did not explore whether specific interventions could be used to improve outcomes in those reporting burnout. Fifth, most of our respondents were first year residents. It is possible that senior residents experience less burnout as they develop specific coping skills for the internal medicine ward. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to all academic institutions and hospitals due to variations in clinical, administrative, and teaching practices.

CONCLUSION

Resident burnout is common on the internal medicine ward and is associated with worse clinical performance. Interventions are needed to mitigate the occurrence of burnout during periods of high-intensity clinical training in internal medicine.

Funding

Study funding was provided by the McMaster University Division of General Internal Medicine AFP Grant.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests. Dr. Wang is supported by the PSI Foundation – Research Trainee Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 3rd ed ed. Palo Alto, Calif. (577 College Ave., Palo Alto 94306): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- 2.Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A, Cabral JV, Medeiros L, Gurgel K, et al. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, Nikravesh R, Seligman L, Vasa M, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236–242. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00054.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, Colaiano JM, Satele DV, Sloan JA, et al. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(5):657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Eacker A, Harper W, Power D, Durning SJ, et al. Relationship Between Burnout and Professional Conduct and Attitudes Among US Medical Students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors Related to Physician Burnout and Its Consequences: A Review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8(11):98. doi: 10.3390/bs8110098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sajjadi S, Norena M, Wong H, Dodek P. Moral distress and burnout in internal medicine residents. Can Med Educ J. 2017;8(1):e36–e43. doi: 10.36834/cmej.36639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson K, Lank PM, Cheema N, Hartman N, Lovell EO. Comparing the Maslach Burnout Inventory to Other Well-Being Instruments in Emergency Medicine Residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(5):532–536. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00155.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, Prochazka AV. Burnout and Internal Medicine Resident Work-Hour Restrictions. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(22):2595–2600. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, et al. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brady KJS, Ni P, Sheldrick RC, Trockel MT, Shanafelt TD, Rowe SG, et al. Describing the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment symptoms associated with Maslach Burnout Inventory subscale scores in US physicians: an item response theory analysis. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00204-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Nedelec L, et al. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(7):e209385-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westbrook J, Sunderland N, Li L, Koyama A, McMullan R, Urwin R, et al. The prevalence and impact of unprofessional behaviour among hospital workers: a survey in seven Australian hospitals. Med J Aust. 2021;214(1):31–37. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabekaussen K, Scheepers RA, Heineman E, Haber AL, Lombarts K, Jaarsma D, et al. Health care professionals' perceptions of unprofessional behaviour in the clinical workplace. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MH, Mazenga AC, Simon K, Yu X, Ahmed S, Nyasulu P, et al. Burnout and self-reported suboptimal patient care amongst health care workers providing HIV care in Malawi. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zis P, Anagnostopoulos F, Sykioti P. Burnout in medical residents: a study based on the job demands-resources model. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:673279. doi: 10.1155/2014/673279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutter MM, Kellogg KC, Ferguson CM, Abbott WM, Warshaw AL. The impact of the 80-hour resident workweek on surgical residents and attending surgeons. Ann Surg. 2006;243(6):864–71. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000220042.48310.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, Herrin J, Wittlin NM, Yeazel M, et al. Association of Clinical Specialty With Symptoms of Burnout and Career Choice Regret Among US Resident Physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114–1130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe KK, Unti SM. Critical care rotation impact on pediatric resident mental health and burnout. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):181. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1021-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Driesman AS, Strauss EJ, Konda SR, Egol KA. Factors Associated With Orthopaedic Resident Burnout: A Pilot Study. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2020;28(21):900–906. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kok N, Gurp JV, Hoeven JGVD, Fuchs M, Hoedemaekers C, Zegers M. Complex interplay between moral distress and other risk factors of burnout in ICU professionals: findings from a cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2023;32(4):225–34. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C, Irvine F. What is 'moral distress'? A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(3):646–662. doi: 10.1177/0969733017724354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gopal R, Glasheen JJ, Miyoshi TJ, Prochazka AV. Burnout and internal medicine resident work-hour restrictions. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2595–600. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Vendeloo SN, Prins DJ, Verheyen CCPM, Prins JT, van den Heijkant F, van der Heijden FMMA, et al. The learning environment and resident burnout: a national study. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2018;7(2):120–5. doi: 10.1007/S40037-018-0405-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayward RS, Rockwood K, Sheehan GJ, Bass EB. A phenomenology of scut. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(5):372–376. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuo T, Takahashi O, Kitaoka K, Arioka H, Kobayashi D. Resident Burnout and Work Environment. Intern Med. 2021;60(9):1369–1376. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.5872-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brasel KJ, Pierre AL, Weigelt JA. Resident Work Hours: What They Are Really Doing. Archives of Surgery. 2004;139(5):490–494. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christino MA, Matson AP, Fischer SA, Reinert SE, Digiovanni CW, Fadale PD. Paperwork versus patient care: a nationwide survey of residents' perceptions of clinical documentation requirements and patient care. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):600–604. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00377.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, Lewith G, Kontopantelis E, Chew-Graham C, et al. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(2):195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucas BP, Trick WE, Evans AT, Mba B, Smith J, Das K, et al. Effects of 2- vs 4-week attending physician inpatient rotations on unplanned patient revisits, evaluations by trainees, and attending physician burnout: a randomized trial. Jama. 2012;308(21):2199–2207. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eskander J, Rajaguru PP, Greenberg PB. Evaluating Wellness Interventions for Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(1):58–69. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-00359.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]