Abstract

With its subsidy retention fund, the city of Ghent targets homeowners, who live in a dwelling of bad quality and do not have the resources to renovate or move out. Being in this no-choice situation, they are locked-in homeowners. Through this innovative policy instrument, Ghent aims to improve the quality of its housing stock targeting households who may not take up other renovation-encouraging instruments. To reach the households who would otherwise not be able to renovate, important efforts in outreaching and offering technical and social guidance accompany the renovation subsidy. Guidance activities substantially increase the cost of the instrument, but in reaching the households living in bad-quality houses, it has the potential to create major benefits not only technically but also socially as housing quality is related to well-being. Generally, the identification of a causal relationship is difficult as well-being and its mediators are complex matters. This case offered a unique opportunity to collect information from the beneficiaries on a range of well-being domains both before the renovation of their dwelling and after the renovation. Even though the research was restricted to short-term effects, the results suggest that improvements in different domains of well-being can be linked to the improvement of housing quality. These improvements in well-being in Ghent show that (local) government spending in housing renovation of locked-in homeowners can be an instrument to achieve social progress.

Keywords: Housing quality, Well-being, Subsidy retention fund, Locked-in homeowners

Introduction

An increasing amount of evidence shows that low housing quality may affect both physical and mental health outcomes [1–6]. Mold growth and damp are correlated with negative effects on health, mainly respiratory health [6, 7]. The strongest correlations are found with mental health. Stress or preoccupations about living conditions and affordability negatively influence mental health [8]. Improvement of warmth and energy efficiency can positively influence physical and mental health [2, 9, 10]. Some of the underlying mechanisms include the following: increased indoor warmth and comfort, reduced fuel costs, increased feelings of ease and pride, increased usable indoor space, increased motivation to tidy and clean the house. Currently, widespread energy poverty (i.e., the household’s inability to maintain minimum standards of thermal comfort) adds another scope to the relationship of energy efficiency and health, since energy poverty can cause more health issues to arise [11].

Housing improvement investments can also be linked to social relationships both within and outside the household as low housing quality may lead to domestic violence or intra-household conflicts and may affect the desire to invite people. Long-term effects on children’s development can be seen since low-quality housing is an important stress factor negatively affecting emotional and cognitive skills and is associated with a range of physical and mental problems [12, 13]. The longer children live in poor housing, the higher the probability of a lower level of education and future poverty [14].

Housing quality is found to be directly correlated to well-being [1, 15–18] with cold, dampness, and the affordability to keep the home warm as driving forces. A dwelling’s poor energy performance is often linked to energy poverty affecting well-being. Housing quality also affects well-being through its effect on other dimensions described above such as health and social connections. It can also affect the sources of future well-being through its effect on the human capital of children.

Renovation has the potential to contribute to well-being. However, on average, €52,000 per dwelling is needed to reach minimal housing quality and energy norms (based on 2019 costs) [19]. The houses of households with low incomes (Q1/Q2) are often in a worse state [20] leading to an even higher cost amounting to €61,000 (in Q1). Besides financial barriers [21], households may also face technical, administrative, organizational, knowledge-related, or other barriers to renovation [22–24].

Instruments to encourage renovation are available but do not reach households living in the worst houses. For Flanders, Heylen [25] shows that only 12% of the amount of renovation subsidies ends up with the households in the lowest income quintile. Knowledge of existing subsidies is often lower in this group, but also, application rates are lower [22]. Non-take-up is partially due to mistargeting and the conditions attached (e.g., requiring pre-financing). Unequal access to participate in the renovation wave may cause growing housing inequality, which may lead to increasing inequalities in dwelling-related outcomes discussed above. This shows the need for a renovation-encouraging instrument that has the potential to reach those in the worst-quality housing.

In Ghent, approximately 4.4% (= 6000) households are estimated to be locked-in homeowners [26, 27], living in a dwelling of bad quality and lacking the capability to improve its quality. To reach these households, the city introduced an innovative instrument: the subsidy retention fund [28]. It aims at supporting owner-occupiers who may not take up other policy instruments to encourage (energy efficiency) renovations, in spite of the great need of renovation. To reach the targeted households, large efforts in technical and social guidance accompany the subsidy. This, however, increases the cost of the instrument substantially but in reaching those households living in the worst-quality houses, it has the potential to create social benefits beyond the upgrade to good quality and energy-efficient housing, in terms of well-being. In their report on measuring social progress, Stiglitz et al. [29] even advocated to focus on well-being as a measure of social progress.

Subsidy Retention Fund “Gent knapt op” and Participants’ Profile

Description of the Subsidy Retention Fund in Ghent

For each participant, the public authorities provided a renovation budget of €30,000. The allowance is recurring over time to the public authorities [30]. “Recurring” takes place when the official ownership of the property changes (e.g., sale). At ownership change, the former owner has to return the initial allowance increased with a part of the added value. Through this concept, public finance is not limited to original beneficiaries but is reused for new renovation projects in the future.

Additional to the renovation budget, support involved a number of hours per dwelling ranging from 32 h for smooth cases up to 86 for very complex cases for technical support. For social support, this went from 85 h up to 311. The median cost of support was around half of the renovation budget.

In general, it is an instrument of indirect solidarity reducing economic inequality, and as in other welfare states, it is based on a human rights approach. Priority is given to those in vulnerable positions, like the locked-in homeowners. As a (city) government guarantees this solidarity, the instrument must be transparent. It comes therefore with a framework of conditions and includes evaluation to further improve it.

Profile of Participants

Based on the information collected during the selection process, the vulnerability of the selected homeowners clearly emerged. Most of the participants were single and almost half of them were single parents. Regarding the level of education, one in five applicants had not finished secondary education, and only a few participants had completed higher education.

The economic situation of the participants was precarious: less than half of the participants received a job-related income. Compared to average figures for Ghent or Flanders, we found that the participants face a higher risk of poverty and housing affordability problems.

Take-up of Renovation-Encouraging Subsidies

There was a high non-take-up among the participants regarding other (renovation) subsidies due to several reasons. First of all, there seemed to be lack of information. The renovation subsidy of the Flemish government and the subsidy for roof insulation were only known by half of the participants (52% and 51%, respectively), the Flemish energy loan (which would be interest-free for most of the participants) was known by only one of three participants (32%), and subsidies of the grid manager were even less known (only 13% of the participants).

Secondly, the renovation subsidies are often mistargeted (target group not being able to pre-finance or take loans or to cope with the work involved in the application or renovation process). The interviews with participants showed that approximately 70% considered social and technical support to be of great importance, playing an important role in the decision to participate in the project, especially for the older participants.

Hence, we conclude that the participants of the program “Gent knapt op” are owners in a socio-economic vulnerable situation, who are not in a financial position to (pre-)finance the renovation and show a relatively lower take-up of renovation and energy-efficiency subsidies. Many would not embark on a renovation process without guidance and support offered by technical supervisors and social workers.

Methodology Social Impact Measurement

Measuring the impact of housing on well-being is very complex not in the least because well-being is affected by a multitude of factors. Therefore, drawing causal relationships is almost impossible [1]. However, the experiment in Ghent offered a unique opportunity to collect information on indicators in different housing-related aspects of well-being such as satisfaction with housing, subjective health, and social contacts by interviewing the participants before and after the renovation of their dwelling.

We measured the program-level impact by comparing the indicators collected before and after the renovation works. We considered but did not provide statistical tests (such as paired t-tests) given the low sample size of the pre- and post-group (only 40). Low sample sizes tend to have low statistical power and may therefore not allow to detect a significant difference. As we would not be able to conclude if non-significance is due to low sample size or the non-existence of an effect, we decided not to report the tests and only draw conclusions on the group under analysis.

Unfortunately, the project implementation took place while the COVID-pandemic prevailed. This may have biased the results as, for instance, this may have given rise to a lower occurrence of other diseases and a higher occurrence of depression or stress. Moreover, the pandemic delayed the recruitment of participants and the renovation works which did not allow to capture longer term effects.

Data Collection

Based on a questionnaire, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected, before and 3 to 6 months after the renovation. The initial in-depth interviews for the baseline measurement were conducted by the social workers, who had already developed a relationship of trust with the beneficiaries. In the post-renovation stage, researchers conducted the post-renovation questionnaire. This allowed the participants to speak openly about the project and to evaluate the different project partners.

In total, 65 pre-renovation and 46 post-renovation interviews were administered. This was complemented with data from registration documents, available for 85 homeowners. For the social impact measurement, only the data of the 40 participants with both a baseline and a post-renovation interview were used. The limited number of observations does not allow for more detailed analysis.

The Objective Quality of Housing

Before and after renovation, the housing quality was measured by the housing control service of the City of Ghent using the Flemish Housing Code to determine the quality of the house. In order to be included in the project, a house had to be of insufficient quality, but at the same time, it had to be feasible to reach adequate quality with maximum €30,000.

Indicators Related to Well-being

We assess the integrated impact of housing renovation on well-being through the pre- and post-renovation (subjective) measurement of a set of indicators representing the housing-related aspects of well-being. Indicators that can have an effect on well-being are suggested in the OECD framework [18]. The housing aspects include housing quality indicators, housing affordability, and housing satisfaction. Housing satisfaction can be understood as the “perceived gap between needs and aspirations and the effective housing situation” [31]. Other aspects that often show a link with housing are as follows: subjective general, physical and mental health indicators, and social connections. Where available, questions were drawn from validated questionnaires. The indicators effectively used to capture the different aspects can differ but include the condition of the house, dampness, coldness, and (dis)satisfaction with housing [32].

As much as possible, validated questions and indicators were used to construct the questionnaire. The housing quality is objectively screened (see higher). The following social impact indicators are collected from interviews:

Housing satisfaction:

To what extent are you satisfied with the dwelling you currently live in? (five-point scale)

To what extent are you satisfied with the general comfort of your home? (summer/winter) (five-point scale)

Subjective housing quality:

How often did you experience one of the following problems (over a certain period)? Odor nuisance, mold growth on internal and/or external walls, moisture seeping through the roof, moisture seeping through walls or floor, moisture seeping through windows, too little space for the number of inhabitants, too little privacy for the residents, too cold in wintertime, too warm in summertime (answer on a three-point scale)

Subjective general health:

How is (household member’s) health in general? (asked for all household members, five-point scale)

Mental health:

How often in the last 4 weeks did you feel tired; did you feel lonely; did you feel stressed; did you feel depressed?

Affecting subjective and/or mental health:

How difficult do you find the motivation to tidy up/clean the house?

Inter- and intra-household social connections:

For the subject of social connections, we use a retro- and prospective approach.

When receiving visitors is allowed (cf. corona measures), how often do you think you will receive family, friends or acquaintances, or neighbors in your house (spontaneously or by invitation), compared to before the renovation?

Intra-household connections were measured by:

Did the bad-quality situation of the dwelling before the renovation give rise to any conflicts?

Has anything changed in the relationship between the inhabitants for the worse or better since the renovation?

Human capital potential of children:

Does your child/do your children have a good place to work for school in your current home?

Improvements to Housing Quality and Energy Efficiency

On average, 86% of the total budget per house was spent on housing quality. In more than 75% of the houses, electrical and roofing works were carried out, and the external joinery was renewed. Heating works were carried out in 61% of the houses. Almost half of the houses also required treatment against moist. After renovation, only a minority of houses were not yet compliant with the Flemish Housing Code because the owners planned to carry out minor works themselves in order to reduce costs.

Measures that contributed to improved energy performance accounted for 46% of the total budget. The energy performance of the houses improved from an average score of 482 kWh/m2 year before the renovation, corresponding to an energy label E, to on average label C (between 300 and 200 kWh/m2 year) after renovation.

Social Changes

Below, we describe the results, restricted to those participants who granted an interview both before and after the renovation. The number of respondents can vary between the indicators as respondents did not always answer all questions.

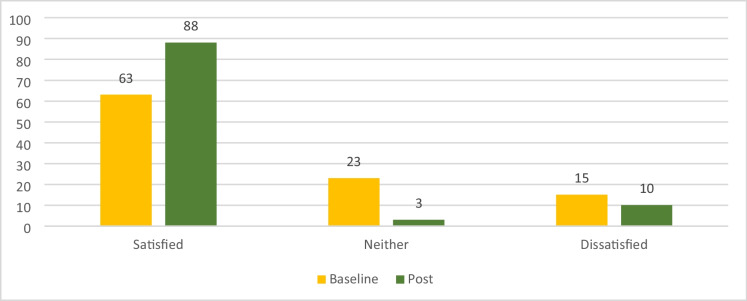

Housing

Housing satisfaction has increased strongly (Fig. 1) from 63% of the participants being (very) satisfied before to 88% (very) satisfied with the dwelling they live in after the renovation. The share being very satisfied with their dwelling increased from 8 to 58%. Reasons for this increased satisfaction included renovation of the kitchen, new windows, insulation, heating, improved safety, and healthiness of the house. Also, personal effects were mentioned: feeling more at home, less stress, enjoying the cleanliness, feeling the energy to tackle other problems.

Fig. 1.

Percentage participants (very) satisfied/(very) dissatisfied with their dwelling.

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N = 40

Despite the increase in percentage satisfied homeowners, some remained unsatisfied or even became unsatisfied after the renovation (Table 1). For most of the unsatisfied homeowners, this can be ascribed to the short period elapsed after the renovation: some were still experiencing hindrance from the works (e.g., not everything unpacked, dust, not knowing well how to operate new features), some still had to do some finishing works themselves, or the participants had other renovation priorities than what was decided in the renovation plan).

Table 1.

Changes in participant satisfaction with their dwelling

| After renovation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not satisfied | Satisfied | ||

| Before renovation | Not satisfied | 2 | 13 |

| Satisfied | 3 | 22 | |

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N = 40

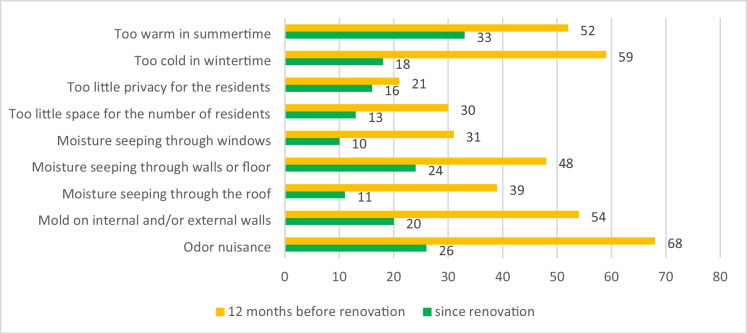

Both before and after the renovation, participants were asked to evaluate the experience of all types of nuisances. Due to the limited timeframe of the study and delays due to corona, it was not possible to ask parallel questions before and after the renovation. In the pre-renovation questionnaire, participants were asked to evaluate the previous 12 months; in the post-renovation questionnaire, participants were asked to evaluate the period since the renovation (which was often 3 to 6 months) (Fig. 2). If the respondents felt they could not judge the situation yet, they did not answer the question. We found strong decreases in the experience of all types of nuisances. Especially the odor nuisance decreased strongly from being experienced by 68% of participants before the renovation to 26% after the renovation. Likewise, the percentage of participants suffering from too cold homes in wintertime decreased sharply from 59 to 18%. Mold growth and moisture situations also improved. We also see that space and privacy hinderance decreased.

Fig. 2.

Percentage participants who experienced nuisance sometimes or usually/always in the 12 months before renovation/since renovation.

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N from 38 to 40; N “too warm in summertime” = 34 (some participants did not experience a summer yet since renovation)

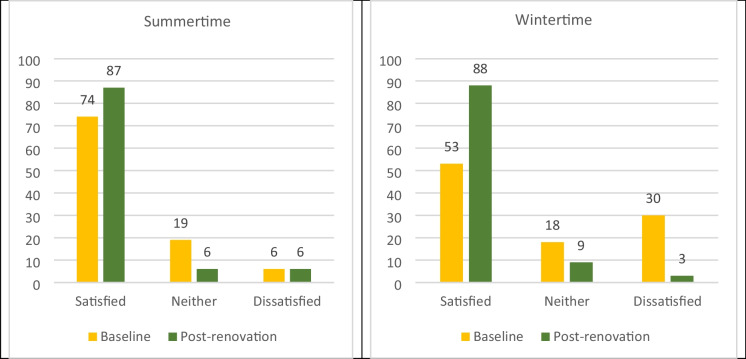

Improvements regarding nuisance from temperature, moisture, mold growth, or odor may lead to improved levels of comfort and health. In Fig. 3, we find this impact represented in the improved satisfaction with general comfort of the house. Especially in wintertime, the levels of pre-renovation satisfaction with comfort were fairly low (only 53% of participants being satisfied). After the renovation, 88% is satisfied with the general comfort in their home.

Fig. 3.

Satisfaction (in % of respondents) with general comfort in home during summertime/wintertime.

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N summertime = 31; N wintertime = 34

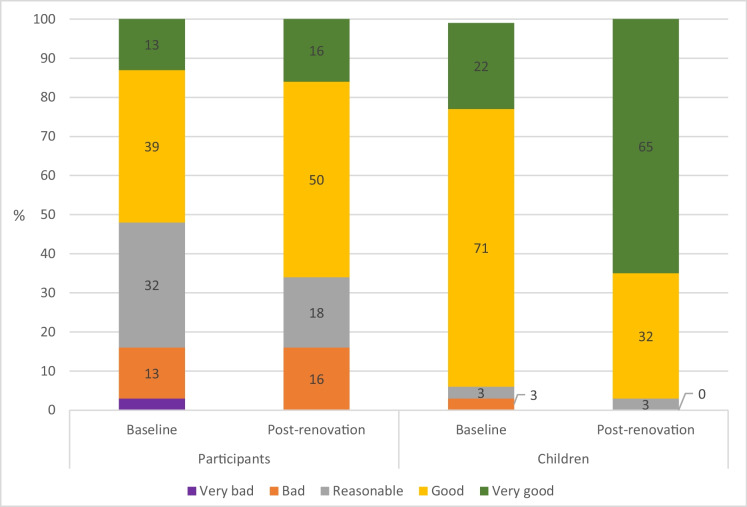

Health

Even in the short time after renovation, we found evidence of positive effects on the subjective general health situation of participants and their children living in the house. A larger share of the participants assessed their health as being good or very good (from 52% before to 66% after the renovation) (Fig. 4). This number is generally lower when compared to a general cross-section of the population of the city of Ghent (75%) [33] but not when compared to lower-income populations in Flanders (58% and 77% for the lowest quintiles) [34]. For children, we found a large increase in the share in very good general health (from 22% before to 65% after renovation).

Fig. 4.

Subjective general health of participants and children.

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N participants = 38; N children = 63

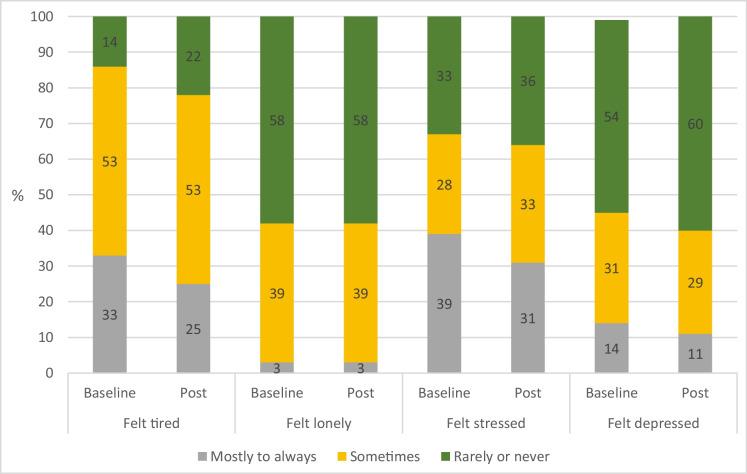

Looking at mental health (Fig. 5), we did not find strong improvements. The share of participants feeling rarely or never tired increased, as well as the share feeling mostly to always stressed, while the share feeling rarely or never depressed increased. We found that some people at the time of the post-renovation interview were still in a state of tiredness from the renovations or the cleaning up, and there were still some finishings to undertake. This may have an effect on the emotional state of the participants.

Fig. 5.

Emotional state of participants in the last 4 weeks.

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N participants = 36

A strong improvement in the perceived difficulty of tidying up or cleaning was perceived (Fig. 6). While before the renovation, 32% found it difficult to tidy up the house, only 16% regarded tidying up as difficult afterwards. The improvement was even more outspoken with respect to cleaning the house. Whereas more than half of the participants found this difficult before the renovation (e.g., due to a lack of visible effect of cleaning or lack of storage space), only 13% found this difficult afterwards.

Fig. 6.

Percentage finding it (very) difficult to tidy up/clean.

Source: baseline and post-renovation measurement GKO; N tidy up = 38; N clean = 37

Social Connections

Due to the corona measures still in place during some of the post-renovation interviews, the question on inter-household social contact in the house was asked hypothetically. Thirty-seven percent of the participants thought they would receive more social contacts in the house than before the renovation.

The change in intra-household connections was measured by retroactive questions included in the post-renovation questionnaire. Ten of the 38 post-renovation respondents with housemates indicated that before the renovation, the poor state of the dwelling gave rise to intra-household conflicts. Of these ten, six indicated that relations had improved after the renovation, while four indicated that relations remained unchanged. On average, the renovation led to an improvement in the situation regarding conflicts between housemates.

Education

Having a convenient place to work for school may affect the educational potential for children. Before the renovation, nearly one out of three (29%) of the participants with children indicated that their house did not offer a good place to work for school. The children’s rooms were too cold or too warm to study or there was no safe power socket in the room, or too many children had to share one place. After the renovation, only 11% of the households with children mentioned lacking a good place to work for school.

Conclusion

With a subsidy retention fund, the city of Ghent aimed to improve the quality of its housing supply by targeting locked-in residents. They received a budget for renovation as well as technical and social support during the renovation process. The support offered was assessed as important by a large majority of the participants (70%). Based on the interviews, those who have taken up the instrument would not have been able to renovate their house without the fund and the support offered. By targeting locked-in residents, housing-related inequalities can be reduced.

Both housing quality and energy performance improved substantially. The improvements contributed to the potential to decrease energy poverty among the participants.

Moreover, also housing-related social outcomes were improved. The interviews showed that the renovation had positive effects on a range of indicators such as higher satisfaction levels with their dwelling, decreases in the experience of all sorts of nuisance (strongest for odor and coldness during winter), and higher satisfaction levels with comfort, especially in wintertime (confirming the hypothesis of a lower prevalence of energy poverty).

Also in the domain of health, improvements were found. The self-rated “being in good health” increased, most strikingly for children. We could not find strong effects on mental health (yet). This could be due to the fact that a lot of the after-renovation interviews had to be taken shortly after the renovation or even before the complete finishing of the renovation, which is often a stressful period. By contrast, we found large effects in the perceived difficulty of tidying up and cleaning which may have effects on physical and mental health.

With regard to social connections, the desire to invite other people in the house had risen. In addition, around half of the participants who had indicated that before the renovation the poor state of the dwelling gave rise to intra-household conflicts, said that relations had improved.

Finally, the percentage of children not having a convenient place to work for school decreased. Having a convenient place to work for school may contribute to better school performance, being a source of future well-being through better human capital outcomes.

The improvements on the range of indicators above suggest that the housing quality improvement leads to higher well-being levels of the participants of “Gent knapt op.”

So while this instrument appears rather costly in upfront public investment (€30,000 for the renovation plus €16,770 median cost for the support), when it is compared to other instruments that invest in housing quality for low-income households, it is actually in the same range. For example, the current value (in 2016 amount) of public expenditure for being able to offer 40 years in a social rental agency or a social housing company home is estimated to be around € 86,000 on average [35]. Based on the answers to the questions, the majority of the locked-in homeowners who participated in “Gent knapt op” plan to live in their renovated dwelling as long as possible. And at the end of the term, when the house is disposed of, the amount invested recurs to the city and can be used to renovate another house.

The instrument is unique in that it targets a group that is not able to take up other policy instruments that aim to encourage renovation. By improving the quality and energy-efficiency situation of the target group, not only housing inequality but also inequality of outcomes in health, social connections, education, and (future) well-being can be improved. Hence, the instrument might actually be very cost-effective in improving the quality and energy efficiency of a city’s housing supply and achieving higher levels of well-being and social progress.

Acknowledgements

The research has been funded by the European Union Urban Innovative Actions Initiative (https://www.uia-initiative.eu/en/uia-cities/ghent-call3). We thank the people of the city of Ghent for constructive feedback and co-operation and the participants of the project for sharing their experiences with us. We are grateful for the many useful comments from participants of the workshop ‘Residential context of health’ at the European Network for Housing Research conference in Barcelona (31/8/2022–2/9/2022).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rolfe S, Garnham L, Godwin J, Anderson I, Seaman P, Donaldson C. Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1138. Published Jul 20 10.1186/s12889-020-09224-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew, M. Housing improvements for health and associated socio‐economic outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013 (2). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Braubach M, Jacobs DE, Ormandy D. Environmental burden of disease associated with inadequate housing. A method guide to the quantification of health effects of selected housing risks in the WHO European Region. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen; 2011. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/108587.

- 4.Clark C, Myron R, Stansfeld S, Candy B. A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health. J Public Ment Health. 2007;6(2):14–27. doi: 10.1108/17465729200700011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson E, Adams R. Housing stress and the mental health and wellbeing of families. The Australian Institute of Family Studies. Published 2008. https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/b12_0.pdf. Accessed 2021.

- 6.Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):758–768. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norbäck D, Lampa E, Engvall K. Asthma, allergy and eczema among adults in multifamily houses in Stockholm (3-HE study)-associations with building characteristics, home environment and energy use for heating. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e112960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liddell C, Guiney C. Living in a cold and damp home: frameworks for understanding impacts on mental well-being”. Public Health. 2015;129(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson M, Petticrew M, Bambra C, Sowden AJ, Wright KE, Whitehead M. Housing and health inequalities: a synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health Place. 2011;17(1):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willand N, Ridley I, Maller C. Towards explaining the health impacts of residential energy efficiency interventions - a realist review. Part 1: pathways. Soc Sci Med. 2015;61(133):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polimeni JM, Simionescu M, Iorgulescu RI. Energy poverty and personal health in the EU. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(18):11459. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubeau B, Vanobbergen B. Kinderen en huisvesting. Advies Vlaamse woonraad ism Kinderrechtencommissariaat. Advies 2017/02. Vlaamse Woonraad, Brussel; 2017.

- 13.Culora A, Janta B. Understanding the housing conditions experienced by children in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes M., Butt S, Tomaszewski W. The dynamics of bad housing: the impact of bad housing on the living standards of children. National Centre for Social Research, London; 2008

- 15.Huebner GM, Oreszczyn T, Direk K, Hamilton I. The relationship between the built environment and subjective wellbeing – analysis of cross-sectional data from the English Housing Survey. J Environ Psychol. 2022;80:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turcu C. Greater than the sum of its parts: carbon reductions, health and wellbeing in the housing sector. Published 2020. https://enhr.net/uncategorized/derde-bericht/. Accessed 2021.

- 17.WHO. WHO housing and health guidelines. World Health Organization (WHO). Published 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276001/9789241550376-eng.pdf. Accessed 2021. [PubMed]

- 18.OECD. How’s Life? Measuring Well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011. 10.1787/9789264121164-en.

- 19.Ryckewaert M, Van den Houte K, Vanderstraeten L, Leysen J. Inschatting van de renovatiekosten om het Vlaamse woningpatrimonium aan te passen aan de woningkwaliteits- en energetische vereisten. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen; 2019.

- 20.Vanderstraeten L, Ryckewaert M. Grote Woononderzoek 2013. Deel 3. Technische woningkwaliteit. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen; 2015.

- 21.Albrecht J, Hamels S. De financiële barrière voor klimaat- en comfortrenovaties. Itinera Institute Analyse 2020/9; Brussel: Itinera; 2020.

- 22.Van den Broeck K. Drempels voor renovatie aan de vraagzijde. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen; 2019.

- 23.D’Oca S, Ferrante A, Ferrer C, Pernetti R, Gralka A, Sebastian R, op ‘t Veld P. Technical, financial, and social barriers and challenges in deep building renovation: integration of lessons learned from the H2020 cluster projects, Buildings. 2018;8(174):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Artola I, Rademaekers K, Williams R, Yearwood J. Boosting building renovation: what potential and value for Europe?. Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Brussels: European Union; 2016; IP/A/ITRE/2013-046.

- 25.Heylen K. Woonsubsidies in Vlaanderen. Verdelingsanalyse voor 2018 en evolutie sinds 2008. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen; 2020.

- 26.De Decker P, Meeus B, Pannecoucke I, Schillebeeckx E, Verstraete J, Volckaert E. editors. Woonnood in Vlaanderen: Feiten/Mythen/Voorstellen. Antwerpen: Garant; 2015.

- 27.Vanderstraeten L, Ryckewaert M. Noodkopers, noodeigenaars en captive renters in Vlaanderen. Nadere analyses op basis van het GWO2013. Steunpunt Wonen. 2019;59p. https://archief.steunpuntwonen.be/Documenten_2016-2020/Onderzoek_Werkpakketten/WP_2_Diepgaandere_analyses_op_basis_van_het_GWO2013/WP2d_TOELICHTING.html.

- 28.CLT Gent, OCMW Gent. “Dampoort knapT OP! Wijkrenovatie met noodkopers”. OCMW Gent. Published 2016. https://stad.gent/sites/default/files/media/documents/Dampoort%20knapT%20OP%21.pdf. Accessed 2019.

- 29.Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi JP. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Brussels: EC Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; 2009.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdfAccessed 2022.

- 30.Bielen L, Versele A. Sustainable communities through an innovative renovation process: Subsidy retention to improve living conditions of captive residents. In Rodríguez Álvarez J & Soares Gonçalves JC (Eds.): Planning Post Carbon Cities. Proceedings of the 35th PLEA Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Vol.1: 624-628, A Coruña: University of A Coruña; 2020. 10.17979/spudc.9788497497947.

- 31.Galster GC. Identifying the correlates of dwelling satisfaction: an empirical critique. Environ Behav. 1987;19(5):539–568. doi: 10.1177/0013916587195001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Social Investment Agency. Measuring the wellbeing impacts of public policy: social housing. Using linked administrative and survey data to evaluate the wellbeing impacts of receiving social housing. Wellington: New Zealand Government SIA-2018–0105. 2018;48p. https://swa.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Measuring-the-wellbeing-impacts-of-public-policy-social-housing.pdf.

- 33.Agentschap Binnenlands bestuur. Gemeente-Stadsmonitor, Jouw gemeentescan, Gent, Benchmark 13 centrumsteden. 2023. 219p. https://gsminfo.blob.core.windows.net/$web/Rapporten_outputs/JouwGemeentescan_13CS/GSM_JouwGemeentescan_13CS_Gent.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2023.

- 34.Sciensano, Belgian Health Interactive Survey. Module: Subjective health - Update 2018. https://sas.sciensano.be/SASStoredProcess/guest?_program=/HISIA/SP/selectmod2018&module=subjhlth. Accessed 28 June 2023.

- 35.Van den Broeck K, Winters S. Kosteneffectiviteit en efficiëntie van sociale huisvestingsmaatschappijen en sociale verhuurkantoren. Leuven: Steunpunt Wonen; 2018.