Abstract

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires faculty to pursue annual development to enhance their teaching skills. Few studies exist on how to identify and improve the quality of teaching provided by faculty educators. Understanding the correlation between numeric scores assigned to faculty educators and their tangible, practical teaching skills would be beneficial.

Objective

This study aimed to identify and describe qualities that differentiate numerically highly rated and low-rated physician educators.

Design

This observational mixed-methods study evaluated attending physician educators between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2021. Quantitative analysis involved descriptive statistics, normalization of scores, and stratification of faculty into tertiles based on a summary score. We compared the highest and lowest tertiles during qualitative analyses of residents’ comments.

Participants

Twenty-five attending physicians and 111 residents in an internal medicine residency program.

Main Measures

Resident evaluations of faculty educators, including 724 individual assessments of faculty educators on 15 variables related to the ACGME core competencies.

Key Results

Quantitative analyses revealed variation in attending physician educators’ performance across the ACGME core competencies. The highest-rated teaching qualities were interpersonal and communication skills, medical knowledge, and professionalism, while the lowest-rated teaching quality was systems-based practice. Qualitative analyses identified themes distinguishing high-quality from low-quality attending physician educators, such as balancing autonomy and supervision, role modeling, engagement, availability, compassion, and excellent teaching.

Conclusions

This study provides insights into areas where attending physicians’ educational strategies can be improved, emphasizing the importance of role modeling and effective communication. Ongoing efforts are needed to enhance the quality of faculty educators and resident education in internal medicine residency programs.

KEY WORDS: faculty educators, teaching skills, resident evaluations, teaching quality

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) Core Program Requirements mandate that faculty members annually pursue development designed to enhance their educator skills.1 Despite this requirement, variability continues in the quality of teaching provided by physician educators, both from the perspective of residents and more objective measures.2–5 Reported variability includes teaching styles, expectations attendings have of residents, and inconsistencies in how feedback is delivered.2–4 It remains unclear how the numerical scores given to attendings by resident raters characterize the quality of physician educators’ skills.

High-quality, engaged precepting by attendings is associated with improved overall resident performance and wellness5–7, and has been shown to impact learners’ ultimate choice of medical specialty8. Less often reported is the quality of attending educators according to ACGME’s six core competencies: (1) patient care, (2) medical knowledge, (3) practice-based learning and improvement, (4) systems-based practice, (5) interpersonal and communication skills, and (6) professionalism9. Guerrero et al. analyzed 1378 responses from residents in 12 different specialties across training years. Between 80 and 97% rated their training for ACGME competencies as adequate, with patient care activities and observations of attending physicians and peers being most helpful.10 Lee et al. assessed the effectiveness of a faculty development program designed to increase teaching and assessment skills needed for ACGME competencies, and showed clinical instructors could successfully apply skills learned.11

Few studies have focused on identifying and improving the quality of teaching provided by attending physicians during residency education. The Division of Hospital Medicine at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) has recently transitioned to a Core Competency-based resident assessment of attending physicians. Our study sought to utilize these assessments to determine the characteristics that residents associate with high teaching quality.

METHODS

Study Setting

Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) is a 576-bed teaching hospital. OHSU’s medical teaching service consisted of 46 attending physicians, all of whom were hospitalists providing care and medical consultation to hospitalized patients, teaching residents, conducting research, and co-leading the division; however, only 25 attendings met the inclusion criteria of teaching for at least 3 years or more during the study period. The Internal Medicine (IM) Residency Program includes 111 residents across three years of training with 104 (93.7%) categorical and five (4.5%) preliminary residents. The OHSU IM program includes an inpatient wards rotation that typically spans 3 weeks within a 3+1 schedule.

Instrument Development and Implementation

A 15-item assessment instrument with two to four variables per core ACGME competency was developed in 2015 as part of a larger competency-based redesign of all trainee and faculty assessments. The assessment was modified from an existing validated evaluation tool assessing clinical teachers.12 This evaluation is routinely filled out by all residents at the conclusion of their inpatient internal medicine rotation at OHSU. The scale contained six response options (1=never/rarely, 2= occasionally, 3= frequently, 4= consistently, 5= exceptional, and N/A). The instrument included space for comments after each competency section. Assessment data were anonymous and captured via MedHub13 between 7/1/2015 and 6/30/2021. Faculty names were replaced with a study identifier during analyses. We also sent a five-question survey to attending physicians to characterize their demographic information and how long they had been precepting trainees. OHSU’s Institutional Review Board reviewed study activities, which were considered quality improvement efforts and deemed not human subjects research (IRB #25005).

Data Analyses

For quantitative analyses, we calculated descriptive statistics for each faculty-educator assessment variable, including frequencies and percentiles. Means, standard deviations, and ranges in scores were calculated for each variable and as summary scores for each core ACGME competency. Further, we normalized the scores on a scale of 0–100 to identify which ACGME Core Competencies were rated highest and lowest by residents. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the internal consistency of the rating scale for each ACGME core competency. To identify high- and low-performing attendings, we calculated a summary score that included all their assessments by residents and then stratified these into tertiles of high, medium, and low performers.

For qualitative analyses, we used a positive deviance approach, which assists in explaining causes of variation14 by posing the research question, “What characteristics distinguish high quality from low quality attending physician educators?” We retained comments from the highest and lowest tertiles to include in qualitative analyses. We used classical content analysis15 to analyze residents’ comments, which involved an iterative process of open and axial coding, sharing and discussing the codes in consensus meetings, separating and/or collapsing codes and creating descriptions to characterize themes, and selecting exemplars that best reflected them. We excluded attending faculty who had fewer than 15 assessments by residents. Because of similarities in findings, we grouped the ACGME Core Competencies when presenting findings into (1) Patient Care and Medical Knowledge, (2) Systems-based Practice and Practice-based Learning and Improvement, and (3) Interpersonal and Communication Skills and Professionalism.

RESULTS

Quantitative Findings

Twenty-five attending educators were assessed by residents during the study period, producing 724 individual attending physician assessments. Four of the 25 attendings had fewer than 15 assessments and thus were not included in further analysis. Eighteen completed the demographics survey (72.0% response rate). Characteristics of attendings included average age of 44 years, predominantly female, white, non-Hispanic, and precepting for an average of about 13 years (Table 1). Quality of physician attending skills as educators ranged from 4.10 (SD=1.10; range 1–5) for “Demonstrates incorporation of cost awareness principles” to 4.59 (SD=0.59; range 2–5) for “Displays enthusiasm for teaching” (Table 2). In terms of teaching quality according to ACGME core competency, the highest rating for attending educators was for Interpersonal and Communication Skills (normalized score=90.1), closely followed by Medical Knowledge and Professionalism (Normalized scores=90.0). The lowest rated teaching quality was for Systems-based practice (normalized scores=85.2) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Attending Physician Educator Participants

| Physician educator characteristics (n=25) | (n=18) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) in years | 44.2 (8.3) | -- |

| Range | 36–62 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8 | 44.4% |

| Female | 10 | 55.6% |

| Race | ||

| White | 15 | 83.3% |

| Mixed race/other | 1 | 5.6% |

| Prefer not to answer/missing | 2 | 11.1% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 11.1% |

| Non-Hispanic | 14 | 77.8% |

| Prefer not to answer/missing | 2 | 11.1% |

| Length of time precepting students/residents | ||

| Mean (SD) in years | 12.9 (7.8) | |

| Range | 6-30 | |

Table 2.

Assessment Ratings for Variables According to ACGME Core Competency (n=724 Assessments for 25 Physician Attending Educators)

| Assessment variable | Mean score (SD) Range |

Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Patient care (highest possible score=15; normalized score=89.1) |

Raw summary score 13.36 (1.65) 6-15 |

0.76 |

| Models/teaches effective use of the history and physical exam at the bedside. |

4.43 (0.75) 1–5 |

|

| Provides appropriate balance of supervision and autonomy. |

4.44 (0.67) 2–5 |

|

| Discusses diagnostic and treatment plans for each patient, providing appropriate direction |

4.48 (0.60) 2–5 |

|

| Medical knowledge (highest possible score=10; normalized score=90.0) |

Summary score 9.00 (1.07) 6–10 |

0.80 |

| Tailors teaching to address relevant patient issues. |

4.46 (0.60) 2–5 |

|

| Demonstrates proficiency as a diagnostician. |

4.54 (0.57) 2–5 |

|

| Practice-based learning and improvement (highest possible score=20; normalized score=88.5) |

Summary score 17.70 (2.38) (4–20) |

0.84 |

| Displays enthusiasm for teaching |

4.59 (0.59) 2–5 |

|

| Provides positive/constructive feedback |

4.44 (0.84) 0–5 |

|

| Solicits/is open to feedback |

4.38 (0.84) 1–5 |

|

| Encourages further learning from discussions/outside reading |

4.29 (0.74) 1–5 |

|

| Systems-based practice (highest possible score=10; normalized score=85.2) |

Summary score 8.52 (1.52) 0–10 |

0.64 |

| Demonstrates team management by utilizing the skills and coordinating activities of interprofessional team members |

4.42 (0.65) 1–5 |

|

| Demonstrates incorporation of cost awareness principles |

4.10 (1.10) 1–5 |

|

| Interpersonal and communication skills (highest possible score=10; normalized score=90.1) |

Summary score 9.05 (1.15) 4–10 |

0.88 |

| Engages in active, collaborative communication with all members of the team |

4.53 (0.59) 2-5 |

|

| Encourages all learners to participate in patient care discussions |

4.51 (0.63) 1–5 |

|

| Professionalism (highest possible score=10; normalized score=90.0) |

Summary score 9.0 (1.14) 5–10 |

.72 |

| Prioritizes multiple competing demands to complete tasks/responsibilities in a timely effective manner |

4.41 (0.72) 1-5 |

|

| Provides leadership that respects patient dignity and autonomy |

4.56 (0.57) 3–5 |

|

| Overall summary score (normalized score=88.8) |

66.6 (7.51) 37–75 |

0.92 |

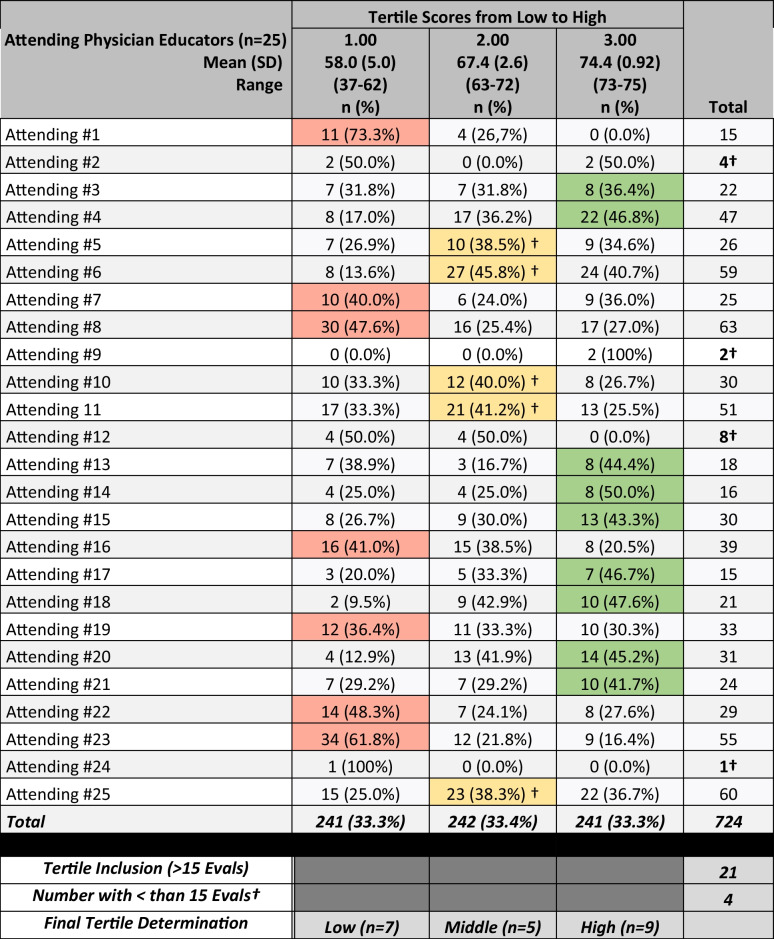

The number of resident assessments for the remaining faculty ranged from 15 to 63 (mean=33.8). All but one attending had assessments that spanned all three tertiles (Table 3). The summary mean score in the lowest tertile was 58 (SD=5.0; range=37–62), and the attendings who most often scored in this tertile compared to the middle and upper tertiles were attendings #1, #7, #8, #16, #19, #22, and #23 (n=7) (Table 3). The summary mean score in the middle tertile was 67.4 (SD=2.6; range=63–72), including attendings #5, #6, #10, #11, and #25 (n=5). The summary mean score in the highest tertile was 74.4 (SD=0.92; range 73–75) for Attendings #3, #4, #13, #14, #15, #17, #18, #20, and #21 (n=9). Based on these findings, qualitative comments from 16 physician attending educators (those in the first and third tertiles) were included in analyses.

Table 3.

Tertile Determination for Positive Deviance Qualitative Analysis Approach

†Excluded from qualitative analyses

Legend: green, highest performers; yellow, middle performers; red, lower performers

Qualitative Findings

Under Patient Care and Medical Knowledge, six themes emerged as being characteristics of high-quality attendings, including balance (e.g., balancing supervision and autonomy); role modeling; engaging or knowing when and how to attract and involve learners; availability to learners and team members; compassion with trainees as well as patients and families; and excellent teaching (Table 4).

Table 4.

Emergent Themes on High-Performing Faculty Educators as Assessed by Internal Medicine Residents

| High-performing faculty educators (first tertile) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emergent themes | Description | Exemplars |

| Patient care and medical knowledge | ||

| Balance | Balancing supervision vs. autonomy and practical tips vs. in-depth explanations |

• “This attending was great about providing autonomy both with medical decision making and with conversation-leading while at bedside.” [Attending #17] • “Good medical and practical knowledge, and provided many tips about how to work practically as a hospitalist.” [Attending #1] |

| Role model | Application of knowledge/demonstration of behaviors important to becoming an excellent physician |

• “Dr. X’s breadth of knowledge is awe-inspiring and I only wish that we had more didactic time during rounds.” [Attending #21] • “Has a very calming presence with patients. Speaks on a patient level without being belittling. [Attending #19] |

| Engaging | Knowing when and how to involve learners |

• “Dr. X provides exceptional ‘teaching moments’ on a case-by- case basis.” [Attending #6] • “Very good at getting all level of learner involved. He is very good and making the team learning fun and engaging (with a little bit of a history lesson as well which is great!) Able to teach and communicate w/ ease.” [Attending #16] |

| Availability | Being accessible to learners and team members | • “Makes time nearly every day to take the medical students (and the residents when possible!) to bedside to demonstrate physical exam findings and leads discussions re: how to interpret them.” [Attending #9] |

| Compassion | Expresses empathy with trainees, patients, and families |

• “Helped prep team members before potentially difficult conversations and encounters.” [Attending #12] • “Dr X provided a very calming presence to the patients when talking with them and the family, it was obvious that the patients felt well cared for in his hands.” [Attending #18] |

| Excellent teaching | Educates in ways that make learning memorable |

• “I appreciated that most of the teaching was focused on providing a framework rather than memorization, good use of illness scripts.” [Attending #8] • “Dr. X demonstrates exceptional physical exam at bedside, always pointing out subtle but interesting findings that inform our assessment of patients.” [Attending #14] |

| Systems-based practice and practice-based learning and improvement | ||

| Organizational and conversational | Guided coordination of patient care involving multiple team members or complex medical and psychosocial care issues |

• “Helped coordinate a particularly difficult psychiatric transfer following a formalized county review (including an in-hospital court hearing with deposition by the medical team); all of which was quite new to me.” [Attending #7] • “Very aware of services and available assistance. Able to guide in utilizing maximal assistance for efficiency.” [Attending #21] |

| Teaching/learning related | The ability to both deliver and receive meaningful/actionable feedback |

• “Tangible concrete feedback, easy to implement. Makes a large difference in confidence and desire to seek additional feedback and assistance.” [Attending #6] • “Obviously wants the residents to learn and grow as physicians, but also is dedicated to self-improvement.” [Attending #7] |

| Interpersonal communication and professionalism | ||

| Tailored role modeling | Meets the learners where they are and role models effective communication behaviors across many care team members |

• “She was great with positive reinforcement, especially with the medical students that participated in a ‘mock rounds’ with presentations prior to the actual start on the wards.” [Attending #18] • “Models effective communication between all of the care team members, consultants, PCPs, families, etc.” [Attending #19] • “Dr X did an excellent job modeling communication with all team members, always professional and mindful of alternative viewpoints.” [Attending #23] |

Under Systems-based Practice (SBP) and Practice-based Learning and Improvement (PBLI), two themes emerged. First was guided coordination of patient care that involved multiple team members or complex medical and psychosocial care issues. Second was the ability to both deliver and receive meaningful/actionable feedback.

One emergent theme reflecting low-quality attending physician educators for Patient Care and Medical Knowledge (PC&MK) was inefficiency on rounds, which caused stress and did not allow learners to complete their work in a timely manner (Table 5). Under SBP and PBLI, two themes emerged. First, team-based communication or a desire for interactions to make better connections between attendings and the care team. Second was role on rounds, or that leadership and resident roles could be improved during rounds. Lastly, under Interpersonal Communication and Professionalism (ICS&P), a single emergent theme was a desire for more feedback to aid resident development.

Table 5.

Emergent Themes on Low-Performing Faculty Educators as Assessed by Internal Medicine Residents

| Low-performing faculty educators (third tertile) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emergent themes | Description | Exemplars |

| Patient care and medical knowledge | ||

| Inefficiency on rounds | Ineffectiveness during rounds causes stress with downstream effects such as not rounding on some patients or missing conferences so learners could catch up with their work |

“There were days that sometimes rounds took too long (or we spent too much time in one person's room) and therefore we would not get a chance to round on all the patients that I wanted to prior to multi-disciplinary rounds.” [Attending #14] “Rounding was at times inefficient and stressful to me if we were rounding past noon.” [Attending #11] “Though efficiency was a goal of our time on service, it would be helpful to work on streamlining rounds early on to ensure sufficient time is had to complete our work after rounds in a timely manner.” [Attending #21] |

| Systems-based practice and practice-based learning and improvement | ||

| Team-based communication | Desire for interactions that make better connections between attendings and the care team |

• “Occasionally places orders without giving a heads-up to the team.” [Attending #3] • “At times, I felt there were moments where she could have used her knowledge to create the space for learners to figure out a differential or a management strategy, rather than telling the team what she was thinking.” [Attending #1] • “I would have liked if he had closed the loop on communication regarding his plans. It was not always clear to me what the plans were coming out of the room. I appreciate face to face communication with regard to such matters vs. in-chart communication.” [Attending #12] |

| Role on rounds | Perceptions that leadership roles and residents roles could be improved during rounds |

• “Allow the resident to explain the "plan of the day" to patients, as some attendings let the resident take first pass, and step in only when it is necessary or unclear. This will allow us to have more experience, and benefit from any feedback Dr. XXX may have towards perfecting this skill.” [Attending #10] • “Would have appreciated initiative to provide additional guidance regarding how to help my team perform more effectively, at the mid-way point when we were having some struggles.” [Attending #5] |

| Interpersonal communication and professionalism | ||

| Desired more feedback | Residents’ commitment to improve is high, and they desired actionable feedback |

• “Wish I could have received a bit more feedback from her.” [Attending #12] • “Would have appreciated more frequent feedback personally.” [Attending #8] • “More direct 1:1 feedback.” [Attending #7] |

DISCUSSION

Our study is novel in that we reviewed 724 individual attending physician assessments using a mixed methods approach to characterize high- and low-quality physician attending educators. Interestingly, the majority of attendings scored across all three tertiles, with no one attending scoring solely in the top or bottom tertile. The average assessment scores for ACGME core competencies were relatively narrow, with ratings ranging from 4.10 to 4.59 on a scale of 1 to 5. The observed narrow range of average scores may be attributed to several factors. It is possible there was a social response bias with the attending participants in our study, leading to consistently positive assessment. Resident evaluators may have had preconceived positive expectations about attending physicians, influencing their evaluations. This could result from previous experiences, reputation, or general perceptions. The design of the evaluation instrument itself may not have been sensitive enough to capture subtle variations in attending performance. We plan on continuing to refine and validate our evaluation tools to ensure they accurately reflect the diverse aspects of performance. Residents may also feel pressure to provide positive evaluations to avoid potential conflicts or repercussions, leading to artificially high scores. Our quantitative data demonstrated that interpersonal communication skills are rated more highly, while system-based practice is rated lower for attendings. This may be due to confusion about SBP and/or may represent that communication skills are easier to evaluate or more important to residents.

Qualitative data suggested that high-quality attending physicians allow residents autonomy to lead the team. This is incredibly important for confidence building and can be challenging to balance with being supportive and approachable. Other qualities included having a calming presence with the team and patients, and empathy during sensitive discussions. Existing literature on physician role modeling found that “teacher/supervisor” role modeling was closely associated with professional attitudes towards residents, providing feedback, and affecting the learning climate.16 We found that high-quality educators had an impressive knowledge base, and were willing to share medical and practical knowledge, which was especially well-received when it was engaging. Valuable practical knowledge included navigating hospital systems, optimizing care resources, and communicating effectively and professionally with the multidisciplinary care team. Providing feedback was also a strength among the high-performing attendings. Residents expressed appreciation for frequent check-ins followed by actionable feedback tailored to the learner with positive reinforcement when appropriate.

A number of recurring themes emerged among faculty educators with lower ratings. Inefficiency was one, with evaluations noting that prolonged rounding or protracted teaching points led to delays in patient care that created stress for residents attending to other commitments. Poor time management was mentioned in prior studies examining narrative feedback of clinical teachers.17 Communication was another emergent theme, especially regarding patient care, with several residents voicing a preference for direct communication, as opposed to attendings placing orders without notifying the team or communicating through the chart. Given that residents appreciate autonomy, it is not surprising that some lower scoring attendings would deprive learners the opportunity to come up with a differential diagnosis or communicate daily plans to patients. Attendings who did not seem invested or did not provide assistance when the team was struggling were also rated lower. A desire for more frequent and direct feedback on performance was also voiced, showing that while this was a strength for some faculty, others are underperformers. Unfortunately, it is unclear how best to provide frequent feedback, a finding that has also been reported elsewhere.17, 18

While resident perceptions of the quality of attending physician educators are valuable, several caveats exist when interpreting assessment data. Assessments typically contain personal or social bias that influence the review process. Though the resident responses were anonymous, complicated power dynamics of rating a supervisor may limit negative feedback for fear it will affect future interactions with attendings. Similarly, implicit biases towards gender, race, and age may influence assessment language and scoring outcomes. Residents often lack training or experience on how to provide high-quality assessments and/or may be completing them weeks to months after interacting with attendings, limiting their depth and scope. Thus, resident assessments must be interpreted with caution and used with other feedback sources to fully determine attending educator quality.

Utilizing a mixed-methods approach allowed for both qualitative and quantitative analyses and provided breadth and depth to this study. The positive deviance approach to determine the highest- and lowest-rated attendings provided a framework for core ACGME competencies that can inform future educational strategies for low performers to improve.

This study was conducted at a single institution with an institution-specific evaluation form, which may limit generalizability. However, over 700 assessments were included in the analysis collected over six years, and the assessment tool was found to be highly reliable as a measure of the ACGME core competencies (Cronbach alpha 0.92).

Future research should explore how to improve evaluative processes and clinical teaching effectiveness. More robust evaluative processes would allow for objective evaluations of attendings across programs and institutions. Future research on multi-source feedback, including peer evaluations, learning specialist reviews, patient comments, and self-assessments, could identify new areas for improvement. Research should also explore factors influencing attending physicians’ receptiveness to feedback and strategies to promote a culture of continuous improvement. As technology advances, opportunities will emerge to develop innovative tools, including simulation-based assessments, machine learning algorithms, and real-time feedback tools.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

None

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Faculty Survey/Common Program Requirements Crosswalk. (https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programresources/faculty-survey-common-program-requirements-crosswalk.pdf). Accessed 17 Mar 2023.

- 2.Goldszmidt M, Faden L, Dornan T, van Merrienboer J, Bordage G, Lingard L. Attending physician variability: a model of four supervisory styles. Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1541–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant AL, Torti J, Goldszmidt M. "Influential" Intraoperative Educators and Variability of Teaching Styles. J Surg Educ. 2023;80(2):276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthiesen M, Kelly MS, Dzara K, Begin AS. Medical residents and attending physicians' perceptions of feedback and teaching in the United States: a qualitative study. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2022;19:9. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2022.19.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crockett C, Joshi C, Rosenbaum M, Suneja M. Learning to drive: resident physicians' perceptions of how attending physicians promote and undermine autonomy. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):293. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheepers RA, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. In the eyes of residents good supervisors need to be more than engaged physicians: the relevance of teacher work engagement in residency training. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2015;20(2):441–55. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9538-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident Wellness Matters: Optimizing Resident Education and Wellness Through the Learning Environment. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1246–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffith CH, 3rd, Georgesen JC, Wilson JF. Specialty choices of students who actually have choices: the influence of excellent clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2000;75(3):278–82. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200003000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eno C CR, Stewart NH, Lim J, Westerman ME, Holmboe ES, Edgar L. ACGME Milestones Guidebook for Residents and Fellows. (https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pdfs/milestones/milestonesguidebookforresidentsfellows.pdf ). Accessed 17 Mar 2023.

- 10.Guerrero LR, Baillie S, Wimmers P, Parker N. Educational Experiences Residents Perceive As Most Helpful for the Acquisition of the ACGME Competencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):176–83. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00058.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee FY, Yang YY, Hsu HC, et al. Clinical instructors' perception of a faculty development programme promoting postgraduate year-1 (PGY1) residents' ACGME six core competencies: a 2-year study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000200. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litzelman DK, Stratos GA, Marriott DJ, Skeff KM. Factorial validation of a widely disseminated educational framework for evaluating clinical teachers. Acad Med. 1998;73(6):688–95. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199806000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MedHub. Minneapolis, MN.

- 14.Rose AJ, McCullough MB. A Practical Guide to Using the Positive Deviance Method in Health Services Research. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(3):1207–1222. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt2014.

- 16.Boerebach BC, Lombarts KM, Keijzer C, Heineman MJ, Arah OA. The teacher, the physician and the person: how faculty's teaching performance influences their role modelling. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers KA, Zibrowski EM, Lingard L. A mixed-methods analysis of residents' written comments regarding their clinical supervisors. Acad Med. 2011;86(10 Suppl):S21–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822a6fd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Leeuw RM, Schipper MP, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. Residents' narrative feedback on teaching performance of clinical teachers: analysis of the content and phrasing of suggestions for improvement. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92(1085):145–51. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-133214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]