Abstract

Background

Sexual assault and/or sexual harassment during military service (military sexual trauma (MST)) can have medical and mental health consequences. Most MST research has focused on reproductive-aged women, and little is known about the long-term impact of MST on menopause and aging-related health.

Objective

Examine associations of MST with menopause and mental health outcomes in midlife women Veterans.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Participants

Women Veterans aged 45–64 enrolled in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare in Northern California between March 2019 and May 2020.

Main Measures

Standardized VA screening questions assessed MST exposure. Structured-item questionnaires assessed vasomotor symptoms (VMS), vaginal symptoms, sleep difficulty, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Multivariable logistic regression analyses examined associations between MST and outcomes based on clinically relevant menopause and mental health symptom thresholds.

Key Results

Of 232 participants (age = 55.95 ± 5.13), 73% reported MST, 66% reported VMS, 75% reported vaginal symptoms, 36% met criteria for moderate-to-severe insomnia, and almost half had clinically significant mental health symptoms (33% depressive symptoms, 49% anxiety, 27% probable PTSD). In multivariable analyses adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, education, body mass index, and menopause status, MST was associated with the presence of VMS (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.26–4.72), vaginal symptoms (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.08–4.62), clinically significant depressive symptoms (OR 3.21, 95% CI 1.45–7.10), anxiety (OR 4.78, 95% CI 2.25–10.17), and probable PTSD (OR 6.74, 95% CI 2.27–19.99). Results did not differ when military sexual assault and harassment were disaggregated, except that military sexual assault was additionally associated with moderate-to-severe insomnia (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.72–5.88).

Conclusions

Exposure to MST is common among midlife women Veterans and shows strong and independent associations with clinically significant menopause and mental health symptoms. Findings highlight the importance of trauma-informed approaches to care that acknowledge the role of MST on Veteran women’s health across the lifespan.

KEY WORDS: military sexual trauma, menopause, Veteran, women’s mental health

INTRODUCTION

Military sexual trauma (MST) is a pervasive problem defined by the Department of Veterans Affairs as any incident of sexual assault or sexual harassment occurring during military service (US Code, Title 38, Code 1720D). Based on studies of universal screening for MST in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MST disproportionally affects women, with a recent meta-analysis of VHA screening results showing that 38% of women and 4% of men Veterans report experiences of MST.1 MST is likely even more common than is reported using VHA screening methods; up to 70% of women Veterans endorse past MST experiences in anonymous research surveys.2

As with other forms of sexual trauma, MST has been associated with a wide range of medical concerns, including pain conditions, hypertension, obesity, chronic pulmonary disease, and liver disease.3, 4 MST history has also been linked to mental health conditions, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, sleep disorders, eating disorders, and substance use disorders.5–8 Studies examining the impact of MST history on reproductive and sexual health have shown that MST is associated with a higher incidence of sexual dysfunction disorders, infertility, sexually transmitted infections, perinatal depression, sexual pain, and sexual dissatisfaction.9–14 These studies have largely focused on younger, reproductive-age women Veterans from recent service eras5, 6, 15–17 despite a growing body of evidence highlighting ongoing consequences of sexual violence for women across the lifespan.4, 18, 19

Midlife and older women have unique health risk factors that may affect the influence of trauma exposure on health and well-being. This includes the menopause transition, a period identified as a persistent gap necessitating further study in a recently published white paper identifying VA reproductive health research priorities.20 In and after the menopause transition, women are at risk for common menopause and aging-related symptoms, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal symptoms, sleep difficulty, and the onset or exacerbation of mental health concerns. Limited data from non-military settings indicates that sexual trauma can make women more susceptible to menopause symptoms, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal symptoms, and difficulty sleeping.21, 22 While MST has been shown to be associated with mental health outcomes, this has not been specifically examined among women in midlife, a period of heightened vulnerability for mental health.

The current study aims to provide new insight into the association of MST with menopause and mental health–related symptoms among women Veterans in midlife. We hypothesized that among midlife women Veterans, a history of MST would be associated with menopause symptoms and clinically significant mental health symptoms independent of known demographic and clinical risk factors.

METHODS

Study Population

Data were drawn from the Midlife Women Veterans Health Study, a cross-sectional, observational study of 232 midlife women Veterans’ health conducted between March 2019 and May 2020. Study procedures have been previously described.2 Briefly, eligible participants were cisgender women Veterans, 45–64 years old at the time of recruitment, with at least one clinical encounter in one of three VA Health Care Systems in Northern California in the previous 2 years, and no current diagnoses of dementia or active psychosis. All participants provided written informed consent and completed web- or mail-based survey questionnaires, according to procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco VA Health Care System Research and Development Committee.

Military Sexual Trauma

History of MST was assessed in the study survey using standard screening questions used by the VA: (1) “While you were in the military, did you receive uninvited and unwanted sexual attention, such as touching, cornering, pressure for sexual favors, or verbal remarks?” and (2) “Did someone ever use force or the threat of force to have sexual contact with you against your will?” MST was categorized both as defined by the VA (endorsing harassment and/or assault) and as distinct categories of military sexual harassment or military sexual assault.1

Mental Health and Menopause Outcomes

Menopause status was defined by self-reported menstrual bleeding patterns; women were categorized as postmenopausal if they had no menstrual cycle in the previous 12 months, whether owing to natural cessation or hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy. All mental health and menopause symptom outcomes were assessed using structured-item questionnaire measures and categorized as binary outcomes based on clinically relevant cutoffs. Menopause symptoms were assessed using structured items adapted from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a large multiethnic observational study of midlife women’s health. Participants were considered to have vasomotor symptoms if they reported experiencing hot flashes and/or night sweats in the previous 2 weeks,23 and to have vaginal symptoms if they reported experiencing vaginal irritation, vaginal dryness, and/or pain with sexual activity in the previous 2 weeks. Depressive symptoms were measured using the validated Patient Health Questionaire-9 (PHQ-9), with clinically significant symptoms of depression defined as a score of 10 or above.24 Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire, with clinically significant symptoms of anxiety defined as a score of 8 or above.25 PTSD symptoms were assessed using the validated Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5), in which a score of 33 or above indicates high symptom burden and probable PTSD in the past month.24 Sleep difficulty was assessed with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), which has been validated as a reliable measure of insomnia symptom severity, with scores of 15 or higher indicating moderate-severe clinical insomnia.26

Demographic Variables

Participants self-reported their age, race, ethnicity, and educational attainment. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported height and weight (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe characteristics of participants, stratified by MST screen response. Chi-square tests were performed to compare the distribution of categorical variables by MST status, while independent sample t-tests were performed to compare continuous variables. Due to small cell sizes, race was collapsed into White vs. non-White, and ethnicity was collapsed into Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic for analyses. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to examine associations between MST and clinically relevant mood symptoms and menopause symptoms (i.e., binary outcomes), adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, education, menopause status, and BMI, as covariates chosen a priori due to established associations with examined outcomes.27–32 Consistent with past examinations of trauma exposure on health outcomes, sensitivity analyses were conducted for all models further adjusting for probable posttraumatic stress disorder. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. IBM Corp. Released 2021).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Population

Of the 247 eligible women Veterans who were sent the study survey, 232 (94%) returned the survey and were included in our sample (mean age 56.0 ± 5.1 years). Overall, the sample was primarily White (73%) and postmenopausal (82%). No significant differences in baseline demographics of participants with and without a history of MST were detected (Table 1). MST was reported by 73% of participants, including 167 (72%) reporting military sexual harassment and 106 (46%) reporting military sexual assault. Current menopause symptoms were common; 66% of participants reported vasomotor symptoms (VMS), 75% reported vaginal symptoms, and 36% met criteria for moderate-to-severe insomnia. Almost half reported current clinically significant mental health symptoms (33% depressive symptoms, 49% anxiety, 27% probable PTSD).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Overall and by Military Sexual Trauma Category

| Characteristic | Total (n = 232) |

Military sexual trauma (n = 169, 73%) |

No military sexual trauma (n = 60, 26%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 56.0 (5.1) | 55.6 (5.0) | 56.7 (5.56) |

| BMI (mean, SD) | 29.71 (7.03) | 29.3 (7.2) | 30.9 (6.5) |

| Education | |||

| Some college or less | 119 (51.3) | 91 (53.8) | 28 (46.7) |

| College degree | 37 (15.9) | 28 (16.6) | 7 (11.7) |

| Some graduate school or graduate degree | 76 (32.8) | 50 (29.6) | 25 (41.7) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latina | 24 (10.3) | 18 (10.7) | 6 (10.2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latina | 207 (89.2) | 151 (89.9) | 53 (89.8) |

| Race* | |||

| White | 169 (72.8) | 125 (74.0) | 41 (68.3) |

| Black or African American | 24 (10.3) | 13 (7.7) | 11 (18.3) |

| Asian | 9 (3.9) | 5 (3.0) | 4 (6.7) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 4 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiracial/not otherwise specified | 28 (12.1) | 24 (14.2) | 4 (6.7) |

| Menopause status: postmenopausal | 191 (82.3) | 136 (81.0) | 52 (86.7) |

Missing data: MST (3), MST harassment (3), MST assault (4), BMI (6), ethnicity (1), vaginal symptoms (19), PHQ (1), GAD (4), PCL (2). All comparisons non-significant at p > .05. *Categories collapsed in multivariable analyses due to small cell counts

Associations Between MST, Mental Health, and Menopause Symptom Outcomes

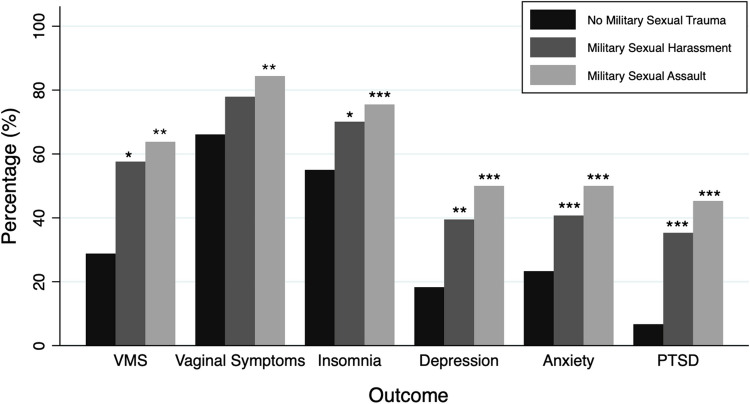

In bivariate analyses, participants with histories of military sexual harassment and military sexual assault had a higher prevalence of VMS, insomnia, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and probable PTSD (Fig. 1). Vaginal symptoms were more common in participants with a history of military sexual assault but not military sexual harassment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Menopause and mental health outcomes by MST category. Bar graph depicting percentage of menopause and mental health outcomes reported by participants with no prior exposure to military sexual trauma (MST) (n = 60), past exposure to military sexual harassment (n = 167), and past exposure to military sexual assault (n = 106). Presence of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) was defined as having experienced hot flashes and/or night sweats in the previous 2 weeks. Presence of vaginal symptoms was defined as having experienced vaginal irritation, vaginal dryness, and/or pain with sexual activity in the previous 2 weeks. Presence of depression was defined as PHQ-9 ≥ 10; presence of anxiety was defined as GAD-7 ≥ 8; presence of probable PTSD was defined as PCL-5 ≥ 33. *p < .05, ** < .01, *** < .001, with reference to no MST.

In multivariable analyses adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, education, BMI, and menopause status, MST was associated with over two-fold odds of having VMS (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.26–4.72) and vaginal symptoms (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.08–4.62), independent of sociodemographic variables, BMI, and menopause status (Table 2). History of MST was independently associated with current, clinically significant depressive symptoms (OR 3.21, 95% CI 1.45–7.10), anxiety (OR 4.78, 95% CI 2.25–10.17), and probable PTSD (OR 6.74, 95% CI 2.27–19.99).

Table 2.

Associations of MST with Mental Health and Menopause Symptoms

| Military sexual trauma (n = 169, 73%) |

Military sexual harassment (n = 167, 72%) |

Military sexual assault (n = 106, 46%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Any vasomotor symptoms | 2.44 (1.26–4.72) | 2.50 (1.30–4.80) | 2.76 (1.50–5.09) |

| Any vaginal symptoms | 2.23 (1.08–4.62) | 2.14 (1.04–4.40) | 2.99 (1.46–6.11) |

| Insomnia (ISI ≥ 15) | 1.81 (0.88–3.69) | 1.94 (0.96–3.95) | 3.18 (1.72–5.88) |

| Depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) | 3.21 (1.45–7.10) | 3.32 (1.50–7.32) | 5.24 (2.67–10.29) |

| Anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 8) | 4.78 (2.25–10.17) | 4.33 (2.08–9.00) | 3.72 (2.01–6.90) |

| Probable PTSD (PCL-5 ≥ 33) | 6.74 (2.27–19.99) | 6.99 (2.36–20.70) | 6.48 (3.14–13.34) |

All models adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, education, BMI, and menopause status. PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Item; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index. Odds ratios are relative to reference of no military sexual trauma

Results were similar when military sexual harassment was examined separately in disaggregated analyses. However, military sexual assault was additionally associated with clinically significant insomnia (OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.72–5.88) (Table 2). Results were equivalent in sensitivity analyses adjusting for probable posttraumatic stress disorder (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In a sample of midlife women Veterans, we found new evidence supporting strong and independent associations between MST and menopause symptoms, including over two-fold odds of both VMS and vaginal symptoms. VMS and vaginal symptoms are reported by over half of women during the menopause transition in community samples and may last upwards of 10 years with significant and prolonged negative impact on health and quality of life.27, 33–36 Similar to a prior study that reported associations between intimate partner violence and menopause symptoms in a community-based sample, the present study emphasizes the association between traumatic exposure and menopause symptoms in midlife women.21

While this cross-sectional study cannot establish causal relationships between MST and menopause symptoms, several potential mechanisms may explain how a history of sexual trauma could precipitate worse symptoms at the menopause transition. Biologically, alterations in the stress response systems caused by a history of trauma are linked to the hormonal and physiological changes in a woman’s reproductive lifespan.28 This may increase biological susceptibility during the hormonal fluctuations during and after the menopause transition, contributing to autonomic dysregulation and heightened symptom sensitivity that may influence menopause symptom experience. Behavioral factors may also put women with a history of sexual trauma at increased risk for these symptoms in and after the menopause transition. For example, health behaviors associated with sexual trauma, including interpersonal avoidance, relational conflict, emotional discomfort with intimacy, smoking, and substance use, may predispose women to sleep disturbances, vaginal symptoms, and mental health sequelae, and may also affect a woman’s interaction with the healthcare system.37 Given the known impact of menopause symptoms on quality of life, productivity, healthcare utilization, and economic outcomes, as well as our obligation to care for women across the reproductive spectrum, it is especially important for our healthcare systems to be able to support women with a history of sexual trauma during the menopause transition.38, 39

Our study also demonstrates strong and independent associations between MST and mental health symptoms in midlife women. Specifically, relative to those who had not experienced MST, participants endorsing MST had an over three-fold greater odds of depressive symptoms, four-fold greater odds of anxiety, and six-fold greater odds of probable PTSD. Additionally, military sexual assault was associated with over three-fold greater odds of clinically significant insomnia. These findings are consistent with patterns observed in other studies of Veterans showing that MST is associated with greater risks of depression, anxiety, insomnia, suicidal ideation, PTSD, sleep disorders, somatic symptoms, pain conditions, and other medical conditions.3, 4, 17, 18, 36, 40 Results are also consistent with a prior VA administrative data study examining MST and medical and psychiatric diagnoses among women Veterans aged 55 and older, which also reported associations between VA screening–derived MST and mental health disorders.18 However, the current study is unique in examining these associations specifically in and after the menopause transition, a known period of vulnerability for depression and anxiety.41–43 Less is known about the onset or exacerbation of posttraumatic stress in the menopause transition, and these findings highlight the importance of this area for further inquiry among women Veterans given the high rates of trauma exposure and PTSD across the lifespan in this population. This study is also unique in using direct questioning of women about MST, mental health symptoms, and menopause symptoms, rather than relying on administrative or medical record documentation of these often-underdiagnosed problems.

Given the association between MST history and menopause symptoms, the care of women facing the menopause transition may be enhanced by trauma-informed care (TIC). TIC is a universal approach to patient grounded in four assumptions (“4 R’s”): realizing the widespread impact of trauma, recognizing of the signs and symptoms of trauma, responding with evidence-based trauma practices, and actively resisting re-traumatization.44 Using the principles of TIC, we suggest that providers caring for women at the menopause transition employ a “universal precaution approach” that assumes trauma may be present and intentionally seeks to promote safety, trust, transparency, and support to patients. We suggest using patient-centered communication and decision-making that promotes patient autonomy, trauma-sensitive evaluations that recognizes the discomfort many feel with disclosure and physical examination, and interprofessional collaboration with referrals for psychological and trauma-specific interventions when appropriate. Educating patients on the connection between trauma and menopause symptoms may also be helpful in some cases, though this has not been specifically studied.

There are several limitations to this study. As the study design is cross-sectional, the temporal order of MST and the onset of mental health comorbidities cannot be discerned, and we can only confirm association and not causality. We did not examine independent or compounding effects of other forms of interpersonal trauma exposure, which may influence the relationship between MST and menopause symptoms and mental health comorbidity. This is notable, as cumulative risk models indicate that repeated traumatic life experiences have additive effects on the stress response system and increase the risk of negative outcomes.45, 46 Recent population-based studies have indicated that Veterans are not only at elevated risk of trauma from MST victimization and potential warfare exposure, but also have higher rates of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) than civilian populations.47, 48 Veterans, including our study population, are therefore at particularly high risk for experiencing the cumulative and complex effects of multiple traumatic experiences. It will be important for larger studies to collect and analyze more detailed data on the type, number, chronicity, and duration of traumatic exposures to better understand the dimensional effects on menopause symptoms and mental health outcomes.

Additional limitations include that our study did not have access to detailed data on the chronicity and duration of mental health conditions and menopause symptoms, as well as the elapsed time since onset of perimenopause or menopause. Incorporating this information in future research would allow for a more refined analysis of how these factors interact temporally and moderate patient outcomes. There is also crossover between some of the menopause and mental health symptoms, which our study design is unable to distinguish; for instance, night sweats and sleep difficulties can be caused by both menopause and PTSD. Additionally, we did not have access to substance use patterns in our study sample, which may confound results given potential impacts on menopause and mental health symptoms. Lastly, our study results may not be generalizable to other populations given that our sample was primarily White and included only women Veterans in Northern California VA healthcare. Additionally, use of VA care within the past 2 years was an inclusion criterion, excluding our ability to account for women who were not enrolled or using VA healthcare, a notable limitation given the known impact that trauma can have on one’s comfort and use of the healthcare system.17

In summary, in this sample of midlife women Veterans, nearly three-quarters of women reported a history of MST, and those reporting MST were more likely to have menopause symptoms and mental health comorbidity. As MST is underreported in VA settings and rarely assessed in community settings, these findings suggest that MST may represent an independent and underrecognized risk factor for both menopause symptoms and mental health disorders during the menopause transition, while also contributing known challenges to seeking and receiving gender-sensitive care.2, 49 Our findings also add to a growing body of evidence that traumatic exposures, including MST, may have long-term implications for women’s reproductive health and mental health. Therefore, our study highlights the value of integrating trauma-informed care principles, including safety, collaboration, and empowerment, into the care of women across the lifespan, especially women at risk of military trauma.

Funding

This research was supported in part by VA Health Services Research & Career Development Award IK2 HX002402 (CJG), National Institute of Aging K24AG068601 (AJH), and VA Research Career Scientist Award IK6 CX002386 (ALB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Gibson has served as an unpaid consultant to Astellas Pharmaceuticals for projects unrelated to the current manuscript. The authors have no other disclosures to report.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: Preliminary findings from this project were presented as part of a symposium. “Trauma and Health among Midlife and Aging Women,” at the American Psychosomatic Society 2022 Annual Meeting.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilson LC. The Prevalence of Military Sexual Trauma: a Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2018;19(5):584–597. doi: 10.1177/1524838016683459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hargrave AS, Maguen S, Inslicht SS, et al. Veterans Health Administration Screening for Military Sexual Trauma May Not Capture Over Half of Cases Among Midlife Women Veterans. Women’s Health Issues. 2022;32(5):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimerling R, Gima K, Smith MW, Street A, Frayne S. The Veterans Health Administration and Military Sexual Trauma. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2160–2166. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, et al. Medical Profile of Women Veterans Administration Outpatients Who Report a History of Sexual Assault Occurring While in the Military. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8(6):835–845. doi: 10.1089/152460999319156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maguen S, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Madden E. Gender Differences in Traumatic Experiences and Mental Health in Active Duty Soldiers Redeployed from Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(3):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimerling R, Street AE, Pavao J, et al. Military-Related Sexual Trauma Among Veterans Health Administration Patients Returning from Afghanistan and Iraq. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1409–1412. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein LA, Dinh J, Donalson R, Hebenstreit CL, Maguen S. Impact of Military Trauma Exposures on Posttraumatic Stress and Depression in Female Veterans. Psychiatry Research. 2017;249:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blais RK, Brignone E, Maguen S, Carter ME, Fargo JD, Gundlapalli AV. Military Sexual Trauma is associated with post-deployment eating disorders among Afghanistan and Iraq veterans: BLAIS et al. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(7):808-816. 10.1002/eat.22705 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Cohen BE, Maguen S, Bertenthal D, Shi Y, Jacoby V, Seal KH. Reproductive and Other Health Outcomes in Iraq and Afghanistan Women Veterans Using VA Health Care: Association with Mental Health Diagnoses. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(5):e461–471. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pulverman CS, Christy AY, Kelly UA. Military Sexual Trauma and Sexual Health in Women Veterans: a Systematic Review. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(3):393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulverman CS, Creech SK. The Impact of Sexual Trauma on the Sexual Health of Women Veterans: a Comprehensive Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021;22(4):656–671. doi: 10.1177/1524838019870912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan GL, Mengeling MA, Booth BM, Torner JC, Syrop CH, Sadler AG. Voluntary and Involuntary Childlessness in Female Veterans: Associations with Sexual Assault. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(2):539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMauro J, Renshaw KD, Blais RK. Sexual vs. Non-sexual Trauma, Sexual Satisfaction and Function, and Mental Health in Female Veterans. J Trauma Dissociation. 2018;19(4):403–416. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2018.1451975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turchik JA, Pavao J, Nazarian D, Iqbal S, McLean C, Kimerling R. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexual Dysfunctions Among Newly Returned Veterans With and Without Military Sexual Trauma. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2012;24(1):45–59. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2011.639592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavao J, Turchik JA, Hyun JK, et al. Military Sexual Trauma Among Homeless Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(Suppl 2):S536–541. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2341-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattocks KM, Sadler A, Yano EM, et al. Sexual Victimization, Health Status, and VA Healthcare Utilization Among Lesbian and Bisexual OEF/OIF Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(Suppl 2):S604–608. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2357-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calhoun PS, Schry AR, Dennis PA, et al. The Association Between Military Sexual Trauma and Use of VA and Non-VA Health Care Services Among Female Veterans With Military Service in Iraq or Afghanistan. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(15):2439–2464. doi: 10.1177/0886260515625909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson CJ, Maguen S, Xia F, Barnes DE, Peltz CB, Yaffe K. Military Sexual Trauma in Older Women Veterans: Prevalence and Comorbidities. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):207–213. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05342-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook JM, Dinnen S, O’Donnell C. Older Women Survivors of Physical and Sexual Violence: a Systematic Review of the Quantitative Literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(7):1075–1081. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon JG, Rodriguez A, Yano EM, et al. Research priorities to support Women Veterans’ Reproductive Health and health care within a learning health care system. Women’s Health Issues. Published online January 2023:S1049386722001797. 10.1016/j.whi.2022.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gibson CJ, Huang AJ, McCaw B, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK. Associations of Intimate Partner Violence, Sexual Assault, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With Menopause Symptoms Among Midlife and Older Women. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):80–87. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tracy EE, Speakman E. Intimate Partner Violence: Not Just a Concern of the Reproductive Ages. Menopause. 2012;19(1):3–5. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318239c985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of Demographic and Lifestyle Factors to Symptoms in a Multi-racial/Ethnic Population of Women 40–55 Years of Age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(5):463–473. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an Outcome Measure for Insomnia Research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green R, Santoro N. Menopausal Symptoms and Ethnicity: the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2009;5(2):127–133. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Im EO, Chang SJ, Chee E, Chee W. The Relationships of Multiple Factors to Menopausal Symptoms in Different Racial/Ethnic Groups of Midlife Women: the Structural Equation Modeling. Women & Health. 2019;59(2):196–212. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2018.1450321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minkin MJ, Reiter S, Maamari R. Prevalence of Postmenopausal Symptoms in North America and Europe. Menopause. 2015;22(11):1231–1238. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santoro N, Komi J. Prevalence and Impact of Vaginal Symptoms Among Postmenopausal Women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6(8):2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soares CN. Mood Disorders in Midlife Women: Understanding the Critical Window and Its Clinical Implications. Menopause. 2014;21(2):198–206. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, et al. Beyond Frequency: Who Is Most Bothered by Vasomotor Symptoms? Menopause. 2008;15(5):841–847. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms Over the Menopause Transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):531. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods NF, Mitchell ES. Symptoms During the Perimenopause: Prevalence, Severity, Trajectory, and Significance in Women’s Lives. The American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118(12):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, et al. Longitudinal Analysis of the Association Between Vasomotor Symptoms and Race/Ethnicity Across the Menopausal Transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein LA, Jakubowski KP, Huang AJ, et al. Lifetime History of Interpersonal Partner Violence Is Associated with Insomnia Among Midlife Women Veterans. Menopause. 2023;30(4):370–375. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell SB, Renshaw KD. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Relationship Functioning: a Comprehensive Review and Organizational Framework. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;65:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Assaf AR, Bushmakin AG, Joyce N, Louie MJ, Flores M, Moffatt M. The Relative Burden of Menopausal and Postmenopausal Symptoms versus Other Major Conditions: a Retrospective Analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Data. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2017;10(6):311–321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whiteley J, da Costa DiBonaventura M, Wagner JS, Alvir J, Shah S. The Impact of Menopausal Symptoms on Quality of Life, Productivity, and Economic Outcomes. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(11):983–990. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Street AE, Stafford J, Mahan CM, Hendricks A. Sexual Harassment and Assault Experienced by Reservists During Military Service: Prevalence and Health Correlates. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(3):409–419. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.06.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y, et al. Does Risk for Anxiety Increase During the Menopausal Transition? Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2013;20(5):488–495. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182730599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen LS, Soares CN, Vitonis AF, Otto MW, Harlow BL. Risk for New Onset of Depression During the Menopausal Transition: the Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(4):385. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bromberger JT, Epperson CN. Depression During and After the Perimenopause: Impact of Hormones, Genetics, and Environmental Determinants of Disease. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(4):663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No (SMA) 14–4884, Rockville, MD (2014) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrationhttps://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf (https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf).

- 45.Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative Risk and Child Development. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139(6):1342–1396. doi: 10.1037/a0031808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doucette CE, Morgan NR, Aronson KR, Bleser JA, McCarthy KJ, Perkins DF. The Effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Warfare Exposure on Military Sexual Trauma Among Veterans. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(3–4):3777–3805. doi: 10.1177/08862605221109494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blosnich JR, Dichter ME, Cerulli C, Batten SV, Bossarte RM. Disparities in Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Individuals With a History of Military Service. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1041. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aronson KR, Perkins DF, Morgan NR, et al. The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Combat Exposure on Mental Health Conditions Among New Post-9/11 Veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(7):698–706. doi: 10.1037/tra0000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yano EM, Haskell S, Hayes P. Delivery of Gender-Sensitive Comprehensive Primary Care to Women Veterans: Implications for VA Patient Aligned Care Teams. J GEN INTERN MED. 2014;29(S2):703–707. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2699-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]