Abstract

The Rev protein of equine infectious anemia virus (ERev) exports unspliced and partially spliced viral RNAs from the nucleus. Like several cellular proteins, ERev regulates its own mRNA by mediating an alternative splicing event. To determine the requirements for these functions, we have identified ERev mutants that affect RNA export or both export and alternative splicing. Mutants were further characterized for subcellular localization, nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling, and multimerization. None of the nuclear export signal (NES) mutants are defective for alternative splicing. Furthermore, the NES of ERev is similar in composition but distinct in spacing from other leucine-rich NESs. Basic residues at the C terminus of ERev are involved in nuclear localization, and disruption of the C-terminal residues affects both functions of ERev. ERev forms multimers, and no mutation disrupts this activity. In two mutants with substitutions of charged residues in the middle of ERev, RNA export is affected. One of these mutants is also defective for ERev-mediated alternative splicing but is identical to wild-type ERev in its localization, shuttling, and multimerization. Together, these results demonstrate that the two functions of ERev both require nuclear import and at least one other common activity, but RNA export can be separated from alternative splicing based on its requirement for a functional NES.

The Rev-like proteins of the lentivirus and complex oncovirus subfamilies transport unspliced and partially spliced viral transcripts from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (10, 12, 14). These intron-containing transcripts code for structural and enzymatic proteins and, in the absence of a Rev-like protein, are spliced or degraded (35). Characterization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Rev protein has shown that it contains several essential domains. An N-terminal, RNA binding domain interacts specifically with a Rev-responsive element (RRE), an RNA secondary structure located in unspliced and partially spliced transcripts (22, 26, 31, 32, 34, 36, 38, 46, 48, 57). A multimerization domain at the N terminus and a nuclear localization signal which overlaps the RNA binding domain have also been identified and are required for function (25, 33, 34, 47, 52, 57). The Rev-bound transcripts are coupled to a cellular export pathway via a C-terminal, leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) (3, 13, 28, 42, 51). The Rev-like NESs interact with CRM1 or exportin 1, and this interaction is disrupted by the antibiotic leptomycin B (LMB) (15, 19, 49, 53, 56).

Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) Rev (ERev) is distinct from the other Rev-like proteins. In addition to mediating the export of unspliced and partially spliced RNAs, ERev mediates an alternative splicing event (40) that is made possible by the unique genomic organization of EIAV (Fig. 1A). In EIAV, Tat (ETat) and ERev are each expressed from two exons but, unlike in the other complex retroviruses, these exons do not overlap. Instead, the proteins are translated from a four-exon, bicistronic transcript (1, 4, 45, 54). ETat is encoded by exons 1 and 2 and utilizes a leaky CUG initiation codon that ensures ribosome initiation at the downstream AUG of ERev, encoded by exons 3 and 4 (4, 7). The ETat-ERev transcript is fully spliced and therefore should not require ERev for export. In the presence of ERev, however, exon 3 is often excluded. The alternatively spliced transcript is comprised of three exons, is fully spliced, and expresses ETat but not ERev.

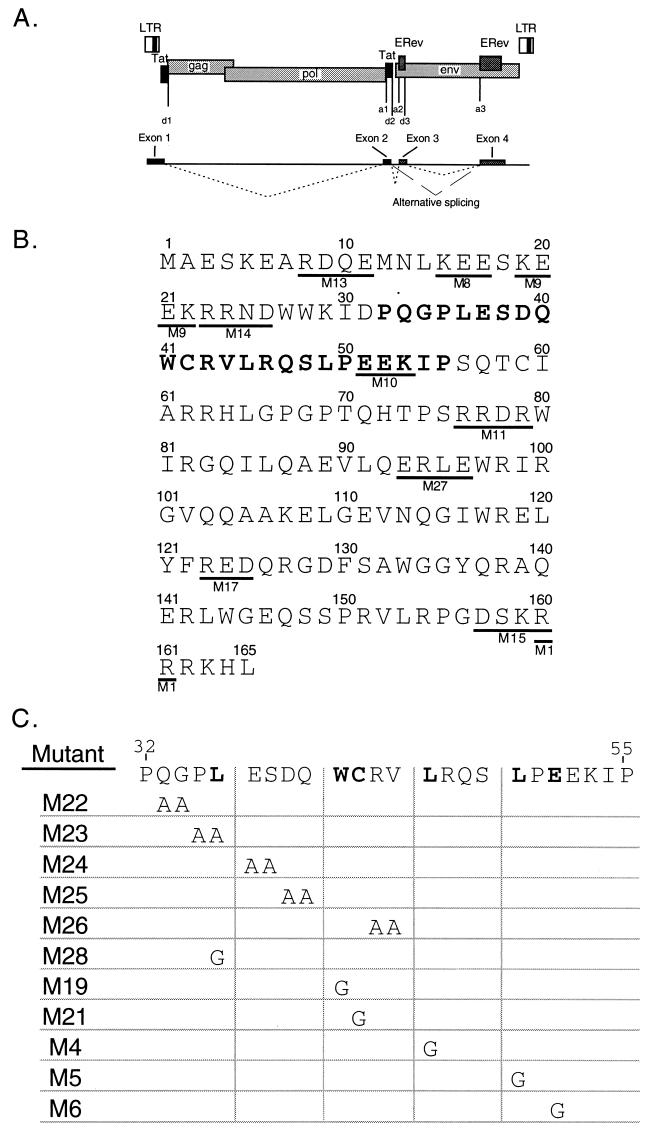

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic of the EIAV genome showing long terminal repeats (LTR); coding regions for gag, pol, env, and the four exons; and splice donor and splice acceptor sites. Dotted lines connecting exons indicate the ERev-independent splicing pattern used to form the completely spliced ETat-ERev bicistronic transcript (exons 1 to 4). Exons 1 and 2 code for ETat; exons 3 and 4 code for ERev. Dashed lines indicate the ERev-dependent alternative splicing pattern used to form a transcript containing exons 1, 2, and 4. Exon 1 contains nucleotides 211 to 459, exon 2 contains nucleotides 5135 to 5275, exon 3 contains nucleotides 5436 to 5536, and exon 4 contains nucleotides 7234 to 7641. Adapted from Martarano et al. (40). (B) Charged mutations made in EIAV Rev by site-directed mutagenesis. Clusters of 4 amino acids (underlined) in which 3 or 4 residues were charged were mutated to alanine (with the exception of one mutant) by the Kunkel method (29, 30). Mutants are designated by M and a number (shown below the mutated residues). In M1, two arginines (160 and 161) were changed to glycines. Numbers above the sequence show residue positions. The previously defined minimal NES of ERev is indicated by bold characters (17, 39). (C) Site-directed mutations in the NES of EIAV Rev. The wild-type NES (aa 32 to 55) is shown at the top. Specific mutations were generated in the NES in the context of full-length ERev by the Kunkel method. Pairs of residues were mutated to alanines, or single amino acids were changed to glycines.

The ERev NES is atypical since it does not fit the loose consensus sequence for CRM1-interacting NESs (3, 17, 23, 28, 37, 39, 42). However, we have recently shown that ERev-dependent RNA export is inhibited by LMB; thus, the ERev NES presumably interacts with CRM1 (50). In previous studies, the ERev NES has been mutated as a fusion peptide (17, 39). Mancuso et al. (39) implicated many of the ERev NES residues as important. Since the NES has not been examined in the context of the full ERev, it is unknown if the atypical NES of ERev is involved in alternative splicing.

To determine if ERev-mediated RNA export and alternative splicing are separable, we have identified mutants that affect these functions. We have defined the residues important for the atypical NES and found that the NES is not required for alternative splicing. We have found several mutants that attenuate or abrogate alternative splicing. These mutants also disrupt RNA export, suggesting that ERev-dependent export and alternative splicing share activities in common. Mutants were further characterized for subcellular localization, nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling, and multimerization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and mutagenesis.

The pRS-ERev wild-type expression vector used in this study has been described elsewhere (40). The Rev-negative EIAV provirus pFL85-11 has been described elsewhere (40). ERev has a 4-base deletion frameshift after serine 75 (54). Mutations in ERev were made by use of a method based on Kunkel mutagenesis (29, 30) and confirmed by sequence analysis (with Sequagel reagent from National Diagnostics and a Sequenase kit from U.S. Biochemicals). Mutants were designated by M and a number (e.g., M1). M1/11, a double mutant of M1 and M11, was constructed by use of restriction sites to excise a fragment containing the M11 mutations and to subclone this fragment into the M1 mutant vector.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-ERev and GFP-ERev mutants were constructed by excising the NheI/PstI fragment from peGFP-C1 (Clontech) and ligating it into XbaI/PstI digests of pRS-ERev and the M4, M27, and M1 mutants.

The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter pDM138ERRE-all was made by subcloning a PCR fragment (EIAV nucleotides 5278 to 7532) from the pFL85-11 provirus into the ClaI site of pDM138 (26). Primers used to amplify the full-length EIAV RRE (ERRE-all) fragment were as follows: 5′ primer, GCGGGATCCATCGATTTTGATATATGGGATTATTT; 3′ primer, GCGGGATCCATCGATAAATCTCCCCTTTGGTCTTC.

Cells and transfections.

293 cells were used for CAT assays and Northern blots, 293T cells were used to monitor the expression of the mutated proteins by Western blotting, canine osteosarcoma cell line D17 was used for gag expression from the Rev-negative EIAV provirus and in the alternative splicing assay, and 3T3 cells were used for microscopy analysis of the subcellular localization of GFP fusion proteins. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C with 10% CO2.

Approximately 24 h before transfection, each well of a six-well cluster dish for CAT assays received 1/60 to 1/70 of a confluent plate (10 cm) of 293 cells and each 10-cm plate for protein or RNA analysis received 1/8 to 1/10 of a confluent plate (10 cm) of 293 or 293T cells. Cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate procedure. pUC118 was used to balance the total amount of DNA in each transfection. Wild-type or mutated ERev proteins were expressed from the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoter. CAT assays were performed in triplicate with separate calcium phosphate precipitations. In the absence of any ERev protein (wild type or mutated), an empty RSV expression vector (pRSV) (24) was transfected into cells. A β-galactosidase reporter, pCH110 (43), was included in all CAT assay transfections to normalize for transfection efficiency. A luciferase reporter, pGL3 (Promega), and pCH110 were included in all transfections for RNA analysis to monitor transfection efficiency. On the following day, the cells were given fresh media. At 2 days after transfection, cells were harvested to measure CAT activity, analyze protein expression, or analyze RNA.

D17 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well in six-well cluster dishes 24 h prior to transfection. For proviral complementation, D17 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of each plasmid and 5 μl of FuGene (Boehringer Mannheim) diluted in 100 μl of DMEM. For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis, cells were transfected with calcium phosphate. The Rev-negative EIAV proviral clone pFL85-11 was transfected with pRS expression plasmids containing wild-type or mutated ERev proteins or with pKS Bluescript (Stratagene). Two days later, cells were collected for analysis.

3T3 cells were diluted 1:200 from 10-cm dishes and plated on six-well dishes or glass chamber slides (Lab-Tek) for confocal microscopy. At 24 h after plating, cells were transfected with Superfect reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GFP fusion proteins (0.3 to 0.5 μg) and 1.6 to 2 μg of pRS-ERev or mutated expression plasmids or pRSV were transfected. After 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then stained with a solution containing 1 μg of Hoechst 33258 DNA dye per ml and 0.5% Nonidet P-40 for 15 min at room temperature. For experiments with LMB, cells were treated with 5 nM LMB for 4 h before fixation.

CAT assay.

Transfected cells were harvested with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–5 mM EDTA and transferred to microcentrifuge tubes. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 2 min, and the pellets were resuspended in 250 to 500 μl of 0.25 M Tris (pH 7.5). Cells were lysed by three cycles of freezing and thawing and clarified.

Each lysate (10 to 50 μl) was tested in a β-galactosidase assay. The β-galactosidase values were used to normalize the lysates. The CAT reactions were carried out with a 100-μl total volume containing 0.25 M Tris, 1 mM acetyl coenzyme A, and 3 μl of [14C]chloramphenicol (50 to 60 mCi/mmol). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for several hours. The substrate and products were separated by thin-layer chromatography (Whatman PE SIL G plates). The amounts of unacetylated and acetylated [14C]chloramphenicol were quantitated with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager, and the percent acetylation for each sample was calculated.

Western blots.

293T cells were washed once with PBS–5 mM EDTA, lifted from the plates in 5 ml of PBS–5 mM EDTA, and transferred to conical tubes. Cells were centrifuged, resuspended in fresh Western lysis buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitors), subjected to three cycles of freezing and thawing, centrifuged again, and normalized with the Bio-Rad protein assay such that 150 μg of total protein was loaded. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed with 14% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF-Plus membranes (MSI), incubated with rabbit anti-ERev antibodies (a kind gift from N. Rice), and visualized after incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies by chemiluminescence staining. Protein size was determined with molecular weight markers (Amersham Life Science).

D17 cells were harvested by scraping in PBS, transferred to 1.5-ml tubes, and centrifuged. Cell pellets were lysed in 50 μl of TNT (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) buffer–Boehringer protease inhibitor mixture on ice for 10 min and then centrifuged for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined and adjusted so that 50 μg of each sample was used for SDS-PAGE (4 to 12% bis-tris gels; Novagen). Gels were run in 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid buffer (Novex). Proteins were transferred to Immobilon membranes, incubated with rabbit anti-EIAV p27gag antibodies (a kind gift from N. Rice), and visualized after incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies by chemiluminescence staining. Protein size was determined with molecular weight markers (Amersham Life Science).

RT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was prepared from transfected cells by the RNeasy method (Qiagen) and eluted in 100 μl of water. cDNA synthesis reactions were carried out as described previously (40); reaction mixtures were diluted to 100 μl with water and heated to 95°C for 10 min. PCRs were done with a total volume of 50 μl and contained 5 μl of diluted cDNA, 0.05 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 ng of each oligonucleotide primer, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 2 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). Reactions were carried out under conditions that were established to yield semiquantitative results: 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min for 20 cycles. The reaction products (20 μl) were then run on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The PCR primers used were previously described (40); primers ex-2 (positions 5138 to 5157) and ex-4 (positions 7264 to 7245) yielded a 267-bp PCR product representing the constitutively spliced message and a 167-bp PCR product representing the alternatively spliced message in which exon 3 is skipped.

GFP analysis.

3T3 cells were scored blind by use of a Nikon Diaphot 300 epifluorescence microscope with a ×20 objective. Cells on chamber slides were covered with Gel/Mount (Biomedia Corp.) and a glass coverslip for confocal microscopy. Images shown were acquired on a Bio-Rad MRC1024UV confocal scanning light microscope with a ×40 objective and an electronic zoom.

Northern analysis of RNA.

293 cells were harvested with PBS–5 mM EDTA, pelleted at approximately 14,000 × g, washed with PBS, gently resuspended in cytoplasmic RNA lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.4], 140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40), incubated on ice for 2.5 min, and then pelleted at 4,700 × g. The supernatant was clarified at 14,000 × g, designated the cytoplasmic fraction, and transferred to a new microcentrifuge, and RNA STAT-50 LS (Tel Test) was added. A small sample of each supernatant was set aside for β-galactosidase analysis. Cytoplasmic RNA was extracted with the addition of chloroform. The RNA was then precipitated, incubated with DNase for 15 min at 37°C, phenol extracted, and precipitated. Concentrations were determined by measuring the A260. Cytoplasmic RNA (20 μg) was precipitated, loaded, and separated on a 1% agarose–6.5% formaldehyde gel. Equal loading was determined by ethidium bromide staining of the gel; 32S rRNA precursors were not detected in the cytoplasm, demonstrating no major nuclear contamination. The RNA was transferred to a Duralon UV membrane (Stratagene). Blots were hybridized with probes in QuikHyb (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The probe templates consisted of either a PCR product from pDM138 containing the CAT gene or the SphI/NcoI digest of pGL3. Probes were radiolabelled with [α-32P]dCTP by use of a random-primer kit (Stratagene).

RESULTS

Construction and expression of ERev mutants.

To determine residues important for ERev functions, ERev mutants were generated. First, mutants in which clusters of charged residues were replaced were created (6). Charged residues are likely to be found on the surface of a protein and may be involved in protein-RNA or protein-protein interactions. Eleven mutants of this kind were created: M1, M8 to M11, M13 to M15, M17, and M27 (Fig. 1B); all charged residues were substituted with alanines, except that in mutant M1 two arginines (amino acids [aa] 160 and 161) were changed to glycines. A double mutation between M1 and M11 was made and designated M1/11. Second, specific mutations within the previously identified NES peptide of ERev (aa 32 to 55) were made (17, 39). Pairs of amino acids were changed to alanines, resulting in M22 to M26, and single amino acids were changed to glycines, resulting in M4 to M6, M19, M21, and M28 (Fig. 1C).

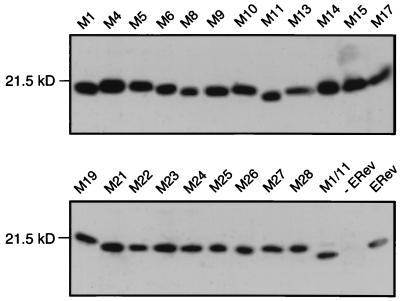

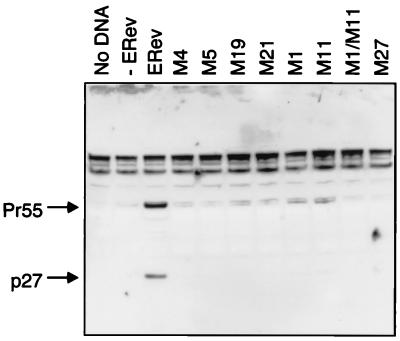

All the mutations were transiently transfected into 293T cells to determine protein expression. A Western blot of 293T cell lysates probed with an anti-ERev serum demonstrated that all the mutants were expressed (Fig. 2). Mutants M1 and M11 ran slightly below the wild-type size, and the M1/11 mutant had greater mobility than either single mutant. Substitution of positive charges or proteolytic cleavage may explain the different mobility of M1/11.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of 293T lysates to monitor the expression of wild-type or mutated ERev. 293T cells were transfected with 40 μg of expression plasmids encoding wild-type or mutant ERev. Two days after transfection, cell lysates were prepared and normalized to total protein. Proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted with a rabbit anti-ERev antiserum. Lanes are labeled to show the transfected ERev mutants, wild-type ERev (ERev), or mock transfection (−ERev). The position and size of the relevant molecular mass marker are indicated.

Effects of mutants on ERev-mediated nuclear export of unspliced RNA.

To quantitatively assess the ability of each ERev mutant to export an intron-containing RNA into the cytoplasm, expression of the CAT gene from an unspliced transcript was measured. A 2.3-kb fragment from the EIAV envelope containing the RRE (40) was cloned into the previously described pDM138 CAT reporter (26) to generate pDM138ERRE-all (2) (Fig. 3A). Expression of the CAT gene located in a modified HIV-1 intron is dependent on the cytoplasmic accumulation of the unspliced transcript produced from the reporter (24).

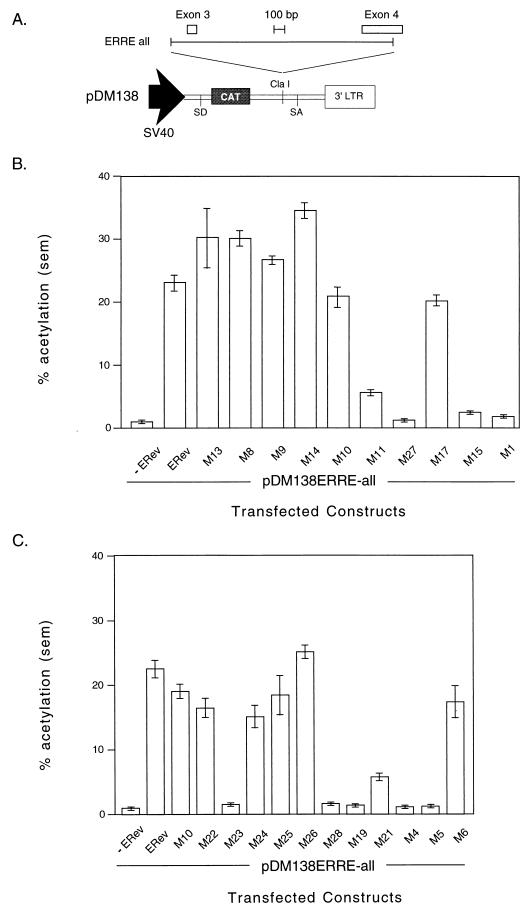

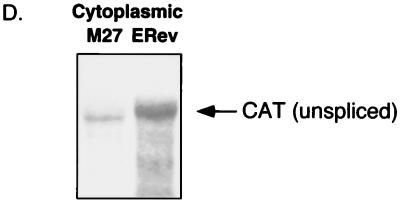

FIG. 3.

(A) Schematic of the ERev-dependent CAT reporter construct pDM138ERRE-all. Shown are the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter, the HIV-1 second intron splice donor (SD) and splice acceptor (SA) sites, the location of the CAT gene, the unique ClaI cloning site, and the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR). The sequence from the env region of a Rev-negative EIAV provirus (nucleotides 5278 to 7532) was cloned into the ClaI site and served as the RRE. This fragment, designated ERRE-all, contained EIAV exon 3 and part of exon 4. The EIAV fragment and exons are drawn to scale, but the vector is not. (B) CAT assay of 293 lysates transfected with an ERev reporter construct transactivated by wild-type or mutant ERev. 293 cells were transfected in triplicate with 0.2 μg of the EIAV RRE containing CAT reporter pDM138ERRE-all; 0.2 μg of the β-galactosidase expression vector pCH110; and 1 μg of expression plasmids carrying wild-type, mutant, or no ERev. Two days after transfection, crude lysates were prepared for analysis of CAT activity after normalization for transfection efficiency by a β-galactosidase assay. The activities of the indicated ERev mutants, wild-type ERev (ERev), or reporter alone (−ERev) are reported as mean percent acetylation. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (sem). (C) CAT assay of 293 lysates transfected with an ERev reporter construct transactivated by wild-type ERev or NES mutants. Transfections and CAT assays were performed as described in panel B. Percent acetylation (mean ± sem) is shown for the indicated NES mutants, wild-type ERev (ERev), or reporter alone (−ERev). (D) Northern analysis of pDM138ERRE-all. 293 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pDM138ERRE-all, 5 μg of either pRS-ERev (lane ERev) or M27 (lane M27), 5 μg of pGL3, and 2 μg of pCH110. Two days after transfection, cytoplasmic RNA was prepared. Cytoplasmic RNA (20 μg) was run on a 1% agarose–formaldehyde gel, transferred, and probed for the CAT gene. The unspliced message is indicated. Differential background signals in the two lanes correlated with CAT activity.

The panel of ERev mutants was cotransfected into 293 cells with pDM138ERRE-all. The activity of pDM138ERRE-all alone was less than 1% the activity of the reporter with ERev, demonstrating a requirement for ERev. No ERev transactivation occurred with ERRE-all in the antisense orientation, showing that this element was necessary and acted at the level of RNA (data not shown).

Of the 11 alanine (or glycine for M1) mutants (Fig. 1B), M1, M15, and M27 had activity ≤10% that of the wild type (Fig. 3C). M1 and M15 map to the C terminus of ERev. M27 (aa 93 to 96) is located in the central charged region of ERev. M11 (aa 76 to 79), also located in the central region of the protein, had 25% wild-type activity. The other alanine mutants had greater than 80% wild-type activity. As expected, the double mutant (M1/11) had less than 10% wild-type activity in the CAT assay (data not shown). Thus, two regions outside the ERev NES are essential for RNA export: a middle region (M11 and M27, aa 76 to 96) and the C terminus (M15 and M1, aa 157 to 163).

The NES of ERev was analyzed in detail by use of ERev mutants (Fig. 1C) to transactivate pDM138ERRE-all (Fig. 3C). The NES mutants with pairs of amino acids changed to alanines all had greater than 70% wild-type activity (M22 and M24 to M26), except for M23, which had less than 10% wild-type activity. Proline 35 and leucine 36 were mutated in M23; when leucine 36 was singly mutated to glycine (M28), less than 10% wild-type activity resulted. Changing leucines 45 and 49 (M4 and M5, respectively) independently to glycines abrogated function, producing less than 10% wild-type activity. Changing tryptophan 41 to glycine (M19) resulted in less than 10% wild-type activity, while changing cysteine 42 to glycine (M21) resulted in an intermediate phenotype, with 25% wild-type activity. Thus, hydrophobic residues, including three leucines, are important in the ERev NES. Consistent with the experiment shown in Fig. 3B, M10 (aa 51 to 53) had 85% wild-type activity. The glutamic acid at position 51 was mutated to glycine in M6, resulting in greater than 70% wild-type activity.

To verify that CAT activity correlated with unspliced RNA in the cytoplasm, RNA from pDM138ERRE-all was analyzed directly by Northern blotting (Fig. 3D). 293 cells were cotransfected with pDM138ERRE-all and pRS-ERev or M27. Cytoplasmic RNAs were prepared, and the unspliced message was detected with a CAT probe. Wild-type ERev increased the cytoplasmic appearance of the unspliced message compared to M27 (Fig. 3D). A CAT assay with the same transfected cells was consistent with the results shown in Fig. 3C, and similar results were obtained with NES mutant M4 (data not shown). Thus, Northern blotting confirmed that CAT activity resulted from the export of unspliced RNA.

To confirm that the reporter system paralleled natural responses, selected ERev mutants were tested for their ability to complement a Rev-negative EIAV provirus. D17 cells were transfected with pFL85-11 and wild-type or mutated ERev expression vectors. The selected mutants included several NES mutants (M4, M5, M19, and M21), one C-terminal mutant (M1), the middle region mutants (M11 and M27), and double mutant M1/11. Cell lysates were analyzed for gag expression by Western blotting (Fig. 4). In the absence of ERev, no p27gag or Pr55gag precursors were detected, consistent with previous results (40). In the presence of ERev, p27 and Pr55 were detected. The indicated mutants were negative for complementation of the provirus. M11 and M21 had partial (25% wild-type) activity in the CAT assay, suggesting that the sensitivity of the CAT assay was greater. The complementation results suggest that the CAT assay is representative of the effects of ERev and ERev mutants on an EIAV provirus.

FIG. 4.

Western blot of trans-complementation of a Rev-negative EIAV provirus. D17 cells were mock transfected (no DNA) or transfected with 0.5 μg of Rev-negative EIAV provirus pFL85-11 and 0.5 μg of expression plasmids carrying wild-type ERev (ERev), selected ERev mutants, or no protein (−ERev). Two days after transfection, crude lysates were prepared and analyzed for EIAV p27 by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. A rabbit anti-EIAV p27gag antibody detected p27 and Pr55, the gag precursor.

Effects of mutants on ERev-dependent alternative splicing.

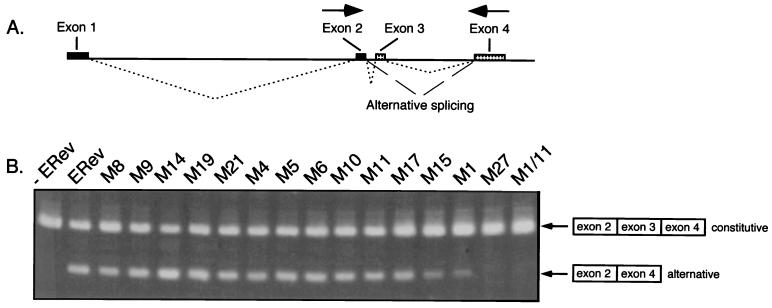

It was shown previously that a Rev-negative EIAV provirus expresses only a four-exon ETat-ERev mRNA at high levels; complementation with wild-type ERev results in a decrease in the amount of the four-exon mRNA and the appearance of a related ETat mRNA lacking exon 3 (40). The Rev-negative EIAV proviral clone pFL85-11 was transfected alone or cotransfected with expression plasmids encoding either wild-type or mutated ERev proteins (Fig. 5). RNA from transfected cells was prepared and converted to cDNA, and cDNAs were subjected to low-cycle PCR amplification. Consistent with previous results (40), in the absence of EIAV Rev, the Rev-negative EIAV provirus expressed a constitutively spliced message but no alternatively spliced, three-exon transcript. When a wild-type ERev expression plasmid was supplied in trans, levels of the constitutively spliced message were decreased, with a concomitant appearance of the mRNA lacking exon 3. A qualitative comparison of the levels of the skipped mRNA product with the indicated ERev mutants revealed that export-competent mutants (M8, M9, M14, M6, and M10), NES mutants (M19, M21, M4, and M5), and one middle region mutant (M11) had little effect on the appearance of the skipped mRNA product. However, the two C-terminal mutants (M15 and M1) resulted in lower levels of the skipped mRNA product. One of the two middle region mutants (M27) completely abolished the production of the three-exon mRNA, as did the double mutant (M1/11). These results, including the partial effects of M1 and M15, were reproduced in several experiments. Thus, the NES is not involved in alternative splicing, and M27 defines a region required for RNA export and alternative splicing.

FIG. 5.

(A) Schematic of exon splicing in EIAV. The splicing pattern for the constitutively fully spliced message for EIAV (exons 1 to 4) is indicated by dotted lines. Exons 1 and 2 code for ETat; exons 3 and 4 code for ERev. Dashed lines indicate the ERev-dependent skipping of exon 3 to form a transcript containing exons 1, 2, and 4. Arrows represent primers for RT-PCR. (B) RT-PCR analysis of ERev-dependent exon skipping. RNA from cells transfected with 3 μg of pFL85-11 (−ERev) and complemented with 1 μg of expression plasmids carrying wild-type ERev (ERev) and mutant ERev (as indicated) was prepared and converted to cDNA. PCR amplification was done with primers to EIAV exon 2 and exon 4. DNA products were resolved on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The skipped exon message (exons 2 and 4, alternative) and the constitutively spliced message (exons 2 to 4, constitutive) are indicated.

Subcellular localization and nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling.

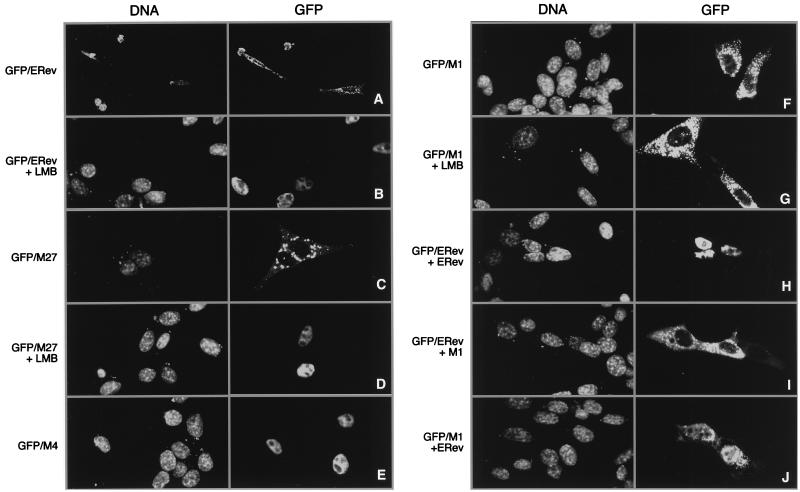

Mutants negative for RNA export or both functions of ERev could be defective in one or more activities important for ERev. Such activities are likely to include RNA binding, multimerization, subcellular localization, and nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling. To further define the nonfunctional ERev mutants, subcellular localization and shuttling were assessed. GFP was fused to the N terminus of ERev to make GFP-ERev; this fusion protein had wild-type activity in the CAT assay (data not shown). GFP-ERev was transfected into 3T3 cells to determine subcellular localization. In at least half of the cells, GFP-ERev was localized in a dotted pattern in the cytoplasm, with little in the nucleus (Fig. 6A). In other cells, the fusion protein was observed exclusively in the nucleus or occasionally in the dotted pattern, with significant amounts in the nucleus. Table 1 summarizes the results obtained with the GFP fusion proteins and coexpression of mutants (see below). Cells expressing the highest levels of GFP-ERev tended to have the exclusive cytoplasmic localization, suggesting a relationship between the amount of ERev and the dotted pattern. The cytoplasmic dots could represent (i) the steady-state localization of GFP-ERev shuttling between the nucleus and the cytoplasm or (ii) nonfunctional GFP-ERev trapped in the cytoplasm.

FIG. 6.

Localization of GFP-ERev fusion proteins and effects of coexpression or LMB treatment. 3T3 cells were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of GFP-ERev (A, B, H, and I), GFP-M27 (C and D), GFP-M4 (E), or GFP-M1 (F and G) and 2.5 μg of either an empty RSV expression vector (A to G), wild-type ERev (H and J), or M1 (I). On the following day, some cells were treated with 5 nM LMB for 4 h (B, D, and G), and then all cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with a DNA dye. DNA staining (left panels) and GFP fluorescence (right panels) are shown. Fields are representative of least three independent, blind experiments. Images were acquired on a confocal microscope; a 2× electronic zoom was used on all panels but A. Brightness and contrast were adjusted with Adobe Photoshop.

TABLE 1.

Localization of GFP fusion proteins with ERev or ERev mutants in the presence of ERev, ERev mutants, or LMBa

| Cotransfectant | Localization of the indicated GFP construct

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfused GFP | ERev | M1 | M4 | M27 | |

| None | Whole | 50% of cells cytoplasmic and 50% nuclear | Cytoplasmic | Nuclear | Cytoplasmic |

| Wild type | Whole | Nuclear | Nuclear | Nuclear | Nuclear |

| M1 | ND | Cytoplasmic | ND | Cytoplasmic | ND |

| M15 | ND | Cytoplasmic | ND | Cytoplasmic | ND |

| M11 | ND | Nuclear | ND | ND | Nuclear |

| M1/11 | ND | Cytoplasmic | ND | ND | ND |

| M4 | ND | Nuclear | Nuclear | ND | Nuclear |

| M27 | ND | Nuclear | ND | Nuclear | Nuclear |

| None + LMB | Whole | Nuclear | Cytoplasmic | Nuclear | Nuclear |

3T3 cells were cotransfected with the indicated GFP fusion expression plasmid and a pRS derivative expression plasmid (Cotransfectant). On the following day, cells were fixed and scored by epifluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy. Treatment with 5 nM LMB was done for 4 h before fixation. ND, not determined.

To determine if GFP-ERev was shuttling, 3T3 cells transfected with GFP-ERev were treated with LMB, an inhibitor of HIV-1 Rev-dependent export (56). Export of unspliced messages by ERev is inhibited by LMB, as measured by CAT assays (50). If GFP-ERev were shuttling, then cytoplasmic GFP-ERev should have entered the nucleus and accumulated due to the LMB block. In the presence of LMB, GFP-ERev was localized to the nucleus and excluded from nucleoli in all cells (Fig. 6B). Treatment of cells expressing GFP with LMB did not change the whole-cell localization of GFP, showing that LMB was specific for ERev (Table 1). In addition, time-lapse microscopy of a single cell with GFP-ERev in the cytoplasmic dotted pattern showed the fusion protein accumulating in the nucleus with LMB (50). Thus, the cytoplasmic dotted pattern of GFP-ERev in some cells represents the steady-state localization of a shuttling fusion protein.

GFP fusions with the M27, M4, and M1 mutants were made to determine the subcellular localization of these mutants. GFP-M27 had a cytoplasmic dotted localization like that of GFP-ERev and was localized to the nucleus by treatment with LMB (Fig. 6C and D). These data indicated that M27 was competent for nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling. In contrast, GFP-M4 was nuclear (Fig. 6E) and was not affected by LMB (Table 1), consistent with a mutation in the NES. GFP-M1 had a cytoplasmic dotted pattern (Fig. 6F). When cells expressing GPF-M1 were treated with LMB, the fusion protein remained in the cytoplasm, showing that the fusion protein did not enter the nucleus (Fig. 6G). The results suggested that M1 was defective for nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling. Specifically, the C terminus appeared to be involved in nuclear localization.

Multimerization of ERev mutants.

To determine if unfused ERev could alter the localization of the GFP-ERev fusion protein, GFP/ERev and ERev were coexpressed in 3T3 cells at a ratio of 1:4. In the presence of ERev, the fusion protein was observed throughout the nucleus, except for the nucleoli, and was virtually absent from the cytoplasm (Fig. 6H). This result suggested that the unfused ERev protein could multimerize with the fusion protein and “drag” any GFP-ERev located in the cytoplasm to the nucleus. This result further implied that ERev has a nuclear steady-state localization. Nuclear dragging of GFP-ERev was observed at a 1:1 ratio with unfused ERev, suggesting that ERev was not cytoplasmic and saturating GFP-ERev export (data not shown). Unfused GFP was unaffected by coexpression with ERev, demonstrating that nuclear relocalization by ERev was specific to the ERev portion of the GFP-ERev fusion protein (Table 1).

Nonfunctional ERev mutants were tested for their ability to multimerize and relocate GFP-ERev. Like the wild-type unfused protein, M4, M11, and M27 localized the fusion protein to the nucleus (Table 1). In addition, GFP-M27 was localized to the nucleus by the coexpression of ERev or M27 (Fig. 6H and Table 1). M1, M15, and M1/11 did not change the cytoplasmic dotted localization of GFP-ERev (Fig. 6I and Table 1), consistent with a nuclear localization defect for the C-terminal mutants. Alternatively, the mutants might have failed to interact with GFP-ERev. When ERev was coexpressed with GFP-M1, the GFP fusion protein was observed in the nucleus, suggesting that ERev and M1 could multimerize (Fig. 6J). Coexpression of GFP-M4 and either of the C-terminal mutants relocalized the NES mutant to the speckled cytoplasmic pattern, while ERev or M27 did not change the nuclear localization of M4 (Table 1). Moreover, all negative mutants appeared competent for multimerization with another ERev protein.

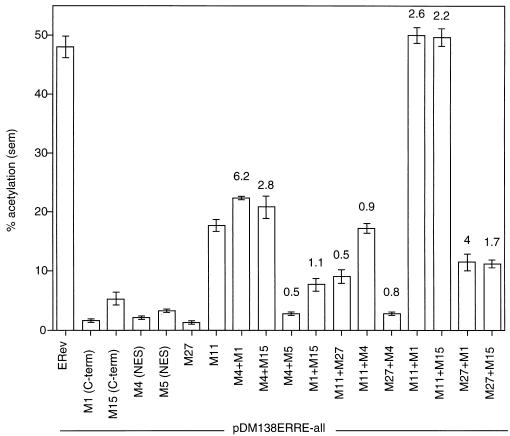

The interaction between different ERev mutants in the nuclear dragging experiments raised the possibility that mutants could form active complexes by complementing the defects of each other. To test this hypothesis, the nonfunctional ERev mutants were transfected separately or together with pDM138ERRE-all and assayed for CAT activity (Fig. 7). Each of the mutants showed less than 10% wild-type activity, except for M11, which showed 37% wild-type activity, consistent with Fig. 3. Cotransfection of M4 and M1 resulted in a sixfold increase in activity over the sum of their individual activities and 46% wild-type activity (M4+M1). If either M4 or M1 was fused to GFP, complementation still occurred (data not shown). A similar effect was seen with the cotransfection of M4 and M15 (M4+M15), although the fold increase (2.8) was smaller. As a control, M4 was cotransfected with another NES mutant (M5); two NES mutants should not complement each other. The activity of the two cotransfected NES mutants showed a twofold decrease compared to the sum of their individual activities (compare M4+M5 to M4 and M5). Similarly, cotransfection of the two C-terminal mutants resulted in only a small (10%) increase (M1+M15); these mutants were judged not to complement each other because the increase was within the error of the cotransfection activity. The middle region mutants M11 and M27 failed to complement each other, as judged by the twofold decrease in activity when they were cotransfected (M11+M27). The activity with M11 cotransfected with M4 was 36% wild-type activity, but this was no greater than the activity with M11 alone (M11+M4 compared to M11). Similarly, M27 and M4 did not complement each other (M27+M4). Finally, the two middle region mutants complemented the C-terminal mutants (M11+M1, M11+M15, M27+M1, M27+M15), with the cotransfection of M27 and M15 having the smallest effect—a 70% increase over the individual activity sum. The complementation experiments demonstrated that (i) complexes between some pairs of mutants were functional, (ii) there were no mutants that could not complement at least one other mutant, and (iii) several of the active domains of ERev could act in trans.

FIG. 7.

Nonfunctional ERev mutants can be complemented for RNA export. pDM138ERRE-all (0.2 μg), 0.2 μg of pCH110, 0.6 μg of pUC118, and 1 μg of RSV promoter expression vectors were transfected into 293 cells. The RSV vectors expressed ERev, M1, M4, M5, M11, M15, M27, or no protein (to balance the total amount of RSV promoter). CAT assays were performed as previously described. A plus sign indicates that two mutants were coexpressed in trans. The absolute percent acetylation (mean ± standard error of the mean [sem]) is reported for each transfection or cotransfection. The ratios of the cotransfection activity to the sum of the independent activities for two mutants are reported above each cotransfection. C-term, C terminal.

DISCUSSION

ERev mediates the export of unspliced RNA and the alternative splicing of the fully spliced transcript. Furthermore, ERev has a nuclear localization, shuttles, and forms multimers. The two roles of ERev are separable. RNA export requires a functional NES, while alternative splicing does not. However, both export and splicing are sensitive to several mutations outside the NES, suggesting that these functions share ERev activities. C-terminal mutations that disrupt nuclear localization affect both functions. Another mutation, absolutely necessary for both functions, results in a mutant that behaves like wild-type ERev for multimerization, subcellular localization, and nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling and thus may be defective for interacting with RNA.

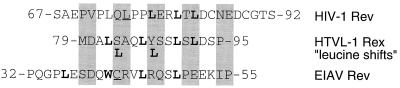

The ERev NES reveals the extensive variation that is possible in the NESs that interact with CRM1. The ERev NES is atypical in its spacing but not its composition. Leucines 36, 45, and 49 and tryptophan 41 are absolutely required for the NES, while cysteine 42 decreases export activity and may be analogous to leucine 75 in the HIV-1 Rev NES (Fig. 8), which has an intermediate phenotype (37). Other mutations in the NES result in wild-type activity, suggesting that we have defined all of the required residues. The characteristic LXL motif in the NESs of HIV-1 Rev, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Rex, and other NES-bearing proteins is not present in ERev (Fig. 8). In addition, the 5-residue spacing between leucine 36 and tryptophan 41 is not present in other NESs. Cellular NESs matching the Rev consensus sequence have been identified (9, 16, 18, 20, 44, 55). It will be interesting to determine if cellular NESs similar to the one in ERev exist.

FIG. 8.

Comparison of the NESs from HIV-1 Rev, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Rex, and ERev. The NESs of HIV-1 Rev (aa 70 to 84), HTLV-1 Rex (aa 80 to 96), and ERev (aa 32 to 55) are shown aligned to best match important residues. Bold residues are required for function in each protein, whereas underlined residues give an intermediate phenotype; the most N-terminal leucine in HIV-1 Rev has been mutated without effect (37). Also shown are the allowable “leucine shifts” in the Rex NES (28).

ERev has a nuclear steady-state localization and shuttles. GFP-ERev had a cytoplasmic dotted localization when highly expressed. Further, GFP-ERev displayed wild-type activity for RNA export and accumulated in the nucleus when export was blocked by LMB or a mutation. These data argue that GFP-ERev shuttles and that its observed cytoplasmic localization represents the steady state. It has been established that the HIV-1 Rev protein shuttles and that its apparently exclusive nuclear and nucleolar localization is a steady-state condition (41). Cotransfection of ERev and GFP-ERev made the fusion protein exclusively nuclear. This finding implies that ERev interacts with the fusion protein and changes the steady-state localization of the fusion protein to reflect the nuclear steady-state localization of ERev. Several of the nonfunctional ERev mutants (M27, M4, and M11) could localize GFP-ERev to the nucleus, suggesting that these mutants also have a nuclear steady-state localization. Furthermore, the M27 mutant, negative for RNA export and alternative splicing, shuttles.

Three pieces of data argue that the C terminus of ERev promotes nuclear localization. First, M1, M15, and M1/11 in trans did not alter the localization of GFP-ERev. Second, LMB caused the nuclear accumulation of GFP-ERev but not GFP-M1. This finding implies that GFP-M1 failed to enter the nucleus. Last, GFP-M4, which is normally nuclear, had a cytoplasmic localization in the presence of the C-terminal mutants but not wild-type ERev. The ability of M4 (unfused or as a GFP fusion) and either C-terminal mutant (M1 or M15) to complement each other in the RNA export assay (see below) suggests shuttling of an M4-M1 complex. The cytoplasmic localization of GFP-M4 in the presence of the C-terminal mutants likely reflects a change in the rates of import and export of the mixed multimer complex. Interestingly, the M1 and M15 mutants retained partial activity for alternative splicing despite the fact that they were nuclear localization deficient. It is possible that small amounts of the M1 and M15 mutants entered the nucleus by diffusion rather than by a receptor-mediated process and mediated alternative splicing, albeit to a lesser degree than the wild-type protein. Consistent with this idea, a small amount of GFP-M1 in the nucleus was detected by confocal microscopy (data not shown). This finding also implies that alternative splicing requires less ERev in the nucleus than RNA export.

The ability of unfused ERev to change the steady-state localization of GFP-ERev implies that ERev is a multimer. Likewise, M27, M4, and M11 can also multimerize with GFP-ERev. The expression of ERev alters the localization of GFP-M1, suggesting that the C terminus is not required for multimerization. All functional mutants could drag GFP-ERev into the nucleus (data not shown). Furthermore, the coexpression of certain nonfunctional ERev mutants resulted in functional complementation. Complementation implies that all of the mutants could multimerize with at least one other mutant. We found, for example, that cotransfection of M4 (NES mutant) and M1 (nuclear localization defect) produced activity sixfold higher than the sum of the individual mutant activities. This activity most likely reflected the formation of mixed multimers which were now both export and import competent. Multimerization of ERev has not been previously demonstrated.

Nonfunctional ERev mutants belong to one of two complementation groups. The first group contains the NES mutants (M4 and M5) along with the middle region mutants (M11 and M27), and the second group contains the C-terminal mutants (M1 and M15). Mutants within a complementation group may have related functions. However, this is not the case for M4 and M27. M4 is an NES mutant, while M27 can shuttle. M4 and M27 can interact, so the inability to multimerize does not account for the lack of complementation (Table 1). A simple interpretation is that a complex of M27 and M4 imports but that NES function and another step needed for RNA export (i.e., RNA binding) cannot function in trans. In contrast, M11 and M27 can interact (Table 1), and both retain at least partial shuttling activity (Table 2), but they do not complement. These data suggest a similar function. Both mutants affect export, but the effect of M11 is less dramatic than that of M27. M27 abrogates alternative splicing, while M11 affects this function only in the context of a double mutant. Thus, M11 may be a less severe version of M27. Further experiments are necessary to determine the activity or activities of M27 and M11.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the activities of wild-type or mutant EReva

| ERev Protein | Mutated residues | Reporter (CAT) assay | Proviral complementation | Alternative splicing | Shuttling | Multimerization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Charged mutants | ||||||

| M13 | 8–11 | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ++ |

| M8 | 15–17 | ++ | ND | ++ | ND | ++ |

| M9 | 19–22 | ++ | ND | ++ | ND | ++ |

| M14 | 23–26 | ++ | ND | ++ | ND | ++ |

| M10 | 51–53 | ++ | ND | ++ | ND | ++ |

| M11 | 76–79 | + | − | ++ | ND | ++ |

| M27 | 93–96 | − | − | − | ++ | ++ |

| M17 | 123–125 | ++ | ND | ++ | ND | ++ |

| M15 | 157–160 | − | ND | + | Nuclear entry defect | ND |

| M1 | 161–162 | − | − | + | Nuclear entry defect | ++ |

| M1/11 | 76–79 and 161–162 | − | − | − | ND | ND |

| NES mutants | ||||||

| M22 | 33 and 34 | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M23 | 35 and 36 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M24 | 37 and 38 | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M25 | 39 and 40 | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M26 | 43 and 44 | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M28 | 36 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| M19 | 41 | − | − | ++ | ND | ND |

| M21 | 42 | + | − | ++ | ND | ND |

| M4 | 45 | − | − | ++ | Nuclear export defect | ++ |

| M5 | 49 | − | − | ++ | ND | ND |

| M6 | 51 | ++ | ND | ++ | ND | ND |

For the CAT assay: −, ≤10% wild-type activity; +, >20% wild-type activity; ++, >70% wild-type activity. For the other (qualitative) assays: −, no activity; +, partial activity; ++, wild-type activity; ND, not determined. Shuttling and multimerization phenotypes were determined with GFP fusion proteins and complementation.

RNA binding may play an important role in ERev-dependent alternative splicing. In vivo and in vitro, ERev binds an RNA that overlaps with exon 3 (2, 21, 40). This binding could interfere directly or indirectly with a group of serine/arginine-rich splicing factors that bind an exonic splicing enhancer within exon 3 (21). In this study, we demonstrated that the NES of ERev is not involved in exon skipping and identified a single charged cluster involved in alternative splicing. Since this cluster also mediates RNA export, an activity common to the two functions is probably altered in the M27 mutant. Based on experiments with GFP fusions, M27 is competent for multimerization, nuclear localization, and protein export. Hence, RNA binding is a likely activity altered by the M27 mutant. We have not isolated a mutant that affects only alternative splicing, but it remains a possibility that other ERev residues or M27 interacts directly with the splicing machinery to cause exon skipping.

Alternative splicing in EIAV likely serves as an autoregulatory mechanism for ERev. Skipping of exon 3 produces an mRNA that cannot code for ERev, and this event is ERev dependent. This process may serve to regulate the levels of ERev during infection. In contrast, ETat is expressed from both constitutive and alternative mRNAs. ETat expression may be affected if the two mRNAs have different translation efficiencies or stabilities. A feedback loop has been proposed for HIV-1 Rev (11). Cellular examples of proteins affecting the alternative splicing of their own pre-mRNAs include SRp20, hnRNP A1, and Clk1 (5, 8, 27). Other splicing proteins antagonize the effects of SRp20 and hnRNP A1 (5, 27). It will be of interest to determine the cellular factors that are involved in ERev-dependent alternative splicing in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Hope Laboratory and Aram Mangasarian for discussion, John Donello for critical reading of the manuscript, and Arlyne Beeche for technical support. Allison Bocksruker, Leslie Barden, and Verna Stitt provided administrative support. Microscopy was performed at the James B. Pendleton microscope facility, and Fred Gage provided access to the confocal microscope. The anti-ERev and anti-EIAV p27gag sera were kind gifts of Nancy Rice (ABL-Basic Research Program, NCI-FCRDC). LMB was a kind gift of Barbara Wolf (Novartis Preclinical Research, Basel, Switzerland).

This material is based upon work supported under a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship to M.E.H. T.J.H. is supported in part by ARATA Brothers Trust and the Gene and Ruth Posner Foundation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI35477 to T.J.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beisel C E, Edwards J F, Dunn L L, Rice N R. Analysis of multiple mRNAs from pathogenic equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) in an acutely infected horse reveals a novel protein, Ttm, derived from the carboxy terminus of the EIAV transmembrane protein. J Virol. 1993;67:832–842. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.832-842.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belshan M, Harris M E, Shoemaker A E, Smith T A, Hope T J, Carpenter S. Biological characterization of Rev variation in equine infectious anemia virus. J Virol. 1998;72:4421–4426. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4421-4426.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogerd H P, Fridell R A, Benson R E, Hua J, Cullen B R. Protein sequence requirements for function of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Rex nuclear export signal delineated by a novel in vivo randomization-selection assay. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4207–4214. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll R, Derse D. Translation of equine infectious anemia virus bicistronic tat-rev mRNA requires leaky ribosome scanning of the tat CTG initiation codon. J Virol. 1993;67:1433–1440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1433-1440.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chabot B, Blanchette M, Lapierre I, La B H. An intron element modulating 5′ splice site selection in the hnRNP A1 pre-mRNA interacts with hnRNP A1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1776–1786. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham B C, Wells J A. High-resolution epitope mapping of hGH-receptor interactions by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Science. 1989;244:1081–1085. doi: 10.1126/science.2471267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derse D, Dorn P, DaSilva L, Martarano L. Structure and expression of the equine infectious anemia virus transcriptional trans-activator (tat) Dev Biol Stand. 1990;72:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan P I, Stojdl D F, Marius R M, Bell J C. In vivo regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing by the Clk1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5996–6001. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberhart D E, Malter H E, Feng Y, Warren S T. The fragile X mental retardation protein is a ribonucleoprotein containing both nuclear localization and nuclear export signals. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.8.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerman M, Vazeux R, Peden K. The rev gene product of the human immunodeficiency virus affects envelope-specific RNA localization. Cell. 1989;57:1155–1165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felber B K, Drysdale C M, Pavlakis G N. Feedback regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression by the Rev protein. J Virol. 1990;64:3734–3741. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3734-3741.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felber B K, Hadzopoulou C M, Cladaras C, Copeland T, Pavlakis G N. rev protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affects the stability and transport of the viral mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer U, Huber J, Boelens W C, Mattaj I W, Luhrmann R. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses an export pathway used by specific cellular RNAs. Cell. 1995;82:475–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer U, Sylvie M, Michael T, Corinne H, Reinhard L, Guy R. Evidence that HIV-1 Rev directly promotes the nuclear export of unspliced RNA. EMBO J. 1994;13:4106–4112. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj I W. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fridell R A, Benson R E, Hua J, Bogerd H P, Cullen B R. A nuclear role for the fragile X mental retardation protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:5408–5414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridell R A, Partin K M, Carpenter S, Cullen B R. Identification of the activation domain of equine infectious anemia virus rev. J Virol. 1993;67:7317–7323. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7317-7323.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz C C, Green M R. HIV Rev uses a conserved cellular protein export pathway for the nucleocytoplasmic transport of viral RNAs. Curr Biol. 1996;6:848–854. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukuda M, Asano S, Nakamura T, Adachi M, Yoshida M, Yanagida M, Nishida E. CRM1 is responsible for intracellular transport mediated by the nuclear export signal. Nature. 1997;390:308–311. doi: 10.1038/36894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuda M, Gotoh I, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Cytoplasmic localization of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase directed by its NH2-terminal, leucine-rich short amino acid sequence, which acts as a nuclear export signal. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20024–20028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gontarek R R, Derse D. Interactions among SR proteins, an exonic splicing enhancer, and a lentivirus Rev protein regulate alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2325–2331. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heaphy S, Dingwall C, Ernberg I, Gait M J, Green S M, Karn J, Lowe A D, Singh M, Skinner M A. HIV-1 regulator of virion expression (Rev) protein binds to an RNA stem-loop structure located within the Rev response element region. Cell. 1990;60:685–693. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90671-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hope T J, Bond B L, McDonald D, Klein N P, Parslow T G. Effector domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev and human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Rex are functionally interchangeable and share an essential peptide motif. J Virol. 1991;65:6001–6007. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6001-6007.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hope T J, Huang X, McDonald D, Parslow T. Steroid-receptor fusion of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: mapping cryptic functions of the arginine-rich motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7787–7791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hope T J, McDonald D, Huang X, Low J, Parslow T G. Mutational analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: essential residues near the amino terminus. J Virol. 1990;64:5360–5366. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5360-5366.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang X, Hope T J, Bond B L, McDonald D, Grahl K, Parslow T G. Minimal Rev-response element for type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1991;65:2131–2134. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.2131-2134.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jumaa H, Nielsen P J. The splicing factor SRp20 modifies splicing of its own mRNA and ASF/SF2 antagonizes this regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:5077–5085. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim F J, Beeche A A, Hunter J J, Chin D J, Hope T J. Characterization of the nuclear export signal of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Rex reveals that nuclear export is mediated by position-variable hydrophobic interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5147–5155. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le S Y, Malim M H, Cullen B R, Maizel J V. A highly conserved RNA folding region coincident with the Rev response element of primate immunodeficiency viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1613–1623. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis N, Williams J, Rekosh D, Hammarskjöld M L. Identification of a cis-acting element in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) that is responsive to the HIV-1 rev and human T-cell leukemia virus type I and II rex proteins. J Virol. 1990;64:1690–1697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1690-1697.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madore S J, Tiley L S, Malim M H, Cullen B R. Sequence requirements for Rev multimerization in vivo. Virology. 1994;202:186–194. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malim M H, Cullen B R. HIV-1 structural gene expression requires the binding of multiple rev monomers to the viral RRE: implications for HIV-1 latency. Cell. 1991;65:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90158-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malim M H, Cullen B R. Rev and the fate of pre-mRNA in the nucleus: implications for the regulation of RNA processing in eukaryotes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6180–6189. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malim M H, Hauber J, Le S Y, Maizel J V, Cullen B R. The HIV-1 rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNA. Nature. 1989;338:254–257. doi: 10.1038/338254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malim M H, McCarn D F, Tiley L S, Cullen B R. Mutational definition of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev activation domain. J Virol. 1991;65:4248–4254. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4248-4254.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malim M H, Tiley L S, McCarn D F, Rusche J R, Hauber J, Cullen B R. HIV-1 structural gene expression requires binding of the Rev trans-activator to its RNA target sequence. Cell. 1990;60:675–683. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90670-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mancuso V A, Hope T J, Zhu L, Derse D, Phillips T, Parslow T G. Posttranscriptional effector domains in the Rev proteins of feline immunodeficiency virus and equine infectious anemia virus. J Virol. 1994;68:1998–2001. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1998-2001.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martarano L, Stephens R, Rice N, Derse D. Equine infectious anemia virus trans-regulatory protein Rev controls viral mRNA stability, accumulation, and alternative splicing. J Virol. 1994;68:3102–3111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3102-3111.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer B E, Malim M H. The HIV-1 Rev trans-activator shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1538–1547. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer B E, Meinkoth J L, Malim M H. Nuclear transport of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, visna virus, and equine infectious anemia virus rev proteins: identification of a family of transferable nuclear export signals. J Virol. 1996;70:2350–2359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2350-2359.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer M E, Gronemeyer H, Turcotte B, Bocquel M T, Tasset D, Chambon P. Steroid hormone receptors compete for factors that mediate their enhancer function. Cell. 1989;57:433–442. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murphy R, Wente S R. An RNA-export mediator with an essential nuclear export signal. Nature. 1996;383:357–360. doi: 10.1038/383357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noiman S, Yaniv A, Tsach T, Miki T, Tronick S R, Gazit A. The Tat protein of equine infectious anemia virus is encoded by at least three types of transcripts. Virology. 1991;184:521–530. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olsen H S, Beidas S, Dillon P, Rosen C A, Cochrane A W. Mutational analysis of the HIV-1 Rev protein and its target sequence, the Rev responsive element. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:558–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olsen H S, Cochrane A W, Dillon P J, Nalin C M, Rosen C A. Interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev protein with a structured region in env mRNA is dependent on multimer formation mediated through a basic stretch of amino acids. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1357–1364. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olsen H S, Nelbock P, Cochrane A W, Rosen C A. Secondary structure is the major determinant for interaction of HIV rev protein with RNA. Science. 1990;247:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.2406903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ossareh N B, Bachelerie F, Dargemont C. Evidence for a role of CRM1 in signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science. 1997;278:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Otero, G. C., M. E. Harris, J. E. Donello, and T. J. Hope. Leptomycin B inhibits export of equine infectious anemia virus Rev and feline immunodeficiency virus Rev but not the function of the hepatitis B virus posttranscriptional regulatory element. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Palmeri D, Malim M H. The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 posttranscriptional trans-activator Rex contains a nuclear export signal. J Virol. 1996;70:6442–6445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6442-6445.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins A, Cochrane A W, Ruben S M, Rosen C A. Structural and functional characterization of the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1989;2:256–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stade K, Ford C S, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stephens R M, Derse D, Rice N R. Cloning and characterization of cDNAs encoding equine infectious anemia virus tat and putative Rev proteins. J Virol. 1990;64:3716–3725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3716-3725.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wen W, Meinkoth J L, Tsien R Y, Taylor S S. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell. 1995;82:463–473. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolff B, Sanglier J J, Wang Y. Leptomycin B is an inhibitor of nuclear export: inhibition of nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Rev protein and Rev-dependent mRNA. Chem Biol. 1997;4:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zapp M L, Hope T J, Parslow T G, Green M R. Oligomerization and RNA binding domains of the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus Rev protein: a dual function for an arginine-rich binding motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7734–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]