Summary

Docetaxel is the most commonly used chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer (PC), including castration-resistant disease (CRPC), but the eventual development of docetaxel resistance constitutes a major clinical challenge. Here, we demonstrate activation of the cholinergic muscarinic M1 receptor (CHRM1) in CRPC cells upon acquiring resistance to docetaxel, which is manifested in tumor tissues from PC patients post- vs. pre-docetaxel. Genetic and pharmacological inactivation of CHRM1 restores the efficacy of docetaxel in resistant cells. Mechanistically, CHRM1, via its first and third extracellular loops, interacts with the SEMA domain of cMET and forms a heteroreceptor complex with cMET, stimulating a downstream mitogen-activated protein polykinase program to confer docetaxel resistance. Dicyclomine, a clinically available CHRM1-selective antagonist, reverts resistance and restricts the growth of multiple docetaxel-resistant CRPC cell lines and patient-derived xenografts. Our study reveals a CHRM1-dictated mechanism for docetaxel resistance and identifies a CHRM1-targeted combinatorial strategy for overcoming docetaxel resistance in PC.

Keywords: acetylcholine, muscarinic receptor, prostate cancer, docetaxel resistance, CHRM1, dicyclomine, MAPK pathway, cMET

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

CHRM1 is activated in CRPC cells upon acquisition of resistance to docetaxel

-

•

CHRM1 is elevated in tumor tissues from prostate cancer patients after chemotherapy

-

•

CHRM1 interacts with cMET to induce a polykinase program for docetaxel resistance

-

•

CHRM1 inhibitor dicyclomine treatment overcomes docetaxel resistance

Wang et al. identify CHRM1 as a regulator of docetaxel resistance and aggressiveness in prostate cancer. CHRM1 is induced in prostate cancer cells and patient samples after chemotherapy. CHRM1 interacts with cMET to activate a downstream MAPK polykinase program. Inhibition of CHRM1 restores docetaxel responsiveness.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers, with more than 1 million annual new cases worldwide, making it a major global health issue.1 While initial treatments, including androgen deprivation therapy, often lead to a favorable response, most PC patients eventually enter into the terminal stage of the disease known as castration-resistant PC (CRPC).2 The first-line taxane-based chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel (DTX) currently remains a mainstay treatment for CRPC and improves patient survival.3 However, the disease inevitably develops resistance to DTX and progresses to a DTX-refractory state, leaving patients with very few therapeutic options afterward. Thus, there is a significant clinical need to understand the mechanisms associated with DTX resistance for devising a strategy to prolong DTX benefit in CRPC patients.

Recent evidence has uncovered the impact of cholinergic signaling and muscarinic receptors on PC growth, progression, and therapy response in both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous manners, mediated respectively by cancer-cell-intrinsic cholinergic muscarinic receptors and the extrinsic neural microenvironment.4,5 Highly expressed in PC clinical samples compared with all other cancer types, cholinergic muscarinic M1 receptor (CHRM1) supports PC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion.4,6,7 Amplification or gain of the CHRM1 gene is frequent in human CRPC and represents a worse prognostic factor for progression-free survival of PC patients.8 Autocrine activation of other cholinergic muscarinic receptors such as the M3 receptor (CHRM3) and M4 receptor (CHRM4) was also shown to promote the growth, migration, castration resistance, and neuroendocrine differentiation of PC cells.8,9,10 Further, a landmark study by Magnon et al. found that the parasympathetic nervous system utilizes stromal cholinergic fibers, predominantly via CHRM1 activated by the nerve-derived neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh), to promote PC invasion and metastasis.5 Nevertheless, although these earlier studies provided evidence for cholinergic signaling involvement in PC growth and progression, its role in mediating PC cell chemotherapeutic response and resistance has not been defined, nor has the mechanism been elucidated. In this study, we investigated the direct contribution of cholinergic signaling and muscarinic receptors to the development and maintenance of DTX resistance in PC and their targeting potential for overcoming DTX resistance in PC.

Results

CHRM1 expression is upregulated by DTX in PC

To associate cholinergic signaling with PC’s responsiveness to DTX, we used three pairs of human CRPC cell lines with or without acquired resistance to DTX, including DTX-resistant (DTXR) vs. DTX-sensitive (DTXS) 22Rv1, DU145, and PC-3, as established previously.11,12 We confirmed higher DTX IC50 values of all resistant cell lines compared with sensitive controls (Figure S1A). To determine if cholinergic signaling is altered in DTXR cells, we showed that all resistant cell lines secreted increased levels of ACh into the culture media, accompanied by upregulated protein expression of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), vesicular ACh transporter (VAChT), and CHRM1 compared with controls (Figures 1A, 1B, and S1B). Notably, we found that only CHRM1 mRNA among all five types of muscarinic receptors was uniformly upregulated in all resistant cell lines relative to controls (Figure S1C). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) also revealed upregulation of an ACh receptor activity gene ontology (GO) gene signature in 22Rv1DTXR cells relative to controls (Figure 1C). Thus, we decided to focus on CHRM1 as a possible key mediator of cholinergic signaling action in DTX response and resistance in PC cells. Accordingly, we grew subcutaneous tumor xenografts from resistant cell lines in immunocompromised mice and analyzed CHRM1 protein expression in xenografts. We demonstrated uniform increases in tumor CHRM1 protein expression in all resistant xenografts compared with controls by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 1D). The antibody specificity was validated in CHRM1-overexpression (OE) vs. control 22Rv1 tumor xenografts (Figure S1D). We further demonstrated that DTX induced ACh secretion and CHAT, VACHT, and CHRM1 mRNA to varied extents in DTX-naive 22Rv1 and DU145 cells (Figures 1E and 1F). These data suggest that cholinergic autocrine signaling is elevated in PC cells after DTX exposure.

Figure 1.

CHRM1 and associated cholinergic signaling are elevated by DTX in PC cells

(A) ELISA of ACh secretion into culture media from DTX-resistant and -sensitive cells (n = 3 biological replicates).

(B) Western blot of ChAT, VAChT, and CHRM1 in DTX-resistant and -sensitive cells.

(C) GSEA of a GO ACh receptor activity gene set for comparison of 22Rv1DTXR vs. 22Rv1DTXS cells.

(D) Representative CHRM1 IHC staining in DTX-resistant and -sensitive s.c. xenografts grown from respective cells. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(E) ELISA of ACh secretion into culture media from 22Rv1 and DU145 cells upon DTX treatment (1 nM, 48 h) (n = 3 biological replicates).

(F) qPCR of CHAT, VACHT, and CHRM1 in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells upon 1 nM DTX treatment for different times (n = 3 biological replicates). Data represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Next, we sought to find out how DTX induces ACh levels. In addition to increased ChAT and VAChT expression, we revealed upregulation of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in all DTXR cell lines and in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells exposed to DTX compared with controls (Figures S2A and S2B). This suggests that DTX induces ACh levels likely through accelerated synthesis of ACh rather than suppression of ACh degradation. To prove this hypothesis, we showed that knockdown (KD) of ChAT reduced ACh levels in the culture media of both DTXR cells and DTX-treated cells (Figures S2C and S2D). To further determine if other CRPC therapies alter cholinergic signaling and CHRM1 expression, we treated 22Rv1 and DU145 cells with cabazitaxel and mitoxantrone, two additional Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved chemotherapeutic drugs used against CRPC. We also treated androgen receptor (AR)-positive 22Rv1 cells with abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide, an androgen biosynthesis inhibitor and an AR inhibitor, respectively, which are both approved by the FDA for CRPC treatment. Intriguingly, we demonstrated that all these treatments induced ACh secretion and CHRM1 protein expression along with CHAT, VACHT, and ACHE mRNA increases to different extents in PC cells (Figures S3A‒S3C), suggesting that activation of cholinergic signaling and CHRM1 may be a universal cellular response to CRPC therapies.

Because the AR acts as the primary oncogenic driver of PC, we also examined the association of CHRM1 with AR in PC. Despite a previous report indicating that CHRM1 is a direct AR-repressed gene,13 we showed that CHRM1 protein was widely detected in a panel of human PC cell lines with no obvious association between CHRM1 expression levels and AR positivity (AR+: LAPC4, LNCaP, C4-2, C4-2B, 22Rv1; AR−: PC-3, LASCPC-01, NCI-H660; AR repressed: enzalutamide-resistant C4-2B [C4-2BENZR]) (Figure S4A). Interrogating public clinical datasets, we found a significant but weak positive correlation between CHRM1 mRNA and AR score14 in both TCGA primary PC and SU2C/PCF CRPC cohorts15 (Figure S4B).

In addition, we explored CHRM1’s association with neuroendocrine PC (NEPC), one of the most aggressive CRPC subtypes, which is now occurring with increasing frequency after clinical applications of highly potent AR signaling inhibitors.16 Using SYP to assess the extent of neuroendocrine differentiation in CRPC tumors (n = 6) by IHC, we identified a negative correlation between CHRM1 and SYP protein expression in p63-negative tumor cells (Figure S4C). CHRM1 mRNA also demonstrated a negative correlation with NEPC score14 in the SU2C/PCF CRPC cohort (Figure S4D). Further, CHRM1 mRNA levels were downregulated in NEPC patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) compared with adenocarcinoma (Adeno) PDXs (GSE32967, GSE66187, and GSE41192) (Figure S4E). Despite the relatively low CHRM1 expression in NEPC clinical samples, we demonstrated moderate-to-high levels of CHRM1 protein expression in C4-2BENZR and LASCPC-01 cells, which represent therapy-induced and de novo NEPC, respectively,17,18 and a marginal CHRM1 protein level in de novo NEPC NCI-H660 cells (Figure S4A), suggesting a heterogeneous expression pattern of CHRM1 in human NEPC cell lines.

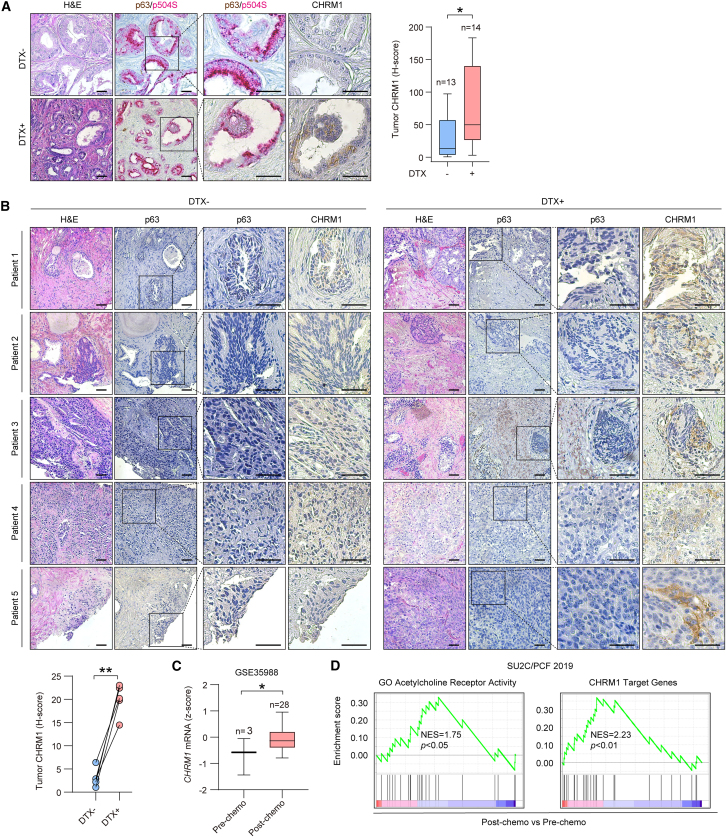

To evaluate CHRM1’s clinical association with DTX treatment, we first performed IHC on tumor samples from a previously established PC patient cohort.11 Of 27 patients in total, 14 had received neoadjuvant DTX chemotherapy before radical prostatectomy compared with 13 control patients without chemotherapy. Co-staining p63 and p504S19 to differentiate cancerous from benign lesions of prostate tumor tissues, we found elevated CHRM1 protein expression in p63-negative/p504S-positive cancerous areas of DTX-treated vs. untreated tumor samples in this cohort (Figure 2A). We also longitudinally collected primary tumor samples (n = 5) from PC patients post- vs. pre-DTX chemotherapy. We demonstrated increased CHRM1 protein expression in p63-negative malignant cells in post- vs. pre-DTX tumors in all cases (Figure 2B). Moreover, we revealed a higher CHRM1 mRNA level in tumor samples post- vs. pre-chemotherapy from a PC clinical dataset (GSE35988)20 (Figure 2C). Interrogating the SU2C/PCF CRPC dataset, we found that post-chemotherapy tumor samples were enriched in an ACh receptor activity gene set as well as a CHRM1 target gene signature, compared with pre-chemotherapy samples (Figure 2D). The CHRM1 targets were defined as the top 50 differentially expressed genes in dicyclomine- (Dic) vs. vehicle-treated 22Rv1DTXR cells. Dic (Bentyl) is a selective CHRM1 small-molecule inhibitor used clinically to treat irritable bowel syndrome.4,21 In contrast to CHRM1 upregulation, we further demonstrated decreased CHRM3 protein expression in p63-negative malignant cells of post- vs. pre-DTX tumors in all longitudinally collected cases (Figure S5A). Analyzing the same clinical PC dataset (GSE35988), we found no difference in CHRM3 mRNA levels between patient tumor samples post- and pre-chemotherapy (Figure S5B).

Figure 2.

CHRM1 is upregulated in post-chemotherapy PC patient samples

(A) Representative H&E and p63 (brown)/p504 (red) double and CHRM1 IHC staining and quantification in serial sections of tumor tissues from a cohort of PC patients with (DTX+, n = 14) and without (DTX−, n = 13) prior DTX chemotherapy. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(B) Representative H&E and p63 and CHRM1 IHC staining and quantification in serial sections of tumor tissues longitudinally collected from a cohort of PC patients (n = 5) pre- (DTX−) and post- (DTX+) DTX chemotherapy. Scale bars, 100 μm.

(C) Comparison of CHRM1 mRNA levels in human PC post- vs. pre-chemotherapy from GSE35988.

(D) GSEA of a GO ACh receptor activity gene set and a CHRM1 target gene signature for comparison of PC patient samples post- vs. pre-chemotherapy from the SU2C/PCF dataset. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Examining stromal CHRM1 expression in the above clinical samples, we found no significant changes in the levels of CHRM1 protein expressed in the stromal cells of post- vs. pre-DTX tumors from both cohorts (Figures S6A and S6B). Consistently, DTX treatment caused no changes in CHRM1 protein expression or ACh secretion in human prostatic stromal WPMY-1 and PCF-122,23 cells (Figures S6C and S6D). To further determine if nerve-derived ACh may contribute to CHRM1 signaling in the tumor epithelium by DTX, we co-stained tumor samples with VAChT and neuron-specific neurofilament-L (NF-L) to visualize intratumoral parasympathetic fibers. We demonstrated no significant changes in NF-L+/VAChT+ tumor-infiltrating nerve fiber density, as a correlative of nerve-derived ACh secretion, between post- and pre-DTX tumors after analyzing all cases (Figure S6E). Collectively, these results support the clinical relevance of CHRM1 induction by DTX in prostate epithelial tumors.

CHRM1 regulates DTX efficacy in PC cells

To elucidate CHRM1’s role in regulating DTX efficacy in PC cells, we stably overexpressed CHRM1 in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells and observed induction of cell growth (Figures 3A and S7A), consistent with its previously reported pro-proliferative effect.4,8 CHRM1 OE substantially reduced the anti-growth effect of DTX in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells (Figure 3A), rendering both partially resistant to DTX as shown by their DTX IC50 values compared with DTXR cells (Figure S7B). Alternatively, we used a DREADD (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drug)-based chemogenetic tool24 to specifically modulate CHRM1 receptor activity, given CHRM1’s nature as a Gαq-coupled G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). We engineered a 22Rv1 cell line stably expressing a synthetic Gαq-coupled CHRM1 DREADD (hM1Dq), which was developed based on CHRM1 and mutated to render it activatable solely by a synthetic ligand, clozapine N-oxide (CNO), instead of its natural ligand ACh.25 We found that induction of selective activation of hM1Dq by CNO in 22Rv1-hM1Dq cells downregulated DTX efficacy (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we observed that CHRM1 OE suppressed DTX-induced cell apoptosis with reductions in cleaved PARP1 and caspase 3 protein expression in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells (Figure 3C). Similarly, treatment with McN-A-343, a CHRM1-selective agonist, also attenuated DTX-induced cleavage of PARP1 and caspase 3 proteins in 22Rv1 cells (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

CHRM1 regulates DTX efficacy in PC cells

(A) Cell viability assays of control and CHRM1-OE 22Rv1 and DU145 cells upon DTX treatment for 48 h (n = 4 biological replicates), with CHRM1 OE validated by western blots.

(B) Cell viability assay of 22Rv1 cells expressing hM1Dq, a CHRM1-specific DREADD-Gαq construct, under pre-treatment with CNO (20 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX for 24 h (n = 4 biological replicates).

(C) Western blot of cleaved PARP1 and caspase 3 in control and CHRM1-OE 22Rv1 and DU145 cells treated with DTX (1 nM, 48 h).

(D) Western blot of cleaved PARP1 and caspase 3 in 22Rv1 cells treated with or without McN-A-343 (50 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX (1 nM, 48 h).

(E) Cell viability assays of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells pre-treated with or without Dic (25 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX for 48 h (n = 4 biological replicates).

(F) Soft-agar colony-formation assays of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells treated with 1 nM DTX together with or without 25 μM Dic for 48 h followed by a 2-week cell growth period (n = 3 biological replicates).

(G) Western blot of cleaved PARP1 and caspase 3 in 22Rv1 cells treated with or without Dic (10 or 25 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX (1 nM, 48 h).

(H) TUNEL assays of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells treated with or without Dic (25 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX (1 nM, 48 h) (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 200 μm. Data represent mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01.

Conversely, we attempted to inactivate CHRM1 in PC cells with the CHRM1 antagonist Dic. To this end, we first sought to confirm the suppressive effect of Dic on CHRM1-elicited cholinergic signaling in PC cells by measuring Ca2+ influx, a direct indicator of muscarinic receptor activation. We showed that CHRM1 OE or McN-A-343 triggered Ca2+ influx in 22Rv1 cells, which was abolished upon pre-treatment with Dic (Figures S7C and S7D), indicating Dic’s effectiveness in inhibiting CHRM1 activity. We further revealed a dose-dependent anti-growth effect of Dic in 22Rv1 cells, with an IC50 value of 66.2 μM. Based on this result, we chose to use Dic in the dose range of 6.25–25 μM, which had a negligible effect on cell growth within a 48-h observation period (Figure S7E). Dic enhanced DTX efficacy in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells (Figure 3E). Dic also led to decreases in DTX IC50 value in CHRM1-positive neuroendocrine-like C4-2BENZR and LASCPC-01 cells (Figure S7F). Concordantly, combined treatment with Dic and DTX resulted in greater repression of soft-agar colony formation of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells compared with DTX alone (Figure 3F). Dic treatment also augmented DTX-induced cleavage of PARP1 and caspase 3 and the percentage of TUNEL+ cells, indicative of greater apoptosis, in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells compared with DTX alone (Figures 3G and 3H). Together, these findings establish a role for CHRM1 in modulating response to DTX in PC cells.

CHRM1 confers DTX resistance and maintains the aggressive properties of DTX-resistant PC cells

Next, we examined whether CHRM1 influences DTX efficacy under a resistant state. Consistent with CHRM1 induction in DTXR relative to sensitive cells, Dic had a greater anti-growth effect in resistant than in sensitive 22Rv1 cells (Figure S8A). Combined with DTX, Dic enhanced DTX efficacy in all DTXR cell lines (Figure 4A). However, unlike Dic, the non-selective muscarinic agonist carbachol or the non-selective muscarinic antagonist scopolamine in combination with DTX did not significantly affect DTX efficacy in 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells (Figure S8B). Despite upregulation of CHRM4 transcripts (Figure S1C) and protein (Figure S8C) in 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells compared with sensitive counterparts, we did not see a significant effect of the CHRM4-selective antagonist tropicamide in altering DTX efficacy in these resistant cells (Figure S8D). Moreover, we showed that combined treatment with Dic and DTX diminished soft-agar colony formation of all resistant cell lines compared with DTX alone (Figure 4B). Complementing these findings reliant on a pharmacological inhibitory approach, we found that stable KD of CHRM1 using two separate small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) also reduced the growth and colony formation of 22Rv1DTXR cells (Figures 4C and 4D). We also demonstrated increases in TUNEL+ apoptotic cell percentages in all resistant cell lines concurrently exposed to DTX and Dic compared with DTX alone (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

CHRM1 confers DTX resistance in PC cells

(A) Cell viability assays of DTXR PC cells treated with or without Dic (25 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX for 48 h (n = 4 biological replicates).

(B) Soft-agar colony-formation assays of DTXR PC cells treated with DTX (22Rv1DTXR, 3 nM; DU145DTXR and PC-3DTXR, 12 nM) together with or without 25 μM Dic (n = 3 biological replicates).

(C) Cell proliferation assays of control and CHRM1-KD 22Rv1DTXR cells within a 5-day observation period (n = 4 biological replicates). Fold change on the day of cell seeding (day 0) in each group was set as 1.

(D) Soft-agar colony-formation assays of control and CHRM1-KD 22Rv1DTXR cells (n = 3 biological replicates).

(E) TUNEL assays of DTXR PC cells treated with DTX together with or without Dic (25 μM, 48 h) (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 200 μm.

(F) Representative images and quantification of tumorspheres formed by DTXR PC cells treated with DTX together with Dic (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(G) Representative images and quantification of tumorspheres formed by control and CHRM1-KD 22Rv1DTXR cells (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 50 μm.

(H) Wound-healing assays of PC-3DTXR cells exposed to 12 nM DTX together with or without 25 μM Dic within a 48-h observation period (n = 4 biological replicates). Scale bars, 200 μm.

(I) Representative images and quantification of 22Rv1DTXR and PC-3DTXR cells migrating to or invading the lower surface of inserts in Transwells stained by crystal violet under DTX together with or without 25 μM Dic (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 25 μm.

(J) Representative images and quantification of Transwell assays of control and CHRM1-KD 22Rv1DTXR cells as similarly described in (I) (n = 3 biological replicates). Scale bars, 25 μm. Data represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01; ns, not significant.

To further test whether CHRM1 regulates malignant cellular behavior in a DTX-refractory setting, we assessed sphere-forming capacity and migration/invasion in resistant cells upon CHRM1 inactivation, which are respectively indicative of stemness properties and metastatic potential, two aggressive features commonly associated with the emergence of DTX resistance.26 We found that Dic-treated cells in all resistant lines formed fewer spheres compared with controls, with dose-dependent reductions in sphere numbers further observed in DU145DTXR and PC-3DTXR cells (Figure 4F). CHRM1 KD also limited tumorsphere establishment, with fewer 22Rv1DTXR cell spheres compared with controls (Figure 4G). Wound-healing assays revealed less cell migration of PC-3DTXR upon combination treatment with DTX and Dic at two consecutive observation time points compared with DTX alone (Figure 4H). Transwell assays also demonstrated less migration and invasion of 22Rv1DTXR and PC-3DTXR cells caused by DTX in the presence of Dic compared with DTX alone (Figure 4I), which was corroborated by less migration of 22Rv1DTXR cells upon loss of CHRM1 relative to controls (Figure 4J). Altogether, these results support the conclusion that CHRM1 is critical for the maintenance of DTX resistance and associated aggressive cellular behavior.

CHRM1 promotes downstream MAPK signaling in a cMET-dependent manner

To dissect the mechanism by which CHRM1 drives the growth and survival of PC cells under DTX-treated and -resistant conditions, we first performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis with Dic- vs. vehicle-treated 22Rv1DTXR cells. GSEA identified several cell-cycle-related hallmark gene sets negatively enriched in Dic-treated cells relative to controls, congruent with the inhibition of 22Rv1DTXR cell growth upon CHRM1 inactivation and DTX in combination (Figure 5A). Muscarinic receptors are known to signal through multiple downstream signaling cascades, including mitogenic pathways, in a G-protein-dependent or -independent manner.27 Indeed, we found a gene set related to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family signaling cascade highly enriched in 22Rv1DTXR vs. 22Rv1DTXS cells (Figure 5B). We further demonstrated that CHRM1 OE activated several principal MAPK family member proteins, including c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in 22Rv1 but not DU145 cells. Conversely, pre-treatment with Dic reverted phosphoprotein levels of JNK and p38 in 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells and ERK in 22Rv1DTXR cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

CHRM1 activates a polykinase program to confer DTX resistance in PC cells

(A) GSEA of all hallmark gene sets negatively enriched in Dic- (25 μM, 72 h) vs. vehicle-treated 22Rv1DTXR cells with significance.

(B) GSEA of a Reactome MAPK family signaling cascades gene set for comparison of differentially expressed genes in 22Rv1DTXR vs. 22Rv1DTXS cells.

(C) Western blots of select MAPKs as indicated in control and CHRM1-OE 22Rv1 and DU145 cells and in 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells treated with or without Dic (25 μM, 30 min).

(D) Cell proliferation assays of 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells upon treatment with SP600125 (5 μM, JNK inhibitor), SB203580 (10 μM, p38 inhibitor), and/or SCH772984 (100 nM, ERK inhibitor) alone or in different combinations during an observation period for up to 7 days (n = 3 biological replicates). Fold change on the day of cell seeding (day 0) in each group was set as 1.

(E) Soft-agar colony-formation assays of 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells upon treatment with 5 μM SP600125, 10 μM SB203580, and/or 100 nM SCH772984 alone or in different combinations (n = 3 biological replicates). Data represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

To examine whether the MAPK polykinase stimulated by CHRM1 is functionally significant, we subjected 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells to individual application and different independent combinations of well-characterized inhibitors of ERK (SCH772984), JNK (SP600125), and p38 (SB203580). We demonstrated that individual inhibition of ERK, JNK, and p38 effectively attenuated the growth and colony formation of 22Rv1DTXR cells, with stronger reductions observed by combined inhibition of any two kinases, compared with controls. Even more appealing, combined inhibition of all three MAPKs completely abrogated 22Rv1DTXR cell growth. Similarly, inhibition of JNK and p38 individually resulted in slower growth and few colonies formed by DU145DTXR cells compared with controls, with combined inhibition nearly halting the growth of DU145DTXR cells (Figures 5D and 5E). To further validate MAPKs as real mediators of CHRM1 function, we showed that enforced expression of ERK,28 JNK,29 or MKK6, as a selective activator of p3830 with constitutive activity and proven ability to rescue the growth of DTXR cells suppressed by corresponding kinase inhibitors (Figures S9A and S9B), individually restored the Dic-repressed growth of 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells to different extents (Figure S9C). These data in aggregate suggest that CHRM1 confers DTXR aggressive properties in part through a network of downstream MAPK kinases.

We next addressed how CHRM1 is mechanistically linked to downstream MAPK activation. To this end, we first attempted to discern whether CHRM1 confers DTX resistance through Gq protein- and β-arrestin-2-dependent pathways, since CHRM1 is known to couple with Gq and recruit β-arrestin-2 to mediate CHRM1-induced GPCR signaling.31,32 Inactivation of Gq protein with YM-254890, a Gq-selective inhibitor,33 as confirmed by a reduction in CHRM1-induced Ca2+ influx and lessened PKCα/PKCδ protein phosphorylation, or β-arrestin-2 KD, as confirmed by decreased β-arrestin-2 and p-ERK protein levels, failed to revert CHRM1’s suppressive effect on DTX efficacy in 22Rv1 cells (Figures S10A‒S10D). Similarly, treatment with YM-254890 or β-arrestin-2 siRNA, accompanied by reductions in Ca2+ influx and PKCα/PKCδ/ERK phosphoprotein levels, did not produce a substantial anti-growth effect comparable to that of Dic in 22Rv1DTXR cells (Figures S10B, S10C, S10E, and S10F). Further, prior incubation of 22Rv1-hM1Dq cells with YM-254890, which abolished CNO-induced Ca2+ influx, or β-arrestin-2 siRNA had no significant rescuing effect on DTX efficacy diminished by CNO-induced hM1Dq activation (Figures S10G and S10H). Together, these data suggest that CHRM1 is not likely to rely on a G-protein- or arrestin-dependent mechanism to regulate DTX response and resistance in PC cells.

Mounting evidence has indicated the capability of GPCRs to engage in crosstalk with receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) on the cell surface for RTK transactivation and growth-promoting signals.34 RTKs have a well-established contributory role in regulating cancer cell resistance to different types of drug therapies, including chemotherapeutic agents.35,36 Thus we speculated that CHRM1 might utilize a mechanism integrating an RTK to trigger downstream intracellular MAPK signaling. Using a candidate approach, we found that cMET, an RTK enhanced in chemoresistant cells and implicated in driving chemoresistance of several cancer types,35 was significantly downregulated, with lower phosphoprotein levels upon Dic treatment in all DTXR cell lines (Figure 6A). Complementing Dic treatment, CHRM1 OE and McN-A-343 activation of CHRM1 in 22Rv1 cells and CNO induction of hM1Dq in 22Rv1-hM1Dq cells promoted cMET protein phosphorylation, while CHRM1 KD reduced cMET phosphoprotein levels in 22Rv1DTXR cells (Figure S11A). To examine whether cMET has an impact on MAPK signaling in a DTXR condition, we demonstrated that inhibition of cMET with SGX-523, a selective and potent cMET inhibitor,37 time-dependently diminished ERK, JNK, and p38 protein phosphorylation in 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells (Figure 6B). Moreover, we found that treatment with SGX-523 restored the anti-growth efficacy of DTX impaired by CHRM1 OE in 22Rv1 cells and by CNO-induced hM1Dq in 22Rv1-hM1Dq cells (Figures 6C and 6D). GPCRs have been reported to transactivate RTKs, either in an RTK ligand-dependent manner by activating a metalloprotease to facilitate the proteolytic cleavage of an RTK pro-ligand to generate a mature ligand or in an RTK ligand-independent manner by triggering the formation of a GPCR-RTK heteroreceptor complex.34 To further characterize how CHRM1 transactivates cMET, we used GM6001, a broad-spectrum matrix metalloprotease (MMP) inhibitor, to block MMP-mediated pro-HGF conversion to mature HGF as reported previously,38 a cognate ligand for cMET activation.39 Unlike Dic or SGX-523, both largely diminishing the soft-agar growth of 22Rv1DTXR cells, we showed that GM6001 slightly repressed 22Rv1DTXR growth but did not reach significance (p = 0.051) (Figure S11B), which was paralleled by the observation that GM6001 did not affect CHRM1-induced phosphorylation of cMET or select MAPK members (Figure S11C). HGF secretion levels also remained indifferent in 22Rv1DTXR cell culture medium upon Dic treatment (Figure S11D). These data suggest that CHRM1 transactivates cMET with no requirement of a cMET ligand, which led us to pursue the likelihood of CHRM1-cMET physical crosstalk underlying cMET transactivation.

Figure 6.

CHRM1 transactivates cMET to promote the MAPK pathway for maintenance of DTX resistance

(A) Western blot of p-cMET in DTXR PC cells treated with or without Dic (25 μM, 30 min).

(B) Western blot of p-cMET and select p-MAPKs, as indicated, in 22Rv1DTXR and DU145DTXR cells upon 5 μM SGX-523 treatment for 0.5 or 1 h.

(C) Cell viability assays of control and CHRM1-OE 22Rv1 cells treated with or without SGX-523 (5 μM, 24 h) followed by DTX for 48 h (n = 4 biological replicates).

(D) Cell viability assays of 22Rv1-hM1Dq cells treated with 20 μM CNO in the absence or presence of 5 μM SGX-523 for 24 h followed by DTX for 24 h (n = 4 biological replicates).

(E) Representative PLA staining of CHRM1-cMET interaction and quantification of per-cell cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity in 22Rv1DTXR cells treated with or without Dic (10 μM, 30 min) followed by carbachol (CCh) stimulation (10 μM, 30 min). cMET antibody incubation alone served as negative control. Scale bars, 20 μm.

(F) A coIP assay of CHRM1-cMET interaction in PC-3DTXR cells treated with or without Dic (25 μM, 30 min). IgG was used in the IP step as the negative control. Ten percent input was blotted as the positive control.

(G) Computational docking of the bound conformation of CHRM1 and cMET extracellular regions, where CHRM1 and cMET are displayed in red and gray, respectively. The CHRM1-cMET complex is also shown in ribbon mode from the same angle view as in the bound conformation, with the extracellular contact residues of CHRM1 indicated in black.

(H) A coIP assay of CHRM1-cMET interaction in COS-1 cells upon co-transfection of cMET with wild-type (WT) or mutant CHRM1 as indicated. IgG was used in the IP step as the negative control. Ten percent input was blotted as the positive control.

(I) Western blot of p-cMET in COS-1 cells co-transfected with cMET with WT or different mutant CHRM1. Data represent mean ± SD. ∗∗p < 0.01.

To test this idea, we first carried out an in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) and visualized an endogenous CHRM1-cMET protein complex in 22Rv1DTXR cells. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence restricted to the cytoplasm revealed an increase in CHRM1-cMET interaction upon carbachol treatment, which was reversed under pre-treatment with Dic, compared with controls (Figure 6E). A co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) assay confirmed CHRM1-cMET interaction in PC-3DTXR cells, which was diminished in the presence of Dic (Figure 6F). Furthermore, we introduced a FLAG-tagged hM1Dq expression construct into 22Rv1 cells and found that cMET co-precipitated with FLAG-hM1Dq in cells upon CNO treatment compared with controls (Figure S11E). These results suggest a physical interaction between CHRM1 and cMET with interaction strength dependent on CHRM1 receptor activity.

To gain further insight into how CHRM1 induces cMET transactivation via formation of a CHRM1-cMET complex, we sought to map the protein region(s) and residue(s) on CHRM1 that participate in direct physical contact with cMET. CHRM1 exhibits a typical GPCR protein architecture consisting of seven transmembrane helices linked by three intracellular loops and three extracellular loops (ECL1–3).40 cMET has an N-terminal semaphorin (SEMA) domain in the extracellular region, which is responsible for HGF binding to activate cMET.41 Based on our findings that CHRM1 could transactivate cMET in a ligand-independent manner, we speculated that upon agonist binding CHRM1 may act as a “ligand” via its extracellular region to interact with the cMET SEMA domain for cMET activation. To prove this hypothesis, we utilized a computational protein-protein docking approach with MOE (Molecular Operating Environment)42 to predict the conformation of CHRM1-cMET binding via their extracellular segments, whose structures were predicted by AlphaFold 2 with a high similarity to those elucidated by cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) for matched regions (PDB: 7MO8 and 6OIJ for cMET and CHRM1, respectively).40,41 The top-ranked docking pose has the most extracellular residues of CHRM1, including L167 in ECL1 and C391, C394, and P396 in ECL3, predicted to contact the bottom surface of the cMET SEMA domain (Figure 6G). To validate the CHRM1-cMET binding mode, we designed individual amino acid mutations for the four CHRM1 residues predicted to interface with cMET and introduced CHRM1 mutants and cMET into COS-1 cells. A coIP assay revealed that mutations of any of three residues (L167A, C391A, and P396A), but not C394, diminished CHRM1-cMET binding to different extents, which was concurrently associated with decreases in cMET protein phosphorylation (Figures 6H and 6I). These data support a model in which CHRM1 physically interacts with cMET via formation of extracellular contacts between CHRM1 ECLs and the cMET SEMA domain for cMET transactivation.

In addition, we examined other potential signaling intermediaries bridging CHRM1 to cMET stimulation, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the protein kinase Src.43,44,45,46 We found that treatment with the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib or a Src inhibitor (Src inhibitor 1) had a minimal effect on soft-agar growth of 22Rv1DTXR cells in contrast to the substantial growth blockade by Dic or SGX-523, implying that CHRM1 might transactivate cMET independent of EGFR and Src (Figure S11B). Collectively, these results suggest that CHRM1 regulates DTX response and resistance through cMET-dependent activation of multiple MAPKs.

Pharmacological inhibition of CHRM1 restores DTX efficacy and restricts DTX-resistant tumor growth in pre-clinical in vivo models

To address whether our findings above on CHRM1 modulation of DTX response and resistance in PC cell cultures could be translated in vivo, we established multiple PC xenograft mouse models to evaluate the effect of CHRM1 antagonism exemplified by Dic on DTX efficacy in both naive and resistant tumors. We selected for our in vivo experiments a Dic dose of 8 mg/kg, which falls on the lower side of the Dic dose range (2–40 mg/kg) commonly applied in various mouse studies of neurocognitive disorders47,48,49,50,51 but has a proven phenotypic effect in Alzheimer’s disease mice.52 We first inoculated male immunocompromised mice subcutaneously (s.c.) with 22Rv1 cells and treated them with DTX alone and in combination with Dic. Mice receiving saline or Dic had similar tumor growth curves and were euthanized on day 12 due to their large tumors. Given that DTX effectively slowed tumor growth at the initial intervention stage, we continued DTX treatment with and without Dic on the remaining mice for another 8 days. We demonstrated that a combination of DTX with Dic suppressed tumor growth more dramatically than DTX alone, as evidenced by smaller tumor volume and lower tumor weight at the endpoint on day 20 (Figures 7A–7C). In agreement with tumor growth profiles, IHC analyses revealed a significant drop in Ki-67+ cell percentage and an increase in cleaved caspase 3+ cell percentage in tumors co-treated with DTX and Dic compared with DTX-treated tumors (Figure S12A). We further found that combined treatment with Dic and DTX did not affect mouse body weight compared with DTX alone (Figure S12B).

Figure 7.

Pharmacological inhibition of CHRM1 enhances DTX efficacy and overcomes DTX resistance in prostate tumors in mice

(A) Growth curves of 22Rv1 s.c. tumors receiving saline as vehicle (Veh, daily), DTX (10 mg/kg, once a week), Dic (8 mg/kg, daily), and DTX + Dic in male nude mice (n = 8 tumors).

(B) Tumor weights measured for each group in (A) at respective endpoints.

(C) Anatomic images of tumors from each group in (A) at the respective endpoints.

(D) Growth curves of 22Rv1DTXR s.c. tumors receiving Veh, DTX, Dic, and DTX + Dic in male NSG mice (n = 8 tumors).

(E) Tumor weights measured for each group in (D) at the endpoint.

(F) Anatomic images of tumors from each group in (D) at the endpoint.

(G) Growth curves of PC-3DTXR s.c. tumors receiving Veh, DTX, Dic, and DTX + Dic in male nude mice (n = 10–12 tumors).

(H) Tumor weights measured for each group in (G) at the endpoint.

(I) Anatomic images of tumors from each group in (G) at the endpoint.

(J) Growth curves of LuCaP 147CR s.c. PDX tumors receiving Veh, DTX, Dic, and DTX + Dic in castrated male NSG mice (n = 6 tumors).

(K) Tumor weights measured for each group in (J) at the endpoint.

(L) Anatomic images of tumors from each group in (J) at the endpoint.

(M) Representative IHC staining of Ki-67, cleaved caspase 3, and p-cMET in resistant tumor samples from each group in (D), (G), and (J). Scale bars, 20 μm.

(N) Quantification of percentage of Ki-67+ and cleaved caspase 3+ cells and per-cell p-cMET staining intensity in resistant tumor samples from each group in (D), (G), and (J) (n = 3 tumors). Data represent mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Next, we established subcutaneous xenografts in mice with DTXR cells, 22Rv1DTXR and PC-3DTXR. Intriguingly, we found that Dic itself had a marginal anti-tumor effect on resistant tumors, which could be possibly due to administration of Dic at a potentially sub-optimal anti-tumor dose. However, combined treatment with Dic and DTX resensitized resistant tumors to DTX and significantly inhibited the growth of both 22Rv1DTXR and PC-3DTXR tumors compared with the groups treated with DTX alone (Figures 7D–7I). We further examined whether targeting CHRM1 with Dic restores DTX sensitivity in a PDX model. To this end, we generated a LuCaP 147CR PDX xenograft model that represents a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and does not respond to castration and DTX, as reported previously.53 We demonstrated that neither DTX nor Dic altered LuCaP 147CR tumor growth compared with the control group, while the combination of DTX and Dic significantly reduced tumor growth compared with the group treated with DTX alone (Figures 7J‒7L).

Analyses of resistant tumor samples by IHC revealed a prevalent reduction in Ki-67+ cell percentages and rises in cleaved caspase 3+ cell percentages in resistant tumors treated with both DTX and Dic compared with DTX alone (Figures 7M and 7N). Moreover, we demonstrated reduced p-cMET staining in resistant tumors co-treated with DTX and Dic compared with DTX alone (Figures 7M and 7N). In addition, we found no alterations in mouse body weight between the groups treated with DTX and Dic in combination and those treated with DTX alone in all resistant xenograft studies (Figures S11C‒S11E). Collectively, these findings suggest that CHRM1 targeting has significant potential for combinational use with DTX to boost DTX efficacy and overcome DTX resistance in prostate tumors.

In summary, our data integrating both in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical studies support the conclusion that CHRM1-induced cholinergic signaling is critical for the development and maintenance of DTX resistance in CRPC cells, mechanistically mediated in part by activation of a MAPK polykinase program in a cMET-dependent manner. These findings provide therapeutic opportunities for repurposing CHRM1 antagonists in combination with DTX to improve chemotherapeutic response in PC.

Discussion

In this study, we presented evidence that muscarinic ACh autocrine signaling is elevated in CRPC after exposure to or acquisition of resistance to DTX, which suppresses DTX efficacy and confers DTX resistance in CRPC cells via activation of CHRM1. Importantly, we demonstrated that CHRM1 antagonism in conjunction with DTX enhanced DTX efficacy and effectively restricted the growth of several DTXR lines of CRPC cells and xenografts, including a PDX, which provides a rationale for repositioned use of anti-CHRM1 agents, such as Dic, in combination with DTX for improved chemotherapeutic benefits in PC. Despite these CHRM1-centric findings, we are aware that additional studies might be needed to explore the potential roles of other muscarinic receptors, especially those reported to have a function in PC and activated in select DTXR PC cell lines (e.g., CHRM3 and CHRM4), in modulating chemotherapeutic effects in PC. Although our data imply that CHRM3 and CHRM4 might not exert an anti-DTX effect as strong as CHRM1, future efforts should be considered to more comprehensively determine their functional significance in PC DTX chemotherapy.

Other than DTX, we demonstrated prevalent increases in CHRM1 expression by other CRPC therapies, including AR signaling inhibitors and additional chemotherapeutic agents, which raises a possibility that CHRM1 might be activated through a ubiquitous mechanism upon therapeutic pressure. Since previous studies have well established the central role of cancer stem cells in the development of resistance to various therapies in PC,54,55 one top candidate universal mechanism of CHRM1 upregulation in response to CRPC therapies including DTX could be under the control of molecular stemness determinants such as the Yamanaka factors, as supported by our data indicating the necessity of CHRM1 for maintenance of the stem-like sphere-forming capacity of DTXR cells. Further investigation is warranted to test the speculation that CHRM1 could be activated by stemness factors. Thus, upregulation of CHRM1 is likely attributable to a simple selection process whereby non-stem CHRM1-low expressors are eliminated, while stem-like CHRM1-high expressors are expanded along with therapy. In addition, alternative mechanisms possibly contributing to CHRM1 upregulation, especially those in response to chemotherapy-induced DNA damage, cellular stress, and epigenetic reprogramming of PC cells, also merit further exploration.

A salient mechanistic finding of our study is that CHRM1 appears to primarily utilize crosstalk with the cMET RTK rather than a GPCR canonical mechanism involving G protein or β-arrestins to maintain PC growth and survival under DTX chemotherapy. cMET signaling is often enriched in chemoresistant cells of a variety of cancer types as a result of its OE or ligand-independent constitutive activation.35 It is thus tempting to speculate that the potential DTX-induced abundance or overreactivity of cMET may facilitate CHRM1 interaction with cMET as a more potent trigger than GPCR canonical signaling for activating the downstream MAPK pathway to support PC growth under DTX chemotherapy. On the other hand, how and to what extent G proteins including Gαq and Gα11 function, eliciting mitogenic signals like the MAPK pathway, under chemotherapeutic stress relative to a regular state remains unclear and might likely account for CHRM1’s preference for cMET over G-protein-mediated signaling to modulate DTX efficacy. Nevertheless, we argue that the G-protein/β-arrestin-mediated canonical and RTK-involving non-canonical mechanisms may both contribute to CHRM1’s effect in PC, with the non-canonical signaling likely outcompeting the canonical under DTX chemotherapy in our models. Further in-depth studies with additional models are needed to fully evaluate the potential role and extent of participation of canonical GPCR signaling in mediating CHRM1’s impact on DTX response and resistance in PC cells.

Our mechanistic studies indicate that CHRM1 activates cMET via formation of a CHRM1-cMET protein complex with their binding affinity modulated by CHRM1 receptor activity under the influence of CHRM1 agonists and antagonists. Other than endogenously expressed CHRM1, our data using the DREADD system signify a co-existence of hM1Dq stimulation of cMET as well as pre-designed hM1Dq activation of canonical Gq signaling in 22Rv1-hM1Dq cells, which reinforces our inference that CHRM1 may regulate DTX response and resistance in PC cells mainly through cMET, even in the presence of activated Gq signaling. Our computational docking and mutagenesis analyses further revealed several CHRM1 residues in ECLs, including L167 in ECL1 and C391/P396 in ECL3, responsible for CHRM1 interaction with the cMET ligand-binding SEMA domain and concomitant activation of cMET. This suggests a model in which, upon agonist binding, CHRM1 adopts a confirmational state favorable for utilizing these residues as a pseudo ligand to make direct contacts with the cMET receptor for cMET activation. These molecular insights into understanding the CHRM1-cMET interactive mode may also potentially indicate the molecular basis for the formation of a GPCR-RTK heteroreceptor complex as widely noted in previous studies.34

Limitations of the study

Our study has several limitations. First, we focused on the role and targeting potential of CHRM1-directed muscarinic ACh signaling for improved DTX chemotherapeutic outcome solely in PC cells, with no examination of their effects on the stroma, especially the immune microenvironment. Although we observed no significant differences in stromal CHRM1 expression and parasympathetic nerve fiber density in our clinical samples post- vs. pre-DTX, this was a small number of samples. Since the parasympathetic nerves have been well known to promote PC by releasing ACh to stimulate CHRM1 on stromal cells,5 our study would be strengthened by elucidating the potential impact of stromal or microenvironmental factors such as stromal CHRM1 or neuronal ACh signaling on the cell-autonomous ACh-CHRM1 signaling and effectiveness of CHRM1 antagonism using large clinical cohorts and extended pre-clinical models. We also overly relied on xenograft mouse models deficient in an adaptive immune system to determine Dic’s efficacy for enhancing DTX chemotherapy. Given a recent study reporting that parasympathetic innervation modulates tumor immunity, including PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in breast cancer,56 additional studies factoring in potential immune modulation of combined DTX and Dic against PC in an immunocompetent mouse model are needed. Second, we used only a single dose of Dic and DTX each to assess their independent and combined effects on tumor growth and molecular changes. This would be strengthened by inclusion of various doses of each agent to determine dose-dependent effects and combination synergy as a more rigorous experimental approach. Third, we showed enhancement of cancer-cell-intrinsic neural lineage plasticity as exemplified by induction of the neurotransmitter ACh release and several key genes of the ACh system, including CHRM1, in DTXR cells, which is in line with recent discoveries of aberrant activation of neural lineage genes and signaling in PC cells upon acquisition of resistance to therapy such as enzalutamide.57 Although we did not follow up on this intriguing finding, beyond the focus of the present study on CHRM1 and related muscarinic ACh signaling, future pursuit of cancer-cell-intrinsic neural lineage genes connected with PC chemoresistant phenotypes undoubtedly merits investigation and will provide an understanding of PC chemotherapy resistance from a neural perspective. Last, given a wide range of prior studies already proposing CHRM1 as a therapeutic target in PC, our study would be strengthened by adding parallel comparisons of CHRM1’s role and anti-CHRM1’s effect in different PC contexts, including chemotherapy response and other phenotypic and therapeutic aspects, which might provide insights and likely conceptual advances in understanding CHRM1’s particular importance in PC and the precise application of CHRM1 targeting as a PC therapy.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-AChE | Proteintech | Cat# 17975-1-AP; RRID: AB_2242349 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CHRM4 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SAB4300824 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ChAT | Abcam | Cat# ab181023; RRID: AB_2687983 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CHRM1 (for IHC and PLA) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# HPA014101; RRID: AB_1854210 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CHRM1 (for immunoblots) | Abcam | Cat# ab180636 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase 3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9661; RRID: AB_2341188 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved PARP1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9541; RRID: AB_331426 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-cMET (for PLA) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8741; RRID: AB_11127596 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-cMET (for co-IP and immunoblots) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8198; RRID: AB_10858224 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-ERK1/2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-514302; RRID: AB_2571739 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Gαq | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-365906; RRID: AB_10842057 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-JNK | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9252; RRID: AB_2250373 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki-67 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9027; RRID: AB_2636984 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NF-L | Proteintech | Cat# 60189-1-Ig; RRID: AB_10860271 |

| Normal rabbit IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2729; RRID: AB_1031062 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-cMET (Tyr1234/1235) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3077; RRID: AB_2143884 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-p38 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8690; RRID: AB_10999090 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-phospho-ERK (Tyr204) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-7976; RRID: AB_2297323 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4668; RRID: AB_823588 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4511; RRID: AB_2139682 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-PKCα (Thr638) | Proteintech | Cat# 29123-1-AP; RRID: AB_2918239 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-PKCδ (Tyr311) Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2055; RRID: AB_330876 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-PKCα | Proteintech | Cat# 21991-1-AP; RRID: AB_2878965 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-PKCδ | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9616; RRID: AB_10949973 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SYP | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-17750; RRID: AB_628311 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F1804; RRID: AB_262044 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-VAChT | Synaptic Systems | Cat# 139 103; RRID: AB_887864 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-69879; RRID: AB_1119529 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-β-arrestin 2 | Proteintech | Cat# 10171-1-AP; RRID: AB_10644158 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-p504S | Agilent Technologies | Cat# M361601-2; RRID: AB_2305454 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-p63 (for IHC double staining) | Roche | Cat# 790-4509; RRID: AB_2335989 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-p63 (for IHC single staining) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-25268; RRID: AB_628092 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-2031; RRID: AB_631737 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG-HRP | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7074; RRID: AB_2099233 |

| Mouse anti-goat IgG-HRP | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-2354; RRID: AB_ 628490 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (H&L) Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32723; RRID: AB_ 2633275 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H&L) Alexa Fluor 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32732; RRID: AB_2633281 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| pLKO.1-puro non-mammalian shRNA control lentiviral particles | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SHC002V |

| pLKO.1-puro human CHRM1 shRNA#1 lentiviral particles | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SHCLNV_TRCN0000011250 |

| pLKO.1-puro human CHRM1 shRNA#2 lentiviral particles | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SHCLNV_TRCN0000011251 |

| Bacterial and virus strains Biological samples | ||

| Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) | University of Washington53 | LuCaP 147CR |

| Subcloning efficiency DH5α competent cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 18-265-017 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Abiraterone acetate | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-75054 |

| Carbachol | VWR | Cat# AAL06674-03 |

| Clozapine N-oxide | ApexBio | Cat# A3317 |

| Crystal violet | Fisher Scientific | Cat# c581-25 |

| Dicyclomine hydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D7909 |

| Docetaxel | Selleck Chemical | Cat# s1148 |

| EGF recombinant human protein | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# PHG0314 |

| Enzalutamide | Selleck Chemical | Cat# S1250 |

| Gefitinib | Selleck Chemical | Cat# S1025 |

| bFGF recombinant human protein | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 13256-029 |

| GM6001 | Selleck Chemical | Cat# S7157 |

| Human recombinant insulin solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# I9278 |

| McN-A-343 | R & D systems | Cat# 1384/10 |

| Mitoxantrone | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-13502 |

| M-MLV reverse transcriptase | Promega | Cat# PR-M1705 |

| SB203580 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-10256 |

| SCH772984 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-50846 |

| Scopolamine hydrobromide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S0929 |

| SGX-523 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-12019 |

| SP600125 | LC Laboratories | Cat# S-7979 |

| Src inhibitor 1 | Selleck Chemical | Cat# S6567 |

| Tropicamide | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-B0321 |

| YM-254890 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-111557 |

| Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# PI78443 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11668027 |

| Puromycin dihydrochloride | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A1113803 |

| Low melt agarose | IBI Scientific | Cat# IB70051 |

| B-27 supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 17504044 |

| Bovine serum albumin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP1600-100 |

| Formaldehyde | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP531500 |

| Triton X-100 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP151500 |

| DAPI solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 62248 |

| Tween 20 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP337500 |

| EcoRI | New England Biolabs | Cat# R0101S |

| XbaI | New England Biolabs | Cat# R0145T |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23225 |

| CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay | Promega | Cat# G7571 |

| Duolink In Situ Red Starter Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# DUO92101 |

| Fluo-8 Calcium Flux Assay Kit | Abcam | Cat# ab112129 |

| Human HGF ELISA Kit | RayBiotech | Cat# ELH-HGF |

| In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 12156792910 |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 28706 |

| Quickdetect Acetylcholine ELISA Kit | BioVision | Cat# E4452200524 |

| QuickChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent Technologies | Cat# E200524 |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 28104 |

| Quick Ligation Kit | VWR | Cat# M2200S |

| Pierce Co-Immunoprecipitation Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 26149 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 74104 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-seq raw data | This paper | GSE217749 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| 22Rv1 | ATCC | CRL-2505 |

| DU145 | ATCC | HTB-81 |

| 22Rv1DTXS | Dr. Milena Rizzo Lab (National Research Council of Italy, Pisa, Italy)12 | N/A |

| 22Rv1DTXR | Dr. Milena Rizzo Lab (National Research Council of Italy, Pisa, Italy)12 | N/A |

| DU145DTXS | Dr. Zoran Culig Lab (Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria)11 | N/A |

| DU145DTXR | Dr. Zoran Culig Lab (Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria)11 | N/A |

| PC3DTXS | Dr. Zoran Culig Lab (Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria)11 | N/A |

| PC3DTXR | Dr. Zoran Culig Lab (Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria)11 | N/A |

| 293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| COS-1 | ATCC | CRL-1650 |

| LNCaP | Dr. Leland Chung Lab (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA) | N/A |

| PC3 | ATCC | CRL-1435 |

| LASCPC-01 | ATCC | CRL-3356 |

| NCI-H660 | ATCC | CRL-5813 |

| LAPC4 | Dr. Michael Freeman Lab (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA) | N/A |

| C4-2 | Dr. Leland Chung Lab (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA) | N/A |

| C4-2B | Dr. Leland Chung Lab (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA) | N/A |

| C4-2BENZR | Dr. Allen Gao Lab (University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA)58 | N/A |

| WPMY-1 | ATCC | CRL-2854 |

| PCF1 | Dr. Leland Chung Lab (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA)22 | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| J:NU (nude) mice | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 007850 |

| NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice | Jackson Laboratory | Cat# 005557 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Human ChAT siRNA | Santa Cruz Biotech | Cat# sc-41919 |

| Human β-arrestin-2 siRNA | Santa Cruz Biotech | Cat# sc-29208 |

| Human CHRM1 siRNA | Origene | Cat# SR300807 |

| Control siRNA | Santa Cruz Biotech | Cat# sc-37007 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLVX-AcGFP1-N1 | Takara Bio | Cat# 632154 |

| pCMV-3×FLAG-Myc | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E6401 |

| pLVX-CHRM1 | This paper | N/A |

| pLVX-CHRM1-L167A | This paper | N/A |

| pLVX-CHRM1-C391A | This paper | N/A |

| pLVX-CHRM1-C394A | This paper | N/A |

| pLVX-CHRM1-P396A | This paper | N/A |

| pLVX-hM1Dq | Armbruster et al.25 and this paper | N/A |

| pLVX-FLAG-hM1Dq | This paper | N/A |

| pCMV-myc-ERK2-L4A-MEK1 fusion | Robinson et al.28 | RRID: Addgene_39197 |

| pcw107-FLAG-MKK7-JNK2 fusion | Martz et al.29 | RRID: Addgene_64618 |

| pcDNA3-FLAG-MKK6 (Glu) | Raingeaud et al.30 | RRID: Addgene_13518 |

| pCMV delta R8.2 | Dr. Didier Trono Lab (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland) | RRID: Addgene_12263 |

| pCMV-VSV-G | Stewart et al.59 | RRID: Addgene_8454 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Image Lab 6.1 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/product/image-lab-software |

| HALO | Indica Labs | https://indicalab.com/halo/ |

| GSEA v4.0.3 | Subramanian et al.60 | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/ |

| GraphPad Prism 9 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Bowtie 2 v2.1.0 | SourceForge | https://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/ |

| RSEM v1.2.15 | Li and Dewey61 | https://deweylab.github.io/RSEM/ |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Varadi et al.62 | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) v2020.9 | Chemical Computing Group ULC42 | https://www.chemcomp.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Boyang Jason Wu (boyang.wu@wsu.edu).

Materials availability

All reagents generated in this study are accessible from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The RNA-seq data generated in this study are available in the NCBI GEO database with the accession number GSE217749. This study does not generate the original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the Lead Contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell culture

Human PC 22Rv1, DU145, PC-3, LASCPC-01, NCI-H660, human embryonic kidney 293T, African green monkey kidney fibroblast COS-1, and human myofibroblast WPMY-1 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The human PC LNCaP, C4-2, C4-2B, and human PC-associated fibroblast PCF1 cell lines were provided by Dr. Leland W.K. Chung (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center). The human PC LAPC4 cell line was provided by Dr. Michael Freeman (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center). The ENZ-resistant human PC C4-2B (C4-2BENZR) cell line was provided by Dr. Allen Gao (University of California, Davis).58 DTX-resistant and sensitive 22Rv1 cell lines (22Rv1DTXS and 22Rv1DTXR) were provided by Dr. Milena Rizzo (Institute of Clinical Physiology, National Research Council of Italy).12 DTX-resistant and sensitive DU145 and PC-3 cell lines (DU145DTXS, DU145DTXR, PC-3DTXS and PC-3DTXR) were generated as described previously.11 All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling in February 2021, regularly tested for Mycoplasma by the MycoProbe Mycoplasma Detection Kit (R&D System), and used with the number of cell passages below 10. The 293T, COS-1 and WPMY-1 cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning). The PCF1 cell line was cultured as described previously.22 All the other cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The 22Rv1DTXR, DU145DTXR and PC-3DTXR cell lines were cultured in the continuous presence of 3, 12 and 12 nM DTX, respectively, to maintain DTX resistance.

Animal studies

All animal studies received prior approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Washington State University (WSU) and were carried out in accordance with IACUC recommendations. Male 4- to 6-week-old nude or NSG mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in the animal research facility at WSU. All mice were grouped by no more than 5 mice per cage, maintained in a pathogen-free IVC system, and fed a normal chow diet. For cell line-derived xenograft tumor studies, 4 × 106 cells were mixed 1:1 with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and implanted subcutaneously into both flanks of mice. For PDX studies, the recipient mice were surgically castrated. Two weeks later, the LuCaP 147CR xenograft tumor tissue was cut into ∼5-10 mm3 pieces and implanted subcutaneously into both flanks of the pre-castrated mice. When tumors reached ∼100 mm3, mice were randomly divided into four groups (6-12 tumors per group) and treated with vehicle (saline, i.p., daily), Dic (8 mg/kg, i.p., daily), DTX (10 mg/kg, i.p., weekly), or DTX + Dic. Tumor size was measured by caliper every 2-3 days after treatment. Tumor volume was calculated as length × width2 × 0.52. At the endpoints, tumors were dissected and weighed. Tumor samples were collected for subsequent analyses.

Clinical specimens

All tissue specimens used in this study were archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) PC tissues. The malignant prostate tissue specimens from 14 PC patients who underwent chemotherapy with DTX before radical prostatectomy and 13 untreated PC patients, used in Figures 2A and S6A, were obtained from Innsbruck Medical University (Innsbruck, Austria) as described previously.11 The use of archived materials was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck (EV 1072/2018). Written consent was obtained from all patients and documented in the database of the University Hospital Innsbruck in agreement with statutory provisions. The primary PC tissue specimens, longitudinally collected from the same patient cohort (n = 5) pre- and post-chemotherapy with DTX through sequential procedures by transrectal ultrasound scan-guided biopsy and transurethral resection of the prostate, used in Figures 2B, S5A, S6B and S6E, were obtained from the Biobank of Taipei General Veterans Hospital (Taipei, Republic of China). The 6 human CRPC tissue specimens used in Figure S4C were also obtained from the Biobank of Taipei General Veterans Hospital. The use of human tissue specimens received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Taipei General Veterans Hospital with written informed consent provided by patients.

Method details

Biochemical analyses

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit and reverse-transcribed to cDNA by M-MLV reverse transcriptase following the manufacturers’ instructions. qPCR was conducted using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and run with the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR conditions included an initial denaturation step of 10 min at 95oC, followed by 40 cycles consisting of 15 s at 95oC and 1 min at 60oC. The PCR data were analyzed by the 2-ΔΔCT method.63 Primer sequences for probing CHRM1-5 are as follows: CHRM1 forward 5’-TGACCGCTACTTCTCCGTGACT-3’ and reverse 5’- CCAGAGCACAAAGGAAACCA-3’, CHRM2 forward 5’-CTCCAGCCATTCTCTTCTGG-3’ and reverse 5’-GCAACAGGCTCCTTCTTGTC-3’, CHRM3 forward 5’-CGCTCCAACAGGAGGAAGTA-3’ and reverse 5’-GGAGTTGAGGATGGTGCTGT-3’, CHRM4 forward 5’-GCCCACTAATGAAGCAGAGC-3’ and reverse 5’-ACTGCCTGAGCTGGACTCAT-3’, and CHRM5 forward 5’-CCTGGCTGATCTCCTTCATC-3’ and reverse 5’-GTCCTTGGTTCGCTTCTCTG-3’. For immunoblots, cells were extracted with RIPA buffer in the presence of a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Blots were performed as described previously64 using different primary antibodies. ACh and HGF levels in cell culture media were quantified by ELISA.

Generation of stable knockdown and overexpression cells

Stable shRNA-mediated CHRM1 KD was achieved by transducing cells with lentiviral particles expressing CHRM1 shRNA #1 (shCHRM1#1) or #2 (shCHRM1#2), followed by 2-week puromycin selection (2 μg/ml) to establish stable cell lines. A non-targeting control shRNA (shCon) was used as control for stable KD cells. Lentivirus production was performed for stable OE of CHRM1 or DREADD-based hM1Dq in 22Rv1 cells. Briefly, 293T cells were co-transfected with CHRM1- or hM1Dq-expressing lentiviral constructs, pCMV delta R8.2 and pVSVG in a 4:2:1 ratio using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions. The medium was changed 6 h after transfection. The medium containing lentivirus was harvested 48 h after transfection. Virus was concentrated and purified using a Lenti-X concentrator (Takara Bio). Cells were infected with lentivirus in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml) followed by 2-week puromycin selection (2 μg/ml). An empty lentiviral construct was used in parallel as control for stable CHRM1 OE in cells.

Analyses of cell proliferation, soft-agar colony formation and tumorsphere formation

For cell proliferation experiments, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1,000-2,000 cells/well) and grown under different treatments for up to 7 days. Cell viability was determined by MTS or CellTiter-Glo cell viability assays following the manufacturer’s instructions. For determining anchorage-independent colony formation, cells were suspended in culture medium containing 0.3% agarose at a density of 200-400 cells/well and placed on top of solidified 0.6% agarose in 6-well plates. Cells were grown under different treatments until visible colonies formed, and were then stained with crystal violet. For determining tumorsphere formation, cells were seeded in ultra-low attachment 24-well plates (Corning) at a density of 1,000 cells/well in serum-free PrEBM medium (Lonza) supplemented with B-27 supplement, 20 ng/ml EGF, 10 ng/ml bFGF, 5 μg/ml insulin and 0.4% BSA. Media were replenished every 3 days until spheres arose 1-2 weeks after plating. Colonies and spheres were imaged with a ChemiDoc Touch Imager (Bio-Rad) and the numbers of colonies or spheres containing ≥50 cells were enumerated with ImageJ software (NIH).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

Cells seeded on chamber slides received treatments with DTX and/or Dic for 48 h. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, rinsed twice with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS solution for 10 min at room temperature followed by two washes with PBS. Subsequently, TUNEL staining was performed in cells using a fluorescein-based In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. DAPI was added for nuclear staining before mounting. Images were acquired by a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 upright microscope and analyzed for nuclear fluorescence with HALO (Indica Labs) software.

Analyses of cell wound-healing response, migration and invasion

For wound-healing assays, 8 × 105 PC-3DTXR cells were seeded in 6-well plates, incubated overnight to achieve a high-density adherent monolayer, and treated with 12 nM DTX in combination with or without 25 μM Dic. A scratch was created using a pipette tip immediately after treatment in each well. Images of scratches were captured for individual wells by a Leica microscope and quantified for wound area at 0, 24 and 48 h using ImageJ software. Transwell-based migration and invasion assays were performed with 6.5-mm transwell inserts (8-μm pore size) coated with or without growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning) to measure cell invasive and migratory abilities, respectively. 1-2 × 105 PC cells were serum starved overnight to eliminate the interference of proliferation on cell migration and invasion, and then seeded into inserts containing serum-free culture medium under different treatments. After 24-48 h, the cells that translocated to the lower surface of insert membranes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde. The fixed membranes were stained using 1% crystal violet. The images were taken by a Leica microscope and the numbers of migrating or invading cells were quantified by counting the number of stained nuclei in five independent fields in each transwell by ImageJ software.

Proximity ligation assay

22Rv1DTXR cells were seeded on chamber slides and treated with carbachol (10 μM, 30 min) with or without pre-treatment with Dic (25 μM, 30 min). Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS containing 0.02% Tween 20, and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS solution (blocking solution) for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies against CHRM1 or cMET were incubated in blocking solution at 4oC overnight. Subsequently, the assay was performed with a Duolink In Situ Starter Kit Mouse/Rabbit according to the manufacturer’s instructions using anti-mouse MINUS and anti-rabbit PLUS PLA probes. Images were acquired by a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 upright microscope using a 40× objective and analyzed for cytoplasmic fluorescence intensity per cell with HALO software.

Co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) assay

CoIP assays were carried out using a Pierce Co-IP Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were lysed in ice-cold IP lysis/wash buffer, pre-cleared with control agarose resin at 4oC for 30 min, and incubated overnight at 4°C with a cMET antibody or IgG immobilized to AminoLink Plus coupling resin in reaction buffer. Immunoprecipitates were washed with lysis/wash buffer for 6 times and eluted with elution buffer followed by immunoblots using antibodies against CHRM1 or FLAG.

Site-directed mutational analysis of CHRM1 residues

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to mutate the cMET-interacting residues predicted in the extracellular region of CHRM1 with a wild-type pLVX-CHRM1 construct as the template. Mutagenesis was carried out by a QuickChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences used for mutating select residues on CHRM1 are listed as follows with mutated nucleotides underlined: L167A: 5’-GTCCGCTCCCCTACCGCGTACTGCCAGAAGAG-3’; C391A: 5’-GGGAACACAGTCCTTGGCGAAGGTGGACACCAGC-3’; C394A: 5’-CAGGGTCTCGGGAACAGCGTCCTTGCAGAAGGTG-3’; and P396A: 5’-CACAGGGTCTCGGCAACACAGTCCTTGCAG-3’. Mutant constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Calcium influx detection

Calcium influx in cells was analyzed using a Fluo-8 Calcium Flux Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 8 × 104 PC cells were seeded in 96-well plates with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 1% FBS and incubated with Fluo-8-dye-loading buffer at 37°C for 30 min followed by another 30-min incubation at room temperature in dark. Cells were then treated with or without 25 μM Dic or 20 μM YM-254890 for 5 min prior to stimulation with 10 μM carbochol, 50 μM McN-A-343 or 100 nM CNO. Immediately after stimulation, the RFU signal emitted from cells was monitored at Ex/Em=490/525 nm on a Synergy NEO microplate reader (BioTek) for 10 min at 6-s intervals.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence (IF)

Clinical prostate tumor and cell line- and patient-derived xenograft tumor samples were analyzed by single or double IHC (for CHRM1, Ki-67, cleaved caspase 3, p-cMET, p63, p504S, CHRM3 and SYP) and IF (for NF-L and VAChT) following our published protocols.65,66 The H-scores for CHRM1 and CHRM3 IHC staining and intensity for NF-L+/VAChT+ coIF staining in clinical samples, and percentages of positive expression or per-cell intensity for IHC staining of individual proteins in xenograft samples were analyzed by HALO software after areas of interest were defined using manual tissue segmentation by a pathologist.

Protein-protein docking

The binding surface between the extracellular region of CHRM1 (aa 1–22, 85-95, 165-185 and 391-397) and the N-terminal SEMA domain (aa 27-515) of cMET was predicted by a MOE-based protein-protein docking protocol.42 Briefly, the 3D structures of CHRM1 (aa 19-460) and extracellular region of cMET (aa 25-932) were built by AlphaFold 2, and then processed by protonation and optimization under the AMBER10:EHT force field by MOE software (version 2020.9). CHRM1 was set as a ligand, while MET was set as a receptor. The top-ranked docking pose with the most extracellular contact residues predicted on CHRM1 was used for further experimental validation.

RNA-seq and gene set enrichment analysis

Total RNA samples from 22Rv1DTXR and 22Rv1DTXS cells and Dic- (25 μM, 72 h) and vehicle-treated 22Rv1DTXR cells were extracted by a RNeasy Mini Kit and underwent DNase digestion following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA-seq was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 4000 at Novogene. Bowtie 2 v2.1.0 was used for mapping to the human genome hg19 transcript set. RSEM v1.2.15 was used to calculate the count and estimate gene expression levels. GSEA v4.0.3 was used to evaluate the enrichment of different gene sets from the molecular signature database (MSigDB v7.2) or curated based on related studies.

Bioinformatic analysis

The human PC datasets GSE35988 for examination of CHRM1 and CHRM3 association with response to chemotherapy, SU2C/PCF 2019 for assessment of CHRM1 association with AR and NEPC scores and relevant GSEA studies, TCGA for examination of CHRM1 association with AR score, and GSE32967, GSE66187 and GSE41192 for comparisons of CHRM1 expression in NEPC vs. Adenocarcinoma were downloaded from NCBI GEO and cBioPortal databases.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD as indicated in figure legends. Comparisons were analyzed by unpaired or paired two-tailed Student t test, or one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison correction as appropriate. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jingjing Li for technical help, Kathryn Meier for scientific advice and editing assistance, and Gary Mawyer for editorial assistance. This work was supported by NIH/NCI grants R37CA233658 and R01CA258634 and WSU College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences startup funding (to B.J.W.), Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program grant W81XWH-20-1-0115 (to T.B. and T.P.), and the ASPET Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) program (to V.K. and K.V.). The establishment and characterization of LuCaP PDX models were supported by the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE (P50CA97186), the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Biorepository Network (W81XWH-14-2-0183), and NCI (P01CA163227).

Author contributions