Summary

This study explores the lipid content and micromorphological features of sediment samples from two dwelling structures at the pre-Hispanic site of La Fortaleza in Santa Lucía de Tirajana (Gran Canaria, Spain). Previous field identification of possible sedimentary excrements inside the dwellings motivated chromatographic fecal biomarker analysis and micromorphology. The micromorphological samples reveal a complex dung-rich stratified sequence involving different layers of mixed composition, including reworked dung, clay, wood ash, and domestic refuse. The results of the lipid analysis corroborate the fecal nature of the sample and indicate the source animal: sheep. Coupled with the field evidence, the data suggest that the deposit is anthropogenic and represents a sequence of floor foundations, dung floors, and domestic and architectural refuse. This study provides valuable taxonomic and site use data for the understanding of the aboriginal societies of the Canary Islands and shows the efficacy of combining field observations with high-resolution geoarchaeological methods.

Subject areas: Archeology, Paleobiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Micromorphological and fecal biomarker analyses were applied to sediments

-

•

Identification of feces in a domestic structure from La Fortaleza (Spain)

-

•

Taxonomic identification of sheep as feces-producing animals

-

•

Use of sheep dung as possible construction materials

Archeology; Paleobiology

Introduction

The archaeological record provides data essential to approach economic aspects of the Canary Islands' aboriginal populations. Archaeobotanical and paleoenvironmental,1,2,3,4 zooarchaeological,5,6,7,8 and paleogenetic studies,9,10 among others, have provided valuable information. Chronicles written by the first European visitors in the late Middle Ages offer descriptions of the natural resources, subsistence practices, and socioeconomic organization of the communities on different islands.11

In pre-Hispanic times, the Canary Islands' aboriginal population had a mixed subsistence economy, with differences from island to island. In Gran Canaria, current evidence points to the practice of agropastoralism, combining livestock and agricultural practices,12 including irrigation and possibly intensifying the exploitation of marine resources in the final centuries of the pre-Hispanic period.13,14,15 Paleobotanical evidence indicates that the main cultigens were barley (Hordeum vulgare, the predominant cultigen), durum wheat (Triticum durum), lentils (Lens culinaris), broad beans (Vicia faba), peas (Pisum sativum), and figs (Ficus carica).2,16,17 Animal husbandry involved goats, sheep and pigs, but the zooarchaeological distinction between sheep and goat is problematic18,19 and there is little information about possible differences in the exploitation of these two species, which are jointly referred to as "ovicaprid/ovicaprine."6,19,20 In the Canary Island context, this ambiguity has led to inconclusive results and the assignment of indeterminate bone remains to goat in a case where goat predominated among the identifiable remains.6

A geoarchaeological approach using combined lipid biomarker analysis and soil micromorphology might help distinguish between sheep and goat through the taxonomic identification of the animal's excrements from coprolites or coprolite-rich sediments such as penning deposits. Soil micromorphology has been widely used to identify goat/sheep pens from different regions and time periods through the conspicuous microscopic components of ruminant excrements and the manifest microstructure of trampled fodder.21,22,23 Fecal lipid biomarkers have also provided valuable information on excrement sources and dietary intake in different settings, from Roman contexts24,25,26 to the earliest North American settlements,27 and even a case dating back to the Paleolithic.28 These studies are based on the identification of: 1) sterols, which are steroids typical of plant biomass (mainly stigmasterol and β-sitosterol) and animal tissues (predominantly cholesterol),29 2) stanols (5α-stanols, 5β-stanols, and epi-5β-stanols), which are biomarkers derived from the reduction of cholesterol and phytosterols in the intestinal tract of most mammals,29,30 and 3) bile acids, modified by microbial flora in the liver and intestines of mammals.29,30,31 These molecules appear in different proportions depending on the source animal, which can be ascertained using algorithmic equations that help discern between the presence/absence of feces,29,32 different dietary sources (herbivore, carnivore, or omnivore)33,34 and different herbivorous animals.26,29

Geoarchaeological biomolecular research in Canary Island sites is incipient and so far, focused on identifying fuel sources in domestic contexts,4 as well as understanding site formation processes and exploring plant sources.35 Here, we apply combined fecal biomarker and micromorphological analysis to sediments from La Fortaleza (Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Gran Canaria), a multi-site archaeological complex spanning the entire pre-Hispanic aboriginal period from the 5th to 15th centuries36 (Figure 1). The samples are from hypothetical excremental floor remains found in the recent excavation of two stone buildings that are part of the same house within the settlement complex: E−7 and E−7.1.

Figure 1.

Map showing geographical positioning and general views of La Fortaleza

(A) Location of La Fortaleza archaeological site in the island of Gran Canaria.

(B) La Fortaleza Grande (right) and Chica (left). Photo: Nacho G. Oramas, Museum of La Fortaleza.

(C) La Fortaleza Grande (east slope). Photo: Nacho G. Oramas, Museum of La Fortaleza.

(D) Western slope of La Fortaleza where the indigenous settlement of La Fortaleza is located (11th-15th centuries). Photo: Tibicena. Arqueología y Patrimonio.

Applying a microcontextual bioarchaeological approach to the indeterminate, hypothetically excremental sediments will help establish the nature and formation of the sedimentary floor deposits found in buildings E−7 and E−7.1. If these represent animal excrement and they can be sourced, the data will contribute information toward a better understanding of aboriginal pre-Hispanic animal husbandry practices in Gran Canaria. Furthermore, explaining the presence of animal excrements within the buildings will advance our knowledge on site use and domestic life during aboriginal times.

Thus, the goal of this study is to analyze the sediment from the basal fills of the two archaeological buildings from La Fortaleza indicated above using combined fecal biomarkers and micromorphology and: (a) determine the presence/absence of feces, (b) if feces, determine the animal source, (c) if feces, determine if the deposit represents primary dung (an animal pen) or redeposited dung as construction material or as refuse, (d) advance the knowledge of Canary Island aboriginal pre-Hispanic societies, specifically animal husbandry practices and architectural traditions in Gran Canaria, (e) show the efficiency of microcontextual bio-geoarchaeological approaches in archaeological science.

Stratigraphic and archaeological context of the hypothetical excremental floor

Building E−7 is larger, has a cruciform morphology, and is found at a higher level than building E−7.1, which is circular (Figure 2). The smaller building E−7.1 is only accessible from the interior of E−7, through a door threshold and three steps that connect both levels. As observed for all the other buildings found within the archaeological settlement, these two are embedded in the natural substrate, which was excavated and leveled for their construction. As a whole, the archaeological settlement exhibits a terraced layout of buildings connected by stone-paved streets. Such a layout and architectural typology have been documented at several pre-Hispanic sites across Gran Canaria and are generically interpreted as dwellings.37

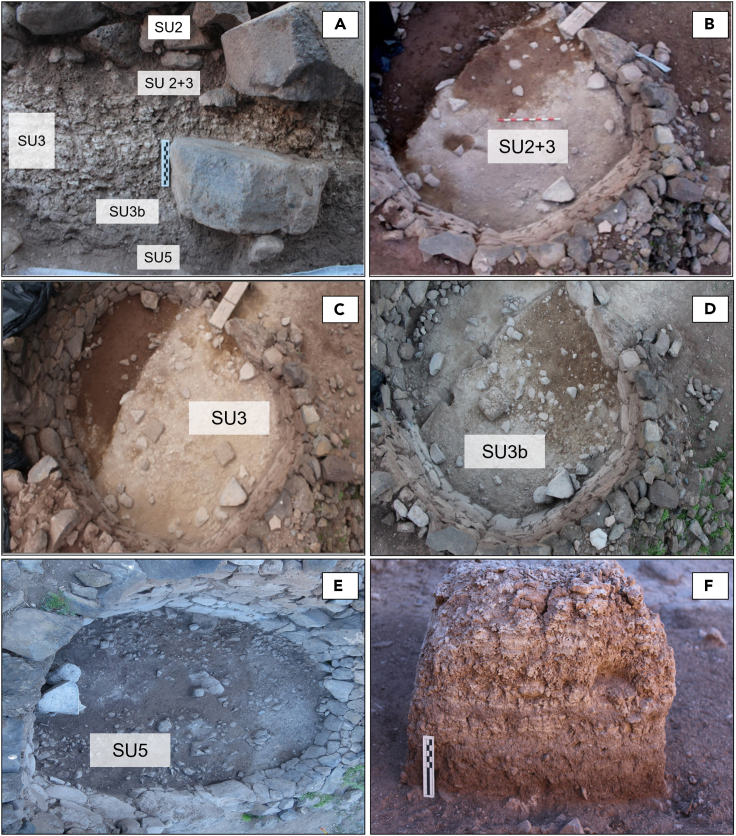

Figure 2.

Contextual photographs of the analyzed samples in structures E−7 and E−7.1

(A) 3D rendering and proposed roof reconstruction based on the photogrammetric restitution of Buildings E−7 and E−7.1. Published from38 with permission from Tibicena Publicaciones.

(B) Left image: structures E−7.1, E−7 (the red dot marks the sampled location). Right image: detail of the steps connecting structures E−7.1 and E−7.

(C) Stratigraphic sequence at the sampled area at structure E−7 after removal of the micromorphology block and location of the loose sediment samples used for fecal biomarker analysis in E−7.

(D) Left image: sampling of micromorphological samples from structure E−7.1 (LFZ1-back- and LFZ2-front). Right image: sediment block from where sample LFZ2 was collected.

Both buildings are partially filled with a stratified deposit composed of 4 layers (Figure S1), from base to top: Stratigraphic Unit 5 (SU5), Stratigraphic Unit 3b (SU3b), Stratigraphic Unit 3 (SU3) and Stratigraphic Unit 2 + 3 (SU2+3). The numbers of these layers hold correspondence with the general stratigraphic sequence of the entire site complex.

The basal layer (SU5) in both buildings consists of a compact clayey deposit of 17 cm in thickness. This unit is interpreted as a base construction or foundation leveling deposit based on its content, which comprises.

-

(1)

Remmants of ash mortar and ochre fragments generated in the work of plastering and painting the walls, as it can still be seen in some portions of the wall (Figure S2A).

-

(2)

Lithic debris is associated with masonry works based on their lithological match with the walls’ stones, their irregular shapes and sizes, the low number of negatives on the dorsal faces, and a specific spatial concentration. Likewise, traces of this work in preparing the blocks can be seen in the extraction negatives of many of the stones used to build the walls.

-

(3)

In E−7.1, a small artificial stone-lined pit containing a goat horn and a lithic artifact made on trachite, an exotic high-quality stone (Figure S2B). In the context of pre-Hispanic Gran Canaria, such deposits are interpreted as foundational deposit assemblage.39

Overlying the SU5 clayey deposit with a sharp contact lies SU3b, a 8–10 cm thick clayey deposit containing compact, ashy gray lenses. The top is horizontal and incorporates numerous homometric boulders that form an apparent pavement, which suggests that this is an anthropogenic construction deposit made to level the floor and to enhance the grip and adherence of mortars and other soft paving materials. Another ritual assemblage was found on this stone surface, consisting of a front limb of a perinatal sheep or goat (Figure S2C).

SU3, is the hypothetical excremental layer, based on its yellowish color and layered, aggregated appearance. It is loose and has a silty-sandy texture and a blocky structure. In E−7, this hypothetical excremental sediment also partially coats the surface of the first step connecting the upper and lower levels (Figure 3). This deposit contains scarce archaeological remains. In E−7, stands out two articulated back limb goat toes. These anatomical elements are associated with symbolic activities among pre-Hispanic Canarian societies.19

Figure 3.

Photographs of the archaeological-structural context of buildings E−7 and E−7.1

(A) Pre-Hispanic occupation context in E−7. The surface shown is on SU 3 and exhibits stony patches of SU2 at the center.

(B) View of the test pits made within the building. The sampled area is shown in red.

(C) General view of the steps in E−7.1.

(D) Frontal view of the upper step covered by SU3 sediment.

(E) Base of SU3: small-sized stones at the base of the wall used as shims (green arrow), on the left, a phonolite block is partially covered by SU3 sediment and used to fix the mass of excrement (yellow arrow), and in the center, the upper stone step on which SU3 rests.

(F) Field view of a section in E−7 showing SU2+3 and SU3.

SU 2 is a 1.50 m thick loose sandy-clayey deposit containing fallen stones from the building’s walls, suggesting that it formed after abandonment, structural collapse, and exogenous natural sedimentation. The archaeological content of this unit is high and comprises mainly domestic refuse such as ceramic fragments, bone fragments with consumption marks, and stone tools.

SU2+3 is a localized, loose, poorly sorted, lithologically heterogeneous deposit incorporating sediment from SU2 and SU3. It is stratigraphically positioned between both units (SU3 and SU2) and it may have formed after the abandonment and initial collapse of the buildings. Like SU2, it contains numerous archaeological remains representative of domestic activity.

The architectural features and archaeological content of the two stone buildings point to a domestic context. The upper one (E−7) exhibits the typical layout of pre-Hispanic dwellings in Gran Canaria, with a central living space and smaller side rooms possibly used as bedrooms. These buildings are typically poor in archaeological content, which suggests regular interior cleaning and maintenance, as is also mentioned in the written record (early Hispanic chronicles). The lack of archaeological material inside also implies that most activities were carried out outdoors.37,40 Thus, outdoor spaces between dwellings usually contain abundant archaeological material.

Building E−7.1 is interpreted as a storage room based on the numerous ceramic containers found there in situ (at least 12 containers typologically interpreted as food containers)41 (Figure S2D). This building is not directly connected with the exterior. Its only access point is from E−7, through a threshold with a series of steps. The connection between both buildings indicates their contemporaneity and suggests that E−7.1 might have been a private space, possibly a granary or a similar food storage space as documented in other pre-Hispanic archaeological contexts42 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Views of the stratigraphic sequence in structures E−7 and E−7.1 during the archaeological excavation

(A) Field view of Building E−7.1 showing the stratigraphic sequence.

(B) Field view of the E−7.1excavation surface at of E7.1 during the excavation of SU2+3.

(C) Field view of the E−7.1 excavation surface during the excavation of SU3.

(D) Field view of the E−7.1 excavation surface at Unit 3b.

(E) Field view of the E−7.1 excavation surface at Unit 5, the natural clayey substrate.

(F) Field view of the micromorphology sample collected from the southern area of Building E−7.1.

Results

Soil micromorphology

Identification and description of features from micromorphological samples followed the established protocols as outlined in Stoops (2003),43 Nicosia and Stoops (2017),44 and Stoops et al. (2018)45 (STAR Methods Soil Micromorphology) The results are shown in Figures 5 and 6. The thin sections from the E−7 and E−7.1 fills show similar micromorphological features, which have been classified into 3 microfacies units (MFU). Field SU5 at the base of the deposit is composed of a massive clayey sediment with granular patches. Besides the clay, there are a few coarse sand-gravel-sized pyroclasts and rounded calcrete fragments (Figures 5A and 5B). The clayey matrix is not calcitic but there are common secondary calcite infillings, coatings, and nodules (Figures 5C and 5D), and a few calcitic ash aggregates. The clayey granules contain sparse calcitic fecal spherulites (Figures 5E and 5F). Upwards through the deposit, field SU3b is more compact (Figure S3) but shows the same composition as SU5, with common clayey grains and granules, some of these containing spherulites (Figures 6A and 6B). There are also loose spherulites scattered throughout the matrix. In E−7, SU3b shows alternating beds of compact sediment bound with sharp upper and lower contacts and containing gravel-sized pyroclasts and very few bone fragments (Figure S3).

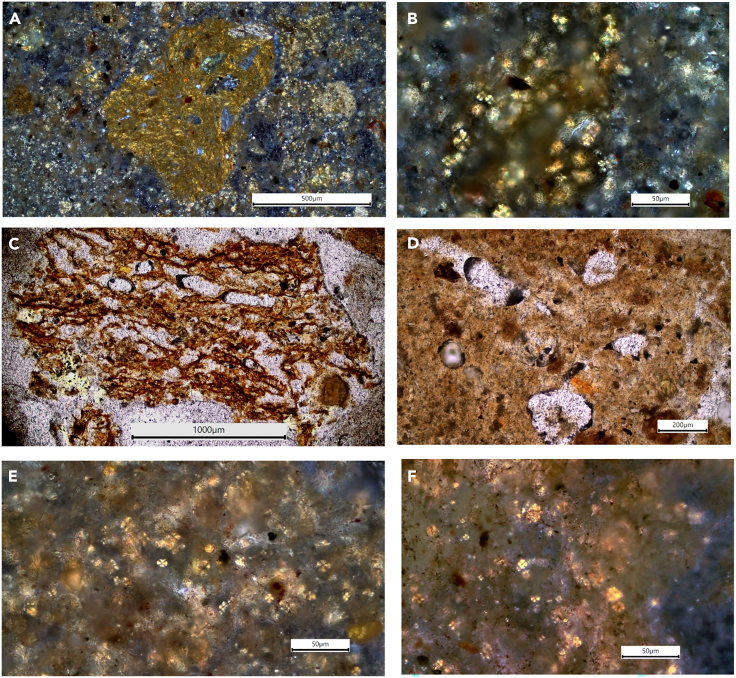

Figure 5.

Representative microphotographs from SU5 at the base of the deposit (all views in crossed polarized light [XPL])

(A and B) Calcreted, granular soil aggregates.

(C) Nodule with secondary calcite infillings (white cement) and a vertical channel on the right, possibly from a root.

(D) Phosphatic granular matrix with secondary calcite infillings.

(E and F) View of the Unit 5 matrix under high magnification showing sparse calcitic fecal spherulites.

Figure 6.

Representative microphotographs from SU3

(A, B, E, and F in plane polarized light [PPL] and C and D in crossed polarized light [XPL]). (A) Birefringent clayey grain. (B) The clayey grain in A showing the presence of calcitic fecal spherulites visible under high magnification. (C) Fibrous, spongy ped. (D) Vesicles within the fibrous ped. (E and F) View of the SU3 matrix under high magnification showing sparse calcitic fecal spherulites.

The overlying SU3 is made up of compact microscopic angular and subangular-blocky clayey peds containing calcitic fecal spherulites. These peds are fibrous and spongy, exhibit diffuse microlamination and vesicular or moldic porosity (Figures 6C and 6D), and contain sparse calcitic fecal spherulites (Figures 6E and 6F). Some of the peds are broken and overturned. The matrix surrounding the peds is loose and granular (Figure S3), with the same features described for SU3b. This unit also contains scattered sand-sized pyroclasts.

The top layer, which was identified in the field as a mix of SU2 and SU3, shows two different microfabrics: at the base it is loose and shows smaller fragments and granules of the same composition as in SU3 and scattered calcitic fecal spherulites in the matrix. There are also gravel-sized pyroclasts. The top part is more compact and contains poorly preserved sand-sized bone fragments. A single shell fragment was identified here. SU2 and SU3 have been assigned to MFU 1 and 2, as their micromorphological features and microstructure are very similar to those of SU5 and SU3b, respectively, but MFU 2 contains more archaeological remains.

Fecal biomarkers

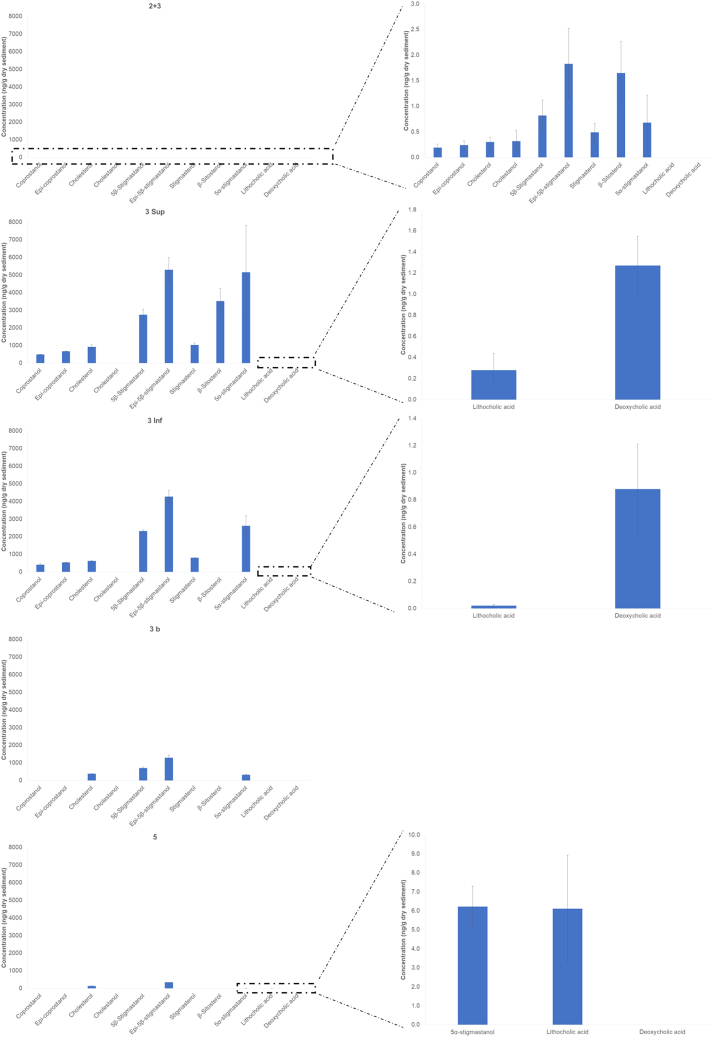

GC-MS in full scan mode was used to determine the compounds (STAR Methods GC-MS analysis). For this purpose, the method was validated in terms of matrix effect (70–104%), linearity (R2 ≥ 0.914), recoveries (63–108%), and limits of detection and quantification (LOQs) (Table S2and STAR Methods GC-MS analysis). The results of the analysis are presented in Table 1 and Figure 7. Sterol and stanol concentrations varied between 0.20 ± 0.12 and 5293.94 ± 680.41 ng/g dry sediment, while bile acids ranged from 0.02 ± 0.01 to 6.10 ± 2.83 ng/g dry sediment. The fecal biomarkers in the most concentrated samples (3 Sup and 3 Inf) were approximately 1750–3000 times higher than the least concentrated sample (2 + 3). Among sterols/stanols, epi-5β-stigmastanol and 5β-stigmastanol were the dominant compounds in most samples, whereas other compounds such as β-sitosterol (2 + 3 and 3 Sup) and 5α-stigmastanol (3 Sup and 3 Inf) were also present in significant amounts. Lithocholic and deoxycholic acids were the only bile acids detected in these samples. To determine the presence and possible origin of feces, we calculated the ratios 1,32 2,29,32 3,33 and 429,34 (STAR Methods Quantification and statistical analysis), and the results are presented in Table 2. The value of Ratio 1 was 0.58 for sample 2 + 3, 1.00 for 3 Sup and 3 Inf, and could not be calculated for 3b and 5. Ratio 2 varied from 0.61 to 0.98, Ratio 3 ranged from 0.00 to 0.16, and Ratio 4 ranged from 0.00 to 18.94%.

Table 1.

Fecal biomarkers and their concentration as detected in the analyzed samples (ng/g)

| Biomarkers | 2+3 (ng/g) | 3 Sup (ng/g) | 3 Inf (ng/g) | 3b (ng/g) | 5 (ng/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coprostanol | 0.19 s± 0.07 | 497.72 ± 7.40 | 415.04 ± 49.95 | – | – |

| Epi-coprostanol | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 668.82 ± 28.42 | 537.76 ± 10.24 | – | – |

| Cholesterol | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 918.35 ± 124.11 | 629.57 ± 5.66 | 385.54 ± 4.73 | 138.98 ± 21.02 |

| Cholestanol | 0.32 ± 0.21 | – | – | – | – |

| 5β-Stigmastanol | 0.82 ± 0.30 | 2749.19 ± 311.02 | 2320.60 ± 71.28 | 714.01 ± 64.30 | – |

| Epi-5β-stigmastanol | 1.83 ± 0.69 | 5293.94 ± 680.41 | 4275.24 ± 337.63 | 1291.46 ± 148.23 | 349.26 ± 0.00 |

| Stigmasterol | 0.49 ± 0.17 | 1027.99 ± 110.05 | 804.37 ± 4.26 | – | – |

| β-Sitosterol | 1.65 ± 0.61 | 3519.06 ± 709.49 | – | – | – |

| 5α-stigmastanol | 0.68 ± 0.53 | 5149.64 ± 2647.08 | 2618.19 ± 562.20 | 329.35 ± 20.39 | 6.22 ± 1.08 |

| Total sterols + stanols | 6.55 | 19824.72 | 11600.79 | 2720.37 | 494.46 |

| Lithocholic acid | – | 0.28 ± 0.16 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | – | 6.11 ± 2.83 |

| Deoxycholic acid | – | 1.27 ± 0.28 | 0.88 ± 0.33 | – | – |

| Total bile acids | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 6.11 |

Figure 7.

Fecal biomarker concentration (ng/g dry sediment) in the analyzed samples (error bars represent uncertainty)

Table 2.

Fecal ratios obtained from the concentrations

| Ratio | 2+3 | 3 Sup | 3 Inf | 3b | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – |

| 2 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.98 |

| 3 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 18.94% | 15.33% | 15.17% | 0.00% | – |

Discussion

Soil micromorphology

The E−7 and E−7.1 sedimentary sequences show similar micromorphological features. At the base, field SU5 and SU3b comprise massive and granular clayey sediment containing calcitic fecal spherulites within the granules or scattered throughout the matrix. This composition, together with the presence of detrital calcrete grains and pyroclasts points to an earthen anthropogenic fill including sheep or goat dung, as evidenced by the presence of calcitic fecal spherulites.22 The lack of particle sorting, and prepared floor structures or microstructures suggests an anthropogenic dump of exogenous sediment.46 The higher degree of compaction observed in SU3b compared to SU5, the occurrence in Building E−7.1 of at least two compact horizontal segments bound by sharp contacts within this unit, and the associated presence of anthropogenic remains such as bone (SU3b, sample FLZ4) suggests that this unit represents at least two sets of possible anthropogenic beaten dung floors (the compact dung layers) underlain by loose and granular, floor preparation deposits (SU5). This hypothesis agrees with the lack of archaeological remains found in SU5 other than goat horns, hooves, and high-quality lithic objects, among others. These deposits are clearly different from the usual domestic remains in the aboriginal living spaces. They are frequent manifestations in a multitude of chronocultural contexts whose symbolic value, together with their position in the base levels of the houses, has led to relate them to acts or foundational rituals. The lack of fissures in the SU3b sediment suggests low intensity trampling and possibly short-lived floors.

SU3 shows micromorphological features indicative of reworked goat or sheep dung: the presence of spherulite-rich, compact, microlaminated, spongy dung peds with vesicular/moldic porosity.23 These features are better preserved, and the deposit is thicker in Building E−7.1. Such dung deposits have been documented in ethnoarchaeological and archaeological goat and sheep penning contexts, where the goat and sheep dung pellets are partially disintegrated through trampling and dissolution, and their admixture with fodder plant remains commonly results in a compact, microlaminated mixed deposit rich in calcitic fecal spherulites.47,48,49 However, the SU3 dung peds are fragmented and overturned, indicating reworking and a secondary position. This evidence along with the presence of pristine, upright ceramic containers on the deposit’s surface make it unlikely that the buildings were used as livestock pens and more probable that dung was brought in and applied as flooring material.

The relative amount of fecal spherulites observed in the sediments from both buildings is smaller than in published references. This may be due to dissolution under high sedimentary moisture conditions and possibly a low pH, as inferred from the poor preservation state of the few microscopic bone fragments identified. No darkened spherulites50 were observed, indicating that the dung was not subject to burning. In both buildings, the compact dung sediment fragments are surrounded by loose, granular dung-derived sediment, indicative of strong postdepositional reworking (more strongly expressed in E−7), possibly from subsequent anthropogenic activity, as no signs of other geogenic or biogenic processes were observed. The top layer of the sequence in both buildings, identified as a mix of SU2 and SU3 in the field, shows a reworked deposit containing dung peds, clay granules, and archaeological remains (shell, calcitic wood ash, and bone). The microstructure of this upper segment resembles SU5 and SU3b: loose sediment composed of small-sized fragments and granules at the base overlain by more compact, dung-rich sediment. However, in this case, the upper dung-rich segment contains common archaeological remains and could represent the active layer of the floor, into which domestic refuse is trampled.51 The archaeological field data indicates that SU2+3 represents a time-averaged, mixed deposit representing the remains of an architectural collapse on a domestic floor. Our micromorphological samples only show the base of this unit, and no signs of architectural collapse were observed.

Morphogenetic interpretation

The micromorphological data seems to indicate that the life history of the sampled segment of the E−7 and E−7.1 fills was domestic and involved dung, possibly as a construction material. This hypothesis gains further strength in combination with the archaeological field data. From a stratigraphic perspective, the basal units (SU5 and SU3b) could represent foundational or floor preparation layers made up of clay, dung, and minor amounts of wood ash. Micromorphological studies of ethnoarchaeological dung floors report similar features, in addition to the common presence of phytoliths from grass or straw,52 which were not observed here. SU3b, which shows micromorphological evidence of alternating beds of loose clay and dung and compact, laminated dung fragments, could represent an additional step of the foundational process, possibly as insulation material. Archaeological field work has shown a high degree of humidity at the site due to the existence of a poorly drained, natural clayey substrate. Alternatively, SU3b could represent the buildings’ oldest, short-lived dung floors. SU3 possibly represents a massive, long-lived domestic dung floor covering the two connected buildings, which could have been used for food storage, shelter, and/or rest. The rarity of microscopic domestic debris such as charcoal, ash, ceramic, lithic, and bone fragments could be indicative of maintenance activities, as proposed elsewhere.53,54 Finally, SU2 and SU3 could represent the buildings’ last active, trampled domestic dung floor layer. The presence of a few microscopic charcoal, bone, and shell fragments was found in association with the floor deposits and suggest a domestic context.

Fecal biomarkers

The presence of steroids and their combinations in varying ratios confirmed the presence of fecal material in the studied samples. The samples with the highest concentrations of total fecal biomarkers were 3 Sup (≈19.83 μg/g dry sediment) and 3 Inf (≈11.60 μg/g dry sediment) (see Table 1). These high concentrations could be attributed to better organic material preservation or higher deposition of fecal matter. To detect fecal matter, Bull et al. (1999)32 proposed Ratio 1, which combines coprostanol, epicoprostanol, and 5α-cholestanol. According to their research, values higher than 0.7 confirm the presence of feces, while values lower than 0.3 indicate the absence of fecal matter. Although this ratio was calculated for samples 2 + 3, 3 Sup, and 3 Inf, fecal matter was only confirmed for 3 Sup (ratio of 1.00) and 3 Inf (ratio of 1.00).

Bull et al. also proposed Ratio 2, which was later modified by Prost et al. (2017)29 to assess the existence of feces using herbivore stanols (5α-stigmastanol, 5β-stigmastanol, and epi-5β-stigmastanol). The second ratio confirmed the presence of fecal material in sample 2 + 3 (0.80). While for samples 3b and 5 Ratio 1 could not be calculated due to the absence of the target compounds, the values of Ratio 2 (0.86 for sample 3b and 0.98 for sample 5) indicated a fecal origin (values > 0.7). For sample 3 Sup, Ratio 1 confirmed the presence of fecal matter, while Ratio 2 (0.61) neither confirmed nor ruled out the presence of excrement.

It’s worth noting that 5α-stigmastanol can be produced during the microbial degradation of its precursor (β-sitosterol), which is widely present in soils, or it can be found in small amounts in certain plants and animal tissues. Thus, its presence in sediments could be the result of the microbial degradation of plant material deposited in soils by natural or anthropogenic causes or its presence in the plants themselves, affecting the values of the second ratio.

After confirming the presence of fecal material, we calculated additional ratios to investigate its origin. Ratio 3, proposed by Shillito et al. (2011)33 combines coprostanol, epicoprostanol, 5β-stigmastanol, and epi-5β-stigmastanol, while Ratio 4, suggested by Leeming et al. (1997)34 includes coprostanol and 5β-stigmastanol. Ratio 3 values in our samples ranged from 0.00 to 0.16, indicating that the fecal material came from ruminants since the values were significantly below the threshold of 1, which distinguishes ruminant from non-ruminant animals. Ratio 4 values were below 29%, except for sample 5 where it could not be calculated, which is the limit value proposed by Prost et al. (2017)29 to differentiate between herbivore or porcine origin. Additionally, these values fell below the 38% threshold proposed by Leeming et al. (1997)34 for the same purpose. Hence, all our samples contained fecal material of ruminant origin, which is not surprising given that herbivore feces are typically dominated by phytosterols (stigmasterol, β-sitosterol) and their transformation products (5β-stigmastanol, epi-5β-stigmastanol, 5α-stigmastanol), reflecting the plant-based diet of these animals. As mentioned earlier, the highest concentrations of fecal biomarkers in our samples were found for epi-5β-stigmastanol, 5β-stigmastanol, β-sitosterol, and 5α-stigmastanol. However, as Prost et al. (2017)29 noted, the use of Ratio 4 alone may not always enable accurate identification of herbivore feces. Moreover, directly determining the origin of fecal material from different types of ruminant animals based on sterol/stanol markers is not possible as these markers are diet dependent. Therefore, Prost et al.29 proposed combining the results from sterols/stanols with the presence and abundance of bile acids to identify the source of fecal material in archaeological sediments. Reggio et al. (2023)26 relied on this same approach in their studies at the archaeological site 'Le Colombare di Negrar,' detecting fecal matter from goats, cows, sheep, and omnivorous animals. Gea et al. (2017)55 and Vallejo et al. (2022)56 also employed this approach to investigate the origin of such matter in their studies on burned stabling sequences or “fumiers” from San Cristóbal rock shelter (Cantabria, Spain) and El Mirador Cave (Castilla y León, Spain), respectively. The bile acid ratio in fecal matter has also been recently used by Porru et al. (2023)31 as an identification tool. Bile acids are produced during cholesterol metabolism in the liver, excreted in the intestine, and then transformed into secondary bile acids by microorganisms.30,31 Only a small percentage of these secondary bile acids are excreted, as the vast majority are reabsorbed in the intestine. Almost all feces contain appreciable amounts of lithocholic and deoxycholic acids, according to the studies.29,31,55,56 Hyodeoxycholic and ursodeoxycholic acids have only been detected in pig feces, while chenodeoxycholic acid points to horse, goat, or goose. Concentrations of chenodeoxycholic acid in horse and goat feces are lower than that of deoxycholic acid but similar to that of lithocholic acid. Its absence is indicative of donkey or cattle and/or sheep.

Donkey is excluded based on the high concentration of deoxycholic acid relative to lithocholic acid29 (concentration of deoxycholic more than 5 times greater than that of lithocholic) while cow and/or sheep fecal matter is the likely source of samples 3 Sup and 3 Inf. However, given the absence of cow bones in the building’s archaeological record and in sites from the same period (the 14th century), sheep feces appears to be a more plausible source. The origin of samples 5 (containing only lithocholic acid), 2 + 3, and 3b (lacking bile acids) cannot be specified beyond ruminants. In sum, the lipid biomarker data are consistent with the possibility of sheep being housed in the analyzed building or their excrement being used as construction material, specifically in SU3. The presence of other plant-derived lipid compounds could indicate excremental residues of the animals' diet or the use of plants in combination with feces as construction material. Further comparison of the results with other buildings at the site complex could provide more insights into this matter.

Final remarks

The use of dung as a structural material has been documented since the Neolithic period51,52 and has been investigated through ethnoarchaeological approaches.50,55 However, there are no reports of this practice in aboriginal contexts in the Canary Islands. In this case, our lipid biomarker data indicates the use of sheep dung. Further analyses throughout the archaeological site complex and at other pre-European Canarian sites are necessary. A recurrent presence of this feature in different buildings would suggest the systematic use of sheep dung as a construction material, particularly in domestic contexts. Further exploration of other pre-European contexts will allow us to assess if this case represents a cultural tradition or circumstantial.

The results obtained in this microcontextual bioarchaeological study corroborate that the joint application of high resolution geoarchaeological techniques such as lipid biomarkers and micromorphology provide detailed information of great utility to understand aboriginal Canary Islands societies. Specifically, this approach provides relevant information about the composition of the aboriginal livestock, in this case sheep, thus complementing the data generated so far by zooarchaeological studies. It also provides information on aboriginal domestic architecture by showing the existence of prepared floors made of sheep dung.

Limitations of the study

Combining sterols/stanols and bile acids hold great potential for discerning among fecal sources, particularly between sheep and goat, a difficult task due to the morphological similarity of their bones and feces. However, some aspects should be considered. First, the amount of organic matter and the particular sensitivity of the analytical method could produce a biased result, since source identification relies on the presence of particular fecal biomarkers, which may be affected by analyte degradation or dilution. Also, fecal matter exposed to anaerobic processes produces an increase in epi-5β-stanols relative to 5β-stanols. In our particular case, the overall concentration of the selected biomarkers was similar to other contexts in which a high concentration of these compounds was expected.29,55,56 For example, steroids in burnt stabling deposits or “fumiers”55,56 or in archaeological sediment with known or expected fecal input29 showed the same concentration range (55–7431 ng/g) as our samples (6.55–19824.72 ng/g). Thus, we assume that there was no appreciable degradation or dilution effect.

It is also important to highlight that, given the physicochemical properties of the molecules studied, analytical protocols based on liquid chromatography (LC), particularly those coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) or tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), can provide a broader range of diagnostic compounds. In this regard, the studies by Porru et al.25,31 and Vallejo et al.56 have used LC for this purpose, allowing the analysis of up to ∼30 bile acids and metabolites in some cases.25,31 In any case, the good results obtained in this study and in previous publications show that GC-MS (which is conceptually and experimentally simpler than LC) can be a suitable alternative.

Another important limitation is that cattle and sheep feces cannot be distinguished due to their similar biomarker profiles. Fortunately, cows were not introduced in the Canary Islands until the arrival of Castilians, so we deduce that our fecal biomarkers represent sheep.

Other aspects to consider are the type of livestock fodder and the possible mixing of feces in the sediment. Both factors could strongly modify the compounds present and their ratios. Experimentation with feces and feces mixtures of typical aboriginal livestock animals with variable diets would be a valuable reference and enhance a more complete and accurate interpretation of site use, livestock diet, and technology at La Fortaleza and other Canary Islands aboriginal sites.

Additional experimental research is necessary to establish a comprehensive reference framework for the micromorphological analysis of prepared dung floors. Currently, these floors are primarily identified by their composition as reworked dung material. It is essential to gather insights into potential construction techniques that might have given rise to the microstructures observed at La Fortaleza. Furthermore, it is important to extend this analysis to other archaeological buildings within the pre-Hispanic settlement of La Fortaleza, as well as others across the entirety of Gran Canaria. This broader investigation aims to unveil discernible patterns that, when combined with other contextual indicators, can facilitate a more holistic understanding of the functional aspects of these buildings.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCEkey-resources-table | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Dichloromethane (purity ≥ 99.8%, Chromasolv® for HPLC grade) | Honeywell | CAS: 75-09-2 |

| Methanol (purity ≥ 99.9%, Chromasolv® for HPLC grade) | Honeywell | CAS: 67-56-1 |

| Hexane (purity ≥ 97%, Chromasolv® for HPLC grade) | Honeywell | CAS: 110-54-3 |

| 2-Propanol (purity ≥ 99.9%, Chromasolv® for HPLC grade) | Honeywell | CAS: 67-63-0 |

| Diethyl ether (purity ≥ 99 for HPLC) | Acrōs Organics | CAS: 60-29-7 |

| Potassium hydroxide (purity ≥ 85%) | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 1310-58-3 |

| Hydrochloric acid (≥37%) | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 7647-01-0 |

| Acetic acid glacial (100%) | Merck | CAS: 64-19-7 |

| Sulfuric acid (purity: 95.0-97.0%) | Honeywell | CAS: 7664-93-9 |

| Sodium hydrogen carbonate | Merck | CAS: 144-55-8 |

| Discovery® DSC-NH2 SPE Bulk Packing | Supelco | Cat#57212-U |

| Silica gel (technical grade, pore size 60Å, 70-230 mesh, 63-200 μm) | Supelco | CAS: 112926-00-8 |

| Sand (50-70 mesh) | Sigma Aldrich | CAS: 14808-60-7 |

| N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide with trimethylchlorosilane (99:1) | Sigma Aldrich | CAS: 25561-30-2 |

| 5α-androstan-3β-ol | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 1224-98-6 |

| Cholesterol | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 474-25-9 |

| β-Sitosterol | Supelco | CAS: 83-46-5 |

| Coprostanol | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 360-68-9 |

| 5α-Stigmastanol | Cayman Chemical | CAS: 83-45-4 |

| Cholestanol | Avanti Polar Lipids | CAS: 80-97-7 |

| Hyocholic acid | Avanti Polar Lipids | CAS: 547-75-1 |

| Hyodeoxycholic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 83-49-8 |

| Lithocholic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 434-13-9 |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 128-13-2 |

| Deoxycholic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 83-44-3 |

| Chenodeoxycholic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS: 474-25-9 |

| Palatal P4-01 strained resin | TNK composites | Cat#UN1866 |

| Styrene monomer | TNK composites | CAS: 100-42-5 |

| Methyl-ethyl-ketone | TNK composites | CAS: 78-93-3 |

| Milli-Q® water | Millipore | CAS: 7732-18-5 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MassHunter Workstation Software | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/product/software-informatics/mass-spectrometry-software |

| NIST Mass Spectral Search Program version 2.2 | Standard Reference Program of the National Institute of Standards and Technology | https://chemdata.nist.gov/dokuwiki/doku.php?id=chemdata:start |

| Excel 2013 | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/es-es/microsoft-365/previous-versions/microsoft-office-2013 |

| Other | ||

| Whatman glass microfiber filters, Grade GF/F | Whatman | Cat#WHA1825110 |

| Ultrasonic bath USC 600T | VWR International | Cat#142-0090 |

| Centrifuge Mega Star 1.6 | VWR International | Cat#521-2659 |

| N2 RapidVap® Vertex Evaporator | Labconco | Cat#7320037 |

| pHmeter Sension+ PH3 | Hach | Cat#LPV2021T.98.002 |

| Vortex Genie 2 | Scientific Industries | Cat#SI-0256 |

| N2 evaporator 24 positions N-EVAP | Organomation Associates Inc | Cat#11250 |

| Agilent 7890B GC System | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/product/gas-chromatography/gc-systems/7890b-gc-system |

| Agilent 5977A MSD | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/promotions/gc-gcms-resolve |

| Agilent HP-5ms capillary column (length: 30 m, ID: 250 μm, 0.25 μm film thickness) | Agilent Technologies | Cat#19091S-433UI |

| Radial saw Euro-Shatal TS351 | Euro Shatal | https://www.shatal.com/category/ts351 |

| Precision cutting machine Uniprec ATA Brillant-220 | Neurtek | https://www.neurtek.com/descargas/atm_brillant_220_en.pdf |

| Grinding machine G&N MPS-RC | G&N | https://grinders.de/en/product/mps-rc-metal/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Antonio V. Herrera Herrera (avherrer@ull.edu.es).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Microscopy and chromatography data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

The horizontal and vertical dispersion maps of archaeological materials, the inventory of archaeological remains and their association with SU will be shared upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Method details

Site and sample selection

La Fortaleza stands as a significant archaeological complex in Gran Canaria, showcasing evidence of continuous human habitation dating back to the island's initial settlement by Berber groups around the 3rd century AD,57 and extending through to the Castilian conquest in 1486. It is the longest known archaeological stratified sequence in the Canary Islands. The complex is located along two promontories, La Fortaleza Chica and La Fortaleza Grande, at the southern limit of Tirajana caldera (510 m above sea level) in Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, 27° 52' 59.456''N, 15° 31' 44.72'' W) (Figure 1). This area has a semi-arid climate, with scarce water sources, mean average annual rainfall of 270 mm and mean annual temperatures around 16°C.

The complex is made up of 51 sites (50 cave sites and one large open-air site with numerous buildings) and represents the longest-lived pre-Hispanic settlement of Gran Canaria.38 Current radiocarbon dates place the settlement between the 5th and 15th centuries AD.36 The earliest occupations are represented by funerary, dwelling and storage caves, while the domestic open-air contexts date to the 13th and 15th centuries AD. Altogether, the sites within the complex have yielded evidence of all the different archaeological manifestations known for pre-Hispanic Gran Canaria: domestic dwellings, granaries and other food storage facilities, cementeries, spaces used for ritual activities and rock art. Thus, we can approach different aspects of the social and economic evolution of the island’s Amazigh population who lived there for over one thousand years.36

Existence of La Fortaleza site was first mentioned in mid-16th century land holding documents and late 19th century anthropological descriptions.36,58 The first excavations were carried out in the 1990s, followed by renewed working at the site complex in 2012 and until the present day.

The analyzed sediment samples were collected from buildings E-7 and E-7.1, to the west of La Fortaleza Grande promontory. The upper building (E-7), was excavated for the first time in 2020, through a series of small test pits (5) in its interior and exterior adjacent surrounding. It is a stone-walled building with a central space, a smaller side room and a south-facing entrance corridor. Its total interior surface area is approximately 20.00 m2and its preserved maximum height is 2.00 m. This building’s morphology has been documented in other Gran Canarian pre-Hispanic sites of similar chronology.37,59,60 Building E-7.1 has been fully excavated (in 1992 and 2017). It is an oval stone-walled structure with a small side room (E-7.2) and no direct outdoor access. The dimensions of E-7.1 are 4.60 m in length x 4.00 m in width, with an approximate interior surface area of 9.00 m2, and a preserved maximum height of 2.25 m. Additionally, the E-7.2 annex has a maximum length of 2.20 m, a width of 2.00 m and an approximate surface area of 4 m2. E-7.1 is at a slightly lower elevation than E-7 and both buildings are connected by a threshold with three steps (Figures 2A and 2B).61

Both buildings are partially filled by a stratified sedimentary deposit (50 cm thick in E-7 and 40-50 cm-thick in E-7.1), stratigraphically correlated in the field and divided into 4 units (Table S3).

In 2016, two micromorphological samples were collected from Building E-7.1 and in 2020, a micromorphology sample and stratigraphically associated bulk sediment samples for lipid analysis were collected from Building E-7. The samples covered the buildings' exposed stratigraphic sequence (2+3, 3, 3b and 5). For the lipid analysis sampling, SU3, the unit of hypothetical excrement content, was divided into two samples (3sup and 3inf) (Figure 2C). The micromorphology samples were wrapped in plaster of Paris before extraction. The bulk sediment samples for lipid analysis were taken using metal tools and nitrile gloves and wrapped in aluminum foil. To avoid degradation by bacterial action, they were stored at -20°C.62

Soil micromorphology

The micromorphological sample from Building E-7 was processed at the Archaeological Micromorphology and Biomarkers Laboratory (AMBI Lab) following the method described by Leierer et al.63 The protocol consists of : 1) drying the block for 48 h at 60°C and impregnating it with a mixture of polyester:styrene:methyl ethyl ketone resin 7:3:0.1 v/v/v/v; 2) cutting into1-cm-thick plates with a radial saw (Euro-Shatal); 3) gluing onto 9×6-cm glass slides; 4) cutting to 1 mm with a precision cutting machine (Uniprec) and 5) grinding to 30 μm with a precision grinding machine (G&N). The Building E-7.1 samples were processed at the Universitat de Lleida thin sectioning facility. The resulting thin sections (4 from E-7 and 11 from E-7.1) were analyzed with petrographic microscopes in plane polarized light (PPL) and cross polarized light (XPL). Standard guidelines defined by Stoops (2003),43 Nicosia and Stoops (2017)44 and Stoops et al. (2018)45 were followed for the identification and description of micromorphological features to facilitate the identification of depositional and post-depositional processes.

Lipid biomarker extraction

Solvents and standards were used as received without further purification. Lipid biomarkers were extracted following a procedure similar to those used by Herrera-Herrera & Mallol64 and Jambrina-Enríquez et al.65 Samples were dried at 60°C for 48 h, ground with an agate mortar and homogenized. Then, 5.0000 ± 0.1000 g of sample were mixed with 40 mL of a dichlorometane:methanol (DCM:MeOH) 3:1 v/v mixture to extract the total lipid extract (TLE). After sonication (ultrasonic bath USC 600T from VWR International) for 30 min and centrifugation at 4700 rpm for10 min (Mega Star 1.6 from VWT International), the extracts were filtered through pyrolyzed glass wool (450°C for 10 h) and glass microfiber filter (Whatman). The remaining solid was re-extracted twice more and the combined extract was evaporated at 40°C by N2 flow (RapidVap® Vertex Evaporator from Labconco).

The protocol developed by Elhmmali et al.66 was adapted to obtain fecal biomarkers (sterols, stanols and bile acids). To release esterified compounds, TLE was saponified by adding 5 mL of 5M KOH in 90% v/v MeOH and heating at 100°C for 1h. Then, 20 mL of Milli-Q® water were added and the samples were acidified to a pH between 3 and 4 (pHmeterSension+ pH3) with HCl 6M. Neutral and acidic molecules were extracted by adding 10 mL of DCM (3 times) and vortex mixing (Vortex Genie-2 from Scientific Industries). The combined extracts were then dried and reconstituted in 1 mL hexane to separate the compounds by solid-phase extraction (SPE) with a polymerically bonded aminopropyl column (500 mg, Supelco). For this purpose, the SPE columns were activated with 6 mL of hexane and the neutral alcoholic fraction was eluted with 6 mL of DCM:2-propanol 2:1 v/v mixture, while carboxylic acids were eluted using 12 mL of 3% v/v acetic acid in diethyl ether.

After drying, carboxylic acids were subsequently derivatized to their methyl esters by adding 5 mL of MeOH and 400 μl H2SO4 and heating at 70°C for 240 min.67 In this step, hyocholic acid (3μL 400 mg/L) was added as an internal standard. Once the esterification was completed, the samples were neutralized with 10 mL saturated NaHCO3 and the methyl esters were extracted with 3x3 mL of hexane. After drying under a N2 flow, the methylated carboxylic acids (including bile acids) were fractionated using a silica gel SPE column (600 mg sorbent). The reconstituted samples in 1 mL of DCM:hexane 2:1 v/v were transferred to the columns and 5 mL of DCM:hexane 2/1 v/v and DCM:MeOH 2:1 v/v were used to elute monocarboxylic fatty acids methyl esters and hydroxy carboxylic acid methyl esters (including bile acids), respectively. The eluted compounds were dried under N2 and stored until analysis.

GC-MS analysis

Steroids and bile acids were sylilated for GC-MS analysis. With this aim, 5α-androstan-3β-ol (1 μL, 400 mg/L) was added as internal standard. The different fractions previously obtained were dissolved in 200 μL of DCM and mixed with 100 μL of N,O-Bis(tri-methylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) + trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) 99:1 v/v to obtain the corresponding trimethylsilyl (TMS) ethers. After 60 min at 80°C, the samples were dried to remove any remaining unreacted BSTFA and reconstituted with 50 μL DCM. 1 μL of these final samples was injected in triplicate into the GC system.

The GC-MS instrument (7890B GC + 5977A MSD, Agilent Technologies) was equipped with a multimode injector (MMI) programmed at an initial temperature of 70°C for 0.85 min, and heated to 300°C, at a rate of 720°C/min at the split ratio 5:1. Separation was carried out on a (5% phenyl) -metipolysiloxane fused silica capillary column (30 m x 250 μm, 0.25 μm thickness; Agilent Technologies) initially programmed at 70°C (held 2 min). The temperature was then increased to 140°C (heating rate: 12°C/min) and finally to 320°C (heating rate: 3°C/min, held 15 min). Helium was used as the mobile phase at a flow of 1 mL/min. The temperatures of transfer line, ion source and quadrupole were set at 280, 230 and 150°C, respectively. The quadrupole analyzer was operated in fullscan mode (m/z 40-580), the electron ionization energy was established at -70 eV, and the solvent delay was 7 min.

Compound identification was carried out by comparison of the retention time with those of authentic standards injected in the same chromatographic conditions, inspection of peak signals of specific ion fragments,29 and reference spectra obtained from the NIST mass spectra library and pure derivatized standard injections (Table S1).

Quantification and statistical analysis

The compounds were quantified using instrumental calibration curves (Apeak/AIS vs concentration) obtained by injecting analytes in triplicate into the GC-MS system at 6 different levels of concentrations. Quantification was carried out taking the most intense and specific fragment ions (Table S1 for further information). Table S2 shows the results for this calibration study, including the tested concentration range, the calibration curve with confidence intervals and the determination coefficients (R2), higher than 0.9900 for all the analytes. IUPAC recommends the Mandel’s test to check the best fit for the calibration curve (linear or quadratic).68 This test compares the residual standard deviations of non-linear and linear models through an F-test. The null hypothesis establishes that the variance explained by the introduction of non-linear terms is not different from the residual variance. When the null hypothesis cannot be rejected both (linear and non-linear) models estimate the residual variance while if the alternative hypothesis is confirmed (Fexp>Ftab (α, 1, n-3)) the non-linear equation fits better the data. The F exp is calculated through the following formula which involves the degrees of freedom for the linear and non-linear models68:

where Sy/x,lin and Sy/x,cuad are the residual standard deviations for the linear and quadratic model (respectively) and n is the number of levels of concentration. In this case Fexp (22.51-84.33) was far superior to Ftab (10.13 for α = 0.05, numerator degrees of freedom = 1, n − 3 = 3), except for 5α-stigmastanol. Thus, quadratic model was used for quantification for almost all the analytes.

The matrix effect was evaluated using the Matuszewski method69 (Table S2). To achieve this, three consecutive extractions were performed, and the resulting extracts were spiked (concentrations between 5 and 37.5 mg/L vial) before being injected into the instrument. Subsequently, standards were injected into the solvent at the same concentrations, and the matrix effect was calculated as the percentage ratio of areas between the spiked extract and the standard in the solvent. The matrix effects ranged from 70% (RSD: 2%) for ursodeoxycholic acid to 104% (RSD: 3%) for cholesterol. Only a few analytes (chenodeoxycholic, hyodeoxycholic and ursodeoxycholic acids) were affected by matrix effects (values out of the range 80–120%), specifically by a slight signal suppression. To assess the efficiency and reproducibility of the extraction procedure, a recovery study was conducted at various concentration levels. Sterols were tested at concentrations ranging from 50 to 100 ng/g of dry sediment, while bile acids were tested at 375 ng/g of dry sediment. Three samples were spiked and extracted for this purpose (n=3). The study involved comparing the peak areas of the analytes in samples spiked at the beginning and end of the extraction process. The obtained recovery values (Table S2) ranged from 63% for coprostanol to 108% for cholestanol, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) between 5% for cholestanol and 13% for chenodeoxycholic acid. Limits of detection (LODs) and limit of quantification (LOQs) were calculated based on the recommendations of the ICH guideline, considering preconcentration/dilution factors. Thus, the detection limit was calculated as the concentration that provides a signal-to-noise ratio equal to 3, and the quantification limit was calculated as the concentration that provides a value equal to 10. The obtained LOQ values ranged between 2.2 ng/g-0.1 μg/g dry sediment, demonstrating the good sensitivity of the method.

Once the fecal biomarkers were quantified, the following ratios were calculated to confirm the presence of excrements and try to identify its animal source:

Ratio 1 (Bull et al.32): Identification of presence or absence of fecal material. Values higher than 0.7confirm the presence of dung and lower than 0.3 discard the feces presence. Between 0.3 and 0.7 the ratio does not allow to determine presence or absence of fecal matter.

Ratio 2 (Bull et al.32 modified by Prost et al.29): Similarly to ratio 1 (but using herbivore stanols) indicates the presence or absence of fecal material.

Ratio 3 (Shillito et al.33): Indication of ruminant (<1) or non-ruminant (pig/human, >1) feces:

Ratio 4 (Leeming et al.34, Prost et al.29): Allows to identify the origin of the fecal matter in the sample. According to Prost et al. a value lower than 29% indicates that the feces are from an herbivorous animal, higher than 65% confirms human origin, and between the above values the source is pig. On contrast Leeming et al.34 established that values below 38% indicate herbivores, while values above 73% indicate humans:

Moreover, the presence/absence, relative proportion and threshold values (as indicated by Prost et al.29) for bile acids were considered.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by Project 77/2021 of the Servicio de Patrimonio Cultural del Gobierno de Canarias and Tibicena Arqueología y Patrimonio S.L., with additional support from European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant project PALEOCHAR – 648871.

Author contributions

A.V.H.H.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, and writing-original draft; H.P.H: validation, formal analysis, and investigation; E.I.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing- review and editing; V.A.B.: investigation, resources, writing- review and editing, and funding acquisition; M.A.M.B.: investigation, resources, writing- review and editing, and funding acquisition; C.M.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing- review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: February 9, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109171.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Henríquez-Valido P., Morales J., Vidal-Matutano P., Santana-Cabrera J., Rodríguez Rodríguez A. Arqueoentomología y arqueobotánica de los espacios de almacenamiento a largo plazo: el granero de Risco Pintado, Temisas (Gran Canaria) Trab. Prehist. 2019;76:120–137. doi: 10.3989/tp.2019.12229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morales Mateos J., Rodríguez Cainzos A., Henríquez Valido P. In: Miscelánea en homenaje a Lydia Zapata Peña (1965-2015) Fernández Eraso J., Mujika Alustiza J.A., Arrizabalaga Valbuena Á., García Diez M., editors. Universidad del País Vasco); 2017. Agricultura y recolección vegetal en la arqueología prehispánica de las Islas Canarias (siglos III-XV d.C.): la contribución de los estudios carpológicos; pp. 189–218. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vidal-Matutano P., Morales J., Henríquez-Valido P., Marchante-Ortega Á., Moreno-Benítez M.A., Rodríguez-Rodríguez A. Wood use in pre-hispanic (ca. 500-1500 ad) communal granaries: Xylological and anthracological analyses from La Fortaleza (Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Gran Canaria) Vegueta. 2020;20:469–489. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomé L., Jambrina-Enríquez M., Égüez N., Herrera-Herrera A.V., Davara J., Marrero Salas E., Arnay de la Rosa M., Mallol C. Fuel sources, natural vegetation and subsistence at a high-altitude aboriginal settlement in Tenerife, Canary Islands: Microcontextual geoarchaeological data from Roques de García Rockshelter. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022;14:195. doi: 10.1007/s12520-022-01661-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henríquez-Valido P., Morales J., Vidal-Matutano P., Moreno-Benítez M., Marchante-Ortega Á., Rodríguez-Rodríguez A., Huchet J.-B. Archaeoentomological indicators of long-term food plant storage at the Prehispanic granary of La Fortaleza (Gran Canaria, Spain) J. Archaeol. Sci. 2020;120 doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2020.105179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellano-Alonso P., Moreno-García M., Rodríguez Rodríguez A., Sáenz Sagasti J.I., Onrubia Pintado J. Gestión de la ganadería y patrones de consumo de una comunidad indígena expuesta al fenómeno colonial: el caso de la Estructura 12 de la Cueva Pintada (Gran Canaria, España) A. 2018;27:37–56. doi: 10.15366/archaeofauna2018.27.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberto-Barroso V., Moreno-Benítez M., Alamón-Núñez M., Suárez-Medina I., Mendoza-Medina F. Estudio zooarqueológico de la Restinga (Gran Canaria, España). Datos para la definición de un modelo productivo. XXII. Coloq. Hist. Canar. XXII–. 2016;137:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez Santana C.G. 1994. Las ictiofaunas arqueológicas del Archipiélago Canario: una aproximación a la pesca pre-histórica. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fregel R., Ordóñez A.C., Santana-Cabrera J., Cabrera V.M., Velasco-Vázquez J., Alberto V., Moreno-Benítez M.A., Delgado-Darias T., Rodríguez-Rodríguez A., Hernández J.C., et al. Mitogenomes illuminate the origin and migration patterns of the indigenous people of the Canary Islands. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ordóñez A.C., Fregel R., Trujillo-Mederos A., Hervella M., de-la-Rúa C., Arnay-de-la-Rosa M. Genetic studies on the prehispanic population buried in Punta Azul cave (El Hierro, Canary Islands) J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017;78:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarro Mederos J.F. Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria; 2019. Los Aborígenes 4a ed. rev. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velasco Vázquez J. Economía y dieta de las poblaciones prehistóricas de Gran Canaria. Una aproximación bioantropológica. Complutum. 1998;9:137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnay-de-la-Rosa M., González-Reimers E., Yanes Y., Velasco-Vázquez J., Romanek C.S., Noakes J.E. Paleodietary analysis of the prehistoric population of the Canary Islands inferred from stable isotopes (carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen) in bone collagen. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010;37:1490–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberto-Barroso V., Delgado-Darias T., Moreno-Benítez M., Velasco-Vázquez J. Cabildo de Gran Canaria; 2023. Migrantes y Nativas. Diálogo de identidades a través del tiempo Serie la I. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delgado-Darias T., Alberto-Barroso V., Velasco-Vázquez J. Living on an island. Cultural change, chronology, and climatic factors in the relationship with the sea among canarian-amazigh populations on Gran Canaria (Canary Islands) Quat. Sci. Rev. 2023;303 doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.107978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales J., Rodríguez-Rodríguez A., González-Marrero M.d.C., Martín-Rodríguez E., Henríquez-Valido P., Henríquez-Valido P., del-Pino-Curbelo M. The archaeobotany of long-term crop storage in northwest African communal granaries: a case study from pre-Hispanic Gran Canaria (cal. ad 1000–1500) Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2014;23:789–804. doi: 10.1007/s00334-014-0444-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morales J., Speciale C., Rodríguez-Rodríguez A., Henríquez-Valido P., Marrero-Salas E., Hernández-Marrero J.C., López R., Delgado-Darias T., Hagenblad J., Fregel R., Santana J. Agriculture and crop dispersal in the western periphery of the Old World: the Amazigh/Berber settling of the Canary Islands (ca. 2nd–15th centuries ce) Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00334-023-00920-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boessneck J. In: Ciencia en arqueología. Brothwell D., Higgs E., editors. Fondo de Cultura Económica; 1980. Diferencias osteológicas entre las ovejas (Ovis aries Linné) y cabras (Capra hircus Linné) pp. 338–366. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaastra J.S. Domesticating details: 3D geometric morphometrics for the zooarchaeological discrimination of wild, domestic and proto-domestic sheep (Ovis aries) and goat (Capra hircus) populations. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2023;151 doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alberto-Barroso V., Navarro-Mederos J.F., Castellano-Alonso P. Animales y ritual. Los registros fáunicos de las aras de sacrificio del Alto de Garajonay (La Gomera, Islas Canarias) Zephyrus Rev. Prehist. y Arqueol. 2015;76:159–179. doi: 10.14201/ZEPHYRUS201576159179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brönnimann D., Ismail-Meyer K., Rentzel P., Pümpin C., Lisá L. Archaeological Soil and Sediment Micromorphology. 2017. Excrements of Herbivores; pp. 55–65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canti M.G., Brochier J.É. Archaeological Soil and Sediment Micromorphology. 2017. Faecal Spherulites; pp. 51–54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macphail R.I., Courty M.-A., Hather J., Wattez J., Ryder M., Cameron N., Branch N.P. Mem. dell’Istituto Ital. di Paleontol. Um; 1997. The Soil Micromorphological Evidence of Domestic Occupation and Stabling Activities. Arene Candide a Funct. Environ. Assess. Holocene Seq. (Excavations Bernabò Brea-Cardini 1940–50) pp. 53–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bull I.D., Elhmmali M.M., Roberts D.J., Evershed R.P. The Application of Steroidal Biomarkers to Track the Abandonment of a Roman Wastewater Course at the Agora (Athens, Greece) Archaeometry. 2003;45:149–161. doi: 10.1111/1475-4754.00101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porru E., Giorgi E., Turroni S., Helg R., Silani M., Candela M., Fiori J., Roda A. Bile acids and oxo-metabolites as markers of human faecal input in the ancient Pompeii ruins. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:3650. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82831-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reggio C., Palmisano E., Tecchiati U., Ravelli A., Bergamaschi R.F., Salzani P., Putzolu C., Casati S., Orioli M. GC–MS analysis of soil faecal biomarkers uncovers mammalian species and the economic management of the archeological site “Le Colombare di Negrar.”. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:5538. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32601-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shillito L.M., Whelton H.L., Blong J.C., Jenkins D.L., Connolly T.J., Bull I.D. Pre-Clovis occupation of the Americas identified by human fecal biomarkers in coprolites from Paisley Caves, Oregon. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba6404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sistiaga A., Mallol C., Galván B., Summons R.E. The Neanderthal Meal: A New Perspective Using Faecal Biomarkers. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prost K., Birk J.J., Lehndorff E., Gerlach R., Amelung W. Steroid Biomarkers Revisited – Improved Source Identification of Faecal Remains in Archaeological Soil Material. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vázquez C., Vallejo A., Vergès J.M., Barrio R.J. Livestock activity biomarkers: Estimating domestication and diet of livestock in ancient samples. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porru E., Scicchitano D., Interino N., Tavella T., Candela M., Roda A., Fiori J. Analysis of fecal bile acids and metabolites by high resolution mass spectrometry in farm animals and correlation with microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:2866. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06692-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bull I.D., Simpson I.A., van Bergen P.F., Evershed R.P. Muck ‘n’ molecules: organic geochemical methods for detecting ancient manuring. Antiquity. 1999;73:86–96. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X0008786X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shillito L.-M., Bull I.D., Matthews W., Almond M.J., Williams J.M., Evershed R.P. Biomolecular and micromorphological analysis of suspected faecal deposits at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011;38:1869–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.03.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leeming R., Latham V., Rayner M., Nichols P.D. In: Molecular markers in environmental geochemistry. Eganhouse R.P., editor. American Chemical Society; 1997. Detecting and distinguishing sources of sewage pollution in Australian inland and coastal waters and sediments. Molecular Markers in Environmental Geochemistry; pp. 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernández-Palacios E., Jambrina-Enríquez M., Mentzer S.M., Rodríguez de Vera C., Dinckal A., Égüez N., Herrera-Herrera A.V., Navarro Mederos J.F., Marrero Salas E., Miller C.E., Mallol C. Reconstructing formation processes at the Canary Islands aboriginal site of Belmaco Cave (La Palma, Spain) through a multiproxy geoarchaeological approach. Geoarchaeology. 2023;38:713–739. doi: 10.1002/geo.21972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno-Benítez M.A., Alberto-Barroso V., Mendoza-Medina F., Suárez-Medina I. La Fortaleza, tres en uno. Caracterización arqueológica de un espacio aborigen de larga duración. Anu. Estud. Atlánticos. 2023;69:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Onrubia Pintado J. Cabildo de Gran Canaria; 2004. La isla de los “Guanartemes”: territorio, sociedad y poder en la Gran Canaria indígena : (siglos XIV-XV) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno-Benítez M. Tibicena Publicaciones. (Tibicena Publicaciones; 2020. El Tiempo Perdido. Un relato arqueológico de la Tirajana Indígena. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreno-Benítez M.A. Tibicena Publicaciones; 2022. La Fortaleza. Un Espacio Contra El Olvido. 978-84-948109-3-0. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodríguez Rodríguez A., Galindo Rodríguez A. Ingenio; 2004. El aprovechamiento de recursos abióticos en un poblado costero de la isla de Gran Canaria. Las industrias líticas del yacimiento de El Burrero. [Google Scholar]

- 41.del Pino Curbelo M., Rodríguez Rodríguez A.D.C., del C. Propuesta para la clasificación de los materiales cerámicos de tradición aborigen de la isla de Gran Canaria (Islas Canarias) Lucentum. 2017;0:9–31. doi: 10.14198/LVCENTVM2017.36.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morales Mateos J. Cabildo de Gran Canaria; 2019. Los guardianes de las semillas. Origen y evolución de la agricultura en Gran Canaria. Serie La Isla de los Canarios no2. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoops G. In: Guidelines for Analysis and Description of Soil and Regolith Thin Sections. Vepraskas M.J., editor. Soil Science Society of America; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicosia C., Stoops G. In: Archaeological Soil and Sediment Micromorphology C. Nicosia and. Stoops G., editor. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoops G., Marcelino V., Mees F., editors. Interpretation of Micromorphological Features of Soils and Regoliths. Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller C.E., Conard N.J., Goldberg P., Berna F. Dumping, sweeping and trampling: experimental micromorphological analysis of anthropogenically modified combustion features. Palethnologie. 2010;2:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shahack-Gross R., Marshall F., Weiner S. Geo-Ethnoarchaeology of Pastoral Sites: The Identification of Livestock Enclosures in Abandoned Maasai Settlements. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2003;30:439–459. doi: 10.1006/jasc.2002.0853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shahack-Gross R. Herbivorous livestock dung: formation, taphonomy, methods for identification, and archaeological significance. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011;38:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polo Díaz A., Martínez-Moreno J., Benito-Calvo A., Mora R. Prehistoric herding facilities: site formation processes and archaeological dynamics in Cova Gran de Santa Linya (Southeastern Prepyrenees, Iberia) J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014;41:784–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Canti M.G., Nicosia C. Formation, morphology and interpretation of darkened faecal spherulites. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2018;89:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2017.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gé T., Courty M.A., Matthews W., Wattez J. In: Formation Processes in Archaeological Context. Goldberg P., Nash D.T., Petraglia M.D., editors. Prehistory Press; 1993. Sedimentary formation processes of occupation surfaces; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berna F. Geo-ethnoarchaeology study of the traditional Tswana dung floor from the Moffat Mission Church, Kuruman, North Cape Province, South Africa. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017;9:1115–1123. doi: 10.1007/s12520-017-0470-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schiffer M.B. Toward the Identification of Formation Processes. Am. Antiq. 1983;48:675–706. doi: 10.2307/279771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomé L., Iriarte E., Blanco-González A., Jambrina-Enríquez M., Égüez N., Herrera-Herrera A.V., Mallol C. Searching for traces of human activity in earthen floor sequences: high-resolution geoarchaeological analyses at an Early Iron Age village in Central Iberia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2024;161 doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gea J., Sampedro M.C., Vallejo A., Polo-Díaz A., Goicolea M.A., Fernández-Eraso J., Barrio R.J. Characterization of ancient lipids in prehistoric organic residues: Chemical evidence of livestock-pens in rock-shelters since early neolithic to bronze age. J. Sep. Sci. 2017;40:4549–4562. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201700692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vallejo A., Gea J., Gorostizu-Orkaiztegi A., Vergès J.M., Martín P., Sampedro M.C., Sánchez-Ortega A., Goicolea M.A., Barrio R.J. Hormones and bile acids as biomarkers for the characterization of animal management in prehistoric sheepfold caves: El Mirador case (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain) J. Archaeol. Sci. 2022;138 doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2022.105547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Velasco-Vázquez J., Alberto-Barroso V., Delgado-Darias T., Moreno-Benítez M., Lecuyer C., Richardi P. Poblamiento, colonización y primera historia de Canarias: el C14 como paradigma. Anu. Estud. Atlánticos. 2019;66:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlueter-Caballero R. La Fortaleza Santa Lucía de Tirajana. Investigación arqueológica. Boletín Millares Carlo. 2009;28:31–70. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alberto-Barroso V., Velasco-Vázquez J., Delgado-Darias T., Moreno-Benítez M.A. Cemeteries, social change and migration in the time of the Ancient Canarians. tabona. 2022;22:407–433. doi: 10.25145/j.tabona.2022.22.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martín de Guzmán C. Cabildo de Gran Canaria; 1984. Las culturas prehistóricas de Gran Canaria. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moreno-Benítez M.A., Mendoza-Medina F., Suárez-Medina I., Alberto-Barroso V., Martínez Torcal M.A. Un día cualquiera en la fortaleza. Resultados de las intervenciones arqueológicas 2015-2016 (Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Gran Canaria). XXII Coloq. Hist. Canar. XXII–. 2017;136:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brittingham A., Hren M.T., Hartman G. Microbial alteration of the hydrogen and carbon isotopic composition of n-alkanes in sediments. Org. Geochem. 2017;107:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leierer L., Jambrina-Enríquez M., Herrera-Herrera A.V., Connolly R., Hernández C.M., Galván B., Mallol C. Insights into the timing, intensity and natural setting of Neanderthal occupation from the geoarchaeological study of combustion structures: A micromorphological and biomarker investigation of El Salt, unit Xb, Alcoy, Spain. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herrera-Herrera A.V., Mallol C. Quantification of lipid biomarkers in sedimentary contexts: Comparing different calibration methods. Org. Geochem. 2018;125:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jambrina-Enríquez M., Herrera-Herrera A.V., Mallol C. Wax lipids in fresh and charred anatomical parts of the Celtis australis tree: Insights on paleofire interpretation. Org. Geochem. 2018;122:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2018.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elhmmali M.M., Roberts D.J., Evershed R.P. Bile Acids as a New Class of Sewage Pollution Indicator. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997;31:3663–3668. doi: 10.1021/es9704040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jambrina-Enríquez M., Herrera-Herrera A.V., Rodríguez de Vera C., Leierer L., Connolly R., Mallol C. n-Alkyl nitriles and compound-specific carbon isotope analysis of lipid combustion residues from Neanderthal and experimental hearths: Identifying sources of organic compounds and combustion temperatures. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019;222 doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andrade J.M., Gómez-Carracedo M.P. Notes on the use of Mandel’s test to check for nonlinearity in laboratory calibrations. Anal. Methods. 2013;5:1145–1149. doi: 10.1039/c2ay26400e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matuszewski B.K., Constanzer M.L., Chavez-Eng C.M. Strategies for the assessment of matrix effect in quantitative bioanalytical methods based on HPLC-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3019–3030. doi: 10.1021/ac020361s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Microscopy and chromatography data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

The horizontal and vertical dispersion maps of archaeological materials, the inventory of archaeological remains and their association with SU will be shared upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.