Abstract

Background

Uptake of postnatal care (PNC) is low and inequitable in many countries, and immigrant women may experience additional challenges to access and effective use. As part of a larger study examining the views of women, partners, and families on routine PNC, we analysed a subset of data on the specific experiences of immigrant women and families.

Methods

This is a subanalysis of a larger qualitative evidence synthesis. We searched MEDLINE, PUBMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, EBM-Reviews and grey literature for studies published until December 2019 with extractable qualitative data with no language restrictions. For this analysis, we focused on papers related to immigrant women and families. Two reviewers screened each study independently; inclusion was agreed by consensus. Data abstraction and quality assessment were carried out using a study-specific extraction form and established quality assessment tools. Study findings were identified using thematic analysis. Findings are presented by confidence in the finding, applying the GRADE-CERQual approach.

Findings

We included 44 papers, out of 602 full-texts, representing 11 countries where women and families sought PNC after immigrating. All but one included immigrants to high-income countries. Four themes were identified: resources and access, differences from home country, support needs, and experiences of care. High confidence study findings included: language and communication challenges; uncertainty about navigating system supports including transportation; high mental health, emotional, and informational needs; the impact of personal resources and social support; and the quality of interaction with healthcare providers. These findings highlight the importance of care experiences beyond clinical care. More research is also needed on the experiences of families migrating between low-income countries.

Conclusions

Immigrant families experience many challenges in getting routine PNC, especially related to language, culture, and communication. Some challenges may be mitigated by improving comprehensive and accessible information on available services, as well as holistic social support.

Trial registration number

CRD42019139183.

Keywords: Systematic review, Maternal health, Public Health, Qualitative study

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Postnatal care (PNC) can improve maternal and newborn health outcomes, but uptake is often limited and inequitable.

Routine PNC is often undervalued by women, their families, and healthcare providers.

Women’s access to PNC is mediated by multiple factors, including influence of family members or other community leaders, previous experiences, and views on quality and experience of care.

Families living in a country other than that of birth often have worse health outcomes and lower healthcare utilisation than their non-immigrant counterparts.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This is the first study to systematically explore and synthesise the views of immigrant families on their engagement specific to postnatal services at the global level which includes migration to and from middle-income countries.

This study emphasises the perspectives and needs of immigrant families when seeking and using PNC services in their new countries.

Many women faced challenges in navigating the health system, resulting in feelings of isolation.

The importance of language barriers, as well as cultural differences towards PNC, were highlighted.

Health systems can better address challenges with navigating an unfamiliar system, as well as with feelings of isolation, by providing more integrated information and support to patients and their families.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Immigrant families’ challenges with the health system could be mitigated by improved patient navigation and assistance with resources to support broader functional and social needs (eg, transportation, language, food, housing).

Areas where women have reported ‘better’ experiences in their new countries should be used as positive models for sharing across health systems and settings.

More research is needed on the needs of immigrant women and families during the postnatal period that may be impacting access to PNC and how health systems are able to respond to those needs, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries with large numbers of migrants.

Background

Maternal and newborn care during the postnatal period is critical for the health and well-being of women, children and families,1 2 but postnatal care (PNC) is often difficult for families to access, especially for vulnerable and marginalised groups. PNC is defined as the care provided from immediately after childbirth up to 6 weeks (42 days) after birth1 2 although is sometimes measured for a longer time period.3 4 PNC includes a package of healthcare services to promote the health of women and newborns through risk identification, preventive health measures, education and health promotion, and management or referral for complications. The WHO recommends that all women and newborns receive PNC in the first 24 hours after childbirth, regardless of where the birth occurs, and also recommends multiple postnatal check-ups by a trained provider in the first 6 weeks.1

Although PNC is defined as a package of interventions that includes education, support and referral, only recent guidance has truly expanded beyond clinical care.1 4 For example, while recent data show an increase in PNC coverage to over 80% among women and newborns, this only refers to receiving an early postnatal visit by a healthcare provider.5 A recent systematic review found barriers and facilitators to PNC utilisation were the perceived low value of PNC for healthy women and infants by families and healthcare providers, and concerns around access and quality of care.6 The review also found, commonly across studies, women’s desire for more emotional and psychosocial support during the postnatal period.6 These findings highlight multiple missed opportunities for PNC promotion and ensuring continuity of care among the general population of women and newborns, but do not go in depth on the specific or additional needs of vulnerable populations.

PNC is one of the most sensitive services to socioeconomic and geographic inequities, especially among immigrant women.7 It has been recognised that immigrant women have additional challenges in accessing and using health services, including for maternal and mental health needs, as well as poorer health outcomes.4 8 9 Immigrant women and families are particularly vulnerable to the lack of social support networks during the perinatal period.10 11 A review of immigrant women’s needs during pregnancy and childbirth found two overarching themes: women needed ‘caring relationships’ related to maternity care in their new countries, and women struggled to ‘cope, communicate, connect, and achieve a safe pregnancy and childbirth’.12 Another recent review of immigrant women’s experiences with maternity care in Europe highlighted the challenges around navigating new health systems, language barriers, and quality of care.13 Further, a multi-country survey from 11 countries also in Europe found that immigrant women reported more barriers in accessing facilities, less timely care, less comfortable care, and more negative experiences, including more separation from infants, fewer offers for pain relief, and more requests for informal payments, than non-immigrant women.14

The range of experiences for immigrants in the perinatal period will vary based on individual, familial, social and factors relating to their legal status, with some women having easier transitions in assimilating and others facing both predictable and unexpected challenges. Despite the range of experience, it is instructive to systematically review the reported experiences of this vulnerable group when engaging with PNC services.

For this analysis, our aim was to assess the views and experiences of immigrant women and their families who moved from one country to another in accessing routine PNC for themselves and their infants.

Methods

This is a subanalysis from a larger qualitative evidence synthesis (QES). The methods of the larger QES are described elsewhere.6 Briefly, the QES included qualitative or mixed-methods studies where the focus was the views of women, their partners, and families, on factors that influence uptake of routine PNC (ie, those without additional postnatal needs due to comorbidities or identified medical risk), irrespective of parity, mode of delivery, or place of delivery. Studies related to adolescents, or partners, families, and community views, were analysed separately.15 16 A framework approach was used to inductively develop initial themes17 and thematic synthesis18 and was then used iteratively based on the initial thematic framework. Study assessment included the use of a validated quality appraisal tool described herein.19 Confidence in the findings was assessed using the GRADE-CERQual tool.20 This review uses the subset of identified studies focused on the views and experiences of immigrant women and families seeking PNC.

Definitions

We define the postnatal period as the time between birth, including the immediate postpartum period (first 24 hours after birth), and up to 6 weeks (42 days) after birth.2 6 ‘Routine PNC’ was defined as formal service provision that is specifically designed to support, advise, inform, educate, identify those at risk and, where necessary, manage or refer women or newborns to ensure optimal transition from childbirth to motherhood and childhood. Specialist care was not included, although could be screened for in the context of routine care. Immigrant women were defined as women who are living in countries other than their country of birth, which included displaced persons such as refugees and asylum seekers as long as they were not living in camps or settlements.21 22 Definitions used in the overall review are included elsewhere.6

Reflexive statement

Our study team included clinicians, epidemiologists, public health researchers, librarians and programme managers, all with experience in the provision and study of maternal and neonatal health. In addition to findings from the larger QES, we began this subanalysis with background and experiential knowledge that PNC is very often unavailable or inadequate, and that immigrant women likely experience additional challenges with accessing and using formal PNC. Members of our study team have been involved in the direct provision of PNC, in the assistance of immigrant families in linking to healthcare services, and in developing national and international guidelines for PNC. Half of our study team currently reside in countries other than the one in which they were born, having moved voluntarily for increased professional opportunity, and few moved from significantly lower-income to higher-income countries.

Search strategy

The search strategy was based on the following concepts: barriers and limitations, PNC, and health services needs and demands, and covered papers published from inception through the end of December 2019. Databases searched included MEDLINE (OVID), PubMed, CINAHL (EBSCO), EMBASE (OVID) and EBM-Reviews (OVID), as well as a search for grey literature, with no language restrictions. Hand searching was also used to identify grey literature documents on the following websites: BASE (Bielefeld University Library), OpenGrey and on the WHO. Duplicates were excluded through the EndNote X9 software using a method developed by Bramer et al.23 The original search strategy is published elsewhere.6

Study selection

We uploaded all records identified in the search into Covidence software, excluded duplicates, and screened records based on title and abstract. For consistency, members of the study team (ES, NE, YK) independently screened the titles and abstracts against the a priori inclusion/exclusion criteria and excluded irrelevant records. Additional members of the study team (VB, DJ, MB) provided input during discussions of disagreements and papers were included via consensus.

During the title/abstract screening process, papers were categorised as either ‘general population’ or subpopulations such as ‘adolescents’ or ‘partners or families’ or ‘immigrants’. Papers labelled as ‘immigrants’ are included here. Papers addressing women living in refugee or internally displaced persons camps were excluded, as it was felt that care-seeking within a camp setting was conceptually different than navigating the routine care system. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the overall study and this specific analysis can be found in online supplemental table 1.

bmjgh-2023-014075supp001.pdf (161.2KB, pdf)

Data extraction and assessments of quality were conducted for each eligible paper by study team members, with disagreements settled by consensus after discussion.

Data extraction and analysis

For each included study, data extraction, analysis and quality appraisal proceeded concurrently, using the ‘best fit’ framework approach described by Carroll et al.17 We used a framework developed for our prior review on factors affecting PNC which included five themes (access and availability; physical and human resources; external influences; social norms; and experience of care). We recorded pertinent details from each study (eg, author, country, publication date, study design, setting and location of birth, setting and location of PNC, sample size, data collection methods, participant demographics, contexts, study objectives) in a predesigned spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel which was developed for the larger QES. Themes were then added to the Excel sheet and the author-identified findings from each study were extracted (along with supporting quotes). Any codes which did not fit under existing themes were placed in a section marked ‘other’ to allow for the emergence of new subthemes or concepts. We deliberately searched for data that ‘disconfirmed’ or contradicted themes found in the larger QES, and our prior beliefs.

Quality assessment

Included studies were appraised using an instrument developed by Walsh and Downe24 and modified by Downe et al.25 Studies were rated against 11 predefined criteria,20 and then allocated a score from A to D, representing combined rankings of components of the studies: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of results. Studies scoring C or higher were included in the analysis.

Studies were appraised by each reviewer independently and a 10% sample was cross-checked by a different study team member to ensure consistency. Studies where there were scoring discrepancies of more than a grade were referred to another study team member for moderation and further discussion.

Once review findings were agreed on by the study team, the level of confidence in each review finding was assessed using the GRADE-CERQual tool.20 GRADE-CERQual assesses the methodological limitations and relevance to the review of the studies contributing to a review finding, the coherence of the review finding, and the adequacy of data supporting a review finding. Based on these criteria, review findings were graded for confidence using a classification system ranging from ‘high’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘low’ to ‘very low’.

Results

Papers included in overall study and analytic sample

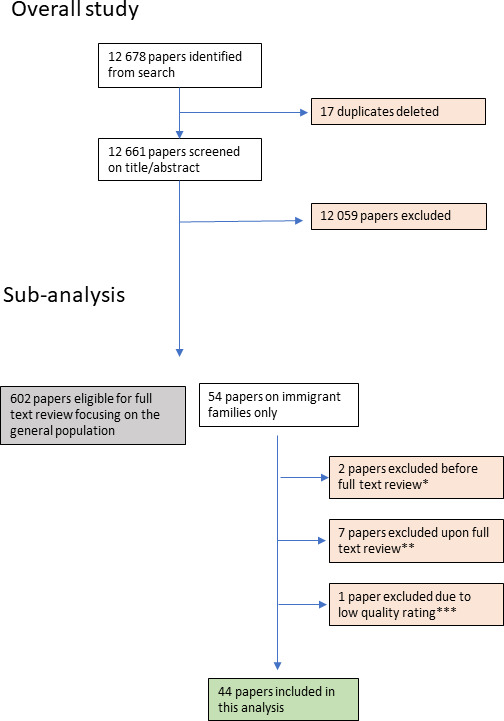

Our systematic searches yielded 12 678 records, of which 17 were duplicates. An additional 12 059 were excluded by title and by abstract, leaving 602 for full text review (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included papers. Reasons for exclusion were: *doctoral thesis, conference abstract. **Systematic review, only secondhand accounts, internal seasonal migration, focus on ethnic minorities who did not immigrate, mixed reports from immigrant and non-immigrant women, and with no reference to postnatal care. ***Low-quality.

A total of 54 articles were eligible based on title and abstract. Two were eliminated before full text review: one doctoral thesis and one conference abstract. Another seven were excluded on full text review: one systematic review, one paper that only included secondhand reports from women, one paper where women were only internal seasonal migrants; one paper on ethnic minorities within one country; one paper which mixed immigrant and non-immigrant women (unextractable data); and two papers focusing only on cultural practices in the home during the postnatal period but without reference to PNC. One additional paper was excluded on the basis of quality (D grading).

Our final list of articles for the analytic sample included 44 studies with views from immigrant women and their families on routine PNC. They represent a large number of countries in which women sought PNC, but almost all were high-income. We identified 13 papers about families who moved to Australia or New Zealand, 8 papers about families who moved to Canada, 7 papers about families who moved to the UK, 7 papers about families who moved to the USA, 7 papers about families who moved to Europe (Switzerland, Portugal, Finland, Sweden), 1 paper about women who moved to Thailand, and 1 paper about women who moved to South Korea. A full list of the included studies with relevant characteristics is shown in online supplemental table 2.

Findings

We identified 17 review findings. These findings were mapped against our a priori framework used for the primary analysis as well as those used for subsequent analyses1 2 to create our final analytical themes. Based on this exercise, we kept the theme on resources and access and merged two themes—behaviours and attitudes and external influences—to become differences from home country. What women want and need was split into experiences of care and support needs.

Themes identified from included studies

Resources and access

Issues relating to language and availability of trusted interpreters among immigrant women and their families in accessing PNC were highlighted by most. Some women reported not understanding their providers but feeling unable to voice their confusion. Regarding translation services, some women reported not receiving enough support while others were disappointed by the constant change of interpreters and the lack of rapport with them. Oftentimes, providers relied on partners or other family members to translate, even if they themselves had limited knowledge of the local language. The presence of interpreters during consultations felt invasive for some women and others were unable to differentiate the roles of interpreters from their providers. Availability of translation and interpretation services were not always clear. Even where women knew of available services, they expressed reluctance to request these services due to concerns of being othered by their providers.

Beyond interpretation, the services being offered to immigrant women were not always perceived as adequate, from long waiting times to get appointments or referrals to feeling rushed during appointments. Women’s needs were not always addressed as expected. Understanding how the health system worked in their new home country was challenging for many women and their families. Some only became aware of services they could use after the fact or after having experienced lengthy and costly trajectories to obtain the care they needed for themselves and their newborns. Costs associated with PNC, from transportation to medicines to newborn needs, precluded women from being able to care for themselves and their infants. Relatedly, many immigrant women and their families lived in legally or financially precarious situations in their new countries, further hindering their access to care or ability to properly care for themselves and their newborns.

Furthermore, immigrant families oftentimes were fearful of their legal status and made access to PNC challenging. This was compounded by the difficulty in understanding the system and the knowledge of services available to immigrants which were independent of their legal status. For others, obtaining the documentation necessary to access PNC acted as a barrier.

See table 1 for a detailed description of this theme with associated quotes and CERQual grading.

Table 1.

Review findings and CERQual grading for theme 1 ‘resources and access’

| Review finding | Contributing papers | Supporting quote | CERQual grade* |

|

Language issues, including need for interpretation Language was identified by most women in most studies as a big barrier in accessing services. Even when interpretation was available, it was not always easy to find interpreters with time availability and women mentioned difficulties in building rapport with interpreters. At times, their partners, friends or family members acted as interpreters, meaning oftentimes they were the de facto decision-makers, and even if they too were not fluent, which could result in unwanted interventions. At others, providers attempted to communicate using simple language. Some women highlighted the benefit of having the same interpreter work with them during different encounters. Even among women who were fluent in the language of their new host country, they felt their understanding was limited when it came to ‘medical’ terms and that providers had difficulties understanding them. Other women relied on finding providers who spoke their language to adequately communicate with them |

21 studies: Akhavan and Edge,41 Alshawish et al,42 Chu,43 Crowther and Lau,44 Davies and Bath,45 Gurman and Becker,46 Higginbottom et al,47 Higginbottom et al,48 Hoang et al,11 Hoban and Liamputtong,49 Kim et al,28 Lam et al,50 McLeish,51 Origlia Ikhilor et al,52 Phillimore,53 Riggs et al,54 Riggs et al,55 Renzaho and Oldroyd,56 Sami et al,57 Wikberg et al,58 Yelland et al59 |

‘When he was born, I got a pocket book and they told me to do something. But I couldn’t understand because it was in Korean’. (Kim et al28 immigrants from several African countries in South Korea) ‘… the nurse came to my house to visit me and she talk about lots of things but I didn’t understand … so whatever she asked me, I said, yeah, yeah, yeah. I just wanted to say, oh, you just leave’. (Higginbottom et al48 immigrants from several countries in Canada) |

High |

|

Inadequacy of services Women stated that it was at times hard finding a physician because they were either not taking new clients or physicians were so busy, appointments or referrals were given with lengthy delays. In addition to difficulties in obtaining appointments, women in one study highlighted differences between services depending on location. Others mentioned too brief encounters or feeling rushed with their physicians. Women from one study mentioned inadequacy relating to culturally competent (or culturally safe) care |

6 studies: Almeida et al,60 Alshawish et al,42 Grewal et al,61 Higginbottom et al,48 Riggs et al,54 Shafiei et al62 |

‘It’s hard to find a family doctor because I phoned everyone … it took me for a while, and then you can’t go with him because his appointment [book] was full. I phoned a lot of clinics and then they cannot accommodate’. (Higginbottom et al48 immigrants from several countries in Canada) ‘But here, a specialist appointment may take a year, and in the Ukraine … it could occur tomorrow!’ (Almeida et al60 immigrants from several countries in Portugal) |

Moderate |

|

Uncertainty around services available due to legal status Women, mainly from studies with a heterogeneous population of individuals with diverse legal statuses, went to great lengths to avoid immigration officers, hindering their access to services. Other women expressed frustration at differences in services according to legal status; other referred the process of legalisation as a barrier in access to healthcare. Women described confusion as to what services were available to them and in one case, a woman did not know that services would be free |

4 studies: Almeida et al,60 Kim et al,28 Phillimore,53 Sami et al57 |

‘I think the main barrier was not having the healthcare users’ card’. (Almeida et al60 immigrants from several countries in Portugal) | Moderate |

|

Limited personal resources/cost of services Some women, mainly from studies with a heterogeneous population of women with diverse legal statuses, including asylum seekers and refugees, described not having the essentials to care for themselves and their babies and needing to rely on charity or voluntary organisations for support. Other women reported difficulties in accessing housing services or needing to share housing with others, challenging providing care for their newborns. Women also mentioned cost of services as a barrier to accessing them. Women from one study stated they had to skip meals to save for transportation costs. Other women mentioned difficulties with having the appropriate equipment for bottle sterilisation |

7 studies: Higginbottom et al,48 Hoban and Liamputtong,49 Kim et al,28 McLeish,51 Phillimore,53 Qureshi and Pacquiao,63 Riggs et al55 |

‘The midwives were nice except one, who I asked to leave the room. She was asking why don’t I have the special equipment to clean the bottles? I don't have money to buy special equipment. I have four bottles and I boil them, so that’s the only way I can sterilise them. She didn’t like it’. (McLeish51 immigrants from several countries in the UK) ‘If there was rain, water leak into the house. Especially in winter, rain made the house much colder. It was hard to sleep and eat, and the stress made hypertension. The cost of baby’s diaper was very expensive and I put my sanitary pad to my baby instead of diaper. The formula milk was too expensive so I gave soybean milk to my baby after I could not produce breast milk’. (p140) (Kim et al28 immigrants from several African countries in South Korea) |

High |

|

Difficulty navigating healthcare system Women from several studies described difficulties navigating the healthcare system, including how to reach their appointments due to transportation issues (cost, distance and time). Women also mentioned confusion around what is included within maternal and child health services or what services should be accessed where and specificities of the country’s healthcare service organisation. It also included difficulties after discharge from the hospital and the services needed and available to them. They often found out about services by word of mouth from other immigrants |

15 studies: Almeida et al,60 Alshawish et al,42 Chu,43 Higginbottom et al,48 Hill et al,64 Kim et al,28 Lee et al,65 Origlia Ikhilor et al,52 Phillimore,53 Quereshi and Pacquiao,63 Reitmanova and Gustafson,66 Renzaho and Oldroyd,56 Riggs et al,54 Sami et al,57 Wikberg et al58 |

‘And you write it somewhere on the paper if you forgot, its hard sometimes to remember where and when is your appointment … they should call you to remind you [if] they miss the appointment because they can’t, they forget to write [the appointment information] in the [child health record] book and they [the mother] forget to call back to make another appointment’ (Riggs et al54 immigrants from several countries in Australia) ‘I could not go to any nearby hospital I needed, instead I had to take subway with my young daughter. It takes very many hours to go and come back’. (Kim et al28 immigrants from several African countries in South Korea) |

High |

*High, moderate, low or very low.

Differences from home country

Specific to immigrant women is the constant comparison between how things were back home and how they are in their new host countries. The reasons for migrating across country borders were varied, ranging from leaving war-torn or conflict-affected regions to the pursuit of better opportunities. Adaptation to their new country setting presented as a challenge for most immigrant women and their families. This included cultural differences with regards to PNC and what was deemed acceptable to the women and to the providers in their new country. Abiding by certain cultural practices common in their home countries while receiving care in the new country was challenging for a variety of reasons, including lack of access to certain foods or elements that women felt appropriate for themselves and their newborns. How and what to feed newborns came across in reports from many immigrant women and their families. This included certain practices to promote/support breast feeding. Similarly, for women trying to follow the practice of postpartum seclusion (‘cuarentena’ or ‘doing/sitting the month’), whereby certain items and activities are to be avoided or practiced in the days and weeks following childbirth, the practice was hard to implement in their new settings.

For a few women, the gender of the healthcare provider during PNC was so important that they were willing to forgo services. In some instances, the health facilities were able to accommodate and respect women’s wishes in line with what they would have been offered in their home country, but often their requests went unheard or were ridiculed.

Although some women referenced how things were different and better in their home country as compared with their new host country, many women focused on the better care they received after immigrating. Many women leaving settings with fragile or overburdened health systems felt grateful to receive the quality care they had access to in their new country. Others focused on availability of free services which they would not have had access to back home. Nonetheless, there were some women who mentioned preferring access to certain tests or services offered back home.

See table 2 for a detailed description of this theme with associated quotes and CERQual grading.

Table 2.

Review findings and CERQual grading for theme 2 ‘differences from home country’

| Review finding | Contributing papers | Supporting quote | CERQual grade* |

|

Cultural differences in postnatal care Some women identified differences in provision of care and culturally acceptable (or perceived unacceptable) care provided in their new country. They mentioned feeling unable to abide by their culture relating to maternal/newborn care. Some women mentioned that they felt that specific interventions or practices from their new country were being imposed on them, or similarly, that things that were commonly practiced in their home country were not acceptable in their new home. There were also differences in how-and what- women communicate with their healthcare provider. Some women highlighted the importance of religion in their postnatal care |

22 studies: Almeida et al,60 Chu,43 Davis,10 67 DeSouza 2005, Doering et al,68 Grewal et al,61 Gurman and Becker,46 Higginbottom et al,69 Higginbottom et al,48 Kim et al,28 Lam et al,50 Lee et al,65 Phanwichatkul et al,70 Qureshi and Pacquiao,63 Reitmanova and Gustafson,66 Renzaho and Oldroyd,56 Rice,71 Riggs et al,55 Shafiei et al,62 Ta park et al,72 Waugh,73 Wikberg et al58 |

‘In this country there is no fireplace for you to sleep next to but you have already spend a lot of time in the hospital so you just come home. In this country, you would stay for three or four days there and so you already have strength and when you come home then you just go straight into bed’. (Rice71 immigrants from Laos in Australia) ‘But they make me [take a shower] in the hospital. I have to. The nurse came in and told me. And she would not bring the baby for me. If I don’t take a bath, they won’t give me the baby to feed … So I did, I went in to take a quick shower and then came out. It makes me feel like it’s sort of a parent’s order. They say protect the baby from germs [and] all that. I understand, but I have my own beliefs, so when I get home, I do different way. I just do what I [am] supposed to do’. (Davis10 immigrants from South East Asia in the USA) |

Moderate |

|

Postpartum seclusion (‘Doing the month’/cuarentena) Many women, from Asia and Latin America, mentioned the practice of ‘doing the month’ or ‘cuarentena’ which would have been central to their postnatal care back home, and difficulties with implementing it in their new environment, whether because they now felt it restricting or because they had a hard time getting others to respect it |

6 studies: Chang 2018, Davis,10 Grewal et al,61 Lam et al,50 Rice,71 Waugh73 |

‘Because we are not in China we will not “zuo yue zi” [at] one hundred percentage according to the “zuo yue zi” methods in China. It’s fine as long as I feel okay about it in my heart’ (Chang 2017, immigrants from China and Taiwan in Canada) ‘Covering up—that’s for the entire 40 days. It’s partly for the baby and partly for yourself. You cover your ears, or put cotton in your ears so that the drafts can’t get in because of the headaches and so that you don’t get the aches and pains in your bones and all that. Also the feet—without socks, on the cold floor—it gives you aches and pains like reumos, achy bones/ joints, and you get varicose veins. It’s called like phlebitis. That’s el frio, or el aire’. (Waugh73 immigrants from Mexico in the USA) |

Moderate |

|

Gender of healthcare provider For many, mainly from studies with a heterogeneous population of women with diverse legal statuses, including asylum seekers and refugees, the gender of health professionals and interpreters was critical to how women engaged with care, including their comfort in disclosing health or family concerns. This was presented by most women as a difference with how services would be offered in their home country and a barrier to accessing care |

7 studies: Higginbottom et al,47 Hill et al,64 Reitmanova and Gustafson,66 Shafiei et al,62 Shafiei et al,74 Wikberg et al,58 Yelland et al59 |

‘After birth because I had a tear they told that a male doctor should come for stitches … my husband gave permission but I am still unhappy about the male doctor who came for stitches. For stitches should be a female doctor; most women would ask for a female doctor’ (Shafiei et al62 immigrants from Afghanistan in Australia) ‘The doctor was good, first I was a bit (shy) … because it was a man’. (p644) (Wikberg et al58 immigrants from several countries in Finland) |

Low |

|

Newborn feeding practices Women mentioned differences in perception of newborn feeding as compared with their home countries. Some mentioned other feeding practices that were common to them, especially immediately after birth, whereas others focused on the importance of breast feeding. Some women mentioned different understandings of what facilitates or interferes with breast feeding Other women also mentioned the need for support from healthcare workers and the community relating to breast feeding |

5 studies: Higginbottom et al,69 McFadden 201375, Phanwichatkul et al,70 Qureshi and Pacquiao,63 Waugh73 |

‘I had special instructions. I had decided that I wanted my nand (sister-in-law) to give my first child the ghutti. My mother especially bought some ghutti and went to her house to get her to dip her finger in the ghutti. Then when the baby was born my mother fed her the ghutti so in effect it was both my nand’s and my mother’s ghutti’. (Qureshi and Pacquiao63 immigrants from Pakistan in the USA) ‘I want to ask this thing that at that time there is no milk, during the first few days, 2, 3 days after the birth there is no milk so why do they keep on telling me to get them to suck and feed’. (McFadden 2012, immigrants from Bangladesh in the UK) |

Low |

|

Perceived better care at home country/new country Women from a few studies mentioned that care offered in their ‘new’ country was better than in their home country, including access to more and better facilities and services, better care, and lower costs. In some instances, women were pleased with receiving the same quality care as locals. However, some women preferred services from back home. Some of these differences related to services available, as well as interventions and tests and different recommendations. Some women stated that having an appointed family doctor was recognised as a facilitator. Some women mentioned differences that they perceived as better care in their home countries |

12 studies: Almeida et al,60 Alshawish et al,42 Crowther and Lau,44 Grewal et al,61 Gurman and Becker,46 Higginbottom et al,48 Kim et al,28 Lee et al,65 Sami et al,57 Shafiei et al,62 Wikberg et al,58 Wikberg et al76 |

‘Here is better; in Afghanistan there isn’t any doctor, anything [facility]; in the area that we used to live, there is no doctor; here there are a lot [of doctors] … when there’s a problem, the nurse would come soon … a doctor is available if there is a problem’ (Shafiei et al62 immigrants from Afghanistan in Australia) ‘But when the baby is born care is much better [in the UK] than in Poland’ (Crowther and Lau44 immigrants from Scotland in the UK) |

Moderate |

*High, moderate, low, or very low.

Support needs

Immigrant women from the identified studies expressed feelings of isolation and social support needs. Given the fact that most women were far from extended families and other support networks, they turned to mothers’ groups or church for social support with some seeking the needed support from home visits by healthcare providers. Some women highlighted the difficulties of not having their extended families or friends around to support them with their postnatal needs, and some women turned to paid help to aid them in the process. Relatedly, many women relied on their partners or their baby’s father for social support sometimes favouring more involvement in caring for the newborn infant, which would not have been considered an option in their home country.

Mental health support needs for immigrant women during the PNC period included help with transition from their home country to this new country, such as dealing with the shocks experienced during this process. However, the availability of mental health screening during the postnatal period was new to many; some welcomed this opportunity to speak with their providers about their feelings and how they were coping during the postnatal period. Others felt this was invasive or uncomfortable as they did not feel this type of care was relevant or appropriate for them.

Many women emphasised the lack of information, or an overwhelming amount of contradicting information found on social media and the internet, as an important barrier to accessing care. This resulted in some women mentioning not being aware of services available to them.

See table 3 for a detailed description of this theme with associated quotes and CERQual grading.

Table 3.

Review findings and CERQual grading for theme 3 ‘support needs’

| Review finding | Contributing papers | Supporting quote | CERQual grade* |

|

Social support/isolation Several women mentioned feelings of isolation given their separation from extended families. Many women mentioned feeling lonely or homesick, and sometimes even depressed with no relatives nearby. Women contrasted with how things would have been back home with the support and help of broader networks, including family. In some cases, women turned to people who came from their same countries/regions, church or other communities, or work, or even hiring people to help them through the different stages of care. Women from one study mentioned they would want more support in caring for their newborn from their husbands as was customary in their new country home. Some women sought their social support from healthcare providers, especially during home visits. Others mentioned multicultural mothers’ groups in the postnatal period as sources of social support which provided them an opportunity to connect with others |

20 studies: Chu,43 Davis,10 DeSouza 200567, Grewal et al,61 Higginbottom et al,48 Hoang et al,11 Hoban and Liamputtong,49 Kim et al,28 Lam et al,50 Lee et al,65 McLeish,51 Phillimore,53 Phanwichatkul et al,70 Qureshi and Pacquiao,63 Renzaho and Oldroyd,56 Riggs et al,54 Sami et al,57 Shafiei et al,74 Stewart et al,77 Wikberg et al76 |

‘I gave birth on Thursday morning and my husband went back to work the following Monday. So I stayed at home alone with my newborn baby. I did all the housework although I felt sick and I was not well enough, but I still had to do everything in the house. I could not look after myself at all’. (Hoban and Liamputtong49 immigrants from Cambodia in Australia) ‘My employer took me to the hospital. She helped me carry the baby. She knew the health providers and could manage the document jobs better. When I went back home, she took me in her car’ (Phanwichatkul et al70 immigrants from Myanmar in Thailand) ‘They should offer some support for the first couple of days at home, or even follow up by simply calling on the phone’ (Stewart et al77 immigrants from two African countries in Canada) |

High |

|

Mental health support Women had differences in perception on mental and emotional health support. Some women did not feel comfortable speaking about these issues with providers, while others welcomed the support provided by healthcare workers, with some identifying this as a new concept which they felt was important. Others would have liked more mental health support but felt providers were not willing or able to provide it. Many of the women had complex emotional and mental health needs, including fear about being refused asylum and deported back to the countries and trauma experienced during their migration process |

13 studies: Chu,43 Higginbottom et al,47 Lam et al,50 McLeish,51 Riggs et al,54 Shafiei et al,62 Shafiei et al,74 Skoog et al,78 Stewart et al,77 Taniguchi et al,79 Ta Park et al,72 Willey 2020,80 Yelland et al59 |

‘The midwives and nurses were the best emotional supports for me during the entire time because I was going through the toughest phase of my life. The maternal and child health nurse calls me at home to check that everything is OK … she has not only been a verbal support for me but has linked me with support services’. (Yelland et al59 immigrants from Afghanistan in Australia) ‘I used to talk to my maternal and child health [nurse] … she’s so kind and very nice indeed, she always told me if you feel down sometimes, if you want to talk, I’m a good listener. I talked to her … at least I feel better, you know, when I was talking to her I felt better at that time’. (Shafiei et al74 immigrants from Afghanistan in Australia) ‘Oh, I was actually very happy that someone cared. It’s the first time that someone outside, a stranger, has asked me these questions. It was actually great and special. I’ve never experienced in a new country that a stranger with another language, there are many differences, but despite that when I was asked those questions, I was actually very happy’. (Skoog et al78 immigrants from several countries in Sweden) |

High |

|

Information needs Need for information was highlighted by several participants including lack of information on how services worked; others felt overwhelmed by the amount of information and felt confused as to what to focus on. This also included information sharing using social media and platforms as well as accompaniment with mental and emotional support on arrival to the new country. Women from one study focused on the importance of the information, especially for those unfamiliar with the language, culture and customs of the host country |

7 studies: Akhavan and Edge,41 Hoang et al,11 Lam et al,50 Phillimore,53 Renzaho and Oldroyd,56 Riggs et al,54 Stewart et al77 |

‘I got no information about support available’ (Phillimore53 immigrants from several countries in the UK) ‘For example, how should I do things while I was in pain. She gave me medical information’ (Akhavan and Edge41 immigrants from several countries in Sweden) |

High |

*High, moderate, low, or very low.

Experiences of care

Having the same provider accompany the women throughout their pregnancy to the postnatal period was highlighted as an important aspect to accessing care by many women across studies. For some women, being able to build rapport with a provider in a new country was very important, in particular because of cultural or language differences, so continuity was deemed even more relevant.

Linked to the above, women focused on positive experiences in their interaction with healthcare providers who were comprehensive in their care for them and their infants, being kind and sympathetic. Others stated feeling providers did not offer sufficient time or enough detail on the care they needed or reported needing to wait long times during hospital stays for providers to respond to their needs. Further, some women mentioned specific difficulties in being able to express how they were feeling or if they were in pain or when providers interpreted these needs differently, sometimes linked to providers’ preconceptions on women of other nationalities or their prejudice against immigrants. Immigrant women mentioned episodes of stigma and discrimination based on their cultural background, nationality, or race. Many women perceived that providers cared for them differently because of their immigrant status or were dismissive of their requests for care and attention. Several women mentioned experiences of overt discrimination whereby they were talked down to, or providers referred to them in derogatory terms.

See table 4 for a detailed description of this theme with associated quotes and CERQual grading.

Table 4.

Review findings and CERQual grading for theme 4 ‘experiences of care’

| Review finding | Contributing papers | Supporting quote | CERQual grade* |

|

Continuity of care Some participants discussed the lack of continuity of maternity care provider through their pregnancy and at the birth as a challenge in their postnatal care. This was especially important to women with pre-existing conditions or concerns, as well as to women who were new to the country and expressed the importance of creating rapport with the provider |

5 studies: Crowther and Lau,44 Hill et al,64 Lee et al,65 Riggs et al,54 Sami et al57 |

‘The only problem is that he (her gynaecologist) works only at a private clinic, not at the public hospital, so I already said goodbye to him about 2 weeks ago’. (Sami et al57 immigrants from several countries in Switzerland) | Moderate |

|

Ability to express pain or feelings Some women, mainly from studies with a heterogeneous population of women with different legal statuses, as well as asylum seekers or refugees stated that they were unable to freely communicate how they were feeling and/or if they were in pain. Others mentioned that their own expressions of pain or feelings were interpreted differently by healthcare providers, resulting in lack or delay in services |

6 studies: Doering et al,68 Higginbottom et al,69 Kim et al,28 Skoog et al,78 Stewart et al,77 Wikberg et al58 |

‘I said I couldn't sleep and was suffering, but the specialist did not recognise that I was having a hard time … The midwife had probably not realised that, either. I might not have told them the entire truth … The midwife told me that she saw me having the maternity glow … I was thinking it was really different from how I was feeling. It seemed my pain wasn’t obvious on the outside. I knew that they didn’t see that. I just said, ‘Really? I am really painful. I am not like that’. [in a small voice]. That’s all I said … I should have told them about my pain more, but I didn’t’. (Doering et al68 Japanese immigrants in New Zealand) ‘I didn’t even have painkillers because the baby already came, because they hadn’t really believed me because I wasn’t crying or speaking for myself’. (Stewart et al77 Sudanese woman in Canada) |

Moderate |

|

Quality of the interaction with healthcare providers While some women, mainly from studies with a heterogeneous population of women with different legal statuses, asylum seekers or refugees, focused on the positive experiences they had with the information provided, and the postnatal check-ups of both baby and mother, others focused on negative interactions with healthcare providers, including doulas, leaving women unhappy and feeling caregivers spent little time explaining things, and showed a lack of compassion |

7 studies: Akhavan and Edge,41 Higginbottom et al,47 Higginbottom et al,48 Hoban and Liamputtong,49 Riggs et al,55 Shafiei et al,62 Yelland et al59 |

‘They helped me a lot; checked the baby and myself … they came every hour and examined, checked me up, asked me lots of questions; for example, ‘what problem do you have?’ and I was very satisfied with these things (Sanaz, multipara)’. (Shafiei et al62 immigrants from Afghanistan in Australia) ‘After the birth in hospital, specifically I’d ring the buzzer maybe because I had pain, I couldn’t get up to change her or I really needed somebody just to give her to me; that it would take them for a long time to attend … so I found that not attending very disappointing (multipara)’ (Shafiei et al62 immigrants from Afghanistan in Australia) |

High |

|

Stigma and discrimination Some women, mainly from studies with a heterogeneous population of women with different legal statuses, asylum seekers or refugees, described feeling discriminated, especially if they were living in vulnerable situations, such as difficult social or financial conditions, or if they were living without a legal status. Further, many women identified feeling discriminated against by healthcare providers, including perceived racism by providers |

8 studies: Chu,43 Davies and Bath,45 Gurman and Becker,46 Higginbottom et al,48 McLeish,51 Origlia Ikhilor et al,52 Sami et al,57 Shafiei et al74 |

‘No, I think they do that because we are not married. In my case, I felt it happened because I was alone, because they suggested it several times … I think it’s because of a financial matter’. (Sami et al57 migrants from several countries in Switzerland) ‘The problem was that we were informed that the unborn child was sick. And in the end, it was born healthy. We did not understand why [the doctor told us the child was sick), we then thought, maybe it was because we have a different skin colour—that’s what we think’. (Eritrean woman) (Origlia Ikhilor, immigrants from several countries in Switzerland) ‘In the end I got an infection in my scar … I went to the midwife and said I’m feeling cold, and all my body shakes … She looked at me like this and said, ‘You are OK’ … She said to another midwife, ‘These Africans … they come here, they eat nice food, sleep in a nice bed, so now she doesn’t want to move from, here!’ … When she said this, I didn’t say anything I just cried—she doesn’t know me, who I am in my country. And the other midwife said, ‘What’s wrong with them, these Africans?’ and some of them they laughed’. (McLeish51 immigrants from several countries in the UK) |

Moderate |

*High, moderate, low or very low.

Discussion

Factors that influence women’s utilisation of routine PNC are interlinked, and include access, quality, and social and cultural norms. Studies on immigrant women and their families identified themes relating to resources and access, differences from home country, support needs, and experiences of care.

Seventeen review findings were identified, with high confidence study findings including challenges around language and communication; uncertainty about navigating the system including transportation and legal entitlements; high mental health, emotional and informational needs; the impact of personal resources and social support; and the quality of interaction with healthcare providers. The review findings on immigrant women’s needs for PNC utilisation largely conform with previous studies around what women in the general population want during this time period, as well as challenges related to care access and experience of care,6 while highlighting specific challenges for this vulnerable population. Findings from this review highlight the importance of care experiences beyond clinical care and even beyond healthcare which aligns with what others have found among migrant women in Europe.13

One of the high confidence findings focused on language barriers and the need for interpretation, and a lower confidence finding focused on the related issues of not being able to express nuance of feelings and emotions in a new language or via a translator. While these experiences are not necessarily unique to immigrants, this was commonly discussed in included studies in this review as well as what others have found for maternity care among immigrant women, suggesting the universality of experience among immigrant families.13 While there are obvious differences between those migrating voluntarily versus not, and those with ability to learn a new language or have access to translators and interpreters, the also-noted feelings of isolation and unfamiliarity are likely exacerbated by language barriers for many immigrants. Because individual healthcare providers cannot be expected to speak multiple languages in every setting, translation and interpretation services within healthcare teams are critical in providing accessible and welcoming care. Further to language services, the ability for providers and interpreters to offer culturally safe care is an important related aspect.26

Another important finding was about the difficulty of navigating the healthcare system, including access and transportation. Again, this is not unique to immigrants,6 but this experience may be more likely or exacerbated for families who are new to a country. Women reported not knowing what services they were entitled to or what would be included or covered under various healthcare schemes, especially services that might be available after discharge from a health facility. This is a missed opportunity to provide information and linkages to other services. The lack of integrated social services to support immigrants’ various needs inhibits their navigation of and access to social support.15 One such strategy could include the use of health navigators to support immigrants’ access and navigation of new health systems.27 A specific aspect of care navigation for some immigrants was uncertainty or fear related to their legal residency status. Women who were undocumented often expressed concerns about being identified and had more anxiety; others mentioned underutilisation of services to avoid detection. In most cases, women described these as reasons not to seek care; however, other studies have identified cases where women were turned away.28 As these statuses can change over time, so too can the agency providing services or insurance and knowing where to get information that is timely and accurate is critical. Even families moving voluntarily may find challenges in understanding and accessing a new system and may take time to establish new networks.

Similar to our findings on general PNC needs, women expressed a desire for more information, social support, and mental health support.6 Insufficient mental and social health support is a limitation of many health systems throughout the world.29 However, immigrants who move without extended family, with limited resources, and with linguistic barriers, or not by choice, may feel the isolation more acutely, when compounded with homesickness or depression.13 28 30 Some respondents discussed finding social support through extrafamilial religious organisations or community groups with members from the same home countries, but often described this as necessary but less preferred to the support of previous communities or extended family. Although women generally perceived their family involvement to be supportive, it has been found in other studies that influence from other family members can be both protective and prohibitive to successful engagement with PNC.28 31 Others have noted the challenges with providing good follow-up care after discharge, such as challenges in identifying and reaching isolated immigrant families.32

While women and families had differences in their attitudes toward sharing emotional struggles with healthcare providers, most wanted some kind of mental health support. Displaced persons, including asylum seekers and refugees, often have specific traumas and fears that may require specialty treatment.33 34 Studies have quantitatively found high levels of depression and experiences of abuse among refugees as well as reports of skipping food among all immigrant families which affects emotional and physical health, as well as the ability to breast feed and recover from childbirth.32 Multi-disciplinary care teams, integration with non-clinical social services and coordination among health teams, guarantees of anonymity, and trauma-informed care, may have important roles to play in addressing this mental healthcare gap.27

As many women and families in included studies had experiences with maternity services in both their previous and new countries, many comparisons emerged, even though it was rarely the objective of the study. Women noted cultural differences in care and patient–provider communication norms; these differences were sometimes positive and sometimes negative. A related, but lower-confidence finding was that many women perceived the quality of care to be better in their new country (which has been found in other studies as well35), although there were also mixed reports. Relatedly, some women reported better experiences back home even when these did not respond to evidence-based or best practices (eg, increased testing), possibly linked with a better financial situation in their home country, and which may be a reflection of a need for familiarity and normalcy.

Some women described feeling stigmatised or discriminated against, either in the health facility, or after being discharged. While experiences of stigma and discrimination are not unique to immigrants6 16 women of ethnic and cultural groups different from the dominant ones in their new countries often attributed their experiences to racism, xenophobia, and classism. Although many respondents discussed the high quality of interaction with healthcare providers, some described negative experiences, and some felt more generally dismissed or insulted by the healthcare system itself. This comports with a growing body of research illustrating the impact of quality, and perception of quality, on choices of if, where, and when to seek care in addition to evidence of racism and discrimination against migrants in general.36 37

Many of the findings related to experience of care derived from women originally from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) who have immigrated to high-income countries (HICs), highlighting important disparities in access and use of services, even in countries with theoretically more robust health systems. Across studies, immigrant women and families reported barriers to PNC access such as payment barriers, lack of information about services, linguistic barriers, concerns around discrimination or legal challenges, and low satisfaction with services. These findings are similar to more general reviews of barriers to healthcare access among immigrants in HICs.13 38 39 More research is needed on the experiences of women and families who migrate between low-income or middle-income countries; this population is overlooked and the burden to the health systems in these countries is often not recognised.40

Limitations of this review include both the limitations of the included papers themselves, and the focus of those papers; biases in the countries selected for research (in this case, largely high-income country health systems) are reflected. Despite targeted efforts, we did not identify any papers describing PNC from immigrants to low-income countries and only one to an upper middle-income country, though we know that a large proportion of migration occurs among LMICs, for example, within LMICs in Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East. This phenomenon and its effect on already under-resourced health systems is understudied. Almost all papers were migrants from LMICs to HICs. Further, for many of the included papers which covered both intrapartum and postpartum periods, it was difficult to extract themes only related to PNC, although we sought to differentiate in our extraction form and identification of themes. As has been noted elsewhere, more research is needed in ‘distinguishing the needs during the immediate (eg, pre-discharge from a health facility) and later postpartum periods’.6 Despite our broad search terms, country-specific terminology may not have been captured. We acknowledge new studies may have been published since the end of the search. Nonetheless, this review uses a rigorous methodology and comprehensive search, selected papers from a very large database, and provides a focused, contemporaneous analysis on a group with specific PNC needs, giving us confidence in our findings.

Conclusions

Immigrant families experience many of the same challenges in getting PNC as non-immigrant families but have additional needs around language, navigating the health system, as well as specific social support. Some challenges may be mitigated by improving coordination of services together with individual support in navigating the system together with integrated and holistic support addressing basic and social needs. Achieving improved coverage and quality of PNC will only occur when vulnerable populations are welcomed and treated equitably.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research at the WHO, as well as those who provided feedback at various stages of the analysis and writing process: Soo Downe from the University of Central Lancashire, UK and Caroline Sauvé from the Centre hospitalier de l'Universite de Montreal, Canada.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seema Biswas

Twitter: @ersacks, @EtienneVincentL

ES and VB contributed equally.

Contributors: ES and EVL conceptualised the original review and secured funding with the assistance of MB. ES, EVL, MB, VB, DJ and DZ designed the original search strategy. ES, VB, DJ, YK, NE and MB carried out the data screening, extraction and preliminary analysis. KF, NC and SMP contributed to the revised analysis. All authors reviewed data and participated in drafting and/or revising the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version for submission. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) or the WHO. ES and VB as equal guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, and the United States Agency for International Development.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e140–50. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postnatal care. London: Nice; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Protect the promise: 2022 progress report on the every woman every child global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030). Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacks E, Finlayson K, Brizuela V, et al. Factors that influence uptake of routine postnatal care: findings on women’s perspectives from a qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS ONE 2022;17:e0270264. 10.1371/journal.pone.0270264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langlois ÉV, Miszkurka M, Zunzunegui MV, et al. Inequities in postnatal care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:259–270G. 10.2471/BLT.14.140996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pregnancy and complex social factors: a model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. London: National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis RE. The postpartum experience for southeast Asian women in the United States. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2001;26:208–13. 10.1097/00005721-200107000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoang HT, Le Q, Kilpatrick S. Having a baby in the new land: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of Asian migrants in rural Tasmania, Australia. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balaam M-C, Akerjordet K, Lyberg A, et al. A qualitative review of migrant women’s perceptions of their needs and experiences related to pregnancy and childbirth. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:1919–30. 10.1111/jan.12139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fair F, Raben L, Watson H, et al. Migrant women’s experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in European countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2020;15:e0228378. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa R, Rodrigues C, Dias H, et al. Quality of maternal and newborn care around the time of childbirth for migrant versus nonmigrant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of the IMAgiNE EURO study in 11 countries of the WHO European region. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2022;159 Suppl 1:39–53. 10.1002/ijgo.14472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finlayson K, Sacks E, Brizuela V, et al. Factors that influence the uptake of postnatal care from the perspective of fathers, partners and other family members: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Glob Health 2023;8:e011086. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Javadi D, Sacks E, Brizuela V, et al. Factors that influence the uptake of postnatal care among adolescent girls: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Glob Health 2023;8:e011560. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, et al. “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:37. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewin S, Bohren M, Rashidian A, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a summary of qualitative findings table. Implementation Sci 2018;13:13. 10.1186/s13012-017-0689-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balaam M-C, Haith-Cooper M, Pařízková A, et al. A concept analysis of the term migrant women in the context of pregnancy. Int J Nurs Pract 2017;23:e12600. 10.1111/ijn.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McAuliffe M, Triandafyllidou A, eds. World migration report 2022. Geneva: Switzerland: International Organization for Migration; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, et al. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 2016;104:240–3. 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh D, Downe S. Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery 2006;22:108–19. 10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downe S, Simpson L, Trafford K. Expert intrapartum maternity care: a meta-synthesis. J Adv Nurs 2007;57:127–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:174. 10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho S, Javadi D, Causevic S, et al. Intersectoral and integrated approaches in achieving the right to health for refugees on resettlement: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e029407. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MS, Song IG, An AR, et al. Healthcare access challenges facing six African refugee mothers in South Korea: a qualitative multiple-case study. Korean J Pediatr 2017;60:138–44. 10.3345/kjp.2017.60.5.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World mental health report: transforming mental health for all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phanwichatkul T, Schmied V, Liamputtong P, et al. The perceptions and practices of Thai health professionals providing maternity care for migrant Burmese women: an ethnographic study. Women Birth 2022;35:e356–68. 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang SH-C, Hall WA, Campbell S, et al. Experiences of Chinese immigrant women following “Zuo Yue Zi” in British Columbia. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:e1385–94. 10.1111/jocn.14236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merry LA, Gagnon AJ, Kalim N, et al. Refugee claimant women and barriers to health and social services post-birth. Can J Public Health 2011;102:286–90. 10.1007/BF03404050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heslehurst N, Brown H, Pemu A, et al. Perinatal health outcomes and care among asylum seekers and refugees: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Med 2018;16:89. 10.1186/s12916-018-1064-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tinghög P, Malm A, Arwidson C, et al. Prevalence of mental ill health, traumas and postmigration stress among refugees from Syria resettled in Sweden after 2011: a population-based survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018899. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makuch MY, Osis MJD, Brasil C, et al. Reproductive health among Venezuelan migrant women at the north western border of Brazil: a qualitative study. J Migr Health 2021;4:100060. 10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, et al. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet 2018;392:2203–12. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31668-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devakumar D, Abubakar I, Tendayi Achiume E, et al. Executive summary. Lancet 2022;400:2095–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02485-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalich A, Heinemann L, Ghahari S. A scoping review of immigrant experience of health care access barriers in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 2016;18:697–709. 10.1007/s10903-015-0237-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodward A, Howard N, Wolffers I. Health and access to care for undocumented migrants living in the European Union: a scoping review. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:818–30. 10.1093/heapol/czt061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Migrants,refugees, and societies. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akhavan S, Edge D. Foreign-born women’s experiences of community-based Doulas in Sweden--a qualitative study. Health Care Women Int 2012;33:833–48. 10.1080/07399332.2011.646107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alshawish E, Marsden J, Yeowell G, et al. Investigating access to and use of maternity health-care services in the UK by Palestinian women. Br J Midwifery 2013;21:571–7. 10.12968/bjom.2013.21.8.571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chu CMY. Postnatal experience and health needs of Chinese migrant women in Brisbane, Australia. Ethn Health 2005;10:33–56. 10.1080/1355785052000323029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crowther S, Lau A. Migrant polish women overcoming communication challenges in Scottish maternity services: a qualitative descriptive study. Midwifery 2019;72:30–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies MM, Bath PA. The maternity information concerns of Somali women in the United Kingdom. J Adv Nurs 2001;36:237–45. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurman TA, Becker D. Factors affecting Latina immigrants’ perceptions of maternal health care: findings from a qualitative study. Health Care Women Int 2008;29:507–26. 10.1080/07399330801949608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higginbottom GMA, Safipour J, Yohani S, et al. An ethnographic study of communication challenges in maternity care for immigrant women in rural Alberta. Midwifery 2015;31:297–304. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higginbottom GM, Safipour J, Yohani S, et al. An ethnographic investigation of the maternity healthcare experience of immigrants in rural and urban Alberta, Canada. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:20. 10.1186/s12884-015-0773-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoban E, Liamputtong P. Cambodian migrant women’s postpartum experiences in Victoria, Australia. Midwifery 2013;29:772–8. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lam E, Wittkowski A, Fox JRE. A qualitative study of the postpartum experience of Chinese women living in England. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2012;30:105–19. 10.1080/02646838.2011.649472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLeish J. Maternity experiences of asylum seekers in England. Br J Midwifery 2005;13:782–5. 10.12968/bjom.2005.13.12.20125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Origlia Ikhilor P, Hasenberg G, Kurth E, et al. Communication barriers in maternity care of allophone migrants: experiences of women, healthcare professionals, and intercultural interpreters. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:2200–10. 10.1111/jan.14093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillimore J. Delivering maternity services in an era of superdiversity: the challenges of novelty and newness. Ethnic and Racial Studies 2015;38:568–82. 10.1080/01419870.2015.980288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riggs E, Davis E, Gibbs L, et al. Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:117. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riggs E, Yelland J, Szwarc J, et al. Fatherhood in a New Country: a qualitative study exploring the experiences of Afghan men and implications for health services. Birth 2016;43:86–92. 10.1111/birt.12208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renzaho AMN, Oldroyd JC. Closing the gap in maternal and child health: a qualitative study examining health needs of migrant mothers in Dandenong, Victoria, Australia. Matern Child Health J 2014;18:1391–402. 10.1007/s10995-013-1378-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sami J, Quack Lötscher KC, Eperon I, et al. Giving birth in Switzerland: a qualitative study exploring migrant women’s experiences during pregnancy and childbirth in Geneva and Zurich using focus groups. Reprod Health 2019;16:112. 10.1186/s12978-019-0771-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wikberg A, Eriksson K, Bondas T. Intercultural caring from the perspectives of immigrant new mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2012;41:638–49. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yelland J, Riggs E, Wahidi S, et al. How do Australian maternity and early childhood health services identify and respond to the settlement experience and social context of refugee background families? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:348. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Almeida LM, Casanova C, Caldas J, et al. Migrant women’s perceptions of healthcare during pregnancy and early motherhood: addressing the social determinants of health. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:719–23. 10.1007/s10903-013-9834-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]