Selection (adverse or advantageous) is the central problem that inhibits the smooth, efficient functioning of competitive health insurance markets. Even—and perhaps especially—when consumers are well-informed decision makers and insurance markets are highly competitive and offer choice, such markets may function inefficiently due to risk selection. Selection can cause markets to unravel with skyrocketing premiums and can cause consumers to be under- or overinsured. In its simplest form, adverse selection arises due to the tendency of those who expect to incur high health care costs in the future to be the most motivated purchasers. The costlier enrollees are more likely to become insured rather than to remain uninsured, and conditional on having health insurance, the costlier enrollees sort themselves to the more generous plans in the choice set. These dual problems represent the primary concerns for policymakers designing regulations for health insurance markets.

In practice, identifying selection problems and designing policy responses is not always straightforward. A natural starting point for uncovering selection distortions is a comparison of the chronic health conditions of consumers who elect more- versus less-generous insurance. However, selection can play out in complex ways that extend beyond issues of who remains uninsured and who chooses which plan.

Consider a market in which two essentially identical plans compete for enrollees and earn zero profits. All consumers opt to purchase insurance (in one plan or the other) due to a generous government subsidy. Because consumers perceive these plans as indistinguishable, they choose between them seemingly at random. Thus, neither plan differentially attracts sick or healthy consumers, and no one decides to remain uninsured. At first, it might appear that there are no selection problems. But what if we notice that neither plan offers good coverage for cancer treatments? It might be that both plans believe that offering such coverage would attract especially costly patients and would drive the plan to insolvency. Both plans thus attempt to screen out these patients by offering coverage that is unappealing to cancer patients. Because the two plans act identically, neither succeeds in avoiding cancer patients, and both plans get an equal share of such patients. But the result is that cancer patients cannot find good coverage in the market, and currently healthy consumers cannot find a plan to protect them against the possibility of needing cancer care in the future. Despite the fact that that we observe no systematic sorting of sick consumers between the available plans, this too would be a selection-driven distortion: there is a missing market for cancer coverage due to the anticipation of how the sick would sort themselves if a certain kind of coverage were offered.

In this essay, we review the theory and evidence concerning selection in competitive health insurance markets and discuss the common policy tools used to address the problems it creates. We begin in the next section by outlining some important but often misunderstood differences between two types of conceptual frameworks that economists use to think through selection. The first, the fixed contracts approach, takes insurance contract provisions as given and views selection as influencing only insurance prices in equilibrium. This is useful for thinking through selection problems on the extensive margin like “death spirals,” in which the healthy choose to remain uninsured and prices can spiral upwards as the consumers remaining enrolled are increasingly sick and costly. This framework is also helpful in understanding how government subsidies to purchase insurance can arrest this feedback mechanism. The second broad framework, the endogenous contracts approach, treats selection as also influencing the design of the contract itself, including the overall level of coverage and coverage for services that are differentially demanded by sicker consumers. This approach is useful for understanding “cream skimming,” in which various contract features are designed to attract or deter certain kinds of enrollees, such as with our cancer patients above. This modeling framework is also helpful in understanding the motivation for policy tools like risk adjustment and requirements that insurance policies offer certain minimum essential health benefits.

After outlining the selection problems, we discuss four commonly employed policy instruments that affect the extent and impact of selection: 1) premium rating regulation, including “community rating”; 2) consumer subsidies or penalties to influence the take-up of insurance; 3) risk adjustment, which is a policy that adjusts payments to private insurance companies based on the expected health care costs of enrollees; and 4) contract regulation, often involving rules for the minimum of what must be covered by the privately provided health insurance contract. We discuss the economics of these policy approaches and present available empirical evidence on their consequences, with some emphasis on the two markets that seem especially likely to be targets of reform in the short and medium term: Medicare Advantage (the private plan option available under Medicare) and the state-level individual insurance markets.

Adverse Selection, Through the Lenses of Fixed and Endogenous Contracts

We describe two conceptual approaches to modeling adverse selection: a fixed contract approach, in which the available insurance policies are taken as given, and an endogenous contracts approach, in which insurance providers design the elements of contracts in a way that seeks to attract those with relatively low expected use of health care. Neither the fixed nor endogenous contracts framework is superior in all applications; instead, each is useful in characterizing certain types of selection problems and in designing appropriate regulatory responses. As we work through these ideas, we will use the term selection primarily to describe actions by consumers as they sort themselves into and out of insurance and across plans. We will use the term screening to differentiate the actions of plans as they respond to and anticipate consumer sorting.

Generally, adverse selection arises because consumers have private information that is not accessible to the insurance provider or because the insurer is prohibited from conditioning insurance prices on observable information like age, gender, and medical history, effectively making such information private. Given a fixed set of contracts (not an innocuous assumption), consumers who expect, based on their private information, to have low health care expenses will select themselves into the lower-cost plans, while those who expect to have high health care expenses will select themselves into higher-cost, higher-coverage plans. In principle, selection in insurance markets need not be adverse in this sense, but in health insurance, the clear empirical pattern across a variety of market settings is one of adverse selection.

What we call the fixed contracts approach follows this intuition very directly. It models consumers as selecting across a very limited set of insurance contracts on the basis of private health status information. For example, under this framework a researcher might study, or a policymaker might consider, a market with two differentiated plans: a high-coverage contract (such as a generous preferred provider organization plan with low cost sharing) and a low-coverage contract (such as a high-deductible plan). The reason why the specific coverage levels of the high- and low-benefits contracts are chosen is typically unmodeled. In empirical applications, the fixed contracts assumption usually amounts to assuming that whatever plans are currently observed in the market are the only plans that could exist, regardless of changes to consumer demand, changes to the value of the outside option such as charity care, or changes to the regulatory structure of the market.

Under the fixed contracts approach, the insurance company does not respond to the pressures of selection by altering the generosity of the high-benefit contract—say, by limiting the size of the provider network, requiring larger copayments for certain services, or using “utilization review” to limit the provision of certain kinds of care. In equilibrium, the forces of selection affect plan prices, and perhaps whether a segment of the market completely unravels with certain plan types exiting altogether, but that is all.

Under this framework, efficiency losses occur when selection distorts contract prices and consequently consumers do not sort efficiently across contracts (or across the choice between insurance and uninsurance). Einav and Finkelstein (2011, in this journal) treat the welfare economics of this case in detail in a series of intuitive diagrams. We refer the reader to that article for a full discussion of this framework. Here, we briefly note that the typical adverse selection result is that more generous coverage sells only at very high prices. Higher prices for the generous contract imply fewer enrollees, who will be costlier on average than those in the less-generous contract. In a competitive equilibrium, these fewer, costlier enrollees imply higher break-even prices, completing the feedback loop between prices, average costs, and enrollment in the generous contract. Low-cost, healthy consumers, who value generous coverage more than the social cost of providing it to them, are not offered it at a price that they are willing to pay. Thus, from the perspective of social efficiency too few consumers enroll in more generous coverage.

The fixed contracts framework has been popular among empirical economists because in addition to allowing for relatively straightforward characterizations of equilibrium prices and enrollment given exogenous variation in insurance prices, it allows for straightforward welfare analysis (for example, Einav, Finkelstein, and Cullen 2010). It also appears to characterize accurately the employer-sponsored insurance setting, the channel through which the majority of Americans receive health insurance. However, a number of observations about private insurance markets like the Marketplaces created by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 and Medicare Advantage raise questions about whether a framework that assumes only prices (and not other contract features) respond to selection is sufficient for fully characterizing the impact of adverse selection on social welfare in these settings. Two particular observations raising concerns are: the widespread presence of insurance contracts that offer 1) narrow provider networks and 2) restrictive drug formularies.

First, consider narrow provider networks. In the state-level health insurance Marketplaces, Bauman, Bello, Coe, and Lamb (2015) find that around 55 percent of available plans have hospital networks that are deemed “narrow,” meaning that they include from 31–70 percent of area hospitals, or “ultra-narrow,” including less than 30 percent of area hospitals. With respect to physician networks, Polsky and Weiner (2015) find that 11 percent of plans have networks with fewer than 10 percent of physicians in the area and 65 percent of plans have networks with fewer than 40 percent of physicians in the area—with networks being even narrower for physicians specializing in the treatment of cancer. In Medicare Advantage, Jacobson, Trilling, Neumann, Damico, and Gold (2016) find that the average plan in a given county covers only around 50 percent of hospitals in the county, and 9 of 20 cities studied in their report do not have a single plan with a “broad” hospital network, defined as more than 70 percent of hospitals in the area.

Second, drug formularies, which list consumer cost-sharing amounts for prescription medications, are often much more restrictive in the state-level Marketplaces than in employer-sponsored plans. The state-level Marketplace plans are much more likely than employer plans to place entire therapeutic classes of drugs on high cost-sharing “specialty” tiers, exposing consumers to significantly more out-of-pocket spending, and to place nonprice barriers on drugs like prior authorization or step therapy requirements (Jacobs and Sommers 2015; Geruso, Layton, and Prinz 2016).

While narrow networks and restrictive formularies could be efficient reactions to consumer preferences for lower-cost insurance products, they could also be driven by adverse selection.1 Consider an insurer designing a drug formulary in a competitive market setting in which plans cannot directly reject applicants and in which regulation prevents price discrimination between applicants. Competition induces such an insurer to increase the generosity of the formulary until the costs of additional generosity exceed the benefit to its enrollees. But as the insurer improves the quality of its formulary, it may attract a different set of customers who are likely to have high health care costs. For example, using claims data discussed below, it is straightforward to observe that consumers who use immunosuppressant drugs to treat conditions like rheumatoid arthritis generate costs in excess of $30,000 annually, while paying a premium that is a small fraction of that amount. In a market setting that outlaws premium discrimination (also known as “medical underwriting”), all insurers may offer symmetrically poor coverage for classes of drugs like immunosuppressants to discourage such patients from joining their plans. Deviations from that strategy could yield the unhappy outcome for the insurer of cornering the market on these unprofitable patients, with limited ability to spread the costs of such patients across the rest of the risk pool. This dynamic could result in an inefficient equilibrium where all of the available insurance contracts provide too little coverage for immunosuppressants. This type of inefficiency would be missed when using a fixed contracts framework that assumes that adverse selection only distorts prices of observed contracts because, in this case, the equilibrium set of contracts available for purchase is itself distorted.

In short, adverse selection (and its policy remedies) may affect not only the prices of contracts but also the design of the contracts themselves. We refer to models that allow for this possibility as endogenous contract frameworks. Such models may include a continuum of potential insurance contracts, including contracts not currently observed in the market, rather than just a small number of observed contracts like the high-benefit and low-benefit contract example mentioned earlier. The key feature of these models is that they allow selection to influence the design of the contracts that insurers offer in equilibrium rather than assuming that the observed set of contracts represents the entire contract space.

To gain intuition for the endogenous contracts approach, consider the case where there are two types of consumers, healthy (inexpensive) and sick (costly). The healthy do not wish to subsidize the sick, so they demand plans that screen out the sick by offering less-generous coverage at a lower price, leading to a separating equilibrium in which the sick purchase full coverage at a high price and the healthy inefficiently purchase only partial coverage at a lower price (Rothschild and Stiglitz 1976). It is important to understand that the degree of partial coverage is an equilibrium outcome: Will the low plan cover 80 percent of expenses or just 60 percent? This depends on the extent of the difference between sick and healthy consumers, as well as the presence of any risk-based transfer payments enforced by the regulator.

The use of a contract feature as a screening device is commonly known as “cream skimming.” More recent theoretical work has examined screening when there are many types of consumers (Azevedo and Gottlieb 2017) and when markets are imperfectly competitive (Veiga and Weyl 2016). In some cases, this type of adverse selection may lead to some types of consumers being unable to purchase insurance with any level of coverage (Hendren 2013).

A further complication, which matters in practice for consumers but is missed by the fixed contracts framework, is the multidimensional nature of coverage in modern health insurance contracts. Consider the possibility that costs of physical and mental health care may be covered differently. Assume that both the inexpensive and costly consumer types have similar probabilities of using physical health services, but let the costly type have higher probability of requiring mental health services. Again, the inexpensive consumers wish to avoid subsidizing the costly ones, but now, instead of demanding plans that screen out the sick by limiting total coverage, the healthy demand plans that screen out the sick by limiting coverage for mental health services only, while maintaining full coverage for physical health services. This dynamic can lead to a separating equilibrium where the costly patients purchase a contract providing full coverage for physical and mental health services at a high price, while the inexpensive consumers purchase a contract providing full coverage for physical but only partial coverage for mental health services (Glazer and McGuire 2000). Again, this outcome is inefficient if the inexpensive types value full coverage for both physical and mental health services more than the social cost of providing it to them. In other models, all consumers, both healthy and sick, are worse off when they are combined in the same market because all plans offer poor coverage for services that the sick are more likely to require (Frank, Glazer, and McGuire 2000; Veiga and Weyl 2016). The various models nested in the endogenous contracts framework differ in their equilibrium concepts, whether they assume perfect competition, and in their restrictions on the contract space, but all result in the equilibrium set of contracts being different from, and usually less generous on average than, the efficient set of contracts.

While the endogenous contracts settings are more general than the fixed contracts setting, they are also clearly much more complicated. In part, this is because the contract space is large, with many hard-to-observe and hard-to-measure dimensions—for example, coverage for a specific drug, whether a particular specialist is included in the provider network, or the level of hassle involved with scheduling a visit with an in-network or out-of-network mental health provider. Thus, in contrast to the fixed contracts framework, calculating the welfare consequences of contract distortions has generally involved imposing significant theoretical structure while analyzing calibrated counterfactuals that may extend uncomfortably out-of-sample. The unresolved challenges of estimating welfare in an endogenous contracts framework in a transparent way are a critical avenue for future work, with the potential for important policy applications. In the meantime, however, the endogenous contract problem remains empirically important and motivates much of the regulatory action in Medicare and the Marketplaces—in particular regulations targeting the quality of coverage available rather than just the portion of people who choose to purchase coverage. The lack of a welfare framework equal in elegance to the fixed contracts framework is no reason for economists to ignore these types of market failures.

In the sections that follow, we build on the fixed and endogenous frameworks to discuss the most common selection-related government policies used in regulated private health insurance markets. We begin with premium rating regulations, which are policies primarily aimed at equity concerns but which interact with selection, often making selection problems worse.

Premium Rating Regulations and Community Rating

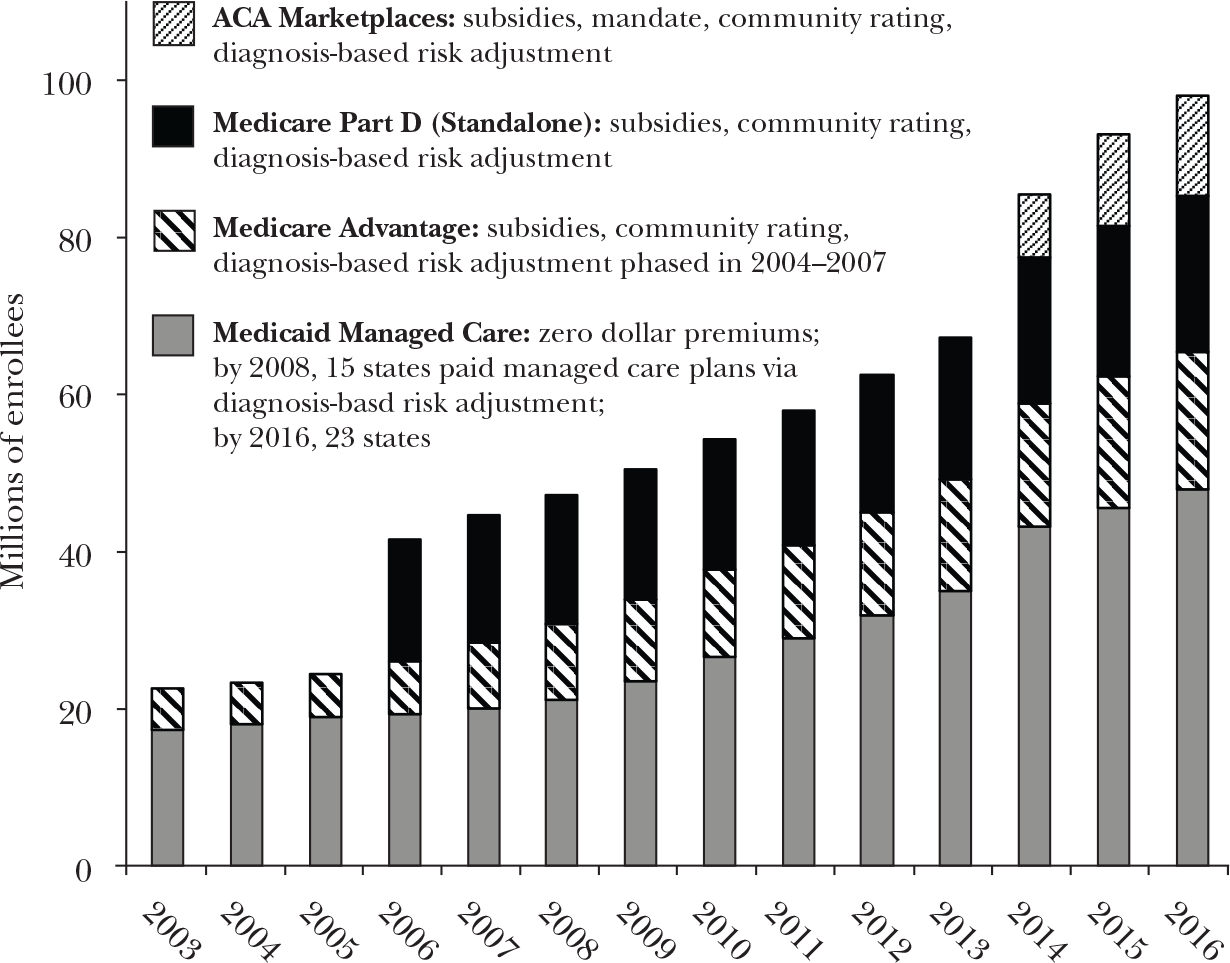

Outside of large employer settings, health insurance in the United States is increasingly organized around private insurers competing for enrollees in highly regulated and often publicly subsidized markets. As public programs like Medicare and Medicaid turn to private insurers to deliver benefits, selection-related policies have risen in importance. Figure 1 shows the dramatic growth in the use of regulated private health insurance markets to provide public health insurance benefits over the last 15 years. Over 60 percent of Medicaid recipients choose plans in a market-like setting where they face a choice between a public fee-for-service option and a private managed care plan, or more frequently, between multiple private managed care alternatives. In Medicare, 19 million beneficiaries (33 percent) choose to receive their physician and hospital coverage from a private Medicare Advantage plan, and an additional 20 million beneficiaries purchase private prescription drug insurance in the highly subsidized and tightly regulated Medicare Part D program. Finally, for individuals who do not receive health insurance from their employer or from another public program, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 introduced state-based Health Insurance Marketplaces (“Marketplaces”), which have provided a new publicly subsidized, privately provided health insurance benefit for millions of lower-income Americans.

Figure 1. The Rise of Markets, Choice, and Selection Regulation in Public Health Benefits.

Note: ACA is the Affordable Care Act.

The markets/programs listed in Figure 1 share the feature that consumers can choose among competing insurance products and that insurers are not allowed to price discriminate between consumers or to reject applicants. In each of these markets, regulators also require certain minimally acceptable benefits packages, use risk adjustment to compensate insurers for enrolling high-expected-cost patients, and offer subsidies to lower-income enrollees to encourage take-up. We begin here by discussing restrictions on insurers’ ability to price discriminate, also known as premium rating restrictions.

Premium rating restrictions govern whether and how prices may vary across consumers for a given insurance product. A complete prohibition against price discrimination within a local rating area is called “community rating.” In the case of Medicare Advantage plans, full community rating is used: The small beneficiary contributions to the highly subsidized plan premiums cannot vary across enrollees within the local market, regardless of age, sex, or medical history. The state-level Marketplaces use modified community rating, in which prices can vary within a geographic market only by age and by smoking status in a prescribed way. In most state-level Marketplaces, the premium for a 64 year-old is restricted to be exactly three times the premium for a 21 year-old, with premiums at each intermediate age set using a regulator-specified age-price curve. In the absence of these types of restrictions, one might expect competition to drive an insurer to charge each consumer a premium equal to that buyer’s expected cost, thus leading to high premiums for the sick and low premiums for the healthy.

Premium rating restrictions generally exacerbate adverse selection problems, because premium rating imposes an information asymmetry between the consumer and insurer. Specifically, insurers are required to ignore signals that would be informative about an individual’s expected health care costs when setting prices. Buchmueller and DiNardo (2002) show that the shift of New York’s individual and small group health insurance markets to community rating in the 1990s led to consumers shifting from fuller coverage plans to more restrictive health maintenance organizations, consistent with the endogenous contracts literature discussed above. By 2013, prior to the Affordable Care Act taking effect, New York’s individual health insurance market had experienced almost a complete “death spiral,” with only 17,000 individuals enrolled in the market and 2.1 million individuals uninsured (Rabin and Abelson 2013).

Despite these potential negative consequences, premium rating restrictions are extremely popular among consumers and policymakers and are currently in place in almost all health insurance markets in the United States and in other high-income countries. Why? Fairness motivations are typically cited; indeed, the section of the ACA that establishes premium rating rules is titled “Fair Health Insurance Premiums.”

But there is also a clear economic rationale for such rules. It involves long-run risk (Cochrane 1995; Handel, Hendel, and Whinston 2015; Hendren 2017). Risk-averse consumers value not only coverage for fluctuations around their expected annual health spending, such as due to a broken bone; they also value coverage for health state transitions, such as developing diabetes, that may permanently affect their expected health care consumption and thus their health insurance premiums in the absence of premium rating regulations.

Much of the prior literature—from Rothschild and Stiglitz (1976) to Einav and Finkelstein (2011) and some of our own work as well—has focused on the value of insurance in smoothing one-period risk, which can be viewed as insurance against the variation in health care spending when fundamental health status is not changing. This focus on one-period risk carries the awkward implication that optimal insurance for an expensive cancer patient may involve a $60,000 premium, because the goal of insurance is to protect that patient from uncertainty over whether treatments cost $50,000 or $70,000 this year. In contrast, restrictions that prohibit plans from setting different premiums based on health status—including those in the federal rules that have governed employer health plans since 1974—take the longer view. In this view, insurance seeks to cover the risk of becoming reclassified as an expensive patient in some future period. In an unregulated market, such reclassification would mean facing significantly higher health insurance premiums.2

Empirically, this reclassification risk seems important. More than half of US households contain a member with a pre-existing condition (Kaiser Family Foundation 2016). Calibrations by Handel, Hendel, and Whinston (2015) suggest that the welfare benefits of eliminating reclassification risk may swamp the welfare costs of one-period adverse selection. While we feel obligated to bring attention to this understudied and important issue, we will focus here primarily on the interaction between policies like community rating that address this reclassification risk, and selection.3

Subsidies and Penalties Related to Taking Up Health Insurance

On the extensive margin between purchasing any insurance or none, policies that involve premium subsidies or penalties for not purchasing insurance (also known as coverage “mandates”) are often used to combat selection problems, including the information asymmetries introduced by community rating. The rationale from economic theory for subsidies/penalties related to taking up insurance is most clear from the perspective of the fixed contracts framework, in which adverse selection into the risk pool drives prices to become inefficiently high at the market level.

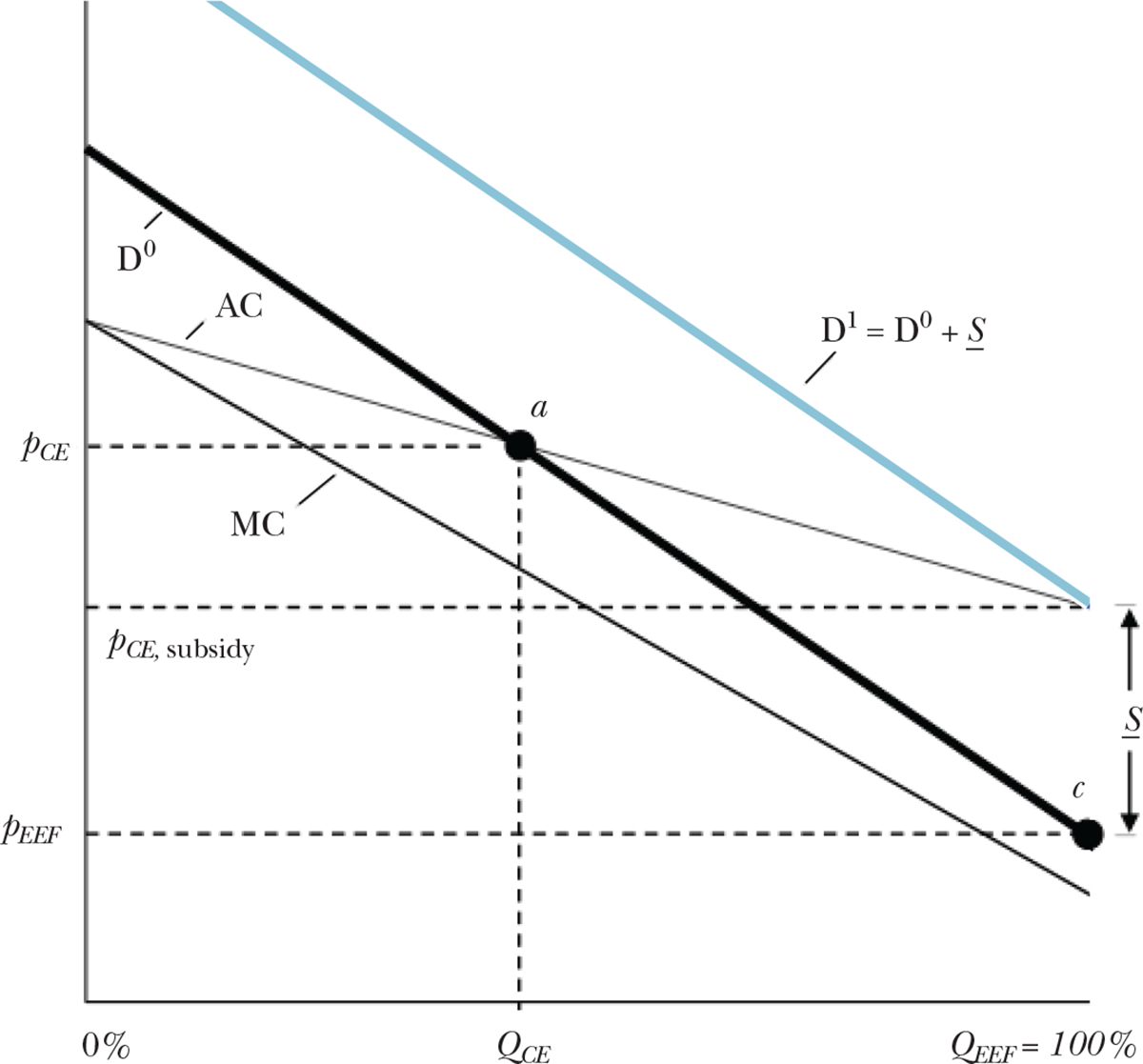

Consider Figure 2, where we follow the basic setup of Einav and Finkelstein (2011), and examine the margin of consumers choosing between taking up insurance and remaining uninsured. The horizontal axis is scaled from 0 to 100 percent enrollment of the population, so that the demand curve D0 reflects the willingness-to-pay for insurance of the marginal consumer at each level of enrollment. The vertical axis measures prices or costs in dollar terms. The marginal costs (MC) of enrollees slope downward, because adverse selection implies the highest willingness-to-pay consumers are those who generate the highest costs to insure. Demand and costs are more closely linked here than in the typical goods market, where the production technology determines a marginal cost that is independent of the particular consumer who purchases the good. Following the standard model, the competitive equilibrium QCE is determined by point a, the intersection of average costs (AC) and demand, where insurers earn zero profits. The efficient outcome is at point c, full enrollment, because in this example the demand curve is everywhere above the marginal cost curve, implying that willingness-to-pay exceeds individual-specific marginal costs to the plan for every individual.4 Here, society as a whole (consumers + insurers) would be made better off if all consumers took up insurance.

Figure 2. Subsidies/Penalties and the Fixed Contracts Price Distortion.

Notes: We follow the basic setup of Einav and Finkelstein (2011), and examine the margin of consumers choosing between taking up insurance and remaining uninsured. The horizontal axis is scaled from 0 to 100 percent enrollment. The vertical axis measures prices or costs in dollar terms. The demand curve D0 reflects the willingness-to-pay for insurance of the marginal consumer at each level of enrollment. The marginal costs of enrollees slope downward, because adverse selection implies the highest willingness-to-pay consumers are those who generate the highest costs to insure. Following the standard model, the competitive equilibrium QCE is determined by point a, the intersection of average costs and demand, where insurers earn zero profits. The efficient outcome is at point c, full enrollment, because in this example the demand curve is everywhere above the marginal cost curve. A uniform subsidy, S, equal to the difference between the rightmost point of the average cost curve and the rightmost point of the demand curve is the minimum uniform subsidy that will induce efficient sorting in this setting. If instead of a subsidy, a penalty were applied to the outside option of remaining uninsured, then S would define the minimum uniform penalty.

A uniform subsidy equal to the difference between the rightmost point of the average cost curve and the rightmost point of the demand curve is the minimum uniform subsidy that will induce efficient sorting in this setting. Call this minimum subsidy S. Offering S can be viewed as shifting up the effective demand to intersect the average cost curve at exactly Q = 100 percent. Equivalently, offering S can be viewed as lowering the effective price perceived by consumers to the efficient price, pEFF. If instead of a subsidy, a penalty were applied to the outside option of remaining uninsured, then S would define the minimum uniform penalty.

Importantly, S here is lower than the difference between pCE (the competitive equilibrium price) and pEFF (the efficient price). In other words, it appears to be the case that we have gotten something for nothing in reducing net prices by more than the subsidy amount. This happens because as more enrollees with lower marginal costs enter the market, they drive down average costs and therefore subsidize the competitive equilibrium price, which is equal to average cost. Thus, in adversely selected markets and under the assumptions given here, subsidies have a greater than one-for-one return in terms of lowering prices.

To determine S precisely, the regulator must be able to identify the full demand and cost curves, including any nonlinearities. However, any subsidy greater than the minimum S will also efficiently allocate consumers across plans, which allows the regulator significant room for error in setting the subsidy when the goal is full insurance. Of course, it may not be the case that the demand curve is everywhere above the marginal cost curve, implying that there are people whose valuation of insurance is less than the social cost of providing it to them. This could be due to moral hazard or nonnegligible loading costs (for example, costs incurred in marketing and claims administration) combined with low risk aversion. In this case, a subsidy that is too large causes welfare losses by inducing enrollment among consumers who value insurance below its marginal cost.

Yet another practical consideration is the deadweight loss from the taxes funding the subsidy. Even when the social optimum is full insurance, the cost of public funds needs to be taken into account when evaluating any publicly funded subsidy scheme. In light of this, penalties for not purchasing insurance may be preferable to subsidies. Penalties can induce allocative efficiency without requiring government expenditures, other than on enforcement. Incidence also differs: Subsidies fall on all enrollees, whereas penalties are more likely to bite for the population on the margin of making the choice to remain uninsured. However, penalties are politically unpopular, difficult to enforce, and may conflict with additional (and sometimes more prominent) distributional goals related to the notion of affordability. In particular, policymakers may be hesitant to force large penalties on low-income consumers.

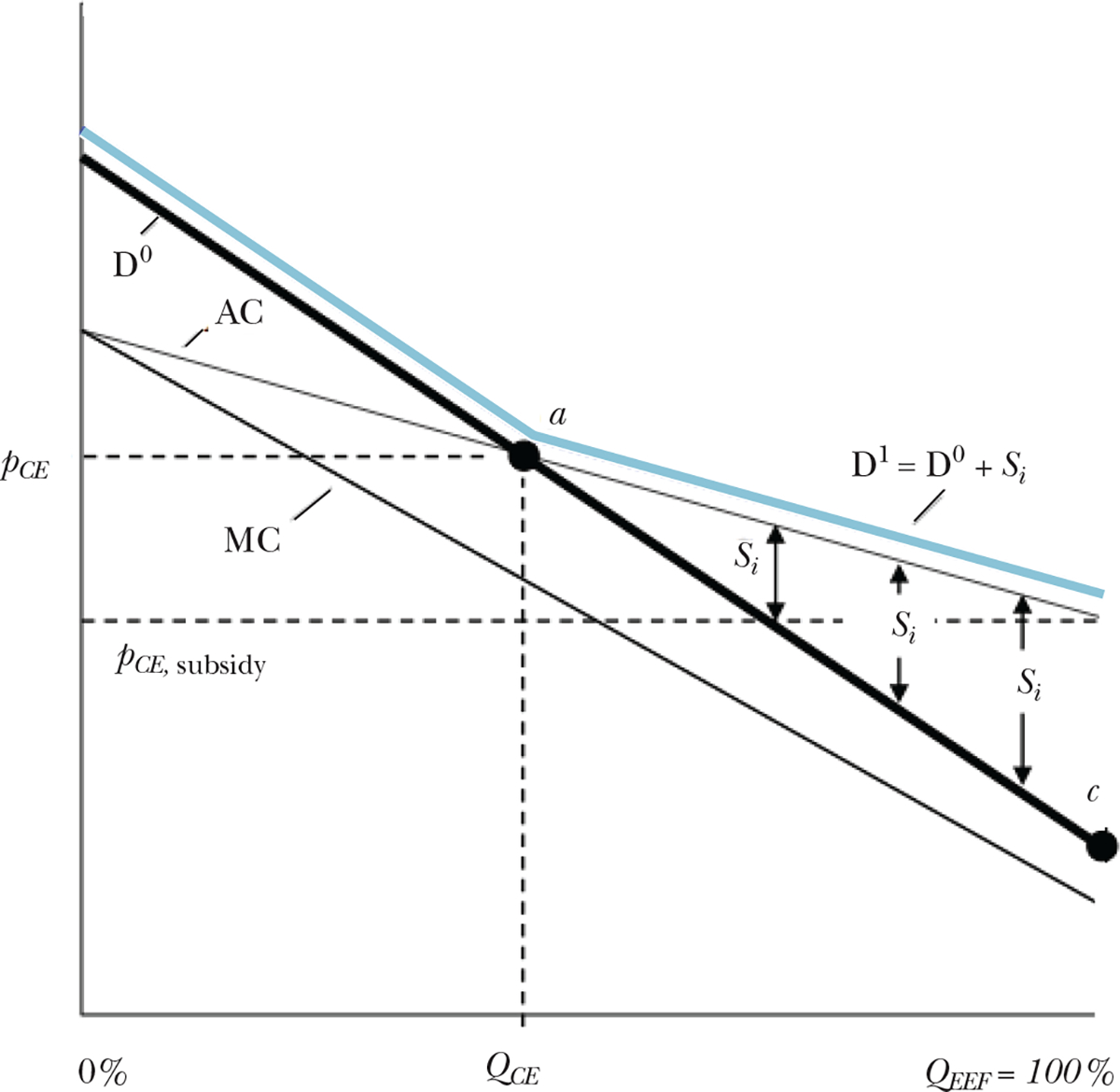

Given the difficulties of implementing penalties, one might then ask whether there are ways to improve upon the minimum uniform subsidy, S. A policy of subsidies targeted to the consumers with lowest willingness-to-pay for insurance may be more efficient than uniform subsidies. In Figure 3, we consider a candidate policy of paying person-specific subsidies Si for the set of consumers to the right of point a. For these consumers, the subsidy would be pivotal in their take-up decision. This subsidy schedule would generate the effective demand curve D1, which adds the variable subsidy to the original demand curve, D0. This subsidy scheme would achieve the same universal coverage as S, but cost less. Costs would be lower both because fewer consumers would receive the tailored subsidy and because the tailored amounts would be smaller than S for all but the lowest willingness-to-pay consumer.

Figure 3. Variable Subsidies Linked to Willingness-to-Pay.

Note: Here we consider a policy of paying person-specific subsidies Si for the set of consumers to the right of point a. For these consumers, the subsidy would be pivotal in their take-up decision. This subsidy schedule would generate the effective demand curve D1, which adds the variable subsidy to the original demand curve, D0. This tailored subsidy scheme would achieve the same universal coverage as the uniform subsidy S from Figure 2, but cost less.

How could such variable subsidies be targeted in practice, for example, in the state-level health insurance Marketplaces? Work in the context of the Massachusetts Exchange that was enacted before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 has shown that younger consumers are about twice as price sensitive as older consumers (Ericson and Starc 2015). Therefore, targeting subsidies to younger consumers is likely to achieve similar levels of allocative efficiency at a lower cost to the taxpayer than a uniform subsidy (Tebaldi 2017). In contrast, current policy proposals tend to favor subsidizing the highest cost enrollees such as via high-risk pool payments, or tying subsidies to age in the opposite pattern—offering larger subsidies to older, more expensive consumers. These are likely to be inefficient ways to address selection problems.5

Although we have focused so far on the competitive markets case, an additional complication inherent in designing subsidy schemes is the presence of imperfect competition. The portion of the subsidy that is passed through to consumers rather than extracted by producers (including insurers and health care providers) depends on the level of competition in the market. In the private Medicare Advantage context, on average about half of the dollar value of marginal changes in direct-to-plan subsidies are passed through to consumers in the form of lower premiums or lower cost sharing in a typical market (Curto, Einav, Levin, and Bhattacharya 2014; Song, Landrum, and Chernow 2013), with the largest pass-through rates in the most competitive local markets (Cabral, Geruso, and Mahoney 2014). These results suggest that market structure can have important effects on the consequences of a preset premium subsidy.

In practice, subsidies may also be dynamically linked to local market conditions, including to the prices that insurers set for their plans. This type of subsidy is used in the state-level Marketplaces, where tax credits are benchmarked to the price of the second-lowest price “Silver” plan. Jaffe and Shepard (2017) show that this type of price-linked subsidy distorts insurer prices because insurers that have some probability of having the second-lowest price plan will distort their prices upward to increase the size of the subsidy. On the other hand, this type of subsidy has the potential benefit that it protects subsidized consumers from changes in insurer prices (due to changes in technology, adverse selection, or other features) that are not anticipated by the regulator and thus cannot be incorporated into a fixed subsidy. Such a feature can be important in stabilizing a new market in which there is considerable uncertainty.

Clearly, implementing a mixture of mandates with penalties and subsidies involves a number of practical concerns. But despite these complications, the evidence to date indicates significant welfare gains from their use. For example, Hackmann, Kolstad, and Kowalski (2015) study the implementation of an individual mandate to purchase health insurance in Massachusetts that took the form of tax penalties paid by consumers who chose not to purchase coverage. They study the welfare consequences of the mandate assuming a fixed contracts model like Figure 2 and find an average welfare gain of 4.1 percent per person or a total of $51.1 million annually due to the penalty.

There is still a great deal we do not know about the use of mandates with penalties and subsidies as policy tools. First, there is work to be done to understand optimal subsidy schedules when subsidies can vary across consumers and when competition in the market is imperfect. Second, while economic theory suggests that tax penalties and subsidies for insurance are largely equivalent to the consumer (differing only in their income effect), there is no evidence of which we are aware that suggests consumers react symmetrically to subsidies and penalties in this context. Further, the effect of the combination of subsidies and penalties embedded in the state-level Marketplaces through the Affordable Care Act had heterogeneous effects across states (Kowalski 2014). It is unclear what is driving that heterogeneity. While cross-state differences before the Affordable Care Act in the regulatory environment and in rates of uninsurance are obvious candidates, it is possible that factors like active marketing by states to encourage enrollment or efforts by states to improve the consumer’s shopping experience played a role. Such effects may be important, but are inherently difficult to quantify.

Risk Adjustment

While selection along the extensive margin of insurance versus uninsurance is generally addressed via mandates backed by subsidies and penalties, the selection problems that arise on the intensive margin—that is, across plans within a market—are generally addressed by risk adjustment. We argue in this section that understanding why risk adjustment is so widely used requires a focus on this intensive margin and is further helped by examining insurance markets through the lens of endogenous, rather than fixed, contracts. We begin by outlining the mechanics of such a policy.

Mechanics of Risk Adjustment

Although the practical administration of risk adjustment is complicated in ways we will discuss below, the idea is simple: compensate plans for the expected costs of their enrollees and thereby remove the incentive to avoid high-expected-cost consumers, such as the cancer patients from our introduction. Thus, when an insurance company considers providing health insurance for a person, expected profits will be the premium received from this person minus the expected costs of providing coverage, plus a risk-adjustment payment.

To illustrate how risk adjustment works, consider Medicare Advantage, the private insurance option for hospital and physician coverage within the Medicare program. Estimation of a risk-adjustment transfer begins with calibrating the relationship between observables and costs in some reference population. In Medicare as in many settings, this is carried out via a simple ordinary least squares regression of annual patient costs on indicators for demographic variables and a small set of chronic disease indicators, derived from diagnosis codes in prior-year insurance claims. In Medicare, the right-hand-side variables also include indicators for Medicaid and disability status. In other settings, prescription drug utilization and other measures of prior health care use may be included. The estimated coefficients are then used to predict expected costs based on individual characteristics. These predictions from the risk adjustment regression are transformed into risk scores that are straightforward to interpret. A Medicare Advantage enrollee with a risk score of 1.5 would have expected costs equal to 150 percent of the costs of the typical enrollee in Traditional Medicare.

Finally, to determine the actual dollar size of the risk adjustment, risk scores are multiplied by some dollar amount, which for Medicare Advantage is roughly the cost of enrolling the typical-health Medicare beneficiary in Traditional Medicare in the local geographic market. In other words, this payment approximates what a person with these observable characteristics would have cost the taxpayer if the person had enrolled in Traditional Medicare. This risk-adjustment mechanism is simultaneously providing a premium subsidy and a selection correction.

In the setting of the Marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act, there is no equivalent of the Traditional Medicare program with which to benchmark risk scores. The Marketplace scheme uses instead the reference population of large employer plans. Risk scores are normalized against the average risk score in that market, and transfers are sent from plans with low-cost enrollees to plans with high-cost enrollees.

Theoretical Underpinnings of Risk Adjustment

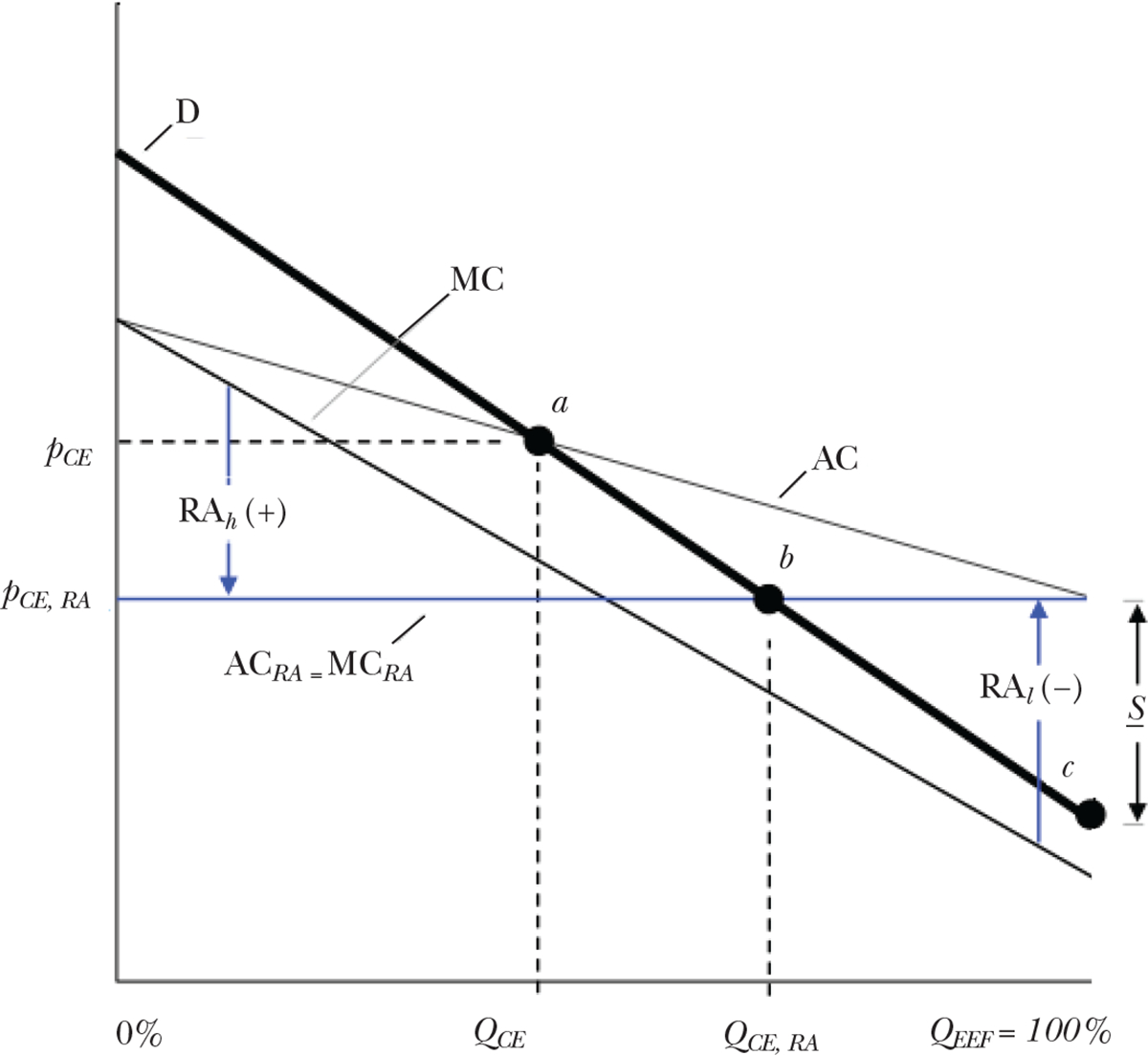

Figure 4 depicts the same baseline demand and risk selection conditions for the insurance/uninsurance setting described in Figure 2. Here we use it to provide intuition for how risk adjustment would only imperfectly address the price distortions that are described by the fixed contracts framework.

Figure 4. Risk Adjustment and the Fixed Contracts Price Distortion.

Notes: Larger positive risk adjustment payments, like RAh, are made by the regulators for individuals with larger expected costs, and smaller or negative payments like RAl, for enrollees with lower costs. Given the (arbitrary) demand and cost curves drawn in the diagram, the competitive equilibrium under risk adjustment is determined by point b. Enrollment with risk adjustment, QCE, RA, is higher than the unregulated case, and closer to the optimum. However, risk adjustment does not completely resolve the inefficiency by raising the enrollment rate to 100 percent, at least not without an additional subsidy.

Risk adjustment alters the competitive equilibrium by compensating for the individual-specific difference between marginal costs and the average population cost. This has the effect of rotating the insurer’s perceived marginal cost curve. Larger positive risk adjustment payments, like RAh, are made by the regulators for individuals with larger expected costs, and smaller or negative payments like RAl, for enrollees with lower costs. In the diagram, the solid horizontal line represents the net marginal cost perceived by the insurer in the case in which risk adjustment perfectly compensates for expected costs. This net marginal cost curve is flat at the level of the population average cost, arresting the feedback loop that would otherwise link equilibrium prices to the composition of the enrolled risk pool.

Although the insurer determines pricing according to perceived costs, the social marginal cost curve relevant for welfare analysis remains the original, downward sloping line, which implies that full enrollment remains the efficient outcome. Given the (arbitrary) demand and cost curves drawn in the diagram, the competitive equilibrium under risk adjustment is determined by point b. Enrollment with risk adjustment, QCE,RA, is higher than the unregulated case, and closer to the optimum.

However, risk adjustment does not completely resolve the inefficiency by raising the enrollment rate to 100 percent, at least not without an additional subsidy.6 While risk adjustment subsidizes insurers for enrolling sicker consumers (the positive RAh), it also taxes them for enrolling healthier consumers (the negative RAl). This tax on enrolling healthy consumers limits the extent to which risk adjustment can solve the inefficient sorting problem in settings where it is efficient for all consumers to purchase insurance. Mahoney and Weyl (2017) apply the fixed contract framework to show that in both perfectly and imperfectly competitive markets, risk adjustment may improve or worsen the allocation, depending on demand and selection. In our diagram, a subsidy of S would need to be employed in addition to risk adjustment to generate efficient sorting. From this perspective, risk adjustment appears to have done little: the same minimum subsidy of S from Figure 2 would be needed to achieve the optimum (QEFF = 100 percent) with or without risk adjustment.7

If risk adjustment does not solve the inefficiency in this setting, then why is this policy instrument so widely used? For one, budget-neutral risk adjustment may improve allocative efficiency to some extent without requiring the regulator to provide non-budget-neutral subsidies. Additionally, it is important to understand that risk adjustment is intended to address intensive margin (high- versus low-coverage) selection rather than the extensive margin (insurance versus uninsurance) selection problem depicted in Figure 2. Adapting the fixed contracts approach to the intensive margin problem, Layton (forthcoming) and Handel, Hendel, and Whinston (2015) show that conventional risk adjustment can eliminate most of the inefficiency caused by adverse selection across plans in a Marketplace-like setting, assuming consumers cannot opt out of coverage altogether. Handel, Kolstad, and Spinnewijn (2015) use a fixed contracts framework to show that risk adjustment can be complementary to policies that improve consumer choices, limiting the negative consequences of these choice-improving policies for adverse selection (Handel 2013).

But to understand fully the motivation for risk adjustment, one must consider not only intensive-margin selection across differentiated fixed contracts but also the endogenous design of those contracts. The most important objectives of risk adjustment are related to the design of health plan benefits, rather than prices. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, for example, thinks about risk adjustment as a way to counter “cream-skimming” behavior by insurers. The regulatory focus on cream-skimming suggests that regulators and policymakers are worried about the endogenous contracts distortions discussed earlier, rather than the price-feedback mechanism described in Figure 4.

In principle, risk adjustment can address insurer incentives to try to avoid certain patient types because risk adjustment can make all enrollees equally profitable to the insurer on net (Van de Ven and Ellis 2000; Breyer, Bundorf, and Pauly 2011). Intuitively, risk adjustment forces the healthy to subsidize the sick to some extent, no matter what contract they purchase. This limits the possibilities of an inefficient separating equilibrium with higher- and lower-coverage plans and can lead to an efficient pooling equilibrium where all consumers, both healthy and sick, fully insure (Glazer and McGuire 2000).

Risk Adjustment in Practice

In practice, it can be difficult to evaluate whether risk adjustment is functioning well, because risk adjustment is usually introduced to a market alongside other important regulatory changes. But between 2004 and 2007, Medicare Advantage transitioned to a risk adjustment system based on diagnoses for chronic conditions, while holding fixed other important features like community rating. After the implementation of diagnosis-based risk adjustment in 2004, Medicare Advantage plans enrolled beneficiaries who were sicker than their pre-risk adjustment enrollees (Brown, Duggan, Kuziemko, and Woolston 2014; Newhouse and McGuire 2014). This is consistent with risk adjustment successfully removing some of the financial incentive to avoid sicker, costlier patients.

However, the enrollment of additional sicker patients is not a sufficient statistic for judging the success of risk adjustment at combatting contract distortions due to adverse selection. If insurers respond to risk adjustment by switching away from designing contracts to attract low-cost individuals and instead move to designing contracts to attract individuals who are low cost conditional on their risk scores, a new class of distortions can arise. Brown, Duggan, Kuziemko, and Woolston (2014) and Newhouse, Price, McWilliams, Hsu, and McGuire (2015) provide evidence that while the set of Medicare beneficiaries switching from Traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage got sicker after 2004, the costs of these switchers conditional on their risk scores actually went down. This result is consistent with insurers cream-skimming by switching their plan design and marketing strategies away from targeting low-cost enrollees to targeting beneficiaries who are low-cost conditional on their risk scores (Aizawa and Kim 2015). But it is also consistent with insurers being willing to attract sicker consumers after the introduction of risk adjustment, and with the lower-cost consumers among the sick simply being more likely to take up Medicare Advantage compared to the higher-cost sick.8

A more direct piece of evidence regarding cream-skimming conditional on risk scores comes from Lavetti and Simon (2016). They examine Medicare contracts for pharmaceutical coverage in the post-risk adjustment period. They find that Medicare Advantage drug formularies differ from stand-alone Medicare Part D plan formularies in ways that are consistent with screening-in enrollees who were profitable conditional on risk adjustment. This finding suggests that even if risk adjustment has improved the equilibrium set of contracts in Medicare Advantage, some degree of distortion remains.

In the state-level Marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act, before-and-after comparisons are less clear. The introduction of risk adjustment in these programs was combined with major contemporaneous policy changes, and sorting out the effects is difficult. But there is at least some prima facie evidence that the Marketplace plans are being designed to attract enrollees who would likely have been highly unprofitable without risk adjustment. For example, Aetna launched Marketplace plans for 2016 that were specifically marketed toward diabetics, with features like differentially low cost-sharing for specialist visits linked to diabetes management (Andrews 2015).

In summary, without risk adjustment, the incentive for an insurer to distort coverage for a particular dimension of the contract is determined only by the cost of the consumers who value that dimension of the contract. With risk adjustment, there is variation in both cost and revenue across consumers. Thus, risk adjustment may change the margin of selection, rather than eliminate it entirely.

To make these ideas concrete, in Figure 5 we compare consumer costs and risk-adjusted revenues based on the Marketplace risk adjustment scheme. The figure is based on detailed health claims data for about 12 million consumers who are enrolled in plans offered by their large employers.9 Note that these are not Marketplace claims data. But they are instructive regarding the incentives embedded in the Marketplace payment formulas. The claims data allow direct observation of costs. The claims data also include all of the diagnosis information necessary to calculate risk adjustment payments implied by Marketplace formulas. We use the risk adjustment software from the regulator to generate hypothetical risk adjustment transfers associated with each enrollee, as if the enrollee’s claim history had been generated while enrolled in a Marketplace plan.

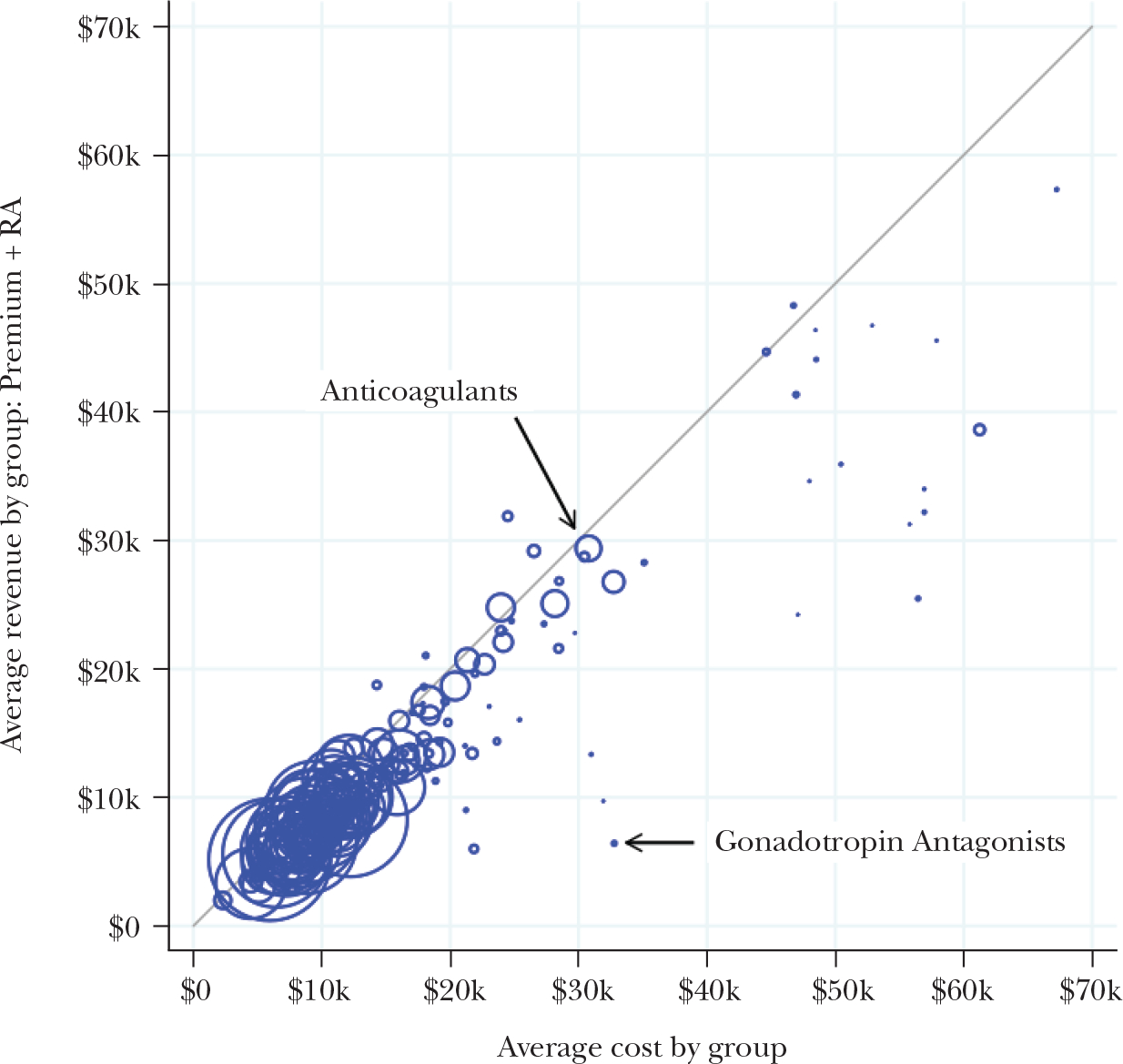

Figure 5. Incentives to Screen May Remain Net of Risk Adjustment.

Note: We classify individuals according to whether they have a pharmacy claim for a drug within one of 220 standard therapeutic classes of medications. Each circle in the figure corresponds to a therapeutic class, grouping together all consumers who used a drug in the class. Marker sizes are proportional to the numbers of consumers associated with each class. The horizontal axis measures mean total spending among consumers utilizing a drug in the class, and the vertical axis measures the mean simulated revenue (actuarially fair premiums plus risk adjustment transfers) among those same consumers. Consumers associated with classes below the 45-degree line are profitable to avoid because, for these consumers, insurer costs exceed Marketplace premium plus risk adjustment revenue in expectation. The majority of drug classes are clustered tightly around the 45-degree line, showing that the payment system succeeds in neutralizing selection incentives for the majority of potential enrollees. However there are a number of significant outliers, such as the gonadotropin class of drugs (for infertility in women).

We focus in Figure 5 on the possibility of cream-skimming via the design of prescription drug benefits. We classify individuals according to whether they have a pharmacy claim for a drug within one of 220 standard therapeutic classes of medications. Each circle in the figure corresponds to a therapeutic class, grouping together all consumers who used a drug in the class. Marker sizes are proportional to the numbers of consumers associated with each class. The horizontal axis measures mean total spending among consumers utilizing a drug in the class, and the vertical axis measures the mean simulated revenue (actuarially fair premiums plus risk adjustment transfers) among those same consumers. Consumers associated with classes below the 45-degree line are profitable to avoid because, for these consumers, insurer costs exceed Marketplace premium plus risk adjustment revenue in expectation.

In Figure 5, the majority of drug classes are clustered tightly around the 45-degree line. This pattern implies that the payment system neutralizes the screening incentives for the majority of potential enrollees. For many drug classes that would predict costs several times in excess of premiums, such as anticoagulants (blood thinners), costs do not correlate with unprofitability net of the risk adjustment payment. This suggests that the Marketplace risk adjustment is succeeding in protecting consumers whose prescription drug use would otherwise flag them as unprofitable to insure.

However, there are a small number of significant outliers, such as the gonadotropin antagonist class (for infertility in women) far off the diagonal. Geruso, Layton, and Prinz (2016) analyze the universe of state-level Marketplace formularies for 2015 and show that insurers indeed design formularies to be differentially unattractive to the groups that deviate far below the 45-degree line. Within a plan, drug classes used by less-profitable consumers appear higher on the formulary tier structure, implying higher out-of-pocket costs by potentially thousands of dollars per year and/or significant nonprice hurdles, including prior authorization. Even less-expensive and generic drugs that are associated with expensive patients are assigned to high cost-sharing tiers or are left off formularies altogether. Other prior studies have provided similar evidence of insurers responding to imperfect risk adjustment via formulary design in Medicare Part D (Carey 2017) and via hospital network design in the Massachusetts “Connector” marketplace (Shepard 2016), which was set up before the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

Aside from the tendency of insurers to react to the exploitable errors in any risk adjustment system, risk adjustment faces several challenges due to the need to construct the risk-score based on observable signals of expected costs. For example, risk-adjusted payments to Medicare Advantage plans are ultimately based on diagnoses recorded on health insurance claims. In Traditional Medicare, on the other hand, diagnoses play no role in many payments, such as payments for outpatient physician services. This means physicians face relatively weak incentives to document diagnoses in Traditional Medicare claims, regardless of whether such diagnoses are recorded in the physician’s notes and patient’s medical records. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that if an individual enrolls in Medicare Advantage, the doctors with whom Medicare Advantage plans contract typically record more, and more severe, diagnoses. This leads to patient risk scores that are on average 6–7 percent higher than the score the same patient would generate in Traditional Medicare (Geruso and Layton 2015). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services acknowledges the coding differences, and over time has implemented increasingly large (but likely still too small) deflation factors to risk scores reported by Medicare Advantage plans.

The fact that diagnosis codes (or risk-adjustment variables more generally) are not fixed characteristics of consumers also leads to an efficiency problem in terms of how intensely health care services are provided. In principle, risk adjustment aims at reimbursing plans for who they enroll, rather than what the plans do. This would align the insurer, who is the residual claimant on capitation funds not paid out to providers, with the policymaker’s goal of constraining the growth of health care spending. However, Geruso and McGuire (2016) show that risk adjustment in the state-level Marketplaces significantly reimburses plans on the margin for actual care given. Intuitively, this occurs because the recorded diagnoses only arise endogenously via an interaction with a service provider, so risk scores are implicitly tied to utilization, rather than fixed characteristics of consumers. Across major diagnostic categories of services, insurers are reimbursed for services provided between 8 cents on the dollar and 82 cents on the dollar by the Marketplace risk adjustment scheme.

In markets without a public option, such as the state-level Marketplaces, an additional challenge arises: It is not clear what to use as the “baseline” plan when calibrating the relationship between costs and diagnoses. Einav, Finkelstein, Kluender, and Schrimpf (2016) offer evidence that conventional risk-adjustment policies cannot perfectly adjust for expected costs in plans with different coverage, implying that at least some cream-skimming incentives will always remain. The Marketplaces include plans with dramatically different cost structures, from low-cost Medicaid-like plans to generous wide-network “Cadillac” plans. However, the current risk adjustment system used in the Marketplaces treats all health insurance plans equally, with all plan risk adjustment transfers based on the average premium in the market, and with only minor modifications for a plan’s actuarial value. Layton, Montz, and Shepard (2017) show analytically that this equal treatment has potentially distortionary consequences, with the choice of the benchmark plan determining the extent of the transfer from low-cost plans to high-cost plans. How to deal with this issue remains a key area for future research.

A final complication relates to consumers’ outside option. Because risk adjustment forces low-premium advantageously selected plans to transfer money to high-premium adversely selected plans, it likely results in raising the premiums of the lowest-price plans. This results in more people enrolling in the higher-cost, more comprehensive plans, but it may also force marginal enrollees out of the market (Newhouse forthcoming), implying that risk adjustment may need to be accompanied by significant premium subsidies and/or penalties on the insurance/uninsurance margin if it is to be successful in these settings.

The substantial challenges implicit in designing the optimal risk adjustment system suggest important avenues for future theoretical and empirical work. Despite these challenges, conventional risk adjustment is the best tool we have to address selection across plans in competitive health insurance markets, hence its near-universal adoption in individual health insurance markets.

Contract Regulation

Almost all insurance markets feature extensive regulations on the contracts that insurers may offer. In Medicare Advantage, private plans must offer at least the standard set of benefits provided under Traditional Medicare. In the state-level health insurance Marketplaces, plans are required to pay for at least 60 percent of the health care costs of an average patient, to meet network adequacy mandates, and to comply with Essential Health Benefits (EHB) rules, which lay out minimal coverage requirements for services including maternity and newborn care, mental health and substance use disorder services, prescription drugs, and more. Services in these categories must be covered at least as well as they are covered in a “benchmark” plan chosen in each state. The variations in state benchmarks for Essential Health Benefits are in fact reflected in contract design differences across states (Andersen forthcoming).

These types of benefit regulations can be understood as a last line of defense against the endogenous contract distortions. As discussed above, if adverse selection is not adequately counteracted by risk adjustment, then the equilibrium set of contracts could be quite different from the efficient set of contracts, and in such a situation, restraining the equilibrium set of contracts could potentially improve welfare. The potential gains from such provisions can only be understood in an endogenous contracts framework.

However, these types of benefit regulations may also produce unintended consequences. For example, while Andersen (forthcoming) finds that the Essential Health Benefits regulations result in more drugs being covered in the formularies of Marketplace plans, the additional covered drugs are much more likely to be subject to utilization management restrictions, which have the effect of limiting access in practice (Simon, Tennyson, and Hudman 2009). This finding illustrates a key problem with using contract regulations to combat selection problems: it is very difficult for regulators to design rules that limit all possible dimensions of the health care interaction.

Another major tradeoff when using this type of regulatory mechanism is that minimum coverage requirements can lead some consumers who would like to purchase less-generous coverage to go uninsured (Finkelstein 2004). Even if uninsurance can be removed from the choice set with some combination of penalties and mandates, minimum coverage can in principle induce a death spiral for other plans in the market: specifically, as more healthy consumers are required to purchase a medium coverage contract, the price of that medium coverage contract drops, inducing some (relatively healthy) consumers who would have chosen a high coverage contract to inefficiently move to the less-generous minimum coverage (Azevedo and Gottlieb 2017).

A final potential downside to contract regulations is that even if all dimensions of the plan are observable and enforceable, it is difficult for a regulator to know the efficient level of coverage for each particular service. Determining optimal coverage involves a complex optimization problem that incorporates many difficult-to-estimate parameters such as consumer elasticities of demand and insurer and provider market power. Regulations could require insurers to provide too much of some benefits from the standpoint of social welfare. Additionally, the presence of this type of regulation can lead to political economy problems where interest groups lobby the government to require coverage of the services they use or provide, leading to a set of regulations that reflect political influence rather than social efficiency.

Overall, while contract restrictions may play a role in plugging various holes left by imperfectly implemented risk adjustment, such policies have clear limits. Our summary reading of the evidence is that when attempting to limit selection problems in markets, there is no good substitute for a payment system that leverages market forces and addresses insurers’ financial incentives with respect to selection, rather than tries to force insurers to act against their own financial interests.

Conclusion

Publicly financed health insurance programs in the United States have in recent years come to rely more heavily on private insurance markets where individuals choose from a variety of plans designed by private sector insurers. This change is especially apparent in the growth of the Medicare Advantage program and the creation of the state-level health insurance Marketplaces by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The health insurance contracts actually offered to individuals by private insurers clearly reflect the reality that selection incentives matter. Although the consequences of adverse selection can be limited by risk adjustment, premium rating regulations, mandates/subsidies, and contract regulations, there is still a great deal that we don’t know about what optimal plan payment policies look like. Glazer and McGuire (2000, 2002) took early steps towards developing a theory of optimal risk adjustment, but both the markets in which these policies are used and the technology of risk adjustment itself are much more complex than was originally anticipated. For example, we now know that plans with heterogeneous cost structures imperfectly compete alongside each other in the same market. Additionally, risk scores appear to be highly endogenous to the plan a consumer chooses and the contract an insurer designs. Thus, even with policies to limit selection in place, these issues are ongoing. It seems to be an inescapable fact, at least at the current state of knowledge, that risk adjustment and other plan payment policies are unable to capture all relevant dimensions of consumers’ expected health care spending.

These complications imply that new theories of optimal (second-best) payment policies need to be developed, along with complementary regulations. Some of this research will focus on alternative methods of calculating risk adjustment payments, along with new structures for subsidies or mandates. But it is also important to expand the range of optimal payment policies to be considered. For example, one approach might consider reinsurance programs that compensate plans based on certain key dimensions of after-the-fact realized costs, but it will be important to focus on dimensions that are least susceptible to moral hazard concerns (Geruso and McGuire 2016; Layton, McGuire, and van Kleef 2016). Another policy alternative might seek to compensate health insurance plans based on certain features of the contracts themselves, rather than the imperfect selection signals generated by risk scores. The long-term success of policies that rely on consumer choice in markets for subsidized but privately provided health insurance depends on research that improves our understanding of how to address the selection issues outlined here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Keith Ericson, Jon Gruber, Tom McGuire, Joe Newhouse, Dean Spears, and Steve Trejo for reviewing an earlier draft of this essay. We thank Austin Bean for excellent research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH094290), the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG032952), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin), and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other funder.

Footnotes

For supplementary materials such as appendices, datasets, and author disclosure statements, see the article page at https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.4.23

Limited networks and restrictive formularies could in principle be a socially efficient reaction to consumer preferences for lower-cost coverage or the outcome of a bargaining game between insurers and hospitals/drug manufacturers (Ho and Lee 2016; Duggan and Scott Morton 2010). However, as noted in the text, such patterns are also consistent with adverse selection.

There exist other solutions to the reclassification risk problem, such as long-run insurance contracts, though these solutions face significant barriers to implementation, especially in the presence of the significant choice frictions and behavioral biases described in the other articles in this symposium. See Handel, Hendel, and Whinston (2017) for a detailed treatment of these alternative solutions.

There is a subtle but important additional efficiency cost of premium rating restrictions. If consumers have heterogeneous preferences over insurance plans, a point on the marginal cost curve represents the average cost over a set of heterogeneous consumers who place the same value on insurance, and no uniform price can efficiently sort all consumers (Glazer and McGuire 2011; Bundorf, Levin, and Mahoney 2012; Geruso forthcoming). This feature is unique to selection markets, where the specific consumer who purchases the product determines both its value and its production cost.

This diagram is appropriate for considering extensive margin selection from uninsurance to insurance, or for considering the Medicare Advantage/Traditional Medicare choice margin, where selection alters only the price of Medicare Advantage. In markets where the price of both options is endogenous to their risk pools, the equilibrium is more complex (Weyl and Veiga 2016; Layton 2016; Handel, Hendel, and Whinston 2015).

It is important to note, however, that these implications for efficiency are based on the static, one-period setting, and the efficiency consequences of reinsurance or differentially large subsidies for the healthy may be reversed, or at least weakened, when considering long-run dynamic risk such as the risk of acquiring a chronic disease.

In the online Appendix available with this paper at http://e-jep.org, we offer an example in which risk adjustment could make the allocation worse in a competitive equilibrium.

Risk adjustment does, nonetheless, break the connection between the enrollee risk pool and the plan’s average costs. In this way it stabilizes the market, easing insurer uncertainty about net costs, and reducing the probability of prices evolving uncertainly in a setting like the Marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act in which the demand and cost curves (determining the competitive equilibrium) were not common knowledge.

The result is complicated by the observation that this pattern appears to have reversed course in 2006, with switcher costs conditional on risk scores returning to their 2001 levels (Newhouse et al. 2015). We note that the introduction of Part D and increases to Medicare Advantage benchmarks that occurred in 2006 represent potential confounders for this time period due to their potential independent effects on the composition of the Medicare Advantage risk pool.

These large employer claims data are aggregated by Truven Health and cover plan years 2012 and 2013. See the online Data Appendix for full details.

Contributor Information

Michael Geruso, University of Texas, Austin, Texas; Faculty Research Fellows, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Timothy J. Layton, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.; Faculty Research Fellows, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts

References

- Aizawa Naoki, and Kim You Suk. 2015. “Advertising and Risk Selection in Health Insurance Markets.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US) Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015–101. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen Martin. Forthcoming. “Constraints on Formulary Design under the Affordable Care Act.” Health Economics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews Michelle. 2015. “New Health Plans Offer Discounts for Diabetes Care.” Kaiser Health News, November 17. http://khn.org/news/new-health-plans-offer-discounts-for-diabetes-care. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Azevedo Eduardo, and Gottlieb Daniel. 2017. “Perfect Competition in Markets with Adverse Selection.” Econometrica 85(1): 67–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Noam, Bello Jason, Coe Erica, and Lamb Jessica. 2015. “Hospital Networks: Evolution of the Configurations on the 2015 Exchanges.” McKinsey & Company, April. http://healthcare.mckinsey.com/2015-hospital-networks. [Google Scholar]

- Breyer Friedrich, Bundorf M. Kate, and Pauly Mark V.. 2011. “Health Care Spending Risk, Health Insurance, and Payment to Health Plans.” In Handbook of Health Economics, edited by Pauly Mark V., Mcguire Thomas G., and Barros Pedro P., 691–762. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Brown Jason, Duggan Mark, Kuziemko Ilyana, and Woolston William. 2014. “How Does Risk Selection Respond to Risk Adjustment? New Evidence from the Medicare Advantage Program.” American Economic Review 104(10): 3335–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Buchmueller Thomas, and DiNardo John. 2002. “Did Community Rating Induce an Adverse Selection Death Spiral? Evidence from New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut.” American Economic Review 92(1): 280–94. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Bundorf M. Kate, Levin Jonathan, and Mahoney Neale. 2012. “Pricing and Welfare in Health Plan Choice.” American Economic Review 102(7): 3214–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral Marika, Geruso Michael, and Mahoney Neale. 2014. “Does Privatized Health Insurance Benefit Patients or Producers? Evidence from Medicare Advantage.” NBER Working Paper 20470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Carey Colleen. 2017. “Technological Change and Risk Adjustment: Benefit Design Incentives in Medicare Part D.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9(1): 38–73. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Cochrane John H. 1995. “Time-Consistent Health Insurance.” Journal of Political Economy 103(3): 445–73. [Google Scholar]

- Curto Vilsa, Einav Liran, Levin Jonathan, and Bhattacharya Jay. 2014. “Can Health Insurance Competition Work? Evidence from Medicare Advantage.” NBER Working Paper 20818. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Duggan Mark, and Morton Fiona Scott. 2010. “The Effect of Medicare Part D on Pharmaceutical Prices and Utilization.” American Economic Review 100(1): 590–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Einav Liran, and Finkelstein Amy. 2011. “Selection in Insurance Markets: Theory and Empirics in Pictures.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(1): 115–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Einav Liran, Finkelstein Amy, and Cullen Mark R.. 2010. “Estimating Welfare in Insurance Markets Using Variation in Prices.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(3): 877–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Einav Liran, Finkelstein Amy, Kluender Raymond, and Schrimpf Paul. 2016. “Beyond Statistics: The Economic Content of Risk Scores.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(2): 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Ericson Keith M. Marzilli, and Starc Amanda. 2015. “Pricing Regulation and Imperfect Competition on the Massachusetts Health Insurance Exchange.” Review of Economics and Statistics 97(3): 667–82. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Finkelstein Amy. 2004. “Minimum Standards, Insurance Regulation and Adverse Selection: Evidence from the Medigap Market.” Journal of Public Economics 88(12): 2515–47. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Frank Richard G., Glazer Jacob, and McGuire Thomas G.. 2000. “Measuring Adverse Selection in Managed Health Care.” Journal of Health Economics 19(6): 829–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geruso Michael. Forthcoming. “Demand Heterogeneity in Insurance Markets: Implications for Equity and Efficiency.” Quantitative Economics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geruso Michael, and Layton Timothy. 2015. “Upcoding: Evidence from Medicare on Squishy Risk Adjustment.” NBER Working Paper 21222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geruso Michael, Layton Timothy J., and Prinz Daniel. 2016. “Screening in Contract Design: Evidence from the ACA Health Insurance Exchanges.” NBER Working Paper 22832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Geruso Michael, and McGuire Thomas G.. 2016. “Tradeoffs in the Design of Health Plan Payment Systems: Fit, Power and Balance.” Journal of Health Economics 47: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Glazer Jacob, and McGuire Thomas G.. 2000. “Optimal Risk Adjustment in Markets with Adverse Selection: An Application to Managed Care.” American Economic Review 90(4): 1055–71. [Google Scholar]

- ▶Glazer Jacob, and McGuire Thomas G.. 2002. “Multiple Payers, Commonality and Free-Riding in Health Care: Medicare and Private Payers.” Journal of Health Economics 21(6): 1049–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Glazer Jacob, and McGuire Thomas G.. 2011. “Gold and Silver Health Plans: Accommodating Demand Heterogeneity in Managed Competition.” Journal of Health Economics 30(5): 1011–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Hackmann Martin B., Kolstad Jonathan T., and Kowalski Amanda E.. 2015. “Adverse Selection and an Individual Mandate: When Theory Meets Practice.” American Economic Review 105(3): 1030–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Handel Benjamin R. 2013. “Adverse Selection and Inertia in Health Insurance Markets: When Nudging Hurts.” American Economic Review 103(7): 2643–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ▶Handel Ben, Hendel Igal, and Whinston Michael D.. 2015. “Equilibria in Health Exchanges: Adverse Selection versus Reclassification Risk.” Econometrica 83(4): 1261–1313. [Google Scholar]