Abstract

Background

Parental psychosocial health can have a significant effect on the parent‐child relationship, with consequences for the later psychological health of the child. Parenting programmes have been shown to have an impact on the emotional and behavioural adjustment of children, but there have been no reviews to date of their impact on parental psychosocial wellbeing.

Objectives

To address whether group‐based parenting programmes are effective in improving parental psychosocial wellbeing (for example, anxiety, depression, guilt, confidence).

Search methods

We searched the following databases on 5 December 2011: CENTRAL (2011, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1950 to November 2011), EMBASE (1980 to week 48, 2011), BIOSIS (1970 to 2 December 2011), CINAHL (1982 to November 2011), PsycINFO (1970 to November week 5, 2011), ERIC (1966 to November 2011), Sociological Abstracts (1952 to November 2011), Social Science Citation Index (1970 to 2 December 2011), metaRegister of Controlled Trials (5 December 2011), NSPCC Library (5 December 2011). We searched ASSIA (1980 to current) on 10 November 2012 and the National Research Register was last searched in 2005.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials that compared a group‐based parenting programme with a control condition and used at least one standardised measure of parental psychosocial health. Control conditions could be waiting‐list, no treatment, treatment as usual or a placebo.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors extracted data independently and assessed the risk of bias in each study. We examined the studies for any information on adverse effects. We contacted authors where information was missing from trial reports. We standardised the treatment effect for each outcome in each study by dividing the mean difference in post‐intervention scores between the intervention and control groups by the pooled standard deviation.

Main results

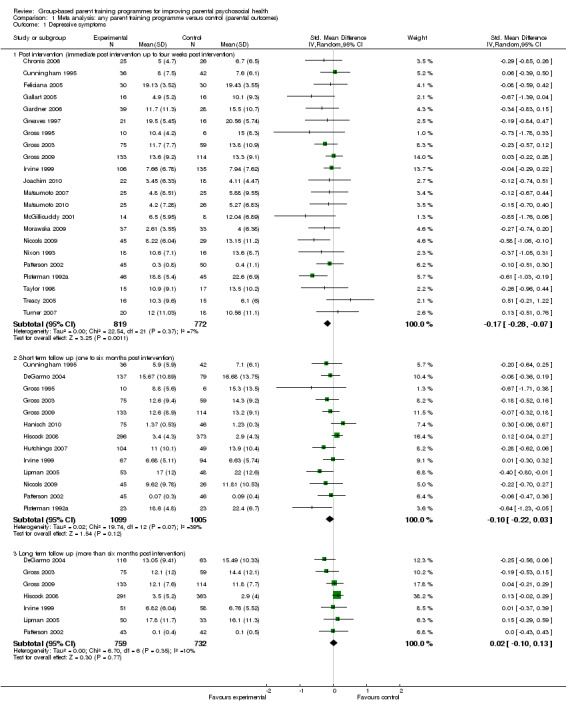

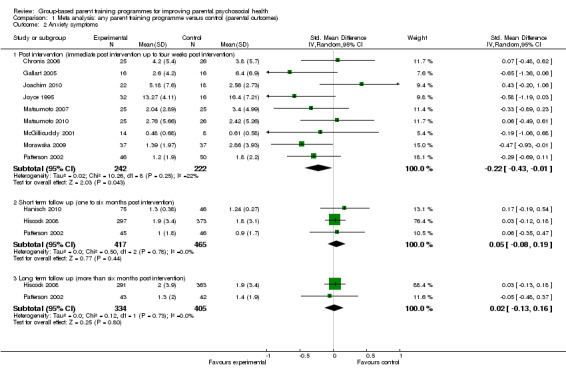

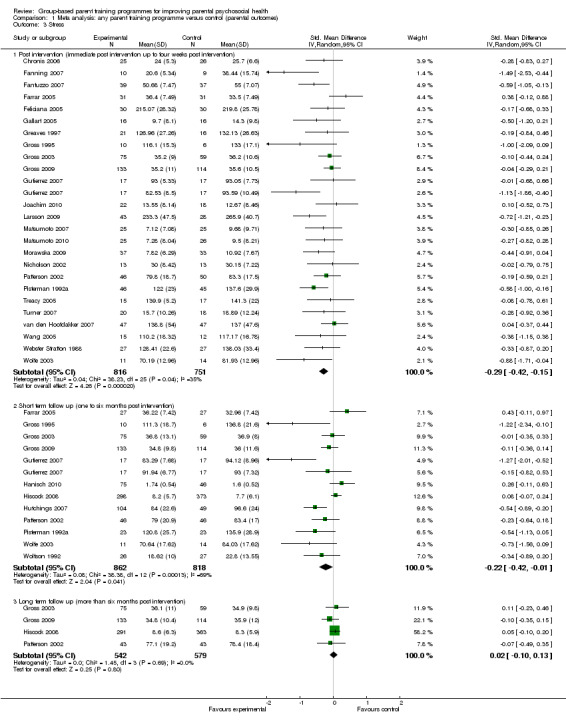

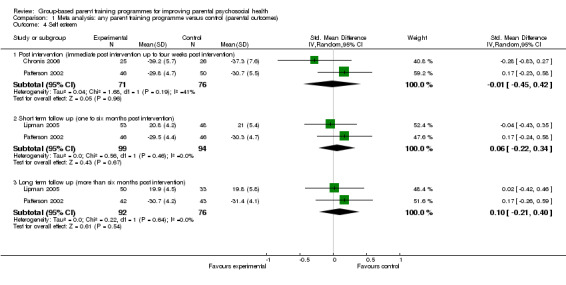

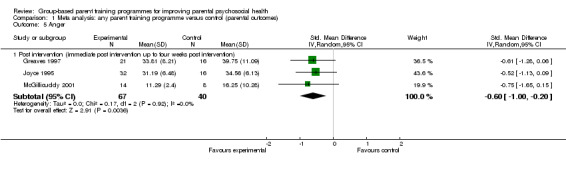

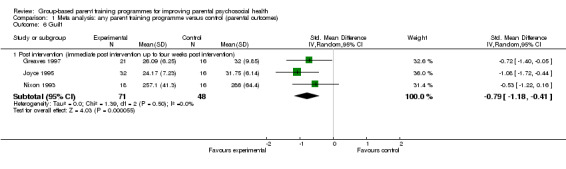

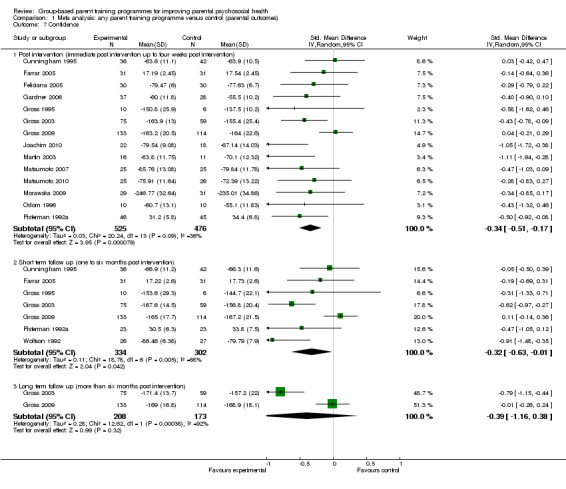

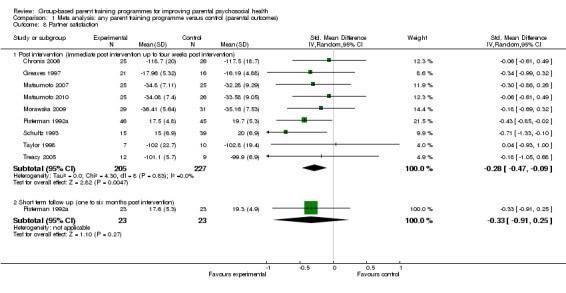

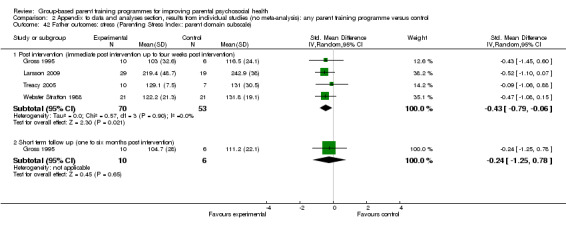

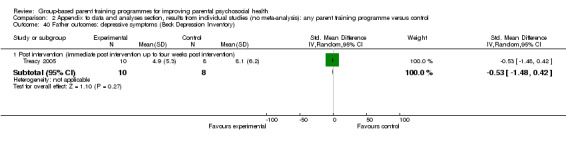

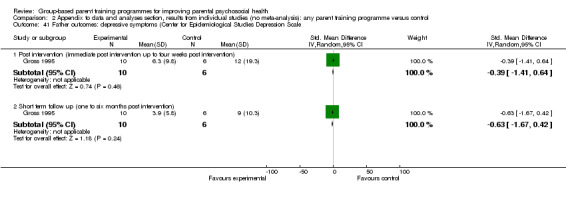

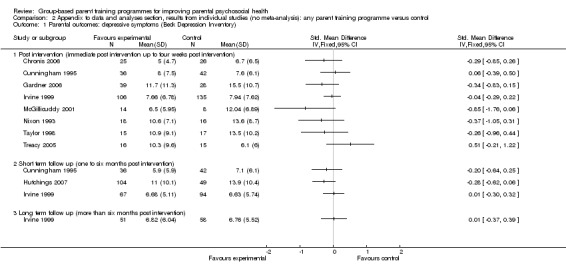

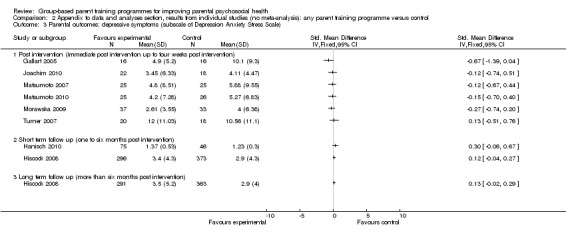

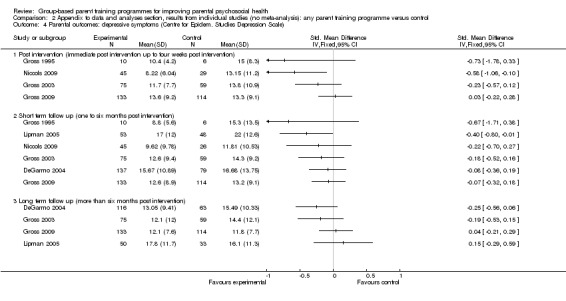

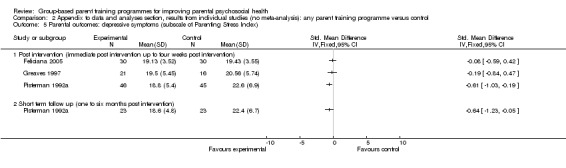

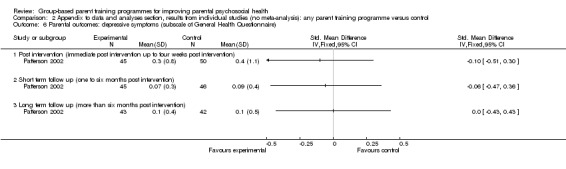

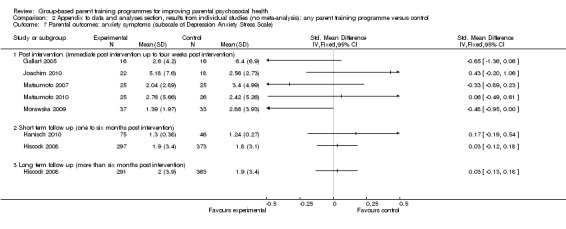

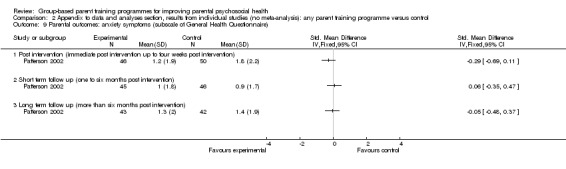

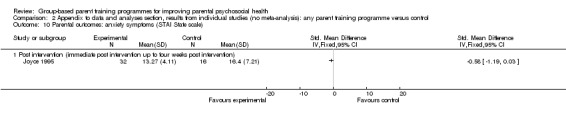

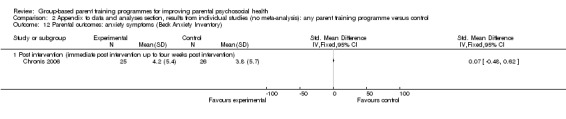

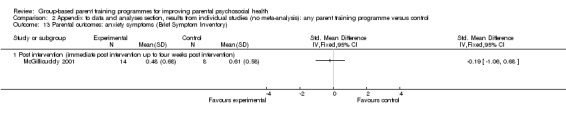

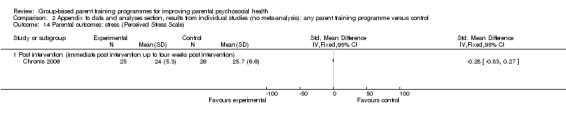

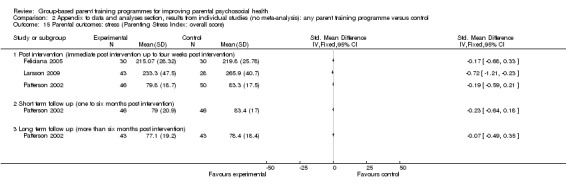

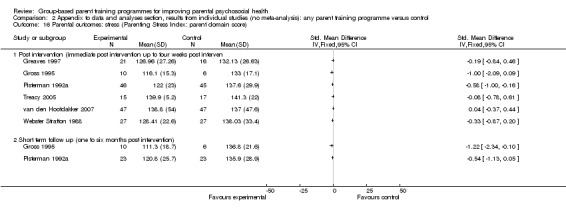

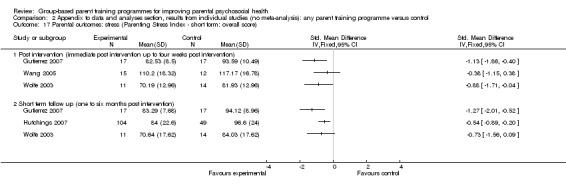

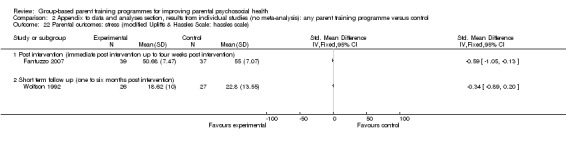

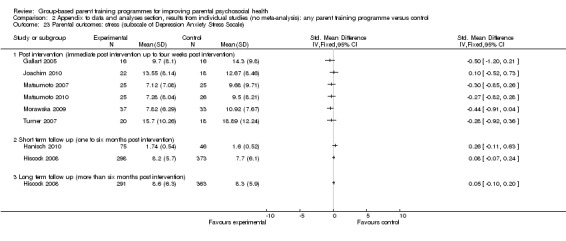

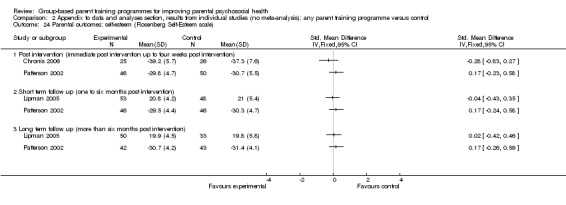

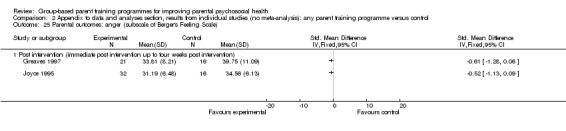

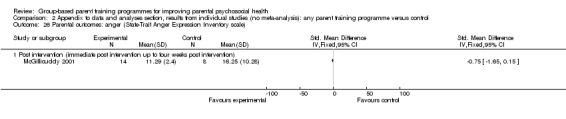

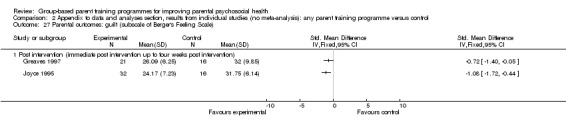

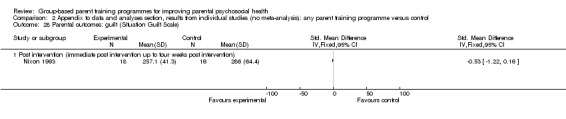

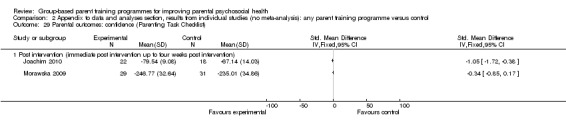

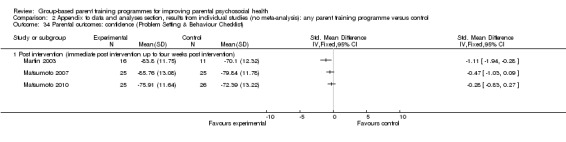

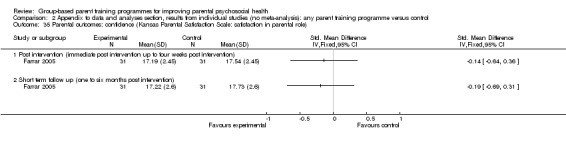

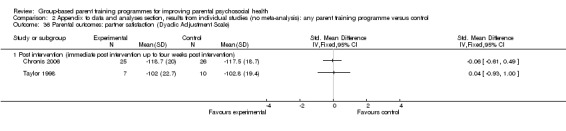

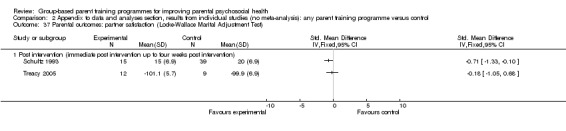

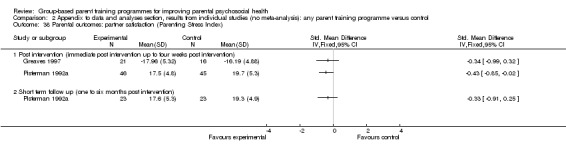

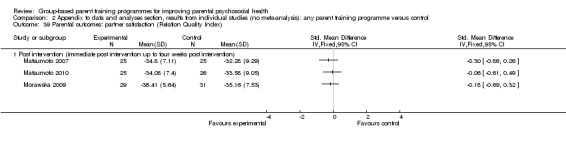

We included 48 studies that involved 4937 participants and covered three types of programme: behavioural, cognitive‐behavioural and multimodal. Overall, we found that group‐based parenting programmes led to statistically significant short‐term improvements in depression (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.28 to ‐0.07), anxiety (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.43 to ‐0.01), stress (SMD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.15), anger (SMD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.20), guilt (SMD ‐0.79, 95% CI ‐1.18 to ‐0.41), confidence (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.51 to ‐0.17) and satisfaction with the partner relationship (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.09). However, only stress and confidence continued to be statistically significant at six month follow‐up, and none were significant at one year. There was no evidence of any effect on self‐esteem (SMD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.42). None of the trials reported on aggression or adverse effects.

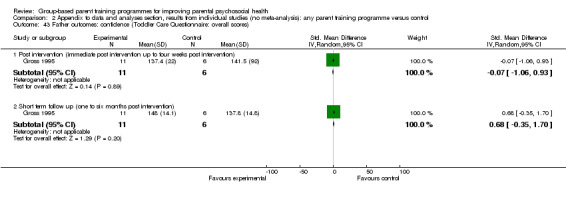

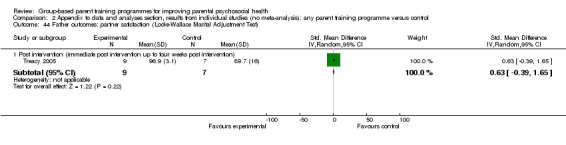

The limited data that explicitly focused on outcomes for fathers showed a statistically significant short‐term improvement in paternal stress (SMD ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.79 to ‐0.06). We were unable to combine data for other outcomes and individual study results were inconclusive in terms of any effect on depressive symptoms, confidence or partner satisfaction.

Authors' conclusions

The findings of this review support the use of parenting programmes to improve the short‐term psychosocial wellbeing of parents. Further input may be required to ensure that these results are maintained. More research is needed that explicitly addresses the benefits for fathers, and that examines the comparative effectiveness of different types of programme along with the mechanisms by which such programmes bring about improvements in parental psychosocial functioning.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Anxiety, Anxiety/therapy, Depression, Depression/therapy, Maternal Behavior, Maternal Behavior/psychology, Maternal Welfare, Mother‐Child Relations, Parenting, Parenting/psychology, Parents, Parents/education, Parents/psychology, Paternal Behavior, Paternal Behavior/psychology, Program Evaluation, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Self Concept

Plain language summary

Parent training for improving parental psychosocial health

Parental psychosocial health can have a significant effect on the parent‐child relationship, with consequences for the later psychological health of the child. Some parenting programmes aim to improve aspects of parental wellbeing and this review specifically looked at whether group‐based parenting programmes are effective in improving any aspects of parental psychosocial health (for example, anxiety, depression, guilt, confidence).

We searched electronic databases for randomised controlled trials in which participants had been allocated to an experimental or a control group, and which reported results from at least one scientifically standardised measure of parental psychosocial health.

We included a total of 48 studies that involved 4937 participants and covered three types of programme: behavioural, cognitive‐behavioural and multimodal. Overall, the results suggested statistically significant improvements in the short‐term for parental depression, anxiety, stress, anger, guilt, confidence and satisfaction with the partner relationship. However, only stress and confidence continued to be statistically significant at six month follow‐up, and none were significant at one year. There was no evidence of effectiveness for self‐esteem at any time point. None of the studies reported aggression or adverse outcomes.

Only four studies reported the outcomes for fathers separately. These limited data showed a statistically significant short‐term improvement in paternal stress but did not show whether the parenting programmes were helpful in terms of improving depressive symptoms, confidence or partner satisfaction.

This review shows evidence of the short‐term benefits of parenting programmes on depression, anxiety, stress, anger, guilt, confidence and satisfaction with the partner relationship. The findings suggest that further input may be needed to support parents to maintain these benefits. However, more research is needed that explicitly addresses the benefits for fathers, and that provides evidence of the comparative effectiveness of different types of programme and identifies the mechanisms involved in bringing about change.

Background

Description of the condition

Parental psychosocial functioning is a significant factor influencing a range of aspects of children's development and wellbeing (see below). It consists of a wide range of components but those most frequently researched in terms of their impact on the wellbeing of children include parental mental health (that is depression and anxiety, parental confidence and parental conflict). The available evidence relates to infancy and toddlerhood, and to mid‐childhood and adolescence.

1. Infant and toddlerhood

The postnatal period has been identified as being of particular importance in terms of the infant's need for affectively attuned parenting (Jaffe 2001) and for parental reflective functioning (Fonagy 1997), both of which are now thought to be central to the infant's capacity to develop a secure attachment to the primary caregiver (Van IJzendoorn 1995; Grienenberger 2005). Parental psychosocial functioning can impact on the parent's capacity to provide this type of parenting. For example, one study found that depressed mothers were less sensitively attuned to their infants, less affirming and more negating of infant experience compared with parents not experiencing postnatal depression (Murray 1992); and that these infants had poorer cognitive outcomes at 18 months (Murray 1996), performed less well on object concept tasks, were more insecurely attached to their mothers and showed more behavioural difficulties (Murray 1996). Boys of postnatally depressed mothers may also score lower on standardised tests of intellectual attainment (Sharp 1995). A clinical diagnosis of postnatal depression is associated with a fourfold increase in risk of psychiatric diagnosis at age 11 years (Pawlby 2008). Recent research has also identified that the impact of postnatal depression on insecure child attachment may be moderated by maternal attachment state of mind (McMahon 2006). The chronicity of the depression appears to be a significant predictor, with depression lasting throughout the first 12 months being associated with poorer cognitive and psychomotor development for both boys and girls compared with no evidence of impact for brief periods of depression (Cornish 2008).

Recent research shows that paternal postnatal depression can have an effect that is similar in magnitude to that of maternal depression. Ramchandani 2008 showed that boys of fathers who were depressed during the postnatal period had an increased risk of conduct problems at age 3.5 years, and that boys of fathers who were depressed during both the prenatal and postnatal periods had the highest risks of subsequent psychopathology at 3.5 years and psychiatric diagnosis at seven years of age (Ramchandani 2008).

Neurodevelopmental research suggests that postnatal depression impacts the child's developing neurological system (Schore 2005). For example, one study found that infants of depressed mothers exhibited reduced left frontal electroencephalogram (EEG) activity (Dawson 1997). Parent‐infant interaction can also impact on the infant's stress regulatory system, one study showing that exposure to stress during the early postnatal period that was not mediated by sensitive parental caregiving had an impact on the infant's hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenocorticol (HPA) system (Gunnar 1994), which plays a major role in both the production and regulation of glucocorticoid cortisol in response to such stress.

Maternal anxiety during the postnatal period is also associated with poorer outcomes. For example, Beebe 2011 found that maternal anxiety biased the interaction toward interactive contingencies that were both heightened (vigilant) in some modalities and lowered (withdrawn) in others, as opposed to being in the 'mid‐range', which has been identified as optimal for later development, including secure attachment (Beebe 2011).

2. Mid‐childhood and adolescence

There is also evidence to show a significant impact of parental psychosocial functioning on older children. A review of longitudinal studies found that by the age of 20 years, children of affectively ill parents have a 40% chance of experiencing an episode of major depression and are more likely to exhibit general difficulties in functioning, including increased guilt and interpersonal difficulties such as problems with attachment (Beardslee 1998). More recently, maternal psychological distress has been identified as being a risk factor for conduct and emotional problems. Parry‐Langdon 2008 found that higher scores on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12) were an independent risk factor for conduct disorder (odds ratio (OR) 2.2) and for child emotional problems (OR 2.2). This OR increased to 3.5 for both emotional and behavioural problems where maternal scores on the GHQ‐12 were initially low and then subsequently increased.

One longitudinal study that focused on parental conflict found that adolescents' perceptions of typical interparental conflict directly predicted increases in depressive symptoms (particularly for girls) and aggressive behaviours (particularly for boys) over a period of a year, and that this was not mediated by parental style or quality (McGuinn 2004). This study found a significant impact on the wellbeing of adolescents who witnessed even 'normative' marital discord. Another aspect of parental psychosocial functioning is parental confidence, which has been shown to be strongly associated with parent‐child interactions that are characterised by inconsistency, guilt, detachment and anxiety (Martin 2000). One meta‐analysis also found that paternal depression was significantly related to internalising and externalising psychopathology in children, and to father‐child conflict (Kane 2004).

It is suggested that the mechanism linking parental psychosocial functioning and child outcomes is the impact of such functioning on parenting behaviours, and Waylen 2010 found that worsening parental mental health was associated with reduced parenting capacity. Similarly, Wilson 2010 found a significant deleterious impact of paternal depression on both positive and negative parenting behaviours. One longitudinal study also suggested a more complex pathway in which parental depressive symptoms were associated 12 months later with increased insecurity in adult close relationships and interparental conflict (Shelton 2008). This study showed that such conflict had a negative impact on children's appraisals of parents, which was in turn was associated with children's internalising and externalising problems (Shelton 2008).

Overall, this evidence suggests that parental psychosocial functioning can impact on the parents' capacity to provide affectively attuned interaction during infancy and toddlerhood, and an impact on older children as a result of the consequences of compromised parental psychosocial functioning for parenting behaviours and marital adjustment.There is, therefore, considerable potential for interventions aimed at promoting the psychosocial wellbeing of parents to reduce the disruption to the child's emotional, educational and social adjustment, and thereby to promote the mental health of future generations.

Description of the intervention

Parenting programmes are underpinned by a range of theoretical approaches (including behavioural, cognitive‐behavioural, family systems, Adlerian) and can involve the use of a range of techniques in their delivery including discussion, role play, watching video vignettes and homework. Behavioural parenting programmes are based on social learning principles and teach parents how to use a range of basic behavioural strategies for managing children’s behaviour, and some of these programmes involve the use of videotape modelling. Cognitive parenting programmes are aimed at helping parents to identify and change distorted patterns of belief or thought that may be influencing their behaviour, and cognitive‐behavioural programmes combine elements of both types of strategy. Other types of programme often combine some of these strategies. For example, Adlerian programmes focus on the use of 'natural and logical consequences' and 'reflective listening' strategies.

Parenting programmes are typically offered to parents over the course of eight to 12 weeks, for about one to two hours each week. They can be delivered on a one‐to‐one basis or to groups of parents and are provided in a number of settings, ranging from hospital or social work clinics to community‐based settings such as general practitioner (GP) surgeries, schools and churches. They typically involve the use of a manualised and standardised programme or curriculum, and are aimed at increasing the knowledge, skills and understanding of parents.

Recent evidence shows that parenting programmes can improve the emotional and behavioural adjustment of children under three years (Barlow 2010) and of children aged three to 10 years with conduct and behaviour problems (Dretze 2005). A review of studies focused on teenage parents found that parenting programmes improved parental responsiveness to the child and parent‐child interaction (Barlow 2011). Reviews of qualitative evidence point to a range of benefits of taking part in a group with other parents (Kane 2003).

How the intervention might work

The mechanism by which parenting programmes may impact on parental psychosocial wellbeing is thought to be twofold. Firstly, parenting programmes are, on the whole, strengths‐based, and are aimed at enhancing parental capacity and changing parenting attitudes and practices in a non‐judgemental and supportive manner, with the overall aim of improving child emotional and behavioural adjustment. For example, Patterson’s coercion theory (Patterson 1992) demonstrates the way in which parents are increasingly disempowered as a result of a process of escalation in which parents who 'give in' to child demands are increasingly likely to need more coercive strategies on the next occasion. The process in which problems escalate and parents feel increasingly disempowered may explain in part why parents experience stress and depression directly related to the parenting role.The potential impact of parenting programmes on parental psychosocial functioning may be due to the way in which such programmes help parents to address significant issues in terms of their child's wellbeing, and increase their skills and capacity to support their child's physical and emotional development (for example, Dretze 2005; Barlow 2011).

Secondly, many parenting programmes, particularly those that are underpinned by a cognitive or cognitive‐behavioural approach, may also provide parents with strategies that are directly aimed at improving parental psychological functioning. Any improvements that occur may be a result of the parents' application of such strategies to themselves instead of, or in addition to, the use of strategies focused on improving child behaviour.

Research also suggests that parenting programmes can improve other aspects of parental psychosocial functioning such as marital relations and parenting stress (Todres 1993). Factors such as marital conflict and parental stress can have a direct impact on children, in addition to being mediators of other parental problems (for example, poor mental health). Improvements in marital conflict and parental stress will, as such, have beneficial consequences in terms of children's later development.

Thus, although a number of studies have shown that parenting programmes can have an impact on aspects of maternal mental health and wellbeing, including reducing anxiety (Morawska 2009) and depression (Pisterman 1992a), it is not currently clear whether such improvements reflect the impact of strategies directly targeting parental mental health or whether they occur as an indirect result of the parent's improved ability to manage their children's behaviour and of improvements in family functioning more generally.

Therefore, although the causal mechanism is not entirely clear, parenting programmes appear to have considerable potential to impact one or more aspects of parental psychosocial functioning. It should be noted, however, that although parents who are experiencing anxiety and depression unrelated to the parenting role may also have a compromised ability to function as a parent, with consequences in terms of their children's wellbeing. The needs of such parents are not addressed by the current review, which does not include programmes provided to parents with clinical mental health or psychiatric problems.

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this review is to evaluate the effectiveness of group‐based parenting programmes in improving the psychosocial health of parents, by appraising and collating evidence from existing studies that have used rigorous methodological designs and a range of standardised outcome instruments. The results will inform the broader debate concerning the role and effectiveness of parenting programmes.

Objectives

To update an existing review examining the effectiveness of group‐based parenting programmes in improving parental psychosocial health (for example, anxiety, depressive symptoms, self‐esteem).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials in which participants had been randomly allocated to an experimental or a control group, the latter being a waiting‐list, no treatment, treatment as usual (normal service provision) or a placebo control group.

Quasi‐randomised controlled trials are defined as trials where allocation was done on the basis of a pseudo‐random sequence, for example, odd or even hospital number, date of birth or alternation (Higgins 2008).

We did not include studies comparing two different therapeutic modalities (that is, without a control group).

Types of participants

We included studies that targeted adult (rather than teenage) parents (including mothers, fathers, grandparents, foster parents, adoptive parents or guardians) from either population or clinical samples (that is, with or without child behavioural problems) with parental responsibility for the day‐to‐day care of children, and who were eligible to take part in a parent training programme aimed at helping them to address some aspect of parental functioning (for example, attitudes and behaviour).

We included studies of parenting programmes delivered to all parents, not just those at risk of poor psychosocial health and child behavioural problems. Although we are addressing the impact of parenting programmes on aspects of parental psychosocial functioning such as anxiety and depression, we excluded studies that explicitly targeted and thereby focused solely on parents with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder, for example, clinical depression. This reflects the fact that parenting programmes are primarily provided to address children's social, emotional and behavioural functioning, and although parents with clinical psychiatric conditions may benefit from a parenting programme, these would not typically be provided as the primary source of treatment. Parents with clinical psychiatric conditions should be the focus of a separate review.

We included studies of parents who had children with a disability if the intervention was aimed at supporting or changing parenting and the study also measured parental psychosocial health.

We excluded studies that focused solely on child outcomes, preparation of parents for parenthood or that were directed at pregnant or parenting teenagers (below the age of 20 years).

Types of interventions

We included parenting programmes meeting the following criteria:

group‐based format;

standardised or manualised programme;

any theoretical framework including behavioural, cognitive and cognitive‐behavioural (please see Description of the intervention);

developed largely with the intention of helping parents to manage children's behaviour and improve family functioning and relationships.

We excluded programmes:

provided to parents on an individual or self‐administered basis;

that involved direct work with children;

that involved other types of service provision, such as home visits;

in studies that included only measures of parental attitudes (for example, Parental Attitude Test) or of family functioning (for example, McMaster Family Assessment Device) because, although these may reflect the family's functioning as a group, they are not direct measures of parental psychosocial health.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Outcomes measured using standardised instruments including the measures detailed below.

Depressive symptoms

Parental depressive symptoms measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961) or similar standardised instrument.

Anxiety symptoms

Parental anxiety measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988) or similar standardised instrument.

Stress

Parental stress measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) (Abidin 1983) or similar standardised instrument.

Self‐esteem

Parental self‐esteem measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Rosenberg Self‐Esteem scale (RSE) (Rosenberg 1965) or similar standardised instrument.

Anger

Parental anger measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Brief Anger‐Aggression Questionnaire (BAAQ) (Maiuro 1987) or similar standardised instrument.

Aggression

Parental aggression measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Brief Anger‐Aggression Questionnaire (BAAQ) (Maiuro 1987) or similar standardised instrument.

Guilt

Parental guilt measured, for example, through improvement in scores on the Situation of Guilt Scale or similar (SGS) (Klass 1987) or similar standardised instrument.

Secondary outcomes

Confidence

Parental confidence measured through improvement in scores on the Parent Sense of Competence Scale (PSC) (Johnston 1989) or similar standardised instrument.

Partner satisfaction

Marital or partner satisfaction measured through improvement in scores on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) (Spanier 1976) or similar standardised instrument.

Adverse effects

Any adverse effects relating to parental psychosocial health including, for example, increase in tension between parents.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The previous version of this review was based on searches run in 2002. This update is based on searches run in 2008, 2010 and 2011. We added the metaRegister of Controlled Trials to search for completed and ongoing trials. We could not update the searches in SPECTR or the National Research Register because they had ceased to exist by 2008. Since the previous version of the review, Sociological Abstracts replaced Sociofile and PsycINFO replaced PsycLIT. During the update, ERIC and Sociological Abstracts moved to new search platforms and the original search strategies were adapted accordingly. All search strategies used for this update are reported in Appendix 1.

We searched the following electronic databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controled Trials (CENTRAL), part of the Cochrane Library (2011, Issue 4), last searched 5 December 2011.

MEDLINE (Ovid) 1950 to November 2011, last searched 5 December 2011.

EMBASE (Ovid) 1980 to 2011 Week 48, last searched 5 December 2011.

CINAHL (EBSCO) 1982 to current, last searched 5 December 2011.

BIOSIS 1970 to 2 December 2011, last searched 5 December 2011.

PsycINFO 1970 to week 5 November 2011, last searched 5 December 2011.

Sociological Abstracts (Proquest), 1952 to current, last searched 5 December 2011.

Sociological Abstracts (CSA), 1963 to current, last searched March 2010.

Social Science Citation Index, 1956 to 2 December 2011, last searched 5 December 2011.

ASSIA 1980 to current, last searched 10 November 2011.

ERIC (via www.eric.ed.gov), 1966 to current, last searched 7 December 2011.

ERIC (via OVID), 1966 to current, last searched March 2010.

Searching other resources

NSPCC library database (last searched 5 December 2011).

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (last searched 5 December 2011).

Reference lists of articles identified through database searches were examined for further relevant studies. We also examined bibliographies of systematic and non‐systematic review articles to identify relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the first published versions of this review (Barlow 2001; Barlow 2003), we identified titles and abstracts of studies through searches of electronic databases and reviewed the results to determine whether the studies that appeared relevant met the inclusion criteria. For the original review Esther Coren (EC) identified titles and abstracts and these were screened by EC and JB. Two review authors (EC and JB) independently assessed full copies of papers that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. We resolved uncertainties concerning the appropriateness of studies for inclusion in the review through consultation with a third review author, Sarah Stewart‐Brown (SS‐B). For the update of the review, Nadja Smailagic (NS) and Nick Huband (NH) carried out the eligibility assessments in consultation with JB and Cathy Bennett (CB). JB had overall responsibility for the inclusion or exclusion of studies in this review.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data independently (JB and EC or SS‐B; later NS and NH) using a data extraction form and entered the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan) (RevMan 2011). Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted trial investigators to supply missing information.

Some of the standardised measures used in the studies included in this review are reversed, such that a high score is considered to represent an improvement in outcome. We investigated whether the study investigators had used any methods to correct for this, for example, by reversing the direction of the scale by multiplying the mean values by ‐1 or by subtracting the mean from the maximum possible for the scale, to ensure that all the scales pointed in the same direction. For data entry into RevMan, we consistently multiplied the mean values by ‐1 for those scales where a higher score implies lower disease severity, unless this correction had already been made in the published report. Where there was ambiguity about the method of correction, we contacted the study investigators for further information.

Timing of outcome assessment

We extracted data for the following time points:

post‐intervention assessment, immediately post‐intervention (up to one month following the delivery of the intervention);

short‐term follow‐up assessment, two to six months post‐intervention;

long‐term follow‐up assessment, more than six months post‐intervention.

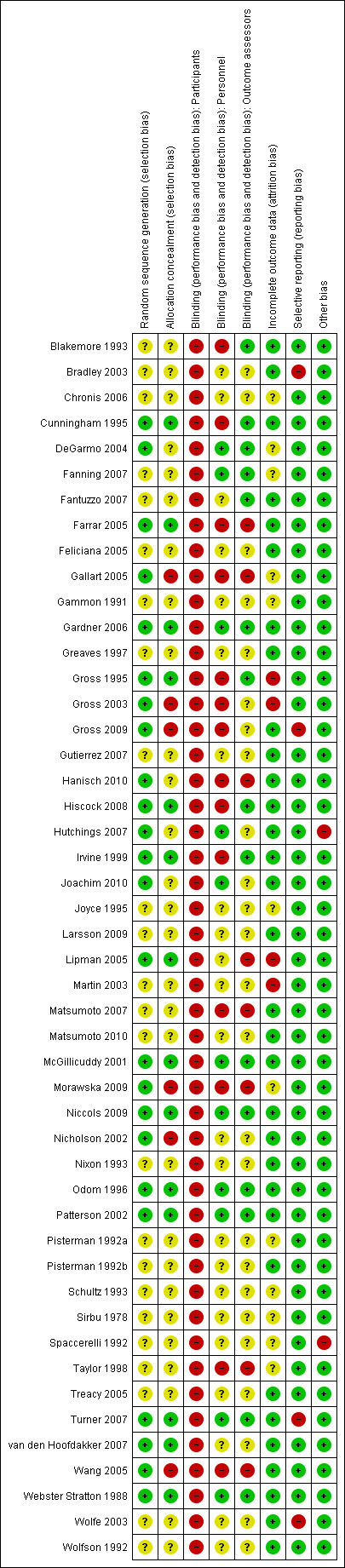

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, three review authors (NH, NS and HJ) independently completed the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2008, Section 8.5.1). Any disagreement was resolved in consultation with a third review author (CB). We assessed the degree to which:

the allocation sequence was adequately generated (‘sequence generation’);

the allocation was adequately concealed (‘allocation concealment’);

knowledge of the allocated interventions was adequately prevented during the study (‘blinding’);

incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed;

reports of the study were free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting;

the study was apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias.

Each domain was allocated one of three possible categories for each of the included studies: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or 'unclear risk' where the risk of bias was uncertain or unknown.

The first published version of this review used a quality assessment method that we elected not to use in this updated review, instead following guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) concerning the assessment of risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous data that were reported using standardised scales, we calculated a standardised mean difference (effect size) by subtracting the mean post‐intervention scores for the intervention and control groups and dividing by the pooled standard deviation.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

The randomisation of clusters can result in an overestimate of the precision of the results (with a higher risk of a Type I error) where their use has not been compensated for in the analysis. Some meta‐analyses involved combining data from cluster‐randomised trials with data from individually‐randomised trials. Five of the included studies were cluster‐randomised (Wolfson 1992; Gross 2003; Hiscock 2008; Gross 2009; Hanisch 2010). The impact of the cluster RCTs was explored using a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis, below) and we made no adjustments to the data.

Cross‐over trials

None of the included studies involved cross‐over randomisation.

Multi‐arm trials

Eleven studies utilised more than one intervention group (Sirbu 1978; Webster Stratton 1988; Spaccerelli 1992; Blakemore 1993; Cunningham 1995; Greaves 1997; Taylor 1998; Gross 2003; Gallart 2005; Gutierrez 2007; Larsson 2009). None of the interventions in these studies were sufficiently similar to be combined to create a single pair‐wise comparison, therefore for studies where there was more than one active intervention and only one control group, we selected the intervention that most closely matched our inclusion criteria and excluded the others. In only one study (Gutierrez 2007) was it possible to include both intervention arms in the study without double counting, as a result of the use of a second control group. Gutierrez 2007 compared two parenting programmes: the 1‐2‐3 Magic Program (classified as behavioural parenting program in our review) and the STEP program (Adlerian, assigned to 'other' types of parenting in our review) against attention placebo (where parents received lectures on topics of interest unrelated to parenting) or a wait‐list control condition. In our analyses we compared the behavioural parenting program with the wait‐list control group and the STEP program with the attention placebo group.

Dealing with missing data

We assessed missing data and dropouts for each included study and we report the number of participants who were included in the final analysis as a proportion of all participants in each study. We provide reasons for missing data in the 'Risk of bias' tables of the 'Characteristics of included studies' section.

We attempted to contact the trial investigators to request missing data and information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the extent of between‐trial differences and the consistency of results of meta‐analyses in three ways. We assessed the extent to which there were between‐study differences, including the extent to which there were variations in the population group or clinical intervention, or both. We combined studies only if the between‐study differences were minor.

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. The importance of the observed value of I2 is dependent on the magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity (for example, P value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2008), and we interpreted I2 > 50% as evidence of substantial heterogeneity. We also performed the Chi2 test of heterogeneity (where a significance level less than 0.10 was interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity). We used a random‐effects model as the standard approach and identified significant heterogeneity using subgroup analyses.

Data synthesis

The included studies used a range of standardised instruments to measure similar outcomes. For example, depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory, the Irritability, Depression and Anxiety Scale and the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. We standardised the results from these different measures by calculating the treatment effect for each outcome in each study and dividing the mean difference in post‐intervention scores for the intervention and treatment groups by the pooled standard deviation to produce an effect size. Where appropriate, we then combined the results in a meta‐analysis. The decision about whether to combine data in this way was determined by the levels of clinical and statistical heterogeneity present in the population, intervention and outcomes used in the primary studies.

We have presented the effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for individual outcomes in individual studies using figures only and have not provided a narrative presentation of individual study results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

No subgroup analysis was undertaken because there was insufficient evidence of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

At the time of the first update of this review (2003), sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact on the results of the two studies classified as quasi‐randomised. This was not repeated for the current update since both studies were reclassified as excluded. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate the potential impact of cluster‐randomisation methods in five studies. We had planned an a priori sensitivity analyses for studies focusing on children with disabilities, but none of the included studies involved parents of disabled children.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The updated electronic searches in January 2008, March 2010 and December 2011 produced 16,609 records. The obvious duplicates were removed by one review author (NS), who inspected the abstracts and discarded 16,477 irrelevant records. Most of articles reviewed were written in English. All studies in languages other than English had abstracts in English and we excluded all these studies on the basis of the information contained in the abstracts, apart from three German studies (Heinrichs 2006; Franz 2007; Naumann 2007), which are awaiting assessment as they need to be translated. We obtained a full text copy of 132 potential included studies and two review authors independently examined each study (NS and NH). JB and CB provided advice on any studies about which there was uncertainty.

Included studies

This updated review includes 48 studies, 28 of which were published since the previous review (Barlow 2003) that were identified using full text screening against inclusion criteria (Bradley 2003; Gross 2003; Martin 2003; Wolfe 2003; DeGarmo 2004; Farrar 2005; Feliciana 2005; Gallart 2005; Lipman 2005; Treacy 2005; Wang 2005; Chronis 2006; Gardner 2006; Fanning 2007; Fantuzzo 2007; Gutierrez 2007; Hutchings 2007; Matsumoto 2007; Turner 2007; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Hiscock 2008; Gross 2009; Larsson 2009; Morawska 2009; Niccols 2009; Hanisch 2010; Joachim 2010; Matsumoto 2010). Two review authors (NS and NH) independently re‐examined the 26 studies included in the previous version of the review against the inclusion criteria and retained 20 of them in this review. Six previously included studies (Van Wyk 1983; Scott 1987; Anastopoulos 1993; Mullin 1994; Sheeber 1994; Zimmerman 1996) were excluded in this update because they did not meet the more rigorous inclusion criteria being applied (see Excluded studies for further details).

We have provided further details about the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

All 48 included studies were randomised controlled trials.

Most studies were two‐condition comparisons of group‐based parenting programmes against a control group (n = 37). Eleven studies utilised more than one intervention group (Sirbu 1978; Webster Stratton 1988; Spaccerelli 1992; Blakemore 1993; Cunningham 1995; Greaves 1997; Taylor 1998; Gross 2003; Gallart 2005; Gutierrez 2007; Larsson 2009). Gutierrez 2007 compared two parent education programmes (behavioural‐based and Adlerian) against two control groups, 'attention placebo' or a wait‐list control condition. In our analyses of data from this trial, we compared the behavioural parenting programme with the wait‐list control group and the Adlerian programme with the attention placebo group.

Seven studies used a no‐treatment control group (Gammon 1991; Schultz 1993; Gross 1995; Greaves 1997; Patterson 2002; DeGarmo 2004; Hanisch 2010); three studies used a treatment‐as‐usual control group (Fantuzzo 2007; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Hiscock 2008), and three studies used an attention placebo control group (Sirbu 1978; Farrar 2005; Gutierrez 2007). In Farrar 2005 the attention placebo group received information about choosing developmentally appropriate books for their pre‐school children; in Gutierrez 2007, which had two control conditions, participants in the 'attention placebo' group were either presented lectures on topics of interest to them, but unrelated to parenting, or assigned to a wait‐list control group. In Sirbu 1978, the attention placebo group did not utilise any materials or have a professional leader, and the sessions were unstructured. The remaining 35 studies used only a wait‐list control group.

Cluster‐randomised studies

Five studies were cluster‐randomised trials (Wolfson 1992; Gross 2003; Hiscock 2008; Gross 2009; Hanisch 2010). Gross 2003 used day centres as the unit of allocation; in total seven day centres were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions: ‘parent training plus teacher condition’ (n = 4); ‘teacher training condition’ (n = 4), and ‘control condition’ (n = 3). The control centres received no intervention for at least one year, after which new parents were recruited and the centres were transferred to the ‘parent training condition’ (n = 3). Hanisch 2010 used kindergartens as the unit of allocation: 58 kindergartens were randomised to the intervention group (n = 32) or to the control group (n = 26). Hiscock 2008 used primary‐care nursing centres as the unit of allocation: 40 centres were randomly assigned to the intervention group (n = 18) or to the control group (n = 22). Wolfson 1992 employed randomisation by childbirth class: 25 childbirth classes were randomised but no further details were given.

Sensitivity analysis

The randomisation of clusters can result in an overestimate of the precision of the results (with a higher risk of a Type I error) where their use has not been compensated for in the analysis. We therefore conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate cluster effects. For this, we assumed the intracluster correlation to be 0.2, which is much bigger than normally expected. For two of the five cluster‐RCTs (Wolfson 1992; Hiscock 2008), we only had information about the number of clusters at randomisation and we therefore assumed a worst case scenario using the maximal possible cluster size, taking into account the dropouts during the study. Based on these assumptions, we assessed that the results of the meta‐analyses were robust to any clustering effects for most outcomes.

In the worst case scenario there is potential for the confidence interval to widen, depending on the weight of the clustered studies in the meta‐analysis. In cases where the effect size is borderline non‐significant (for example, analysis 1.1.2), there is potential for the meta‐analysis to become borderline significant after the adjustment. Conversely, there is potential for previous significance to be overcome following the adjustment.

In all analyses involving cluster‐corrected standard errors, the adjusted effect sizes were equivalent to the unadjusted effect sizes. In addition, in all cases the statistical conclusions were unchanged from the uncorrected to the corrected analyses.

Sample sizes

There was considerable variation in sample size between studies. Altogether the 49 included studies initially randomised 4937 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 22 to 733 (mean 102.9; median 60). Five large trials (Irvine 1999; Gross 2003; DeGarmo 2004; Hiscock 2008; Gross 2009) randomised a total of 1830 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 238 to 733 (mean 366; median 292). A further 11 studies (Webster Stratton 1988; Spaccerelli 1992; Cunningham 1995; Taylor 1998; Patterson 2002; Bradley 2003; Lipman 2005; Fantuzzo 2007; Hutchings 2007; Larsson 2009; Hanisch 2010) randomised 1481 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 110 to 198 (mean 134.6; median 126). The remaining 32 studies involved 1626 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 22 to 96 (mean 50.8; median 51).

Seven studies (Sirbu 1978; Gammon 1991; Spaccerelli 1992; Pisterman 1992b; Blakemore 1993; Schultz 1993; Bradley 2003) did not provide sufficient data to calculate effect sizes. The remaining 41 studies included in total 3416 participants with sample sizes ranging from 16 to 671 (mean 83.3; median 82).

Setting

Twenty‐two studies were conducted in the USA, 10 in Australia, seven in Canada and three in the UK. The remaining studies were conducted in China, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands and New Zealand. Most studies (n = 32) were single‐centre trials.

In 41 studies, participants were recruited from community settings by a variety of methods including flyers, emails and advertisements directed at parents of young children, or self‐referral (Sirbu 1978; Gammon 1991; Spaccerelli 1992; Wolfson 1992; Blakemore 1993; Nixon 1993; Schultz 1993; Gross 1995; Joyce 1995; Odom 1996; Greaves 1997; Taylor 1998; Webster Stratton 1988; Irvine 1999; McGillicuddy 2001; Nicholson 2002; Bradley 2003; Gross 2003; Martin 2003; Wolfe 2003; DeGarmo 2004; Farrar 2005; Feliciana 2005; Gallart 2005; Lipman 2005; Wang 2005; Chronis 2006; Gardner 2006; Fanning 2007; Fantuzzo 2007; Gutierrez 2007; Hutchings 2007; Matsumoto 2007; Turner 2007; Hiscock 2008; Gross 2009; Morawska 2009; Niccols 2009; Hanisch 2010; Joachim 2010; Matsumoto 2010); in one study from a primary care setting (Patterson 2002); in three studies from outpatient settings including an outpatient mental health clinic (van den Hoofdakker 2007), child psychiatric outpatients departments (Larsson 2009) and from a university‐based research clinic (Treacy 2005); in three studies parents were recruited from both community and outpatient settings (Pisterman 1992a; Pisterman 1992b; Cunningham 1995).

The intervention was delivered in outpatient clinics (including research clinics and paediatric outpatient departments) in seven studies (Pisterman 1992a; Pisterman 1992b; Blakemore 1993; Taylor 1998; Treacy 2005; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Larsson 2009); in primary care in one study (Patterson 2002); and in the community in the remaining studies.

Participants

An inclusion criterion for this updated review was that participants were parents with responsibility for the day‐to‐day care of children. In 19 studies, both mothers and fathers were recruited (Webster Stratton 1988; Wolfson 1992; Pisterman 1992a; Pisterman 1992b; Blakemore 1993; Nixon 1993; Schultz 1993; Gross 1995; Taylor 1998; Irvine 1999; McGillicuddy 2001; Wang 2005; Fanning 2007; Hutchings 2007; Matsumoto 2007; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Larsson 2009; Hanisch 2010; Matsumoto 2010). Thirteen studies recruited mothers only (Sirbu 1978; Gammon 1991; Odom 1996; Greaves 1997; Wolfe 2003; DeGarmo 2004; Farrar 2005; Feliciana 2005; Lipman 2005; Chronis 2006; Gutierrez 2007; Hiscock 2008; Niccols 2009). Either the mother or the father was recruited in 12 studies (Spaccerelli 1992; Cunningham 1995; Joyce 1995; Patterson 2002; Bradley 2003; Martin 2003; Gallart 2005; Gardner 2006; Fantuzzo 2007; Turner 2007; Morawska 2009; Joachim 2010). Four studies recruited not only biological parents but also grandparents, foster parents, step parents and relatives (Nicholson 2002; Gross 2003; Treacy 2005; Gross 2009). The studies included in this review were largely directed at mothers, and the trial investigators reported results that were mainly derived from the mothers.

Interventions

We provide a description by category of the structure and content of the parenting programmes that were evaluated in the included studies in 'Additional Table 1'. We have grouped the interventions into five categories according to the basic theoretical premise underpinning the programme (for example, behavioural and cognitive‐behavioural programmes) or, where there was a sufficient number of studies, according to the brand of the programme (Incredible Years and Triple‐P parenting programmes). A small group of programmes were unclassifiable (other and non‐branded multimodal programmes). For the purpose of analysis we categorised the studies as below.

1. Description of the parenting programmes.

| Study ID | Aim | Content/delivery |

| Behavioural only | ||

| Bradley 2003 | To evaluate the effects of a brief parenting programme on positive and negative parenting behaviours. | Brief behavioural parenting program consisted of three weekly 2‐hour group meetings with booster session 4 weeks after the third session. The intervention included video material (1‐2‐3 Magic) on managing difficult child behaviours, handouts and mutual support/problem solving work. |

| Cunningham 1995 | To examine the efficacy of a large group‐based parenting programme as a means of increasing the accessibility of such programmes to parents of children with disruptive behaviour; to determine whether parenting programme improve parental sense of competence and decrease depressive symptoms. | Coping modelling problem‐solving parenting programme comprised 11‐12 weekly sessions, involving the formulation of solutions through the observation of videotapes, discussion, modelling and role play. Homework reviewed each week. |

| DeGarmo 2004 | To evaluate changes in parent management and subsequently changes in child behaviour and maternal affects over time. | Parent Management Training (PMT) was a series of parent group meetings and discussion (14 weekly sessions). Interventionists made midweek telephone calls to encourage the participation. The program included a 30‐minute video, and covered 5 theoretically based effective parenting practices (appropriate discipline, skill encouragement, monitoring, problem solving, and positive reinforcement). Individual catch‐up sessions offered to replace missed sessions; 10% participants had at least one individual session. |

|

Gallart 2005 |

To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme and assess the impact of telephone contact sessions in developing positive relationships, in encouraging desirable behaviour, in teaching new skills and behaviours, and in managing misbehaviour. | The full Group Triple‐P program comprised four weekly 2‐hour group sessions and four weekly follow‐up telephone calls. The programmes standard Facilitators Kit (leaders manual, AV materials, participants workbook) was used, plus a video (Every Parents Survival Guide). The modified Group Triple‐P program is the standard programme delivered as four weekly 2‐hour group sessions but without the four follow‐up telephone contacts. |

| Gutierrez 2007 (behavioural) | To evaluate the efficacy of two parenting programmes in reducing perceived parental stress | Behaviourally‐based parenting programme (BPP)1‐2‐3 Magic Parenting Program included components on parents reactions to their child's misbehaviour, using time‐out, dealing with testing and manipulation, positive reinforcement, and preventing relapses. see below for description of Adlerian parenting program. Compared two active parenting interventions with an attention placebo program and a wait‐list control group. Each programme consists of eight 2‐hours‐weekly sessions, delivered in Spanish. |

| Hanisch 2010 | To evaluate the effects of a parenting programme on child behaviour, parenting practices, parent‐child interaction, and parent quality of life | Prevention Programme for Externalising Problem behaviour (PEP) consisted of ten weekly sessions (80‐120 minutes each). The first three sessions focused on defining individual problem situations, introducing unspecific basic strategies. The next three sessions thought participants the classical key strategies of behaviour modification. Sessions 7 to 10 consolidated these strategies by working on common difficult parenting situations. Individual homework assessments and telephone supervision were provided. |

| Hiscock 2008 | To assess the effectiveness of a parenting programme in preventing early childhood behavioural problems |

The Universal parenting programme comprised of three structured sessions, covering normal development and behaviour, strategies to increase desired behaviour, and strategies to reduce unwanted behaviour. First session (child at 8 months) consisted of handouts; second and third sessions (child at 12 and 15 months) were 2‐hour group sessions. Training incorporated didactic teaching, written information, role play and video vignettes of appropriate parenting responses to childhood behaviours. |

| Joachim 2010 | To assess the effectiveness of a brief parent training in preventing behaviour problems on shopping trips. |

Brief, two‐hour, topic‐specific parent discussion group based on the Triple P‐Positive Parenting Program. Intervention entitled Hassle‐free Shopping was for parents looking for specific advice on how to manage their child's behaviour in the supermarket and how to prevent behaviour problems on shopping trips. |

| Irvine 1999 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme provided by non‐mental health providers who are more likely to be available in small communities. |

Adolescent Transition Program was a stepwise, skill‐based curriculum designed to teach parenting skills. Content included: positive reinforcement, parental monitoring, limit‐setting, parent‐child communication, and problem solving. 12 weekly sessions (90 minutes‐2 hours each). Skills discussed in group then practiced at home with group feedback the following week. |

| Martin 2003 | To evaluate the effects of a parent training in managing parents successfully functioning at work, at home, and in their parenting role. |

Work Place Triple‐P program (WPTP) consisted of four sessions (2 hours each), and four additional individual telephone consultations (15 to 30 minutes each). It was designed specifically for delivering in the workplace and involved i) teaching parents 17 core positive parenting and child management strategy; ii) planning activities routine for times such as getting ready for work and arrival home from work; iii) active training methods such as video modelling, rehearsal, practice, feedback and goal setting Parents received copy of a workbook that included exercises for completion both in‐session and between sessions. |

| Matsumoto 2007 | To evaluate the efficacy and acceptability of a parenting programme with Japanese parents in learning and practicing positive parenting skills |

Triple P‐Positive Parenting Program comprised of five sessions (2‐hours each), and three telephone consultation sessions (20‐30 minutes each). Active skills training methods were used to facilitate the development of a self‐regulatory framework for parents, involving modelling, role‐plays, feedback and the use of specific homework. All sessions conducted in Japanese by a Japanese accredited Triple P trainer. |

| Matsumoto 2010 | To evaluate the efficacy and acceptability of a parenting programme with Japanese parents in Japanese society in learning and practicing positive parenting skills |

Triple P‐Positive Parenting Program comprised of five sessions (2‐hours each), and three telephone consultation sessions (20‐30 minutes each). Active skills training methods were used to facilitate the development of a self‐regulatory framework for parents, involving modelling, role‐plays, feedback and the use of specific homework. All sessions conducted in Japanese by a Japanese accredited Triple P trainer. |

| Morawska 2009 | To assess the efficacy of a parenting program in enhancing parenting skills, and subsequently in improving the behavioural and emotional adjustment of their gifted child. |

Gifted and Talented Group Triple P programme (based on the Group Triple P intervention) consisted of five weekly sessions (2 hours each), followed by three weekly telephone consultations (15‐minutes each), and a final 2 hours group session. The program involved teaching parents core child management skills: i) promoting children's development, ii) managing misbehaviour, and iii) planned activities and routines |

| Niccols 2009 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in preventing challenging behaviour of their child. | COPEing with toddler behaviour comprised eight weekly group sessions (2 hours each) and focused on parenting styles and strategies in preventing challenging behaviour for children in late infancy/toddlerhood. |

| Odom 1996 | To determine whether parent training would improve a mother's knowledge about ADHD and her feelings of competence and self‐esteem in using problem‐solving strategies. | Educational programme comprised five weekly sessions (60‐90 minutes each), including information on the pathology of ADHD, its impact on family, the effects of stimulant medication, the meaning and development of a child's behaviour, enhancing positive mother‐child attention, time‐out, positive reinforcement, and the use of problem‐solving strategies. Weekly written handouts compiled in a booklet. |

| Pisterman 1992a | To assess the effects of a parenting programme on parenting stress and sense of competence in parents of children with ADHD. |

Parent training programme comprised twelve weekly sessions, including information on ADHD and instruction involving role‐play, modelling and homework assignments. Compliance training component differed slightly for Study 1 and Study 2. Reading material and manuals provided for participants. |

|

Pisterman 1992b |

To evaluate whether a parent mediated behaviour intervention could ameliorate ADHD related deficits and behavioural problems. |

Attention‐training treatment programme comprised twelve weekly sessions, including educational material and information about ADHD, compliance training (behaviour management) and attention training. Teaching methods includes modelling, role‐play, and individual feedback to videotaped interactions. |

| Sirbu 1978 | To investigate the effectiveness of a behavioural parenting programme. To examine whether lecture/written materials/combination were differentially effective in teaching behavioural principles. | Behavioural parenting programme comprised five weekly sessions (2 hours each) and a This intervention was used in Group 1. Group 2 received the same programme but without the text. Group 3 received the text only plus the exercises. Group 4 were a non‐intervention control group. |

| Turner 2007 | To assess the impact of a culturally sensitive adaptation of parenting programme on parental skills, parental stress, anxiety and depression. | Triple‐P Positive Parenting Program, culturally adapted, comprised eight sessions: i) one group introduction session, giving an overview of the program and establishing rapport within the groups (1.5‐2 hours); ii) four group sessions (2‐2.5 hours each); iii) two home‐based consultations (30‐40 minutes each); and iv) one final group session (1.5‐2 hours). The intervention covers modelling, rehearsal, practice, feedback and goal setting, considering needs of Australian Indigenous families. |

| van den Hoofdakker 2007 | To investigate the effectiveness of parenting training as adjunct to routine clinical care in enhancing parenting skills. | Behavioural Parenting Training (BPT) comprised twelve sessions (2 hours each). The program covers the following parenting skills: i) structuring the environment, ii) setting rules, iii) giving instructions, iv) anticipating misbehaviours, v) communicating, vi) reinforcing positive behaviour, vii) ignoring, viii) employing punishment, and ix) implementing token system. As a part of homework assignment, for each session parents read a chapter of a book written for this program (van der Veen‐Mulders et al, 2001); they also practice parental skills during each session, and wrote the reports. |

| Wang 2005 | To evaluate the effects of a parenting program on the interactive skills of parents of children with autism. | Educational parenting program comprised four weekly sessions (4 hours each), supported by home visits (4 hours in total). Training program included lectures, handouts, live modelling and group discussion, which was supported by individual home visits. The purpose of the individual home visits was to observe the parent/child interaction in the natural environment and assist parents in applying the intervention strategies thought during group training. |

| Wolfson 1992 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in promoting healthy, self‐sufficient sleep in infants; to test the hypothesis that parent training would reduce both stress and response to child wakefulness. | Behavioural parenting training comprised two prenatal sessions and two post‐natal sessions (1‐1/2 hours each). Content included information on infant sleep and methods to assist in establishing early good sleep habits. Handouts, questions and answers, group discussion and problem‐solving strategy used. Diaries and daily practice records completed and discussed. |

| Cognitive‐Behavioural Parenting Programme | ||

|

Blakemore 1993 |

To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in enhancing the self‐directedness of children with ADHD and responsibility for their own behaviour. |

Behaviour management parenting programme consisted of 12 weekly 2‐hour sessions delivered using a lecture format. Follow‐up (maintenance) sessions at 3‐ and 6‐months. Optional school consultation time offered. Topics included the re‐framing of ADHD, behaviour management based on the use of various techniques, the grief cycle, communication skills, listening, acknowledging feelings, self‐esteem, and anger‐management. |

| Chronis 2006 | To examine whether a parenting programme improve maternal functioning in terms of depressive symptoms, anxiety, self‐esteem, perceived stress and cognitions about child behaviour. | Maternal Stress and Coping Group Program was a modified version of the Coping With Depression Course Program (CWDCP), which increases its relevance for mothers of children with ADHD. It comprised twelve weekly sessions, including four treatment models: i) relaxing training, ii) increasing pleasurable activities, iii) cognitive restructuring, and iv) increasing social skills/assertiveness training. Homework exercises that involved practising behavioural skills were completed. |

| Gammon 1991 | To examine the effectiveness of a parenting programme in promoting coping skills in parents of children with developmental disabilities. | Coping Skills Training Programme consisted of ten 2‐hour weekly sessions, involving cognitive restructuring, interpersonal skills training, problem solving and individual goal attainment. |

| Gardner 2006 | To examine the effectiveness of a parenting programme in reducing child conduct problem, in enhancing positive parenting skills and confidence, and in decreasing parental depression |

Webster‐Stratton Incredible Years intervention comprised a video‐based 14‐week group programme which teaches behavioural principles for managing behaviours using a collaborative, practical problem‐solving approach. Topics included parent‐child play praise, incentives, limit‐setting, problem‐solving and discipline. Each week parents practice tasks at home. Telephone calls made to encourage progress. |

| Gross 1995 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in promoting positive parent‐child relationships; to promote parental self‐efficacy. | Parent and Children Series (PACS) training programme for promoting positive parent‐child relationship consisted of 10‐weekly sessions, using manual, written materials and videos. Topics included: how to play with a child, use of praise, limit setting, use of time‐out. Video‐tape vignettes used to model skills and stimulate discussion. Weekly homework assignments used. |

| Gross 2003 | To evaluate the relative effectiveness of a parenting programme on parenting competence (higher parenting self‐efficacy, less reliance on coercive discipline strategies, and more positive parent behaviour) | Webster‐Stratton Incredible Years BASIC Programme comprised 12 weekly sessions (2 hours each). Topics covered included child‐directed play, helping young children to learn, using praise and rewards, effective limit setting, handling misbehaviour and problem solving. Home work assignments were also used. The course was taught using video vignettes which were appropriate for toddlers. |

| Gross 2009 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in improving parenting competence and child behaviour. | Chicago Parent Programme (CPP) comprised 12 weekly sessions, employing videotaped vignettes and group discussion. The topics covered the concept of child‐centred time, helping young children to learn, using praise and rewards, effective limit setting, handling misbehaviour and problem solving. |

| Greaves 1997 | To assess the effectiveness of a parenting programme in reducing parental stress in parents of children with disabilities. | Rational‐Emotive Parent Education programme comprised eight weekly sessions. Content focused on core irrational beliefs and links with stress response. Programme thought the disputation of these beliefs and their replacement with rational beliefs. Teaching based on a didactic approach and included homework, completion of worksheets, and the distribution of a prepared summary sheet. |

| Hutchings 2007 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme as a preventative intervention for parents with children considered to be at risk of developing conduct disorder | Webster‐Stratton Incredible Years Basic parenting programme comprised twelve weekly sessions (2 to 2.5 hours each) and promoted positive parenting, using a collaborative approach (for example: role play, modelling, discussion, etc). |

| Joyce 1995 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in reducing levels of parent irrationality, negative emotions, and to assess whether the change in irrationality is correlated with changes in emotionality. | Rational‐Emotive based Parent Education programme comprised nine weekly sessions Content focused on identifying and disputing parental irrational beliefs that lead to emotional stress; the reinforcement of rational beliefs; rational problem‐solving; teaching children rational personality traits. |

| Larsson 2009 | To examine the efficacy of a parenting programme in reducing child conducts problems. |

Webster‐Stratton Incredible Years Basic parenting programme consisted of twelve to fourteen weekly sessions (2 hours each), focusing on positive disciplinary strategies, effective parenting skills, strategies coping with stress, and ways to strengthen children's social skills. Video vignettes for discussion, role play, rehearsals and home work assessments used. |

| Lipman 2005 | To evaluate the effects of a community group‐based parenting programme on vulnerable single mothers in improving maternal wellbeing (mood, self‐esteem and social support) and parenting. | Social support and education parenting programme consisted of 10 weekly group sessions (1.5 hours each). The program covered two thematic areas: i) child related area (for example: child development and behaviour, behaviour management, school involvement, child welfare agencies), and maternal area (for example: social isolation, stress and coping, personal care and development, relationships, grief). Cognitive behavioural techniques and structured counselling were provided. |

| McGillicuddy 2001 | To examine the effectiveness of a coping skill training programme for parents of substance‐abusing adolescents |

Behavioural‐analytic parenting programme comprised eight weekly sessions (2 hours each). Aims were to teach participants more effective skills for coping with problems resulting from their adolescent's substance abuse. |

| Nicholson 2002 | To examine the effectiveness of a parenting programme with at‐risk parents of young children. | Psycho‐educational programme STAR (Stop Think Ask Respond) comprised 10 weekly sessions (1.5 hours each), employing 'segments' in which parents learned thoughtful ways to respond to children, how to have realistic expectations of children, and how to implement positive parenting and discipline strategies. |

| Nixon 1993 | To examine the effect of a short‐term intervention to reduce self‐blame and guilt in parents of children with severe disabilities. |

Cognitive‐behavioural parenting programme comprised five weekly sessions (2 hours each). Content delivered using a lecture format. Homework assigned each week consisted of monitoring automatic thoughts, cognitive distortions, negative feelings, and attempts at cognitive restructuring. Sessions focused on the cognitive distortions that contribute to self‐blame and guilt in families of children with disabilities, and techniques to deal with such distortions. |

|

Patterson 2002 |

To assess effects of a parenting programme delivered by health visitors in primary care in improving mental health of children and parents | Webster Stratton parenting programme comprised 10 weekly sessions (2 hours each). The sessions included video vignettes of parent‐child interactions, group discussion, role play, rehearsal of parenting techniques, and home practice. |

| Spaccerelli 1992 | To evaluate the additional benefit of providing a problem‐solving parenting intervention in improving parental and child behaviour. | Problem‐solving skills parenting training comprised 6 units (1 hour each), focusing on aspects of problem‐solving including: problem definition, goal setting, alternative solutions, and decision‐making. This training was used as a supplement to a 10‐hour Parent and Children Series (PACS) programme based on the work of Webster‐Stratton. Topics included how to play with a child, use of praise, limit setting, use of time‐out. Video‐tape vignettes used to model skills and stimulate discussion. Written materials and homework assignments used. |

| Taylor 1998 | To evaluate the effectiveness of parent training in reducing parental psychosocial difficulties and conduct problems in children. | Parent and Children Series (PACS) treatment intervention consisted of 11‐14 weekly sessions (2 ¼ each), using manual, written materials and videos. |

| Webster Stratton 1988 | To compare different treatment modes in reducing parental stress and improving child behaviour. |

GDVM: Group‐based video‐tape modelling parenting skills followed by discussion. IVM: Weekly in‐clinic sessions for approximately 1‐hour viewing of self‐administered videotape without therapist or discussion. GD: Weekly therapist‐led discussion sessions covering same topics as other groups. All modes of delivery comprised 10‐12 weekly sessions (2 hours each). Content, sequencing and number of sessions constant between groups. Topics covered play skills, praises, rewards, discipline and problem‐solving approaches |

| Other or multimodal | ||

| Fanning 2007 | To investigate the feasibility, implementation, and potential effects of a parenting programme on positive changes in parenting stress and child behaviour. | Success in Parenting Preschoolers (SIP) programme consisted of 8 weekly group sessions, each lasted 2 hours. The programme included both language facilitation techniques and behaviour management strategies. The parents viewed 100 instructional pages, watched four video vignettes, and received weekly session outlines, handouts, and home reminder magnets highlighting specific parenting skills presented during that weekly session. Additional weekly phone sessions were provided. All group sessions were videotaped. |

| Fantuzzo 2007 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a community‐based intervention on enhancing pro‐social interaction and psychological wellbeing of urban, Head Start parents. |

The COPE (Community Outreach through Parent Empowerment) intervention has two components: (a) informal support groups, and (b) implementation of the Parent as Change Agent for Self module. Involved 10 group‐training sessions (each ˜3 hrs) focusing on the relationship between stress and social support. The 10 sessions had two main purposes: to identify major categories of stressful events for urban, African‐American Head Start parents, and to consider and discuss the ways in which friendships and various connections within the community can mitigate these stressors. |

| Farrar 2005 | To examine the effect of a parenting intervention on parental stress scores. | A brief cognitively‐based group parenting training is a 30‐minute single‐session, which targeted mothers perception of a preschool‐age child. The session focused on shifting parent perception of the child. Parents learned about the connection between thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Duration of the training was in total 1.5 hours with questionnaire completion. Sessions were audio‐taped. Attention‐placebo control group received information regarding [use of] developmentally appropriate books for preschool age children during 30 minutes. The session (1.5 hours) involved questionnaire completion. |

| Feliciana 2005 | To examine the effects of a parenting programme on maternal sense of competency and stress | Active Parenting Programme was an educational programme and consisted of sessions (11/2 hours each). Content focused on understanding children's behaviour and misbehaviour, responsible parenting, effective communication and discipline, and developing responsibility in children. The training format used a variety of teaching techniques including lecture, videos, group discussion, and role‐play. |

| Gutierrez 2007 (Adlerian) | To evaluate the efficacy of two parenting programmes in reducing perceived parental stress | Adlerian‐based parenting programme (APP) is the Systematic Training for Effective Parenting (STEP) program which included components on understanding yourself and your child, beliefs and feelings, encouraging your child and yourself, listening and talking to your child and problem solving. Each programme consists of eight 2 hour weekly sessions, delivered in Spanish. |

| Schultz 1993 | To evaluate the effectiveness of a parenting programme in empowering parents to strengthen family resources. | Model based on a three‐tiered approach to developing personal coping and social support. Designed to strengthen interpersonal, intrapersonal and social resources by means of group work, discussion and didactic input. Topics included: family dynamics, loss and grief, communication and conflict resolution, networking and resource utilisation, stress management and relaxation skills. 12 2‐hourly sessions over 6 weeks. |

| Treacy 2005 | To assess the effectiveness of a parenting programme in reducing parenting stress, and in improving parental mood, family functioning, parenting style, locus of control, and perceived social support of children with ADHD. | Parent Stress Management (PSM) training program comprised nine weekly sessions (2 hour each). The program covered: Session 1: Orientation to the program and understanding stress; Session 2: Education about ADHD; Session 3: Rights and reasons; Session 4: Problem‐solving skills; Session 5: Cognitive restructuring; Session 6: Communication skills; Session 7: Self‐care skills; Session 8: Parenting skills; Session 9: Wrap‐up session. |

| Wolfe 2003 | To evaluate the effects of a parenting programme in enhancing parent adaptive behaviour through emphasis on parental self‐reflection, social support and the emotional roots of children's misbehaviour and parenting stress. | Study 1 ‐ Counselling and social support parent programme. Listening to Children (LTC) parent training comprised eight weekly sessions (2.5 hours each) and was based on re‐evaluation counselling. It focused on the three core themes: recognising the effects of parents own childhood experience, spending special time with children, and understanding and handling children's emotions and upsets. Each session involved in‐class activities, reading assignments, and homework projects built around those themes. |

i) Behavioural parenting programmes

Twenty‐two studies evaluated the effectiveness of a behavioural parenting programme (Sirbu 1978; Wolfson 1992; Pisterman 1992a; Pisterman 1992b; Blakemore 1993; Cunningham 1995; Odom 1996; Irvine 1999; DeGarmo 2004; Wang 2005; Gutierrez 2007; van den Hoofdakker 2007; Hiscock 2008; Niccols 2009; Hanisch 2010; Martin 2003; Gallart 2005; Matsumoto 2007; Turner 2007; Morawska 2009; Joachim 2010; Matsumoto 2010). This category included programmes which are primarily behavioural in orientation and that are based on social learning principles. These programmes teach parents how to use a range of basic behavioural strategies for managing children’s behaviour. Triple‐P programmes are included in this category.

ii) Cognitive‐behavioural parenting programmes

Nineteen studies evaluated the effectiveness of a cognitive‐behavioural parenting programme (Webster Stratton 1988; Gammon 1991; Spaccerelli 1992; Blakemore 1993; Nixon 1993; Gross 1995; Joyce 1995; Greaves 1997; Taylor 1998; McGillicuddy 2001; Nicholson 2002; Patterson 2002; Gross 2003; Lipman 2005; Chronis 2006; Gardner 2006; Hutchings 2007; Gross 2009; Larsson 2009). These programmes combined the basic behavioural type strategies with cognitive strategies aimed at helping parents to identify and change distorted patterns of belief or thought that may be influencing their behaviour. Webster‐Stratton Incredible Years programmes were included in this category.

iii) Other and multimodal

It was not possible to classify the interventions from eight studies (Schultz 1993; Wolfe 2003; Farrar 2005; Feliciana 2005; Treacy 2005; Fanning 2007; Fantuzzo 2007; Gutierrez 2007) based on the information provided. See Table 1 for further information about these programmes.

Duration of the intervention

We have described the duration of the intervention as 'standard' in 36 studies (8 to 14 sessions), 'brief' in 10 studies (1 to 6 sessions) and 'long' in two studies (16 weeks or more).

Outcomes

All outcomes were parent‐report and involved the use of a variety of standardised instruments. We assessed outcomes at three time points: immediately post‐intervention (up to one month following the delivery of the intervention), short‐term follow‐up (two to six months post‐intervention) and long‐term follow‐up (more than six months post‐intervention).

Primary outcome measures

Depressive symptoms

Twenty‐nine studies assessed the impact of a parent training programme on parental depressive symptoms. Nine studies used the Beck Depression Inventory (Nixon 1993; Cunningham 1995; Taylor 1998; Irvine 1999; McGillicuddy 2001; Treacy 2005; Chronis 2006; Gardner 2006; Hutchings 2007); nine studies used the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Martin 2003; Gallart 2005; Matsumoto 2007; Turner 2007; Hiscock 2008; Morawska 2009; Hanisch 2010; Joachim 2010; Matsumoto 2010); six studies used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (Gross 1995; Gross 2003; DeGarmo 2004; Lipman 2005; Gross 2009; Niccols 2009); three studies used the Parent Stress Index (Pisterman 1992a; Greaves 1997; Feliciana 2005); Patterson 2002 used the General Health Questionnaire; and Bradley 2003 used the Irritability Depression Anxiety Scale.

Anxiety symptoms