Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Epidemiological data on patients with COVID-19 referred to specialized weaning centers (SWCs) are sparse, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Our aim was to describe clinical features, epidemiology, and outcomes of subjects admitted to SWCs in Argentina.

METHODS:

We conducted a prospective, multi-center, observational study between July 2020–December 2021 in 12 SWCs. We collected demographic characteristics, laboratory results, pulmonary function, and dependence on mechanical ventilation at admission, decannulation, weaning from mechanical ventilation, and status at discharge. A multiple logistic model was built to predict home discharge.

RESULTS:

We enrolled 568 tracheostomized adult subjects after the acute COVID-19 phase who were transferred to SWCs. Age was 62 [52–71], males 70%, Charlson comorbidity index was 2 [0–3], and length of stay in ICU was 42 [32–56] d. Of the 315 ventilator-dependent subjects, 72.4% were weaned, 427 (75.2%) were decannulated, and 366 subjects (64.5%) were discharged home. The mortality rate was 6.0%. In multivariate analysis, age (odds ratio 0.30 [95% CI 0.16–0.56], P < .001), Charlson comorbidity index (odds ratio 0.43 [95% CI 0.22–0.84], P < .01), mechanical ventilation duration in ICU (odds ratio 0.80 [95% CI 0.72–0.89], P < .001), renal failure (odds ratio 0.40 [95% CI 0.22–0.73], P = .003), and expiratory muscle weakness (odds ratio 0.35 [95% CI 0.19–0.62], P < .001) were independently associated with home discharge.

CONCLUSIONS:

Most subjects with COVID-19 transferred to SWCs were weaned, achieved decannulation, and were discharged to home. Age, high-comorbidity burden, prolonged mechanical ventilation in ICU, renal failure at admission, and expiratory muscle weakness were inversely associated with home discharge.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, tracheostomy, prolonged mechanical ventilation, specialized weaning centers, critical illness

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019 led to increased ICU admissions for severe respiratory failure and ARDS requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, which have been described, characterized, and reviewed elsewhere.1–3 Many patients remained dependent on mechanical ventilation after the acute event and progressed to chronic critical illness.4–6 As with any disease, withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in the ICU can sometimes be problematic.4,7

Specialized weaning centers (SWCs) provide a comprehensive, multi-professional package of care. This includes weaning from mechanical ventilation as well as respiratory and general rehabilitation for patients with tracheostomy ventilation.5,8–10 Many articles have reported on the epidemiology and outcomes of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who were critically ill in the ICUs.1–3,7 In contrast to these detailed reports,2,3,7 there is limited information about patients with COVID-19 once transferred to SWCs or long-term acute hospitals (LTACHs). A few relevant studies come from high-income countries.5,6,11 COVID-19 spread worldwide and has become a top public health concern. Argentina experienced a high strain on the national health system, with up to 91% of the ICU beds installed throughout the country were occupied.12 Consequently, the SWCs changed their usual profile to care for patients after the acute COVID-19 phase in ICUs. Argentina is an upper-middle-income country with a fragmented health care system.13–15 Patients from public health systems are assisted in private care centers using various modalities; however, most referrals are from privates ICUs.

In this context, the Consortium Group Re.Des launched a prospective cohort study with the aim of describing the clinical features, epidemiology, and outcomes of tracheostomized subjects with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 who were critically ill in the ICU and admitted to an SWC after ventilation for SARS-CoV-2 infection. We were particularly interested in describing aspects related to the process of weaning from ventilatory support, decannulation, and home discharge.

QUICK LOOK.

Current knowledge

Specialized weaning centers (SWCs) are found in several European and North American countries but not in low- and middle-income countries. Argentina has facilities comparable to SWCs, but no studies have been published on their capacity to receive better patients post COVID-19.

What this paper contributes to our knowledge

In this prospective, multi-center cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of SWC subjects were weaned from mechanical ventilation and discharged home. Age, high comorbidity burden, prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU, renal failure at admission, and expiratory muscle weakness were inversely associated with home discharge. The decannulation rate was 75.2%.

Methods

Settings

We conducted a prospective, multi-center, observational study between July 1, 2020–December 15, 2021, in 12 SWCs from Argentina.

SWCs and Subject Characteristics

We included an SWC if it met all the following criteria: located outside the acute hospital with a multidisciplinary team in charge; > 15 beds available for weaning from mechanical ventilation; daily rehabilitation staff with speech language therapists, occupational therapists, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, psychologists, nutritionists, clinicians, and pneumonologists; and ability to perform blood gas analysis at any time. Seventeen SWCs fulfilled these criteria to be included. Finally, 12 SWCs signed the Consortium Group Re.Des and participated in the study.

We consecutively enrolled tracheostomized adult subjects (≥ 18 y) after the acute COVID-19 phase, transferred from an Argentinian ICUs to a participating SWC during the study period. Subjects met one of the following inclusion criteria: (1) respiratory failure caused by SARS-CoV-2 as the primary reason for mechanical ventilation in the ICU and (2) other primary indications for invasive ventilation and COVID-19 infection acquired de novo in the ICU. We excluded patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the SWCs. All subjects with COVID-19 had a positive laboratory polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2. Further inclusion and exclusion criteria were not considered, such as the feasibility of being weaned from mechanical ventilation or decannulated, level of consciousness, or other variables which a priori could impact the main outcomes. The characteristics of participating SWCs and distribution of subjects across facilities are summarized in Table A1 (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com).

Variables Collected at SWCs Admission and During Subjects' Stay

The following data were recorded for each subject: demographics: age (y); sex; Charlson comorbidity index;16 clinical frailty score;17 the primary reason for mechanical ventilation and its duration; time to tracheostomy (d); length of stay (LOS) and the presence of prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU, defined as 21 consecutive days of mechanical ventilation for 6 h/d;18 and at SWC admission: body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), need for mechanical ventilation, creatinine (mg/dL), albumin (g/dL), thyroid-stimulating hormone (µU/mL), hemoglobin (g/dL), maximal static inspiratory and expiratory pressure (cm H2O) with its predictive value,19 general muscle strength through Medical Research Council, and Glasgow coma scale.

During the clinical course in the SWC, we recorded LOS, mechanical ventilation duration, weaning success (defined as > 7 consecutive days without ventilator assistance and clinical stability),20 reinstatement of mechanical ventilation after weaning success,21 tracheostomy use (d), tracheostomy decannulation, and decannulation failure (need to restore artificial airway within 7 d after decannulation). In addition, we documented status at discharge from SWCs as home discharge, transferred to ICU, transferred to other facilities (problems with health care insurance, family, and/or medical consensus), remained at the SWC (6 months from admission), or death.

Data Collection and Processing

Data were collected by the study coinvestigator for each participating center or by any member of the team appointed for the study, using specially-designed case report forms (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com) and REDCap software installed on the servers at Centro del Parque, Buenos Aires, Argentina. All responsible parties from the participating centers were granted access to the web site in which all documents of the study were available (including the operative definition of the variables, the manual of procedures, and the corresponding links to calculate clinical scores). To minimize missing data, a mobile app was enabled for offline data uploading. Local coinvestigators were responsible for training their team in data collection and quality control. Data consistency was assessed daily (missing data, outliers, upload errors) by one of the members of the research leading staff (EN). Whenever further information about data was required, other members of the research team (ELDV and DV) contacted the researchers of the participating centers.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported using median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean and SD for continuous variables as appropriate. Normal distribution was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables as appropriate; chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables.

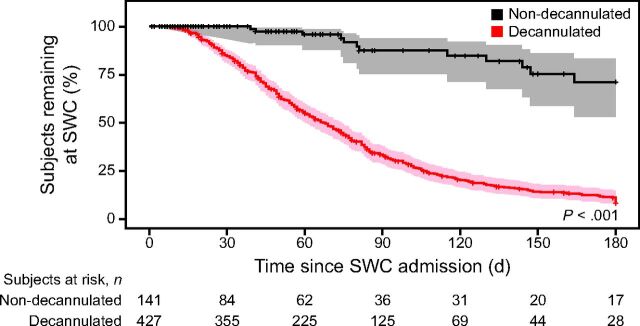

To identify predictors of home discharge, we fitted a logistic regression model with key predictors as independent variables (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com) and status at discharge as the dependent variable. We excluded subjects from this analysis who remained at the SWC or transferred to another facility for any reason, as described above. The relationship between the outcome and exposure was initially determined by univariate analysis. To include in the final regression model as judged by Schwartz information criterion, the best subsets regression analysis was used to identify the optimal combination of predictor variables, which had a P value < .2 (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com). All selected variables were reported with their corresponding odds ratio and respective 95% CI. The goodness of fit of the final model was analyzed through the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and its discrimination ability was evaluated through the area under the curve and 95% CI. Finally, the predictive power of the model was evaluated through K-fold cross-validation (10-folds).22 Missing data distribution across centers is reported in e-table A2 (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com). As a sensitivity analysis, the primary analysis was repeated post hoc with imputed values to replace missing values (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com). Kaplan-Meier curves were used to assess home discharge for up to 6 months in decannulated and non-decannulated subjects.

As this was an observational study, we decided to include as many subjects as possible without a predetermined sample size. A 2-sided P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with R version 4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of human experimentation of the Argentine Society of Critical Care and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. The original study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Argentinian Critical Care Society (registered code 3286). As it was an observational study during the pandemic, the IRB accepted the waiver of informed consent when approving the protocol.

Results

Subject Demographics and Clinical Course in ICU

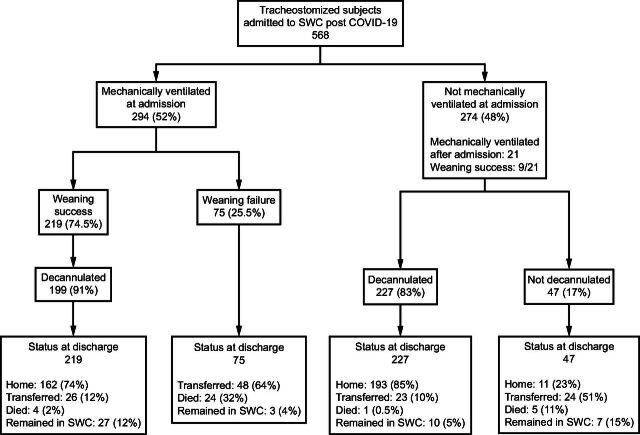

During the study period, 568 consecutive, adult, tracheostomized, post-acute subjects with COVID-19 were admitted to the SWCs; 294 (52%) required mechanical ventilation at admission, while 21 (7.6%) spontaneously breathing subjects needed ventilatory support after admission (Fig. 1). The demographic characteristics of enrolled subjects are shown in Table 1. On SWC admission, no subject required hemodialysis. The median ICU LOS was 42 [32–56] d, while the median days of mechanical ventilation prior to SWC transfer was 36 [28–51] d; 446 (93%) required prolonged mechanical ventilation. The median days [IQR] from mechanical ventilation before tracheostomy was 18 [14–22] d. Clinical, laboratory, and pulmonary function data at SWC admission are also shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Outcomes across subjects related to weaning and decannulation status. SWC = specialized weaning center.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics, Characteristics, and Outcomes

SWCs Outcomes

Of the 315 ventilator-dependent subjects, weaning success was achieved in 228 (72.4%). Overall, 427 subjects (75.2%) were decannulated. The median SWC LOS was 60 [33–98] d. Three hundred sixty-six subjects (64.5%) were discharged home. Clinical course and outcomes, including transfer to ICU and discharge status, are shown in Table 1. Overall mortality was 6.0%. No subject discharged home required mechanical ventilation. Figure 1 shows outcomes across subjects related to weaning and decannulation status, while outcomes across facilities are shown in e-table A3 (see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com). No statistically significant differences were found for weaning or decannulation between centers with or without formal protocols for weaning (chi-square = 0.125, degrees of freedom [df] = 1, P = .72) or decannulation (chi-square = 0.159, df = 1, P = .21; see related supplementary materials at http://www.rcjournal.com) from mechanical ventilation. The median time to home discharge was 59 [37–86] d, to ICU transfer was 32.0 [11.0–73.3] d, and to death was 44.0 [17.3–88.3] d.

Univariate analysis of clinical characteristics and outcomes of subjects discharged to home, transferred to the ICU, or death are shown in Table 2. Except for sex and BMI, all studied variables were related to home discharge. Of note, significant differences between discharged to home and transferred to ICU groups were found in median LOS in the SWC (59 [37–86] d vs 36 [12–77] d, respectively, P = .003), mechanical ventilation duration (10 [5–20] d vs 15 [7–31] d, respectively, P < .001), and tracheostomy decannulation (96.7% vs 3.3%, respectively, P < .001). In multivariate analysis, both age and Charlson comorbidity index as well as mechanical ventilation duration in the ICU, renal failure at SWC admission, and weakness of expiratory muscles were independently associated with home discharge (Table 3). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test indicated a good model fit (P = .11).

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis for Home Discharge Versus Transferred to ICU or Death

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Analysis With Complete Case Analysis

Figure 2 shows a Kaplan-Meier plot of home discharge in decannulated and non-decannulated subjects up to 6 months follow-up in SWCs. The proportion of subjects who remained at the SWC up to 6 months was 71% for non-decannulated subjects and 8% for those who were decannulated (P < .001).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot of home discharge in decannulated and non-decannulated subjects up to 6 months follow-up in specialized weaning centers. SWC = specialized weaning center.

Data Sharing

These data will be available to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal, for any purpose of analysis. Proposals should be directed to dariovillalba79@gmail.com. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Discussion

In the present study, most subjects with COVID-19 transferred from ICUs to SWCs were weaned, achieved decannulation, and were discharged to home. During the pandemic, SWCs reduced acute care occupancy and allowed many patients transferred from the ICU to rehabilitate. Age, high comorbidity burden, prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU, renal failure at admission, and expiratory muscle weakness were inversely associated with home discharge. The overall weaning success rate was 72.4%, while SWC mortality was 6.0% (Table 1). These data are remarkably similar to those found in other studies.5,6,11 There are different criteria around the world regarding home discharge; therefore, patients are referred to step-down centers to continue decannulation and rehabilitation once being weaned. We must point out that many SWCs do not report decannulation frequency.5,6,11 The decannulation rate in the present study was 75.2%. This rate seems to be substantially higher than those reported in the ICU setting.23 However, heterogeneity between groups makes it difficult to interpret this difference as plausible.

A retrospective and comparative study from a single-center5 reported on 117 subjects after the acute COVID-19 phase at an LTACH. Only 43 (36%) had a tracheostomy, while 16 received prolonged mechanical ventilation. Ninety-four percent (15/16) of subjects were weaned, and a total of 46% were discharged home. The authors did not mention how many subjects were decannulated, and the mortality rate was not reported. Another retrospective cohort study11 examined 138 subjects without COVID-19 and 37 subjects admitted for COVID-19 in a unique medical center. Weaning success was 83%, while 22% were discharged home. Mortality was 8%. The authors did not provide information about decannulation. The study suggests that subjects with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy may have a higher chance of recovery than those without COVID-19. A bi-center prospective study6 was designed to describe 158 post-acute subjects with COVID-19 receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation transferred to 2 LTACHs. Weaning success was 71%, mortality was 10%, and 19% of subjects were discharged home. The authors did not report decannulation rates.

Up to 6.52 billion people live in low- and middle-income countries.24 However, even when COVID-19 reached worldwide pandemic proportions, to our knowledge no information was found regarding SWCs in these regions. Our multi-center study was designed to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of adult, post-acute, tracheostomized, subjects with COVID-19 with or without invasive ventilation in Argentina. Most subjects were male, around 60 y old, overweight, and had a low comorbidity burden (Table 1). These findings are similar to those reported by Grevelding et al5 and Saad et al.6

SWCs with comprehensive rehabilitation programs beyond ventilator management are available in Argentina, and patients can remain hospitalized even after being weaned. However, if the infrastructure outside of SWCs or home care is insufficient to achieve the best possible rehabilitation for the patient, SWC discharge may be delayed until out-patient rehabilitation is reasonably feasible. For this reason, comparing our results with those of other authors might not be feasible.5,6,11 Furthermore, SWC admission criteria usually include clinical stability allowing discharge from the ICU, device dependence (invasive mechanical ventilation via a tracheostomy tube), and functional limitations with care dependence. These requirements make home discharge from the ICU difficult due to barriers in the home-based care system in our country. In other countries, once patients are weaned from mechanical ventilation, they are transferred to non-ICU facilities. The same occurs when those patients require prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation. In Argentina, SWCs are engaged in rehabilitation for both weaning and decannulation process. The ideal key factor for home discharge in our setting is achieving decannulation, which is in line with other non-COVID-19 reports.25–27 Some patients who achieve their rehabilitation goals still need mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy. They usually go home with these devices and get home care. They can rarely stop using ventilators and tracheostomy in this situation.

In our country, the number of SWCs has doubled within the last decade; and during the outbreak, they were able to extend ICU capacity for COVID-19 recovery. Data on the relationship between ICUs and SWCs and their geographical distribution would be relevant in large countries like Argentina. This study can be considered representative, since most of the participating institutions are located in the metropolitan area of the city of Buenos Aires and its surroundings, corresponding to the area of the highest population density of the country.28 Thus, the distribution of the centers follows population and not geography.

As expected, we found that age, high comorbidity burden, and prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU were inversely associated with home discharge (Table 3). Although this study was not carried out with the primary objective of building a prediction model, renal failure at admission was associated with a decrease in home discharge. However, the relevance of renal failure as a predictor warrants further research. Similarly, expiratory muscle weakness measured at admission to the SWCs was associated with a lower home discharge rate. Although it has previously been characterized as a significant element for weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation,29 its relationship with home discharge deserves more attention.

Despite the prospective multi-center epidemiologic nature and the consecutive sampling in which every subject who met inclusion criteria was included, thus avoiding selection bias, our study is not without certain limitations. First, despite a lack of probability sampling design of the SWCs, we included > 70% of Argentinian rehabilitation and weaning centers. Second, a large number of data entries across centers could have generated information bias. Instead, data were collected in digital forms through a well-known web-design data collection software. This minimized missing data and improved the internal validity of the research. Lastly, not all SWCs used their own established weaning and decannulation protocol. However, we found no difference between outcomes in facilities with or without formal protocols, and distribution across centers was comparable. Finally, there were no data available from the ICU such as ICU infections, general illness severity scores, and frequency of prone position cycles since this information is often not provided on the ICU discharge summary.

Conclusions

In Argentina, an upper-middle-income country, subjects with COVID-19 who survived to ICU discharge and were admitted to an SWC showed compelling recovery. Most were successfully weaned, decannulated, and discharged home. However, many such patients may still require additional medical care. Care of patients with COVID-19 is a new challenge for all countries.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this paper is available at http://www.rcjournal.com.

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Al Sulaiman KA, Aljuhani O, Eljaaly K, Alharbi AA, Al Shabasy AM, Alsaeedi AS, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multi-center cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2021;105:180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395(10223):497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reddy SGK, Mantena M, Garlapati SKP, Manohar BP, Singh H, Bajwa KS, Tiwari H. COVID-2019-2020-2021: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2021;13(Suppl 2):S921–S926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schäfer H, Michels IC, Bucher B, Dock-Rust D, Hellstern A. Entwöhnung von der Beatmung (Weaning) nach Langzeitbeatmung infolge SARS-CoV-2-Infektion. Pneumologie 2021;75(4):261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grevelding P, Hrdlicka HC, Holland S, Cullen L, Meyer A, Connors C, et al. Patient outcomes and lessons learned from treating patients with severe COVID-19 at a long-term acute care hospital: single-center retrospective study. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2022;9(1):e31502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saad M, Laghi FA, Jr, Brofman J, Undevia NS, Shaikh H. Long-term acute care hospital outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med 2022;50(2):256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Estenssoro E, Reina R, Canales HS, Saenz MG, Gonzalez FE, Aprea MM, et al. The distinct clinical profile of chronically critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care 2006;10(3):R89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rose L, Fraser IM. Patient characteristics and outcomes of a provincial prolonged-ventilation weaning center: a retrospective cohort study. Can Respir J 2012;19(3):216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Damuth E, Mitchell JA, Bartock JL, Roberts BW, Trzeciak S. Long-term survival of critically ill patients treated with prolonged mechanical ventilation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3(7):544–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scheinhorn DJ, Hassenpflug MS, Votto JJ, Chao DC, Epstein SK, Doig GS, et al. ; Ventilation Outcomes Study Group. Ventilator-dependent survivors of catastrophic illness transferred to 23 long-term care hospitals for weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest 2007;131(1):76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dolinay T, Jun D, Chen L, Gornbein J. Mechanical ventilator liberation of patients with COVID-19 in long-term acute care hospital. Chest 2022;161(6):1517–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sociedad Argentina de Terapia Intensiva. Análisis de situación del COVID-19 en terapias intensivas de argentina. Available at: https://www.sati.org.ar. Accessed June 2022.

- 13. Estenssoro E, Loudet CI, Ríos FG, Kanoore Edul VS, Plotnikow G, Andrian M, et al. ; SATI-COVID-19 Study Group. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 in Argentina (SATICOVID): a prospective, multi-center cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9(9):989–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villalba D, Plotnikow G, Feld V, Rivero Vairo N, Scapellato J, Díaz Nielsen E. Weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation at 72 hours of spontaneous breathing. Medicina (B Aires) 2015;75(1):11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Vito EL. The South American perspective. In: Ventilatory support for chronic respiratory failure, Vol 225. Ambrosino N, Goldstein RS, editors. New York: Informa; 2008:543–547. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173(5):489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. MacIntyre NR, Epstein SK, Carson S, Scheinhorn D, Christopher K, Muldoon S; National Association for Medical Direction of Respiratory Care. Management of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: report of an NAMDRC consensus conference. Chest 2005;128(6):3937–3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Evans JA, Whitelaw WA. The assessment of maximal respiratory mouth pressures in adults. Respir Care 2009;54(10):1348–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Béduneau G, Pham T, Schortgen F, Piquilloud L, Zogheib E, Jonas M, et al. ; WIND (Weaning according to a New Definition) Study Group and the REVA (Réseau Européen de Recherche en Ventilation Artificielle) Network. Epidemiology of weaning outcome according to a new definition. The WIND study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195(6):772–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Villalba D, Gil Rossetti G, Scrigna M, Collins J, Rocco A, Matesa A, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for mechanical ventilation reinstitution in patients weaned from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Respir Care 2020;65(2):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burger SV. Introduction to machine learning with R: rigorous mathematical analysis. O'Reilly Media, Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferro A, Kotecha S, Auzinger G, Yeung E, Fan K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of tracheostomy outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;59(9):1013–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Bank. Low & middle income countries. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/XO. Accessed May 2022.

- 25. Diaz Ballve P, Villalba D, Andreu M, Escobar M, Morel Vulliez G, Lebus J, et al. Decanular. Factores predictores de dificultad para la decanulación. Estudio de cohorte multicéntrico. Rev Am Med Respir 2017;17(1):12–24. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scrigna M, Plotnikow G, Feld V, Villalba D, Quiroga C, Leiva V, et al. Decanulación después de la estadía en UCI: Análisis de 181 pacientes traqueotomizados. Rev Am Med Respir 2013;13(2):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heidler MD, Salzwedel A, Jöbges M, Lück O, Dohle C, Seifert M, et al. Decannulation of tracheotomized patients after long-term mechanical ventilation – results of a prospective multi-centric study in German neurological early rehabilitation hospitals. BMC Anesthesiol 2018;18(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buenos Aires Ciudad. ¿Qué es AMBA? El Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires. Available at: https://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/gobierno/unidades%20de%20proyectos%20especiales%20y%20puerto/que-es-amba. Accessed June 2022.

- 29. Lin SJ, Jerng JS, Kuo YW, Wu CL, Ku SC, Wu HD. Maximal expiratory pressure is associated with reinstitution of mechanical ventilation after successful unassisted breathing trials in tracheostomized patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Plos ONE 2020;15(3):e0229935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.