Abstract

Background

Vitamin D deficiency is widely prevalent among the elderly, posing significant health risks. This study aims to determine the global prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted, examining databases including Scientific Information Database (SID), Medline (PubMed), ScienceDirect, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar until January 2023. The publication bias of the studies was assessed using the I2 test of heterogeneity and the Egger test.

Results

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, defined as levels below 20 ng or 50 nmol was found to be 59.7% (95% CI 45.9–72.1). Furthermore, a review of six studies involving 6748 elderly individuals showed a prevalence of 27.5% (95% CI 21.8–34.1) for deficiency defined between 20 and 30 ng or 50–75 nmol. Additionally, a meta-analysis of seven studies with a sample size of 6918 elderly individuals reported a prevalence of 16% (95% CI 10.2–24.1) for deficiency defined above 30 nmol or 75 nmol.

Conclusion

The results of the present study reveal that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among the elderly is high and requires the attention of health policymakers at the World Health Organization to prioritize extensive information dissemination and screening to mitigate the adverse effects on their quality of life.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43465-023-01089-w.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Quality of life, Elderly, Meta-analysis

Background

Old age refers to a stage in life where individuals experience a significant decline in former abilities and functions to a significant extent and goes through the process of exhaustion and the end of life [1]. Based on the definition by the World Health Organization, individuals aged over 60 years old and above are classified as elderly [2]. Projections indicate a global population of 893 million elderly individuals and this number is increasing [3].

The aging process brings forth various physical, mental, functional, and social changes and challenges. This can include all kinds of hearing and vision impairments, dizziness, muscular ailments, osteoporosis, increased susceptibility to dementia, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases, compromised immune function, the emergence of various cancers and chronic diseases, osteoarthritis, urological changes, heightened risk of depression, and reduced mobility [4].

One of the most common vitamin deficiencies in the world, especially among the elderly, is vitamin D deficiency, which is considered a significant risk factor [5]. Vitamin D deficiency has become a global concern; studies indicate a deficiency in 30–50% of the world’s population [6].

This vitamin, categorized as fat soluble serves as a precursor to the hormonal form, calcitriol [7, 8]. This vitamin is mostly found in the form of D3 (cholecalciferol) and D2 (ergocalciferol). Sources of vitamin D include foods like cow's liver, eggs, cheese, fish liver oil, mushrooms, deer lichen, etc., and its synthesis is influenced by ultraviolet rays from sunlight on the skin [9]. The quantity of this vitamin is closely linked to lifestyle and environmental factors. Therefore, individuals with more melanin in their skin require more sunlight exposure to produce the same amount of vitamin compared to individuals with lighter skin [10].

This vitamin plays a crucial role in the calcium absorption and maintaining calcium homeostasis [11]. Additionally, it contributes to enhancing muscle function [12–14] and strengthening the immune system [15]. The level of vitamin D is assessed by measuring 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) levels in plasma. Lack of vitamin D signals potential such as osteoporosis, breast cancer, prostate, colon, and type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disorders in the elderly [16].

One of the causes of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly is the reduction in the consumption of sources containing this vitamin and the accumulation of the storage form of the vitamin in fat tissue. However, research suggests that the primary cause is the deficiency of 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) in the epidermal layer of the skin [17]. With increasing life expectancy and growing elderly population requiring additional care, coupled with the lack of consistent information regarding the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly, this study aims to determine the global prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among the elderly through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

A systematic search for articles was conducted across multiple databases including PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Embase SID, and Google Scholar. The keywords used for searching in this study were selected based on previously published primary studies and MESH terms. Both English and Farsi keywords were included, focusing on terms such as vitamin D, quality of life, elderly, and meta-analysis. The search was conducted in various databases without any time restrictions up until January 2023. This review considered cross-sectional and observational studies while excluding case studies, clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Data Extraction and Data Analysis

Following the database search, collected studies were imported into EndNote software. Initial assessment of these articles was independently conducted by two authors. Subsequently, a secondary review of these studies was conducted by reviewing the titles and abstracts of the articles in accordance with the predetermined inclusion criteria. The quality appraisal of the studies, focusing on investigating the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly was performed using the STROBE checklist. This checklist allows for scores ranging from checklist is 0–32. In this study, articles with a score of 16 and above were included in the meta-analysis as good-quality studies. The information extracted from the studies was entered into the Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA, Version 2.0) software. Additionally, publication bias in the studies was also analyzed by the Egger test and funnel plot.

Results

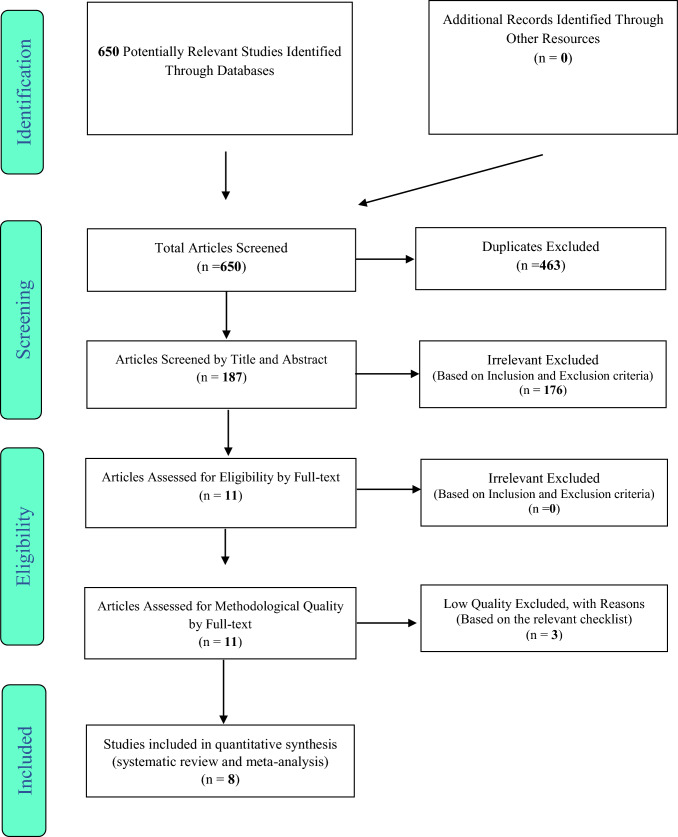

In the review and search across all the databases, a total of 650 articles were initially retrieved. After removing irrelevant duplicates and applying the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, a final selection of eight articles was included for the review (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Steps of entering studies into systematic review and meta-analysis based on the PRISMA model

Table 1.

Information extracted from the studies

| Unit | Author/s | Year | Age | Sample size | Prevalence | Quality assessment score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below 20 ng or 50 nmol | Jong J. Neo [18] | 2016 | Above 65 | 134 | 44 | 27 |

| Sapneet Kaur [19] | 2020 | Above 60 | 150 | 67.3 | 25 | |

| Sun Hea Kim [20] | 2018 | Above 65 | 2687 | 62.1 | 27 | |

| Ling Liu [21] | 2020 | Above 65 | 2493 | 41.3 | 22 | |

| Justyna Nowak [22] | 2021 | Above 65 | 242 | 79.8 | 26 | |

| Between 20 and 30 ng or 50 and 75 nmol | Jong J. Neo [18] | 2016 | Above 65 | 134 | 41.8 | 29 |

| Sapneet Kaur [19] | 2020 | Above 60 | 150 | 18.6 | 20 | |

| Ling Liu [21] | 2020 | Above 65 | 2493 | 35.7 | 23 | |

| Justyna Nowak [22] | 2021 | Above 60 | 242 | 19 | 21 | |

| DavidJ. Llewellyn [23] | 2011 | Above 65 | 3396 | 39 | 25 | |

| Maria Samefors [24] | 2014 | Above 65 | 333 | 15.3 | 25 | |

| Below 30 nmol or 75 nmol | Chi-Hsien Huang [25] | 2017 | Above 65 | 170 | 55.9 | 19 |

| Above 30 nmol or 75 nmol | Jong J. Neo [18] | 2016 | Above 65 | 134 | 14.2 | 20 |

| Sapneet Kaur [19] | 2020 | Above 60 | 150 | 14 | 26 | |

| Ling Liu [21] | 2020 | Above 65 | 2493 | 23 | 28 | |

| Justyna Nowak [22] | 2021 | Above 60 | 242 | 1.2 | 25 | |

| DavidJ. Llewellyn[23] | 2011 | Above 65 | 3396 | 37.5 | 21 | |

| Maria Samefors [24] | 2014 | Above 65 | 333 | 4.5 | 18 | |

| Chi-Hsien Huang [25] | 2017 | Above 65 | 170 | 44.1 | 22 |

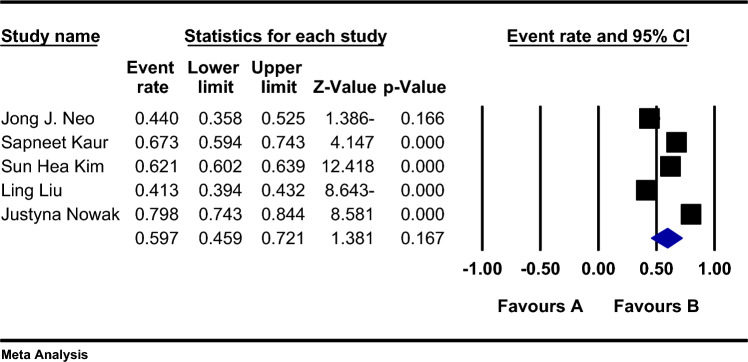

Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency Based on Units Below 20 ng or 50 nmol

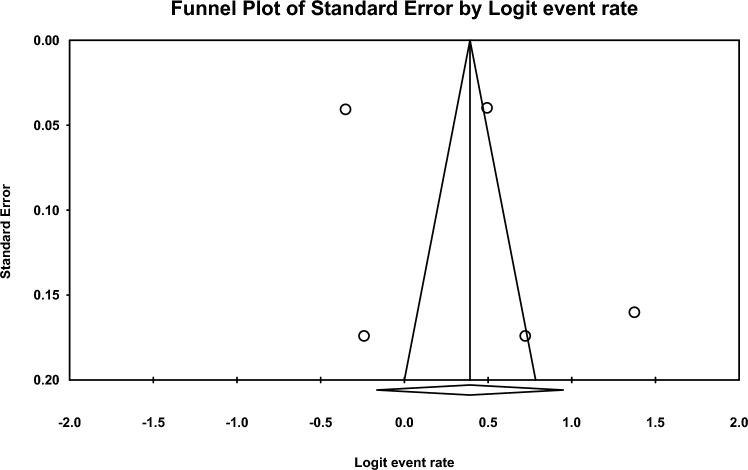

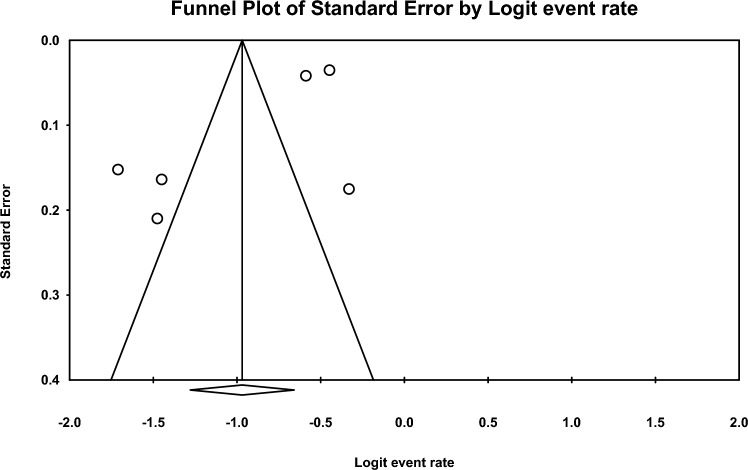

In the assessment of five studies involving a total sample size of 5706 elderly individuals, the I2 heterogeneity test indicated substantial heterogeneity (I2: 98.6). Based on the meta-analysis, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, defined as levels below 20 ng or 50 nmol was found to be 59.7% (95% CI 45.9–72.1) (Fig. 2). Analysis of publication bias within these studies yielded non-significant results (p = 0.623) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency based on the unit below 20 ng or 50 nmol

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of the reviewed studies

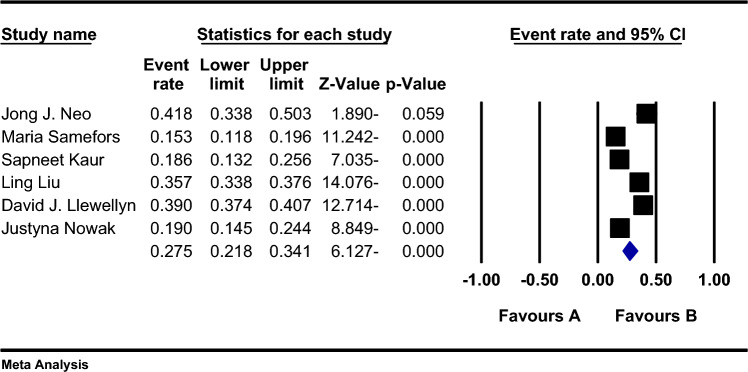

Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency per Unit Between 20 and 30 ng or 50–75

In the evaluation of six studies with a sample size of 6748 elderly individuals, the I2 heterogeneity test indicated considerable heterogeneity (I2: 95.7). The meta-analysis revealed a prevalence of 27.5% (95% CI 21.8–34.1) for vitamin D deficiency within the range of 20–30 ng or 50–75 nmol (Fig. 4). The analysis of publication bias within these studies yielded non-significant results (p = 0.075) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency based on the unit between 20 and 30 ng or 50–75 ng

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot of the reviewed studies

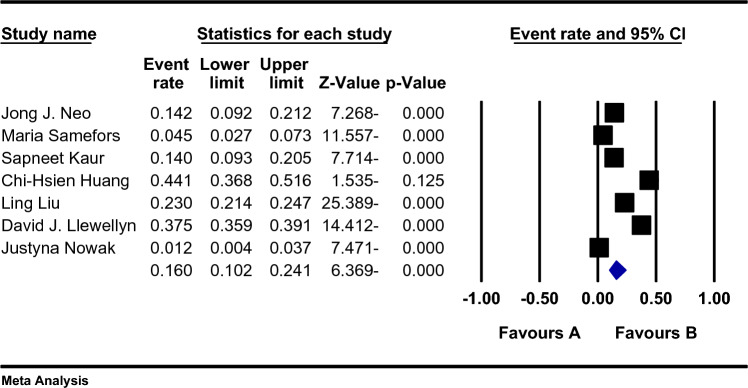

Prevalence of Vitamin D Deficiency Based on Units Above 30 nmol or 75 nmol

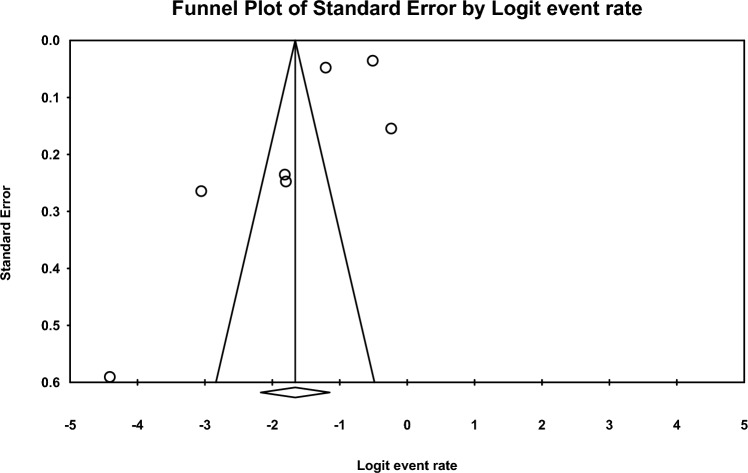

In the assessment of seven studies involving a sample size of 6918 elderly individuals, the I2 heterogeneity test showed substantial heterogeneity (I2: 97.9). The reported prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, defined as levels above 30 nmol or 75 nmol, was 16% (95% CI 10.2–24.1) (Fig. 6). Analysis of publication bias within the studies yielded non-significant results (p = 0.140) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency based on units above 30 nmol or 75 nmol

Fig. 7.

Funnel plot of the reviewed studies

Discussion

Vitamin D deficiency is a prominent global health concern [26], notably prevalent among the elderly [27]. Research indicates a prevalence of 40–100% among elderly populations in America and Europe [28, 29].

The prevalence of the deficiency of vitamin D in rural areas of Taiwan is reported to be 44% [30], while in some areas of China, rates of 55.9% below 20 ng/ml and 38.7% within the range of 20 and 30 ng per ml have been reported [31].

In other regions of China, 69.2% deficiency below 20 ng/ml and 24.4% within 20–30 ng/ml have been reported [32]. Similarly, Thailand reported a prevalence of 46.7% [33]. In Goh et al.’s study, the results showed that the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in hospitalized elderly is 40.8% below 20 ng/ml and 27.7% within 20 and 29.9 ng/ml [34].

Several factors affect the levels of vitamin D, including socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and skin color contributing to heightened susceptibility to vitamin D deficiency [35]. Aging processes, coupled with inadequate nutrition and exercise, may lead to digestive, liver, and kidney complications, thus increasing the risk of vitamin D deficiency [36].

Vitamin D deficiency is related to autoimmune diseases [37], affecting the functionality of endocrine glands [38]. Low vitamin D levels is associated with various conditions such as bladder and colon cancers, migraine headaches, and diabetic retinopathy [39–42].

The results of studies have shown that vitamin D has an inverse relationship with cholesterol levels and a direct relationship with HDL-C and plays a significant role in the formation of HDL-C [43, 44]. Research further establishes the link between vitamin D deficiency and sarcopenia in the elderly [45]. The absence of vitamin D receptors in the elderly is suggested to disturb their muscle contraction process [46]. Moreover, it can lead to mitochondrial function defects and reduce superoxide dismutase levels (SOD) [47].

Limitations

One of the most important limitations of the present study was the authors’ inability to access the Web of Sciences database. To compensate for this limitation, the authors expanded their search across similar databases and thoroughly examined the references of the obtained articles.

Conclusions

Conclusively, vitamin D deficiency among the elderly is a crucial factor contributing to disease susceptibility and mortality. However, addressing and treating this deficiency demand new strategies and solutions. These include raising public awareness regarding the significance of vitamin D in maintaining health, adapting lifestyle behaviors, augmenting intake of vitamin D rich substances, considering vitamin supplements, and emphasizing controlled exposure to sunlight among the elderly.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study is the result of research project No. 401000025 approved by the Student Research Committee of Gerash University of Medical Sciences. We would like to thank the esteemed officials of the center for the financial affords of this study.

Author Contributions

MM, AM, and FB contributed to the design. MM did statistical analysis and participated in most of the study steps. AH and MM prepared the manuscript. AAK and MM assisted in designing the study and helped in the interpretation of the study. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Funding

By Deputy for Research and Technology, Gerash University of Medical Sciences (IR) (401000025). This deputy had no role in the study process.

Availability of Data and Materials

Datasets are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethics approval was received from the Ethics Committee of the Deputy of Research and Technology, Gerash University of Medical Sciences (401000025).

Ethical Standard Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sheybani F, Pakdaman SH, Dadkhah A, Hasanzadeh-Tavakkoli MR. The impact of music therapy on depression and loneliness of elderly. Salmand Iran J Ageing. 2010;16:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Social development and ageing: Crisis or opportunity. World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Population Ageing. (2009). United Nations. 2009.

- 4.Jaul E, Barron J. Age-related diseases and clinical and public health implications for the 85 years old and over population. Frontiers in Public Health. 2017;5:335. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng X, Guo T, Wang Y, Kang D, Che X, Zhang H, Cao W, Wang P. The vitamin D status and its effects on life quality among the elderly in Jinan, China. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2016;62:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, O'Keefe JH, Bell D, Hensrud DD, Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency an important, common, and easily treatable cardiovascular risk factor? Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52(24):1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang R, Naughton DP. Vitamin D in health and disease: current perspectives. Nutrition Journal. 2010;9:65. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Verlinden L, van Etten E, Verstuyf A, Luderer HF, Lieben L, Mathieu C, Demay M. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocrine Reviews. 2008;29(6):726–776. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benedik E. Sources of vitamin D for humans. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 2022;92(2):118–125. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rostand SG. Ultraviolet light may contribute to geographic and racial blood pressure differences. Hypertension. 1997;30:150–156. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.30.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(3):266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(1):18–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1689S–S1696. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, Daniel KC, Berti E, Colonna M, et al. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 2005;106(10):3490–3497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sulli A, Gotelli E, Casabella A, Paolino S, Pizzorni C, Alessandri E, Grosso M, Ferone D, Smith V, Cutolo M. Vitamin D and lung outcomes in elderly COVID-19 patients. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):717. doi: 10.3390/nu13030717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosekilde L. Vitamin D and the elderly. Clinical endocrinology. 2005;62(3):265–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacLaughlin J, Holick MF. Aging decreases the capacity of human skin to produce vitamin D3. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1985;76:1536–1538. doi: 10.1172/JCI112134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neo JJ, Kong KH. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation unit in tropical Singapore. Rehabilitation Research and Practice. 2016;2016:9689760. doi: 10.1155/2016/9689760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaur S, Kaur H, Bhatia AS. Prevalence of Vitamin D deficiency among the urban elderly population in Jammu. JMSCR. 2020;8(3):284–287. doi: 10.18535/jmscr/v8i3.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SH, Oh JE, Song DW, Cho CY, Hong SH, Cho YJ, Yoo BW, Shin KS, Joe H, Shin HS, Son DY. The factors associated with Vitamin D deficiency in community dwelling elderly in Korea. Nutrition Research and Practice. 2018;12(5):387–395. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2018.12.5.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, Cao Z, Lu F, Liu Y, Lv Y, Qu Y, Shi X. Vitamin D deficiency and metabolic syndrome in elderly Chinese individuals: evidence from CLHLS. Nutrition and Metabolism. 2020;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12986-020-00479-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak J, Hudzik B, Jagielski P, Kulik-Kupka K, Danikiewicz A, Zubelewicz-Szkodzińska B. Lack of seasonal variations in vitamin D concentrations among hospitalized elderly patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1676. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Langa KM, Melzer D. Vitamin D and cognitive impairment in the elderly US population. The Journal of Gerontology. 2011;66(1):59–65. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samefors M, Östgren CJ, Mölstad S, Lannering C, Midlöv P, Tengblad A. Vitamin D deficiency in elderly people in Swedish nursing homes is associated with increased mortality. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2014;170(5):667–675. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang CH, Huang YA, Lai YC, Sun CK. Prevalence and predictors of hypovitaminosis D among the elderly in subtropical region. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0181063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urvashi M, Singh P, Pande S. Current status of vitamin D deficiency in India. IPP. 2014;2(2):328–335. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lips P. Vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly: Consequences for bone loss and fractures and therapeutic implications. Endocrine Reviews. 2001;22:477–501. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.4.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapuy MC, Preziosi P, Maamer M, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in an adult normal population. Osteoporos International. 1997;7:439–443x. doi: 10.1007/s001980050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lips P, Hosking D, Lippuner K, et al. The prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy amongst women with osteoporosis: An international epidemiological investigation. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2006;260:245–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, Burckhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B, Eisman JA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Josse RG, Lips P, Morales-Torres J, IOF Committee of Scientific Advisors (CSA) Nutrition Working Group Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporosis International. 2009;20(11):1807–1820. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0954-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu S, Fang H, Han J, Cheng X, Xia L, Li S, et al. The high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in China: A multicenter vitamin D status survey. Medicine. 2015;94(8):e585. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu L, Yu Z, Pan A, Hu FB, Franco OH, Li H, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and metabolic syndrome among middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):127883. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chailurkit LO, Aekplakorn W, Ongphiphadhanakul B. Regional variation and determinants of vitamin D status in sunshine-abundant Thailand. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:853. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goh KS, Zhang D, Png GK, et al. Vitamin D status in elderly inpatients in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(7):1398–1400. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nesby-O’Dell S, Scanlon KS, Cogswell ME, Gillespie C, Hollis BW, Looker AC, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76:187–192. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson KE, Abrolat ML, Malone LL, Hoeg JM, Doherty T, Detrano R, et al. Active serum vitamin D levels are inversely correlated with coronary calcification. Circulation. 1997;96(6):1755–1760. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.6.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prietl B, Treiber G, Pieber TR, Amrein K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients. 2013;5:2502–2521. doi: 10.3390/nu5072502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S, Kim DS, Kang S. Vitamin D deficiency impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and increases insulin resistance by reducing PPAR-γ expression in nonobese type 2 diabetic rats. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2016;27:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gungor A, Ates O, Bilen H, Kocer I. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in early-stage diabetic retinopathy with Vitamin D deficiency. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2015;56:6433–6437. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mottaghi T, Askari G, Khorvash F, Maracy MR. Effect of Vitamin D supplementation on symptoms and C-reactive protein in migraine patients. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2015;20:477–482. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.163971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H, Zhang H, Wen X, Zhang Y, Wei X, Liu T, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and increased risk of bladder carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2015;37:1686–1692. doi: 10.1159/000438534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marques Vidigal V, Aguiar Junior PN, Donizetti Silva T, de Oliveira J, Marques Pimenta CA, Vitor Felipe A, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of Vitamin D metabolism genes and serum level of Vitamin D in colorectal cancer. International Journal of Biological Markers. 2017;32:e441–e446. doi: 10.5301/ijbm.5000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rye KA, Bursill CA, Lambert G, Tabet F, Barter PJ. The metabolism and antiatherogenic properties of HDL. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50:S195–200. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800034-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kazlauskaite R, Powell LH, Mandapakala C, Cursio JF, Avery EF, Calvin J. Vitamin D is associated with atheroprotective high-density lipoprotein profile in postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2010;4(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abiri B, Vafa MR. Vitamin D and sarcopenia. Advances in Obesity, Weight Management and Control. 2017;6:00155. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Borchers M, Gudat F, Dürmüller U, Stähelin HB, Dick W. Vitamin D receptor expression in human muscle tissue decreases with age. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19:265–269. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2004.19.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhat M, Ismail A. Vitamin D treatment protects against and reverses oxidative stress induced muscle proteolysis. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2015;152:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Datasets are available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request.