Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been a major challenge worldwide for the past years with high morbidity and mortality rates. While vaccination was the cornerstone to control the pandemic and disease spread, concerns regarding safety and adverse events (AEs) have been raised lately. A cross-sectional study was conducted between January 1st and January 22nd, 2022, in six Arabic countries namely Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Syria, Libya, Iraq, and Algeria. We utilized a self-administered questionnaire validated in Arabic which encompassed two main parts. The first was regarding sociodemographic data while the second was about COVID-19 vaccination history, types, doses, and experienced AEs. A multistage sampling was employed in each country, involving the random selection of three governorates from each country, followed by the selection of one urban area and one rural area from each governorate. We included the responses of 1564 participants. The most common AEs after the first and second doses were local AEs (67.9% and 46.6%, respectively) followed by bone pain and myalgia (37.6% and 31.8%, respectively). After the third dose, the most common AEs were local AEs (45.7%) and fever (32.4%). Johnson and Johnson, Sputnik Light, and Moderna vaccines showed the highest frequency of AEs. Factors associated with AEs after the first dose included an increase in age (aOR of 61–75 years compared to the 12–18 years group: 2.60, 95% CI: 1.59–4.25, p = 0.001) and male gender (OR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.63–0.82, p < 0.001). The cumulative post-vaccination COVID-19 disease was reported with Sinovac (16.1%), Sinopharm (15.8%), and Johnson and Johnson (14.9) vaccines. History of pre-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection significantly increases the risk of post-vaccination COVID-19 after the first, second, and booster doses (OR: 3.09, CI: 1.9–5.07, p < 0.0001; OR: 2.56, CI: 1.89–3.47, p < 0.0001; and OR: 2.94, CI: 1.6–5.39, p = 0.0005 respectively). In conclusion, AEs were common among our participants, especially local AEs. Further extensive studies are needed to generate more generalizable data regarding the safety of different vaccines.

Keywords: Adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Vaccination, Arab Populations

Subject terms: Vaccines, Health care, Medical research, Signs and symptoms

Introduction

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic poses a significant global health challenge, with over 772 million confirmed cases and around seven million deaths as of 30 November 2023, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)1. Vaccination has emerged as the most promising intervention to control the pandemic2. By the beginning of 2021, numerous vaccine candidates had received emergency use authorization (EUA), and countries had preordered more than 10 billion vaccine doses by December 20203. Globally, as of 22 November 2023, more than 13 billion vaccine doses have been administered1.

Although the standard timeline for vaccine development is 10–14 years, numerous COVID-19 vaccines have been created during this unusual period of accelerated clinical progress4,5. They have been developed using different technological platforms, including mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, adenovirus vector vaccines such as AstraZeneca, Sputnik V, and Janssen, and inactivated killed vaccines like Sinopharm6–8. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends COVID-19 vaccination for all eligible individuals, regardless of their status of previous infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), as vaccines have shown high efficacy in preventing hospitalization, severe illness, and death2,9.

However, vaccine hesitancy and refusal remain significant challenges that combat the vaccination process of different pandemics2,10. Regarding COVID-19, vaccination acceptance rates varied widely across countries, with rates of 69% in some regions but as low as 11% in others. This variability can be attributed to factors such as vaccine availability, mandatory vaccination policies, public knowledge and attitudes towards vaccines, perceived effectiveness and cost, and experience of adverse events following immunization (AEFI) with COVID-19 vaccines2,11–14. The WHO defined COVID-19 AEFI as "any untoward medical occurrence which follows immunization and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the usage of the vaccine". AEFI can be categorized into five groups: vaccine product-related events, vaccine quality-related events, immunization error-related events, immunization-induced stress, and coincidental category, which has no direct relationship with the vaccine or any of the above but occurs soon after vaccination and hence may be attributed to it nonetheless9,15.

Generally, vaccine adverse events (AEs) occur within six weeks of vaccination and typically resolve within a few days in both children and adults14,16,17. Therefore, monitoring the COVID-19 vaccine for eight weeks after the final dose is recommended. After a vaccine is licensed, the CDC and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) utilize a passive reporting system named the Vaccination Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) to conduct post-licensure surveillance to collect, monitor, and analyze reports of post-COVID-19 vaccination AEs9,15,18,19. Health institutions should continuously monitor, and report AEs associated with vaccines and medications to the relevant authorities through healthcare professionals20. Although adequate safety and efficacy of vaccines are the key elements for their licensure, the fast-tracking processes of vaccine development may heighten the risk of increased AEs as some data may go missing or unnoticed due to the accelerated process21,22. The faster approvals in the case of the COVID-19 vaccine compared to the conventional vaccine approval process is another important reason for hesitancy21.

To enhance public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines and establish trust in vaccine safety and understand potential adverse effects, clear and reliable information is essential. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) urged further research on the effects of COVID-19 vaccines12. Despite the WHO's call for high-quality research on the negative health, social, and economic effects of COVID-19 vaccines, conclusive evidence is still lacking, necessitating further investigation into the factors contributing to these effects2,11,23. Many observational studies were conducted to monitor or detect the AEs following COVID-19 vaccinations with a wide range of AE rates between 13 and 90%12,24–33. Fewer studies focusing only on one country, one province, or one area were performed in the Arab countries with most studies done in Saudi Arabia and Egypt33–41. Hence, this multicenter study aimed to explore the AEs of different types and doses of COVID-19 vaccines and identify associated factors among vaccinated participants in six Arabic countries.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the reported adverse effects (AEs) associated with different types and doses of COVID-19 vaccines among vaccinated participants in six Arabic countries. The secondary objective was to determine the potential factors associated with AEs, including demographic factors such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), pre-vaccination comorbidities, and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, we aimed to explore the cumulative incidence of post-vaccination COVID-19 with different vaccine types. Through comprehensive data analysis and exploration, this study aimed to contribute to the existing knowledge on the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines, improve public acceptance, and facilitate evidence-based discussions and interventions surrounding vaccine acceptance and potential adverse effects.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

Of the 1564 vaccinated participants, a total of 660 participants (42.2%) were between the ages of 19 and 30 years, 968 participants (61.9%) were females, 1286 participants (82.2%) had a university education or higher, and 1397 participants (89.3%) resided in urban areas. Additionally, 581 participants (37.1%) were housewives or unemployed, and Saudi Arabia had the highest response rate with 444 participants (28.4%). The mean BMI was found to be 30.2 ± 2.65 kg/m2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The sociodemographic date, and its relationship with the vaccine adverse effects.

| Variables | Total (N = 1564) F (%) * | The AE after the first dose of COVID-19 vaccination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AE (N = 335) F (%) | Local and /or general AEs (N = 1032) F (%) | Systemic, and/or serious AEs (N = 197) F (%) | P-value of χ2 test # | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 12–18 | 57 (3.6) | 6 (10.5) | 46 (80.7) | 5 (8.8) | |

| 19–30 | 660 (42.2) | 144(21.8) | 435(65.9) | 81(12.3) | |

| > 30–45 | 463 (29.6) | 87 (18.8) | 300 (64.8) | 76 (16.4) | < 0.001 |

| > 45–60 | 241 (15.4) | 55 (23.0) | 159 (66.0) | 27 (11.2) | |

| 61–75 | 112 (7.2) | 26 (23.2) | 80 (71.4) | 6 (5.8) | |

| > 75 | 31 (2.0) | 17 (54.8) | 12 (38.7) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 968 (61.9) | 148 (15.3) | 669 (69.1) | 151 (15.6) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 596 (38.1) | 187 (31.4) | 363 (60.9) | 46 (7.7) | |

| Education | |||||

| Read, write /primary | 44 (2.8) | 17 (38.9) | 25 (56.8) | 2 (4.5) | |

| Secondary /high | 234 (15.0) | 62 (26.5) | 145 (62.0) | 27 (11.5) | 0.006 |

| University or above | 1286 (82.2) | 258 (19.9) | 862 (67.0) | 168 (13.1) | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Unemployed | 581 (37.1) | 129 (22.2) | 380 (65.4) | 72 (12.4) | |

| Medical field | 547 (35.0) | 112 (20.5) | 370 (67.6) | 60 (13.8) | 0.83 |

| Other fields | 436 (27.9) | 94 (21.6) | 282 (64.7) | 65 (11.9) | |

| Residence | |||||

| Inside city (urban) | 1397 (89.3) | 290 (20.8) | 923 (66.4) | 184 (12.8) | 0.34 |

| Outside city (rural) | 167 (10.7) | 45 (29.6) | 104 (62.3) | 18 (10.8) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 30.2 ± 2.65 | (23.9 ± 9.4)a | (30.4 ± 7.9)b | (38.6 ± 7.8) | 0.04 ## |

| Country | |||||

| Saudi Arabia (SA) | 444 (28.4) | 55 (12.4) | 307 (69.1) | 82 (18.5) | |

| Egypt | 345 (22.0) | 84 (24.4) | 214 (61.9) | 47 (13.7) | |

| Libya | 218 (14.0) | 81 (37.2) | 121 (55.5) | 16 (7.3) | |

| Algeria | 213 (13.0) | 58 (27.5) | 144 (67.6) | 11 (5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Iraq | 183 (11.7) | 36 (19.7) | 126 (68.8) | 21 (11.5) | |

| Syria | 124 (7.9) | 16 (12.9) | 97 (78.2) | 7 (8.9) | |

| Others** | 37 (2.4) | 5 (13.5) | 23 ( 62.2) | 9 (24.3) | |

*Percentages of the total column are from the total of each dose. Otherwise, F (%) is calculated per column.

#P-value of χ2 chi square test. Significance level < 0.05.

##ANOVA (analysis of variance) test. Post-hoc test to show the least significance difference between the subgroups/ alphabetical letter of different symbols means a significant difference between groups.

** Others include 37 Sudan participants.

Regarding medical and medication history, the majority of vaccinated participants (70.0%) reported not taking any medications, and 1200 participants (76.7%) did not have any comorbidities. and 840 participants (53.7%) had no history of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection before vaccination. Out of the 510 participants (32.6%) who had experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection, 435 (85.3%) were managed at home. The majority of participants (72.9%) were vaccinated under mandatory vaccination policies while 889 (56.9%) received the vaccine in a vaccine center or hospital (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medical, medication and vaccination history and their relationships with the vaccine adverse effects.

| History | Total (N = 1564) F (%) * | The AE after the first dose of COVID-19 vaccination | P-value of χ2 test # | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AE (N = 335) F (%) | Local and /or general AEs (N = 1032) F (%) | Systemic, and/or serious AEs (N = 197) F (%) | |||

| Co-morbidities | |||||

| No | 1200 (76.7) | 254 (21.2) | 797 (66.4) | 149 (12.4) | |

| Psychiatric/neurological | 60 (3.8) | 5 (8.3) | 38 (63.3) | 17 (28.3) | 0.003 |

| Organic | 291 (18.6) | 73 (25.3) | 187 (64.9) | 28 (9.7) | |

| Both | 13 (0.8) | 3 (23.1) | 9 (69.2) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Drug intake | |||||

| None of the below | 1095 (70.0) | 234 (21.4) | 739 (67.5) | 122 (11.1) | |

| Supplements | 274 (17.5) | 51 (18.6) | 166 (60.9) | 57 (20.8) | 0.004 |

| Hormonal therapy | 104 (6.7) | 26 (25.0) | 68 (65.4) | 10 (19.6) | |

| Immune suppression medications | 40 (2.6) | 8 (20.0) | 27 (67.5) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Anti-coagulants | 51 (3.3) | 16 (31.4) | 32 (62.7) | 3 (5.9) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection before vaccination | |||||

| No | 840 (53.7) | 133 (15.8) | 594 (70.7) | 113 (13.5) | |

| Suspicious (symptoms) | 214 (13.7) | 110 (51.4) | 89 (41.6) | 15 (7.0) | |

| Yes, without symptoms | 56 (3.6) | 13 (23.3) | 35 (62.2) | 8 (14.3) | < 0.001 |

| Yes, managed at home | 435 (27.8) | 78 (18.1) | 229 (68.9) | 57 (13.1) | |

| Yes, managed at hospitals | 19 (1.2) | 1 (5.3) | 15 (78.9) | 3 (15.8) | |

| COVID-19 vaccination uptake | |||||

| Mandatory | 1136 (72.9) | 248 (21.8) | 766 (67.4) | 122 (10.7) | 0.74 |

| My choice | 428 ( 27.1) | 87 (20.3) | 266 (62.1) | 75 (17.5) | |

| Setting of COVID-19 vaccination uptake | |||||

| Mobile campaign | 98 (6.2) | 35 (35.7) | 50 (51.0) | 13 (13.3) | < 0.001 |

| Primary health care centers | 577 (36.9) | 141 (15.9) | 362 (62.7) | 56 (9.7) | |

| Vaccine center or hospital | 889 (56.9) | 159 (27.9) | 620 (69.7) | 128 (14.0) | |

*Percentages of the total column are from the total of each dose. Otherwise, F (%) is calculated per column.

#P-value of χ2 chi square test. Significance level < 0.05.

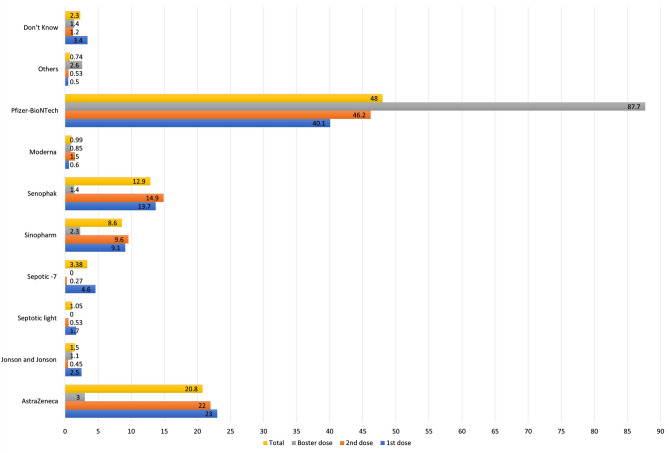

Out of the total 1564 participants who received the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 1325 (84.7%) completed the recommended two-dose regimen, while only 350 (22.4%) received the booster dose. In terms of vaccine types, out of the total 3239 vaccination doses administered, Pfizer-BioNTech was the most common, given in 1551 doses (48.0%), followed by AstraZeneca in 672 doses (20.8%), and Sinovac in 416 doses (12.9%). The percentages of each vaccine type at different doses among our participants are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The relative frequency distribution of different types of vaccinations at different doses.

Adverse effects post-COVID-19 vaccination

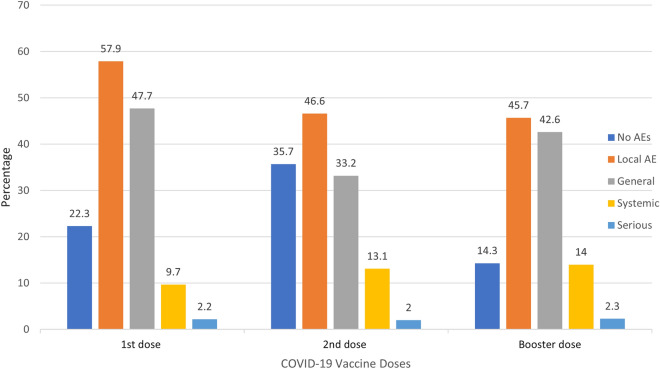

Overall, 1212 (77.7%) participants experienced an adverse event after the first COVID-19 dose, whereas 852 (64.3%) and 300 (85.7%) individuals had an adverse event following the second and booster doses respectively. For each dose, local AEs were the most experienced followed by general, systemic, and serious AEs (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The distribution of AEs after each vaccination dose.

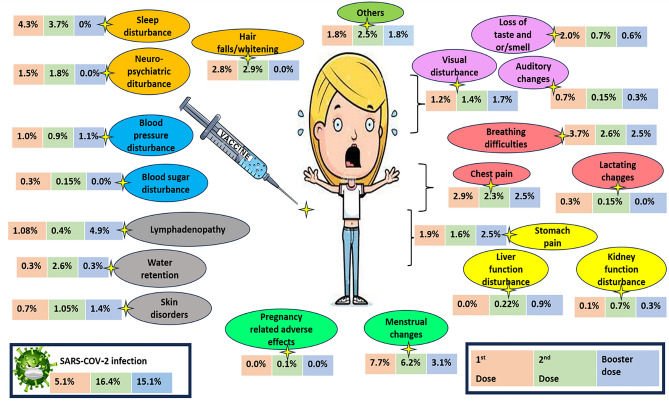

Regarding the occurrence of adverse effects (AEs) following COVID-19 vaccination, the most common AEs after the first dose were local AEs (57.9%) and fatigue (37.6%). After the second dose, the most common AEs were local AEs (46.6%) and fatigue (31.8%). Following the booster dose, the common AEs reported were local AEs in 160 participants (45.7%), fever in 82 participants (32.4%), and fatigue in 102 participants (30.0%). Approximately half of these AEs required no medical intervention, around half necessitated medical symptomatic treatment, and around 1% resulted in hospital admission. The details of the AEs among our participants are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

Table 3.

Adverse effects after COVID-19 vaccinations, and the required management.

| Adverse events (AEs) | 1st dose T = 1564 F (%) | 2nd dose T = 1325 F (%) | Booster dose ## T = 350 F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local adverse events (AEs) at the injection site | 906 (57.69) | 617 617 (46.6) | 160 160 (45.7) |

| General constitutional AEs | |||

| Fever /chills | 523 (33.4) | 401 (30.3) | 82 (32.4) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 100 (6.3) | 68 (5.1) | 26 (7.4) |

| Body aches | 531 (34.1) | 387 (29.2) | 96 (27.4) |

| Bone pain and myalgia | 358 (22.8) | 311 (23.5) | 82 (23.4) |

| Fatigue | 588 (37.6) | 421 (31.8) | 102 (30.0) |

| Headache | 378 (24.3) | 259 (19.5) | 61 (17.4) |

| Running nose | 63 (3.8) | 34 (2.6) | 7 (2.0) |

| Systemic AEs | |||

| Water retention | 5 (0.3) | 34 (2.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Menstrual changes (T = 965) * | 75 (7.7) | 53 (6.2) | 11 (3.1) |

| Chest pain | 48 (2.9) | 31 (2.3) | 9 (2.5) |

| Breathing difficulties | 59 (3.7) | 35 (2.6) | 9 (2.5) |

| Stomach pain (persistence) | 30 (1.9) | 21 (1.6) | 9 (2.5) |

| Visual disturbance | 20 (1.2) | 19 (1.4) | 6 (1.7) |

| Neuro-psychiatric disturbance | 25 (1.5) | 24 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood pressure disturbance | 18 (1.0) | 12 (0.9) | 4 (1.1) |

| Blood sugar disturbance | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.15) | 0 (0.0) |

| Liver function disturbance | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.22) | 3 (0.9) |

| Kidney function disturbance | 3 (0.1) | 9 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Pregnancy changes (T = 965)* | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lactating changes (T = 965) * | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.15) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 17 (1.08) | 6 (0.4) | 17 (4.9) |

| Hair falls /whitening | 45 (2.8) | 39 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Skin disorders | 12 (0.7) | 14 (1.05) | 5 (1.4) |

| Loss of taste and or /smell | 32 (2.0) | 9 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| Auditory changes | 11 (0.7) | 2 (0.15) | 1 (0.3) |

| Sleep disturbance | 69 (4.3) | 49 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Others | 20 (1.8) | 33 (2.5) | 18 (5.1) |

| Serious AEs | |||

| Thrombosis | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Convulsions | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 5 (1.4) |

| Thrombocytopenia # | 5 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cardiac side effects (carditis/ arrhythmia) | 18 (1.1) | 3 (0.22) | 3 (0.85) |

| Auto-immune diseases | 11 (0.7) | 18 (1.35) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gillian-Barrie syndrome | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypersensitivity | 29 (1.7) | 17 (1.3) | 5 (1.4) |

| Management of the adverse effects | |||

| Nothing | 757 (48.4) | 750 (56.6) | 139 (39.7) |

| Medical symptomatic treatment | 785 (50.2) | 563 (42.5) | 177 (50.6) |

| Medical consultation | 57 (3.6) | 42 (3.2) | 15 (4.3) |

| Hospital admission | 7 (0.5) | 9 (0.67) | 4 (1.1) |

| Home rest /sick leave from work | 99 (6.3) | 131 (9.9) | 32 (9.1) |

#Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT).

##Because the vaccination strategies regarding giving booster doses have not been made available in five countries only available in SA, the participants of these five countries should not be taken into consideration when evaluating the third dose.

F: Frequency; calculated per row.

*Total number of married women only = 965 females.

Figure 3.

The details of AEs and SARS-COV-2 infection after each vaccination dose.

Adverse effects among different vaccine types

The frequency of AEs varied depending on the vaccine type. Among the vaccines, Johnson and Johnson (93.9%), Moderna (84.4%), Sputnik Light (85.3%), Sputnik V (82.6%), and Pfizer-BioNTech (82.1%) had significantly the highest frequency of reported AEs (P-value < 0.001). After the first dose, Johnson and Johnson had significantly the highest frequency of AEs (97.4%) while after the second dose, Pfizer-BioNTech (81.5%) and Sputnik V (80.6%) had the highest AEs rate. The details of the AE rate distribution based on vaccine type are described in Table 4.

Table 4.

The relationship between the reported AEs after COVID-19 vaccinations, and the type of vaccine.

| AstraZeneca | J&J | Sputnik V | Sputnik-light | Sinovac | Sinopharm | Moderna | Pfizer | P of Fisher’s exact test * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (%) | F (%) | F (%) | F (%) | F (%) | F (%) | F (%) | F (%) | ||

| (a) The first dose (T = 1564) | |||||||||

| No AEs | 38 (10.4) | 1 (2.6) | 12 (16.4) | 3 (11.1) | 71 (33.0) | 69 (48.3) | 1 (11.1) | 107 (17.0) | < 0.001 |

| Local AEs only | 31 (8.5) | 3 (7.7) | 13 (17.8) | 5 (18.5) | 58 (27.0) | 28 (19.6) | 1 (11.1) | 121 (19.2) | |

| Local + general AEs | 243 (66.4) | 29 (74.4) | 39 (53.4) | 17 (63.0) | 75 (34.9) | 34 (23.8) | 5 (55.6) | 304 (48.2) | |

| Local + systemic AEs | 44 (12.0) | 4 (10.3) | 7 (9.6) | 2 (7.4) | 9 (4.2) | 10 (7.0) | 2 (22.2) | 83 (13.3) | |

| Serious AEs | 10 (2.7) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.5) | |

| (b) The 2nd dose ( T = 1325) | |||||||||

| No AEs | 106 (35.7) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (19.4) | 2 (28.6) | 81 (63.8) | 115 (58.4) | 4 (20.0) | 133 (18.5) | < 0.001 |

| Local AEs only | 33 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (17.3) | 48 (24.4) | 2 (10.0) | 122 (19.9) | |

| Local + general AEs | 123 (41.4) | 3 (50.0) | 20 (55.6) | 3 (42.9) | 16 (12.6) | 20 (10.2) | 7 (35.0) | 248 (40.5) | |

| Local + systemic AEs | 27 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.9) | 2 (28.6) | 8 (6.3) | 11 (5.6) | 6 (30.0) | 115 (18.8) | |

| Serious AEs | 8 (2.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (5.0) | 14 (2.3) | |

| (c) The booster dose (T = 350) | |||||||||

| No AEs | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 38 (12.6) | 0.01 |

| Local AEs only | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (100.0) | 67 (22.2) | |

| Local + general AEs | 6 (66.7) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 140 (46.4) | |

| Local + systemic AEs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (16.2) | |

| Serious AEs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (2.6) | |

| Total number of doses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 672 | N = 49 | N = 109 | N = 34 | N = 416 | N = 278 | N = 32 | N = 1551 | ||

| No AE | 288 (42.9) | 3 (6.1) | 19 (17.4) | 5 (14.7) | 154 (37.0) | 189 (67.9) | 5 (15.6) | 278 (17.9) | < 0.001 |

| AEs | 384 (57.1) | 46 (93.9) | 90 (82.6) | 29 (85.3) | 262 (62.9) | 89 (32.1) | 27 ( 84.4) | 1273 (82.1) | |

F: Frequency; calculated per column.

* Fisher’s exact test; P-value significance < 0.05.

Determinants of adverse effects following the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine

In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, a statistically significant association was found between reported AEs and certain parameters. AEs were more common among females (84.7%), and individuals with a higher education level (79.1%). Libyan participants had the lowest occurrence of AEs (62.8%) (Table 1). Participants using anticoagulants (31.4%), individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (18.04%), and those vaccinated through mobile campaigns (35.7%) were associated with lower rates of AE reports (Table 2).

Univariate analysis revealed that old age, female sex, nationality, obesity, and comorbidities were statistically significant factors associated with AEs after the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccination (p < 0.05). The use of supplements was found to be a protective factor (OR: 0.56, 95% CI: [0.41–0.76], p = 0.012). Following the multivariable model, independent associated factors of AEs following the first dose of COVID-19 vaccination were age, gender, and certain comorbidities. Higher ages significantly increase the odds of having AEs with the over-75-year group having the highest odds (aOR: 2.71, 95% CI: 1.59–4.42, p < 0.001. Males were less likely to have AEs compared to females (aOR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.63–0.82, p < 0.001). The details of the regression analysis of factors determining the odds of experiencing AEs are described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Factors associated with the COVID-19 vaccine adverse effects after the first dose.

| Variables | Univariable analyses | Multiple logistic regression model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | OR (95% CI) | P-value * | aOR (95% CI) | P-value * |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 12–18 (Reference) | – | – | – | – |

| 19–30 | 1.67 (1.07–2.62) | 0.025 | 1.73 (1.06–2.82) | 0.028 |

| 31–45 | 1.71 (1.19–2.73) | 0.007 | 1.77 (1.13–2.80) | 0.014 |

| 46–60 | 2.20 (1.43–3.38) | < 0.001 | 2.16 (1.36–3.45) | 0.001 |

| 61–75 | 2.68 (1.71–4.20) | < 0.001 | 2.60 (1.59–4.25) | < 0.001 |

| > 75 | 2.71 (1.75–5.1) | < 0.001 | 2.71 (1.59–4.42) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.55 (0.48–0.61) | 0.72 (0.63–0.82) | ||

| Female (Reference) | ||||

| Male | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Healthcare worker | – | |||

| No (Reference) | – | – | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) | – |

| Yes | 0.83 (0.72–0.97) | 0.023 | 0.392 | |

| Drug intake | ||||

| None of the below (Reference) | – | – | – | – |

| Supplements | 1.22 (1.00–1.49) | 0.05 | – | – |

| Anti-coagulants | 0.56 (0.41–0.76) | 0.012 | – | – |

| Immune suppression medications | 1.01 (0.60–1.69) | 0.975 | – | – |

| Hormonal therapy | 0.47 (0.20–1.19) | 0.117 | – | – |

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| No (Reference) | – | – | – | – |

| Psychiatric /neurological | 0.51 (0.42–0.62) | < 0.001 | 0.36 (0.22–0.61) | < 0.001 |

| Organic | 0.56 (0.41–0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.45 (0.19–1.09) | 0.076 |

| Both | 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | < 0.001 | 2.68 (1.71–4.20) | < 0.001 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection before vaccination | ||||

| No (Reference) | ||||

| Suspicious (symptoms) | – | – | ||

| Yes, without symptoms | 0.57 (0.37–0.89) | 0.014 | – | – |

| Yes, managed at home | 0.79 (0.37–1.68) | 0.537 | – | – |

| Yes, managed at hospitals | 0.24 (0.12–0.50) | < 0.001 | – | – |

| 0.72 (0.41–1.26) | 0.25 | – | – | |

*Statistically significant with at least 5% of the significance level.

(OR): Odds Ratio, (aOR): adjusted OR, (CI): Confidence Interval.

Post-vaccination COVID-19 infection

Post-vaccination COVID-19 infection among different types of vaccines

Regarding vaccine types, the highest frequency of COVID-19 cases after the first dose was reported with the Johnson and Johnson vaccine (17.9%), Sputnik light vaccine (14.8%), and AstraZeneca vaccine (7.1%). After the second dose, Sinovac (32.5%), Sinopharm (25.4%), and Sputnik V (22.2%) had the highest frequency of COVID-19 cases. Overall, Sinovac (16.1%) followed by Sinopharm (15.8%) and Johnson and Johnson vaccines (14.2%) had the highest rate of post-vaccine COVID-19 (Table 6).

Table 6.

COVID-19 after vaccination, and the type of COVID-19 vaccine.

| Post-vaccination COVID-19 | Astra-Zeneca F (%) | J&J# F (%) | Sputnik V F (%) | Sputnik-light F (%) | Sinovac F (%) | Sinophar-m F (%) | Moder-na F (%) | Pfizer-BioNTech F (%) | P of fisher exact t test * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) The first dose (T = 1564) | |||||||||

| No infection | 340 (92.9) | 32 (82.1) | 68 (93.2) | 23 (85.2) | 210 (97.7) | 133 (93.0) | 9 (100.0) | 609 (96.5) | < 0.001 |

| Asymptomatic infection | 3 (0.8) | 2 (5.1) | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.6) | |

| Symptomatic managed at home | 21 (5.7) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (4.1) | 4 (14.8) | 3 (1.4) | 7 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (2.9) | |

| Symptomatic managed at the hospital | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| (b) The 2nd dose (T = 1325) | |||||||||

| No infection | 262 (93.9) | 6 (100.0) | 28 (77.8) | 7 (100.0) | 135 (67.5) | 95 (74.6) | 17 (85.0) | 570 (93.1) | < 0.001 |

| Asymptomatic infection | 6 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.6) | 4 (3.2) | 3 (15.0) | 7 (1.1) | |

| Symptomatic managed at home | 27 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (26.2) | 26 (20.6) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (5.4) | |

| Symptomatic managed at the hospital | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.7) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | |

| (c) The booster dose (T = 350) | |||||||||

| No infection | 9 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | 6 (80.0) | 3 (100.0) | 284 (92.2) | < 0.001 |

| Asymptomatic infection | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Symptomatic managed at home | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (4.9) | |

| Symptomatic managed at the hospital | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.3) | |

| Total number of doses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = 672 | T = 49 | T = 109 | T = 34 | T = 416 | T = 278 | T = 32 | T = 1551 | ||

| No infection | 611 (90.9) | 42 (85.7) | 96 (88.1) | 30 (88.2) | 349 (83.9) | 234 (84.2) | 24 (90.6) | 1463 (94.3) | < 0.001 |

| Infection | 61 ( 9.1) | 7 (14.2) | 13 (11.9) | 4 (11.8) | 67 (16.1) | 44 (15.8) | 8 (9.4) | 88 (5.7) | |

*P < 0.05 there was statistically significant difference between different types of vaccines.

F frequency (calculated per row).

## only single dose is required from J and Johnson vaccines, but due to unavailability, documentation, and restriction causes some participants received it as a second dose or booster dose.

Post-vaccination COVID-19 and its relationship with pre-vaccination COVID-19 infection

The frequency of post-vaccination COVID-19 cases was significantly associated with the pre-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection status. Among participants with no previous infection, the highest occurrence of COVID-19 cases was observed after the booster dose (12%), followed by the second dose (10.9%), followed by the first dose (2.7%). In contrast, among participants with a previous infection, the highest occurrence of COVID-19 cases was observed after the second dose (23.4%), followed by the booster dose (23.2) and the first dose (8%). Overall, having a pre-vaccination history of COVID-19 increases the risks of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 7).

Table 7.

The relationship between the SARS-COV-2 infection prior to vaccination and post-vaccination COVID-19.

| Variable | Total F (%) * | No past history of SARS-COV-2 infection F (%) | Past history of SARS-COV-2 infection F (%) | P-value # | OR [95% CI] (P) ## |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First dose (T = 1564) | |||||

| No | 1483 (94.8) | 817 (97.3) | 666 (92.0) | ||

| Yes, asymptomatic | 17 (1.1) | 2 (0.2) | 15 (2.1) | < 0.001 | 3.09 [1.9–5.07] |

| Yes, symptomatic managed at home | 62 (4.0) | 20 (2.4) | 42 (5.8) | (< 0.0001) | |

| Yes, symptomatic managed at hospital | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Second dose (T = 1325) | |||||

| No | 1114 (83.5) | 644 (89.1) | 480 (76.6) | ||

| Yes, asymptomatic | 50 (4.3) | 16 (2.2) | 34 (5.9) | < 0.001 | 2.56 [1.89–3.47] |

| Yes, symptomatic managed at home | 146 (11.0) | 57 (7.9) | 89 (15.6) | (< 0.0001) | |

| Yes, symptomatic managed at hospital | 15 (1.1) | 4 (0.8) | 11 (1.9) | ||

| Booster dose (T = 350) | |||||

| No | 297 (84.9) | 214 (88.0) | 83 (76.8) | 2.94 [1.6–5.39] | |

| Yes, asymptomatic | 33 (9.4) | 15 (6.4) | 18 (16.7) | 0.09 | − 0.0005 |

| Yes, symptomatic managed at home | 13 (3.7) | 7 (3.0) | 6 (6.4) | ||

| Yes, symptomatic managed at hospital | 7 (2.0) | 6 (2.6) | 1 (0.1) | ||

*Percentages of the total column are from the total of each dose. Otherwise, F (%) are calculated per column.

# P-value of χ2 chi square test. Significance level < 0.05.

## No past history of SARS-COV-2 infection is the reference.

Discussion

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus of research has primarily been on COVID-19 symptoms and vaccinations. Despite the widespread administration of millions of vaccine doses worldwide, concerns about the safety and efficacy of vaccinations continue to be raised. To address this, our study aimed to investigate the adverse events (AEs) associated with different types and doses of COVID-19 vaccines across six Arabic countries during the fourth wave of the pandemic.

The variation in the number of vaccinated participants among the studied Arab countries reflects differences in vaccine availability and compulsory vaccine regulations. For example, Saudi Arabia initiated vaccination for children aged 12 and older in July 2021 and mandated that all citizens and residents receive a booster dose by February 2022. In contrast, compulsory vaccination policies and booster doses had not been implemented in the remaining five countries at the time of data collection46–48.

The pattern of AEs after each dose aligns with previous reports49. This may be attributed to the cumulative immunological effect of the second dose rather than a direct immunological response50. We observed a lower frequency of AEs after the second dose with many types of vaccines compared to the first dose. However, we reported an increase in the frequency of AEs after the Sputnik V vaccine, local AEs after the Sinopharm vaccine, systemic AEs after the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, and serious AEs after the Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine. Previous studies have shown different trends, with higher local and systemic AEs reported after the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines26,50–52.

In our study, the most prevalent local AEs, such as pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site, were reported after the Pfizer-BioNTech, AstraZeneca, and Sinopharm vaccines. Previous studies conducted in the reported varying percentages were reported after the first and second doses20,26,53. The most commonly reported general AEs were fatigue, body aches, fever, headache, and myalgia, which is in line with published studies20,49.

Headache was reported in more than 50% of participants after the AstraZeneca vaccine54–56. There are no details about the pathophysiologic mechanisms, whether the intracellularly synthesized spike protein is produced by using mRNA vaccines, or the protein triggers the immune response from activated anti-inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, nitric oxide, and cytokines. Headache is the leading symptom of cerebrovascular thrombosis (CVT), including vaccine-induced ones. So, it's important to distinguish between vaccine-induced headaches and those caused by cerebrovascular thrombosis54–56.

Visual disturbances were reported by a small number of participants. There are reported cases of transient loss in the visual field due to possible acute vasospasm of the artery in the postchiasmatic visual pathway, triggered by the COVID-19 vaccine that resolved after two hours57. In other cases, macular detachment and severe choroidal thickening were detected causing visual loss and suggesting a potential inflammatory or autoimmune response to the vaccine58–60.

Elevations in blood pressure were observed among some vaccinated participants, which is consistent with reports of blood pressure surges after mRNA vaccines and an increase in home blood pressure after the first mRNA vaccine dose. Some patients required modification of anti-hypertensive drugs. This may be attributed to nervousness or white-coat hypertension. However there was no baseline data, and BP follow-up over a long period after vaccination is very important56,61.

Menstrual changes were reported among vaccinated females and it is noteworthy that by September 2, 2021, over 30,000 COVID-19-vaccinated females had reported menstrual changes to the United Kingdom’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Yellow Card surveillance system12,62. This might be a result of immunological effects on the hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle or biological effects of immune cells on the uterus lining, which contribute to the tissue's cyclical building and breaking down12,63.

Rheumatological symptoms such as bone pain, myalgia, body aches, and weariness were reported in our study, similar to some studies conducted in Italy, Libya, Iran, China, and Turkey61,63–67. These symptoms might be attributed to the immune response triggered by the vaccine, leading to transient inflammation and musculoskeletal discomfort26,68. It is important to note that these symptoms are generally self-limiting and resolve within a few days after vaccination. The association between COVID-19 vaccination and the occurrence of certain symptoms remains uncertain when compared to other vaccines. The hyper-inflammatory response triggered by the COVID-19 vaccine raises concerns about its potential as a risk factor for inflammatory musculoskeletal disorders. This cytokine activation can be attributed to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, other components of the vaccine, or the adenoviral vector used67,68.

New-onset autoimmune manifestations, including Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus, have been reported in eleven cases following COVID-19 vaccination, particularly after the first dose. The precise nature of the link between the COVID-19 vaccine and autoimmune symptoms is still unclear, whether it is coincidental or causal. Molecular mimicry, the generation of specific autoantibodies, and the influence of specific vaccination adjuvants are all thought to play a role in the development of autoimmune diseases63,69. For instance, we documented one case of GBS, a rare autoimmune neurological disorder that affects the peripheral nerves and nerve roots. GBS has been associated with other vaccines such as rabies, hepatitis A and B, influenza, and more recently, the COVID-19 vaccine70,71.

In this study, we documented the occurrence of symptoms suggesting vaccine-induced myocarditis and pericarditis, including chest pain (88 cases), shortness of breath (103 cases), and sensations of a fast-beating, fluttering, or pounding heart (34 cases). These presentations align with the CDC report on these conditions72. Our findings are consistent with previous research indicating that COVID-19 vaccine-related myocarditis primarily affects young men and is more commonly associated with mRNA vaccines such as those developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna73.

We observed a statistically significant difference in the occurrence of serious adverse events (AEs) among different vaccine types. We identified 10 cases of VITT out of 3,239 vaccine doses, which is a rare syndrome involving venous or arterial thrombosis at unusual sites such as cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) and splenic thrombosis. Additionally, we found 10 cases of thrombosis out of 3,239 vaccine doses, a comparable rate to reports from the US (17 cases of VITT, 14 cases of thrombosis out of 7,000 participants after the J&J vaccine) and lower than the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (222 cases of thrombosis out of 35 million participants after the AstraZeneca vaccine)74,75. VITT occurs when DNA leaks from the imperfect adenoviral vector used in AstraZeneca and J&J vaccines, infects cells, binds to platelet factor 4 (PF4), and triggers the production of anti-PF4 autoantibodies76.

We also discovered a significant increase in post-vaccination COVID-19 cases among individuals previously infected with COVID-19. Such findings may raise the issue of the benefit of vaccines for people who were previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. It is noteworthy that a study conducted in Kentucky (May–June 2021), reported an odds ratio of 2.34 (95% CI 1.58–3.47) of re-infection among unvaccinated participants compared to those who were fully vaccinated, suggesting that full vaccinations after a past SARS-CoV-2 infection provide additional protection by decreasing its transmissibility by shortening the duration of infectivity and so decrease the transmissibility77. Therefore, vaccination should be offered to all eligible individuals regardless of their previous infection status. While there is limited epidemiological evidence supporting the benefits of vaccination for previously infected individuals, our study supports the notion.

Regarding the frequency of post-vaccination COVID-19 in relation to the number of doses, the interpretation of the increase in infections after the second dose is still uncertain. Cumulatively, they were part of the sample that received the first dose, resulting in a significantly lower difference. Notably, the second dose can cause up to a tenfold increase in antibody levels, a stronger T-cell response, as well as more changes in the immune cells. Moreover, multiple variants of SARS-CoV-2 have emerged, primarily focused on the spike protein, a crucial element for developing vaccine candidates. Diverse vaccinations are currently undergoing clinical trials and demonstrating remarkable outcomes, however, their effectiveness still requires evaluation in various SARS-CoV-2 variants4,20.

Strengthens and Limitations:

We carried out a multicenter study in six Arab countries that included the assessment of AEs associated with eight different vaccine types. We were able to identify several associated factors with post-vaccination AEs, which can aid in monitoring and follow-up efforts during and after vaccination campaigns. Additionally, our study included patients from a previous wave of COVID-19, allowing us to track AEs across different vaccine doses. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, being an observational study, it is susceptible to bias and confounding issues. Secondly, the use of an online self-administered survey introduces limitations such as data accuracy concerns due to recall bias, sampling bias (as more than 80% of participants were well-educated), and availability bias (excluding individuals who couldn't access or use the Internet, and those who were illiterate or deceased). Thus, our study population may not represent the entire population. Furthermore, assessing SARS-CoV-2 infection rates after vaccination is complicated by the presence of the delta variant and other variants of concern, especially as the immunity from previous vaccinations may be waning. The timing between the first and second doses is relatively close together, but the interval between the second and third doses can vary widely across countries. The availability of COVID-19 confirmatory testing in the studied countries also affects the diagnosis of infection rates, potentially missing asymptomatic cases. Another limitation is the lack of assessment of participants' pre-COVID-19 vaccine health status, making it challenging to differentiate pre-existing health issues from those related to the COVID-19 vaccine. The use of a reporting system for the participants to report the AEs themselves can introduce bias in exaggerating or underreporting some AEs. Although these limitations exist, our findings are consistent with those of other international studies. Lastly, the variation in response rate among countries with a low number of responses in some e.g. Syria may be due to the method of sample collection using an online questionnaire, compounded by political unrest in some countries (e.g. Syria) hindering internet access. It is important to interpret the data of vaccine and AE rates while considering such political conditions for further extensive studies. Such variation can affect the generalizability and comparisons of results among such countries.

Conclusions

In conclusion, with the lack of multicenter or extensive studies in the Arab countries, the present multicenter study contributes to the literature regarding AEs of the COVID-19 vaccine during the fourth wave of the pandemic. The most frequently used vaccine type was Pfizer-BioNTech, followed by AstraZeneca and Sinovac. More than three-fourths of participants reported AEs after the first dose. In line with most previous studies, the majority was mild in severity and local in nature as injection site pain and redness. Different vaccines showed variable rates of AEs following the different doses. AEs were more frequently reported among older individuals, women, and those with a history of previous COVID-19 infection. Further extensive, thorough, and generalizable research is needed to draw solid conclusions.

Recommendations:

Based on our findings, we recommend.

Conducting more prospective cohort studies with a larger sample size per country to investigate the frequency and mechanisms of various AEs following vaccination.

Clinical trials should prioritize the study of serious adverse events such as thrombosis, menstrual cycle abnormalities, and blood pressure changes.

More attention should be directed toward countries with political conditions that hinder the vaccination process while cautiously interpreting their current results.

Public awareness regarding vaccine side effects should be raised, and tailored health education messages should be designed according to the demographic and social characteristics of the target population.

Implementation of a nationwide ongoing safety evaluation is crucial, particularly in monitoring and understanding the occurrence of unusual vaccine-related adverse effects with ensuring accessibility and availability of necessary services at vaccination centers is important.

Reporting any health problems experienced after vaccination to the VAERS is encouraged, and healthcare providers should refer to clinical considerations for further clinical advice and recommendations.

Additionally, healthcare providers should be aware of these potential adverse events and provide appropriate guidance and support to individuals receiving the vaccine.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study utilized a cross-sectional survey design and involved a total of 1,564 vaccinated participants from six Arab countries, namely Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Libya, Iraq, and Algeria. To be included, the individual had to be citizens or residents of one of the six Arab countries, have received COVID-19 vaccination, and are older than 12 years. Unvaccinated participants, participants who couldn't access, use, or deal with the online platform or smart devices, illiterate participants, and participants with complicated medical, mental, or psychological disorders were excluded from the study. The study adhered to the Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Checklist in its entirety42 (online Appendix 1).

Sample size and sampling techniques

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info statistical calculator 7.2.5. version, which is a trademark of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with the following parameters: a confidence interval of 95%, an expected frequency of 50%, and an acceptable margin of error of 5%. The reported adverse events rate after COVID-19 vaccination ranged widely between 13 and 90%12,24–26. We adopted a conservative estimate of 50% for the prevalence parameter in calculating the sample size. The minimum sample size was 400 responses. The sample size was increased to 1564 to increase the power of the study.

A multistage sampling technique was employed in each country, involving the random selection of three governorates from each country, followed by the selection of one urban area and one rural area from each governorate. The number of samples obtained from each area was based on the vaccination coverage and the fulfillment of the selection criteria. Because the data available for the probable geographical variations in vaccination coverage and the rate of people taking booster doses are only from a few countries and are skewed, we relied on the data of first doses (percentages of the population vaccinated with the first dose) to have a representative sample. The context of sampling and vaccination in the included countries is shown in online Appendix 2.

Data collection

Data collection tool

A questionnaire was developed based on the existing literature7,9,12–15 and underwent a rigorous translation process. The questionnaire was initially created in English, and translated into Arabic by a bilingual panel of two healthcare professionals and one qualified medical translator. The back translation for accuracy was approved by two English-speaking translators, and the original panel was consulted in case there were any issues.

To validate the content of the survey, six family medicine and six public health and community medicine experts, two from each country, were invited to fill in the survey and assess the clarity, comprehension, and relevance of the questionnaire. We adjusted the questionnaire to ensure both relevance and feasibility among our population according to the experts’ comments. Afterward, a pilot study was conducted involving 30 vaccinated participants from each country43–45. Additionally, the reliability and internal consistency of the survey were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha which was 0.78 which was deemed acceptable.

The questionnaire consisted of two main sections. The first was for sociodemographic data, health-related factors, and history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Secondly, COVID-19 vaccination-related data included vaccine type and doses, vaccination setting, self-reported AEs, and rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination. The study questionnaire is available in online Appendix 3.

Data collection process

The data collection process took place in the period between January 1st and January 22nd, 2022. In line with VAERS system18,19, the questionnaire was administered through online platforms including websites and social media such as Facebook, Twitter, official emails, and WhatsApp groups. In addition, a community-based sample from various public places (such as schools, mosques, malls, and educational settings) responded to the questionnaire using either tablets or smartphones provided by the data collectors or by scanning the QR code, especially for children less than 16 years old after informed written consent from their parents. All questions were obligatory to avoid incomplete forms. Only a single answer was allowed per each logging email to avoid duplicate responses. Participants completed and submitted the questionnaire after providing their consent to participate. Follow-up messages and reminders were sent to increase the response rate.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was the reporting of AEs following COVID-19 vaccination. A total of 32 self-reported COVID-19 vaccine-related AEs were considered and categorized into no local/general AEs, local AEs at the injection site, and general AEs (systemic and serious AEs) based on CDC guidance. Secondary outcomes were factors associated with AEs after the first dose and the association between pre-vaccination COVID-19 infection and post-vaccination COVID-19.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was coded into SPSS version 27 for analysis. The normally distributed quantitative data was presented as mean ± SD, after testing by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc tests were used to analyze normally distributed quantitative data. Qualitative data such as age groups and sex were presented as frequency and percentage, and the chi-squared test (χ2), and Fisher’s exact test were used to test the association between categorical variables. A simple logistic regression analysis within the framework of a generalized linear model technique was used to examine the association of each potential factor with the binary outcome of vaccination adverse effects (no AE, and with AEs). Independent variables included baseline variables such as age, sex, comorbidities, and nationalities. Next, we fitted a final logistic regression model using a stepwise method to examine the independent associations of each potential factor with the outcome of interest. In the stepwise regression method, first, we added into the model all those factors that were significant (p < 0.05) in the univariable analyses. Then we retained significant (p < 0.05) factors in the model and iteratively tested all non-significant variables in the final model for possible significance in the subsequent steps. We used likelihood ratio tests to examine the statistical significance of each factor. From the above fitted final model, we estimated and reported the adjusted odds ratios (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). To examine the final model fit, we used the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. The level of significance was set at (p < 0.05).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the research center at Zagazig University (IRP#9288–25-1-2022a). Participants were provided with informed consent before answering the questionnaire. The questionnaire did not include sensitive or private questions, and respondents' identities remained anonymous.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the research center at Zagazig University IRP#9288–25-1-2022a.

Informed consent statement

Participants were provided with informed consent before answering the questionnaire. The questionnaire did not include sensitive or private questions, and respondents' identities remained anonymous.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express special thanks to all the recruited participants in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, and validation; S.A., and H.M.F.. Formal analysis: S.A. Data curation and writing the original draft: A.A.Z., E.A.I., E.M.I., I.F.D., L.R.A., D.B., A.A.S., G.E., J.S., and A.A. Reviewing and editing: S.A., M.L.R., Y.A., R.E. and H.T.A. Visualisation: S.A. and R.E. Supervision: S.A. Software: R.E. Project administration: S.A., and R.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Samar A. Amer, Email: dr_samar11@yahoo.com

Hossam Tharwat Ali, Email: Hossam.Tharwat@med.svu.edu.eg.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-54886-0.

References

- 1.The World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int.

- 2.Ali HT, et al. Unravelling COVID-19 vaccination attributes worldwide: an extensive review regarding uptake, hesitancy, and future implication. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023;85:3519–3530. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000000921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebru AA, et al. Global burden of COVID-19: Situational analyis and review. Hum. Antibod. 2021;29:139–148. doi: 10.3233/HAB-200420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farooqi T, et al. An overview of SARS-COV-2 epidemiology, mutant variants, vaccines, and management strategies. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14:1299–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malik JA, et al. Targets and strategies for vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 2021;137:111254. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullard A. How COVID vaccines are being divvied up around the world. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.So AD, Woo J. Reserving coronavirus disease 2019 vaccines for global access: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanyaolu A, et al. Current advancements and future prospects of COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics: a narrative review. Ther. Adv. Vaccines Immunother. 2022;10:25151355221097559. doi: 10.1177/25151355221097559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Guidance for COVID-19 Vaccination | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html (2023).

- 10.Swed, S. et al. A multinational cross-sectional study on the awareness and concerns of healthcare providers toward monkeypox and the promotion of the monkeypox vaccination. Front. Public Health11, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Amer SA, Shah J, Abd-Ellatif EE, El Maghawry HA. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among physicians during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: Attitude, intentions, and determinants: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:823217. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.823217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amer AA, et al. Menstrual changes after COVID-19 vaccination and/or SARS-CoV-2 infection and their demographic, mood, and lifestyle determinants in Arab women of childbearing age, 2021. Front. Reprod. Health. 2022;4:927211. doi: 10.3389/frph.2022.927211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathieu, E. et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): Policy Responses to the Coronavirus Pandemic. Our World in Data (2020).

- 14.Chauhan N, et al. COVID-19 vaccine development in India during Janaury 2021- December 2021: A narrative review. Saudi J. Med. 2022;7:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccines: safety surveillance manual. (World Health Organization, 2020).

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Administration Overview for Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/janssen/index.html (2023).

- 17.Cines DB, Bussel JB. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:2254–2256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2106315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). VAERS - Vaccine Safety. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vaers/index.html (2023).

- 19.Singleton JA, Lloyd JC, Mootrey GT, Salive ME, Chen RT. An overview of the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS) as a surveillance system. VAERS Working Group. Vaccine. 1999;17:2908–2917. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamatatos L, et al. mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science. 2021;372:1413–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.abg9175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik JA, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 mutations versus vaccine effectiveness: New opportunities to new challenges. J. Infect. Public Health. 2022;15:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malik JA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: Clinical endpoints and psychological perspectives: A literature review. J. Infect. Public Health. 2022;15:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Background document on the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) against COVID-19. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/background-document-on-the-mrna-1273-vaccine-(moderna)-against-covid-19.

- 24.Dhamanti I, Suwantika AA, Adlia A, Yamani LN, Yakub F. Adverse reactions of COVID-19 Vaccines: A scoping review of observational studies. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023;16:609–618. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S400458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logunov DY, et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397:671–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menni C, et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21:939–949. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meijide Míguez, H. et al. Immunogenicity, effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccine in older adults living in nursing homes: A real-life study. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol.58, 125–133 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kataria S, et al. Safety, immunogenicity & effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J. Med. Res. 2022;155:518–525. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.ijmr_1771_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batıbay S, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the CoronaVac and BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and healthy adults: comparison of different vaccines. Inflammopharmacology. 2022;30:2089–2096. doi: 10.1007/s10787-022-01089-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyaji KT, et al. Adverse events following immunization of elderly with COVID-19 inactivated virus vaccine (CoronaVac) in Southeastern Brazil: an active surveillance study. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 2022;64:e56. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946202264056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nasreen S, et al. Background incidence rates of adverse events of special interest related to COVID-19 vaccines in Ontario, Canada, 2015 to 2020, to inform COVID-19 vaccine safety surveillance. Vaccine. 2022;40:3305–3312. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parida SP, et al. Adverse events following immunization of COVID-19 (Covaxin) vaccine at a tertiary care center of India. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:2453–2459. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganesan S, et al. Vaccine side effects following COVID-19 vaccination among the residents of the UAE-an observational study. Front. Public Health. 2022;10:876336. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.876336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almalki OS, et al. The role of blood groups, vaccine type and gender in predicting the severity of side effects among university students receiving COVID-19 vaccines. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023;23:378. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahsan, M. et al. A Cross-Sectional study to assess mRNA-COVID-19 vaccine safety among Indian Children (5–17 Years) living in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines (Basel)11, 207 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Alsaiari AA, et al. Assessing the adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccine in different scenarios in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Med. J. 2023;44:194–201. doi: 10.15537/smj.2023.44.2.20220680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan YAM, et al. A retrospective evaluation of side-effects associated with the booster dose of Pfizer-BioNTech/BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine among females in Eastern Province Saudi Arabia. Vaccine. 2022;40:7087–7096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashmawy, R. et al. Effectiveness and safety of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BBIBP-CorV) among healthcare workers: A seven-month follow-up study at fifteen central hospitals. Vaccines (Basel)11, 892 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Haji A, et al. Does ChAdOx1-S and BNT162b2 heterologous prime-boost vaccination trigger higher rates of vaccine-related adverse events? IJID Reg. 2023;7:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijregi.2023.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meshref TS, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 astrazeneca vaccine on safety and blood elements of Egyptian healthcare workers. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023;27:241–248. doi: 10.4103/ijoem.ijoem_275_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saleh AA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity evaluation of inactivated whole-virus-SARS-COV-2 as emerging vaccine development in Egypt. Antib. Ther. 2021;4:135–143. doi: 10.1093/abt/tbab012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019;13:S31–S34. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browne RH. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Stat. Med. 1995;14:1933–1940. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.In J. Introduction of a pilot study. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017;70:601–605. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2017.70.6.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore CG, Carter RE, Nietert PJ, Stewart PW. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2011;4:332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Hanawi, M. K., Alshareef, N., & El-Sokkary, R. H. Relief after COVID-19 vaccination: A doubtful or evident outcome? Front. Med. (Lausanne)8, 800040 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Gendered impacts of COVID-19 and equitable policy responses in agriculture, food security and nutrition. (FAO, 2020). doi:10.4060/ca9198en.

- 48.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee September 17, 2021 Meeting. FDAhttps://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/vaccines-and-related-biological-products-advisory-committee-september-17-2021-meeting-announcement (2022).

- 49.Gravagna K, et al. Global assessment of national mandatory vaccination policies and consequences of non-compliance. Vaccine. 2020;38:7865–7873. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quer, G. et al. The Physiologic Response to COVID-19 Vaccination. (2021) doi:10.1101/2021.05.03.21256482.

- 51.Meylan S, et al. Stage III hypertension in patients after mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Hypertension. 2021;77:e56–e57. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanyaolu A, et al. Reactogenicity to COVID-19 vaccination in the United States of America. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2022;11:104–115. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2022.11.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riad A, et al. Prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine side effects among healthcare workers in the Czech Republic. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:1428. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voysey M, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Göbel CH, et al. Headache attributed to vaccination against COVID-19 (Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) with the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: A multicenter observational cohort study. Pain Ther. 2021;10:1309–1330. doi: 10.1007/s40122-021-00296-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Göbel, C. H. et al. Clinical characteristics of headache after vaccination against COVID-19 (coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine: a multicentre observational cohort study. Brain Commun3, fcab169 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Jumroendararasame C, et al. Transient visual field loss after COVID-19 vaccination: Experienced by ophthalmologist, case report. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2021;24:101212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2021.101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramasamy MN, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2021;396:1979–1993. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Health Organization. Interim recommendations for use of the ChAdOx1-S [recombinant] vaccine against COVID-19 (AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine AZD1222 VaxzevriaTM, SII COVISHIELDTM). https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-AZD1222-2021.1.

- 60.Goyal M, Murthy SI, Annum S. Bilateral multifocal choroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Ocular Immunol. Inflammat. 2021;29:753–757. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1957123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zappa M, Verdecchia P, Spanevello A, Visca D, Angeli F. Blood pressure increase after Pfizer/BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021;90:111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Coronavirus vaccine - summary of Yellow Card reporting. GOV.UKhttps://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting.

- 63.Chen Y, et al. New-onset autoimmune phenomena post-COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology. 2022;165:386–401. doi: 10.1111/imm.13443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C, Henry B. Mild adverse reactions after COVID-19 vaccination: updated analysis of italian medicines agency data. SSRN J. 2021 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3817988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saricaoglu EM, Hasanoglu I, Guner R. The first reactive arthritis case associated with COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:192–193. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.An Q-J, Qin D-A, Pei J-X. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 vaccination. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:2954–2956. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1920274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Babamahmoodi F, et al. Side effects and Immunogenicity following administration of the Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine in health care workers in Iran. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:21464. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00963-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Galeotti C, Bayry J. Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases following COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020;16:413–414. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0448-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leonhard SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of Guillain-Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019;15:671–683. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0250-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dunkić N, Nazlić M, Dunkić V, Bilić I. Analysis of post-COVID-19 Guillain-Barré syndrome over a period of one year in the university hospital of Split (Croatia) Neurol. Int. 2023;15:1359–1370. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15040086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hammoudi D, et al. Induction of autoimmune diseases following vaccinations: a review. SM Vaccine Vaccin. 2015;1:1011. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Myocarditis and Pericarditis After mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination. Centers for Disease Control and Preventionhttps://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/myocarditis.html (2020).

- 73.Salah HM, Mehta JL. COVID-19 vaccine and myocarditis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021;157:146–148. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.European Medical Agency (EMA). COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen: EMA finds possible link to very rare cases of unusual blood clots with low platelets. European Medicines Agencyhttps://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/covid-19-vaccine-janssen-ema-finds-possible-link-very-rare-cases-unusual-blood-clots-low-blood (2021).

- 75.Li X, et al. Comparative risk of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome or thromboembolic events associated with different covid-19 vaccines: international network cohort study from five European countries and the US. BMJ. 2022;379:e071594. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Siegler JE, et al. Cerebral vein thrombosis with vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Stroke. 2021;52:3045–3053. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cavanaugh AM, Spicer KB, Thoroughman D, Glick C, Winter K. reduced risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 After COVID-19 vaccination - Kentucky, May-June 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:1081–1083. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7032e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.