Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the existing meta-analytic evidence of associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods, as defined by the Nova food classification system, and adverse health outcomes.

Design

Systematic umbrella review of existing meta-analyses.

Data sources

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, as well as manual searches of reference lists from 2009 to June 2023.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of cohort, case-control, and/or cross sectional study designs. To evaluate the credibility of evidence, pre-specified evidence classification criteria were applied, graded as convincing (“class I”), highly suggestive (“class II”), suggestive (“class III”), weak (“class IV”), or no evidence (“class V”). The quality of evidence was assessed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) framework, categorised as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low” quality.

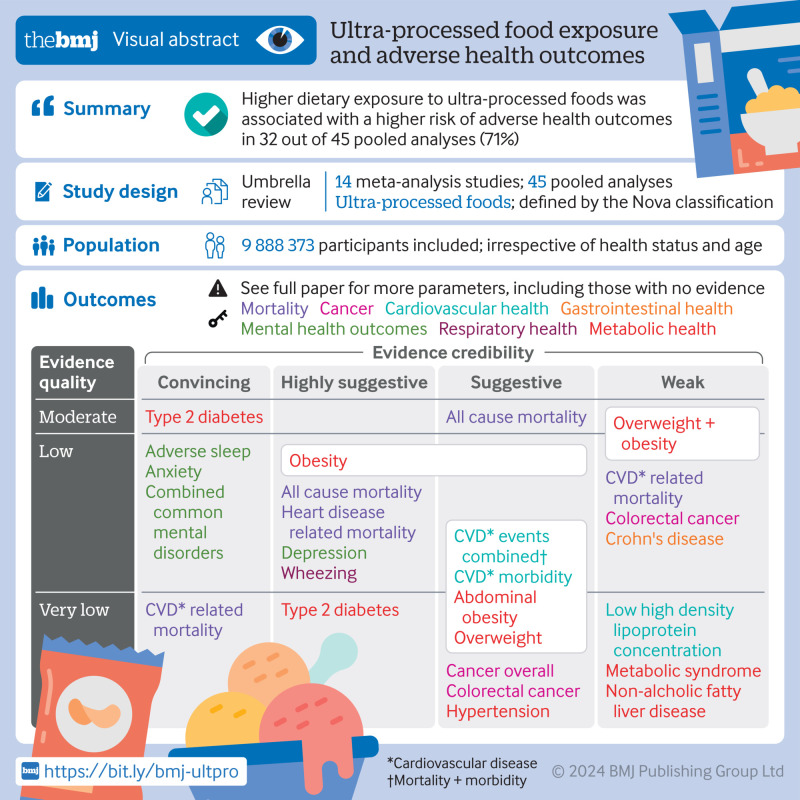

Results

The search identified 45 unique pooled analyses, including 13 dose-response associations and 32 non-dose-response associations (n=9 888 373). Overall, direct associations were found between exposure to ultra-processed foods and 32 (71%) health parameters spanning mortality, cancer, and mental, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic health outcomes. Based on the pre-specified evidence classification criteria, convincing evidence (class I) supported direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and higher risks of incident cardiovascular disease related mortality (risk ratio 1.50, 95% confidence interval 1.37 to 1.63; GRADE=very low) and type 2 diabetes (dose-response risk ratio 1.12, 1.11 to 1.13; moderate), as well as higher risks of prevalent anxiety outcomes (odds ratio 1.48, 1.37 to 1.59; low) and combined common mental disorder outcomes (odds ratio 1.53, 1.43 to 1.63; low). Highly suggestive (class II) evidence indicated that greater exposure to ultra-processed foods was directly associated with higher risks of incident all cause mortality (risk ratio 1.21, 1.15 to 1.27; low), heart disease related mortality (hazard ratio 1.66, 1.51 to 1.84; low), type 2 diabetes (odds ratio 1.40, 1.23 to 1.59; very low), and depressive outcomes (hazard ratio 1.22, 1.16 to 1.28; low), together with higher risks of prevalent adverse sleep related outcomes (odds ratio 1.41, 1.24 to 1.61; low), wheezing (risk ratio 1.40, 1.27 to 1.55; low), and obesity (odds ratio 1.55, 1.36 to 1.77; low). Of the remaining 34 pooled analyses, 21 were graded as suggestive or weak strength (class III-IV) and 13 were graded as no evidence (class V). Overall, using the GRADE framework, 22 pooled analyses were rated as low quality, with 19 rated as very low quality and four rated as moderate quality.

Conclusions

Greater exposure to ultra-processed food was associated with a higher risk of adverse health outcomes, especially cardiometabolic, common mental disorder, and mortality outcomes. These findings provide a rationale to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of using population based and public health measures to target and reduce dietary exposure to ultra-processed foods for improved human health. They also inform and provide support for urgent mechanistic research.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42023412732.

Introduction

Ultra-processed foods, as defined using the Nova food classification system, encompass a broad range of ready to eat products, including packaged snacks, carbonated soft drinks, instant noodles, and ready-made meals.1 These products are characterised as industrial formulations primarily composed of chemically modified substances extracted from foods, along with additives to enhance taste, texture, appearance, and durability, with minimal to no inclusion of whole foods.2 Analyses of worldwide ultra-processed food sales data and consumption patterns indicate a shift towards an increasingly ultra-processed global diet,3 4 although considerable diversity exists within and between countries and regions.5 6 Across high income countries, the share of dietary energy derived from ultra-processed foods ranges from 42% and 58% in Australia and the United States, respectively, to as low as 10% and 25% in Italy and South Korea.5 6 In low and middle income countries such as Colombia and Mexico, for example, these figures range from 16% to 30% of total energy intake, respectively.5 Notably, over recent decades, the availability and variety of ultra-processed products sold has substantially and rapidly increased in countries across diverse economic development levels, but especially in many highly populated low and middle income nations.3

The shift from unprocessed and minimally processed foods to ultra-processed foods and their subsequent increasing contribution to global dietary patterns in recent years have been attributed to key drivers including behavioural mechanisms, food environments, and commercial influences on food choices.7 8 9 10 11 These factors, combined with the specific features of ultra-processed foods, raise concerns about overall diet quality and the health of populations more broadly. For example, some characteristics of ultra-processed foods include alterations to food matrices and textures, potential contaminants from packaging material and processing, and the presence of food additives and other industrial ingredients, as well as nutrient poor profiles (for example, higher energy, salt, sugar, and saturated fat, with lower levels of dietary fibre, micronutrients, and vitamins).6 12 Although mechanistic research is still in its infancy, emerging evidence suggests that such properties may pose synergistic or compounded consequences for chronic inflammatory diseases and may act through known or plausible physiological mechanisms including changes to the gut microbiome and increased inflammation.12 13 14 15 16 Researchers, public health experts, and the general public have shown considerable interest in ultra-processed dietary patterns, foods, and their constituent parts given their potential role as modifiable risk factors for chronic diseases and mortality.

Although several meta-analyses have made efforts to consolidate the many individual original research articles that have investigated the associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and the risk of adverse health outcomes in the past decade,17 18 no comprehensive umbrella review has offered a broad overview and assessment of the existing meta-analytic evidence. Undertaking such a comprehensive review has the potential to enhance our understanding of these associations and provide valuable insights for better informing public health policies and strategies. This is particularly pertinent as the global debate continues regarding the need for public health measures to tackle exposure to ultra-processed foods in general populations.19 20 To bridge this gap in evidence and contribute to the ongoing discussion on the role of ultra-processed food exposure in chronic diseases, we did an umbrella review to evaluate the evidence provided by meta-analyses of observational epidemiological studies exploring the associations between exposure to ultra-processed food and the risk of adverse health outcomes.

Methods

We conducted and reported this systematic umbrella review of meta-analyses (herein referred to as “meta-analysis studies”) in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.21

Inclusion criteria and searches

We found no existing pooled analyses of randomised controlled trials during the pilot phase of this review. Consequently, we refined our search approach and scope to focus on observational epidemiological studies. Thus, we outlined inclusion criteria in accordance with the population, exposure, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PECOS) reporting structure.22 Eligible meta-analysis studies comprised human populations across the life course, irrespective of health status (population). We also considered meta-analysis studies that examined associations of dietary intake of ultra-processed foods, as defined by the Nova food classification system (exposure), comparing dose-response (continuous exposure) and/or non-dose-response (categorical only or categorical and continuous exposure) associations of dietary intake of ultra-processed foods (comparison), with any adverse health endpoint (outcome). Included in our review were observational epidemiological study designs (for example, prospective cohort, case-control, and/or cross sectional) that pooled categorical or continuous outcome data by using meta-analysis (study design).

The lead author (MML) did a systematic search across MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane databases for studies spanning the period from 2009 to June 2023 (last update). The year 2009 aligns with the initial publication of the details and principles of the Nova food classification system, which introduced the concept of ultra-processed foods.23 We applied no language limitations.

To identify relevant meta-analysis studies, we used key search terms and variations of text words related to ultra-processed food or Nova and meta-analysis study design: (“ultra-processed food” OR UPF OR “Nova food classification system”) AND (“meta-analysis” OR “systematic review”). The specific search strings for each database can be found in supplementary table A. We used Covidence systematic review software to do duplicate primary screening based on titles and abstracts (MML and EG) and duplicate secondary screening based on full text articles (MML and WM). We screened references cited within the eligible meta-analysis studies to identify any additional relevant meta-analysis studies (EG). Any disagreements between authors conducting eligibility screening were resolved through consensus. We included the most recent and/or largest meta-analysis study when multiple pooled analyses were available for the same adverse health outcome. This is consistent with the methods used in previous umbrella reviews.24 25 26 In cases in which the most recent meta-analysis study examined non-dose-response and dose-response exposure to ultra-processed foods, we included both meta-analysed effect estimates.

Data extraction

We extracted characteristics of the original research articles included in the retained meta-analysis studies in duplicate by using a pre-piloted custom Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (MML, EG, SD, DNA, AJM, and SG). These data included details such as the outcome, spanning health domains such as mortality, cancer, and mental, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic health outcomes. In addition, the data extraction encompassed details on the level of exposure comparison, distinguishing between dose-response (involving each additional serving per day or a 10% increment) and non-dose-response (encompassing categories such as high versus low, daily consumers versus not daily consumers, and frequent consumption versus no frequent consumption, as well as combinations of categories with continuous exposure including 1% or 10% increments). It also covered the total number of studies (original research articles), participants, and cases included in the pooled analysis. The extraction included effect estimates with 95% confidence intervals from both separate original research articles and those pooled from the meta-analysis studies, as well as the pooled effect size metric (hazard ratios, odds ratios, and risk ratios). Furthermore, we extracted details about the meta-analysis study, including the first author’s name, publication year, original research study design, and competing interests and funding disclosures of meta-analysis study authors. We prioritised pooled estimates with the largest number of prospective cohorts, given that prospective studies guarantee temporality in epidemiological associations and strongly limit reverse causality bias.27 Additionally, we extracted pooled estimates for related health outcomes that were meta-analysed together and separately (for example, metabolic syndrome and its individual components including low high density lipoprotein cholesterol and hypertriglyceridaemia). If information was missing or unclear in the meta-analysis studies, we obtained the data from the original research articles or directly requested it from the corresponding author(s) of those meta-analysis studies. If discrepancies existed between the data reported in the original research articles and the meta-analyses, we prioritised extracting data from the original research article.

Data analysis

Operating according to previously published methods and guidance,28 29 we used a random effects meta-analysis model to reanalyse the effect estimates for each outcome. As part of our main reanalysis, we took the following steps: entry of separate effect estimates and the total number of participants and cases from the original research articles; recalculation of the pooled effect estimates using the original metric used by the meta-analysis study authors (hazard ratio, odds ratio, and risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals); recalculation of the P value; and recalculation of the between study heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We also calculated 95% prediction intervals and assessed excess significance bias, small study effects, and the largest study significance (detailed below) as part of our reanalysis.

I2 statistic

We used the I2 statistic to assess the proportion of variability in a pooled analysis that was explained by between study heterogeneity, rather than by sampling error, and to reflect the extent to which 95% confidence intervals from the different original research articles overlapped with each other.30 We considered a value of 50% to be moderate heterogeneity and a value of 75% or more to be high heterogeneity.30

Prediction intervals

Unlike 95% confidence intervals, which give a range within which we can reasonably expect the true population parameter to fall based on our sample, 95% prediction intervals provide a range in which we can anticipate the value of an individual observation from future studies to fall.31 In an umbrella review, if the 95% prediction intervals exclude the null, it indicates a statistically significant range of effect estimates.31 Notably, outputs for tests of 95% prediction intervals, as well as the small study effects and excess significance bias (as described below), were available only for pooled analyses involving three or more original research articles (n=28).

Excess significance bias

We did a test for excess significance to determine whether the number of studies with nominally significant results (P<0.05) was higher than expected, based on statistical power.32

Small study effects

We used Egger's regression asymmetry test to detect potential small study effects, whereby smaller studies sometimes show different, often larger, effect estimates than large studies.33

Largest study significance

We assessed whether effect estimates from the largest original research article (that is, the study with the highest participant count) included in the pooled analyses had a P value below 0.05. This evaluation is expected to provide the most reliable and precise estimation considering the statistical power involved.35 We evaluated the significance of the largest study across all 45 unique pooled analyses.

Visualisation

For visually comparative purposes, we developed forest plots whereby pooled effect estimates were harmonised to equivalent odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals by using methods presented in table 1 of Fusar-Poli et al (2018).36 In this instance, an equivalent odds ratio >1 indicates higher odds, whereas an equivalent odds ratio <1 indicates lower odds, of an outcome.

Analysis software and code

We used the online version of the R statistical package called metaumbrella (https://metaumbrella.org/app) for data analyses.37 The corresponding code repository is publicly accessible at GitHub (https://github.com/cran/metaumbrella).37 Furthermore, the raw data are available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/8j2gt/), and a step-by-step analysis using metaumbrella is provided in supplementary table B.

Terminology

We used the terms “direct” and “inverse” to describe the direction of observed associations between ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes, with “direct” referring to a higher risk associated with greater exposure and “inverse” referring to a lower risk. We chose these terms over “positive” or “negative” associations to avoid ambiguous interpretations.

Credibility and quality assessment of evidence and methods

Credibility assessment of each pooled analysis using evidence classification criteria

Using the data derived from our reanalyses, such as the P value, I2 statistic, 95% prediction intervals, small study effects, excess significance bias, and largest study significance, we categorised each re-meta-analysed result of our umbrella review as convincing (“class I”), highly suggestive (“class II”), suggestive (“class III”), weak (“class IV”), or no evidence (“class V”) by following evidence classification criteria and previous umbrella reviews.24 25 26 36 We determined these classifications on the basis of the criteria outlined in supplementary table C.

Quality assessment of each pooled analysis using GRADE

We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system to evaluate the quality of evidence for each unique pooled analysis, and categorised them as either “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low” (supplementary table D).38 The GRADE approach initially considers all observational studies as evidence of low quality.38 Of the eight criteria put forth in the GRADE method, five have the potential to diminish confidence in the accuracy of effect estimates, leading to downgrading: risk of bias, inconsistency of results across studies, indirectness of evidence, imprecision, and publication bias.38 Additionally, three criteria are proposed to enhance confidence or upgrade it: a substantial effect size with no plausible confounders, a dose-response relation, and a conclusion that all plausible residual confounding would further support inferences regarding exposure effect.38

Quality assessment of individual meta-analysis studies using AMSTAR 2

We used the AMSTAR 2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews – second edition) quality assessment tool to evaluate the quality of the included meta-analysis studies (supplementary table E).39 This tool emphasises certain critical domains that could affect the reliability of a review.39 The critical domains considered pertinent to our review included pre-specified review methods, the adequacy of the literature search, the rationale for excluding specific studies, the risk of bias in the included studies, the appropriateness of the meta-analytic methods, and the consideration of bias when interpreting the results (domains bolded in supplementary table E).39 Following a recommendation from a recent review,39 we used the AMSTAR 2 tool to do a qualitative assessment, considering the potential impact of a low rating for each item, particularly the critical domains outlined in supplementary table E. This meant that we did not quantify individual item ratings or combine them to create an overall score.39

Patient and public involvement

The study and manuscript development did not involve patients or the public owing to the absence of funding for this research.

Results

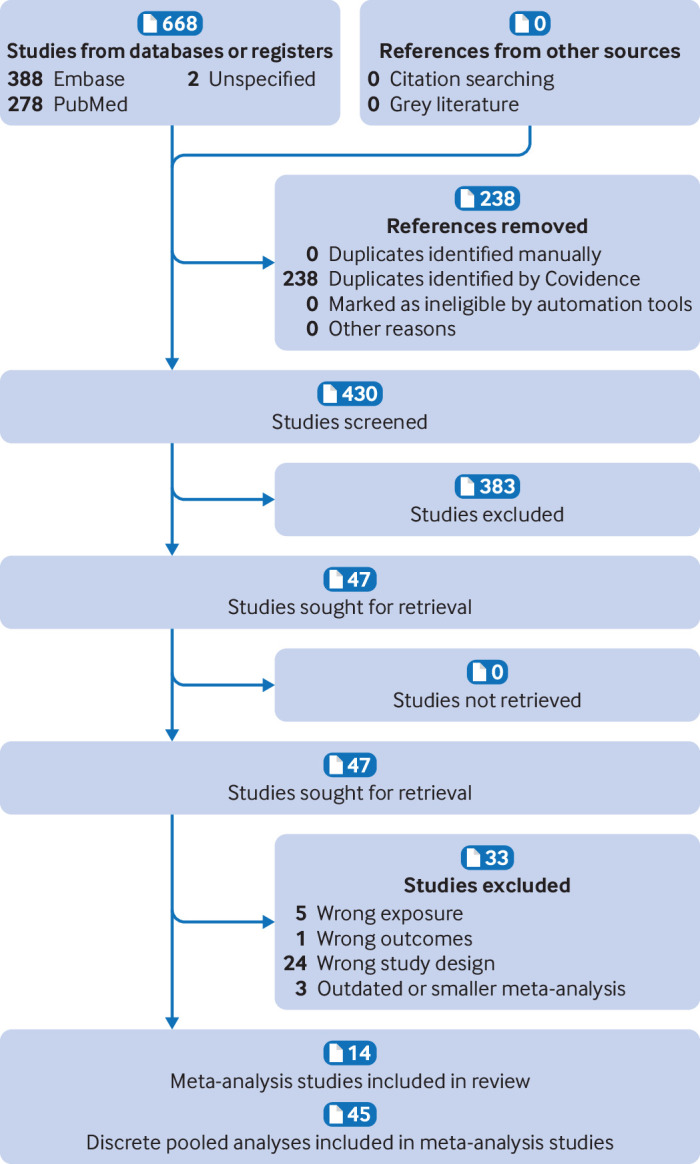

The systematic search identified 430 de-duplicated articles (fig 1). After applying the eligibility criteria, we included 14 meta-analysis studies with 45 distinct pooled analyses.17 18 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51

Fig 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart

Study characteristics

The range of adverse health outcomes reviewed across the 45 discrete pooled analyses included mortality, cancer, and mental, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic health outcomes. All meta-analysis studies were published in the past three years, and none was funded by a company involved in the production of ultra-processed foods. The number of original research articles included in the pooled analyses was four on average and ranged from two to nine. The sum total number of participants included across the pooled analyses was 9 888 373 (ranging from 111317 to 962 59348). Supplementary table F details the characteristics of the original research articles included in each of the pooled analyses, such as study design, population, and exposure measurement. Pooled analyses included estimates from original research articles that comprised either prospective cohorts (n=18), mixed study designs (n=15), or cross sectional designs (n=12). Most pooled analyses included adults as the main population, except for five, which included children and adolescents in examining mental health outcomes and respiratory conditions.18 49 50 In 87% of pooled analyses, estimates of exposure to ultra-processed food were obtained from a combination of tools, including food frequency questionnaires, 24 hour dietary recalls, and dietary history, as reported in the meta-analysis studies. Six pooled analyses, pertaining to heart disease related mortality,51 cancer related mortality,51 respiratory conditions,18 and non-alcohol fatty liver disease,46 included estimates of exposure from food frequency questionnaires alone.

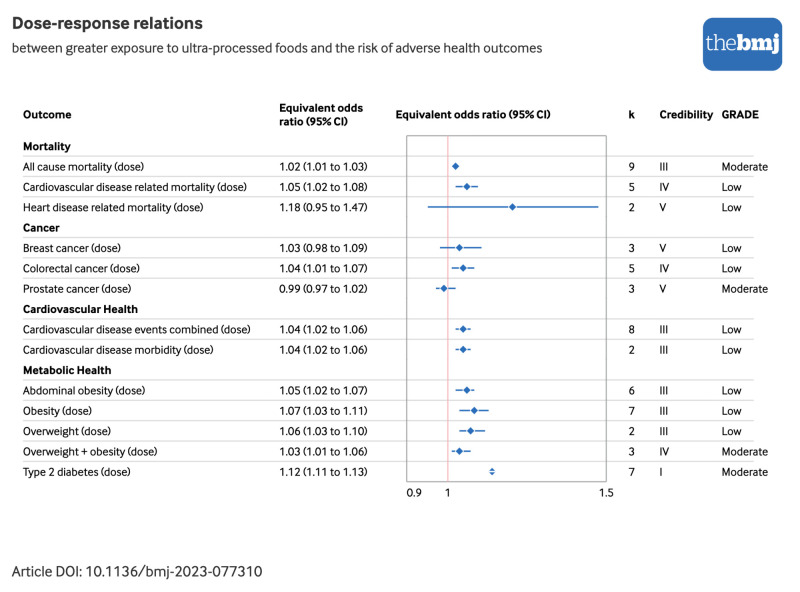

Each of the meta-analysis studies examined the non-dose-response associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and adverse health outcomes. However, an additional analysis involving dose-response modelling of the ultra-processed food exposure variable was conducted in 13 pooled analyses across five meta-analysis studies.40 42 43 47 51 The outcomes considered using this approach included all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease events, such as cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality, associated with each increase in daily servings of ultra-processed food.43 One meta-analysis study specifically pooled heart disease related deaths, such as ischaemic heart disease related mortality and cerebrovascular disease related mortality, with each 10% increase in total ultra-processed food exposure.51 Additionally, associations for other outcomes, such as abdominal obesity,42 overweight and obesity,42 type 2 diabetes,47 and breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers,40 were modelled on the basis of each 10% increase in ultra-processed food exposure.

Results of syntheses

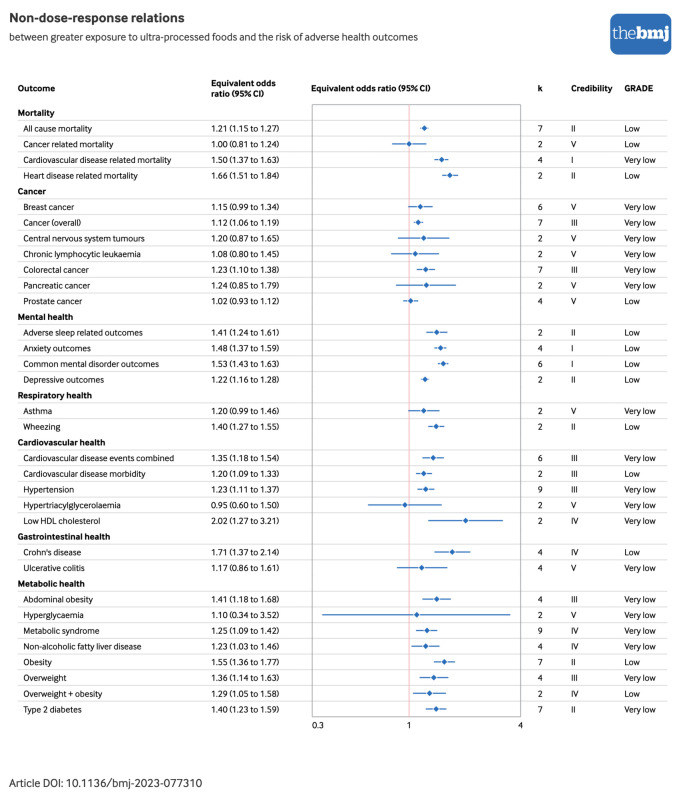

Figure 2 and figure 3 show the direction and sizes of effect estimates using equivalent odds ratios for both the non-dose-response and dose-response relations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and each adverse health outcome, respectively.

Fig 2.

Forest plot of non-dose-response relations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and risk of adverse health outcomes, with credibility and GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) quality assessments. Estimates are equivalent odds ratios,36 with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cardiovascular disease events combined=morbidity+mortality; credibility=evidence classification criteria assessment; HDL=high density lipoprotein; k=number of original research articles. An interactive version of this graphic is available at https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/16644020/

Fig 3.

Forest plot of dose-response relations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and risk of adverse health outcomes, with credibility and GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) quality assessments. Estimates are equivalent odds ratios,36 with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Cardiovascular disease events combined=morbidity+mortality; credibility=evidence classification criteria assessment; k=number of original research articles. An interactive version of this graphic is available at https://public.flourish.studio/visualisation/16645261/

On the basis of the random effects model, 32 (71%) distinct pooled analyses showed direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and a higher risk of adverse health outcomes at the significance level of P≤0.05 (supplementary table G). Additionally, of these combined analyses, 11 (34%) showed continued statistical significance when a more stringent threshold was applied (P<1×10−6) (data not shown). These included the incidence of all cause mortality,43 cardiovascular disease related mortality,43 heart disease related mortality,51 type 2 diabetes (dose-response and non-dose-response),47 and depressive outcomes,50 as well as the prevalence of anxiety and combined common mental disorder outcomes,50 adverse sleep related outcomes,49 and wheezing.18

We found evidence of moderate (I2=50-74.9%) to high (I2≥75%) heterogeneity in 13 (29%) and eight (18%) of the 45 discrete pooled analyses, respectively (supplementary table G). The 95% prediction intervals were statistically significant for seven (25%) of the 28 pooled analyses with three or more original research articles (supplementary table G), including direct associations of greater ultra-processed food exposure with higher risks of all cause mortality,43 cardiovascular disease related mortality,43 common mental disorder outcomes,50 Crohn’s disease,48 obesity,42 and type 2 diabetes (dose-response).47 Additionally, we found evidence of excess significance bias in nine (32%) of the 28 pooled analyses with three or more original research articles listed in supplementary table G. This bias was evident in associations between higher ultra-processed food exposure and all cause mortality (dose-response and non-dose-response),43 hypertension,44 abdominal obesity,42 metabolic syndrome,45 non-alcoholic fatty liver disease,46 obesity (dose-response and non-dose-response),42 and type 2 diabetes.47 Small study effects were evident in five (18%) of the 28 pooled analyses with three or more original research articles, as indicated in supplementary table G. We observed these effects in associations between higher ultra-processed food exposure and all cause mortality (dose-response and non-dose-response),43 breast cancer,40 metabolic syndrome,45 and obesity (dose-response).42

Effect estimates from the largest original research article were nominally statistically significant for 28 (62%) pooled analyses (supplementary table G) and pertained to associations of greater ultra-processed food exposure with higher risks of all cause mortality (dose-response and non-dose-response),43 cardiovascular disease related mortality (dose-response and non-dose-response),43 heart disease related mortality (dose-response and non-dose-response),51 central nervous system tumours,40 adverse sleep outcomes,49 common mental disorder outcomes,50 asthma,18 wheezing,18 cardiovascular disease events (dose-response and non-dose-response),43 low high density lipoprotein concentrations,17 abdominal obesity (dose-response and non-dose-response),42 hyperglycaemia,17 metabolic syndrome,45 non-alcoholic fatty liver disease,46 obesity and overweight (dose-response and non-dose-response),42 and type 2 diabetes (dose-response and non-dose-response).47

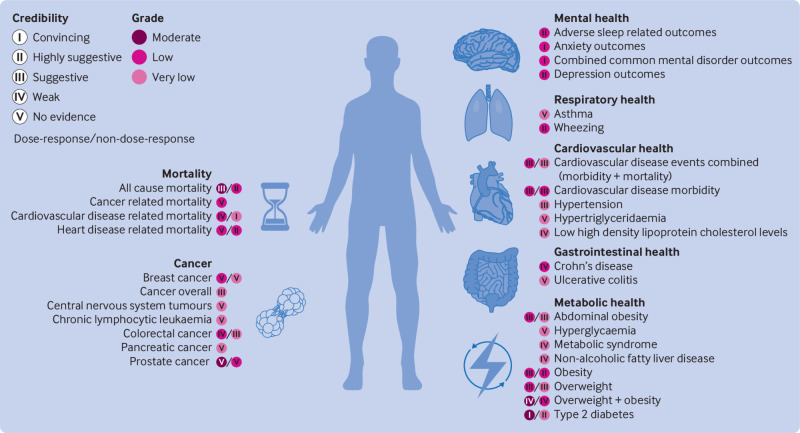

Credibility and GRADE quality assessments

Mortality

Pooled effect estimates from nine dose-response and seven non-dose-response cohorts showed direct associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risks of incident all cause mortality (dose-response risk ratio 1.02, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 1.03; credibility assessment class III; GRADE assessment moderate and non-dose-response risk ratio 1.21, 1.15 to 1.27; class II; low) 43 (fig 4; supplementary tables D and G). Four dose-response and five non-dose-response cohorts informed the synthesis of associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risks of incident cardiovascular disease related mortality (dose-response risk ratio 1.05, 1.02 to 1.08; class IV; low and non-dose-response risk ratio 1.50, 1.37 to 1.63; class I; very low).43 Effect estimates from two cohorts were pooled and showed limited evidence supporting direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and a higher risk of incident cancer related mortality (hazard ratio 1.00, 0.81 to 1.24; class V; low).51 We found further limited evidence for an association between greater ultra-processed food exposure and incident heart disease related mortality (dose-response hazard ratio 1.18, 0.95 to 1.47; class V; low and non-dose-response hazard ratio 1.66, 1.51 to 1.84; class II; low).51

Fig 4.

Credibility and GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) ratings for associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and risks of each adverse health outcome

Cancer

Pooled analyses from seven cohort studies showed direct associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risks of incident cancer overall (hazard ratio 1.12, 1.06 to 1.19; class III; very low).41 Synthesised analyses including mixed cohort and case-control study designs additionally showed direct associations with a risk of colorectal cancer (dose-response odds ratio 1.04, 1.01 to 1.07; class IV; low and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.23, 1.10 to 1.38; class III; very low).40

We found limited evidence for pooled analyses, including mixed cohort and case-control study designs, of the association between greater ultra-processed food exposure and higher risks of breast cancer (dose-response odds ratio 1.03, 0.98 to 1.09; class V; low and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.15, 0.99 to 1.34; class V; very low),40 central nervous system tumours (odds ratio 1.20, 0.87 to 1.65; class V; very low), chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (odds ratio 1.08, 0.80 to 1.45; class V; very low), pancreatic cancer (odds ratio 1.24, 0.85 to 1.79; class V; very low), and prostate cancer (dose-response odds ratio 0.99, 0.97 to 1.02; class V; moderate and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.02, 0.93 to 1.12; class V; low).

Mental health

Examining data from two to four cross sectional designs, we found evidence supporting direct associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and a higher risk of the prevalence of adverse sleep related outcomes (odds ratio 1.41, 1.24 to 1.61; class II; low),49 as well as anxiety outcomes (odds ratio 1.48, 1.37 to 1.59; class I; low).50 We observed similar associations in separate assessments of prevalent combined common mental disorder outcomes across six cross sectional designs (odds ratio 1.53, 1.43 to 1.63; class I; low)50 and incident depressive outcomes across two cohorts (odds ratio 1.22, 1.16 to 1.28; class II; low).50

Respiratory health

Pooled analyses that included two cross sectional studies provided limited evidence of an association between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and risks of prevalent asthma (risk ratio 1.20, 0.99 to 1.46; class V; very low)18 and wheezing (risk ratio 1.40, 1.27 to 1.55; class II; low).18

Cardiovascular health

Pooled analyses from six cohorts showed direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and higher risks of incident cardiovascular disease events such as morbidity and mortality (dose-response risk ratio 1.04, 1.02 to 1.06; class III; low and non-dose-response risk ratio 1.35, 1.18 to 1.54; class III; very low),43 as well as incident cardiovascular disease morbidity (dose-response risk ratio 1.04, 1.02 to 1.06; class III; low and non-dose-response risk ratio 1.20, 1.09 to 1.33; class III; low).43 The higher risk of hypertension associated with greater ultra-processed food exposure was assessed using data from nine mixed cohorts and cross sectional study designs (odds ratio 1.23, 1.11 to 1.37; class III; very low).44 We found weak to no evidence for associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and hypertriglyceridaemia (odds ratio 0.95, 0.60 to 1.50; class V; very low)17 and low high density lipoprotein concentrations (odds ratio 2.02, 1.27 to 3.21; class IV; very low).17

Gastrointestinal health

We found weak or no evidence in pooled analyses incorporating data from four cohorts for associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risks of incident Crohn’s disease (hazard ratio 1.71, 1.37 to 2.14; class IV; low)48 and ulcerative colitis (hazard ratio 1.17, 0.86 to 1.61; class V; very low).48

Metabolic health

The risk of abdominal obesity was examined by synthesising effect estimates from mixed cohort and cross sectional study designs, which showed direct associations with greater ultra-processed food exposure (dose-response odds ratio 1.05, 1.02 to 1.07; class III; low and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.41, 1.18 to 1.68; class III; very low).42 We found weak to no evidence for associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and hyperglycaemia (odds ratio 1.10, 0.34 to 3.52; class V; very low),17 metabolic syndrome (risk ratio 1.25, 1.09 to 1.42; class IV; very low),45 non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (risk ratio 1.23, 1.03 to 1.46; class IV; very low),46 and overweight and obesity (assessed together: dose-response odds ratio 1.03, 1.01 to 1.06; class IV; moderate and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.29, 1.05 to 1.58; class IV; low).42 Effect estimates from four cross sectional studies informed pooled analyses of direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and higher risk of the prevalence of overweight (dose-response odds ratio 1.06, 1.03 to 1.10; class III; low and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.36, 1.14 to 1.63; class III; very low).42 Pooled analyses including seven cross sectional study designs further showed direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and a higher prevalence of obesity (dose-response odds ratio 1.07, 1.03 to 1.11; class III; low and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.55, 1.36 to 1.77; class II; low).42 The combined analysis of seven cohorts showed direct associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risk of incident type 2 diabetes (dose-response risk ratio 1.12, 1.11 to 1.13; class I; moderate and non-dose-response odds ratio 1.40, 1.23 to 1.59; class II; very low).47

Quality assessment of individual meta-analysis studies using AMSTAR 2 tool

Although all of the authors of the meta-analysis studies used satisfactory literature search techniques (AMSTAR critical item 4) and accounted for the potential risk of bias in original research articles when interpreting and discussing their results (AMSTAR critical item 9), we considered the overall confidence in the results of seven meta-analysis studies to be low owing to lack of clarity as to whether the review methods were established before the conduct of the review (AMSTAR critical item 2) (supplementary table E).17 40 41 42 44 45 51 Based on non-critical items, the confidence in the results of all meta-analysis studies was assessed as moderate. Notably, the most considerable limitations, for which all meta-analysis studies scored zero, were related to the review authors’ failure to provide an explanation for their selection of study designs for inclusion in the review (AMSTAR item 3) and their omission of information on funding sources for the studies included in the review (AMSTAR item 10).39

Discussion

Principal findings

Our umbrella review provides a comprehensive overview and evaluation of the evidence for associations between dietary exposure to ultra-processed foods and various adverse health outcomes. Our review included 45 distinct pooled analyses, encompassing a total population of 9 888 373 participants and spanning seven health parameters related to mortality, cancer, and mental, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic health outcomes. Across the pooled analyses, greater exposure to ultra-processed foods, whether measured as higher versus lower consumption, additional servings per day, or a 10% increment, was consistently associated with a higher risk of adverse health outcomes (71% of outcomes).

Considering the evidence classification criteria assessments, we graded 9% of the pooled analyses as providing convincing evidence (class I), including those measuring risks of cardiovascular disease related mortality, common mental disorder outcomes, and type 2 diabetes (dose-response) (fig 4). We graded 16% of pooled analyses (all non-dose-response) as providing highly suggestive evidence (class II), encompassing risks of all cause mortality, heart disease related mortality, adverse sleep related outcomes, wheezing, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. We graded approximately 29% of the pooled analyses as providing suggestive evidence (class III), covering a range of conditions from risks of abdominal obesity to overweight, with 18% graded as weak evidence (class IV), encompassing outcomes such as risks of colorectal cancer and overweight and obesity (evaluated together as single outcome). We graded the remaining 29% of pooled analyses as lacking evidence (class V), spanning conditions from asthma to ulcerative colitis. As previously noted, moderate to high levels of heterogeneity were observed across 45% of pooled analyses. Using GRADE assessments, which initially assign observational epidemiological studies as “low” quality evidence,38 approximately 29% of the pooled analyses remained unchanged, indicating that no additional concerns were identified based on GRADE criteria, with a further 9% upgraded to a “moderate” rating owing to a dose-response gradient (fig 4). Dose-response pooled analyses upgraded to “moderate” quality evidence related to all cause mortality, prostate cancer, overweight and obesity (assessed together), and type 2 diabetes. Associations were downgraded largely owing to inconsistencies or heterogeneity in the effect estimates found across the original research articles or owing to imprecision (that is, wide confidence intervals).

The heterogeneity and imprecision noted across several of the pooled analyses, as shown by both the evidence classification criteria and GRADE assessments, may be partly explained by the treatment of different effect estimates derived from original research articles (hazard ratios, odds ratios, and risk ratios) as approximately equivalent in various meta-analysis studies.40 42 43 45 47 Such variations in scales may introduce heterogeneity and reduce precision in pooled estimates, even if the original research articles share conceptual similarities in exposures and outcomes.52 Moreover, the synthesis of results based on three or fewer original research articles may contribute to heterogeneity and imprecision,53 affecting outcomes assessed in our review such as certain cancers, asthma, and intermediate cardiometabolic risk factors. Although the pooled analyses relating to these outcomes were rated as having no or low quality evidence based on the evidence classification criteria and GRADE assessments, this does not necessarily negate the potential for an association, particularly as more data may become available in the future. Furthermore, considering the overall body of evidence, 93% of pooled analyses indicated point estimates in the same direction (greater than one) (fig 2 and fig 3). The presence of 95% confidence intervals that included the null value in 24% of these pooled analyses signifies some uncertainty in the data, which may be partly due to insufficient sample size, particularly in analyses with a small number of original research articles and results showing wide confidence intervals.54 This underscores the importance of conducting additional original research and subsequent meta-analyses in the respective disease areas.

Potential mechanisms of action

Understanding the aspects of ultra-processed dietary patterns that link them to poor health and early death requires more research.12 55 The available evidence indicates that ultra-processed foods differ from unprocessed and minimally processed foods in several aspects, potentially explaining their plausible links with adverse health outcomes. These differences include poorer nutrient profiles, the displacement of non-ultra-processed foods from the diet, and alterations to the physical structure of consumables through intensive ultra-processing. More specifically, diets rich in ultra-processed foods are associated with markers of poor diet quality, with higher levels of added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium; higher energy density; and lower fibre, protein, and micronutrients.6 56 Ultra-processed foods displace more nutritious foods in diets, such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds,6 resulting in reduced intakes of beneficial bioactive compounds that are present in these foods, including polyphenols or phytoestrogens such as enterodiol.57 58 Such nutrient-poor dietary profiles have been implicated in the prevalence and incidence of chronic diseases through various pathways, including inflammatory mechanisms.13 14 16

The adverse health outcomes associated with ultra-processed foods may not be fully explained by their nutrient composition and energy density alone but also by physical and chemical properties associated with industrial processing methods, ingredients, and by-products. Firstly, alterations in the food matrix during intensive processing, also known as dietary reconstitution, may affect digestion, nutrient absorption, and feelings of satiety.59 Secondly, emerging evidence in humans shows links between exposure to additives, including non-sugar sweeteners, emulsifiers, colorants, and nitrates/nitrites, and detrimental health outcomes.60 61 62 63 64 65 A recent review of experimental research found that ultra-processed weight loss formulations composed of ostensibly balanced nutrient profiles but containing different additives, including non-sugar sweeteners, may have adverse effects on the gut microbiome—which is thought to play an important function in many of the diseases studied here—and related inflammation.66 The World Health Organization recently warned against the ongoing use of sugar substitutes for weight control or non-communicable illnesses,67 and, according to its new report, non-sugar sweeteners may also elevate the risk of cardiometabolic diseases and mortality.67 In addition, citing “limited evidence” in humans, the International Agency for Research on Cancer recently classified the non-sugar sweetener aspartame as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” (group 2B).68 A growing body of data shows instances of exposure to combinations of multiple additives, which may have potential “cocktail effects” with greater implications for human health than exposure to a single additive.69 Thirdly, the intensive industrial processing of food may produce potentially harmful substances that have been linked to higher risks of chronic inflammatory diseases, including acrolein, acrylamide, advanced glycation end products, furans, heterocyclic amines, industrial trans-fatty acids, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.12 70 Finally, ultra-processed foods can contain contaminants with health implications that migrate from packaging materials, such as bisphenols, microplastics, mineral oils, and phthalates.12

Experimental evidence indicates a robust causal relation between ultra-processed diets and increased energy intake and weight gain (approximately 500 kcal (2000 kJ) per day and 0.9 kg during the ultra-processed diet).71 Other experimental evidence has also shown that using the Nova food classification system for nutritional counselling and adjunctive to physical activity effectively prevents excessive weight gain in pregnant women with high body mass index.72 The mechanisms contributing to the excess consumption effect of diets rich in ultra-processed foods seem to involve the nature of the energy source—specifically, whether it comes from solid foods or beverages.71 Furthermore, the greater energy density, faster eating rate, and hyper-palatability attributed to ultra-processed foods are regarded as important factors influencing this effect.73 The extensive marketing strategies used by ultra-processed food manufacturers, which involve visually captivating packaging with eye catching designs and health related assertions, have also been suggested as a potential contributing factor to excessive consumption.74

Strengths and limitations of study and comparisons with other studies

Recognising the importance of establishing causality, we acknowledge that further randomised controlled trials are needed, particularly for outcomes for which strong meta-analytic epidemiological evidence exists, such as cardiometabolic disorder and common mental disorder outcomes. However, only short term trials testing the effect of ultra-processed food exposure on intermediate outcomes (such as alterations to body weight, insulin resistance, depressive and anxiety symptoms, gut microbiome, and inflammation) would be feasible. Setting up trials testing the effect of long term exposure to interventions with suspected deleterious properties (that is, diets rich in ultra-processed foods) on hard disease endpoints such as cardiovascular disease or cancer will not be possible, for obvious ethical reasons. In this context, our umbrella review of extant observational epidemiological research provides complementary insights and has implications for public health, especially in light of the current debate about tackling (or not) exposure to ultra-processed foods through public health measures. It stands as the first comprehensive synthesis of current evidence derived from meta-analyses of epidemiological studies, exploring the associations between dietary exposure to ultra-processed foods and various adverse health outcomes. We used rigorous systematic methods, including duplicate study selection and data extraction, alongside the evidence classification criteria and GRADE assessments, to evaluate the credibility and quality of the pooled analyses. An additional strength of our review is that we reviewed the competing interests and funding disclosures of the included meta-analysis studies, with none being funded by companies involved in the production of ultra-processed foods.

One limitation of umbrella reviews in general is their high level overview. As a result, we did not consider specific confounder or mediator adjustments and sensitivity analyses as part of our review, but these may be important factors, particularly in the context of ultra-processed foods. The consumption of ultra-processed foods is linked to a lower intake of unprocessed or minimally processed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and seafood.6 This raises the question of whether the associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and poorer health are due to an overall unhealthy dietary pattern. Although such analyses were beyond the scope of our review, which focused on evaluating overall associations between exposure to ultra-processed foods and adverse health outcomes, we note that a recent meta-analysis found that adjusting for diet quality or patterns does not change the consistent evidence for direct associations between greater ultra-processed food exposure and a higher risk of adverse health outcomes (as per inference criteria and sizes of effect estimates).75 Furthermore, the inclusion of original research articles with different methods of assessing ultra-processed food intake, such as dietary history, food frequency questionnaires, food records, and 24 hour dietary recalls, introduces an inevitable measurement bias regardless of whether validated methods were applied.76 Considering that observational epidemiological studies have inherent limitations is also important, with residual confounding being perhaps most pertinent.77 However, the consistent findings across most pooled analyses in our review support the notion that residual confounding does not fully explain the observed associations.

Although our umbrella review provides a systematic synthesis of the role of ultra-processed dietary patterns in chronic disease outcomes, a related consideration is the possible heterogeneity of associations between subgroups and subcategories of ultra-processed foods and chronic disease outcomes. A meta-analysis by Chen and colleagues (2023), included in our review, established a clear link between overall consumption of ultra-processed foods and a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, consistently observed across multiple cohorts.47 However, while certain subcategories of ultra-processed foods further showed higher risk, others were inversely associated, such as ultra-processed cereals, dark/wholegrain bread, packaged sweet and savoury snacks, fruit based products and yoghurt, and dairy based desserts.47 These findings underscore the complexity of the relation between ultra-processed foods and adverse health. Nevertheless, although some subcategories of ultra-processed items may have better nutrient and ingredient profiles, the overall consumption of ultra-processed foods remains consistently associated with a higher risk of chronic diseases, as evidenced by our review. Some people have argued that understanding the differences within subcategories of ultra-processed foods may aid consumers in adopting a healthier dietary pattern compared with maximally reducing their consumption on the whole.78 However, others propose that the focus should be on the overall quality of the diet, including all ultra-processed foods, and its link to higher disease risk, rather than specific subcategories or individual products.79

When considering the above and examining subcategories of ultra-processed foods, composite interactions between various consumables within broader dietary patterns are unaccounted for. This limitation may partially account for differences in the strength of evidence observed in our review compared with another recent umbrella review focusing on dietary sugar consumption, including sugar sweetened beverages, a commonly consumed subcategory of ultra-processed foods.25 That review found no convincing (class I) evidence for adverse health outcomes linked to dietary sugar or sugar sweetened beverage consumption.25 In contrast, our umbrella review shows compelling evidence (class I) that supports direct associations between greater dietary exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risks of adverse health outcomes spanning cardiometabolic diseases, common mental disorders, and mortality. These findings support recommendations to consider overall diet quality in nutritional epidemiology,79 and they suggest that higher consumption of ultra-processed foods within broader dietary patterns may have synergistic or compounded consequences compared with lower intakes, as hypothesised elsewhere.12 13 14 15

Policy implications

Organisations such as the American Heart Association have cautiously advised people to choose unprocessed and minimally processed foods over ultra-processed foods, noting the absence of a widely accepted definition for ultra-processed foods.80 Although various food classification systems have been developed to classify foods on the basis of processing related criteria,81 82 83 84 85 the most commonly used classification system worldwide is the Nova food classification system.86 Furthermore, Nova has received recognition from authoritative reports by the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations and the Pan American Health Organization of the WHO.87 88 89 90 91 A recent statement from the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) evaluated the Nova classification system among others and concluded that Nova is the only suitable classification for potential use in the country.92 However, SACN expressed concerns about various key points. For example, it highlighted that the available studies applying the Nova system are primarily epidemiological in nature and may lack adequate consideration of confounding factors or covariates92. Criticisms of Nova as a classification system also exist, with concerns raised about its possible imprecision and inconsistency among evaluators.93 94 95 96 In contrast, more recent assessments show acceptable construct validity and strong agreement among coders,97 98 with the definitions and examples provided by the Nova system deemed adequate in classifying more than 70% of the food items reported in food frequency questionnaires from various cohorts from the US,99 as well as more than 90% of the food items reported in 24 hour dietary recalls from participants in a national Brazilian dietary survey.100 Recent efforts including best practice guidelines have further focused on improving the efficiency and transparency of the categorisation process for Nova food groups, which ultimately aim to enhance the accuracy of effect estimates.101

Public health measures promoting a reduction or avoidance of ultra-processed products have already been implemented most comprehensively in Latin American countries. These strategies include octagonal front-of-pack warning labels, taxes on sugar sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods, marketing restrictions, and bans in schools.102 103 104 Since the introduction of the recommendation to avoid ultra-processed foods in the 2014 Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population,105 seven additional countries have adopted the term and similar recommendations.106 Furthermore, similar strategies for paediatric development and prevention of liver disease have also been recommended by the UK’s First Steps Nutrition Trust and the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Lancet Commission, respectively.107 108 We also note that WHO and the International Agency for Research on Cancer endorse public health strategies to limit the intake of components commonly present in ultra-processed foods, including high levels of added sugar and non-sugar sweeteners.67 68 109 Importantly, sustained progress in implementing these strategies and the exploration of novel approaches mean that stakeholders need to be responsive and sensitive to factors that influence access to fresh produce and food choices, including the relatively greater time, effort, and (in some contexts) cost of preparing non-ultra-processed food.95

Conclusions

This umbrella review reports a higher risk of adverse health outcomes associated with ultra-processed food exposure. The strongest available evidence pertained to direct associations between greater exposure to ultra-processed foods and higher risks of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease related mortality, common mental disorder outcomes, overweight and obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Evidence for the associations of ultra-processed food exposure with asthma, gastrointestinal health, some cancers, and intermediate cardiometabolic risk factors remains limited and warrants further investigation. Coupled with existing population based strategies, we recommend urgent mechanistic research and the development and evaluation of comprehensive population based and public health strategies, including government led policy frameworks and dietary guidelines, aimed at targeting and reducing dietary exposure to ultra-processed foods for improved human health.

What is already known on this topic

Multiple meta-analyses have aimed to consolidate original epidemiological research investigating associations between ultra-processed food and adverse health outcomes

However, no comprehensive umbrella review has been conducted to provide a broad perspective and evaluate the meta-analytic evidence in this area

What this study adds

This umbrella review found consistent evidence of a higher risk of adverse health outcomes associated with greater ultra-processed food exposure

Convincing and highly suggestive evidence (classes I and II) related to early death and adverse cardiometabolic and mental health

These findings support urgent mechanistic research and public health actions that seek to target and minimise ultra-processed food consumption for improved population health

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary tables

Contributors: MML was involved in conceptualisation, literature searching, data curation, project administration, resources, and writing the original draft of the manuscript. EG, SD, DNA, AJM, and SG were involved in conceptualisation and data curation. TS was involved in data visualisation. PB, ML, CMR, BS, MT, FNJ, and AO were involved in conceptualisation. WM was involved in conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, and data visualisation. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript. MML is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work was not funded.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: MML, EG, DNA, AJM, SG, FNJ, AO, and WM are affiliated with the Food & Mood Centre, Deakin University, which has received research funding support from Be Fit Food, Bega Dairy and Drinks, and the a2 Milk Company and philanthropic research funding support from the Waterloo Foundation, Wilson Foundation, the JTM Foundation, the Serp Hills Foundation, the Roberts Family Foundation, and the Fernwood Foundation; MML is secretary for the Melbourne Branch Committee of the Nutrition Society of Australia (unpaid) and has received travel funding support from the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research, the Nutrition Society of Australia, the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine, and the Gut Brain Congress and is an associate investigator for the MicroFit Study, an investigator-led randomised controlled trial exploring the effect of diets with varying levels of industrial processing on gut microbiome composition and partially funded by Be Fit Food (payment received by the Food and Mood Centre, Deakin University); AMJ is secretary for the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research (unpaid) and an associate investigator for the MicroFit Study; SG is affiliated with Deakin University, which has received grant funding support from a National Health and Medical Research Council Synergy Grant (#GNT1182301) and Medical Research Future Fund Cardiovascular Health Mission (#MRF2022907), is affiliated with Monash University, which has received grant funding support from Medical Research Future Fund Consumer-led research (#MRF2022907), is secretary for the Australian Cardiovascular Health and Rehabilitation Association—Victoria and Tasmania—(unpaid), and has received travel funding support from the Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation and SOLVE-CHD (solving the long-standing evidence-practice gap associated with cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease); PB has received funding from an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship award (project number #FT220100690) and from Bloomberg Philanthropies; ML is affiliated with the Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, which has received grant funding support from the Australian Research Council (#DP190101323), and has received royalties or license funding from Allen and Unwin (Public Health Nutrition: from Principles to Practice) and Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group (Healthy and Sustainable Food Systems) and consultation and remuneration funding support from WHO and Food Standards Australia New Zealand (in his role as a board member); CMR is affiliated with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins University, which have received grant funding support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bloomberg American Health Initiative, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, was chair of the Data and Safety Monitoring Boards for the SUPER Trial: Effect of Dietary Sodium Reduction in Kidney Disease Patients with Albuminuria and the ADEPT Trial: A Clinical Trial of Low-Carbohydrate Dietary Pattern on Glycemic Outcomes, was on the Editorial Board of Diabetes Care (unpaid), was the immediate past chair for the Early Career Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health, American Heart Association (unpaid), and the Nutritional Epidemiology Research Interest Section of the American Society for Nutrition (unpaid), and has received funding support as an associate editor of Diabetes Care and editorial fellow of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology; FNJ has received fellowship funding support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (#1194982) and payment or honorariums for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from the Malaysian Society of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, JNPN Congress, American Nutrition Association, Personalised Nutrition Summit, and American Academy of Craniofacial Pain, is a Scientific Advisory Board member of Dauten Family Centre for Bipolar Treatment Innovation (unpaid) and Zoe Nutrition (unpaid), has written two books for commercial publication on the topic of nutritional psychiatry and gut health, and is the principal investigator for the MicroFit Study; AO has received fellowship funding support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (#2009295) and is affiliated with Deakin University, which has received grant funding support from the Medical Research Future Fund, Dasman Diabetes Institute, MTP Connect—Targeted Translation Research Accelerator Program, the National Health and Medical Research Council, Barwon Health, and the Waterloo Foundation, and has received funding support for academic editing and as a grant reviewer from SLACK Incorporated (Psychiatric Annals) and the National Health and Medical Research Council, respectively, and travel funding support from the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research; WM is president of the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research (unpaid), has received fellowship funding support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (#2008971) and Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia, consultation and remuneration funding support from Nutrition Research Australia and ParachuteBH, and travel funding support from the Nutrition Society of Australia, Mind Body Interface Symposium, and VitaFoods, and was the acting principal investigator and is an associate investigator for the MicroFit Study.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: We will share our review findings with academic, clinical, policy, and public audiences post-publication through various channels, including conferences as well as personal and institutional media hosted primarily by Deakin University and the Food and Mood Centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data availability statement

To access additional data from this study, the code repository corresponding to the online version of the R statistical package, metaumbrella, can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/cran/metaumbrella. The raw data are available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/8j2gt/, and a step-by-step analysis using metaumbrella usage is provided in supplementary table B. For further assistance or inquiries, please contact the corresponding author at m.lane@dealin.edu.au.

References

- 1. Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Lawrence M, et al. Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food and Agriculture Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr 2019;22:936-41. 10.1017/S1368980018003762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev 2020;21:e13126. 10.1111/obr.13126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Cannon G, Ng SW, Popkin B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev 2013;14(Suppl 2):21-8. 10.1111/obr.12107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marino M, Puppo F, Del Bo’ C, et al. A Systematic Review of Worldwide Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods: Findings and Criticisms. Nutrients 2021;13:2778. 10.3390/nu13082778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martini D, Godos J, Bonaccio M, Vitaglione P, Grosso G. Ultra-Processed Foods and Nutritional Dietary Profile: A Meta-Analysis of Nationally Representative Samples. Nutrients 2021;13:3390. 10.3390/nu13103390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011;378:804-14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mendes C, Miranda L, Claro R, Horta P. Food marketing in supermarket circulars in Brazil: An obstacle to healthy eating. Prev Med Rep 2021;21:101304. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gupta S, Hawk T, Aggarwal A, Drewnowski A. Characterizing Ultra-Processed Foods by Energy Density, Nutrient Density, and Cost. Front Nutr 2019;6:70. 10.3389/fnut.2019.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luiten CM, Steenhuis IHM, Eyles H, Ni Mhurchu C, Waterlander WE. Ultra-processed foods have the worst nutrient profile, yet they are the most available packaged products in a sample of New Zealand supermarkets. Public Health Nutr 2016;19:530-8. 10.1017/S1368980015002177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poti JM, Braga B, Qin B. Ultra-processed Food Intake and Obesity: What Really Matters for Health-Processing or Nutrient Content? Curr Obes Rep 2017;6:420-31. 10.1007/s13679-017-0285-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Srour B, Kordahi MC, Bonazzi E, Deschasaux-Tanguy M, Touvier M, Chassaing B. Ultra-processed foods and human health: from epidemiological evidence to mechanistic insights. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:1128-40. 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00169-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fardet A. Characterization of the Degree of Food Processing in Relation With Its Health Potential and Effects. Adv Food Nutr Res 2018;85:79-129. 10.1016/bs.afnr.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martínez Leo EE, Peñafiel AM, Hernández Escalante VM, Cabrera Araujo ZM. Ultra-processed diet, systemic oxidative stress, and breach of immunologic tolerance. Nutrition 2021;91-92:111419. 10.1016/j.nut.2021.111419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tristan Asensi M, Napoletano A, Sofi F, Dinu M. Low-Grade Inflammation and Ultra-Processed Foods Consumption: A Review. Nutrients 2023;15:1546. 10.3390/nu15061546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marx W, Lane M, Hockey M, et al. Diet and depression: exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:134-50. 10.1038/s41380-020-00925-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pagliai G, Dinu M, Madarena MP, Bonaccio M, Iacoviello L, Sofi F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2021;125:308-18. 10.1017/S0007114520002688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lane MM, Davis JA, Beattie S, et al. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes Rev 2021;22:e13146. 10.1111/obr.13146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Monteiro CA, Astrup A. Does the concept of “ultra-processed foods” help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? YES. Am J Clin Nutr 2022;116:1476-81. 10.1093/ajcn/nqac122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Astrup A, Monteiro CA. Does the concept of “ultra-processed foods” help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? NO. Am J Clin Nutr 2022;116:1482-8. 10.1093/ajcn/nqac123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morgan RL, Whaley P, Thayer KA, Schünemann HJ. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ Int 2018;121:1027-31. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Monteiro CA. Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:729-31. 10.1017/S1368980009005291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Veronese N, Demurtas J, Thompson T, et al. Effect of low-dose aspirin on health outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2020;86:1465-75. 10.1111/bcp.14310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Y, Chen Z, Chen B, et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: umbrella review. BMJ 2023;381:e071609. 10.1136/bmj-2022-071609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Belbasis L, Bellou V, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP, Tzoulaki I. Environmental risk factors and multiple sclerosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:263-73. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70267-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J 2003;20:54-60. 10.1136/emj.20.1.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:97-111. 10.1002/jrsm.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. , eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2009;172:137-59. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA. An exploratory test for an excess of significant findings. Clin Trials 2007;4:245-53. 10.1177/1740774507079441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:1046-55. 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Markozannes G, Aretouli E, Rintou E, et al. An umbrella review of the literature on the effectiveness of psychological interventions for pain reduction. BMC Psychol 2017;5:31. 10.1186/s40359-017-0200-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health 2018;21:95-100. 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gosling CJ, Solanes A, Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. metaumbrella: the first comprehensive suite to perform data analysis in umbrella reviews with stratification of the evidence. BMJ Ment Health 2023;26:e300534. 10.1136/bmjment-2022-300534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383-94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lian Y, Wang G-P, Chen G-Q, Chen HN, Zhang GY. Association between ultra-processed foods and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Nutr 2023;10:1175994. 10.3389/fnut.2023.1175994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Isaksen IM, Dankel SN. Ultra-processed food consumption and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr 2023;42:919-28. 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moradi S, Entezari MH, Mohammadi H, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and adult obesity risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023;63:249-60. 10.1080/10408398.2021.1946005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yuan L, Hu H, Li T, et al. Dose-response meta-analysis of ultra-processed food with the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: evidence from prospective cohort studies. Food Funct 2023;14:2586-96. 10.1039/D2FO02628G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang M, Du X, Huang W, Xu Y. Ultra-processed Foods Consumption Increases the Risk of Hypertension in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2022;35:892-901. 10.1093/ajh/hpac069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shu L, Zhang X, Zhou J, Zhu Q, Si C. Ultra-processed food consumption and increased risk of metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Nutr 2023;10:1211797. 10.3389/fnut.2023.1211797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Henney AE, Gillespie CS, Alam U, Hydes TJ, Cuthbertson DJ. Ultra-Processed Food Intake Is Associated with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023;15:2266. 10.3390/nu15102266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen Z, Khandpur N, Desjardins C, et al. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Three Large Prospective U.S. Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care 2023;46:1335-44. 10.2337/dc22-1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Narula N, Chang NH, Mohammad D, et al. Food Processing and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;21:2483-2495.e1. 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Delpino FM, Figueiredo LM, Flores TR, et al. Intake of ultra-processed foods and sleep-related outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition 2023;106:111908. 10.1016/j.nut.2022.111908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lane MM, Gamage E, Travica N, et al. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022;14:2568. 10.3390/nu14132568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Suksatan W, Moradi S, Naeini F, et al. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Adult Mortality Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of 207,291 Participants. Nutrients 2021;14:174. 10.3390/nu14010174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Higgins J, Li T, Deeks J, et al. Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 63 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. When Does it Make Sense to Perform a Meta-Analysis? In: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR, eds Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, 2009. 10.1002/9780470743386.ch40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jones SR, Carley S, Harrison M. An introduction to power and sample size estimation. Emerg Med J 2003;20:453-8. 10.1136/emj.20.5.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tobias DK, Hall KD. Eliminate or reformulate ultra-processed foods? Biological mechanisms matter. Cell Metab 2021;33:2314-5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Machado P, Cediel G, Woods J, et al. Evaluating intake levels of nutrients linked to non-communicable diseases in Australia using the novel combination of food processing and nutrient profiling metrics of the PAHO Nutrient Profile Model. Eur J Nutr 2022;61:1801-12. 10.1007/s00394-021-02740-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Coletro HN, Bressan J, Diniz AP, et al. Habitual polyphenol intake of foods according to NOVA classification: implications of ultra-processed foods intake (CUME study). Int J Food Sci Nutr 2023;74:338-49. 10.1080/09637486.2023.2190058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martínez Steele E, Monteiro CA. Association between Dietary Share of Ultra-Processed Foods and Urinary Concentrations of Phytoestrogens in the US. Nutrients 2017;9:209. 10.3390/nu9030209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fardet A. Minimally processed foods are more satiating and less hyperglycemic than ultra-processed foods: a preliminary study with 98 ready-to-eat foods. Food Funct 2016;7:2338-46. 10.1039/C6FO00107F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Debras C, Chazelas E, Srour B, et al. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003950. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]