Abstract

Background and Aims

Liver iron overload can induce hepatic expression of bone morphogenic protein (BMP) 6 and activate the BMP/SMAD pathway. However, serum iron overload can also activate SMAD but does not induce BMP6 expression. Therefore, the mechanisms through which serum iron overload activates the BMP/SMAD pathway remain unclear. This study aimed to clarify the role of SMURF1 in serum iron overload and the BMP/SMAD pathway.

Methods

A cell model of serum iron overload was established by treating hepatocytes with 2 mg/mL of holo-transferrin (Holo-Tf). A serum iron overload mouse model and a liver iron overload mouse model were established by intraperitoneally injecting 10 mg of Holo-Tf into C57BL/6 mice and administering a high-iron diet for 1 week followed by a low-iron diet for 2 days. Western blotting and real-time PCR were performed to evaluate the activation of the BMP/SMAD pathway and the expression of hepcidin.

Results

Holo-Tf augmented the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMP6. The E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SMURF1 mediated Holo-Tf-induced SMAD1/5 activation and hepcidin expression; specifically, SMURF1 expression dramatically decreased when the serum iron concentration was increased. Additionally, the expression of SMURF1 substrates, which are important molecules involved in the transduction of BMP/SMAD signaling, was significantly upregulated. Furthermore, in vivo analyses confirmed that SMURF1 specifically regulated the BMP/SMAD pathway during serum iron overload.

Conclusions

SMURF1 can specifically regulate the BMP/SMAD pathway by augmenting the responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMPs during serum iron overload.

Keywords: BMP/SMAD pathway, Hepcidin, Holo-transferrin, Ubiquitin-proteasome degradation, Hemochromatosis

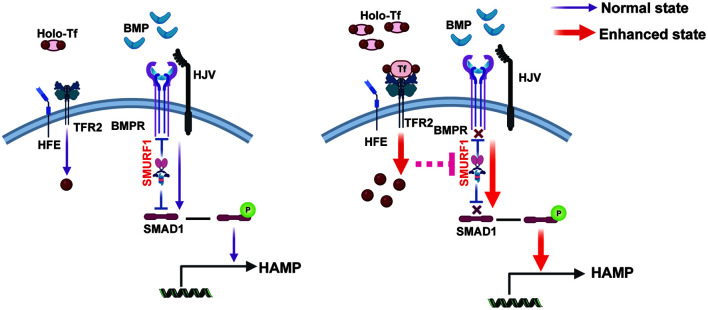

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The liver orchestrates systemic iron balance by producing and secreting hepcidin.1 Hepcidin binds to the nonheme iron exporter ferroportin 1, induces its internalization and degradation, and is vital for maintaining iron homeostasis throughout the body.2 Hepcidin deficiency leads to excess iron deposition in parenchymatous organs and ferroptosis3,4 and is the common pathogenic mechanism for iron overload disorders, such as hereditary hemochromatosis.5

The most commonly studied pathway that influences hepcidin transcription in response to an increase in body iron levels is the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and the SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD) pathway,6 and BMP6 is the predominant BMP ligand responsible for hepcidin regulation in vivo.7 Circulating (serum) and tissue (liver) iron levels have been suggested to regulate hepcidin expression.8 Recent studies have reported that serum and liver iron overload differentially regulates the BMP/SMAD pathway, and the liver iron (deposited iron) content is correlated with the hepatic BMP6 mRNA level and subsequently regulates the BMP/SMAD pathway and hepcidin expression.8,9 However, serum iron (transferrin-bound iron) overload does not induce BMP6 expression but can still regulate the BMP/SMAD pathway and hepcidin expression.10 Thus, the mechanism by which serum iron overload activates SMAD and hepcidin expression remains unknown.

In this study, we investigated the molecular mechanism of the serum iron overload-induced BMP/SMAD pathway and hepcidin expression using transferrin-bound iron (Holo-transferrin, Holo-Tf) and revealed the master regulatory function of SMURF1 in serum iron overload.

Methods

Materials

The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblotting analysis in the present study: anti-phospho-SMAD1/5 (E.239.4) (MA5-15124) from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA); anti-SMAD6 (VPA00295) from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA); anti-SMAD7 (MAB2029) from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA); anti-SMURF1 (WH0057154M1) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); anti-SMURF2 (#12024), anti-SMAD1 (#6944), anti-FTH1 (#4393) and anti-GAPDH (#5174) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA); TFR2 (ab185550) from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and anti-BMPR-1A (12702-1-AP) and anti-BMPR-2 (19087-1-AP) from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA). Holo-Tf (T0665) was purchased from Sigma. Recombinant human BMP6 (120-06) was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Cycloheximide (#2112) and bafilomycin A1 (#54645) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. MG-132 (HY-13259) and LDN193189 (HY-12071) were purchased from MedChemExpress (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA).

Isolation of primary mouse hepatocytes

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from mouse livers as described previously.11 Mouse livers were perfused in situ with EGTA solution, followed by pronase (P147; Sigma) solution and collagenase D (11088882001; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) solution at 37°C. After perfusion, the livers were treated with protease and collagenase D solution and centrifuged at 300 ×g for 3 m at 4°C to isolate hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (10564029; Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, insulin (I9278; Sigma), dexamethasone (D4902; Sigma), and penicillin-streptomycin (15070063; Gibco) in collagen-coated dishes (354236; Corning, New York, NY, USA).

Generation of cells expressing SMURF1

Full-length SMURF1 was synthesized, cloned, and inserted into a GV492 vector containing the CMV promoter.12 At 24 h before infection, the cells were plated in 6-well plates in MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The culture medium was changed 4–6 h after transfection. The cells were harvested after 1 day or 2 days for various assays.

RNA interference

For siRNA transfection, cells were plated the day before transfection.13 The cells were transfected with SMURF1 siRNA (siB1182984600-1-5; Ribobio, Guangzhou, China), BMPR-1A siRNA-1 (stB0004886A-1-5; Ribobio) or BMPR-1A siRNA-2 (stB0004886B-1-5; Ribobio) using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (13778075; Invitrogen). The cells were harvested or further treated 2 days after transfection.

Mouse models

All animals were maintained in a pathogen-free, temperature-controlled environment under a 12-h light/dark cycle at Beijing Friendship Hospital. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee, and all work was performed under the ethical guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. 20-2035). The serum iron overload mouse model was established as previously described,8,13 with some modifications. Briefly, 6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (3–4 per treatment) were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg of human Holo-Tf in 200 µL of saline or saline alone and were analyzed after 2, 4, and 6 h. A mouse model of liver iron overload was established as previously described,14 with some modifications. Briefly, 6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (5 per treatment) were fed a high-iron diet (2% carbonyl iron; TD.08496; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 1 week followed by a low-iron diet (2–6 ppm iron; TD.80396; Envigo) for 2 days before sacrifice. Mice that received a standard rodent diet were used as controls.

RNA-seq

RNA sequencing was performed as previously described.15 Differentially expressed genes between hepatocytes and Holo-Tf-treated hepatocytes were determined using the Student’s t-test. Adjusted p<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Western blotting

Liver tissues or cells were treated with RIPA lysis buffer (#20-188; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).16 The lysis buffer was supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitors (04693159001 and 04906837001; Roche). Equal quantities of protein were separated using 10% or 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After this procedure, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Then, the membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat dried milk in TBST solution for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000) for 1 h at 37°C. Chemiluminescent signals of target proteins were detected using an Ultra High Sensitivity ECL Kit (HY-K1005; MedChemExpress).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR)

Total RNA was isolated, and mRNA levels were measured relative to GAPDH mRNA levels using two-step quantitative real-time PCR, as previously described.17 The sequences of primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primers used for real-time PCR.

| Name | Species | Direction | Sequences, 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hamp | Mouse | Forward | AAGCAGGGCAGACATTGCGAT |

| Reverse | CAGGATGTGGCTCTAGGCTATGT | ||

| Bmp6 | Mouse | Forward | AGAAGCGGGAGATGCAAAAGG |

| Reverse | GACAGGGCGTTGTAGAGATCC | ||

| Id1 | Mouse | Forward | CCTAGCTGTTCGCTGAAGGC |

| Reverse | CTCCGACAGACCAAGTACCAC | ||

| Smurf1 | Mouse | Forward | GCATCAAGATCCGTCTGACA |

| Reverse | CCAGAGCCGTCCACAACAAT | ||

| Gapdh | Mouse | Forward | TGGCCTTCCGTGTTCCTAC |

| Reverse | GAGTTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCA | ||

| HAMP | Human | Forward | TTTTCCCACAACAGACGGGA |

| Reverse | CTCCTTCGCCTCTGGAACAT | ||

| ID1 | Human | Forward | CTGCTCTACGACATGAACGG |

| Reverse | GAAGGTCCCTGATGTAGTCGAT | ||

| GAPDH | Human | Forward | GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT |

| Reverse | GACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG |

Statistical analysis

We used GraphPad Prism software version 8.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA) to conduct all statistical comparisons. The data are presented as the means±standard deviations. Student’s t-test was used to compare the differences between 2 groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. ImageJ software was used to quantify the gray values of the Western blot results for the target proteins. The relative quantification values are indicated under the target bands. The number of times an experiment was repeated is indicated in the figure legends.

Results

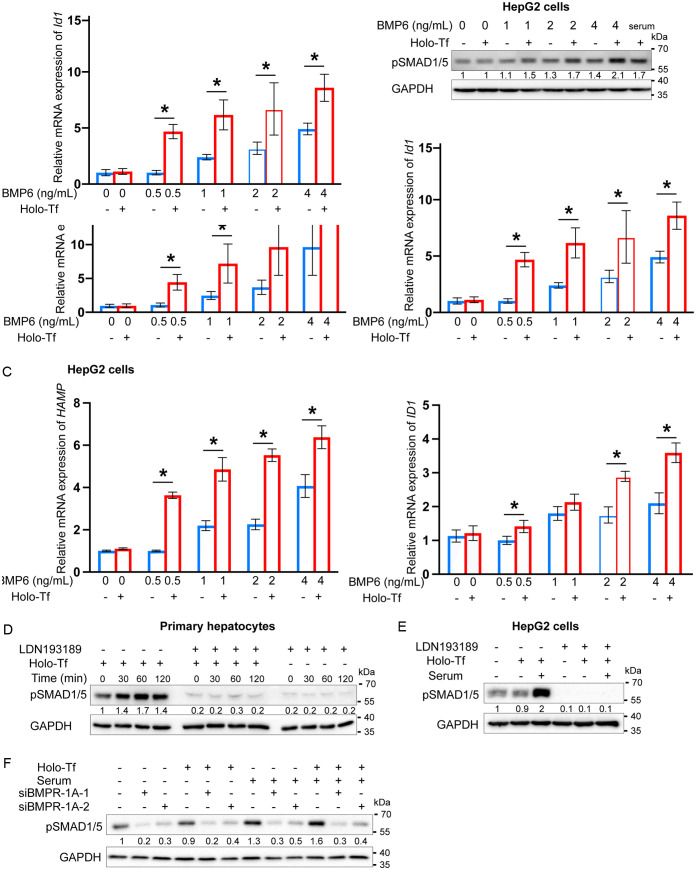

Holo-Tf promotes SMAD1/5 activation and hepcidin expression in hepatocytes in the presence of BMP6

Primary mouse hepatocytes and HepG2 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 with or without Holo-Tf in serum-free medium. The results showed that the pSMAD1/5 level and mRNA expression of HAMP and ID1 increased with increasing BMP6 concentration but were not affected by Holo-Tf in serum-free medium, while the addition of Holo-Tf amplified the effect of BMP6 on the pSMAD1/5 level (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1), as well as HAMP and ID1 mRNA expression (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig. 1. Effects of holo-transferrin (Holo-Tf) on the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMP6.

(A) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in primary mouse hepatocytes (left) and HepG2 cells (right) treated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 with (+) or without (–) 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf in serum-free medium for 2 h. n=2 independent experiments. (B) The mRNA expression of Hamp and Id1 was analyzed in primary mouse hepatocytes treated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 with (+) or without (–) Holo-Tf in serum-free medium for 6 h. *p<0.05; data are presented as the means±standard deviations. (C) The mRNA expression of HAMP and ID1 was analyzed in HepG2 cells treated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 with (+) or without (–) Holo-Tf in serum-free medium for 6 h. *p<0.05; data are presented as the means±standard deviations. (D) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in primary mouse hepatocytes pretreated with (+) or without (–) LDN193189 (10 µM) for 1 h with 5% serum, and 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf with (+) or without (–) LDN193189 was added at the indicated times. n=3 independent experiments. (E) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in HepG2 cells pretreated with (+) or without (–) LDN193189 (10 µM) for 1 h without serum, and 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf or 5% serum with (+) or without (–) LDN193189 was added for 1 h. n=2 independent experiments. (F) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in BMPR-1A-knocked-down (+) and negative control (–) HepG2 cells supplemented with (+) or without (–) 2 mg/mL Holo-Tf in the presence (+) or absence (–) of 5% serum for 1 h. n=2 independent experiments. Unprocessed blots are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. BMP6, bone morphogenetic protein 6; BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-1A; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HAMP, hepcidin; Holo-Tf, holo-transferrin; ID1, DNA-binding protein inhibitor ID-1; pSMAD1/5, phosphorylated SMAD1 and SMAD5 protein.

A previous study reported that Holo-Tf could promote serum-induced hepcidin expression in hepatocytes, and it was hypothesized this induction of hepcidin expression was due to the presence of BMPs in the serum.10 Therefore, we used the BMPR inhibitor LDN193189 to block the BMP pathway and examined the effect of Holo-Tf on SMAD1/5 activation in the presence of serum. The results showed that the BMPR inhibitor LDN193189 nearly completely abolished the effect of Holo-Tf on SMAD1/5 phosphorylation in the presence of serum in both primary mouse hepatocytes and HepG2 cells (Fig. 1D and E and Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, we knocked down BMPR-1A expression using siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 2) and examined SMAD1/5 activation in the presence of Holo-Tf and/or serum. As shown in Figure 1F and Supplementary Figure 1, although SMAD1/5 phosphorylation was upregulated in serum and further augmented in the presence of Holo-Tf, SMAD1/5 activation was dramatically inhibited by BMPR-1A knockdown, suggesting that the function of Holo-Tf in SMAD1/5 phosphorylation and hepcidin expression is dependent on BMPs.

Taken together, these results indicate that Holo-Tf can augment the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMP6; however, the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

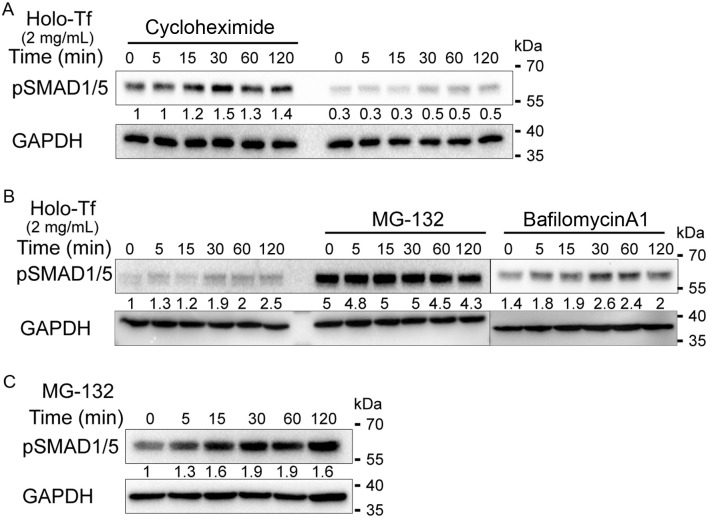

Ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway plays a key role in SMAD1/5 activation by Holo-Tf

To identify the mechanism through which Holo-Tf regulates SMAD1/5 activation, we first performed RNA-seq to determine whether Holo-Tf-induced SMAD1/5 phosphorylation is mediated by transcriptional regulation. Interestingly, no BMP/SMAD pathway genes exhibited significant differences in expression. Only seven genes were differentially expressed (Supplementary Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, the addition of cycloheximide did not affect the activation of SMAD1/5 by Holo-Tf (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1). Consistent with the findings of previous studies,10 our findings confirmed that de novo protein synthesis is not required for Holo-Tf-mediated activation of SMAD1/5.

Fig. 2. The ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway and SMAD1/5 activation by Holo-Tf.

(A) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in HepG2 cells pretreated with or without cycloheximide (100 µg/mL) for 1 h in serum, and supplemented with 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf with or without cycloheximide at the indicated times. n=3 independent experiments. (B) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in HepG2 cells pretreated with or without MG-132 (10 µM) or bafilomycin A1 (10 nM) for 1 h in serum, and supplemented with 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf with or without MG-132 or bafilomycin A1 at the indicated times. n=3 independent experiments. (C) The pSMAD1/5 level was analyzed in HepG2 cells treated with MG-132 (10 µM) in serum at the indicated times. n=3 independent experiments. Unprocessed blots are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Holo-Tf, holo-transferrin; pSMAD1/5, phosphorylated SMAD1 and SMAD5 protein.

Interestingly, although cycloheximide did not affect the SMAD1/5 phosphorylation induced by Holo-Tf, it increased the level of SMAD1/5 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). Because cycloheximide is an inhibitor of eukaryotic protein synthesis, we speculated that protein degradation may be involved. We next investigated the role of lysosomal degradation and the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway, two primary protein degradation pathways, in Holo-Tf-induced SMAD1/5 activation. As shown in Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 1, treatment with the lysosome inhibitor bafilomycin A1 had minimal effects on SMAD1/5 activation, whereas treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 abolished the SMAD1/5 activation induced by Holo-Tf (although, similar to cycloheximide treatment, SMAD1/5 phosphorylation increased after MG-132 treatment). These observations suggest that ubiquitin-proteasome degradation is involved in SMAD1/5 activation by Holo-Tf. In fact, we observed that the pSMAD1/5 expression level increased over time with MG-132 treatment (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 1), which confirmed the important regulatory effect of the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway on SMAD1/5 activation.18

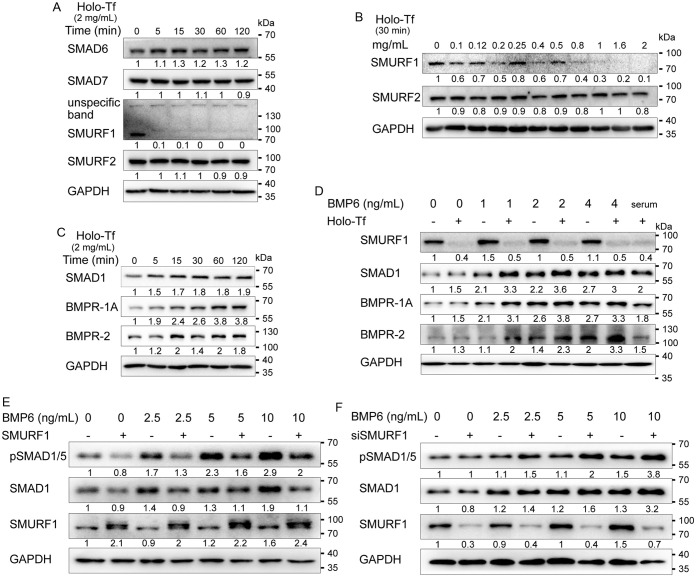

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SMURF1 is implicated in SMAD1/5 activation by Holo-Tf

Regarding the function of ubiquitin-proteasome degradation in Holo-Tf-induced SMAD1/5 phosphorylation, there are two possibilities: first, the inhibitory protein pSMAD1/5 is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system following treatment with Holo-Tf; second, the molecules that mediate ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of activation-related proteins involved in BMP/SMAD signaling are inhibited or degraded after Holo-Tf treatment. Therefore, we first examined the expression of inhibitory SMADs (SMAD6 and SMAD7) after Holo-Tf treatment but found no significant decrease (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 1). Regarding the second possibility, we noted that SMURF1 and SMURF2, members of the Hect family of E3 ubiquitin ligases, are implicated in SMAD and BMPR degradation.19,20 Strikingly, SMURF1 protein expression was nearly undetectable as early as 5 m after Holo-Tf treatment, while SMURF2 expression did not change significantly (Fig. 3A). To further verify that the downregulation of SMURF1 expression was specifically caused by an excess of Holo-Tf, primary mouse hepatocytes were incubated with increasing doses of Holo-Tf. As shown in Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure 1, SMURF1 expression decreased dramatically when the concentration of Holo-Tf reached 1 mg/mL (above the normal physiological concentration of Holo-Tf10,21), while the expression of SMURF2 remained nearly identical.

Fig. 3. Roles of SMURF1 in SMAD1/5 activation by Holo-Tf.

(A) The protein expression levels of SMAD6, SMAD7, SMURF1, and SMURF2 were analyzed in HepG2 cells incubated with 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf in serum at the indicated times. n=3 independent experiments. (B) The protein expression of SMURF1 and SMURF2 was analyzed in primary mouse hepatocytes treated with the indicated concentrations of Holo-Tf for 30 m. n=3 independent experiments. (C) The protein expression levels of SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 were analyzed in HepG2 cells incubated with 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf in serum at the indicated times. n=3 independent experiments. (D) The protein expression of SMURF1, SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 was analyzed in primary mouse hepatocytes treated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 in the presence (+) or absence (–) of 2 mg/mL of Holo-Tf in serum-free medium for 2 h. n=3 independent experiments. (E) The pSMAD1/5 level and the protein expression of SMAD1 and SMURF1 were analyzed in SMURF1-transfected (+) and mock-transfected (–) HepG2 cells treated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 in serum-free medium for 2 h. n=2 independent experiments. (F) The pSMAD1/5 level and the protein expression of SMAD1 and SMURF1 were analyzed in SMURF1-knocked-down (+) and negative control (–) HepG2 cells treated with increasing concentrations of BMP6 in serum-free medium for 2 h. n=2 independent experiments. Unprocessed blots are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. BMP6, bone morphogenetic protein 6; BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-1A; BMPR-2, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Holo-Tf, holo-transferrin; SMAD1: SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1; SMAD6: SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 6; SMAD7: SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7; SMURF1, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 1; SMURF2, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 2.

According to previous reports, SMURF1 may be involved in ubiquitinating SMAD1 and BMPRs for subsequent degradation and plays a role in hepcidin regulation.19,20,22,23 As expected, the expression of SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 was upregulated after Holo-Tf treatment (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway using MG-132 also increased the expression of SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2, confirming the important role of SMURF1 in Holo-Tf-induced SMAD1/5 activation via E3 ubiquitin ligase function (Supplementary Fig. 4). Consistent with the above observations (Fig. 3A, B, and C), in BMP6- and Holo-Tf-treated cells, we did not detect SMURF1 protein expression, and the expression of the SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 proteins was upregulated compared with that in cells treated with BMP6 alone (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 1).

To further confirm the important function of SMURF1 in the BMP6/SMAD1/5 axis, we overexpressed or knocked down SMURF1 expression in HepG2 cells and investigated the effect of SMURF1 on BMP6-induced SMAD1/5 activation. As shown in Figure 3E, F and Supplementary Figure 1, SMURF1 overexpression inhibited the SMAD1/5 activation induced by BMP6, while SMURF1 knockdown augmented the SMAD1/5 activation induced by BMP6. These results were consistent with those of a previous study23 and confirmed the important role of SMURF1 in the BMP/SMAD pathway. Thus, we concluded that Holo-Tf augments the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMP6 through SMURF1.

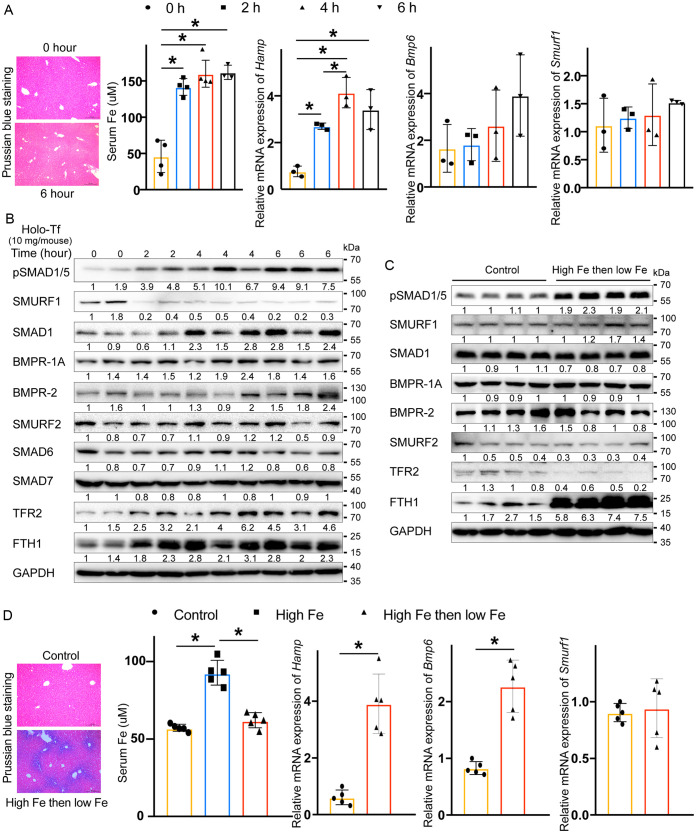

SMURF1 specifically regulates the BMP/SMAD pathway in hepatocytes during serum iron overload but not during liver iron overload

To confirm the master regulatory effect of SMURF1 on serum iron overload in vivo, we established a mouse model of serum iron overload by intraperitoneally injecting 10 mg of Holo-Tf per mouse.8,13 Injection of Holo-Tf increased the serum iron concentration from 30 to 120 µM within 2 h, and the Hamp mRNA concentration increased rapidly to maximal levels within 4 h (Fig. 4A). Moreover, the pSMAD1/5 level exhibited a progressive increase following Holo-Tf injection. Importantly, SMURF1 protein expression decreased immediately after acute iron administration. As indicators of serum iron overload and liver iron overload,8,24 the expression of TFR2 and FTH1 immediately increased following Holo-Tf injection. Accordingly, the expression of the SMAD1 protein began to increase at 4 h after acute iron administration; in addition, the protein expression of BMPR-1A and BMPR-2 slightly increased. However, the expression of SMURF2, SMAD6, and SMAD7 did not change significantly (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 4. Effects of SMURF1 on serum iron overload and the BMP/SMAD pathway in vivo.

(A) Prussian blue staining, the serum Fe concentration, and the mRNA expression of Hamp, Bmp6, and Smurf1 in the serum iron overload mouse model were analyzed at the indicated times (n=3–4 per group). *p<0.05; data are presented as the means±standard deviations. (B) The pSMAD1/5 level and the protein expression of SMURF1, SMAD1, BMPR-1A, BMPR-2, SMURF2, SMAD6, SMAD7, TFR2, and FTH1 were analyzed in a serum iron overload mouse model at the indicated times. (C) The pSMAD1/5 level and the protein expression of SMURF1, SMAD1, BMPR-1A, BMPR-2, SMURF2, TFR2, and FTH1 in the liver iron overload mouse model were analyzed in liver iron overload mouse model. (D) Prussian blue staining, the serum Fe concentration, and Hamp, Bmp6, and Smurf1 mRNA expression in the liver iron overload mouse model were analyzed at the indicated times (n=5 per group). *p<0.05; data are presented as the means±standard deviations. Unprocessed blots are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. BMP6, bone morphogenetic protein 6; BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-1A; BMPR-2, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-2; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HAMP, hepcidin; Holo-Tf, holo-transferrin; pSMAD1/5, phosphorylated SMAD1 and SMAD5 protein; SMAD1: SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1; SMAD6: SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 6; SMAD7, SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7; SMURF1, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 1; SMURF2, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 2; TFR2, transferrin receptor protein 2.

To clarify the specific function of SMURF1 in the regulation of serum iron overload, we also established a mouse model of liver iron overload in which only liver iron, not serum iron, was overloaded,14 represented by increased expression of FTH1 but not of TFR2 (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 1). The Hamp and Bmp6 mRNA expression and pSMAD1/5 levels were significantly greater in the livers of the iron-overloaded mice than in those of the controls (Fig. 4C and D). However, in contrast to those in serum iron-overloaded mice, the protein expression of SMURF1, SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 was not significantly different in liver iron-overloaded mice (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, SMURF1 specifically regulates the BMP/SMAD pathway in hepatocytes during serum iron overload but not during liver iron overload.

Discussion

The mechanism through which serum iron regulates the BMP/SMAD pathway and hepcidin expression in hepatocytes has not been fully elucidated. Although Holo-Tf can activate SMAD1/5 and hepcidin expression in hepatocytes in vivo, the activation of SMAD1/5 and hepcidin expression by Holo-Tf treatment in serum-free medium failed when the cell lines and primary hepatocytes were cultured in vitro.10 The different results obtained from in vivo and in vitro assays indicate that certain factors are lost in in vitro culture.

Here, we showed that Holo-Tf alone cannot activate SMAD1/5 or hepcidin expression in hepatocytes; however, the SMAD1/5 activation and hepcidin expression induced by BMP6 can be augmented by Holo-Tf, suggesting that the effect of Holo-Tf on SMAD1/5 activation and hepcidin expression is dependent on BMP6. In fact, blockade of the transcriptional activity of BMPR by LDN193189 or knockdown of BMPR-1A by siRNA inhibited the activation of SMAD1/5 induced by serum plus Holo-Tf. Consistent with these findings, a previous study reported that liver-specific deletion of BMPR-1A could block the BMP signaling and hepcidin expression induced by iron challenge in cultured hepatocytes and in vivo.25 These results demonstrated the absence of BMPs, which are expressed mainly by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in vivo, in in vitro culture; this absence of BMPs is likely the reason why Holo-Tf cannot activate SMAD1/5 or hepcidin expression in hepatocytes, and the function of Holo-Tf augments the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMP6, thus further activating SMAD1/5 and hepcidin expression in hepatocytes.

Ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system-mediated protein degradation plays important roles in diverse cellular processes.26,27 The BMP/SMAD pathway is tightly regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system.19,28,29 An inhibitor of the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system, MG-132, can increase hepcidin transcription in hepatocytes.30 SMURF1 was originally identified as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for SMAD1 and SMAD5 that causes impaired BMP signal transduction and aberrant embryonic development in Xenopus laevis.19 Subsequent investigations identified other BMP signal transduction-related substrates, including BMP receptors I and II, SMAD4 and SMAD7.31–33 Therefore, SMURF1 ubiquitinates and degrades SMADs at all levels of the BMP signaling cascade. Since the BMP/SMAD pathway is important for hepcidin expression in hepatocytes, it is reasonable that SMURF1 also plays a role in iron metabolism. Zhang et al. reported that growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11) could decrease BMP/SMAD signaling and hepcidin expression by enhancing SMURF1 expression.23 In our study, we revealed a novel role of SMURF1 in iron metabolism. Specifically, Holo-Tf reduced SMURF1 expression, thus augmenting the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMP6 and promoting the activation of SMAD1/5 and hepcidin expression in vivo and in vitro.

Previous studies revealed that Holo-Tf induces hepcidin expression via the BMP/SMAD pathway.8,34 The inhibition of BMP signaling by the addition of noggin or a BMP-neutralizing antibody or by the knockout of the BMP coreceptor hemojuvelin can diminish the response of hepatocytes to Holo-Tf-induced hepcidin expression.21,34 Our study extends the knowledge of the relationship between Holo-Tf and the BMP/SMAD pathway and between Holo-Tf and hepcidin expression in hepatocytes. First, we confirmed that the induction of hepcidin expression by Holo-Tf is dependent on the BMP/SMAD pathway. Second, we found that the mediator of Holo-Tf and the BMP/SMAD pathway in hepcidin expression, specifically, the expression of SMURF1 (the E3 ubiquitin ligase for the BMP signaling cascade) decreased after Holo-Tf treatment. Therefore, the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMPs were promoted, and hepcidin expression was increased. However, the mechanism underlying the decrease in SMURF1 expression after Holo-Tf treatment needs to be further investigated.

Conclusions

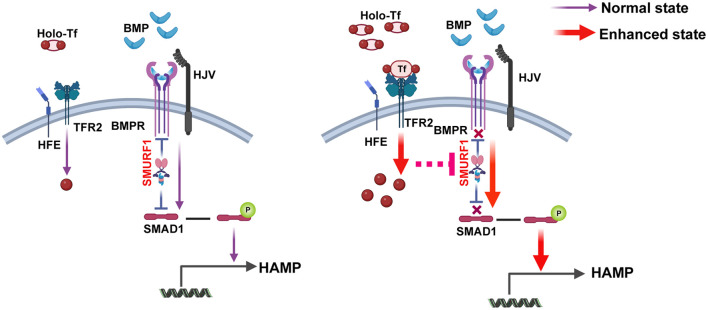

Holo-Tf activates SMAD1/5 and increases hepcidin expression by augmenting the sensitivity and responsiveness of hepatocytes to BMPs by reducing SMURF1 expression (Fig. 5). The inhibition of SMURF1, such as by the inhibitor Smurf1-IN-A01,35 may represent a therapeutic strategy for iron overload-related diseases such as hemochromatosis.

Fig. 5. Schematic diagram illustrating the possible mechanism of SMURF1 in serum iron overload (Created with bioRender.com).

BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; BMPR, bone morphogenetic protein receptor; HAMP, hepcidin; HFE, hereditary hemochromatosis protein; HJV, hemojuvelin; Holo-Tf, holo-transferrin; SMAD1, SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1; SMURF1, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase1; TFR2, transferrin receptor protein 2.

Supporting information

BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1-A; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

(A) Gene expression analysis of HepG2 cells and Holo-Tf-treated HepG2 cells for 1 h by RNA sequencing. The volcano plot of the gene expression values is shown. Red, gene expression upregulated in HepG2 cells treated with Holo-Tf. Green, gene expression downregulated in HepG2 cells treated with Holo-Tf. (B) Differentially expressed genes between HepG2 cells and HepG2 cells treated with Holo-Tf for 1 h.

The protein expression of SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 was analyzed in HepG2 cells treated with MG-132 (10 µM) and serum at indicated time points. BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-1A; BMPR-2, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; SMAD1, SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1.

Abbreviations

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- BMPR

bone morphogenetic protein receptor

- FTH1

ferritin heavy chain

- holo-transferrin

Holo-Tf

- HAMP

hepcidin

- ID1

DNA-binding protein inhibitor ID-1

- pSMAD1/5

phosphorylated SMAD1 and SMAD5 protein

- SMAD

SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog

- SMURF

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase

- TFR2

transferrin receptor protein 2

Ethical statement

All animal work was performed under the ethical guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University (20-2035, Beijing, China).

Data sharing statement

The data generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Wang CY, Babitt JL. Liver iron sensing and body iron homeostasis. Blood. 2019;133(1):18–29. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-06-815894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rishi G, Wallace DF, Subramaniam VN. Hepcidin: regulation of the master iron regulator. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(3):e00192. doi: 10.1042/BSR20150014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Ouyang Q, Chen W, Liu K, Zhang B, Yao J, et al. An iron-dependent form of non-canonical ferroptosis induced by labile iron. Sci China Life Sci. 2023;66(3):516–527. doi: 10.1007/s11427-022-2244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, An P, Xie E, Wu Q, Fang X, Gao H, et al. Characterization of ferroptosis in murine models of hemochromatosis. Hepatology. 2017;66(2):449–465. doi: 10.1002/hep.29117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinyopornpanish K, Tantiworawit A, Leerapun A, Soontornpun A, Thongsawat S. Secondary Iron Overload and the Liver: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2023;11(4):932–941. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2022.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrow NL, Fleming RE. Bone morphogenetic proteins as regulators of iron metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2014;34:77–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andriopoulos B, Jr, Corradini E, Xia Y, Faasse SA, Chen S, Grgurevic L, et al. BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nat Genet. 2009;41(4):482–487. doi: 10.1038/ng.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corradini E, Meynard D, Wu Q, Chen S, Ventura P, Pietrangelo A, et al. Serum and liver iron differently regulate the bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6)-SMAD signaling pathway in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):273–284. doi: 10.1002/hep.24359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kautz L, Meynard D, Monnier A, Darnaud V, Bouvet R, Wang RH, et al. Iron regulates phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 and gene expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 in the mouse liver. Blood. 2008;112(4):1503–1509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramey G, Deschemin JC, Vaulont S. Cross-talk between the mitogen activated protein kinase and bone morphogenetic protein/hemojuvelin pathways is required for the induction of hepcidin by holotransferrin in primary mouse hepatocytes. Haematologica. 2009;94(6):765–772. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.003541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mederacke I, Dapito DH, Affo S, Uchinami H, Schwabe RF. High-yield and high-purity isolation of hepatic stellate cells from normal and fibrotic mouse livers. Nat Protoc. 2015;10(2):305–315. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li YY, Zhou SH, Chen SS, Zhong J, Wen GB. PRMT2 inhibits the formation of foam cell induced by ox-LDL in RAW 264.7 macrophage involving ABCA1 mediated cholesterol efflux. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;524(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Ouyang Q, Chen Z, Chen W, Zhang B, Zhang S, et al. Intracellular labile iron is a key regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Hepatol Int. 2023;17(3):636–647. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos E, Kautz L, Rodriguez R, Hansen M, Gabayan V, Ginzburg Y, et al. Evidence for distinct pathways of hepcidin regulation by acute and chronic iron loading in mice. Hepatology. 2011;53(4):1333–1341. doi: 10.1002/hep.24178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Sun L, Chen W, Wu S, Li Y, Li X, et al. ARHGEF4-mediates the actin cytoskeleton reorganization of hepatic stellate cells in 3-dimensional collagen matrices. Cell Adh Migr. 2019;13(1):169–181. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2019.1594497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun L, Zhou X, Li Y, Chen W, Wu S, Zhang B, et al. KLF5 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition of liver cancer cells in the context of p53 loss through miR-192 targeting of ZEB2. Cell Adh Migr. 2020;14(1):182–194. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2020.1826216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu A, Zhou J, Li Y, Qiao L, Jin C, Chen W, et al. 14-kDa phosphohistidine phosphatase is a potential therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;320(3):G351–G365. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00334.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu XG, Wang Y, Wu Q, Cheng WH, Liu W, Zhao Y, et al. HFE interacts with the BMP type I receptor ALK3 to regulate hepcidin expression. Blood. 2014;124(8):1335–1343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu H, Kavsak P, Abdollah S, Wrana JL, Thomsen GH. A SMAD ubiquitin ligase targets the BMP pathway and affects embryonic pattern formation. Nature. 1999;400(6745):687–693. doi: 10.1038/23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y, Zhang L. A Smurf1 tale: function and regulation of an ubiquitin ligase in multiple cellular networks. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(13):2305–2317. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1170-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L, Valore EV, Nemeth E, Goodnough JB, Gabayan V, Ganz T. Iron transferrin regulates hepcidin synthesis in primary hepatocyte culture through hemojuvelin and BMP2/4. Blood. 2007;110(6):2182–2189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami K, Etlinger JD. Role of SMURF1 ubiquitin ligase in BMP receptor trafficking and signaling. Cell Signal. 2019;54:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang Z, Zhu Z, Zhang H, Peng Y, Liu J, Lu H, et al. GDF11 contributes to hepatic hepcidin (HAMP) inhibition through SMURF1-mediated BMP-SMAD signalling suppression. Br J Haematol. 2020;188(2):321–331. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Chen X, Hong J, Tang A, Liu Y, Xie N, et al. Biochemistry of mammalian ferritins in the regulation of cellular iron homeostasis and oxidative responses. Sci China Life Sci. 2021;64(3):352–362. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1795-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinbicker AU, Bartnikas TB, Lohmeyer LK, Leyton P, Mayeur C, Kao SM, et al. Perturbation of hepcidin expression by BMP type I receptor deletion induces iron overload in mice. Blood. 2011;118(15):4224–4230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hershko A. Roles of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis in cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(6):788–799. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakayama KI, Nakayama K. Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(5):369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrc1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itoh S, ten Dijke P. Negative regulation of TGF-beta receptor/Smad signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izzi L, Attisano L. Regulation of the TGFbeta signalling pathway by ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Oncogene. 2004;23(11):2071–2078. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanamori Y, Murakami M, Matsui T, Funaba M. Hepcidin expression in liver cells: evaluation of mRNA levels and transcriptional regulation. Gene. 2014;546(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murakami G, Watabe T, Takaoka K, Miyazono K, Imamura T. Cooperative inhibition of bone morphogenetic protein signaling by Smurf1 and inhibitory Smads. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(7):2809–2817. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e02-07-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moren A, Imamura T, Miyazono K, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Degradation of the tumor suppressor Smad4 by WW and HECT domain ubiquitin ligases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(23):22115–22123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki C, Murakami G, Fukuchi M, Shimanuki T, Shikauchi Y, Imamura T, et al. Smurf1 regulates the inhibitory activity of Smad7 by targeting Smad7 to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(42):39919–39925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Guo X, Herrera C, Tao Y, Wu Q, Wu A, et al. Bmp6 expression can be regulated independently of liver iron in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y, Wang C, Zhang X, Xing G, Lu K, Gu Y, et al. Selective small molecule compounds increase BMP-2 responsiveness by inhibiting Smurf1-mediated Smad1/5 degradation. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4965. doi: 10.1038/srep04965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1-A; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

(A) Gene expression analysis of HepG2 cells and Holo-Tf-treated HepG2 cells for 1 h by RNA sequencing. The volcano plot of the gene expression values is shown. Red, gene expression upregulated in HepG2 cells treated with Holo-Tf. Green, gene expression downregulated in HepG2 cells treated with Holo-Tf. (B) Differentially expressed genes between HepG2 cells and HepG2 cells treated with Holo-Tf for 1 h.

The protein expression of SMAD1, BMPR-1A, and BMPR-2 was analyzed in HepG2 cells treated with MG-132 (10 µM) and serum at indicated time points. BMPR-1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-1A; BMPR-2, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type-2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; SMAD1, SMA and mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1.