Abstract

The inheritance of gametic methylation patterns is a critical event in the imprinting of genes. In the case of the imprinted RSVIgmyc transgene, the methylation pattern in the unfertilized egg is maintained by the early mouse embryo, whereas the sperm’s methylation pattern is lost in the early embryo. To investigate the cis-acting requirements for this preimplantation stage of genomic imprinting, we examined the fate of different RSVIgmyc methylation patterns, preimposed on RSVIgmyc and introduced into the mouse zygote by pronuclear injection. RSVIgmyc methylation patterns with a low percentage of methylated CpG dinucleotides, generated by using bacterial cytosine methylases with four-base recognition sequences, were lost in the early embryo. In contrast, methylation was maintained when all CpG dinucleotides were methylated with the bacterial SssI (CpG) methylase. This singular maintenance of RSVIgmyc methylation preimposed with SssI methylase appears to be specific to the early, undifferentiated embryo; differentiated NIH 3T3 fibroblasts transfected with methylated versions of RSVIgmyc maintained all methylation patterns, independent of the level of preimposed methylation. The methylation pattern of the RSVIgmyc allele in adult founder transgenic mice that was produced by pronuclear injection of an SssI-methylated construct could not be distinguished from the maternal RSVIgmyc methylation pattern. Thus, a highly methylated allele in adult mice, normally generated by transmission of RSVIgmyc through the female germ line, was also produced in founder transgenic mice by bypassing gametogenesis and introducing a highly methylated RSVIgmyc into the mouse zygote. These results suggest that RSVIgmyc methylation itself is a cis-acting signal for the preimplantation maintenance of the oocyte’s methylation pattern and, therefore, a cis-acting signal for RSVIgmyc imprinting. Furthermore, our inability to identify a sequence element within RSVIgmyc that was absolutely required for its imprinting suggests that the extent of RSVIgmyc methylation, rather than a particular pattern of methylation, is the principal feature of this imprinting signal.

Epigenetic modifications of DNA, in the form of cytosine methylation, are often correlated with the level of gene activity in mammals. The most notable examples of this are the associations between allele-specific DNA methylation and allele-specific silencing of X-linked genes in females and imprinted genes in both sexes (1, 12, 22). For many X-linked genes and probably all imprinted genes, the homologous parental alleles in diploid somatic cells are not equally methylated (1, 23, 25). Typically, the parental allele with the higher level of DNA methylation is silent, whereas the less-methylated allele from the other parent is expressed. For imprinted genes, this difference in methylation develops from different patterns of methylation established in the male and female gametes. For X-linked genes, there are two routes to the development of methylation differences. In the extraembryonic tissues of some mammalian species, a selective, nonrandom inactivation of the paternal X chromosome results in methylation of many of its genes, whereas in the embryo differences in allelic methylation result from random inactivation of either the maternal or the paternal X chromosome (22). Regardless of the developmental path to allele-specific methylation patterns, DNA methylation is generally maintained by a maintenance methylase activity which recognizes hemimethylated DNA and converts it into fully methylated DNA (12, 21). The mammalian DNA cytosine methyltransferase enzyme, encoded by the Dnmt gene, is the only known enzyme in mammals with maintenance methylase activity (2, 3, 39).

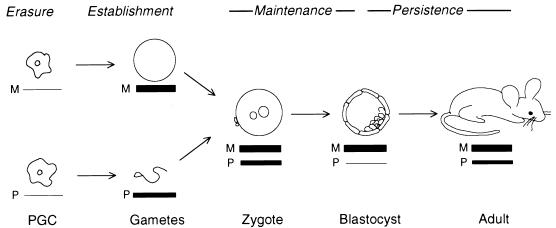

The mechanisms underlying the establishment and maintenance of methylation patterns have been addressed through the study of imprinted genes (7, 31, 33, 35). Among imprinted genes, the RSVIgmyc transgene has two features which make it a particularly attractive system for investigating the origin of DNA methylation patterns (5, 7, 8, 32, 37). The first feature is that the developmental changes in RSVIgmyc methylation, which underlie the generation of parent-specific methylation patterns in mice, have been described (Fig. 1). Changes are initiated in the germ line with the loss of parent-specific methylation patterns in primordial germ cells (i.e., the erasure stage). As the germ cells mature during gametogenesis in females and males, they acquire parent-specific methylation patterns (establishment stage). After fertilization, during the preimplantation stage of embryogenesis, the maternal RSVIgmyc methylation pattern is maintained and the paternal allele loses its methylation pattern (maintenance stage). Although the maternal and paternal RSVIgmyc methylation patterns are subject to very different fates during the maintenance stage of the imprinting process, a difference in methylation between the two parental alleles is preserved. For the remainder of embryogenesis and postnatal development, a difference between the two parental alleles persists despite an increase in RSVIgmyc paternal methylation (persistence stage). The methylation pattern of the maternal allele is unchanged during the maintenance and persistence stages, whereas the methylation pattern of the paternal allele is lost during the preimplantation maintenance stage and then acquires a distinct methylation pattern later during the persistence stage. The cumulative effect of these four developmental stages is an imprinted RSVIgmyc locus in the adult mammal. The other pertinent feature of RSVIgmyc is that it is imprinted at all sites of chromosomal insertion, indicating that the cis-acting signals governing its imprinting reside within the transgene construct itself (7, 8, 32).

FIG. 1.

Four stages in RSVIgmyc imprinting. The relationship of these stages (erasure, establishment, maintenance, and persistence) to developmental stages is depicted. Gametogenesis is shown as the differentiation of primordial germ cells (PGC) into sperm or unfertilized egg. Postfertilization development is shown as transitions from zygote to blastocyst to adult. The thickness of the lines under each gametic or postfertilization stage corresponds to the extent of RSVIgmyc methylation. The thinnest line (in PGC and blastocyst) represents no methylation, and the thickest line (in unfertilized egg, zygote, blastocyst, and adult) represents the heavily methylated maternal allele. M, maternal allele; P, paternal allele. See the text for further description of the methylation changes associated with the imprinting stages.

The identification of four sequential developmental stages in the imprinting of RSVIgmyc suggests that there are four mechanistic steps required for RSVIgmyc imprinting, each corresponding to a developmental stage (erasure, establishment, maintenance, or persistence). In principle, the mechanism underlying each stage utilizes a combination of specific cis- and trans-acting regulatory elements (5, 6). Because the erasure stage of the imprinting process is associated with a generalized loss of genomic methylation, it may not be regulated by cis- and trans-acting signals that are specific to the imprinting process (7, 18). In contrast, the establishment of parent-specific methylation patterns in the parental germ lines undoubtedly makes use of cis-acting sequences and sex-specific controls to ensure the establishment of different imprints in the female and male gametes. Following fertilization, during the maintenance and persistence stages, embryonic cis- and trans-acting factors act to perpetuate a difference between maternal and paternal methylation patterns.

The establishment of different gametic methylation patterns on maternal and paternal alleles is apparently a prerequisite for the generation of imprinted loci (7, 31, 34, 35). However, the establishment stage is not the sole developmental process required for generating imprinted genes. The additional requirements of embryonic regulatory events are evident in studies of both RSVIgmyc and endogenous imprinted genes. For instance, RSVIgmyc imprinting is modulated during the embryonic persistence stage by the background genotype and by nongenetic effects (8, 37). In a C57BL/6J inbred strain background, the RSVIgmyc paternal allele acquires the same methylation pattern during embryogenesis as the maternal allele acquired during gametogenesis and transmitted to the embryo. Consequently, a homozygous RSVIgmyc locus loses its imprinted phenotype during the persistence stage in a C57BL/6J strain background. The RSVIgmyc locus remains imprinted if paternal allele methylation is partially blocked by modulating alleles from other strains, such as the inbred FVB/N strain (8). Modulation of imprinting in the postimplantation stage of development probably also explains the tissue-specific loss of Igf2 gene imprinting in the central nervous system, as well as the “relaxation” of imprinting in certain tumors (9, 10, 19, 20). In addition to the persistence stage, RSVIgmyc imprinting appears to be governed during the maintenance stage. Here, the maternal allele’s distinctive methylation pattern is maintained, despite a concurrent decline in genome-wide methylation and a complete loss of methylation on the paternal RSVIgmyc allele (7). The maintenance stage mechanism is distinct from that of the persistence stage, because the maintenance stage is not regulated by the same genetic modifiers as the persistence stage (8, 37). Moreover, the defining molecular process for the maintenance stage is the maintenance of the oocyte’s methylation pattern rather than the regulation of embryonic de novo methylation that occurs during the persistence stage. These observations suggest that the mechanism underlying the maintenance stage recognizes a cis-acting signal for RSVIgmyc imprinting that is associated with the maternal methylation pattern.

We have undertaken a combined in vivo and cell culture approach to explore the possibility that the highly methylated maternal RSVIgmyc allele is the cis-acting signal for the critical maintenance stage of RSVIgmyc imprinting. We show that the methylation pattern of a highly methylated RSVIgmyc allele, whether inherited from the female parent or obtained from a construct methylated with the SssI (CpG) methylase and injected into a zygotic pronucleus, is maintained in the early embryo. RSVIgmyc constructs methylated to a lesser degree, such as the methylation pattern present in sperm or methylation patterns preimposed on RSVIgmyc by using other bacterial methylases, do not maintain their methylation. These findings contrast with the maintenance of all preimposed methylation patterns following the introduction of RSVIgmyc into differentiated somatic cells. These results are consistent with the highly methylated maternal RSVIgmyc allele being a cis-acting signal for its own inheritance during the preimplantation stage of development. Furthermore, no portion of RSVIgmyc appears to be absolutely required for its imprinting. Taken together, these findings suggest that the highly methylated maternal allele functions as a cis-acting imprinting signal because of its extensive methylation rather than because it possesses a specific pattern of CpG methylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs.

A number of alterations in the RSVIgmyc construct were tested for imprinting and/or maintenance of DNA methylation. In construct 1 (see diagrams, Fig. 4A), all immunoglobulin sequences are deleted from RSVIgmyc, as well as the 5′-most sequences of the c-myc gene, up to a BglII site 120 bp into the first intron. Construct 2 is identical to construct 1 except for the additional deletion of all the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) sequences. Construct 3 is deleted of all immunoglobulin sequences and contains additional 5′ c-myc genomic sequences, contiguous with RSVIgmyc’s c-myc sequences. All of the c-myc sequences for this construct were from a 21-kb EcoRI genomic fragment of c-myc obtained from the BALB/c inbred strain of mice, the same inbred strain as the RSVIgmyc IgA–c-myc translocation (15). From this 21-kb fragment, a 17-kb StuI-EcoRI fragment was used for the c-myc portion of the altered transgene; this 17-kb fragment contains all of the c-myc sequences of RSVIgmyc plus additional 5′ sequences. The StuI site is approximately 3.2 kb 5′ of the beginning of the first intron of c-myc (30). Additionally, the c-myc gene was inactivated by the insertion of a 26-mer (CCCTAGTCTAGAATTCTAGACTAGGG) sequence containing an in-frame stop codon and a diagnostic EcoRI site at the unique EcoRV site in exon 2. This precluded misexpression of a full-length c-myc protein in the altered RSVIgmyc construct. This 26-mer insertion in the RSVIgmyc construct did not affect its imprinting (6a).

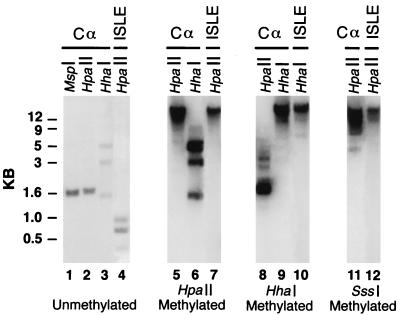

FIG. 4.

Imprinting characteristics of mutated RSVIgmyc constructs. (A) Constructs were made as described in Materials and Methods and are depicted as their KpnI-linearized versions. Shown at the top is the original RSVIgmyc construct (32). Construct 1 is a deletion of all IgA sequences. Construct 2 is a deletion of all IgA and RSV sequences. Construct 3 is a deletion of IgA sequences and contains additional contiguous 5′ sequences of the genomic mouse c-myc gene (labeled “5′ myc”). (B) Southern blots of HpaII digests of paternal and maternal transgene alleles. Shown at the top are the hybridization probes and the parental origin of the transgene (P, paternal; M, maternal). Lanes 1 and 2 are paternal and maternal alleles, respectively, of the RSVIgmyc transgenic line TG.AAJ hybridized with the Cα probe. Lanes 3 and 4 are paternal and maternal alleles of TG.AAJ hybridized with the exon 3 probe. Lanes 5 and 6 are paternal and maternal alleles, respectively, of a transgenic line created with construct 1 and hybridized with the exon 3 probe. Lanes 7 and 8 are paternal and maternal alleles, respectively, of a transgenic line created with construct 2 and hybridized with the exon 3 probe. Lanes 9 and 10 are paternal and maternal alleles, respectively, of a transgenic line created with construct 3 and hybridized with the exon 3 probe. (C) Ribonuclease protection experiment to analyze expression of construct 3 in heart cells. P, paternal transgene allele; M, maternal transgene allele. Ribonuclease protection was performed with 15 μg of total RNA and a riboprobe containing a portion of exon 1 and 2 of c-myc. The protected band labeled “endogenous c-myc” is 358 bp. The band labeled “transgene c-myc” is comprised of two similarly sized fragments of 153 and 158 bp from exon 2 of the transgene c-myc.

Methylation studies.

RSVIgmyc and certain variants were methylated in vitro with the bacterial methylases HpaII, HhaI, FnuDII, and SssI according to the manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The extent of the methylation reaction was tested with the corresponding methylation restriction enzyme, except in the case of methylation with SssI, which was tested with the HpaII and HhaI restriction endonucleases. Only constructs completely methylated at the appropriate restriction sites were used in transfection and transgenic mouse experiments. The hybridization probes used for Southern blot analysis were a 1.7-kb fragment of the mouse IgA constant region (Cα probe); a 1.3-kb BglII-XbaI fragment from the first intron of c-myc, representing the CpG island of RSVIgmyc (ISLE probe); or a PvuII-XhoI fragment of c-myc exon 3 (exon 3 probe). The location of these probes is indicated in Fig. 2A.

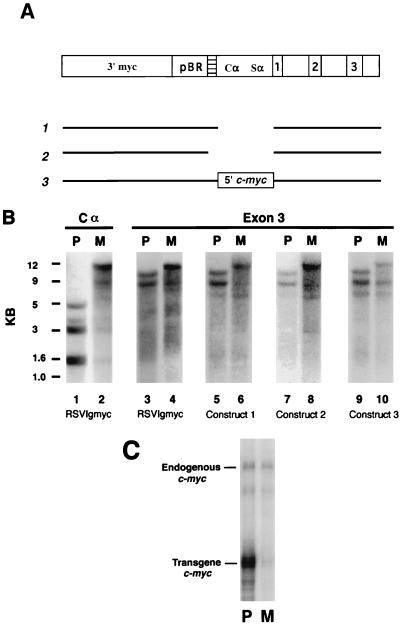

FIG. 2.

Examination of the maintenance of RSVIgmyc methylation in founder transgenic mice. (A) Schematic of the RSVIgmyc plasmid linearized with KpnI. Details of its composition can be found in Chaillet et al. (8). The 1, 2, and 3 designate the exons of the transgene’s c-myc gene. The 3′ myc indicates the noncoding genomic sequences, which are contiguous in the circularized plasmid with the genomic region of c-myc containing exons 1 to 3. The horizontally hatched area is a portion of the RSV long terminal repeat. pBR, pBR322 sequences; Cα, coding sequences of IgA; Sα, IgA switch recombination sequences. Vertical marks at the top of the schematic are the positions of the MspI sites. The three hybridization fragments used in the analysis of methylation are shown as filled rectangles above the schematic. Restriction sites: X, XbaI; Bg, BglII; P, PvuII; Xh, XhoI. The positions of the HhaI and FnuDII restriction endonuclease sites are shown on the bar below the RSVIgmyc schematic. Density plots of the percentage of CG and GC dinucleotides along the RSVIgmyc sequence are also shown. (B) Four different versions of the RSVIgmyc construct were evaluated for their methylation in adult founder transgenic mice produced by pronuclear injection of the transgene construct: unmethylated RSVIgmyc, HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc, HpaII-HhaI-FnuDII-methylated RSVIgmyc, and SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc. Lane 1 shows the RSVIgmyc methylation pattern in sperm. Lanes 2 and 3 contain inherited paternal and maternal alleles, respectively, of the RSVIgmyc line TG.AAJ, which are shown for comparison to the digests from the founder transgenic mice. Lane 4 contains the construct from a founder mouse injected with unmethylated construct RSVIgmyc. Lane 5 contains the construct from a founder mouse injected with HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc. Lane 6 contains the construct from a founder mouse injected with HpaII-HhaI-FnuDII-methylated RSVIgmyc. Lane 7 contains the construct from a founder mouse injected with SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc. Lanes 8 and 9 contain paternally and maternally inherited TG.AAJ alleles, respectively, and lane 10 is from an SssI-methylated founder RSVIgmyc allele. Hybridization probes are shown at the top of the figure. Lane designations and the preimposed methylation are shown at the bottom of the figure. All lanes are HpaII digests. Lanes 1 to 7 were hybridized with Cα, and lanes 8 to 10 were hybridized with the c-myc CpG island probe.

Methylation of transfected or injected constructs was analyzed by Southern blotting with methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases as described in the text and in the figure legends. DNA was isolated from the tails of adult mice or from the transfected cells by proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) digestion, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction. After ethanol precipitation and resuspension of the DNA in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mM EDTA), DNA samples were digested at the appropriate temperature with the restriction endonuclease (10 U/μg of DNA), electrophoresed on 1% agarose, and transferred to GeneScreen nylon filters (NEN Research Products, Boston, Mass.) by the method of Southern (27). The filters were hybridized with one of four hybridization probes at 42°C in 40% formamide and washed in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 65°C.

Cell lines.

NIH 3T3 cells were used for transfection of RSVIgmyc constructs. NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with Asp718-linearized DNA and Asp718-linearized pPNT plasmid (36) containing a neomycin resistance gene under the control of the mouse Pgk-1 promoter at a ratio of 15:1 (15 μg of total DNA) by using 24 μl of LipofectAce (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) per 100-mm-diameter plate. The cells were exposed to the DNA-LipofectAce mixture for 6 h in serum-free media. G418 (400 μg/ml) was added to the cells 24 h after the initiation of the transfection. Clones were isolated, expanded, and collected for RNA and DNA to analyze the methylation and expression properties of the transfected construct.

Mice.

All transgenic lines were made and analyzed for imprinting characteristics in FVB/N mice as previously described (8). Transgene constructs were linearized at a unique Asp718 site prior to pronuclear injection. After transgenic lines were established, two types of offspring were obtained: those with maternally transmitted hemizygous transgenes and those with paternally transmitted hemizygous transgenes. All of the analyzed transgenic lines contained ca. 5 to 15 copies of the transgene construct.

RNA analysis.

Heart RNA was isolated as previously described (8). Heart RNA was analyzed for transgene expression by a ribonuclease protection assay (16). Transgenic mice with construct 3 (see Fig. 4A) were analyzed for transgene expression with a 358-bp XhoI-PvuII fragment of the mouse c-myc cDNA that includes the 3′ portion of exon 1 and the 5′ portion of exon 2. Because construct 3 has a 26-mer inserted at the unique EcoRV site in exon 2 of c-myc, protected fragments of 205 and 153 bp are expected from completely processed full-length transgenic c-myc mRNA. Exon 2 protection alone, which has been seen as the predominant protected fragment in RSVIgmyc transgenics (8, 32), would be expected to yield approximately equal-sized fragments of 158 and 153 bp because of the presence of the 26-mer in the transgene mRNA but not in the riboprobe.

RESULTS

Selective maintenance of RSVIgmyc methylation in the early mouse embryo.

We examined the maintenance of RSVIgmyc methylation during the preimplantation stage of embryogenesis by determining the outcome of pronuclear injections of unmethylated and methylated RSVIgmyc. Details of the structure of RSVIgmyc (including CG and GC dinucleotide content, and the location of methylation-sensitive restriction sites) and the origin of DNA hybridization fragments used in Southern blot analysis of RSVIgmyc methylation are shown in Fig. 2A. For six RSVIgmyc founder mice generated with unmethylated RSVIgmyc DNA, the integrated transgene has the same methylation pattern as the paternal alleles in all previously analyzed RSVIgmyc transgenic lines (references 8 and 32 and data not shown). This is evident by comparing the size and relative intensities of bands on Southern blots of HpaII digests of DNA (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 4). Despite the complexity of the Southern blot patterns, which contain a number of partially methylated RSVIgmyc fragments, the methylation patterns of a founder transgenic mouse and a carrier transgenic mouse that inherited a paternal RSVIgmyc allele appeared to be indistinguishable. These results are consistent with an unmethylated founder RSVIgmyc allele and an unmethylated paternally inherited RSVIgmyc allele at the blastocyst stage, both of which acquired identical methylation patterns between days 3.5 and 7.5 of embryogenesis (7, 8).

The methylation patterns of RSVIgmyc in three adult founders generated by pronuclear injections of HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc are indistinguishable from the pattern derived from the injection of unmethylated RSVIgmyc (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 and 5). Because this adult pattern can emerge only if many HpaII sites in RSVIgmyc are digested with HpaII, the preimposed HpaII methylation has not been maintained in its entirety. The likely explanation for this is that the HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc lost all of its in vitro methylation during the preimplantation stage of embryogenesis and then acquired the paternal methylation pattern de novo between days 3.5 and 6.5 of embryogenesis (7). Collectively, the results of pronuclear injections of unmethylated and HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc constructs strongly suggest that preimposed RSVIgmyc methylation patterns were lost entirely in the preimplantation mouse embryo and that the undermethylated paternal pattern was placed during a subsequent period of de novo methylation. To test this possibility further, injections of other preimposed RSVIgmyc methylation patterns were performed.

Another preimposed RSVIgmyc methylation pattern was obtained with a combination of three sequence-specific bacterial methylases, HpaII, HhaI, and FnuDII (recognition sequences CCGG, GCGC, and CGCG, respectively). In addition to imposing a unique pattern of DNA methylation on RSVIgmyc, this combined treatment significantly increased the number of CpG dinucleotides methylated compared to HpaII methylation alone. Three founder transgenic mice produced from an injection of this construct exhibited the same undermethylated pattern seen following injection of unmethylated and HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc constructs (Fig. 2B, lanes 4, 5, and 6, and data not shown). Moreover, these methylation patterns were indistinguishable from the methylation pattern of an RSVIgmyc allele in adult mice that inherited RSVIgmyc from a male parent (Fig. 2B, lane 2). Therefore, even when a significant portion of RSVIgmyc CpG dinucleotides were methylated (19%, based on 434 CG dinucleotides, 27 MspI sites, 35 HhaI sites, and 21 FnuDII sites in RSVIgmyc), the preimposed methylation appeared to be lost in the preimplantation embryo and the undermethylated paternal pattern acquired thereafter.

The last preimposed RSVIgmyc methylation pattern examined is an SssI-methylated one, in which all CpG dinucleotides are methylated with the SssI methylase. In contrast to the outcome of injections of RSVIgmyc with other methylation patterns, this preimposed methylation was maintained following injection of RSVIgmyc into one of the pronuclei of unfertilized eggs. This was evident in the resistance of founder RSVIgmyc sequences to HpaII digestion (Fig. 2B, lane 7). As well, the integrated RSVIgmyc was resistant to HhaI digestion (data not shown). This highly methylated phenotype of RSVIgmyc was confined to the non-CpG portion of RSVIgmyc. When a Southern blot of an HpaII digest of an SssI-methylated founder transgenic mouse was hybridized with a probe from the c-myc CpG island, small fragments were seen (Fig. 2B, lane 10). The presence of these small fragments indicates that the CpG island of RSVIgmyc was largely, if not completely, unmethylated. The pattern of DNA methylation throughout the founder’s RSVIgmyc DNA appeared to be same as the methylation of a maternally inherited RSVIgmyc allele. That is, maternally inherited RSVIgmyc was also unmethylated at HpaII sites within RSVIgmyc’s CpG island but methylated at HpaII sites outside of the c-myc CpG island (compare lanes 3 and 9 in Fig. 2B). Similar methylation patterns were seen in an additional five transgenic founders generated with SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc (data not shown). This similarity in methylation between a founder allele generated with SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc and a maternally inherited RSVIgmyc allele seems to extend to CpG dinucleotides outside of HpaII sites. For example, all cytosines in CpG dinucleotides within the RSV portion of RSVIgmyc (which does not contain HpaII sites) were methylated on both the maternal allele and the SssI-methylated founder allele when examined by a bisulfite genomic sequencing protocol (data not shown).

Maintenance of RSVIgmyc methylation patterns in differentiated cells.

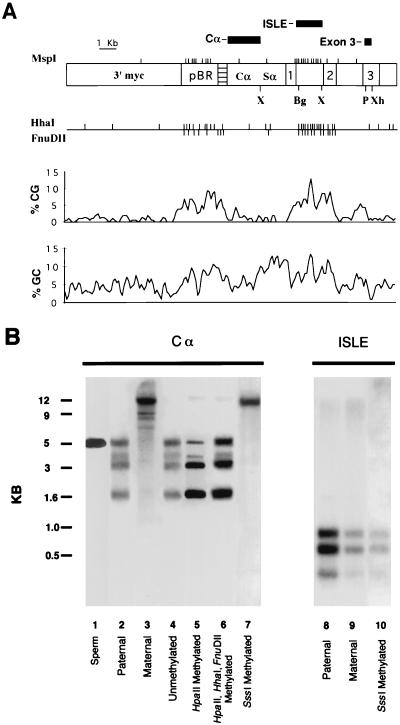

The maintenance of preimposed methylation produced with the SssI methylase and the loss of other, less-methylated, preimposed patterns during preimplantation development may be a property of the early mouse embryo. Alternatively, selective maintenance of preimposed methylation may be a property of RSVIgmyc and may be found elsewhere. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we examined the outcome of experiments in which RSVIgmyc, unmethylated or modified with different preimposed methylation patterns, was introduced into differentiated somatic cells. Unmethylated RSVIgmyc was cotransfected along with a bacterial neomycin resistance gene into NIH 3T3 cells, and clones of stably integrated RSVIgmyc were selected with the aminoglycoside G418. DNA samples from individual clones were digested with the methylation-insensitive enzyme MspI (recognition sequence CCGG) and the methylation-sensitive enzymes HpaII (an isoschizomer of MspI) and HhaI (recognition sequence GCGC). Southern blots of MspI and HpaII digests of DNA, hybridized with a probe from the immunoglobulin sequences of RSVIgmyc (Cα probe in Fig. 2A), were identical (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2). This indicates the absence of CpG methylation within HpaII sites. The small bands on the Southern blot of DNA digested with HhaI are consistent with the near absence of methylation at HhaI sites in RSVIgmyc (lane 3). (The 3- and 5-kb hybridization bands in lane 3 probably represent a small amount of de novo methylation at the HhaI sites in Cα and Sα or resistance to digestion of these sites, even when unmethylated.) Furthermore, when the HpaII-digested DNA was hybridized with a c-myc CpG island fragment (ISLE probe in Fig. 2A), the small fragments on the Southern blot indicate that the CpG island at the 5′ end of the transgene’s c-myc gene was also unmethylated (lane 4). All in all, these results indicate that unmethylated RSVIgmyc sequences remain largely unmethylated following integration and DNA replication. Notably, RSVIgmyc does not acquire the undermethylated, paternal allele-like methylation pattern seen in adult founder transgenic mice following pronuclear injection of unmethylated RSVIgmyc (see above). These findings are consistent with observations that de novo methylation is generally restricted to the early mammalian embryo and to undifferentiated stem cell lines (7, 13, 14, 18, 29).

FIG. 3.

Examination of the maintenance of RSVIgmyc methylation in NIH 3T3 cells. Four different versions of the RSVIgmyc construct were analyzed for methylation after their genomic integration into NIH 3T3 cells. Southern blot analysis of DNA samples isolated from individual stably transfected NIH 3T3 clones is shown. Lanes: 1 to 4, analysis of unmethylated RSVIgmyc in NIH 3T3 cells; 5 to 7, analysis of HpaII-methylated RSVIgmyc; 8 to 10, analysis of HhaI-methylated RSVIgmyc; 11 to 12, analysis of SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc. Probes used in the analysis and the restriction endonuclease digest for each lane are shown at the top of the figure. The preimposed methylation of RSVIgmyc is shown at the bottom of the figure. Lane 1 is an MspI digest. Lanes 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, and 12 are HpaII digests. Lanes 3, 6, 9, and 10 are HhaI digests. Lanes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11 were hybridized with the Cα probe, and lanes 4, 7, 10, and 12 were hybridized with the ISLE probe.

We next examined the maintenance of DNA methylation in NIH 3T3 cells transfected with methylated RSVIgmyc constructs. Transfection of RSVIgmyc DNA, which was methylated at all CpG dinucleotides within HpaII sites, produced an integrated RSVIgmyc construct which remained methylated at HpaII sites, including sites within RSVIgmyc’s CpG island. Methylation of the HpaII sites was manifested as large hybridization bands on Southern blots of HpaII-digested DNA (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 7). CpG dinucleotides not within HpaII sites remained unmethylated. For example, HhaI sites were digested with HhaI (lane 6). Comparable results were obtained in experiments in which RSVIgmyc was methylated with the bacterial HhaI methylase or with the bacterial SssI methylase prior to transfection. An HhaI-methylated construct was transfected, and resulting RSVIgmyc sequences were resistant to cleavage by HhaI but were sensitive to HpaII (lanes 8 to 10). (Less intensely hybridizing, high-molecular-weight bands in lane 8 are consistent with a small but detectable amount of de novo methylation at the HpaII sites in RSVIgmyc.) In the case of the transfected SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc (all CpG dinucleotides methylated), the integrated construct was resistant to cleavage by HpaII, both in non-CpG island and CpG island sequences, as indicated by the large size of the hybridization bands (Fig. 3, lanes 11 and 12). Therefore, methylation of RSVIgmyc introduced into differentiated somatic cells is faithfully maintained, much as the methylation patterns of other DNA fragments are clonally inherited following their introduction into mouse cells (24, 28). Taken together, these results indicate that the selective maintenance of SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc is probably restricted to the preimplantation stage of development.

Embryonic maintenance of methylation and the cis-acting requirements for RSVIgmyc imprinting.

The apparent equivalence of a maternal RSVIgmyc allele and a founder allele created with SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc suggests that the oocyte’s methylation is a cis-acting signal for the maintenance stage of RSVIgmyc imprinting. The maternal allele could be a cis-acting imprinting signal in the preimplantation embryo because of the extent of RSVIgmyc methylation or because a particular cytosine (or group of cytosines) in the RSVIgmyc sequence is methylated. These two possibilities can be distinguished. If the extent of RSVIgmyc methylation is the preimplantation maintenance signal, there may not be a particular primary sequence element in RSVIgmyc that is required for its imprinting. However, the other possible signal is a specific pattern of CpG methylation, which must be restricted to particular primary DNA sequences. From a collection of initial experiments on various mutations in RSVIgmyc, we ruled out the importance for imprinting of RSVIgmyc sequences outside of the IgA region (8). Here, to address the possibility that the preimplantation imprinting signal resides within the IgA region, we examined additional RSVIgmyc mutations that included deletions of IgA sequences.

Imprinting of RSVIgmyc was preserved after deletion of IgA sequences from RSVIgmyc (Fig. 4A, constructs 1 to 3). For example, in construct 1, all immunoglobulin sequences were deleted, yet the paternal allele remained significantly less methylated than the maternal allele. This was clearly shown when HpaII digests of hemizygous paternal and maternal alleles of a transgenic line created with construct 1 were hybridized with the exon 3 probe (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6). One other additional transgenic line made with construct 1 showed identical parent-specific methylation patterns (data not shown). Moreover, with the removal of both IgA and RSV sequences (Fig. 4A, construct 2) the methylation patterns of paternal and maternal transgene alleles also remain different (Fig. 4B, lanes 7 and 8). Another transgenic line produced with construct 2 demonstrated the same parent-specific methylation patterns. Because Southern blots of RSVIgmyc, construct 1, and construct 2 carrier transgenic sequences were all hybridized with the exon 3 probe (lanes 3 to 8), the effect of the deletions on transgene methylation can be evaluated. In contrast to the Cα probe, which flanks sequences containing many MspI sites (i.e., pBR322 and the CpG island region of c-myc), exon 3 and neighboring sequences of the transgene constructs contain no MspI sites (Fig. 2A). Therefore, high-molecular-weight bands are seen on Southern blots hybridized with the exon 3 probe. Nonetheless, it is clear that the paternal-allele methylation patterns appear to be the same in all three constructs, whereas the maternal-allele patterns are clearly more methylated for all three constructs (Fig. 4B). These observations indicate that constructs 1 and 2 are imprinted despite the deletion of all immunoglobulin sequences. Therefore, constructs 1 and 2 have most likely become imprinted in the same development way as RSVIgmyc: maternal alleles acquire an extensive, heritable methylation pattern during late oogenesis, and paternal alleles acquire all of their adult methylation pattern during embryogenesis, the extent of which is determined by strain-specific effects (7, 8).

Because the IgA region contains regulatory sequences for RSVIgmyc expression (8), we were unable to determine a correlation between differences in parental allele methylation patterns and differences in allelic expression for constructs in which IgA sequences are deleted (constructs 1 and 2). To address this issue, we replaced the IgA region with a regulatory region from the mouse c-myc gene. This was accomplished by constructing a transgene in which all IgA sequences were removed and genomic c-myc sequences 5′ of the IgA–c-myc breakpoint in RSVIgmyc were added (construct 3, Fig. 4A). Two transgenic lines produced with this construct were genomically imprinted, in terms of both methylation and expression differences between the parental alleles (Fig. 4B, lanes 9 and 10, and Fig. 4C). Again, the paternal and maternal methylation patterns of transgene carriers of construct 3 were similar to those of RSVIgmyc, constructs 1 and 2. These findings are consistent with a developmental origin of construct 3 imprinting that is the same as that of RSVIgmyc (7, 8).

From the results of the methylation and expression analysis of constructs 1 to 3, we conclude that the IgA sequences are not required for transgene imprinting. These data, along with the analysis of previously described RSVIgmyc mutations (8), indicate that there is no particular RSVIgmyc sequence element which is absolutely required for its imprinting. These findings support a model that equates the extent of maternal RSVIgmyc methylation to the cis-acting signal for the maintenance stage of imprinting.

DISCUSSION

The inheritance of gametic methylation patterns.

An imprinted RSVIgmyc transgene is elaborated during gametogenesis and embryogenesis in a series of four distinct stages (Fig. 1). Two of these stages occur in the germ line and function to first remove methylation (the erasure stage) and then place parent-specific methylation patterns on RSVIgmyc (the establishment stage). The remaining two stages (maintenance and persistence) ensure the inheritance and perpetuation of allelic differences in methylation during embryonic development. The earlier embryonic stage, the maintenance stage, involves the inheritance of the oocyte’s methylation pattern by the preimplantation embryo. This stage is critical to the generation of an imprinted RSVIgmyc transgene, as its failure would result in the loss of RSVIgmyc methylation in the preimplantation embryo and consequently result in identical methylation patterns on both the maternal and paternal RSVIgmyc alleles. Failure of the persistence stage can also result in the loss of RSVIgmyc imprinting at a later stage in embryonic development through a genetic process that results in the extensive methylation of the paternal RSVIgmyc allele (8). The analysis described here strongly suggests that the molecular mechanism underlying the maintenance stage selectively recognizes the methylated maternal RSVIgmyc allele (and not the less-methylated paternal allele) and ensures its perpetuation during early embryonic development.

In principle, the maintenance of the maternal RSVIgmyc methylation pattern during preimplantation development is determined by a mechanism which recognizes the maternal allele and maintains its methylation following DNA replication. There are two general recognition mechanisms to consider. One recognizes a specific pattern of methylated CpG dinucleotides in RSVIgmyc; the alternative mechanism recognizes the extent of CpG methylation on the RSVIgmyc allele. With respect to the former mechanism, a maintainable pattern of CpG methylation on RSVIgmyc would be established with the SssI methylase but not necessarily with the HpaII, HhaI, or FnuDII methylases applied individually or in combination. Also, the paternal allele in sperm would not have a heritable sequence of methylation. With respect to the latter mechanism, heritable RSVIgmyc methylation would be established on pretreatment of RSVIgmyc with the SssI methylase prior to pronuclear injection or by passage through the maternal germ line. At present, it is difficult to distinguish between these two recognition mechanisms because of the limited number of methylation patterns which can be produced by using bacterial methylases. However, by analyzing many constructs in which different regions of RSVIgmyc have been deleted, we have been unable to define here a single RSVIgmyc sequence element that is absolutely required for its imprinting (see also reference 8). Although large deletions (>14 kb) of the ∼18-kb RSVIgmyc resulted in the loss of transgene imprinting, none of the deleted sequences were absolutely required for the imprinting of other RSVIgmyc deletion constructs (8; the present study). The reasons for the loss of imprinting of constructs with large deletions are unknown. One possibility is that the small size of some RSVIgmyc derivatives causes them to be methylated in the same manner as the sequences of their integration sites. Because transgenes integrate randomly into chromosomes and the majority of the genome is nonimprinted (26), the small transgenes would not be imprinted. Alternatively, transgene imprinting may require a certain fraction of the composite RSVIgmyc sequences to correctly proceed through all four of the imprinting stages. Therefore, a significant reduction in the size of the transgene may result in the loss of one or more of the stages. For instance, small transgenes may result in the acquisition of equal and heritable methylation patterns in both male and female gametes (establishment stage) and/or result in extensive methylation of the paternal transgene allele during embryogenesis (persistence stage). Such effects on specific imprinting stages would result in a nonimprinted transgene locus.

The findings presented here suggest that identical patterns of methylated cytosines are not likely to be present on all imprinted RSVIgmyc derivatives. For this to occur, identical patterns would have to be present on very dissimilar sequences from different sources (e.g., bacterial, viral, and mouse genomes). Therefore, the level of transgene methylation is more likely to be the cis-acting signal for the inheritance of the maternal RSVIgmyc methylation pattern. In this respect, it is interesting that the inherited methylation of the imprinted H19 gene is found within a 2-kb genomic region in which most or all of the population of CpG dinucleotides are methylated (33, 34). In a way similar to the inheritance of the oocyte’s RSVIgmyc methylation, this region of H19 is heavily methylated in the male gamete and remains so following fertilization (34).

If the cis-acting signal for RSVIgmyc imprinting during the maintenance stage is indeed the methylated maternal allele, then what are the trans-acting elements associated with this maintenance stage? In principle, trans-acting regulators can be identified by their association with the maternal RSVIgmyc allele during preimplantation development. At present, no trans-acting imprinting elements, including ones regulating the maintenance stage, have been identified. Nevertheless, because this stage involves the maintenance of a methylation pattern, we can speculate on the role of a DNA methyltransferase activity in the maintenance process. The DNA cytosine methyltransferase gene Dnmt is expressed in all preimplantation stages, including in the zygote, morula, and blastocyst (4). The gene’s product seems to function in vivo primarily as a maintenance methylase, although it may have an additional de novo methylase activity (2, 3, 39). In a feasible scenario for the inheritance of germ line methylation, the Dnmt methyltransferase is associated with the maintenance stage and recognizes the cis-acting imprinting feature of the maternal RSVIgmyc allele to maintain its methylation. Because of the selective maintenance of only heavily methylated RSVIgmyc in the preimplantation embryo (obtained by injection of SssI-methylated RSVIgmyc or inherited from the maternal gamete), the methyltransferase would not recognize the less-methylated paternal RSVIgmyc allele. Consequently, the RSVIgmyc methylation found in sperm would be absent in the blastocyst (7, 8).

The Dnmt maintenance methylase activity in differentiated somatic cells apparently possesses an indiscriminate maintenance activity. That is, the enzyme maintains all methylation patterns. This activity is evident in the transfected NIH 3T3 cell lines described here. In contrast, a maintenance methylation function of Dnmt methyltransferase during preimplantation development would be different, discriminating between inherited maternal and paternal methylation patterns and maintaining only the methylation pattern on the maternal allele. In this regard, it is interesting that the Dnmt gene product present in the unfertilized egg and preimplantation embryo during the critical maintenance stage has molecular attributes that are different from the enzyme found in somatic cells of postimplantation embryos and adults (4). In particular, this preimplantation form has a higher electrophoretic mobility than the form found in somatic cells of adults and postimplantation embryos. The origin of this preimplantation form of the Dnmt gene product is a transcript that is produced in oocytes by using an alternative first exon of Dnmt (17). Transcripts with this exon have a different translational start site than Dnmt mRNA produced in somatic cells. As a consequence, the unfertilized egg and early embryo contain a polypeptide of 1,503 amino acids, which represents a 118-amino-acid N-terminal truncation of the 1,621-amino-acid somatic form. Based on these observations, we can speculate that the preimplantation form of the methyltransferase is associated with the selective maintenance of the maternal RSVIgmyc methylation pattern during preimplantation development.

Reproduction and cyclical changes in DNA methylation.

Our notion of RSVIgmyc imprinting is that it develops as a consequence of changes in methylation throughout the reproductive cycle (erasure and establishment stages during gametogenesis and maintenance and persistence stages during embryogenesis). Interestingly, each of these stages in RSVIgmyc imprinting is also associated with changes in the genome-wide (global) level of genomic DNA methylation. For instance, the erasure of RSVIgmyc parent-specific methylation patterns in primordial germ cells is associated with a virtual absence of genomic methylation in primordial germ cells (7, 14, 18). Both the germ line establishment stage and the embryonic persistence stage, in which one or both of the parental alleles of RSVIgmyc become more methylated, occur roughly coincident with increases in global methylation (7, 18, 39). Moreover, during the maintenance stage, in which the paternal RSVIgmyc allele loses its methylation, there is a loss of a substantial amount of genomic methylation. Because many of the changes in RSVIgmyc methylation are paralleled by changes in global methylation, we must consider the possibility that changes in RSVIgmyc methylation at one or more of the four stages (erasure, establishment, maintenance, or persistence) may not be specific to the mechanism of genomic imprinting. Rather, these changes may serve a more general purpose, and they may affect both nonimprinted genes and imprinted genes. It is notable that only the maintenance stage possesses an event, namely the maintenance of the heavily methylated maternal RSVIgmyc allele, that is exceptional to the reduction in global methylation during preimplantation development (7). Because this loss of global methylation may be due to either an active or a passive process of demethylation (38), it is possible that the maintenance stage of the maternal RSVIgmyc methylation is due to the inhibition of demethylation. Therefore, because of this unusual epigenetic inheritance feature of preimplantation development, the maintenance stage of RSVIgmyc imprinting may utilize a molecular mechanism specific to imprinted genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Victor Tybulewicz for the pPNT plasmid. We also express our gratitude to Kris Fafalios and Daphne Preisach for their technical assistance. We thank Richard Carthew for his comments and assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant HD 32940 from the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center through NIH National Center for Resources resource grant 2 P41 RR06009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainscough J F-X, Surani M A. Organization and control of imprinted genes: the common features. In: Russo V E A, Martienssen R A, Riggs A D, editors. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bestor T H. Activation of mammalian DNA methyltransferase by cleavage of a Zn-binding regulatory domain. EMBO J. 1992;11:2611–2618. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bestor T H, Ingram V. Two species of DNA methyltransferase from murine erythroleukemia cells: purification, sequence, specificity, and mode of interaction with DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5559–5563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.18.5559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson L L, Page A W, Bestor T H. Localization and properties of DNA methyltransferase in preimplantation mouse embryos: implications for genomic imprinting. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2536–2541. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaillet J R. DNA methylation and genomic imprinting in the mouse. Semin Dev Biol. 1992;3:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaillet J R. Genomic imprinting: lessons from mouse transgenes. Mutat Res. 1994;307:441–449. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Chaillet, J. R. Unpublished data.

- 7.Chaillet J R, Vogt T F, Beier D R, Leder P. Parental-specific methylation of an imprinted transgene is established during gametogenesis and progressively changes during embryogenesis. Cell. 1991;66:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90140-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaillet J R, Bader D S, Leder P. Regulation of genomic imprinting by gametic and embryonic processes. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1177–1187. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christofori G, Hanahan D. Molecular dissection of multi-stage tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feil R, Walter J, Allen N D, Reik W. Developmental control of allelic methylation in the imprinted mouse Igf2 and H19 genes. Development. 1994;120:2933–2943. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holliday R, Pugh J E. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science. 1975;187:226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holliday R, Ho T, Paulin R. Gene silencing in mammalian cells. In: Russo V E A, Martienssen R A, Riggs A D, editors. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahner D, Stuhlmann H, Stewart C L, Harbers K, Lohler J, Simon I, Jaenisch R. De novo methylation and expression of retroviral genomes during mouse embryogenesis. Nature. 1982;298:623–628. doi: 10.1038/298623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kafri T, Ariel M, Brandeis M, Shemer R, Urven L, McCarrey J, Cedar H, Razin A. Developmental pattern of gene-specific DNA methylation in the mouse embryo and germ line. Genes Dev. 1992;6:705–714. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirsch I R, Ravetch J V, Kwan S P, Max E E, Ney R L, Leder P. Multiple immunoglobulin switch region homologies outside the heavy chain constant region locus. Nature. 1981;293:585–587. doi: 10.1038/293585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melton D A, Krieg P A, Rebagliati M R, Maniatis T, Zinn K, Green M. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7035–7056. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mertineit C, Yoder J A, Taketo T, Laird D W, Trasler J M, Bestor T H. Sex-specific exons control DNA methyltransferase in mammalian germ cells. Development. 1998;125:899–907. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monk M, Boubelik M, Lehnert S. Temporal and regional changes in DNA methylation in the embryonic, extraembryonic and germ cell lineages during mouse embryo development. Development. 1987;99:371–382. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa O, Eccles M R, Szeto J, McNoe L A, Yun K, Mow M A, Smith P J, Reeve A E. Relaxation of insulin-like growth factor gene imprinting implicated in Wilms’ tumour. Nature. 1993;362:749–751. doi: 10.1038/362749a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rainier S, Johnson L A, Dobry C J, Ping A J, Grundy P E, Feinberg A P. Relaxation of imprinted genes in human cancer. Nature. 1993;362:747–749. doi: 10.1038/362747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riggs A D. X inactivation, differentiation, and DNA methylation. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1975;14:9–25. doi: 10.1159/000130315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riggs A D, Porter T N. X-chromosome inactivation and epigenetic mechanisms. In: Russo V E A, Martienssen R A, Riggs A D, editors. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shemer R, Razin A. Establishment of imprinted methylation patterns during development. In: Russo V E A, Martienssen R A, Riggs A D, editors. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon D, Stuhlmann H, Jahner D, Wagner H, Werner E, Jaenisch R. Retrovirus genomes methylated by mammalian but not bacterial methylase are noninfectious. Nature. 1983;304:275–277. doi: 10.1038/304275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer-Sam J, Riggs A D. X chromosome inactivation and DNA methylation. In: Jost J, Saluz H, editors. DNA methylation: molecular biology and biological significance. Berlin, Germany: Birkhauser Verlag; 1993. pp. 358–384. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solter D. Differential imprinting and expression of maternal and paternal genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:127–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stein R, Gruenbaum Y, Pollack Y, Razin A, Cedar H. Clonal inheritance of the pattern of DNA methylation in mouse cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:61–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart C L, Stuhlmann H, Jahner D, Jaenisch R. De novo methylation, expression, and infectivity of retroviral genomes introduced into embryonal carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4098–4102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart T A, Pattengale P K, Leder P. Spontaneous mammary adenocarcinomas in transgenic mice that carry and express MTV/myc fusion genes. Cell. 1984;38:627–637. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoger R, Kubicka P, Liu C-G, Kafri T, Razin A, Cedar H, Barlow D P. Maternal-specific methylation of the imprinted Igf2r locus identifies the expressed locus as carrying the imprinting signal. Cell. 1993;73:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90160-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swain J L, Stewart T A, Leder P. Parental legacy determines methylation and expression of an autosomal transgene: a molecular mechanism for parental imprinting. Cell. 1987;50:719–727. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremblay K D, Saam J R, Ingram R S, Tilghman S M, Bartolomei M S. A paternal-specific methylation imprint marks the alleles of the mouse H19 gene. Nat Genet. 1995;9:407–413. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tremblay K D, Duran K L, Bartolomei M S. A 5′ 2-kilobase-pair region of the imprinted mouse H19 gene exhibits exclusive paternal methylation throughout development. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4322–4329. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tucker K L, Beard C, Dausman J, Jackson-Grusby L, Laird P W, Lei H, Li E, Jaenisch R. Germ-line passage is required for establishment of methylation and expression patterns of imprinted but not of nonimprinted genes. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1008–1020. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.8.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tybulewicz V L J, Crawford C E, Jackson P K, Bronson R T, Mulligan R C. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell. 1991;65:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weichman K, Chaillet J R. Phenotypic variation in a genetically identical population of mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5269–5274. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss A, Keshet I, Razin A, Cedar H. DNA demethylation in vitro: involvement of RNA. Cell. 1996;86:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoder J A, Walsh C P, Bestor T H. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]