Abstract

Purpose

Antihypertensive medication is an effective way to control blood pressure. However, some studies reported that it may affect patients’ sleep quality during the treatment. Due to the inconsistency of present results, a comprehensive systematic review and network meta-analysis are needed.

Methods

Electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, WEB OF SCIENCE, PUBMED) were searched up to April 10th, 2021 including no restriction of publication status. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental studies or cohort studies were eligible. The network meta-analysis was used within a Bayesian framework.

Results

Finally, 16 publications (including 12 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies) with 404 subjects were included in this study. Compared to placebo, the results of the network meta-analysis showed that diuretics were effective in improving sleep apnea with a mean difference (MD) of − 15.47 (95% confidence interval [CI]: − 23.56, − 6.59) which was consistent with the direct comparison result (MD: − 17.91; 95% CI − 21.60, − 14.23). In addition, diuretics were effective in increasing nocturnal oxygen saturation with an MD of 3.64 (95% CI 0.07, 7.46). However, the effects of β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, and the others on sleep apnea were not statistically significant. Additionally, the effects of antihypertensive medication on the total sleep time (min), rapid eye movement (%), and sleep efficiency (%) were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Our study found that diuretics could effectively reduce the severity of sleep apnea in hypertensive patients. However, the effects of antihypertensive drugs on sleep characteristics were not found.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s41105-022-00391-8.

Keywords: Hypertension, Antihypertensive medication, Sleep apnea, Sleep characteristics

Introduction

Hypertension is a serious medical condition affected by multiple factors. In recent years, a growing number of studies indicated that sleep duration [1–5], sleep quality [6–9], and sleep disorder [10–13] were associated with the occurrence of hypertension. On the other hand, abundant data suggested that treatment of hypertension may affect sleep status [14, 15]. Thus, exploring the effects of antihypertensive medication on sleep could improve the treatment and management of hypertension.

Diuretics, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers (CCB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB), and α-blockers are the six categories of antihypertensive pharmaceuticals used in the clinical practice. The literature showed that β-blockers could cause some adverse events, such as insomnia, depression, or nightmares due to their pharmacological effects [16]. Testa et al. found captopril could relieve sleep disturbance but enalapril could exacerbate its severity, even though they belong to the same class of antihypertensive drug (ACEI) [17]. Other researchers assessed the effects of two antihypertensive drugs on sleep quality using a sleep scale and concluded that CCB (nicardipine) may not have effects on sleep quality while the diuretics (trichlormethiazide) may have modest effects [18]. Walsh et al. found that the changes in actual sleep time were not statistically significant, but rapid eye movement (REM) increased after the treatment with ACEI (captopril) [19]. A cross-sectional study, conducted in hypertensive patients with OSA, reported that CCB was associated with a reduction in total sleep time of patients(P = 0.037); however, the effects on sleep efficiency were not found [20].

Previous studies showed that antihypertensive drugs may have effects on the sleep status of hypertensive patients, depending on the agent used, however, the results were still inconsistent. Presently, the studies on the effects of antihypertensive drugs on sleep status were still insufficient. In addition, current studies focused on one special type of drug or compared with standard treatment control, but few studies analyzed the impacts of multiple interventions compared to placebo. Network meta-analysis (NMA) [21] integrates direct and indirect effects by creating a network diagram that can simultaneously evaluate the effects of multiple interventions. Hence, the objectives of our study were, therefore, to conduct a systematic review and NMA to explore the different effects of various antihypertensive drugs imposed on sleep status.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [22]. To obtain the target literature, we systematically searched literature published in MEDLINE, EMBASE, WEB OF SCIENCE, and PUBMED before April 10th 2021. The search strategies included the following key terms: (1) hypertension or blood pressure or BP or diastolic pressure or systolic pressure or DBP or SBP; (2) antihypertensive drugs or antihypertensive treatment or diuretics or β-blockers or calcium channel blockers (CCB) or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB) or α-blockers; (3) sleep apnea or obstructive sleep apnea or central sleep apnea or sleep disorder breathing (SDB); (4) sleep disorder or sleep quality or sleep duration or quality of life (QOL). In addition, we also read references from relevant reviews and meta-analyses to get qualified articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion of all studies was in English and details of inclusion criteria were (1) study population—patients aged 18 years and older with hypertension; (2) intervention—use of antihypertensive drugs; (3) control—use of antihypertensive drugs or placebo; (4) outcome—sleep apnea (including obstructive, central and mixed sleep apnea) severity measured by apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) or respiratory disturbance index (RDI); nocturnal oxygen saturation; sleep characteristics including total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency and REM sleep; (5) study design—prospective interventional human trial (including quasi-experimental study) and cohort study.

Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers (Y.YN, Z.ZQ) independently screened the relevant literature based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer (C.WZ) was approached. After study selection, two reviewers (Y.YN, Z.ZQ) individually extracted information about the first author, publishing year, population characteristics, study design, dosage and duration of antihypertensive drug use, and outcome indicators related to sleep. Replacing the missing mean with the median and the missing SD with R/4 [23]. SD for post-treatment was calculated according to Cochrane Handbook if SD reported for change from baseline.

Quality assessment

The Jadad scale [24], including randomization, blinding, withdrawals, and dropouts, was used to evaluate the quality of included RCTs. Scored in 0–5, with 3 and above being considered high quality. For non-randomized studies, the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) [25] consisting of 12 items was utilized for quality assessment, and the last 4 items were specific for comparative studies. The total score of 16 or 24 points, the higher the score the greater the quality of the study.

Statistical analysis

We performed pairwise meta-analyses using the random-effects model for every treatment comparison. And statistics was used to measure heterogeneity. The NMA within the Bayesian framework was performed, and effect sizes were mean difference (MD) and 95%confidence interval (CI) derived from the random-effects model. We estimated the posterior densities for all unknown parameters using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for each model. Each chain iterates 50,000 times, and 10,000 pre-iterations were set to eliminate the influence of the initial value for statistical analysis. Additionally, the normal likelihood was used for the continuous outcome. D(θ) was used to evaluate whether the model’s fit is satisfactory [26], when D(θ) is close to the total data points, the model achieves a better fitting effect. Besides, the node-splitting method was employed to evaluate the inconsistency. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) was applied to rank the antihypertensive treatments optimally. Analyses were conducted using Review Manager (Revman) Version5.3 for pairwise meta-analysis, and R (version 3.6.3) for network meta-analysis using the “gemtc” package. Unless otherwise specified, the level of significance was set to 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

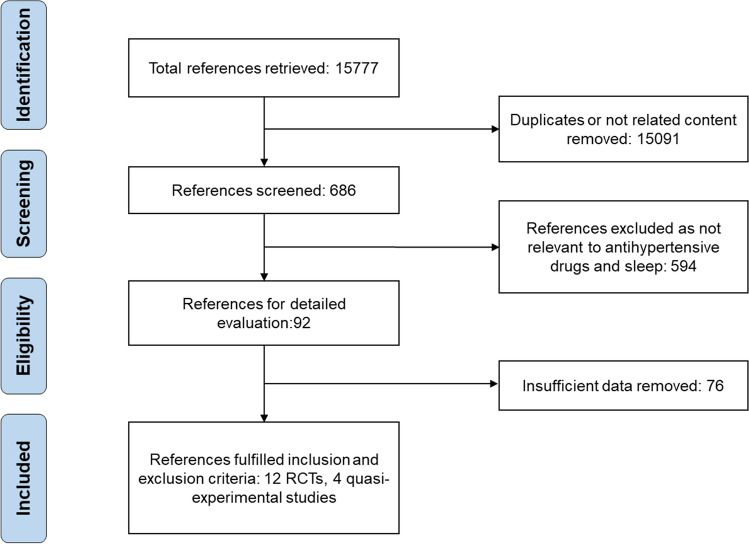

A total of 15,777 articles were screened. After selection, 12 RCTs and four quasi-experimental studies including 404 individuals met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The publication year varied from 1989 to 2016, and the duration of studies ranged from 3 days to 4 months. Diuretics including spironolactone, metolazone, and hydrochlorothiazide were used in six studies; ACEI including captopril, Enalapril, and cilazapril were used in 6 studies. Additionally, only the male population was included in 7 studies and the BMI metric was reported in 14 studies. Details of 14 studies were presented in Supplementary 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of literature search

Risk of bias assessment

The Jadad scores of the 12 RCTs studies showed that four were of low quality and scored two points; 8 studies were of high quality and only one had five points. MINORS scores ranged from 10 to 12 (mean: 10.5, median: 10.5) across non-randomized trials. In conclusion, the overall risk was modestly high, the bias mainly came from the randomization procedure and non-reported details of lost and withdrawal for RCTs and lack of consecutive patients, and prospective calculation of sample size for non-randomized studies. More details are shown in supplementary 2 Sect. 1.

Effect on sleep apnea

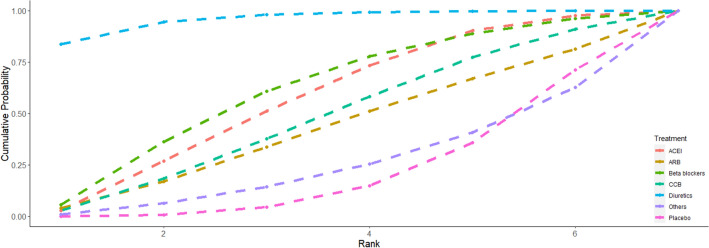

Diuretics, β-blockers, CCB, ACEI, ARB, others, and placebo were analyzed. The results of sleep apnea severity were reported in 14 studies, the network structure diagram between these studies is described in Fig. 2. The width of the lines was defined as proportional to the number of trials comparing every pair of treatments. The size of every circle was meant to be proportional to the number of randomized participants (sample size). As the figure indicates that outside of the placebo group (10 studies, 164 participants), the maximum number of participants belonged to the ACEI group, with a total of 98 participants across five studies.

Fig. 2.

Evidence network of eligible comparisons for seven treatments. CCB calcium channel blockers, ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin-receptor blockers

The results of the direct pairwise meta-analysis and network meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. The result of the direct pairwise meta-analysis (lower triangle) showed that diuretics decreased AHI by − 17.91(95% CI − 21.60, − 14.23) versus placebo which means diuretics had a statistically significant effect on the severity of sleep apnea. The result of NMA (upper triangle) was like that preceding pairwise meta-analysis, diuretics had an advantage in alleviating the severity of sleep apnea. Treatment with diuretics resulted in a significantly greater decrease in AHI, with a mean difference of − 15.47 (95% CI − 23.56, − 6.59), compared with placebo. The others can exacerbate the severity of sleep apnea compared with diuretics, with a mean difference of 15.47 (95% CI 0.82, 28.90). The effects of β-blockers, CCB, ACEI, and ARB on sleep apnea were not statistically significant, compared to placebo.

Table 1.

Results of direct comparison (lower triangle) and network meta-analysis (upper triangle)

| Placebo |

− 15.47 (− 23.56, − 6.59) |

− 6.31 (− 17.94, 5.33) |

− 3.96 (− 15.4, 7.47) |

− 5.33 (− 13.8, 2.88) |

− 3.22 (− 17.87, 10.57) |

0.04 (− 11.84, 11.65) |

|

− 17.91 (− 21.60, − 14.23) |

Diuretics |

9.12 (− 4.21, 21.92) |

11.47 (− 2.25, 24.53) |

10.13 (− 1.91, 21.24) |

12.24 (− 3.70, 26.56) |

15.47 (0.82, 28.90) |

|

− 5.00 (− 13.38, 3.38) |

− 3.73 (− 17.20, 9.74) |

β-blockers |

2.36 (− 11.32, 15.91) |

0.98 (− 12.22, 13.84) |

3.17 (− 10.16, 15.46) |

6.34 (− 9.40, 21.55) |

|

1.00 (− 13.12, 15.12) |

− 0.90 (− 14.20, 12.40) |

2.83 (− 6.65, 12.31) |

CCB |

− 1.36 (− 14.02, 11.23) |

0.72 (− 14.46, 15.46) |

3.99 (− 9.64, 17.19) |

|

− 5.21 (− 17.70, 7.27) |

− 1.10 (− 18.33, 16.13) |

2.63 (− 11.86, 17.12) |

− 0.20 (− 14.53, 14.13) |

ACEI |

2.13 (− 13.14, 16.90) |

5.36 (− 7.25, 17.74) |

| – |

5.90 (− 7.08, 18.88) |

3.06 (− 11.55, 17.67) |

6.80 (− 1.98, 15.58) |

7.00 (− 7.04, 21.04) |

ARB |

3.18 (− 13.61, 20.82) |

|

4.40 (− 2.21, 11.01) |

– | – |

− 0.25 (− 12.91, 12.41) |

2.00 (− 12.90, 16.90) |

– | Others |

CCB calcium channel blockers, ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin-receptor blockers

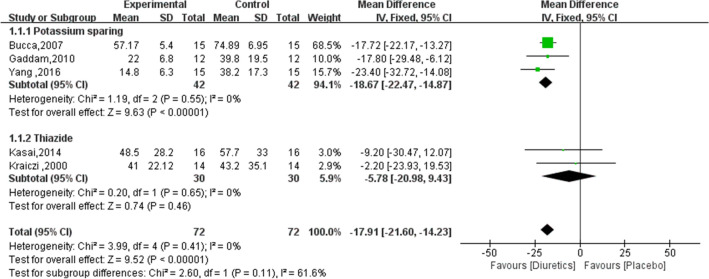

The optimal ranking of antihypertensive drugs and placebo on sleep apnea is shown in Fig. 3. Apparently, diuretics had a larger surface under the cumulative ranking curve (83.66%), implying a favorable effect on the relief of sleep apnea. In addition, treatment with other antihypertensive medications had a lower ranking indicating the relatively weak ability to decrease the AHI.

Fig. 3.

The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) of different treatments on sleep apnea. CCB calcium channel blockers, ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin-receptor blockers

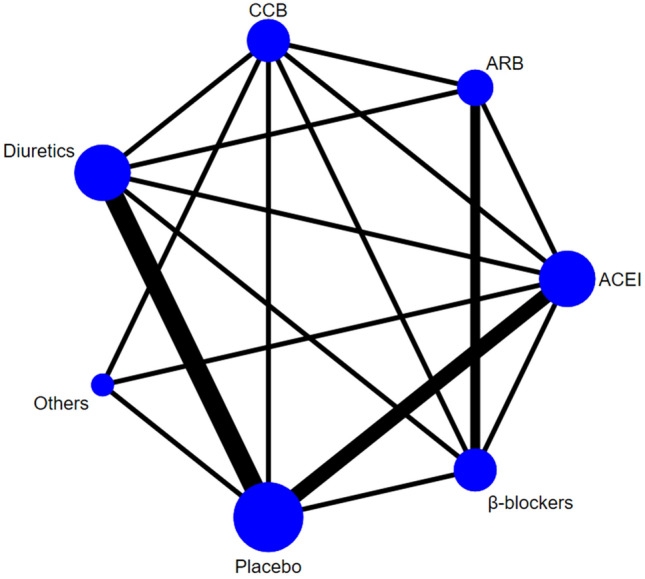

Five studies were included in the subgroup meta-analysis to explore the effects of different diuretics on sleep apnea. The results showed (Fig. 4) that potassium diuretics (spironolactone) had the greatest effect on sleep apnea in hypertensive patients with a mean difference of − 18.67 (95% CI − 22.47, − 14.87). Thiazide diuretics (metolazone and hydrochlorothiazide) tended to reduce the severity of sleep apnea in hypertensive patients, but it was not statistically significant with a mean difference of − 5.78(95% CI − 20.98, 9.43).

Fig. 4.

The subgroup meta-analysis results of diuretics on sleep apnea

Effect on lowest oxygen saturation

We further analyzed the changes in nocturnal oxygen saturation which had an important role in predicting the coexistence or development of sleep apnea with hypertension. Five studies reported the effects of diuretics, β-blockers, and ACEI on the lowest oxygen saturation. The results of NMA showed that diuretics increased the lowest oxygen saturation, with a pooled MD of 3.64 (95% CI 0.07, 7.46), consistent with direct comparisons (MD: 2.39; 95% CI 0.70, 4.09), which may be clinically significant. However, there were no statistically significant effects of β-blockers and ACEI on the lowest oxygen saturation (Supplementary2 Sect. 2).

Effect on sleep characteristics

We examined whether the use of antihypertensive medications leads to changes in sleep characteristics, including TST (min), sleep efficiency (%), and REM (%). The NMA results indicated that antihypertensive drugs had no effect on sleep characteristics with all 95%CI including 0. The MD of diuretics at total sleep time was − 9.50 (95% CI − 99.31, 80.21) and the MD of CCB at sleep efficiency was − 3.20 (95% CI − 9.82, 3.54). For REM, the NMA result of ACEI was 3.92 (95% CI − 2.39, 10.35) versus placebo. See Supplementary2 Sect. 3.

Heterogeneity and inconsistency test

The values of D(θ) in this study were all close to the total data points with heterogeneity (I2) of 0%, 9%, 5%, 16%, and 7%, respectively, which indicated that the model had a good overall fit and low heterogeneity. Additionally, we conducted a node-splitting method to verify the inconsistency. Section 4 of supplementary 2 unveiled the detailed results, NMA satisfied the consistency condition, there was no difference between direct and indirect comparisons with all P values were greater than 0.05.

Sensitivity analyses

Since most of the study population had not only hypertension but also sleep apnea, and having sleep apnea may make the antihypertensive drugs have different effects on the severity of sleep apnea. We conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding two studies in which the study population did not suffer from sleep apnea[19, 27]. The results of NMA showed that diuretics still had a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in the sleep apnea severity in patients with hypertension and sleep apnea, decreased AHI by − 16.5 (95% CI − 21.90, − 8.95). The AHI changed 6.66% in our sensitivity analysis. Details are presented in Supplementary2 Sect. 5.

Discussion

The effects of antihypertensive drugs on sleep status were discussed in clinic practices, however, the results were not consistent. In this study, we systematically reviewed and conducted the NMA with the Bayesian framework, ultimately including 16 studies. Separately, we evaluated the effects of antihypertensive drugs (diuretics, β-blockers, CCB, ACEI, ARB, others) on five outcomes (AHI, lowest oxygen saturation, TST, sleep efficiency, and REM sleep). In our analysis, we observed that diuretics, especially potassium diuretics (spironolactone), significantly reduced the severity of sleep apnea in hypertensive patients and were effective in increasing the lowest oxygen saturation, yet other antihypertensive drugs had no statistically significant effects on these outcomes. There were some differences between our findings and the previous study. Khurshid et al. [28] indicated that treatment with antihypertensive agents could significantly reduce the severity of OSA and diuretics may be more effective by conducting a direct pairwise meta-analysis. However, without distinguishing between classes of antihypertensive drugs, the effect of diuretics may amplify the effect of other antihypertensive drugs on the severity of OSA.

For diuretics, the positive effects on sleep apnea were observed in our study, which was similar to the results from previous studies [28], for example, the spironolactone [29–32] were reported to have a surprising effect on reducing AHI and increasing lowest oxygen saturation [32]. Revol et al. [33] showed that the beneficial effect of diuretics was real for overweight or moderately obese OSA patients with hypertension, and diuretics also had a positive effect in hypertensive patients with severe OSA and diastolic heart failure [29]. By now, the main explanation for the mechanism of the effect of diuretics on sleep apnea was that diuretics can influence the overnight rostral fluid shift through fluid regulation when the patient was in the supine position, and this fluid accumulation may increase the degree of upper airway collapse during sleep [34, 35]. Oded et al. [34] demonstrated that the redistribution of body fluid from lower extremities to neck and pharyngeal tissues in the supine position caused an increase in central neck blood volume and capillary pressure, compressing the upper airway and impeding airflow. The AHI showed a strong association with nocturnal leg fluid expulsion (=0.56, P < 0.0001). Redolfi et al. [36, 37] further explored the effects of this fluid transfer on OSA using compressing stockings and showed a 36% reduction in AHI with the fluid transfer.

In our study, the effects of other antihypertensive drugs on sleep apnea and sleep characteristics were not found. It was not consistent with some previous studies, which may result in that these studies were conducted in different situations. For CCB, some cross-sectional studies found CCB was the only class of antihypertensive drugs to reduce sleep duration [20] and REM sleep [38]. However, in our study, the included experimental studies did not draw a causal relationship between antihypertensive drugs and short sleep duration and short REM. For ACEI and ARB, some researchers [39, 40] argued that they could cause angioedema which may increase AHI in OSA patients, especially when other harmful factors coexist. But this conclusion may be varied according to the different populations, illness severity, and observation periods [41, 42]. In fact, β-blockers were usually used as the agent for the treatment of heart failure [43, 44] and were not often recommended as first- or second-line antihypertensive drugs in some current guidelines, however, the data were still included in our research to obtain sufficient data to investigate the effects of other drugs.

As far as we know, hypertensive patients are often accompanied by sleep disturbances, especially resistant hypertension [45]. However, when using antihypertensive drugs, the potential impact on sleep may be ignored and even led to poor quality of life for patients. Our finding showed that diuretics may have a positive effect on sleep apnea. Continue positive airway pressure (CPAP), which was considered a standard treatment, effectively improved SDB [46] and lowered BP by approximately 2 mmHg [47, 48]. However, many patients with OSA struggled to tolerate CPAP treatment, resulting in poor compliance and consequently reduced control over the severity of OSA [49]. Therefore, the results of our study, that diuretics can improve sleep apnea in hypertensive patients, is probably helpful in finding a new and better tolerated treatment for patients with sleep apnea. Although some studies found that antihypertensive drugs had effects on sleep characteristics, such as TST, sleep efficiency or REM, but from the NMA results in our study, the effects of antihypertensive medications were not found. It suggested that some in-depth research should focus on other aspects of sleep, and the underlying mechanism should be discussed further.

There are several strengths in our analyses. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to use NMA to thoroughly explore the effects of different antihypertensive drugs on sleep status in patients with hypertension. Second, the Bayesian model based on NMA was performed in this research, which was considered the most suitable method for multiple-treatments NMA. However, some limitations need to be considered. First, some of the trials included in this analysis were not especially studying sleep status, potentially posing a risk of misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis. Second, potential bias may result from the absence of placebo control, small sample size, and short follow-up period in the included studies. Third, there are some sleep-related indicators, such as daytime sleeplessness, snoring, and sleep quality, which were not considered due to the present insufficient data.

Conclusion

Our study focused on the effects of several common antihypertensive drugs on sleep apnea and sleep characteristics to provide some suggestions in clinical practice. We observed that the severity of sleep apnea was significantly lower in hypertensive patients treated with diuretics and the lowest oxygen saturation increased significantly, yet the effects of other antihypertensive drugs were not found. It is necessary to conduct more long-term, large-scale studies to determine the effects of antihypertensive drugs on different aspects of sleep and further to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Sincere appreciation to all researchers for their contributions to this study.

Author contributions

ZZQ and YYN contributed equally and involved in data extraction, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. CWZ was involved in data analysis and interpretation of the manuscript. GDQ involved in the paper planning and contributed largely to the manuscript revision. WXM and ZYW were involved with the co-drafting of the manuscript. GDQ and CWZ contributed equally.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose. This study was supported by the Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China [grant number:18XJC910001].

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Weizhong Chen, Email: wejone@126.com.

Dongqing Gu, Email: dongqing.gu@vip.163.com.

References

- 1.Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, et al. Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension: the Whitehall II Study. Hypertension. 2007;50(4):693–700. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang J, Wheaton AG, Keenan NL, et al. Association of sleep duration and hypertension among US adults varies by age and sex. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(3):335–341. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first national health and nutrition examination survey. Hypertension. 2006;47(5):833–839. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottlieb DJ, Redline S, Nieto FJ, et al. Association of usual sleep duration with hypertension: the sleep heart health study. Sleep. 2006;29(8):1009–1014. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J, Jo I. Age-dependent association between sleep duration and hypertension in the adult Korean population. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(12):1286–1291. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruno RM, Palagini L, Gemignani A, et al. Poor sleep quality and resistant hypertension. Sleep Med. 2013;14(11):1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiorentini A, Valente R, Perciaccante A, Tubani L. Sleep's quality disorders in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114(2):E50–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu RQ, Qian Z, Trevathan E, et al. Poor sleep quality associated with high risk of hypertension and elevated blood pressure in China: results from a large population-based study. Hypertens Res. 2016;39(1):54–59. doi: 10.1038/hr.2015.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rod NH, Vahtera J, Westerlund H, et al. Sleep disturbances and cause-specific mortality: results from the GAZEL cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(3):300–309. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budhiraja R, Roth T, Hudgel DW, et al. Prevalence and polysomnographic correlates of insomnia comorbid with medical disorders. Sleep. 2011;34(7):859–867. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and incident hypertension: the Penn State Cohort. Hypertension. 2012;60(4):929–935. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou H, Zhao Y, Yu W, et al. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2018;8(1):010405. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.010405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32(4):491–497. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziegler MG, Milic M, Sun P. Antihypertensive therapy for patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283402eb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson DF, Pierce DR. Drug-induced nightmares. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33(1):93–98. doi: 10.1345/aph.18150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ram CV. Antihypertensive drugs: an overview. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2002;2(2):77–89. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200202020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Testa MA, Anderson RB, Nackley JF, Hollenberg NK. Quality of life and antihypertensive therapy in men. A comparison of captopril with enalapril The Quality-of-Life Hypertension Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(13):907–913. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304013281302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogihara T, Kuramoto K. Effect of long-term treatment with antihypertensive drugs on quality of life of elderly patients with hypertension: a double-blind comparative study between a calcium antagonist and a diuretic. NICS-EH Study Group. National Intervention Cooperative Study in Elderly Hypertensives. Hypertens Res. 2000;23(1):33–37. doi: 10.1291/hypres.23.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh JT, Andrews R, Starling R, et al. Effects of captopril and oxygen on sleep apnoea in patients with mild to moderate congestive cardiac failure. Br Heart J. 1995;73(3):237–241. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nerbass FB, Pedrosa RP, Genta PR, et al. Calcium channel blockers are independently associated with short sleep duration in hypertensive patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 2011;29(6):1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283462e8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(2):80–97. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Stat Methodol) 2002;64(4):583–639. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartel P. Short-term antihypertensive medication does not exacerbate sleep-disordered breathing in newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10(6):640–645. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(96)00507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khurshid K, Yabes J, Weiss PM, et al. Effect of antihypertensive medications on the severity of obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(8):1143–1151. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bucca CB, Brussino L, Battisti A, et al. Diuretics in obstructive sleep apnea with diastolic heart failure. Chest. 2007;132(2):440–446. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaddam K, Pimenta E, Thomas SJ, et al. Spironolactone reduces severity of obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with resistant hypertension: a preliminary report. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24(8):532–537. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasai T, Bradley TD, Friedman O, Logan AG. Effect of intensified diuretic therapy on overnight rostral fluid shift and obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32(3):673–680. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Zhang H, Cai M, et al. Effect of spironolactone on patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38(5):464–468. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2015.1131290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Revol B, Jullian-Desayes I, Bailly S, et al. Who may benefit from diuretics in OSA?: A propensity score-match observational study. Chest. 2020;158(1):359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman O, Bradley TD, Chan CT, et al. Relationship between overnight rostral fluid shift and obstructive sleep apnea in drug-resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;56(6):1077–1082. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.154427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White LH, Bradley TD, Logan AG. Pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnoea in hypertensive patients: role of fluid retention and nocturnal rostral fluid shift. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29(6):342–350. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redolfi S, Arnulf I, Pottier M, et al. Effects of venous compression of the legs on overnight rostral fluid shift and obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;175(3):390–393. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redolfi S, Arnulf I, Pottier M, et al. Attenuation of obstructive sleep apnea by compression stockings in subjects with venous insufficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(9):1062–1066. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201102-0350OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruttanaumpawan P, Nopmaneejumruslers C, Logan AG, et al. Association between refractory hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 2009;27(7):1439–1445. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832af679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown T, Gonzalez J, Monteleone C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema: A review of the literature. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2017;19(12):1377–1382. doi: 10.1111/jch.13097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cicolin A, Mangiardi L, Mutani R, Bucca C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and obstructive sleep apnea. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(1):53–55. doi: 10.4065/81.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Rijnsoever EW, Kwee-Zuiderwijk WJ, Feenstra J. Angioneurotic edema attributed to the use of losartan. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(18):2063–2065. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.18.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedner T, Samuelsson O, Lunde H, et al. Angio-oedema in relation to treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. BMJ. 1992;304(6832):941–946. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6832.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamura A, Kawano Y, Kadota J. Carvedilol reduces the severity of central sleep apnea in chronic heart failure. Circ J. 2009;73(2):295–298. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamura A, Kawano Y, Naono S, et al. Relationship between beta-blocker treatment and the severity of central sleep apnea in chronic heart failure. Chest. 2007;131(1):130–135. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carnethon MR, Johnson DA. Sleep and Resistant Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21(5):34. doi: 10.1007/s11906-019-0941-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hla KM, Skatrud JB, Finn L, et al. The effect of correction of sleep-disordered breathing on BP in untreated hypertension. Chest. 2002;122(4):1125–1132. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alajmi M, Mulgrew AT, Fox J, et al. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lung. 2007;185(2):67–72. doi: 10.1007/s00408-006-0117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fava C, Dorigoni S, Dalle Vedove F, et al. Effect of CPAP on blood pressure in patients with OSA/hypopnea a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2014;145(4):762–771. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marin JM, Agusti A, Villar I, et al. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2169–2176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.