Abstract

Sleep disorders are prevalent among college students and are associated with poor academic performance. Few studies have included a clinical interview to comprehensively assess sleep disorder diagnostic criteria or assessed academic functioning (e.g., class attendance). College students (n = 277) were recruited to complete sleep questionnaires, a sleep diary for two weeks and, if indicated, a semi-structured clinical interview. Based on questionnaire data, students were categorized as being at risk versus not at risk for a sleep disorder. Based on the semi-structured clinical interview, students were categorized as meeting versus not meeting diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder. Academic performance and functioning were assessed in all students to determine the association between the presence of sleep disorders and academic performance and functioning. In models adjusted for age, sex, race, and credit hours completed, students at risk for a sleep disorder (38.6% of the sample) reported missing more classes due to oversleeping (p = 0.001) and illness (p = 0.014), and fell asleep in class more often (p = 0.030) than their peers not at risk. Students with a sleep disorder (24.8% of the sample) reported missing more classes due to illness (p = 0.024) than those without a sleep disorder. There were no differences in grade point average between students at risk versus not at risk or with versus without a sleep disorder. Sleep disorder symptoms and diagnoses were significantly associated with worse academic functioning but not performance. Assessment and treatment of sleep disorders early in college students’ career may be important for optimal academic functioning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s41105-022-00423-3.

Keywords: Sleep disorders, Insufficient sleep, Insomnia, Delayed sleep–wake phase disorder, Academic performance, Academic functioning

Introduction

Sleep complaints are common among college students, with the most frequently reported complaints being difficulties falling asleep, difficulties maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, poor sleep quality, and early morning fatigue/sleepiness [1–6]. Studies have reported that between 10.9% and 19.3% of college students experience difficulties initiating sleep, and between 5.6% and 10.9% of college students experience difficulties maintaining sleep [3, 7, 8]. The prevalence of at least one sleep disorder in college students is approximately 27% [9].

The association between sleep complaints, sleep disorders, and academic performance is unclear [9–17]. Taylor et al. [18] reported that students with insomnia did not have a lower GPA, suggesting that poor sleep may impact general cognitive function but may not necessarily result in a lower GPA [19]. Delayed sleep–wake phase disorder (DSWPD) is specifically associated with an increase in tardiness and absenteeism, early morning hypersomnolence and/or fatigue, and a decrease in academic performance [1–3]. Evidence suggests that circadian misalignment may also be associated with decreased academic performance and self-reported poor sleep quality [20, 21]. At least one study has suggested that sleep quality may have a greater impact on cognitive function than does sleep quantity [11]. College students appear to frequently suffer from both poor sleep quality and quantity, making negative outcomes likely in this population [9, 18].

The purpose of the current study was to extend previous research into the association of college students’ sleep on academic performance by (1) incorporating a semi-structured clinical interview to more accurately distinguish between students with and without a sleep disorder and (2) assessing subjective measures of academic performance (i.e., GPA) and academic functioning across multiple domains (i.e., tardiness, attendance). We hypothesized that college students at risk for a sleep disorder, based on a self-report screening questionnaire (i.e., SLEEP-50), and those meeting criteria for a sleep disorder, based on a clinical interview, would both demonstrate greater tardiness, poorer attendance, and lower GPA compared to students not at risk or without a sleep disorder.

Methods

Study overview

Complete details regarding study design, participant selection and enrollment, measures used, and data collected are published in an institutional repository [22]. The current study presents data collected over two years on sleep complaints, sleep disorders, and academic performance and functioning in a slightly larger sample from the manuscript published in the institutional repository. Briefly, undergraduate students were recruited from a Department of Psychology research subject pool. Once a student signed up for the current study, informed consent and all data collection were completed online using Google Documents. Participants initially completed a demographic questionnaire to provide basic data on age, sex, race, and class standing for descriptive analyses, as well as to ensure eligibility to participate in this study. The only inclusion criterion was being between 18 and 25 years of age during the study period to maximize generalizability to all undergraduate students at this institution. The only exclusion criterion was severe psychiatric illness (i.e., active mania or psychosis) that would preclude students from participating in this study. This criterion was assessed at the time of enrollment and no students were excluded on this basis. After completing the demographic questionnaire, participants were invited to complete a self-report screening questionnaire (i.e., SLEEP-50), the Consensus Sleep Diary for Morning over a two-week period, and the morningness–eveningness questionnaire. Participants who voluntarily withdrew or did not complete all questionnaires (n = 87) were not included in these analyses. Students who reported any sleep complaint as occurring “rather much” or “very much” on the SLEEP-50 were contacted to complete a semi-structured clinic interview to assess for diagnostic accuracy. All questionnaires and the clinical interview are described in further detail below. As suggested by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and study team, students who did not endorse any sleep complaints on the SLEEP-50 were unlikely to meet criteria for a sleep disorder and, therefore, were not contacted to complete the clinical interview in an effort to reduce study burden. A total of 277 students were enrolled and completed all phases of the study. Refer to Fig. 1 for the study consort diagram. This study was approved by the IRB and the Department of Psychology Research Subject Pool at the University of Alabama.

Fig. 1.

Consort Diagram

Materials

Academic functioning and performance

Participants self-reported information pertaining to academic performance (i.e., GPA) and functioning (i.e., classes missed per month due to oversleeping, classes missed per month due to illness, frequency of falling asleep in classes per week, and how often the student was sick each semester). Demographic information was also obtained as part of this assessment and included age, sex, race, credit hours completed, and class standing.

The expanded consensus sleep diary for morning (CSD-M)

The CSD-M [23] was used to gather self-reported sleep data each morning for two weeks. The CSD-M provides a record of the time the participant entered bed and the final morning exit from bed, sleep onset latency (SOL), number of awakenings (NWAK), wake time after sleep onset (WASO), terminal wake time before the final morning arising (TWAK), and sleep quality rating (SQR) on a scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very good). The core CSD was slightly modified to include nap time (NAP). Total sleep time (TST), time in bed (TIB), and percent sleep efficiency (SE) were derived from the core CSD variables. These variables and their definitions conform to the recommendations of the Pittsburgh Consensus Conference on evaluating insomnia [24].

Morningness–eveningness questionnaire (MEQ)

The MEQ is a 19-item self-report questionnaire that assess behavioral preferences of an individual, which are thought to be the result of one’s chronotype [25–27]. MEQ scores range from 16 to 86 with lower scores indicating a greater preference for eveningness and higher scores indicating a greater preference for morningness. The scores are categorized as follows: definite evening type (16–30), moderately evening type (31–41), intermediate (42–58), moderately morning type (59–69), and definite morning type (70–86). The MEQ scale was validated on a sample of individuals aged 18–32 years old [27].

SLEEP-50

The SLEEP-50 is a self-report questionnaire that contains 50 items and evaluates common sleep disorder symptoms [28]. The SLEEP-50 contains seven sections that correspond to the following sleep disorder categories: OSA, insomnia, narcolepsy, restless legs syndrome (RLS)/periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders (CRSWD), sleepwalking, and nightmares. There are two sections that assess sleep hygiene and sleep impact on daytime functioning. The SLEEP-50 focuses on the intensity of symptoms rather than their frequency to improve diagnostic specificity, and each item is scored on a four-point scale: 1 (not at all applicable), 2 (somewhat), 3 (rather much), and 4 (very much applicable). For an item to be considered a sleep complaint, a minimum score of three or four is required. Also, each section requires at least one item to be scored as a three or four and a score of three or four on the impact subscale for it to be considered a possible sleep disorder [28]. Validation of the SLEEP-50 was conducted in a sample of college students and demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.85), good test–retest reliability (0.65–0.89), and good sensitivity and specificity for clinical diagnoses (κ = 0.77). For the current study, the SLEEP-50 was used to create two groups: students “at risk” (i.e., those who reported a significant sleep complaint in any domain and who scored high on the impact subscale) and “not at risk” (i.e., those who did not meet the criteria for a sleep disorder) for a sleep disorder. Hereafter, these groups of students are referred to as “at risk” and “not at risk.”

Semi-structured clinical interview

A semi-structured clinical interview developed for and used in an accredited behavioral sleep medicine (BSM) clinic (Appendix A) was used in the current study to assess sleep disorder symptoms reported on the SLEEP-50, as well as to confirm potential diagnoses that could be determined using a clinical interview (OSA, PLMD, and narcolepsy require polysomnography). Semi-structured clinical interviews are commonly used in sleep clinics to comprehensively assess for sleep disorder symptoms and, more importantly, assist with the evaluation of differential diagnoses (e.g., DSWPD versus insomnia) but are rarely used in research studies due to concerns of overburdening research participants. The clinical interview took 15–30 min to complete depending on the number of sleep concerns reported and, in conjunction with responses on the SLEEP-50, the CSD-M, and the MEQ, was used to provide diagnostic accuracy for any potential sleep disorders. The clinical interview was conducted by a fifth-year graduate student with substantial training in a BSM Clinic and who was supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist with certification in BSM. Following the clinical interview, the clinical psychology graduate student and supervising clinical psychologists reviewed all diagnoses for agreement. To reduce participant burden, the clinical interview was conducted among only the students who reported any sleep complaint on the SLEEP-50 and were willing to complete the interview (n = 141). Because the SLEEP-50 can only be used to assess for students at risk or not at risk for a sleep disorder, the clinical interview was used in conjunction with the other measures to identify students who met diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder using the ICSD-2 [29]. Hereafter, these groups are referred to as “sleep disorder” and “no sleep disorder”.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive data were calculated and reported as means and standard deviations, median and inter-quartile range (IQR), or numbers and percentages, as appropriate. Derived variables from the CSD-M (i.e., TIB, TST and SE) were obtained from SOL, NWAK, WASO, and TWAK as described above. Based on the SLEEP-50, students were placed into two groups: “at risk” (n = 107) and “not at risk” (n = 170) for a sleep disorder. Based on the clinical interview and data from the CSD-M and MEQ, students were placed into two groups: “sleep disorder” (n = 35) and “no sleep disorder” (n = 106). There were students who were determined to be “at risk” for a sleep disorder based on the SLEEP-50 but who did not meet diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder and were placed in the “no sleep disorder” group. A Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), adjusting for age, sex, race, and credit hours was used to compare sleep diary characteristics and academic performance and functioning variables across students who were and were not at risk, as well as students who did and did not meet diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder. MANCOVA was chosen to address experiment-wise Type 1 error that occurs with multiple pairwise comparisons and because it is robust to violations of normality. Missing data were excluded listwise to restrict the analyses to students who had complete data on academic performance and functioning. Significance was determined using an alpha level at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistical Software version 25.

Results

Participant characteristics

This sample of undergraduate students had a mean age of 18.8 years (SD = 1.08), were largely female (66.1%), and White (82.3%). A majority of the students (64.3%) were freshmen. Demographic data are presented in Table 1 and sleep and academic performance and functioning data are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of college students at risk, not at risk, and with and without a sleep disorder

| SLEEP-50 | Clinical interview | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Full sample (n = 277) | At risk (n = 107) | Not at risk (n = 170) | p-value | Sleep disorder (n = 35) | No sleep disorder (n = 106) | p-value |

| Age, years | 18.84 ± 1.08 | 18.96 ± 1.03 | 18.76 ± 1.11 | 0.137 | 18.57 ± .85 | 18.70 ± 1.22 | 0.570 |

| Gender % | |||||||

| Female | 183 (66.1%) | 75 (70.1%) | 108 (63.5%) | 0.261 | 22 (62.9%) | 61 (57.5%) | 0.580 |

| Race % | |||||||

| Black | 31 (11.2%) | 12 (11.2%) | 19 (11.2%) | 0.638 | 3 (8.6%) | 16 (15.1%) | 0.301 |

| White | 228 (82.3%) | 87 (81.3%) | 141 (82.9%) | 29 (82.9%) | 84 (79.2%) | ||

| Other | 18 (6.6%) | 8 (7.4%) | 10 (6%) | 3 (8.7%) | 6 (5.6%) | ||

| Class standing % | |||||||

| Freshman | 178 (64.3%) | 61 (57%) | 117 (68.8%) | 0.145 | 25 (71.4%) | 67 (63.2%) | 0.600 |

| Sophomore | 56 (20.9%) | 29 (27.1%) | 29 (17.1%) | 5 (14.3%) | 20 (18.9%) | ||

| Junior | 26 (9.4%) | 12 (11.2%) | 14 (8.2%) | 4 (11.4%) | 10 (9.4%) | ||

| Senior | 15 (5.4%) | 5 (4.7%) | 10 (5.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 9 (8.5%) | ||

| Academic school | |||||||

| Arts and sciences | 96 (34.7%) | 41 (38.3%) | 55 (32.4%) | 0.433 | 16 (45.7%) | 40 (37.7%) | 0.196 |

| Commerce and business administration | 14 (5.1%) | 3 (2.8%) | 11 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.8%) | ||

| Communication and information science | 20 (7.2%) | 8 (7.5%) | 12 (7.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (6.6%) | ||

| Education | 22 (7.9%) | 10 (9.3%) | 12 (7.1%) | 6 (17.1%) | 8 (7.5%) | ||

| Engineering | 39 (14.1%) | 10 (9.3%) | 29 (17.1%) | 1 (2.9%) | 18 (17%) | ||

| Human environmental science | 33 (11.9%) | 16 (15%) | 17 (10%) | 2 (5.7%) | 5 (4.7%) | ||

| Nursing | 43 (15.5%) | 15 (14%) | 28 (16.5%) | 9 (25.7%) | 20 (18.9%) | ||

| Social work | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Undecided | 9 (3.2%) | 4 (3.7%) | 5 (2.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 4 (3.8%) | ||

| Credit hours | 29.33 ± 30.85 | 31.28 ± 30.05 | 28.08 ± 31.38 | 0.404 | 19.94 ± 28.61 | 27.88 ± 34.75 | 0.225 |

| MEQ, score | 45.03 ± 8.43 | 42.42 ± 8.83 | 46.68 ± 7.75 | 0.000 | 43.51 ± 10.51 | 46.97 ± 7.14 | 0.030 |

Numbers in the table are mean with standard deviations or percentages

Table 2.

Sleep and academic performance variables of college students at risk, not at risk, and with and without a sleep disorder

| SLEEP-50 (n = 277) | Clinical interview (n = 141) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Full sample (n = 277) | at risk (n = 107) | Not at risk (n = 170) | p-value | sleep disorder (n = 35) | No sleep disorder (n = 106) | p-value |

| Academic performance variables | |||||||

| GPA | 3.33 (3.00, 3.70) | 3.24 (3.00, 3.62) | 3.45 (2.80, 3.80) | 0.809 | 3.58 (3.08, 3.77) | 3.5 (3.22, 3.95) | 0.630 |

| Classes missed—oversleeping | 0 (0, 2.00) | 1.00 (0, 3.00) | 0 (0, 1.00) | 0.001 | 0 (0, .75) | 0 (0, 1.00) | 0.818 |

| Classes missed—illness | 0 (0, 1.00) | 1.00 (0, 2.00) | 0 (0, 1.00) | 0.022 | 1 (0, 2.00) | 0 (0, 1.00) | 0.005 |

| Falling asleep in class | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 1.00) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.016 | 0 (0, .75) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.977 |

| Sick each semester | 1 (1, 2.25) | 2.00 (1.00, 4.00) | 1 (1.00, 2.00) | 0.003 | 2 (1.00, 4.00) | 1 (1.00, 2.00) | 0.004 |

| CSD-M sleep variables | |||||||

| TIB | 497.9 (460.2, 541.3) | 496.6 (455, 534.3) | 500.9 (461.9, 544.8) | 0.595 | 479.6 (443, 547.5) | 471.7 (443.2, 502.5) | 0.646 |

| TST | 451.8 (414.5, 491.5) | 430.6 (398.4, 484.6) | 463.8 (423.9, 503.3) | 0.009 | 419 (387.1, 491.1) | 435.1 (402.6, 470.2) | 0.173 |

| SE | 91.7 (87.4, 94.6) | 90.2 (84.6, 93) | 93.2 (89.3, 95.6) | < 0.01 | 91.7 (84.3, 94.6) | 93.7 (89.4, 95.7) | 0.002 |

| SOL | 18.1 (10.8, 26.3) | 20.1 (13.2, 35) | 16.3 (9.75, 24.1) | 0.005 | 17.6 (12.3, 33.4) | 14.9 (9.23, 19.1) | 0.005 |

| TWT | 9.4 (3.73, 16.2) | 10.7 (5.4, 19.3) | 8.1 (2.9, 13.8) | 0.013 | 6.61 (4.02, 17.9) | 5 (2.14, 11.7) | 0.244 |

| NAP | 28 (2.52, 73.5) | 40 (1.8, 80) | 22 (2.79, 72.5) | 0.073 | 10.3 (.21, 34.1) | 10.4 (3.3, 23.2) | 0.026 |

| SQR | 3.67 (3.27, 3.93) | 3.54 (3.2, 3.9) | 3.72 (3.38, 4.13) | < 0.01 | 3.32 (2.83, 3.9) | 3.77 (3.42, 4.14) | 0.006 |

| WASO | 13.1 (5.82, 23.3) | 17.3 (9.8, 27.2) | 10 (4.63, 21) | 0.002 | 11.6 (8, 26.2) | 6.2 (3.53, 14.7) | < 0.01 |

Numbers in the table are median with IQR

GPA grade point average, CSD-M consensus sleep diary for morning, TIB time in bed, TST total sleep time, SE sleep efficiency, SOL sleep onset latency, TWT total wake time, NAP time spent napping, SQR sleep quality rating, WASO wake after sleep onset

Prevalence of sleep complaints and disorders

Sleep complaints reported on the SLEEP-50 were prevalent among this sample of college students, as 74.7% reported at least one significant sleep complaint and 53.1% of students reported significant sleep complaints consistent with two or more sleep disorders combined with impairments in daytime functioning. Sleep complaints reported on the SLEEP-50 are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Based on the SLEEP-50, 38.6% (107/277) of students were at risk for a sleep disorder. The prevalence of students in each SLEEP-50 sleep disorder category are reported in Table 3. Upon completion of the clinical interview, 24.8% (35/141) of students with a significant sleep complaint on the SLEEP-50 met diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder. The prevalence for specific sleep disorders, as assessed through the combination of self-report questionnaires and the clinical interview are reported in Table 4.

Table 3.

Prevalence of sleep disorder categories on the SLEEP-50

| Prevalence n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 17 (6.1%) |

| Insomnia | 54 (19.5%) |

| Restless legs syndrome | 37 (13.4%) |

| Narcolepsy | 71 (25.6%) |

| Sleepwalking | 3 (1.1%) |

| Nightmare disorder | 77 (27.8%) |

| Circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorder | 19 (6.9%) |

These numbers do not sum to 107 because multiple students met criteria for more than one sleep disorder based on the SLEEP-50

Table 4.

Prevalence of sleep disorders among college students based on the clinical interview

| Prevalence n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Obstructive sleep apnea* | 0 (0%) |

| Insomnia | 8 (2.9%) |

| Restless legs syndrome | 2 (0.7%) |

| Narcolepsy* | 1 (0.4%) |

| Parasomnia | 0 (0%) |

| Nightmare disorder | 0 (0%) |

| Delayed sleep–wake phase disorder | 15 (5.4%) |

| Behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome | 13 (4.7%) |

These numbers do not sum to 35 because 4 students met criteria for more than one sleep disorder.

*Unable to accurately diagnosis these possible sleep disorders due to polysomnography not being conducted during the study. One student at risk for obstructive sleep apnea on the SLEEP-50 reported completing polysomnography and that it was negative for obstructive sleep apnea

Risk for a sleep disorder and academic performance and functioning

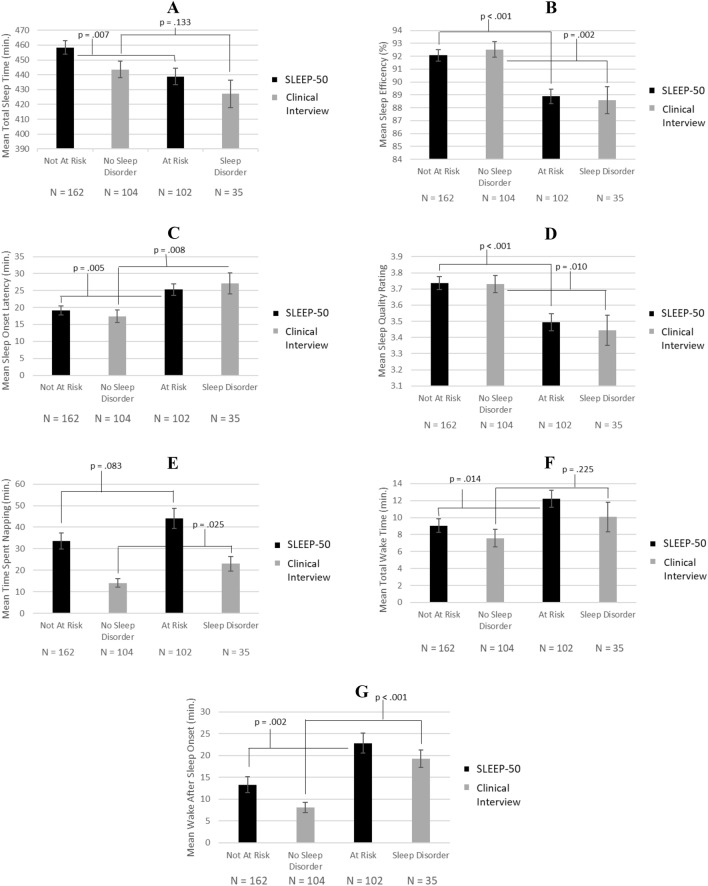

Students who were at risk reported worse sleep than those not at risk for a sleep disorder, Wilks’ Λ = 0.900, F = 3.463, p < 0.001. Compared to students not at risk, students at risk reported a lower TST (F = 7.368; p = 0.007), a lower SE (F = 19.087; p < 0.001), a higher SOL (F = 8.099; p = 0.005), a higher TWT (F = 6.125; p = 0.014), a lower SQR (F = 13.446; p < 0.001), and a higher mean WASO (F = 10.170; p = 0.002) (Fig. 2). Mean TIB and time spent napping were not significantly different between students at risk and not at risk.

Fig. 2.

Sleep diary variables among students at risk and not at risk for a sleep disorder and with and without sleep disorders. The above figure presents mean total sleep time (panel A), mean sleep efficiency (panel B), mean sleep onset latency (panel C), mean sleep quality rating (panel D), mean time spent napping (panel E), mean total wake time (panel F), and mean wake after sleep onset (panel G) for students at risk and not at risk for a sleep disorder based on the SLEEP-50 (black bars) and students with and without a sleep disorder based on the clinical interview (gray bars). Sleep quality rating (Graph D) ranges from 1 = very poor to 5 = very good

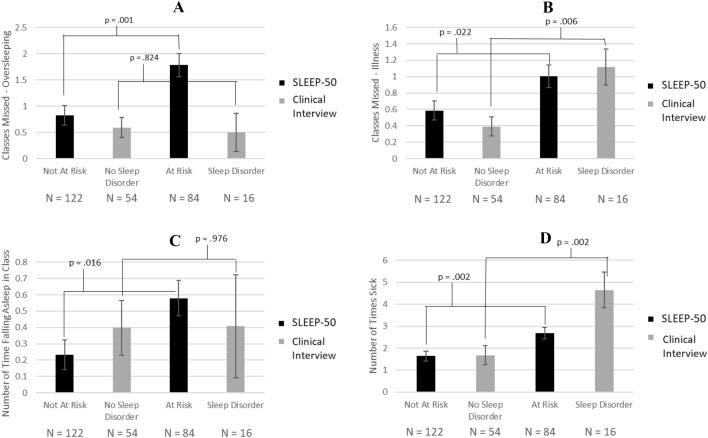

Compared to students not at risk, students who were at risk reported overall worse academic performance and functioning, Wilks’ Λ = 0.886, F = 5.060, p < 0.001. Students who were at risk for a sleep disorder reported more classes missed per month due to oversleeping (F = 11.153, p = 0.001), more classes missed per month due to illness (F = 5.348, p = 0.022), more times falling asleep in class per week (F = 5.952, p = 0.016), and more times sick each semester (F = 9.429, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3). GPA was not significantly different between students at risk and not at risk for a sleep disorder.

Fig. 3.

Academic performance among students at risk and not at risk for a sleep disorder and with and without sleep disorders. The above figure presents number of classes missed due to oversleeping (panel A), number of classes missed due to illness (panel B), number of times falling asleep in class (panel C), and number of times sick (panel D) for students at risk and not at risk for a sleep disorder based on the SLEEP-50 (black bars) and students with and without a sleep disorder based on the clinical interview (gray bars)

Sleep disorders and academic performance and functioning

Overall, students who met criteria for a sleep disorder reported worse sleep than those who did not meet criteria for a sleep disorder, Wilks’ Λ = 0.815, F = 3.498, p = 0.001. Individuals who met criteria for a sleep disorder reported a lower mean SE (F = 10.403; p = 0.002), a higher SOL (F = 7.285; p = 0.008), a higher mean time spent napping (F = 5.168; p = 0.025), a lower SQR (F = 6.874; p = 0.010), and a higher mean WASO (F = 22.896; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Mean TIB, TST, and TWT were not significantly different between students with a sleep disorder and those without.

There was a statistically significant difference in overall academic performance and functioning between college students who met criteria for a sleep disorder and those who did not (Wilks’ Λ = 0.787, F = 3.250, p = 0.012). Students who met criteria for a sleep disorder reported more classes missed per month due to illness (F = 8.150, p = 0.006) and more times sick each semester (F = 10.071; p = 0.002; Fig. 3). There was not a statistically significant difference in GPA, classed missed per month due to oversleeping, and the number of times falling asleep in class per week between students who met criteria for a sleep disorder and those who did not.

Discussion

In the current study, over half of the sample of college students reported significant sleep complaints on the SLEEP-50. The most common sleep complaints included difficulties falling asleep, getting insufficient sleep, and variable bedtimes. Following a semi-structured clinical interview, DSWPD (5.4%) was the most common sleep disorder followed by Behaviorally induced Insufficient sleep syndrome (BIISS) (4.7%) and insomnia (2.9%). Students who were at risk and who had a sleep disorder both reported a greater number of classes missed per month due to and number of times sick each semester compared with their respective peers not at risk or without a sleep disorder. However, neither students at risk nor those who had a sleep disorder reported a lower GPA compared with students not at risk or without a sleep disorder. Overall, these results suggest that the presence of sleep complaints and/or disorders are associated with worse academic functioning but not performance.

Sleep complaints were common among this sample of college students, a finding that is consistent with previous studies [1–4, 8, 30]. The most frequently observed sleep complaints in our sample were difficulties falling asleep, insufficient sleep, variable bedtimes, waking up too early, and trouble going back to sleep. Several of these sleep complaints (i.e., difficulties falling asleep and insufficient sleep) are commonly associated with DSWPD, suggesting that the most frequently reported sleep complaints in both the current study, as well as previous studies, may indicate a high prevalence of DSWPD among college students. However, clinical interviews are rarely included in research on college student sleep, making it difficult to distinguish between DSWPD and insomnia. Following the completion of the clinical interview, DSWPD was the most prevalent sleep disorder in our sample followed by BIISS and insomnia. Other sleep disorders, particularly those with increasing prevalence associated with increasing age were less prevalent in this sample of college students.

The lack of an association between students at risk for a sleep disorder or meeting criteria for a sleep disorder and GPA is consistent with a study conducted by Taylor et al. [18] and may suggest that the types of sleep disorders observed in students (e.g., DSWPD or BIISS) may not negatively impact GPA. The current study adds to existing literature by examining both academic performance (i.e., GPA) and functioning (e.g., missing class due to oversleeping/illness and falling asleep in class). The current study found that students at risk for a sleep disorder and those who meet criteria for a sleep disorder are associated with specific elements of academic functioning but not necessarily academic performance. Given that a majority of the sample was comprised of freshmen/women, it is also possible that not enough time had passed for GPA to be negatively impacted. Indeed, in a longitudinal study conducted by Chen and Chen, baseline sleep deprivation predicted future GPA [15]. Lastly, the similar trends in the association between sleep disorders, defined by the SLEEP-50 versus a clinical interview, and academic performance and functioning suggests that screening tools, such as the SLEEP-50, may be sufficient when examining outcomes associated with the presence of any sleep disorder. However, when examining a specific sleep disorder, the change in classification from students at risk to meeting diagnostic criteria suggests a clinical interview may be necessary to make differential diagnoses and distinguish between sleep disorders such as DSWPD versus Insomnia.

The current study has several strengths including the use of multiple types of sleep questionnaires assessing different aspects of sleep, 2-weeks of sleep diaries, and a semi-structured clinical interview to improve diagnostic accuracy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a clinical interview when examining college student sleep and its association with academic performance and functioning. The current study also examined both academic performance (i.e., GPA) and functioning (e.g., classes missed per month due to oversleeping, classes missed per month due to illness, frequency of falling asleep in classes per week, and how often the student was sick each semester). The results of this study should be taken in the context of several limitations. This study relied on self-report data, which is subject to a number of biases and potential inflation of sleep complaints [31]. It is hoped that inclusion of a clinical interview may have mitigated limitations imposed using self-report data collected online. Also, it should be noted that sleep disorders requiring PSG and/or MSLT (e.g., OSA, PLMD, and narcolepsy) could not be completely assessed beyond the clinical interview. However, these disorders were not anticipated to be highly prevalent in college students. This study is both descriptive and correlational in nature and, therefore, causal associations between sleep and academic performance and functioning may not be inferred. Future research may wish to incorporate research methodologies (i.e., longitudinal data collection and analyses throughout students’ undergraduate careers) that would allow for causal mechanisms between sleep and academic performance and functioning to be uncovered. Furthermore, a longitudinal analysis, as per-formed by Chen and Chen [20], would allow for interesting analyses of the development of sleep habits and academic performance (i.e., GPA) across time, as well as a potential impact on GPA later in students’ college careers. This sample is comprised of college students in a Department of Psychology Subject Pool and is overrepresented by females and younger students in their first year of college. We adjusted for age, sex, and race in our statistical models to account for this limitation. Lastly, although the sample size for the clinical interview (n = 143) was sufficient to provide a preliminary picture of sleep complaints and disorders in college students, while also allowing for comparing academic performance and functioning between students who did and did not meet diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder, the sample size was not sufficient to compare individual sleep disorders.

Conclusions

The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to incorporate a semi-structured clinical interview to most accurately assess for sleep disorders and their association with academic performance and functioning across multiple domains. Sleep concerns were common in this sample of college students with DSWPD, BIISS, and insomnia being the most common sleep disorders. Students at risk for and meeting diagnostic criteria for a sleep disorder reported a greater number of classes missed per month due to oversleeping and times sick each semester but not lower GPA. Assessment and treatment of sleep disorders early in college students’ career may be important for optimal academic functioning.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, under award number R01HL147603, and the American Heart Association, under award number 19CDA34660139. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

Clinical interview based on the international classification of sleep disorders, 2nd edition

Insomnia

1. Do you have trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, or both?

2. Do you have trouble waking up too early?

3. How long have you experienced difficulties sleeping?

4. How much time do you spend attempting to sleep? Do you feel this amount of time is sufficient?

5. If you have trouble falling asleep or staying asleep, how do you typically feel the next morning, day, and evening?

6. Do you worry about being able to sleep or how you might feel/perform the day after a poor night’s sleep?

Sleep-related breathing disorders

1. Do you wake yourself up snoring or gasping for breath?

2. Have others told you that you snore at night? If so, how loudly?

3. Have others told you that you have pauses in your breathing at night?

4. Do you wake up in the morning with a headache or dry mouth?

5. Do you feel excessive fatigue and/or sleepiness during the day?

6. Have you had a sleep study? If so, what was the result? 70

Hypersomnia of central origin

1. Do you frequently experience excessive daytime sleepiness? If so, how long have you experienced these symptoms?

2. How much time do you spend attempting to sleep? Do you feel this amount of time is sufficient?

3. If insufficient sleep, how much time do you prefer to spend sleep? Specifically, if it were not for school (e.g., weekends or vacation), what would be your preferred bedtime, waketime, and total amount of sleep needed to feel rested?

4. What is the quality of your sleep?

5. Do you experience sleep paralysis (explain phenomenon)? If so, how often and how severe?

6. Do you experience hypnogogic/hypnopompic hallucinations (explain phenomenon)? If so, how often and how severe?

7. Do you experience cataplexy (explain phenomenon)?

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders

1. Do you tend to sleep at your preferred sleep time? If not, what would be your preferred bedtime and waketime?

2. If you go to bed earlier than you prefer, do you find it difficult to fall asleep?

3. Do you also find it difficult to wake up in the mornings, particularly if you have an early class?

Parasomnias

1. Do experience any unusual behaviors during sleep (e.g., sleepwalking, sleep talking, etc.)?

2. If so, describe the event and when it typically occurs.

3. When did these behaviors begin and how long have you experienced them?

Sleep-related movement disorders

1. Do you experience any unpleasant sensations (e.g., a “creepy crawly” sensation) in your legs, particularly when you lie down to go to sleep?

2. If so, please describe the sensation, when it occurs, and how often you experience these sensations.

3. Do you feel the urge to move your legs when you are experiencing these sensations? If so, does movement alleviate the sensations?

Environmental sleep disorder

1. If you experience sleep complaints, are they primarily due to an environmental factor (e.g., dorm noise) that disturbs your sleep?

Funding

The authors were the only supporters and sponsors of the study. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, R01HL147603, S. Justin Thomas, American Heart Association, 19CDA34660139, S. Justin Thomas.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the IRB and the Department of Psychology Research Subject Pool at the University of Alabama. All ethical standards were observed.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained online.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Buboltz WC, Jr, Brown F, Soper B. Sleep habits and patterns of college students: a preliminary study. J Am Coll Health. 2001;50(3):131–135. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lack LC. Delayed sleep and sleep loss in university students. J Am Coll Health. 1986;35(3):105–110. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1986.9938970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, Prichard JR. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(2):124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forquer LM, Camden AE, Gabriau KM, Johnson CM. Sleep patterns of college students at a public university. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56(5):563–565. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.563-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker SP, Jarrett MA, Luebbe AM, Garner AA, Burns GL, Kofler MJ. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health. 2018;4(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becerra MB, Bol BS, Granados R, Hassija C. Sleepless in school: the role of social determinants of sleep health among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2020;68(2):185–191. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1538148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown FC, Soper B, Buboltz Jr WC. Prevalence of delayed sleep phase syndrome in university students. Coll Stud J. 2001;35(3):472. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor DJ, Gardner CE, Bramoweth AD, Williams JM, Roane BM, Grieser EA, Tatum JI. Insomnia and mental health in college students. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9(2):107–116. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.557992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaultney JF. The prevalence of sleep disorders in college students: impact on academic performance. J Am Coll Health. 2010;59(2):91–97. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.483708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly WE, Kelly KE, Clanton RC. The relationship between sleep length and grade-point average among college students. Coll Stud J. 2001;35(1):84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilcher JJ, Walters AS. How sleep deprivation affects psychological variables related to college students' cognitive performance. J Am Coll Health. 1997;46(3):121–126. doi: 10.1080/07448489709595597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor DJ, McFatter RM. Cognitive performance after sleep deprivation: does personality make a difference? Personal Individ Differ. 2003;34(7):1179–1193. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00108-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orzech KM, Salafsky DB, Hamilton LA. The state of sleep among college students at a large public university. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(7):612–619. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.520051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asarnow LD, McGlinchey E, Harvey AG. The effects of bedtime and sleep duration on academic and emotional outcomes in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(3):350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen WL, Chen JH. Consequences of inadequate sleep during the college years: sleep deprivation, grade point average, and college graduation. Prev Med. 2019;124:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann ME, Prichard JR. Calculating the contribution of sleep problems to undergraduates’ academic success. Sleep Health. 2018;4(5):463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piro RS, Alhakem SSM, Azzez SS, Abdulah DM. Prevalence of sleep disorders and their impact on academic performance in medical students/University of Duhok. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2018;16:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s41105-017-0134-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD, Grieser EA, Tatum JI, Roane BM. Epidemiology of insomnia in college students: relationship with mental health, quality of life, and substance use difficulties. Behav Ther. 2013;44(3):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benitez A, Gunstad J. Poor sleep quality diminishes cognitive functioning independent of depression and anxiety in healthy young adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26(2):214–223. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.658439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medeiros AD, Mendes DB, Lima PF, Araujo JF. The relationships between sleep-wake cycle and academic performance in medical students. Biol Rhythm Res. 2001;32(2):263–270. doi: 10.1076/brhm.32.2.263.1359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright KP, Jr, Hull JT, Hughes RJ, Ronda JM, Czeisler CA. Sleep and wakefulness out of phase with internal biological time impairs learning in humans. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18(4):508–521. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas SJ. A survey of sleep disorders in college students: a study of prevalence and outcomes. Dissertation, University of Alabama, Institutional Repository; 2014.

- 23.Carney CE, Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Krystal AD, Lichstein KL, Morin CM. The consensus sleep diary: standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep. 2012;35(2):287–302. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Lichstein KL, Morin CM. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(9):1155–1173. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman GL, Hovland CI. Diurnal variations in performance and related physiological processes. Psychol Bull. 1934;31(10):777–799. doi: 10.1037/h0071917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleitman N. Sleep and wakefulness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horne JA, Ostberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4(2):97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spoormaker VI, Verbeek I, van den Bout J, Klip EC. Initial validation of the SLEEP-50 questionnaire. Behav Sleep Med. 2005;3(4):227–246. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0304_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AAOS Medicine . The international classification of sleep disorders, second edition ICSD-2. Darien: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taher YA, Samud AM, Ratimy AH, Seabe AM. Sleep complaints and daytime sleepiness among pharmaceutical students in Tripoli. Libyan J Med. 2012;7:18930. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v7i0.18930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorin AA, S AA. Recall biases and cognitive errors in retrospective selfreports: a call for momentary assessments. Handb Health Psychol. 2001;23:405–13. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.