Abstract

Purpose

It is often assumed sleep duration has decreased and sleep schedules have delayed over the last decades, as society modernized. We aimed to investigate changes in the sleep patterns of school-age children over time.

Methods

We compared the sleep timings, durations, and disturbances of primary school-age children in 1995 and roughly two decades later, in 2016. Data from 666 children attending the 3rd and 4th grades of basic education were combined from two different cross-sectional school-based studies conducted within the same educational region of mainland Portugal using the same parent-report questionnaire (Children’s Sleep–wake Patterns Questionnaire).

Results

Mean sleep duration did not differ significantly between the two time points (schooldays: t = .118, p = .906; free days: t = 1.310, p = .191), albeit the percentage of children sleeping the recommended number of hours decreased significantly in 2016 when compared to 1995 (schooldays: χ2 = 4.406, p = .036; free days: χ2 = 16.859, p < .001). Wake-times advanced on free days in 2016. Difficulties on settling to sleep alone and returning to sleep were more prevalent in 2016, as well as fearing the dark and needing lights on or parent’s presence to fall asleep.

Conclusions

Sleep onset-related disturbances appear to have increased from 1995 to 2016. One possible explanation for this increase might be the change in parental practices preventing children from learning to fall asleep autonomously.

Keywords: Children, Sleep timing, Sleep duration, Sleep–wake behaviors, Sleep disturbances

Introduction

Despite the spreading awareness of the consequences of insufficient sleep on children’s health and well-being, estimates suggest 15–75% of school-age children are not getting enough sleep [1] and there is evidence alerting for a secular trend of decline in children’s sleep duration. A comprehensive review of worldwide literature [2] reported the total sleep duration of children and adolescents has declined by an average of 0.75 nightly per year over the last century and by 14 min per night since 1970. A similar trend was found by De Ruiter et al. [3], who reported a sleep duration decrement of 20 min over the last two decades in children aged 2–14 years old.

The apparent decline in children’s sleep duration is widely attributed to the growing use of technology and modern lifestyle [4, 5]. Studies have shown chronic exposure to light during evening hours and late bedtimes during early childhood may interact to promote the development of a late sleep phenotype [6]. Screen time and exposure to light emitted from electronic screens near bedtime have too been associated with prolonged sleep onset and shorter sleep duration in children and adolescents [7, 8]. However, Leech [9] found no evidence that the growing of screen time occurred at the expense of sleep duration, noting rather an increase of the average sleep duration in Canadians aged 15 years and older between 1998 and 2010, a period of rapid advances in computer technology, video gaming and social media. There is also evidence suggesting the sleep duration of adults has not been declining [10–12].

Early school start-times have also been advocated as factors that might underlie disturbances in sleep patterns or duration. The conflict between sleep–wake patterns and social demands arises during school-age years, as school schedules become one of the main zeitgebers of children’s sleep–wake patterns and start to influence the wake-times and sleep duration of school-age children [13]. This conflict may prompt the development of sleep disturbances among school-age children.

Considering the detrimental effects of sleep disturbances among school-age children and the conflicting evidence around secular trends, we deemed crucial to understand the changes in children’s sleep and to unriddle the factors underling such changes. In this paper, we aim to examine changes in sleep duration, sleep timing and sleep disturbances of elementary school-age children by comparing two time marks: 1995, prior to the emergence of social media and technology device use, and 2016. Specifically, we aimed to explore: (1) changes in sleep timings by analyzing bedtimes, wake-times, social jetlag, and midpoints of sleep; (2) changes in sleep duration by comparing night sleep durations, sleep need and sleep restriction–extension patterns; (3) changes in sleep–wake behaviors and difficulties, namely bedtime-related disturbances (e.g., having trouble falling asleep without parents’ presence, a comforting habit, or lights on), nighttime disturbances (difficulties going back to sleep, bruxism, and parasomnias, including sleepwalking, night terrors, somniloquy and enuresis), daytime disturbances (daytime sleepiness, irritability, and fatigue).

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

We combined the samples of two cross-sectional studies with school-age children within the same educational region of continental Portugal (Center region) using the same parental questionnaire. The 1995 sub-sample was drawn from a study (conducted April–July 1995 and reported in 1997) that included 988 children attending the first cycle of basic education in Coimbra [14]. The 2016 sub-sample was drawn from a study, conducted February–June 2016, that involved 376 children attending first and second cycles of basic education in Castelo Branco [15]. Parental consent was obtained for both studies from where data were drawn. The 1995 study was reviewed and approved by the Regional Director of Education, and the 2016 study was accepted by the Portuguese Ministry of Education (MIME-DGE permission—reference number 0516600001), as well as school administrators. Only comparable data, hence, only children attending 3rd and 4th school-grade levels of basic education from both samples were included in the current study.

The final sample of the present study included 666 children attending 3rd (49.85%) and 4th grades of basic education (51.65% girls). It was composed of two convenience subsamples in which 421 children were assessed in 1995 (8.99 ± 0.776 years old, 51.07% girls, 52.97% 3rd graders) and 245 children were assessed in 2016 (8.99 ± 0.760 years old, 52.65% girls, 44.49% 3rd graders). There were no statistically significant differences in age [t(664) = 0.006, p = 0.995] for the two subsamples.

Measures

All children were assessed using the Children’s Sleep–Wake Patterns Questionnaire (PSVC), a Portuguese parent-report instrument with well-established validity and stability [16–18] measuring children’s sleep–wake timings, duration, habits, and disturbances in the preceding 6 months. In the PSVC, wake-time and bedtime, as well as sleep duration on both school and free days, are assessed through open-ended questions. Sleep difficulties are assessed through 19 Likert-type items (scored from 1 = never to 4 = always) organized into 3 sections: bedtime disturbances (settling to sleep alone at their own bed, falling asleep on parents bed, needing parental presence to fall asleep, needing comforting habits to sleep, needing lights on to fall asleep, willingness to go to bed [“Is your child willing to go to bed at bedtime?”], and bedtime resistance [“Does your child refuse to go to bed at bedtime – cries, screams, makes excuses?”]); nighttime behaviors and disturbances (enuresis, nightmares, sleepwalking, somniloquy, night terrors, bruxism, loud snoring, ability to go back to sleep alone after night awakenings, fear of sleeping in the dark); and sleep-related daytime difficulties (sleepiness, irritability and fatigue). Parents/caregivers are also asked to select the main factor influencing their child’s bedtime (to get enough hours of sleep for the following day activities, family routine, siblings’ bedtime, is sleepy, ends TV program, other) and wake-time (were woken up by parents/caretakers, alarm clock, by themselves, noise, needs to use the toiled, other). Six previously established factors for the PSVC [17, 18] were considered: parents help to sleep; parasomnias; sleeping difficulties; afraid of dark; sleep limit setting; daytime sleep consequences. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the current sample ranged from 0.74 (Factor 1) to 0.84 (Factor 4).

Based on sleep–wake timings and duration, other sleep variables were computed as follows. Sleep need was calculated through the weighted average: ([Night sleep duration [NSD] on schooldays (SC) × 5] + [NSD on free days (FR) × 2])/7. Midpoint of sleep (MS) was calculated by approximation using bedtime, as sleep onset was not explored (bedtime + NSD)/2, for both school (MSC) and free days (MSF). Based on the obtained MSF, the corrected midpoint of sleep (MSFsc) was calculated using the formula suggested by Roenneberg et al. [19]: MSF [0.5 × (NSD on free days – sleep need)]. Social jet lag (SJL) was operationalized according to Roenneberg’s (SJL_R [19]) and Jankowski’s (SJLsc [20]) formulas. Sleep restriction-extension pattern was defined as the difference between NSD on school and free days.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the 22.0 version of IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Corpo., Armonk, NY). Variables with normal distributions were presented as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Variables were considered close to normally distributed if skewness and kurtosis were under 2 and 7, respectively [21]. Homogeneity of variance was tested by the Levene method. Student’s t tests and subsequently ANCOVAS controlling for age and sex (age inserted as a covariate) were performed to compare continuous sleep variables between 1995 and 2016. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables. To determine the prevalence of sleep disturbances, frequency responses were grouped (“always”/“often” or “never”/”few times” according to the scoring direction of each item). For sleep disturbances showing statistically significant differences between the two time marks in the overall sample, direct logistic regressions were performed to assess the impact of year, age, and sex. For willingness to go to sleep, along with year, age, and sex, MSFsc was included in the model to rule out the influence of chronotype. Finally, categorical variables were aggregated following previously established factors for this questionnaire [17, 18], and ANCOVAS with age and sex as covariates were performed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Motives for bed and wake-times

Parents were asked to elect the main factor influencing their child’s bedtime and wake-time. There were statistically significant differences between 1995 and 2016 concerning the motives for bed ([χ2(4, n = 645) = 39.798, p < 0.001] and wake-times ([χ2(2, n = 650) = 18.338, p < 0.001]. In 2016, family routine determined most children’s bedtime (43.21%), while in 1995 family routine only motivated bedtime for 22.82% of children. In 1995, most children were reported going to bed to get enough hours of sleep for the following day activities (52.91%). Bedtime was determined by children’s sleepiness in 16.99% of cases in 1995 and only 6.58% in 2016. Most children were woken up by their parents/caregivers or family members in both 1995 and 2016.

Sleep timings and durations

Table 1 comprises detailed comparison results. ANCOVAs by year controlling for age and sex showed no main effects for year, sex or age and no interaction effects of year*sex, year*age nor age*sex for bedtime and midpoint of sleep both on school and free days, nor for social jetlag or corrected midpoint of sleep. There was an interaction effect of year and age on wake-time on free days [F(1, 655) = 6.001, p = 0.015]. In 1995, wake-times gradually delayed as children grew older. The reverse occurred in 2016: wake-times on free days advanced gradually as children got older. On schooldays, we found interaction effects of age and sex for wake-times [F(1, 659) = 7.194, p = 0.008]. In 1995, girls’ wake-times on schooldays gradually delayed as they got older, while in 2016 girls’ wake-times on schooldays gradually advanced with age. On schooldays, boys’ wake-times gradually advanced as they get older in both 1995 and 2016.

Table 1.

Comparison of sleep parameters (1995–2016)

| Sleep parameter | 1995 | 2016 | t-test | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Night sleep duration | Schooldays | 9h35m ± 50 m | 9h35m ± 37 m | t(590.424) = .118 | .906 | .010 |

| Free days | 10h18m ± 59 m | 10h11m ± 1h01m | t(645) = 1.310 | .191 | .103 | |

| Wake-time | Schooldays | 7:52 ± 51 m | 7:39 ± 30 m | t(657.468) = 4.115 | < .001 | .321 |

| Free days | 9:34 ± 1 h | 8:56 ± 1 h | t(654) = 7.833 | < .001 | .613 | |

| Bedtime | Schooldays | 21:57 ± 35 m | 21:43 ± 31 m | t(660) = 5.292 | < .001 | .412 |

| Free days | 22:58 ± 41 m | 22:25 ± 42 m | t(658) = 9.975 | < .001 | .778 | |

| Midpoint of sleep | Schooldays | 2:46 ± 38 m | 2:31 ± 26 m | t(618.513) = 5.740 | < .001 | .462 |

| Free days | 4:07 ± 50 m | 3:31 ± 42 m | t(548.027) = 9.855 | < .001 | .842 | |

| Corrected midpoint of sleep | 3:53 ± 43 m | 3:18 ± 39 m | t(638) = 9.838 | < .001 | .779 | |

| Sleep need | 9h47m ± 45 m | 9h45m ± 36 m | t(562.041) = .705 | .481 | .060 | |

| Social jet lag (Roenneberg’s formula) | 1:22 ± 46 m | 1:00 ± 36 m | t(568.860) = 6.572 | < .001 | .551 | |

| Social jet lag (Jankowski’s formula) | 1:05 ± 37 m | 00:37 ± 33 m | t(127) = 4.055 | < .001 | .720 | |

| Sleep restriction-extension pattern | 42 m ± 58 m | 35 m ± 1 h | t(641) = 1.421 | .156 | .112 | |

Classifying sleep durations according to standard sleep recommendations

The mean night sleep duration on schooldays was 9 h 35 min in both 1995 and 2016. On free days, mean night sleep duration was 10 h 18 min in 1995 and 10 h 11 min in 2016, meeting the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) recommendations of 9–11 h for school-age children [22]. However, the percentage of children sleeping the recommended number of hours decreased significantly from 1995 to 2016 on schooldays [χ2(1, n = 647) = 4.406, p = 0.036] and free days [χ2(1, n = 647) = 16.859, p < 0.001] (Table 2). Sleep need did not differ between the two time points [t(562.041) = 0.705, p = 0.481].

Table 2.

Classification of sleep durations according to sleep recommendations of the National Sleep Foundation and distribution of children in the 1995 and 2016 samples

| Night sleep duration | Study | < 7 h Not recommended |

7-9 h May be appropriate |

9-11 h Recommended |

11-12 h May be appropriate |

> 12 h Not recommended |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schooldays | 1995 (n = 417) | – | 42 (10.07%) | 363 (87.05%) | 10 (2.40%) | 2 (0.48%) |

| 2016 (n = 230) | – | 42 (18.26%) | 186 (80.87%) | 2 (0.87%) | – | |

| Chi-square (P) | 8.799, p = .003 | 4.406, p = .036 | 1.903, p = .168 | |||

| Free days | 1995 (n = 416) | – | 10 (2.40%) | 346 (83.17%) | 51 (12.26%) | 9 (2.16%) |

| 2016 (n = 231) | 1 (0.43%) | 24 (10.39%) | 160 (69.26%) | 40 (17.32%) | 6 (2.60%) | |

| Chi-square | 19.024, p < .001 | 16.859, p < .001 | 3.142, p = .076 |

The percentage of children sleeping this recommended number of hours on schooldays decreased from 87.05% in 1995 to 80.87% in 2016. The percentage of children sleeping less than the recommended number of hours on schooldays increased from 1995 (10.07%) to 2016 (18.26%)

Sleep disturbances

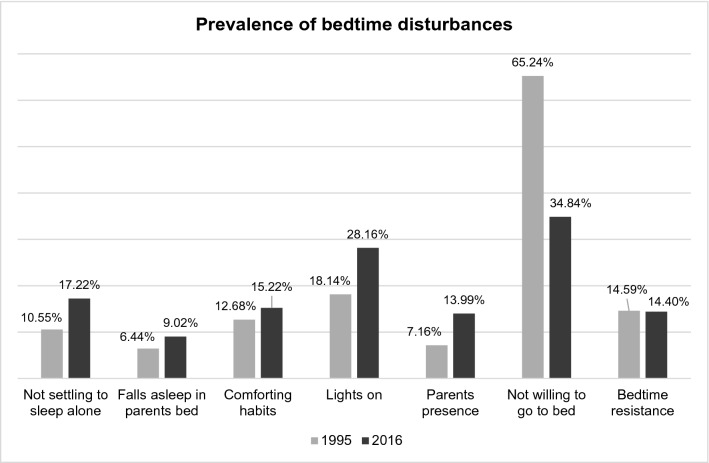

More children needed a comforting object [χ2(3, n = 660) = 17.484, p = 0.001, phi = 0.163], light [χ2(3, n = 663) = 25.077, p < 0.001, phi = 0.194] and their parents presence [χ2(3, n = 661) = 15.050, p = 0.002, phi = 0.151] to fall asleep in 2016 when compared to 1995. In 2016, more children were willing to go to bed [χ2(3, n = 663) = 112.447, p < 0.001, phi = 0.412] and less children fell asleep in their own bed [χ2(3, n = 662) = 11.114, p = 0.011, phi = 0.130]. Figure 1 depicts the prevalence of sleep-onset and bedtime disturbances of in both 1995 and 2016.

Fig. 1.

Overall, children’s bedtime difficulties were more prevalent in 2016, including needing lights on to fall asleep [χ2 = 9.103, p = .003] and falling asleep in parents’ bed [χ2 = 1.491, p = .22], although the latter did not reach statistical significance. Albeit not reaching statistical significance, the prevalence of bedtime resistance [χ2 = .004, p = .947] was slightly higher in 1995

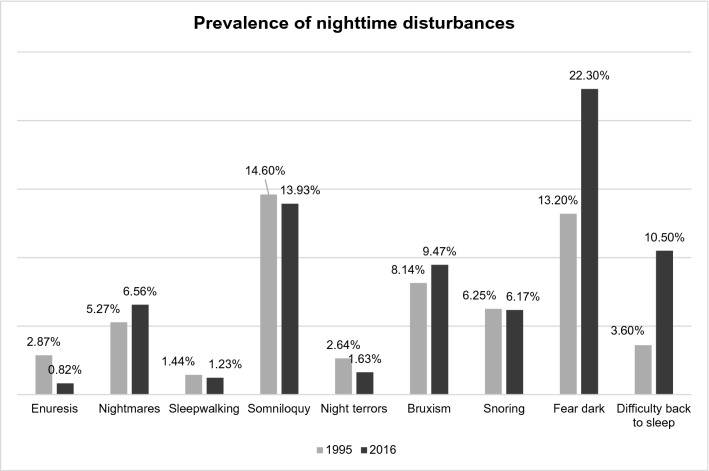

In 2016, more children experienced fear of the dark [χ2(3, n = 659) = 40.749, p < 0.001, phi = 0.249] when compared to 1995. Once awake, children experienced more difficulties going back to sleep [χ2(3, n = 658) = 535.735, p < 0.001, phi = 0.902] in 2016. Figure 2 shows the prevalence of snoring and parasomnias on both time marks. Somniloquy was the most prevalent parasomnia in both 1995 and 2016.

Fig. 2.

Except for experiencing fear of sleeping in the dark [χ2 = 9.319, p = .002] and difficulties going back to sleep after a night awakening [χ2 = 12.558, p < .001], there were no statistically significant differences between 1995 and 2016 concerning the prevalence of nighttime disturbances, including loud snoring [χ2 = .002, p = .968] and night terrors [χ2 = .054, p = .817]. Somniloquy [χ2 = .054, p = .816] was the most prevalent nighttime disturbance on both time marks, followed by bruxism [χ2 = .346, p = .557] and nightmares [χ2 = .477, p = .490]. In 1995, sleepwalking [χ2 = .048, p = .827] was the less prevalent parasomnia. The less prevalent parasomnia in 2016 was enuresis [χ2 = 3.131, p = .077]

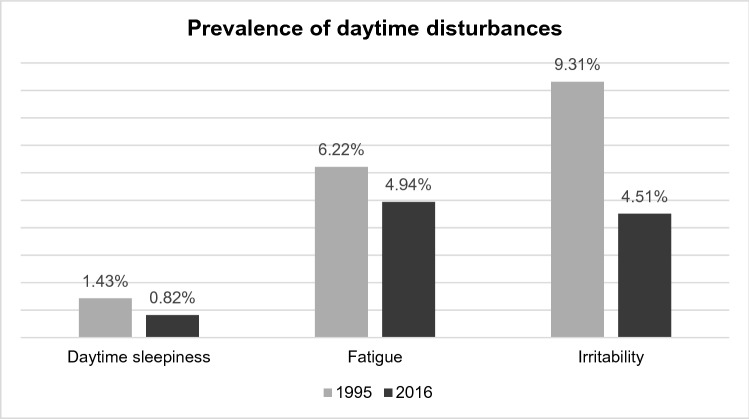

During the day, children experienced more irritability [χ2(3, n = 662) = 24.592, p < 0.001, phi = 0.193] in 2016 when compared to 1995. Figure 3 shows the prevalence of daytime disturbances related to sleep in 1995 and 2016.

Fig. 3.

Daytime sleepiness [χ2 = .478, p = .489], fatigue [χ2 = .466, p = .495] and irritability [χ2 = 24.592, p < .001] were slightly more prevalent in 1995 than 2016. The latter was the only daytime disturbance differing significantly between the two time points

Predictors of sleep disturbances

Sleep disturbances showing statistically significant differences in the overall sample were further explored with a regression model containing three independent variables (year, age, and sex; Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression models analyzing the relationship between sleep problems and year, age, and sex

| Variables | Odds Ratio (OR; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]) | p | Variables | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lights on | Comforting object | ||||

| Year | 1.789 (1.215–2.568) | .003 | Year | 1.232 (.780–1.946) | .371 |

| Age | .900 (.705–1.149) | .399 | Age | .665 (.490-.910) | .010 |

| Sex | .733 (.504–1.066) | .104 | Sex | .643 (.407–1.015) | .058 |

| Parental presence | Nightmares | ||||

| Year | 2.105 (1.256–3.549) | .005 | Year | 1.271 (.653–2.471) | .481 |

| Age | .886 (.629–1.248) | .489 | Age | .929 (.606–1.424) | .736 |

| Sex | .610 (.610–1.725) | .922 | Sex | 1.520 (.783–2.951) | .216 |

| Fear of the dark | Irritability | ||||

| Year | 1.858 (1.248–2.867) | .003 | Year | .458 (.230-.913) | .027 |

| Age | 1.016 (.775–1.331) | .910 | Age | 1.221 (.844–1.768) | .290 |

| Sex | .692 (.423–1.544) | .086 | Sex | .821 (.458–1.472) | .509 |

| Difficulty going back to sleep | Not willing to go to bed | ||||

| Year | 3.426 (1.632-.6.143) | .000 | Year | 3.709 (2.497–4.958) | .000 |

| Age | 1.232 (.798–1.900) | .346 | Age | 1.067 (.864–1.319) | .546 |

| Sex | .808 (.423–1.544) | .518 | Sex | .968 (.710–1.368) | .931 |

| Difficulty falling asleep alone | Corrected midpoint of sleep (MSFsc) | 1.003 (.746–2.071) | .170 | ||

| Year | 1.881 (1.191–3.005) | .007 | |||

| Age | .709 (.518-.971) | .032 | |||

| Sex | 1.109 (.699–1.761) | .661 | |||

Year made the only statistically significant contribution to the model of needing lights on to fall asleep [χ2(3, n = 666) = 12.328, p = 0.006], scoring an odds ratio (OR) of 1.789, meaning children assessed in 2016 were nearly 2 times more likely to need light to fall asleep than children assessed in 1995. Year was also the only statistically significant contribution to the models of needing parental presence [χ2(3, n = 661) = 8.373, p = 0.039; OR = 2.105], fear of the dark [χ2(3, n = 659) = 11.214, p = 0.011; OR = 1.858], and going back to sleep after waking up during the night [χ2(3, n = 658) = 551.692, p < 0.001; OR = 3.426]. Those odd ratio values indicate that in 2016 children were approximately two times more likely to need their caregivers’ presence, experienced fear of the dark nearly twice as much, and were three times less likely to go back to sleep alone than their counterparts assessed in 1995.

For falling asleep alone, year and age made statistically significant contributions [χ2(3, n = 662) = 11.923, p = 0.008], with year being the strongest predictor of children’s ability to settle to sleep alone in their own bed (OR = 1.881). Children assessed in 2016 were about twice as likely to have difficulties falling asleep alone. Only age was statistically significant for needing a comforting object to fall asleep [χ2(3, n = 660) = 11.536, p = 0.009; OR = 0.665]: for every additional year of age, children were 1.5 times less likely to need a comforting object to fall asleep.

The full model containing all predictors was not statistically significant for irritability [χ2(3, n = 668) = 7.035, p = 0.071] or nightmares [χ2(3, n = 668) = 2.125, p = 0.547]. The model for willingness to go to bed [χ2(4, n = 640) = 54.840, p < 0.001] included four predictors (year, age, sex, and MSFsc). Only year made a statistically significant contribution. The OR of 3.709 denotes that not being willing to go to bed was almost 4 times more likely to occur in children assessed in 1995.

Multivariate analysis by sleep disturbances factors

Only Fearing the dark factor showed statistical significance, with a main effect of year [F(1, 655) = 5.171, p = 0.023, ɳ2 = 0.008] and no interaction effects of year*age, year*sex or age*sex.

Discussion

Despite the assumption that sleep has declined with busy modern lifestyles, roughly twenty years later, the overall mean sleep durations of Portuguese primary school children in our sample do not seem to have changed. However, in a closer look, we noticed that on school nights significantly less children were sleeping the recommended number of hours in 2016 when compared to 1995. On free days, although there was a greater percentage of children sleeping above the recommended number of hours in 2016 when compared to 1995, there was also a greater percentage of children sleeping below the recommended number of hours, suggesting a broader range of night sleep durations on free days in 2016 when compared to 1995. Albeit sleep schedules seem to have advanced since the 90 s (as children in the 2016 subsample show earlier wake-times, bedtimes and midpoints of sleep), when controlling for sex and age, only wake-times on free days as children grow older revealed a statistically significant advance.

Overall, sleep disturbances increased from 1995 to 2016. Year was a predictor for several bedtime disturbances. Specifically, children assessed in 2016 exhibited more bedtime resistance when compared to children assessed in 1995, with more children needing lights on and the presence of caregivers to settle to sleep, more children experiencing fear of the dark and having trouble returning to sleep after waking during the night; and less children settling to sleep autonomously. Inasmuch as the increase of sleep disturbances is only related to sleep onset difficulties, we hypothesize these differences might have occurred due to a change in parental attitudes and practices since 1995. It is possible that staying by their child’s side until they fall asleep has become a common practice among caregivers, as opposed to putting children to bed and withdraw, allowing them to self-sooth, as we hypothesize it would be a more usual behavior in 1995. Self-soothing emerges as an important developmental milestone associated with sleep regulation [23]. As parents may consider more adequate staying by their child’s side until sleep onset or even letting children fall asleep in their beds, children do not learn how to go to sleep independently. A recent study on the sleep patterns of first graders found resistance to fall asleep to be the most common sleep problem among children, with a prevalence of 30.7% [24]. Those authors also performed a binary logistic regression, in which the components of sleep hygiene could predict 18–25% of the variance for bedtime problems. Positive sleep habits are important to develop and maintain normal sleep patterns. Adequate sleep quantity and quality are protected by regular sleep–wake routines and well-established parental rules of sleep hygiene [25], including parental management of children’s screen time and use of electronic devices [26]. Regular bedtime routines and helping children learn to fall asleep autonomously at bedtime will also help them learn to return to sleep autonomously after night awakenings. These habits benefit attachment, security, and mental health, despite caregivers’ worries about harmful effects on children’s development and quality of parent–child relationship [27]. School-based sleep programs might constitute important opportunities to promote healthy sleep habits among school-age children [23], ergo preventing sleep disruptions and contributing to a healthy physical and mental development. For instance, a school-based sleep education program was associated with significant improvement in children’s sleep and academic performance [28]. A recent study reported a school-based health and mindfulness curriculum improved children’s objectively measured sleep [29].

This paper should be considered in light of some limitations. Although the 1995 and 2016 subsamples were collected in the same educational region, they were not collected in the same schools (and cities), and therefore we may not rule out the possibility that this factor might account for some differences. Since only 3rd and 4th graders were included in the analyses, the study is not representative of all primary school children. A parent-report questionnaire was used, which might result in a biased reporting of sleep behaviors. Hence, this work should be regarded as a preliminary study. Future studies should assess children’s sleep using objective measures and consider other psychosocial measures (e.g., screen use, emotional variables). It is also important to note that in Portugal the mismatch between local and sun clock was greater in 1995 than 2016 (cf. [30] and respective table [31]). Notably, in 1995, the clock time adopted in Portugal was more advanced in relation to solar time—which regulates to great extent the body clock—than in 2016, thus favoring the delay of sleep timings (see Roenneberg et al., 2019 [32]), at the very least at bedtime. This could possibly explain why sleep timings did not differ between the two time points despite the supposedly increasing use of electronic devices and exposure to screen time. It could also explain why sleep timings in free days were slightly advanced in 2016 when compared to 1995. In line with this proposition, we noticed over 65% of children in the 1995 sub-sample were not willing to go to bed, which suggests precisely children were not yet sleepy at the time they were expected to go to bed. In other words, children’s bedtime was too early in relation to their sleep–wake rhythm possibly because the clock time was advanced when compared to solar time in 1995. A key strength of the present study was the use of the same self-reported measure, enabling an accurate analysis of sleep durations, timings, and disturbances across the two time periods. Children’s sleep–wake patterns and difficulties have received little attention. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Portuguese study to investigate and compare school-age children’s sleep trends.

Conclusion

We compared the sleep–wake patterns of elementary school-age children in 1995 and about two decades later, in 2016. Overall, significantly less children were sleeping the recommended number of hours in 2016 and there was a slight advance in wake-times on free days from 1995 to 2016. Sleep onset disturbances increased from 1995 to 2016, perhaps due to a change in parental attitudes. Policies such as delaying school start times and implementing sleep education programs might be possible solutions to enhance children’s sleep and prevent sleep disruptions that deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to parents/tutors, teachers, and school administrators.

Authors contribution

MIC helped in conception and design of the article; combining data, analysis, and interpretation; draft of the paper; final approval. VC was involved in data collection and interpretation; revision and final approval. JA contributed to data collection and interpretation; revision and final approval. DRM and MHA performed critical review of the paper; revision and final approval, AAG helped in conception and design; data interpretation; critical review and final approval of the paper.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors declare that the procedures were followed according to the regulations established by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee and to the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association updated in 2013. The authors declare having followed the protocols in use at their working center regarding patients’ data publication. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Previous presentations

The abstract of this study was presented at the World Sleep Congress 2019.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li S, Arguelles L, Jiang F, et al. Sleep, school performance, and a school-based intervention among school-age children: a sleep series study in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matricciani L, Olds T, Petkov J. In search of lost sleep: secular trends in the sleep time of school-age children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Ruiter I, Olmedo-Requena R, Sánchez-Cruz JJ, Jiménez-Moleón JJ. Changes in sleep duration in Spanish children aged 2–14 years from 1987 to 2011. Sleep Med. 2016;21:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twenge JM, Krizan Z, Hisler G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adolescents 2009–2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med. 2017;39:47–53. 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Calamaro C, Mason T, Ratcliffe S. Adolescents living the 24/7 lifestyle: effects of caffeine and technology on sleep duration and daytime functioning. Pediatrics. 2009;23:1005–1010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cain N, Grandisar M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-age children and adolescents: a review. Sleep Med. 2010;11:735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akacem LD, Wright KP, LeBourgeois MK. Bedtime and evening light exposure influence circadian timing in preschool-age children: a field study. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 2016;1:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues D, Gama A, Machado-Rodrigues AM, et al. Home vs. bedroom media devices: Socioeconomic disparities and association with childhood screen- and sleep-time. Sleep Med. 2021;83:230–4.doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2021.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Leech JA. Changes in sleep duration and recreational screen time among Canadians, 1998–2010. J Sleep Res. 2016;26:202–209. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youngstedt SD, Goff EE, Reynolds AM, et al. Has adult sleep duration declined over the last 50+ years? Sleep Med Rev. 2016;28:69–85. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basner M, Dinges DF. Sleep duration in the United States 2003–2016: first signs of success in the fight against sleep deficiency? Sleep. 2018;41:1–16. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez J, Gershuny J, Foster R, De Vos M. Sleep differences in the UK between 1974 and 2015: Insights from detailed time diaries. J Sleep Res. 2018;28:e12753. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clara MI, Allen GA. An epidemiological study of sleep−wake timings in school children from 4 to 11 years old: Insights on the sleep phase shift and implications for the school starting times' debate. Sleep Med. 2020;66:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemente V. Sono e Vigília em Crianças de Idade Escolar: Hábitos, comportamentos e problemas [Unpublished master's thesis]. 1997. University of Coimbra.

- 15.Abrantes, J. Temperamento, cronótipo e padrões do sono em crianças dos 8 aos 11 anos [Master's thesis]. 2016. https://ria.ua.pt/bitstream/10773/18485/1/Documento%20TESE.pdf

- 16.Clemente V, Silva C, Ferreira AM, César H, Azevedo MH. Terapia cognitivo-comporta-mental na insónia: uma abordagem eficaz mas… esquecida. Ver Port Clín Geral. 1997;14:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho Bos S, Gomes AA, Clemente V, et al. Sleep and behavioral/emotional problems in children: a population-based study. Sleep Med. 2009;10:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira AM, Clemente V, Gozal D, et al. Snoring in Portuguese primary school children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:e64. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Pramstaller PP, et al. A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1038–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jankowski KS. Social jet lag: sleep-corrected formula. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34:531–535. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1299162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;8:52. doi: 10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health. 2015;1:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruber R. Making room for sleep: the relevance of sleep to psychology and the rationale for development of preventative sleep education programs for children and adolescents in the community. Can Psychol/Psychol Can. 2013;54:62–71. doi: 10.1037/a0030936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khazaie H, Zakiei A, Rezaei M, Komasi S, Brand S. Sleep pattern, common bedtime problems, and related factors among first-grade students: epidemiology and predictors. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2018;7:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2018.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buxton OM, Chang A, Spilsbury JC, et al. Sleep in the modern family: protective family routine for child and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health. 2015;1:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto Y, Kaneita Y, Jike M, et al. Clarifying the factors affecting the implementation of the “early to bed, early to rise, and don’t forget your breakfast” campaign aimed at adolescents in Japan. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2021;19:325–336. doi: 10.1007/s41105-021-00321-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mindell JA, Moore M. Bedtime problems and night wakings. In: Sheldon SH, Ferber R, Kryger MH, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric sleep medicine. 2. Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruber R, Somerville G, Bergmame L, Fontil L, Paquin S. School-based sleep education program improves sleep and academic performance of school-age children. Sleep Med. 2016;21:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chick C, Anker L, Singh A, et al. A school-based health and mindfulness curriculum improves children's objectively measured sleep: a prospective observational cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.oal.ul.pt [internet homepage]. Lisboa: Observatório Astronómico de Lisboa [Lisbon Astronomic Observatoire]; [accessed 2021 Dez 15]. Available at: http://oal.ul.pt/hora-legal/legislacao-sobre-a-hora-legal/

- 31.Observatório Astronómico de Lisboa [Lisbon Astronimic Observatoire]. Hora legal em Portugal Continental [1911–2018] [Legal hour in continental Portugal [1911–2018]]. Lisbon. [accessed 2021 Dez 15]. Available at http://oal.ul.pt/documentos/2018/01/hl1911a2018.pdf/

- 32.Roenneberg T, Winnebeck EC, Klerman EB. Daylight saving time and artificial time zones—a battle between biological and social times. Front Physiol. 2019;10:e944. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]