Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hyperbilirubinemia with hepatic metastases is a common complication and a poor prognostic factor for colorectal cancer (CRC). Effective drainage is often impossible before initiating systemic chemotherapy, owing to the liver’s diffuse metastatic involvement. Moreover, an appropriate chemotherapeutic approach for the treatment of hyperbilirubinemia is currently unavailable.

CASE SUMMARY

The patient, a man in his 50s, presented with progressive fatigue and severe jaundice. Computed tomography revealed multiple hepatic masses with thickened walls in the sigmoid colon, which was pathologically confirmed as a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. No RAS or BRAF mutations were detected. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score was 2. Biliary drainage was impossible due to the absence of a dilated bile duct, and panitumumab monotherapy was promptly initiated. Subsequently, the bilirubin level decreased and then normalized, and the patient’s PS improved to zero ECOG score after four cycles of therapy without significant adverse events.

CONCLUSION

Anti-EGFR antibody monotherapy is a safe and effective treatment for RAS wild-type CRC and hepatic metastases with severe hyperbilirubinemia.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Panitumumab, Chemotherapy, Hyperbilirubinemia, Jaundice, Case report

Core Tip: We report the case of a patient with colorectal cancer and severe hyperbilirubinemia who was successfully treated with anti-EGFR antibody monotherapy. As this approach is safe and potentially lifesaving, it should be considered as a treatment option for hyperbilirubinemia due to hepatic metastases when biliary drainage is impossible.

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. The liver is the most common site of metastasis in CRC owing to the draining system of the portal vein. Hyperbilirubinemia is a serious consequence of hepatic metastasis and is a poor prognostic factor[2]. Biliary drainage is often difficult because of diffuse hepatic involvement. Clinical decision-making in these settings is challenging, because chemotherapeutic agents that are metabolized in the liver require dose adjustments and are contraindicated in severe hepatic failure. As more major clinical trials exclude the patients with severely impaired organ function, little evidence supports an optimal regimen and dose of chemotherapy for severe hyperbilirubinemia. Although the use of cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with hepatic metastases and severe hyperbilirubinemia has been reported in a few case series, most cases did not achieve satisfactory outcomes and severe treatment-related adverse events were also reported. Therefore, no appropriate chemotherapeutic approach has yet been established for these patients. Herein, we report a case of CRC with hepatic metastases and severe hyperbilirubinemia that was successfully treated using panitumumab monotherapy. We suggest this approach as a novel treatment option for hyperbilirubinemia caused by hepatic metastases when biliary drainage is impossible.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A patient in his 50s experienced weight loss and progressive fatigue.

History of present illness

Laboratory tests revealed elevated transaminase and bilirubin levels, prompting a prompt referral to our hospital.

History of past illness

He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Personal and family history

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

Physical examination

The patient was afebrile on admission. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) was 2. Physical examination revealed scleral icterus and yellow skin. The patient’s abdomen was flat and non-tender, with no palpable masses.

Laboratory examinations

The results of laboratory blood tests revealed the following: Serum total bilirubin level: 8.4 mg/dL, conjugated bilirubin level: 6.2 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase: 141 U/L, alanine aminotransferase: 240 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase: 372 U/L, alkaline phosphatase: 447 U/L, gamma glutamyl transferase: 959 U/L, albumin: 3.3 g/dL, and prothrombin time: 99%. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was markedly elevated at 396 ng/mL.

Imaging examinations

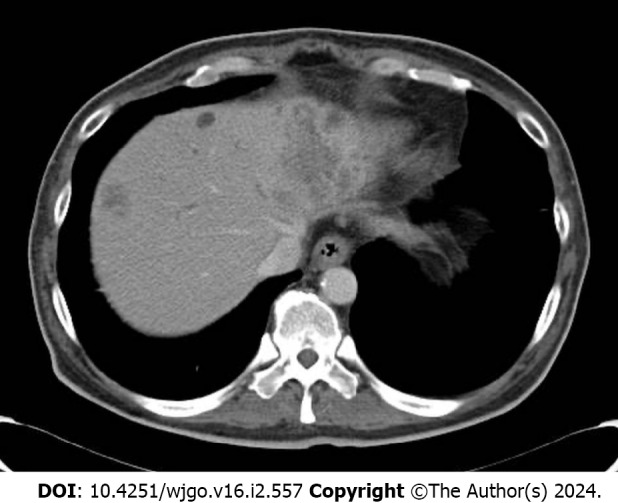

A computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated multiple hepatic masses with a thickened wall at the sigmoid colon (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Image of hepatic metastases on admission. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing multiple hepatic masses.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Metastatic CRC was diagnosed, and obstructive jaundice with liver metastasis was suspected. Biomarker expression was as follows: RAS wild-type, BRAF wild-type, and microsatellite stable.

TREATMENT

Endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage failed, owing to the diffuse involvement of the liver and the absence of a bile duct dilated enough to drain. These findings indicated the need for anticancer therapies. Consequently, panitumumab monotherapy (6 mg/kg, every two weeks) was initiated.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

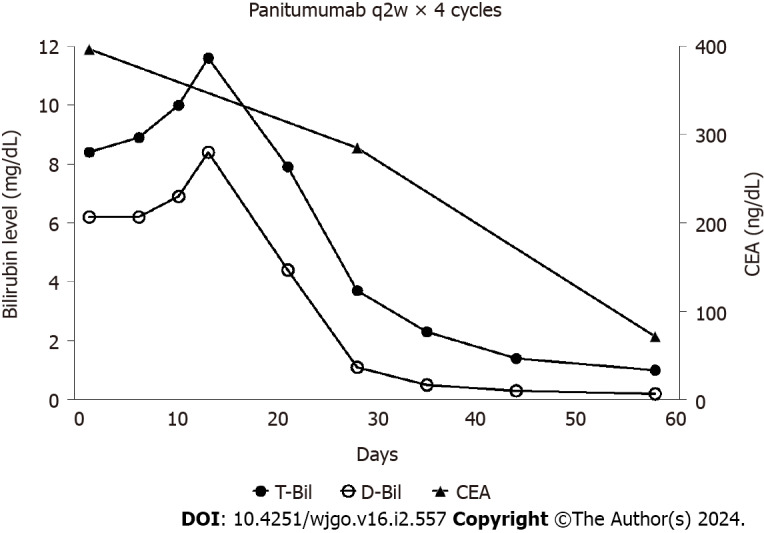

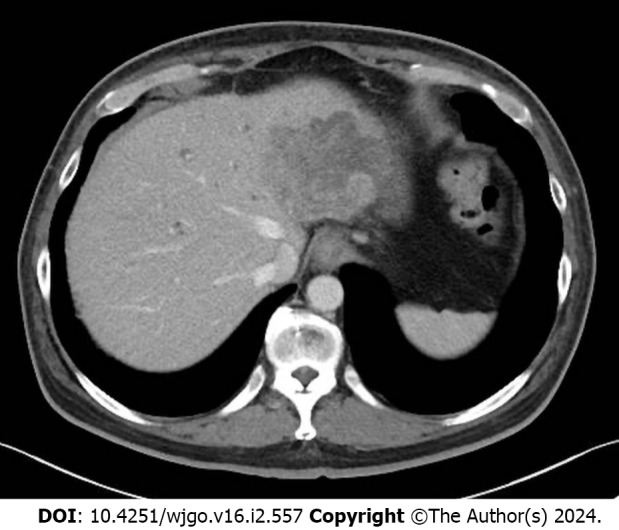

After two cycles of panitumumab monotherapy, the bilirubin level decreased markedly and completely normalized after four cycles (Figure 2). The patient’s ECOG PS improved to 0 and CEA levels decreased to 71 ng/mL. A CT tomography revealed shrinking hepatic masses (Figure 3). Therefore, fluorouracil plus leucovorin and oxaliplatin (a modified FOLFOX6 regimen) were added to panitumumab therapy. The patient received 22 cycles of this regimen over a year until the disease progressed. Thereafter, the patient declined further chemotherapy and received palliative care at a hospice.

Figure 2.

Clinical course of the patient. Bilirubin and carcinoembryonic antigen levels markedly decreased after four cycles of panitumumab monotherapy. CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen.

Figure 3.

Image of hepatic metastases after 4 cycles of panitumumab monotherapy. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed decreased sizes of the hepatic masses.

DISCUSSION

Anti-EGFR antibody monotherapy was found to be a safe and effective treatment approach for patients with RAS wild-type CRC and hepatic metastases with severe hyperbilirubinemia.

In general, selecting a chemotherapy regimen for hyperbilirubinemia is particularly challenging. This is because hepatic dysfunction affects the pharmacokinetics of chemotherapeutic agents and may worsen their toxicity. Cytotoxic agents against CRC include fluoropyrimidines such as oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Fluoropyrimidines are mostly eliminated by hepatic metabolism, and some experts have suggested that they are contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction[3]. Platinum derivatives are predominantly excreted through the renal tract. Although a dose-escalating pharmacological study showed that oxaliplatin can be administered without dose reduction in patients with severe liver dysfunction, several cases of oxaliplatin-induced hepatotoxicity have been reported[4,5]. Activation of irinotecan and detoxification of its metabolite, SN-38, occur predominantly in the liver; moreover, the toxicity of this drug may be increased in patients with reduced biliary excretion[5,6].

Recently, several studies have reported the use of cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with hepatic metastases and severe hyperbilirubinemia[7-10]. Some cases showed reasonable and durable responses; however, most had an average OS of only several months, and some experienced severe treatment-related adverse events. In addition, cytotoxic chemotherapy often requires dose reduction. This is a considerable concern, because intensive chemotherapy is required to achieve a sufficient response to alleviate hyperbilirubinemia[5,8]. Furthermore, the PS of patients with severe hyperbilirubinemia is often poor at the time of diagnosis and progressively worsens, making them more vulnerable to chemotherapy toxicity.

By contrast, mAbs are mostly eliminated via intracellular catabolism, and are relatively unaffected by hepatic or renal functions[11]. Anti-EGFR antibodies, such as panitumumab and cetuximab, are recommended as first-line treatments for patients with RAS/BRAF wild-type and left-sided CRCs[12,13]. Although panitumumab is usually administered in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy, monotherapy with this antibody has shown a reasonable response rate. Even in patients with refractory disease, the response rate reached 30% in those with RAS wild-type CRC[14]. Recently, the efficacy and safety of panitumumab monotherapy in frail or elderly patients who are considered unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy has been reported. One of these reports showed a considerably high response rate (up to 65%) to RAS wild-type left-sided CRC as initial therapy[15]. Several studies have supported the use of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in patients with severe hyperbilirubinemia[5,16] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Previous case reports of patients with colorectal cancer and hyperbilirubinaemia treated with anti-EGFR antibodies with or without cytotoxic agents

|

Age (yr), gender

|

ECOG PS

|

Primary site

|

KRAS

|

Previous treatment

|

Total bilirubin (mg/dL)

|

Treatment

|

Overall survival (month)

|

| 63, M[16] | 2 | Unknown | WT | FOLFIRI, FOLFOX | 2.5 | Cetuximab | 1.3 |

| 66, M[16] | 2 | Unknown | WT | IRIS, FOLFOX + Bevacizumab | 2.3 | Cetuximab | 3.1 |

| 65, M[16] | 2 | Unknown | WT | FOLFIRI, FOLFOX | 2.6 | Cetuximab | 5.9 |

| 45, F[16] | 3 | Unknown | WT | FOLFOX, FOLFIRI + Bevacizumab | 7.9 | Cetuximab | 2.8 |

| 56, F[16] | 1 | Unknown | WT | FOLFOX, FOLFIRI + Bevacizumab | 13 | Cetuximab | 2.6 |

| 69, M[16] | 3 | Unknown | WT | Irinotecan | 7.4 | Cetuximab | 1.2 |

| 78, M[16] | 2 | Unknown | MT | FOLFOX + Bevacizumab, FOLFIRI | 9.7 | Cetuximab | 0.5 |

| 43, M[9] | 3 | Right | WT | No | 9.4 | FOLFOX + Panitumuab | 1.5 |

| 48, M[17] | Unknown | Left | WT | No | 6.2 | FOLFOX + Cetuximab | ≥ 7 |

M: Male; F: Female; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS: Performance status; WT: Wild type.

However, the role of anti-EGFR antibodies in patients with right-sided CRCs remains unclear. While patients with right-sided CRC do not benefit as much from anti-EGFR antibodies as those with left-sided CRC in the setting of first-line treatment, the use of anti-EGFR antibodies as a later treatment is a widely accepted approach[12]. Thus, our approach to initial anti-EGFR monotherapy in the setting of severe hyperbilirubinemia requires careful consideration of right-sided CRC owing to its possible lower response rate[15].

Further studies should be conducted to validate this approach on both sides of the CRC.

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates the safety and efficacy of anti-EGFR antibody monotherapy in a patient with CRC and hepatic metastases with severe hyperbilirubinemia. Anti-EGFR antibody monotherapy should be considered a treatment option for patients with RAS wild-type CRC with hyperbilirubinemia due to hepatic metastases when biliary drainage is impossible.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Written informed consent for medical treatment was obtained from the patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 25, 2023

First decision: November 30, 2023

Article in press: January 11, 2024

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang GX, China; Wu HT, China S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Toshiaki Tsurui, Department of Medical Oncology, Showa University, Tokyo 1428555, Japan. ttsurui.quantum@gmail.com.

Yuya Hirasawa, Department of Medical Oncology, Showa University, Tokyo 1428555, Japan.

Yutaro Kubota, Department of Medical Oncology, Showa University, Tokyo 1428555, Japan.

Kiyoshi Yoshimura, Department of Medical Oncology, Showa University, Tokyo 1428555, Japan; Department of Clinical Immuno Oncology, Clinical Research Institute of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Showa University, Tokyo 1578577, Japan.

Takuya Tsunoda, Department of Medical Oncology, Showa University, Tokyo 1428555, Japan.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:627–647. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, Ge LY, Yu T, Liang Y, Yin Y, Chen H. The prognostic impact of serum bilirubin in stage IV colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32 doi: 10.1002/jcla.22272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floyd J, Mirza I, Sachs B, Perry MC. Hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:50–67. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Synold TW, Takimoto CH, Doroshow JH, Gandara D, Mani S, Remick SC, Mulkerin DL, Hamilton A, Sharma S, Ramanathan RK, Lenz HJ, Graham M, Longmate J, Kaufman BM, Ivy P National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group. Dose-escalating and pharmacologic study of oxaliplatin in adult cancer patients with impaired hepatic function: a National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group study. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3660–3666. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsoueidi R, Craig J, Mourad H, Richa EM. Safety and efficacy of FOLFOX followed by cetuximab for metastatic colorectal cancer with severe liver dysfunction. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:155–160. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raymond E, Boige V, Faivre S, Sanderink GJ, Rixe O, Vernillet L, Jacques C, Gatineau M, Ducreux M, Armand JP. Dosage adjustment and pharmacokinetic profile of irinotecan in cancer patients with hepatic dysfunction. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4303–4312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walia T, Quevedo JF, Hobday TJ, Croghan G, Jatoi A. Colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases and severe hyperbilirubinemia: A consecutive series that explores the benefits and risks of chemotherapy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:1363–1366. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quidde J, Azémar M, Bokemeyer C, Arnold D, Stein A. Treatment approach in patients with hyperbilirubinemia secondary to liver metastases in gastrointestinal malignancies: a case series and review of literature. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8:144–152. doi: 10.1177/1758834016637585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasi PM, Thanarajasingam G, Finnes HD, Villasboas Bisneto JC, Hubbard JM, Grothey A. Chemotherapy in the Setting of Severe Liver Dysfunction in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2015;2015:420159. doi: 10.1155/2015/420159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh YS, Huang ML, Chang SF, Chen CF, Hu HM, Wang JY. FOLFIRI combined with bevacizumab as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer patients with hyperbilirubinemia after UGT1A1 genotyping. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:478–481. doi: 10.1159/000358799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:548–558. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, Modest DP, Heinemann V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, Peeters M, Lenz HJ, Venook A, Heinemann V, Van Cutsem E, Pignon JP, Tabernero J, Cervantes A, Ciardiello F. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1713–1729. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TW, Elme A, Kusic Z, Park JO, Udrea AA, Kim SY, Ahn JB, Valencia RV, Krishnan S, Bilic A, Manojlovic N, Dong J, Guan X, Lofton-Day C, Jung AS, Vrdoljak E. A phase 3 trial evaluating panitumumab plus best supportive care vs best supportive care in chemorefractory wild-type KRAS or RAS metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1206–1214. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terazawa T, Kato T, Goto M, Ohta K, Noura S, Satake H, Kagawa Y, Kawakami H, Hasegawa H, Yanagihara K, Shingai T, Nakata K, Kotaka M, Hiraki M, Konishi K, Nakae S, Sakai D, Kurokawa Y, Shimokawa T, Satoh T. Phase II Study of Panitumumab Monotherapy in Chemotherapy-Naïve Frail or Elderly Patients with Unresectable RAS Wild-Type Colorectal Cancer: OGSG 1602. Oncologist. 2021;26:17–e47. doi: 10.1002/ONCO.13523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shitara K, Takahari D, Yokota T, Shibata T, Ura T, Muro K, Inaba Y, Yamaura H, Sato Y, Najima M, Utsunomiya S. Case series of cetuximab monotherapy for patients with pre-treated colorectal cancer complicated with hyperbilirubinemia due to severe liver metastasis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:275–277. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Utsunomiya S, Okumura A, Watanabe K, Kunii S, Ishikawa D, Hirosaki T, Yamada K, Kaga A. A case of liver metastases with hyperbilirubinemia that was safely treated with chemotherapy (FOLFOX plus Cetuximab) Ann Oncol. 2017;28 Suppl 9:ix105. [Google Scholar]