Abstract

Objective

To improve understanding of the drivers of the increased caesarean section (CS) rate in Romania and to identify interventions to reverse this trend, as well as barriers and facilitators.

Design

A formative research study was conducted in Romania between November 2019 and February 2020 by means of in-depth interviews and focus-group discussions. Romanian decision-makers and high-level obstetricians preselected seven non-clinical interventions for consideration. Thematic content analysis was carried out.

Participants

88 women and 26 healthcare providers and administrators.

Settings

Counties with higher and lower CS rates were selected for this research—namely Argeș, Bistrița-Năsăud, Brașov, Ialomița, Iași, Ilfov, Dolj and the capital city of București (Bucharest).

Results

Women wanted information, education and support. Obstetricians feared malpractice lawsuits; this was identified as a key reason for performing CSs. Most obstetrics and gynaecology physicians would oppose policies of mandatory second opinions, financial measures to equalise payments for vaginal and CS births and goal setting for CS rates. In-service training was identified as a need by obstetricians, midwives and nurses. In addition, relevant structural constraints were identified: perceived lower quality of care for vaginal birth, a lack of obstetricians with expertise in managing complicated vaginal births, a lack of anaesthesiologists and midwives, and family doctors not providing antenatal care. Finally, women expressed the need to ensure their rights to dignified and respectful healthcare through pregnancy and childbirth.

Conclusion

Consideration of the views, values and preferences of all stakeholders in a multifaceted action tailored to Romanian determinants is critical to address relevant determinants to reduce unnecessary CSs. Further studies should assess the effect of multifaceted interventions.

Keywords: quality in health care, health policy, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In Romania, the excessive use of caesarean section (CS) has become a public health challenge. This is the first study to improve understanding of the drivers of the increase and identify interventions to reverse this trend, alongside barriers and facilitating factors.

This study was driven by the Ministry of Health and guided by the country’s needs reflected in Romania’s National Health Strategy, an initial analysis of routine hospital data, and a stakeholder workshop.

We used the rigorous methodology proposed in the generic formative research protocol prepared by the WHO, which was designed as a guide for contextual assessment and understanding before implementing any intervention to optimise the use of CS.

A key strength of our study is the incorporation of the views and concerns of both women and healthcare providers. However, we did not interview companions, family members or family doctors. While our research was conducted across different counties, the findings may not be transferable to all settings in Romania.

Introduction

Caesarean section (CS) rates have been increasing worldwide1 to levels that are not medically justified.2 This poses a major public health concern3 that needs to be addressed locally with evidence-based action to reduce unnecessary CSs. When medically justified, a CS can effectively prevent maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity, but there is no evidence showing the benefits of caesarean delivery for women or infants who do not require the procedure. As with any surgery, CSs are associated with short-term and long-term risks, which can extend many years beyond the delivery and affect the health of the woman and child, as well as future pregnancies. These risks are higher in women with limited access to comprehensive obstetrical care.4

Policymakers face complex decisions when deciding about interventions to include in national health programmes to optimise CS rates. Numerous factors underline the increase—both clinical and non-clinical5—such as the increase in incidence of maternal obesity, multiple pregnancies and a higher maternal age at birth, but also differences in health provider practices, fear of malpractice litigation6 and economic or organisational factors. Sociocultural aspects should also not be overlooked,7 such as women’s desire to determine how and when their babies are born.8

Recognising the increasing relevance of non-medical factors in the rise of CS rates worldwide,9 in 2018 the WHO released recommendations on non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary CSs.10 11 Given the multifactorial nature of the increase and intrinsic variations between countries, before implementing any intervention to reduce rates, WHO recommends conducting research to define locally relevant determinants that can be targeted by tailored interventions.10 This study aimed to generate evidence on (1) the views of women, healthcare providers and healthcare administrators; and (2) barriers and facilitating factors for implementation of non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary CSs to inform policy-making in Romania.

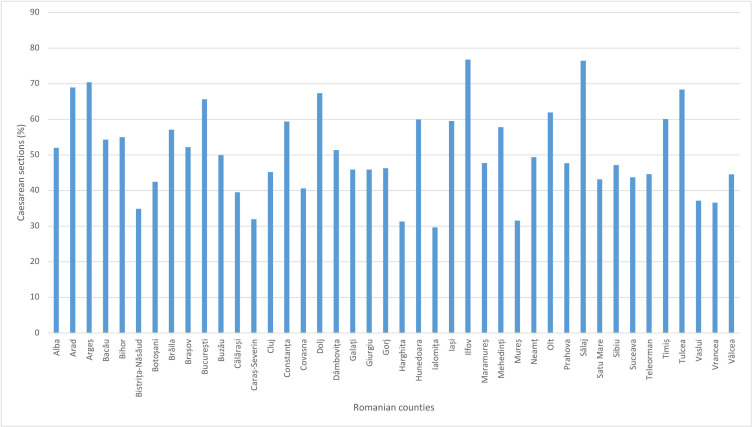

Romania’s National Health Strategy 2014–2020 highlights the excessive use of CSs as a public health problem and a priority for maternal and child health. In 2018, the national CS rate was 44.7%.12 This contrasts sharply with the 17% average rate in the Nordic countries, which have sustained low CS rates over recent decades.13 Figure 1 shows the wide variability of the CS rate between Romanian counties in 2019, from 76.8% in Ilfov (one of the wealthiest) to 29.6% in Ialomița.14

Figure 1.

Proportion of caesarean sections in Romanian counties (2019).

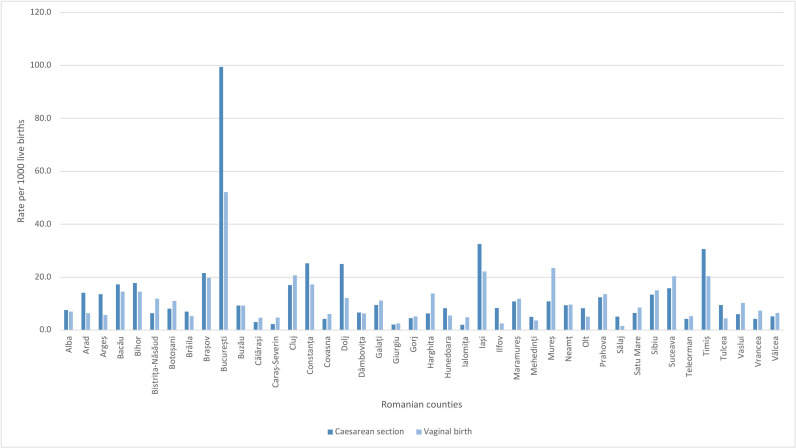

București (Bucharest) (65.6%) had one of the highest rates of CS births in 2019.14 The capital city also has the highest CS rate per 1000 live births (99.5 CS per 1000 live births) compared with the other counties (figure 2). Most CSs (88.6%) are conducted in the public sector. The proportion of CS births within the obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) wards of hospitals ranged from 92.5% to 0% in 2018, and although CS delivery is predominant in level 3 and level 2 public health facilities, 53 O&G wards of hospitals at the lowest level (level 1) reported a high percentage of CS births. For example, in 2018, Argeș county reported 92.5% of births by CS in level 1 hospitals.

Figure 2.

Caesarean section and vaginal birth rates per 1000 live births in Romanian counties (2019).

Box 1 describes the characteristics of the health system model for maternity care in Romania.

Box 1. Romania’s health system model for maternity.

Organisation and governance

Maternity care is included in the minimum benefit package funded by the social health insurance system that includes antenatal care and childbirth for all pregnant women (both insured and uninsured).

Financing

The National Health Insurance House reimburses the hospitals at a higher tariff (two to three times more) for caesarean section (CS) than for vaginal birth (depending on complications).29

Human resources

Romania had 13.9 obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G) physicians per 100 000 inhabitants in 2018 (European Union (EU) average 15.5 in 2014).30 Midwives are also in significant deficit: in 2013 Romania had 16.5 midwives per 100 000 inhabitants (EU average 61.1 in 2013).31

The professional associations set educational standards and the criteria for a licence to practise of their respective professions, which needs to be validated every 5 years for physicians and yearly for midwives and nurses.27

Health professionals employed in public hospitals receive the same salary, regardless of the number of deliveries they attend or the type of delivery.

Provision of care

Most pregnant women are followed up by their O&G physicians and visit the family doctor only occasionally; eg, to register the pregnancy.32

The system is heavily led by doctors, which also includes management of low-risk pregnancies. Nurses and midwives are relegated to auxiliary care.29

Antenatal education is not systematically provided in the public sector and is mostly available in the private sector.33

Childbirth care is provided in public and private hospitals.

The presence of a companion during childbirth is not allowed in public hospitals.

Epidural anaesthesia during labour is not a common practice in public hospitals.34

The clinical guideline for CSs was updated in 2019 and endorsed as secondary legislation by the Ministry of Health. Hospitals have the freedom to develop their own protocols based on national guidelines, and accreditation standards do not refer to either the clinical guideline or hospital protocols regarding the mode of birth. Also, CS on maternal request is among the indications of the national CS clinical guideline.

Data regarding the number of CSs performed on maternal request are not collected.

Political concern and commitment to reduce unnecessary CSs has grown in recent years; this has led to discussions in the Romanian Parliament and with WHO on the need to reduce the CS rate and to identify and implement strategies and public policies to support vaginal delivery. In 2019, the Ministry of Health of Romania and WHO co-organised a workshop on implementing the Robson classification, recommended by WHO to assess, monitor and evaluate CS rates.15

This paper presents the results of the collaborative effort between the Ministry of Health, the WHO Country Office in Romania, the WHO Regional Office for Europe and WHO headquarters to improve understanding of the drivers of the increasing CS rates in Romania. We conducted formative research to describe women’s and healthcare providers’ views and opinions on specific interventions to reduce CS including barriers and facilitating factors to their implementation. The ultimate aim is to use the study findings to inform the design and implementation of interventions to reverse this trend that are acceptable and feasible for the local context and stakeholders.

Methods

This study used qualitative research case study methods to collect and analyse information. The generic formative research protocol prepared by WHO headquarters and designed as a guide for contextual assessment and understanding for anyone planning to take action to optimise the use of CS was used.16 The research included a document review, focus groups with women and interviews with healthcare providers and administrators, and was carried out between November 2019 and February 2020. This paper reports on the findings of the focus groups and interviews with stakeholders.

Study setting and population

Based on an initial analysis of routine hospital data in Romania, counties with higher and lower CS rates were selected for this research—namely Argeș, Bistrița-Năsăud, Brașov, Ialomița, Iași, Ilfov, Dolj and the capital city of București (Bucharest). In each county, the research included women aged 16–46 years, from urban and rural areas, with a parity history to represent nulliparous, multiparous with previous CS and multiparous without previous CS. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants aiming for diversity (mix of urban or rural, residence, parity, age and ethnicity). Women attending antenatal care and women in the postpartum period before discharge from the hospital were invited to participate based on the topic of the focus-group discussion and considering the variability of patients in terms of demographics, geographical area and parity history. Invitation and recruitment were conducted by a research assistant who was not hospital staff. For those women accepting the invitation, the focus groups were scheduled at the convenience of the women. In addition, healthcare providers and healthcare administrators were recruited based on their geographical area, availability and position—including midwives, nurses, O&G physicians, medical directors and a representative of the National Health Insurance House (NHIH). No exclusion criteria were applied.

Data collection

Data were collected from focus-group discussions with women and in-depth interviews with healthcare providers and healthcare administrators, following the generic protocol.16 The discussions lasted 30–60 min and included two facilitators, including men and women, with a public health, medicine or sociology background. Focus groups were conducted in the hospital facilities (eg, in a meeting room) or in a preassigned location in the city, and informed consent was obtained from each participant before the interview. The guidelines proposed in the generic formative research were translated into Romanian and piloted on two to three women each. During the session, snacks were provided.

Interviews with healthcare providers and administrators lasted 30–60 min and were conducted in hospital settings. Consent was obtained from each participant beforehand. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in full, except for the respondents who refused the recording, in which case the researcher took notes during the interview.

Data analysis

A thematic content analysis of anonymised data was carried out. The data were segmented by type of informant. Categories of analysis were generated through a mix of the interview guide and those emerging from the data. Themes were identified, coded, recoded and classified, while examining new sections of text, to identify common patterns by looking at regularities, convergences and divergences in data through constant comparisons and checking with members of the team.

Patient and public involvement statement

The interventions included in the formative research were based on the instrument published in the generic protocol16 and the results of a Ministry of Health of Romania and WHO workshop held in Bucharest in 2019. Romanian decision-makers and high-level O&G professionals selected seven non-clinical interventions with the potential to reduce CS rates based on the WHO instrument for formative research: prenatal education and support; decision aids for the mode of delivery; mandatory second opinion before conducting a CS; in-service training and implementation of clinical practice guidelines; equalising physician pay for vaginal and CS births; setting a goal for CS rates at a facility level; and policies limiting legal liability and malpractice lawsuits. Women, healthcare providers and administrators were not specifically involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination of this research.

Results

In total, 88 women aged 16–46 years from urban and rural settings and 26 O&G professionals (nurses, midwives and O&G physicians), decision-makers at the hospital level (hospital managers, medical directors and chief nurses) and system level (representative of NHIH) participated in the study. Few doctors and nurses refused to participate. Participant quotations are shown in italic.

Mode of birth preferences and perceived benefits

Nulliparous women were more hesitant and less convinced about the mode of delivery, while multiparous women had clearer preferences and sometimes preconceived views. Among women with a previous vaginal delivery, there was a strong preference for vaginal birth. However, women did not consider a vaginal birth after a previous CS, showing the perception that a history of CS automatically sets the course of subsequent births for surgical delivery.

Benefits of CSs perceived by women included effortless delivery of the newborn; a quicker, less painful procedure; and avoidance of fear of the unknown during labour. Women also identified CSs as beneficial in the case of an obstetrical emergency. Benefits of vaginal birth described by women were faster healing, better mobility, absence of or minimal pain after the birth, immediate breast feeding and the belief that vaginal birth is the ‘natural’ option.

While nurses clearly favoured vaginal birth, some O&G physicians stated their preference for CS as the mode of birth. Reasons underlying this preference were better control over fetal risks compared to unexpected complications of vaginal delivery, lower risk of malpractice complaints and doctors’ convenience (lower workload, overall shorter duration of the birth and avoiding going back to the hospital during night time). An O&G physician said, ‘I prefer the caesarean delivery because it involves no risk for the fetus. It is, of course, also faster for the obstetrician, and practically we are less at risk of malpractice complaints when we perform a caesarean’.

Healthcare providers admitted that the CS rate is high in Romania, but they argued that, to reduce use of CS, changes in the thinking processes of professionals and the population are required, as well as revision of antenatal care services (including the role of the family doctor, interventions to increase population-level information and psychological support for women).

Interventions targeted to women

Education, birth preparation classes and support programmes

Currently, education and birth preparation are optional, provided only in selected health facilities—mainly private hospitals and clinics—and paid for out of pocket. The courses, organised by hospitals, are led by midwives and include breathing, relaxation and massage techniques.

Women wanted more reliable information on birth for a number of topics: mode of delivery, delivery process, risks and benefits for the mother and baby. Most of the women would welcome birth preparation classes, although the unpredictable nature of labour and birth was acknowledged. A woman with previous CS commented: You can control pregnancy and motherhood only to a small extent. The pregnancy is unpredictable, and no matter how well informed you are, or how good the doctor is, surprises can occur at any time, and no one can do miracles. O&G physicians were identified as women’s main source of trustable information. For example, a woman with previous CS said, I believe in the gynaecologist’s opinion: talking to him is important, more important than anything else. Nevertheless, women considered that O&G physicians allocate little time to discuss birth options. None of the women stated that they had discussed mode of delivery with the family doctor.

Midwives and nurses underlined the importance of prenatal education and the need to include the women’s companion, since husbands cannot attend childbirth: their participation is not allowed. Some of the O&G physicians considered that birth preparation classes are a task for midwives.

Decision-aid tools

Women would use a decision-aid tool if it contained personalised information regarding evolution of the pregnancy and childbirth from a trusted source using plain language. Some women thought it would be useful when engaging in dialogue with health professionals, but they also feared that such a tool may result in less time and a lower number of contacts with the O&G physician. They also expressed concern about the anxiety that such educational materials can provoke. A woman with a previous vaginal birth claimed, they might write I don’t know what about the caesarean section, or the normal birth… and you become afraid.

O&G physicians would consider a decision-aid tool with evidence-based information endorsed by the physician useful. Obstetricians felt that any attempt at implementing new tools in the health system is difficult by default, although no specific barriers were reported. They thought that decision-aid tools should include information about the mode of delivery, course of pregnancy, timeline and milestones of pregnancy monitoring.

Interventions targeted to healthcare providers

Revision and better adaptation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines

All respondents acknowledged the national O&G clinical guideline revised in 2019 and endorsed as secondary legislation by the Ministry of Health. Medical doctors considered these an important dimension of medical practice because they provide some safety from a malpractice accusation. According to respondents, the College of Physicians and the court ask for the guidelines in the case of a complaint or litigation: guidelines show you the steps [you have to follow] and using them in [the clinical] practice, you feel more secure. In the case of malpractice litigation, it can defend or impeach you, as the case may be.

Nurses and midwives were also aware of the guideline. Some hospitals have developed protocols for nurses, but they noted that: there are no guidelines for midwives and in the guidelines for doctors there is very little reference to the midwives’ practice.

There is no systematic approach to clinical guideline accessibility, dissemination, training and physician–nurse communication. One O&G physician claimed that in my hospital, […] each of us signed that we know them, but guidelines and protocols are largely ignored; there was no discussion or training regarding their use. Evaluation of implementation of clinical guidelines in hospitals is not a generalised practice, and algorithms for management of labour and complications are not available. Some O&G physicians were reluctant about the change and perceived protocols and guidelines as increasing the burden of work. One O&G physician described this reluctance: doctors see bureaucracy and waste of time – there are too many papers to be read and papers to be signed. A nurse also identified a generational effect among O&G physicians, where younger doctors are more open to using the guidelines.

Simulation-based obstetrics and neonatal emergency training

O&G professionals would welcome simulation-based obstetrics and neonatal emergency training in multidisciplinary teams. A nurse said: I would love to have special mannequins and a simulator for the delivery room. However, financial barriers for specialised training opportunities were also acknowledged, as a nurse noted: the hospital does not have resources to pay for courses or to organize them, but it does offer nurses free days to attend training.

Some respondents perceived that there are fewer opportunities for younger generations of O&G specialists to practise vaginal delivery after CS (VBAC), trial of labour after CS (TOLAC) or instrumental vaginal delivery, but others recognised that we all need to refresh knowledge and skills now and then. Although the national clinical guideline includes statements to assist O&G decisions about TOLAC, respondents stated that not even the leading O&G specialists prefer to perform TOLAC because they fear complications that might lead to malpractice accusations. Also, a woman with previous CS described: I think they see it [CS] as a safer modality. And yes, after that [first CS], it [caesarean childbirth] becomes routine.

Implementation of mandatory second opinion before conducting a CS

Some hospitals have an established protocol for second opinion before a CS as their usual internal procedure; in others, the head of the O&G ward approves all CSs.

Some women perceived that a mandatory second opinion would increase their safety and confidence in the physician’s decision regarding the birth method; others perceived this as a limitation of their preferences. Some women underlined that for physicians with a preference for CS births, a second mandatory opinion should be necessary. Other women agreed with a mandatory second opinion before CS for at-risk births.

Although healthcare providers and administrators acknowledged the high CS rate in the country, generally, they would not trust mandatory second opinion as an effective intervention to lower it. There was a perception that doctors would feel safer when making decisions in complicated cases and share the responsibility, strengthening teamwork. An O&G physician said: if there are two agreeing opinions and I did what a colleague agreed, this has more weight, irrespective of the outcome of a complicated case. However, healthcare providers also identified several barriers to implementation. A second opinion could be seen as a threat; women may distrust providers; and it might create certain dynamics among O&G physicians, as an O&G physician identified: ‘they [O&G physicians who perform more CSs] would ask their colleagues with common affinities for this second opinion and some gynaecologists are more attached to CS delivery, and they would be upset with a contrasting opinion. It could also affect the personal financial reward associated with CS in the private health sector, as one O&G physician stated: I do not think gynaecologists would leave their private practices in the afternoon to come back to the hospital to give a so-called mandatory opinion. In remote areas with fewer O&G physicians, it might also be difficult to find one with higher clinical qualifications than the doctor requiring the consultation.

Interventions targeted to health organisations, facilities and systems

Reforms equalising physician fees for vaginal births and CSs

Currently, as an O&G physician said, in the public health sector the doctor has no financial incentives because he is paid [a fixed] salary. Thus, most medical doctors claimed that equalising tariffs for vaginal births and CSs would not have an effect in reducing the CS rates. An O&G physician claimed: obstetricians prefer to do a caesarean […] for other reasons: time, convenience, safety… and equalizing prices would not change the current behaviour.

Healthcare administrators stated that the current diagnosis-related group system to classify patients according to their diagnosis to reimburse hospitals allows the insurance company to pay more for a CS and thus stimulates the CS rate in hospitals. Also, they predicted two challenges: opposition of O&G physicians and weak control over activity in maternity wards. In the healthcare administrators’ opinion, the way to implement such intervention would be to introduce financial incentives to physicians who perform vaginal births, accompanied by clearer indications for CSs, and mandatory clinical audit undertaken by independent evaluators because there is a lot of variability and abnormality. […] unfortunately, we do not have information collected in the information system to correlate the data.

Goal setting for CS rates

Support for this intervention was limited among the O&G physicians because they considered that it would limit their clinical autonomy and add additional pressure on medical practice, and that they would receive penalties for not reaching targets. To be supportive, medical doctors suggested providing bonuses for physicians to perform more vaginal deliveries. An additional challenge identified was the organisational culture in Romania: this includes the widespread practice of giving birth with the O&G physician who has monitored the pregnancy; hospitals permitting performance of unnecessary CSs; and the limited authority of hospital managers over medical decisions. An O&G physician claimed: it is about the lack of confidence of the woman in the health system; they trust the doctor rather the health system, if the patient would belong to the hospital and not to a certain doctor, the process would be different. Finally, women’s opinions and preferences for CS births are also considered a challenge, despite women identifying the opinion of the O&G physician as the most important factor.

Healthcare administrators agreed that goal setting for CS rates at the hospital level may be effective in reducing the number of CSs but identified that this would need to be implemented together with other interventions, such as economic disincentives for medical doctors or hospitals not being reimbursed for CSs above the target.

Policies that limit financial or legal liability in the case of litigation of healthcare professionals or organisations

There was consensus that doctors fear malpractice lawsuits and ask for better regulatory frameworks regarding legal liability in the medical profession. Under the current legal system, providers can be prosecuted under the civil code or, more often, under the criminal code, even before the case is judged by the College of Physicians. Also, no formal risk management strategy exists at the hospital level to reduce the likelihood of a negligence lawsuit. In the absence of these strategies, O&G physicians reduce the risk of a malpractice lawsuit by accepting all CS births on maternal request.

Additional challenges related to implementation of the interventions

The respondents also identified several challenges related to the current performance of the health system, which might also hinder successful implementation of interventions if they are not adequately addressed. These included women’s experience and perception of lower quality of care for vaginal birth; out-of-pocket payments for prenatal examinations and childbirth preparation; a lack of O&G physicians with expertise and skills in managing complicated vaginal births; a lack of anaesthesiologists to administer epidural analgesia for labour and vaginal birth; and family doctors not providing antenatal care.

Healthcare providers and administrators also recognised that an increased role for midwives during pregnancy and birth would increase women’s education, decrease fear and contribute to lower CS rates in hospitals. However, O&G physicians admitted that the measure would be controversial among their peers because of a reluctance to confer more duties on midwives.

Finally, some women who had previous vaginal births said that they [O&G physicians and nurses] only give orders and yell while women are in such great pain and they talk about us patients as if we were not there; mainly the nurses, all you hear is ‘wait, be good’. This might indicate that the rights of women to dignified, respectful healthcare through pregnancy and childbirth are not systematically respected in the context of the Romanian health system, including a lack of continuous one-to-one intrapartum support.

Discussion

The research outlined in this paper was an initiative of the partnership between the Ministry of Health of Romania, the WHO Country Office in Romania, the WHO Regional Office for Europe and WHO headquarters as a result of the current political concern and will for action to reduce unnecessary CSs. This is among the first experiences in Romania to conduct and use qualitative research on this topic, and it improves understanding of local determinants of the high CS rates in the country. Importantly, this research includes women and healthcare providers’ views of the acceptability of potential interventions to reduce the use of CSs, as well as considerations for their implementation, based on the opinion of healthcare providers and administrators.

The findings of this study, in line with the current literature,17 suggest that values and preferences for birth and for information vary among women, and that changes in women’s opinions throughout pregnancy are shaped by interactions with the community, O&G physicians and the health system. Women’s willingness to learn more is a major facilitator for implementation of educational interventions, resulting in more women being empowered in the decision-making process. In contrast to other studies, which have shown women’s suspicions that health professionals manage information provision to encourage women to prefer a particular mode of birth,18 19 in Romania, women place the greatest trust in O&G physicians. As found elsewhere,18 a potential barrier to effective implementation of educational interventions would be women’s reluctance to use educational materials that might increase their anxiety or reduce the number of contacts with healthcare providers. This fear has been identified by WHO, which recommends that the content of educational materials should not provoke anxiety, while being consistent with advice from healthcare professionals, and should provide the basis for more informed dialogue with them.17

Healthcare providers’ beliefs, values and preferences have crucial influence on decisions about the mode of birth. Providers’ opinions, together with health system and organisational factors, need to be considered carefully in the design and implementation of interventions.20 21 O&G physicians in Romania believe that the current CS guideline provides some safety in case of malpractice accusation, which is attributed to the fact that the College of Physicians and the court review whether O&G physicians followed the indications of the guideline. However, consistent with the results of the Ionescu et al study22 and most of the literature worldwide,9 fear remains and influences decisions about mode of birth. Although in some countries some anecdotal reports reveal that lawsuits by women submitted to unnecessary CSs have started to emerge, in this research respondents always referred to lawsuits from complications associated with vaginal birth. O&G physicians fear complications that may occur during vaginal birth and recognise that they need more training and practice on instrumental vaginal deliveries, VBAC and TOLAC.23 O&G physicians request better regulatory frameworks for legal liability of the medical profession. Without addressing their concerns, it will not be possible to optimise the use of CS in a sustainable manner. Also, aligned with published evidence,21 dysfunctional teamwork within the medical profession, marginalisation of midwives, power relationships and tension and a lack of communication between cadres may represent barriers to the reduction of CS rates.

Although joint implementation of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and a mandatory second opinion for CS indication can be effective in reducing unnecessary CSs,11 24 in the context of Romania, opposition from O&G physicians should be expected. An entry point might be implementation of in-service training, which has been identified as a need in this research; this could help healthcare providers to incorporate the recommendations of the national guideline into their usual practice.10 In addition, there is a need for better regulation of the provisions associated with the indication of CS on maternal request in the national clinical guideline, endorsed as secondary legislation by the Ministry of Health.

Equalising fees between vaginal delivery and CS has been proposed among the regulatory and financial strategies to disincentivise overuse of CSs.11 25 Healthcare administrators perceived that this would be effective if implemented together with goal setting for CS rates by means of economic disincentives for medical doctors and hospitals not being reimbursed for CSs above the target. These views are not a surprise, given the literature showing that financial incentives alone have little effect on CS rates.25 26 Equalising fees may find opposition among healthcare providers, with the view that vaginal delivery is insufficiently paid because it requires more time compared with a quick and efficient CS.21 In order to overcome these challenges, the identification of champions to promote the implementation of these recommendations may be useful.

Data collected from respondents also revealed several novel findings related to health system performance that need to be addressed if the national CS rate is to be reduced. Improvement of the quality of childbirth care, particularly for labour and vaginal birth, is crucial—including availability of pain relief for vaginal birth, continuous one-to-one intrapartum support by a companion of choice, positive and constructive communication and relationships with providers, and women’s need for emotional support.

In Romania no formal evidence is available on how well-informed patients in general or pregnant women are about their rights, and whether the available information is considered useful.27 The findings of this study show that the rights of women to dignified, respectful healthcare through pregnancy and childbirth might not be systematically respected; this deserves the attention of national and international institutions.

Lastly, momentum to address high CS rates is growing among professional societies and policymakers in the WHO European Region, which suggest synergies for joint initiatives, partnership, and actions,28 including in the case of Romania, as these findings demonstrate.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first time an in-depth and inclusive research study has been conducted in Romania to improve understanding of the drivers of increasing use of CS and to help with the design and implementation of strategies that are locally relevant, culturally accepted by women and providers and can be implemented effectively to reduce CS rates. However, the present research has some limitations. We did not include interviews with companions or the family of the pregnant women, so their opinions and views are not represented in our findings. Likewise, family doctors and other stakeholders were not included. Nevertheless, to a certain extent, their opinions have been captured through the women’s and healthcare providers’ discourses. Further, some healthcare providers refused to participate, although the research achieved saturation of the information.

Conclusion

In conclusion, multifaceted action tailored to Romanian determinants to address unnecessary CSs should include women’s empowerment through information with consistent messages that do not increase their anxiety. Training and management of complicated vaginal birth is necessary and could be an opportunity for the promotion of instrumental vaginal birth, TOLAC and VBAC, particularly among young O&G physicians working within a multidisciplinary team. Implementation of a mandatory second opinion and goal setting alone may not be effective in Romania. The introduction of financial incentives is a complex endeavour, due to current societal and healthcare organisation norms and practices. If implemented, it needs to be carefully crafted within the health system. Finally, an increase in the quality of care for labour and vaginal birth is paramount for any of the interventions considered to succeed. Further studies should assess the effect of multifaceted interventions in Romania.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NB led on conceptualising, coordinating the research, analysis and writing the manuscript. AL-G reviewed the interpretation of results and drafted the first draft of the manuscript with inputs of APB, DF and NB. DF was responsible for the data collection and analysis with guidance and inputs of NB. APB, CB and MG contributed substantial comments to the writing of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. NB accepts full responsibility for the work as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions or policies of the WHO.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The generic protocol was approved by the Research Project Review Panel of the United Nations Development Programme/United Nations Population Fund/United Nations Children's Fund/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, at the WHO headquarters Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research and the WHO Research Ethics Review Committee (protocol ID, 004571). Ethical approval was given by the scientifical committee of Centre for Health Policies and Services of Romania.

References

- 1. Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, et al. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One 2016;11:e0148343. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Souza J, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, et al. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes. The 2004-2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health BMC Med 2010;8:71. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002494. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . WHO statement on caesarean section rates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. Available: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/cs-statement/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 5. Macfarlane AJ, Blondel B, Mohangoo AD, et al. Wide differences in mode of delivery within Europe: risk-stratified analyses of aggregated routine data from the Euro-Peristat study. BJOG 2016;123:559–68. 10.1111/1471-0528.13284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zwecker P, Azoulay L, Abenhaim HA. Effect of fear of litigation on obstetric care: a nationwide analysis on obstetric practice. Am J Perinatol 2011;28:277–84. 10.1055/s-0030-1271213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin H-C, Xirasagar S. Institutional factors in cesarean delivery rates: policy and research implications. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:128–36. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000102935.91389.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sorrentino F, Greco F, Palieri T, et al. Caesarean Section on Maternal Request-Ethical and Juridic Issues: A Narrative Review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58:1255. 10.3390/medicina58091255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Betrán AP, Temmerman M, Kingdon C, et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet 2018;392:1358–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31927-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Opiyo N, Kingdon C, Oladapo OT, et al. Non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections: WHO recommendations. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98:66–8. 10.2471/BLT.19.236729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen I, Opiyo N, Tavender E, et al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;9:CD005528. 10.1002/14651858.CD005528.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . The Global Health Observatory: births by caesarean section (%). 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/68

- 13. Pyykönen A, Gissler M, Løkkegaard E, et al. Cesarean section trends in the Nordic Countries - a comparative analysis with the Robson classification. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:607–16. 10.1111/aogs.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National School of Public Health Management and Professional Development . Hospital performance indicators, . 2021. Available: http://www.drg.ro/index.php?p=indicatori&s=2009_performanta

- 15. Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, et al. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. BJOG 2016;123:667–70. 10.1111/1471-0528.13526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bohren MA, Opiyo N, Kingdon C, et al. Optimising the use of caesarean section: a generic formative research protocol for implementation preparation. Reprod Health 2019;16:170. 10.1186/s12978-019-0827-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kingdon C, Downe S, Betran AP. Women’s and communities’ views of targeted educational interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean section: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health 2018;15:130. 10.1186/s12978-018-0570-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frost J, Shaw A, Montgomery A, et al. Women’s views on the use of decision aids for decision making about the method of delivery following a previous caesarean section: qualitative interview study. BJOG 2009;116:896–905. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02120.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. David S, Fenwick J, Bayes S, et al. A qualitative analysis of the content of telephone calls made by women to A dedicated “Next Birth After Caesarean” antenatal clinic. Women Birth 2010;23:166–71. 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kingdon C, Downe S, Betran AP. Interventions targeted at health professionals to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e025073. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kingdon C, Downe S, Betran AP. Non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean section targeted at organisations, facilities and systems: Systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS One 2018;13:e0203274. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ionescu CA, Dimitriu M, Poenaru E, et al. Defensive caesarean section: A reality and a recommended health care improvement for Romanian obstetrics. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;25:111–6. 10.1111/jep.13025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crossland N, Kingdon C, Balaam M-C, et al. Women’s, partners’ and healthcare providers’ views and experiences of assisted vaginal birth: a systematic mixed methods review. Reprod Health 2020;17:83. 10.1186/s12978-020-00915-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Althabe F, Belizán JM, Villar J, et al. Mandatory second opinion to reduce rates of unnecessary caesarean sections in Latin America: a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2004;363:1934–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16406-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Opiyo N, Young C, Requejo JH, et al. Reducing unnecessary caesarean sections: scoping review of financial and regulatory interventions. Reprod Health 2020;17:133. 10.1186/s12978-020-00983-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lo JC. Financial incentives do not always work: an example of cesarean sections in Taiwan. Health Policy 2008;88:121–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vladescu C, Scintee SG, Olsavszky V, et al. Romania: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit 2016;18:1–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Montilla P, Merzagora F, Scolaro E, et al. Lessons from a multidisciplinary partnership involving women parliamentarians to address the overuse of caesarean section in Italy. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002025. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simionescu A, Marin E. Caesarean birth in Romania: safe motherhood between ethical, medical and statistical arguments. Maedica (Bucur) 2017;12:5–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization . European Health Information Gateway: obstetricians and gynaecologists, per 100 000 population. 2020. Available: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hlthres_130-obstetricians-and-gynaecologists-per-100-000/visualizations/#id=28115&tab=table

- 31. World Health Organization . European Health Information Gateway: midwives licensed to practice, per 100 000 population. 2020. Available: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hlthres_115-midwives-licensed-to-practice-per-100-000/visualizations/#id=28080

- 32. Dimitriu M, Ionescu CA, Matei A, et al. The problems associated with adolescent pregnancy in Romania: A cross-sectional study. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;25:117–24. 10.1111/jep.13036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stativa E, Rus AV, Suciu N, et al. Characteristics and prenatal care utilisation of Romanian pregnant women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2014;19:220–6. 10.3109/13625187.2014.907399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dorca V, Mihu D, Feier D, et al. Actualities and perspectives in continuous epidural analgesia during childbirth in Romania. Epidural Analgesia: Current Views and Approaches 2012:95–114. 10.5772/2167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.