Abstract

The winged helix transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 3γ (HNF3γ) is expressed in embryonic endoderm and its derivatives liver, pancreas, stomach, and intestine, as well as in testis and ovary. We have generated mice carrying an Hnf3g-lacZ fusion which deletes most of the HNF3γ coding sequence as well as 5.5 kb of 3′ flanking region. Mice homozygous for the mutation are fertile, develop normally, and show no morphological defects. The mild phenotype change of the Hnf3g−/− mice can be explained in part by an upregulation of HNF3α and HNF3β in the liver of the mutant animals. Analysis of steady-state mRNA levels as well as transcription rates showed that levels of expression of several HNF3 target genes (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, transferrin, tyrosine aminotransferase) were reduced by 50 to 70%, indicating that HNF3γ is an important activator of these genes in vivo.

Transcription factors control gene expression in adult liver and hepatoma cell lines. These factors contain various structural motifs to allow for high-specificity DNA binding; among them are the divergent homeodomain proteins hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α (HNF1α) and HNF1β; the winged helix proteins HNF3α, -β, and -γ; the leucine zipper proteins C/EBPα and -β; the orphan nuclear receptor HNF4; and the D site binding protein (DBP) (reviewed in references 5 and 32). Liver-specific gene expression cannot be achieved through the action of any individual transcription factor, because none of these factors is expressed exclusively in liver. When cis-regulatory elements of liver-specific genes were analyzed in detail, binding sites for multiple transcription factors were found. Therefore, the combinatorial action of the regulatory proteins most likely produces the stringency of hepatic gene expression.

The HNF3 proteins were discovered by their ability to bind to the promoters of the genes encoding α1-antitrypsin (α1-AT) and transthyretin (TTR) (8). Cloning of the cDNAs identified three HNF3 genes (HNF3α, -β, and -γ) in mammals (14, 15). The HNF3 genes are closely related to the Drosophila melanogaster gene forkhead, which is essential for the proper formation of the foregut and hindgut in flies (30). Therefore, it has been suggested that the HNF3 genes function in mammalian liver and gut development (15). This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the HNF3 genes are expressed very early during the formation of definite endoderm, from which liver and gut are derived (3, 19, 27).

During formation of the definite endoderm, HNF3β is activated first, followed by HNF3α, and finally HNF3γ (3, 19, 27). The three HNF3 genes have different anterior boundaries of expression in the definite endoderm, suggesting that they are involved in the regionalization of the primitive gut tube. In addition, HNF3β is expressed in the node, and HNF3α and HNF3β are both expressed in the notochord and floorplate (3, 19, 27). HNF3β is absolutely required for notochord and floorplate formation, because these structures are missing in embryos homozygous for a targeted null mutation in the HNF3β gene (2, 31). However, because of the early lethality of the homozygous mutant embryos, the role of HNF3β in gut and liver development has not yet been assessed.

It is our goal to test the hypothesis that the HNF3 proteins have an important function in endoderm development and hepatic specification. We have generated a mutation in the gene encoding HNF3γ (Hnf3g) via gene targeting as a first step towards this goal. This mutation deletes the entire DNA binding domain of the HNF3γ protein and is therefore considered a null allele. Here we discuss the phenotypic consequences of the mutation on embryonic development and hepatic function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene targeting.

Lambda phage clones containing the murine Hnf3g gene had been isolated from a mouse embryonic stem cell (strain 129) library previously (11). A gene targeting vector was constructed in the β-galactosidase-containing plasmid pHM3 (12). A 3.2-kb BglII-SmaI (position 417 in the HNF-3γ cDNA) fragment of the Hnf3g gene was used as the 5′ homology and cloned in frame to the lacZ gene of pHM3, while a 2.0-kb BamHI-XhoI fragment of the 3′ flanking region of the gene was used as the 3′ homology. Thereby an in-frame fusion was created between the amino-terminal 98 amino acids of the Hnf3g protein and the β-galactosidase protein, which deletes the entire DNA binding domain as well as the carboxy terminus of the HNF-3 protein. The targeting vector was linearized with NotI, and 20 μg of DNA was electroporated into 107 E14-1 embryonic stem cells (13). Stably transfected cells were isolated after selection in 250 μg of G418 (Gibco) per ml, and 130 clones were analyzed by Southern blotting for homologous recombination. A 2.2-kb XhoI-HindIII fragment (probe C in Fig. 1) located 3′ to the Hnf3g gene was used as an external probe for Southern analysis of DNA digested with EcoRI or HindIII. Positively targeted clones were confirmed with a probe fragment encoding the neomycin phosphotransferase gene (data not shown). ES cells from the two correctly targeted clones were injected into blastocysts derived from C57BL/6 mice. Blastocysts were transferred to pseudopregnant NMRI females, and chimeric offspring were identified by the presence of agouti hair. Chimeric males were mated to C57BL/6 females to obtain ES-derived offspring that were analyzed by Southern blotting of tail DNA to identify the heterozygous (Hnf3g+/−) mutants. Heterozygotes were mated inter se to generate mutant (−/−) mice. Embryos and mice were also genotyped by PCR with three primers: Hnf3g 5′ (TCCCAAGCTTGGGCACTGGTGGCCA), Hnf3g 3′ (GTGGCAGCTGTAGTGGTGGCAG), and lacZ (CGCCATTCGCCATTCAGGCTGC). PCRs were carried out for 30 cycles (94°C, 30 s; 70°C, 40 s; 72°C, 60 s) in a buffer containing 1.5 mM MgCl2. The wild-type allele produced a band of 511 bp, and the targeted allele produced a band of 326 bp.

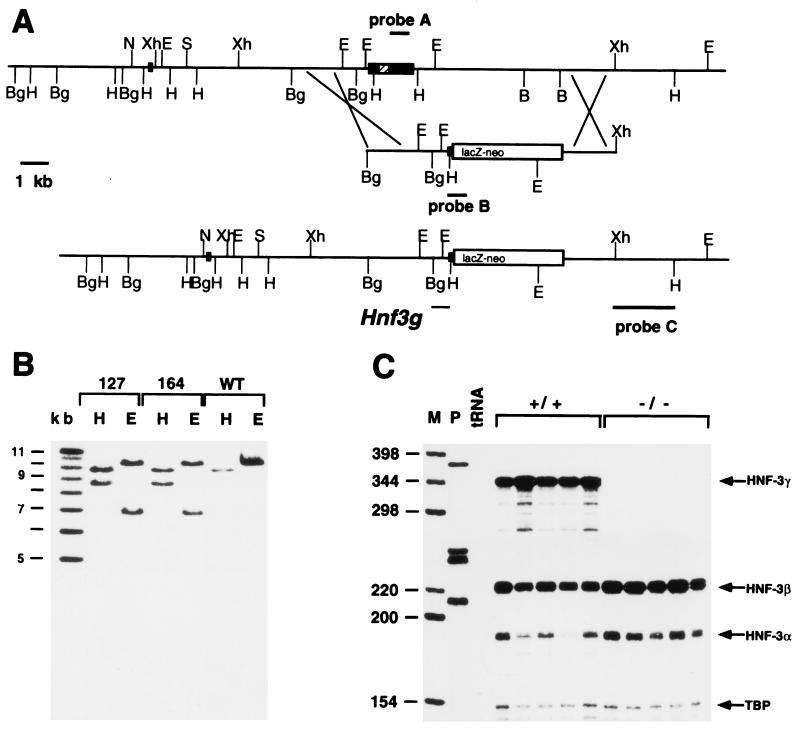

FIG. 1.

Targeting strategy for Hnf3g inactivation. (A) (Top line) Gene structure of the Hnf3g locus. (Middle line) Targeting vector used for homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. (Bottom line) Gene structure of the targeted allele. Probes A, B, and C are referred to in the text. B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NotI; S, SalI; Xh, XhoI; lacZ-neo, fusion gene encoding β-galactosidase and neomycin phosphotransferase. (B) Southern blot analysis of the correctly targeted ES cell clones (heterozygous for the Hnf3g mutation). DNA of wild-type and heterozygous ES cell clones was digested with HindIII (H) or EcoRI (E), size fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nylon membrane, and hybridized with probe C. (C) RNase protection analysis of 40 μg of total liver RNA isolated from wild-type (+/+) or homozygous mutant (−/−) mice. M, marker lane; P, undigested probes; tRNA, control. Protected fragments for HNF3γ, HNF3β, HNF3α, and TATA-box binding protein (TBP) are labeled with arrows.

β-Galactosidase staining.

Embryos (E14.5) were dissected in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and the extraembryonic membranes were saved for DNA preparation and genotyping by PCR. The embryos were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the embryos were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated in 15% sucrose at 37°C. After 4 h, the embryos were transferred to a solution of 7% gelatin–15% sucrose and incubated at 37°C overnight. The embryos were then embedded in 7% gelatin–15% sucrose, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −20°C. Ten-micrometer sections were obtained on a cryostat and incubated in staining solution for 2 days at 37°C. The staining solution consisted of 4 mM K3(Fe(CN)6), 4 mM K4(Fe(CN)6), 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 0.01% Na-deoxycholate, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside per ml. Sections were briefly (30 s) counterstained in eosin, dehydrated, embedded, and photographed.

RNA analysis.

Total RNA from adult tissues was isolated after homogenization in guanidinium thiocyanate (6). RNA was separated in formaldehyde-containing agarose gels for Northern analysis as described previously (1). Hybond N filters (Amersham) were hybridized in a mixture of 50% formamide, 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 50 mM Na phosphate at pH 6.5, 8× Denhardt’s solution, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.5 mg of total yeast RNA per ml with the probes indicated according to reference 26.

RNase protection analysis was carried out as follows. Antisense RNA probes were synthesized in the presence of 25 μCi of [α-32P]UTP at 800 Ci/mmol and 4 μM UTP. The probes were subsequently purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, followed by two precipitations with 2 M NH4 acetate and 2.5 volumes of ethanol. The RNA samples were dried under vacuum and resuspended in 30 μl of a hybridization buffer {80% deionized formamide, 40 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid); pH 6.4], 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA} containing 100,000 dpm of each probe. The samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min and then incubated at 54°C overnight. Unhybridized probes were digested through addition of 0.3 ml of RNase buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA) containing 4 μg of RNase A per ml and 1,000 U of RNase T1 at room temperature for 1 h. The RNases were hydrolyzed at 37°C for 15 min after addition of 4.5 μl of 10-mg/ml proteinase K. The samples were extracted once with phenol-chloroform, and the aqueous supernatant containing the double-stranded RNA was precipitated with 1 ml of ethanol after addition of 5 μg of tRNA. The precipitate was collected through a 15-min centrifugation step. The pellets were washed in 70% ethanol and dissolved in a loading buffer containing 50% deionized formamide and 5 mM EDTA. The RNA fragments obtained were separated on denaturing 6% acrylamide gels, and the radioactive bands were visualized by autoradiography. The probes used for Hnf3a, -b and -g (probe A in Fig. 1) were described previously (11). Two fragments (154 and 338 bp) of the ubiquitously expressed gene for TATA-box binding protein (28) were subcloned and used as templates for the synthesis of a control probe. Northern blot filters as well as dried RNase protection gels were exposed to phosphor storage screens, and the resulting signals were quantified on a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

Nuclear run-on transcription assay.

Nuclei were prepared from the livers of 8-month-old males (three Hnf3g−/− mutants and three wild-type littermates) according to the method of Marzluff and Huang (17) after perfusion with ice-cold 0.14 M NaCl–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). Nuclear transcription activity was determined by measuring the incorporation of [α-32P]UTP and with 2 × 107 nuclei per reaction. Nascent transcripts were isolated (4) and hybridized to filter-bound cDNAs for mouse albumin, glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), tyrosine-aminotransferase (TAT), transferrin (Tf), and phosphoenolpyruvate-carboxykinase (PEPCK). Filters were washed to high stringency, and signals were quantified with a phosphorimager.

RESULTS

Gene targeting of Hnf3g.

In order to investigate the potential role of the winged helix transcription factor HNF3γ in endoderm development, we generated mice lacking a functional product of this gene by homologous recombination. The Hnf3g locus had been cloned previously from a 129Sv mouse strain genomic library (11). We constructed a targeting vector that deletes the entire winged helix DNA binding domain and carboxy-terminal region of the protein and that creates an in-frame fusion with a lacZ-neo fusion cassette. Because Hnf3g is expressed in embryonic stem cells (11), we utilized a promoterless targeting construct to enrich for homologous recombinants. This strategy is based on the fact that random integration of a promoterless neomycin resistance cassette will only rarely result in neomycin-resistant ES cell colonies, whereas targeted integration into the actively transcribed Hnf3g locus will produce neomycin-resistant colonies. The complete targeting strategy is depicted in Fig. 1A.

After electroporation and selection of embryonic stem cells, 130 stably transfected neomycin-resistant ES cell clones were obtained. We analyzed these clones by probing of Southern blots with a probe fragment not contained within the targeting vector and found that two clones had undergone homologous recombination (Fig. 1B). Both targeted clones were shown to be without unintended rearrangements at the Hnf3g locus by Southern blot analysis with several probes located 5′, 3′, and internal to the targeting vector (data not shown) and thus contain the Hnf3g− allele as schematized in Fig. 1A. Germ line chimeras and mice heterozygous for the Hnf3g mutation were obtained for both ES cell lines as described in Materials and Methods. In all parameters studied, both lines gave identical results, indicating that the phenotype observed is indeed due to the targeted mutation in the Hnf3g locus and is not caused by another, unrelated mutation derived from the ES cell clones. In the following discussion, we have combined the results obtained from both lines.

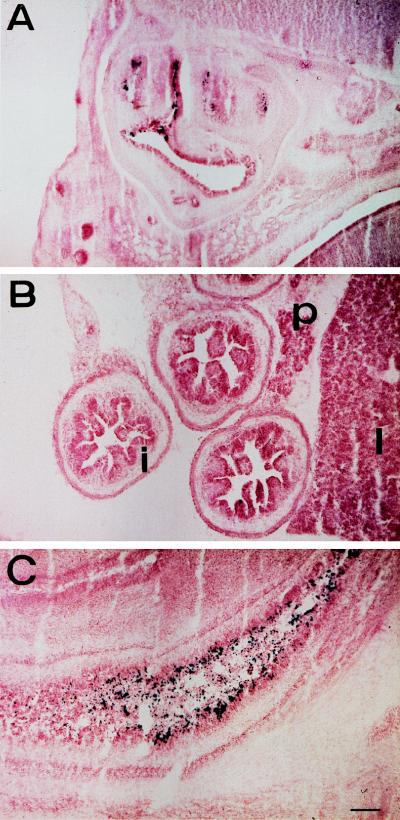

We expected that replacement of the HNF3γ coding region with the lacZ gene would result in expression of β-galactosidase in all cells that normally express HNF3γ. When staining embryos and adult tissues (data not shown) or frozen sections (Fig. 2), we were surprised by the lack of β-galactosidase activity in liver, stomach, pancreas, and small intestine (Fig. 2B). Expression of β-galactosidase in the nasal and colonic epithelia, on the other hand, correlates well with that of HNF3γ (Fig. 2A and C). Through the analysis of cis-regulatory elements of HNF3γ in transgenic mice and cell lines, we have recently shown that an important cis-regulatory element resides 3′ of the HNF3γ coding region (9). Deletion of 5 kb of 3′ flanking region removes these cis-regulatory elements and silences the Hnf3g-lacZ allele in liver, pancreas, stomach, and small intestine. This observation also indicates a complex regulation of the Hnf3g locus, because transcription of the locus in colonic and nasal epithelia is regulated independently of the other sites of expression.

FIG. 2.

The 3′-flanking region of the HNF3γ gene is required for β-galactosidase expression in small intestine, pancreas, and liver. Embryos (E14.5) were obtained from matings between heterozygous parents, genotyped by PCR, and stained for β-galactosidase activity as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Staining in the nasal epithelium. (B) No staining is detectable in the small intestine (i), pancreas (p), and liver (l). (C) A section through the colon of the same embryo shows strong staining in the colonic epithelium, but not in mesenchyme. The scale bar represents 100 μm.

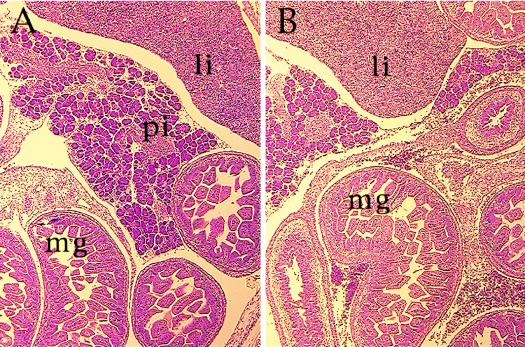

Because HNF3γ had been suggested to function in the regionalization of the primitive gut tube, we investigated the development of the liver, pancreas, stomach, and intestine. Mice heterozygous for the HNF3γ mutation were crossed inter se, and embryos were collected from various stages of gestation. As shown in Fig. 3, no morphological abnormalities were observed in the liver, pancreas, and gastrointestinal tract of the HNF3γ−/− embryos. Thus, by morphological criteria, HNF3γ is not required for specification of endoderm-derived organs.

FIG. 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of Hnf3g−/− embryos. Embryos (E16.5) were obtained from matings between heterozygous parents, genotyped by PCR, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained. A wild-type embryo (A) and homozygous mutant embryo (B) of the same litter are shown. li, liver; pi, pancreatic islet; mg, midgut.

HNF3α and -β mRNAs are increased in the liver of HNF3γ−/− mice.

In light of the normal development of the HNF3γ−/− embryos, we wanted to ascertain that we had indeed generated a null allele of Hnf3g. Therefore, we analyzed HNF3γ transcripts in total liver RNA obtained from adult wild-type or homozygous mutant mice by RNase protection analysis. As shown in Fig. 1C, HNF3γ mRNA was absent from the livers of mutant animals, proving that we had generated a null allele for Hnf3g. No HNF3γ mRNA was present in any other organs analyzed (data not shown).

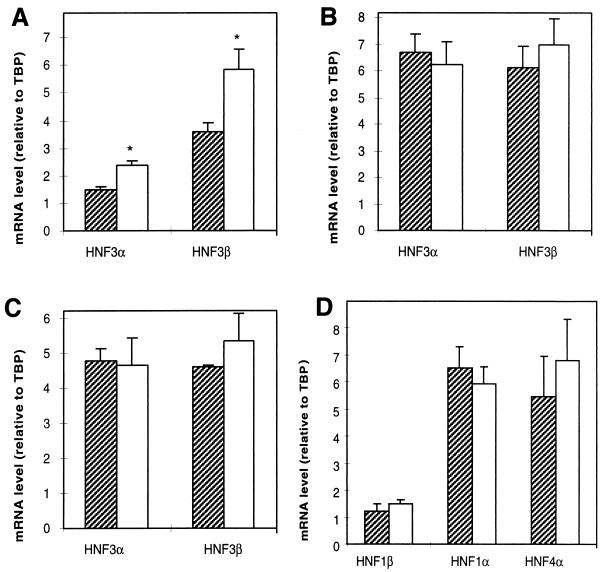

In several knockouts of transcription factors belonging to gene families, targeted mutation of one gene led to an upregulation of other members of the same gene family, demonstrating the existence of regulatory networks between these transcription factors (10, 25). Therefore, we investigated the mRNA levels of the two other members of the HNF3 gene family, genes coding for HNF3α and HNF3β, by RNase protection analysis. As shown in Fig. 1C and 4A, the two mRNAs are upregulated in the mutant livers by approximately 60%. We wanted to investigate whether this up-regulation of HNF3α and HNF3β occurs only in the liver or in all tissues where the three HNF3 genes are coexpressed. Therefore, we compared HNF3α and HNF3β mRNA levels in stomach and colon of wild-type and HNF3γ−/− mice (Fig. 4B and C). In contrast to the situation in liver, the expression of HNF3α and -β is not altered in these tissues. This finding indicates that HNF3γ functions as a negative regulator of Hnf3a and Hnf3b in liver. Although our genetic approach does not distinguish between direct and indirect effects, it seems possible that in the case of Hnf3b, HNF3γ would act through the previously identified HNF3 binding site within the promoter (22). The observed derepression of Hnf3a and Hnf3b could also contribute to the mild phenotype effect observed in the Hnf3g mutant animals.

FIG. 4.

mRNAs for HNF3α and HNF3β, but not HNF1α, HNF1β, and HNF4, are upregulated in liver from Hnf3g−/− mice. (A) RNase protection analysis of HNF3α and HNF3β mRNA levels in liver RNA (40 μg) from wild-type (striped bars) and Hnf3g−/− (open bars) mice were normalized to those of TATA-box binding protein (TBP). Radioactive bands were quantified by phosphorimager analysis. Values are means ± standard errors (n = 5), and differences between wild-type and −/− mRNA levels were statistically significant (P < 0.05 for HNF3β; P < 0.01 for HNF3α) by Student’s t test. (B) RNase protection analysis of HNF3α and HNF3β mRNA levels in stomach RNA (40 μg) from wild-type (striped bars) and Hnf3g−/− (open bars) mice. Values are means ± standard errors (n = 3). (C) RNase protection analysis of HNF3α and HNF3β mRNA levels in colon RNA (40 μg) from wild-type (striped bars) and Hnf3g−/− (open bars) mice. Values are means ± standard errors (n = 3). (D) RNase protection analysis of 40 μg of total liver RNA isolated from wild-type (striped bars) and Hnf3g−/− (open bars) mice was performed with probes specific to HNF1α, HNF1β, and HNF4 and with TBP as a control. Signals were analyzed as by phosphorimager and normalized to TBP (×0.1 for HNF4α). Values are means ± standard errors (n = 5).

Aside from the upregulation of HNF3α and HNF3β mRNAs, an additional possibility for explaining the mild effect on the hepatic phenotype of the Hnf3g−/− mice is increased activity of the other liver-enriched transcription factors, notably the divergent homeodomain proteins HNF1α and HNF1β and the orphan nuclear receptor HNF4. This is plausible in light of the fact that the promoters and enhancers of many genes encoding liver-enriched proteins contain binding sites for several of these transcription factors (5). In order to address this possibility, total liver RNA from wild-type and Hnf3g−/− mice was analyzed by RNase protection assay for the expression of HNF1α, HNF1β, and HNF4. As shown in Fig. 4D, no significant differences were observed.

Liver-specific transcription is impaired in Hnf3g−/− mice.

When heterozygous animals of mixed background (129Sv × C57BL6) were crossed inter se and the offspring were genotyped at 4 weeks of age, no deviation from the expected Mendelian distribution was observed (49:105:47; +/+: +/−:−/−). No differences in the growth characteristics or final weight attained between wild-type and mutant animals were found. Biochemical analysis of plasma obtained from mutant mice did not reveal any differences in glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, and amino acids (data not shown). Histological sections of the liver, stomach, and intestine (the major sites of Hnf3g expression) of adult wild-type and mutant animals were investigated, but no morphological differences were found (data not shown). In addition, both male and female mutants were found to be fertile, although HNF3γ mRNA had been demonstrated in ovary and testis (11, 15).

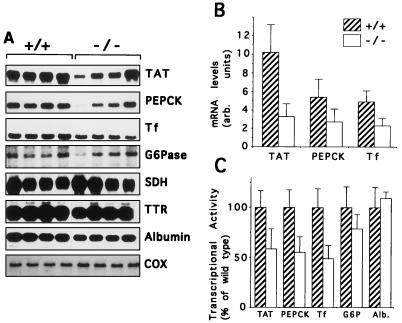

A large number of liver-specific or liver-enriched genes which contain HNF3 binding sites have been described previously (reviewed in references 5, 7, 23, and 32). We wanted to know which of these genes are regulated by HNF3γ in vivo. In order to address this question, we isolated total liver RNA from adult wild-type and mutant animals and analyzed the steady-state mRNA levels of various HNF3 targets by Northern blotting and RNase protection analysis. A subset of these results are shown in Fig. 5A, demonstrating that mRNA levels for TAT, Tf, and PEPCK are reduced in Hnf3g−/− mice, while those of G6Pase, serine dehydratase (SDH), TTR, and albumin are not changed. The magnitude of the effect was estimated after quantification of the signals on a phosphorimager and was approximately 70% for TAT and 50% for both PEPCK and Tf (Fig. 5B). Despite the decrease in mRNAs for gluconeogenic enzymes, the Hnf3g−/− mice are euglycemic under normal feeding conditions or when fed a carbohydrate-free diet (data not shown). In addition, we analyzed steady-state mRNA levels for glycogen synthetase, carbamoylphosphate synthetase, α1-AT, and apolipoproteins AI, AII, and E, but found no difference from controls (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of steady-state mRNA levels and transcription rates of potential HNF3γ targets in liver. (A) Total RNA (10 μg) from livers of wild-type (+/+) or homozygous mutant (−/−) mice was separated on denaturing agarose gels, blotted onto nylon membrane, and hybridized to the probes indicated. Cytochrome c oxidase (COX) served as a loading control. (B) The filters obtained in panel A were quantified by phosphorimager analysis, and the mRNA values (arbitrary units [arb.]) were expressed relative to those for COX. Values are means ± standard errors (n = 4); differences between wild-type and −/− mRNA levels were statistically significant (P < 0.05) by Student’s t test. (C) Nuclear run-on transcription assays were performed with liver nuclei isolated from wild-type (hatched bars) and homozygous mutant (open bars) mice as described in Materials and Methods. The signals obtained were quantified by phosphorimager analysis, normalized to those of glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase, and expressed as percentages of wild-type levels. Values are means ± standard errors (n = 3); differences between wild-type and −/− mRNA levels were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for TAT, PEPCK, and Tf by Student’s t test.

Alterations in steady-state mRNA levels can be caused by changes in the rate of mRNA synthesis or degradation. In order to investigate whether the observed reductions in steady-state mRNA levels were due to a reduced hepatic transcription rate, we performed nuclear run-on transcription assays to estimate transcriptionally active complexes. As shown in Fig. 5C, the reduced mRNA levels for TAT, PEPCK, and Tf are indeed caused by a decrease in the transcription rate of these genes. Thus, although many transcription factors have been shown to bind to the promoters and enhancers of these genes (16, 20, 21), HNF3γ is an important factor in their regulation.

DISCUSSION

HNF3γ regulates liver-specific gene expression.

Mice carrying a null mutation of the gene encoding the winged helix transcription factor HNF3γ exhibit a surprisingly mild phenotype, considering the early embryonic activation of the Hnf3g gene (19). A subset of liver-enriched transcripts which had been shown to be regulated by the HNF3 proteins through in vitro DNA binding or transfection assays was reduced in the mutant livers, an effect which is due to decreased transcriptional activity of the corresponding genes. The absence of a decrease in albumin, α1-AT, and other hepatic mRNA levels could possibly be explained in part by compensatory binding of the HNF3α and HNF3β proteins, the levels of which are increased in the Hnf3g−/− mice. This notion is supported by competition studies with hepatoma cells (29), which showed that overexpression of the DNA binding domain of HNF3β, which was used to titrate all HNF3 activity, led to a decrease in the mRNA levels for albumin, TTR, Tf, PEPCK, and aldolase B of up to 95%. Alternatively, these genes may be redundantly regulated by a combination of liver-enriched and ubiquitous transcription factors, any one of which might play only a minor role in its regulation. A similar observation has been made by Pontoglio and coworkers in the case of gene targeting of HNF1α (24), where many of the previously known HNF1 targets identified in vitro were not altered in the mutant animals.

Why are there three HNF3 genes?

Since the expression domain of HNF3γ in the endoderm-derived tissues is contained within those of HNF3α and HNF3β, the question arises of why has HNF3γ been retained through evolution? One possibility was raised by the original observation of Lai et al. (15) that the HNF3 proteins have distinct binding affinities with respect to the sites contained in the TTR promoter in vitro, suggesting that the HNF3 proteins could be regulating different subsets of genes. Here we have shown that removal of the HNF3γ protein influences some, but not all, of the known HNF3 targets in vivo. One could envision that the down-regulation of HNF3α and HNF3β and the concurrent up-regulation of HNF3γ during late embryonic development cause a shift in the occupancy of HNF3 sites, thereby fine-tuning the transcriptional control in the liver. In this context, it is interesting to note that the HNF3 proteins have been suggested to permit gene activation of their target genes by remodeling of the chromatin structure (18). The proposed shift in HNF3 binding, which occurs relatively late in hepatic development, could thus facilitate the late (perinatal) activation of the gluconeogenic enzymes.

HNF3γ mRNA has been shown to be expressed from E8.5 onward, first in the invaginating hindgut and ventral endoderm and subsequently in all endoderm-derived tissues posterior to the liver and stomach. Based on this expression pattern, it was suggested that HNF3γ could function in the regionalization of endoderm-derived tissues and, specifically, in the differentiation of the liver, stomach, and small and large intestine (19). Through ablation of HNF3γ function by targeted mutagenesis, we have clearly demonstrated that HNF3γ by itself is not required for embryonic development and morphogenesis. A possible explanation for this normal embryonic phenotype is suggested by the observation that the other members of the gene family, Hnf3a and Hnf3b, are upregulated in the Hnf3g−/− mice. This indicates that HNF3γ acts, directly or indirectly, as a repressor of these genes. Alternatively, the upregulation of Hnf3a and Hnf3b in the liver might be due to an as yet unknown compensatory mechanism which allows the mice to survive in the absence of HNF3γ protein.

In summary, the predominant role of HNF3γ lies far down in the hierarchy of transcription factors in the direct control of a subset of the genes encoding liver-specific enzymes. Since many genes expressed in the endoderm or endoderm-derived tissues have binding sites for several of the hepatocyte-enriched transcription factors, it is not too surprising that loss of a single factor, as shown for HNF3γ and, previously, HNF1α (24), is well compensated for. In order to uncover potential additional functions of HNF3γ, future studies combining the mutations for all three HNF3 proteins (tissue specific or inducible for HNF3β) will be needed to define in more detail the role of the HNF3 proteins in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to J. Blendy, P. Monaghan, and F. Tronche for comments on the manuscript. We thank S. Ridder, H. Kern, W. Fleischer, E. Schmid, and A. Sukman for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SFB 229, the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, the European Community (grant BI02-CT93-0319), the McCabe Foundation, and the Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Disease at the University of Pennsylvania (P30 DK50306).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alwine J C, Kemp D J, Stark G R. Method for detection of specific RNAs in agarose gels by transfer to diazobenzyloxmethy-paper and hybridization with DNA probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5350–5354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ang S L, Rossant J. HNF-3 beta is essential for node and notochord formation in mouse development. Cell. 1994;78:561–574. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang S L, Wierda A, Wong D, Stevens K A, Cascio S, Rossant J, Zaret K S. The formation and maintenance of the definitive endoderm lineage in the mouse: involvement of HNF3/forkhead proteins. Development. 1993;119:1301–1315. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cereghini S. Liver-enriched transcription factors and hepatocyte differentiation. FASEB J. 1996;10:267–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa R H. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/forkhead protein family: mammalian transcription factors that possess divergent cellular expression patterns and binding specificities. In: Tronche F, Yaniv M, editors. Liver gene expression. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1994. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa R H, Grayson D R, Darnell J E., Jr Multiple hepatocyte-enriched nuclear factors function in the regulation of transthyretin and α1-antitrypsin genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1415–1425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiemisch H, Schütz G, Kaestner K H. Transcriptional regulation in endoderm development: characterization of an enhancer controlling Hnf3g expression by transgenesis and targeted mutagenesis. EMBO J. 1997;16:3995–4006. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hummler E, Cole T J, Blendy J A, Ganss R, Aguzzi A, Schmid W, Beermann F, Schütz G. Targeted mutation of the CREB gene: compensation within the CREB/ATF family of transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5647–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaestner K H, Hiemisch H, Luckow B, Schütz G. The HNF-3 gene family of transcription factors in mice: gene structure, cDNA sequence, and mRNA distribution. Genomics. 1994;20:377–385. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaestner K H, Montoliu L, Kern H, Thulke M, Schütz G. Universal beta-galactosidase cloning vectors for promoter analysis and gene targeting. Gene. 1994;148:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kühn R, Rajewski K, Müller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science. 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai E, Prezioso V R, Smith E, Litvin O, Costa R H, Darnell J E., Jr HNF-3A, a hepatocyte-enriched transcription factor of novel structure is regulated transcriptionally. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1427–1436. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai E, Prezioso V R, Tao W F, Chen W S, Darnell J E., Jr Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 alpha belongs to a gene family in mammals that is homologous to the Drosophila homeotic gene fork head. Genes Dev. 1991;5:416–427. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Hanson R W. Regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) gene transcription. Mol Cell Biochem. 1991;104:89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marzluff W F, Huang R C C. Transcription of RNA in isolated nuclei. In: Hames B D, Higgins S J, editors. Transcription and translation: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1985. pp. 89–129. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPherson C E, Shim E Y, Friedman D S, Zaret K S. An active tissue-specific enhancer and bound transcription factors existing in a precisely positioned nucleosomal array. Cell. 1993;75:387–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80079-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monaghan A P, Kaestner K H, Grau E, Schütz G. Postimplantation expression patterns indicate a role for the mouse forkhead/HNF-3 alpha, beta and gamma genes in determination of the definitive endoderm, chordamesoderm and neuroectoderm. Development. 1993;119:567–578. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nitsch D, Boshart M, Schutz G. Activation of the tyrosine aminotransferase gene is dependent on synergy between liver-specific and hormone-responsive elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5479–5483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nitsch D, Schütz G. The distal enhancer implicated in the developmental regulation of the tyrosine aminotransferase gene is bound by liver-specific and ubiquitous factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4494–4504. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pani L, Quian X, Clevidence D, Costa R H. The restricted promoter activity of the liver transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 3β involves a cell-specific factor and positive autoactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:552–562. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.2.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philippe J, Morel C, Prezioso V R. Glucagon gene expression is negatively regulated by hepatocyte nuclear factor 3β. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3514–3523. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pontoglio M, Barra J, Hadchouel M, Doyen A, Kress C, Bach J P, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 inactivation results in hepatic dysfunction, phenylketonuria, and renal Fanconi syndrome. Cell. 1996;84:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudnicki M A, Braun T, Hinuma S, Jaenisch R. Inactivation of MyoD in mice leads to up-regulation of the myogenic HLH gene Myf-5 and results in apparently normal muscle development. Cell. 1992;71:383–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90508-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruppert S, Boshart M, Bosch F X, Schmid W, Fournier R E K, Schütz G. Two genetically defined trans-actin loci coordinately regulate overlapping sets of liver-specific genes. Cell. 1990;61:895–904. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki H, Hogan B L. Differential expression of multiple fork head related genes during gastrulation and axial pattern formation in the mouse embryo. Development. 1993;118:47–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura T, Sumita K, Fujino J, Aojama A, Horiskoshi M, Hoffmann A, Roeder R G. Striking homology of the “variable” N-terminal as well as “conserved core” domains of the mouse and human TATA-factors (TFIID) Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3861–3865. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallet V, Bens M, Antoine B, Levrat F, Miquerol L, Kahn A, Vandewalle A. Transcription factors and aldolase B gene expression in microdissected renal proximal tubules and derived cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1995;216:363–370. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weigel D, Jürgens G, Küttner F, Seifert E, Jäckle H. The homeotic gene fork head encodes a nuclear protein and is expressed in the terminal regions of the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1989;57:645–665. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinstein D C, Ruiz i Altaba A, Chen W S, Hoodless P, Prezioso V R, Jessell T M, Darnell J E., Jr The winged-helix transcription factor HNF-3 beta is required for notochord development in the mouse embryo. Cell. 1994;78:575–588. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaret K S. Molecular genetics of early liver development. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:231–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]