Abstract

This research focuses on resilience and sustainable development in the tourism sector during the Covid-19 pandemic, using Pattaya - a renowned beach destination in Thailand – as the studied context. Since 2020, the pandemic has significantly impacted the tourism sector and its supply chain. The consequences include the stagnation of tourism and hospitality services and other economic activities due to lockdown measures and other restrictions. To investigate Pattaya's resilience in the face of these challenges, and post-pandemic recovery, this research adopted the conceptual framework on economic resilience and tourism recovery proposed by McCartney et al. (2021), as a theoretical lens to analyse events in Pattaya. The qualitative research method was employed, using in-depth interviews with public and private stakeholders, such as local authorities, large and small hotels, tourism business agencies and relevant organisations. The results show that the tourism industry, similarly to other sectors, was adversely affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, and the slow implementation of strategies proved inadequate in coping with the uncertainty. Local entrepreneurs require clearer and more supportive measures to reopen their businesses and resume economic activities.

Keywords: Sustainable tourism, Resilience model, Covid-19, Destination support, Pattaya, Thailand

1. Introduction

Overtourism, sustainable tourism and resilience have been the terms in vogue in the last couple of decades, with the recent addition of Covid-19. In spite of many projects about sustainable tourism development, Thailand and its tourism policies have consistently prioritised numbers over quality, with tourist arrivals taking precedence over other key performance indicators. Since 1997, arrivals have increased constantly, reaching nearly 40 million in 2019 [1] before the pandemic struck, a number drastically reduced to 6 million the following year, when most arrivals were recorded before the border closures and lockdown measures imposed in late March 2020.

From March 2020 to June 2021, the country was closed to visitors. In July 2021, the Thai government launched the Phuket Sandbox, a reopening programme for foreign visitors, limited to 15,000 tourist arrivals per month [2]. Since November 2021, there has been an expectation that tourist arrivals would reach pre-pandemic levels by 2023 or 2024, at the earliest [3]. Thus, tourism activities that rode the pandemic are likely to struggle for another couple of years before returning to some form of normality [[4], [5], [6]], a prediction developed from short-term risks inherent in recent outbreaks of other infectious diseases like Ebola, Zika or SARS, for instance in the works by Bloom and Fan et al. ([7,8]).

Pattaya welcomes a large number of tourists each year and has its ongoing programme of sustainable tourism. Over the years, this well-known resort has experienced overtourism, sustainable tourism, climate change and Covid-19. Until the 1950s, Pattaya was a small fishing village, visited mostly by holidaymakers from Bangkok. In the early 1960s and until 1975, the Vietnam War (1964–1973) created Pattaya as a city of Rest and Recreation (R&R) for American GIs, creating a plethora of bars and bar girls [9], transforming this sleepy fishing village through a series of disordered tourism-led developments until after the end of the conflict. By the mid-1970s, the fishing village connotation had disappeared under an array of hastily-built hotels and bars. The nascent leisure industry in Pattaya attracted migrant workers from impoverished areas of Thailand, mostly from the north and northeast regions. The tourism activities brought social and environmental issues, such as high cost of living, water pollution, grey (informal) economic activities, de facto corruption and health-related issues, namely sexually-transmitted diseases ([10,11]). As Smith describes [9], by the early 1990s the seedy atmosphere of the Vietnam War era continued till the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the Walking Street and many of the A-Go-Go bars and pubs targeting mostly Western visitors. Chinese tourists also come in tour groups or as Foreign Independent Travellers (FIT), the latter being wealthier and less keen on established paths [12], with Pattaya adding more family-oriented activities, such as the creation of a zoo, golf courses and temple visits [13], to the range of leisure activities. A major change has been recorded in the demographics of the visitors: from mainly Western visitors up to the 1990s, now Russian, Indian, Japanese and Korean, and most of all, Chinese nationals, form the major tourism groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Numbers of tourist arrivals to Thailand, by country.

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 4,636,298 | 7,936,795 | 8,757,646 | 9,806,260 | 10,535,241 | 10,997,338 |

| Japan | 1,267,886 | 1,381,702 | 1,439,510 | 1,544,442 | 1,656,101 | 1,806,438 |

| Korea | 1,122,566 | 1,373,045 | 1,464,200 | 1,709,265 | 1,796,426 | 1,890,973 |

| Russia | 1,606,430 | 884,136 | 1,090,083 | 1,346,338 | 1,472,789 | 1,483,337 |

| India | 932,603 | 1,069,422 | 1,194,508 | 1,415,197 | 1,598,346 | 1,996,842 |

Source: Authors – adapted from data of the city data platform, Thailand.

The Covid-19 pandemic severely affected Pattaya, causing many establishments to put pubs and bars up for sale or rent. From January 2021, Pattaya hotels started requesting government assistance for subsidies [14] like (a) Social Security Fund, for government support during enforced lockdowns; (b) holiday period for electricity bills; (c) debt and interest extension.

Moreover, the Chinese government prevented its own citizens from travelling abroad during the pandemic [15], resulting in a substantial loss of income for businesses that traditionally catered to Chinese tourists as a major class of travellers [16]. Thus, the only tourists visiting Pattaya were mostly domestic Thai visitors who came in small numbers and only for brief excursions. Even though Pattaya reopened along with the rest of the country on 1st November 2021, the restriction on the consumption of alcohol, first introduced in April 2020, was still in place, effectively preventing bars and pubs in Pattaya from operating at pre-pandemic levels [17]. At the time of writing (May 2022), Thailand had almost completely revoked all the Covid-19 measures that had curtailed tourist arrivals for the previous two years. From 1st May 2022, the country only required a full vaccination, as well as registration with Thailand Pass, and comprehensive travel insurance covering up to USD 10,000 [18]. From 1st July 2022, only a vaccination certificate was required, a requirement waived from 1st October 2022 onwards.

Furthermore, the Russia-Ukraine war that started in February 2022 has led to more negative consequences not only for the large number of Russian nationals living in Pattaya but also by preventing the arrival of Russian tourists, one of the major foreign tourist groups. The block of SWIFT accounts put a stop to financial transactions from Russian banks, further undermining Pattaya's local economies. In 2022, Pattaya confirmed the ability for big chains, especially in the hospitality business, to survive, while small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were the most seriously impacted, with closures affecting roughly 80 percent [19] of the tourism and hospitality industry. Consequently, thousands of workers in those industries were laid off, many of whom were forced to return to their hometowns in north and northeast Thailand to resume their former occupations as farmers.

As yet, the social impact of big crisis on tourism in Pattaya has not been investigated, and only the fate of the sex workers of Pattaya has been studied [20]. Although the Covid-19 pandemic is considered a specific event and has currently subsided, it exemplifies the common nature of major crises that create a significant impact on tourism at destinations. To date, there has only been a handful study regarding the long-term potential impact of major crises on key tourism destinations, particularly Pattaya. While the topic would be certainly interesting in many angles, this paper focuses on destination management in times of crisis, and an analysis of the Covid-19 pandemic and its consequences over the economic and social fabric. In fact, Pattaya has middle- and long-term issues, which will severely impact its beach destination positioning. Climate change has brought high tides reaching the road immediately behind the beach ([21,22]) and the subsequent coastal erosion and increased ocean levels are now forcing Pattaya to look at survival strategies. The omnipresent pollution detracts from the resort's natural beauty [23].

In this study, the model of resilience support, originally envisaged by Martin and Sunley [24], and later adjusted by McCartney et al. [25] for the context of Macao, has been adopted as a theoretical framework for Pattaya. Rather than focusing strictly on economic resilience like the original model, however, this study embraces governmental policies and tourism and hospitality associations planning, to establish how the different sectors understand the events around the Covid-19 pandemic and the efficacy of the relevant measures. Therefore, the research objectives are to analyse the business strategies of tourism and hospitality services and describe the kind of support structure, employed collectively in order to survive the impact of Covid-19, and also outline the future placement of Pattaya as a tourism destination. The tourism stakeholders were further questioned about what enhancements need to be put in place to make Pattaya resilient to any further disruptions that may happen in the future, in order to create the determinants of resilience for long-term shocks and stressors for the locality.

Based on the aforementioned, the study proposes the following research questions:

-

1)

What are the collective business strategies adopted by tourism and hospitality businesses in Pattaya to overcome the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

2)

What kinds of support structure is needed by tourism and hospitality organisations and activities in order to sustain long-term shocks and stressors for a destination such as Pattaya?

-

3)

What is the future placement of Pattaya as a tourism destination, based on the current social and economic situation?

-

2

Literature review

1.1. Butler cycle and tourism destination

Butler [26] introduced to academic literature the concept of life cycle for a tourism destination, with its five levels of exploration, involvement, development, consolidation and stagnation. Exploration remains the early level for a destination, when sporadic visitors discover a place, which is off the beaten track, and from this stage, we pass to the second stage of involvement, as local communities begin to develop tourism services, still targeting a limited number of visitors. With the development stage, actors bigger than the local community develop the necessary tourism services aimed at a larger number of tourists. Apart from services and attractions already in place, other man-made features are built or imported in order to attract more tourists. As consolidation follows development, the highest level of tourism activities is reached, but the rate of increase reaches a plateau, with tourists outnumbering local residents. In the stagnation phase, the visitor numbers reach a peak and this leads to social, economic and environmental problems. In this fifth and final phase, two options are considered viable, resulting in rejuvenation of the destination if changes and improvement have been implemented, or leading to its decline.

1.2. Pattaya, butler cycle and sustainability

As Butler's resort cycle became widespread, and discussed in more recent years [[27], [28], [29]], it was applied to Pattaya as well, in the variant known as the Beach Resort Cycle, as envisaged by Smith [30] and considered as an historical account of Pattaya development up to the early 1990s. Smith created a tourism development model more partitioned than the previous Butler's cycle. It identified a separation between the recreation business district and the commercial business district, labelling Pattaya as a resource in decline, with considerable environmental issues such as pollution and social problems connected to prostitution and related economic issues. For the next twenty years, Pattaya was not discussed in the tourism literature, and was analysed [31] from an administrative aspect, as the destination was actually subjected to various organisations responsible for the destination management, from local authorities to central agencies. But the original social issues already noted by Smith [30] continue to dominate academic research about Pattaya: prostitution, mostly from a social perspective or the relationship between sexual activities and HIV spreading [[32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]] but very few studies investigate sex as a tourism attraction within Pattaya, which is a well-documented motivation for Thai and overseas visitors alike ([38,39]). The other issue is the pollution affecting Pattaya, which has been one of the major points of attention in the last decade ([22,[40], [41], [42]]). Although these studies consider the environmental impact of issues like E. coli (for its obvious implications for water quality and human health) and microplastics, no consideration is given to how pollution may render other tourist destinations more attractive than Pattaya.

1.3. Resilience and its structures

Resilience can be defined as “Returning to the reference state (or dynamics) after a temporary disturbance” [43]. As far as tourism studies are concerned, the concept of resilience dates to mid-2000 [43], but it has appeared in ecology since the early 1970s. This term has become a hot topic within tourism research in the last couple of decades [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]], even within the Southeast Asian region ([49,50]). As tourism activities work and overlap with ecology and natural systems, the concept of socio-ecological resilience has come to the fore ([43,[51], [52], [53], [54], [55]]), as a field where human behaviours and activities are subject to the changing environment and other shocks. Fiksel [56] was among the early group of scholars dealing with the approach to sustainability as a system from an ecological perspective. For Fiksel, sustainable development can be achieved through collaboration across disciplines, improved communication with diverse groups and interrelation of different phenomena. He also emphasises the need for policies that recognise the interconnectedness of ecological systems and the importance of including mechanisms for dialogue among various groups, industry, government and academia. In the final analysis, Fiksel argues for a model of sustainability based on a holistic approach that brings together multiple perspectives and stakeholders.

The adaptive cycle has been introduced [[57], [58], [59], [60], [61]], in which key stages of the cycle postulate how a system (including both ecosystems and human social systems) moves through stages of exploitation (or growth, r), conservation (or consolidation of resources, K), release (or disruption of energy and resources, Ω) and reorganisation (or recovery, α) The forward loop moving through the exploitation stage is considered an expansive period, whereas the backward loop moving through the release stage is considered a period of contraction. From the forward loop, the system can move in any direction, including a cyclical process through to consolidation and growth, or conservation and reorganisation, without entering a disruptive release phase. Indeed, resilience theory emphasises adaptability and innovation in the face of disturbances [62], as adaptive capacity, where the actors within the system develop and enhance their abilities to changes [59].

It is also clear that the creation of a resilience system rests on three levels, firstly, it depends on people, and the human capital is a two-way dialogue: the organisation understands the needs of its employees, and tries to help both economically and psychologically, while empowering employees to promote and support the organisation, therefore fostering a growth in intellectual capital and individuals’ accountability. Secondly, from a process point of view, Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) focuses on both the supply chain risks, and operational risks such as financial risks, focused on the operational risk of any organisation in case of crisis. Business Continuity Management (BCM) has been considered as a subset of ERM, for its potential role in dealing with sudden disruptions in supply management, more than a total collapse of the entire system. Thirdly, the collaboration with external organisations through various networks reinforces the organisational resilience, as partnerships prevent disruptions in supply chain, for instance.

The prime actors for resilience are individual, institution and organisations, as well as culture and society [43], although, there is a multilevel perspective (MLP) framework to understand management of tourism destinations in coping with drastic changes, [63].

The Individual resilience includes personal control, the individual's ability to implement the necessary requirements to reach their goals; coherence, requiring a plan in place for individuals to see clearly what lies ahead and be able to restart the process; correctness, or the ability of individuals for mutual assistance in order to create a support system [[64], [65], [66]]. Organisational resilience requires a system in place which creates awareness of problems, as well as a workforce well equipped to deal with disasters or emergencies, and an organisational structure flexible enough to deal with such emergencies [[67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73]] [[67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73]] [[67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73]].

1.4. Determinations of resilience

The last element to consider is destination resilience, divided into socio-ecological and socio-political resilience [[74], [75], [76]]. The former can be considered as the measures adopted at local level in order to restore the destination to a pre-disaster situation, especially important after natural catastrophes like earthquakes and tsunamis. For the latter, the importance of regulations and policies, as well as support from national agencies, remains fundamental in order to restore or regenerate tourism destinations to the new exigencies dictated by natural disasters ([77,78]). The participation of local and national agencies also raises the issues of local communities' role within the decision-making process, as national agencies may contrast with the opinion of local groups, as well as veiled or overt interests bringing poor implementations of the regulations and disaster management measures. For the specific case of Phuket, in the south of Thailand, after the December 2004 tsunami, it was remarked that all the various levels of the community were involved in order to restore the island's tourism services [43].

With these different types of calamities, the ability to adapt varies according to the various actors: passing from a high level of adaptability for tourists, to a mid-level of adaptability for travel agents, and with hotel operators and destination in general more prone to such variations [79]. In this sense, we need to introduce the Determinants of Resilience, which at least have made their presence with [24], and they can be considered as “The factors that shape regional economic resilience and how far and in what ways those factors change over time” [24]. They worked over given determinants that support resilience within an economic support framework, identifying five factors, namely: 1) Tourism Industrial and Business Structure; 2) Labour Market Conditions; 3) Agency and Decision-Making; 4) Financial Arrangements; 5) Government Arrangements.

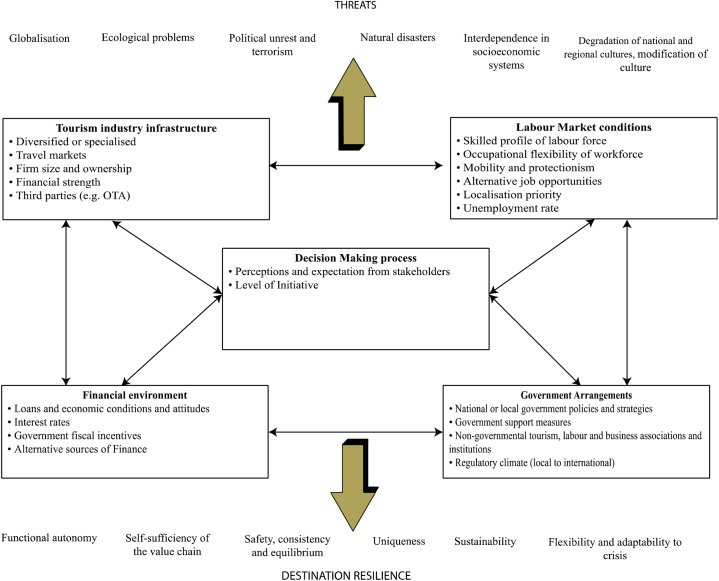

In recent times, the city of Macao has adopted such a framework for its tourism industry [25] (see Fig. 1), and with minor adjustments mostly related to terminology, this framework has been adopted for Pattaya as a beach destination. The amended framework has also determined the questions to be asked of the various stakeholders. In fact, the relative resilience determinants could ensure that threats have been absorbed within the system, as well as offering a destination resilience toward those threats. As the Macao model was designed for the Covid-19 pandemic, it has been extended in order to cover other possible shocks and stressors, as applied by Traskevich and Fontanari [76].

Fig. 1.

Resilience determinants.

Source: The framework drawn by authors, applies from McCartney et al. [25] and Traskevich and Fontanari [76].

The above structure in Fig. 1 has to be coordinated between the various agencies and stakeholders, and needs to be sufficiently adaptable to deal with mutated exigencies and stressors that might not be present when the model is being implemented. While no specific regulations seemed to exist at local or national level to sustain the impact of Covid-19 or long-standing stressors, the opportunity presented itself to look for both the solutions to the pandemic issues – economic, social or as they might be – as well as what sort of solutions were considered both for post-pandemic and as destination of the future, and the kind of support presently available and required for future needs.

2. Methods

In order to delve into the applicable approaches of how Pattaya managed its crises, key tourism stakeholders, such as local authorities, hotel and tourism business organisations, would be the most appropriate parties to shed light on the topic. Underpinning this research using the constructivist paradigm, in which individuals construct their own understanding of the world and reality through a process of interpretation [80] this study employed qualitative research approaches, due to their “richness” in data [44,81] to explore different views and perceptions of these stakeholders, leading to practices, solutions and desirable measures that enhanced stakeholders’ opportunities to become more resilient during the crisis.

A qualitative approach helps researchers gain comprehensive and in-depth insights into the situations [82], as well as exploring the experiences, perceptions and management of stakeholders during the Covid-19 pandemic. The constructivist/interpretivist research paradigm was chosen as it acknowledges the existence of the multiple realities concerning the phenomenon [83]. In this case, these realities could be derived from the diverse views and perspectives of tourism stakeholders facing the situations at hand.

This study employed the purposive sampling method which is useful for understanding the needs, interests and incentives of the selected people when nominating participants [82]. In agreement with Ritchie et al. [84], we consider the subject matter and impacts are covered. In this respect, we recruited the private and public representatives from tourism and hospitality business and activities in Pattaya. Through the collaboration with one of the national agencies, devoted to sustainable tourism development in Thailand, the researchers initially identified eighteen representatives, while considering possible alternative figures within the same organisations. The participants are in senior positions within their organisations and range in age from 45 to 60. However, due to the impending Pattaya governor elections and changes in organisational representation, the researchers were able to interview only sixteen individuals, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interviewees as Representatives from the relevant agencies.

| Sector | Representatives from the agencies below. | Sex | Code name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public |

|

F | In1 |

|

M | In2 | |

|

M | In3 | |

|

M | In4 | |

|

F | In5 | |

| Private |

|

M | In6 |

|

M | In7 | |

|

M | In8 | |

|

M | In9 | |

|

F | In10 | |

|

F | In11 | |

|

M | In12 | |

|

M | In13 | |

|

M | In14 | |

|

M | In15 | |

|

M | In16 |

The semi-structured, in-depth, one-on-one interviews were conducted throughout the research process, from April to July 2022. Although on-site, face-to-face interviews had been originally planned, most participants stated a preference for online interviews due to Covid-19 concerns, resulting in four face-to-face interviews and twelve Zoom interviews.

A list of questions was prepared beforehand and circulated to the interviewees in advance. Before the interviews started, participants were reminded about the scope of the interview, research ethics on human subjects, such as their authorisation to continue with the interview, and their permission to have the interview recorded. Each of the sixteen interviews lasted between 50 and 70 min. Data saturation was successfully reached. The questions were related to impacts of the Covid-19; individual participant's business strategies before and after the pandemic; how they reacted to the crisis and to government's rescue policies; and what were their perceptions for the future of Pattaya. We also employed the ‘member checking’ method [85] to validate the results.

Since the interviews were conducted in Thai, the interview questions originally drafted in English were translated into Thai by the researchers. Recordings of the interviews were afterwards transcribed verbatim by external collaborators in July 2022, with some of these interviews reported in this paper.

A preliminary coding of the transcriptions was conducted using MaxQDA software. Each of the sixteen interviews was further analysed using key concepts from the framework, with preliminary concepts further coded into themes according to the coding procedures outlined by Saldaña and Omasta ([86,87]). The results were then analysed based on the research questions and resilience determinants detailed earlier, but also denoting more generic questions about the Covid-19 impact, as the major concern.

3. Results

The primary consequence of Covid-19 is the reduction in tourism and hospitality service providers, such as hotels, restaurants, and tourism activities in general, which has had a downstream impact on related services like food supplies [88]. The strategies and support measures employed by Pattaya to address Covid-19 and its prospects as a tourism destination are reported based on the frequency of mentions and the number of participants discussing the topic, as outlined below.

3.1. Collective business strategies to overcome the Covid-19 impacts

Over the two years of the pandemic, the tourism and hospitality organisations employed several response strategies to cope with its challenges, with some response strategies displaying common features among a number of companies [89]. As for business resilience in Pattaya, predictably the major business chains were able to adapt and mitigate the turmoil by accessing their liquidity reserves and other resources, as in the following:

-

a)

Utilising government financial supports

As the coronavirus struck, the most felt consequences were a decrease in tourism and hospitality activities, with cities turning into ghost towns. Many hotels stopped operating and others still closed permanently. Only an estimated 20 percent [90] of hotels in operation pre-Covid were known to have survived the pandemic. But a high degree of inequality was observed. The major hotel chains were able to operate in large measure thanks to Covid-19 support regulations, apportioned on the basis of capacity (room numbers) and staff, effectively negating eligibility for small and medium hotels (In1, In6, In7, In9). Most of this latter group closed down due to financial constraints and insufficient staff levels.

“… Bank won’t release the soft loan to small or medium hotels to pay for employees' salaries; small or medium hotels can’t continue to ask the government for soft loans. Bank will release soft loan to a large company, which has a good track record. But small is not good, …

So, it’s difficult to reopen the business. Probably won’t be able to reopen and may even go bankrupt.” (In1, Female)

-

b)

Adjust business model

Resilience can create the necessary structure — economic, social, governmental altogether — to allow the tourism destination to adapt to changes or cope with the sudden interruption of tourism activities, which are impossible to predict at the time of implementation [46]. The tourism and hospitality industry also apply some strategies to deal with the pandemic. Four business strategies emerged from the interviews, to reveal the rapid modification of structures to help businesses cope with the situation.

-

1)

Targeting a new market: The new focus was mainly domestic tourists as mentioned in the following excerpt:

“Would you call it relief? For example, hotels must adapt. We have many problems. Some hotels have never catered for this many Thai guests. Before Covid, the ratio was 70 foreign tourists to 30 Thai tourist. As of today, our guests are almost 100 percent Thai. We must seriously adapt our marketing strategy to cater for domestic guests.” (In7, Male)

-

2)

Diversifying the products

Some hotels became pet-friendly and started offering shampoo and grooming services, while some restaurants began allowing pets in outdoor areas. This new kind of pet-friendly model was widely applied in many hotels, including the vulnerable SME hotels (In1, In2, In3, In4, In7). Additionally, shops and bars affected by night-time opening restrictions began operating as restaurants with delivery services (In2, In15, In16).

-

3)

Working hours extension

Pattaya tourism entrepreneurs asked for extended opening-hours, so the customers could spend longer during their visits (In2, In6, In7, In12, In15, In16).

-

4)

Price reduction

This was one of the ways to increase competitiveness, with five- or six-star hotels decreasing their room rates by as much as 50 percent, equalling rates offered by two- or three-star hotels (In2).

The large and SME entrepreneurs in Pattaya adjusted their business models to protect their comparative advantage, a business adaptation that quickly transitioned into a fast-coping mechanism. This supports what Butler [45] asserts, namely that resilience is not developed in reaction to a devastating situation but is developed over time from day-to-day operations. It is the innate resilience which pre-dated Covid-19, fortified by experiences of day-to-day problem management [91].

-

c)

Shift to digital platform

During the pandemic, the consumer goods and services (CGS) industry responded to the pandemic by shifting to digital means of communicating and delivering their products and services [92]. Content marketing became a crucial strategy for a return to competitiveness by embracing digital platforms and emerging technologies.

As the new route-to-market strategy, the Pattaya entrepreneurs also employed the content marketing on social media channels to communicate with customers, replacing pre-pandemic means of marketing. The interviewees stated that they made use of digital platforms as a significant tool, particularly in the operation of online travel agents (OTA). This method enables tourism service providers to reach directly to customers, as the customer-to-customer model (C2C) (In2, In3, In4, In6, In7).

“Today, hotels must have a department that they call a studio, a must have … The various sales agents of the past have gone. Nowadays we engage in direct marketing to customers. I think they call it C2C. Every day, we have to edit VDO clips, shoot food pictures, etc.” (In7, Male)

-

d)

Staff re-training and changing roles

The tourism and hospitality industry is one of the most labour-intensive, and consequently labour shortages present critical problems for the business. During the coronavirus pandemic, a great number of hospitality workers resigned and may never rejoin the sector, with serious consequences for the capacity of the hospitality business, particularly the wellness and spa sectors. Unlike the hotel industry, where staff can be employed on the basis of their theoretical knowledge, the wellness and spa industries require theoretical knowledge as well as practical experience of treatments and procedures [93]. People employed in these two hospitality segments must possess knowledge and sufficient levels of practical experience to create service values, in order to build customer satisfaction for the business. Faced with labour shortages, entrepreneurs had to resort to new methods to retain their employees during the pandemic (In1, In3, In7, In8, In13, In14). Businesses in Pattaya applied the retention strategy, through re-training of staff members; by brushing-up skills and imparting new knowledge and technology for the treatments. They also adjusted tasks and widened the range of activities to be performed by staff (In12, In15).

“Since we have lower numbers of staff and we have food delivery, which is a new service during Covid, our chef sometimes has to deliver food or pack lunchboxes.” (In15, Male)

“I asked my staff to keep the spa well-maintained, such as cleaning, fixing the place. Or sometimes, I re-train them to brush-up their knowledge to keep them on track.” (In12, Male)

3.2. Kinds of support structure that tourism and hospitality need to sustain the impacts

Resilience elements in the tourism and hospitality industries come from various types of support structures which potentially encourage resilience. During the crisis, the Thai government launched several initiatives to support tourism and hospitality. Pattaya, a self-governing city, obtained relief packages from the government and was able to offer soft loans and other tax relief measures to subsidise the local firms. Some companies were thus eligible for benefits from both sources. The type of support structures which emboldened the tourism business are:

-

a)

Several campaigns to stimulate travelers' demands

The Thai government introduced several campaigns to stimulate demand from domestic visitors and increase consumer spending, such as “We travel together” (Rao Tiew Duay Kan), “Happiness-sharing Trips” (Tiew Pun Suk) or “Half-Half” (Khon La Khrueng) [94]. Tourism's supply chain also benefited from the demand pushing [95].

The campaigns had a significant impact for businesses in Pattaya (In1, In2, In4, In5, In7, In8). Although local visitors usually travelled to Pattaya during the weekend or on long weekends, this was perceived as an improvement on a city that felt increasingly deserted. Moreover, the campaigns nourished the local supply chain.

“The greatest benefit for us has been the ‘we travel together’ campaign. Government subsidises 40 percent and it helps a lot. The campaign has already been launched four times. (In7, Male)

-

b)

Liquidity measures

The Thai government released a fiscal package worth THB 400 billion (USD 1.1 billion), consisting of soft loans, debt payment extensions, tax holidays and other funds to cushion economic hardship for affected households and firms [96]. Furthermore, the self-governing city of Pattaya granted a reduction in taxes payable on land and buildings for a period of two years, with only 10 percent of the total amount payable (In2, Male). All taxes could also be paid by quarterly instalments. Moreover, every household in Pattaya received a one-off cash grant of 2000 baht (USD 55).

Qualifying businesses in Pattaya were eligible for liquidity scheme payments from central government, but it was noted that the overall rescue package was insufficient for the city to bounce back to pre-pandemic levels (In1, In2, In5, In6). The participants also remarked that a more flexible approach in governing the relief measures would have better stimulated the economy, with other comments regarding the rejection of proposals from SMEs (In2, In5, In6, In7, In12, In14, In15).

“A soft loan helps a lot because the interest rate is quite competitive. After proposing a business plan and getting approval, the business will receive a lump sum to implement their plans. For example, a shop that previously operated as a spa salon now is a food shop, offering simple meals or individual dishes, including delivery service (In16, Male).

-

c)

‘Pattaya Move On’ as a sandbox

In July 2022 Thailand reopened its borders to foreign travellers by introducing the ‘sandbox policy’, starting with Phuket. When Pattaya applied for its own version of the ‘Phuket sandbox’, a number of considerations were taken into account. Whereas Phuket is an island, Pattaya, located on the mainland, was deemed difficult to isolate and challenging to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Moreover, Pattaya also suffers from image problems. A combination of these factors complicated the procedure for a Pattaya version of the ‘Phuket sandbox’. Reopening Pattaya entailed an online application for a ‘Thailand Pass’ before travelling, with evidence of vaccination certificates or proof of a negative coronavirus test. On arrival, visitors were required to quarantine in a Pattaya hotel for three days before continuing to inland destinations within a designated route. This programme was called ‘Pattaya Move On’ (PMO). Supported by Pattaya authority and the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT), the designated route programme included travelling from Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi Airport directly to Pattaya, designed to segregate visitors from local residents. The PMO measures were intended to keep Pattaya safe after reopening (In2, In3, In4, In6, In7, In9, In12, In15).

“Actually, now Pattaya can accept ‘Test & Go’, and it is a sandbox just like Phuket …. Chonburi province [Pattaya’s province] has prepared sufficient beds to manage an outbreak, with around 18,000 hospital beds and 6,000 hotel rooms capable of being converted into alternative quarantine facilities for the sandbox.” (In9, Male)

The PMO programme was well managed and allowed overseas visitors to remain in Pattaya for extended periods of time, supporting local businesses and their supply chains. However, it was short-lived because the rest of Thailand reopened in October 2022.

-

d)

Vaccines to restore confidence

Vaccination was hailed as a tool for recovery for its potential to protect communities through herd immunity. The worldwide rollout of mass inoculations would ensure the recovery of the tourism industry [97]. As elsewhere, in Pattaya mass vaccinations restored confidence in local people and visitors alike, and stimulated the economy. Thailand also offered a vaccine tourism package as a way of attracting visitors to the kingdom [98]. The city of Pattaya set up a vaccination policy, by buying and allocating Covid-19 vaccines to restore confidence in tourists (In1, In2, In3, In4, In6, In7, In12), taking the vaccination rate of Pattaya to over 70 percent (In2, Male) at the time of the interviews, in April–July 2022.

“Vaccinate people to protect and improve quality of life. We try to take care of the quality of life of people as much as possible … it is a fight against Covid … It has been so long since we have seen tourists, that I can barely think of anything else. Because people do not dare to go out …” (In2, Male)

The high vaccination rate was also an important factor for an approval of the PMO, which stood at more than 70 percent of the city's population, as mentioned earlier [99].

-

e)

SHA and SHA + to ensure health safety

In May 2020 the Thai government launched the Amazing Thailand ‘Safety & Health Administration’ (SHA) certificate, to indicate tourism entrepreneurs' readiness in improving products, services and sanitation measures. It required on-site staff to be inoculated against the Covid-19 virus. The SHA project combined public health safety measures and establishments' high-quality service standards to reduce the risk and prevent the spread of Covid-19, as well as improving Thailand's tourism products and service standards, to restore travellers' confidence for health and sanitation.

In November 2021, the SHA + standard, an upgraded version of SHA, was introduced. To get the SHA + certificate, staff of the on-site service provider must have been vaccinated to at least 70 percent of the full dose. Hotels and restaurants also followed the SHA or SHA + procedures in order to get the certificate and post on the easy-to-see point.

“We think about how to get the situation back, so we need to restore the confidence of tourists. So, health and safety are important. Then, we have SHA standard. Pattaya set up our standard to be SHA+, or perhaps SHA+++, or SHA Extra Plus. This means that the on-site service provider has to set up a requirement for firms to have at least 70 percent of the full dose vaccine to qualify for the certificate. This will eliminate the vaccine problem experienced by the private sector.” (In7, Male)

-

f)

Digital support

Following Singapore's initiative, the city of Pattaya set up a strategy to become a smart city, or ‘Neo Pattaya’ [100]. The government developed the digital infrastructure, conceptualised as an interconnection of different system collectives, including software, hardware, standards, the internet, platforms and human resources, very unlike standalone information systems [101]. The digital system fell somewhat short of its stated objectives, but there was a digital channel for communications. Moreover, Pattaya benefited from underground cables and digital facilities from the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) government project. (In2, In3, In4, In6, In7).

“Digital Platforms can help. Because the Pattaya city mayor tries to make Pattaya a Smart city, linking to tourism, OTA, hotel reservations, etc., making it more convenient and accessible for shopping. Easier to reach operators. Easier to order food. Easier to book hotels.” (In6, Male)

3.3. Future Pattaya

Among other connotations, for years Pattaya has been visualized as a flesh pot and cheap beach destination. Pre-Covid, Pattaya suffered from overtourism and the so-called ‘Zero-dollar tour’ syndrome, with package prices at below cost. Subsequently, Pattaya aimed for a smart city label and business hub for Eastern Thailand, following the EEC strategy. However, the pandemic dictated a re-think for the Pattaya of the future.

-

a)

Keep the old image

Debating the ‘old’ and ‘wannabe’ Pattaya, some participants admitted that the traditional image of Pattaya was indeed one of sleaze linked to the city's ‘sex industry’ [102] - a selling point that features on the itinerary of countless travelling groups. Thus, some interviewees wanted to preserve the old image of Pattaya, dating back to the end of the Vietnam war, with its sex connotations, pubs, A-go-go bars, ‘golden boy’ shows and nightlife, to stimulate tourism (In2, In6, In7, In8, In9, In11). However, they also noted the control measures, prevention programmes and education.

“Well, someone once suggested that we are a conservation city. It's the culture of Pattaya. We have already told you that Pattaya is a new city. We don't have a local culture. Everyone wants to preserve the culture, wants to preserve the local community. We will say that Pattaya is a conservation area for local communities. We don't have any culture, because we were born from GI soldiers who came to relax and drink beer at a Pattaya beach. (In7, Male)

-

b)

Cluster of activities

However, they also noted that clustering of activities may make Pattaya appealing to a different class of visitors. Family groups were a quality target class of visitors due to different ages, to enjoy diverse activities such as excursions to sacred sites, adventure, eco-tourism, spa and wellness (In1, In2, In3, In4, In5, In6, In12, In14).

Pattaya entrepreneurs and the TAT set up varied activities throughout the year before the pandemic, including beach jogging, seafood festivals, music on the beach, environmental activities like beach clearing, community events. To welcome these new target groups, however, Pattaya needed additional support from the local government, to enrich the range of facilities for tourists. Some ongoing infrastructure problems, involving roads and public services, were noted, which required to be solved, like accessibility for wheelchair users and senior tourists, as well as signs and safety walkways for the visually impaired.

While others advocated for novelty, on a par with destinations like the Maldives, to attract more foreign tourists, an image improvement was actually needed. The ensuing debates were lively, discussing how Pattaya as a tourism destination should aim for diversification, through government coordination (In1, In2, In3, In4, In6, In9, In12).

-

c)

Quality tourism

Niche market and quality tourists were proposed for the future, since pre-Covid Pattaya was affected by overtourism, mostly from tour groups, which resulted in congestion at beach areas and other tourist attractions. In this regard, it was felt that Pattaya needed a different focus, where quality tourists prevailed over quantity, as had been the case for decades. The opinions were expressed by participants from the public sector (In1, In2, In3, In4, In5). Besides an ability to forecast visitors’ needs and wants, it is also important to evaluate which class of tourists could be enticed to Pattaya all year round. Thus, a strategy was developed to target different nationalities and different tourist classes for year-round arrivals, in order to avoid seasonal overtourism.

It was also noted that medical and wellness tourism should be encouraged, given that Thailand has a sound knowledge in both modern and traditional medicine for therapy and rehabilitation, through accreditation with international hospitals and medical institutes. Moreover, the EEC would lend its support for the medical hub project because it is part of its strategies, in keeping with Pattaya re-inventing itself as a medical hub and wellness destination centre, as a source of knowledge and opportunities.

4. Discussion and conceptual implication

The empirical evidence provided in this article is preliminary and focuses on short-term response to the Covid-19 challenges for Pattaya, applying the resilience determinants’ framework proposed by McCartney et al. [25], to study Pattaya during the phases of its crisis management. The framework has proven to be useful with good determinants to help explain factors underlying resilience in Pattaya. We observed that resilience methods in Pattaya have common features with the study conducted in Macao [25], while also displaying some differences as follows:

-

a)

Financial situation: Comparing to Macao, Pattaya's tourism and hospitality industry was more fragile, particularly for SMEs, affected by liquidity problems which impaired their business operations. Unlike Pattaya, however, Macao's financial resilience was guaranteed by the government's high fiscal reserves, from taxes paid by the casino industry, sufficiently substantial to lubricate the local industry throughout the lockdown period. This implies the level difference the institutional resilience [43] between the two destinations.

-

b)

Labour conditions: Pattaya's tourism industry was labour-intensive. During the crisis, most of the workers left their jobs to return to their hometowns in the north and northeast of Thailand, unlike workers in Macao, mostly local residents who remained in their jobs in the city. Macao's labour market was stable during the pandemic and the unemployment rate was as low as 3.5 percent during the first half of 2020 [25]. The difference in geographical boundaries and landscape poses limitations and challenges for Pattaya, as labour market was much more volatile and the labour flows could happen easily, leading labour to either return to their hometowns or transition to other industries [103,104].

-

c)

Pattaya Governance: The respective administrations of Pattaya and Macao are different. The self-governing status makes Pattaya more flexible and versatile, with the ability to generate resilience by its own resources. Furthermore, the mayor of Pattaya is an elected official, with the political ability to intervene in all policy processes. This reflects the strong force on the resilience system in the institutional level [43].

-

d)

Tourism Infrastructure: Pattaya's tourism business model is diversified and can be modified in line with the changing situation. Unlike Macao, its tourism authorities had limited evolution on diversification due to the city's governance model, an executive-led, top-down planning, and relationship between bureaucratic patrons and entrepreneurs [105]. The dominance of the casino industry may have curtailed Macao's progress for other tourism opportunities. Moreover, Pattaya's private sector enjoys a strong corporation and networking with local politicians, potentially for greater public and private collaboration, as a means to foster resilience. However, Macao's top-down form of government can exert leverage over the private sector and limit public engagement.

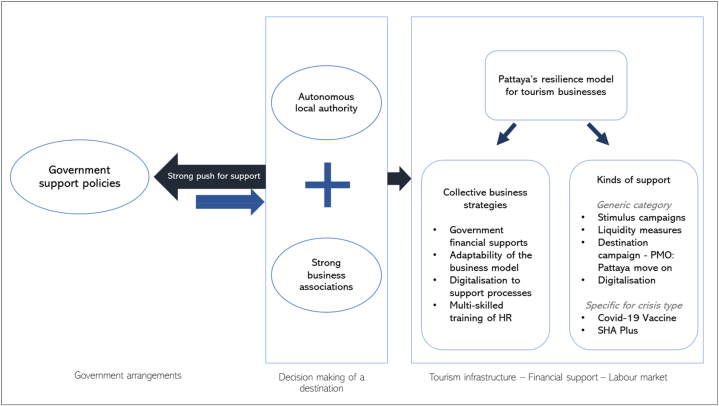

From the analyses, Pattaya developed a unique resilience model, marked by diversification and the implementation of technology, bolstered by government support measures. This comprehensive business model and external factors have greatly assisted the city don its path to resilience and recovery as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Pattaya's resilience model.

Source: created by authors

Fig. 2 illustrates the factors that contribute to Pattaya's resilience during Covid-19, mapping key determinants with factors derived from McCartney et al. and thoroughly explained in the previous section. Nonetheless, it is important to mention that within the aspect of infrastructure, financial support, and labour market, it has been observed that Pattaya possesses a decent tourism industry infrastructure, notably in terms of its travel market, specialised tourism and hospitality sectors, strong trade associations, and the potential for tourism product diversification (e.g., sports, wellness). On the other hand, the framework omits the contextual and unresolved tension and inequality faced by SMEs tourism businesses that experienced a much more significant impact from the long-term crisis. The government's financial incentives and economic support measures, including soft loans and tax-related initiatives, aimed at facilitating business operations, did not effectively reach the SMEs due to regulatory constraints within the relief measures. This situation is not found to be a major problem in the case of Macao or large businesses but poses common problems for many destinations where the central government's social and financial cushions are not effectively implemented to the grassroot [25]. This notion is of paramount importance as it provides an important message for policy implementation during a crisis, especially of the middle to long-term nature. Large businesses in the tourism sector demonstrate significant strength and can deploy innovative processes and agile business ideas, such as the adoption of digital technology to reduce human interaction in services or food delivery. They could retain and upskill their employees to work cross functions. Some of them exhibit inherent resilience as they have been able to adapt to the ‘new normal’ on a daily basis.

The framework also underscores the pivotal role of key decision-makers who actively secured essential resources for the destination's survival during crises, making them a crucial factor in the destination's resilience. Both the local authority and the Pattaya business association, representing institutional forces [43], demonstrated proactive initiatives by advocating for government support and regulatory approvals for alternative campaigns aimed at mitigating losses. Without their proactive efforts, the destination would have faced even greater challenges.

In addition to the business-derived resilience model presented above, it is worth highlighting an issue that can significantly influence the future trajectory of Pattaya's tourism recovery. The future image of Pattaya is a matter of concern for multiple stakeholders. The contrasting images of its past (Pattaya with a nightlife connotation) in comparison to its current and future development (Pattaya as a hub for diversified tourism activities) may lead to a mixed perception of the destination. This mixed perception could pose challenges in attracting the desired high-quality tourist segments that the city aims to attract. These conflicting images represent an important, unresolved issue that warrants discussion for policy implementation within the context of destination image and destination development.

5. Conclusion, contribution and limitation

The Covid-19 pandemic displays numerous of the characteristics detailed by the British naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) in his Natural Selection [106]: only the strongest organisations will survive, usually comprising internationally- or economically-empowered actors which, unlike smaller players, have the financial and organisational capabilities to survive closures and income reductions for longer periods of time. Covid-19 is an extraordinary and unusual incident. Unlike financial crises, some private agencies can continue with their business activities if they are only lightly affected by the crisis. However, the pandemic led to lockdown and restriction policies which grounded all activities to a halt. With these points being mentioned, however, this study also uses the Covid-19 crisis to illustrate the nature of consequences that could arise from long-term and high-impact crises affecting a tourism destination. It also provides two perspectives that can be applied generically on how a destination can become resilient, based on business strategy and policy support.

As for preliminary conclusions, it can be stated that Pattaya can recoup its losses if and when the rest of the world re-opens for travel and business in order to return to pre-pandemic capacity and profitability. However, these aspirations must be viewed in the context of organisations favouring a fresher image for Pattaya, including the city's “red-light” district, and they will not consider continuing with Pattaya's reputation of past decades. In terms of organizational capacity, tourism and hospitality entities exhibited a higher level of preparedness in handling abrupt changes, shocks and stressors compared to local administrations, which were less equipped to manage sudden shifts.

Furthermore, as most of the losses within the tourism industry were suffered by the SMEs, being the weakest links in the chain, it is mostly due to cash flow difficulties which predated the pandemic ([25,107,108]). These difficulties are experienced by businesses whose governments are unable to support a stagnant tourism and hospitality industry, or where existing eligibility regulations limit support for the sectors which do not meet requirements ([109,110]). Therefore, it has been possible for bigger chains to get support, despite enjoying substantial financial resources to survive in the short-to-mid-term, while SMEs were forced to close down when they failed to meet eligibility criteria for government assistance [89].

For the theoretical contribution, this study presents a conceptual model of a resilience framework for destination development during long-term crises, drawing insights from the case of Pattaya. In relation to the framework proposed by McCartney et al. [25] and Traskevich and Fontanari [76], many key elements delineated within those models align with the context of Pattaya. While the framework displays features of resilience and recovery, results for Pattaya showed hallmarks of the city's resilience, namely insights on tourism industry structure, government arrangements and financial environment connected to diversification of the business model and structure supports. These elements can also be recognized as common, yet crucial, areas of focus for enhancing tourism business resilience at the destination in general. Furthermore, Pattaya's resilience framework also demonstrates its specific application in addressing health crises, i.e. Covid-19, through measures like vaccination and the SHA Plus health scheme. This notion indicates the area that requires adaptability of the framework in order to make it suitable to different types of crises at other destinations.

Despite providing valuable insights, there are certain limitations that must be addressed. Firstly, while the research in Pattaya provides deeper perspectives into the specific-destination context, the findings cannot be entirely generalised for application to all kinds of tourism destinations as regards coping strategies for resilience. Secondly, relying mainly on the McCartney et al. [25] framework, useful as it is, may narrow the researchers’ focus to the proposed determinants, leading to oversimplified explanations. Hence the application of a combination of resilience frameworks, or the adoption of perspectives from other disciplines can help reduce the current limitations.

Thirdly, we are aware that using a purposive sample may have inadvertently led to sampling bias. While the opinions of public agencies and entrepreneurs provide valuable insights into the tourism and hospitality industries, including health professionals, they could have shed light on vaccination procedures and other aspects of public health. In particular, the perspectives of frontline workers, like doctors and nurses, would have been particularly valuable in understanding the vaccination process and any potential challenges or barriers faced by the public. It may be beneficial to include healthcare professionals in future studies, for insights related to vaccination policies or public health initiatives. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, this research provides valuable insights and highlights the need for clearer and more supportive measures to facilitate Pattaya's recovery.

It would be of interest to observe the resilience framework adopted by other coastal-inland tourism destinations. Both generic and context-specific outcomes from the future research applying similar framework would be valuable for both public policy makers and the private sector. We can consider generic guidance and strategies derived from similar research in different contexts and determine factors that can be applied to destinations in general, while also taking into account the need for specific adaptation of guidance based on the destination and the type of crisis. This will help destinations better prepare and implement appropriate measures ahead of similar sudden incidents in the future.

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, the situation in Pattaya has shifted as the world has nearly fully recovered. Businesses in Pattaya, like elsewhere, embarked on the journey of resuming their operations. However, this recovery was not without challenges, and it showcased the importance of adaptability and resilience. Many businesses recognized the significance of digitalization, which emerged crucially during the pandemic, especially for marketing and service delivery. This digital transformation remained a cornerstone even after the pandemic, enabling businesses to reach a broader audience and providing alternative revenue streams. The shortage of employees is still evident during the recovery, highlighting the importance of multi-skilled workforces that many enterprises had developed during the pandemic. The struggles faced by smaller enterprises, exacerbated by pre-existing cash flow issues and limited government support, though not a major concern, still require serious attention from Pattaya's tourism authorities. The Covid-19 crisis not only tested the resilience of tourism destinations but also underscored the importance of strategic planning and policy support for long-term sustainability in a post-pandemic world.

Ethic statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Committee for Research Ethics (Social Sciences), with the approval number: 2022/001.1101. All participants/patients provided informed consent to participate in the study. All participants/patients provided informed consent for the publication of their anonymised case details and images.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and the data that support the findings of this study are available in the computer of Dr Roberto B. Gozzoli. Regarding to ethical and privacy considerations, access to certain portions of the data is restricted. For inquiries regarding data access, please contact the corresponding author, Dr Pattarachit Choompol Gozzoli, email pattarachit.goz@mahidol.edu.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Roberto Bruno Gozzoli: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Pattarachit Choompol Gozzoli: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Walanchalee Wattanacharoensil: Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Roberto Bruno Gozzoli reports financial support was provided by Mahidol University International College. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The study was funded by a grant from Mahidol University International College (MUIC), No 02/2022. Moreover, this research study dedicated to Dr. Roberto Bruno Gozzoli (1968–2022), first author, who passed away shortly after completing a draft of this paper.

References

- 1.Statista Research Department . 2023. Foreign Tourist Arrivals Thailand 2018-2022.https://www.statista.com/statistics/994693/thailand-number-international-tourist-arrivals/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reporters Post. PM pleased with rising tourist numbers. Bangk. Post. 2021 https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2215283/pm-pleased-with-rising-tourist-numbers Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casado-Aranda L.-A., Sánchez-Fernández J., Bastidas-Manzano A.-B. Tourism research after the COVID-19 outbreak: insights for more sustainable, local and smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021;73 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Freitas R.S.G., Stedefeldt E. COVID-19 pandemic underlines the need to build resilience in commercial restaurants' food safety. Food Res. Int. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport . 2021. The Tourism Recovery Plan.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/992974/Tourism_Recovery_Plan__Web_Accessible_.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Directory, Australian Capital Territory Chief minister, treasury and economic development. Framework for Recovery of the Visitor Econ. 2020 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloom D.E., Cadarette D. Infectious disease threats in the twenty-first century: strengthening the global response. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:549. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan V.Y., Jamison D.T., Summers L.H. Pandemic risk: how large are the expected losses. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018;96(2):129–134. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.199588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith R.A. Beach resorts: a model of development evolution. Landsc. Urban Plann. 1991;21(3):189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truong J.M., Chemnasiri T., Wirtz A.L., et al. Diverse contexts and social factors among young cisgender men and transgender women who sell or trade sex in Bangkok and Pattaya, Thailand: formative research for a PrEP program implementation study. AIDS Care. 2022;34(11):1443–1451. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2022.2067317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCamish M. The friends thou hast: support systems for male commercial sex workers in Pattaya, Thailand. J. Gay Lesb. Soc. Serv. 1999;9(2–3):161–191. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturrock T. Pattaya, a New Breed of Chinese Tourist Emerges: Meet the FITs. South China Morning Post. 2019. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/society/article/2185336/pattaya-new-breed-chinese-tourist-emerges-meet-fits Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reporters Post. Seoul mates. Bangkok post. Business: Asia Focus. 2013 https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/342258/seoul-mates Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Editorial . ThaiPBS World; 2021. Pattaya Hotels Want to Be Closed So Employees Can Claim State Benefits.https://www.thaipbsworld.com/pattaya-hotels-want-to-be-closed-so-employees-can-claim-state-benefits-2/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin R., Di Mauro B.W., editors. Economics in the Time of COVID-19. CEPR Press; London: 2020. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong B., Zhang S., Yuan L., Chen K.Z. A balance act: minimizing economic loss while controlling novel coronavirus pneumonia. Journal of Chinese Governance. 2020;5(2):249–268. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashworth C. Thaiger; 2021. Reopening of Bars and Nightclubs Pushed to Mid-january 2022.https://thethaiger.com/news/national/breaking-reopening-of-bars-and-nightclubs-pushed-to-mid-january-2022 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newsroom T.A.T. 2022. Thailand's Latest Entry Requirements from 1 May 2022.https://www.tatnews.org/2022/04/thailands-latest-entry-requirements-from-1-may-2022/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statista Research Department Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Thailand in. 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1253122/thailand-impact-covid-19-on-smes/ Available from:

- 20.Janyam S., Phuengsamran D., Pangnongyang J., et al. Protecting sex workers in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic: opportunities to build back better. WHO South East Asia. J. Public Health. 2020;9(2):100–103. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.294301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nidhinarangkoon P., Ritphring S., Udo K. Impact of sea level rise on tourism carrying capacity in Thailand. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020;8(2):104. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swennen C., Sampantarak U., Ruttanadakul N. TBT-pollution in the Gulf of Thailand: a re-inspection of imposex incidence after 10 years. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009;58(4):526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan H.R. Impacts of tourism activities on environment and sustainability of Pattaya beach in Thailand. J. Environ. Manag. Tourism (JEMT) 2017;8(24):1469–1473. 08. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin R., Sunley P. On the notion of regional economic resilience: conceptualization and explanation. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015;15(1):1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCartney G., Pinto J., Liu M. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: the case of Macao. Cities. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2021.103130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler R.W. The concept of A tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. The Canad. Geograph./Le Géographe canadien. 1980;24(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szromek A.R. An analytical model of tourist destination development and characteristics of the development stages: example of the island of bornholm. Sustainability. 2019;11(24):6989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKercher B. Destinations as products? A reflection on Butler's life cycle. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005;30(3):97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristjánsdóttir H. Can the Butler's tourist area cycle of evolution Be applied to find the maximum tourism level? A comparison of Norway and Iceland to other OECD countries. Scand. J. Hospit. Tourism. 2016;16(1):61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith R.A. Beach resort evolution. Ann. Tourism Res. 1992;19(2):304–322. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longjit C., Pearce D.G. Managing a mature coastal destination: Pattaya, Thailand. J. Destin. Market. Manag. 2013;2(3):165–175. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen E. Tourism and AIDS in Thailand. Ann. Tourism Res. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storer G. Research note. Engl. Specif. Purp. 1999;18(4):367–374. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baral S.D., Friedman M.R., Geibel S., et al. Male sex workers: practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):260–273. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60801-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svensson P., Sundbeck M., Persson K.I., et al. A meta-analysis and systematic literature review of factors associated with sexual risk-taking during international travel. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:65–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manieri M., Svensson H., Stafström M. Sex tourist risk behaviour--an on-site survey among Swedish men buying sex in Thailand. Scand. J. Publ. Health. 2013;41(4):392–397. doi: 10.1177/1403494813480572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dealey S. vol. 34. 2001. “ tourist very good for me. No sailor.”. (Pattaya, Civilians Drive the Sex Trade). 5. Sect. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaisuekun K., Sunanta S. German migrants in Pattaya, Thailand: gendered mobilities and the blurring boundaries between sex tourism, marriage migration, and lifestyle migration. The Palgrave handbook of gender and migration. 2021:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prideaux* B., Agrusa J., Donlon J.G., Curran C. Exotic or erotic–contrasting images for defining destinations. Asia Pac. J. Tourism Res. 2004;9(1):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bissen R., Chawchai S. Microplastics on beaches along the eastern Gulf of Thailand - a preliminary study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;157 doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kongprajug A., Chyerochana N., Rattanakul S., et al. Integrated analyses of fecal indicator bacteria, microbial source tracking markers, and pathogens for Southeast Asian beach water quality assessment. Water Res. 2021;203 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juksu K., Zhao J.L., Liu Y.S., et al. Occurrence, fate and risk assessment of biocides in wastewater treatment plants and aquatic environments in Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;690:1110–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall C.M., Prayag G., Amore A. 2017. Tourism and Resilience. Individual, Organisational and Destination Perspectives; p. 1. online resource.) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becken S. Developing A framework for assessing resilience of tourism sub-systems to climatic factors. Ann. Tourism Res. 2013;43:506–528. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Butler R., editor. Tourism and Resilience. CABI; Wallingford and Boston: 2017. p. 1. online resource (xii, 230 pages) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall C.M. Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: from first- and second-order to third-order change. J. Sustain. Tourism. 2011;19(4–5):649–671. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown N.A., Orchiston C., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Johnston D. An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J. Hospit. Tourism Manag. 2018;36:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prayag G. Time for reset? Covid-19 and tourism resilience. Tourism Rev. Int. 2020;24(2):179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beirman D. Thailand's approach to destination resilience: an historical perspective of tourism resilience from 2002 to 2018. Tourism Rev. Int. 2018;22(3–4):277–292. [Google Scholar]

- 50.ESCAP UN . 2018. Leave No One behind: Disaster Resilience for Sustainable Development: Asia-Pacific Disaster Report 2017.https://repository.unescap.org/handle/20.500.12870/1553 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janusz K., Six S., Vanneste D. Building tourism-resilient communities by incorporating residents' perceptions? A photo-elicitation study of tourism development in Bruges. J. Tourism Futur. 2017;3(2):127–143. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones P., Wynn M.G. The circular economy, natural capital and resilience in tourism and hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manag. 2019;31(6):2544–2563. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lew A.A. Scale, change and resilience in community tourism planning. Tourism Geogr. 2014;16(1):14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lew A.A., Ng P.T., Ni C-cN., Wu T-cE. Community sustainability and resilience: similarities, differences and indicators. Tourism Geogr. 2016;18(1):18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruiz-Ballesteros E. Social-ecological resilience and community-based tourism. Tourism Manag. 2011;32(3):655–666. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiksel J. Sustainability and resilience: toward a systems approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Pol. 2006;2:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker B., Carpenter S., Anderies J., et al. Resilience management in social-ecological systems: a working hypothesis for a participatory approach. Conserv. Ecol. 2002;6(1):251–261. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsao C-y, Ni C-c. Vulnerability, resilience, and the adaptive cycle in a crisis-prone tourism community. Tourism Geogr. 2016;18(1):80–105. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holladay P.J. Destination resilience and sustainable tourism development. Tourism Rev. Int. 2018;22(3):251–261. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoffmann S.L. Utah State University; 2008. Application of Resiliency Theory and Adaptive Cycles as a Framework for Evaluating Change in Amenity-Transition Communities. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheer J.M., Lew A.A. vol. 1. 2017. p. 328. (Tourism, Resilience and Sustainability : Adapting to Social, Political and Economic Change). online resource. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baho D.L., Allen C.R., Garmestani A.S., et al. A quantitative framework for assessing ecological resilience. Ecol. Soc.: J. Integrative Sci, Resilience Sustain. 2017;22(3):1. doi: 10.5751/ES-09427-220317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amore A., Prayag G., Hall C.M. Conceptualizing destination resilience from a multilevel perspective. Tourism Rev. Int. 2018;22(3–4):235–250. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Filimonau V., De Coteau D. Tourism resilience in the context of integrated destination and disaster management (DM 2) Int. J. Tourism Res. 2020;22(2):202–222. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fabry N., Zeghni S. In: Tourismes et adaptations. Seyssinet-Pariset. Cholat F., Gwiazdzinski L., Tritz C., J. T, editors. Elya Editions; 2019. Resilience, tourist destinations and governance: an analytical framework; pp. 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Partanen M. Finland. Tourism Planning and Development; 2021. Social Innovations for Resilience—Local Tourism Actor Perspectives in Kemi; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones P., Comfort D. The role of resilience in research and planning in the tourism industry. Athens J. Tour. 2020;7(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mittal R., Sinha P. Framework for a resilient religious tourism supply chain for mitigating post-pandemic risk. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021 ahead-of-print: [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuščer K., Eichelberger S., Peters M. Tourism organizations' responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: an investigation of the lockdown period. Curr. Issues Tourism. 2021:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sigala M. Tourism and COVID-19: impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020;117:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Specht A. Gold Coast: CRC for Sustainable Tourism; 2008. Extreme Natural Events and Effects on Tourism Central Eastern Coast of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rai S.S., Rai S., Singh N.K. Environment, Development and Sustainability; 2021. Organizational Resilience and Social-Economic Sustainability: COVID-19 Perspective; pp. 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Santos-Lacueva R., Clavé S.A., Ò Saladié. The vulnerability of coastal tourism destinations to climate change: the usefulness of policy analysis. Sustainability. 2017;9(11):2062. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luthe T., Wyss R. Resilience to climate change in a cross-scale tourism governance context: a combined quantitative-qualitative network analysis. Ecol. Soc. 2016;21(1) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sagala S., Rosyidie A., Azhari D., Ramadhani A., Rinaldy T.K., Racharjo S.I. Building resilience from double disasters: the direct impact of the pandeglang tsunami 2018 and COVID-19 outbreak on tourism and supporting industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021;704(1) [Google Scholar]

- 76.Traskevich A., Fontanari M. Tourism Planning and Development; 2021. Tourism Potentials in Post-COVID19: the Concept of Destination Resilience for Advanced Sustainable Management in Tourism; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sheppard V.A., Williams P.W. Factors that strengthen tourism resort resilience. J. Hospit. Tourism Manag. 2016;28:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sheppard V.A. In: Tourism and Resilience. Butler R., editor. CABI; Wallingford and Boston: 2017. Resilience and destination governance; pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scott D., de Fritas C., Matzarakis A. In: Biometeorology for Adaptation to Climate Variability and Change. Ebi K.L., Burton I., McGregor G., editors. Springer; 2008. Adaptation in the tourism and recreation sector; pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Given L.M. Sage publications; 2008. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Banerjee D., Sathyanarayana Rao T.S., Kallivayalil R.A., Javed A. Psychosocial framework of resilience: navigating needs and adversities during the pandemic, A qualitative exploration in the Indian frontline physicians. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.622132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]