Abstract

Venous leg ulcer (VLU) is the most severe manifestations of chronic venous disease, which has characterized by slow healing and high recurrence rates. This typically recalcitrant and recurring condition significantly impairs quality of life, prevention of VLU recurrence is essential for helping to reduce the huge burden of patients and health resources, the purpose of this scoping review is to analyse and determine the intervention measures for preventing recurrence of the current reported, to better inform healthcare professionals and patients. The PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library databases, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), Wan Fang Data and Chongqing VIP Information (CQVIP) were accessed up to June 17, 2023. This scoping review followed the five‐steps framework described by Arksey and O'Malley and the PRISMA extension was used to report the review. Eleven articles were included with a total of 1503 patients, and adopted the four effective measures: compression therapy, physical activity, health education, and self‐care. To conclude, the use of high pressure compression treatment for life, supplementary exercise therapy, and strengthen health education to promote self‐care are recommended strategies of VLU prevention and recurrence. In addition, the importance of multi‐disciplinary teams to participate in the care of VLU in crucial.

Keywords: compression therapy, exercise, recurrence, scoping review, venous leg ulcers

1. INTRODUCTION

Venous leg ulcer (VLU) is the most severe manifestations of chronic venous disease, which as an open skin lesion between the ankle and the knee affected by venous hypertension. 1 , 2 As the most common lower extremity ulcer, VLU affects 1% of the population with a prevalence that increases with age. 3 , 4 In the United States, up to 4% of people over the age of 65 are suffer from it. Unfortunately, after healing, with an incidence of 22% recurrence within 3 months, 57% by 12 months and 78% of those who were followed up for three years. 5 , 6 Once ulcer occurs, the patient will experience skin injury of the legs with symptoms of pain, ambulation barriers and limb heaviness. In addition, it has shown that physical complaints are age‐dependent, patients are more worsen of daily burdens, limited in their activities and dependent on the other helps with increasing age. 7 This typically recalcitrant and recurring condition significantly impairs quality of life, and its treatment not only causes distress to patients, but also places a heavy financial burden upon healthcare systems. 8

The goals of VLU treatment are to promote wound healing, reduce pain and edema, improve the quality of patient's life and prevent ulcer recurrence. Standard evidence‐based care includes compression therapy and the use of adjunctive agents, surgery, has also been shown to improve ulcer healing and decrease the risk of recurrence. 8 , 9 Studies have shown that surgery can significantly reduce 12‐month ulcer recurrence rate and most patients with venous leg ulceration could benefit from it. 10 , 11 However, open surgery is unsuitable for everyone and not a popular strategy for most people. 8

Venous ulcers of the lower extremities are characterized by slow healing and high recurrence rates, it is necessary to care for regardless of whether they are damaged. A study found that patients with VLU underwent surgery, compression therapy, and skin care were strategies for preventing relapse, but patients who did not conduct surgery were not considered. 12 Compression stockings are a routine method for preventing recurrence of VLU, but it is not yet determined whether the use of higher pressure‐level stockings is related to further reducing risks. 13 In addition, Behairy and Masry 14 showed that education can increase the compliance of patients with VLU, thereby helping to avoid the recurrence of ulcers. Compression therapy, exercise, and leg elevation are recommended to prevent recurrence, but how to intervene and the effectiveness of using these strategies are not described. 15

Prevention of VLU recurrence is essential for helping to reduce the huge burden of patients and health resources, but there are currently no published studies summarizing effective relapse prevention strategies in non‐surgical patients. Thus, the purpose of this scoping review is to analyse and determine the intervention measures for preventing recurrence of the current reported, to better inform healthcare professionals and patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

This scoping review followed the five‐steps framework described by Arksey and O'Malley 16 and involved identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting appropriate studies, classifying and extracting the data, analysing, synthesizing and reporting the results. The PRISMA extension was used to report the scoping review. 17

2.2. Identifying the research question

The scoping review aimed to identify and synthesize evidence from relevant studies that involved effective interventions in preventing the recurrence of VLU. To address this aim, the following questions were identified:

What types of the interventions have been reported to prevent the recurrence in patients with VLU?

How are the effectiveness of these interventions in preventing the recurrence in such patients?

2.3. Identifying relevant studies

2.3.1. Search strategy and databases

The PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library databases were accessed up to 17 June 2023. We also searched the following Chinese databases: (1) Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), (2) Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), (3) Wan Fang Data and (4) Chongqing VIP Information (CQVIP). Searches of ‘venous leg ulcer’, ‘chronic venous disease’, ‘prevent’ and ‘recurrence’ were conducted, including an all‐inclusive list of search terms associated with these terms. In addition, we manually conducted to identify additional sources and traceable references to search for more valuable articles. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria would be strictly followed to filter the articles. The search strategies used for databases are included in the Appendix A.

2.3.2. Inclusion criteria

Articles were included based on the following criteria: (1) Participants (age ≥ 18 years) were diagnosed as VLU or had the history of VLU; (2) Outcomes included the recurrence of VLU, health‐related quality of life, calf muscle pump (CMP) function, range of ankle mobility, or adherence rates; (3) Articles were in Chinese or English; (4) All types of study design were considered, including both qualitative and/or quantitative studies.

2.3.3. Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded for the following criteria: (1) Patients with non‐venous leg ulceration (e.g. arterial, traumatic, vasculitis and malignant ulcers); (2) Research did not report the recurrence of VLU and (3) Editorials, letters, case reports, conference abstracts and non‐human studies.

2.4. Selection process

Search results were imported into a reference database (Endnote X9). Duplicated articles were removed. Two authors independently screened references according to the relevant arrangement standards. First, they browsed all articles and eliminated the unrelated studies by the title and abstract, and then carefully read the full text of the remaining reference lists. The two authors also manually searched the reference list to identify potentially relevant articles. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion, and if necessary, consulted with a third author.

2.5. Data extraction

One author reviewed all relevant studies and complied the data in a table, which including: the first author's name, year of the paper publication, country, study design, sample size, intervention methods, and relevant outcomes. Another author verified this information. In addition, interventions of interest were, and the type of intervention were also recorded.

2.6. Quality assessment

Two authors independently used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (2018) 18 to critically appraise the quality of all studies. Discrepancies were resolved by negotiation and the results were determined based on unanimous opinions.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Studies screening

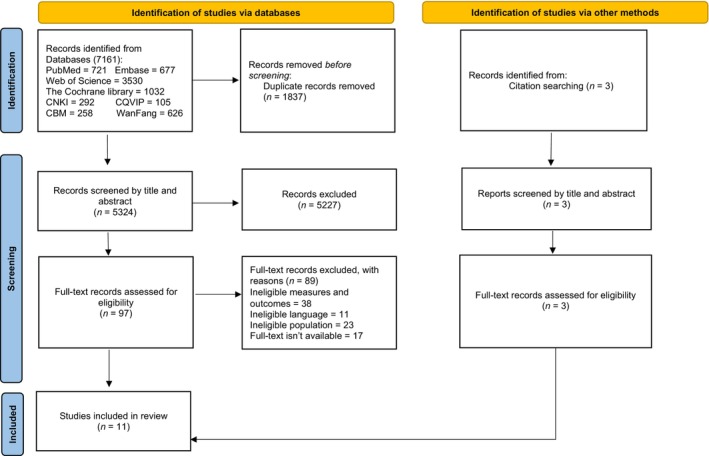

The database identified a total of 7161 articles. After removing the duplicates, 5324 articles were left. As well, 5227 articles were excluded on title and abstract. Following full text assessment, 89 articles were also excluded. After the two authors traced back to the reference list and manually retrieved and evaluated the quality of the articles, three more were included back to the study, leaving 11 articles remaining for the review. The PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1) illustrates the process.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the selection process. CBM, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database; CNKI, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure; CQVIP, Chongqing VIP Information.

3.2. Characteristics of the included studies

Eleven studies were included, and the main study types were randomized controlled trial. A total of 1503 patients were included in research and the average age was 63.2 years old. The recurrence rate were far less in patients with interventions. Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Information | Studies (n) |

|---|---|

| Age means and/or range | 63.2 (28–91) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 724 |

| Female | 707 |

| Not stated | 72 |

| Study design | |

| Qualitative | 3 |

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 5 |

| Quantitative non‐randomized | 2 |

| Mixed methods | 1 |

| Study setting | |

| Clinics | 5 |

| Centre | 2 |

| University | 1 |

| Home | 2 |

| Setting not stated | 1 |

| Recurrence | |

| Yes | 483 |

| No | 818 |

| Not stated | 202 |

| Reasons of occurrence | |

| Trauma through an accident | 76% |

| Trauma from compression therapy (the stockings did not fit properly, visually unappealing) | 24% |

3.3. Quality of the included studies

The overall quality is good, and the evaluation tools, standards and detailed results are included in the Appendix B.

4. INTERVENTIONS ON PREVENTING RECURRENCE OF VLU

Eleven articles 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 included in this study adopted the following four effective measures: Compression therapy, physical activity, health education and self‐care. Among them, the compression therapy was applied to each study as a conventional intervention method, but only three articles 19 , 20 , 21 investigated the effectiveness of different pressure measures, pressure values, duration and other factors on patients to prevent for relapse. Two papers 22 , 23 addressed the role of physical activity in preventing the recurrence of VLU and described different activities. Two qualitative studies 24 , 25 and one retrospective research 26 investigated the ability and approach of patients' self‐care after healing and summarized the important methods of self‐management of experienced patients at home. Three papers 27 , 28 , 29 reported the increase of patient’ knowledge and treatment compliance, the decreased recurrence rate of VLU after health education intervention.

4.1. Compression Therapy

Three studies 19 , 20 , 21 compared the effects of pressures caused by different types of compression stockings on the VLU recurrence (Table 2). Two studies 19 , 20 demonstrated that the risk of VLU was very higher in population with low grade of compression stocking than in population wearing high grade compression one. It was also reported that the non‐compliance of a considerable number of population during a long‐term follow‐up, was directly related to the strength of compression stocking. Patients who using the highest‐class compression stocking showed the highest non‐compliance rate. Another study 21 compared the effectiveness of bandage and stocking in preventing recurrence, 23% recurrence rate of the bandage group and 14% recurrence rate of the stocking group. The rate of recurrence was lower with stocking group than with the bandage group. However, many patients in the stocking group changed their treatment because of discomfort.

TABLE 2.

Studies comparing the effects of different pressures caused by different types of compression stockings.

| Recurrence rate | Non‐compliance rate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Comparing | Total patients | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Time of follow‐up | ||

| Milic et al. 19 | In group A, patients wore compression stockings that exert graduated pressure with the highest compression (18–25 mmHg) at the ankle. In group B, patients wore a ready‐made tubular compression device (Tubulcus) that exerts graduated pressure with the highest compression (25–35 mmHg) at the ankle. In group C, the above‐mentioned Tubulcus device was wrapped over by an additional component of one elastic bandage. | 477 | A81% | B53% | C16% | A16% | B20% | C37% | 10 years |

| Milic et al. 20 | In group A (intervention), patients wore a ready‐made tubular compression device (Tubulcus) that exerts graduated pressure with the highest compression (30–40 mm Hg) at the ankle. In group B (control), patients wore compression stockings that exert graduated pressure with the highest compression (18–24 mm Hg) at the ankle. | 308 | 28.98% | 60% | 10.23% | 6.25% | 5 years | ||

| Ashby et al. 21 |

Participants in the control group received the four‐layer bandages, which had to deliver 40 mm Hg of compression at the ankle. Participants in the intervention group received two‐layer stockings, which had to deliver 35–40 mm Hg of compression at the ankle. |

454 (230 hosiery and 224 bandage) | 14% | 23% | 38% | 28% | 12 months | ||

4.2. Physical activity

Two studies 22 , 23 used physical activity as adjunct treatment to compression therapy and compared that to the use of compression alone (Table 3). Xin et al. 23 found that tiptoe exercise and ankle pump exercise helped to reduce the recurrence rate of VLU. However, the Klonizakis et al. 22 combined aerobic, resistance, and flexibility exercises and reported that it was no significant difference in the recurrence rate of ulcers between the control group and the exercise group. Neither of the two studies reported serious adverse events, only mentioned the increased wound discharge after the exercise.

TABLE 3.

Physical activities comparing.

| Reference | Country | Group | Sample size | Intervention | Physical activity | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xin et al. 23 | China | The control group | 26 | Conventional care, wound treatment, and compression therapy. | 6 patients (23.1%) | |

| The exercise group | 31 | Six months of lower extremity muscle training program on the basis of the control group measures. |

|

1 patient (3.2%) | ||

| Klonizakis et al. 22 | UK | The control group | 21 | Standard compression therapy | 1 patient | |

| The exercise group | 18 | On the basis of the control group, exercise group were invited to attend 3 sessions of supervised exercise each week for 12 weeks (total of 36 sessions), each exercise session was scheduled to last approximately 60 min and to comprise a combination of aerobic, resistance and flexibility exercises. |

|

2 patients |

4.3. Self‐care

Three studies 24 , 25 , 26 reported that the use of compression bandages or strong medical compression stockings is the best way of self‐care and can effectively prevent the recurrence of VLU. Some participants also used self‐care knowledge and skills to protect their wound. Most patients followed their doctors' suggestions and developed self‐management strategies according to their own conditions, including moisturizing their skin, putting their legs up, increasing physical activity, changing their lifestyle, and eating more vegetables and fruit. Their interventions were successful and prevented recurrence between 6 and 12 months. 24 However, it was reported that almost 70% of patients practiced self‐treatment and a quarter of them changed prescribed treatment due to health care environment restrictions, patients' lack of knowledge and learning channels, and no adherence to and provision of VLU self‐care recommendation. 25 Studies indicated that participants suffered anxiety, depression, and fear of re‐ulceration in the process of self‐care, which made them more careful to take care of the wound. 24 , 25

4.4. Health education for protecting leg integrity

Three studies 27 , 28 , 29 were included (Table 4), all of which were about disease knowledge and prevent recurrence methods for patients with VLU. The final result showed that patients had either no relapse or lower recurrence rates. Kapp and Miller 27 found that patients believed in the efficacy of preventive measures recommended by education and actively participated in activities. Gonzalez 28 reported that the knowledge scores caused by educational intervention increased significantly. Van Hecke et al. 29 showed the increased number of patients participating in physical exercises and their knowledge.

TABLE 4.

Education comparing.

| Reference | Intervention context | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Kapp and Miller 27 |

Venous leg ulcer's introduction. Venous leg ulcers treatment: activity and exercise, nutrition and hydration, skin care. Compression stocking. |

No recurrence. |

| Gonzalez 28 |

Disease process (6 items). Self‐care activities (7 items). |

Half of the patients had no recurrence. |

| Van Hecke et al. 29 |

Provide tailored verbal information and written information (aetiology, realistic perspective, treatment and lifestyle advice). Demonstrate leg exercises, leg elevation, application of compression. |

One of the six patients who healed had a recurrence. |

5. DISCUSSION

The prevention strategies for the recurrence of people with VLU is a priority after wound healing, considering the high recurrence rate of ulcers. As a result of VLU reoccurrence, the physical, mental, and economic consequences can be avoided by applying correct interventions. However, only a few studies currently guided this implementation process. Patients should follow compression therapy for life, participate in physical activity, and master effective self‐care knowledge, abilities, and beliefs through health education activities to promote healthy quality of life. The following interventions were determined during the review process.

5.1. Persist in high pressure compression treatment for life

Most of the included studies clearly prove the benefits of compression therapy because it can improve the veinous blood return of the lower limbs, which helps to accelerate the healing of ulcers, reduce edema, relieve pain, and prevent recurrence. 30 This review demonstrates that stronger compression devices with higher pressure (≥30 mm Hg) not only in reducing the risk of recurrence effectively, but also in extending the time without ulcers. Ashby et al. 21 has suggested that compression stocking is the main way to prevent recurrence, it has more advantages compared with bandages, including higher quality and lower costs, and can also reduce the number of times for treatments. However, compression treatments are simple, but they become complex in practice.

First, it is very difficult to insist patients on compression therapy after healing. Patients often believe that it is unnecessary to follow the prescription of treatment, or they give up halfway of the treatment because of discomfort with the compression stocking. 20 Compliance with compression treatment is an important factor affecting ulcer healing and recurrence. A qualitative study suggested that the lack of knowledge was one of the biggest barriers to patients' adherence. 31 Participants reported that any complex, inadequate or incorrect VLU information delivered by clinicians would lead to failure of VLU treatment, while also found that knowledge and acceptance of the treatment would optimize the compliance of patients to compression. Improving patient's compliance to treatment is challenging and is common to patients with venous ulcers in the lower limb. 32 However, this may be changed by providing patients an interdisciplinary educational intervention, which is made up of many professional health care providers to give guidance for nursing, exercise, nutrition, and other aspects. 32 In addition, it is necessary to constantly follow up, encourage and communicate with patients about the use of compression treatment. 19

Pressure level should also be continuously monitored. Applying the correct pressure is significant for effective treatment, which helps to improve the quality of patients' life at all stages. 33 Thus, it is necessary to measure the compression device based on the patients' situation and circulation to maintain appropriate pressure.

5.2. Supplementary exercise therapy

The results of this review demonstrated that assistive exercise is an effective intervention in treating and preventing VLU. Leg elevations and ankle movements were successful interventions confirmed in this study, but there were no specific guidelines. In addition, walking and squatting are also considered effective. It has been reported that regular physical activity is associated with numerous benefits in patients with VLU, contributing to increase CMP function and improve the blood flow dynamics of the lower limb, and it is also a low‐cost and low‐risk intervention to promote physical and mental health. 22

However, patients show low enthusiasm for participating in the exercise. A study reported that the main obstacles for patients not to engage in exercise with VLU were pain, negative emotions, and misinformation provided by doctors, and their sedentary lifestyle. 34 Therefore, it is necessary to actively reduce these obstacles and encourage patients to participate in physical activity.

Although we do not have sufficient evidence to suggest specific types of exercise and activity guidance, exercise has shown to prevent wound recurrence, and an intervention that has not been confirmed on the participants' negative impacts. It should be encouraged as part of the VLU prevention recurrence intervention strategy.

5.3. Strengthen health education to promote self—care

Ulcers have a significant impact on the quality of patient's life, self‐care skills for the preventing recurrence of VLU at home may contribute to reduce the burdens on the disease while decreasing the risk of relapse. When patients actively participated in the self‐care management, they gained confidence; benefited from unnecessary and frequent visits to the hospital, and led to decrease the number of consultations. 26 Therefore, health care providers play an important role in wound management, including recommendations for self‐care measures after wound healing, adherence to the doctor's order, and frequently examine the healed site. 35 The studies in this review reported that inappropriate strategies and acute accidents were the two main causes of VLU recurrence. Therefore, an important step in the process of practicing self‐care is appraisal of patient's self‐treatment activities. To closely monitor patients' self‐care activities to improve the outcomes can be in the form of patient education, and support. 36

Health education has great advantages, helping patients to strengthen their compliance of interventions and providing them guidance and strategies to conduct appropriate self‐care, which is essential for preventing ulcers' recurrence and improving the quality of life of patients with VLU. While preventive interventions for VLU patients are considered vital for physical health, they often face challenges in practical actions. For example, it has been confirmed that patients with VLU, who lack a certain understanding of disease process or preventive therapeutic methods, would not effectively manage the wounds. 25 Another study showed that evidence‐based educational programs were an effective way to encourage patients to engage in healthy behaviors. 27 Education could change in patients' beliefs; establish routines to develop good habits; and achieve their optimal health goals.

5.4. Importance of multi‐disciplinary approach

The importance of multi‐disciplinary teams is also highlighted in the review. Multidisciplinary collaboration is critical for comprehensive treatment of patients with VLUs. Effective interventions require the participation of multidisciplinary professionals, the focus on patient‐centred care, and the cooperation of the entire treatment team. In addition, the current prevention approaches of VLU include compression therapy, protein diet, and specific exercise, which requires a cross‐disciplinary medical care professional team.

6. LIMITATIONS

The limitations of this scoping review include small number of retrieved articles, small sample sizes for most included articles, and differences in baseline characteristics of patients among the articles. In addition, we only included articles published in English or Chinese. Evidence in other languages related to this study might be excluded. Although we use known databases to retrieve a comprehensive literature, many articles are still unpublished. In this paper, we propose four interventions to prevent recurrence of patients with VLU, but the specific interventions and their frequencies have not been recommended. Because the research included in the design and data collection were heterogeneous, it was difficult to draw consistent conclusions among studies. For example, although exercise intervention has been considered effective, but with limited evidence, we can only emphasize its importance to recommend for clinical practice.

7. CONCLUSION

The use of high pressure compression treatment for life, supplementary exercise therapy, and strengthen health education to promote self‐care are recommended strategies of VLU prevention and recurrence. In addition, the importance of multi‐disciplinary teams to participate in the care of VLU in crucial. However, evidence of specific interventions are limited from the articles. Studies with large sample size should be conducted in the future to confirm the effectiveness of the measures.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was funded by the Talent Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project of Lanzhou City, China (No. 2022‐RC‐50), Higher Education Innovation Fund project of Gansu Province (No. 2022B‐045), Cuiying Scientific and Technological Innovation Program of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (No. CY2021‐QN‐A15).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

APPENDIX A.

A.1.

Search strategies and results.

| Database | Search algorithm | Results found |

|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | ((((((venous leg ulcers[Title/Abstract]) OR (lower extremtity venous ulcer[Title/Abstract])) OR (VLUs[Title/Abstract])) OR (venous leg disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (chronic venous disease[Title/Abstract])) OR (chronic venous ulcers[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((recurrence[MeSH Terms]) OR (recur*[Title/Abstract])) OR (prevent*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Relapse[Title/Abstract])) | 721 |

| Embase |

#1 ‘venous leg ulcer’:ab,ti OR ‘lower extremtity venous ulcer’:ab,ti OR ‘vlus’:ab,ti OR ‘venous leg disease’:ab,ti OR ‘chronic venous disease’:ab,ti OR ‘chronic venous ulcers’:ab,ti #2 ‘recurrent disease’/exp #3 ‘recur*’:ab,ti OR ‘prevent*’:ab,ti OR ‘relapse’:ab,ti #4 #2 OR #3 #5 #1 AND #4 |

677 |

| Web of Science | (TS = (venous leg ulcers OR lower extremtity venous ulcer OR VLUs OR venous leg disease OR chronic venous disease OR chronic venous ulcers)) AND TS = (recur* OR prevent* OR Relapse) | 3530 |

| The Cochrane library |

#1 (venous leg ulcers OR lower extremtity venous ulcer OR VLUs OR venous leg disease OR chronic venous disease OR chronic venous ulcers) ti,ab,kw #2 Mesh descriptor (Recurrence) explode all tress #3 (recur*)ti,ab,kw OR (prevent*)ti,ab,kw OR(Relapse)ti,ab,kw #4 #2 OR #3 #5 #1 AND #4 |

1032 |

| CNKI |

#1 (venous leg ulcer OR venous leg disease OR lower extremtity venous ulcer OR chronic venous disease OR chronic venous ulcer): TS #2 (recurrence OR relapse OR recurrence rate OR pevention): TS #3 #1 AND #2 |

292 |

| CQVIP |

#1 (venous leg ulcer OR venous leg disease OR lower extremtity venous ulcer OR chronic venous disease OR chronic venous ulcer): ti or ab #2 (recurrence OR relapse OR recurrence rate OR pevention): ti or ab #3 #1 AND #2 |

105 |

| CBM |

#1 “venous leg ulcer”[Common field: Smart] OR “lower extremtity venous ulcer”[Common field: Smart] OR “venous leg disease”[Common field: Smart] OR “chronic venous disease”[Common field: Smart] OR “chronic venous ulcer”[Common field: Smart] #2 “recurrence”[Unweighted: Extended] #3 “recurrence”[Common field: Smart] OR “relapse”[Common field: Smart] OR “recurrence rate”[Common field: Smart] OR “pevention”[Common field: Smart] #4 (#3) OR (#2) #5 (#4) AND (#1) |

258 |

| WanFang |

#1 (venous leg ulcer OR venous leg disease OR lower extremtity venous ulcer OR chronic venous disease OR chronic venous ulcer): TS #2 (recurrence OR relapse OR recurrence rate OR pevention): TS #3 #1 AND #2 |

626 |

APPENDIX B.

B.1.

The influence of different sub‐bandage pressure values in the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration—A 10 year follow‐up.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Qualitative | 1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | √ | They used an interpretative phenomenolo‐gical analysis qualitative approach based on the hermeneutic version of phenomenolo‐gy. This explored how human beings make sense of a major life experience on a personal level. | ||

| 2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | √ | Semi‐structured face‐to‐face interviews were conducted, and interviews were digitally audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim. | |||

| 3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | √ | ||||

| 4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | √ | The part of the results summarized the number and cause of the patient, and did not explain the rate of VLU in detail. | |||

| 5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | √ | They identified three main themes related to participant experience of VLU occurrence or recurrence, the reasons for each theme are discussed in detail. | |||

Abbreviation: VLU, Venous leg ulcer.

“Wounds Home Alone”‐Why and how venous leg ulcer patients self‐treat their ulcer: a qualitative content study.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | This study focuses on how and why patients practice self‐treatment. | ||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Qualitative | 1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | √ | What kind of qualitative research approaches did author use it without explanation | ||

| 2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | √ | In‐depth semi‐structured interviews were conducted with participants, and the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data from the interview transcripts were coded, and then a comparative analysis of the codes was undertaken by the researchers independently. | |||

| 3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | √ | The article uses the method of combining text and chart forms to fully explain the results of the research results. | |||

| 4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | √ | For example, 32 participants were interviewed, their demographic characteristics and wound durations are shown in Table 1. | |||

| 5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | √ | The article makes full use of the data to the four subthemes and four themes of VLU patients with self‐treatment. | |||

Abbreviation: VLU, Venous leg ulcer.

Self‐care‐based treatment using ordinary elastic bandages for venous leg ulcers.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative non‐randomized | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? | √ | This study only explains the number of target population who have included research, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the sample did not describe. | ||

| 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | √ | Once patients had perfected the bandage, they visited the clinic once every 1–3 months, and researchers examined the wounds and bandaging techniques. During every visit, two measurements of the maximal perpendicular diameter of VLU were recorded, and these values were multiplied to determine the ulcer size as described by Stacey et al. | |||

| 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | Results have complete data description and analysis | |||

| 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | √ | No description | |||

| 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | √ | According to the description of the research design method and results, the intervention is implemented in accordance with the expected | |||

Abbreviation: VLU, Venous leg ulcer.

The influence of different sub‐bandage pressure values in the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration—A 10 year follow‐up.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | √ | Randomization was computer generated, and patients were randomized into three groups, but it did not introduce the allocation concealment. | ||

| 2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | √ | No significant difference was observed between the three study groups according to the CEAP classification (Table 1). The three study groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, general medical history, previous episodes of ulceration, size of the ulcer and duration of the ulcer (Table 2). | |||

| 3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | Results are described in the form of combining text and pictures. The content is detailed, and the primary outcome and secondary outcome data are complete. | |||

| 4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | √ | Whether the outcome assessors in the article knows who is receiving which interventions are accepting. | |||

| 5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | √ | During the 10‐year follow‐up, 117 of 477 patients (24.52%) did not comply with their randomized compression class. | |||

A randomized trial of class 2 and class 3 elastic compression in the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | √ | Randomization was computer generated, and patients were randomized into two groups. | ||

| 2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | √ | The two study groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, general medical history, previous episodes of ulceration, size of the ulcer and duration of the ulcer, which can be seen from the Characteristics of the groups (Table I) in the original text. | |||

| 3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | Results are described in the form of combining text and pictures. The content is detailed, and the primary outcome and secondary outcome data are complete. | |||

| 4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | √ | Whether the outcome assessors in the article knows who is receiving which interventions are accepting. | |||

| 5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | √ | During the 5‐year follow‐up, 28 patients did not comply with the compression treatment. | |||

Clinical and cost‐effectiveness of compression hosiery versus compression bandages in treatment of venous leg ulcers (Venous leg Ulcer Study IV, VenUS IV): a randomized controlled trial.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | √ | Randomization was done with a prevalidated computer program and participants were stratified by ulcer duration and ulcer area with permuted blocks (block sizes four and six), because these criteria are known predictors of ulcer healing. They could not mask participants or nurses to the allocated treatment. | ||

| 2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | √ | According to Table 1, we can see that the baseline characteristics of the two groups are comparable | |||

| 3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | Results are described in the form of combining text and pictures. The content is detailed, and the primary outcome and secondary outcome data are complete. | |||

| 4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | √ | Two assessors undertook central, independent, masked assessment of the photographs for healing and date, with a third assessor resolving disagreements. | |||

| 5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | √ | According to Figure 1, 160 discontinued intervention (moved to another treatment) | |||

Application of lower extremity muscle training program in wound treatment of patients with venous ulcer of lower extremity.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | √ | Researchers use random digital tables to divide patients into two groups. Because intervention is easily recognized by participants, only blind laws are implemented on outcomes indicators. | ||

| 2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | √ | Patients' age and other population data and formal diseases, wound‐sized, the number of ulcers and other disease‐related information, there is no statistical difference in differences (p > 0.05). | |||

| 3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | The results only accounted for the disease‐related measurement data before and after the intervention, and did not describe the patient's population characteristics and information. | |||

| 4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | √ | Not mentioned in the study. | |||

| 5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | √ | The observation group shed 5 patients, and 4 patients were dropped off in the control group. The remaining participants had good compliance. | |||

Supervised exercise training as an adjunct therapy for venous leg ulcers: a randomized controlled feasibility trial.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative randomized controlled trials | 1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | √ | Following baseline assessments, participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to an intervention group or a control group. Participants were stratified by ulcer size (maximum ulcer diameter 1–3 cm or >3 cm in any direction). Outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation. However, the grouping method is only described as random, and it is not mentioned specifically. | ||

| 2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | √ | Participant characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 4; the groups were well balanced for most variables except QoL. | |||

| 3. Are there complete outcome data? | |||||

| 4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | √ | Outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation. | |||

| 5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | √ | Seventy‐two per cent of the exercise group participants attended all scheduled exercise sessions. Loss to follow‐up was 5%. | |||

The experience of self‐management following venous leg ulcer healing.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Qualitative | 1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | √ | This research was a qualitative, exploratory study. | ||

| 2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | √ | In depth interviews were conducted with participants from July–September 2010. The interview commenced with the interviewer asking: ‘What has it been like looking after your leg since your venous ulcer healed?’ A purpose designed interview guide was used to prompt conversation when necessary. | |||

| 3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | √ | The first three participant transcripts were reviewed following each interview, resulting in minor adjustments to the interview guide. Thematic analysis was employed to discern common themes and hypotheses that were solidly grounded in these data. Data from the interview transcripts were organized into a system of categories and codes. From these categories and codes, provisional hypotheses were proposed. As well as analysing individual interviews, comparative analyses were also undertaken. | |||

| 4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | √ | The quotes provided to justify the themes were adequate. | |||

| 5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | √ | It has been clear links between data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation. | |||

Education project to improve venous stasis self‐management knowledge.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Quantitative non‐randomized | 1. Are the participants representative of the target population? | √ | The target population was persons diagnosed with a first‐time venous ulcer. Potential subjects were recruited by staff nurses working for an outpatient facility providing care for patients with venous ulcers. 35 was 30 bits in the research object. The reason is: 1 declined owing to concerns that participation would require too much time, 1 withdrew during the intervention, 2 were transferred to long‐term care during the follow‐up period, and 1 expired. | ||

| 2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | √ | Outcome measures were: (1) scores on the Checklist for Patient Learning measured at baseline, immediately following the intervention, and at 2 and 9 weeks follow‐up, (2) wound healing as reported by participants at 2‐ and 9‐week follow‐up, and (3) wound recurrence as reported by participants at 9‐week follow‐up. Wound healing was assessed by the nurse providing care and reported to the principal investigator by the participant. Wound healing was operationally defined as a reduction in wound size noted by the nurse and reported to the principal investigator by participants. Wound recurrence was operationally defined as occurrence of another wound at the same site. | |||

| 3. Are there complete outcome data? | √ | Data collection occurred in 4 phases: (1) baseline, (2) immediately following the educational intervention, (3) at 2 weeks postintervention and (4) at 9 weeks postintervention. | |||

| 4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | √ | Unpropped in the article. | |||

| 5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | √ | The educational intervention lasted approximately 45 min; it included a brochure and handout. | |||

Adherence to leg ulcer lifestyle advice: qualitative and quantitative outcomes associated with a nurse‐led intervention.

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Responses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Can't tell | Comments | ||

| Screening questions (for all types) | S1. Are there clear research questions? | √ | |||

| S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | √ | ||||

| Further appraisal may not be feasible or appropriate when the answer is ‘No’ or ‘Can't tell’ to one or both screening questions. | |||||

| Mixed methods | 1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | √ | To document the changes associated with the intervention, a qualitative evaluation and a pre–post‐test design were used. | ||

| 2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | √ | During the data collection‐analysis, at the end of the nursing intervention, semi‐structured interviews were held with 25 patients in their home. All quantitative data about wearing compression, performing leg exercises, leg elevation, physical activity, pain and ulcer size were collected three times: at baseline (at least 1 week before the start of the intervention), at the end of the intervention (starting within 1 week after the last visit) and 3 months later. | |||

| 3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | √ | Inductive content analysis was used Qualitative data were entered into QSR N6. Quantitative data were analysed with SPSS SPSS version 15.0. | |||

| 4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | √ | It is no divergence. | |||

| 5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | √ | The quantitative component is rated high quality and the qualitative component is rated low quality. | |||

He B, Shi J, Li L, et al. Prevention strategies for the recurrence of venous leg ulcers: A scoping review. Int Wound J. 2024;21(3):e14759. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14759

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Donnell TF Jr, Passman MA, Marston WA, et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery (R) and the American venous forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2 Suppl):3S‐59S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim CS, Baruah M, Bahia SS. Diagnosis and management of venous leg ulcers. BMJ. 2018;362:k3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schneider C, Stratman S, Kirsner RS. Lower extremity ulcers. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(4):663‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lal BK. Venous ulcers of the lower extremity: definition, epidemiology, and economic and social burdens. Semin Vasc Surg. 2015;28(1):3‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finlayson K, Wu ML, Edwards HE. Identifying risk factors and protective factors for venous leg ulcer recurrence using a theoretical approach: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(6):1042‐1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Finlayson K, Edwards H, Courtney M. Factors associated with recurrence of venous leg ulcers: a survey and retrospective chart review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(1078):1071‐1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Renner R, Gebhardt C, Simon JC, Seikowski K. Changes in quality of life for patients with chronic venous insufficiency, present or healed leg ulcers. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7(11):953‐961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai PL, Hitchman LH, Mohamed AH, Smith GE, Chetter I, Carradice D. Endovenous ablation for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;7(7):CD009494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirsner RS, Vivas AC. Lower‐extremity ulcers: diagnosis and management. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(2):379‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barwell JR, Davies CE, Deacon J, et al. Comparison of surgery and compression with compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9424):1854‐1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan SSJ, Yap CJQ, Tan SG, Choke ETC, Chong TT, Tang TY. The utility of endovenous cyanoacrylate glue ablation for incompetent saphenous veins in the setting of venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(6):1041‐1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamamoto K, Miwa S, Yamada T, et al. A strategy to enable rapid healing and prevent recurrence of venous ulcers. Wounds. 2022;34(4):99‐105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dahm KT, Myrhaug HT, Stromme H, Fure B, Brurberg KG. Effects of preventive use of compression stockings for elderly with chronic venous insufficiency and swollen legs: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Behairy AS, Masry SE. Impact of educational nursing intervention on compression therapy adherence and recurrence of venous leg ulcers: a quasi‐experimental study. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2022;8(2):120‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonkemeyer Millan S, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(5):298‐305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018. Registration of copyright (#1148552). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Milic DJ, Zivic SS, Bogdanovic DC, Lazarevic MV, Ademi BN, Milic ID. The influence of different sub‐bandage pressure values in the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration‐a ten year follow‐up. Phlebology. 2023;38(7):458‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Milic DJ, Zivic SS, Bogdanovic DC, Golubovic MD, Lazarevic MV, Lazarevic KK. A randomized trial of class 2 and class 3 elastic compression in the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(6):717‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ashby RL, Gabe R, Ali S, et al. Clinical and cost‐effectiveness of compression hosiery versus compression bandages in treatment of venous leg ulcers (venous leg ulcer study IV, VenUS IV): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):871‐879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klonizakis M, Tew GA, Gumber A, et al. Supervised exercise training as an adjunct therapy for venous leg ulcers: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Brit J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1072‐1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xin L, Jingfang J, Hua L, Shuyi L, Zhaoyu L. Application of lower extremity muscle training programin wound treatment of patients with venous ulcer of lower extremity. Milit Nurs. 2021;38(2):14‐17. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Probst S, Sechaud L, Bobbink P, Skinner MB, Weller CD. The lived experience of recurrence prevention in patients with venous leg ulcers: an interpretative phenomenological study. J Tissue Viability. 2020;29(3):176‐179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zulec M, Rotar‐Pavlic D, Puharic Z, Zulec A. “Wounds home alone” why and how venous leg ulcer patients self‐treat their ulcer: a qualitative content study. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2019;16(4):559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suehiro K, Morikage N, Harada T, et al. Self‐care‐based treatment using ordinary elastic bandages for venous leg ulcers. Ann Vasc Dis. 2017;10(3):229‐233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kapp S, Miller C. The experience of self‐management following venous leg ulcer healing. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(9–10):1300‐1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gonzalez A. Education project to improve venous stasis self‐management knowledge. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2014;41(6):556‐559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van Hecke A, Grypdonck M, Beele H, Vanderwee K, Defloor T. Adherence to leg ulcer lifestyle advice: qualitative and quantitative outcomes associated with a nurse‐led intervention. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(3–4):429‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Phillips TJ, et al. What's new: management of venous leg ulcers: treating venous leg ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(4):627‐640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weller CD, Richards C, Turnour L, Team V . Patient explanation of adherence and non‐adherence to venous leg ulcer treatment: a qualitative study. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:663570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Probst S, Allet L, Depeyre J, Colin S, Buehrer SM. A targeted interprofessional educational intervention to address therapeutic adherence of venous leg ulcer persons (TIEIVLU): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20(1):243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coelho Rezende G, O'Flynn B, O'Mahony C. Smart compression therapy devices for treatment of venous leg ulcers: a review. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11(17):e2200710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qiu Y, Team V, Osadnik CR, Weller CD. Barriers and enablers to physical activity in people with venous leg ulcers: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;135:104329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kelechi TJ, Mueller M, Madisetti M, Prentice M. Efficacy of a self‐managed cooling intervention for pain and physical activity in individuals with recently healed chronic venous leg and diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized controlled trial. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2022;49(4):365‐372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kapp S, Prematunga R, Santamaria N. The “self‐treatment of wounds for venous leg ulcers checklist” (STOW‐V checklist V1.0): part 2‐the reliability of the checklist. Int Wound J. 2022;19(3):714‐723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.