Abstract

A critical step in the drug design for SARS-CoV-2 is to discover its molecular targets. This study comprehensively reviewed the molecular mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2, exploring host cell tropism and interaction targets crucial for cell entry. The findings revealed that beyond ACE2 as the primary entry receptor, alternative receptors, co-receptors, and several proteases such as TMPRSS2, Furin, Cathepsin L, and ADAM play critical roles in virus entry and subsequent pathogenesis. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 displays tropism in various human organs due to its diverse receptors. This review delves into the intricate details of receptors, host proteases, and the involvement of each organ. Polymorphisms in the ACE2 receptor and mutations in the spike or its RBD region contribute to the emergence of variants like Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron, impacting the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2. The challenge posed by mutations raises questions about the effectiveness of existing vaccines and drugs, necessitating consideration for updates in their formulations. In the urgency of these critical situations, repurposed drugs such as Camostat Mesylate and Nafamostat Mesylate emerge as viable pharmaceutical options. Numerous drugs are involved in inhibiting receptors and host factors crucial for SARS-CoV-2 entry, with most discussed in this review. In conclusion, this study may provide valuable insights to inform decisions in therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Entry route, Spike, ACE2

1. Introduction

The emergence of pandemic infectious diseases poses a severe threat to global public health and the economy [1]. The recent COVID-19 pandemic recorded over 696 million cases and 6.9 million deaths (World Health Organization, COVID-19 situation reports). Preceding this, SARS-CoV (2002) and MERS-CoV (2012) were notable epidemics [2]. Current evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2, causing the COVID-19 pandemic, exhibits higher severity and prevalence compared to MERS-CoV. The transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 is greater than that of MERS-CoV in the Middle East but lower in the Republic of Korea. This variability may be attributed to mutations in host or virus proteins, diverse entry routes, and variations in host cell receptors [3,4]. SARS-CoV-2 primarily interacts with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, while MERS-CoV binds to the Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) receptor [[5], [6], [7]]. Docking studies reveals a significant interface between the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and the DPP4 complex, indicating close similarity with other coronaviruses [8].

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, both members of the Coronaviridae family, share a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The genome of SARS-CoV-2 encodes 16 non-structural proteins, 4 structural proteins (Spike, Membrane, Envelope, and Nucleocapsid), and 9 accessory proteins [2,9]. Within the virus's structural proteins, Spike holds particular significance as it facilitates the interaction between the virus and host tissue receptors, leading to host invasion. The proteolytic activation of the spike, cleaving it into S1 and S2, is crucial and primarily governed by host cell proteases. Consequently, the pathogenesis of the coronavirus is fundamentally controlled by the interactions between host cell receptors and the spike protein [10,11]. The main role of the S1 subunit is to engage with the host cell's surface receptors through a specific receptor-binding domain (RBD), while the S2 subunit mediates the fusion of both virus-cell and cell-cell membranes [12].

Recent findings indicate the involvement of various molecules in the penetration of the SARS-CoV-2 virus into host cells. These include ACE2 (the most widely recognized), along with ASGR1, KREMEN1, AXL, CD147, and host cell proteases [13]. The clinical outcomes of COVID-19 exhibit variation among different populations and even within a single population. This suggests a genetic susceptibility in certain individuals to COVID-19 infection across diverse populations [14]. Polymorphisms in various receptors and co-receptors of SARS-CoV-2, influencing the virus's entry into diverse tissues among different individuals, may contribute to the observed clinical variability in the disease across subjects [15]. Unfortunately, the restricted understanding of the human molecular targets of SARS-CoV-2 hinders the development of host-dependent personalized therapies [16]. In this study, our objective is to bridge this knowledge gap by examining recent findings related to a crucial stage in viral infection, specifically the entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Our aim is to identify potential entry interactions, assisting researchers in designing effective prophylactic or therapeutic strategies. Additionally, we will provide a detailed discussion on the majority of molecules implicated in virus entry, along with an exploration of the organs involved in COVID-19 disease.

2. Methodology

Two investigators conducted separate searches for potentially eligible studies across databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science (ISI) from inception to February 28, 2023. To pinpoint studies examining the interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 spike and human proteins, a combination of Mesh terms and keywords (SARS-CoV-2 OR Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) AND (Entry OR Route OR Mechanisms OR Receptor OR Interaction OR Attachment OR Binding) was applied. Additionally, a manual review of the references in the retrieved articles and relevant previous reviews as well as combination search with different human body organs was carried out to minimize the risk of overlooking studies. The management of records was facilitated using EndNote software, version X7. Following the removal of duplicates, two independent authors screened the search results based on title/abstracts and excluding irrelevant records. Studies focusing on polymorphisms or mutations in both the SARS-CoV-2 spike and human targets of the spike, including ACE2, TMPRSS2, Furin, and CD147, were selected.

3. SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and mutations affecting its binding

The spike glycoprotein plays a crucial role in the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2, encompassing virus attachment, fusion, and entry into the host cell [17,18]. The spike proteins undergo direct exposure to the host immune system and neutralizing antibodies [19]. The spike protein is initially synthesized as a precursor consisting of 1273 amino acids within the confines of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER). Subsequent to this synthesis, a series of modifications transpire in the Golgi complex, a process inclusive of cleavage into the S1 and S2 subunits facilitated by furin or furin-like proteases [20,21]. This cleavage event is orchestrated by the insertion of 12 nucleotides encoding four amino acid residues, specifically PRRA, demarcating the boundary between S1 and S2 [22,23]. The functional roles of these subunits are pivotal, with the S1 subunit binding the virus to the host receptor's surface, while the S2 subunit mediates the fusion between the virus and host cell membranes [24]. SARS-CoV-2 evolutionary modifies itself to evade the host immune system, introducing amino acid substitution in the Spike structure. Notably, the Asp614Gly substitution is implicated in influencing virus transmission speed [25]. Spike proteins have interaction with the positions 30–41 of the ACE2 protein [26]. The tight connection at the ACE2-SARS-CoV-2 interface is facilitated by three hydrogen bonds involving Gln493, Tyr449, and Gln498 of Spike, and Glu35, Lys353, and Asp38 of ACE2, along with a salt bridge formed between Asp30 of ACE2 and Lys417 of the spike [27]. The glycans are also essential for ACE2-virus surface interaction. They influence the conformation of the ACE2 receptor to allow the interaction of spike with ACE2 [28]. The glycans can modulate Spike-ACE2 interactions by masking polypeptide epitopes [29]. The negatively charged human cells bind to the positively charged O-linked glycan domain of the Spike [30]. The conformational dynamics of the RBD are modulated by N-glycans at sites N165 and N234, which play a crucial role in ACE2 recognition. A deletion in these regions can decrease the binding affinity of ACE2 [31]. ACE2-K26R mutation, observed in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, result in reduced electrostatic attraction of SARS-CoV-2/ACE2, while mutations D206G, I468V, G211R, R219C, and K341R increase it [32]. Furthermore, three missense changes N720D, Y26R, and G211R, common in the Italian population, are predicted to interfere with ACE2 protein stabilization [33]. Since the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, the virus has undergone numerous mutations, resulting in various variants classified as Alpha (B.1.1.7 and Q lineages), Beta (B.1.351 and descendent lineages), Gamma (P.1 and descendent lineages), Epsilon (B.1.427 and B.1.429), Eta (B.1.525), Iota (B.1.526), Kappa (B.1.617.1), Mu (B.1.621, B.1.621.1), Zeta (P.2), Delta (B.1.617.2 and AY lineages) [34] and Omicron (strain B.1.1.529). First identified in South Africa on November 9, 2021, the Omicron variant has emerged as the sole current variant of concern. Notably, the Omicron variant demonstrates a transmission capacity 3–4 times higher than that of the delta variant, contributing to its rapid global spread and prevalence [35].

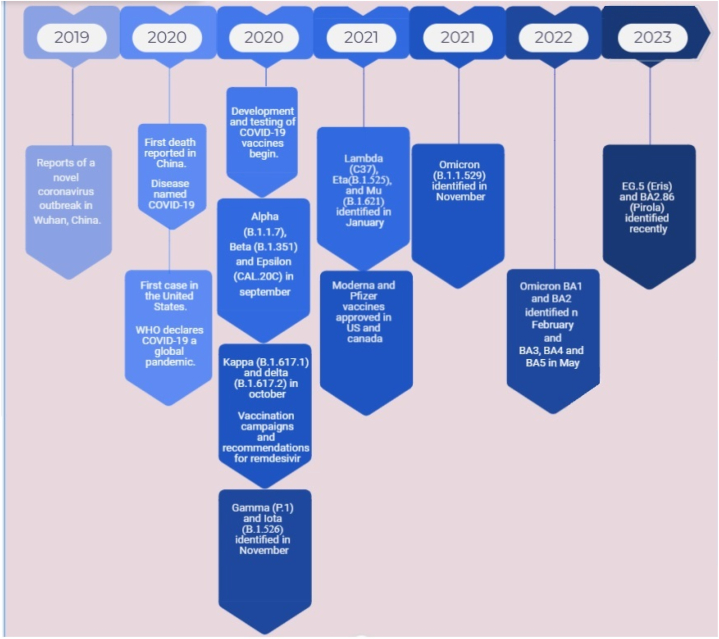

Currently, there are several sub-variants of the Omicron. In comparison with the original Omicron BA.1, BA.2 displayed the higher resistance to available vaccines and this occurred in the next emerged variants. In 2023, a new Omicron variant called EG.5 (known as “Eris”) is the dominant variant in the U.S., and scientists are monitoring another new variant called BA.2.86 (also known as “Pirola”) (Fig. 1). Evidence has shown that this type of variant in some subjects causes more serious complications for young people, necessitating adjustments to health protocols to a certain extent [35,36].

Fig. 1.

History of emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

These variants are known with the key mutations found in their spike which is listed below.

-

1.Alpha Variant (B.1.1.7):

-

•Key mutation: N501Y, associated with increased binding affinity to the ACE2 receptor, possibly leading to increased transmissibility.

-

•Other mutations: Del69-70, P681H.

-

•

-

2.Beta Variant (B.1.351):

-

•Key mutation: E484K, associated with potential immune escape from neutralizing antibodies.

-

•Other mutations: N501Y, K417 N.

-

•

-

3.Gamma Variant (P.1):

-

•Key mutations: E484K, N501Y, and K417T, similar to the Beta variant.

-

•Additional mutations: L452R.

-

•

-

4.Delta Variant (B.1.617.2):

-

•Key mutations: L452R and T478K, associated with increased transmissibility and potential immune evasion.

-

•

-

5.Epsilon Variant (B.1.427 and B.1.429):

-

•Key mutation: L452R.

-

•

-

6.Iota Variant (B.1.526):

-

•Key mutations: E484K, S477 N, and D253G.

-

•

-

7.Kappa Variant (B.1.617.1):

-

•Key mutations: E484Q and L452R.

-

•

-

8.Mu Variant (B.1.621):

-

•Key mutations: E484K and N501Y.

-

•

-

9.Zeta Variant (P.2):

-

•Key mutations: E484K and D614G.

-

•

-

10.Omicron Variant (B.1.1.529):

-

•Key mutations: Omicron has a large number of mutations, including numerous changes in the spike protein (S gene), such as N501Y, E484A, K417 N, and many others.

-

•

In contrast to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 undergoes pre-activation by pro-protein convertases, particularly furin, facilitating cell entry. This characteristic reduces its reliance on target cell proteases for entry. Notably, the continuous variation in the SARS-CoV-2′ RBD results in a higher binding affinity to the host ACE2 compared to SARS-CoV, as the ACE2 site was less exposed to SARS-CoV’ RBD. These features contribute to efficient cell entry, evasion of immune surveillance, and viral widespread [37].

4. Human target proteins involved in spike interactions and drugs

4.1. ACE2; the major receptor

The aminopeptidase ACE2 acts as a functional receptor for the Spike of SARS-CoV-2 [38]. This protein plays a crucial role in regulating the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. The significance of this system in various physiological processes has sparked debate about targeting ACE2 for the treatment of COVID-19 [39]. The ACE2 regulation in human cells is associated with overexpression of some genes, including KDM5B, RAB1A, TLR3, HAT1, ADAM10, HDAC2, SIRT1, and FURIN, or downregulation of the TRIB3 gene [40]. The ACE2 gene is demonstrated to be expressed in approximately 72 human tissues, with its primary expression occurring at the surface of lung epithelial cells. Nevertheless, its protein has been identified in various other tissues, including the heart, kidney, testis, conjunctiva of the eye, cornea, interlobular pancreatic ducts, placental villi, cytotrophoblasts, syncytiotrophoblasts, extravillous trophoblasts, and at the base of ciliated fallopian tube epithelium [41,42].

As age progresses, the expression of ACE2 within the alveolar epithelial cells of the lungs, cardiomyocytes, and vascular endothelial cells increases, contributing to an age-related susceptibility to the virus [43]. It has been demonstrated that ACE2 gene polymorphisms might increase the susceptibility of individuals to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and its complexities including hypertension, multi-organ failure, and cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions [44,45]. Amino acid substitution in the human ACE2 protein, such as K26R, I21V, E23K, S19P, T27A, T92I, Q102P, H378R, and N64K, have been linked to an increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. Conversely, other ACE2 residue substitutions, including K31R, E35K, N33I, H34R, M62V, E37K, D38V, Y50F, D355 N, N51S, K68E, Y83H, G326E, G352V, F72V, Q388L, and D509Y, are considered protective mutations due to their association with reduced binding affinity to the Spike protein [44,46].

Notably, the N720D variant in the C-terminal Colectin-like domain (CLD) of ACE2 has the potential to impact its stability and flexibility. This alteration further creates a more favorable site for TMPRSS2 binding, Spike protein cleavage, and subsequent viral entry [47]. The RBD segment which is located within the residues 318–510 of the Spike protein, undergoes frequent mutations and plays a pivotal role in facilitating virus attachment to ACE2 [48]. During the initial fusion process between the Spike and ACE2 receptor, only 27 residues (13 in Spike, 14 in ACE2) are actively involved [49]. However, certain mutations in the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 have been identified to enhance its affinity for ACE2, consequently increasing its infectiousness [50]. In-silico models have proposed that targeting the hot spot 353 residue location to inhibit the recognition of Spike by ACE2 could be an effective strategy to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection [51]. Interestingly, in a phase II clinical trial, the administration of recombinant human ACE2 demonstrated a reduction in systemic inflammation among COVID-19 patients [52]. Molecular docking studies have revealed that remdesivir and ribavirin exhibit higher molecular binding energies to ACE2 [53]. Additionally, Sphingosine has been shown to prevent the interaction between ACE2 and the RBD segment [54]. Certain allelic variants of the ACE2 gene, such as rs73635825 and rs143936283, provide a structural basis for potential resistance against SARS-CoV-2 infection mediated by ACE2 [38]. Garcinia biflavonoid-2 (GB-2), containing flavin, has demonstrated the ability to inhibit the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 genes both in vitro and in vivo without cytotoxicity, making it a potential candidate drug for preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection [55]. In a study conducted in 2023, Wu et al. found that GB-2 reduced the entry efficiency of the Omicron variant (BA.1) of SARS-CoV-2 with the N501Y, K417 N, E484A, G339D, Q493R, G496S, Q498R mutations and inhibited the binding between ACE2 and the RBD [56]. Soluble ACE2 isoforms, generated by removing specific exons in the 3′UTR of ACE2 through alternative splicing, suggest that Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides (SSOs) could serve as a therapeutic strategy [57].

4.2. Alternative SARS-CoV-2 receptors and co-receptor

Due to the diverse organ tropisms observed in SARS-CoV-2 infections involving various organs, the virus utilizes multiple receptors and co-receptors [18]. Apart from ACE2, researchers has explored alternative molecules that may function as receptors for SARS-CoV-2, including ASGR1, KREMEN1, and AXL [13,58]. A study by Gu et al. demonstrated elevated expression of ACE2, KREMEN1, and ASGR1 receptors in airway epithelial secretory cells and macrophages [59]. Furthermore, investigations indicated that the combined function of these three molecules ASGR1, KREMEN1, and AXL (ASK) exceeds that of individual molecules, potentially contributing to the complexity of COVID-19 infections and their associated complications [59]. The tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO, known as AXL, plays a crucial role in SARS-CoV-2 infection through its interaction with the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein in human primary lung epithelial cells [60]. Given the impact of the AXL receptor on COVID-19 infection, the AXL inhibitor bemcentinib has been recently explored as a potential treatment and is currently in phase II trials [61]. In vitro experiments have demonstrated the efficacy of reducing viral infection in pulmonary epithelial cells by either knocking down Axl or adding it in soluble recombinant form to the cell culture. Interestingly, the natural ligands of Axl, Gas6 and protein S, do not bind to SARS-CoV-2 [62].

Aminopeptidase N (APN) is a member of zinc peptidase family which acts as the receptor for several coronaviruses, especially 229E, an enteropathogenic coronaviruse [63]. Blocking APN have been revealed as a prophylaxis strategy in high-risk individuals infected by SARS-CoV [64]. However, the specific role of APN in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis remains undetermined. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) and glutamyl aminopeptidase (ENPEP) were identified as the candidate co-receptors for human SARS-CoV-2 [65,66]. Additionally, integrin has been proposed as an alternative receptor for the virus, potentially influencing its transmission and pathology [67]. Given the presence of the integrin-binding motif on the surface of the Spike, testing Integrin binding experimentally has been suggested as a potential therapeutic target [56]. Recent findings also indicate that CD147 (basigin) may serve as an additional entry point for SARS-CoV-2 infection through interaction with the viral spike [68].

4.3. Human host cell proteases

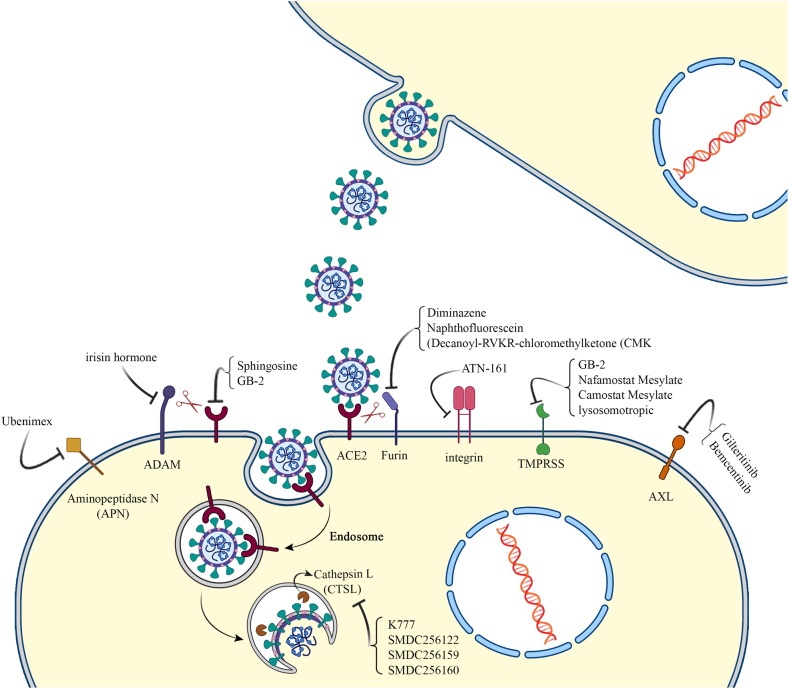

4.3.1. Transmembrane protease serine or TMPRSS family (TMPRSS2, TMPRSS4)

In SARS-CoV-2 entry, early pathway is used in the presence of TMPRSS2. ACE2 can be shed by ADAM17 and TMPRSS2 proteases [69]. TMPRSS2 cleaves and activates the Spike of coronaviruses es well as SAR-CoV-2 at S29 location, thereby leading to substantial structural rearrangement for ACE2 binding and membrane fusion viral entry [70]. TMPRSS2 is primarily expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells [71] and its inhibition has been shown to prevent certain coronaviruses from entering host cells [72]. Interestingly, smoking has been indicated to increase expression levels of TMPRSS4 in the bronchial epithelial cells, rendering smokers more susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 infection [73]. Both TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 can further enhance SARS-CoV-2 infection in human small intestinal enterocytes [74]. Several genetic variants from TMPRSS2 genes, including rs112657409, rs11910678, rs61735792, rs61735794, rs75603675, rs77675406, rs464397, rs469390, rs2070788, rs383510, and rs713400, have been identified as potential influencers of TMPRSS2 expression levels, subsequently altering individuals' susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection [[75], [76], [77]]. Approved TMPRSS2 inhibitors, including nafamostat mesylate and camostat mesylate are under clinical trials and caused reduced death rate [78] (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Shows human target proteins involved in spike of SARS-CoV-2 interactions and their inhibitors.

| Function | Protein | Candidate drugs for blocking | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | ACE2 | Sphingosine, GB-2 | [56,79,80] |

| ASGR1 | Not currently available | ||

| KREMEN1 | Not currently available | ||

| AXL | Gilteritinib, Bemcentinib (in phase II trials) | [62,81,82] | |

| Aminopeptidase N (APN) | Ubenimex (its derivatives) | [83] | |

| integrin | ATN-161 | [84] | |

| Co-receptors | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) | Not currently available | |

| glutamyl aminopeptidase (ENPEP) | Not currently available | ||

| CD147 (basigin) | Not currently available | ||

| Human host cell proteases | TMPRSS family | GB-2, Nafamostat Mesylate, Camostat Mesylate, lysosomotropic | [78,80,85] |

| Furin | Diminazene, Naphthofluorescein, Decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) | [86,87] | |

| A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase (ADAM) | irisin hormone | [40,88] | |

| Cathepsin L (CTSL) | K777, SMDC256122, SMDC256159, SMDC256160, chlorpromazine, fluoxetine and Active-6 | [89,90,91,92] | |

Fig. 2.

SARS-CoV-2 receptors and co-receptors on the surface and in the host cells and their potent inhibitors.

4.3.2. Furin

The serine proteases, notably Furin, and related pro-protein convertases (PCs) such as PC2, PC1/3, PC4, PACE4, PC5/6, and PC7 cleave Spike at the S1/S2 site, making them essential for viral entry [93]. In the case of MERS-CoV, Furin and other pro-protein convertases process the S1/S2 site, with the S2 site cleaved upon viral entry [94]. It has been indicated that the Spike of SARS-CoV-2 contains a furin cleavage site (PRRA) that is not detectable in other SARS-like CoVs [95]. The PRRA site promotes viral entry and cell to cell fusion (syncytium formation) but is not critical for infection [96,97]. Some scientists believe that furin-mediated cleavage at the modified R667 position of the Spike enhances membrane fusion activity without affecting virion entry [98]. The variants of SARS-CoV-2 lacking furin cleavage site have shown reduced replication in human respiratory cell lines [99]. Interestingly, the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein mutant D614G, which is a virulent strain of SARS-CoV-2, has a higher affinity PRRA site for furin [100,101]. The use of furin inhibitors such as diminazene, naphthofluorescein, and decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (CMK) has been proposed to block the cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protei and subsequently reducing virus replication and cytopathic effects [102,86].

4.3.3. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)

ADAM, a family of transmembrane proteins, is widely expressed in various tissues including vascular smooth muscle cells, lung macrophages, and bronchial epithelial cells. ADAM proteins, such as ADAM-17, are responsible for cleaving the ectodomains of transmembrane proteins like ACE2. Stimulating ADAM-17 can increase ACE2 shedding, making it an appealing target for pharmacologic intervention [103,104]. There is a suggested association between ADAMTS13, a protein containing a thrombospondin type1 motif, member 13, and the promotion of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Reducing ADAMTS13 levels has been proposed as a strategy to lower COVID-19 mortality [105,106]. Additionally, the hormone Irisin, secreted during exercise, has been found to modulate the expression of ADAM genes [40]. In a 2023 trial, Alves et al. demonstrated that Irisin may also mitigate excessive inflammation associated with COVID-19, potentially reducing the severity of the disease's outcomes [88].

4.3.4. Cathepsin L (CTSL)

Cathepsin L (CTSL) is activated in the low-pH environment of the endosome and triggers late pathways [107]. As a lysosomal cysteine protease, CTSL plays a crucial role in cleaving the S1 subunit of the Spike protein, necessary for viral entry, virus and endosomal membrane fusion, and viral RNA release for the next round of replication [89]. CTSL inhibitors have been demonstrated to block the entry of SARS-CoV, indicating the virus utilizes CTSL to infect ACE2-expressing cells [108,109]. Following SARS-CoV-2 infection, circulating CTSL levels increase, and higher levels are associated with disease severity [110]. CTSL inhibitors such as K777 and its derivatives, including SMDC256122, SMDC256159, and SMDC256160 have successfully inhibited virus entry into the host cells. However, the simultaneous use of serine protease and CTSL inhibitors is suggested as a potentially safer and much more effective therapy compared to other available therapies for blocking viral entry [111]. Lysosomotropic cathepsin L inhibitors, including chlorpromazine and fluoxetine, are under clinical trials [90]. In an in vitro experiment, fluoxetine demonstrated successful inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 gene expression. Additionally, fluvoxamine (Active-6) may exert an immunomodulatory effect by strongly binding to the sigma 1 receptor (S1R), known for significant roles in immune system modulation and suppression of inflammatory cytokines. Both fluoxetine and fluvoxamine can influence intravesicular pH, hindering viral compartment fusion and limiting internal virus spread. Consequently, the study have reported that fluoxetine can reduce mortality associated with COVID-19 infection [91].

4.3.5. Latest drugs in clinical trials

In addition to the ongoing exploration of novel treatment modalities involving new pharmaceuticals, immunotherapeutic agents, and host-directed therapeutic approaches, the global scientific community is actively investigating the potential effectiveness of pre-existing drugs against SARS-CoV-2. Our search on ClinicalTrials.gov has identified numerous clinical trials dedicated to evaluating drugs for COVID-19 treatment. These drug candidates can be broadly categorized into two main groups: those designed to directly impede the viral replication cycle, and those employing immunotherapy strategies to bolster the innate antiviral immune responses or mitigating damage triggered by dysregulated inflammatory reactions. Some of these newest drugs with promising outcomes are DFV890 (Phase II), TD-0903 (Phase II), RBT-9 (Phase II), M5049 (Phase II), SNG001(Phase II), COVID19-0001-USR (Phase II), LAU-7b (Phase II), and BLD-2660 (Phase II), and Paxlovid (phase III/IV) [112,113].

5. SARS-CoV-2 tropism and entry into different human tissues

About 15–20% of the SARS-CoV-2 patients have lung involvement, 10% have asymptomatic infection, and 5–10% develop multiple organ failure [114,115]. Investigations into SARS‐CoV‐2 entry mechanisms have predominantly concentrated on ACE2 and priming proteases, both of which exhibit notably low expression levels, especially in respiratory epithelial cells. This prompts the consideration that additional cofactors might be necessary to aid SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into cells with limited ACE2 expression. A study on normal human tissues reported ACE2 as the central receptor and neuropilin-1, GRP 78, CD147 and other SARS-CoV-2 receptors expressed at a different levels in various organs [116,117]. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid has been identified in a range of cell types, showing a strong colocalization with various cellular components, including mitochondrial proteins, lipid droplets (LDs), and several host proteins known for their implications in inflammation, tissue repair, and the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle. These host proteins contain vimentin, fibronectin, NLRP3, LC3B, DDX3X, and PPARγ, which their potential role in the interplay between viral infection, inflammation, and pathogenesis has been evaluated [115]. SARS-CoV-2 targets different cells in various tissue types, including lung epithelial and endothelial cells, as well as lipogenic fibroblast-like cells (FLCs) exhibiting characteristics similar to lipofibroblasts. These cells feature activated PPARγ signaling and the presence of lipid droplets (LDs) [118]. Furthermore, potential targets of SARS-CoV-2 include lung fibroblast-like cells (FLCs) expressing fibronectin and vimentin, macrophages exhibiting NLRP3- and IL1β-induced responses, regulatory cells with immune-checkpoint proteins involved in lung repair and contributing to inflammatory responses, CD34+ liver endothelial cells and hepatocytes expressing vimentin, renal interstitial cells, and the juxtaglomerular apparatus. These diverse cell types highlight the virus's ability to interact with various tissues and cell populations within the body [119]. These observations suggest that SARS-CoV-2 directly impacts crucial functions in the lungs, kidneys, and liver, implicating these organs in COVID-19 pathogenesis. The intricate interactions between the virus and various cellular components highlight the complexity of its actions within the human body, potentially influencing disease severity. Patients with COVID-19 have experienced a range of complications, including myocarditis, encephalopathy, Prion-like disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenia, and mucormycosis, both during and after the acute phase. Certain symptoms during the acute phase, such as vomiting, throat pain, diarrhea, gastrointestinal symptoms, dyspnea, or headache, may be associated with the development of long-term symptoms known as long COVID [23,24]. In-depth analysis reveals that these symptoms, as well as cough, muscle pain, and weakness, are common among both hospitalized and non-hospitalized long COVID patients. Moreover, individuals who experienced mental health issues diagnosed during the acute phase of COVID-19 faced an increased risk of developing long COVID. Recent analysis of electronic health records from primary care practices in the UKsupports this finding, indicating that conditions like dementia and impaired mental health in COVID-19 survivors pose significant risk factors for complications and mortality compared to patients hospitalized for influenza. These associations underscore the potential psychobiological mechanisms linking COVID-19 to neurological damage and the development of persistent long COVID symptoms [25].

5.1. Lung

The airway epithelial cells and lung alveoli express low levels of ACE2 but elevated levels of TMPRSS2, GRP78, and CD147 that facilitate the entrance of the SARS-CoV-2 [120]. The main target cells for SARS-CoV-2 are Human alveolar epithelial cells [121]. Interacting with ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 can disrupt the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and activates certain cell signaling pathways that are related to lung fibrosis [122].

5.2. Cardiovascular

Cardiac damage in SARS-CoV-2 infection has been attributed to various mechanisms, including Spike-ACE2 interaction, cytokine storm, and hypoxemia [123]. While the ACE2 gene is more highly expressed in the human heart than the lung, TMPRSS2 is rarely expressed. The minimal coexpression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 genes in cardiac cells suggests an alternative viral entry mechanism in SARS-CoV-2 infection within the heart. It is plausible that the virus utilizes other entry factors, such as cathepsin L, which are notably abundant in cardiomyocytes, rather than relying on the TMPRSS2-dependent pathway. This highlights the intricate ways in which SARS-CoV-2 may affect cardiac tissues [124]. Analysis of heart tissue from COVID-19 patients reveals changes in cell composition, including a significant decrease in cardiomyocytes and pericytes, along with an increase in vascular endothelial cells. Notably, viral RNA is not detected in these cell types. Reports suggest the presence of infected nonmuscle cells in COVID-19 cardiac tissue, while another report indicates SARS-CoV-2 antigen in cardiomyocytes, suggesting potential direct myocardial damage [125]. Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived heart cells show susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, resulting in myofibrillar fragmentation and nuclear disruption, potentially linked to dysregulation of genes associated with the nucleoskeleton-cytoskeleton complex. This complex interplay also sheds light on mechanisms underlying COVID-19-related cardiac complications [126].

5.3. CNS

The neurotropic capability of SARS-CoV-2 mainly arise from its binding potential to the transmembrane receptor neuropilin-1 (NRP1), which is highly expressed in the olfactory epithelium, olfactory tubercles, and paraolfactory [127]. The virus is thought to potentially spread to the central nervous system (CNS) via the olfactory nerve [128]. There are several studies reported CNS complications such as encephalopathy, progressive dementia, Prion-like disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome after COVID-19 acute infection and vaccination [23,24]. Recent preliminary findings also indicate that the Spike might have a binding affinity to EGFR, c-MET, and VEGFR on glioma cells [129]. Moreover, whole RNA sequencing revealed extensive expression of SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus-associated factors, and receptors in the human dorsal root ganglion (DRG) at the lumbar and thoracic levels. Nociceptors expressing MRGPRD mRNA, which also express ACE2 mRNA, may provide a route for SARS-CoV-2 entry into neurons forming free nerve endings in the outermost layers of the skin and luminal organs. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated ACE2 expression in the limbus, conjunctiva, and cornea [130]. Although the oral cavity might be considered a potential entry point for the virus, the presence of protease inhibitors in saliva should also be taken into account, indicating a complex interplay of factors influencing viral entry [131]. Certain mutations in SARS-CoV-2 enhance the Spike protein's activity, modifying its structure for increased binding to host cells. The impact on SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion is unclear. TMPRSS2 and neuropilin-1 are present in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Potential CNS entry pathways include infected immune cells crossing the blood-brain barrier, entry into cerebrospinal fluid via the choroid plexus, trans-synaptic viral transmission from various nerves, and access to circumventricular organs lacking the BBB. ACE2 and neuropilin-1 in retinal cells and the visual system are also considered potential entry points for SARS-CoV-2 invasion [132].

5.4. Gastrointestinal tract

Active viral replication has been confirmed in both the small and large intestines, as evidenced by electron microscopy, and viral genomes have been detected in stool samples. Enterocytes, rich in ACE-2 receptors and furin (a serine protease), facilitate virus entry, with TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 expression promoting this process [74,133,134]. ACE2-expressing cells are over tenfold more prevalent in the lower gastrointestinal tract (ileum, colon, and rectum) compared to the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, and duodenum). Coexpression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 is more common in the lower gastrointestinal tract. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein has been identified in the exocrine cells of the pancreas [135].

5.5. Other SARS-CoV-2 target organs or tissues

SARS-CoV-2 entrance into podocytes and tubular epithelial cells has been associated with renal abnormalities, including hematuria, proteinuria, and acute kidney injury [136]. Reports indicate that 36–46% of COVID-19 patients experience acute kidney damage (AKI), while severe cases may also involve liver damage. Both liver cells and bile duct cells express ACE2, with higher expression levels observed in bile duct cells [137,138]. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are found in trophoblast, hypoblast, and syncytiotrophoblast tissues, raising the possibility of vertical SARS-CoV-2 transmission [139]. ACE2 is expressed in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), potentially posing a risk of infection and damage to stem cells [140]. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are present in a small population of cells in human umbilical cord blood (UCB) that can differentiate into functional EPCs and HSCs [140]. Band3 protein on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs) is considered a potential entry point for SARS-CoV-2. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike to ACE2 on platelets induces platelet activation, possibly contributing to thrombus formation and inflammatory responses in COVID-19 disease [141,142].

6. SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 expression in different ages, genders and ethnicities

Several factors, including age, gender, and ethnicity, may influence the outcome of COVID-19 disease. The location of the ACE2 gene on the X-chromosome suggests potential heterozygosity in females, differing from homozygous males [15,143]. Studies indicate that males have a higher susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in terms of mortality and the need for intensive care units. Genetic variations in essential genes like ACE2 and TMPRSS2, along with differences in immune system function, may contribute to the varying incidence and outcomes across ethnic groups [144]. Older patients with COVID-19 often face more severe disease. This may result from inadequate immune responses and higher underlying diseases. Increased expression of SARS-CoV-2 target proteins and heightened cell adhesion and stress responses contribute to this vulnerability. Additionally, reduced mitochondria and cellular replication, decreased proliferating natural killer and T cells, and increased endothelial cells and IGSF21+ dendritic cells further impact the severity in the elderly [[145], [146], [147]].

7. Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in individuals with pre-existing health conditions

Patients with underlying medical conditions, including cancer, diabetes, chronic kidney and obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart conditions, as well as those in an immunocompromised state, face an altered risk of severe COVID-19 infection. Higher mRNA and protein levels of ACE2 are observed in individuals with fundamental heart failure, suggesting an increased likelihood of severe COVID-19 in patients with primary cardiovascular disease [148]. Diabetic patients, due to the involvement of the PPAR signaling pathway in SARS-CoV-2 intrusion through the ACE2 receptor, exhibit greater vulnerability to COVID-19 infection [16,149]. Moreover, pancreatic islets of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients show significantly elevated ACE2 expression compared to healthy subjects [150]. Interestingly, cancer tissues, particularly in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and lung cancers, demonstrate lower ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression, potentially rendering them more resistant to SARS-CoV-2 infection [151].

8. SARS-CoV-2 future prospective

A comprehensive search for human interaction targets in SARS-CoV-2 entry holds significant potential to identify host proteins influencing virus tropism in diverse tissues. Therapies targeting the host-virus interaction may offer durable and broad-spectrum treatment options [152]. Key players such as ACE2, TMPRSS2, CTSL, CTSB, Furin, ADAM, heparan sulfate, and CD147 play crucial roles in SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and entry. Understanding their expression patterns can shed light on viral tropism and its impact on the severity of the disease [[153], [154], [155], [156], [157]]. Furthermore, investigations into cell-type-specific associations with sex, age, and smoking provide valuable insights into the expression levels of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and CTSL [158]. ACE2, functioning as a regulator of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, also serves as a functional receptor for SARS-CoV-2. The enriched interaction of proteins in the lung, particularly at higher expression levels, supports the idea that the virus targets proteins abundant in this tissue. The increased vulnerability of ACE2-expressing organs highlights its crucial role in the virus's entry, especially in older individuals with elevated ACE2 expression [159,160]. This understanding has led to the proposal of repurposing drugs, including recombinant soluble ACE2, TMPRSS2 inhibitors (camostat mesylate, nafamostat mesylate, antiandrogens, inhaled corticosteroids), and ADAM-17 enhancers (5-fluorouracil), along with indirect ACE2 modulators (angiotensin receptor blockers, calmodulin antagonists, and selective estrogen receptor modifiers) for targeting SARS-CoV-2 based on spike-host cell interactions [103].

Potential anti-viral therapies for SARS-CoV-2 include the application of anti-ACE2 antibodies or soluble ACE2 recombinant proteins. Inhibitors targeting ACE2, TMPRSS2, cathepsin, trypsin, furin, plasmin, factor X, and elastase show promise [54,[161], [162], [163]]. Other inhibitors, including hydroxychloroquine, hepcidin, Eltrombopag, IPB02, keto, and enol forms of curcumin, nelfinavir, cholesterol 25-hydroxylase, and various drugs like memantine, procyanidin, remdesivir, oseltamivir, and more, demonstrate potential in preventing viral entry or function [[164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172]]. Several compounds, including memantine, procyanidin, remdesivir, oseltamivir, zanamivir, Arbidol, Triazavirin, zanamivir, Mitoguazone, metformin, biguanide hydrochloride, gallic acid, caffeic acid, sulfaguanidine, heparin oligomers, riboflavin, fenoterol, cangrelor, hesperidin, vidarabine, ritonavir, and acetylcysteine, show potential as inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2, preventing virus fusion to host cells or viral entrance [[173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180], [181], [182]]. Compounds like digitoxin, diammonium, ivermectin, rapamycin, rifaximin, amphotericin B, and glycyrrhizinate show desirable features and can be considered for COVID-19 therapies [183]. A recent study proposed amantadine as a therapeutic choice because it blocks the viroporine channel of COVID-19 and inhibits the release of the viral nucleus into the cytoplasm [184]. Besides lopinavir and ritonavirm, other protease inhibitors such as Nafamostat (anticoagulant), Phillyrin and chlorogenic acid effectively can prevent SARS-CoV-2 entry by inhibiting Spike protein-mediated fusion [185,186]. Vitamin D affects the Renin-Angiotensin system, preventing inflammation and lung injury. Interleukin 7 (IL-7) aggregation induces ACE2 expression, and vitamin C can block IL-7-induced ACE2 expression [43,187]. Drugs targeting lipid metabolisms, such as statins, triacsin, orlistat, and VPS34 inhibitor, may reduce disease severity [[188], [189], [190]]. Furthermore, Natural small molecules like cyclodextrin and sterols might inhibit the attachment to host cells and reduce viral infectivity [191].

9. Conclusion

In the present study, a comprehensive and systematic review was performed to identify most of the SARS-CoV-2 targets. The detailed knowledge of biological interactions is of utmost importance while designing new drugs or virtual screening of ligand databases against a particular target. Design of experimental or in-silico interaction analysis of the mentioned targets may shed more light on developing safe and effective anti-COVID-19 therapy.

Data availability statement

Data included in the text, tables, figures, and referenced in the article.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Emad Behboudi: Writing – original draft, Validation, Conceptualization. Seyed Nooreddin Faraji: Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Gholamreza Daryabor: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Seyed Mohammad Ali Hashemi: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Maryam Asadi: Writing – original draft. Fahime Edalat: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Mohammad Javad Raee: Writing – review & editing. Gholamreza Hatam: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Seyed Nooreddin Faraji, Email: farajisn@sums.ac.ir.

Gholamreza Hatam, Email: hatamghr@sums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Shang Y., Li H., Zhang R. Effects of pandemic outbreak on economies: evidence from business history context. Front. Public Health. 2021;9:146. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.632043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.V'kovski P., Kratzel A., Steiner S., Stalder H., Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19(3):155–170. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breban R., Riou J., Fontanet A. Interhuman transmissibility of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: estimation of pandemic risk. Lancet. 2013;382(9893):694–699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen T.-M., Rui J., Wang Q.-P., Zhao Z.-Y., Cui J.-A., Yin L. A mathematical model for simulating the phase-based transmissibility of a novel coronavirus. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00640-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han D.P., Penn-Nicholson A., Cho M.W. Identification of critical determinants on ACE2 for SARS-CoV entry and development of a potent entry inhibitor. Virology. 2006;350(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R.S., Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020;94(7) doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li F., Li W., Farzan M., Harrison S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309(5742):1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron K., Rozano L., Falasca M., Mancera R.L. Does the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor binding domain interact effectively with the DPP4 (CD26) receptor? A molecular docking study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(13):7001. doi: 10.3390/ijms22137001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Coronaviruses. 2015:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millet J.K., Whittaker G.R. Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015;202:120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dessie G., Malik T. Role of serine proteases and host cell receptors involved in proteolytic activation, entry of SARS-CoV-2 and its current therapeutic options. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021;14:1883. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S308176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson C.B., Farzan M., Chen B., Choe H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lv L., Zhang L. Host proviral and antiviral factors for SARS-CoV-2. Virus Gene. 2021:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11262-021-01869-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zandi M., Behboudi E., Shojaei M.R., Soltani S., Karami H. Letter to the editor regarding“ an overview on serology and molecular tests for COVID-19: an important challenge of the current century (doi: 10.22034/iji.2021.88660.1894.)”. Iran J Immunol. 2022;19(3) doi: 10.22034/iji.2022.91791.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emadi M.S., Soltani S., Noori B., Zandi M., Shateri Z., Tabibzadeh A., Behboudi E., Erfani Y., Tabaeian S.P., Pourhossein B. Highly conserve sequences in Envelope, nucleoprotein and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal samples of the COVID-19 patients; a diagnostic target for further studies. J cell mol anesth. 2022;7(2):78–83. doi: 10.22037/jcma.v7i2.36963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayatollahi A.A., Aghcheli B., Amini A., Nikbakht H., Ghassemzadehpirsala P., Behboudi E., Rajabi A., Tahamtan A. Association between blood groups and COVID-19 outcome in Iranian patients. Future Virol. 2021;16(10):657–665. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2021-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan L., Zheng Q., Zhang H., Niu Y., Lou Y., Wang H. The SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein biosynthesis, structure, function, and antigenicity: implications for the design of spike-based vaccine immunogens. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.576622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q., Xiang R., Huo S., Zhou Y., Jiang S., Wang Q., Yu F. Molecular mechanism of interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and host cells and interventional therapy. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2021;6(1):1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00653-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey W.T., Carabelli A.M., Jackson B., Gupta R.K., Thomson E.C., Harrison E.M., Ludden C., Reeve R., Rambaut A., Peacock S.J. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19(7):409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butowt R., Bilinska K., Von Bartheld C.S. Chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19: integration of genetic and epidemiological data points to D614G spike protein variant as a contributing factor. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eaaswarkhanth M., Al Madhoun A., Al-Mulla F. Could the D614G substitution in the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein be associated with higher COVID-19 mortality? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;96:459–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosseninasab A., Shafiei Bafti M., Ebrahimi S., Anjomshoaa A., Sadeghi Zerandi F., Jafari M., Eslami S., Khalooei A. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children with acute respiratory infection: a study from Southeastern Iran. Shiraz E-Medical Journal. 2020;21(12) doi: 10.5812/semj.108377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia X. Domains and functions of spike protein in sars-cov-2 in the context of vaccine design. Viruses. 2021;13(1):109. doi: 10.3390/v13010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauf M.A., Tasleem M., Bhise K., Tatiparti K., Sau S., Iyer A.K. Nano‐therapeutic strategies to target coronavirus. View. 2021 doi: 10.1002/VIW.20200155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pokhrel S., Kraemer B.R., Lee L., Samardzic K., Mochly-Rosen D. Increased elastase sensitivity and decreased intramolecular interactions in the more transmissible 501Y. V1 and 501Y. V2 SARS-CoV-2 variants' spike protein-an in silico analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhanu P., Kumar N.H., Kumar S.H., Relekar M., Anand D.A., Kumar J. Comparative molecular docking analysis of the SARS CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein with the human ACE-2 receptors and thrombin. Bioinformation. 2020;16(7):532–537. doi: 10.6026/97320630016532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali A., Vijayan R. Dynamics of the ACE2-SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV spike protein interface reveal unique mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71188-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zandi M., Hosseini F., Adli A.H., Salmanzadeh S., Behboudi E., Halvaei P., Khosravi A., Abbasi S. State-of-the-art cerium nanoparticles as promising agents against human viral infections. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022;156 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao X., Chen H., Wang H. Glycans of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in virus infection and antibody production. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021;8:53. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.629873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y., Qiao B., Olvera de la Cruz M. Protein surface printer for exploring protein domains. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.26.222265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casalino L., Gaieb Z., Goldsmith J.A., Hjorth C.K., Dommer A.C., Harbison A.M., Fogarty C.A., Barros E.P., Taylor B.C., McLellan J.S., Fadda E., Amaro R.E. Beyond shielding: the roles of glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.11.146522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali F., Elserafy M., Alkordi M.H., Amin M. ACE2 coding variants in different populations and their potential impact on SARS-CoV-2 binding affinity. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2020;24 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2020.100798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benetti E., Tita R., Spiga O., Ciolfi A., Birolo G., Bruselles A., Doddato G., Giliberti A., Marconi C., Musacchia F., Pippucci T., Torella A., Trezza A., Valentino F., Baldassarri M., Brusco A., Asselta R., Bruttini M., Furini S., Seri M., Nigro V., Matullo G., Tartaglia M., Mari F., Renieri A., Pinto A.M. ACE2 gene variants may underlie interindividual variability and susceptibility to COVID-19 in the Italian population. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.: EJHG (Eur. J. Hum. Genet.) 2020;28(11):1602–1614. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC . 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions, CDC. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L., Xie S., Li C., Su L., Zhu C. Effect of nasal irrigation in adults infected with Omicron variant of COVID-19: a quasi-experimental study. Front. Public Health. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1046112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosseinzadeh P., Zareipour M., Baljani E., Moradali M.R. Social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. A systematic review. Invest. Educ. Enfermería. 2022;40(1) doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v40n1e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jawad B., Adhikari P., Podgornik R., Ching W.-Y. 2021. Key Interacting Residues between RBD of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 Receptor: Combination of Molecular Dynamic Simulation and Density Functional Calculation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li R.-T., Qin C.-F. Expression pattern and function of SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2. Biosafety and Health. 2021;3(6):312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bsheal.2021.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manolis A.S., Manolis T.A., Manolis A.A., Melita H. The controversy of renin-angiotensin-system blocker facilitation versus countering COVID-19 infection. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020;76(4):397–406. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Oliveira M., De Sibio M.T., Mathias L.S., Rodrigues B.M., Sakalem M.E., Nogueira C.R. Irisin modulates genes associated with severe coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outcome in human subcutaneous adipocytes cell culture. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020;515 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L., Lely A.T., Navis G., van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hikmet F., Méar L., Edvinsson Å., Micke P., Uhlén M., Lindskog C. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2020;16(7) doi: 10.15252/msb.20209610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma S., Sun S.H., Li J.M., Fan Y.L., Qu J., Sun L., Wang S., Zhang Y.Y., Yang S.S., Liu Z.P., Wu Z.M., Zhang S., Wang Q.R., Zheng A.H., Duo S.G., Yu Y., Belmonte J.C.I., Chan P., Zhou Q., Song M., Zhang W.Q., Liu G.H. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of primate cardiopulmonary aging. Cell Res. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Devaux C.A., Rolain J.-M., Raoult D. ACE2 receptor polymorphism: susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, hypertension, multi-organ failure, and COVID-19 disease outcome. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou Y., Zhao J., Martin W., Kallianpur A., Chung M.K., Jehi L., Sharifi N., Erzurum S., Eng C., Cheng F. New insights into genetic susceptibility of COVID-19: an ACE2 and TMPRSS2 polymorphism analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):216. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01673-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stawiski E.W., Diwanji D., Suryamohan K., Gupta R., Fellouse F.A., Sathirapongsasuti F., Liu J., Jiang Y.-P., Ratan A., Mis M. Human ACE2 receptor polymorphisms predict SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.07.024752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohammad A., Marafie S.K., Alshawaf E., Abu-Farha M., Abubaker J., Al-Mulla F. Structural analysis of ACE2 variant N720D demonstrates a higher binding affinity to TMPRSS2. Life Sci. 2020;259 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng Y.-R., Li X., Zhao X., Lin H. Cell entry of animal coronaviruses. Viruses. 2021;13(10):1977. doi: 10.3390/v13101977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ponga M. Quantifying the adhesive strength between the SARS-CoV-2 S-proteins and human receptor and its effect in therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74189-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barton M.I., MacGowan S., Kutuzov M.A., Dushek O., Barton G.J., van der Merwe P.A. Effects of common mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD domain and its ligand the human ACE2 receptor on binding affinity and kinetics. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.05.18.444646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Armijos-Jaramillo V., Yeager J., Muslin C., Perez-Castillo Y. SARS-CoV-2, an evolutionary perspective of interaction with human ACE2 reveals undiscovered amino acids necessary for complex stability. Evol Appl. 2020;13(9):2168–2178. doi: 10.1111/eva.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gheblawi M., Wang K., Viveiros A., Nguyen Q., Zhong J.C., Turner A.J., Raizada M.K., Grant M.B., Oudit G.Y. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system: celebrating the 20th anniversary of the discovery of ACE2. Circ. Res. 2020;126(10):1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng L., Shen L., Xu J., Tian X., Liu F., Wang J., Tian G., Yang J., Zhou L. Prioritizing antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 by integrating viral complete genome sequences and drug chemical structures. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83737-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edwards M.J., Becker K.A., Gripp B., Hoffmann M., Keitsch S., Wilker B., Soddemann M., Gulbins A., Carpinteiro E., Patel S.H., Wilson G.C., Pöhlmann S., Walter S., Fassbender K., Ahmad S.A., Carpinteiro A., Gulbins E. Sphingosine prevents binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike to its cellular receptor ACE2. J. Biol. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu C.Y., Lin Y.S., Yang Y.H., Shu L.H., Cheng Y.C., Liu H.T. GB-2 inhibits ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression: in vivo and in vitro studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;132 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu C.-Y., Yang Y.-H., Lin Y.-S., Shu L.-H., Cheng Y.-C., Liu H.-T., Lin Y.-Y., Lee I.-Y., Shih W.-T., Yang P.-R. The anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect and mechanism of Chiehyuan herbal oral protection solution. Heliyon. 2023;9(7) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ur Rehman S., Tabish M. Alternative splicing of ACE2 possibly generates variants that may limit the entry of SARS-CoV-2: a potential therapeutic approach using SSOs. Clin. Sci. 2020;134(10):1143–1150. doi: 10.1042/CS20200419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Faraji S.N., Raee M.J., Hashemi S.M.A., Daryabor G., Tabrizi R., Dashti F.S., Behboudi E., Heidarnejad K., Nowrouzi-Sohrabi P., Hatam G. Human interaction targets of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: a systematic review. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2022;20 doi: 10.1177/1721727X221095382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gu Y., Cao J., Zhang X., Gao H., Wang Y., Wang J., Zhang J., Shen G., Jiang X., Yang J. Interaction network of SARS-CoV-2 with host receptome through spike protein. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.09.09.287508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang S., Qiu Z., Hou Y., Deng X., Xu W., Zheng T., Wu P., Xie S., Bian W., Zhang C. AXL is a candidate receptor for SARS-CoV-2 that promotes infection of pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Res. 2021;31(2):126–140. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00460-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart C.A., Gay C.M., Ramkumar K., Cargill K.R., Cardnell R.J., Nilsson M.B., Heeke S., Park E.M., Kundu S.T., Diao L. Lung cancer models reveal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to coronavirus disease 2019 pathophysiology. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rizzi M., Tonello S., D'Onghia D., Sainaghi P.P. Gas6/TAM axis involvement in modulating inflammation and fibrosis in COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(2):951. doi: 10.3390/ijms24020951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim C.-H. SARS-CoV-2 evolutionary adaptation toward host entry and recognition of receptor O-Acetyl sialylation in virus-host interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(12):4549. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Asai A., Konno M., Ozaki M., Otsuka C., Vecchione A., Arai T., Kitagawa T., Ofusa K., Yabumoto M., Hirotsu T. COVID-19 drug discovery using intensive approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(8):2839. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qi F.R., Qian S., Zhang S.Y., Zhang Z. Single cell RNA sequencing of 13 human tissues identify cell types and receptors of human coronaviruses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;526(1):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cao Z., Wang L.T., Liu Z.M. [Homologous modeling and binding ability analysis of Spike protein after point mutation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 to receptor proteins and potential antiviral drugs] Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;53(1):150–158. doi: 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2021.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Makowski L., Olson-Sidford W., W-Weisel J. Biological and clinical consequences of integrin binding via a rogue RGD motif in the SARS CoV-2 spike protein. Viruses. 2021;13(2):146. doi: 10.3390/v13020146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ragotte R.J., Pulido D., Donnellan F.R., Gorini G., Davies H., Brun J., King L.D., Skinner K., Draper S.J. Human basigin (CD147) does not directly interact with SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.22.432402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bartolomé A., Liang J., Wang P., Ho D.D., Pajvani U.B. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 is a novel target of the γ-secretase complex. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89379-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bestle D., Heindl M.R., Limburg H., Van T.V.L., Pilgram O., Moulton H., Stein D.A., Hardes K., Eickmann M., Dolnik O., Rohde C., Klenk H.D., Garten W., Steinmetzer T., Bottcher-Friebertshauser E. TMPRSS2 and furin are both essential for proteolytic activation of SARS-CoV-2 in human airway cells. Life Sci. Alliance. 2020;3(9) doi: 10.26508/lsa.202000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Charostad J., Mokhtari-Azad T., Yavarian J., Ghavami N., Khorrami S.M., Behboudi E., Jalilvand S., Malekshahi S.S., Shafiei-Jandaghi N.Z. Detection of human herpes viruses 1-5 in miscarriage: a case-control study. Int J Reprod BioMed. 2020;(7):501. doi: 10.18502/ijrm.v13i7.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hamidi-Sofiani V., Rakhshi R., Moradi N., Zeynali P., Nakhaie M., Behboudi E. Oncolytic viruses and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;31 doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2022.100563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Voinsky I., Gurwitz D. Smoking and COVID-19: similar bronchial ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression and higher TMPRSS4 expression in current versus never smokers. Drug Dev. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ddr.21729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zang R.C., Castro M.F.G., McCune B.T., Zeng Q.R., Rothlauf P.W., Sonnek N.M., Liu Z.M., Brulois K.F., Wang X., Greenberg H.B., Diamond M.S., Ciorba M.A., Whelan S.P.J., Ding S.Y. TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 promote SARS-CoV-2 infection of human small intestinal enterocytes. Sci Immunol. 2020;5(47) doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cosic I., Cosic D., Loncarevic I. RRM prediction of erythrocyte Band3 protein as alternative receptor for SARS-CoV-2 virus. Appl. Sci. 2020;10(11):4053. doi: 10.3390/app10114053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Senapati S., Kumar S., Singh A.K., Banerjee P., Bhagavatula S. Assessment of risk conferred by coding and regulatory variations of TMPRSS2 and CD26 in susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection in human. J. Genet. 2020;99(1) doi: 10.1007/s12041-020-01217-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torre-Fuentes L., Matías-Guiu J., Hernández-Lorenzo L., Montero-Escribano P., Pytel V., Porta-Etessam J., Gómez-Pinedo U., Matías-Guiu J.A. ACE2, TMPRSS2, and Furin variants and SARS-CoV-2 infection in Madrid, Spain. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93(2):863–869. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoffmann M., Hofmann-Winkler H., Smith J.C., Krüger N., Arora P., Sørensen L.K., Søgaard O.S., Hasselstrøm J.B., Winkler M., Hempel T. Camostat mesylate inhibits SARS-CoV-2 activation by TMPRSS2-related proteases and its metabolite GBPA exerts antiviral activity. EBioMedicine. 2021;65 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Edwards M.J., Becker K.A., Gripp B., Hoffmann M., Keitsch S., Wilker B., Soddemann M., Gulbins A., Carpinteiro E., Patel S.H. Sphingosine prevents binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike to its cellular receptor ACE2. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295(45):15174–15182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu C.-Y., Lin Y.-S., Yang Y.-H., Shu L.-H., Cheng Y.-C., Te Liu H. GB-2 inhibits ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression: in vivo and in vitro studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;132 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson A.J., Troy-Barnes E., Subhan M., Clark F., Gupta R., Fielding A.K., Kottaridis P., Mansour M.R., O'Nions J., Payne E. Successful remission induction therapy with gilteritinib in a patient with de novo FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukaemia and severe COVID-19. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190(4):e189–e191. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pillaiyar T., Laufer S. Kinases as potential therapeutic targets for anti-coronaviral therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2021;65(2):955–982. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Toshiyama R., Konno M., Eguchi H., Takemoto H., Noda T., Asai A., Koseki J., Haraguchi N., Ueda Y., Matsushita K. Poly (ethylene glycol)-poly (lysine) block copolymer-ubenimex conjugate targets aminopeptidase N and exerts an antitumor effect in hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Oncogene. 2019;38(2):244–260. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beddingfield B.J., Iwanaga N., Chapagain P.P., Zheng W., Roy C.J., Hu T.Y., Kolls J.K., Bix G.J. The integrin binding peptide, ATN-161, as a novel therapy for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Basic Transl Sci. 2021;6(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li K., Meyerholz D.K., Bartlett J.A., McCray P.B., Jr. The TMPRSS2 inhibitor nafamostat reduces SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary infection in mouse models of COVID-19. mBio. 2021;12(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00970-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cheng Y.-W., Chao T.-L., Li C.-L., Chiu M.-F., Kao H.-C., Wang S.-H., Pang Y.-H., Lin C.-H., Tsai Y.-M., Lee W.-H. Furin inhibitors block SARS-CoV-2 spike protein cleavage to suppress virus production and cytopathic effects. Cell Rep. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu C., Zheng M., Yang Y., Gu X., Yang K., Li M., Liu Y., Zhang Q., Zhang P., Wang Y. Furin: a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19. iScience. 2020;23(10) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vélez E.J., Capilla E., Lutfi E. Inter-organ communication beyond mammals: the role of tissue-specific cytokines. Front. Endocrinol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1208000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu T., Luo S., Libby P., Shi G.-P. Cathepsin L-selective inhibitors: a potentially promising treatment for COVID-19 patients. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;213 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blaess M., Kaiser L., Sauer M., Csuk R., Deigner H.-P. COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 infection: lysosomes and lysosomotropism implicate new treatment strategies and personal risks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(14):4953. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Firouzabadi D., Kheshti F., Abdollahifard S., Taherifard E., Kheshti M.R. The effect of selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors on clinical outcome of COVID‐19 patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Health sci rep. 2022;5(6) doi: 10.1002/hsr2.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mellott D.M., Tseng C.-T., Drelich A., Fajtova P., Chenna B.C., Kostomiris D.H., Hsu J., Zhu J., Taylor Z.W., Tat V. A cysteine protease inhibitor blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection of human and monkey cells. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.23.347534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seidah N.G., Pasquato A., Andreo U. How Do Enveloped Viruses Exploit the Secretory Proprotein Convertases to Regulate Infectivity and Spread? 2021;13(7):1229. doi: 10.20944/preprints202104.0469.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peacock T.P., Goldhill D.H., Zhou J., Baillon L., Frise R., Swann O.C., Kugathasan R., Penn R., Brown J.C., Sanchez-David R.Y. The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat Microbiol. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00908-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Segreto R., Deigin Y., McCairn K., Sousa A., Sirotkin D., Sirotkin K., Couey J.J., Jones A., Zhang D. Springer; 2021. Should We Discount the Laboratory Origin of COVID-19? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johnson B.A., Xie X., Bailey A.L., Kalveram B., Lokugamage K.G., Muruato A., Zou J., Zhang X., Juelich T., Smith J.K., Zhang L., Bopp N., Schindewolf C., Vu M., Vanderheiden A., Winkler E.S., Swetnam D., Plante J.A., Aguilar P., Plante K.S., Popov V., Lee B., Weaver S.C., Suthar M.S., Routh A.L., Ren P., Ku Z., An Z., Debbink K., Diamond M.S., Shi P.-Y., Freiberg A.N., Menachery V.D. Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature. 2021;591(7849):293–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03237-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Papa G., Mallery D.L., Albecka A., Welch L.G., Cattin-Ortolá J., Luptak J., Paul D., McMahon H.T., Goodfellow I.G., Carter A., Munro S., James L.C. Furin cleavage of SARS-CoV-2 Spike promotes but is not essential for infection and cell-cell fusion. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Follis K.E., York J., Nunberg J.H. Furin cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein enhances cell-cell fusion but does not affect virion entry. Virology. 2006;350(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Johnson B.A., Xie X., Bailey A.L., Kalveram B., Lokugamage K.G., Muruato A., Zou J., Zhang X., Juelich T., Smith J.K. Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature. 2021;591(7849):293–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03237-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cheng Y.-W., Chao T.-L., Li C.-L., Chiu M.-F., Kao H.-C., Wang S.-H., Pang Y.-H., Lin C.-H., Tsai Y.-M., Lee W.-H., Tao M.-H., Ho T.-C., Wu P.-Y., Jang L.-T., Chen P.-J., Chang S.-Y., Yeh S.-H. Furin inhibitors block SARS-CoV-2 spike protein cleavage to suppress virus production and cytopathic effects. Cell Rep. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tang L., Schulkins A., Chen C.-N., Deshayes K., Kenney J.S. 2020. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein D614G Mutation Shows Increasing Dominance and May Confer a Structural Advantage to the Furin Cleavage Domain. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wu C., Zheng M., Yang Y., Gu X., Yang K., Li M., Liu Y., Zhang Q., Zhang P., Wang Y., Wang Q., Xu Y., Zhou Y., Zhang Y., Chen L., Li H. Furin: a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19. iScience. 2020;23(10) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ragia G., Manolopoulos V.G. 2020. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Entry through the ACE2/TMPRSS2 Pathway: a Promising Approach for Uncovering Early COVID-19 Drug Therapies; pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zandi M., Behboudi E., Soltani S. Role of glycoprotein hemagglutinin-esterase in COVID-19 pathophysiology? Stem Cell Rev. 2021;17(6):2359–2360. doi: 10.1007/s12015-021-10210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tiscia G.L., Favuzzi G., De Laurenzo A., Cappucci F., Fischetti L., di Mauro L., Miscio G., Mirijello A., Chinni E., Grandone E. Reduction of ADAMTS13 levels predicts mortality in SARS-CoV-2 patients. TH Open. 2020;4(3):e203–e206. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Morici N., Bottiroli M., Fumagalli R., Marini C., Cattaneo M. Role of von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS-13 in the pathogenesis of thrombi in SARS-CoV-2 infection: time to rethink. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020;120(9):1339–1342. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murgolo N., Therien A.G., Howell B., Klein D., Koeplinger K., Lieberman L.A., Adam G.C., Flynn J., McKenna P., Swaminathan G. SARS-CoV-2 tropism, entry, replication, and propagation: considerations for drug discovery and development. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Huang I.C., Bosch B.J., Li F., Li W., Lee K.H., Ghiran S., Vasilieva N., Dermody T.S., Harrison S.C., Dormitzer P.R., Farzan M., Rottier P.J., Choe H. SARS coronavirus, but not human coronavirus NL63, utilizes cathepsin L to infect ACE2-expressing cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(6):3198–3203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508381200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Simmons G., Gosalia D.N., Rennekamp A.J., Reeves J.D., Diamond S.L., Bates P. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(33):11876–11881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505577102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhao M.-M., Yang W.-L., Yang F.-Y., Zhang L., Huang W.-J., Hou W., Fan C.-F., Jin R.-H., Feng Y.-M., Wang Y.-C., Yang J.-K. Cathepsin L plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans and humanized mice and is a promising target for new drug development. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2021;6(1):134. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liu T., Luo S., Libby P., Shi G.P. Cathepsin L-selective inhibitors: a potentially promising treatment for COVID-19 patients. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;213 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oliver J.C., Silva E.N., Soares L.M., Scodeler G.C., Santos A.d.S., Corsetti P.P., Prudêncio C.R., de Almeida L.A. Different drug approaches to COVID-19 treatment worldwide: an update of new drugs and drugs repositioning to fight against the novel coronavirus. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother. 2022;10 doi: 10.1177/25151355221144845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Boytz R., Słabicki M., Ramaswamy S., Patten J., Zou C., Meng C., Hurst B.L., Wang J., Nowak R.P., Yang P.L. Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 activity of targeted kinase inhibitors: repurposing clinically available drugs for COVID‐19 therapy. J. Med. Virol. 2023;95(1) doi: 10.1002/jmv.28157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dirim A.B., Demir E., Ucar A.R., Garayeva N., Safak S., Oto O.A., Yazici H., Alibeyoglu A.M., Orhun G., Cagatay A.A., Turkmen A. Fatal SARS-CoV-2 infection in a renal transplant recipient. CEN case reports. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s13730-020-00496-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Valyaeva A.A., Zharikova A.A., Sheval E.V. SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism and direct multiorgan failure in COVID‐19 patients: bioinformatic predictions, experimental observations, and open questions. Cell Biol. Int. 2023;47(2):308–326. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Li M.-Y., Li L., Zhang Y., Wang X.-S. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis poverty. 2020;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eslami N., Aghbash P.S., Shamekh A., Entezari-Maleki T., Nahand J.S., Sales A.J., Baghi H.B. SARS-CoV-2: receptor and co-receptor Tropism Probability. Curr. Microbiol. 2022;79(5):133. doi: 10.1007/s00284-022-02807-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]