Abstract

Introduction

Patient-centered communication is a type of communication that takes place between the provider and the patient.

Objectives

It is aimed to reveal the effects of patient-centered communication on patient engagement, health-related quality of life, perception of service quality and patient satisfaction.

Method

The study was conducted by applying multiple regression analysis to the data obtained from 312 patients with cancer treated in a training and research hospital affiliated to the Ministry of Health in Diyarbakır, Türkiye.

Results

More than half of the patients were female and had stage 4 cancer. Different types of cancer were detected (breast cancer, cancer of the digestive organs, lymphatic and hematopoietic cancer, cancer of the genital organs, cancer of the respiratory organs, etc.). It can be stated that the average values obtained by patients from patient-centered communication and its sub-dimensions are high. There are positive, moderate and low and significant relationships between the overall patient-centered communication and patient engagement, patient satisfaction, service quality perception and quality of life. It was statistically revealed that patient-centered communication positively affected patient engagement, health-related quality of life, service quality perception, and patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

Patient-centered communication positively affects various short and medium-term health outcomes and this study offers suggestions for improving patient-provider communication.

Keywords: patient-centered communication, cancer disease, patient engagement, health related quality of life, service quality perception, patient satisfaction

Introduction

With the continuous development in cancer treatment, knowledge about the etiology of cancer has increased and new treatment methods and models for cancer treatment have been developed. At the center of all these changes, however, are the cancer patients and their caregivers. Understanding the dynamic relationship between patients and care providers, particularly the communication relationship and developing ways to optimize this relationship has been the focus of numerous studies. 1 The starting point for this study is the 2001 report by the American Institute of Medicine (IOM) entitled “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century”. The report identifies 6 goals to be improved in the redesign of the health system and states that medical care should be patient-centered. The 6 goals targeted by the IOM report are to ensure safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient and equitable health care, and that improvements should be made in these areas. In addition, the report identified the need for fundamental reform to ensure that all Americans receive safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable health care services. 2

When one examines the literature, one finds that great importance is placed on “patient-centeredness,” one of these components. The IOM has stated that patient-centered care should be defined as “care that respects and responds to patients’ preferences, needs, and values and ensures that patients’ values guide all clinical decisions". 3 Patient-centered care is based on strong communication between patients and health care providers that requires a two-way exchange of information and supports patients’ active involvement in their care to the extent they desire. 4 It is also said that patient-centered communication (PCC) is the foundation of patient-centered care and that patient-centered communication is considered the primary mechanism for the delivery of patient-centered care.1,5

If we look at the stages of development of the concept of patient-centered communication, we see that in the book published by Carl Rogers in 1951, “client-centered treatment” was expressed by nursing researchers as “patient-centered treatment”, in 1962 as “patient-centered medicine” and in the 1970s as “patient-centered medicine”. Then, in recent years, the concept of “patient-centered communication” was used as a communication strategy and patient-centered communication and communication behaviors evolved. 6 Subsequently, health communication research on physician-patient interactions has promoted patient-centered communication as the ideal medical conversation style. 7 Patient-centered communication has gained acceptance because it facilitates the transition from a paternalistic relationship to a reciprocal communication relationship in a way that the traditional medical approach incorporates the patient’s perspective and promotes the physician-patient partnership. 8

Patient-centered communication requires physicians and other health care providers to have the communication skills to elicit patients’ true wishes and to recognize and respond to both their needs and emotional concerns. Patient-centered communication is seen as an important element in meeting the needs of patients and their families and a fundamental requirement for high-quality cancer care. 9 Patient-centered communication focuses on goals that should be achieved jointly by physicians, patients and, when appropriate, families. Some features of patient-centered communication are stated as follows 10 :

• Reveals the patient’s perspective (beliefs, preferences, concerns, needs).

• Explores the bio-psycho-social context of the patient’s health and well-being.

• Builds or strengthens trust and mutual respect in the physician-patient relationship.

• Present disease and treatment options in a way that the patient understands.

• Supports patients’ active participation in the communication and decision-making process.

• It is based on common sense in problem solving and action plans.

• Allows for decisions that are evidence-based, consistent with the patient’s values and feasible to implement.

Patient-centered communication is an important part of patient-centered cancer care and contributes directly and indirectly to patient understanding, satisfaction, motivation, trust, health and well-being.11,12 Studies show that there are various determinants of patient-centered communication and that patient-centered communication is associated with many factors such as patient engagement, health-related quality of life, service quality perception, and patient satisfaction.12-33 Research on the relationship between patient-service provider communication and patient outcomes has generally focused on patient satisfaction and adherence to medical treatment, health habits and self-care.4,34 Studies show that patient-centered communication improves patient satisfaction, quality of care, and health outcomes while reducing health care costs and disparities. 4 Patient-centered communication has been associated with greater patient participation in health promotion activities, adherence to treatment recommendations, improvement in health status, better quality of life, patient satisfaction and perceptions of service quality.4,11,12,35,36

When examining the studies on communication in cancer patients, it becomes apparent that there is a limited amount of research specifically focused on patient-centered communication in this population. The challenges of recruiting participants for studies involving cancer patients, as well as the emotional impact of these studies on patients due to their illness, can disrupt the research process. Additionally, measuring communication effectiveness, quality of life, levels of participation, and patient satisfaction can also pose difficulties in studying cancer patients. The purpose of this study is to fill the gap in this field, as there are few studies on patient-centered communication in patients with cancer, and to reveal the effects of patient-centered communication on short and medium term health outcomes. In addition, this study aims to reveal the effects of patient-centered communication on patient engagement, health-related quality of life, service quality and patient satisfaction in patients with cancer.

Research has attempted to answer various questions. These are;

1) Does patient-centered communication influence patient engagement in patients with cancer?

2) Does patient-centered communication in patients with cancer have an impact on the health related quality of life of patients with cancer?

3) Does effective patient-centered communication with cancer patients increase patient satisfaction?

4) Does patient-centered communication have a positive impact on patients’ perception of service quality?

Methods

Research Model and Hypothesis

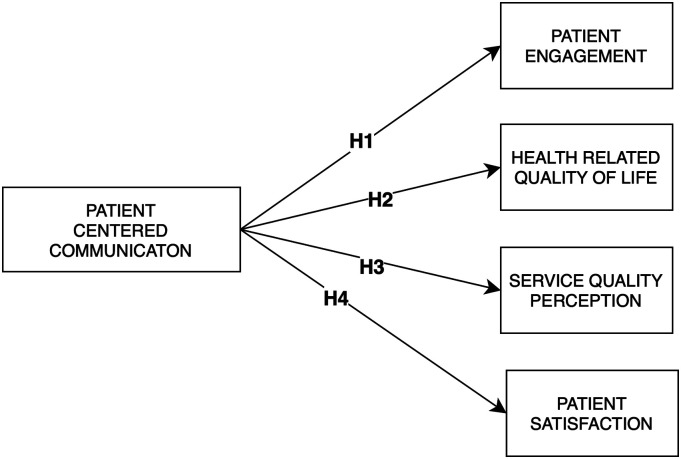

The research hypotheses developed in line with the research objectives are listed below and the model of the research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

H 1 : Patients with cancer’ evaluations of the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication level affect their level of patient engagement.

H 2 : Patients with cancer’ evaluations of patient-centered communication level sub-dimensions affect their health-related quality of life.

H 3 : Patients with cancer’ evaluations of patient-centered communication level sub-dimensions affect the level of service quality perceptions.

H 4 : Patients with cancer’ evaluations of patient-centered communication level sub-dimensions affect patient satisfaction levels.

Study Design and Participants

This observational cross-sectional study is being reported in conformation with STROBE guidelines. 37 The population of this study, consisted of patients with cancer who received outpatient and inpatient treatment at Diyarbakır Training and Research Hospital in Turkey between August 1, 2021 and April 30, 2022. The study sample included all patients with cancer who received outpatient and inpatient treatment at the hospital, were at least 18 years old, had been receiving cancer treatment for at least 2 months, were physically and cognitively fit to answer the questionnaire, and regardless of diagnosis. In line with these limitations, 312 responses were received from 350 patients within the scope of the study. The study did not calculate the sample size and attempted to reach all patients who met the inclusion criteria. The return rate of the questionnaires was 89%. Interviews with the staff responsible for cancer treatment revealed that 350 patients were treated during the survey period. Of the 350 patients, 38 patients did not participate in the surveys. These patients did not participate in the study because some of them were palliative care patients, some of them did not want to voluntarily participate in the study and some of them did not have the physical and cognitive health status to answer the questionnaire.

Data Collection Tools

Detailed information on the scales used in the study is provided below.

Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care (PCC-Ca-36)

RTI International and the University of North Carolina have developed a comprehensive, publicly available measurement tool. The Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care (PCC-Ca) scale is available in both a long (36 items) and short (6 items) form and is very easy to score. The aim of this scale is to assess PCC in the following 6 key dimensions: (1) information sharing, (2) relationships with doctors and other health professionals, (3) decision making, (4) caring for emotions, (5) self-care, and (6) managing uncertainty. 38 The PCC-Ca-36 is a 5-point Likert scale. Scores can be calculated both on the basis of sub-dimensions and the overall scale.

Patient Engagement

The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) regularly collects national-level data on the American public’s knowledge, attitudes and use of information about cancer and health. 39 The questionnaires created by the National Cancer Institute measure many different issues. One of these questionnaires is the survey questions created to measure the engagement of patients. The Patient Engagement Scale developed by HINTS consists of 6 questions and is in 4-point Likert style (1 = Never, 4 = Always). High scores indicate a high level of patient engagement.

Health Related Quality of Life (EQ-5D-3L)

The 3-level version of the Health Related Quality of Life Scale (EQ-5D-3L) was developed by the EuroQol Group in 1990 and introduced to the literature. In this study, the form adapted into Turkish by the EuroQol Group was used. The EQ-5D-3L mainly consists of 2 pages, the EQ-5D descriptive system and the EQ visual analog scale (EQ VAS). The EQ-5D-3L consists of mobility, self-care, usual tasks, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/moral disturbance subscales. The scale consists of 5 dimensions and has 3 levels. These are; no problems, some problems and extreme problems. The patient is asked to indicate the most appropriate statement for each of the 5 dimensions. This decision results in a 1-digit number representing the level chosen for that dimension. The numbers of the 5 dimensions can be combined into a 5-digit number describing the patient’s health status. 40 This 5-digit number is then transferred to the EQ-5D index calculator program developed by the EuroQol Group to obtain a quality of life value between zero and 1 for each patient.

Perception of Service Quality

The perception of service quality was measured with a single question (“How would you rate the quality of health care services you received for your illness after you were diagnosed with cancer”). The question to measure the perception of service quality was a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Inadequate, 2 = Good, 3 = Very good, 4 = Excellent). High scores obtained from this question used by various researchers indicate that the perception of service quality is high.41-43

The Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS)

The Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS) is a brief and reliable scale that can be used to assess patients’ satisfaction with their treatment. The SAPS assesses key areas of patient satisfaction, including satisfaction with treatment, explanation of treatment outcomes, physician care, participation in medical decision-making, physician respect, time spent with the physician, and satisfaction with hospital/clinic care. The SAPS has been validated in clinical settings with support from the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The scale consists of 7 questions. The questions are on a 5-point Likert scale scored from zero to 4 (0 = Not at all satisfied-5 = Very satisfied). Although it is a short measurement tool, it is easy to use and score. Questions 1, 3, 5 and 7 are reverse scored. 44 As the scores obtained from the scale increase, the satisfaction levels of the patients increase.

Ethical Considerations

To conduct the study, the necessary permissions were obtained from Hacettepe University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee on 16.05.2021 with 2021/06-70 decision number in Ankara and from Ministry of Health, Diyarbakır Provincial Health Directorate on 25.06.2021 with 97893136 number. The questionnaires were completed by the researcher face-to-face with the patients in their rooms or in the units where outpatient chemotherapy treatments were performed. Patients were asked to complete and sign a written consent form before the study. The data was collected in a way that does not reveal the identity of the patient. No financial support was received from any institution for this study, and no financial payment was made to the patients participating in the study, and all patients voluntarily participated in the study.

Data Analysis

All data obtained within the scope of the research were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 22.0 package program. 45 First of all, the validity and reliability analyses of the Patient-Centered Communication, Patient Engagement and The Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction were conducted within the scope of the study. Validity and reliability analyses were not performed due to the use of a single question to measure Perception of Service Quality and the fact that the Turkish adaptation of the Health-Related Quality of Life Scale was made and used in many studies.46-48 Since the scales for which validity and reliability analyses were conducted were developed in English, language validity studies were conducted first. Then, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the construct validity of the scales and Cronbach Alpha coefficient was used for reliability analysis. CFA results for the patient-centered communication (X2/sd: 3.246; RMESA: .085; GFI: .800; CFI: .906; NFI: .871; TLI: .896), CFA results for the patient engagement (X2/sd: 3.225; RMESA: .086; GFI: 0. 983; CFI:0.995; NFI:0.993; TLI:0.985), CFA results for SAPS (X2/sd: 2.105; RMESA: .060; GFI:0.975; CFI:0.989; NFI:0.980; TLI:0.983) show that the scales have good fit indices. In addition, Cronbach Alpha value for patient-centered communication was found to be .974, .962 for patient engagement and .893 for patient satisfaction.

Within the scope of the research, descriptive statistics were obtained and multivariate regression analyses were conducted. Durbin Watson Coefficient and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) were calculated to determine whether there is multicollinearity and autocorrelation in linear regression models. Alpha level was taken as .05 in all statistical tests.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 shows the results with regard to the sociodemographic variables of the patients. More than half of the patients were female (60.9%), 91% of the patients were married, 26.6% were 43 years old or younger, 26.6% were between 55-64 years old, 25.6% were between 44-54 years old, and 21.2% were 65 years old or older. It was found that half of the patients (50%) lived in the city center and the other half (50%) lived in rural areas. According to the results, 30.8% of patients had breast cancer, 21.2% had cancer of the digestive organs, 15.1% had cancer of the lymphatic and hematopoietic cancer, 13.1% had cancer of the genital organs, 12.2% had cancer of the respiratory organs and 7.7% had other cancers. 57.4% of the patients were patients with stage 4 cancer. 90.4% of the patients received chemotherapy and the rest other treatments (radiotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy together, treatment with bone drugs, etc.). Table 1 presents other descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Patient Characteristics | n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | 190 | 60.9 |

| Male | 122 | 39.1 | |

| Age | 43 years and below | 83 | 26.6 |

| 44-54 years | 80 | 25.6 | |

| 55-64 years | 83 | 26.6 | |

| 65 years and older | 66 | 21.2 | |

| Marital status | Single | 28 | 9.0 |

| Married | 284 | 91.0 | |

| Residence | Countryside | 156 | 50.0 |

| City | 156 | 50.0 | |

| Cancer type a | Breast | 96 | 30.8 |

| Lymphoid and Hematopoietic | 47 | 15.1 | |

| Digestive Organs | 66 | 21.2 | |

| Respiratory Organs | 38 | 12.2 | |

| Genital Organs | 41 | 13.1 | |

| Other types of cancer (thyroid, skin, bone, brain, etc.) | 24 | 7.7 | |

| Cancer stage | Stage I | 13 | 4,2 |

| Stage II | 38 | 12,2 | |

| Stage III | 82 | 26.3 | |

| Stage IV | 179 | 57.4 | |

| Treatment type | Chemotherapy | 282 | 90.4 |

| Other types of treatment (radiotherapy, bone drugs, etc.) | 30 | 9.6 | |

| Physical health status | Bad | 77 | 24.7 |

| Moderate | 129 | 41.3 | |

| Good | 106 | 34.0 | |

| Service procurement type | Inpatient | 100 | 32.1 |

| Outpatient | 212 | 67.9 | |

aBased on the cancer classification of the National Cancer Institute of the USA, 49 a classification was made according to the location of the cancer in the body. Cancers are categorized as digestive system (esophagus, stomach, colon, rectum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, etc.), lymphoid and hematopoietic (lymphoma, leukemia and multiple myeloma), breast cancer, respiratory (lung, pleura), genital cancer (uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, testicular cancer, etc.) and other cancers (thyroid, skin, bone, brain, etc.).

Table 2 shows the correlation relationship between the variables used in the study.

Table 2.

Mean, Standard Deviation and Correlation Coefficients of the Variables Used in the Study.

| Mean. | SD. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Information exchange | 4.58 | .57 | 1 | .740** | .534** | .453** | .566** | .523** | .744** | .555** | .505** | .294** | .136* |

| (2) Relations with doctors and other health care professionals | 4.45 | .52 | .740** | 1 | .703** | .680** | .701** | .726** | .900** | .517** | .647** | .481** | .243** |

| (3) Decision making | 4.43 | .56 | .534** | .703** | 1 | .720** | .652** | .670** | .835** | .360** | .492** | .431** | .178** |

| (4) Giving importance to emotions | 4.24 | .55 | .453** | .680** | .720** | 1 | .746** | .707** | .851** | .302** | .475** | .417** | .205** |

| (5) Self-care | 4.24 | .55 | .566** | .701** | .652** | .746** | 1 | .778** | .878** | .427** | .534** | .418** | .193** |

| (6) Managing uncertainty | 4.34 | .54 | .523** | .726** | .670** | .707** | .778** | 1 | .870** | .424** | .559** | .531** | .220** |

| (7) General patient-centered communication scale | 4.37 | .47 | .744** | .900** | .835** | .851** | .878** | .870** | 1 | .508** | .635** | .509** | .234** |

| (8) Patient engagement scale | 3.64 | .53 | .555** | .517** | .360** | .302** | .427** | .424** | .508** | 1 | .454** | .300** | .102 |

| (9) Patient satisfaction scale | 3.40 | .53 | .505** | .647** | .492** | .475** | .534** | .559** | .635** | .454** | 1 | .656** | .269** |

| (10) Perception of service quality | 2.90 | .76 | .294** | .481** | .431** | .417** | .418** | .531** | .509** | .300** | .656** | 1 | .219** |

| (11) Quality of health-realeted of life score (EQ-5D) | .48 | .30 | .136* | .243** | .178** | .205** | .193** | .220** | .234** | .102 | .269** | .219** | 1 |

**P < .001. *P < .05.

The mean score of patient-centered communication by patients is 4.37. When examining patient-centered communication and its sub-dimensions, the highest mean score is the dimension of information exchange with 4.58. This dimension is followed by relationships with physicians and other health care professionals with a mean score of 4.45 and the importance of emotions with a mean score of 4.43. In general, it can be stated that the mean scores obtained by patients for patient-centered communication and its sub-dimensions are high. The patients’ mean score for patient engagement was 3.64, the mean score for patient satisfaction was 3.40 and the mean score for the question on perception of service quality was 2.90. The patients’ average health-related quality of life was .48. The variable for health-related quality of life has a value between zero and 1. With the exception of the variable for health-related quality of life, the participants’ average scores for all other variables were generally high.

Table 2 shows that there are positive, moderate and low significant relationships between information exchange, relationships with physicians and other health professionals, decision making, giving importance to emotions, self-care, coping with uncertainty, patient-centered communication sub-dimensions, overall patient-centered communication score and patient engagement, patient satisfaction, perception of service quality and health-related quality of life.

There is a positive and moderate correlation between patient engagement and patient satisfaction and perception of service quality, while there is no significant correlation between patient engagement and health-related quality of life. It can be seen that there is a positive, moderate and low significant relationship between patient satisfaction and the perception of service quality and health-related quality of life. There is a positive and moderately significant correlation between the perception of service quality and health-related quality of life.

Regression Analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the multiple linear regression analysis conducted to reveal the effects of the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication on patient engagement. According to the results of the analysis; the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together have a statistically significant and explanatory effect on patient engagement. Statistical estimates of the regression model show that the model is significant and usable (F = 27,400; P < .05). The sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together explain approximately 35% of the total variance in patient engagement.

Table 3.

Regression Analysis Results for Predicting the Effect of Patients’ Evaluations of the Sub-dimensions of Patient-Centered Communication on Patient Engagement.

| Variable | B | Std. Error | β | t | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information exchange | 0.329 | 0.065 | 0.355 | 5041 | <0.001 | 2329 |

| Relations with doctors and other health care professionals | 0.206 | 0.093 | 0.203 | 2200 | 0.029 | 3988 |

| Decision making | −0.016 | 0.070 | −0.017 | −0.228 | 0.820 | 2606 |

| Giving importance to emotions | −0.153 | 0.078 | −0.159 | −1960 | 0.051 | 3090 |

| Self-care | 0.112 | 0.081 | 0.117 | 1383 | 0.168 | 3387 |

| Managing uncertainty | 0.121 | 0.081 | 0.123 | 1490 | 0.137 | 3220 |

R = 0.592; R2 = 0.350; F = 27,400; P < 0.001; Durbin Watson = 1296.

In the regression model, when the t test results regarding the significance of the regression coefficient are examined, it is seen that statistically significant relationships are found in the sub-dimensions of information exchange and relations with doctors and other health care professionals. The increase in patients’ perceptions towards information exchange statistically increases the level of patient engagement (t = 5.041; P < .05). The increase in patients’ perceptions towards doctors and other health care professionals also statistically increases their level of patient engagement (t = 2.200; P < .05). According to the standardized regression coefficient (β), the relative order of importance of the predictor variables on patient engagement is as follows: information exchange, relationships with doctors and other health care professionals. According to the research hypothesis, hypothesis H 1 was accepted for the relevant dimensions.

Table 4 shows the results of the multiple linear regression analysis conducted to reveal the effects of the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication on health-related quality of life. According to the results of the analysis; the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together have a statistically significant explanatory effect on patients’ health-related quality of life and the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication explain approximately 7% of the total variance of health-related quality of life. Statistical estimates of the regression model show that the model is significant and usable (F = 3.705; P < .05).

Table 4.

Regression Analysis Results for Predicting the Effect of Patients’ Evaluations of the Sub-dimensions of Patient-Centered Communication on Health-Related Quality of Life.

| Variable | B | Std. Error | β | t | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information exchange | −0.046 | 0.045 | −0.087 | −1030 | 0.304 | 2329 |

| Relations with doctors and other health care professionals | 0.138 | 0.064 | 0.240 | 2173 | 0.031 | 3988 |

| Decision making | −0.016 | 0.048 | −0.030 | −0.336 | 0.737 | 2606 |

| Giving importance to emotions | 0.028 | 0.053 | 0.050 | 0.516 | 0.606 | 3090 |

| Self-care | −0.004 | 0.055 | −0.007 | −0.072 | 0.943 | 3387 |

| Managing uncertainty | 0.046 | 0.055 | 0.082 | 0.825 | 0.410 | 3220 |

R = 0.261; R2 = 0.068; F = 3705; P < 0.001; Durbin Watson = 1651.

In the regression model, when the t test results regarding the significance of the regression coefficient are examined, it is seen that the only statistically significant relationship is in the sub-dimension of relationships with doctors and other health care professionals. The increase in patients’ perceptions of their relationships with doctors and other health care professionals (t = 2173; P < 0,05) leads to an increase in health-related quality of life levels. According to the research hypothesis, H 2 hypothesis is accepted for the related dimension.

Table 5 presents the results of the multiple linear regression analysis conducted to reveal the effects of the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication on patients’ perceptions of service quality. According to the results of the analysis; the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together have a statistically significant explanatory effect on patients’ perceptions of service quality. Statistical estimates of the regression model show that the model is significant and usable (F = 23,054; P < .05). The sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together explain approximately 31% of the total variance in patients’ perceptions of service quality.

Table 5.

Regression Analysis Results Regarding the Prediction of the Effect of Patients’ Evaluations of the Sub-dimensions of Patient-Centered Communication on the Perception of Service Quality.

| Variable | B | Std. Error | β | t | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information exchange | −0.163 | 0.097 | −0.122 | −1677 | 0.095 | 2329 |

| Relations with doctors and other health care professionals | 0.402 | 0.139 | 0.274 | 2888 | 0.004 | 3988 |

| Decision making | 0.119 | 0.105 | 0.088 | 1143 | 0.254 | 2606 |

| Giving importance to emotions | −0.012 | 0.116 | −0.009 | −0.103 | 0.918 | 3090 |

| Self-care | −0.080 | 0.120 | −0.058 | −0.665 | 0.507 | 3387 |

| Managing uncertainty | 0.549 | 0.121 | 0.388 | 4556 | <0.001 | 3220 |

R = 0.559; R2 = 0.312; F = 23,054; P < 0.001; Durbin Watson = 1900.

In the regression model, when the t test results regarding the significance of the regression coefficient are examined, it is seen that statistically significant relationships are found in the sub-dimensions of relationships with doctors and other health care professionals and coping with uncertainty. The increase in patients’ perceptions of their relationships with doctors and other health care professionals (t = 2.888; P < .05) and coping with uncertainty (t = 4.556; P < .05) statistically increases the level of service quality perception. According to the standardized regression coefficient (β), the relative order of importance of the predictor variables on service quality perception is coping with uncertainty and relationships with doctors and other health care professionals. According to the research hypothesis, hypothesis H 3 is accepted for the relevant dimensions.

Table 6 shows the results of the multiple linear regression analysis conducted to reveal the effects of the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication on patient satisfaction. According to the results of the analysis; the sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together have a statistically significant explanatory effect on patient satisfaction. Statistical estimates of the regression model show that the model is significant and usable (F = 39,973; P < .05). The sub-dimensions of patient-centered communication together explain approximately 44% of the total variance in patient satisfaction.

Table 6.

Regression Analysis Results for Predicting the Effect of Patients’ Evaluations of the Sub-Dimensions of Patient-Centered Communication on Patient Satisfaction.

| Variable | B | Std. Error | β | t | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information exchange | 0.044 | 0.061 | 0.048 | 0.728 | 0.467 | 2329 |

| Relations with doctors and other health care professionals | 0.462 | 0.087 | 0.455 | 5316 | <0.001 | 3988 |

| Decision making | 0.016 | 0.065 | 0.017 | 0.250 | 0.803 | 2606 |

| Giving importance to emotions | −0.044 | 0.073 | −0.045 | −0.599 | 0.549 | 3090 |

| Self-care | 0.087 | 0.075 | 0.091 | 1157 | 0.248 | 3387 |

| Managing uncertainty | 0.151 | 0.075 | 0.154 | 2001 | 0.046 | 3220 |

R = 0.663; R2 = 0.440; F = 39,973; P < 0.001; Durbin Watson = 1926.

In the regression model, when the t test results regarding the significance of the regression coefficient are examined, it is seen that statistically significant relationships are found in the sub-dimensions of relationships with doctors and other health care professionals and coping with uncertainty. The increase in patients’ perceptions of their relationships with doctors and other health care professionals statistically increases patient satisfaction levels (t = 5.316; P < .05). Likewise, increasing perceptions of coping with uncertainty statistically increases patient satisfaction levels (t = 2001; P < .05). According to the standardized regression coefficient (β), the relative order of importance of the predictor variables on patient engagement is; relationships with doctors and other health care professionals and coping with uncertainty. According to the research hypothesis, hypothesis H 4 was accepted for the relevant dimensions.

Discussion

The validity and reliability results obtained in this study are consistent with the validity and reliability results obtained in international and multilingual studies.5,50

Patient-centered communication has an impact on patient engagement and the regression model shows that statistically significant relationships are found in the sub-dimensions of information exchange and relationships with physicians and other health care professionals. Accordingly, the increase in patients’ perceptions of information exchange statistically increases the level of patient engagement. Physician-patient communication relationship requires active patient participation in treatment. According to a focus group study conducted with patients, providers and administrators, patients, providers and administrators agreed that communication is important in improving patient engagement, including building trust through collaboration and clearly defining roles and responsibilities as well as goals. 51 According to the findings of a study conducted by Saha and Beach (2011) with a group of 248 patients, it was found that as the level of patient-centered communication increases, the level of patient participation in the physician’s decision and the level of approval of the physician’s decision increases. 51 In this study, it was determined that the level of participation of patients increased as the level of information shared by the physician with the patients while making decisions increased. In different studies, it has been revealed that good, honest, 52 open and information-sharing-based communication with patients by nurses increases perceived patient satisfaction by increasing patient participation.53,54 According to the results of a study conducted in Vietnam with 455 patients over the age of 18 with at least one chronic disease, it was found that patient-centered communication approach (non-verbal communication skills and empathy) had a positive relationship with patient engagement. 55 According to another study, it was revealed that the level of patient-centered communication in general positively affects patient engagement. It is stated that more patient-centered communication increases patient activation and patient engagement, while less contact with the patient, which is considered within the scope of nonverbal communication, is associated with less patient engagement.56,57 Effective patient-centered communication strategies are needed to enable patients to engage in treatment adherence and broader positive health behaviors. Previous research suggests that physicians who use more patient-centered communication approaches are more likely to develop positive relationships with patients, leading to positive patient impressions and improved patient outcomes, as well as patient engagement. 55 Helping patients to be more active in consultations requires replacing the dominance of physicians with patients as active participants. This is where the importance of patient-centered communication emerges. Training physicians to be more attentive, informative and empathetic will transform their role from one characterized by authority to one characterized by partnership, solidarity, empathy and collaboration. 58 In this context, the findings show that especially patients’ perceptions of information exchange may positively affect patient engagement. Information sharing, which is a sub-dimension of patient-centered communication, is a phenomenon directly related to the patient’s participation in medical decisions made about him/her.

Increasing the level of patients’ relationship with doctors and other health care professionals also statistically increases the level of patient engagement. Effective patient-centered communication is considered an important element in the therapeutic approach and in optimizing patient participation in treatment. 59 Some other studies in the literature reveal that patient engagement levels increase with the increase in the level of patients’ relationship with service providers. For example, according to a study conducted by Bossou et al (2021) with 355 outpatients in Togo, it was revealed that the relationship between patients and health care providers is an important factor in the provision of medical care services, and that the relationship with doctors and other health care professionals and the interaction with medical service providers increase patient engagement. 60 Similarly, in a study conducted on prostate patients with cancer in Denmark, it was concluded that patients’ level of relationship with service providers affects their participation in decisions. 61 Interventions to improve health literacy, physician-patient communication, shared decision-making and patient self-management are beginning to increase at all levels of the health care system, and the importance of patient-centered communication that focuses on the patient is emphasized in increasing the effectiveness of respect for patient autonomy and patient participation in their treatment. 62 Improving relationships with physicians and other health care professionals may lead to the development of a sense of empathy between physician-patient or patient-service provider, increase the quality of interpersonal communication, and significantly affect the patient’s participation in all processes related to treatment processes and care by taking into account the patient’s biopsychosocial status in treatment processes.

Patient-centered communication has effects on health-related quality of life, and in the regression model, it is seen that the only statistically significant relationship is in the sub-dimension of relationships with doctors and other health care professionals. The increase in patients’ relationships with doctors and other health care professionals leads to an increase in health-related quality of life levels. Communication is a very important component of medical care for both providers and patients. Among the forms of communication in medical care, patient-centered or person-centered care leads to quality health care. 59 The impact of communication and interactions between physicians and patients on patient outcomes is particularly important when it comes to life-threatening diseases such as cancer. 13 The way physicians communicate with patients with cancer can have a significant impact on patients’ health-related quality of life. Several studies in the literature show that there is a significant relationship between physicians’ communication behaviors and patient health outcomes. 34 Similar results have been reported from many studies on the subject.63-66 There is increasing evidence that effective and empathic communication of the physician with patients with cancer and family can affect the patient’s health-related quality of life, satisfaction with care, and medical outcomes in cancer care. 67 The results obtained from a study conducted by Pozzar et al 68 (2021) on the subject are in line with the results of the current study. According to these results, higher levels of patient-centered communication in patients with cancer were found to be positively associated with health-related quality of life and lower symptom burden. The frequency of relationships with doctors and other health professionals was found to increase the quality of health care. Quality of health care was also reported to be associated with better social and family well-being. Relationships with doctors and other health professionals may improve the therapeutic alliance. This will provide a good care experience and social support by involving patients and their relatives more in medical care decisions. In particular, attentive and continuous listening helps physicians to better understand patients’ subjective experiences of illness, which can result in treatment plans that minimize deterioration in patients’ quality of life. 34

Patient-centered communication affects perceptions of service quality and regression analysis results show that increasing patients’ relationships with doctors and other health care professionals and coping with uncertainty increase perceptions of health care quality. Another area where patient-centered communication, a communication style in which patients’ perspectives are actively sought by health care professionals, is effective is the service quality perceived by patients. 69 In a study by Maatouk-Bürmann et al 70 (2016), it was reported that patient-centered communication has an important role in improving the quality of care in terms of therapeutic relationship, patient engagement and treatment processes. Patient-centered communication, which is seen as an important component of high quality service, has been mentioned in many studies. 71 According to the results of a study conducted with the data of 261 patients who applied to a physical therapy and rehabilitation outpatient clinic in Turkey, patient-centered communication was found to increase trust in physicians and positively affect service quality. 72 A similar result was revealed in the study conducted by Eptesin et al. In the study, it was reported that patient-centered communication has an important function in the perception of high quality health services. Reynolds (2009) reported that patient-centered communication has a significant effect on patient satisfaction, which in turn has a significant effect on service quality. 73 In another randomized controlled study, it was found that the patient group interacted by nurses who received 10-hour patient-centered communication training had higher service quality perceptions than the patients in the other group. 74 In another study conducted with 359 patients with cancer, it was found that patient-centered communication increased the service quality perception levels of patients with cancer. 75 In a study of 3959 patients’ data examining the relationship between patient-centered communication between physician and patient, having a usual source of care and health care quality ratings, patients with a usual source of care reported experiencing more patient-centered communication, and it was also found that this patient group had higher levels of quality of care. This study confirmed the importance of patient-centered communication in shaping patients’ perceptions of the quality of their care. 76

The perception of health service quality is influenced by many factors. Among these, the most important one is the relationship between physicians and other health care professionals and patients. 77 In particular, many studies have reported that patient-centered communication improves patient care processes and positively affects the quality of care received by patients. 60,72,77-81 Uncertainty negatively affects the quality of health services received. 82 Therefore, it is stated that the perceived health care quality perception increases with the increase in patients’ ability to cope with uncertainty. 83 Regardless of the stage of the disease, uncertainty is a phenomenon that seriously negatively affects the course of recovery, especially in cancer. It has been reported that by reducing this uncertainty, the patient’s treatment process is faster and more effective by reducing the poor prognosis of the disease and the associated fear.84-88 In general, disadvantaged patients (such as patients with cancer) are among the highest users of the health system. They are also the most vulnerable to system failures in quality and safety, care coordination and efficiency. Therefore, approaches that put patients at the center of care processes and involve patients in their care to improve their perceptions of service quality can greatly benefit from patient-centered communication. 62

Patient-centered communication affects patient satisfaction and according to the results of regression analysis, statistically significant relationships were found in the sub-dimensions of relationships with physicians and other health care professionals and coping with uncertainty. Patient satisfaction is the most widely accepted outcome measure when assessing patients’ perceptions of physicians’ communication skills or the effectiveness of interventions to improve communication in the medical encounter. 13 Patient-centered communication is an important component of patient-centered care and affects patient satisfaction, health-related quality of life, and other important patient outcomes. 36 According to the results of many similar studies conducted with different patient groups, it is stated that patient-centered communication increases the level of patient satisfaction and good communication of patients with health care professionals increases the degree of satisfaction of the patient with the service received and provides a better patient experience.89-93

The increase in patients’ relationships with physicians and other health care professionals statistically increases patient satisfaction levels. In a study evaluating the effectiveness of different approaches aimed at improving physician-patient communication in oncology, patient satisfaction was evaluated as an important outcome in terms of communication and it was revealed that interventions aimed at improving the interaction between patients with cancer and their physicians had positive effects on patient satisfaction. 14 In another study, the quality of oncologist-patient communication was found to significantly affect patient satisfaction with care. 94 According to the results of a meta-analysis study examining the impact of patients with cancer’ level of communication with oncologists on patient outcomes and satisfaction, patient-centered communication was found to have a significant and positive relationship with patient satisfaction. 95 In another study conducted patients with breast cancer, it was found that patients’ perception of patient-centered behavior was strongly related to patients’ satisfaction with information and that patient-centered behavior of physicians increased patient satisfaction. 28 In a randomized controlled study conducted with patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery, nurses were first given patient-centered communication training to improve the interaction between nurses and patients. As a result of this training, it was determined that the patients with whom the nurses who received patient-centered communication training interacted had higher patient satisfaction levels than the patients in the other group. 74 According to the findings of the study conducted by Prakash (2010), it was reported that with the increase in the quality of patients’ relationship with health care professionals, the level of satisfaction with the treatment they received from the hospital also increased. 96 According to the results of a study conducted by Karaca and Durna (2019) on nurses’ communication with patients, it was determined that the quality of nurses’ attitudes and behaviors towards patients increases patient satisfaction. 97 Similarly, the results of a similar study conducted by Chen et al 98 (2019) also reported a positive relationship between the quality of patient communication and the level of satisfaction with the service received. Communication between physicians and other health care professionals and patients is an important satisfaction criterion in patient profiles in every branch. Therefore, the results obtained from both the present study and other similar studies show that communication between patients and health care professionals increases patient satisfaction. Patient-centered communication factors such as patients feeling supported and involved in their care by physicians and other health care professionals, having their concerns and preferences taken into account, and having confidence in the decisions they make with the health care team are effective in increasing patient satisfaction.

The increase in patients’ perceptions of managing uncertainty also statistically increases patient satisfaction levels. Uncertainty is a phenomenon that both healthy and sick individuals are not satisfied with. Especially patients with cancer experience uncertainty intensely due to the situation they are in and the lack of clarity about whether they will respond to the treatment they receive. This uncertainty negatively affects patients’ satisfaction at every stage of diagnosis and treatment. In fact, according to the findings of a randomized controlled study conducted by Frostholm et al 99 (2005), it was found that patients who experienced uncertainty were not satisfied or less satisfied with the health service they received. Similarly, according to the results of a study conducted by Mallinger et al 28 (2005), which examined the relationship between patient-centered care and satisfaction with information in women with a history of breast cancer, it was reported that treated patients were highly satisfied with the information provided about the treatment, but less satisfied with information about the long-term physical, psychological and social sequelae of the disease and treatments. According to another result of the same study, patients’ perception of patient-centered behavior was found to be strongly associated with patients’ satisfaction with information. Johnson et al (1988) state that the way clinical uncertainty is explained to patients and then resolved by the physician affects patients’ satisfaction. 100 In addition, coping with uncertainty has also been found to have an impact on patient satisfaction. Many medical conditions, especially cancer and chronic conditions, involve significant uncertainty. Patients may be uncertain about the course of their illness, treatment options and outcomes. Coping with this uncertainty can be difficult. In this context, the use of a patient-centered communication approach may positively affect patient satisfaction.

Based on these discussions, we can develop an evidence-based framework. Improving communication skills among health care professionals involves measuring the quality of systemic communication. It also involves measuring the quality of individual communication. So, it is important to focus on both systemic and individual communication quality. It entails promoting equal and high-level patient-centered communication for all cancer patients. It’s crucial to check the effectiveness of health care professionals’ communication strategies. This requires making adjustments and developing strategies to involve patients in communication. Efforts to ease excessive appointments are essential, allowing adequate time for physician-patient communication. Health care professionals should ensure personalized services for disadvantaged patients like patients with cancer. They should do this from a bio-psychosocial perspective. It is crucial to encourage patients to engage and actively participate in communication with health care providers. Decision makers need to identify individual and system-level obstacles to patient-centered communication. They should then develop solutions to eliminate these obstacles. This will promote a more effective and inclusive health communication environment.13,21,50,59,90

Study Limitations

This study was conducted on patients receiving outpatient and inpatient cancer treatment at a training and research hospital in Diyarbakır. Therefore, the results of the study cover only the patients receiving outpatient and inpatient treatment at this hospital and cannot be generalized to patients receiving outpatient and/or inpatient treatment at other hospitals (public, private and university). While conducting this research, a specific type of cancer was not selected, and it can be thought that the diversity of diagnoses in the sample may have prevented the effect of diagnosis or treatment on communication. In addition, the level of patient-centered communication may differ in different cancer types. Although there are different quality of life scales for different types of cancer in the literature, it was preferred to use the general health-related quality of life scale since all patients with cancer were reached regardless of diagnosis within the scope of this study.

Conclusion

Communication between adult patients with cancer and their health care providers is an important factor in the overall health care experience, contributing to patients’ engagement in treatment, satisfaction with treatment and health care, positive perceptions of health care quality, and ultimately influencing numerous health behaviors and outcomes. It is important to accurately measure patient-centered communication in patients with cancer and to understand how this communication affects other health outcomes. In the light of this information, it is important to examine the communication experiences of patients with cancer and the quality of the communication relationship with the service provider, to improve the communication skills of the patient and the service provider, to present patient-centered communication as an integral part of patient-centered care in health systems, and to improve health outcomes by embedding a patient-centered communication perspective.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the participants of the study for their contribution.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: The data was collected by Cuma ÇAKMAK. The data were analyzed by Özgür UĞURLUOĞLU. Cuma ÇAKMAK did the literature research, and all authors have contributed to preparing the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

To conduct the study, the necessary permissions were obtained from Hacettepe University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee on 16.05.2021 with 2021/06-70 decision number in Ankara and from Ministry of Health, Diyarbakır Provincial Health Directorate on 25.06.2021 with 97893136 number.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article and the consent forms were confidentially stored.

ORCID iD

Cuma Çakmak https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4409-9669

References

- 1.Jenerette CM, Mayer DK. Patient-Provider communication: the rise of patient engagement. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2016;32(2):134-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1489-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeve BB, Thissen DM, Bann CM, et al. Psychometric evaluation and design of patient-centered communication measures for cancer care settings. Patient Educ Counsel. 2017;100(7):1322-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown SJ. Patient-centered communication. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 1999;17:85-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston W, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman T. Patient-centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. London: CRC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa H, Hashimoto H, Kiuchi T. The evolving concept of “patient-centeredness” in patient–physician communication research. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Street RL. The many “Disguises” of patient-centered communication: problems of conceptualization and measurement. Patient Educ Counsel. 2017;100(11):2131-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gattellari M, Butow PN, Tattersall MH. Sharing decisions in cancer care. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(12):1865-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Street RL. How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome. Patient Educ Counsel. 2013;92(3):286-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, de Haes JC. Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Educ Counsel. 2000;41(2):145-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bredart A, Bouleuc C, Dolbeault S. Doctor-patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(4):351-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coulter A. Patient engagement—what works? J Ambul Care Manag. 2012;35(2):80-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barello S, Graffigna G, Vegni E. Patient engagement as an emerging challenge for healthcare services: mapping the literature. Nursing Research and Practice. 2012;2012:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(3 Suppl):S110-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Wever LD, Schornagel JH, Aaronson NK. Patient-physician communication during outpatient palliative treatment visits: an observational study. JAMA. 2001;285(10):1351-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catt SL, Ahmad S, Collyer J, Hardwick L, Shah N, Winchester L. Quality of life and communication in orthognathic treatment. J Orthod. 2018;45(2):65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhofaian A, Zhang A, Gary FA. Relationship between Provider communication behaviors and the quality of life for patients with advanced cancer in Saudi Arabia. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(4):2893-2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strayhorn SM, Lewis-Thames MW, Carnahan LR, et al. Assessing the relationship between patient-provider communication quality and quality of life among rural cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):1913-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendoza MD, Smith S, Eder M, Hickner J. The seventh element of quality: the doctor-patient relationship. Family Med. 2011;43(2):83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Onco Practice. 2015;11(2):145-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seccareccia D, Wentlandt K, Kevork N, et al. Communication and quality of care on palliative care units: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(9):758-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, Rowland JH. How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? Exploring associations and pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(29):3554-3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asare M, Fakhoury C, Thompson N, et al. The patient–provider relationship: predictors of black/African American Cancer patients’ perceived quality of care and health outcomes. Health Commun. 2020;35(10):1289-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract. 1988;15(5):480-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallinger JB, Griggs JJ, Shields CG. Patient-centered care and breast cancer survivors’ satisfaction with information. Patient Educ Counsel. 2005;57(3):342-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clever SL, Jin L, Levinson W, Meltzer DO. Does doctor–patient communication affect patient satisfaction with hospital care? Results of an analysis with a novel instrumental variable. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(5p1):1505-1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thind A, Liu Y, Maly RC. Patient satisfaction with breast cancer follow-up care provided by family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:710-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang S. Pathway linking patient-centered communication to emotional well-being: taking into account patient satisfaction and emotion management. J Health Commun. 2017;22(3):234-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finefrock D, Patel S, Zodda D, et al. Patient-centered communication behaviors that correlate with higher patient satisfaction scores. Journal of Patient Experience. 2018;5(3):231-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Versluijs Y, Lemmers M, Brown LE, Gonzalez AI, Kortlever JT, Ring D. The correlation of communication effectiveness and patient satisfaction. Journal of Patient Experience. 2021;8:2374373521998839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(5):791-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spooner KK, Salemi JL, Salihu HM, Zoorob RJ. Disparities in perceived patient–provider communication quality in the United States: Trends and correlates. Patient Educ Counsel. 2016;99(5):844-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treiman K, McCormack L, Olmsted M, et al. Engaging patient advocates and other stakeholders to design measures of patient-centered communication in cancer care. The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2017;10(1):93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573-577. Crossref. PubMed. ISI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.RTI International . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Instrument User Guide. U.S.A: RTI International. https://www.rti.org/impact/patient-centered-communication-cancer-care-instrument (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Cancer Institute . Health Information National Trends Survey. U.S.A: National Cancer Institute. https://hints.cancer.gov/ (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 40.EuroQol Research Foundation . EQ-5D-3L User Guide. Netherlands: EUROQOL OFFICE. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-3l-about/ (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasan S, Sulieman H, Stewart K, Chapman CB, Hasan MY, Kong DC. Assessing patient satisfaction with community pharmacy in the UAE using a newly-validated tool. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9(6):841-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roder-DeWan S, Gage AD, Hirschhorn LR, et al. Expectations of healthcare quality: a cross-sectional study of internet users in 12 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2019;16(8):e1002879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong H, Oh HJ. The effects of patient-centered communication: exploring the mediating role of trust in healthcare providers. Health Commun. 2020;35(4):502-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centre for Health Service Development. The Short Assessment of Patient Satisfaction (SAPS). Australia: University of Wollongong; 2015. chrome-extension https://www.continence.org.au/sites/default/files/202005/Academic_Report_Short_Assessment_of_Patient_Satisfaction_SPAS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.IBM Corp. Released 2013 . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saygılı M. Üç Farklı Palyatif Bakım Hizmet Modelinin Kanserli Hasta–Hastaya Bakım Veren Aile Üyeleri Açısından Değerlendirilmesi Ve Maliyet-Etkililik Analizi. Doktora Tezi. Ankara: Hacettepe Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ergen Hİ. Açık Karpal Tünel Gevşetme Cerrahisi Uygulanan Bireylerde Aktivite Temelli Propriyoseptif Duyu Eğitiminin Aktivite Limitasyonu, Elin Fonksiyonel Kullanımı Ve Yaşam Kalitesine Etkisinin Incelenmesi. Doktora Tezi. Ankara: Hacettepe Üniversitesi, Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seyfioğlu EF, Başdaş NÜ. Değer temelli sağlık hizmetlerinde bir değer bileşeni olan hasta sonuçlarının ölçümü ve önemi. Hacettepe Sağlık İdaresi Dergisi. 2021;24(2):399-414. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Cancer Institute . Cancers by Body Location/System. U.S.A: National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/by-body-location (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al Shamsi H, Almutairi AG, Al Mashrafi S, Al Kalbani T. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: a systematic review. Oman Med J. 2020;35(2):e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellows M, Burns KK, Jackson K, Surgeoner B, Gallivan J. Meaningful and effective patient engagement: what matters most to stakeholders. Patient Exp J. 2015;2(1):18-28. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saha S, Beach MC. The impact of patient-centered communication on patients’ decision making and evaluations of physicians: a randomized study using video vignettes. Patient Educ Counsel. 2011;84(3):386-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bello O. Effective Communication in Nursing Practice: A Literature Review. United Kingdom: Yrkeshögskolan Arcada. https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/130552 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruben BD. Communication theory and health communication practice: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Health Commun. 2016;31(1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKinley C, Limbu Y, Pham L. An investigation of processes linking patient-centered communication approaches to favorable impressions of Vietnamese physicians and hospital services. Int J Soc Cul Lan. 2020;8(1):44-59. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rathert C, Mittler JN, Banerjee S, McDaniel J. Patient-centered communication in the era of electronic health records: what does the evidence say? Patient Educ Counsel. 2017;100(1):50-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Street RL, Jr, Liu L, Farber NJ, et al. Provider interaction with the electronic health record: the effects on patient-centered communication in medical encounters. Patient Educ Counsel. 2014;96(3):315-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruben MA, Blanch-Hartigan D, Hall JA. Communication skills to engage patients in treatment. The Wiley Handbook of Healthcare Treatment Engagement: Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. U.K: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2020:274-296. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bossou YJ, Qigui S, George-Ufot G, Bondzie-Micah V, Muhimpundu N. The effect of patient-centered communication on patient satisfaction: exploring the mediating roles of interpersonal-based medical service encounters and patient trust. (NAAR) Journal. 2021;4(1):4479730. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Birkeland S, Bismark M, Barry MJ, Möller S. Is greater patient involvement associated with higher satisfaction? Experimental evidence from a vignette survey. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(2):86-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osborn R, Squires D. International perspectives on patient engagement: results from the 2011 Commonwealth Fund Survey. J Ambul Care Manag. 2012;35(2):118-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chandra S, Mohammadnezhad M, Ward P. Trust and communication in a doctor- patient relationship: a Literature Review. J Healthc Commun. 2018;3(3):36. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chipidza FE, Wallwork RS, Stern TA. Impact of the doctor-patient relationship. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(5):1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kieft RA, de Brouwer BB, Francke AL, Delnoij DM. How nurses and their work environment affect patient experiences of the quality of care: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J. Impact of nurse-patient relationship on quality of care and patient autonomy in decision-making. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(3):835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baile WF, Aaron J. Patient-physician communication in oncology: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(4):331-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pozzar RA, Xiong N, Hong F, et al. Perceived patient-centered communication, quality of life, and symptom burden in individuals with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163(2):408-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stewart MA. What is a successful doctor-patient interview? A study of interactions and outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 1984; 19(2), 167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maatouk-Bürmann B, Ringel N, Spang J, et al. Improving patient-centered communication: results of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Counsel. 2016;99(1):117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1516-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Çakmak C, Uğurluoğlu Ö. Hasta merkezli iletişim ve hizmet kalitesi ilişkisi: hizmet sunucuya güvenin aracı etkisi. Dicle Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi 2022;12(23):93-108. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reynolds A. Patient-centered care. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):133-147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolf DM, Lehman L, Quinlin R, Zullo T, Hoffman L. Effect of patient-centered care on patient satisfaction and quality of care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23(4):316-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blanch-Hartigan D, Chawla N, Beckjord EI. et al. Cancer survivors’ receipt of treatment summaries and implications for patient-centered communication and quality of care. Patient Educ Counsel. 2015;98(10):1274-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Finney Rutten LJ, Agunwamba AA, Beckjord E, Hesse BW, Moser RP, Arora NK. The relation between having a usual source of care and ratings of care quality: does patient-centered communication play a role? J Health Commun. 2015;20(7):759-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang J. Examining the Relationship Among Patient-Centered Communication, Patient Engagement, and Patient’s Perception of Quality of Care In the General U.S. Adult Population. Theses and Dissertations. South Carolina: University of South Carolina; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Andaleeb SS. Service quality perceptions and patient satisfaction: a study of hospitals in a developing country. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(9):1359-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Karliner LS, Hwang ES, Nickleach D, Kaplan CP. Language barriers and patient-centered breast cancer care. Patient Educ Counsel. 2011;84(2):223-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lateef MA, Mhlongo EM. A qualitative study on patient-centered care and perceptions of nurses regarding primary healthcare facilities in Nigeria. Cost Eff Resour Allocation: C/E. 2022;20(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wanzer MB, Booth-Butterfield M, Gruber K. Perceptions of health care providers’ communication: relationships between patient-centered communication and satisfaction. Health Commun. 2004;16(3):363-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.George RE, Lowe WA. Well-being and uncertainty in health care practice. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):298-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han PKJ, Klein WMP, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(6):828-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bartley N, Napier CE, Butt Z, et al. Cancer patient experience of uncertainty while waiting for genome sequencing results. Front Psychol. 2021;12:647502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Borneman T, Irish T, Sidhu R, Koczywas M, Cristea M. Death awareness, feelings of uncertainty, and hope in advanced lung cancer patients: can they coexist? Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(6):271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harrison M, Han PKJ, Rabin B, et al. Communicating uncertainty in cancer prognosis: a review of web-based prognostic tools. Patient Educ Counsel. 2019;102(5):842-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Karlsson M, Friberg F, Wallengren C, Öhlén J. Meanings of existential uncertainty and certainty for people diagnosed with cancer and receiving palliative treatment: a life-world phenomenological study. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.van Someren JL, Lehmann V, Stouthard JM, Stiggelbout AM, Smets EMA, Hillen MA. Oncologists’ communication about uncertain ınformation in second opinion consultations: a focused qualitative analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:635422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Agha Z, Schapira RM, Laud PW, McNutt G, Roter DL. Patient satisfaction with physician-patient communication during telemedicine. Telemed J e Health. 2009;15(9):830-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lang EV. A better patient experience through better communication. J Radiol Nurs. 2012;31(4):114-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Salmon P. Improving the Patient Experience with Communication Doctoral Thesis. Washington (DC): Walden University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Siebinga VY, Driever EM, Stiggelbout AM, Brand PLP. Shared decision making, patient-centered communication and patient satisfaction – a cross-sectional analysis. Patient Educ Counsel. 2022; 105(7), 2145-2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Touati R, Sailer I, Marchand L, Ducret M, Strasding M. Communication tools and patient satisfaction: a scoping review. J Esthetic Restor Dent. 2022;34(1):104-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bitar R, Bezjak A, Mah K, Loblaw DA, Gotowiec AP, Devins GM. Does tumor status influence cancer patients’ satisfaction with the doctor-patient interaction? Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(1):34-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Venetis MK, Robinson JD, Turkiewicz KL, Allen M. An evidence base for patient-centered cancer care: a meta-analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Educ Counsel. 2009;77(3):379-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prakash B. Patient satisfaction. J Cutan Aesthetic Surg. 2010;3(3):151-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karaca A, Durna Z. Patient satisfaction with the quality of nursing care. Nurs Open. 2019;6(2):535-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen Q, Beal EW, Okunrintemi V, et al. The Association between patient satisfaction and patient-reported health outcomes. J Patient Exp. 2019;6(3):201-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frostholm L, Fink P, Oernboel E, et al. The uncertain consultation and patient satisfaction: the impact of patients’ illness perceptions and a randomized controlled trial on the training of physicians’ communication skills. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):897-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Johnson CG, Levenkron JC, Suchman AL, Manchester R. Does physician uncertainty affect patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(2):144-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]