Abstract

Introduction

Scar massage is a commonly used treatment in hand therapy. The current empirical evidence that supports it is disparate and of variable quality, with no established effective dosage and method proposed. This study aimed to identify the current practice among Australian hand therapists using massage as an intervention for scarring following surgery to the hand and upper limb.

Methods

A purposely designed self-report online survey was emailed to current members of the Australian Hand Therapy Association (n = 958). Data collected included demographics, intervention techniques, conditions treated and protocols, scar assessment and knowledge and training about scar massage as a clinical intervention.

Results

A total of 116 completed questionnaires were received (a response rate of 12.1%). All respondents used scar massage as part of their clinical practice with 98% to improve soft tissue glide (n = 114), 92% for hypersensitivity (n = 107), and 84% to increase hand function (n = 97). Only 18% (n = 21) of respondents used standardised outcome measures, and most therapists had learned scar massage from a colleague (81%).

Conclusions

Commonalities in how respondents implemented scar massage were found. Participants reported relying primarily on clinical experience to inform their practice. Whilst scar massage was widely used, few respondents had received formal skills training or completed outcome measures regularly to formally evaluate its clinical efficacy or impact. Replication of this study with a larger international sample of participants is warranted to determine if these findings reflect general practice.

Keywords: Cicatrix, massage, rehabilitation, surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Treating hand and upper limb scars following surgery is routine in hand therapy practice. 1 Scars can be aesthetically displeasing and cause physical limitations and sensory disturbance.2,3 Effective treatment is integral to ensuring optimal recovery. 1 Scar management is recognised as an important part of hand therapy practice, and scar massage is a recommended technique for scar management in key hand therapy reference texts.4,5 The 2019 practice analysis survey by the Hand Therapy Certification Committee identified scar management as a critical skill for optimizing patient outcomes in hand therapy practice. 6 Scar management can include but is not exclusive to massage, compression therapy, silicone products, the application of orthoses, and exercise interventions. 3

Scar massage is a commonly used intervention for treating post-surgical scarring. However, a recent scoping review identified that scar massage research is varied and lacks consistency concerning the intervention protocols and outcome measures. 7 The review also found only two papers reporting on upper limb surgical scar outcomes following massage, though only one of these examined massage in isolation.8,9 Neither paper detailed the specific massage techniques used, making it difficult to compare or allow therapists to replicate the findings in their clinical practice. The effective dosage of scar massage, the application method and the optimal time to commence using it have not been elucidated to date. 10 The absence of scientifically evaluated benefit for intervention is not necessarily a reason to avoid using it but should be considered an indication that research is needed. 11

A national survey of Australian hand therapists was identified as an initial step to understanding practice patterns in implementing and evaluating clinical outcomes of post-surgical scar massage. A survey was chosen to reach a greater number of hand therapists than would be possible by other means, to identify the gaps between clinical practice and the available evidence to better inform future studies on scar massage and training needs.

Purpose of study

This survey aimed to identify the current practice trends of Australian hand therapists in the application of massage to treat scarring in patients following surgery to the hand and upper limb, excluding burn scar treatment. The research aimed to present a profile of the hand therapists using scar massage, the characteristics of the patient caseload receiving it, any commonalities in intervention protocols and scar assessment scales being used, and insights into hand therapists’ skill development in this area. The specific research questions were:

1. What intervention approaches are used by Australian hand therapists to treat post-surgical scars with massage?

2. How do Australian hand therapists measure outcomes in patients with post-surgical scarring?

3. How do Australian hand therapists develop their knowledge and skills in scar massage application?

4. Do years of experience or clinical practice settings affect Australian hand therapists’ prescription of scar massage?

Methods

The study was a cross-sectional descriptive survey. Ethics was granted by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee on 20/07/2021 (project ID 28091). The “Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys” (CHERRIES) guideline was used to inform the survey formatting and design. 12

Participants

The target population were members of the Australian Hand Therapy Association (AHTA), the peak national body representing hand therapists. The AHTA is a not-for-profit, member-based organisation of occupational therapists and physiotherapists who provide hand therapy services. Membership is voluntary and incurs a yearly fee. It is primarily composed of Associate and Accredited Hand Therapist (AHT) levels of members. Associate membership is open to any Australian registered occupational therapist or physiotherapist, while the AHT credential is awarded to hand therapists who demonstrate an advanced level of competence in hand therapy. The credentialing process developed by the AHTA involves completing over 300 h of upper limb education and assessment, a minimum of 3600 h of direct hand therapy clinical practice and participation in a 12-months mentorship program, including direct observation to ensure safe and evidence-based practice. The membership of the AHTA was 958 (including 391 AHTs) at the time of survey commencement in August 2021. 13 Inclusion criteria included: being an occupational therapist or physiotherapist registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), practising in Australia, and actively working in hand therapy as part or all their daily professional practice.

Survey instrument

The first author (HS) developed a purposely designed survey tool in collaboration with the remaining authors (LR, TB), experienced in survey research. Four clinician-researchers and two university academic staff with knowledge of hand therapy completed functionality, face validity and field testing through two rounds of pilot testing. The responses informed changes to the structure of the survey to improve its contents, readability, and clinical relevance. The first pilot test identified that different therapy approaches were considered for scar-affecting cutaneous or superficial structures and those used for targeting deeper tissues. The survey was, therefore, adjusted to assess these separately. Superficial scarring was defined as “involving only the skin (epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous fat)”, and deep scarring was defined as “involving both the skin and underlying tissues (such as tendon and bone and may involve tissue adhesions).” The second round of pilot testing resulted in minor changes to phrasing only, with no changes to question content.

The final survey comprised 40 questions, including closed (forced choice), open free text, and ranking questions. 10 questions addressed demographics, 22 questions considered interventions, four focused on scar assessment, and four related to scar massage knowledge. The AHTA research and scholarship sub-committee approved the survey to be distributed to its membership group. Participants were invited to complete the survey through a generic email via the AHTA mailing list. The researchers were, therefore, blind to potential participants’ identities.

Data collection and analysis

Participant responses were collected using the online survey program Qualtrics XM(Seattle, USA). The survey was open for 8 weeks, from August to October 2021. AHTA members received two reminder emails in the final 4 weeks of the data collection period. Respondents provided consent by agreeing to the opening question, and no identifying information was collected, ensuring respondents’ anonymity. Data analysis was completed using Microsoft Excel, and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26. 14 Descriptive statistics, including percentages, means, ranges, and standard deviations, were calculated.

Results

A total of 146 responses were received. 30 questionnaires were incomplete and were excluded from data analysis leaving 116 available for analysis. This represents a response rate of 12.1% of AHTA members invited, and 20.2% of AHTs.

Most participants were occupational therapists (n = 88), with physiotherapists accounting for 24.1% (n = 28), and 16.4% had completed a higher postgraduate qualification, including a Master’s degree or PhD. Participants were generally very experienced, with 62.9% (n = 73) reporting 10 or more years working in hand therapy compared to 7.8% (n = 9) with less than 2 years of experience. Hand therapy credentials, including Certified Hand Therapist, AHT and/or postgraduate certificates, were held by 75.9% (n = 88) of participants. Survey participants’ demographic information is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents (n = 116).

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Primary health profession | Occupational therapy | 88 (75.9) |

| Physiotherapy | 28 (24.1) | |

| Recency of practice | <18 months | 72 (62.1) |

| >18 months | 27 (23.3) | |

| Years working in hand therapy | 0–2 years | 9 (7.8) |

| 2–5 years | 10 (8.6) | |

| 5–10 years | 24 (20.7) | |

| 10–15 years | 21 (18.1) | |

| >15 years | 52 (44.8) | |

| State | ACT | 3 (2.6) |

| NSW | 33 (28.4) | |

| NT | 3 (2.6) | |

| QLD | 29 (25.0) | |

| SA | 4 (3.4) | |

| TAS | 1 (0.9) | |

| VIC | 30 (25.9) | |

| WA | 13 (11.2) | |

| Practice location | Metropolitan | 82 (70.7) |

| Regional | 32 (27.6) | |

| Rural | 0 (0.0) | |

| Remote | 2 (1.7) | |

| Highest qualification | Bachelor degree | 84 (72.4) |

| Entry level master’s degree | 6 (5.2) | |

| Postgraduate master’s degree | 11 (9.5) | |

| PhD (hand therapy) | 6 (5.2) | |

| PhD (other) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Other | 7 (6.0) | |

| Additional qualifications | AHT | 79 (68.1) |

| CHT | 43 (37.1) | |

| Postgraduate certificate | 8 (6.9) | |

| Other | 6 (5.2) | |

| No additional qualifications | 24 (20.7) | |

| Type of work | Public | 61 (52.6) |

| Private | 31 (26.7) | |

| Both | 24 (20.7) | |

ACT = Australian Capital Territory; NSW = New South Wales; NT = Northern Territory; QLD = Queensland; SA = South Australia; TAS = Tasmania; VIC = Victoria; WA = Western Australia; AHT = Accredited Hand Therapist as awarded by the Australian Hand Therapy Association; CHT = Certified Hand Therapist; PHD = Doctor of Philosophy.

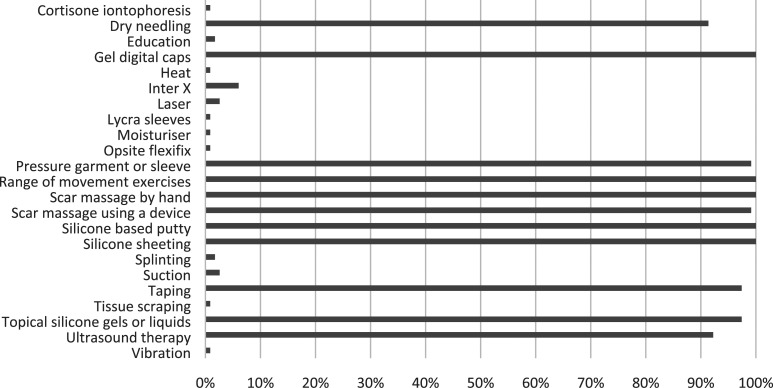

All respondents used scar massage in their hand therapy practice for post-surgical scar management, with 99% using it in conjunction with other treatments (such as taping, silicone products and exercise) rather than in isolation (see Figure 1 for the additional treatment modalities reported). Scar massage typically commenced immediately to 1 week post suture removal (n = 74) or within 3 weeks following surgery (n = 11). Only 5% (n = 6) of respondents would delay scar massage until a problematic scar became apparent. Nearly all respondents (94.8%) reported they would treat post-surgical scarring at least once a week, with 59.5% providing scar treatment daily. When asked what conditions therapists most commonly treat for scarring following surgery, the most frequent responses were fractures treated by open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) (94%), Dupuytren’s disease (91.4%), and tendon injury (86.2%). The lowest use was reported for DeQuervains release (65.5%).

Figure 1.

Frequency of use of different scar intervention methods post-surgery.

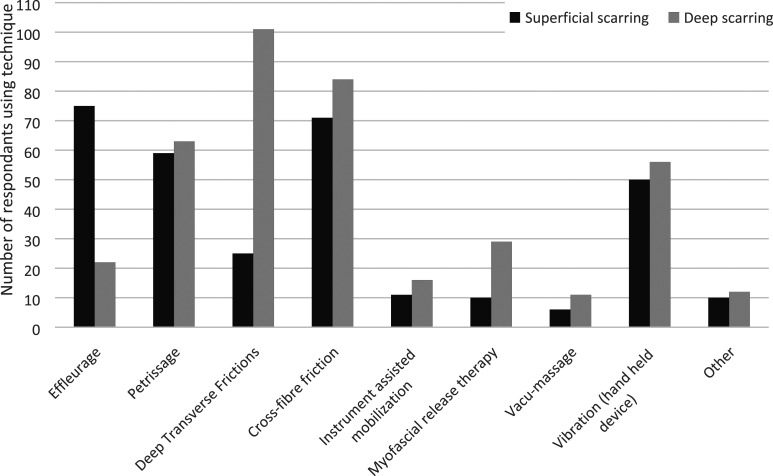

The most frequently identified reason for using scar massage was to improve soft tissue glide or reduce adhesions (98%), followed by reducing hypersensitivity (92%) and improving hand function (84%). Deep and superficial transverse fibre frictions (25% and 22%, respectively) were the techniques most implemented to achieve improved soft tissue glide. Effleurage was used to improve hypersensitivity, pain, patient mood, and rapport. While most respondents used different techniques when providing treatment for superficial and deep scarring, 16% did not vary their practice for such presentations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Massage techniques used for post-surgical scar management.

There were important similarities in scar massage approaches on the duration, frequency, and number of weeks that massage was recommended for both superficial and deep scarring (see Table 2). The use of a lotion by the patient when completing massage was recommended by 76.7% of participants for superficial scarring and 56.9% for deep scarring. The most frequently prescribed home program was three times daily, for 5 minutes for 12 weeks, for both superficial and deep scarring. Survey respondents identified that they would consider wound healing, skin quality and the patient diagnosis in determining if scar massage was appropriate for a patient, though six participants reported they were unaware of any contraindications. No conditions were consistently identified as being unsuitable for scar massage, with 58 participants responding that they would use scar massage with all post-surgical patients.

Table 2.

Scar massage intervention frequency and duration.

| Average | SD | Mode | Median | IQR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q3 | |||||

| Superficial scarring | ||||||

| Frequency of scar massage (times per day) | 3.94 | 1.62 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Duration of each massage session (minutes) | 4.34 | 2.78 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Duration of treatment (weeks) | 12.78 | 8.33 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 12 |

| Deep scarring | ||||||

| Frequency of scar massage (times per day) | 4.46 | 1.89 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Duration of each massage session (minutes) | 5.05 | 3.88 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Duration of treatment (weeks) | 18.95 | 13.27 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 24 |

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range; Q1 = first quartile; Q3 = third quartile.

Assessment

Standardised assessments, defined as outcome measures that have undergone psychometric testing and can be applied in a systematic way to all patients, 15 were only used by a few respondents (n = 21), with 82% reporting that they do not use a standardised outcome measure for scar treatment or management. There was no difference in the use of outcome measures between AHTs and other hand therapists and some participants reported using more than one type of standardised assessment. The Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) 16 was the most used (n = 14), followed by the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) 17 (n = 11). Participants also reported using a modified VSS (n = 2), digital callipers (n = 1) and the ClinMAPS Pro 18 phone application (n = 4). Five participants reported that they were unaware that scar assessment scales existed.

Participants who reported not using standardised scar scales provided varying information about how they assessed scar changes over time, with 44 stating that they would document a description but did not specify what that involved. The second most frequent method was to track change and progress using photographs (n = 24). For specific descriptors, the most frequently recorded were colour (n = 30), adhesions (n = 12), and height (n = 11). 12 respondents identified the patients’ opinion or report of their scar as forming part of their assessment.

Respondents named several barriers to using scar assessment outcome measures. These included: (i) it was not standard practice in the clinician’s workplace (28%), (ii) there was insufficient time to complete an assessment (26%), and (iii) there was a cost barrier to the preferred assessment (1%). Nearly one-quarter of respondents (24%) reported no barriers to using a scar assessment in their workplace. Several respondents supplied additional information that they felt existing scar outcome measures were not necessarily sensitive to changes in hand scars and that the assessment was not a priority given the limited time during scheduled hand therapy sessions. Telehealth was also noted by a small number of therapists to increase the difficulty of assessing scars but was not specifically identified as a barrier.

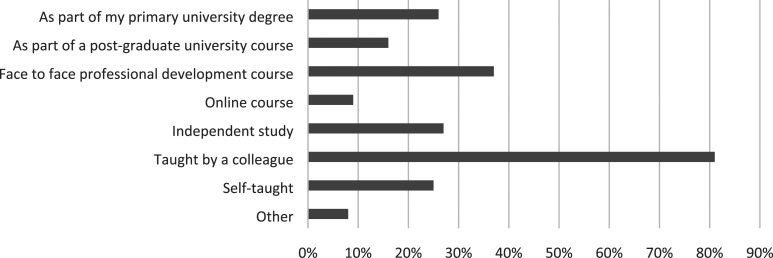

Knowledge base

Most respondents reported learning scar massage as a treatment modality from a colleague, with smaller numbers receiving training through professional development courses, their degree or independent study (see Figure 3). Regarding evidence that supports the use of scar massage in treating surgical scarring, a quarter of participants were unsure what the evidence is to support its use, 38% identified that research is weak or inconclusive, 25% felt there is moderate evidence to support its use, and 11% reported there is strong evidence. 14 therapists additionally reported that they select scar massage based on their earlier clinical experience of benefit rather than known empirical evidence.

Figure 3.

How hand therapists learn about scar massage.

Years of experience and scar massage

Those with less than 10 years of experience were more likely to prescribe a longer average duration of 4.79 min (SD = 2.4) compared to therapists with greater than 10 years of experience, who prescribed 3.92 min (SD = 2.02).

Hand therapy clinic setting

The only difference found between clinical practice in private and public settings in this sample was that hand therapists working in a privately funded clinic were more likely to apply scar massage in a therapy session in addition to a home program, with 80% of private therapists completing both in session and home exercise as compared to 54.4% of public therapists.

Discussion

This survey sought to identify how AHTA members use and measure post-surgical scar massage in their clinical practice. The overall findings of this study were that post-surgical scar massage was used by all respondents, but only a small number of these implemented standardized outcome measures in their practice. Most respondents had developed their knowledge and skills by learning from a colleague rather than through formal training, and there were no substantial differences in clinical practice identified related to the clinical setting or the therapists’ years of experience. The results of this survey demonstrate commonalities in hand therapy practice for scar massage among AHTA member respondents, despite the limited research evidence available to support its use. 7 To inform their practice, the respondents appear to rely on clinical experience and current practices may have developed from a trend of learning from colleagues and generalising findings from other fields.

This study identified that hand therapists typically prescribe scar massage to be completed three to five times daily for three to 5 minutes for an average of 12 weeks following surgery. How therapists have arrived at these similar protocols is not known. This common practice approach is similar to the published protocol suggested by Donnelly (2002) of 5–10 min 3–4 times daily. 8 This differs from the advice for burns scar massage which is recommended for a minimum of 10 min. 19

The similarity in practice across sites may reflect practice trends that have been established by senior hand therapists and passed on to therapists in training. Expert therapists often provide mentoring to less experienced therapists to support their learning and achievement of competencies in hand therapy practice. 20 This study found that 81% of hand therapists had learnt all or part of their scar massage from a colleague. The influence of senior therapists on new therapists’ practice may be understood by applying Lave and Wenger’s theory of situated learning, where learners achieve skills and knowledge embedded in activity through social interaction with others in a “community of practice.” 21 Wackerhausen 22 expands further on this idea of new practitioners learning by imitation of experienced members of the community of practice, describing the process of teaching the novice “to become one of our kind” to practise in the way that the community practices.

A surprising finding is that several respondents were unaware of potential contra-indications that exist for scar massage. This finding suggests that informal training is not necessarily consistent among Australian hand therapy services and may not meet training therapists’ needs. Unlike the United Kingdom and the United States of America, scar-specific training opportunities are limited in Australia. Since this survey was completed the AHTA has commenced running an elective course on wound management that includes scar management as part of the AHT education program.

Evidence-based practice includes the integration of research and clinical experience. 23 In situations where evidence is not substantial enough to inform practice, professional knowledge will guide how to best deliver patient-centered care. Results from this study suggest the practice of scar massage in this sample is based on the clinical knowledge of experienced hand therapists. However, for this knowledge to be considered a credible source of information in evidence-based practice it needs to be explicit, reflected upon and critiqued such as evidence in the literature would be to prevent bias. 24 Valdes 25 stated that while hand therapists are willing to make some changes to their practice based on research literature, they were less likely to change the use of modalities. Further, while hand therapists reported valuing evidence-based practice, they relied more on personal experience in making treatment decisions. 26

Two further unexpected findings included that a number of hand therapists were unaware that standardized outcome measures exist for scarring, and that most hand therapists in this study, including 64 AHT credentialed therapists, reported not using any standardized scar assessments in their practice. Routine outcome measures are essential for therapists to demonstrate the effectiveness of a treatment, as well as to inform clinical decision-making and to communicate progress to patients and key stakeholders effectively. 27 Most respondents in this survey did not use standardized outcome measures to track improvements in scar characteristics in their patients but did record descriptions such as color, height, pliability and thickness of scars, which are common clinical observations used in scar assessment scales. 28 It has been reported that clinicians are more likely to be positively biased when assessing patient progress if they are relying only on subjective judgement, reinforcing the importance of objective measures to ensure accurate assessment. 29

Duncan and Murray 27 (2012) identified clinician knowledge of assessments or lack thereof, and the perceived value of the assessment influenced the uptake of assessments. Their study also identified a correlation between a higher degree or speciality practice and the increased use of outcome measures. A similar finding was not made in this study, possibly due to most therapists having a similar level of experience, with 75% of participants reporting they had attained additional hand therapy speciality qualifications (CHT, AHT).

Several respondents commented that the scar outcome measures available were either inappropriate or too time-consuming to implement within their clinical practice. One of the more frequently used assessments in this survey, the POSAS takes less than 5 min to complete both observer and patient sections. 30 Jaeger Pederson and Kristensen (2016) found that a therapist’s opinion of the meaningfulness of an outcome measure influences the likelihood that it would be successfully implemented. 31 Lack of time is a frequently identified barrier to the use of outcome measures in rehabilitation. 27 Time constraints may be multifaceted, including not only the time required to administer an assessment but also the limited time allocated to each patient’s appointment, the number of patients a therapist needs to see and the number of assessments the therapist needs to administer to each of those patients. 27 Participants in this study identified that other assessments, such as range of motion measures were of greater importance in tracking patient recovery following surgery.

This survey has a number of limitations. The use of convenience sampling carries the risk of volunteer bias 32 by reaching known hand therapy practitioners through distribution to members of the AHTA and excluding therapists working in the field of hand therapy who were not members of AHTA. This may also account for the under-representation of early career therapists who may be less likely to have become members or practising hand therapists who are non-AHTA members. A self-report survey can also lead to social desirability bias, and participants may have provided responses they deemed to be viewed favourably by others, rather than a true report. 32 This survey was made anonymous to attempt to mitigate this effect.

The results of this study cannot be generalised to the wider Australian hand therapists’ population. The response rate for this study was 12.1%, which is below the average response rate of 33% reported by Nulty, 33 but is comparable to other recent surveys of Australian hand therapists by O’Brien et al., 34 and Sim et al. 35 The possible explanations for the low response rate may include the length and depth of questions in the survey, approximately 20% of participants who commenced the survey did not complete it. This may suggest that the time burden to complete it was too great. It is also possible that some of the low response rate is attributable to the data collection period occurring in a time of increased clinical demand on therapists during the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Government public health directives also meant that many hand therapists were only able to provide telehealth consultations during the pandemic which may have changed their usual practice and consequently the results of this survey.

This study indicates that further research is warranted to understand how the wider hand therapy community is using and evaluating outcomes in post-surgical scar massage. The survey developed for this study was effective in eliciting an understanding of respondents' clinical practice and could be used in an international context to explore the similarities and differences between countries. Qualitative research examining hand therapists’ clinical reasoning processes in choosing scar management interventions and outcome measures could provide a greater depth of understanding of how treatments are applied and how barriers to outcome measurement use may be overcome.

Respondents in this survey commonly learned scar massage from a colleague. In contrast, a practice survey of hand therapists by the American Society of Hand Therapists found that 95% learnt skills for scar management during formal training, prior to specializing in hand therapy or in the first 2 years of practice. 36 An international survey could also provide insights that could assist with the development of the AHTA training program. Finally, the common treatment regime used by the respondents of this survey could represent a potential scar massage protocol for investigating the effectiveness of scar massage in comparison to other scar treatments.

Conclusions

This web-based survey indicates that AHTA member survey respondents routinely use scar massage as part of their treatment for post-surgical patients. There was a strong similarity in practice methods across the survey respondents, and the identification of a relatively common regime amongst the sample may provide a tentative protocol for use in future studies of post-surgical scar massage. The findings also highlight that standardised scar outcome measures were not used by most respondents and that there is justification for further research to expand the evidence base for this area of clinical practice.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Scar massage as an intervention for post-surgical scars: A practice survey of Australian hand therapists by Helen C Scott, Luke S Robinson, Ted Brown in Hand Therapy

Author contributions: HS researched literature and conceived the study including the purpose-designed survey tool with guidance from LR and TB. HS completed the data collection and analysis. HS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: HS

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project ID 28091) approved the study.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

ORCID iDs

Helen C Scott https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1202-9620

Luke S Robinson https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4449-7357

References

- 1.Jones L. Scar management in hand therapy - is our practice evidence based? Br J Hand Ther 2005; 10(2): 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloemen MC, van der Veer WM, Ulrich MM, et al. Prevention and curative management of hypertrophic scar formation. Burns 2009; 35(4): 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deflorin C, Hohenauer E, Stoop R, et al. Physical management of scar tissue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 2020; 26(10): 854–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fundamentals of hand therapy. 2nd edition. St Louis: Mosby, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan SFM, Flowers CW. Therapy of the hand and upper extremity: rehabilitation protocols. Springer International Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller JL, Henderson JP, Landrieu KW, et al. The 2019 practice analysis of hand therapy and the use of orthoses by certified hand therapists. J Hand Ther 2022; 35(4): 628–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott HC, Stockdale C, Robinson A, et al. Is massage an effective intervention in the management of post-operative scarring? A scoping review. J Hand Ther 2022; 35(2): 186–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly CJ, Wilton J. The effect of massage to scars on active range of motion and skin mobility. Br J Hand Ther 2002; 7(1): 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saggini R, Saggini A, Spagnoli AM, et al. Etracorporeal shock wave therapy: An emerging treatment modality for retracting scars of the hands. Ultrasound Med Biol 2016; 42(1): 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koller T. Mechanosensitive aspects of cell biology in manual scar therapy for deep dermal defects. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21(6): 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDermid JC, Wojkowski S, Kargus C, et al. Hand therapist management of the lateral epicondylosis: A survey of expert opinion and practice patterns. J Hand Ther 2010; 23(1): 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004; 6(3): e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austraian Hand Therapy Association . Annual report 2020–2021. Australian Hand Therapy Association, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.SPSS statistics for Windows [computer program]. Armonk, NY: IBM, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart S. The use of standardised and non-standardised assessments in a social services setting: Implications for practice. Br J Occ Ther 1999; 62(9): 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan T, Smith J, Kermode J, et al. Rating the burn scar. J Burn Care Rehabil 1990; 11(3): 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004; 113(7): 1960–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotz T, Kurmis R. Reliability testing of the matching assessment using photographs of scars app. Wound Repair Regen 2020; 28(5): 676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joanna Briggs Institute . Recommended practice. Burns/surgical Scars: Massage 2022. JBI-RP-4367-4362. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasch MC, Greenberg S, Muenzen PM. Competencies in hand therapy. J Hand Ther 2003; 16(1): 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wackerhausen S. Collaboration, professional identity and reflection across boundaries. J Interprof Care 2009; 23(5): 455–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDermid JC. An introduction to evidence-based practice for hand therapists. J Hand Ther 2004; 17(2): 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, et al. What counts as evidence in evidence‐based practice? J Adv Nurs 2004; 47(1): 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valdes K. Overcoming the challenges to incorporate evidence-based medicine into clinical practice. J Hand Ther 2010; 23(3): 239–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valdes K, von der Heyde R. Attitudes and opinions of evidence-based practice among hand therapists: A survey study. J Hand Ther 2012; 25(3): 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan EAS, Murray J. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12(1): 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carrière ME, Kwa KAA, de Haas LEM, et al. Systematic review on the content of outcome measurement instruments on scar quality. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2019; 7(9): e2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colquhoun HL, Lamontagne M-E, Duncan EA, et al. A systematic review of interventions to increase the use of standardized outcome measures by rehabilitation professionals. Clin Rehab 2017; 31(3): 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyack Z, Wasiak J, Spinks A, et al. A guide to choosing a burn scar rating scale for clinical or research use. Burns 2013; 39(7): 1341–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaeger Pedersen T, Kaae Kristensen H. A critical discourse analysis of the attitudes of occupational therapists and physiotherapists towards the systematic use of standardised outcome measurement. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 38(16): 1592–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patten ML, Newhart M. Understanding research methods: an overview of the essentials. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ 2008; 33(3): 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Brien L, Robinson L, Parsons D, et al. Hand therapy role in return to work for patients with hand and upper limb conditions. J Hand Ther 2022; 35(2): 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sim G, Fleming J, Glasgow C. Mobilizing orthoses in the management of post-traumatic elbow contractures: A survey of Australian hand therapy practice. J Hand Ther 2021; 34(1): 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keller JL, Caro CM, Dimick MP, et al. Thirty years of hand therapy: The 2014 practice analysis. J Hand Ther 2016; 29(3): 222–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Scar massage as an intervention for post-surgical scars: A practice survey of Australian hand therapists by Helen C Scott, Luke S Robinson, Ted Brown in Hand Therapy