Abstract

Increased engagement of nurse practitioners (NPs) has been recommended as a way to address care delivery challenges in settings that struggle to attract physicians, such as primary care and rural areas. Nursing homes also face such physician shortages. We evaluated the role of state scope of practice regulations on NP practice in nursing homes in 2012–2019. Using linear probability models, we estimated the proportion of NP-delivered visits to patients in nursing homes as a function of state scope of practice regulations. Control variables included county demographic, socioeconomic, and health care workforce characteristics; state fixed effects; and year indicators. The proportion of nursing home visits conducted by NPs increased from 24% in 2012 to 42% in 2019. Expanded scope of practice regulation was associated with a greater proportion and total volume of nursing home visits conducted by NPs in counties with at least 1 NP visit. These relationships were concentrated among short-stay patients in urban counties. Removing scope of practice restrictions on NPs may address clinician shortages in nursing homes in urban areas where NPs already practice in nursing homes. However, improving access to advanced clinician care for long-term care residents and for patients in rural locations may require additional interventions and resources.

Keywords: nursing home, staffing, nurse practitioners, post-acute care, scope of practice

Introduction

Nursing homes experience difficulty recruiting and retaining clinicians, resulting in workforce shortages and inadequate staffing.1 These workforce challenges affect not only direct care staffing but also physicians and other advanced practice clinicians who provide medical services and expertise, including medication prescribing, diagnosis of new conditions, and management of acute and chronic symptoms. Increasing nurse practitioner (NP) engagement in care has been recommended as a way to address care delivery challenges in settings with clinician shortages, such as primary care and rural areas.2-6 State scope of practice regulations that subject NPs to burdensome requirements (eg, written practice and prescribing agreements with a physician) restrict the size of the NP workforce and have been associated with lower access to primary care in the community.7-9 However, little is known about the effect of state scope of practice regulations on the NP workforce in nursing homes.

The US NP workforce experienced significant growth over the past decade, with more than 250 000 employed NPs in 2022.10 In 2016, 1 in 4 primary care providers was an NP.11 However, states with restrictive scope of practice regulations observed slower growth in the number of NPs practicing in primary care settings,12 particularly in rural areas.9 The number of NPs who practice in nursing homes has also been on the rise,13-15 but how state scope of practice restrictions influence NP practice in nursing homes is unknown. Furthermore, there are 2 important differences between NP practice in primary care clinics vs nursing homes. First, “incident-to” billing, which permits primary care practices with NPs and physicians working together to bill at higher physician rates for visits conducted by NPs, is not allowed in nursing homes. Second, Medicare mandates that some nursing home visits, including comprehensive assessments on admission and at regular intervals for nursing home residents, are performed by physicians.16 This federal requirement may lead to NPs joining physician groups that practice in nursing homes rather than start independent practice. Nevertheless, the NP workforce in nursing homes experienced marked growth over the past decade despite these federal regulations that impact all facilities equally. Thus, a close examination of the role of state-level scope of practice restrictions is needed to evaluate their impact on the NP workforce in nursing homes.

To better understand the role of NP scope of practice restrictions on access to NP care in nursing homes, our objective was to measure the association between changes in state scope of practice regulations between 2012 and 2019 and NP visits to patients in nursing homes. We hypothesized that scope of practice regulations that restrict NP practice would limit NP practice in nursing homes.

Data and methods

Data sources and study sample

We used the Medicare Physician and Other Supplier Public Use Files, containing aggregate counts of all Part B Medicare fee-for-service claims by billing provider, to identify NPs, physicians, and physician assistants (PAs) who billed for visits to patients in nursing homes from 2012 through 2019. These files contained billing information for all clinicians, including visit type and place of service (short-stay skilled nursing facility or long-term-care nursing home), aggregated by year. We also used the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Area Health Resources File and the LTCFocus database17 to measure county-level resident demographics, socioeconomic characteristics, nursing home characteristics, and health care workforce characteristics. All variables were measured at the county-year level (n = 25 840). County-years without any nursing homes (n = 6884) or clinicians (n = 17), or with any missing data (n = 111), were excluded. Our final dataset included data for 18 828 county-years (Appendix Figure S1).

Study outcomes and other variables

To create our outcome variables, we measured the number and proportion of nursing home visits by physicians, NPs, and PAs for each county-year. To do so, we calculated the total number of nursing home visits by any individual clinician. Nursing home visits are excluded from “incident-to” billing and must be submitted under the performing clinician's national provider identifier. Thus, we were able to accurately identify all visits provided by NPs to patients in nursing homes. We summed the number of visits billed by each clinician type and calculated the percentage of nursing home visits provided by each clinician type in each county-year. We also separately calculated the proportion and volume of short-stay visits and long-term-care visits provided by each clinician type.

The NP scope of practice was measured using the classification developed by McMichael and Markowitz.18 The scope of practice measure was based on whether the state required a written collaborative agreement with a physician to practice and/or prescribe medications. States were categorized as having a restrictive scope of practice if collaborative agreements were required either for both practicing and prescribing or for prescribing only, whereas no collaborative agreements were required in “full scope of practice” states. Each county was characterized using the scope of practice regulations effective in the state for more than 6 months in a given year. During the study period, 9 states changed scope of practice regulations from restricted to full (Appendix Table S1).

We obtained information on nursing home characteristics, resident demographics, socioeconomic characteristics, and health care workforce characteristics for each county-year. Nursing home characteristics included number of beds, percentage of for-profit nursing homes, percentage of nursing homes that were part of a chain, percentage of nursing home stays covered by Medicaid, percentage of stays covered by Medicare, and average functional status of patients. Resident demographics included percentage older than 65 years, percentage Black, and highest educational level completed. Socioeconomic characteristics included percentage of population insured by Medicare, median household income, and unemployment rate. Health care workforce variables included the number of NPs per 100 000 residents, the number of primary care physicians per 100 000 residents, and the number of PAs per 100 000 residents. Each county was also categorized as large urban, small urban, or rural based on core-based statistical areas.19 Characteristics of counties in 2012 and 2019 by scope of practice regulation can be seen in Appendix Table S2.

Statistical analysis

All study variables are described using summary statistics. For our main analyses, we used a longitudinal, difference-in-differences design to examine the association between state adoption of full NP scope of practice and the provision of nursing home visits by NPs. Using linear probability models (unadjusted and adjusted), we estimated the change in the proportion of NP nursing home visits as a function of state scope of practice status interacted with year. Models included state and year fixed effects, and we controlled for the county-level characteristics listed above in the adjusted model. In a separate set of models (unadjusted and adjusted), we estimated the change in the volume of nursing home visits provided by NPs as a function of state scope of practice interacted with year. In addition to state and year fixed effects and county-level characteristics, we controlled for the volume of nursing home visits by physicians and PAs. In all analyses, standard errors were clustered at the state level.20 We also plotted the difference-in-difference estimators for each outcome relative to the time of the event (ie, lifting of the scope of practice restrictions) in event study diagrams to compare the pre-trend between the treatment and control groups.

We conducted 3 sets of additional analyses. First, we subgrouped nursing home visits into 2 categories by place of service (short-stay skilled nursing facility vs long-term-care nursing home). While most US nursing homes provide both types of services, they represent 2 distinct patient populations. Short-stay patients receive post-acute care such as skilled nursing and/or physical therapy with the goal of functional recovery after hospitalization. Long-term-care patients require 24 hours per day custodial care in the nursing home. Second, we stratified our sample by rurality (rural vs urban) to examine whether there was any heterogeneity in outcomes. Third, we estimated the models on the subsample of counties after excluding the 16 states with full scope of practice authority for the entire study period (see Appendix Table S1 for the list of states).

Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The study used publicly available datasets and therefore was exempt from human subjects research review by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, although we used a difference-in-differences approach using longitudinal data, we cannot claim to measure causal relationships. There are likely organizational and individual factors affecting NP practice in nursing homes that we could not observe. Moreover, our observational study design limited our ability to capture medical care provided but not billed for, such as interdisciplinary care meetings, care coordination services, and communication with caregivers. Finally, we measured visits to Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries (including dual beneficiaries covered by Medicaid), the most prevalent payer for nursing home care, but not for beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage, stand-alone Medicaid, and commercial insurance. Our findings may not be generalizable to those populations.

Results

Trends in nursing home visits by provider type

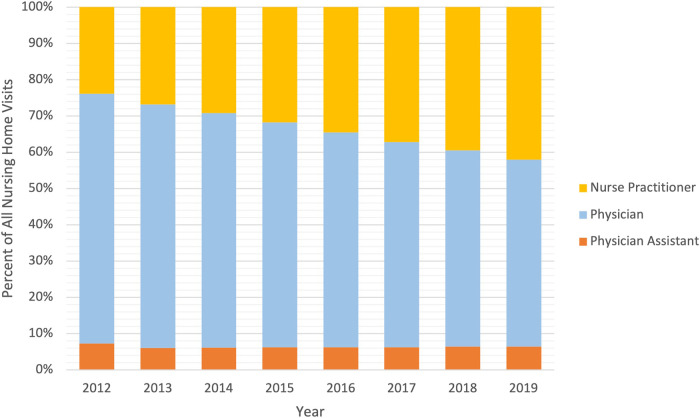

From 2012 to 2019, the proportion of all nursing home visits by NPs increased from 24% to 42% (Figure 1). In each year of the study period, physician-billed visits constituted the largest proportion of all nursing home visits, but the proportion of these visits decreased from 69% to 51%. The proportion of nursing home visits by PAs remained relatively stable (7% in 2012 and 6% in 2019). Trends were similar when we categorized our sample by long-term-care and short-stay visits and, by 2019, NPs provided almost half (47%) of all long-term-care visits and 40% of all short-stay visits (Appendix Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Proportion of nursing home visits by nurse practitioners, physicians, and physician assistants, 2012–2019. The percentage of nursing home visits by provider type was calculated as the fraction of all nursing home visits by all providers in that category divided by the total number of nursing home visits during the year. Nursing home visits included visits to short-stay and long-term-care patients. Source: Authors' analysis of the Medicare Provider Public Use Files.

The event study diagrams are presented in Appendix Figure S3. There was no significant pre-trend for the proportion of NP visits. The difference-in-differences estimates for the volume of NP visits were statistically significantly different from zero in years 7 and 8 prior to the event (ie, lifting of scope of practice restrictions). However, the trend dissipated in the later pre-period (1–6 years prior to the lifting of scope of practice restrictions).

Association of adoption of full NP scope of practice with outcomes

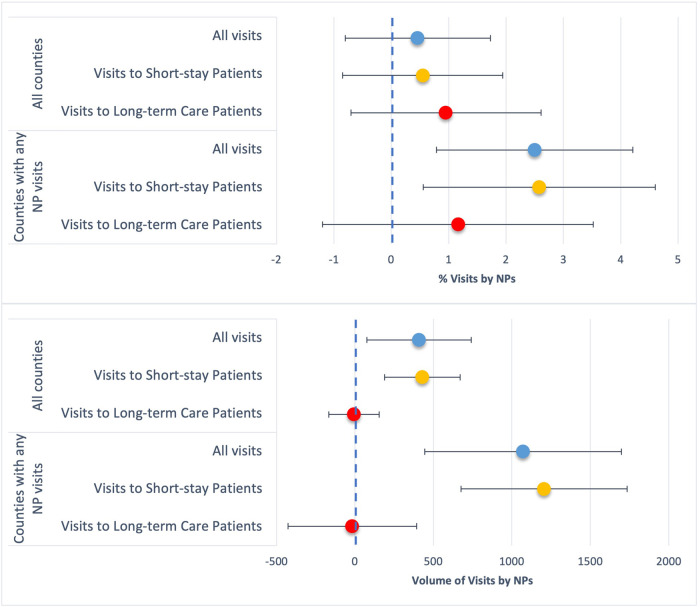

Figure 2 displays the adjusted models of the association of state adoption of full NP scope of practice with changes in the proportion and volume of nursing home visits by NPs. Across all counties (n = 2651), the change in the proportion of nursing home visits by NPs was not statistically significant (top panel of Figure 2). However, in counties with at least 1 NP visit (n = 1978), adopting full NP scope of practice was associated with a 2.5-percentage-point increase in the proportion of all nursing home visits by NPs (95% CI: 0.8–4.2), a 7.8% increase relative to the sample mean. These findings were concentrated among short-stay visits (2.6 percentage points; 95% CI: 0.6–4.6) vs long-term-care visits (1.2 percentage points; 95% CI: −1.2, 3.5), a 7.9% increase relative to the sample mean. Full unadjusted and adjusted models can be seen in Appendix Table S3.

Figure 2.

Association of adopting full scope of practice with the change in the proportion and volume of nursing home visits by nurse practitioners. The results are presented as percentage points for the proportion of nursing home visits by nurse practitioners and as counts for the volume of nursing home visits by nurse practitioners. The results are adjusted for county demographic, socioeconomic, nursing home, and health care workforce characteristics. The estimates for the volume of nurse practitioner visits are from models that also included the total number of nursing home visits by physicians and PAs. ***P < .01, **P < .05, *P < .1. Source: Authors' analysis of the Medicare Provider Public Use Files, Brown University LTCfocus database, and the HRSA Area Health Resources Files. Abbreviations: HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

On average, the volume of nursing home visits by NPs increased by 409 (95% CI: 77–741) visits in all counties after a state adopted full NP scope of practice and, again, results were driven by short-stay visits (430; 95% CI: 189–670; bottom panel of Figure 2). We observed a similar pattern in counties with at least 1 NP visit (n = 1978), with increases in the volume of nursing home visits by NPs for all visits (1072; 95% CI: 445–1699) and short-stay visits (1205; 95% CI: 676–1735), a 20.7% and 32.3% increase, respectively, relative to the sample means. Full unadjusted and adjusted models can be seen in Appendix Table S4.

Urban vs rural counties

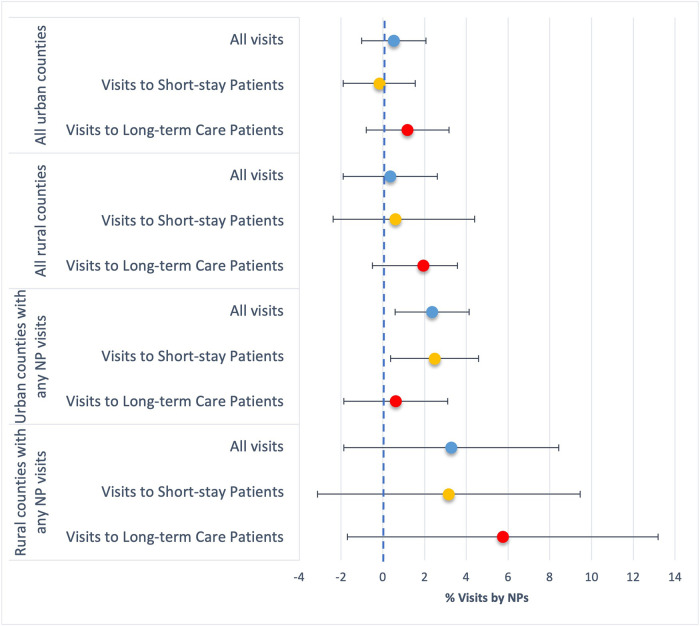

Next, we stratified our sample by county rural status to examine outcomes. In urban counties with at least 1 NP visit (Figure 3), adjusted models revealed a 2.4-percentage-point increase (95% CI: 0.6–4.1) in the proportion of nursing home visits by NPs after state adoption of full scope of practice and, similar to our main analyses, a 2.5-percentage-point increase (95% CI: 0.4–4.6) for short-stay visits. Changes in the outcome were not significant for rural counties. Full unadjusted and adjusted models can be seen in Appendix Table S5.

Figure 3.

Association of adopting full scope of practice with the change in the proportion of nursing home visits by nurse practitioners for urban and rural counties. The results are presented in percentage points of visits by nurse practitioners, adjusted for county demographic, socioeconomic, nursing home, and health care workforce characteristics. ***P < .01, **P < .05, *P <0.1. Source: Authors' analysis of the Medicare Provider Public Use Files, Brown University LTCfocus database, and the HRSA Area Health Resources Files. Abbreviations: HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; NP, nurse practitioner.

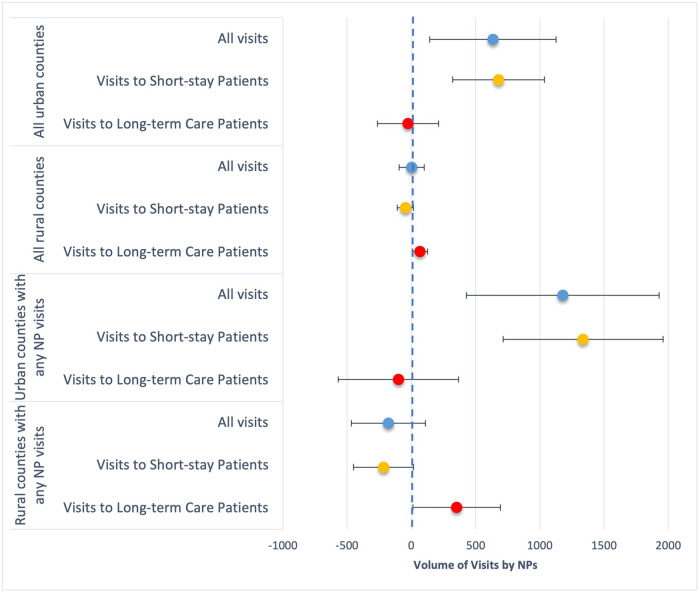

For changes in the volume of nursing home visits by NPs, state adoption of full scope of practice was mostly associated with significant changes in urban counties (Figure 4). In all urban counties (n = 1672), the volume of all nursing home visits by NPs increased by 634 (95% CI: 142–1126) and for short-stay visits by 677 (95% CI: 320–1034), a 14.9% and 25.5% increase, respectively, compared to the sample means (Appendix Table S6). In urban counties with at least 1 NP visit, the volume of all visits by NPs increased by 1178 (95% CI: 428–1928), an 18.6% increase, and by 1336 (95% CI: 714–1959) for short-stay visits, a 29.8% increase. Results for rural counties were generally not significant, except for counties with at least 1 NP visit. Unlike our results that showed overall greater provision of care by NPs among short-stay visits, we found an increase in the volume of long-term-care visits by NPs in rural counties with at least 1 NP visit (351; 95% CI: 10–692).

Figure 4.

Association of adopting full scope of practice with the change in the volume of nursing home visits by nurse practitioners for urban and rural counties. The results represent the number of visits by nurse practitioners, adjusted for county demographic, socioeconomic, nursing home, health care workforce characteristics, and the total number of nursing home visits by physicians and PAs. ***P < .01, **P < .05, *P < .1. Source: Authors' analysis of the Medicare Provider Public Use Files, Brown University LTCfocus database, and the HRSA Area Health Resources Files. Abbreviations: HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

In our sensitivity analysis of the subsample of counties in states that either lifted scope of practice restrictions during the study period or had restricted scope of practice (n = 2221), the change in the proportion of nursing home visits by NPs was not statistically significant (top panel of Appendix Table S7). In counties with at least 1 NP visit (n = 1645), adopting full NP scope of practice was associated with a 2.7-percentage-point increase in the proportion of all nursing home visits by NPs (95% CI: 0.03–5.0) and a 3.3-percentage-point increase in short-stay visits (95% CI: 0.6–5.9) (lower panel of Appendix Table S7), consistent with our main results. For the volume of NP visits outcome, we observed similar effect sizes as in our main results, but the estimates from the analysis of the subsample of counties were not statistically significant (Appendix Table S8).

Discussion

This analysis of 2012–2019 Medicare fee-for-service claims measured robust growth in the proportion of nursing home visits provided by NPs. By 2019, NPs provided nearly half of all long-term-care visits. Full NP scope of practice was associated with a greater increase in the proportion of visits conducted by NPs only in counties with any NP visits at baseline. Moreover, full NP scope of practice was associated with a greater total volume of nursing home visits by NPs for short-stay patients and in urban counties. There was a trend toward an increase in the proportion and volume of nursing home visits by NPs in rural counties with NP visits at baseline that adopted full NP scope of practice, but these results were nonsignificant. Overall, these findings indicate that full NP scope of practice can improve access to NP care, particularly in counties where NPs already practice in nursing homes.

Nurse practitioners have advanced medical training to diagnose and treat illnesses and have the ability to order and interpret diagnostic tests and prescribe medications. While prior literature on NP practice has primarily focused on primary care and rural settings, NP-based practice models are especially relevant for nursing homes, which house over 1.3 million Americans1 and experience long-standing physician shortages. Primary care provided by NPs has been associated with good health outcomes, including high medication adherence,21 lower costs,22-24 and guideline-consistent care.22 Additionally, there is no evidence that restrictive scope of practice laws improve care quality or outcomes in primary care settings.25-27 Moreover, NPs in primary care settings are more likely to provide services to disadvantaged Medicare beneficiaries and to accept Medicaid compared with physicians.28,29 As nursing homes struggle to attract and employ providers, removing restrictive regulations that limit NP practice and prescriptive authority may increase nursing home residents' access to care and allow for more efficient use of the NP workforce across practice settings.

The association between full scope of practice and NP-delivered care in nursing homes was stronger in counties with NPs practicing in nursing homes at baseline. Removing scope of practice restrictions alone may not be enough to attract NPs to practice in nursing homes in areas where such practice is novel. Some of the barriers to nursing home practice reported by physicians—malpractice risk, low reimbursement, and inadequate training—may be relevant to NPs new to nursing home practice.30-33 Furthermore, Medicare mandates that some nursing home visits be conducted by physicians. For example, Medicare specifies the inclusion of a physician on the interdisciplinary care team that develops an individualized treatment plan for short-stay patients and physicians are mandated to perform the initial face-to-face “admission” visit.16 However, nearly 20% of Medicare beneficiaries newly admitted to a nursing home did not receive a physician visit in the first 5 days of their stay, with considerable variation in the timing of first visit across nursing homes.34 As NP visits to nursing home patients increase, eliminating restrictions on the type of provider who can conduct the initial visit and increasing reimbursement for timely visits may improve access to NP care after nursing home admission by enabling nursing homes to directly partner with NPs to deliver care.

Considering the additional challenges faced by nursing home clinicians, states that eliminate NP scope of practice restrictions may theoretically worsen access to NP care in nursing homes if NPs have greater employment opportunities in non–nursing home settings. We did not observe evidence of this, with full scope of practice being associated with an increase, albeit nonsignificant, in the proportion of nursing home visits by NPs in all settings. Nevertheless, regulatory changes to NP practice in other settings may have an effect on the NP workforce in nursing homes. For instance, eliminating “incident-to” billing in primary care settings, estimated to result in considerable cost savings to Medicare,35 may influence the relationship between scope of practice restrictions and NP practice in nursing homes.

We observed considerable differences in the relationship between lifting scope of practice restrictions and NP practice in nursing homes for rural vs urban counties. For rural counties, there was a trend toward a greater proportion of visits conducted by NPs for long-term-care residents, but those findings did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, for urban counties, full scope of practice was associated with an increase in the proportion and volume of visits by NPs to short-stay patients but not to long-term-care residents. These findings may reflect differences between urban and rural facilities in the division of labor between NPs and physicians, patient case mix, and practice organization of the different clinician types.36

Pilot studies of NP-based care in nursing homes reported lower hospitalization rates,37,38 emergency room visits, costs to Medicare,39,40 and better quality of life41 for long-term-care residents. Although those studies included physicians as part of the care team and were conducted in the context of managed care organizations, those findings are consistent with the large body of evidence supporting NP practice for older adults. In other settings, adoption of full scope of practice increased the capacity of NPs and physicians to provide primary care.42 Moreover, because Medicare regulations on who can perform certain patient assessments impact all facilities equally and limit NPs' ability to practice in the nursing home independently of physicians, one might expect that the federal policy effect would obscure any effects of removal of scope of practice restrictions at the state level. Our findings of increased volume of visits after the removal of scope of practice restrictions despite the federal-level requirements indicate that both state and federal policies may be outdated and require revision. Taken together, our findings suggest that adoption of full NP scope of practice improves access to medical care in nursing homes as well, particularly in urban areas where NPs already practice in nursing homes. However, improving access to NP care for long-term-care residents and for patients in rural locations may require additional interventions and resources.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Kira L Ryskina, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States; Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States.

Junning Liang, Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States.

Ashley Z Ritter, NewCourtland, Philadelphia, PA 19119, United States; School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States.

Joanne Spetz, School of Medicine, Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94158, United States.

Hilary Barnes, Widener University School of Nursing, Chester, PA 19013, United States.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Health Affairs Scholar online.

Funding

Dr. Ryskina's work on this study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Career Development Award (K08-AG052572) and NIA R01AG066841. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging.

Notes

- 1.Committee on the Quality of Care in Nursing Homes . The National Imperative to Improve Nursing Home Quality: Honoring our Commitment to Residents, Families, and Staff. The National Academies Press; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue Y, Smith JA, Spetz J. Primary care nurse practitioners and physicians in low-income and rural areas, 2010-2016. JAMA. 2019;321(1):102–105. 10.1001/jama.2018.17944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue Y, Ye Z, Brewer C, Spetz J. Impact of state nurse practitioner scope-of-practice regulation on health care delivery: systematic review. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(1):71–85. 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traczynski J, Udalova V. Nurse practitioner independence, health care utilization, and health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2018;58:90–109. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maier CB, Barnes H, Aiken LH, Busse R. Descriptive, cross-country analysis of the nurse practitioner workforce in six countries: size, growth, physician substitution potential. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e011901. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon D, Gary F. Full practice authority for nurse practitioners. Nurs Adm Q. 2017;41(1):86–93. 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo YF, Loresto FL Jr, Rounds LR, Goodwin JS. States with the least restrictive regulations experienced the largest increase in patients seen by nurse practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1236–1243. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalist DE, Spurr SJ. The effect of state laws on the supply of advanced practice nurses. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2004;4(4):271–281. 10.1023/B:IHFE.0000043758.12051.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graves JA, Mishra P, Dittus RS, Parikh R, Perloff J, Buerhaus PI. Role of geography and nurse practitioner scope-of-practice in efforts to expand primary care system capacity: health reform and the primary care workforce. Med Care. 2016;54(1):81–89. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Occupational employment and wages NP, May 2022. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291171.htm

- 11.Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, Martsolf G. Rural and nonrural primary care physician practices increasingly rely on nurse practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):908–914. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reagan PB, Salsberry PJ. The effects of state-level scope-of-practice regulations on the number and growth of nurse practitioners. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61(6):392–399. 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryskina KL, Polsky D, Werner RM. Physicians and advanced practitioners specializing in nursing home care, 2012-2015. JAMA. 2017;318(20):2040–2042. 10.1001/jama.2017.13378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Intrator O, Feng Z, Mor V, Gifford D, Bourbonniere M, Zinn J. The employment of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in U.S. nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2005;45(4):486–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Intrator O, Miller EA, Gadbois E, Acquah JK, Makineni R, Tyler D. Trends in nurse practitioner and physician assistant practice in nursing homes, 2000-2010. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1772–1786. 10.1111/1475-6773.12410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Medicare required SNF PPS assessments. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/SNF-PPS/SNFAssessHTML022817f.html

- 17.LTCFocus Public Use Data sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG027296) through a cooperative agreement with the Brown University School of Public Health. Accessed February 17, 2022. www.ltcfocus.org

- 18.McMichael BJ, Markowitz S. Toward a uniform classification of nurse practitioner scope of practice laws. Med Care Res Rev. 2022;80(4):444–454. 10.1177/10775587221126777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Agriculture . What is rural? Washington (DC). 2023. Accessed September 22, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/what-is-rural/

- 20.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48(4):817–830. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muench U, Whaley C, Coffman J, Spetz J. Scope-of-practice for nurse practitioners and adherence to medications for chronic illness in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):478–486. 10.1007/s11606-020-05963-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DesRoches CM, Clarke S, Perloff J, O'Reilly-Jacob M, Buerhaus P. The quality of primary care provided by nurse practitioners to vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65(6):679–688. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perloff J, DesRoches CM, Buerhaus P. Comparing the cost of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries assigned to primary care nurse practitioners and physicians. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4):1407–1423. 10.1111/1475-6773.12425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hooker RS, Muchow AN. Modifying state laws for nurse practitioners and physician assistants can reduce cost of medical services. Nurs Econ. 2015;33(2):88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver GM, Pennington L, Revelle S, Rantz M. Impact of nurse practitioners on health outcomes of Medicare and Medicaid patients. Nurs Outlook. 2014;62(6):440–447. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perloff J, Clarke S, DesRoches CM, O’Reilly-Jacob M, Buerhaus P. Association of state-level restrictions in nurse practitioner scope of practice with the quality of primary care provided to Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care Res Rev. 2019;76(5):597–626. 10.1177/1077558717732402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurtzman ET, Barnow BS, Johnson JE, Simmens SJ, Infeld DL, Mullan F. Does the regulatory environment affect nurse practitioners' patterns of practice or quality of care in health centers? Health Serv Res. 2017;52(S1):437–458. 10.1111/1475-6773.12643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DesRoches CM, Gaudet J, Perloff J, Donelan K, Iezzoni LI, Buerhaus P. Using Medicare data to assess nurse practitioner-provided care. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61(6):400–407. 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes H, Maier CB, Altares Sarik D, Germack HD, Aiken LH, McHugh MD. Effects of regulation and payment policies on nurse practitioners' clinical practices. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(4):431–451. 10.1177/1077558716649109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz PR, Karuza J, Kolassa J, Hutson A. Medical practice with nursing home residents: results from the National Physician Professional Activities Census. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(8):911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kane RS. Factors affecting physician participation in nursing home care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(9):1000–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bern-Klug M, Buenaver M, Skirchak D, Tunget C. “I get to spend time with my patients”: nursing home physicians discuss their role. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(3):145–151. 10.1097/01.JAM.0000061473.13422.CC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy C, Palat SI, Kramer AM. Physician practice patterns in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(9):558–567. 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryskina KL, Yuan Y, Teng S, Burke R. Assessing first visits by physicians to Medicare patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):528–536. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel SY, Huskamp HA, Frakt AB, et al. . Frequency of indirect billing to Medicare for nurse practitioner and physician assistant office visits. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(6):805–813. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritter AZ, Bowles KH, O'Sullivan AL, Carthon MB, Fairman JA. A policy analysis of legally required supervision of nurse practitioners and other health professionals. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66(6):551–559. 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Intrator O, Castle NG, Mor V. Facility characteristics associated with hospitalization of nursing home residents: results of a national study. Med Care. 1999;37(3):228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fama T, Fox PD. Efforts to improve primary care delivery to nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(5):627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rantz MJ, Birtley NM, Flesner M, Crecelius C, Murray C. Call to action: APRNs in U.S. nursing homes to improve care and reduce costs. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65(6):689–696. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovink MH, Persoon A, van Vught A, Schoonhoven L, Koopmans R, Laurant MGH. Substituting physicians with nurse practitioners, physician assistants or nurses in nursing homes: protocol for a realist evaluation case study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015134. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arendts G, Deans P, O'Brien K, et al. . A clinical trial of nurse practitioner care in residential aged care facilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;77:129–132. 10.1016/j.archger.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kandrack R, Barnes H, Martsolf GR. Nurse practitioner scope of practice regulations and nurse practitioner supply. Med Care Res Rev. 2021;78(3):208–217. 10.1177/1077558719888424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.