Abstract

Objective:

To determine if accurate documentation of bladder cancer risk was associated with a clinician surveillance recommendation that is concordant with AUA guidelines among patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

Methods:

We prospectively collected data from cystoscopy encounter notes from four Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) sites to ascertain whether they included accurate documentation of bladder cancer risk and a recommendation for a guideline-concordant surveillance interval. Accurate documentation was a clinician recorded risk classification matching a gold standard assigned by the research team. Clinician recommendations were guideline-concordant if the clinician recorded a surveillance interval that was in line with the AUA guideline.

Results:

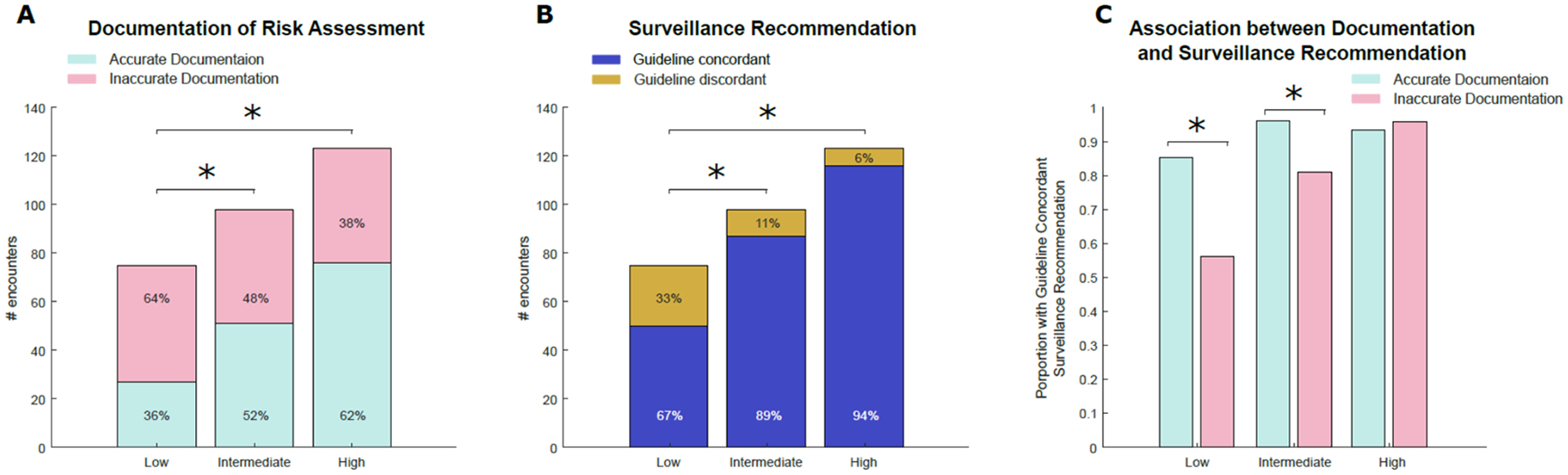

Among 296 encounters, 75 were for low-, 98 for intermediate-, and 123 for high-risk NMIBC. 52% of encounters had accurate documentation of NMIBC risk. Accurate documentation of risk was less common among encounters for low-risk bladder cancer (36% vs 52% for intermediate- and 62% for high-risk, p<0.05). Guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations were also less common in patients with low-risk bladder cancer (67% vs 89% for intermediate- and 94% for high-risk, p<0.05). Accurate documentation was associated with a 29% and 15% increase in guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations for low- and intermediate-risk disease, respectively (p<0.05).

Conclusion:

Accurate risk documentation was associated with more guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations among low- and intermediate-risk patients. Implementation strategies facilitating assessment and documentation of risk may be useful to reduce overuse of surveillance in this group and to prevent unnecessary cost, anxiety, and procedural harms.

Keywords: bladder cancer, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, surveillance, health systems, electronic medical record

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common visceral malignancy in in the United States. Approximately 75% of patients are diagnosed with early stage, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) (1). These patients are at varying risk for recurrence and progression to muscle-invasive disease (2). Given these differences in risk, many organizations recommend to align surveillance regimens (cystoscopy, cytology, imaging) with cancer risk. For example, the AUA/SUO NMIBC Joint Guideline recommends surveillance cystoscopy every 3 months in the first 2 years for high risk NMIBC compared to annual surveillance for low-risk NMIBC (3). Despite these consensus recommendations, our group and others have demonstrated that NMIBC patients often do not receive risk-aligned surveillance (4–6).

There are many determinants affecting the practice of risk-aligned bladder cancer surveillance, primarily at the provider and facility level (7, 8). It is also possible that accurate documentation of bladder cancer risk, which is based on pathologic details such as grade, stage, size, or multi-focality, influences adherence to risk-aligned surveillance. Clinicians may find it easier to recommend guideline recommended surveillance when risk levels are accurately documented.

Our objective was to determine if accurate documentation of bladder cancer risk was associated with a clinician surveillance recommendation concordant with AUA guidelines. We hypothesized that low-risk patients were often not receiving risk-aligned care and that accurate documentation of risk would be associated with a higher likelihood of a risk-aligned surveillance recommendation.

Methods

Data Source

Encounter-level data on surveillance cystoscopy procedures were collected from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. These procedures were performed in four participating VA sites in the United States: Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; Indianapolis, IN; and Nashville, TN. The data collection was one component of an ongoing pilot study that aims to implement strategies to improve guideline-concordant surveillance for NMIBC patients in these four VA sites. Encounters included occurred between 03/01/2021, when data collection was launched per the study protocol, and 04/01/2022, which corresponds to the time period prior to implementation of improvement approaches at the participating sites. A total of 619 encounters were abstracted. Encounters were excluded if there was no history of NMIBC (n=102), or any exclusion criteria were met (n=83). Exclusion criteria included history of cystectomy or partial cystectomy, bladder radiation, urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis or ureter, muscle invasion (into muscularis propria or smooth bladder muscle), or tumor in penile urethra. In addition, we excluded encounters for the following reasons: short-term repeat cystoscopy procedures for a specific cause (e.g., hematuria after recent cystoscopy, n=5), missing pathologic information (n=7), and missing surveillance recommendation (n=46). Finally, encounters were excluded if tumor recurrence was found during the surveillance cystoscopy necessitating resection (n=73), or if a gold standard risk group could not be assigned (e.g., initial diagnosis of high-risk NMIBC but recurrence of low-grade NMIBC, n=7). After these exclusions, 296 encounters remained for analyses. 51 of these encounters were repeated encounters (for returning patients) with 245 unique patients included in this analysis. For each encounter, we collected the patient’s age, gender, smoking status (as described by the VA Centralized Interactive Phenomics Resource (CIPHER)) (9), body mass index (BMI) (closest prior to the date of the encounter), race, Charlson comorbidity index using data from the 1 year before the date of the surveillance encounter, and rurality of the zip code of the patient’s residence based on rural-urban commuting area codes (RUCA). The VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) was the data source for all these variables.

Data abstraction

The data was abstracted by at least one of three trained research coordinators. The training involved a standard operating procedure that was developed for the abstractors to follow, group abstraction sessions to train new team members, and an ongoing review for at least the first 50 encounters abstracted by any new team member to ensure the accuracy of the collected data. The data was entered into REDCap, where an algorithm was programmed to assign a gold standard risk-assessment based on the AUA NMIBC guideline (Figure in Supplementary Material) (10). This gold standard was then confirmed by the abstractor. Tumor size and multi-focality were identified from surgical reports. Recurrences were determined based on reviewing any prior surgical pathology reports. Finally, the surveillance recommendation was collected from the encounter note from the surveillance cystoscopy procedure that corresponded to the abstracted encounter. These data elements were collected via chart abstraction using the Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV) application.

Outcomes

Accurate documentation of risk was defined as a bladder cancer risk category documented in the cystoscopy encounter note that was in line with the gold standard risk assessment (low-, intermediate-, or high-risk). Inaccurate documentation of risk was either a risk assessment not in line with the gold standard or absence of a documented risk assessment. The recommendation for a surveillance interval was categorized by comparing the clinician’s recommended surveillance plan to a gold standard guideline-concordant surveillance interval. The gold standard interval was based on the AUA NMIBC guideline accounting for risk assessment and the time since each patient’s last positive bladder cancer pathology report. Clinician recommendations for surveillance intervals were guideline concordant if the clinician recorded a surveillance interval that was in line with the gold standard interval. In addition, if a clinician chose a different surveillance interval and documented a rationale for this decision or a discussion of shared decision making, this was also categorized as guideline concordant.

Analysis

For continuous variables such as age and BMI, we used ANOVA (ANalysis Of VAriance) to investigate the difference in mean age across disease risk levels. For categorical variables such as age category (age>80), gender, smoking status, race, comorbidities, residence, stage, and grade, we used chi-square tests of independence to investigate the association of each one of these variables with disease risk levels. We calculated the proportion of encounters with accurate versus inaccurate documentation of risk and with guideline concordant versus discordant surveillance recommendations, stratified by disease risk levels and pathologic details. In addition, we used chi-square tests to investigate the association between presence versus absence of accurate documentation of risk and presence versus absences of a guideline-concordant surveillance recommendation, stratified by risk level. Risk ratios were calculated to determine the effect of accurate documentation on surveillance recommendation between risk levels. Statistical significance was defined as p value < 0.05. The data analysis was performed using MATLAB R2017B (MathWorks) package and statistical tests were done in R 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Demographics

Of 296 encounters, 75 (25%), 98 (33%), and 123 (42%) were low-, intermediate-, and high-risk, respectively. Low grade Ta made up the vast majority of low-risk encounters, while low grade Ta with recurrence within 1 year made up the largest proportion of intermediate-risk encounters. Carcinoma in situ represented more than a third of high-risk encounters. High-risk patients were more likely to be of older age (74 vs. 72 years old, p=0.002). Male sex, tobacco use, BMI, race, co-morbidity, and residence were similar between risk groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of 296 encounters of patients with NMIBC stratified by risk level.

| Category | Total (n = 296) | Low Risk (n = 75) | Intermediate Risk (n = 98) | High Risk (n = 123) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 73 [41 – 89] | 72 [41 – 88] | 72 [42 – 89] | 74 [46 – 88] | 0.002 |

| Male sex (N, %) | 292 (98.6%) | 73 (97.3%) | 96 (98%) | 123 (100%) | 0.222 |

| Tobacco Use | 0.144 | ||||

| Current Smoker | 54 (18.2%) | 13 (17.3%) | 23 (23.5%) | 18 (14.6%) | |

| Former Smoker | 153 (51.7%) | 33 (44%) | 52 (53.1%) | 68 (55.3%) | |

| Never Smoked | 89 (30.1%) | 29 (38.7%) | 23 (23.5%) | 37 (30.1%) | |

| BMI (median, range) | 28.9 [17.4 – 45.9] | 29.4 [17.8 – 45.9] | 28.3 [17.4 – 42.2] | 28.4 [17.7 – 43.6] | 0.529 |

| Race | 0.075 | ||||

| White | 209 (70.6%) | 56 (74.7%) | 61 (62.2%) | 92 (74.8%) | |

| Black or African American | 75 (25.3%) | 19 (25.3%) | 31 (31.6%) | 25 (20.3%) | |

| Other | 12 (4.1%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (6.1%) | 6 (4.9%) | |

| Comorbidity, N (%) | 0.189 | ||||

| 0 | 6 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 1 | 7 (2.4%) | 2 (2.7%) | 3 (3.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| 2 | 72 (24.3%) | 20 (26.7%) | 28 (28.6%) | 24 (19.5%) | |

| >=3 | 211 (71.3%) | 50 (66.7%) | 64 (65.3%) | 97 (78.9%) | |

| Residence | 0.779 | ||||

| Urban | 267 (90.2%) | 69 (92%) | 87 (88.8%) | 111 (90.2%) | |

| Non-Urban | 29 (9.8%) | 6 (8%) | 11 (11.2%) | 12 (9.8%) | |

| Stage | # | ||||

| PUNLMP (N, %) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ta (N, %) | 218 (73.6%) | 74 (98.7%) | 98 (100%) | 46 (37.4%) | |

| T1 (N, %) | 33 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 33 (26.8%) | |

| CIS (N, %) | 44 (14.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 44 (35.8%) | |

| Grade | # | ||||

| Low (N, %) | 162 (54.7%) | 75 (100%) | 87 (88.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| High (N, %) | 90 (30.4%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (11.2%) | 79 (64.2%) |

p-value not calculated as these categories were used to define risk. PUNLMP = Papillary Urothelial Neoplasm of Low Malignant Potential; CIS = Carcinoma in Situ.

Accurate Documentation

Accurate documentation of risk was present in 154 (52%) of the encounters. Among the 142 (48%) reports with inaccurate documentation, 36 (25%) were not in line with the gold standard and 106 (75%) had no documented risk assessment. Low-risk encounters were least likely to be accurately documented – 36% compared to 52% and 62% in intermediate- and high-risk encounters, respectively (p=0.036 for low- vs. intermediate-risk and p<0.001 for low vs. high-risk, Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Number of encounters stratified by gold standard NMIBC risk with A) accurate documentation of NMIBC risk and B) guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations. C) association of accurate documentation with guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations. * indicates p<0.05

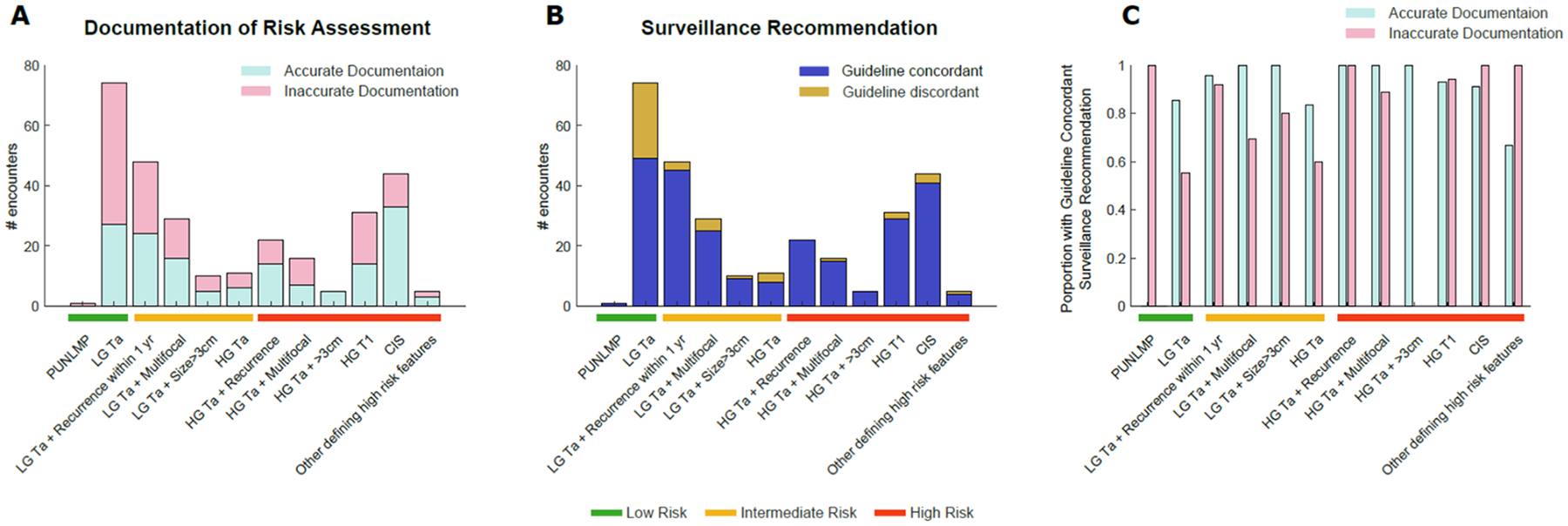

When stratified by pathologic details, low grade Ta disease with recurrence within 1 year made up the largest proportion of inaccurate documentation among intermediate-risk encounters (Figure 2A). These cases were frequently classified as low-risk, although they fall into the AUA intermediate risk category. HG T1 made up the largest proportion of inaccurate documentation among high-risk encounters with 17 of 33 encounters (52%) having inaccurate documentation (Figure 2A). HG T1 cancers often had inaccurate documentation because their risk-category was not documented, with 16 of the 17 encounters (94%) having missing documentation.

Figure 2.

Number of encounters stratified by gold standard NMIBC risk based on pathologic details with A) accurate documentation of NMIBC risk and B) guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations. C) association of accurate documentation with guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations. Note that there was only one PUNLMP encounter, which had inaccurate documentation but a guideline concordant surveillance interval.

Guideline-concordant Surveillance Recommendation

Overall, guideline-concordant surveillance was recommended in 253 encounters (86%). Low risk encounters were least likely to receive a guideline-concordant surveillance recommendation – 67% compared to 89% and 94% in intermediate- and high-risk encounters, respectively (p<0.001 for low vs. intermediate risk and p<0.001 for low vs. high risk, Figure 1B).

Association of Accurate Documentation with Guideline-concordant Surveillance Recommendations

Among the 154 encounters with accurate documentation of risk, 143 (92.8%) had a guideline-concordant surveillance recommendation. Conversely, only 110 (77.5%) of the 142 encounters with inaccurate documentation had a guideline-concordant surveillance recommendation (p<0.001). Accurate documentation was associated with a greater likelihood of guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations in the low-risk (RR 1.52, 85.2% vs. 56.2%, p=0.011) and intermediate-risk groups (RR 1.19, 96.1% vs. 80.9%, p=0.017). This association was not observed in high-risk disease (RR 0.98, 93.4% vs. 95.7%, p=0.589, Figure 1C).

Discussion

We examined prospectively collected data from cystoscopy encounters within the VA to determine the association between accurate documentation of bladder cancer risk and guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations based on the joint SUO/AUA NMIBC Guideline (3). We found that accurate documentation of risk level was widely absent in over half of all encounters. This was most prominent in low- and intermediate-risk encounters. While guideline-concordant surveillance was excellent in high-risk encounters (94%) we found it to be only 67% in low-risk encounters. Furthermore, we show that accurate documentation in low- and intermediate-risk encounters was associated with guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations. This suggests that a clinician is more likely to recommend guideline concordant surveillance after thinking about and documenting the NMIBC risk category.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has 1) identified a baseline rate of bladder cancer risk documentation and 2) found an association between accurate documentation and guideline concurrent surveillance recommendations. Our findings are consistent with previous work indicating that although there are clear guidelines, risk-aligned surveillance does not regularly occur (3–4, 11). This can be observed in other malignancies as well (12–13). Our findings are also consistent with previous work from our group demonstrating that when stratified by risk level, low-risk disease is most often surveyed inappropriately (5). We have previously shown that patient factors do not significantly impact risk-aligned surveillance, however provider knowledge as well as lack of routines and resources may be barriers to risk-aligned surveillance (7–8). For example, VA-wide initiatives to improve access and productivity have also led to shortened appointment times, which may make it harder for providers to accurately assign risk and recommend a guideline-concordant surveillance interval. In this study, we have shown that accurate provider documentation of risk level is associated with a higher likelihood of risk-aligned surveillance in low- and intermediate-risk groups. Our results suggest that a focus upon accurate documentation may provide an opportunity to standardize care and improve guideline-concordant surveillance.

We also found that despite poor overall documentation of risk, guideline-concordant care was recommended in about 85% of encounters. However, when stratified by risk level only approximately 65% of low-risk encounters had a recommendation that was guideline concordant. While it is reassuring that the strong majority of surveillance recommendations for intermediate- and high-risk disease are guideline-concordant (as they have an inherently higher risk for progression and recurrence), patients with low-risk disease who are at low risk for recurrence and progression are undergoing an increased number of surveillance cystoscopies. While office cystoscopies are a relatively low risk procedure, they are not without significant morbidity. A recent paper from our group has shown that despite a variety of proposed interventions to reduce pain and anxiety (lidocaine lubricant, viewing of the procedure, narration of procedure, quiet background music, etc.), over a half of patients reported moderate to severe discomfort and perceive anxiety associated with flexible cystoscopy to be a serious problem (14).

We previously have shown that patients who undergo more frequent cystoscopy than recommended for bladder cancer surveillance have twice as many transurethral resections and three times as many cancer-free resections without altering the rate of bladder cancer progression or death (15). Given the sheer volume of bladder cancer patients, the associated health care costs associated with cystoscopy should also not be forgotten. The National Cancer Institute estimated that bladder cancer care makes up about 3% of the 158-billion-dollar total cost of cancer care in the United States (16). In one study examining the costs of low-grade bladder cancer, endoscopic surveillance accounted for more than half of all Medicare payments (17). Thus, decreasing overuse of surveillance cystoscopy among low-risk NMIBC patients has the potential to increase the value of care by increasing quality and decreasing cost.

The present study shows that accurate documentation and risk-aligned surveillance for low-risk NMIBC are lacking. Although the study was conducted from multiple distinct facilities throughout the United States, there are a few limitations to note. First, our data are from the VA and thus generalizability to non-VA populations may be limited. However, bladder cancer is highly prevalent within the VA with more than 30,000 Veterans who are living with the disease (18). Thus, even if our results cannot be perfectly applied to the general population, they are still of high importance to many urologists and patients within the United States. Second, we excluded approximately 11% of encounters, because they did not have sufficient information to accurately designate bladder cancer risk or were lacking a documented surveillance recommendation, which might have contributed to selection bias. We excluded 46 encounters with a missing surveillance recommendation because a key aim of the analyses was to assess guideline-concordant surveillance recommendations. However, for these encounters, one can still assess accurate documentation of risk: 18 (39%) had accurate documentation and 28 (61%) did not. Thus, accurate documentation was slightly worse in this subset of excluded reports with a missing surveillance recommendation compared to the 52% with accurate documentation among the 296 encounters included in the analyses. Third, residents are constantly rotating through the VA which adds variability. However, a large body of work has demonstrated that resident involvement does not necessarily contribute to lower quality care. For example, resident participation in transurethral surgeries was not associated with an increased complication or readmission rate (19). In addition, attending urologists co-sign all notes and, as a result, are responsible for approving any medical decision-making including documentation of risk level and recommending a particular surveillance strategy.

Conclusion

Our study highlights that about a third of providers’ surveillance recommendations for low-risk NMIBC are not in line with the AUA/SUO guideline. These patients are undergoing cystoscopy procedures more often than necessary. Given that increased cystoscopy does not result in improved oncologic outcomes in this low-risk population, it is clear that adhering to guideline-based surveillance protocols is in the best interest of the patient. We also show that accurate documentation is associated with a higher likelihood of a guideline-concordant surveillance recommendation in low- and intermediate risk disease. Thus, the addition of a standardized risk-stratification section in clinical notes should be explored and evaluated as an intervention that may increase accurate documentation, as well as guideline-concordant surveillance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

We acknowledge programming support by Elise K. Gatsby, MPH, at the Salt Lake City VA Healthcare System.

SUPPORT:

This study was supported using resources and facilities at the authors’ Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare Systems, by VA HSR&D Merit Grant IIR 18– 215 (I01HX002780-01), and the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), VA HSR RES 13–457.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: Opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not constitute official positions of the US Federal Government or the Department of Veterans Affairs. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1. https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/#!/

- 2.Van Rhijn BW, Burger M, Lotan Y, et al. 2009. Recurrence and progression of disease in non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer: from epidemiology to treatment strategy. European urology, 56(3), pp.430–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R, et al. 2016. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. The Journal of urology, 196(4), pp.1021–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han DS, Lynch KE, won Chang J, et al. 2019. Overuse of cystoscopic surveillance among patients with low-risk non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer–a national study of patient, provider, and facility factors. Urology, 131, pp.112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeck FR, Lynch KE, won Chang J, et al. 2018. Extent of risk-aligned surveillance for cancer recurrence among patients with early-stage bladder cancer. JAMA network open, 1(5), pp.e183442–e183442. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2703953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bree KK, Shan Y, Hensley PJ, et al. 2022. Management, surveillance patterns, and costs associated with low-grade papillary stage ta non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer among older adults, 2004–2013. JAMA network open, 5(3), pp.e223050–e223050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeck FR, St Ivany A, Lowrance W, Makarov DV, Goodney PP and Zubkoff L, 2020. Patient perspectives on the implementation of risk-aligned bladder cancer surveillance: Systematic evaluation using the Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases framework. JCO Oncology Practice, 16(8), pp.e668–e677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeck FR, Ould Ismail AA, Perry GN, et al. 2022. Determinants of Risk-Aligned Bladder Cancer Surveillance—Mixed-Methods Evaluation Using the Tailored Implementation for Chronic Diseases Framework. JCO Oncology Practice, 18(1), pp.e152–e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. https://www.research.va.gov/programs/cipher.cfm .

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics, 42(2), pp.377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matulay JT, Tabayoyong W, Duplisea JJ, et al. 2020, October. Variability in adherence to guidelines based management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer among Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) members. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations (Vol. 38, No. 10, pp. 796–e1). Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salz T, Weinberger M, Ayanian JZ, et al. 2010. Variation in use of surveillance colonoscopy among colorectal cancer survivors in the United States. BMC health services research, 10, pp.1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sehdev A, Sherer EA, Hui SL, et al. 2017. Patterns of computed tomography surveillance in survivors of colorectal cancer at Veterans Health Administration facilities. Cancer, 123(12), pp.2338–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kukreja JB, Schroeck FR, Lotan Y, et al. 2022, January. Discomfort and relieving factors among patients with bladder cancer undergoing office-based cystoscopy. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations (Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 9–e19). Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeck FR, Lynch KE, Li Z, et al. 2019. The impact of frequent cystoscopy on surgical care and cancer outcomes among patients with low risk, non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer, 125(18), pp.3147–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariotto AB, Robin Yabroff K, Shao Y, et al. 2011. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 103(2), pp.117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skolarus TA, Ye Z, Zhang S, et al. 2010. Regional differences in early stage bladder cancer care and outcomes. Urology, 76(2), pp.391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM and Naik AD, 2010. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Federal practitioner: for the health care professionals of the VA, DoD, and PHS, 27(3), p.36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allard CB, Meyer CP, Gandaglia G, Chang SL, Chun FK, Gelpi-Hammerschmidt F, Hanske J, Kibel AS, Preston MA and Trinh QD, 2015. The effect of resident involvement on perioperative outcomes in transurethral urologic surgeries. Journal of Surgical Education, 72(5), pp.1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.