Abstract

The increasing number of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria in companion animals poses a threat to both pet treatment and public health. To investigate the characteristics of MDR Escherichia coli (E. coli) from dogs, we detected the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of 135 E. coli isolates from diarrheal pet dogs by disc diffusion method (K-B method), and screened antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), virulence-associated genes (VAGs), and population structure (phylogenetic groups and MLST) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for 74 MDR strains, then further analyzed the association between AMRs and ARGs or VAGs. Our results showed that 135 isolates exhibited high resistance to AMP (71.11%, 96/135), TET (62.22%, 84/135), and SXT (59.26%, 80/135). Additionally, 54.81% (74/135) of the isolates were identified as MDR E. coli. In 74 MDR strains, a total of 12 ARGs in 6 categories and 14 VAGs in 4 categories were observed, of which tetA (95.95%, 71/74) and fimC (100%, 74/74) were the most prevalent. Further analysis of associations between ARGs and AMRs or VAGs in MDR strains revealed 23 significant positive associated pairs were observed between ARGs and AMRs, while only 5 associated pairs were observed between ARGs and VAGs (3 positive associated pairs and 2 negative associated pairs). Results of population structure analysis showed that B2 and D groups were the prevalent phylogroups (90.54%, 67/74), and 74 MDR strains belonged to 42 STs (6 clonal complexes and 23 singletons), of which ST10 was the dominant lineage. Our findings indicated that MDR E. coli from pet dogs carry a high diversity of ARGs and VAGs, and were mostly belong to B2/D groups and ST10. Measures should be taken to prevent the transmission of MDR E. coli between companion animals and humans, as the fecal shedding of MDR E. coli from pet dogs may pose a threat to humans.

1. Introduction

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is one of commensal microbiota in the gut of humans and animals [1]. With the widespread use of antimicrobials, the occurrence of multi-drug resistance (MDR) E. coli in humans and animals has posed a major threat to public health [2,3]. The presence of MDR E. coli in companion animals, such as pet dogs, undoubtedly raises concerns for both dogs and humans due to the high antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the capability of carrying various antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) of MDR strains [4,5]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that there were associations between ARGs and virulence-associated genes (VAGs) existed in E. coli, and ARG-carrying strains may increase the likelihood of carrying VAGs [6]. However, only limited studies focused on MDR strains from pets in China, especially in Sichuan province which is considered as a major province for keeping pets in Southwest China [7].

In addition, recent studies have found that E. coli clones can be extensively shared between humans and household animals [8,9]. The transmission of high-risk E. coli clones between animals and humans has been recognized as a major public health issue [10,11]. For the population structure of E. coli clones, phylogenetic studies have shown that the B2 and D groups were more prevalent than the commensal groups (A and B1 groups) in E. coli isolates from diarrheic pet dogs [12,13]. Moreover, the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was also used to analyze the population structure of E. coli clones [14]. Recent studies have identified a high population diversity of STs which related to zoonotic or pathotype in E. coli isolates from pet dogs, such as ST354, ST393, and ST457 E. coli were observed in companion animals from Australia [15]. And the high-risk ExPEC clones associated with humans and multidrug resistance, including sequence type (ST) 38, ST131, ST224, ST167, ST354, ST410, ST617 and ST648, have been identified in cats and dogs in Thailand which suggested there may be clonal dissemination between pets and humans [16].

In 2023, the number of domestic pets has exceeded 100 million in China [7]. Moreover, the latest annual report shows that the use of veterinary antibiotics for animals in China has exceeded 30,000 tons in 2020, tetracyclines, β-lactamases, and sulfonamides antimicrobial agents were widely used (Veterinary Bulletin of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural People’s Republic of China, 2020) [17].With the widespread use of antimicrobials in animals, the high prevalence of MDR E. coli isolates from pet dogs has raised health concerns for both companion animals and humans [18,19]. To better understand the characteristics of MDR E. coli from pet dogs, we analyzed the antimicrobial resistance of E. coli isolates from diarrheal dogs, focusing on ARGs, VAGs, and population structure (ST and phylogenetic groups) for MDR E. coli to evaluate the potential threat.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

A total of 185 fresh feces samples were collected from pet dogs with clinical diarrhea during August 2021 to June 2022. Samples were excluded if the pet dogs were prescribed antimicrobial therapy or veterinary admission within the previous 3 months. The study was permitted by committee of Sichuan agricultural university (Permission number: DYY-2020303164) and the Sichuan Agricultural University Animal Ethical and Welfare Committee (Permission number: 20210268).

All samples were collected by professional veterinarians in Veterinary Teaching Hospital of Sichuan Agricultural University. Disinfection of hands and changing of disposable gloves were mandatory before sample collection. Samples were taken from the center of fresh feces by using sterile cotton swabs as soon as the pet dogs defecated to avoid cross-contamination from environmental bacteria on the ground. Then, samples were collected in sterile micro centrifuge tubes (Eppendorf) and were sent for processing to the laboratory within 12 h after collection.

2.2 Strains isolation

The isolation and identification of E. coli was performed as previous studies described [20,21]. Fecal samples were enriched in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C, 120 r/min in a shaking incubator for 24 h. All isolates were identified presumptively by using phenotypic methods, including Gram staining, MacConkey agar growth and Eosin Methylene Blue agar growth. We further used 16S rDNA sequences (Primer: 5’-GAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3’; 5’-AGAAAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC-3’) [22] for final identification of E. coli. The confirmed isolates were stored in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing 50% glycerol at −20°C for further analysis.

2.3 Screening of MDR strains by antimicrobial susceptibility test

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of all isolates were tested using the standard disk diffusion method recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). A total of 16 antimicrobial agents in 6 categories as below were tested. aminoglycosides (gentamicin, CN, 10 μg; tobramycin, TOB, 10 μg), tetracyclines (tetracycline, TET, 30 μg; doxycycline, DOX, 30 μg), amide alcohols (chloramphenicol, C, 30 μg), quinolones (ciprofloxacin, CIP, 5 μg), sulfonamides (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, SXT, 10 μg), β-lactams (ampicillin, AMP, 10 μg; cefazolin, KZ, 30 μg; cefuroxime, CXM, 30 μg; cefotaxime, CTX, 30 μg; cefepime, FEP, 30 μg; cefoxitin, FOX, 30 μg; aztreonam, ATM, 30 μg; imipenem, IPM, 10 μg; amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 2:1, AMC, 20 μg). For the 16 antimicrobial agents, the CN and TOB in aminoglycosides, DOX in tetracyclines, KZ, CTX, AMP, AMC in β-lactams and CIP in quinolones were used in pet animals at the location of our present study. The other antimicrobial agents (TET, C, CXM, FEP, ATM, IPM, FOX and SXT) have been found with E. coli resistance in dogs according to previous studies [23–25]. Results were interpreted in accordance with CLSI criteria (CLSI, 2023) [26]. E. coli ATCC25922 was used as a control. MDR strain was defined as being resistant to three or more antimicrobial categories [20].

2.4 DNA extraction and detection of ARGs, VAGs

Total genomic DNA of strains was extracted from isolates by using TIANamp Bacteria DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA samples were stored at -20°C for subsequent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection.

Primers of 23 ARGs in 6 categories (including 5 blaCTX-M alleles for group1, 2, 8, 9, and 25) and 25 VAGs in 5 categories were synthesized by Huada Gene Technology Co. Ltd (Shenzhen, China). The PCR primer sequences and conditions for the ARGs and VAGs were showed in S1 and S2 Tables, respectively. PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis in a 1.0% agarose gel in 1 × TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3), stained with GoldViewTM (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and photographed under ultraviolet light using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP omnipotent imager (Bole, USA). All positive PCR products were sequenced with Sanger sequencing in both directions by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Sequences of ARGs and VAGs were analyzed online using the BLAST function of NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

2.5 Phylogenetic grouping and MLST

Phylogenetic grouping (A/B1/B2/D) was determined for MDR E. coli isolates using PCR targeting chuA, yjaA, and TSPE4.C2 following the protocol of Clermont et al. [27]. MLST was based on the sequencing results of seven housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA and recA) in each strain to obtain a numerical allelic profile which is abbreviated to a unique identifier of each strain: sequence type (ST) [28]. Allelic types of all seven housekeeping genes and ST of strains were determined following the protocol of the E. coli MLST database (https://pubmlst.org) [28,29]. The primer sequences of genes for MLST and phylogroups were shown in S3 Table. PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis in a 1.0% agarose gel stained with GoldViewTM and photographed under ultraviolet light. All positive PCR products were sequenced with Sanger sequencing in both directions by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The sequences of housekeeping gene for MLST were analyzed online using pubMLST database (https://pubmlst.org).

The goeBURST algorithm in phyloviz 2.0 was used to clustering analysis of STs for MDR E. coli isolates, which divided the STs into several clusters, named as clonal complexes (CC), which consist of closely related STs with two allelic differences [30]. A clonal complex is typically composed of a single predominant genotype and closely relatives genotype [31].

2.6 Association analysis between ARGs and Antimicrobial resistance phenotypes (AMRs) or VAGs

The statistically analysis of data of AMR, ARGs and VAGs was conducted by using SPSS Statistics (version 26.0). P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Association analysis between ARGs and AMR or VAGs was performed by ggplot2 in RStudio (version 4.2.2; http://www.r-project.org) [32].

3. Results

3.1 AMRs of 135 isolates and Screening of MDR strains

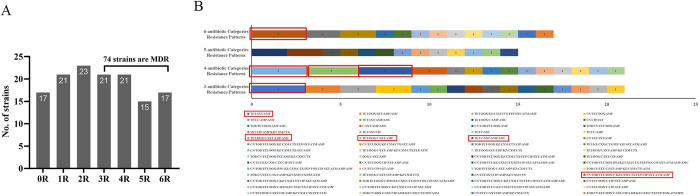

A total of 135 E. coli strains were successfully isolated from 185 fecal samples of diarrheal dogs. Among the 135 E. coli isolates, 118 strains (87.41%, 118/135) were resistant to at least one antimicrobial agent, while only 17 (12.59%, 17/135) strains were sensitive to all antimicrobial agents (Fig 1A). Among the 6 antibiotic categories, the resistance rate for β-lactam antibiotics had the highest resistance rats (76.30%, 103/135), followed by tetracyclines (64.44%, 87/135) and sulfonamides (59.26%, 80/135). The resistance rate to quinolones antibiotics was the lowest (25.93%, 35/135). Moreover, the resistance rates to AMP (71.11%, 96/135), TET (62.22%, 84/135), and SXT (59.62%, 80/135) were the top 3 in 16 antimicrobial agents. The lowest resistance rate was observed for FOX (3.70%, 5/135), and the resistance rates for remaining 12 antibiotics ranged from 4.44% (IPM) to 45.19% (DOX) (Table 1). We further analyzed the resistant-phenotype patterns of the 135 E. coli isolates, revealing that 54.81% (74/135) of isolates were identified as MDR E. coli (Fig 1A). Among the 74 MDR strains, 56 types of resistance phenotypic patterns were observed. The more common patterns were TET/SXT/AMP, TET/DOX/C/SXT/AMP/AMC, TET/DOX/C/SXT/AMP, TET/C/SXT/AMP/AMC, and CN/TOB/TET/DOX/C/KZ/CXM/CTX/FEP/CIP/SXT/ATM/AMP (Fig 1B).

Fig 1. Antibiotic resistance patterns of E. coli isolates from pet dogs.

(A) The abscissa 0R represents the strains that were sensitive to all antibiotics, and 1–6 R represents strains that were resistant to 1–6 antibiotic categories, respectively. Seventy-four E. coli isolates are MDR, of which 17 strains were resistant to 6 antibiotic categories; (B) Color bars demonstrate the distribution of phenotypic resistance patterns in 74 MDR E. coli isolates, and the Arabic number represent the number of strains. A total of 56 resistance patterns were observed by using disc diffusion assay. The red boxes highlight the prevalent resistant-phenotypes patterns (occurring three times), the other combinations (without red box) occurred only once or twice.

Table 1. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) detected in E. coli strains isolated from pet dogs (n = 135).

| Category of antimicrobial | No. of Resistant Isolates (%) |

Antibiotic | No. of Resistant Isolates (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | 103(76.30) | Penicillins | Ampicillin (AMP) | 96 (71.11) |

| 1rd/2nd generation Cephalosporins | Cefazolin (KZ) | 48 (35.56) | ||

| Cefuroxime (CXM) | 44 (32.59) | |||

| 3rd/4th generation Cephalosporins | Cefotaxime (CTX) | 45 (33.33) | ||

| Cefepime (FEP) | 21 (15.56) | |||

| β-lactam compound | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC) | 32 (23.70) | ||

| Monobactams | Aztreonam (ATM) | 25 (18.52) | ||

| Carbapenems | Imipenem (IPM) | 6 (4.44) | ||

| Cephamicins | Cefoxitin (FOX) | 5 (3.70) | ||

| Tetracyclines | 87(64.44) | Tetracycline (TET) | 84 (62.22) | |

| Doxycycline (DOX) | 61 (45.19) | |||

| Sulfonamides | 80(59.26) | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT) | 80 (59.26) | |

| Aminoglycosides | 45(33.33) | Gentamicin (CN) | 39 (28.89) | |

| Tobramycin (TOB) | 28 (20.74) | |||

| Amide alcohols | 41(30.37) | Chloramphenicol (C) | 41 (30.37) | |

| Quinolones | 35(25.93) | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 35 (25.93) | |

3.2 Distribution of ARGs and VAGs in MDR E. coli strains

Twelve out of 18 ARGs in 6 categories were detected in our present study (Table 2 and Fig 2). The detection rate of tetA (95.95%, 71/74) was the highest, followed by blaTEM (93.24%, 69/74) and blaCTX-M (90.54%, 67/74). Moreover, detection rates of flor, qnrS, and sul2 were all over 70% (74.32%, 74.32% and 70.27%, respectively). The detection rates of the remaining ARGs ranged from 16.22% (oqxAB) to 44.59% (sul1).

Table 2. Details of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) detected in MDR E. coli strains isolated from pet dogs (n = 74).

| Category of antimicrobial | No. of Resistant Isolates (%) |

Antibiotics | No. of Resistant Isolates (%) |

ARGs | No. of Positive Isolates (%) | Alleles of blaTEM/blaCTX-M (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | 71 (95.95) | AMP | 71 (95.95) |

bla

TEM

|

69(93.24) | blaTEM-1, 81.16 (56/69) |

| KZ | 38 (51.35) | blaTEM-135, 15.94 (11/69) | ||||

| CTX | 38 (51.35) | blaTEM-176, 2.90 (2/69) | ||||

| CXM | 38 (51.35) | bla CTX-M | 67(90.54) | blaCTX-M-14, 79.10 (53/67) | ||

| ATM | 25 (33.78) | |||||

| FEP | 21 (28.38) | blaCTX-M-65, 4.45 (3/67) | ||||

| AMC | 19 (25.67) | blaCTX-M-55, 31.34 (21/67) | ||||

| IPM | 6 (8.11) | blaCTX-M-64, 7.46 (5/67) | ||||

| FOX | 5 (6.76) | blaCTX-M-15, 5.97 (4/67) | ||||

| Tetracyclines | 71 (95.95) | TET | 69 (93.24) | tetA | 71(95.95) | -- |

| DOX | 49 (66.22) | -- | ||||

| Sulfonamides | 64 (90.54) | SXT | 64 (90.54) | sul2 | 52(70.27) | -- |

| sul1 | 33(44.59) | -- | ||||

| sul3 | 13(17.57) | -- | ||||

| Aminoglycosides | 2 (56.76) | CN | 37 (50.00) | aacC2 | 52(70.27) | -- |

| TOB | 28 (37.84) | aacC4 | 31(41.89) | -- | ||

| Amide alcohols | 40 (54.05) | C | 40 (54.05) | flor | 55(74.32) | -- |

| cmlA | 19(25.68) | -- | ||||

| Quinolones | 34 (45.95) | CIP | 34 (45.95) | qnrS | 55(74.32) | -- |

| oqxAB | 12(16.22) | -- |

Fig 2. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence-associated genes (VAGs) in 74 MDR E. coli strains from pet dogs.

(A) The bar graphs show the detection rates of ARGs and VAGs. A total of 12 ARGs and 14 VAGs were detected, of which tetA (95.95%) and fimC (100%) were the most prevalent; (B) The abscissa represents the ID of MDR isolates and ordinate represents ARGs and VAGs. The red and blue regions represent the presence or absence of corresponding ordinate genes in an isolate, respectively. A high diversity of ARGs and VAGs was detected among MDR strains.

We further analyzed the subtypes of blaTEM and blaCTX-M, 3 variants of the blaTEM gene and 5 variants of the blaCTX-M gene were detected. Among the 3 variants of the blaTEM gene, blaTEM-1 was the most frequent (81.16%, 56/69), followed by blaTEM-135 (15.94%, 11/69) and blaTEM-176 (2.90%, 2/69). For the blaCTX-M gene, 3 variants in blaCTX-M-1 group (blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-15 and blaCTX-M-64) and 2 variants in blaCTX-M-9 group (blaCTX-M-65 and blaCTX-M-14) were detected, blaCTX-M-14 (79.10%, 53/67) and blaCTX-M-55 (31.34%, 21/67) were more prevalent among the 5 variants observed, followed by blaCTX-M-64 (7.46%, 5/67), blaCTX-M-15 (5.97%, 4/67) and blaCTX-M-65 (4.45%, 3/67).

Fourteen out of 25 VAGs in 4 categories were detected in our study (Table 3 and Fig 2). The detection rate of fimC (100%, 74/74) was the highest, followed by iucD (90.54%, 67/74) and sitA (85.14%, 63/74). The detection rates of iss (72.97%, 54/74), ompT (71.62%, 53/74) and fyuA (71.62%, 53/74) were all above 70%. Detection rates of the remaining VAGs were ranged from 4.05% (aggR) to 54.05% (eae). Further analysis of the virulence determinants linked with different pathotypes revealed 3 DEC-related VAGs (eae, aggR, astA) and 11 ExPEC-related VAGs were detected. Notably, all MDR E. coli isolates carried at least one ExPEC-related VAG, 75.68% (56/74) of strains carried at least one DEC-related VAG, which also carried at least one ExPEC-related VAG. The average number of VAGs carried by per DEC-related strain (8.36) was significantly higher than that of DEC-unrelated VAGs strains (5.56) (P < 0.01).

Table 3. Detection rate of virulence-associated genes (VAGs) in MDR E. coli isolated from pet dogs (n = 74).

| Category of virulence | VAGs | No. of Resistant Isolates (%) |

Related pathotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron transport-related | iucD | 67 (90.54) | ExPEC |

| sitA | 63 (85.14) | ExPEC | |

| fyuA | 53 (71.62) | ExPEC | |

| Irp2 | 39 (52.70) | ExPEC | |

| iroN | 23 (31.08) | ExPEC | |

| Adhesion-related | fimC | 74 (100.00) | ExPEC |

| eae | 40 (54.05) | DEC | |

| tsh | 14 (18.91) | ExPEC | |

| Invasion-and-toxin related | vat | 33 (44.59) | ExPEC |

| astA | 36 (48.65) | DEC | |

| aggR | 3 (4.05) | DEC | |

| Antiserum survival factors-related | iss | 54 (72.97) | ExPEC |

| ompT | 53 (71.62) | ExPEC | |

| cvaC | 17 (22.97) | ExPEC |

3.3 Associations between ARGs and AMRs or VAGs in MDR E. coli strains

Details of the detection rates of ARGs and AMR in 74 MDR E. coli strains were showed in Table 2. High prevalence of the β-lactam antibiotics genes (blaTEM and blaCTX-M, 93.24% and 90.54%, respectively) were detected, and resistance rate of β-lactams antibiotic (AMP) was higher than 90% (71/74, 95.95%). For tetracyclines, tetA (71/74, 95.95%) was detected in MDR strains, and the proportions of strains with tetracyclines-resistant phenotypes were 95.95%. For sulfonamides, the resistant rate of SXT was 90.54% (64/74) in MDR strains, while detection rates of three related resistance genes (sul1, sul2 and sul3) ranged from 17.57% (13/74) to 70.27% (52/74). For aminoglycosides, only two resistance genes (aacC2 and aacC4) were detected with the detection rates ranging from 41.89% (31/74) to 70.27% (52/74), while the detection rate of MDR strains with aminoglycosides-resistant phenotype (CN and TOB) ranged from 37.87% (28/74) to 50% (37/74). Similarly, the detection rates of remaining antibiotic resistance phenotypes and related ARGs were fluctuated. Above results showed that only β-lactams and tetracyclines antibiotic-resistant phenotypes were generally matched with related ARGs in detection rates, but the others were not completely consistent.

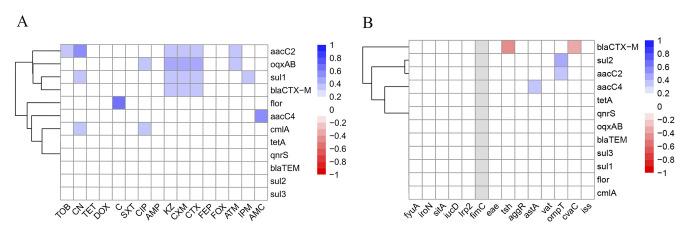

We further analyzed the associations between ARGs and AMR in 74 MDR strains. As shown in Fig 3A, a total of 23 positive association pairs (r > 0, P < 0.05) were observed between ARGs and AMR, of which the association between amide alcohols antibiotic resistance gene flor and amide alcohols-resistant phenotype (C) was the strongest. Moreover, the associations between 12 ARGs and 14 VAGs were further analyzed and the results were showed in Fig 3B, only 5 association pairs were observed, of which 3 pairs (sul2/ompT, aacC2/ompT, aacC4/astA) showed positive association (r > 0, P < 0.05), and the strongest association pair was observed between sul2 and ompT. The other 2 pairs (blaCTX-M/tsh, blaCTX-M/cvaC) were negative associations (r < 0, P < 0.05), and the strongest negative association pair was observed between blaCTX-M and tsh.

Fig 3. Heatmap of the correlation-coefficient (r) between ARGs and AMR or VAGs in 74 MDR E. coli strains from pet dogs.

Blue indicates positive association (r > 0, P < 0.05) and red indicates negative association (r < 0, P < 0.05). The color scale on the right of figure indicates the r-valve: (A) Heatmap of the correlation coefficient between ARGs and AMRs. The color scale and corresponding r-valve indicate the association between corresponding abscissa AMRs and ordinate ARGs. Twenty-three positive association pairs were observed, of which the strongest association was found between flor and C; (B) Heatmap of correlation coefficient between ARGs and VAGs. The color scale and corresponding r-valve indicate the association between corresponding VAGs (abscissa) and ARGs (ordinate). Five association pairs were observed (3 association pairs were positive and 2 association pairs were negative), of which the strongest positive association was found between ompT and sul2, the strongest negative association was found between blaCTX-M and tsh.

3.4 Phylogenetic Grouping and MLST of 74 MDR E. coli isolates

As shown in the Fig 4A, group B2 (71.62%, 53/74) was the most prevalent in 74 MDR E. coli strains, followed by group D (18.92%, 14/74) and group B1 (9.46%, 7/74). 90.54% (67/74) of the MDR E. coli strains belonged to virulent extraintestinal-related group (B2 and D) and only 9.46% strains belonged to commensal group (B1) (P < 0.001). Furthermore, we analyzed the average number of VAGs carried by per strain in different groups, of which the highest observed was 8.28 in group B2, followed by 7.29 in group B1 and 5.57 in group D (P < 0.01). And no significant difference (P > 0.05) was observed in the average number of VAGs carried by per strain between commensal group (B1) and virulent extraintestinal-related groups (B2/D) (Fig 4B).

Fig 4. Distribution of phylogenetic groups and STs in 74 MDR E. coli strains from pet dogs.

(A) The distribution of phylogroups in MDR strains. Commensal groups included groups A and B1, and virulent extraintestinal-related groups included groups B2 and D. Marking * represents a significant difference, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Significantly, the virulent groups were the most prevalent; (B) The average number of VAGs per isolate in each phylogroup. Marking * represents significant difference, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Obviously, the highest value observed was 8.28 in group B2.; (C) Minimum spanning tree of MLST types in MDR strains. The circle size indicates the proportion of isolates belonging to the ST. The color within each circle represents phylogroups and indicates the proportion of isolates belonging to different phylogroups. Each link between circles indicates one mutational event and the distance is scaled as the number of allele differences between STs. The yellow-green outlines of the circles represent the ST is the founder ST of one clonal complex (CC), and the other STs (with purple outlines of the circles) of the CC are derived from the founder ST with two allelic differences. The 74 MDR strains exhibited a high diversity of STs (42 STs were identified) in our present study and ST10 was the most prevalent; (D) The clonal complexes (CCs) among the 42 STs. Forty-two STs were clustered into 6 clonal complexes, and the remaining 23 STs were single. ST-10CC was the most prevalent lineage containing 6 STs; (E) Heatmap demonstrates the distribution of STs and phylogroups. The color scale and corresponding value indicate the number of E. coli isolates belonging to the corresponding phylogroups (abscissa) and STs (ordinate). Blue indicates a low number of strains, white indicates an intermediate value, and red indicates a high number of strains. As the heatmap shows, B2-ST10 was the most prevalent clone.

In addition, 42 different sequence types (STs) were identified in 74 MDR E. coli isolates (Fig 4C). Eleven strains belonged to ST10, followed by ST155 (4 strains), ST162 (4 strains), ST457 (4 strains), ST127 (3 strains) and ST410 (3 strains), the remaining 36 STs contained only one strains, respectively. Moreover, two new sequence types (nST1, nST2) were identified in our present study (S4 Table). By using goeBURST algorithm, 42 STs were clustered into 6 clonal complexes (CCs) and 23 singletons. Among the 6 clonal complexes, ST44, ST175, ST744, ST1415 and ST2197 were included in clonal complex 10CC with the founder ST10 (ST-10CC), and ST-10CC was the predominant lineage containing 17 MDR strains. ST345, ST410 and ST423 belonged to 90CC with the founder ST90 (ST-90CC); ST58, ST155 and nST1 belonged to 155CC with founder ST155 (ST-155CC); ST6209 and ST156 belonged to one clonal complex with the founder ST156 (ST-156CC), ST9580 and ST206 belonged to one clonal complex with the founder ST206 (ST-206CC), respectively. However, the CC contained ST359 and ST101 without any founder ST (Fig 4D). The heatmap of phylogroups and MLST distribution showed that 11 (14.86%, 11/74) strains simultaneously belonged to B2 group and ST10, which were the most prevalent clones in our present study (Fig 4E).

4. Discussion

The widespread use of antibiotics has significantly caused the increase of MDR E. coli which were isolated from companion animals [33]. To understand the characteristics of MDR strains and evaluate the potential threat, we detected the AMR of 135 E. coli isolates from pet dogs and further screened ARGs, VAGs, phylogenetic grouping and MLST for 74 MDR strains.

One hundred and thirty-five E. coli isolates from pet dogs showed high resistance to TET, AMP and SXT, which was consistent with another study in China [34]. Notably, TET has been used for treating animal infection disease and has also been used as “growth promoters” or “feed efficiency products” for a long time [35,36], which may activate the resistance of TET in E. coli. Once the antimicrobial-resistant E. coli occurs, it exists for a long time due to hard elimination [37]. In addition, TET resistance has been widely observed in E. coli from animals, such as dogs [13,24], yaks [38] and pigs [39], and the antibiotic resistance genes encoding AMR can be transmitted through environment and mobile genetic elements [40–42], which may be one of the reasons for high TET-resistant E. coli detected in our present study, even though TET has not been used in the area recently. The similar phenomenon was also found in the resistant strains to 3rd/4th generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and carbapenems antibiotics in our present study, which have been advocated to avoid or restrict use in veterinary antimicrobial selection in China [34,43]. The resistance rates of AMP and SXT were consistent with the results from pet dogs in Nigeria, Australia and Brazil [19,23,44]. According to previous studies, frequent use of antimicrobial agents in clinics may be responsible for the high resistance to AMP and SXT [45,46], the β-lactam antibiotics have also been widely used in the location of the present study, and SXT is one of the most animal-used antimicrobials in China [45]. In our study, we further screened 74 MDR strains from 135 E. coli isolates. Compared with previous studies in Sichuan, the detection rate of MDR strains among E. coli isolates from pet dogs decreased from 100% in 2017 [47] and 70% in 2018 [48] to 54.81% in our study during 2021–2022, which was similar to the trend observed in Northeast China (which decreased from 76.92% in 2012–2013 to 62.42% in 2021) [43]. The decrease in the MDR detection rate may be due to that the relevant authorities of China have released several policies to curb the increase in antimicrobial resistance in animal-derived bacteria [43]. Although the detection rate of MDR E. coli from pet dogs in Sichuan has decreased, it is still higher than that detected in other countries [44,49]. Overall, resistant strains may have been circulating in the dog population long before the antibiotic usage restriction were introduced, and AMR strains are currently difficult to eliminate. The high detection rates of MDR E. coli in our study implied that more effective measures should be taken to control the occurrence and spread of MDR E. coli from companion animals.

It is well-known that the antibiotic resistant phenotype of bacteria is related to ARGs [50]. Therefore, we further analyzed the distribution of ARGs in 74 MDR strains. In our study, 12 out of 18 ARGs were detected in 74 MDR strains (detection rates ranged from 16.22% to 95.95%), of which tetA, blaTEM and blaCTX-M were the dominant ARGs. Notably, the detection rate of tetA in our study was higher than previous studies from dogs in China which ranged from 28% to 85.08% [43,51,52]. The blaTEM and blaCTX-M were the prevalent β-lactam resistance genes in our study which were consistent with previous study for E. coli from dogs in China [43]. We further analyzed the prevalent subtypes of blaCTX-M genes, blaCTX-M-55 (in blaCTX-M-1 group) and blaCTX-M-14 (in blaCTX-M-9 group) were more prevalent. Among variants of blaCTX-M-9 group, blaCTX-M-14 has been considered as a common CTX-M variant worldwide, especially in China, Korea and Japan [53]. A high prevalence of blaCTX-M-14 was also observed in our present study (79.10%). Notably, blaCTX-M-14 was usually found on plasmid (such as IncF and IncK) according to previous studies [54,55]. The high prevalence of blaCTX-M-14-positive strains observed in our present study indicated a high risk of potential transmission. For variants of the blaCTX-M-1 group, blaCTX-M-55 has become the second most common CTX-M subtype in Chinese clinical E. coli isolates after blaCTX-M-14 [54], which was also dominant in our present study. Furthermore, Cottell et al. has observed the frequent clonal transmission of blaCTX-M-55-positive E. coli between different hosts (humans and animals such as duck, chicken, and swine) [54]. The high prevalence of blaCTX-M-14-positive and blaCTX-M-55-positive strains observed in our present study suggests more studies should focus on the capability of clonal transmission between different hosts in the future.

Increasing studies proposed that the relationship between AMRs and ARGs is not completely consistent [22,56]. The detection rates of β-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics resistant phenotypes were generally consistent with the related ARGs. However, for sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, amide alcohols, and quinolones, the detection rates of related ARGs were fluctuated, e.g., the resistant rate of sulfonamides was 90.54% in MDR strains, while the detection rates of sul ranged from 17.57% to 70.27%. Moreover, we further analyzed the statistical associations between ARGs and AMRs, 23 positive association pairs were observed in MDR strains. Only flor and C, blaCTX-M and CTX/CXM/KZ, oqxAB and CIP, aacC2 and TOB/CN showed consistency in ARG and related AMR. The other 16 association pairs were not completely consistent (Fig 3A). The similar phenomenon was also found in E. coli from captive non-human primates [22] and waterfowl [56] in China which indicated the different expression of ARGs, such as the abnormal expression of ARGs and the expression of ARGs has not reached that level which can activate the antibiotic resistance, may be a possible reason the incomplete consistency between AMR and ARGs [56].

Recent studies have shown that there was an association between ARGs and VAGs, and have proposed that they were linked and interacted with each other [6,56]. In order to explore the virulence traits and the association of ARGs and VAGs in MDR E. coli, we analyzed the distribution of VAGs in MDR strains. In our present study, 25 VAGs were selected for detection according to previous studies, among which 12 VAGs (eae, papA, bfpA, aggR, pic, astA, ipaH, stx1, stx2, elt, esta and estb) are related to Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) [57–59], the remaining 13 VAGs (fyuA, iroN, sitA, iucD, Irp2, fimC, tsh, vat, ompT, cvaC, iss, hlyF, hlyA) are related to Extraintestinal Escherichia coli (ExPEC) [60–62]. Eleven ExPEC-related VAGs and 3 DEC-related VAGs (eae, astA, aggR) were detected in our present study. And the detection rates of VAGs in our study, which ranged from 4.99% to 100%, were higher than previous studies in dogs from Shaanxi and Shandong, China (ranging from 0.6% to 81.6% in Shaanxi and 2.53% to 87.34% in Shandong, respectively) [34,63]. Moreover, 75.68% (56/74) of the MDR strains simultaneously combined at least one ExPEC-related and DEC-related VAG, indicating the MDR strains in our present study harbored VAGs related to different pathotypes and could be considered as potentially virulent hybrid pathogenic strains. MDR strains with potential hybrid pathogen detected in pet dogs will pose a threat to other companion animals and their owners.

In addition, the association between VAGs and ARGs among MDR strains was further analyzed. Five associated pairs were observed, of which 3 pairs were positive and 2 pairs were negative. Compared with other studies of E. coli from giant pandas (46 associated pairs, of which 45 pairs were positive and 1 pair was negative) [6] and waterfowl (43 associated pairs, of which 36 pairs were positive and 7 pairs were negative) [56], the associations observed between ARGs and VAGs in MDR strains from pet dogs were not common in our present study. The possible reasons for drawing associations between VAGs and ARGs may be related to the co-location on the same mobile genetic elements, while negative associations indicated gene incompatibilities [64]. Recent studies also showed that many ARGs were inserted into conjugative plasmids carrying VAGs, which may provide conditions for drawing positive associations between ARGs and VAGs [65]. In our study, the strongest positive association was observed between ompT and sul2, which is usually detected in plasmids, indicating the positive association between ompT and sul2 may be related to the plasmid [40,66]. Similarly, the location of aacC, which usually was detected in the variable region of integron, may be related to the other two positive associations (aacC2/ompT, aacC4/astA) observed in our present study [5]. The positive association between ARGs and VAGs implied the high risk of plasmid-mediated co-transmission of ARGs and VAGs in E. coli, which could accelerate the spread of VAGs and ARGs within E. coli populations and enhance the emergence possibility of new pathogens with increased virulence and resistance potential. Negative associations observed in our present study may also be related to mobile genetic elements. For example, the VAG cvaC is usually found in virulent IncF plasmids [66], while blaCTX-M is usually found in integron [67], the different locations on mobile genetic elements may be related to the negative associations between blaCTX-M and cvaC in our present study. While the specific mechanism for the associations observed in our study required more comprehensive studies to validate.

Previous studies have shown that groups A and B1 are considered to be commensal groups, and groups B2 and D are considered to be virulent extraintestinal-related groups [27], which have been classified as potentially pathogenic [5,6]. A study from Iran showed that resistant E. coli strains mostly belonged to groups B2 and D [68]. Similarly, our present results showed a high prevalence of strains belonging to virulent extraintestinal-related groups (B2 and D) were detected among MDR E. coli from pet dogs. According to previous study, phylogenetic grouping is closely related to virulence genes (group A and B1 strains carry fewer virulence genes, while group B2 and D strains carry more virulence genes) [6], whereas in our present study, no significant difference was observed in the average number of VAGs carried by per strains between commensal groups and virulent extraintestinal-related groups. These phenomena suggest that antimicrobial resistance may increase the possibility of carrying more virulent factors (for example, the number of VAGs carried) in E. coli strains [69], implying that highly antibiotics resistant intestinal E. coli strains may also lead to extraintestinal infections which could be an emergent public health issue for humans, animals and the environment [70,71].

At last, we used MLST to analyze the dominant lineage of MDR strains, and our results showed that 74 MDR strains exhibited a high population diversity of STs (42 STs were identified), of which ST10 was the most prevalent. Another study of E. coli from dogs in China has found that the pandemic clone was ST131 (accounting for 9.8%) [63], which was identified as the most common ST in ExPEC, covering all geographical regions [72]. Moreover, studies from Australia and Thailand showed that ST354 and ST410 were the dominant clones in E. coli isolates from dogs, respectively [15,16]. In our study, the most common ST was ST10 (occurring in 14.86% of strains) which was different from the above studies, indicating that the prevalent ST lineage of E. coli isolates from pet dogs may vary in different geographical regions. ST10 was widely detected in E. coli from other animals in China, such as pigs [73] and chickens [74], indicating that ST10 may be the prevalent ST in E. coli strains from animals in China. Moreover, ST10 strains mostly belonged to B2 groups in our present study, and this phenomenon was also observed in E. coli isolates from chickens [74] and in the ExPEC isolates from humans [75]. In other studies, ST10 strains identified from pigs [73] and humans [76] mostly belonged to group A or D. This phenomenon indicated that the relationship between ST and phylogroups may vary in E. coli isolated from different hosts.

5. Conclusions and limitations

Seventy-four MDR strains were observed among 135 E. coli isolates from pet dogs, of which 12 ARGs and 14 VAGs were detected, implying that the E. coli isolates can be considered as a pool of ARGs and VAGs. Moreover, groups B2 and D, which are classified as potentially pathogenic, were predominant in the MDR isolates, and ST10 was the prevalent clonal lineage. Our findings have important implications for a preliminary understanding of the characteristics of MDR E. coli from diarrheal dogs and evaluating the potential risk of resistance and virulence in canine E. coli.

In our present study, the number of samples included was limited and the sampling site was only at our Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Future investigations should include more samples and expand sampling areas. Moreover, the use of High-throughput Sequencing or Whole Genome Sequencing could provide more comprehensive information on MDR E. coli strains from diarrheal dogs.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ziyao Zhou, Junai Gan, and Lei Deng for the English language revision.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0500900, 2016YFD0501009), the Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding Research Foundation (CPF2017-05, CPF2015-4) and the Science and Technology Achievements Transfer Project in Sichuan province (2022JDZH0026). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Foster-Nyarko E, Pallen MJ. The microbial ecology of Escherichia coli in the vertebrate gut. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2022. May 6;46(3):fuac008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferri M, Ranucci E, Romagnoli P, Giaccone V. Antimicrobial resistance: A global emerging threat to public health systems. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2017. Sep 2;57(13):2857–76. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1077192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomba C, Rantala M, Greko C, Baptiste KE, Catry B, Van Duijkeren E, et al. Public health risk of antimicrobial resistance transfer from companion animals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016. Dec 20;dkw481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy CA, Walsh C, Karczmarczyk M, O’Brien S, Akasheh N, Quirke M, et al. Multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli in diarrhoeagenic foals: Pulsotyping, phylotyping, serotyping, antibiotic resistance and virulence profiling. Veterinary Microbiology. 2018. Sep;223:144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karczmarczyk M, Abbott Y, Walsh C, Leonard N, Fanning S. Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolates from Animals Presenting at a University Veterinary Hospital. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011. Oct 15;77(20):7104–12. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00599-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan S, Jiang S, Luo L, Zhou Z, Wang L, Huang X, et al. Antibiotic-Resistant Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Captive Giant Pandas: A Reservoir of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Virulence-Associated Genes. Veterinary Sciences. 2022. Dec 18;9(12):705. doi: 10.3390/vetsci9120705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang B, Li S, Liang G, Li J, Li Y. Current status and prospects of pet medical development in Sichuan province. Anim. Agriculture. 2023. 418; (01): 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson JR, Clabots C. Sharing of Virulent Escherichia coli Clones among Household Members of a Woman with Acute Cystitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006. Nov 15;43(10):e101–8. doi: 10.1086/508541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naziri Z, Poormaleknia M, Ghaedi Oliyaei A. Risk of sharing resistant bacteria and/or resistance elements between dogs and their owners. BMC Vet Res. 2022. Dec;18(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12917-022-03298-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhai W, Wang T, Yang D, Zhang Q, Liang X, Liu Z, et al. Clonal relationship of tet (X4)-positive Escherichia coli ST761 isolates between animals and humans. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2022. Jul 28;77(8):2153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nandanwar N, Janssen T, Kühl M, Ahmed N, Ewers C, Wieler LH. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) of human and avian origin belonging to sequence type complex 95 (STC95) portray indistinguishable virulence features. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2014. Oct;304(7):835–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vega-Manriquez XD, Ubiarco-López A, Verdugo-Rodríguez A, Hernández-Chiñas U, Navarro-Ocaña A, Ahumada-Cota RE, et al. Pet dogs potential transmitters of pathogenic Escherichia coli with resistance to antimicrobials. Arch Microbiol. 2020. Jul;202(5):1173–9. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-01828-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karahutová L, Mandelík R, Bujňáková D. Antibiotic Resistant and Biofilm-Associated Escherichia coli Isolates from Diarrheic and Healthy Dogs. Microorganisms. 2021. Jun 19;9(6):1334. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9061334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riley LW. Pandemic lineages of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2014. May;20(5):380–90. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo S, Wakeham D, Brouwers HJM, Cobbold RN, Abraham S, Mollinger JL, et al. Human-associated fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli clonal lineages, including ST354, isolated from canine feces and extraintestinal infections in Australia. Microbes and Infection. 2015. Apr;17(4):266–74. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nittayasut N, Yindee J, Boonkham P, Yata T, Suanpairintr N, Chanchaithong P. Multiple and High-Risk Clones of Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant and blaNDM-5-Harbouring Uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Cats and Dogs in Thailand. Antibiotics. 2021. Nov 10;10(11):1374. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10111374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annual report on the use of veterinary antibiotics in China (2020). Veterinary Bulletin of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural People’s Republic of China. VOL.23. NO.9. Available from: https://www.moa.gov.cn/gk/sygb/. [Google Scholar]

- 18.So JH, Kim J, Bae IK, Jeong SH, Kim SH, Lim S kyung, et al. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in Korean veterinary hospitals. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2012. Jun;73(2):195–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortega-Paredes D, Haro M, Leoro-Garzón P, Barba P, Loaiza K, Mora F, et al. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from canine faeces in a public park in Quito, Ecuador. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2019. Sep;18:263–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu Z, Pan S, Wei B, Liu H, Zhou Z, Huang X, et al. High prevalence of multi-drug resistances and diversity of mobile genetic elements in Escherichia coli isolates from captive giant pandas. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2020. Jul;198:110681. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mustapha M, Audu Y, Ezema KU, Abdulkadir JU, Lawal JR, Balami AG, et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Escherichia Coli Isolates from Diarrheic Dogs in Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. Macedonian Veterinary Review. 2021. Mar 1;44(1):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Z, Jiang S, Qi M, Liu H, Zhang S, Liu H, et al. Prevalence and characterization of antibiotic resistance genes and integrons in Escherichia coli isolates from captive non-human primates of 13 zoos in China. Science of The Total Environment. 2021. Dec;798:149268. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saputra S, Jordan D, Mitchell T, Wong HS, Abraham RJ, Kidsley A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolated from companion animals in Australia. Veterinary Microbiology. 2017. Nov;211:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott Weese J. Antimicrobial resistance in companion animals. Anim Health Res Rev. 2008. Dec;9(2):169–76. doi: 10.1017/S1466252308001485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustapha M, Audu Y, Ezema KU, Abdulkadir JU, Lawal JR, Balami AG, et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Escherichia Coli Isolates from Diarrheic Dogs in Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. Macedonian Veterinary Review. 2021. Mar 1;44(1):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2023). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, M100-33Ed, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and Simple Determination of the Escherichia coli Phylogenetic Group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000. Oct;66(10):4555–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francisco AP, Bugalho M, Ramirez M, Carriço JA. Global optimal eBURST analysis of multilocus typing data using a graphic matroid approach. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009. Dec;10(1):152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang F, Wang J, Li D, Gao S, Ren J, Ma L, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of 127 Escherichia coli strains isolated from domestic animals with diarrhea in China. BMC Genomics. 2019. Dec;20(1):212. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5588-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francisco AP, Bugalho M, Ramirez M, Carriço JA. Global optimal eBURST analysis of multilocus typing data using a graphic matroid approach. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009. Dec;10(1):152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feil EJ, Spratt BG. Recombination and the Population Structures of Bacterial Pathogens. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001. Oct;55(1):561–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Algammal AM. atpD gene sequencing, multidrug resistance traits, virulence-determinants, and antimicrobial resistance genes of emerging XDR and MDR-Proteus mirabilis. Scientific Reports. 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88861-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt VM, Pinchbeck G, McIntyre KM, Nuttall T, McEwan N, Dawson S, et al. Routine antibiotic therapy in dogs increases the detection of antimicrobial-resistant faecal Escherichia coli. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [Internet]. 2018. Sep 11 [cited 2023 Apr 22]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jac/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jac/dky352/5095201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui L, Zhao X, Li R, Han Y, Hao G, Wang G, et al. Companion Animals as Potential Reservoirs of Antibiotic Resistant Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Shandong, China. Antibiotics. 2022. Jun 20;11(6):828. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11060828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts MC, Schwarz S. Tetracycline and Phenicol Resistance Genes and Mechanisms: Importance for Agriculture, the Environment, and Humans. J Environ Qual. 2016. Mar;45(2):576–92. doi: 10.2134/jeq2015.04.0207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Applications, Molecular Biology, and Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001. Jun;65(2):232–60. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang S, Chen S, Abbas M, Wang M, Jia R, Chen S, et al. High incidence of multi-drug resistance and heterogeneity of mobile genetic elements in Escherichia coli isolates from diseased ducks in Sichuan province of China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2021. Oct;222:112475. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rehman MU, Zhang H, Iqbal MK, Mehmood K, Huang S, Nabi F, et al. Antibiotic resistance, serogroups, virulence genes, and phylogenetic groups of Escherichia coli isolated from yaks with diarrhea in Qinghai Plateau, China. Gut Pathog. 2017. Dec;9(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13099-017-0174-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng Z, Hu Z, Li Z, Zhang X, Jia C, Li T, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and population genomics of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in pig farms in mainland China. Nat Commun. 2022. Mar 2;13(1):1116. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28750-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang H, Cheng H, Liang Y, Yu S, Yu T, Fang J, et al. Diverse Mobile Genetic Elements and Conjugal Transferability of Sulfonamide Resistance Genes (sul1, sul2, and sul3) in Escherichia coli Isolates From Penaeus vannamei and Pork From Large Markets in Zhejiang, China. Front Microbiol. 2019. Aug 2;10:1787. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang S, Abbas M, Rehman MU, Huang Y, Zhou R, Gong S, et al. Dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) via integrons in Escherichia coli: A risk to human health. Environmental Pollution. 2020. Nov;266:115260. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salinas L, Loayza F, Cárdenas P, Saraiva C, Johnson TJ, Amato H, et al. Environmental Spread of Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) Producing Escherichia coli and ESBL Genes among Children and Domestic Animals in Ecuador. Environ Health Perspect. 2021. Feb;129(2):027007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Ji X, Liang B, Jiang B, Li Y, Yuan T, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Prevalence of Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli from Dogs and Cats in Northeastern China from 2012 to 2021. Antibiotics. 2022. Oct 28;11(11):1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leite-Martins LR, Mahú MIM, Costa AL, Mendes Â, Lopes E, Mendonça DMV, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in enteric Escherichia coli from domestic pets and assessment of associated risk markers using a generalized linear mixed model. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2014. Nov;117(1):28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng Y, Qin Z, Geng Y, Huang X, Ouyang P, Chen D, et al. Regional analysis of the characteristics and potential risks of bacterial pathogen resistance under high-pressure antibiotic application. Journal of Environmental Management. 2022. Sep;317:115481. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandes V, Cunha E, Nunes T, Silva E, Tavares L, Mateus L, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance of Clinical and Commensal Escherichia coli Canine Isolates: Profile Characterization and Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Results According to Different Guidelines. Veterinary Sciences. 2022. Jun 9;9(6):284. doi: 10.3390/vetsci9060284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y, An Z, Chen C. Isolation and antibiotics susceptibility testing of Escherichia coli isolated from dogs in Chengdu, Si-chuan. Veterinary Orientation. 2017;(15):75–76. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei B, Ou H, Yan W, Tian Y, Dan J, Tu R, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and integron-gene cassette detection of Escherichia coli isolates from diarrhea dogs. J. South China Agricultural University. 2018;39 (03):6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saputra S, Jordan D, Mitchell T, Wong HS, Abraham RJ, Kidsley A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolated from companion animals in Australia. Veterinary Microbiology. 2017. Nov;211:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poirel L, Madec JY, Lupo A, Schink AK, Kieffer N, Nordmann P, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Aarestrup FM, Schwarz S, Shen J, Cavaco L, editors. Microbiol Spectr. 2018. Jul 27;6(4):6.4.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yao C, Song X, Wang L, Liu B, Tian Y, Hu G. Detection of Resistance of Dog−derived Escherichia coli Isolates to Tetracy-clines. Acta Agriculturae Jiangxi. 2015;27(10):104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng X, Zheng T, Chen L, Wang M, Zhao M, Huang X, et al. Investigation on antimicrobial resistance and resistance genes of Escherichia coli from pet dogs in Fuzhou City. J. Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (Natural Science Edition). 2022;51(06):815–821. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2017. Aug 1;72(8):2145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cottell JL, Webber MA, Coldham NG, Taylor DL, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Hauser H, et al. Complete Sequence and Molecular Epidemiology of IncK Epidemic Plasmid Encoding bla CTX-M-14. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011. Apr;17(4):645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ho PL, Yeung MK, Lo WU, Tse H, Li Z, Lai EL, et al. Predominance of pHK01-like incompatibility group FII plasmids encoding CTX-M-14 among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli in Hong Kong, 1996–2008. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2012. Jun;73(2):182–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang S, Chen S, Rehman MU, Yang H, Yang Z, Wang M, et al. Distribution and association of antimicrobial resistance and virulence traits in Escherichia coli isolates from healthy waterfowls in Hainan, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2021. Sep;220:112317. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Algammal AM, El-Tarabili RM, Alfifi KJ, Al-Otaibi AS, Hashem MEA, El-Maghraby MM, et al. Virulence determinant and antimicrobial resistance traits of Emerging MDR Shiga toxigenic E. coli in diarrheic dogs. AMB Expr. 2022. Mar 17;12(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13568-022-01371-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puño-Sarmiento J, Medeiros L, Chiconi C, Martins F, Pelayo J, Rocha S, et al. Detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from dogs and cats in Brazil. Veterinary Microbiology. 2013. Oct;166(3–4):676–80. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pakbin B, Brück WM, Rossen JWA. Virulence Factors of Enteric Pathogenic Escherichia coli: A Review. IJMS. 2021. Sep 14;22(18):9922. doi: 10.3390/ijms22189922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Čurová K, Slebodníková R, Kmeťová M, Hrabovský V, Maruniak M, Liptáková E, et al. Virulence, phylogenetic background and antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli associated with extraintestinal infections. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020. Oct;13(10):1537–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim B, Kim JH, Lee Y. Virulence Factors Associated With Escherichia coli Bacteremia and Urinary Tract Infection. Ann Lab Med. 2022. Mar 1;42(2):203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson JR, Russo TA. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic (uropathogenic) Escherichia coli. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2005. Oct;295(6–7):383–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu X, Liu H, Li Y, Hao C. Association between virulence profile and fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from dogs and cats in China. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017. Apr 30;11(04):306–13. doi: 10.3855/jidc.8583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosengren LB, Waldner CL, Reid-Smith RJ. Associations between Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes, Antimicrobial Resistance Genes, and Virulence Genes of Fecal Escherichia coli Isolates from Healthy Grow-Finish Pigs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009. Mar;75(5):1373–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Venturini C, Beatson SA, Djordjevic SP, Walker MJ. Multiple antibiotic resistance gene recruitment onto the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli virulence plasmid. FASEB j. 2010. Apr;24(4):1160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sunde M, Ramstad SN, Rudi K, Porcellato D, Ravi A, Ludvigsen J, et al. Plasmid-associated antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Escherichia coli in a high arctic reindeer subspecies. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2021. Sep;26:317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. Genetic support of extended-spectrum b-lactamases. 2008; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yazdanpour Z, Tadjrobehkar O, Shahkhah M. Significant association between genes encoding virulence factors with antibiotic resistance and phylogenetic groups in community acquired uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2020. Dec;20(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01933-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosengren LB, Waldner CL, Reid-Smith RJ. Associations between Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes, Antimicrobial Resistance Genes, and Virulence Genes of Fecal Escherichia coli Isolates from Healthy Grow-Finish Pigs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009. Mar;75(5):1373–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Osman M, Albarracin B, Altier C, Gröhn YT, Cazer C. Antimicrobial resistance trends among canine Escherichia coli isolated at a New York veterinary diagnostic laboratory between 2007 and 2020. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2022. Nov;208:105767. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2022.105767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Denamur E, Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Gordon D. The population genetics of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021. Jan;19(1):37–54. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0416-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manges AR, Geum HM, Guo A, Edens TJ, Fibke CD, Pitout JDD. Global Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) Lineages. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019. Jun 19;32(3):e00135–18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00135-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheng P, Yang Y, Cao S, Liu H, Li X, Sun J, et al. Prevalence and Characteristic of Swine-Origin mcr-1-Positive Escherichia coli in Northeastern China. Front Microbiol. 2021. Jul 20;12:712707. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.712707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu Q, Zhang W, Luo L, Wang H, Shao H, Zhang T, et al. Genetic diversity and multidrug resistance of phylogenic groups B2 and D in InPEC and ExPEC isolated from chickens in Central China. BMC Microbiol. 2022. Feb 18;22(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12866-022-02469-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bozcal E, Eldem V, Aydemir S, Skurnik M. The relationship between phylogenetic classification, virulence and antibiotic resistance of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in İzmir province, Turkey. PeerJ. 2018. Aug 24;6:e5470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oteo J, Diestra K, Juan C, Bautista V, Novais Â, Pérez-Vázquez M, et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Spain belong to a large variety of multilocus sequence typing types, including ST10 complex/A, ST23 complex/A and ST131/B2. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2009. Aug;34(2):173–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]