Abstract

Childhood malnutrition is one of the foremost community health problems in the world, particularly in developing countries like India. This current review was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of various school-centered nutrition interventions/intervention programs developed in recent years, and their impact on the nutritional status, dietary habits, food preferences, lifestyle, and dietary behaviors in relation to diet, as well as physical activities for school children, especially adolescents. This review included studies found in the PubMed/Medline, SCOPUS, and Web of Science (WOS) databases, published from July 2017 to 2023. They were analyzed for eligibility criteria defined for this study, including school children and adolescents, school-based nutrition interventions/strategies/policies/initiatives, nutritional status, physical activity, dietary habits, and lifestyle. The Risk of Bias assessment was conducted using Review Manager version 5.4. Among 1776 potentially related studies, 108 met the eligibility criteria. Following this review, 62 studies were identified as eligible for this study, in which 38 intervention programs were discussed. A total of 13 studies were considered comprehensive and multi-component, 15 were nutrition education interventions, six were identified as physical activity interventions, and four focused on lifestyle and dietary behavior-related interventions. Another 24 of the 62 studies reviewed (approximately 39%) were either original articles, review articles, or articles pertaining to nutritional program guidelines, protocols, and/or reports. These studies uncovered a possible relationship between a decrease in BMI and school children's engagement in diet and/or physical activity. Results also suggest that these programs can be effective, although evidence for the long-term sustainability of changes in BMI was less evident and not fully substantiated/supported. Most of these findings are based on self-reported program data and may consist of biases linked to recall, selection of participants, and the desire to report favorable final measures (physical activity, lifestyle, and dietary habits). This study has the potential for use in public health programs devoted to healthy nutrition behavior and lifestyle practices. This research was primarily conducted by clinical researchers and did not receive any standardized institutional or organization-derived grant funding and support.

Keywords: health services, adolescent, children, intervention, school, malnutrition

Introduction and background

Malnutrition among children in India is a crucial wellbeing issue [1]. Both undernutrition and overnutrition have reached epidemic proportions in developing countries like India, where children and adolescents are most vulnerable. In these countries, wellbeing risks, especially related to malnutrition, are associated with poor and imbalanced nutrition, which are major causes of significant health concerns. These can further lead to slow cognitive and nervous system maturation [2]. Wellbeing habits and behaviors are established in early childhood and continue into adulthood [3]. In recent years, it has been observed that children's eating habits are influenced initially by family situations, with most changes occurring upon entering school, where they spend much of their time away from home [3]. Therefore, health education in schools is of utmost importance to promote adolescent health. By distributing and utilizing reliable internet information sources and encouraging critical thinking, schools can also play a significant role in helping adolescents filter out false information [4]. Obesity is a preventable disease, but with the influence of a Western lifestyle (characterized by a sedentary lifestyle and large consumption of processed foods, high-sugar beverages, sweets, fried foods, and high-fructose food items), its impact on the population is increasing dramatically. According to surveys conducted in Indian cities, the prevalence of overnutrition among school children is above 10%. Improved knowledge and behavior related to health and nutrition are highly associated with broad-level health and dietetics programs, especially in educational facilities in India [5]. The scientific literature reveals that the problem of undernutrition remains significant in school children, contributing to 22% of the country’s burden of disease [6]. The prevalence of poor nutritional status among children and adolescents greatly hinders national advancement, both socially and economically. Essential nutrition interventions have a significant effect on reducing the severity of undernutrition in India (NFHS-5). Older children and teenagers receive less attention from well-being providers compared to under-fives, especially in developing countries [7]. It is observed that at the personal level, weight loss interventions pointed at calorie input and output are frequently not fruitful in the long term. In this context, the Mid-day Meal Program, a multipurpose initiative of the Government of India, and the National Scheme known as PM Poshan (Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman) in schools are important policies addressing the nutritional needs of institute-going children, especially in the age group of 6-12 years, who are vulnerable to nutritional deficiencies with negative effects on growth and development [6]. The Focusing Resources on Effective School Health (FRESH) framework, developed in the early 2000s and primarily aimed at addressing undernutrition, was a pioneering international framework linking nutrition and education. Later, in 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Nutrition Friendly School Initiative (NFSI) to address the double burden of malnutrition. These two frameworks have laid the foundation for elements in schools that promote health [7], with support from the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) and the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP).

The findings indicate that nutritional status encompasses political, cultural, and social dimensions, supporting the need for multidimensional actions to enhance the dietary habits and lifestyle of school-going children and adolescents [8]. The first step in developing such interventions is to reference research and create a model based on treatments that are efficient, effective, acceptable in a school context, and allow for easy outcome analysis [9].

It is critical to understand the effect of various interventions implemented at the school level to improve healthy dietary practices in the context of evolving school-based nutritional programs and policies [10]. Hence, this present study aims to contribute to the literature from a different perspective by identifying only school-based interventional strategies and their effectiveness. These are directly engaged in promoting nutritional status, nutrition-related knowledge, dietary habits, lifestyle, and physical activity among school-going children and adolescents and have not been sufficiently and particularly emphasized in other systematic review studies. The intervention programs have been selected and documented in the form of a systematic review to be used as a guide in producing strategies with the same goal, following the final selection and extraction of the data components and implementation techniques. This will assist community stakeholders in identifying gaps and undertaking further studies, as well as informing the development of intervention training programs that pursue altering dietary behaviors by endorsing better dietary habits in this populace clutch.

Review

Methods

A systematic review has been conducted on various studies from all regions regarding school-based intervention strategies and their outcomes among school-going children and adolescents.

Selection Methods and Search Strategy

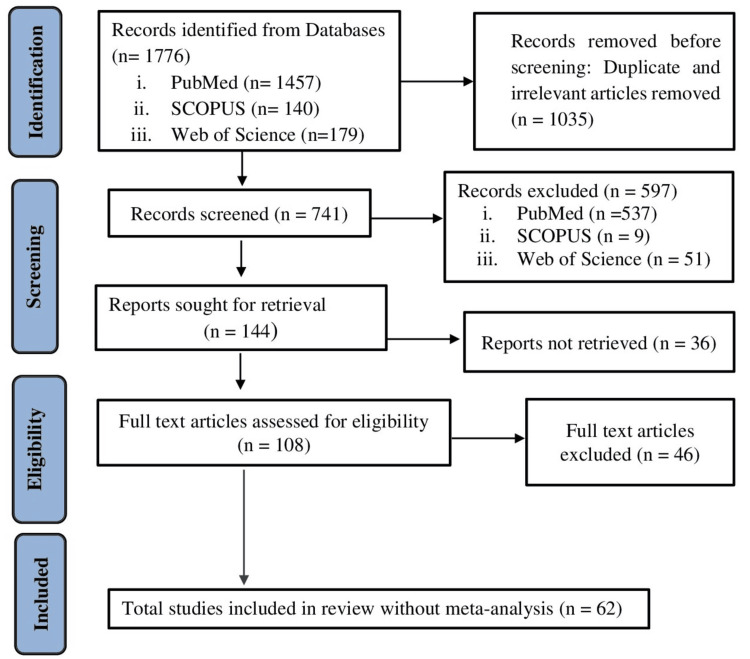

By following defined enrolment criteria, autonomously all dynamic titles, abstracts, and full-texts, including additional publications, were identified from the reference lists of these articles and these have been analyzed and interpreted accordingly. A PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science (WOS) exploration scheme was established and amended to additional databanks as required in June and July 2023. All these articles were screened and explored to identify nutrition-related papers by researcher one. Articles that indicated different school-based intervention strategies, such as nutrition education, health promotion, physical activity, counseling, nutrition/lifestyle management programs, etc., for school-going children and youths with outcomes clearly identifiable as nutrition-related, were reviewed by researchers one and two. When necessary, each database's approach was adjusted. In-person searches of allusion lists of previously published analyses and of included papers were conducted to ascertain additional research works. This process yielded 62 related scientific papers. The literature selection strategy is presented in Appendix 1. Figure 1 represents the search strategy in the form of a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework and search strategy (PRISMA flow chart).

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

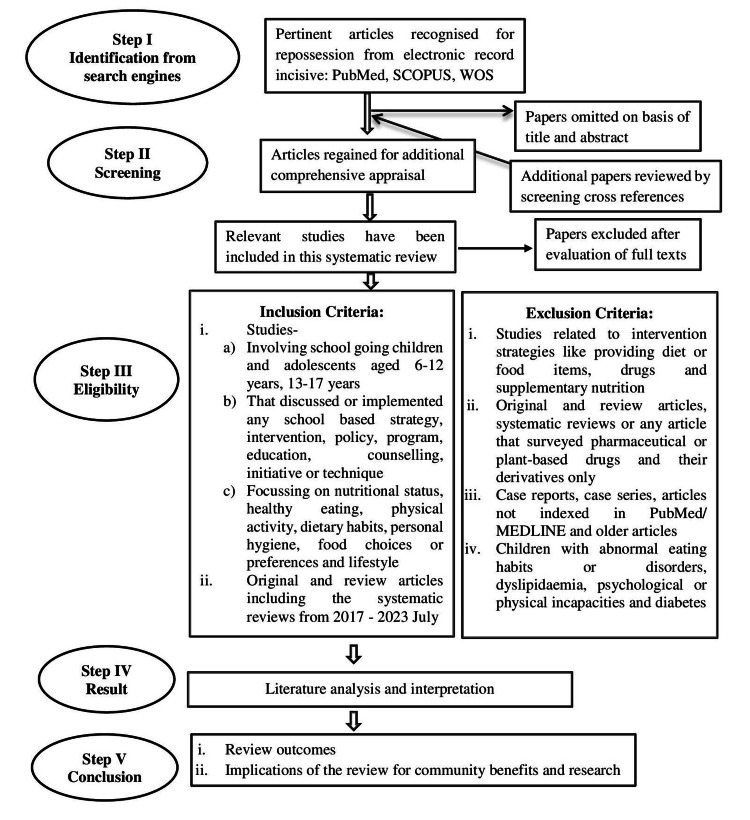

Inclusion Criteria

Articles eligible for inclusion in this review met one or more of the following criteria: scientific literature involving school children aged six to twelve years and early and middle adolescents aged thirteen to seventeen years; studies that discussed or implemented any school-based strategy, intervention, policy, program, education, counseling, initiative, or technique; studies focusing on nutritional status, healthy eating, physical activity, dietary habits, food choices or preferences, and lifestyle; original and review articles, systematic reviews, government guidelines, protocols, or policies from July 2017 to 2023. Table 1 represents the Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) format of the inclusion criteria.

Table 1. PICO and other criteria for inclusion.

PICO: Population Intervention Comparison Outcome.

| Criterion | Inclusion |

| Study design | Experimental or interventional research works, Quasi-experimental studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster randomized controlled trials (C-RCTs), systematic reviews and review articles |

| Setting | School/Educational institution |

| Nature of publication | Scientific papers available in peer reviewed journals (original and review articles, systematic reviews, government guidelines or protocols) |

| Language | English |

| Topographical expanse | All regions |

| Population (P) | School children of aged 6–12 years and adolescents between 13 and 17 years |

| Intervention (I) | Nutrition education, diet counselling, lifestyle and behaviour, physical activity |

| Contrast/Controller (C) | No intervention |

| Outcome (O) | Improved nutrition related knowledge, dietary habits and practices, physical activity level, lifestyle and behaviour in connection to nutritional status |

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded from the review if they demonstrated one or more of the following: related to intervention strategies such as culinary activities, providing diet or food items, drugs, and supplementary nutrition; exclusively web-based, technology-based, or online; original and review articles, systematic reviews, or any articles that surveyed pharmaceutical or plant-based drugs and their derivatives only; unpublished manuscripts and conference abstracts; studies involving children with abnormal eating habits or eating disorders, dyslipidemia, psychological or physical incapacities, and diabetes. Figure 2 displays the conceptual framework of the methodology.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of the methodology.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

A descriptive analysis was performed to extract data from each included study. The variables obtained from the selected articles were (1) Study details: author, year of publication, and country; (2) study setting and design; (3) intervention type; (4) study population: participants and their age during the intervention, along with gender; (5) sample size; (6) duration of intervention; (7) follow-up and number of dropouts; and (8) outcomes of the studies. The titles and/or abstracts and whole scripts of the relevant articles were evaluated by either author, and any inconsistencies were resolved by consensus between the authors or by both, according to the criteria for inclusion in the study. Table 2 displays the data extraction procedure.

Table 2. Data extraction procedure.

| Criteria | Parameters |

| Study characteristics | Author, year of publication, country, aims and objectives of the study, participant characteristics, study design, intervention content |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trial, interventional or experimental, original article, systematic review, and review articles |

| Study population | Sample size, age with gender |

| Intervention characteristics | Type, duration of study, follow up |

| Study setting | School or educational institution |

| Study outcome | Improved nutrition-related knowledge, dietary habits and practices, physical activity level, lifestyle, and behavior in connection to nutritional status |

Results

A total of 1776 studies were obtained from databases. Among these, 1457 studies were from PubMed, 140 from SCOPUS, and 179 from WOS. After excluding duplicate and irrelevant articles before screening (n = 1035) and facsimiles and extraneous apprenticeships (n= 633), 108 remaining full-text papers were read to assess their suitability and evaluated by the researchers. In addition, systematic studies were examined. After excluding full-text papers as per pre-specified exclusion criteria (n= 46), 62 [1-62] research works were included in this systematic review. A few studies appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but were excluded due to age group and study design. Among 23 studies [8,9,11,13-16,23,28,32,35,36,38,43,51-57,60,61], 22 are randomized controlled trials [8,9,11,13-16,23,28,32,35,36,38,43,51-55,57,60,61], and one study [56] is a pooled analysis from five randomized studies. There were six quasi-experimental trials [17,20,27,31,34,40] and 10 experimental or interventional studies [10,12,19,21,24-26,42,59,62].

In terms of sample sizes, they ranged from 51 to 5926 participants [8-17,19-21,23-28,31,32,34-36,38,40,42,43,51-55,57,59,60-62]. Fourteen studies [11,12,17,24,27,31,34,36,38,40,53,57,59,60] had fewer than 500 participants, 12 studies [8,9,13,20,21,23,25,35,42,43,54,62] had between 501 and 1000 participants, and another 12 studies [10,14-16,19,26,28,32,51,52,55,61] had more than 1000 participants.

Children between the ages of six and 12, and teenagers between 13 and 17 years, were the target groups for this systematic review, as specified in the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Regarding intervention types, 13 studies involved extensive multi-component strategies [8-16,31,34,52,55], 15 were nutrition education interventions [17,19,20,21,23-27,51,57,59-62], six focused on physical activity interventions [28,32,35,36,38,54], and four on lifestyle and nutrition-related behavior [40, 42, 43, 53]. Another 24 of the 62 included studies [1-7,18,22,26,29,30,33,37,39,41,44-50,58] were original articles, review articles, and government guidelines, protocols, policies, and reports regarding school children and adolescents’ nutritional status.

The duration of the interventions ranged from one day [12] to five years [52], with 25 studies [8,10-12,17,19-21,26-28,32,34-36,38,40,42,43,53,54,57,59,60,62] lasting less than one year. Post-intervention follow-ups, conveyed in 26 research articles [9,11,13,15,17,19,20,23,26-28,31,35,36,37,40,42,43,51-55,57,60-62], ranged between one week [28] and five years [52].

Regarding study settings, all the included studies were conducted in schools or educational institutions, and they had outcomes such as nutritional status, knowledge, attitude, practices, dietary habits, diet pattern, food preferences or choices, nutrition-related knowledge, practice of healthy eating, lifestyle, and behavioral change in relation to nutrition, physical activity, and body composition (BMI, WHO Growth References). Table 3 provides a summary of the key characteristics of the included studies, and Table 4 presents strategies in different combinations in multi-component school programs.

Table 3. Characteristics of the included studies.

(-) *: Not mentioned; HHS: Healthy High School.

| Author, year and study location | Study setting and design | Intervention | Participants and age during intervention | Sample size | Duration of the intervention | Follow up and number of dropouts | Outcomes |

| Fonseca LG et al., (2019) [8], Brasilia, Federal district, Brazil | School, Randomized Controlled Trial | Comprehensive problem-raising approach and pictorial representations | Brazilian adolescents, Mean age (years) =14.8±1.0 | n=676 | 4 months | 0 months, n=215 | Improved knowledge and practice of healthy eating |

| Scherr RE et al., (2017) [9], California | School (Randomized Controlled Trial) | Multicomponent healthy choice program | Upper elementary School children and adolescents (9 -12 years) | n=566 | 1 year | 2 months, n=82 | Nutrition knowledge, dietary behavior, BMI |

| Efthymiou V et al., (2022) [10], Athens, Greece | School, Multi-level intervention study | Comprehensive and multicomponent lifestyle intervention | Adolescents (12-17 years) | n=1610 | 6 months | 0 months, n=590 | Diet and exercise, BMI, Waist-Circumference, Waist to Height ratio, Waist to Hip ratio |

| Leme AC et al., (2018) [11], São Paulo, Brazil | School (Randomized Controlled Trial) | Multicomponent intervention | Girl school children (15.6±0.87 years) | n=253 | 7 months | 6 months, n=109 | Height and weight, waist circumference, dietary behavior |

| Raikar K et al., (2020) [12], Delhi, India | School, Intervention study | Comprehensive nutrition education using flip chart and two way discussion | School going adolescent girls from class 9th standard (13-15 years) | n=286 | 1 day | 0 months, n=21 | Nutrition knowledge |

| Ofosu NN , et al., (2018) [13], Canada | School, Randomized Controlled trial | Kids’ Health research project | School children and adolescents (10-15 years) | n=540 | 1 year | 1 year, n=59 | Health-related knowledge, attitudes, dietary intake, activity and weight status |

| Xu H et al., (2020) [14], China | School, Randomized Controlled Trial | Comprehensive nutrition education and physical activity intervention | School children (7-13 years) | n=4846 | 1 year | 0 months, n=87 | Overall dietary diversity, dietary habits, nutrition related knowledge, BMI |

| Duus KS et al., (2022) [15], Denmark | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Healthy High School (HHS) multicomponent Intervention on lifestyle | School students (6-7 years and 15-16 years) | n=4512 | 1 year | 9 months, n=65 | Healthy dietary habits, meal frequency |

| Liu Z et al., (2022) [16], China | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled trial | Multi-faced obesity intervention | School children (8-10 years) | n=1392 | 1 year | (-)* | BMI, physical activity, dietary behavior, obesity related knowledge |

| Glorioso IG et al., (2020) [17], Laguna, Philippines | School, Quasi experimental | Nutrition education program for healthier kids | Grade II and III students (7-9 years) | n=166 | 8 months | Total 5 follow-up meetings), n=0 | Improved knowledge on food and nutrition |

| Hamulka J et al., (2018) [19], Poland | School, The study was designed in two paths as: a cross-sectional study and an intervention study | Health educational intervention | Girls aged 11-13 years | n=2107 | 3 weeks | 9 months, n=74 | Nutrition and lifestyle related knowledge, dietary and lifestyle behaviors and body composition |

| Teo CH et al., (2021) [20], Malaysia | School, Quasi experimental study | Educational intervention | School children (7-11 years) | n=523 | 3 months | 3 months, n=0 | Anthropometric assessments, nutrition knowledge and eating practice |

| Anand D et al., (2020) [21], Tirupati, India | School, Intervention Study | Health and nutrition education program | Adolescent girls aged 13-17 years | n=700 | 6 weeks | 0 months, n=0 | Dietary pattern, anthropometric assessment, nutritional status |

| He FJ et al., (2022) [23], China | School, Cluster randomized Controlled trial | Nutrition education program | School children (8-9 years) | n=592 | 1 year | 3 months, n=27 | Dietary habits, practices, nutritional status |

| Aydın S et al., (2022) [24], Usküdar, Istanbul | School, Experimental or Intervention study | Nutrition education | School students (14-17 years) | n=216 | (-)* | 0 months, n=0 | Nutrition related knowledge, BMI, dietary habits and lifestyle |

| Hildrey R et al., (2021) [25], Storrs, USA | School, Intervention study | Tailored Nutrition Education | School children from 6th, 7th, 8th standard (10-15 years) | n=505 | 1 year | (-)*, n=0 | Nutrition related knowledge, behavior in dietary habits, physical activity |

| Seneviratne SN et al., (2021) [26], Colombo, Sri Lanka | School, Pre-post study design, Intervention study | Nutrition education | School children from grade 1 and 2 | n=1042 | 1 week | At the 2nd week post-test, n=0 | Eating habits, nutritional status |

| El Bastawi S et al., (2022) [27], Mansura, Egypt | School, Quasi-Experimental study | Educational intervention Program | School Children (7-12 years) | n=360 | 1 week | 1 month, n=5 | Nutrition related knowledge, attitude, dietary habit |

| Habib-Mourad C et al., (2020) [28], Lebanon | School, Randomized Controlled Trial | Physical activity intervention | School students (9-11 years) | n=2148 | 3 months | 1 week, n=128 | Dietary behavior, Nutrition knowledge; physical activity |

| Seo YG et al., (2021) [31], Korea | School, Quasi-experimental | Circuit training and nutrition intervention | School children (6-17 years) | n=242 | 2 years | 6 months, n=79 | BMI, body composition, nutrition and physical activity |

| Larsen MN et al., (2021) [32], Denmark | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Health Education through football program | School children (10-12 years) | n=3127 | 11 week | 0 months, n=3005 | Hygiene, nutrition, physical activity and well-being |

| Tapia-Serrano MA et al., (2022) [34], Spain | School, Quasi-Experimental design | Physical activity, lifestyle and dietary intervention | School children (8-9 years) | n=121 | 2.5 months | 0 months, n=0 | Self-rated health status, BMI, physical activity, sleep duration, dietary habit and sedentary screen time |

| Martínez‐Vizcaíno V et al., (2022) [35], Cuenca, Spain | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Physical activity intervention | School children (9-11 years) | n=562 | 6 months | 1 academic year, n=166 | Changes in physical fitness parameters, body composition (BMI, waist circumference) blood pressure, and biochemical parameters |

| Sebire SJ et al., (2018) [36], | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled trial | Physical Activity Intervention | Adolescent girls (12-13 years) | n=427 | 6 months | 2 months, n=39 | Moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time |

| Santina T et al., (2021) [38], Lebanon | School, Cluster randomized Controlled trial | Physical Activity Intervention | School Children (10-12 years) | n=374 | 14 weeks | 0 months, n=10 | Physical activity, behavior in relation to dietary habit, BMI, waist circumference |

| Sharif Ishak SI et al., (2020) [40], Malaysia | School (Quasi-experimental) | lifestyle program | Adolescents (13-14 years) | n=201 | 16 weeks | 3 months, n=125 | Knowledge, attitude and practice on healthy lifestyle and anthropometric measurements |

| Kamin T et al., (2022) [42], | School, Experimental | Behavior change in connection with dietary habits | Schoolchildren (10-16 years) | n=672 | 5 months | 4 months, n=131 | BMI, dietary habit, behavior change in terms of dietary habits, awareness of health risks related to consumption of sugar sweetened beverages |

| Moitra P et al., (2021) [43], Mumbai, India | School, Cluster randomized Controlled trial | Behaviorally focused nutrition education intervention | Students (10-12 years) | n=518 | 12 weeks | 2 months, n=20 | Knowledge, attitude, practice and diet |

| Ochoa-Avilés A et al., (2017) [51], Cuenca, Ecuador | School, Cluster randomized control trial | Nutrition education | Adolescents 12-14 years | n=1079 | 2 years and 4 months | 1st follow up 17 months, 2nd follow up 11 months | Healthy dietary habits, physical activity, BMI, reduced waist circumference |

| Lane HG et al., (2017) [52], Maryland | School, Cluster randomized control trial | Multi-component intervention | School children from 3rd to 7th grade (6-12 years) | n=1080 | 5 years | 2.5 years, n=0 | Obesogenic behavior and weight, BMI, physical activity, health literacy |

| Kubik MY et al., (2018) [53], Philadelphia, United States | School, Randomized Controlled Trial | Lifestyle intervention | School children 8-12 years | n=114 | 9 month | At 12 months post intervention and 24 months follow up | Child age- and gender-adjusted BMI z-score, dietary intake, physical activity |

| Ten Hoor GA et al., (2018) [54], The Netherlands | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Physical activity intervention | Adolescents 11-15 years | n=695 | 6 months | At 12 months, n=187 | Body composition, daily physical activity, sedentary behavior |

| Silva KS et al., (2020) [55], Brazil | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Multi-component intervention | Adolescents 7th to 9th grade school children | n=1090 | 1 year | 2 months n=91 | Physical activity, Sedentary behavior, self-efficacy, nutritional status |

| Ponnambalam S et al., (2022) [57], Puducherry, India | School, Randomized Controlled Trial | Nutrition education | Adolescents aged 11-14 years | n=280 | 9 months | 9 months n=0 | Waist circumference, eating behaviors |

| Haney MO et al., (2017) [59], Turkey | School, Intervention study | Educational Intervention | School children from 4th grade | n=51 | 2 weeks | (-)* | Dietary habits, BMI |

| Bagherniya M et al., (2017) [60], Iran | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Nutrition education intervention | Adolescent overweight girls aged 12-16 years | n=172 | 7 months | At 3.5 months and 7 months, n=18 | BMI, Waist circumference, dietary intake and behavior |

| Habib-Mourad C et al., (2020) [61], Beirut, Lebanon | School, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Nutrition education intervention | School children from 4th -5th grade (8-12 years) | n=1239 | 2 years | 1 year, n=433 | Dietary habits, Physical activity, knowledge, Self-efficacy |

| Wadolowska L et al., (2019) [62], Poland | School, Intervention study | Nutrition education intervention | School children aged 11-12 years | n=668 | 9 months | At 9th month, n=187 | BMI, Waist to Height Ratio, Diet quality, Nutrition Knowledge, sedentary and active lifestyle |

Table 4. Strategies in different combinations in multi-constituent school programs.

| Multi-constituent strategies |

| Comprehensive nutrition intervention strategies |

| Nutrition education |

| Diet counselling |

| Lifestyle intervention |

| Behavioural intervention related to dietary habits |

| Physical activity intervention |

| School health promotion program |

Discussion

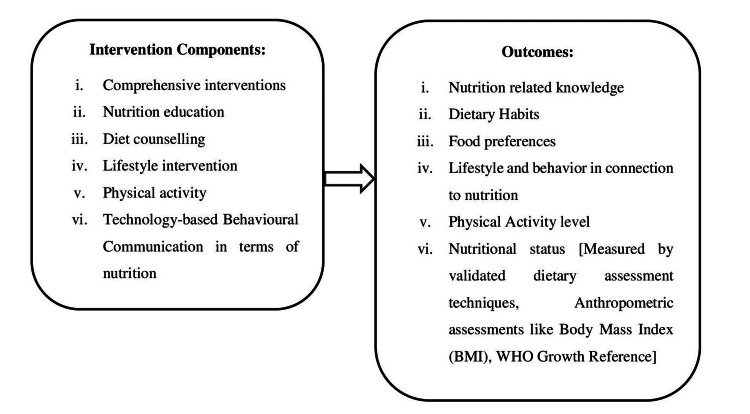

This systematic review is an effort to bring together various evidence-based studies on effective school-based nutrition interventions that promote healthy dietary practices, food preferences, lifestyle, diet-related behavior, and knowledge, as well as the nutritional status of school children and adolescents. It has been found that health and nutrition-related intervention programs significantly impact the health, knowledge, lifestyle, and behavioral status of school-aged children and adolescents in relation to dietary habits. This underscores the need to increase mindfulness about the benefits of including whole foods in daily diets [7,8,10,11]. Of the examined studies, 34 out of 38 demonstrated favorable correlations between specific interventions and improved outcomes [8-17,19-21,23-28,31,32,34-36,38,40,42,43,51-55,57,59,60,61,62]. The key interventions were grouped into four categories based on the nature and type of interventions.

Type of Interventions and Their Combinations

Multi-component interventions: Among the evaluated studies, 13 were comprehensive multi-component interventions [8-16,31,34,52,55]. These trials impacted BMI, understanding of nutrition, practice of healthy eating, dietary diversity, level of physical activity, self-efficacy for exercise, waist circumference, and personal hygiene. Nutrition and health education using a problem-raising approach, utilization of visual aids like flip charts and picture representations, and lifestyle and behavioral intervention in combination are consistent improvement characteristics across trials [8,9,11,12,14]. These studies also show that health education based on an interactive, participative, problem-raising strategy with the use of food illustrations, combined with physical exercise, can affect dietary intake.

Nutrition Education

Among the evaluated studies, 15 focused on nutrition education interventions [17,19-21,23-27,51,57,59-62]. These studies were classified according to their direct focus on nutrition education. One common factor for improvement was a structured nutrition education program with interactive discussion, practical nutrition lessons, and a dedicated time slot led by professional, trained school teachers and trained peers [15,18,21,24,52]. The impact of these activities is mostly a change in dietary habits and nutrition-related knowledge, justifying the success of these components. The educational activities in the classroom are based on formal education, employing organized material with precise objectives to transmit knowledge about the benefits of eating right.

Physical Activity Interventions

A rise in physical activity and a decline in sedentary behaviors have been identified in six studies [28,32,35,36,38,54]. A self-sustaining, school-based physical activity program run by experts and qualified school teachers with strong nutritional knowledge has been found to be one of the common improvement factors across these studies [28,32,35,36,38,54]. This underlines the importance of implementing interventions that not only concentrate on enhancing a single healthy habit but also design dietary strategies aimed at adopting an overall healthy lifestyle, including physical activity. In this regard, current research shows that addressing two health behaviors simultaneously with a multidisciplinary approach may have an indirect or synergistic impact [14,45,48]. BMI and waist circumference were found to have changed in 25 of the analyzed studies [8,9,12,14,17,18,20,21,25,26,28-30,32,34,35,44-48,50,53-55] after implementing a physical activity intervention program. Four of these studies [10,49,51,52], which used self-report methods to assess changes in health behaviors, revealed no significant changes in BMI and waist circumference. They also had a low retention rate at follow-up, failed to account for a significant number of trials, tracked weight using BMI and waist circumference restrictions, which made it impossible to determine the best possible outcomes, and had a strained intervention that might not be generalizable to other populations. This highlights the need for thorough follow-up, standardized testing, generalizable intervention programs, and the consideration of socioeconomic status in achieving the best outcomes.

Lifestyle and Nutrition-related Behavior Intervention

Lifestyle and behavioral interventions, such as altering eating habits, eating behaviors, and awareness of health risks, significantly improved nutrition-related knowledge, attitude, and practice in healthy lifestyles among school-aged children and adolescents, as demonstrated by four studies [40,42,43,53]. A systematic and well-organized lifestyle intervention program was attributed in one research noted by Sharif Ishak SI et al., 2020 [40] to a decrease in abdominal obesity; this conclusion is also supported by the findings of studies conducted by Kamin T et al., 2022 [42]. These findings imply that lifestyle programs that do not just concentrate on diet are more successful [14-16].

Other Key Findings

Regarding the primary attributes of the findings, the sample size ranged from 51 to 5926 [8-17,19-21,23-27,28,31,32,34-36,38,40,42,43,51-54,55,57,59,60,61,62]. The majority of the studies used large sample sizes, specifically between 501 and 2000 participants. Only 14 of the selected studies [11,12,17,24,27,31,34,36,38,40,53,57,59,60] involved fewer than 500 attendees, specifically, ranging from 51 to 500, allowing for reliable results. However, the sizes of the research samples varied significantly. The limited sample sizes could be attributed to various factors, such as studies carried out with specific gender participants (only female) [11,12,19,21,36,60]; in rural areas, which often have smaller populations [17]; lack of a control group and focusing on a particularly selected group of people [24,27,36,40]; not using probability sampling methods [31]; and selecting schools from a small area [34,38]. Despite some research involving a significant number of selected schools, the proportion of students included in the studies was quite low [17,24,31,34,53,57,59,60], often due to loss of follow-up [40]. Intervention duration is another important key feature that can affect the results of intervention programs. Overall, the short and long-term intervention periods provided in the chosen research varied from one day [12] to five years [52], with 25 studies [8,10-12,17,19-21,26-28,32,34-36,38,40,42,43,53-55,57,59,60,62] lasting less than a year. This indicates that these strategies may prove successful in the long run. For example, consider the research done by Scherr RE et al., 2017 [9], Ofosu NN et al., 2018 [13], Xu H et al., 2020 [14], Duss KS et al., 2022 [15], Liu Z et al., 2022 [16], He FJ et al., 2022 [23], Hildrey R et al., 2021 [25], whose duration is one year; by Seo YG et al., 2021 [31] and by Habib-Mourad C et al., 2020 [61], each lasting two years; by Ochoa-Avilés A et al., 2017 [51], lasting two years and four months; and Lane HG et al., 2017 [52], lasting five years. Considering these investigations were conducted in a school setting, it is safe to infer that the intervention was paused at least during the summer break. It is important to highlight in the common findings that the effects of interventions tend to diminish over time [8,10,12,14,21,24,25,32,34,38]. In this respect, it might be assessed to see if the newly learned healthy behaviors are maintained over time, especially after the intervention is complete, as this is the major goal of any research. A recent study that looked at the effect over time of an educational intervention on diet, physical activity, and BMI in children, including adolescents, discovered that the intervention was still effective after two years [31]. In one multi-component nutrition intervention research on BMI by Scherr RE et al. in 2017, significant results were shown one year after the intervention [9]. Improvements in weight were seen in both investigations. There was consistency in the approach used to evaluate participants' nutrition knowledge through the use of various questionnaires [8,9,12,14,16,17,20,24,25,27,28,36,40,43,51-57,59,61,62]. Every type of questionnaire used with children and adolescents follows a proven approach. Although there are several types and proven models for each, there is no consensus on the best method to assess nutritional knowledge. Using questionnaires has drawbacks, as the information gathered may be skewed, among other issues. However, studies have demonstrated that school-age children and teenagers, even as young as six years old, are capable of responding to questions about themselves, including those about their health and nutrition [31]. Figure 3 shows the relationship between intervention components and outcomes.

Figure 3. Relationship between intervention components and outcomes.

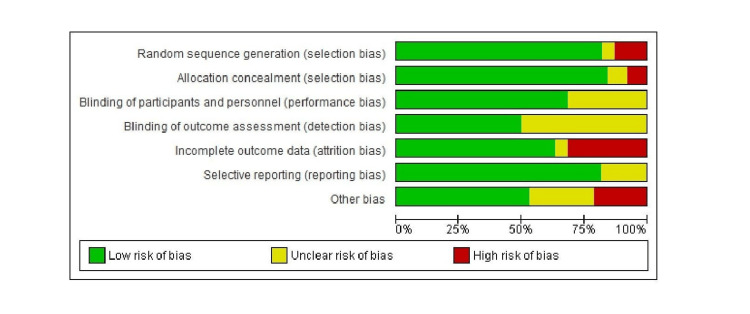

Risk of Bias assessment

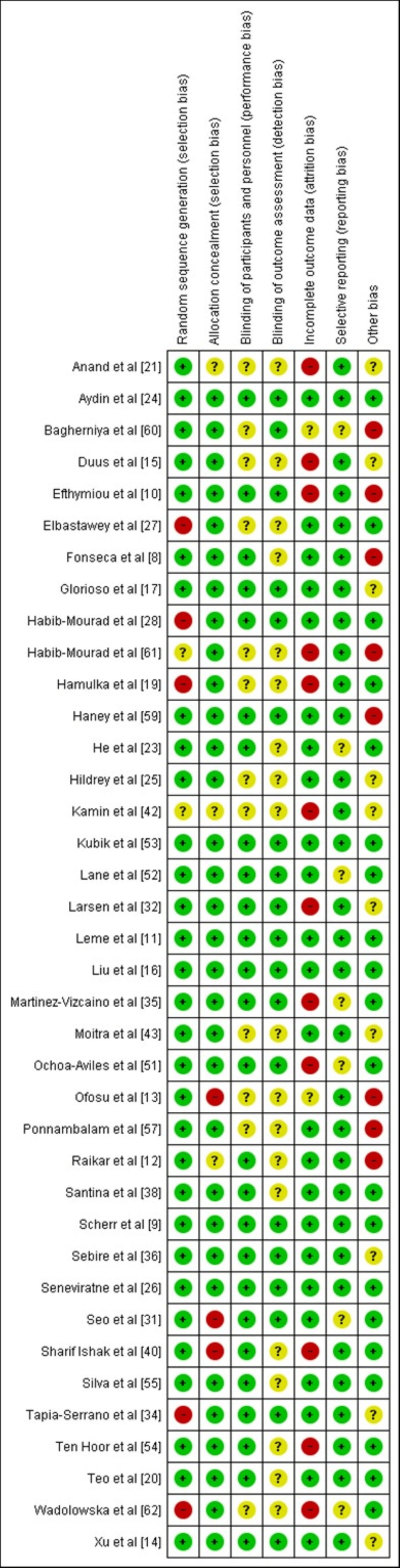

The Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment has been conducted using Review Manager version 5.4. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the risk of bias graph and the risk of bias summary of the included studies, respectively. The RoB assessment aims to assess the risk of bias for each of the seven domains in the RoB1 tool. These domains include bias arising from inadequate generation of a randomized sequence; bias due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment; bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study; bias due to knowledge of allocated interventions by outcome assessors; bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data; bias due to selective outcome reporting; and any other bias not mentioned above. The signaling questions 'bias arising from inadequate generation of a randomized sequence' and 'bias due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment' were most often identified. This was in part because studies did not clearly report how the allocation sequence was generated and concealed. Other biases amongst the studies are due to the measurement of outcomes, such as self-reported dietary habits, physical activity outcomes, recall bias, social desirability bias, and others [14,15,17,21,25,32,34,36,42,61]. Furthermore, a few studies failed to explain their sample size estimation [14,17,25,34,36,42]. The lack of information reported in studies regarding certain domains might have masked underlying biases that could not be identified.

Figure 4. Risk of bias graph about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across the included studies.

Figure 5. Risk of bias summary of each risk of bias item for included studies.

Green: Low risk of bias; Red: High risk of bias; Yellow: Unclear risk of bias.

Advantages and Limitations

The key advantage of our review is the systematic search strategy performed, which makes it less likely to overlook important regional studies. It also offers many other advantages. For example, this review provides a thorough and current assessment of this subject; it analyzes and assesses each of the factors that can contribute to the success of these techniques; it notes the presence of follow-up sessions, along with the size of the sample and the length of the intervention in the studies that were chosen; it demonstrates the reliability of the data, has used three databases (PubMed, SCOPUS, WOS), and includes 62 related articles. Additionally, this systematic review has a few limitations. Firstly, most findings are based on self-reported data and, hence, have biases such as recall bias, selection bias, and social desirability bias. Secondly, as some studies implemented a multi-interventional program, it is difficult to determine the extent to which reductions in anthropometric markers, e.g., BMI and waist circumference, were due to the physical activity intervention as distinct from other components (such as dietary habit change). Thirdly, further research will be required to determine the relative effects of physical activity interventions alone, both quantitative and qualitative, or a combination, when compared to those of nutrition interventions alone or in combination with each other.

Conclusions

This systematic review has found that improving both short- and long-term eating behaviors in schoolchildren and adolescents may be accomplished through interventions that alter their environments. However, it is also apparent that the majority of research have not concentrated on various contextual factors, which may have a significant impact on the efficacy of various nutritional interventions. To improve young adolescents' and school-age children's overall health and nutritional status, it is crucial to concentrate on and plan cost-effective, thorough, multi-strategic intervention studies. Exploring strategies that incorporate each of the components stated below might be intriguing to have a greater impact on the nutrition and health of schoolchildren and the teenage population: (a) approaches that emphasize acquiring a healthy lifestyle overall rather than only changing eating practices, including physical exercise as part of the intervention; (b) due to the significant influence parents have on their children's eating habits, interventions that focused on the school and the settings of children engaged parents in the intervention; (c) techniques that incorporate health knowledge, such as classes on nutrition; and (d) techniques that assess long-term impacts after an intervention is complete to see if the positive outcomes are sustained over time. However, it would be intriguing to examine the potential implications of these approaches on other parameters, like changes of body mass and constituents or biomarkers.

Ideally, this review should assist community stakeholders, such as school administrators, teachers, students, parents, policy makers, health professionals, health educators, and research materials in framing the National Nutrition Education Programs. Such programs address the unfinished agenda of interventions needed to address the dual burden of malnutrition among schoolchildren and adolescents for improving the health status of the community as a whole. Even though school-based nutrition programs have evidence suggesting they can in theory be effective, evidence of the long-term sustainability of these programs has yet to be studied or reviewed in any formidable detail.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Madhavi Bhargava, Associate Professor from the Department of Community Medicine, and Dr. K. S. Ali, Assistant Professor from the Department of Library and Information Science at Yenepoya Medical College, Deralakatte, Mangalore. They also thank Dr. Prasanna Mithra P, Additional Professor in the Department of Community Medicine at Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, and Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India, for their immense support and help with the search strategy while preparing the manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Literature Selection Strategy

Electronic databases have been used to enable a thorough, systematic investigation into research like PubMed/ Medline, SCOPUS, WOS and was searched until 2023 July to identify relevant studies. Exploration was restricted to journals with tutelages available in English and English titles, abstracts and keywords with phrases such-as “body mass index/BMI”, “Underweight/ under-nutrition”, “Obesity”, “Malnutrition”, “School”, “Lifestyle”, “Dietary habits”, “Food choices”, “Physical activity”, “Personal hygiene”, “Children”, “Adolescent”, “Risk factors”, “Intervention”, “Strategies”, etc.

PubMed search is standardized appropriately: (school) AND ((physical activity) AND (physical education) AND (exercise) AND (physical fitness) AND (sports) AND (lifestyle) AND (nutrition) AND (malnutrition) AND (intervention) AND (nutrition education) AND (energy intake) AND (energy density) OR (calories) AND (food) OR (fruit) OR (vegetable)) AND ((weight) OR (obese) OR (overweight) OR (weight reduction) OR (under-nutrition) OR (anthropometric) OR (anthropometry) OR (nutritional status) AND (nutrition assessment) OR (BMI) OR (waist circumference) OR (adipose tissue)) AND (child[MeSH:noexp] OR adolescent[MeSH])).

SCOPUS search is standardized appropriately: (KEY(School based) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(physical education) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(physical exercise) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY(Sports) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Nutrition intervention, nutrition education) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY(Supplementary nutrition, meal consumption) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Food preferences, dietary habits) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Lifestyle, behavior) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Body weight) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Obese) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Overweight) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Body Mass index) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Waist circumference) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(School children) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Adolescents)) AND PUBYEAR > 2016 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND ( LIMIT- TO (LANGUAGE, English)).

Web of Science (WOS) search is standardized appropriately: nutrition intervention (Topic) and school (All Fields) and children (All Fields) and adolescents (All Fields) and habits (All Fields) and dietary (All Fields).

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Poulomi Chatterjee, Abhay Nirgude

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Poulomi Chatterjee, Abhay Nirgude

Drafting of the manuscript: Poulomi Chatterjee, Abhay Nirgude

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Poulomi Chatterjee, Abhay Nirgude

Supervision: Poulomi Chatterjee, Abhay Nirgude

References

- 1.Assessment of magnitude and determinants of overweight and obesity among school going adolescents of rural field practice area of the medical college, Hassan, Karnataka. Praveen G, Subhashini KJ. Int J Adv Commun Med. 2019;2:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and nutritional assessment in schoolchildren from mountainous areas of Argentinean Northwest. De Piero AJ, Rossi MC, Bassett MN, Samman NC. J Clin Nutr Diet. 2017;3:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The future role of the United States in global health: emphasis on cardiovascular disease. Fuster V, Frazer J, Snair M, Vedanthan R, Dzau V. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:3140–3156. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Investing in global health for our future. Dzau V, Fuster V, Frazer J, Snair M. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1292–1296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1707974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutritional status and growth centiles using anthropometric measures of school-aged children and adolescents from Multan district. Shehzad MA, Khurram H, Iqbal Z, Parveen M, Shabbir MN. Arch Pediatr. 2022;29:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2021.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Impacts of school nutrition interventions on the nutritional status of school-aged children in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pongutta S, Ajetunmobi O, Davey C, Ferguson E, Lin L. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030589. Nutrients. 2022;14:589–604. doi: 10.3390/nu14030589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Analysis of key nutrition indicators based on National Family Health Survey, NFHS 4 (2015-16) and NFHS 5 (2019-2021) Bhatia N, Rathi K, Arora C, et al. https://osf.io/r9ybf Niti Aayog. 2016:1–148. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Effects of a nutritional intervention using pictorial representations for promoting knowledge and practices of healthy eating among Brazilian adolescents. Fonseca LG, Bertolin MN, Gubert MB, da Silva EF. PLoS One. 2019;14:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A multicomponent, school-based intervention, the shaping healthy choices program, improves nutrition-related outcomes. Scherr RE, Linnell JD, Dharmar M, et al. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/pii/S1499404616309617. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adolescent self-efficacy for diet and exercise following a school-based multicomponent lifestyle intervention. Efthymiou V, Charmandari E, Vlachakis D, Tsitsika A, Pałasz A, Chrousos G, Bacopoulou F. Nutrients. 2021;14:97–110. doi: 10.3390/nu14010097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sustained impact of the "Healthy Habits, Healthy Girls - Brazil" school-based randomized controlled trial for adolescents living in low-income communities. Leme AC, Baranowski T, Thompson D, Nicklas T, Philippi ST. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A study to assess the effectiveness of a nutrition education session using flipchart among school-going adolescent girls. Raikar K, Thakur A, Mangal A, Vaghela JF, Banerjee S, Gupta V. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:183. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_258_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long-term effects of comprehensive school health on health-related knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, health behaviours and weight status of adolescents. Ofosu NN, Ekwaru JP, Bastian KA, Loehr SA, Storey K, Spence JC, Veugelers PJ. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:515. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5427-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The effect of comprehensive intervention for childhood obesity on dietary diversity among younger children: evidence from a school-based randomized controlled trial in China. Xu H, Ecker O, Zhang Q, et al. PLoS One. 2020;15:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Effect of the multicomponent healthy high school intervention on meal frequency and eating habits among high school students in Denmark: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Duus KS, Bonnesen CT, Rosing JA, et al. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022;19:12. doi: 10.1186/s12966-021-01228-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention for prevention of obesity in primary school children in China: a cluster randomized clinical trial. Liu Z, Gao P, Gao AY, et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:0. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.School-based nutrition education to improve children and their mothers’ knowledge on food and nutrition in rural areas of the Philippines. Glorioso IG, Gonzales MS, Malit AM. Mal J Nutr. 2020;26:189–201. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Group-based educational inequalities in India: Have major education policy interventions been effective? Varughese AR, Bairagya I. Int J Educ Dev. 2020;73:102159–102174. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Effect of an education program on nutrition knowledge, attitudes toward nutrition, diet quality, lifestyle, and body composition in Polish teenagers. The ABC of healthy eating project: design, protocol, and methodology. Hamulka J, Wadolowska L, Hoffmann M, Kowalkowska J, Gutkowska K. Nutrients. 2018;10:1439–1462. doi: 10.3390/nu10101439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Impacts of a school-based intervention that incorporates nutrition education and a supportive healthy school canteen environment among primary school children in Malaysia. Teo CH, Chin YS, Lim PY, Masrom SA, Shariff ZM. Nutrients. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/nu13051712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Impact of health and nutrition education programmes on nutritional status and dietary pattern of adolescent girls. Anand D, Anuradha RK. https://eprajournals.com/IJSR/article/2120/abstract Int J Res Dev. 2020;5:332–342. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and nutrition education against overweight in school-age children: a scoping review of progress in Spanish-speaking countries. Quintero AL, Ortega L, Fontes F, et al. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202201.0212/v1 2022:2–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.App based education programme to reduce salt intake (AppSalt) in schoolchildren and their families in China: parallel, cluster randomised controlled trial. He FJ, Zhang P, Luo R, et al. BMJ. 2022;376:0. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-066982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The comparison of the effects of different nutrition education methods on nutrition knowledge level in high school students. Aydın S, Özkaya H, Özbekkangay E, Günalan E, Kaya Cebioğlu İ, Okan Bakır B. Acıbadem Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi. 2022;13:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pediatric adapted liking survey (PALS) with tailored nutrition education messages: application to a middle school setting. Hildrey R, Karner H, Serrao J, Lin CA, Shanley E, Duffy VB. Foods. 2021;10:579–597. doi: 10.3390/foods10030579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Effectiveness and acceptability of a novel school-based healthy eating program among primary school children in urban Sri Lanka. Seneviratne SN, Sachchithananthan S, Gamage PS, Peiris R, Wickramasinghe VP, Somasundaram N. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:2083. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Effect of educational intervention program regarding knowledge, attitude, and habits of junk food among primary school students. Elbastawey S, El Emam Hafeze Elemam F, Esmat MH, Kamel AN. Egyptian J Health Care. 2022;13:487–501. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Impact of a one-year school-based teacher-implemented nutrition and physical activity intervention: main findings and future recommendations. Habib-Mourad C, Ghandour LA, Maliha C, Awada N, Dagher M, Hwalla N. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:256. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8351-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.School-based intervention programs for preventing obesity and promoting physical activity and fitness: a systematic review. Yuksel HS, Şahin FN, Maksimovic N, Drid P, Bianco A. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:347–367. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A scoping review of peer-led physical activity interventions involving young people: theoretical approaches, intervention rationales, and effects. Christensen JH, Elsborg P, Melby PS, Nielsen G, Bentsen P. Youth Soc. 2021;53:811–840. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Effects of circuit training or a nutritional intervention on body mass index and other cardiometabolic outcomes in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. Seo YG, Lim H, Kim Y, et al. PLoS One. 2021;16:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health education through football (soccer): the '11 for health' programme as a success story on implementation: learn, play and have fun! Thornton JS, Dvorak J, Asif I. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:885–886. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-103922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gamification for the improvement of diet, nutritional habits, and body composition in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Suleiman-Martos N, García-Lara RA, Martos-Cabrera MB, Albendín-García L, Romero-Béjar JL, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Gómez-Urquiza JL. Nutrients. 2021;13:2478–2494. doi: 10.3390/nu13072478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Effects of a school-based intervention on physical activity, sleep duration, screen time, and diet in children. Tapia-Serrano MA, Sevil-Serrano J, Sánchez-Oliva D, Vaquero-Solís M, Sánchez-Miguel PA. Rev de Psicodidactica. 2022;27:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The effectiveness of a high-intensity interval games intervention in schoolchildren: a cluster-randomized trial. Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Soriano-Cano A, Garrido-Miguel M, et al. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;32:765–781. doi: 10.1111/sms.14113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Results of a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a peer-led school-based intervention to increase the physical activity of adolescent girls (PLAN-A) Sebire SJ, Jago R, Banfield K, et al. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:50. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0682-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on specific academic skills of school students. Loturco I, Montoya NP, Ferraz MB, Berbat V, Pereira LA. Educ Sci. 2022;12:134–148. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tackling childhood obesity through a school-based physical activity programme: a cluster randomised trial. Santina T, Beaulieu D, Gagné C, Guillaumie L. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2021;19:342–358. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainment of health behaviour interventions in schools and childcare services: a systematic review. Shoesmith A, Hall A, Wolfenden L, et al. Implement Sci. 2021;16:62. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01134-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Effectiveness of a school-based intervention on knowledge, attitude and practice on healthy lifestyle and body composition in Malaysian adolescents. Sharif Ishak SI, Chin YS, Mohd Taib MN, Chan YM, Mohd Shariff Z. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:122. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Impact of lifestyle intervention programs for children and adolescents with overweight or obesity on body weight and selected cardiometabolic factors-a systematic review. Bondyra-Wiśniewska B, Myszkowska-Ryciak J, Harton A. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2061–2085. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18042061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Water wins, communication matters: school-based intervention to reduce intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and increase intake of water. Kamin T, Koroušić Seljak B, Fidler Mis N. Nutrients. 2022;14:1346–1357. doi: 10.3390/nu14071346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Impact of a behaviourally focused nutrition education intervention on attitudes and practices related to eating habits and activity levels in Indian adolescents. Moitra P, Madan J, Verma P. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:2715–2726. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Effectiveness of nutritional strategies on improving the quality of diet of children from 6 to 12 years old: a systematic review. Andueza N, Navas-Carretero S, Cuervo M. Nutrients. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/nu14020372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Improving children's diet: approach and progress. Ramakrishnan U, Webb Girard A. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2020;93:25–38. doi: 10.1159/000503354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Childhood obesity and its associated factors among school children in Udupi, Karnataka, India. Gautam S, Jeong HS. J Lifestyle Med. 2019;9:27–35. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2019.9.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Effects of preventive nutrition interventions among adolescents on health and nutritional status in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Salam RA, Das JK, Irfan O, Ahmed W, Sheikh SS, Bhutta ZA. Campbell Syst Rev. 2020;16:0. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The impact of nutritional interventions on child health and cognitive development. Bommer C, Mittal N, Vollmer S. Annu Rev Resour Econ. 2020;12:345–366. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scope and quality of Cochrane reviews of nutrition interventions: a cross-sectional study. Naude CE, Durao S, Harper A, Volmink J. Nutr J. 2017;16:22. doi: 10.1186/s12937-017-0244-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Micha R, Mannar V, Afshin A, et al. 2020. 2020 Global nutrition report: action on equity to end malnutrition. [Google Scholar]

- 51.A school-based intervention improved dietary intake outcomes and reduced waist circumference in adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ochoa-Avilés A, Verstraeten R, Huybregts L, et al. Nutr J. 2017;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12937-017-0299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52."Wellness Champions for Change," a multi-level intervention to improve school-level implementation of local wellness policies: study protocol for a cluster randomized trial. Lane HG, Deitch R, Wang Y, et al. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;75:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.School-based secondary prevention of overweight and obesity among 8- to 12-year old children: design and sample characteristics of the SNAPSHOT trial. Kubik MY, Fulkerson JA, Sirard JR, et al. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;75:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strength exercises during physical education classes in secondary schools improve body composition: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ten Hoor GA, Rutten GM, Van Breukelen GJ, et al. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:92. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0727-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Protocol paper for the Movimente school-based program: a cluster-randomized controlled trial targeting physical activity and sedentary behavior among Brazilian adolescents. Silva KS, Silva JA, Barbosa Filho VC, Santos PC, Silveira PM, Lopes MV, Salmon J. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:0. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.School-based obesity interventions in the metropolitan area of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil: pooled analysis from five randomised studies. Rodrigues RD, Hassan BK, Sgambato MR, et al. Br J Nutr. 2021;126:1373–1379. doi: 10.1017/S0007114521000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Effectiveness of a school-based nutrition education program on waist circumference and dietary behavior among overweight adolescents in Puducherry, India. Ponnambalam S, Palanisamy S, Singaravelu R, Arambakkam Janardhanan H. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11:323. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_413_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Long-term dietary and physical activity interventions in the school setting and their effects on BMI in children aged 6-12 years: meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Cerrato-Carretero P, Roncero-Martín R, Pedrera-Zamorano JD, et al. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:396–410. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9040396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Comparing peer-led and adult-led education to promote a healthy diet among Turkish school children. Haney MÖ, Yeşiltepe A. Eur J Ther. 2017;23:146–151. [Google Scholar]

- 60.School-based nutrition education intervention using social cognitive theory for overweight and obese Iranian adolescent girls: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Bagherniya M, Sharma M, Mostafavi Darani F, et al. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2017;38:37–45. doi: 10.1177/0272684X17749566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Impact of a three-year obesity prevention study on healthy behaviors and BMI among Lebanese schoolchildren: findings from Ajyal Salima program. Habib-Mourad C, Ghandour LA, Maliha C, Dagher M, Kharroubi S, Hwalla N. Nutrients. 2020;12:2687–2700. doi: 10.3390/nu12092687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Changes in sedentary and active lifestyle, diet quality and body composition nine months after an education program in Polish students aged 11⁻12 years: report from the ABC of healthy eating study. Wadolowska L, Hamulka J, Kowalkowska J, et al. Nutrients. 2019;11:331–346. doi: 10.3390/nu11020331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]