SUMMARY

Tuft cells in mucosal tissues are key regulators of type 2 immunity. Here we examined the impact of the microbiota on tuft cell biology in the intestine. Succinate induction of tuft cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells was elevated with loss of gut microbiota. Colonization with butyrate-producing bacteria or treatment with butyrate suppressed this effect and reduced intestinal histone deacetylase activity. Epithelial-intrinsic deletion of the epigenetic-modifying enzyme HDAC3 inhibited tuft cell expansion in vivo and impaired type 2 immune responses during helminth infection. Butyrate restricted stem cell differentiation into tuft cells, and inhibition of HDAC3 in adult mice and human intestinal organoids blocked tuft cell expansion. Collectively, these data define a HDAC3 mechanism in stem cells for tuft cell differentiation that is dampened by a commensal metabolite, revealing a pathway whereby the microbiota calibrate intestinal type 2 immunity.

Keywords: tuft cell, stem cell, intestine, microbiota, type 2 immunity, epigenetics, HDAC3, butyrate, development, organoid

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Tuft cells are central regulators of type 2 immunity in the intestine. Eshleman et al. reveal that commensal bacterial-derived butyrate restricts stem cell development into tuft cells through the epigenetic-modifying enzyme HDAC3. The microbiota can therefore direct tuft cell numbers in the intestine to fine-tune mucosal immunity.

INTRODUCTION

More than three billion individuals worldwide suffer from helminth infections or allergic diseases.1 Type 2 immunity is critical for host protection against pathogenic helminths. However, allergic disorders are induced and sustained by pathologic type 2 immune responses.2 Therefore, deciphering the mechanisms that direct type 2 immunity is needed to guide effective approaches to prevent or treat these highly prevalent conditions.

Tuft cells are secretory epithelial cells that are essential for initiating and maintaining type 2 immunity in the intestine. Furthermore, mice deficient in tuft cells are highly susceptible to helminth infection3–5 and models of inflammatory bowel disease.6–8 Intestinal tuft cells sense luminal signals and are dominant producers of the type 2 cytokine, IL-25.4 Tuft cell derived-IL-25 activates immune cells, including CD4+ Th2 cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), to produce classical type 2 effector cytokines, ultimately leading to helminth clearance.9–13 In addition, the type 2 cytokine IL-13 stimulates changes to the intestinal epithelium, including tuft cell differentiation.3–5 Therefore, tuft cells drive a feedforward loop with local immune cells to promote their own lineage differentiation and anti-parasitic immunity, emphasizing the importance of tuft cells in sustaining type 2 immunity. Although the factors necessary for driving tuft cell hyperplastic response are being investigated, the central regulatory mechanisms controlling tuft cell development and function remain poorly understood.

The trillions of microbes that reside in the intestinal tract, termed the microbiota, are essential for calibrating mammalian immune responses. Increasing evidence suggests that the intestinal microbiota exert strong regulatory effects on type 2 immune responses.2,14,15 Further, rising rates of inflammatory diseases and allergic reactions are associated with changes in microbiota composition and diversity.14,15 Directly demonstrating microbial restriction of type 2 immune responses, germ-free (GF) and antibiotic-treated mouse models exhibit elevated type 2 cytokines, increased type 2 effector cells, and enhanced susceptibility to anaphylaxis and allergic responses.14,15 In addition, colonization of mice with microbiota from healthy children can protect GF mice from allergic anaphylaxis, whereas this does not occur when mice are colonized with microbiota from food allergy patients16, suggesting that specific commensal microbes dampen type 2 immunity. While tuft cells are essential for controlling type 2 immunity, how the microbiota or microbiota-derived signals regulate tuft cells is not well understood.

Mechanisms beyond canonical pattern recognition receptors are increasingly appreciated as important mediators between the intestinal microbiota and host. For instance, cues derived from the microbiota can influence transcriptional programs of mammalian cells through epigenetic mechanisms.17,18 Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are a class of epigenetic-modifying enzymes that control gene expression in part through removal of acetyl groups from lysine residues on histones. Epithelial HDAC3 is sensitive to the microbiota and regulates basal intestinal epithelial and immune cell homeostasis, as well as, susceptibility to bacterial infection and diet-induced obesity.19–26 Here we report that short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing commensal bacteria limited tuft cell-induced type 2 immune responses. The SCFA butyrate constrained tuft cell development in both mice and humans through inhibition of HDAC3. Epithelial-intrinsic HDAC3 expression was required for activation of the tuft cell-ILC2 pathway and promoted pathogen clearance of the IL-13-sensitive helminth, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Furthermore, butyrate and butyrate-producing commensal bacteria epigenetically restricted tuft cell differentiation, and targeted loss of HDAC3 within intestinal stem cells blocked tuft cell differentiation and downstream ILC2 responses. Taken together, these findings reveal an epigenetic pathway in stem cells by which microbiota regulate tuft cell development and type 2 immune responses.

RESULTS

Tuft cell expansion in the intestine is suppressed by microbiota-derived butyrate.

Succinate increases tuft cell numbers, promotes IL-25 expression, and activates type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), in a tuft cell-dependent manner.27–30 Therefore, to determine how commensal microbes influence tuft cell-dependent type 2 immunity, succinate was administered to germ-free (GF) and conventionally-housed (CNV) microbiota-replete mice. CNV mice exhibited reduced tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 1A and 1B) and decreased intestinal ILC2s relative to GF mice (Figure 1C, Figure S1A), suggesting that the microbiota suppress tuft cell-dependent immune responses. To identify types of bacteria that may impact tuft cell responses, mice were treated with the antibiotic vancomycin to deplete Gram-positive bacterial species. Similar to GF mice, vancomycin-treatment increased intestinal tuft cells (Figures 1D and 1E) and ILC2s (Figure 1F) in response to succinate stimulation, suggesting that vancomycin-sensitive bacterial strains can inhibit tuft cell-dependent immunity. Vancomycin depletes Clostridiales bacterial families and reduces luminal concentrations of the SCFA, butyrate.31 Thus, to investigate whether SCFA-producing bacteria influence tuft cell-dependent immunity, GF mice were mono-associated with the butyrate producer Faecalibacterium prausnitizii. While F. prausnitizii largely colonizes the large intestine, F. prausnitizii is reported in the human ileum32 and was also present in the ileum of mono-associated and CNV mice (Figures S1B–D). Colonization with F. prausnitizii suppressed succinate-induced tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 1G and 1H) and downstream ILC2s (Figure 1I) relative to GF mice. Gas-chromatography mass spectrometry analysis confirmed that mono-association with F. prausnitizii increased luminal concentration of butyrate compared to GF controls (Figure 1J). Taken together, these data indicate that butyrate-producing commensal bacteria can dampen tuft cell-dependent type 2 immunity in the intestine.

Figure 1. Tuft cell expansion in the intestine is suppressed by microbiota-derived butyrate.

(A) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green) in ileum, (B) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells and (C) ILC2s by flow cytometry in GF and CNV mice treated with succinate for 7 days. (D) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in ileum, (E) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells and (F) ILC2s by flow cytometry from control and vancomycin-treated mice receiving succinate for 7 days. (G) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in ileum, (H) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells and (I) ILC2s by flow cytometry from GF and F. prausnitizii mono-colonized mice for 14 days then treated with succinate for 7 days. (J) Fecal concentration of butyrate in GF and F. prausnitizii mono-colonized mice. (K) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in ileum, (L) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells, and (M) ILC2s by flow cytometry from WT mice treated with butyrate for 7 days. (N) Fluorescence staining, (O) quantification of DCLK1+ tuft cells per organoid, and (P) tuft cell-enriched gene expression by RNA-sequencing of WT organoids stimulated with vehicle (veh) or butyrate for 24 hrs, then treated with IL-13 for 72 hrs. Scale bars, 50μM. Tuft cells gated Live, CD45−, EpCAM+, DCLK1+. ILC2s gated Live, CD45+, Lineage (CD4, CD8a, CD11b, CD11c, B220, Ly6G)−, CD90.2+, CD127+, Sca-1+, KLRG1+. Data are representative of three independent experiments, 3-5 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

To directly test whether butyrate impacts tuft cell-dependent immunity, mice were supplemented with butyrate in their drinking water. Butyrate reduced tuft cells (Figures 1K and 1L) and ILC2s (Figure 1M). Global analyses for histone acetylation (H3K9Ac) in IECs revealed increased and decreased histone acetylation at genes across diverse and essential pathways in the ileum of mice due to butyrate administration (Figures S2A–C). These included histone acetylation enrichment in pathways for protein kinase activity, transcriptional regulation, intracellular signal transduction, cellular response to cytokines, stem cell differentiation, and stem cell population maintenance (Figure S2C), and decreased histone acetylation at genes linked to transmembrane transport, cell cycle, EGFR and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathways (Figure S2C). While these data highlight epithelial sensitivity to butyrate, these pathways reflect an integrated outcome of a number of transcriptional networks and cell-extrinsic regulation.

Therefore, to determine the epithelial-intrinsic effects of butyrate on tuft cell immune regulation, intestinal epithelial organoid cultures were derived from the intestine of wild-type mice. Intestinal organoids stimulated with the type 2 cytokine, IL-13, demonstrated increased tuft cells (Figures 1N and 1O). In contrast, organoids treated with butyrate exhibited decreased basal tuft cell numbers and diminished IL-13-induced tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 1N and 1O). In addition to protein characterization, global transcriptional analyses revealed that IL-13 induced tuft cell-associated genes in intestinal organoids, however butyrate blocked IL-13 induction of the tuft cell transcriptional signature (Figure 1P). In contrast, in the presence of IL-22 and IFNγ, butyrate slightly increased expression of target genes Reg3g and Ciita, respectively (Figures S3A and S3B). Thus, while butyrate reduced tuft cell hyperplasia in response to IL-13 (Figures 1N–P), this does not reflect broad resistance to cytokine stimulation. Together, these data demonstrate that commensal microbial colonization, and specifically the microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate, can shape tuft cell-dependent type 2 immunity.

Butyrate controls tuft cell dynamics through histone deacetylase 3.

Similar to the colon22, basal HDAC activity was elevated in IECs isolated from the ileum of CNV mice, relative to GF mice (Figure S4A). Consistent with increased HDAC activity, CNV mice exhibited a trend toward increased tuft cells compared to GF mice during homeostatic conditions (Figure S4B). However, butyrate itself decreased HDAC activity (Figure S4C)22,24 and colonization of GF mice with the butyrate-producing commensal F. prausnitizii alone reduced epithelial HDAC activity (Figure S4D) and decreased homeostatic tuft cell numbers (Figure S4E). Further, F. prausnitizii, as well as F. prausnitizii-conditioned media that is devoid of the bacteria, both reduced epithelial HDAC activity (Figures S4F and S4G) in intestinal organoids, indicating a direct effect of F. prausnitizii-produced metabolites on HDAC activity.

HDAC3 is a potent histone deacetylase24,33 that incorporates microbiota-derived signals to maintain intestinal homeostasis.19,22 Thus, to determine whether the butyrate-producer F. prausnitizii repressed succinate-induced tuft cell immunity by inhibition of epithelial HDAC3, HDAC3-sufficient (HDAC3FF) and iEC-deficient (HDAC3ΔIEC) mice derived under GF conditions were mono-associated with F. prausnitizii. F. prausnitizii reduced succinate-induced tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 2A and 2B) and suppressed ILC2 responses (Figure 2C) in HDAC3FF, compared to GF HDAC3FF controls. However, succinate was unable to promote tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 2A and 2B) or expansion of intestinal ILC2s in GF-HDAC3ΔIEC mice (Figure 2C). Furthermore, tuft cells and ILC2s were not affected in F. prausnitizii mono-colonized HDAC3ΔIEC mice (Figures 2A–2C), supporting that F. prausnitizii-induced suppression of tuft cells is mediated by HDAC3. To next directly test whether butyrate regulates tuft cell development through HDAC3, organoids were derived from HDAC3FF and inducible Villin-cre mice (HDAC3ΔIEC-IND) (Figure 2D), in which tamoxifen treatment decreased Hdac3 expression in HDAC3ΔIEC-IND organoids, but not tamoxifen treated HDAC3FF controls (Figure 2E). Butyrate inhibited tuft cell-associated genes including the critical transcription factor, Pou2f3, and tuft cell marker, Dclk1, in control organoids (Figures 2F and 2G). Consistent with this expression profile, tuft cell numbers were reduced in butyrate treated control organoids (Figures 2H and 2I). Loss of HDAC3 reduced basal tuft cell gene expression and tuft cell numbers (Figures 2F–2I). Consistent with previous studies,22,34 butyrate and HDAC3 deficiency reduced basal organoid size (Figure 2H). Butyrate was unable to further suppress tuft cells in HDAC3-depleted organoids (Figures 2H and 2I), however given that tuft cell numbers are already low in organoids lacking HDAC3, this may reflect the limit of detection. In complimentary expression analyses, butyrate did not further decrease expression of tuft cell-associated genes in cells lacking HDAC3 (Figures 2F and 2G). These data collectively suggest that butyrate suppresses the tuft cell program via HDAC3 inhibition, and that HDAC3 is required for tuft cell homeostasis.

Figure 2. Butyrate controls tuft cell dynamics through histone deacetylase 3.

(A) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green) in ileum, (B) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells and (C) ILC2s by flow cytometry in GF and F. prausnitizii mono-associated HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC mice stimulated with succinate. Tuft cells gated Live, CD45−, EpCAM+, DCLK1+. ILC2s gated Live, CD45+, Lineage (CD4, CD8a, CD11b, CD11c, B220, Ly6G)−, CD90.2+, CD127+, Sca-1+, KLRG1+. (D) Experimental diagram. (E) mRNA expression of Hdac3, (F) Pou2f3, and (G) Dclk1, and (H) fluorescence staining and (I) quantification of tufts cells per murine organoid treated with tamoxifen (4-OHT) +/− butyrate. Scale bars, 50μM. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, 3-4 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ns=not significant.

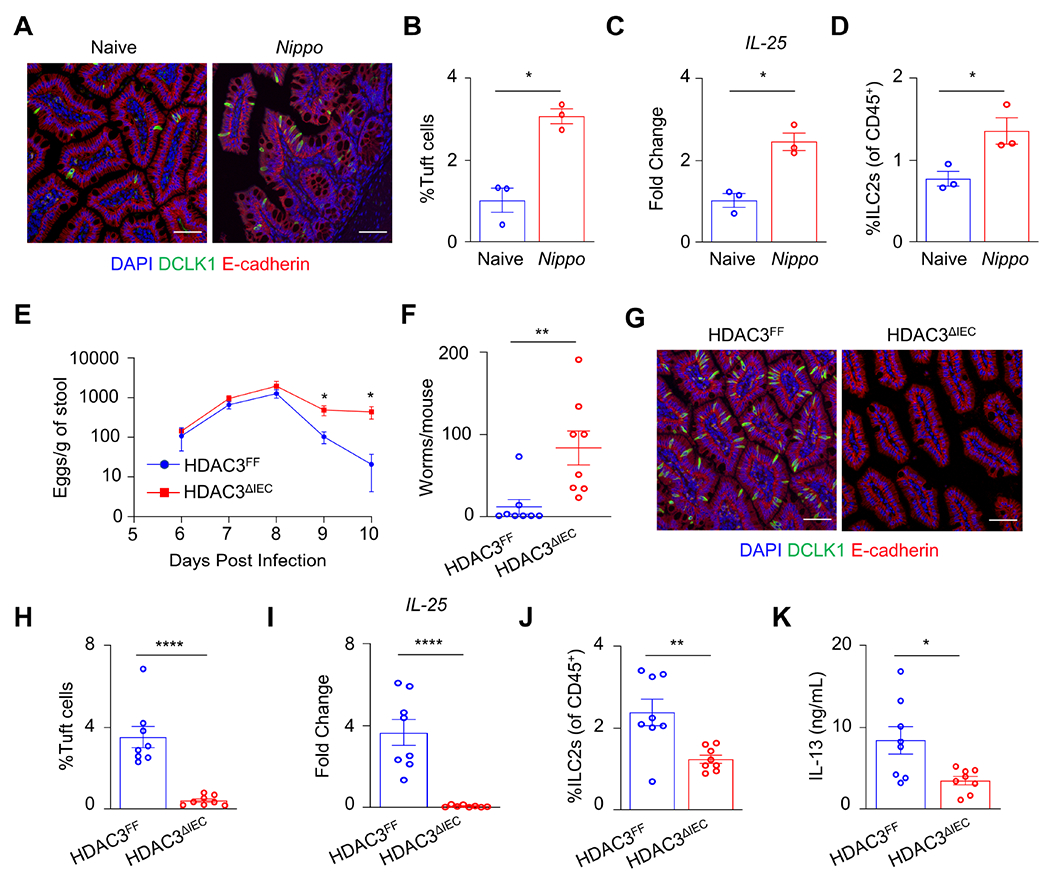

Epithelial HDAC3 directs intestinal type 2 immunity and effective worm clearance.

Tuft cells are essential for initiating and sustaining type 2 immune responses to helminth infection and promoting worm clearance.3–5 Consistent with this work, we found that infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis enhanced tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 3A and 3B), epithelial IL-25 expression, and intestinal ILC2s (Figures 3C and 3D). Loss of IEC-intrinsic HDAC3 expression resulted in elevated intestinal N. brasiliensis egg counts (Figure 3E). Furthermore, several HDAC3FF mice cleared the infection by day 10, while HDAC3ΔIEC mice retained high worm burdens (Figure 3F), indicating that epithelial HDAC3 promotes effective clearance. Intestinal tuft cell numbers increased in response to N. brasiliensis infection in control mice (Figures 3G and 3H). However, N. brasiliensis-infected HDAC3ΔIEC mice failed to demonstrate this tuft cell expansion (Figures 3G and 3H). Consistent with a lack of helminth-induced tuft cell hyperplasia, downstream IL-25 (Figure 3I), ILC2s (Figure 3J), and IL-13 responses were impaired in HDAC3ΔIEC mice (Figure 3K). Collectively, these data support that epithelial expression of HDAC3 is necessary for effective type 2-driven tuft cell development.

Figure 3. Epithelial HDAC3 directs intestinal type 2 immunity and effective worm clearance.

(A) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green), (B) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells by flow cytometry, (C) mRNA expression of IL-25 in SI IECs, and (D) frequency of ILC2s in ileum of WT mice naive and 7 days post-N. brasiliensis infection. (E) Fecal N. brasiliensis egg counts and (F) intestinal N. brasiliensis worm counts at day 10 in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC mice infected with N. brasiliensis. (G) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in ileum, (H) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells by flow cytometry, (I) mRNA expression of IL-25 from SI IECs, relative to naïve controls, (J) frequency of lamina propria ILC2s, and (K) serum concentration of IL-13 in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC mice 10 days post N. brasiliensis infection. Tuft cells gated Live, CD45−, EpCAM+, DCLK1+. ILC2s gated Live, CD45+, lineage (CD4, CD8a, CD11b, CD11c, B220, Ly6G)−, CD90.2+, CD127+, Sca-1+, KLRG1+. Scale bars, 50μM. Data are representative of two independent experiments, 4-8 mice per group, per timepoint. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Active regulation by HDAC3 is necessary for IL-13-induced tuft cell expansion.

To investigate whether expansion of tuft cells in the adult intestine reflect active regulation by HDAC3 in vivo, HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice were supplemented with succinate prior to HDAC3 loss to induce tuft cell hyperplasia, and then treated with either vehicle or tamoxifen. Mice that received vehicle-treatment displayed elevated succinate-induced tuft cell numbers (Figures 4A and 4B) and ILC2 responses (Figure 4C). However, mice treated with tamoxifen to delete epithelial HDAC3 exhibited complete loss of tuft cells and diminished ILC2s responses (Figures 4A–4C), indicating that active regulation by HDAC3 in vivo was required for tuft cell hyperplasia. To determine whether epithelial HDAC3 regulation of tuft cells affects responsiveness to IL-13, intestinal organoids were generated from HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice and treated with tamoxifen prior to IL-13 stimulation. IL-13 did not alter Hdac3 expression (Figure 4D) or deacetylase activity (Figure S5A). As expected, control organoids rapidly expanded tuft cells in response to IL-13 stimulation (Figures 4E and 4F). However, tamoxifen-induced loss of HDAC3 restricted IL-13-induced tuft cell hyperplasia (Figures 4E and 4F), revealing that epithelial HDAC3 actively regulates IL-13 induced tuft cell responses. Consistently, loss of epithelial HDAC3 inhibited induction of tuft cell genes, including Pou2f3 and Dclk1, in response to IL-13 (Figures 4G and 4H). IL-22 and IFNγ sensitive targets were similarly expressed, or even slightly elevated, between controls and HDAC3-depleted organoids (Figures S5B and S5C), indicating that other cytokine responses were not significantly reduced by loss of HDAC3.

Figure 4. Active regulation by HDAC3 is necessary for IL-13-induced tuft cell expansion.

(A) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green) in ileum, (B) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells and (C) ILC2s by flow cytometry in HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice treated with succinate for 5 days then given vehicle or tamoxifen 1x/day i.p. for 5 days, and harvested 5 days after the final dose. Tuft cells gated Live, CD45−, EpCAM+, DCLK1+. ILC2s gated Live, CD45+, lineage (CD4, CD8a, CD11b, CD11c, B220, Ly6G)−, CD90.2+, CD127+, Sca-1+, KLRG1+. (D) mRNA expression of Hdac3 in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC-IND organoids treated with tamoxifen (4-OHT) +/− IL-13. (E) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in organoids, (F) quantification of DCLK1+ tuft cells per organoid, (G) Pou2f3 and (H) Dclk1 mRNA expression in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC-IND organoids treated with 4-OHT +/− IL-13. Scale bars, 50μM. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, 3-4 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ns=not significant.

Human tuft cell differentiation is restricted by butyrate inhibition of HDAC3.

Our understanding of human tuft cell differentiation remains largely unknown. Thus, to next directly examine regulation of human tuft cells, we generated organoids from ileal endoscopic biopsies harvested from healthy non-IBD patients. IL-13 exposure promotes tuft cell differentiation in murine intestinal organoids, however whether this occurs in human-derived organoids is unclear. Basal tuft cells in ileal-derived human organoids were generally undetectable by immunofluorescence staining for the human tuft cell marker, p-EGFR (Figure 5A). IL-13 promoted tuft cell development in human intestinal organoids derived from multiple different patients (Figure 5A), suggesting similarities between human and murine tuft cell responses. Furthermore, butyrate blunted IL-13-induced tuft cell genes including POU2F3 and the tuft cell marker, TRPM5 (Figures 5B and 5C) and suppressed tuft cell responses to IL-13 in human organoids (Figure 5D). In addition, treatment with an HDAC3-specific inhibitor (HDAC3i: RGFP966) similarly reduced IL-13-induced tuft cell genes (Figures 5E and 5F) and tuft cell development in human organoids (Figure 5G). Tuft cell numbers remained low in the presence of both HDAC3i and butyrate (Figures 5H and 5I). Thus, similar to our murine findings, butyrate and HDAC3 inhibition limit tuft cell differentiation in the human intestine. Collectively, these data demonstrate that active regulation by HDAC3 controls IL-13-induced tuft cell hyperplastic responses in both mice and humans, suggesting a central role for HDAC3 in tuft cell progenitor cells.

Figure 5. Human tuft cell differentiation is restricted by butyrate inhibition of HDAC3.

(A) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells (p-EGFR+, green) in human crypt-derived intestinal organoids treated with IL-13. Scale bars, 50μM or 20μM for in-lay images. (B) mRNA expression of POU2F3 and (C) mRNA expression of TRPM5 in organoids treated +/− butyrate for 24 hrs then IL-13 for 72hrs, n=3 patients. (D) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in human intestinal organoids treated +/− butyrate for 24 hrs then IL-13 for 72hrs. (E) mRNA expression of POU2F3 and (F) mRNA expression of TRPM5 in organoids treated +/− HDAC3i (RGFP966) for 24 hrs then IL-13 for 72hrs, n=4 patients. (G) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in human intestinal organoids treated +/− HDAC3i (RGFP966) for 24 hrs then IL-13 for 72hrs. (H) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in human intestinal organoids treated with IL-13 +/− butyrate and/or HDAC3i. (I) Quantification of human p-EGFR+ tuft cells, n=4 patients. Data are from organoids derived from 3-4 different patients, each color in the panel represents distinct patients. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ns=not significant.

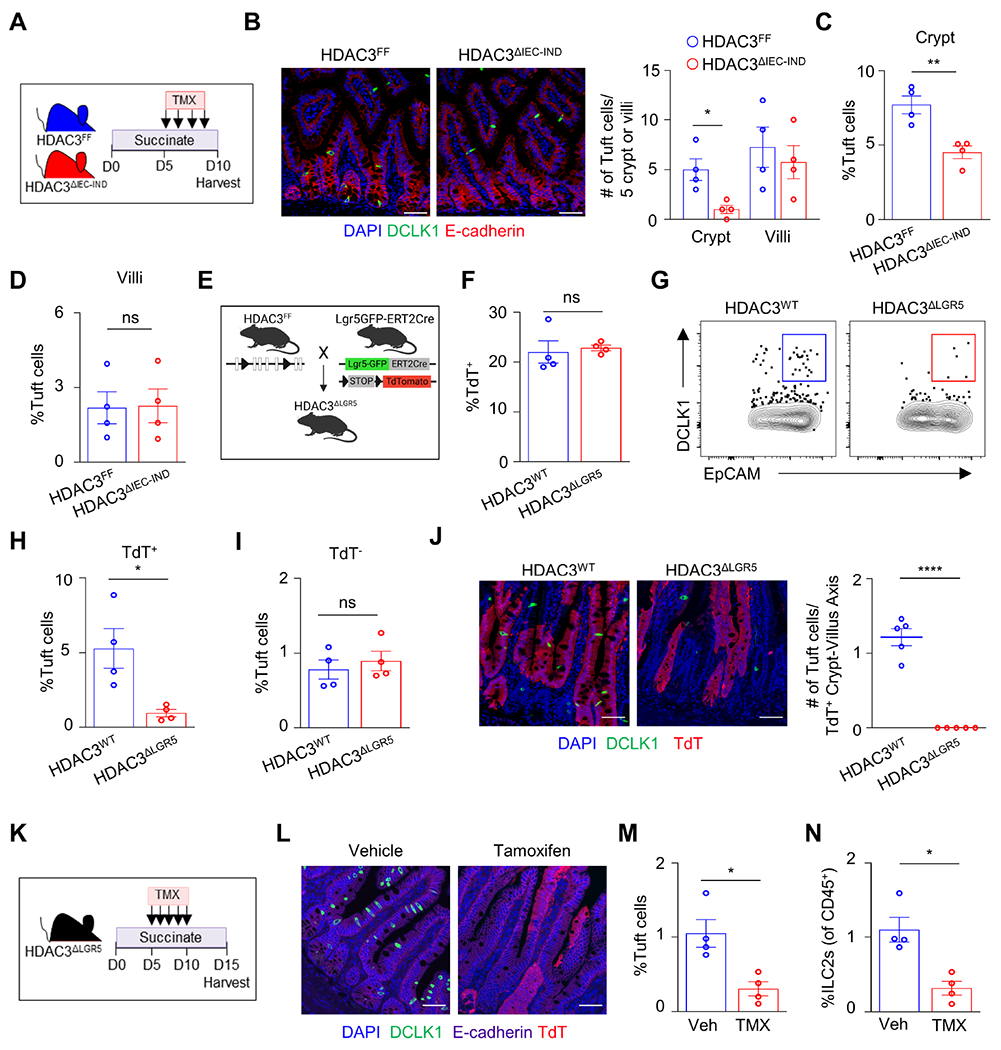

Stem cell-intrinsic HDAC3 promotes tuft cell differentiation.

Similar EdU incorporation and migration occurred in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC mice (Figure S6A), supporting that global IEC proliferation and transit are not affected by loss of HDAC3. Therefore, to assess the initial role of HDAC3, tuft cell hyperplasia was induced with succinate in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice, and then HDAC3 was depleted using tamoxifen (Figure 6A). Analyses 24 hrs later demonstrated that tuft cells were reduced in the crypts of HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice, compared to littermate HDAC3FF controls (Figures 6B and 6C). In contrast, villi retained similar levels of tuft cells between HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice, despite loss of HDAC3 after tuft cell differentiation (Figures 6B and 6D). These findings suggest that HDAC3 is necessary for tuft cell development, while tuft cell survival remains intact during this timeframe.

Figure 6. Stem cell-intrinsic HDAC3 promotes tuft cell differentiation.

(A) Experimental design. (B) Fluorescence staining and quantification of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green) per 5 crypt or 5 villi, and (C) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells by flow cytometry in the crypt or (D) villi-associated IECs from the ileum of HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice stimulated with succinate then treated with tamoxifen and harvested 24 hrs after final tamoxifen dose. (E) Diagram of HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice. (F) Frequency of TdTomato+ (TdT) cells in EpCAM+ gate. (G, H) Frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells from TdT+ gated cells and (I) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cell from TdT− gated cells in ileum of HDAC3WT and HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice. (J) Fluorescence staining and quantification of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green) in ileum in HDAC3WT and HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice. (K) Experimental design. (L) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells in ileum, (M) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells, and (N) frequency of ILC2s by flow cytometry in HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice treated with succinate for 5 days, then treated with vehicle or tamoxifen and harvested five days after the final dose as depicted in (K). Tuft cells gated Live, CD45−, EpCAM+, DCLK1+. ILC2s gated Live, CD45+, lineage (CD4, CD8a, CD11b, CD11c, B220, Ly6G)−, CD90.2+, CD127+, Sca-1+, KLRG1+. Scale bars, 50μM. Data are representative of three independent experiments, 3-5 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ns=not significant.

Lgr5+ intestinal epithelial stem cells (ISCs) continuously give rise to all differentiated IEC lineages, including tuft cells.4 To determine whether ISC expression of HDAC3 is required for tuft cell differentiation, mice were generated to specifically delete HDAC3 in Lgr5+-expressing ISCs (HDAC3ΔLGR5) with lineage-tracing TdTomato (TdT) downstream of a stop-flox codon (Figure 6E). Deletion of HDAC3 in Lgr5+ ISCs did not impact the overall frequency of TdT+ expressing cells (Figure 6F). However, HDAC3 loss in Lgr5+ ISCs blunted tuft cell numbers in TdT+ (Figures 6G and 6H), but not TdT− epithelial cells (Figure 6I), supporting that stem cell-intrinsic loss of HDAC3 impaired tuft cell development. While tuft cell differentiation was decreased in HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice (Figures 6G–J), similar goblet and Paneth cell numbers were present in the intestine of HDAC3WT and HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice (Figures S6B and S6C). To directly evaluate the active role of stem cell-intrinsic HDAC3 during induction of tuft cell hyperplasia, HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice were supplemented with succinate prior to HDAC3 depletion (Figure 6K). Tamoxifen-treated HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice had impaired tuft cell differentiation (Figures 6L and 6M) and reduced ILC2s (Figure 6N) compared to vehicle treated controls. Taken together, these findings highlight that stem cell-intrinsic HDAC3 regulation is necessary for inducing tuft cell differentiation.

Commensal bacteria epigenetically instruct tuft cell differentiation.

To identify targets through which HDAC3 controls tuft cell differentiation, H3K9Ac was assessed by ChIP-qPCR at the promoter of tuft cell regulatory genes. Loss of HDAC3 did not significantly alter basal H3K9Ac levels in the promoter of Atoh1, Pou2f3, and Pou2af2 (Figures S7A), suggesting HDAC3 may not directly deacetylate these sites. Mice with loss of Sprouty2 (Spry2), a negative regulator of EGFR and RTK signaling cascades, display increased tuft and goblet cells in the colon.35 To test its role in the ileum, we generated mice lacking Spry2 specifically in IECs by breeding floxed Spry2 mice (Spry2FF) to mice expressing Cre recombinase downstream of the villin promoter (Spry2ΔIEC). As in the colon35, Spry2ΔIEC mice demonstrated increased tuft cells in the ileum (Figures 7A and 7B), suggesting a similar role for Spry2 in limiting tuft cell development in the small intestine. Therefore, to begin to determine whether HDAC3 plays a role in the regulation of Spry2, we assessed H3K9Ac at the Spry2 promoter. H3K9Ac was elevated at the Spry2 promoter in IECs lacking HDAC3 relative to control IECs (Figure 7C), indicating that Spry2 may be a target of HDAC3. Consistent with this difference in histone acetylation, Spry2 expression was increased in mice lacking stem cell-intrinsic HDAC3 relative to controls (Figure 7D), supporting that HDAC3 epigenetically represses this suppressor of tuft cell differentiation.

Figure 7. Commensal bacteria epigenetically instruct tuft cell differentiation.

(A) Fluorescence staining of tuft cells (DCLK1+, green) and (B) frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells by flow cytometry in ileum of Spry2FF and Spry2ΔIEC mice. (C) Chip-qPCR for H3K9Ac in Spry2 promoter in HDAC3FF and HDAC3ΔIEC IECs. (D) mRNA expression of Spry2 in SI crypts from tamoxifen-treated HDAC3WT and HDAC3ΔLGR5 mice. (E) Frequency of DCLK1+ tuft cells by flow cytometry in ileum of Spry2FF and Spry2ΔIEC mice treated with butyrate for 7 days. (F) Chip-qPCR for Spry2 H3K9Ac and (G) mRNA expression in GF and F. prausnitizii mono-associated IECs. (H) Chip-qPCR for Spry2 H3K9Ac and (I) mRNA expression in murine intestinal organoids stimulated with butyrate for 96 hrs. (J) Chip-qPCR for H3K9Ac at hSprouty2 (SPRY2) promoter in human crypt-derived intestinal organoids treated with butyrate or HDAC3i (RGFP966) for 96 hrs, n=3 patients, each color in the panel represents distinct patients. (K) SPRY2 mRNA expression in human intestinal organoids treated with butyrate or HDAC3i (RGFP966) for 96 hrs, n=4 patients, each color in the panel represents distinct patients. Scale bars, 50μM. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, 3-4 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ns=not significant.

Given that butyrate suppressed tuft cells via HDAC3 inhibition (Figure 2), Spry2FF and Spry2ΔIEC mice were next treated with butyrate. Goblet cells were modestly elevated in the ileum of Spry2ΔIEC mice (Figures S7B and S7C), however butyrate did not alter goblet cells in either Spry2-sufficient or -deficient mice (Figure S7D). Therefore, Spry2-independent pathways can maintain goblet cell numbers in vivo in the presence of butyrate. Consistent with earlier findings (Figures 1K and 1L), butyrate decreased tuft cells in floxed Spry2-sufficient mice (Figure 7E). However, tuft cell numbers were not altered by butyrate in Spry2ΔIEC mice (Figure 7E), indicating that butyrate’s inhibitory effect on tuft cells is in part mediated via Spry2 expression. To directly examine how commensal microbes impact this pathway, GF mice and mice mono-associated with F. prausnitizii were compared. Similar to loss of HDAC3, F. prausnitizii colonization resulted in H3K9Ac enrichment at the Spry2 promoter (Figure 7F) and increased gene expression of Spry2 (Figure 7G). In addition, intestinal organoids stimulated with butyrate displayed H3K9Ac enrichment at the Spry2 promoter (Figure 7H) and increased Spry2 gene expression (Figure 7I). Butyrate and HDAC3i also led to H3K9Ac enrichment at the SPRY2 promoter in human intestinal organoids (Figure 7J), along with increased expression (Figure 7K). Thus, functional pathways are established in the human intestine by which microbiota-derived metabolites can epigenetically direct human tuft cell differentiation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified a pathway by which the microbiota calibrate intestinal tuft cell differentiation. Microbiota-derived butyrate limited IL-13-induced tuft cell hyperplasia and effective type 2 immune responses. HDAC3 is a nodal point between the intestinal microbiota and multiple physiologic processes in the intestine.19–26 Here we find that HDAC3 specifically in stem cells epigenetically altered the tuft cell suppressor gene, Spry2, and promoted tuft cell differentiation. F. prausnitizii and butyrate similarly changed the histone profile and expression of Spry2 and limited tuft cell differentiation in the ileum. This level of microbiota-host regulation also controlled tuft cell development in the human intestine, highlighting essential clinical implications for either limiting or promoting type 2 immunity. Tuft cell differentiation requires expression of the taste-cell specific transcription factor, Pou2F3.3,36–38 A Pou2F3 co-activator, Pou2af2, and its specific isoform usage is suggested to modulate homeostatic tuft cell development.39–41 The secretory lineage factors, ATOH1 and Sox4, are only partially required for tuft cell development, as deletion of either molecule results in partial or region-specific reduction in tuft cells.42–45 Goblet and Paneth cells were present in the intestine of mice lacking stem-cell intrinsic HDAC3, indicating that loss of HDAC3 in stem cells does not inhibit all secretory cell development. Neither succinate nor IL-13 could overcome HDAC3 deficiency to promote tuft cell differentiation or expansion. Therefore, these data highlight that HDAC3 regulation of stem cells is essential for the tuft cell lineage program.

Canonically, HDAC3 deacetylates histone targets to alter gene expression and cellular functions. HDAC3 classically suppresses gene expression of direct targets via histone deacetylation. Loss of ISC-intrinsic HDAC3 resulted in increased histone acetylation and elevated gene expression of the tuft cell suppressor, Spry2. Previous work demonstrates that basal Spry2 directly inhibits PI3K/Akt signaling, which allows GSK3β control of tuft cell differentiation.35,46,47 Our data indicate that HDAC3 inhibition increases Spry2 expression and histone acetylation, suggesting that HDAC3 may directly repress Spry2 transcription. Consistent with HDAC3 inhibition, F. prausnitizii colonization and butyrate also enhanced Spry2 expression and histone acetylation, supporting that microbiota-derived butyrate mechanistically limits tuft cell differentiation in part by decreasing HDAC3 activity at the Spry2 gene. Although goblet cells are sensitive to Spry2, our data suggest that Spry2-independent pathways maintain goblet cells in vivo in the presence of butyrate or HDAC3 depletion. Therefore, mechanisms regulating goblet cell homeostasis are not identical to tuft cells. Taken together, these new findings support that HDAC3 in the stem cell compartment uniquely directs tuft cell differentiation.

Our findings demonstrate global changes in epithelial histone acetylation with butyrate, reflecting an integrated outcome of a number of transcriptional networks. Butyrate exerts broad immunoregulatory effects and influences the development and function of the intestinal epithelium via SCFA-sensing receptors and/or direct inhibition of HDAC activity.48 Thus, it is expected that multiple HDAC3-dependent networks collectively impact butyrate regulation and that SCFA-sensing receptors may also play a role in tuft cell differentiation. Previous studies suggest that butyrate or other SCFAs, including propionate and acetate, may have little impact on tuft cell homeostasis in mouse models.27,29 However, the intestinal crypt structure can limit stem cell exposure to butyrate and other microbiota-derived factors.34 In organoids where crypt structure is diminished, butyrate inhibited tuft cell differentiation in both murine and human models. Given that the expression of the SCFA receptor FFAR3 is enriched in tuft cells27,29, it is possible that butyrate may further impact tuft cells via FFAR3 signaling in differentiated cells.

Beyond production of butyrate, the microbiota generate numerous other metabolites and factors that may positively regulate ISC function and tuft cell differentiation. In fact, basal HDAC activity is elevated in epithelial cells of CNV mice compared to GF controls22, indicating that under homeostatic conditions HDAC activity is calibrated by microbiota-derived factors that can counteract butyrate. Our current study demonstrates that stimulation of tuft cell differentiation is restricted in the ileum of CNV mice, relative to GF mice, suggesting that microbiota-host dynamics differ under type 2 conditions that promote tuft cell hyperplasia. Regulation of tuft cells in more proximal regions of the small intestine may differ because of relatively lower butyrate concentrations. It is also important to note that Tritrichomonas muris, the succinate-producing protist that promotes tuft cells, was not detected in CNV mice in our vivarium. Tuft cells are sensitive to HDAC-dependent and HDAC-independent mechanisms, so it is unlikely that HDAC activity alone dictates tuft cell numbers. Adding to this complexity, multiple microbial species have been shown to produce succinate, along with other metabolites that are sensed by the host.49 Thus, diverse microbial-derived signals are likely to synergistically or antagonistically fine-tune tuft cell development.

Microbiota composition is associated with the development of several chronic inflammatory diseases including allergy, asthma, and IBD. The findings described here reveal a central role for commensal bacterial-derived metabolites in epigenetically limiting type 2 intestinal immune responses through active regulation of tuft cell differentiation. In addition to the intestine, tuft cells exist in the lung, trachea, esophagus, stomach, thymus, pancreas, and biliary tract, and contribute to airway hypersensitivity.50–56 HDAC3 is expressed ubiquitously, and butyrate levels at extra-intestinal sites reflect microbiota colonization. Thus, it is plausible that butyrate regulation of HDAC3 may control tuft cell-dependent immune responses at distant tissue sites as well. Therefore, modulating this pathway, pharmacologically or through diet- or microbiota-based approaches, might be useful for treating pathologic inflammation across mucosal tissues.

Limitations of the Study

This study identified a central role for HDAC3 in stem cells for directing tuft cell differentiation. While F. prausnitizii and butyrate reduced tuft cells through this pathway, the outcome in the context of dynamic host and microbial signals may be more complex and remains to be elucidated. Furthermore, additional models will be needed to decipher the role of butyrate and HDAC3 in mature tuft cell function. HDAC3 impacts multiple transcriptional networks, so epigenetic regulation of a single gene is unlikely to be responsible for tuft cell programming. While ChIP-qPCR of bulk IECs suggest that HDAC3 may not alter basal H3K9Ac in the promoter of known regulators Pou2f3, Pou2af2, and Atoh1, global epigenetic analyses of intestinal stem cells will be necessary to identify enhancers and additional mechanisms. Examination of HDAC3 enrichment, in combination with these broader chromatin analyses, will enable discovery of direct regulatory sites across the genome of progenitor cells.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further Information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Theresa Alenghat (Theresa.Alenghat@cchmc.org).

Materials availability

Requests for reagents and resources generated in this study will be fulfilled by the lead contact.

Data and code availability

Sequencing data has been deposited at GEO and is publicly available. Accession numbers are listed in the key resource table.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-mouse CD326 (EpCAM), G8.8, BV711 | BD Bioscience | Cat # 563134 |

| anti-mouse CD45.2, 104, BUV395 | BD Bioscience | Cat # 564616 |

| anti-mouse GATA3, 16E10A23, APC | BioLegend | Cat # 653806 |

| anti-mouse KLRG-1, 2F1, APC-eFluor-780 | Invitrogen | Cat # 47-5893-82 |

| anti-mouse CD127, A7R34, PE-Cy7 | Invitrogen | Cat # 25-1271-82 |

| anti-mouse CD25, PC61, PE/Dazzle-594 | BioLegend | Cat # 102048 |

| anti-mouse SiglecF, E50-2440, PE | BD Bioscience | Cat # 552126 |

| anti-mouse CD4, RM4-5, PerCP-eFluor710 | Invitrogen | Cat # 46-0042-82 |

| anti-mouse CD8a, 53-6.7, PerCP-eFluor710 | Invitrogen | Cat # 46-0081-82 |

| anti-mouse CD45R (B220), RA3-6B2, PerCP-eFluor710 | Invitrogen | Cat # 46-0452-82 |

| anti-mouse Ly-6G, A8-Ly6g, PerCP-eFluor710 | Invitrogen | Cat # 46-9668-82 |

| anti-mouse CD11b, M1/70, PerCP-Cy5.5 | Invitrogen | Cat # 45-0112-82 |

| anti-mouse CD11c, N418, PerCP-Cy5.5 | Invitrogen | Cat # 45-0114-82 |

| anti-mouse Ly-6A/E (Sca-1), D7, Super Bright 645 | Invitrogen | Cat # 64-5981-82 |

| anti-mouse CD90.2 (Thy-1.2), 53-2.1, FITC | Invitrogen | Cat # 11-0902-82 |

| anti-mouse CD24, M1/69, APC-eFluor-780 | Invitrogen | Cat # 47-0242-82 |

| F(ab’)2-Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, APC | Invitrogen | Cat # 31984 |

| anti-DCAMKL1 (DCLK1) antibody | Abcam | Cat # ab31704 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor-488 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat # 711-545-152 |

| Donkey anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor-555 | Abcam | Cat # ab150110 |

| Donkey anti-Goat IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor-647 | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat # 705-605-147 |

| anti-human EGFR (phosphor-Y1068) antibody, EP774Y, Alexa Fluor-488 | Abcam | Cat # ab205827 |

| anti-mouse CD326 (EpCAM), G8.8, Alexa Fluor-594 | BioLegend | Cat # 118222 |

| mouse Anti-E-Cadherin, 6/E-Cadherin | BD Bioscience | Cat # 610182 |

| rabbit anti-MUC2 | Novus Biologicals | Cat # NBP1-31231 |

| rabbit anti-Lysozyme EC 3.2.1.17 | Agilent Dako | Cat # A0099 |

| goat anti-TdTomato | SICGEN | Cat # AB8181 |

| Anti-acetyl-Histone H3 (Lys9) Antibody | Millipore Sigma | Cat # 06-942 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Faecalibacterium prausnitizii | ATCC | Cat # 27766 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Nippostrongylus brasiliensis | Dr. Fred D. Finkelman, CCHMC | N/A |

| Patient-derived organoids | IBD Biorepository protocol at CCHMC | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Sodium succinate hexahydrate | Alfa Aesar | Cat # 41983 |

| Sodium butyrate | Sigma | Cat # 303410 |

| Vancomycin Hydrochloride | GoldBio | Cat # 1404-93-9 |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma | Cat # T5648 |

| Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) | Sigma | Cat # H7904 |

| Recombinant Murine IL-13 | PeproTech | Cat # 210-13 |

| Recombinant Murine IFNγ | BioLegend | Cat # 575302 |

| Recombinant Murine IL-22 | PeproTech | Cat # 210-22 |

| Recombinant Human IL-13 | PeproTech | Cat # 200-13 |

| HDAC3i (RGFP966) | Selleckchem | Cat # S7229 |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | Gibco | Cat # 12634-010 |

| HEPES (1M) | Gibco | Cat # 15630-080 |

| L-glutamine | HyClone | Cat # SH30034.01 |

| N2 Supplement | ThermoFisher | Cat # 17502048 |

| B27 Supplement | ThermoFisher | Cat # 17504044 |

| Recombinant Human EGF | R&D Systems | Cat # 236-EG |

| Recombinant Mouse EGF | R&D Systems | Cat # 2028-EG |

| Y-27632 dihydrochloride | Tocris | Cat # 1254 |

| SB 431542 | Selleckchem | Cat # S1067 |

| DAPT | Stem Cell | Cat # 72082 |

| IntestiCult Organoid Differentiation Medium (Human) | Stem Cell | Cat # 100-0214 |

| IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (Human) | Stem Cell | Cat # 100-0191 |

| Matrigel | Corning | Cat # 356237 |

| TrypLE Express | Gibco | Cat # 12605-028 |

| Collagenase/Dispase | Sigma | Cat # 11097113001 |

| Collagenase type I | Gibco | Cat # 17018-029 |

| Citrate Buffer, pH 6.0, 10×, Antigen Retriever | Sigma | Cat # C9999 |

| ibidi Mounting Medium | ibidi | Cat # 50001 |

| Paraformaldehyde 16% Aqueous Solution EM Grade | Electron Microscopy Science | Cat # 15710 |

| ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant | Invitrogen | Cat # P10144 |

| DAPI (4,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) | Sigma | Cat # D9542 |

| AlexaFluor-647-Phalloidin | Invitrogen | Cat # A22287 |

| Normal Donkey Serum (NDS) | Jackson ImmunoResearch | Cat # 017-000-121 |

| Protein G Dynabeads | Invitrogen | Cat # 10003D |

| Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix | Thermo Scientific | Cat # 4367659 |

| LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit | Invitrogen | Cat # L34957 |

| eBioscience™ Fixation/Permeabilization Diluent | Invitrogen | Cat # 00-5223-56 |

| eBioscience™ Fixation/Permeabilization Concentrate | Invitrogen | Cat # 00-5123-43 |

| eBioscience™ Permeabilization Buffer (10X) | Invitrogen | Cat # 00-8333-56 |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffer (100X Tris-EDTA Buffer, pH 9.0) | Abcam | Cat # ab93684 |

| Proteinase K | Thermo Scientific | Cat # EO0491 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | Qiagen | Cat # 51604 |

| RNeasy Mini RNA Kit | Qiagen | Cat # 74106 |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat # 23225 |

| DNase I, Amplification Grade | Invitrogen | Cat # 18068015 |

| Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat # AB1453A |

| Click-iT EdU Cell Proliferation Kit for Imaging, Alexa Fluor 488 dye | Invitrogen | Cat # C10337 |

| QIAquick PCR purification kit | Qiagen | Cat # 28006 |

| HDAC Activity Fluorometric Assay Kit | BioVision | Cat # K330-100 |

| Deposited data | ||

| ChIP-seq raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE249959 |

| RNA-seq raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE223822 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: WT: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | Jax: 000664 |

| Mouse: Villin-Cre: B6.Cg-Tg(Vil1-cre)997Gum/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Jax: 004586 |

| Mouse: Villin-CreERT2, B6.Cg-Tg(Vil1-cre/ERT2)23Syr/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Jax: 020282 |

| Mouse: Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2, B6.129P2-Lgr5tm1(cre/ERT2)Cle/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Jax: 008875 |

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Jax: 007909 |

| Mouse: HDAC3FF | M. Lazar, U Penn | Mullican et al.57 |

| Mouse: Sprouty2FF: Spry2tm1Mrt/Mmnc | MMRRC | 011469-UNC |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for ChIP-qPCR and RT-qPCR, see Table S1 | This paper | |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FlowJo Software | Treestar | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| NIS-elements software | Nikon | https://www.microscope.healthcare.nikon.com/products/software/nis-elements/viewer |

| ImageJ | Fiji | https://imagej.net/ij/ |

| Prism 9.5.0 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| DESeq2 | Love et al.69 | N/A |

| Bowtie2 | Langmead et al.68 | N/A |

| STAR Aligner | Dobin et al.71 | N/A |

| Picard tool | Broad Institute | N/A |

| Homer | Heinz et al.73 | N/A |

| EdgeR | Robinson et al.72 | N/A |

| IGV | Thorvaldsdóttir et al.75 | https://www.igv.org/ |

| Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery | Sherman et al.74 | david.ncifcrf.gov |

| Other | ||

| SX-8G IP-STAR | Diagenode | N/A |

| BD LSR Fortessa Flow Cytometer | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| S220 Focused-ultrasonicator | Covaris | N/A |

| Nikon A1 inverted confocal microscope | Nikon | N/A |

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Mice.

Conventionally-housed C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and maintained in our specific-pathogen free colony at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Germ-free (GF) mice were maintained in flexible isolators in the CCHMC Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility, fed autoclaved feed and water, and monitored for absence of microbes. HDAC3FF were generated as previously described57, and crossed to C57BL/6J-Villin-Cre58 (HDAC3ΔIEC), tamoxifen-inducible Villin-Cre59 (HDAC3ΔIEC-IND), and tamoxifen-inducible Lgr5GFP-ERT2Cre60 (HDAC3ΔLGR5) mice. Spry2 floxed mice (MMRRC 11469) were crossed to C57BL/6J-Villin-Cre to generate Spry2ΔIEC mice as previously described.35 Sex- and age-matched littermate controls were used for all studies. Mice were housed up to 4-per cage in a ventilated cage system in a 12-h light/dark cycle, with free access to water and food. All mouse studies were conducted with approval by Animal Care and Use Committees at CCHMC. These protocols follow standards enacted by the United States Public Health Services and Department of Agriculture. All experiments followed standards set forth by Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE).

GF mono-association and murine type 2 immune models.

For tamoxifen-inducible models, mice were given daily intraperitoneal injections of 1 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma) for 5 days. Mice were provided 150 mM of sodium succinate hexahydrate (Alfa Aesar), 150 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma), or 0.5 mg/mL of vancomycin (GoldBio) dissolved in drinking water for 7-15 days. For mono-association, GF mice were pre-treated with 0.2 M sodium bicarbonate for 10 mins prior to being gavaged with 2 x 109 F. prausnitizii as previously described.22,61 Mice were colonized for 14 days prior to succinate treatment or harvest. Fecal content DNA was isolated from stool pellets and small intestinal contents using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the kit protocol. Bacterial DNA was assessed by quantitative PCR (QuantStudio3; Applied Biosystems) using bacterial-specific or 16S primer pairs (Table S1). For Nippostrongylus brasiliensis infection, mice were injected subcutaneously with 500 stage 3 larvae as previously described62,63 and monitored daily for egg counts. Mice were sacrificed at day 7 and day 10 post-infection. Serum IL-13 levels were determined via IV capture antibody cytokine assay (IVCCA) as previously described.64,65

Bacterial strains and culture.

Faecalibacterium prausnitizii was cultured in YBHI Media (Brain Heart infusion media, 0.5% yeast extract, 5 mg/L Hemin, 1 mg/mL cellulose, 1 mg/mL maltose, 0.5 mg/mL cysteine) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions as previously described.22,61

Murine and human intestinal organoid cultures.

Murine organoids were generated from crypts isolated from ileum as previously described.22,66 Briefly, the ileum was opened, cleaned, scraped to remove villi, and cut into 1-cm pieces. Tissue was incubated in chelation buffer (2 mM EDTA in PBS) for 30-min at 4°C with rotation then transferred into shaking buffer (PBS, 43.3 mM sucrose, 54.9 mM sorbitol) and shaken by hand. Crypts were plated in Matrigel (Corning) with organoid culture media (60% Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamate, 40% L-WRN conditioned media, 1x N2, 1x B27, 50-ng/mL murine EGF, and 10 μM Y-27632) overlaid. Media was changed every 2-3 days. Murine organoids were stimulated with 1 mM butyrate for 24 hrs, then stimulated with 20 ng/mL of murine IL-13 (PeproTech), 20 ng/mL of murine IL-22 (PeproTech), or 100 Units/mL of murine IFNγ (BioLegend) for 72 hrs. For HDAC3 deletion in organoids derived from HDAC3ΔIEC-IND mice, cells were treated with 1 μM of hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, Sigma) for 24 hrs prior to other treatments. For chromatin analyses, organoids were treated with butyrate for 96 hrs.

For human organoids, de-identified terminal ileal biopsies were obtained from pediatric patients undergoing endoscopic analyses. Donors were recruited prospectively as controls for participation in the IBD Biorepository protocol at CCHMC (IRB 2011-2285) and histologic analyses confirmed patients as non-IBD healthy controls. Ileal biopsies were first incubated in strip buffer (PBS, 5% FBS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT), then incubated in wash buffer (Advanced DMEM, 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamate, penicillin-streptomycin) with 2 mg/mL collagenase type I (Invitrogen) at 37°C for 5-15 mins with vigorous mixing as previously described.67 Crypts were plated in Matrigel with Human Organoid Growth Media (StemCell) supplemented with 10 μM Y-27632, and 10 μM SB 431542. Once organoids were established, they were maintained in human organoid culture media (50% Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamate, 50% L-WRN conditioned media, 1x N2, 1x B27, 50-ng/mL human EGF, 10μM Y-27632, and 10 μM SB 431542). For experiments, organoids were split and cultured in Human Organoid Differentiation Media (StemCell) supplemented with 10 μM DAPT. Organoids were stimulated with 0.5 mM butyrate for 24 hrs, then treated with 20 ng/mL of human IL-13 (PeproTech) for 72 hrs and assessed for gene expression or microscopy. For HDAC3i treatments, human organoids were stimulated with 10 μM of RGFP966 for 24 hrs before 72hrs of IL-13 treatment and assessed for gene expression or microscopy. For chromatin analyses, organoids were treated with butyrate or HDAC3i (RGFP966) for 96 hrs.

METHOD DETAILS

Cell Isolation.

The small intestine was harvested, opened, and washed in PBS. For IECs, tissue was placed in pre-warmed strip buffer (PBS, 5% FBS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) and incubated at 37°C at a 45-degree angle with shaking at 180-rpm for 15-min. After strip buffer, crypt-associated IECs were isolated by cutting intestinal tissue into 1-cm pieces, transferring tissue into ice-cold Shaking Buffer (PBS, 43.3 mM sucrose, 54.9 mM sorbitol), and shaking by hand for 5 mins. Crypts were visualized and isolated by passing through a 70μM cell strainer. For flow cytometry, crypts were dissociated into single-cell suspension by incubating in pre-warmed 5% TrypLE Express (diluted in Advanced DMEM) at 37°C at a 45-degree angle with shaking at 180-rpm for 15-25 mins. For lamina propria isolation, tissue was washed with PBS to remove EDTA and DTT then incubated in pre-warmed digestion buffer (RPMI with 1-mg/mL collagenase/dispase (Sigma)) at 37°C at a 45-degree angle with shaking at 180-rpm for 30-min. After incubation, the tissue was vortexed and passed through a 70μM cell strainer.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were stained for flow cytometry using the following antibodies diluted in FACS buffer (2% FBS, 0.01% sodium azide, PBS): BV711-anti-CD326 (EpCAM) (Clone:G8.8, BD Bioscience), BUV395-anti-CD45.2 (Clone:104, BD Bioscience), APC-eFluor-780-anti-KLRG-1 (Clone: 2F1, Invitrogen), Pe-Cy7-anti-CD127 (Clone: A7R34, Invitrogen), PE-CF594-anti-CD25 (Clone: PC61, BioLegend), PE-anti-SiglecF (Clone: E50-2440, BD Bioscience), PerCP-eFluor710-anti-CD4 (Clone: RM4-5, Invitrogen), PerCP-eFluor710-anti-CD8a (Clone: 53-6.7, Invitrogen), PerCP-eFluor710-anti-B220 (Clone: RA3-6B2, Invitrogen), PerCP-eFluor710-anti-Ly6G (Clone: 1A8-Ly6g, Invitrogen), PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-CD11b (Clone: M1/70, Invitrogen), PerCP-Cy5.5-anti-CD11c (Clone: N418, Invitrogen), Super Bright 645-anti-Sca-1 (Clone: D7, Invitrogen), FITC-anti-CD90.2 (Clone: 53-2.1, Invitrogen), APC-eFluor-780-anti-CD24 (Clone: M1/69, Invitrogen), APC-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (#31984, Invitrogen), anti-DCLK1 (ab31704, Abcam). Dead cells were excluded with the Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen). The BD Fix/Perm kit was used for intracellular staining. Samples were acquired on the BD LSRFortessa and analyzed with FlowJo Software (Treestar).

Gene expression and RNA-sequencing.

RNA from primary IECs and organoids were isolated using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using the Verso reverse transcriptase kit (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR green (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using murine and human primer sets found in Table S1. For global expression analyses, RNA was isolated from organoids and subjected to Illumina next-generation sequencing. Sequencing reads were trimmed to remove bar codes and mapped to the mouse genome (GRCm38) using Bowtie2.68 Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 within Seqmonk (V1.47.1) (p<0.05, fold change >1.5).69

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and ChIP-sequencing.

ChIP-qPCR on IECs was performed as described previously.22,24,70 Briefly, cells were fixed for 10 min in 1% formaldehyde at room temperature, followed by quenching with 125 mM glycine for 10 min. After a two-step wash with cold PBS, fixed cells were lysed, and nuclear extracts were washed in TE 0.1% SDS with protease inhibitors and sonicated using a S220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris). Prior to immunoprecipitation, sheared chromatin was precleared for 20 min at 4°C using Protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunoprecipitations were performed using fresh beads and anti-Histone H3 acetyl K9 (H3K9Ac) antibody (#06-942, Millipore) using a SX-8G IP-STAR automated system (Diagenode) with the following wash buffers: (1) RIPA 150 mM NaCl, (2) RIPA 400 mM NaCl, (3) Sarkosyl Buffer (2 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2% sarkosyl (Lauroylsarcosine sodium salt (Sigma)), and (4) TE 0.2% Triton X-100. Immunoprecipitated chromatin were treated with Proteinase K (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 42°C for 30 min, 65°C for 4 hr, and 15°C for 10 min in elution buffer (TE 250 mM NaCl 0.3% SDS). Phenol:chloroform isoamyl alcohol with Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and chloroform phase-separation were used to isolate DNA, followed by overnight ethanol precipitation for primary IECs or via QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) for organoids. ChIP DNA was treated with molecular grade RNase and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR using the custom-made primer pairs listed in Table S1. Data were analyzed as percent enrichment over input DNA.

For ChIP-seq data analysis, ChIP-seq reads were aligned to UCSC mouse genome 10 mm using STAR aligner.71 Only uniquely aligned reads were used for downstream analysis, and redundant reads were deduplicated using Picard tool (Broad Institute). Initial peak calling was performed against input control using Homer with options “-style histone-fdr 0.001”. Differential domain calling was performed on transcription start sites (TSS) of RefSeq genes. TSS-associated H3K9Ac peaks were pooled and merged from n=3 of vehicle and butyrate conditions. Read counts were measured from each replicate within the merged peaks, which were then subjected to differential analysis using EdgeR.72 Differential peaks were selected by p < 0.05 and abs(log2FC) > 0.5. Peaks were annotated and associated with a nearby gene by Homer.73 Gene ontology analysis was performed using DAVID.74 BigWig files were generated to visualize ChIP-seq data profile in read-per-million (RPM) scale using IGV.75

Tissue immunofluorescence.

Ileal biopsies were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and heated in antigen retrieval buffer (Tris-EDTA buffer with 0.05% Tween-20, pH 9.0 or sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0) for 20 minutes using a water bath at 95°C. Combined Alcian Blue-Periodic Acid Schiff (AB-PAS) staining was performed to detect goblet cells. For immunofluorescence, sections were washed in PBS and blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed three times in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. To visualize the nuclei, sections were incubated in PBS containing DAPI for 10 minutes at room temperature. Stained sections were washed three times in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 before mounting with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen). Immunofluorescence was performed using the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-E-Cadherin (Clone: 36/E-Cadherin, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-DCLK1 (ab31704, Abcam), rabbit anti-MUC2 (NBP1-31231, Novus Biologicals), rabbit anti-Lysozyme EC 3.2.1.17 (A0099, Dako), goat anti-TdTomato (AB8181, SICGEN), and AlexaFluor-594-anti-CD326 (EpCAM) (Clone: G8.8, BioLegend). The following secondary antibodies were all from Jackson ImmunoResearch unless noted: AlexaFluor-647-donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) (705-605-147), AlexaFluor-488-donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (711-545-152), and AlexaFluor-555-donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (ab150106, Abcam). For EdU pulse-chase experiments, mice were injected with 100 μg of Click-IT EdU IP and intestine harvested after 36 hrs. EdU positive cells were detected using the AlexaFluor-488-Click-iT EdU Cell Proliferation Kit for Imaging (C10337, Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s protocol. Images were acquired with a Nikon A1 inverted confocal microscope. Images were processed using Nikon NIS-elements software and Fiji: ImageJ. EdU migration was measured from the bottom of the crypt-villus axis using the line selection tools in Fiji: ImageJ. EdU+ cells were quantified per crypt-villus unit.

Organoid immunostaining.

Human and mouse organoids were plated in 8-well u-slide (ibidi) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20-min. Organoids were permeabilized for 20-min in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 followed by a 30-min incubation in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.05% Tween, 1% BSA, and 1% normal goat serum). Organoids were stained overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer containing DAPI (Sigma), AlexaFluor-647-Phalloidin (Invitrogen) and anti-DCLK1 (ab31704, Abcam) for mouse or AlexaFluor-488-anti-pEGFR (ab205827, Abcam) for human. Organoids were washed, covered with mounting media (ibidi),and imaged using a confocal microscope (Nikon).

Quantification of short-chain fatty acids.

Fecal samples were collected and flash frozen. Samples were prepared for gas-chromatology mass spectrometry as previously described.76 Briefly, fecal samples were homogenized with water at a concentration of 1 mg of sample per 10 μL of water. Samples were sonicated for 15 mins, then centrifuged at top-speed at 4°C for 15 mins. Buffer and derivatization reagents were added in supernatant following the ratio of 5:2:14 (Supernatant: Buffer: derivatization reagent, v/v/v). 100 μL of supernatant was transferred to a glass vial and 40 μL PBS (buffer) and 280 uL of pentafluorobenzyl bromide (derivatization reagent) was added. Samples were vortexed for 2 mins and incubated in a water bath at 60°C for 90 mins. 100 μL of hexane was added after the sample cooled down to extract short chain fatty acids. Samples were vortexed, centrifuged, then the top layer (hexane phase) was transferred to a gas chromatography vial for GC-MS analysis. Sample preparation and GC-MS analysis was conducted by Center for Regulatory and Environmental Analytical Metabolomics (CREAM) at University of Louisville.

HDAC activity assay.

HDAC activity was detected using a fluorometric assay (BioVision) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, IECs or organoids were lysed in RIPA buffer and 10 μg of protein was incubated with HDAC Assay buffer and HDAC substrate for 1 hr at 37°C. Lysine developer was added and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to stop the reaction. Fluorescence was measured using a fluorescent plate reader (Biotek Synergy 2) with excitation wavelength of 340 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm. Organoids were treated with 20 ng/mL of IL-13 or 1 mM of butyrate for 4 hrs prior to HDAC activity assay. F. prausnitizii was cultured in enriched BHI-Y media as previously described.22,61 After 72 hrs of growth, F. prausnitizii-conditioned culture media was sterile filtered and incubated with organoids at a concentration of 60% BHI or F .prausnitizii-conditioned media; 40% organoid culture media overnight. Organoids were also stimulated with 1 x 106 CFUs/well of F. prausnitizii overnight.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined with the Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA. Results were considered significant at *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Statistical significance was calculated using Prism version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Human and mouse tuft cell expansion is inhibited by microbiota-derived butyrate

Butyrate controls tuft cell dynamics through histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3)

HDAC3 is required for tuft cell hyperplasia and anti-helminth type 2 immunity

Stem cell-intrinsic HDAC3 instructs intestinal tuft cell differentiation

Acknowledgements.

We thank members of the Center for Inflammation and Tolerance at CCHMC for useful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank CCHMC Veterinary Services, Research Flow Cytometry Core, Confocal Imaging Core, Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility, Pathology Research Core, Gene Expression Core, University of Cincinnati Genomics Core, and University of Louisville CREAM Core for services and technical assistance. This research is supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK114123, DK116868 to T.A.; DK095004, DK119694 to M.R.F; K01DK131390 to M.A.S.; and F32AI147591, K01DK135647 to E.M.E.), and a Kenneth Rainin Foundation award to T.A. T.A. holds an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. This project is supported in part by P30 DK078392, U54 DK126108, and the Center for Stem Cell & Organoid Medicine at CCHMC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests. The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammad H, and Lambrecht BN (2015). Barrier Epithelial Cells and the Control of Type 2 Immunity. Immunity 43, 29–40. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali A, Tan HY, and Kaiko GE (2020). Role of the Intestinal Epithelium and Its Interaction With the Microbiota in Food Allergy. Front. Immunol 11, 1–12. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerbe F, Sidot E, Smyth DJ, Ohmoto M, Matsumoto I, Dardalhon V, Cesses P, Garnier L, Pouzolles M, Brulin B, et al. (2016). Intestinal epithelial tuft cells initiate type 2 mucosal immunity to helminth parasites. Nature 529, 226–230. 10.1038/nature16527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Moltke J, Ji M, Liang H, and Locksley RM (2016). Tuft cell derived IL-25 regulates an intestinal ILC2-epithelial response circuit. Nature 529, 221–225. 10.1038/nature16161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howitt MR, Lavoie S, Michaud M, Blum AM, Tran SV, Weinstock JV, Gallini CA, Redding K, Margolskee RF, Osborne LC, et al. (2016). Tuft cells, taste-chemosensory cells, orchestrate parasite type 2 immunity in the gut. Science (80-, ). 351, 1329–1333. 10.1126/science.aaf1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yi J, Bergstrom K, Fu J, Shan X, McDaniel JM, McGee S, Qu D, Houchen CW, Liu X, and Xia L (2019). Dclk1 in tuft cells promotes inflammation-driven epithelial restitution and mitigates chronic colitis. Cell Death Differ. 26, 1656–1669. 10.1038/s41418-018-0237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May R, Qu D, Waygant N, Chandrakesan P, Ali N, Lightfoot S, Li L, Sureban S, and Houchen CW (2014). Dclk1 Deletion in Tuft Cells Results in Impaired Epithelial Repair After Radiation Injury. Stem Cells 32, 822–827. 10.1002/stem.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu D, Weygant N, May R, Chandrakesan P, Madhoun M, Ali N, Sureban SM, An G, Schlosser MJ, and Houchen CW (2015). Ablation of Doublecortin-Like Kinase 1 in the Colonic Epithelium Exacerbates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis. PLoS One 10, 1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fallon PG, Ballantyne SJ, Mangan NE, Barlow JL, Dasvarma A, Hewett DR, McIlgorm A, Jolin HE, and McKenzie ANJ (2006). Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. J. Exp. Med 203, 1105–1116. 10.1084/jem.20051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa JI, Ohtani M, Fujii H, and Koyasu S (2010). Innate production of TH 2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit+ Sca-1+ lymphoid cells. Nature 463, 540–544. 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TKA, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, et al. (2010). Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature 464, 1367–1370. 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda K, Muto T, Kawagoe T, Matsumoto M, Sasaki Y, Matsushita K, Taki Y, Futatsugi-Yumikura S, Tsutsui H, Ishii KJ, et al. (2012). Contribution of IL-33-activated type II innate lymphoid cells to pulmonary eosinophilia in intestinal nematode-infected mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 3451–3456. 10.1073/pnas.1201042109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T, Morris SC, Gildea L, Strait R, Madden KB, Schopf L, and Urban JF (2004). Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated host protection against intestinal nematode parasites. Immunol. Rev 201, 139–155. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCoy KD, Ignacio A, and Geuking MB (2018). Microbiota and Type 2 immune responses. Curr. Opin. Immunol 54, 20–27. 10.1016/j.coi.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iweala OI, and Nagler CR (2019). The Microbiome and Food Allergy. Annu. Rev. Immunol 37, 377–403. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feehley T, Plunkett CH, Bao R, Choi Hong SM, Culleen E, Belda-Ferre P, Campbell E, Aitoro R, Nocerino R, Paparo L, et al. (2019). Healthy infants harbor intestinal bacteria that protect against food allergy. Nat. Med 25, 448–453. 10.1038/s41591-018-0324-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo V, and Alenghat T (2022). Epigenetic regulation by gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 14. 10.1080/19490976.2021.2022407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amatullah H, and Jeffrey KL (2020). Epigenome-metabolome-microbiome axis in health and IBD. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 56, 97–108. 10.1016/j.mib.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alenghat T, Osborne LC, Saenz SA, Kobuley D, Ziegler CG, Mullican SE, Choi I, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Wynosky-Dolfi M, et al. (2013). Histone deacetylase 3 coordinates commensal-bacteria-dependent intestinal homeostasis. Nature 504, 153–157. 10.1038/nature12687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eshleman EM, Shao TY, Woo V, Rice T, Engleman L, Didriksen BJ, Whitt J, Haslam DB, Way SS, and Alenghat T (2023). Intestinal epithelial HDAC3 and MHC class II coordinate microbiota-specific immunity. J. Clin. Invest 133. 10.1172/JC1162190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navabi N, Whitt J, Wu S. en, Woo V, Moncivaiz J, Jordan MB, Vallance BA, Way SS, and Alenghat T (2017). Epithelial Histone Deacetylase 3 Instructs Intestinal Immunity by Coordinating Local Lymphocyte Activation. Cell Rep. 19, 1165–1175. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S. en, Hashimoto-Hill S, Woo V, Eshleman EM, Whitt J, Engleman L, Karns R, Denson LA, Haslam DB, and Alenghat T (2020). Microbiota-derived metabolite promotes HDAC3 activity in the gut. Nature 586, 108–112. 10.1038/S41586-020-2604-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woo V, Eshleman EM, Rice T, Whitt J, Vallance BA, and Alenghat T (2019). Microbiota inhibit epithelial pathogen adherence by epigenetically regulating C-type lectin expression. Front. Immunol 10, 1–10. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitt J, Woo V, Lee P, Moncivaiz J, Haberman Y, Denson L, Tso P, and Alenghat T (2018). Disruption of Epithelial HDAC3 in Intestine Prevents Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Gastroenterology 155, 501–513. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuang Z, Wang Y, Li Y, Ye C, Ruhn KA, Behrendt CL, Olson EN, and Hooper LV (2019). The intestinal microbiota programs diurnal rhythms in host metabolism through histone deacetylase 3. Science (80-. ). 365, 1428–1434. 10.1126/science.aaw3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dávalos-Salas M, Montgomery MK, Reehorst CM, Nightingale R, Ng I, Anderton H, Al-Obaidi S, Lesmana A, Scott CM, Ioannidis P, et al. (2019). Deletion of intestinal Hdac3 remodels the lipidome of enterocytes and protects mice from diet-induced obesity. Nat. Commun 10, 1–14. 10.1038/s41467-019-13180-8.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider C, O’Leary CE, von Moltke J, Liang HE, Ang QY, Turnbaugh PJ, Radhakrishnan S, Pellizzon M, Ma A, Locksley RM, et al. (2018). A Metabolite-Triggered Tuft Cell-ILC2 Circuit Drives Small Intestinal Remodeling. Cell 174, 271–284.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei W, Ren W, Ohmoto M, Urban JF, Matsumoto I, Margolskee RF, and Jiang P (2018). Activation of intestinal tuft cell-expressed Sucnr1 triggers type 2 immunity in the mouse small intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 115, 201720758. 10.1073/pnas.1720758115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadjsombati MS, McGinty JW, Lyons-Cohen MR, Jaffe JB, DiPeso L, Schneider C, Miller CN, Pollack JL, Nagana Gowda GA, Fontana MF, et al. (2018). Detection of Succinate by Intestinal Tuft Cells Triggers a Type 2 Innate Immune Circuit. Immunity 49, 33–41.e7. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider C, Leary CEO, and Locksley RM (2019). Regulation of immune responses by tuft cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol 19. 10.1038/s41577-019-0176-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cait A, Hughes MR, Antignano F, Cait J, Dimitriu PA, Maas KR, Reynolds LA, Hacker L, Mohr J, Finlay BB, et al. (2018). Microbiome-driven allergic lung inflammation is ameliorated by short-chain fatty acids. Mucosal Immunol. 11, 785–795. 10.1038/mi.2017.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed S, Macfarlane GT, Fite A, McBain AJ, Gilbert P, and Macfarlane S (2007). Mucosa-associated bacterial diversity in relation to human terminal ileum and colonic biopsy samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73, 7435–7442. 10.1128/AEM.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishizuka T, and Lazar MA (2003). The N-CoR/Histone Deacetylase 3 Complex Is Required for Repression by Thyroid Hormone Receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol 23, 5122–5131. 10.1128/mcb.23.15.5122-5131.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaiko GE, Ryu SH, Koues OI, Pearce EL, Oltz EM, and Stappenbeck TS (2016). The Colonic Crypt Protects Stem Cells from Microbiota-Derived Metabolites. Cell 165, 1708–1720. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumacher MA, Hsieh JJ, Liu CY, Appel KL, Waddell A, Almohazey D, Katada K, Bernard JK, Bucar EB, Gadeock S, et al. (2021). Sprouty2 limits intestinal tuft and goblet cell numbers through GSK3β-mediated restriction of epithelial IL-33. Nat. Commun 12. 10.1038/s41467-021-21113-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamashita J, Ohmoto M, Yamaguchi T, Matsumoto I, and Hirota J (2017). Skn-1a/Pou2f3 functions as a master regulator to generate Trpm5-expressing chemosensory cells in mice. PLoS One 12, 1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsumoto I, Ohmoto M, Narukawa M, Yoshihara Y, and Abe K (2011). Skn-1a (Pou2f3) specifies taste receptor cell lineage. Nat. Neurosci 14, 685–687. 10.1038/nn.2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjerknes M, Khandanpour C, Möröy T, Fujiyama T, Hoshino M, Klisch TJ, Ding Q, Gan L, Wang J, Martín MG, et al. (2012). Origin of the brush cell lineage in the mouse intestinal epithelium. Dev. Biol 362, 194–218. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu XS, He XY, Ipsaro JJ, Huang YH, Preall JB, Ng D, Shue YT, Sage J, Egeblad M, Joshua-Tor L, et al. (2022). OCA-T1 and OCA-T2 are coactivators of POU2F3 in the tuft cell lineage. Nature 607, 169–175. 10.1038/S41586-022-04842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadjsombati MS, Niepoth N, Webeck LM, Kennedy EA, Jones DL,Billipp TE, Baldridge MT, Bendesky A, and von Moltke J (2023). Genetic mapping reveals Pou2af2/OCA-T1-dependent tuning of tuft cell differentiation and intestinal type 2 immunity. Sci. Immunol 8, eade5019. 10.1126/sciimmunol.ade5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szczepanski AP, Tsuboyama N, Watanabe J, Hashizume R, Zhao Z, and Wang L (2022). POU2AF2/C11orf53 functions as a coactivator of POU2F3 by maintaining chromatin accessibility and enhancer activity. Sci. Adv 8. 10.1126/sciadv.abq2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerbe F, Van Es JH, Makrini L, Brulin B, Mellitzer G, Robine S, Romagnolo B, Shroyer NF, Bourgaux JF, Pignodel C, et al. (2011). Distinct ATOH1 and Neurog3 requirements define tuft cells as a new secretory cell type in the intestinal epithelium. J. Cell Biol 192, 767–780. 10.1083/jcb.201010127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herring CA, Banerjee A, McKinley ET, Simmons AJ, Ping J, Roland JT, Franklin JL, Liu Q, Gerdes MJ, Coffey RJ, et al. (2018). Unsupervised Trajectory Analysis of Single-Cell RNA-Seq and Imaging Data Reveals Alternative Tuft Cell Origins in the Gut. Cell Syst. 6, 37–51.e9. 10.1016/j.cels.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee A, Herring CA, Chen B, Kim H, Simmons AJ, Southard-Smith AN, Allaman MM, White JR, Macedonia MC, Mckinley ET, et al. (2020). Succinate Produced by Intestinal Microbes Promotes Specification of Tuft Cells to Suppress Ileal Inflammation. Gastroenterology 159, 2101–2115.e5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gracz AD, Samsa LA, Fordham MJ, Trotier DC, Zwarycz B, Lo YH, Bao K, Starmer J, Raab JR, Shroyer NF, et al. (2018). Sox4 Promotes Atoh1-Independent Intestinal Secretory Differentiation Toward Tuft and Enteroendocrine Fates. Gastroenterology 155, 1508–1523.e10. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]