Abstract

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains the main cause of death worldwide, and thus its prevention, early diagnosis and treatment is of paramount importance. Dyslipidemia represents a major ASCVD risk factor that should be adequately managed at different clinical settings. 2023 guidelines of the Hellenic Atherosclerosis Society focus on the assessment of ASCVD risk, laboratory evaluation of dyslipidemias, new and emerging lipid-lowering drugs, as well as diagnosis and treatment of lipid disorders in women, the elderly and in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, acute coronary syndromes, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Statin intolerance is also discussed.

Keywords: Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Statins, Ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitor, Bempedoic acid, Familial hypercholesterolemia, Type 2 diabetes, Heart failure

List of abbreviations

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- ANGPTL3

angiopoietin-like protein 3

- Apo

apolipoprotein

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- BMI

body mass index

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CK

creatine kinase

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- FCHL

familial combined hyperlipidemia

- FCS

familial chylomicronemia syndrome

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- FH

familial hypercholesterolemia

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HF

heart failure

- HeFH

heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HoFH

homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- LAL

lysosomal acid lipase

- LAL-D

lysosomal acid lipase deficiency

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDLR

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- Lp(a)

lipoprotein(a)

- MCS

multifactorial chylomicronemia syndrome

- MEDPED

make early diagnosis to prevent early deaths

- MTP

microsomal transfer protein

- MASLD

metabolic associated steatotic liver disease

- MASH

metabolic associated steatohepatitis

- NOD

new onset diabetes

- PCSK9

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- PPAR-α

peroxisome proliferator activated receptor a

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SAMS

statin-associated muscle symptoms

- SCORE

systematic Coronary Risk Estimation

- sdLDL

small dense low-density lipoprotein

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SLE

systematic lupus erythematosus

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- ULN

upper limit of normal

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

1. Introduction

Greece has a population of approximately 10 million citizens. Greece is considered an intermediate country in terms of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk [1]. More than 50% of adults in Greece have some type of dyslipidemia (mainly TC ≥ 200 mg/dL) and 27% of cardiovascular deaths are attributed to dyslipidemia [2,3]. This Executive Summary of the Hellenic Atherosclerosis Society Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dyslipidemias – 2023 aims to help physicians to better identify and manage dyslipidemia to halt the increasing incidence of ASCVD in Greece.

These guidelines follow the grading system for the “Classes of recommendations” of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemias [4]. The strength of the recommendation was based on comprehensive review and critical evaluation of the published evidence for detection and management of dyslipidemia by experts in the field. Consensus was required for all recommendations. The literature review was based on keyword search and scrutinizing of published studies and guidelines.

Colleagues that need help on assessing and treating difficult cases of dyslipidemia can get help by the local EAS Lipid Clinic Network (https://eas-society.org/collaborations-outreach/lipid-clinic-network/lipid-clinics-network-contacts/).

Total Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk.

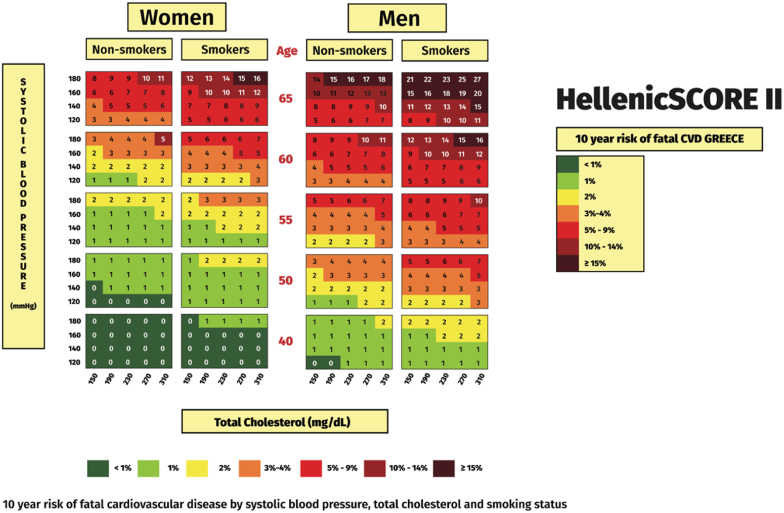

Τhe assessment of total ASCVD risk is strongly recommended [4] The use of the HellenicSCORE II, an updated ASCVD risk model based on newly derived risk factors data from the Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS) [5] is recommended for the Greek population (Table 1a and Fig. 1). HellenicSCORE II can now be calculated online at https://www.hellenicheartscore.gr/. Of note, the HellenicSCORE II (Fig. 1) does not apply for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) who are at least high-risk, irrespective of the Score. Similarly, the HellenicSCORE II is not applicable in patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and established ASCVD (see below Table 4b).

Table 1a.

Recommendations for the evaluation of total atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

| Recommendations | Class |

|---|---|

| Τhe assessment of total ASCVD risk is recommended | I |

| The use of the HellenicSCORE II is recommended for the Greek population | I |

Fig. 1.

HellenicSCORE II – 10-year risk of fatal ASCVD in Greece. (Reproduced with permission from Panagiotakos et al. [5]). ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Table 4b.

ASCVD risk groups.

| ASCVD Risk group | Patient characteristics |

|---|---|

| I. Very high ASCVD risk | 1. Established CHD 2. Ischemic stroke/TIA 3. Peripheral arterial disease 4. Atherosclerotic arterial stenosis >50% 5. Abdominal aortic aneurysm 6. Familial hypercholesterolemia with ≥1 major risk factor 7. Diabetes type 2 with target organ damage or ≥3 major risk factors (age, smoking, atherogenic dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity) or diabetes type 1 > 20 years duration 8. Chronic kidney disease stage 4 (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) 9. HellenicSCORE II ≥ 10% |

| II. High ASCVD risk group | 1. HellenicSCORE II 5–10% 2. At least one severe risk factor (stage 3 hypertension, extreme smoking, LDL-C>190 mg/dL) 3. Familial hypercholesterolemia without any major risk factor 4. Diabetes >10 years duration with 1–2 major risk factors (age, smoking, atherogenic dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity) 5. Chronic kidney disease stage 3 (eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2) 6. Autoimmune diseases/HIV infection |

| III. Moderate ASCVD risk group | 1. HellenicSCORE II 1–5% 2. Diabetes <10 years duration in persons <45 years (type 2) or <35 years (type 1) without any major risk factors |

| IV. Low ASCVD risk group | HellenicSCORE II <1% |

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CHD: coronary heart disease; TIA: transient ischemic attack; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

A limitation of HellenicSCORE II scoring system is that it considers only 5 ASCVD-related parameters. Thus, the following parameters that may increase ASCVD risk [4,6] should be taken into account for the estimation of total ASCVD risk and be used as risk modifiers:

-

•

Social deprivation

-

•

Obesity, especially central obesity

-

•

Physical inactivity

-

•

Family history of premature ASCVD (men <55 years; women <60 years)

-

•

Major psychiatric disorders

-

•

Atrial fibrillation

-

•

Left ventricular hypertrophy

-

•

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome

-

•

Μetabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [7].

-

•

History of premature menopause (before age 40 y) and history of pregnancy-associated conditions that increase later ASCVD risk, such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes

-

•

High-risk race/ethnicities (e.g., South Asian ancestry)

-

•

Exposure to high air pollution

-

•Lipid-related markers

-

•Persistently elevated, primary hypertriglyceridemia (≥150 mg/dL)

-

•Non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) >190 mg/dL

-

•Elevated lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] ≥50 mg/dL or ≥125 nmol/L

-

•Elevated apolipoprotein (apo) B ≥ 130 mg/dL

-

•

To convert total cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C from mg/dL to mmol/L, divide by 38.67. To convert triglycerides from mg/dL to mmol/L, divide by 88.57.

-

•Other biomarkers/imaging:

-

•Elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (≥2.0 mg/L)

-

•Ankle-brachial index (ABI) < 0.9

-

•Arterial (carotid and/or femoral) plaque burden on ultrasonography

-

•Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score

-

•

1.1. Laboratory evaluation of dyslipidemias

The recommendations on the laboratory evaluation of dyslipidemias are presented in Table Table 1b.

Table 1b.

Recommendations for the laboratory evaluation of dyslipidemias.

| HDL-C is recommended to further refine risk estimation | |

|---|---|

| Before lipid-lowering therapy initiation, lipid levels (TC, LDL-C, HDL-C and TG) are recommended to be measured at least twice, with an interval of 1–12 weeks, except when immediate drug treatment is required, such as in ACS and very high-risk patients | I |

| LDL-C is recommended as the primary lipid target for screening, diagnosis, and management of dyslipidemias | I |

| HDL-C is not recommended as a treatment target | III |

| Non-HDL-C estimation is recommended for risk assessment and as a secondary target, especially in subjects with high TG levels, diabetes, obesity, or very low LDL-C levels | I |

| ApoB can be used as a secondary target for screening, diagnosis, and treatment of dyslipidemias | IIb |

| Lipid monitoring is performed at 8 ± 4 weeks following initiation of therapy. Once a patient has achieved the target lipid level, lipid monitoring should be performed annually | I |

| Alanine aminotranferase (ALT) measurement is recommended before starting statin treatment, 8–12 weeks after statin initiation or dose change, as well as in cases with clinical indication of liver disease. If ALT is ≥ 3xULN on two consecutive occasions, statin therapy should be stopped or the dose be reduced, and ALT should be rechecked within 4–6 weeks | IIa |

| Creatine kinase (CK) measurement is recommended before starting statin treatment as well as in cases with clinical indication of statin-associated muscle symptoms. Routine monitoring of CK during statin treatment is not recommended | I |

| In patients at high-risk of developing diabetes (i.e., elderly, obese, with metabolic syndrome, or other signs of insulin resistance) and on high-dose statin therapy, HbA1c and fasting glucose should be assessed annually during lipid-lowering therapy | IIa |

TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; apo: apolipoprotein; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; ULN: upper limit of normal.

1.2. Lifestyle recommendations for the reduction of ASCVD risk

The adoption of healthy lifestyle patterns remains the cornerstone for the prevention and treatment of ASCVD in both primary and secondary prevention settings [8,9].

The lifestyle recommendations for the reduction of ASCVD risk are presented in Table 1c.

Table 1c.

Lifestyle recommendations for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

| A weight loss of >5% is a prerequisite for meaningful beneficial effects on lipid levels | I |

| Pharmacological treatment for obesity, or metabolic surgery may be considered for obese or overweight individuals with weight-related comorbidities always in conjunction with lifestyle interventions | IIb |

| Dietary fat is recommended to be consumed mainly via vegetable oils, fish, and nuts. A total fat intake higher than 35% of total energy intake should be avoided, especially for people with mild to moderate hypercholesterolemia | I |

| Most carbohydrates are recommended to derive from unprocessed, non-refined food sources providing high amounts of dietary fibers | I |

| Patients with dyslipidemia must be encouraged to achieve at least 30 min/day of physical activity | I |

1.3. New and emerging lipid-lowering drugs

Statins are the cornerstone of hypolipidemic treatment [4]. Ezetimibe is an established treatment for patients who do not achieve LDL-C targets or have statin intolerance [4].

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors increase the recycling of LDL receptors (LDLRs) to the cell membrane of the hepatocyte by reducing their degradation. Currently, there are two human monoclonal antibodies in clinical use, alirocumab and evolocumab, targeting the PCSK9 protein. The FOURIER trial showed that inhibition of PCSK9 by evolocumab resulted in a significant 15% reduction of the primary end-point compared with placebo [10]. Similarly, in the ODYSSEY Outcomes trial alirocumab reduced the composite primary end-point compared by 15% compared with placebo [11]. In addition, inclisiran, a long-acting small interfering RNA (siRNA) PCSK9 inhibitor [12], has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for adults with HeFH or ASCVD who require additional LDL-C decrease [13,14]. Inclisiran acts specifically in the liver by inhibiting the hepatic synthesis of PCSK9 [15]. Inclisiran produces durable and robust decreases of PCSK9 and LDL-C when administered subcutaneously at a dose of 300 mg once every 6 months, after the initial and 3-month doses [16]. The ongoing phase III trials ORION-4 and VICTORION-2P (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03705234 and NCT05030428) will evaluate the effect of inclisiran on major adverse CVD events in patients with ASCVD.

Bempedoic acid is an oral LDL-C-lowering drug which reduces cholesterol biosynthesis by inhibiting the activity of ATP citrate lyase, an enzyme located upstream 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase, leading to upregulation of LDL-R, and thus reduction of LDL-C levels in the circulation [17]. Bempedoic acid is administered at a dose of 180 mg daily as a prodrug and is converted to active drug exclusively in the liver (but not muscles), thus minimizing the risk of muscle-related side-effects [17]. The CLEAR Outcomes trial randomized 13,970 intolerant to statins patients to bempedoic acid or placebo (median follow-up 40.6 months) [18]. The mean LDL-C level was reduced by 21.1% by bempedoic acid. A significant reduction in the primary endpoint was observed with bempedoic acid compared with placebo (hazard ratio 0.87; 95% CI 0.79–0.96, p = 0.004) [18]. Reported adverse effects of bempedoic acid include hyperuricemia, gout and tendon Achille rupture [19].

Pemafibrate is a novel, selective, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor a (PPAR-α) agonist [20]. The PROMINENT study in type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia (i.e., TGs≥200 mg/dL and HDL-C ≤40 mg/dL) was stopped early as the results of a planned interim analysis showed that pemafibrate did not significantly reduce the incidence of ASCVD events compared with placebo [21].

Omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are administered in the form of either TG, carboxyl esters or ethyl esters. In 2019 the EMA confirmed that omega-3 fatty acids containing a combination of EPA and DHA ethyl esters at a daily dose of 1 g are not effective in preventing recurrence of coronary heart disease (CHD) events in patients who had previously suffered a myocardial infarction [22]. Therefore, these agents are being used for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia at 2–4 g/day dose. The STRENGTH trial, which evaluated the effects of 4 g/day omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) or a matching corn oil comparator in 13,078 hypertriglyceridemic patients was terminated early due to interim analysis showing a low probability for ASCVD benefit [23]. The REDUCE-IT trial showed that daily administration of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (2 g twice a day) in hypertriglyceridemic patients with established ASCVD or T2D plus ≥1 additional ASCVD risk significantly reduced (by 25%) the incidence of MACE compared with placebo after a median follow-up of 4.9 years [24]. The EMA has approved the use of EPA as an adjunctive therapy to reduce the risk of ASCVD events among statin-treated patients with hypertriglyceridemia (defined as TGs ≥150 mg/dL) who have either established ASCVD or T2D plus ≥1 additional CV risk factors [25,26].

1.4. Lp(a) and ASCVD risk

Lp(a) consists of a LDL particle to which a plasminogen-like glycoprotein, apo(a), is linked by a single disulfide bond [27]. Plasma Lp(a) levels are primarily genetically determined. It is preferable to measure Lp(a) molar concentration (in nmol/L) [28].

Data from epidemiological databases, mendelian randomization studies and genome-wide association studies support the role of Lp(a) as a causal risk factor for ASCVD [[29], [30], [31], [32]].

Importantly, according to the recent EAS consensus on Lp(a), there is a linear relationship between Lp(a) levels and the risk of ASCVD [29].

Lp(a) levels should be measured at least once in each person's lifetime and should be considered for the reclassification of patient ASCVD risk (Table 1d).

Table 1d.

Recommendations for Lp(a) assessment and use.

| Lp(a) levels are recommended to be measured at least once in each person's lifetime | I |

| Lp(a) assessment should be considered for the reclassification of patients having a borderline estimated 10-year ASCVD risk | IIa |

To date, there are no drugs available to drastically reduce plasma Lp(a) levels [29]. Apheresis induces an acute reduction of Lp(a) levels by >60% in parallel with LDL-C decrease [33].

A large reduction in Lp(a) levels by approximately 90% has been achieved with the use of the specific ASO, pelacarsen, targeting apo(a) [34]. The pivotal phase 3 outcomes study of pelacarsen, Lp(a)HORIZON, is expected to establish whether lowering Lp(a) will result into an ASCVD risk reduction [35]. Olpasiran is a N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated siRNA that inhibits LPA mRNA translation in hepatocytes, leading to the reduction of Lp(a) levels by up to 90% at doses of 9 mg or higher [36,37]. Olpasiran effects on ASCVD events are examined in the phase III OCEAN trial (NCT 05581303).

1.5. Dyslipidemia in acute coronary syndromes (ACS)

In ACS patients, administration of high-intensity statins protects against death and major ASCVD events [38,39]. We strongly suggest an immediate and large reduction in LDL-C levels by ≥ 50% from baseline values with a LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL (1.4 mmol/L) [4,40] (Table 1e).

Table 1e.

Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

| LDL-C is recommended to be measured within 48 h after an ACS | I |

| A high-dose statin therapy is recommended to be initiated or continued as early as possible in all ACS patients (without any contraindication or definite history of intolerance), irrespective of baseline LDL-C levels | I |

| Lipid levels should be rechecked 4–6 weeks after the ACS | IIa |

| In a statin-naïve patient with LDL-C ≥110 mg/dL, high-intensity statin plus ezetimibe should be administered | IIa |

| In statin-treated patients, statin therapy must be immediately uptitrated to atorvastatin 40–80 mg or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg at hospital admission. LDL-C must then be measured within 48 h and if ≥ 70 mg/dL, ezetimibe should be administered during hospitalization |

I IIa |

| If the LDL-C target is not achieved after 4–6 weeks with the maximally tolerated statin dose, adding ezetimibe is recommended | I |

| If the LDL-C target is not achieved after 4–6 weeks with the maximally tolerated statin dose plus ezetimibe, adding a PCSK9 inhibitor is recommended | I |

| In patients presenting with ACS whose LDL-C levels are off target despite receiving a maximally tolerated dose of statin and ezetimibe, the addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor should be considered early after the event (even during hospitalization for the ACS) | IIa |

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

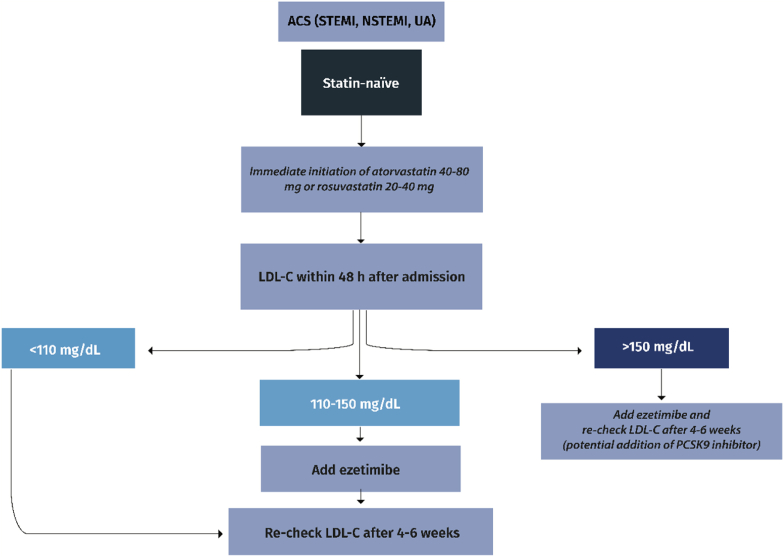

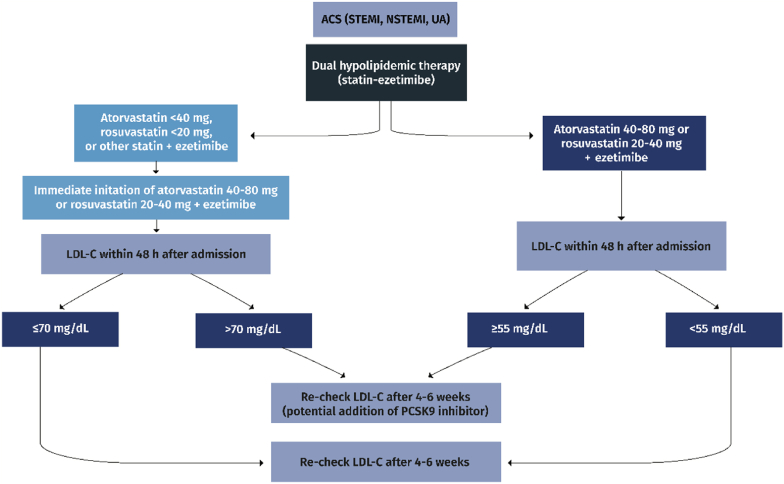

According to the 2023 HAS guidelines (Table 1g):

-

I.In statin-naïve ACS patients (Fig. 2a):

-

➢atorvastatin 40–80 mg or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg must be immediately initiated at hospital admission (Class I)

-

➢LDL-C must be measured within 48 h and if ≥ 110 mg/dL, ezetimibe should also be administered during hospitalization (Class IIa)

-

➢

-

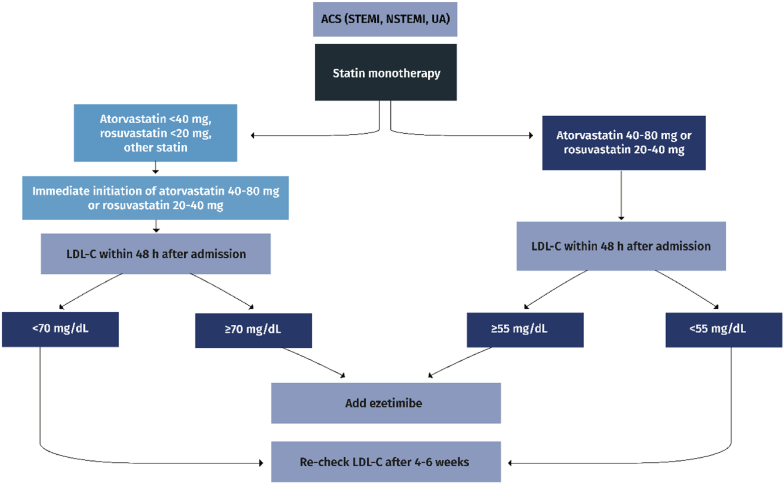

II.In statin-treated ACS patients (Fig. 2b):

-

➢statin therapy must be uptitrated to atorvastatin 40–80 mg or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg at hospital admission (Class I)

-

➢LDL-C must then be measured within 48 h and if ≥ 70 mg/dL, ezetimibe should also be administered during hospitalization (Class IIa)

-

➢

-

III.In ACS patients on statin plus ezetimibe (Fig. 2c)

-

➢LDL-C must be measured within 48 h and if ≥ 55 mg/dL, ezetimibe should also be administered during hospitalization (Class IIa)

-

➢LDL-C must be re-checked at 4–6 weeks after hospital discharge and if still off-target, a PCSK9 inhibitor is recommended (Class I)

-

➢

Table 1g.

Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

| Stage 3 CKD patients (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) are considered at high risk. LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and LDL-C goal <70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) are recommended | I |

| Stage 4–5 CKD patients (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) are at very high risk; LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and LDL-C goal <55 mg/dL (1.4 mmol/L) are recommended | I |

| The use of statins or statin/ezetimibe combination is indicated in non-dialysis dependent CKD patients | I |

| In patients already on statins, ezetimibe or a statin/ezetimibe combination at the time of dialysis initiation, lipid-lowering therapy should be continued | IIa |

| In patients with CKD without ASCVD who require dialysis, statin treatment should not be initiated | III |

| In adult kidney transplant recipients, statin treatment should be considered | II |

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Fig. 2a.

Management of dyslipidemia in statin-naïve patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS). STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UA: unstable angina; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Fig. 2b.

Management of dyslipidemia in statin-treated patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS). STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UA: unstable angina; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Fig. 2c.

Management of dyslipidemia in statin-plus-ezetimibe-treated patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UA: unstable angina; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

1.5.1. Statin use in heart failure

Statins might be beneficial in reducing ASCVD risk in patients with less advanced heart failure (HF), whereas in severe HF, it could be too late for any potential benefits from statin therapy due to progressive loss of pump function [41].

-

•

LDL-C lowering with statins reduces the incidence of HF in patients with stable CHD or ACS without previous HF [4].

-

•

In advanced stages of HF with severe cachexia, statin continuation may be reconsidered in the scope of personalized approach or palliative care.

-

•

Statin initiation is not generally recommended (Class III), except for patients already receiving a statin for CHD [42].

-

•

There are no randomized controlled trials that evaluated the use of ezetimibe in HF patients.

-

•

There is one ongoing trial with evolocumab in HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients [EVOlocumab in Stable Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction of Ischemic Etiology: EVO-HF Pilot (EVO-HF)] [43].

1.5.2. Prevention of stroke

Risk reduction for a first ischemic stroke per 39 mg/dL LDL-C decrease is about 21%, and it is similar in men and women [44,45]. Following a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), patients are at a very high risk of major ASCVD events, including recurrent stroke [46]. Secondary prevention statin therapy significantly lowers the risk of recurrent stroke (by 12% per 39 mg/dL reduction in LDL-C), MI and vascular death [4,47,48].

-

•

Concerns for an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke with statin treatment and achievement of very low LDL-C levels, whether on a statin alone or on combination of a statin with ezetimibe or/and a PCSK9 inhibitor, do not appear to be justified [49,50].

Routine use of statins in the (hyper-)acute phase of stroke (first 2 days to one week) is not supported by solid evidence from randomized controlled trials [51,52]. However, based on observational data, in-hospital statin use may be related to better functional outcomes and lower mortality, whereas statin withdrawal can lead to poor functional outcomes [53] (Table 1f).

Table 1f.

Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia for primary and secondary prevention of stroke.

| Lipid-lowering treatment with statins in combination with lifestyle changes is recommended for primary prevention of ischemic stroke in patients who have high or very-high ASCVD risk | I |

|---|---|

| Prophylactic intensive statin-based lipid-lowering therapy is recommended in patients with a history of non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA for the secondary prevention of stroke | I |

| In patients with a history of ischemic stroke or TIA a treatment goal of LDL-C <55 mg/dL and a ≥50% reduction from baseline LDL-C levels is recommended | I |

| If LDL-C target is not achieved with the maximally tolerated dose of statin, ezetimibe must be added | I |

| If LDL-C target is not achieved with the maximally tolerated dose of statin + ezetimibe, a PCSK9 inhibitor must be added | I |

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Sub-analyses of the IMPROVE-IT, FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trials showed that in patients with a history of stroke, the addition of ezetimibe, evolocumab or alirocumab significantly reduced the risk of all strokes and ischemic strokes, respectively [[54], [55], [56]].

1.5.3. Management of dyslipidemia in patients with CKD

-

•

In all CKD patients, a fasting lipid profile should be assessed to determine the need for initiation of lipid-lowering treatment, diagnose secondary causes of dyslipidemia (e.g., nephrotic syndrome) and identify hypertriglyceridemia, a frequent lipid abnormality in CKD patients [57].

-

•

Stage 3 CKD patients [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2] are considered at high risk (Table 1g) in whom an LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL-C goal <70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) are recommended [4,58] (Class I)

-

•

Stage 4–5 CKD patients (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 not on dialysis) are at very high risk; LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL-C goal <55 mg/dL (1.4 mmol/L) are recommended [4] (Class I)

-

•

Statin ± ezetimibe therapy was reported to significantly reduce major CV events in both primary and secondary settings in CKD patients (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) [59,60].

-

•

Several meta-analyses reported that the relative reduction in major CV events with statin therapy becomes smaller with eGFR decline, with little or no evidence of benefit in patients on dialysis [61]. Of note, only a few patients on dialysis or with renal transplants have been included in lipid-lowering trials [[62], [63], [64]] [[62], [63], [64]] [[62], [63], [64]];

-

•

Statins were shown to decrease microalbuminuria and proteinuria in a previous meta-analysis [65]. Another statin-related renal benefit refers to the prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) [[66], [67], [68], [69]] [[66], [67], [68], [69]] [[66], [67], [68], [69]].

-

•

Dose adjustments may be needed in CKD patients depending on statin used, concomitant drugs (e.g., cyclosporin) and eGFR [70]. Atorvastatin therapy does not require dose changes in such patients, since this drug is cleared exclusively by the liver in contrast to rosuvastatin which has both liver and kidney clearance and thus needs dose adjustments according to eGFR. Furthermore, fenofibrate should be used with caution in CKD patients, since this drug is associated with transient serum creatinine level increase [71]. Of note, the National Kidney Foundation recommends fenofibrate dosing to be decreased by 50% when eGFR is 60–90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and by 75% when eGFR is 15–59 mL/min/1.73 m2, and fenofibrate should be avoided in patients on hemodialysis or with eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 [72].

1.5.4. Management of dyslipidemia in women

-

•

Statin therapy is recommended for primary ASCVD prevention in women at high ASCVD risk. Pregnancy-associated adverse health conditions (such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, gestational diabetes) and menopause (especially early or premature) should be considered as risk-enhancing factors (Class I)

•Statins are recommended for secondary prevention in women with the same recommendations and therapeutic goals as in men (Class I)

•Lipid-lowering therapy should not be administered 1–2 months before pregnancy is attempted, during pregnancy and during the breastfeeding period (Class III). It should be noted that in 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requested removal of the “Pregnancy Category X” label for statins based on emerging data of healthy pregnancy in individuals taking statins [73].

•The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requested the removal of the contraindication against statin use in all pregnant patients, because the benefits of statins may include prevention of serious or potentially fatal events in a small group of very high-risk pregnant patients, especially in patients with HoFH and those who have previously had a heart attack or stroke [74]. Importantly, patients with high ASCVD risk who require statins during pregnancy should not breastfeed after giving birth and should use alternatives such as infant formula [74].

1.5.5. Management of dyslipidemia in the elderly

Risk of adverse effects of lipid-lowering agents due to the presence of comorbidities (particularly impaired renal function) and polypharmacy should be taken into consideration in the elderly patients. Therefore, statins with minimal risks for interactions with other treatments (e.g., rosuvastatin) and minimal renal clearance (e.g., atorvastatin and pitavastatin) should be preferred in the elderly. In such cases, statin therapy should be started at a low dose and then titrated upwards to achieve LDL-C target (Table 1h).

Table 1h.

Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia in the elderly.

| Lipid-lowering treatment must aim at LDL-C levels <55, <70 and < 100 mg/dL in very high, high, and moderate risk elderly patients (≤75 years old). | I |

| In very high- and high-risk elderly patients (≤75 years old), a reduction of baseline LDL-C levels by >50% is recommended | I |

| In very high- and high-risk elderly patients >75 years old, initiation of statin therapy should be considered | IIa |

| In the presence of renal impairment and/or drug interactions, statin therapy must be initiated at a low dose, and then titrated, if needed, to attain LDL-C target | I |

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

1.5.6. Lipid management in diabetes

Patients with T2D present with atherogenic dyslipidemia characterized by elevated TC and TGs, low HDL-C and ‘normal’ or increased LDL-C levels [75,76[75,76]. Small dense LDL (sdLDL) particles are raised. This mixed dyslipidemia (high TGs, high sdLDL and low HDL-C) has been linked to increased ASCVD risk [75,76[75,76].

-

•

The primary therapeutic goal in T2D patients in relation to lipid disorders is LDL-C based on individual's ASCVD risk.

•The only exception to this rule refers to cases with very high TG levels i.e., >500 mg/dL, when TG lowering is a priority to avoid acute pancreatitis [4].

•For T2D patients at very high, high and moderate risk, LDL-C targets are: <55, <70 and < 100 mg/dL, respectively [4] (Table 1i).

•Non-HDL-C (TC minus HDL-C) represents the secondary treatment target in T2D patients. Non-HDL-C goal is 30 mg/dL higher than LDL-C target i.e., <85, <100 or <130 mg/dL for patients at very high, high, or moderate ASCVD risk, respectively.

•ApoB may also be considered as a secondary therapeutic target in T2D patients with target levels <65, <80 or <100 mg/dL, respectively [4].

•TG levels ≤150 mg/dL are considered optimal, whereas drug treatment should be considered when TG are >200 mg/dL despite statin treatment [4].

Table 1i.

Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes.

| Statins are the first-line drug of choice | I |

| Intensification of statin therapy is recommended to achieve LDL-C targets | I |

| If LDL-C goal is not reached with the maximum tolerated dose of statin dose, the addition of ezetimibe is recommended | I |

| If LDL-C remains off-target despite statin and ezetimibe therapy, a PCSK9 inhibitor should be considered if risk high or above | IIa |

| In the presence of total statin intolerance, ezetimibe monotherapy is recommended. | I |

| In the presence of total statin intolerance, if LDL-C goal is not attained with ezetimibe monotherapy, a PCSK9 inhibitor and/or bempedoic acid should be added | IIa |

| Statins are considered the first-line drug choice to reduce ASCVD risk in patients with hypertriglyceridemia | I |

| Icosapent ethyl (at a dose of 2 × 2 g/day) should be considered in combination with a statin, if TGs are 135–499 mg/dL in statin treated patients if risk high or above | IIa |

| Fenofibrate may be combined with a statin if TGs remain >200 mg/dL despite statin therapy | IIb |

| Gemfibrozil co-administration with statins is not recommended | III |

| Highly purified omega-3 fatty acids (EPA + DHA) may be added if TG levels remain >500 mg/dL despite treatment with statins and/or fenofibrate | IIb |

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk; TG: triglycerides; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

T2D represents a secondary cause of dyslipidemia; thus, it is clinically important to achieve euglycemia, which will improve related lipid disorders, and especially TG levels. Lifestyle interventions (healthy diet, physical activity, weight management and smoking cessation) are recommended to improve both dyslipidemia and ASCVD risk. However, the majority of T2D patients will require pharmacotherapy to achieve lipid targets.

Statins have been shown to slightly (by 9%) increase the risk of new-onset diabetes (NOD) [77]. Several mechanisms have been implicated in statin-induced NOD, including insulin signaling and sensitivity, pancreatic beta-cell function and adipokine secretion [78,79]. This drug effect is dose, potency and time dependent; some patients may be more prone to NOD development such as those with a family history of T2D, gestational diabetes, obesity, menopause and Asian origin [80]. However, this minor risk does not outweigh the clinical benefits of ASCVD risk reduction induced by statins. Interestingly, pitavastatin has a more favorable effect on glucose metabolism, minimizing the risk for NOD development in some studies [81].

1.5.7. Dyslipidemia in patients with HIV infection

-

•

A fasting lipid profile must be assessed in HIV-infected patients annually as well as before and after changing ART regimens (Class I)

-

•

Patients with HIV infection on ART should be treated as at least high-risk (Class IIa)

-

•

In patients with HIV infection but without established ASCVD, CKD or diabetes, the Data collection on Adverse Effects of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study equation may be considered instead of the HEART SCORE for ASCVD risk estimation [82] (Class IIb)

-

•

Atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pravastatin, fluvastatin and pitavastatin are less susceptible to drug interactions with antiretroviral treatment (Class IIa)

-

•

Ezetimibe, fenofibrate and PCSK9 inhibitors are safe and effective in patients with HIV infection [[83], [84], [85]] (Class IIa)

-

•

Lipid-lowering therapy (mostly statins) should be considered in HIV patients with dyslipidemia to achieve LDL-C goal as defined for high-risk patients. In the REPRIEVE trial, pitavastatin (at a dose of 4 mg) reduced the risk of major ASCVD events compared with placebo in participants with HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy with a low-to-moderate ASCVD risk [86]. The choice of statin should be based on potential drug-drug interactions (Class IIa).

1.6. Dyslipidemia in autoimmune diseases

Systemic inflammation is considered as a pivotal link between autoimmune diseases [such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE), psoriasis, anti-phospholipid syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)] and ASCVD risk [[87], [88], [89], [90]]. Taking into consideration that these patients can develop inflammatory vasculitis and endothelial dysfunction, particular attention should be paid to the management of traditional ASCVD risk factors [[91], [92], [93]].

-

•

In patients with autoimmune diseases, a fasting lipid profile should be measured to assess ASCVD risk and the need for statin therapy (Class IIa)

-

•

Lipids should be measured 2–4 months after starting or altering inflammatory disease-modifying therapy (Class IIa)

-

•

Patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease should be treated as at least high-risk (Class IIa)

1.7. Dyslipidemia in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)

MASLD is the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome [94] and it is associated with abdominal obesity, T2D, dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension [95]. Patients with MASLD, particularly with steatohepatitis (MASH), are at an increased risk for ASCVD [96]. Treatment of dyslipidemia should be considered of great importance for ASCVD risk reduction in those patients.

-

•

Lifestyle changes, such as diet and exercise, are the mainstay for MASLD treatment [97,98].

-

•

Statins should be used to treat dyslipidemia and reduce ASCVD risk in MASLD patients [99,100] (Class IIa)

-

•

LDL-C goals should be defined based on ASCVD risk classification.

-

•

Statins should not be used to specifically treat MASH (Class III)

Importantly, statins have been reported to improve liver biomarkers and histological features of MASLD/MASH (including fibrosis), as well as to prevent from liver cancer [[101], [102], [103], [104]] [[101], [102], [103], [104]] [[101], [102], [103], [104]].

Further efforts are made towards a more accurate, appropriate and pathophysiology-based definition of MASLD with the identification of certain MASLD phenotypes [105].

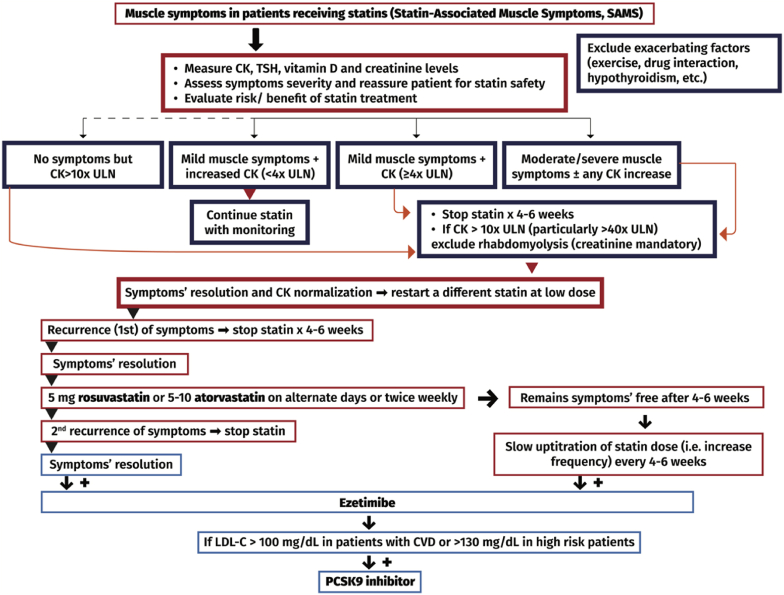

1.7.1. Statin intolerance - statin-associated muscle symptoms

SAMS are the most frequent clinically relevant adverse events of statin therapy, potentially leading to drug discontinuation and higher risk of recurrent cardiac events [106]. Most experts suggest that the definition of statin intolerance requires intolerance, either complete or partial, to at least 2 different statins, one given at a low dose [107,108]. The most common type of SAMS are muscle pains with or, most frequently, without CK elevation (Table 2a). Muscle pain is usually symmetrical and involves large proximal muscle groups including the thighs, buttocks, calves, and back muscles. They typically occur within 4–6 weeks after initiation of statin treatment and usually regress within 2–4 weeks after statin cessation [4,109]. SAMS are dose-dependent and appear independent of LDL-C reduction [110]. A score system has been developed to identify the probability of muscle symptoms to be statin-related [111].

Table 2a.

Definitions of statin-associated muscle symptoms proposed by the EAS consensus panel.

| Symptoms | CK levels | Incidence | Terminology | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle symptoms | Normal | 3–5% | Myalgia | Causality is uncertain |

| Muscle symptoms | CK > ULN and <10 x ULN | Commonly due to exercise or physical activity, but also may be statin-related | ||

| Muscle symptoms | CK > 10 x ULN and <40 x ULN | 0.1–0.2% | Myositis or myopathy | May be statin-related but may be associated with underlying muscle disease |

| Muscle symptoms | CK > 40 x ULN | 1 per 10,000 person-years | Rhabdomyolysis when associated with creatinine elevation and/or myoglobinuria | Referral for hospital admission |

| None | CK > ULN | Asymptomatic CK increase | Raised CK may be incidental finding. Consider checking thyroid function or may be exercise-related |

CK: creatine kinase; ULN: upper limit of normal.

Several factors may increase the risk of SAMS and are presented in Table 2b. It is important to exclude secondary causes of myalgias, such as hypothyroidism, low vitamin D levels, polymyalgia rheumatica, or increased physical activity, and review all concomitant drugs (i.e., CYP3A4 inhibitors, alcohol, etc.) that may interact with statins and increase the risk of SAMS [112].

Table 2b.

Conditions that increase the risk of statin-associated myopathy, c) Managing the patient with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS).

| Patient-related risk factors |

|---|

| 1. Age >80 years |

| 2. Hypothyroidism |

| 3. Impaired renal or liver function |

| 4. Female sex |

| 5. Low body mass index |

| 6. Diabetes |

| 7. Polypharmacy |

| 8. Strenuous exercise |

| 9. Vitamin D deficiency |

| 10. Acute infection |

| 11. Heavy alcohol consumption (alcohol is a direct muscle toxin) |

| 12. Drug abuse (cocaine, amphetamines, heroin) |

| 13. Impaired renal or hepatic function |

| 14. Biliary tract obstruction |

| 15. Inflammatory or inherited metabolic muscle defects (McArdle disease, carnitine palmityl transferase II deficiency) |

| 16. Surgery with high metabolic demands |

| 17. History of pre-existing/unexplained muscle/joint/tendon pain |

| Risk factors predisposing to statin interactions |

| Co-administration with: |

| 1. Cytochrome P-450 3Α4 inhibitors including: |

| Macrolide antibiotics: azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin |

| Cyclosporine |

| Antifungals: fluconazole*, itraconazole, ketoconazole* |

| Antivirals (protease inhibitors): amprenavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir |

| Amiodarone |

| Calcium antagonists (diltiazem, verapamil) [weak inhibitors] |

| Warfarin* |

| Colchicine |

| Grapefruit juice (if > 1 L/day) |

| 2. Glucuronidation inhibitors: gemfibrozil |

| 3. Nicotinic acid |

*also metabolized through the cytochrome P-450 2C9.

The management of the statin-intolerant patient due to muscle symptoms is described in Table 2c & Fig. 3. Non-statin LDL-C lowering therapy includes:

-

•

Ezetimibe 10 mg daily: reduces LDL-C by 15–20% and usually does not trigger muscle symptoms. The combination of ezetimibe with low-dose statins can reduce LDL-C by 40–50%.

-

•

Bile acid sequestrants: Colesevelam can be combined with ezetimibe or/and statin. The maintenance dose is 3 × 625 mg tablets, twice daily, taken with meals. Colesevelam lowers LDL-C by 10–16%.

-

•

PCSK9 inhibitors: evolocumab, alirocumab and inclisiran, which reduce LDL-C by 50–60% [113,114].

-

•

Bempedoic acid: Based on pooled data analysis from 4 phase III CLEAR trials, involving statin-intolerant patients with hypercholesterolemia, bempedoic acid (n = 394) reduced LDL-C by 26.5% (95%CI -29.7 to −23.2%; p < 0.001) compared with placebo (n = 192) at week 12 [115]. Furthermore, bempedoic acid + ezetimibe fixed-dose combination led to significantly lower LDL-C by 39.2% (95% CI -51.7 to −26.7%; p < 0.001) compared with placebo. Bempedoic acid was well-tolerated with less muscle-related adverse events than placebo [115].

-

•

Coenzyme Q10 administration and vitamin D supplementation in SAMS. The existing data do not clearly support supplementation of coenzyme Q10 or vitamin D in patients with SAMS [116,117].

-

•

Certain nutraceuticals (at certain doses) may represent an alternative therapeutic option in statin-intolerant patients [[118], [119], [120]] [[118], [119], [120]] [[118], [119], [120]].

Table 2c.

Managing the patient with statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS).

| 1. Reassess the need of statin therapy |

| 2. Reassure patient that statins are very safe and effective drugs and that muscle symptoms are reversible |

| 3. Implement aggressive lifestyle changes |

| 4. Eliminate contributing factors (e.g., hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency, other drugs that may interact with statins) |

| 5. Confirm the diagnosis |

| a) dechallenge: discontinue statin and wait (usually 4–6 weeks) until complete resolution of symptoms + normalization of CK |

| b) rechallenge: try a second (usually different) statin at low dose (after dechallenge). If this is tolerated: |

| b1) statin can be up-titrated to achieve LDL-C goal, or as much LDL-C reduction can be achieved with minimal muscle complaints, or |

| b2) statin remains at low or moderate dose and ezetimibe is added |

| 6. If a second statin causes recurrence of muscle symptoms, try low dose of atorvastatin (5–10 mg) or rosuvastatin (5 mg) on alternate days or twice weekly. This approach lowers LDL-C by 25–35% and is tolerated by the majority (∼80%) of intolerant to statin patients. For further LDL-C reduction, statin should be combined with ezetimibe |

| 7. If alternate low dose of statin is not tolerated (i.e., the patient is intolerant to 3rd introduction of statin), then no other attempt with statin should be tried |

| 8. In statin-intolerant patients (“totally” or “partially”) consider: |

| a) ezetimibe and |

| b) a PCSK9 inhibitor (alirocumab or evolocumab) if, despite low statin dose (in partially intolerant patients) + ezetimibe, LDL-C remains >100 mg/dL in patients with established cardiovascular disease or >130 mg/dL in high-risk patients |

| c) bempedoic acid is an established alternative to statin treatment in patients with SAMS, and should be administered, if available |

CK: creatine kinase; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Fig. 3.

Algorithm for the management of patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms. CK: creatine kinase; ULN: upper limit of normal; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CVD: cardiovascular disease; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Specific forms of dyslipidemia.

Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HeFH).

HeFH is a common autosomal dominant genetic disease, affecting approximately 1 in 200–300 adults [121]. HeFH is caused by mutations in one of the genes critical for LDL receptor-mediated catabolism of LDL, involving the LDLR, apoB and PCSK9 [122]. The main characteristic of patients with HeFH is the increased incidence of early onset ASCVD [123].

The recommendations for the assessment and management of dyslipidemia in patients with HeFH are presented in Table 3a.

Table 3a.

Recommendations for the assessment and management of dyslipidemia in patients with Heterozygous FH (HeFH).

| The Dutch Lipid Clinic Network criteria must be used to establish the diagnosis of HeFH | I |

| First-degree relatives of patients with HeFH must be evaluated for the presence of FH | I |

| In patients with HeFH and established ASCVD, diabetes or stage 4–5 CKD, an LDL-C target <55 mg/dL and a ≥50% reduction from baseline LDL-C levels is recommended | I |

| In patients with HeFH without established ASCVD or other major risk factors, the LDL-C target is < 70 mg/dL | I |

| The most potent statins at the maximal tolerated dose (atorvastatin 40–80 mg or rosuvastatin 20–40 mg), ezetimibe and PSCK9 inhibitor (if needed) must be used to achieve the LDL-C target | I |

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CKD: chronic kidney disease; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HoFH).

HoFH occurs in one of 160,000–300,000 births [124]. HoFH clinical manifestation is characterized by extensive xanthomas, marked premature and progressive ASCVD and TC > 500 mg/dL. Most patients develop CHD and aortic stenosis before the age of 20 and die before the age of 30 years.

The recommendations for LDL-C targets in patients with HoFH are presented in Table 3b.

Table 3b.

Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia in patients with Homozygous FH (HoFH).

| In primary prevention, HoFH patients should achieve an LDL-C <70 mg/dL and ≥50% decrease from baseline | IIa |

| In primary prevention, in individuals at very high risk an LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL (<1.4 mmol/L) should be considered | IIa |

| In secondary prevention, an LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and an LDL-C goal of <55 mg/dL (1.4 mmol/L) is recommended | I |

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Classical management of HoFH involves a combination of healthy lifestyle, high-intensity statin + ezetimibe started as early as possible, and lipoprotein apheresis (preferably by the age of 5 and not later than 8 years). Nowadays, several drug therapeutic options are available for patients with HoFH. Patients may need 3 or more drugs to reach LDL-C goals [[125], [126], [127]] [[125], [126], [127]] [[125], [126], [127]].

Evinacumab, which has been approved for the treatment of HoFH by FDA and EMA [128,129], is a monoclonal antibody against the angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) that decreases LDL-C levels in patients with HoFH via an LDL-R independent mechanism [130]. In a phase III randomized controlled trial involving 65 statin-treated patients with HoFH, evinacumab administered intravenously every 4 weeks significantly decreased LDL-C compared with placebo (between group difference −49.0%, p < 0.001) [131].

Lomitapide has also been approved for the treatment of HoFH. It inhibits the action of microsomal transfer protein (MTP), which catalyzes the transport of TGs, cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine esters between biological membranes [132] and is essential for the hepatic synthesis and secretion of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) [133]. Lomitapide does not require the expression of a functional LDLR to reduce LDL-C levels. This drug is orally administered, absorbed easily, and undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver. Lomitapide use should be accompanied by a low-fat diet (fat <20% of total calories) to avoid fat malabsorption and diarrhea. Treatment with lomitapide increases serum transaminases and predisposes to hepatic steatosis and steatorrhea.

1.7.2. Familial combined hyperlipidemia (FCHL)

FCHL constitutes the most prevalent familial hyperlipidemia, with an incidence of 1–2% of the general population and 20–35% of patients with a history of myocardial infarction [134]. FCHL is an oligogenic entity with variable penetrance [135,136]. The usual phenotype of FCHL consists of mixed hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia in combination with high levels of apoB100 [137]. This phenotype variability might also be observed in the same individual at different time periods.

The combination of serum apoB100 > 120 mg/dL and TGs >133 mg/dL as well as family history of premature CHD are sufficient for the diagnosis of FCHL [138].

Hypolipidemic treatment initiation and goals in patients with FCHL are based on the HellenicSCORE II tables (Fig. 1) [4,5].

Familial Dysbetalipoproteinemia

Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia is characterized by the marked accumulation of cholesterol-enriched remnant lipoproteins particles of hepatic and intestinal origin. It is a not so rare autosomal recessive disease with varied penetration causing an extremely atherogenic dyslipoproteinemia [134,135]. Patients are homozygous for apoE2 isoform.

Lipidemic profile is characterized by an increase in serum TC and TG levels of about 620–885 mg/dL. In severe cases, patients present with xanthomas on palms and wrists as well as tuberous xanthomas over the elbows and knees.

The diagnosis of familial dysbetalipoproteinemia is traditionally based on plasma ultracentrifugation and electrophoresis, revealing a broad β-VLDL bundle. The ratios of TC/apoB >6.2 together with TG/apoB <10 can be used for diagnosis [139].

Typical therapy consists of a statin and the addition of a fibrate if plasma TG levels remain elevated.

1.7.3. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D)

LAL-D is a rare (1:175,000) autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease. Mutations of the LIPA gene markedly impair the activity of LAL, which catalyzes the intracellular hydrolysis of cholesteryl esters and TG of LDL particles into free cholesterol and free fatty acids [140,141].

LAL-D manifests with 2 phenotypes according to the degree of LAL deficiency. The most severe phenotype with complete LAL deficiency (Wolman disease) presents early in infancy leading to death in the first 12 months [142]. The less severe phenotype is characterized by residual activity of LAL, occurs in children and adults and is characterized by high levels of LDL-C and decreased HDL-C, transaminase elevation and hepatomegaly [142]. These patients have a progressive liver disease that tends to recur even after liver transplant. The diagnosis of LAL-D can be established by identification of deficient LAL activity or mutations in the LIPA gene.

In 2015 the long-term enzyme replacement therapy with recombinant human enzyme LAL sebelipase alfa was approved for the management of LAL-D, administered intravenously every 2 weeks [143].

1.7.4. Sitosterolemia

Sitosterolemia is an extremely rare recessively inherited disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in ABCG5 or ABCG8 and characterized by increased concentration of plant sterols, such as sitosterol [144]. Patients with sitosterolemia have similar clinical manifestations with patients with FH, such as tendon xanthomas, increased LDL-C, and premature coronary atherosclerosis. Some patients are presented with thrombopenia, hemolysis, splenomegaly and arthralgia/arthritis [145].

Dietary restriction of plant sterols and cholesterol is recommended. Ezetimibe and BAS decrease the absorption of plant sterols from the intestine and increase secretion from the liver, respectively, and therefore are considered first-line treatment [145,146].

1.7.5. Familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS)

FCS is a rare hereditary, autosomal recessive disorder of the metabolism of TG-rich lipoproteins with an incidence of 1/1,000,000 worldwide, usually occurring during childhood [147]. Disease-related mutations have been reported in 6 genes [i.e., LPL, APOCII, APOA5, LMF1, GPIHBP1, and G3PDH1 (GPD1)] [148]. It should be mentioned that the prevalence of FCS, and in general for all recessive diseases including FH, is much higher in specific ethnic groups, such as French Canadians, Afrikaner in South Africa and people from middle east countries [149,150].

Clinical manifestations of FCS involve severe hypertriglyceridemia, abdominal pain and recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis that may lead to chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic insufficiency and type 3c diabetes [151]. Other clinical features include transient eruptive xanthomas of the trunk and extremities, retinal lipemia, hepatosplenomegaly, as well as neurological manifestations [152].

Another more common clinical entity, characterized by high TG levels, that is indistinguishable from FCS, is the multifactorial chylomicronemia syndrome (MCS) [147]. A diagnostic score based on 8 biological/clinical parameters, the FCS score [152], has been proposed to help distinguish FCS and MCS.

The main therapeutic goal is TG-lowering <500 mg/dL, in order to reduce the risk for pancreatitis rather than ASCVD risk. A strict hypolipidemic diet is often the cornerstone management. Volanesorsen, a chimeric antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) targeting apoCIII mRNA, has been approved by the EMA for the treatment of familial hyperchylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) [153]. Approval was based on the results of the APPROACH trial in 66 participants with serum TGs ≥750 mg/dL who were given once weekly volanesorsen 300 mg subcutaneously for 52 weeks [154]. Volanesorsen reduced serum TGs by up to 70%, with the main side effect being a reduction in platelet numbers [154]. Importantly, olezarsen, a novel N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-conjugated ASO with the same target with volanesorsen, seems to have a better efficacy and safety profile without any adverse effects in platelet count, liver, or renal function [155,156]. We need to wait for the results of phase III studies with olezarsen as well as to the decision of the FDA and EMA regarding the approval (or not) of this drug.

1.7.6. Primary genetic causes of very low HDL levels

The primary genetic causes of very low HDL levels include: 1) The Tangier disease, a rare monogenic autosomal recessive disorder due to mutations in both alleles of the ABCA1 gene [157], 2) Familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia, a very rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mutations that cause apoA-I deficiency [158], and 3) the very rare autosomal recessive disorder lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency, which is associated with the development of two syndromes: (i) familial LCAT deficiency (FLD) and (ii) fish-eye disease (FED) [159]. Patients with primary genetic causes of very low HDL levels generally have an increased risk of ASCVD [158].

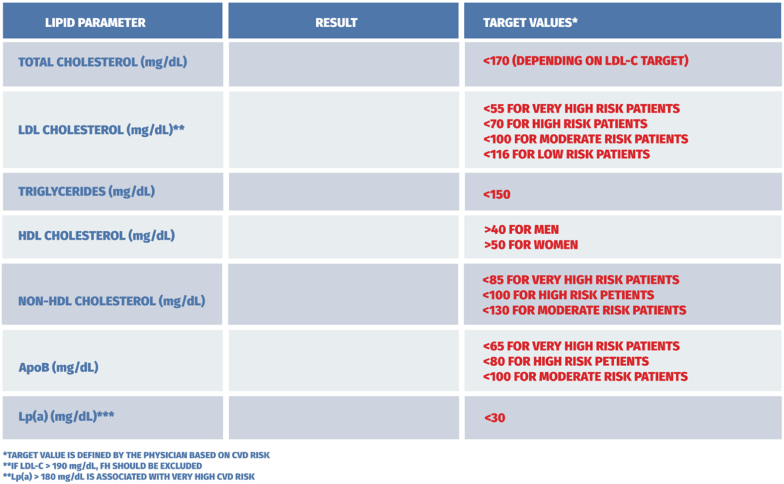

1.7.7. Therapeutic targets and treatment algorithm in patients with dyslipidemia

Results from recent studies and systematic reviews have confirmed the dose-dependent reduction in ASCVD with LDL-C lowering; the greater the LDL-C reduction, the greater the ASCVD risk reduction, i.e. the lower, the better [10,11,45,160]. Of note, the benefits related to LDL-C reduction are not specific for statin therapy. Thus, non-statin treatments should be considered in very high- or high-risk patients not achieving their LDL-C target with a statin [161]. No level of LDL-C below which benefit ceases or harm occurs has been defined. Therefore, it seems appropriate to reduce LDL-C as low as possible, at least in patients at very high ASCVD risk.

In patients with elevated TGs (>200 mg/dL) there are increased levels of circulating TG-rich lipoproteins that are also associated with increased ASCVD risk. In this case, non-HDL-C (TC minus HDL-C) captures all atherogenic lipoproteins [LDL-C, TG-rich lipoproteins and Lp(a)] and can be calculated in the non-fasting state. Non-HDL-C is a secondary treatment target for these patients. In patients with TG levels >500 mg/dL, TG lowering is the priority due to the increased risk of acute pancreatitis (Table 4a).

Table 4a.

Treatment targets in dyslipidemia.

| Recommendations | Class of recommendation |

|---|---|

| LDL-C lowering is the main treatment target in almost all patients | I |

| Non-HDL-C is a secondary treatment target in patients with TGs >200 mg/dL. Non-HDL-C target = LDL-C target +30 mg/dL | IIa |

| TG lowering is a treatment priority in patients with TGs>500 mg/dL | IIa |

| HDL-C is not a treatment target | III |

We suggest 4 ASCVD risk groups (Table 4b) and respective LDL-C treatment goals (Table 4c & Fig. 4). Proposed treatment algorithm is depicted in Fig. 5.

Table 4c.

LDL-C treatment goals for different ASCVD risk groups.

| ASCVD Risk group | LDL-C treatment target | Initiation of lipid-lowering drug treatment | Class of recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Very high ASCVD risk | <55 mg/dL AND ≥50% LDL-C reduction from baseline | Immediate + therapeutic lifestyle changes | I |

| II. High ASCVD risk | <70 mg/dL AND ≥50% LDL-C reduction from baseline | Immediate + therapeutic lifestyle changes | I |

| III. Moderate ASCVD risk group | <100 mg/dL | 3 months following therapeutic lifestyle changes | I |

| IV. Low ASCVD risk group | <116 mg/dL | 3–6 months following therapeutic lifestyle changes | IIa |

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Fig. 4.

ASCVD risk groups and LDL-C targets. ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CKD: chronic kidney disease; FH: familial hypercholesterolemia.

Fig. 5.

Proposed treatment algorithm for the management of patients with dyslipidemia - 2023. ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CKD: chronic kidney disease; FH: familial hypercholesterolemia.

Statins are the mainstay of treatment. The intensity of statin treatment is shown in Table 4d. Initiation of high intensity statin treatment is recommended in patients at very high and high risk. In patients with established ASCVD and baseline LDL-C>110 mg/dL, combination therapy with high intensity statin treatment + ezetimibe (preferably in a single pill) should be started immediately.

Table 4d.

Intensity of statin treatment.

| High intensity (LDL-C reduction ≥50%) | Moderate intensity (LDL-C reduction 30–50%) | Low intensity (LDL-C reduction <30%) |

|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin 40–80 mg | Atorvastatin 10–30 mg | Simvastatin 10 mg |

| Rosuvastatin 20–40 mg | Rosuvastatin 5–10 mg | Pravastatin 20 mg |

| Simvastatin 20–40 mg | Lovastatin 20 mg | |

| Pravastatin 40 mg | Fluvastatin 40 mg | |

| Lovastatin 40 mg | Pitavastatin 1 mg | |

| Fluvastatin XL80 mg | ||

| Pitavastatin 2–4 mg |

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Proposed thresholds for PCSK9 inhibitor initiation are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Eligible patients for PCSK9 inhibitor initiation. PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CKD: chronic kidney disease; FH: familial hypercholesterolemia.

Data indicates that achieving even very low LDL-C levels is safe for patients. An analysis of patients who achieved LDL-C levels below 25 mg/dL or even below 15 mg/dL during treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors showed that even with these values, no increased risk of adverse drug effects or adverse events related to neurocognitive disturbances is observed [50].

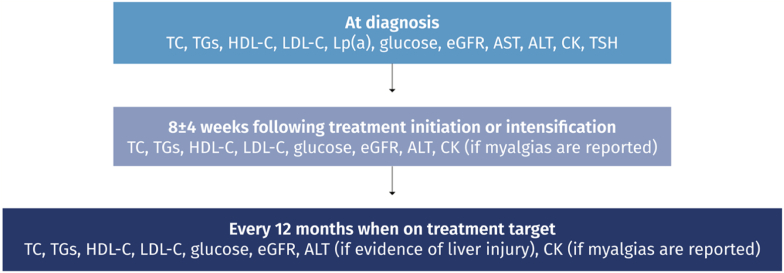

Following initiation of lipid-lowering therapy, lipid levels should be evaluated every 8 ± 4 weeks to adjust therapy until target lipid levels are reached. In patients with adequate on-treatment lipid levels, annual lipid profile testing is recommended. In addition, CK and ALT levels should be evaluated prior to the initiation of lipid-lowering therapy. Single ALT level retesting is indicated at 8–12 weeks after lipid-lowering therapy initiation or dose escalation. Further routine CK and ALT level retesting is not necessary unless prompted by clinical symptoms (Table 1b & Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Laboratory follow-up in patients on hypolipidemic drug treatment.

There is an imperative need for laboratories not to mark low values as abnormal, using ranges of acceptable values. In some cases, this approach may prompt patients to discontinue treatment, leading to worse outcomes. For that reason, these guidelines suggest a recommendation to standardize laboratory report forms so as they indicate target ranges in accordance with the most recent recommendations and medical knowledge and do not generate a risk of potential errors by patients or physicians. Fig. 8 depicts a proposed way of reporting lipid testing results in adults and children/adolescents.

Fig. 8.

Proposed reporting of lipid test results in adults.

2. Conclusion

Lipid-lowering treatment is of paramount importance in ASCVD prevention. Implementation of relevant guidelines remains challenging, and most patients do not achieve LDL-C targets [162]. In this regard, local guidelines may improve physician awareness, reduce clinical inertia, and hopefully improve ASCVD outcomes.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Visseren F.L.J., Mach F., Smulders Y.M., Carballo D., Koskinas K.C., Bäck M., et al. ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart Journal 2021. 2021;42:3227–3337. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stergiou G.S., Ntineri A., Menti A., Kalpourtzi N., Vlachopoulos C., Liberopoulos E.N., et al. Twenty-first century epidemiology of dyslipidemia in Greece: EMENO national epidemiological study. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2023;69:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hjc.2022.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liberopoulos E., Rallidis L., Spanoudi F., Xixi E., Gitt A., Horack M., et al. Attainment of cholesterol target values in Greece: results from the Dyslipidemia International Study II. Aoms. 2019;15:821–831. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2018.73961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mach F., Baigent C., Catapano A.L., Koskinas K.C., Casula M., Badimon L., et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020. 2019;41:111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panagiotakos D.B., Magriplis E., Zampelas A., Contributors Advisory Committee. The recalibrated HellenicSCORE based on newly derived risk factors from the hellenic national nutrition and health Survey (HNNHS); the HellenicSCORE II. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2021;62:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.hjc.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett D.K., Blumenthal R.S., Albert M.A., Buroker A.B., Goldberger Z.D., Hahn E.J., et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019. 2019;140 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinella M.E., Lazarus J.V., Ratziu V., Francque S.M., Sanyal A.J., Kanwal F., et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966–1986. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stampfer M.J., Hu F.B., Manson J.E., Rimm E.B., Willett W.C. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007063430103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiuve S.E., McCullough M.L., Sacks F.M., Rimm E.B. Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men: benefits among users and nonusers of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation. 2006;114:160–167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabatine M.S., Giugliano R.P., Keech A.C., Honarpour N., Wiviott S.D., Murphy S.A., et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz G.G., Steg P.G., Szarek M., Bhatt D.L., Bittner V.A., Diaz R., et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097–2107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgerald K., White S., Borodovsky A., Bettencourt B.R., Strahs A., Clausen V., et al. A highly durable RNAi therapeutic inhibitor of PCSK9. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:41–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leqvio- inclisiran E.M.A. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/leqvio

- 14.FDA . FDA approves add-on therapy to lower cholesterol among certain high-risk adults. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-add-therapy-lower-cholesterol-among-certain-high-risk-adults [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuel E., Watford M., Egolum U.O., Ombengi D.N., Ling H., Cates D.W. Inclisiran: a first-in-class siRNA therapy for lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Ann Pharmacother. 2022 doi: 10.1177/10600280221105169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirillo A., Catapano A.L. Inclisiran: how widely and when should we use it? Curr Atherosclerosis Rep. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11883-022-01056-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirillo A., Catapano A.L. New insights into the role of bempedoic acid and ezetimibe in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2022;29:161–166. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nissen S.E., Lincoff A.M., Brennan D., Ray K.K., Mason D., Kastelein J.J.P., et al. Bempedoic acid and cardiovascular outcomes in statin-intolerant patients. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1353–1364. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2215024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bempedoic acid: another cholesterol-lowering drug. Drug Therapeut Bull. 2022;60:120–124. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2022.000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fruchart J.-C., Hermans M.P., Fruchart-Najib J. Selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha modulators (SPPARMα): new opportunities to reduce residual cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease? Curr Atherosclerosis Rep. 2020;22:43. doi: 10.1007/s11883-020-00860-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das Pradhan A., Glynn R.J., Fruchart J.-C., MacFadyen J.G., Zaharris E.S., Everett B.M., et al. Triglyceride lowering with pemafibrate to reduce cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2022 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210645. NEJMoa2210645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EMA confirms omega-3 fatty acid medicines are not effective in preventing further heart problems after a attack. European Medicines Agency; 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-confirms-omega-3-fatty-acid-medicines-are-not-effective-preventing-further-heart-problems-after [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholls S.J., Lincoff A.M., Garcia M., Bash D., Ballantyne C.M., Barter P.J., et al. Effect of high-dose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: the STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:2268. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhatt D.L., Steg P.G., Miller M., Brinton E.A., Jacobson T.A., Ketchum S.B., et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA approves use of drug to reduce risk of cardiovascular events in certain adult patient groups. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-use-drug-reduce-risk-cardiovascular-events-certain-adult-patient-groups. Accessed on 15/September/2022 [n.d].

- 26.Vazkepa. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vazkepa. Accessed on 15-September-2022 [n.d].

- 27.Hobbs H.H., White A.L. Lipoprotein(a): intrigues and insights. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:225–236. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsimikas S., Fazio S., Viney N.J., Xia S., Witztum J.L., Marcovina S.M. Relationship of lipoprotein(a) molar concentrations and mass according to lipoprotein(a) thresholds and apolipoprotein(a) isoform size. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12:1313–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kronenberg F., Mora S., Stroes E.S.G., Ference B.A., Arsenault B.J., Berglund L., et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3925–3946. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordestgaard B.G., Langsted A. Lipoprotein (a) as a cause of cardiovascular disease: insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1953–1975. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R071233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgess S., Ference B.A., Staley J.R., Freitag D.F., Mason A.M., Nielsen S.F., et al. Association of lLPA variants with risk of coronary disease and the implications for lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies: a mendelian randomization analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:619–627. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke R., Peden J.F., Hopewell J.C., Kyriakou T., Goel A., Heath S.C., et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson G., Parhofer K.G. Current role of lipoprotein apheresis. Curr Atherosclerosis Rep. 2019;21:26. doi: 10.1007/s11883-019-0787-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viney N.J., van Capelleveen J.C., Geary R.S., Xia S., Tami J.A., Yu R.Z., et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet. 2016;388:2239–2253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lp(a)HORIZON achieves 50% enrollment in trial to assess the safety and efficacy of pelacarsen in reducing recurrent cardiovascular events.https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/lpa-horizon-achieves-50-enrollment-in-trial-to-assess-the-safety-and-efficacy-of-pelacarsen-in-reducing-recurrent-cardiovascular-events-301346042.html. Accessed on 12-October-2022 n.d. .

- 36.O'Donoghue M.L., López J.A.G., Knusel B., Gencer B., Wang H., Wu Y., et al. Study design and rationale for the olpasiran trials of cardiovascular events and lipoprotein(a) reduction-dose finding study (OCEAN(a)-DOSE) Am Heart J. 2022;251:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2022.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AMGEN ANNOUNCES POSITIVE TOPLINE PHASE 2 DATA FOR INVESTIGATIONAL OLPASIRAN IN ADULTS WITH ELEVATED LIPOPROTEIN(a). https://www.amgen.com/newsroom/press-releases/2022/05/amgen-announces-positive-topline-phase-2-data-for-investigational-olpasiran-in-adults-with-elevated-lipoproteina. Accessed on 12-October-2022 n.d. .

- 38.Schwartz G.G., Olsson A.G., Ezekowitz M.D., Ganz P., Oliver M.F., Waters D., et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cannon C.P., Braunwald E., McCabe C.H., Rader D.J., Rouleau J.L., Belder R., et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collet J.-P., Thiele H., Barbato E., Barthélémy O., Bauersachs J., Bhatt D.L., et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2021. 2020;42:1289–1367. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cleland J.G.F., McMurray J.J.V., Kjekshus J., Cornel J.H., Dunselman P., Fonseca C., et al. Plasma concentration of amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in chronic heart failure: prediction of cardiovascular events and interaction with the effects of rosuvastatin: a report from CORONA (Controlled Rosuvastatin Multinational Trial in Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1850–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonagh T.A., Metra M., Adamo M., Gardner R.S., Baumbach A., Böhm M., et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021. 2021;42:3599–3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.EVOlocumab in stable heart failure with reduced ejection fraction of ischemic Etiology: EVO-HF Pilot. 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03791593 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baigent C., Blackwell L., Emberson J., Holland L.E., Reith C., Bhala N., et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]