Abstract

Aim:

This study describes the process of updating the cerebral palsy (CP) common data elements (CDEs), specifically identifying tools that capture the impact of chronic pain on children’s functioning.

Method:

Through a partnership between the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the CP CDEs were developed as data standards for clinical research in neuroscience. Chronic pain was underrepresented in the NINDS CP CDEs version 1.0. A multi-step methodology was applied by an interdisciplinary professional team. Following an adapted CP chronic pain tools’ rating system, and a review of psychometric properties, clinical utility, and compliance with inclusion/exclusion criteria, a set of recommended pain tools was posted online for external public comment in May 2022.

Results:

Fifteen chronic pain tools met inclusion criteria, representing constructs across all components of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

Interpretation:

This paper describes the first condition-specific pain CDEs for a pediatric population. The proposed set of chronic pain tools complement and enhance the applicability of the existing pediatric CP CDEs. The novel CP CDE pain tools harmonize the assessment of chronic pain, addressing not only intensity of chronic pain, but also the functional impact of experiencing it in everyday activities.

Graphical Abstract

Through a partnership between the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the cerebral palsy (CP)-specific common data elements (CDEs) were developed as part of the NINDS project to develop data standards for clinical research in neuroscience. Since the initial posting of version 1.0 in December 2016,1 the NINDS CP CDE Oversight Committee has continued to review and update the CP CDEs.

A CDE is a precisely defined question paired with a set of structured responses, used systematically across different sites, studies, or clinical trials to ensure consistent data collection.2,3 The CDE project is not a database: it is a collection of metadata and data standards. CDEs are dynamic and evolve over time. The CDEs consist of specific terminology with identification of common definitions, standardized case-report forms, and standardized tools/instruments. So far, the NINDS CDE website has contained metadata and data standards for 25 conditions (https://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov). The overarching aim of developing condition-specific CDEs is to accelerate research, enable prompt uptake of evidence into clinical practice, and to deliver the best quality of care to individuals who require it. Beyond research applications, the open-access comprehensive set of CP CDEs serves as a clinical tool for teaching, standardizing clinical care, harmonizing data collection and data reporting, and guiding quality-improvement projects, among others.4 Globally, the scientific community can access and use these generic or condition-specific CDEs.

Across the NINDS CDE disease groups, review and evaluation of the existing CDEs, case-report forms, and instruments occur regularly, with updates reflecting evolving knowledge in the disease groups, research gaps, and gaps within the CDEs themselves. A gap identified in the NINDS CP CDEs version 1.0 was a lack of tools addressing the functional impact of chronic pain in children and young people with CP.1 Chronic pain in children and young people with CP contributes to a lower quality of life and limits activity and participation beyond the difficulties related to their disabilities.5–7 Pain in children and young people with CP is common and as high as 77%.7–10 Cognitive and communication challenges, as well as multiple pain etiologies, complicate assessment, intervention, and management.8,11

Children with chronic pain experience more anxiety and depression than those without it and they experience more negative physical symptoms as adults.12,13 Moreover, chronic pain has detrimental effects on the individual’s personal and social life, also affecting the family environment.14,15 However, for children and young people with CP, the complex interplay of disability and pain with personal, social, and family life is not clear. As such, a biopsychosocial approach for chronic pain assessment and treatment outcomes is advisable in children and young people with CP.13,15,16 Thus, because of the complexity of the biopsychosocial factors on chronic pain in children with CP, a stepwise approach to identifying tools that capture these factors requires a critical evaluation of potential tools and identification of gaps in measures of them.

Over the past decade, special attention has been paid to chronic pain evaluation and assessment tools for children, young people, and adults with CP,13,17–19 recognizing the major role that chronic pain plays in the health and well-being of people with CP. Briefly, several reviews and consensus processes have identified (1) a paucity of evidence to guide tool selection for chronic pain in CP across the lifespan; (2) unique challenges of collecting self-reported pain data in this population; (3) a need to standardize chronic pain screening and assessment at local, regional, and global levels; (4) a lack of validated CP-specific pain tools for pediatric populations; and (5) that the functional impact of living with chronic pain in CP is overlooked.17–21 Hence, comprehensive pain assessment and evaluation remain a key area to address in CP to identify interventions to reduce chronic pain.

To fill the gap of identifying comprehensive and validated tools of chronic pain in children and young people with CP in the CP CDEs version 1.0, the NINDS CP CDE Oversight Committee Pain Working Group gathered information about existing pain tools and developed the first recommended CP CDE chronic pain tools/instruments for children and young people with CP. The specific objectives were to (1) recommend a set of tools representing the impact of chronic pain on function in children and young people with CP—guided by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF);22 (2) identify valid and reliable chronic pain tools for routine use across clinical studies and clinical practice in children and young people with CP; and (3) identify gaps in tools that could be addressed in future research.

METHOD

History of NINDS CP CDEs

The NINDS CDE project for CP began in 2015. An organizing committee with representatives from the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine and the NINDS convened at an international meeting. The Academy’s leadership created a Steering Committee and worked with the Academy’s Research Committee to invite experts in CP into working groups, each of which was composed of five to seven members with knowledge and experience relevant to CP-related health domains. These experts included international epidemiologists, clinicians, clinical researchers, educators, and clinical trial experts. In December 2016, the project was completed with an academic publication and the online posting of the CP CDEs. For further details see Schiariti et al.1

NINDS CDE terminology

Across all NINDS CDE disease groups, CDEs and tools/instruments are classified with regard to level of recommendation for use in research studies. Consistent with this guidance across the NINDS CDE project, the CP CDE Pain Working Group sought to classify any recommended CDE or tool for pain as ‘Core’, ‘Supplemental – Recommended’, ‘Supplemental’, or ‘Exploratory’ (Table 1).1,23

TABLE 1.

CDE classifications

| Core: a data element for recording essential information applicable to any CP study, including therapeutic areas and study designs; consistent with all NINDS disease-specific CDE sets. |

| Supplemental – Highly Recommended: a data element recommended for use whenever applicable. |

| Supplemental: a data element that has some evidence of validity and is commonly collected in clinical studies in CP; use depends upon study design. |

| Exploratory: a data element that is emerging or that requires further validation in CP. |

Abbreviations: CDE, common data element; CP, cerebral palsy; NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Conceptual framework

Managing the depth and breadth of data related to chronic pain and CP required an organizational framework to help visualize the essential data categories. Given the multidimensional impact of living with and experiencing CP on developmental trajectories of children and young people and their families, the ICF was used to map out the content of the tools within the framework that met inclusion criteria for this study.

Study design

The study used a multi-step methodology to address the specific objectives. First, all pain CDEs and tools listed in the NINDS CDEs repository data were reviewed. Simultaneously, a scoping review was performed in four electronic search engines to identify pain assessment tools used in studies with children with CP. Key search terms included ‘chronic pain’, ‘cerebral palsy’, and ‘clinical assessment tool’, with inclusion of studies published between January 2000 and January 2020. (An example search strategy is provided in Appendix S1.) Second, chronic pain tools meeting the inclusion criteria were then reviewed for psychometric properties, content analysis, and reference to other pain tools or manuscripts that may have not been identified in the original search. The category(ies) of each pain tool assessed was determined with the representative domain(s) of the ICF. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews, provided in Appendix S2, guided our methodology. Lastly, the group reviewed all tools and reached a consensus on a set of validated tools that comprehensively represented the impact of chronic pain on functioning in children and young people with CP (Figure S1).

The initial step to compile a list of chronic pain tools took place in 2020 (scoping review). The literature search was complemented from additional sources, including the NINDS CDEs across disorders related to pain, and the pain measures from the National Institutes of Health HEAL Initiative.24 Review of assessment tools occurred over an 18-month period and included individual review of the tools, discussion of each tool, and group consensus about inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, the group sorted candidate tools into pain domain(s), ICF components, and recommendations for CDEs. In May 2022, a set of chronic pain tools were posted for public review on the NINDS CP CDEs webpage (Appendix S3 shows the timeline of the project.)

Chronic pain definition

The CP CDE Pain Working Group adopted the definition of chronic pain as pain lasting more than 3 months, clinically identified as (1) chronic musculoskeletal pain, such as persistent or recurrent pain that arises as part of CP causing structural changes to bone(s), joint(s), muscle(s), or related soft tissue(s); (2) chronic visceral pain that frequently originates from the internal organs of the abdominal (often caused by gastro-esophageal reflux) and pelvic cavities; and (3) postsurgical and posttraumatic pain that persists beyond normal healing, frequently after surgery and some types of injury.25

Target population

The target population of this initiative was children and young people aged 0 to 18 years with a diagnosis of CP or considered to be at risk of developing CP.

CP CDE pain tools: identification and selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Pain tools were reviewed and included if (1) the assessment was developed specifically for chronic pain; (2) the assessment was developed for or used in pediatric populations (children 0–18 years); (3) the main focus of the assessment was pain, or most questions included were about pain (i.e. more than three questions); (4) the assessment fitted within one of the main pain categories (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS] categories, or pain location); and (5) the assessment was available in English.

Pain tools were excluded if (1) the assessment was developed specifically for a different diagnosis; (2) pain was due to an event outside the scope of the diagnosis (i.e. trauma); (3) the main focus of the assessment was not on pain or had very limited questions about pain (i.e. one to three questions); (4) the assessment did not fit within one of the pain categories (i.e. PROMIS categories and location); (5) the assessment lacked validity for use with children or young people with CP; and (6) the assessment was a duplicate. Figure S1 summarizes the multi-step study methodology.

Psychometric properties and clinical utility rating system

Our team followed a specific guideline to assess the psychometric properties and clinical utility of each proposed tool, adapted from PhenX (Phenotypes and eXposures) criteria and the Clinical Utility Attributes Questionnaire.26–28 Specifically, the following characteristics were considered: the main purpose of the tool was to assess chronic pain, had good/acceptable validity, had good to excellent/high reliability, and had good/acceptable clinical utility (see criteria in Appendix S4). Of note, psychometric studies on children and young people with CP were given priority, but this alone was not a reason for exclusion.

Clinical utility was defined as good/acceptable if the tool was easy to score and interpret, it was not too time consuming, provided useful information about how pain affects functioning, assessed chronic pain/pain behavior, and could be used with individuals with CP, at any level of functioning (i.e. any Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] level).

Categories of chronic pain

To categorize the tools, we also used the National Institutes of Health PROMIS pain-related domains.29 These domains include items for pain intensity, interference, behavior, and quality. In addition, we considered pain location as an important domain. Descriptions of PROMIS pain-related domains are given in Appendix S5.

Public review

In May 2022, the recommended set of CP pain CDE Notice of Copyright forms were posted on the NINDS CP CDE website for public review. Notices of Copyright included detailed descriptions of every proposed tool, with psychometric characteristics. We received feedback for some of these Notices. Of note, no new pain measures were put forward for consideration during the public review.

RESULTS

Overall, 184 assessments were reviewed (Figure S1). After removing duplicates, 87 assessments remained for consideration. Applying exclusion criteria resulted in 15 recommended assessments.

Table 2 provides an overview of the 15 pain instruments that were recommended for chronic pain assessment in children with CP. Using the NINDS CDE language for recommended applications, 8 out of the 15 identified CP chronic pain CDEs were classified as ‘Supplemental’ and the remaining seven pain tools were categorized as ‘Exploratory’ because limited study had been published in the target group. None of the pain tools were classified as ‘Core’ or ‘Supplemental – Highly Recommended’.

TABLE 2.

CP CDE pain tools

| Tool | Purpose | Psychometric properties | Pain categories | ICF domain(s) | CP CDE classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire30,31 | This is a 61-item multidimensional self-report measure that assesses adolescent functioning across seven different domains affected by pain. Nature of the questions may make this of greatest utility for children with CP who are ambulatory. | Convergent validity: moderate to high. Comparative validity: significant. Temporal reliability: moderate to high. Internal consistency: good to excellent. |

Interference | Activity and participation | Supplemental |

| Body Diagram32,33 | The Body Diagram is a discriminative tool, validated with children with chronic pain conditions, which is used to assess the location, distribution, and intensity of acute and chronic pain. Children with greater impairment in gross/fine motor function or communication impairments affecting ability to verbally indicate pain locations may decrease the accuracy of the assessment. | Content and concurrent validity: good. Alternate form of reliability: good. Scoring reliability: excellent. |

Location and intensity | Body structure, body functions | Exploratory |

| Brief Pain Inventory Long Form34–37 Brief Pain Inventory Short Form34–37 |

The Brief Pain Inventory rapidly assesses the severity of pain and its impact on functioning and. The Inventory contains additional descriptive items that may be clinically useful (e.g. items that expand the possible descriptors of pain, such as burning, tingling, etc.) Certain items in it, such as questions on interference with functions, may be confounded by motor and cognitive impairments. | Internal consistency: good to excellent. Test–retest reliability: acceptable to excellent. |

Intensity, interference, location, and quality | Body structures, body functions, activity, and participation | Supplemental |

| Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI)21,38–40 | The CALI is a subjective, validated, and reliable measure of functional impairment due to recurrent chronic pain in children and adolescents with similar psychometric properties for the original, CALI-21, and CALI-9 but may not be applicable for use in children with greater motor impairments, including children with CP classified in GMFCS levels IV and V. | Validity: good. Internal consistency: good to excellent. Test–retest reliability: moderate to low. Cross informant reliability: high. |

Interference | Activity and participation | Exploratory |

| Child Self-Efficacy Scale - Child41,42 | This is a self-report or parent-report tool that assesses how ‘sure’ a child is about performing various activities while in pain. For children with CP, discerning impact of pain from impact of physical impairment on self-efficacy in functioning may be more difficult. | Validity: good. Internal consistency: good to excellent. Parent and child report of child’s increased self-efficacy when functioning normally while in pain significantly correlate. |

Self-efficacy and interference | Activity and participation | Exploratory |

| Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale18,43–49 | This is a tool used to assess pain for infants and young children or individuals that are unable to self-report their level of pain.a | Validity and reliability: varied depending on study. Inter rater reliability: low to moderate. Concurrent validity: good. |

Behavior | Body structure, body functions, and activities | Exploratory |

| Faces Pain Scale - Revised10,50–53 | This is a self-report measure of children’s pain intensity adapted from the Faces Pain Scale that has six faces, in contrast to the seven of the Faces Pain Scale, which better aligns with the 10-point Likert Scale. | Construct validity: good to excellent in numerous studies in acute pain. Reliability: at least adequate in numerous studies assessing acute pain. Responsiveness: able to detect change in pain with painful procedure or administration of analgesia. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness less clear in children <7 years old. Used for measuring chronic pain in children with CP, but not validated in this population. |

Intensity | Body structures | Supplemental |

| Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist - Revised54–57 | This is a tool designed for parents or caregivers to assess pain during daily life for young children and adolescents who are unable to speak because of cognitive (mental/intellectual) impairments or disabilities. | Internal consistency/reliability: excellent. Test–retest reliability: good to excellent. Concurrent validity: good. Highly sensitive and specific for detecting presence or absence of pain. |

Behavior | Body functions, body structures, activity, and participation | Supplemental |

| Numeric Pain Rating Scale58–64 | This is a segmented numeric version of the Visual Analog Scale in which the respondent selects a whole number (0–10 integers) that best reflects the intensity of pain. | Test–retest reliability: excellent. Construct validity: high. Convergent validity: moderate to high. |

Intensity | Body functions | Supplemental |

| Pain Interference Index65,66 | This measure is a 6-item self-report questionnaire that assesses pain interference using the previous 2 weeks as a recall period. Certain items in it, such as questions on physical activities, may be confounded by motor impairments. | Internal consistency: excellent. Concurrent validity: moderate to high. Construct validity: good. |

Interference | Activity and participation | Supplemental |

| Pediatric Pain Profile67 | This is a 20-item behavior rating scale designed to assess pain in children with severe physical and learning impairments. | Internal consistency: good to excellent. Interrater reliability: good to excellent. High specificity and sensitivity to significant pain. Familiarity with the child did not impact scores. |

Behavior | Body structures, body functions, activity, and participation | Supplemental |

| Pediatric Pain Questionnaire21,68–70 | This assesses pain intensity and location along with the sensory, affective, and evaluative qualities of pain in children and adolescents. The modified version of the Pediatric Pain Questionnaire for use with children with CP is not validated for children in GMFCS levels IV or V. | Convergent validity; adequate. Reliability: moderate (6-month period between testing). Parent-child ratings did not differ significantly. Early validation in children with CP GMFCS levels I–III only, with modifications for children in GMFCS IV or V that has not been validated. Length of questionnaire may impede clinical utility. |

Intensity, quality, and location | Body structures, body functions | Exploratory |

| PROMIS Pain Behavior Short Forms71,72 | The PROMIS Pediatric and Parent Proxy Short Forms are 8-item self-reported measures to rate behaviors of individuals experiencing pain. As half of the measures in this tool relate to some physical function and/or communication ability, physical impairment and/or ability to verbally communicate may impact response. | Internal consistency: excellent. Convergent validity: excellent. Not used in CP population. |

Behavior | Body functions | Exploratory |

| PROMIS Pain Interference Short Forms72–74 | The PROMIS Pain Interference Short Form measures the self-reported consequences of pain on relevant aspects of one’s life, including engagement with social, cognitive, emotional, physical, and recreational activities. In use in children with CP, physical function items have been excluded, although it is not clear how this impacts the overall psychometric properties of this measure. | Reliability: excellent. Construct validity: good to excellent. |

Interference | Activity and participation | Supplemental |

| Visual Analog Scale11,13,18,75,76 | This is a measure for acute and chronic pain that provides a graphic representation of pain intensity by marking a point along a 10cm line. Used in several studies to assess pain management in children with CP. | Reliability in measuring acute pain well-established. Reliability for measuring chronic pain not well-established; however, it is recognized and used in individuals with chronic pain, including children with CP. | Intensity | Body functions | Exploratory |

Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability recommended as parental proxy report for chronic pain assessment of preschool children with CP.18

Abbreviations: CALI, Child Activity Limitations Interview; CDE, common data element; CP, cerebral palsy; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; PROMIS, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Table 2 provides a framework for selecting tools to assess chronic pain in children and young people with CP. The CP CDE pain tools were further sorted by pain categories and complemented by ICF representation to facilitate the practical application of the recommended valid and reliable tools. For example, to assess pain intensity, clinicians and researchers can select from the following tools: Body Diagram, Brief Pain Inventory Long and Short Forms, Faces Pain Scale - Revised, Numeric Pain Rating Scale, Pediatric Pain Questionnaire, and the Visual Analog Scale. The exact tool chosen for measuring chronic pain intensity in children and young people with CP would depend on multiple factors. For instance, the Brief Pain Inventory, Faces Pain Scale - Revised, and Numeric Pain Rating Scale are frequently used clinically to assess chronic pain as they are easy and quick to administer to children with all levels of mobility and culturally appropriate for use in international studies (Table 2).

For assessment of pain interference on activity and participation in children and young people with CP, the Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire, Brief Pain Inventory Long and Short Forms, Child Activity Limitations Interview, Child Self-Efficacy Scale - Child, Pain Interference Index, and the PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale are recommended options. Recommended options to assess the impact of pain on behavior in children and young people with CP include the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale, the Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist - Revised, the PROMIS Pain Behavior Short Forms, and the Pediatric Pain Profile.

While no single pain tool addressed the impact of chronic pain in children and young people with CP using an ICF perspective, a combination of tools could be used. For a detailed description of each NINDS CP CDE pain tool, details on psychometric properties, and use in other NINDS disease groups, please link to each Notice of Copyright found in Table 2, the NINDS CDE website, or Appendix S6.

The recommended NINDS CP CDE pain tools incorporate a diverse set of measures to assess the impact of chronic pain compared with other condition-specific CDEs. Of the 15 measures, the Brief Pain Inventory – Short Form tool is included in most of the condition-specific CDEs assessing chronic pain including Chiari I malformation, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy, neurorehabilitation, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, and Spinal Cord Injury - Pediatrics. The Spinal Cord Injury - Pediatrics recommends the Faces Pain Scale - Revised along with the PROMIS Pain Behavior and Pain Interference Short Forms found in the recommendations for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Finally, the Spinal Cord Injury - Pediatrics pain recommendations include the Child Activity Limitations Interview.

Examples of other pain tools in condition-specific NINDS CDEs excluded from further consideration and the reason(s) for exclusion are given in Appendix S7.

Table 3 shows the CP CDE pain tools categorized by age-groups, self-report versus proxy, and format of administration. This information can guide clinicians and researchers to identify the best measure(s) for their study or clinical setting. These identified chronic pain measures are directed at school-aged children and adolescents who can self-report pain.

TABLE 3.

Age, report type, and format of pain tools

| Tool | Age | Report type | Format | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Preschool | School-aged | Adolescent | Self-report | Parent-report | Form | Interview | Observation | |

|

| ||||||||

| Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Body Diagram | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Brief Pain Inventory Long and Short Forms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Child Activity Limitations Interview | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Child Self-Efficacy Scale - Child | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Faces Pain Scale - Revised | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist - Revised | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Numeric Pain Rating Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pain Interference Index | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Pediatric Pain Profile | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pediatric Pain Questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| PROMIS Pain Behavior Short Forms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| PROMIS Pain Interference Short Forms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Visual Analog Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Infants, toddlers, and non-verbal children with CP present a unique challenge in assessing pain. For studies targeting non-verbal children or children with communication challenges, recommended pain tools include proxy/caregiver report versions of the Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire, Child Activity Limitations Interview, Child Self-Efficacy Scale - Child, Pediatric Pain Profile, PROMIS Pain Behavior Short Forms, and PROMIS Pain Interference Short Forms.

Behavioral pain assessment tools such as the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability Scale, the Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist - Revised, and the Pediatric Pain Profile are appropriate for preschool-age children as well as children and young people unable to self-report pain.

Content gap recommended CP pain CDE tools

Few areas of functioning are underrepresented in the current recommended NINDS CP CDE pain tools; for example, tools that capture the impact of chronic pain on sleep pattern, coping responses to chronic pain, attitudes towards pain that are based on beliefs, or cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Although the proposed set does not include tools fully dedicated to these areas, a few of the tools partly cover some of them: for example, the Child Self-Efficacy Scale - Child (coping strategies) and the Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (impact of pain on sleep). Future revisions will consider expanding the content of the set to address these gaps.

DISCUSSION

This paper describes the first condition-specific chronic pain CDE measures for a pediatric population. The new CP CDE chronic pain tools address the evaluation of chronic pain and its functional impact in everyday activities in children and young people with CP, contributing to filling a gap in chronic pain assessment and evaluation in this population. The proposed chronic pain tools harmonize the assessment of chronic pain in these children and young people.

The 15 recommended chronic pain assessments facilitate the evaluation of the location, intensity, quality, and behaviors of pain, as well as the interference of chronic pain in day-to-day activities in children and young people with CP. Most tools may be used in school-aged children, allowing them to self-report their experiences of living with chronic pain. Families, professionals, and researchers should consider this information to guide goal-setting and intervention strategies.

When comparing the content of the 15 recommended CP CDE pain tools with other initiatives assessing pain in CP, for example in terms of coverage of ICF components,13 the CP CDE pain set ensures systematic evaluation of the impact of chronic pain in activities and participation. In addition, the proposed CP CDE pain tools cover the 12 domains suggested by Harvey et al.17 as core areas guiding pain assessment in CP: pain location, pain frequency, pain intensity, changeable factors, impact on emotional well-being, impact on participation, pain communication, influence on quality of life, physical impacts, sleep, pain duration, and pain expression. These domains reflect the complexity of pain in a heterogeneous population such as those with CP, where communication impairments, intellectual disabilities, and medical comorbidities are common and impact significantly on the ability to self-report.

The importance of CDEs for research studies and meta-analyses has been clearly stated by the National Institutes of Health and research community (Sheehan et al.2 and others), and they can also serve an important purpose in clinical practice. In addition to accelerating the pace of discovery for implementation into best practice guidelines, the CDEs can serve as a resource for practicing clinicians and trainees as a repository of validated measurement tools for evaluating prognosis or documenting patient progress over time. CDEs can facilitate communication between providers, which has been cited as a significant barrier to chronic pain management for children and adolescents with CP.53 Furthermore, the set of CDE tools can be the basis of quality-improvement projects to standardize documentation and process where alignment between healthcare providers can harmonize with the scientific literature.

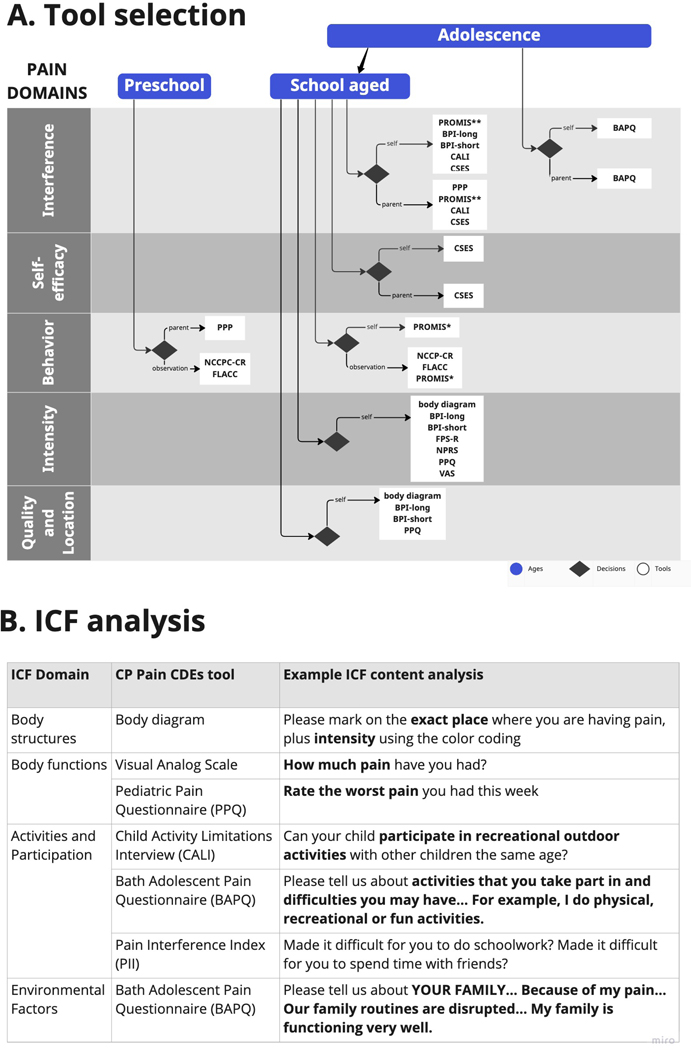

Clinicians or researchers can use Figure 1a as a guide to select appropriate tools for their intended study or clinical settings. Starting with the age category of the child(ren), where measurement is needed, they can then move to the decision-point diamond in the pain domain of greatest interest. There, the chart shows options for administration/report and lists available items. The larger list can be quickly narrowed to only the items most appropriate for a given situation. The chart demonstrates the relative paucity of tools for preschool-aged children, and that many of the instruments focus on the intensity domain. Importantly, the functional impact of chronic pain in everyday activities can be explored with tools categorized under pain interference. Figure 1b provides examples of the ICF content analysis that may be done for specific items of the tests (as summarized in Table 2), showing how items represent different ICF domains. Examples of the functional impact of chronic pain, using the ICF language, are shown in the component activities and participation. These summary tools can, like the CDEs in general, streamline the process of identifying appropriate measures in situations when it is important to assess chronic pain.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Options that researchers/clinicians may use to select appropriate cerebral palsy pain tools for research study or in the clinical setting. The chart provides options to select tools by ages (preschool, school age, adolescence) and pain domains (quality and location, intensity, behavior, self-efficacy, and interference), leading to decision ‘diamonds’ indicating pain tools to use. (b) Examples of International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Heal (ICF) content analysis by ICF domain, for specific items of the pain tools, allowing the researcher/clinician to streamline the process of identifying appropriate measures when it is important to assess chronic pain.

This study has limitations. By limiting the inclusion criteria to pain tools published in English, it excluded any pain tools published exclusively in another language. Future revisions might include broadening the inclusion criteria to pain tools published in non-English language. Another limitation is that studies assessing pain in children with CP use disease/disorder diagnostic pain tools; as such, many of the pain tools were not specific for children with CP or differentiated between types or motor functional levels of CP. Because we took a stepwise approach to facilitate identification and critical evaluation of tools within the biopsychosocial model of assessing chronic pain and its impact on function in children and young people with CP, some biopsychosocial factors were underrepresented, including those focused on coping. These are areas to be evaluated.

Similar efforts were leveraged to move towards implementation of these tools into research and clinical care.19,21 Given the high prevalence of chronic pain in the population of children with CP,19 this set of CDEs provides the framework to begin collecting data immediately to supplement primary outcome measures of studies and to understand interactions between pain and response to interventions. Furthermore, the proposed CP CDE pain tools provide the data structure for studies for which chronic pain is a primary outcome measure.

Several content gaps were identified after comparison of chronic pain tools for children and young people with CP. There is a need for validated tools of chronic pain across the ICF framework for use with children and young people who are non-verbal or who have intellectual disabilities. Similar findings have recently been reported by Smith et al.,77 showing a scarce number of tools to assess chronic pain interference in individuals with CP who are unable to self-report owing to communication, motor, or cognitive limitations.

For tools that assess physical function and activity participation in relation to chronic pain, inclusion of assessments that measure activities across a spectrum of physical abilities is needed. There is also a need for assessments of types of chronic pain (e.g. neuropathic, visceral, central, and musculoskeletal). Finally, there is a need for validated measures that address change in chronic pain with interventions in children and adolescents with CP.

Although several tools exist, there are gaps in characterizing and assessing chronic pain in children and young people with CP. Tools that characterize and assess chronic pain across ICF domains, ages, and functional abilities in children and young people with CP must continue to be developed, validated, and utilized. However, it is critical that work moves beyond assessing chronic pain intensity. Tools validated for and sensitive to assessing changes in chronic pain across ICF domains in children and young people with CP are imperative for identification of promising interventions for improving chronic pain, initiation of clinical trials to provide the rigorous research needed to assess these interventions, and implementation of these interventions to reduce the burden of chronic pain in this population. Lastly, we acknowledge that the current proposed set underrepresents the functioning areas of impact of chronic pain on sleep pattern, coping strategies to stress and chronic pain, and attitudes towards pain that are based on beliefs, or cultural and ethnic backgrounds. A stepwise approach to critically evaluate and identify tools targeting these biopsychosocial factors and their impact on chronic pain in children and young people with CP is recommended.

CONCLUSION

This initiative addressed a content gap identified in the NINDS CP CDEs version 1.0. With the novel set of pain tools recommended, the CP CDE pain tools provide a framework for consistently measuring chronic pain in research and clinical studies involving children and young people with CP. As research evolves, updates and revisions to the CP CDEs are expected and welcomed to help improve the rigor of these data collection standards. Beyond research applications, this comprehensive set of CP CDE pain tools also serves as a clinical resource for teaching, standardizing the selection of pain measures and pain assessments, adopting a biopsychosocial approach to pain evaluation, harmonizing data collection and reporting, and guiding quality-improvement projects to further develop the care of children and young people with CP and chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1: Example Search Strategy – PubMed.

Appendix S3: CP CDE chronic pain recommendations timeline.

Appendix S4: CP pain tool CDE rating system.

Appendix S5: PROMIS pain domains.

Appendix S7: Excluded CP CDEs used in other NINDS CDE condition-specific groups.

Appendix S6: Fifteen pain tools details.

Figure S1: Pain assessment identification screening and inclusion.

Appendix S2: PRISMA checklist.

What this paper adds.

The proposed chronic pain tools harmonize the assessment of chronic pain in children and young people with cerebral palsy (CP).

The new CP pain common data elements address the functional impact of chronic pain in everyday activities in children and young people with CP.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Development of the NINDS CP CDEs was made possible thanks to the investment of time and effort of CP Oversight Committee and CP Working Group members and the members of the NINDS CDE Project team participating from 2015 to the present.

Funding

National Institutes of Health contracts HHSN271201700064C and 75N95022C00041.

Abbreviations:

- CDE

common data element

- ICF

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

- NINDS

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROMIS

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

The following additional material may be found online:

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have stated that they had no interests that might be perceived as posing a conflict or bias.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schiariti V, Fowler E, Brandenburg JE, Levey E, McIntyre S, Sukal-Moulton T, et al. A common data language for clinical research studies: the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine Cerebral Palsy Common Data Elements Version 1.0 recommendations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018; 60: 976–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheehan J, Hirschfeld S, Foster E, Ghitza U, Goetz K, Karpinski J, et al. Improving the value of clinical research through the use of Common Data Elements (CDEs). Clin Trials. 2016; 13: 671–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Library of Medicine. Common Data Elements (CDEs) Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2022. Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/oet/ed/cde/tutorial/03-100.html#:~:text=A%20common%20data%20element%20(CDE,to%20ensure%20consistent%20data%20collection. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiariti V. Standardized and individualized care: do they complement or oppose each other? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018; 60: 1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rochani HD, Modlesky CM, Li L, Weissman B, Vova J, Colquitt G. Association of Chronic Pain With Participation in Motor Skill Activities in Children With Cerebral Palsy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4: e2115970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carozza L, Anderson-Mackay E, Blackmore AM, Kirkman HA, Ou J, Smith N, et al. Chronic Pain in Young People With Cerebral Palsy: Activity Limitations and Coping Strategies. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2022; 34: 489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penner M, Xie WY, Binepal N, Switzer L, Fehlings D. Characteristics of pain in children and youth with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2013; 132: e407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostojic K, Paget S, Kyriagis M, Morrow A. Acute and Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents With Cerebral Palsy: Prevalence, Interference, and Management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020; 10 1: 213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkinson KN, Dickinson HO, Arnaud C, Lyons A, Colver A. Pain in young people aged 13 to 17 years with cerebral palsy: cross-sectional, multicentre European study. Arch Dis Child. 2013; 98: 434–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinnon-CT, Morgan PE, Antolovich GC, Clancy CH, Fahey MC, Harvey AR. Pain in children with dyskinetic and mixed dyskinetic/spastic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020; 62: 1294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostojic K, Paget SP, Morrow AM. Management of pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019; 61: 315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinch J, Eccleston C. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: assessment and management. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009; 48: 466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiariti V, Oberlander TF. Evaluating pain in cerebral palsy: comparing assessment tools using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Disabil Rehabil. 2019. ;41: 2622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016; 9: 457–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forgeron PA, King S, Stinson JN, McGrath PJ, MacDonald AJ, Chambers CT. Social functioning and peer relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A systematic review. Pain Res Manag. 2010;15: 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKinnon CT, White JH, Morgan PE, Antolovich GC, Clancy CH, Fahey MC, et al. The lived experience of chronic pain and dyskinesia in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey AR, McKinnon CT, Smith N, Ostojic K, Paget SP, Smith S, et al. Establishing consensus for the assessment of chronic pain in children and young people with cerebral palsy: a Delphi study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022; 44: 7161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letzkus L, Fehlings D, Ayala L, Byrne R, Gehred A, Maitre NL, et al. A Systematic Review of Assessments and Interventions for Chronic Pain in Young Children With or at High Risk for Cerebral Palsy. J Child Neurol. 2021; 36: 697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orava T, Provvidenza C, Townley A, Kingsnorth S. Screening and assessment of chronic pain among children with cerebral palsy: a process evaluation of a pain toolbox. Disabil Rehabil. 2019; 41: 2695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westbom L, Rimstedt A, Nordmark E. Assessments of pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a retrospective population-based registry study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017; 59: 858–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kingsnorth S, Orava T, Provvidenza C, Adler E, Ami N, Gresley-Jones T, et al. Chronic Pain Assessment Tools for Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2015; 136: e947–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NINDS Common Data Elements Website: National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; 2022. [updated 31 August 2002. Available from: https://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health. The Helping to End Addiction Long-term Initiative 2019. [Available from: https://heal.nih.gov/.

- 25.Barke A, Korwisi B, Jakob R, Konstanjsek N, Rief W, Treede RD. Classification of chronic pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11): results of the 2017 international World Health Organization field testing. Pain. 2022; 163: e310–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen LL, Lemanek K, Blount RL, Dahlquist LM, Lim CS, Palermo TM, et al. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric pain. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2008; 33: 939–55; discussion 56–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox LA, Hwang S, Haines J, Ramos EM, McCarty CA, Marazita ML, et al. Using the PhenX Toolkit to Select Standard Measurement Protocols for Your Research Study. Curr Protoc. 2021; 1: e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok RK, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 174: 253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revicki D, Cook K. PROMIS Pain-Related Measures: An Overview. Pract Pain Manag. 2015;15(3). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eccleston C, Jordan A, McCracken LM, Sleed M, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ): development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. Pain. 2005; 118: 263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eccleston C, McCracken LM, Jordan A, Sleed M. Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of the parent report version of the Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ-P): A multidimensional parent report instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. Pain. 2007; 131: 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Baeyer CL, Lin V, Seidman LC, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. Pain charts (body maps or manikins) in assessment of the location of pediatric pain. Pain Manag. 2011; 1(1): 61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savedra MC, Tesler MD, Holzemer WL, Wilkie DJ, Ward JA. Pain location: validity and reliability of body outline markings by hospitalized children and adolescents. Res Nurs Health. 1989; 12: 307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleeland CS. The Brief Pain Inventory User Guide Houston, TX: The University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; 1991. Available from: https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Departments-and-Divisions/Symptom-Research/BPI_UserGuide.pdf.

- 35.Cleeland CS. The Brief Pain Inventory Houston, TX: The Univeristy of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; 2009. Available from: https://www.mdanderson.org/research/departments-labs-institutes/departments-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/brief-pain-inventory.html.

- 36.Atkinson TM, Mendoza TR, Sit L, Passik S, Scher HI, Cleeland C, et al. The Brief Pain Inventory and its “pain at its worst in the last 24 hours” item: clinical trial endpoint considerations. Pain Med. 2010; 1: 337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barney CC, Stibb SM, Merbler AM, Summers RLS, Deshpande S, Krach LE, et al. Psychometric properties of the brief pain inventory modified for proxy report of pain interference in children with cerebral palsy with and without cognitive impairment. Pain Rep. 2018; 3: e666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holley AL, Zhou C, Wilson AC, Hainsworth K, Palermo TM. The CALI-9: A brief measure for assessing activity limitations in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2018; 159: 48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palermo TM, Lewandowski AS, Long AC, Burant CJ. Validation of a self-report questionnaire version of the Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI): The CALI-21. Pain. 2008; 139: 644–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palermo TM, Witherspoon D, Valenzuela D, Drotar DD. Development and validation of the Child Activity Limitations Interview: a measure of pain-related functional impairment in school-age children and adolescents. Pain. 2004; 109: 461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bursch B, Tsao JC, Meldrum M, Zeltzer LK. Preliminary validation of a self-efficacy scale for child functioning despite chronic pain (child and parent versions). Pain. 2006; 125: 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahlschmidt L, Hübner-Möhler B, Dogan M, Wager J. Pain Self-Efficacy Measures for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019; 44: 530–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Burke C, Merkel S, Tait AR. The revised FLACC observational pain tool: improved reliability and validity for pain assessment in children with cognitive impairment. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006; 16: 258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S. The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs. 1997; 23: 293–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crellin DJ, Harrison D, Santamaria N, Babl FE. Systematic review of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability scale for assessing pain in infants and children: is it reliable, valid, and feasible for use? Pain. 2015; 156: 2132–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fox MA, Ayyangar R, Parten R, Haapala HJ, Schilling SG, Kalpakjian CZ. Self-report of pain in young people and adults with spastic cerebral palsy: interrater reliability of the revised Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability (r-FLACC) scale ratings. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019; 61: 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahu MA, Grap MJ, Ferguson P, Joseph P, Sherman S, Elswick RK Jr. Validity and sensitivity of 6 pain scales in critically ill, intubated adults. Am J Crit Care. 2015; 24: 514–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voepel-Lewis T, Merkel S, Tait AR, Trzcinka A, Malviya S. The reliability and validity of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability observational tool as a measure of pain in children with cognitive impairment. Anesth Analg. 2002; 95: 1224–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voepel-Lewis T, Zanotti J, Dammeyer JA, Merkel S. Reliability and validity of the face, legs, activity, cry, consolability behavioral tool in assessing acute pain in critically ill patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010; 19: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bieri D, Reeve RA, Champion DG, Addicoat L, Ziegler JB. The Faces Pain Scale for the self-assessment of the severity of pain experienced by children: development, initial validation, and preliminary investigation for ratio scale properties. Pain. 1990; 41: 139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomlinson D, von Baeyer CL, Stinson JN, Sung L. A systematic review of faces scales for the self-report of pain intensity in children. Pediatrics. 2010; 126: e1168–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harvey AR, McKinnon CT, Smith N, Ostojic K, Paget SP, Smith S, et al. Establishing consensus for the assessment of chronic pain in children and young people with cerebral palsy: a Delphi study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022; 44: 7161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McKinnon C, White J, Morgan P, Harvey A, Clancy C, Fahey M, et al. Clinician Perspectives of Chronic Pain Management in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy and Dyskinesia. Dyskinesia. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2021; 41: 244–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breau LM, Camfield C, McGrath PJ, Rosmus C, Finley GA. Measuring pain accurately in children with cognitive impairments: refinement of a caregiver scale. Journal Pediatr. 2001; 138: 721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breau LM, McGrath PJ, Camfield C, Rosmus C, Finley GA. Preliminary validation of an observational pain checklist for persons with cognitive impairments and inability to communicate verbally. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000; 42: 609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breau LM, McGrath PJ, Camfield CS, Finley GA. Psychometric properties of the non-communicating children’s pain checklist-revised. Pain. 2002; 99: 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McGrath PJ, Rosmus C, Canfield C, Campbell MA, Hennigar A. Behaviours caregivers use to determine pain in non-verbal, cognitively impaired individuals. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998; 40: 340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castarlenas E, Jensen MP, von Baeyer CL, Miró J. Psychometric Properties of the Numerical Rating Scale to Assess Self-Reported Pain Intensity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Clin J Pain. 2017; 33: 376–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castarlenas E, Miró J, Sánchez-Rodríguez E. Is the verbal numerical rating scale a valid tool for assessing pain intensity in children below 8 years of age? J Pain. 2013; 14: 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miró J, Castarlenas E, de la Vega R, Roy R, Solé E, Tomé-Pires C, et al. Psychological Neuromodulatory Treatments for Young People with Chronic Pain. Children (Basel). 2016; 3: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miró J, Castarlenas E, Huguet A. Evidence for the use of a numerical rating scale to assess the intensity of pediatric pain. Eur J Pain. 2009; 13: 1089–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Connelly M The verbal numeric rating scale in the pediatric emergency department: what do the numbers really mean? Pain. 2010; 149: 167–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jensen MP, McFarland CA. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurement in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1993; 55: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.von Baeyer CL. Numerical rating scale for self-report of pain intensity in children and adolescents: recent progress and further questions. Eur J Pain. 2009; 13: 1005–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holmström L, Kemani MK, Kanstrup M, Wicksell RK. Evaluating the Statistical Properties of the Pain Interference Index in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Pain. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015; 36: 450–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin S, Nelson Schmitt S, Wolters PL, Abel B, Toledo-Tamula MA, Baldwin A, et al. Development and validation of the English Pain Interference Index and Pain Interference Index-Parent report. Pain Med. 2015; 16: 367–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hunt A, Goldman A, Seers K, Crichton N, Mastroyannopoulou K, Moffat V, et al. Clinical validation of the paediatric pain profile. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004; 46: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Varni JW, Thompson KL, Hanson V. The Varni/Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire. I. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 1987; 28: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gragg RA, Rapoff MA, Danovsky MB, Lindsley CB, Varni JW, Waldron SA, et al. Assessing chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with rheumatic disease: further validation of the pediatric pain questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996; 21: 237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Houlihan CM, Hanson A, Quinlan N, Puryear C, Stevenson RD. Intensity, perception, and descriptive characteristics of chronic pain in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2008; 1: 145–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cook KF, Keefe F, Jensen MP, Roddey TS, Callahan LF, Revicki D, et al. Development and validation of a new self-report measure of pain behaviors. Pain. 2013; 154: 2867–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cunningham NR, Kashikar-Zuck S, Mara C, Goldschneider KR, Revicki DA, Dampier C, et al. Development and validation of the self-reported PROMIS pediatric pain behavior item bank and short form scale. Pain. 2017; 158: 1323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, Chen WH, Choi S, Revicki D, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010; 150: 173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shearer HM, Côté P, Hogg-Johnson S, McKeever P, Fehlings DL. Identifying pain trajectories in children and youth with cerebral palsy: a pilot study. BMC Pediatr. 2021; 21: 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008; 9: 771–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stinson JN, Kavanagh T, Yamada J, Gill N, Stevens B. Systematic review of the psychometric properties, interpretability and feasibility of self-report pain intensity measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents. Pain. 2006;125: 143–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith MG, Farrar LC, Gibson RJ, Russo RN, Harvey AR. Chronic pain interference assessment tools for children and adults who are unable to self-report: A systematic review of psychometric properties. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023. Feb 5. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Example Search Strategy – PubMed.

Appendix S3: CP CDE chronic pain recommendations timeline.

Appendix S4: CP pain tool CDE rating system.

Appendix S5: PROMIS pain domains.

Appendix S7: Excluded CP CDEs used in other NINDS CDE condition-specific groups.

Appendix S6: Fifteen pain tools details.

Figure S1: Pain assessment identification screening and inclusion.

Appendix S2: PRISMA checklist.