Abstract

Objective:

Low employment rates among individuals with serious mental illness can be improved with engagement in the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment. A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT) enhanced employment among individuals with serious mental illness actively engaged in IPS for at least 90 days without obtaining employment. This study reports on an initial implementation evaluation of VR-JIT during the aforementioned RCT in a community mental health agency.

Methods:

A sequential, complementary mixed-methods design used qualitative data to gain greater depth of understanding of quantitative findings. Eleven IPS employment specialists trained to lead VR-JIT implementation completed VR-JIT acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility surveys. Forty-two participants randomized to IPS with VR-JIT completed acceptability and usability surveys after implementation. We then conducted five focus groups and thirteen semi-structured interviews with IPS staff and VR-JIT implementers and recipients, followed by an integrated analysis process.

Results:

Quantitative results suggest IPS employment specialists, on average, found VR-JIT to be highly acceptable, appropriate for integration with IPS, and feasible for delivery. VR-JIT recipients reported the intervention to be highly acceptable. Qualitative results added important context to quantitative findings, including advantages for IPS employment specialists as well as adaptations for delivering technology-based interventions to individuals with serious mental illness.

Conclusions:

Qualitative findings corroborate quantitative results, which were influenced by VR-JIT’s adaptability and perceived relative advantage. Implications include tailoring VR-JIT instruction and delivery to individuals with serious mental illness, and further evaluating approaches to optimize VR-JIT implementation within IPS.

Keywords: Employment, Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, Job Interviewing, Implementation Evaluation

Approxmiately 80% of individuals with serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) are unemployed in the United States (1, 2). Meanwile, long-term unemployment and disability contributes to prolonged poverty, housing instability and food insecurity for many of these individuals (3). The gold standard evidence-based vocational rehabilitation service to increase employment for this population is the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment (1).

Specifically, IPS improves the employment rate for individuals with serious mental illness to approximately 55% via rapid job placement through job development with ongoing supports (4, 5). Notably, technology-based adjunctive interventions have the potential to increase employment outcomes even higher (6,7). For example, computer-based cognitive remediation and computerized job interview training improved employment outcomes among individuals with serious mental illness who struggled to find employment through IPS (8, 9). Although there is potential for other technologies (e.g., smartphone app, Minds@Work) (10, 11) to improve employment, they have not yet been evaluated in IPS.

Meanwhile, initial implementation process outcomes can help elucidate whether effective adjunct interventions may be appropriate for IPS, acceptable by clients and staff, and feasible to deliver without reducing IPS fidelity. However, implementation typically occurs ≥10 years after an intervention is developed which leads to substantial delay before identifying effective implementation strategies (12).

To expedite this process, Curran and colleagues (12) formalized using hybrid effectiveness-implementation designs to concurrently evaluate an intervention’s effectiveness and implementation to speed translation. The Hybrid Type 1 (HT1) design primarily studies intervention effectiveness with a secondary evaluation of initial implementation process outcomes (12). An HT1 study was recently conducted to evaluate Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT; an internet-delivered job interview simulator with automated feedback (13, 14) as an effective adjunctive within IPS (9). See methods for a more detailed description of VR-JIT. The results showed that individuals with serious mental illness still unemployed after their first 90 days of IPS and randomized to IPS with VR-JIT had a higher proportion of employment (52% [N=13] vs. 19% [N=4] p<.05) and shorter time-to-employment (Hazard Ratio = 3.2, p<.05) by nine-months post-randomization compared to individuals with comparable unemployment after 90 days who were randomized to IPS-as-usual (9). Notably, this trial included a multi-level, multi-method process evaluation of facilitators and barriers to future VR-JIT implementation in high-fidelity IPS, and IPS staff and IPS client perceptions of VR-JIT appropriateness, acceptability, feasibility, and usability. Thus, this initial implementation process evaluation could serve as a template for future studies evaluating other technology-based interventions within IPS.

Methods

This initial process evaluation of VR-JIT implementation used a sequential, complementary mixed-method design where qualitative results provided depth of understanding (15) of quantitative implementation results. Specifically, we collected quantitative data from IPS staff (i.e., employment specialists, team leaders, program directors) on VR-JIT: 1) pre-implementation acceptability, 2) pre-implementation appropriateness, and 3) expected feasibility; and on acceptability and usability from VR-JIT recipients in the parent RCT. Next, qualitative post-implementation focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted with VR-JIT implementors, IPS employment specialists, IPS team leaders, and VR-JIT recipients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at [Masked] and [Masked]. A data safety and monitoring board supervised study procedures. All participants provided informed consent.

Trial Setting

The study was conducted at Thresholds, a non-profit community mental health agency in Chicago, IL, from June 2017 to October 2020. Thresholds provides comprehensive mental health services (http://thresholds.org).

Interventions

Individual Placement and Support.

IPS is a vocational support model based on eight principles: consumer choice (no exclusion criteria, only interest in work is required), a focus on competitive employment (e.g., non-sheltered work in settings employing people without disabilities for competitive wages), integration of mental health and employment services, attention to client preferences, benefits planning, rapid job search, job development, and individualized job supports (16). Independent ratings by the State of Illinois using the IPS Fidelity Scale (17) showed mean IPS fidelity ratings from 111–117, reflecting good-to-exemplary fidelity to IPS on all scales (range=0-125) during the course of the study.

Virtual Reality Job Interview Training.

VR-JIT is an interactive, computerized job interview simulator commercially licensed by SIMmersion LLC (www.simmersion.com) that uses a virtual hiring manager named “Molly Porter” who is governed by an algorithm that draws from > 1000 video clips of an actor. Trainees verbally respond to Molly’s questions from scripted choices while repeatedly practicing job interviews. Trainees receive automated feedback in real-time and via transcript review, performance review, and a score from 0 to 100 upon interview completion (18). Trainees apply for one of eight positions that informs the interview and an e-Learning curriculum provides interview preparation advice. Based on the job interview literature and content expert review (19, 20), VR-JIT highlights eight interview skills designed to convey an applicant’s positive attributes (e.g., being a hard worker, being easy to work with).

Delivery Model.

Employment specialists were initially trained to implement VR-JIT, but did not due to unforeseen implementation barriers. Instead, Thresholds’ internal research staff (called VR-JIT implementers) delivered VR-JIT at community agencies. See supplemental materials for staff training methods to implement VR-JIT with fidelity and the delivery structure of VR-JIT.

Participants

IPS staff participants included program directors, team leaders, and employment specialists who were trained to implement VR-JIT during the main RCT or had VR-JIT recipients on their caseload. RCT participants were actively engaged in IPS at the time of enrollment (i.e., at least 1 contact with employment specialist in past 30 days, were at least 18 years old, living with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depressive disorder (any type), or bipolar disorder (types I & II; with or without psychotic features), and were currently unemployed/underemployed and planning to interview for a job within the next four weeks. Remaining inclusion criteria are listed in Supplemenal Materials.

Quantitative Methods

Data Collection

Employment specialists (N=8), team leaders (N=3), and program directors (N=2) were invited to complete a paper survey after completing an orientation on how to teach RCT participants to use VR-JIT. Meanwhile, RCT participants completed a paper survey assessing VR-JIT acceptability (N=42) and usability (N=28, a subsample of the N=42).

Measures

Pre-Implementation Acceptability, Appropriateness, and Feasibility.

VR-JIT orientation acceptability, VR-JIT appropriateness, and the expected feasibility of delivering VR-JIT within IPS were assessed using items adapted from Proctor et al. (21) and Weiner et al. (22), and used in prior implementation evaluations of virtual interviewing in special education settings (23–25).

Orientation Acceptability.

This measure consisted of 7 items (e.g., “How satisfied are you with the training you received on VR-JIT?”) that were summed for a total score. Item responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1=Not at all satisfied to 5=Very satisfied; or 1=Not at all acceptable to 5=Very acceptable) (α=0.74).

Appropriateness.

This measure consisted of 5 items (e.g., “How well do you think VR-JIT fits with clients’ reasons and motivations for receiving IPS services?”) that were summed for a total score. Item responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1=Not at all effective to 5=Very effective; or 1=Not at all well to 5=Very well) (α=0.82).

Expected Feasibility.

This measure consisted of 9 items (e.g., “How confident are you that after training [participants], you will be able to support them as they implement VR-JIT?”) that were summed for a total score. Item responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1=Not at all prepared to 5=Very prepared; or 1=Not at all confident to 5=Very confident) (α=0.89).

Post-Implementation VR-JIT acceptability and usability.

VR-JIT recipients completed acceptability and usability surveys after their final VR-JIT session.

Acceptability.

The Training Experience Questionnaire (18) was used to evaluate VR-JIT acceptability. This survey included 5 items (e.g., “How helpful was this training in preparing you for a job interview?”) that were summed for a total score. Item responses were on a 7-point Likert scale (e.g., 1= Extremely unhelpful to 7=Extremely helpful) (α=0.73).

Usability.

Two items were adapted from the Systems Usability Scale (27) to assess VR-JIT usability (i.e., How comfortable are you using the VR-JIT training on your own? and How much do you need staff there to help you use VR-JIT?). The items were measured using a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 1=Not at all to 4=Very much). Individual item means are reported.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. Descriptive analyses (i.e., mean, standard deviation, range) were generated for the IPS staff-level and VR-JIT recipient-level initial implementation process outcomes.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative data were collected to assess the initial process evaluation of VR-JIT through focus groups, and later, through using purposive semi-structured interviews, with a data analysis phase in-between (See Supplemental Figure).

Data Collection

The IPS program director shared a study recruitment email with employment specialists and team leaders (who had clients on their caseload who used VR-JIT) to participate in the qualitative study. Three focus groups were held with employment specialists (N=12) and two with VR-JIT recipients (N=13). Thirteen semi-structured interviews were held with VR-JIT implementers (N=3), employment specialists (N=3), team leaders (N=3), and VR-JIT recipients (N=4), respectively. Focus groups and interviews were video-recorded. VR-JIT recipients were recruited by phone and interviewed by research staff (recorded using digital audio). See supplemental material for additional data collection methods.

Qualitative analysis

Interviews were transcribed by research assistants and analyzed using Dedoose software (27). Three research team members analyzed interview transcripts using line-by-line coding, assigning codes based on a priori and emerging themes (28). A priori themes included coding for content relevant to the experience of implementing VR-JIT, while emerging themes uncovered new information about using VR-JIT within IPS. Each coder worked with an unmarked transcript and coded for themes. Then the three research team members met to review codes and themes until categories were agreed upon. We organized theme categorizing using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Version 2.0) (29). CFIR 2.0 was selected due to its provision of evidence-based domains that help to frame the implementation needs of mental health interventions (e.g., outer setting and how aspects of the intervention itself influenced implementation at a specific site, with a particular population [29,30]).

Integration of Quantitative & Qualitative Analysis

Following a sequential, complementary mixed-methods approach (15), final qualitative results were compared alongside quantitative results to expand and improve depth of understanding. This process occurred by examining the qualitative themes and applying them to the quantitative implementation categories of acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility. Qualitative themes that did not fit the quantitative categories were included in the results as emerging data within CFIR 2.0 domains that enhanced our understanding of VR-JIT implementation in a community mental health agency.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 displays the sample characteristics of the study participants.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics of the study sample, by group

| Staff surveys (N=13) | Staff focus groups (N=11) | Staff interviews (N=9) | VR-JIT recipient surveys (N=42) | VR-JIT recipient focus groups (N=13) | VR-JIT recipient interviews N=4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Age (M±SD) | 34.8±7.8 | 33.5±9.9 | 33.1±8.6 | 47.5±13.1 | 50.7±13.2 | 51.8± 12.6 | ||||||

| Female biological sex | 10 | 77 | 7 | 64 | 6 | 67 | 21 | 50 | 7 | 54 | 4 | 100 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| African American/Black | 11 | 84 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 33 | 26 | 62 | 9 | 69 | 3 | 75 |

| Asian | 1 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 11 | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | -- | 0 |

| White | 1 | 8 | 4 | 36 | 5 | 56 | 11 | 26 | 3 | 23 | -- | 0 |

| Latinx | 0 | -- | 3 | 27 | -- | 0 | 4 | 10 | -- | 0 | -- | 0 |

| More than 1 race | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 25 |

| Highest level of education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school diploma/GED (%) | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 11 | 26 | 3 | 23 | 1 | 25 |

| High school diploma/GED | 1 | 8 | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 10 | 24 | 2 | 15 | -- | 0 |

| Some college | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 18 | 43 | 6 | 46 | 2 | 50 |

| Associate’s degree | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 1 | 2 | -- | 0 | -- | 0 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4 | 31 | 7 | 64 | 4 | 44 | -- | 0 | 1 | 8 | -- | 0 |

| Master’s degree | 8 | 61 | 4 | 36 | 5 | 56 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 25 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia spectrum | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 29 | 69 | 9 | 70 | 1 | 25 |

| Major depressive disorder | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 9 | 21 | 2 | 15 | 3 | 75 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 15 | 0 | -- |

| Substance use disorder (lifetime, secondary) | 0 | -- | -- | 0 | -- | 0 | 6 | 14 | 2 | 15 | 0 | -- |

Note. 42 of 54 VR-JIT recipients completed the acceptability survey. Six participants randomized to VR-JIT never used the tool. Twenty-eight VR-JIT recipients completed the usability items, which were added late to the study. VR-JIT recipients participated in the focus groups. Notably, six of 54 participants randomized to VR-JIT never used the tool and did not complete the acceptability and usability surveys and six of 48 participants who completed VR-JIT training did not complete the surveys.

One VR-JIT recipient survey completer did not report education level.

Quantitative Results

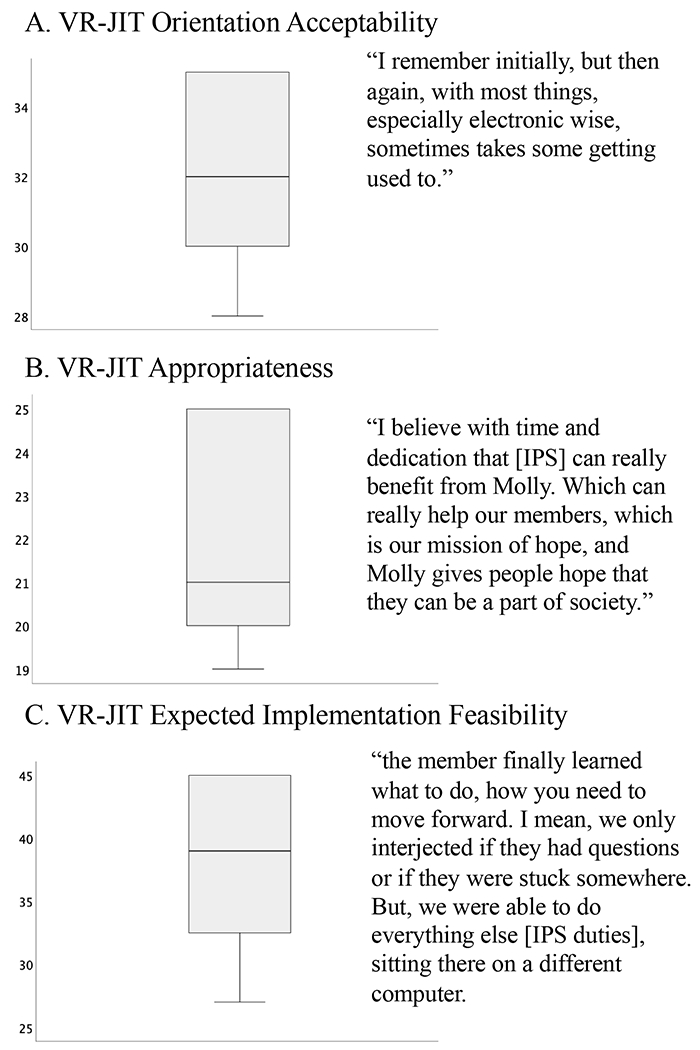

IPS Staff

IPS staff (n=13) reported that VR-JIT orientation was acceptable (M=32.09, SD=2.66, Max=35) and that VR-JIT was appropriate for interviewing practice within IPS (M=22.18, SD=2.44, Max=25). Also, IPS staff expected VR-JIT implementation to be feasible within IPS (M=38.09, SD=7.19, Max=45).

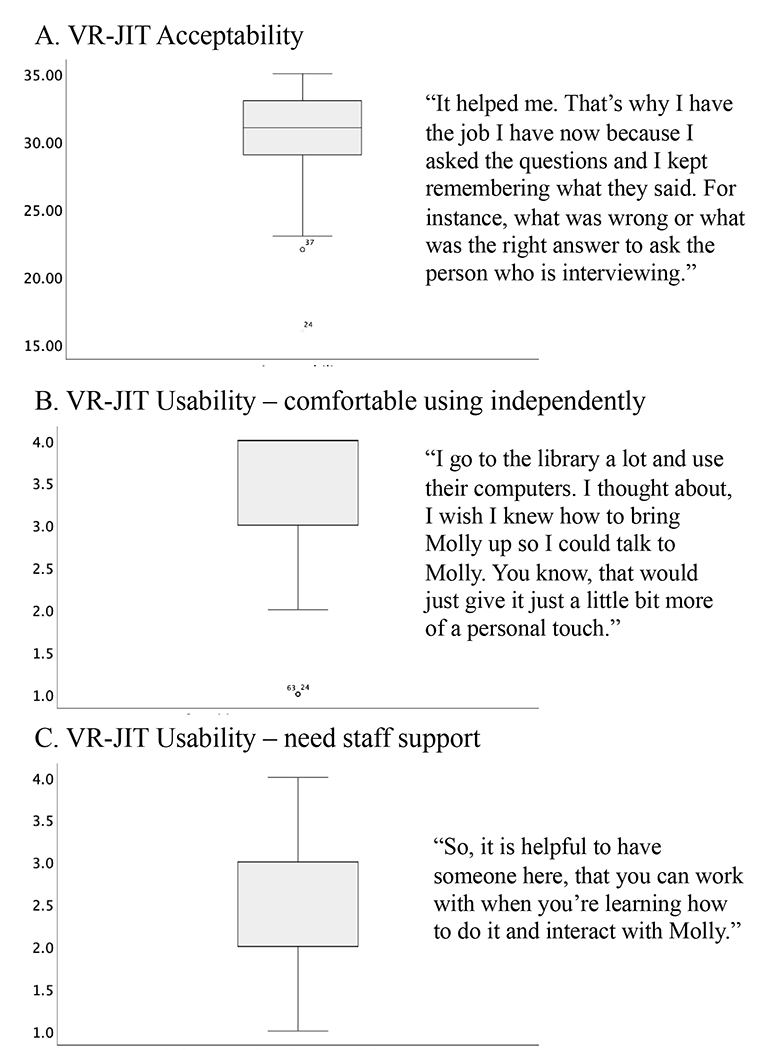

VR-JIT recipients

VR-JIT recipients (n=42) reported that VR-JIT was acceptable (M=30.38, SD=4.03, Max=35), and they were comfortable using VR-JIT independently (M=3.29, SD=1.01; Max=4), and did not need much staff support to use it (M=2.43, SD=1.00; Max=4).

Qualitative Results

Qualitative themes aligned with three broad CFIR 2.0 domains (Table 2): intervention characteristics (including relative advantages of the intervention and areas of adaptability), outer setting (including community characteristics), and individuals (including innovation recipients). See supplemental results and table for supporting quotes.

Table 2.

Qualitative implementation themes, by CFIR 2.0 domains

| CFIR 2.0 Domains | CFIR 2.0 Construct | Definition | Study Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | |||

| Relative Advantage | Stakeholders see the advantage of implementing the innovation compared to an alternative solution or keeping things the same. | The perceived relative advantage of VR-JIT centered on Molly Porter’s (i.e., the virtual hiring manager) ability to be “blunt” and direct in comparison to the supportive, strengths-based clinical approach of IPS staff. Staff at multiple implementation levels (e.g., VR-JIT implementer, employment specialist, team leader) discussed this directive component to practicing job interviews as beyond their typical scope of practice. |

|

| Relative Advantage | Stakeholders see the advantage of implementing the innovation compared to an alternative solution or keeping things the same. | Employment specialists discussed how VR-JIT recipients displayed an improved understanding about job search processes and stronger motivation to find employment after completing VR-JIT. Employment specialists shared that incorporating VR-JIT into IPS increased their efficiency. For example, IPS staff reported that VR-JIT enabled them to shift their attention to other important, yet time-consuming IPS tasks, like job development. |

|

| Adaptability | Stakeholders believe that the innovation can be sufficiently adapted, tailored, or re-invented to meet local needs. | VR-JIT implementers reported that knowing how to troubleshoot technology before delivering VR-JIT reduced the chances of participants disengaging from VR-JIT, particularly for participants who had limited computer skills. | |

| Adaptability | Stakeholders believe that the innovation can be sufficiently adapted, tailored, or re-invented to meet local needs. | VR-JIT implementers reported it was important to clearly explain the rationale behind using the intervention as a few VR-JIT recipients thought they were attending real job interviews. Thus, contextualizing VR-JIT more clearly may better prepare participants for staying engaged with the intervention. | |

| Adaptability | Stakeholders believe that the innovation can be sufficiently adapted, tailored, or re-invented to meet local needs. | Although IPS staff consistently discussed the need for more time to contextualize VR-JIT for clients, IPS staff suggested some clients became less engaged with VR-JIT because some sessions were too lengthy (>75 min). Thus, adapting both the duration of VR-JIT sessions, and the frequency of scheduled sessions to meet individual client needs may enhance its delivery within IPS. |

|

| Outer Setting | |||

| Community characteristics: built environment | Elements of the built environment create barriers/facilitators to implementation. | IPS staff described how transportation challenges impacted their client’s ability to attend weekly in-person VR-JIT sessions and suggested offering VR-JIT via remote services as a critical delivery adaptation | |

| Individuals | |||

| Innovation recipients | Receiving the innovation (directly or indirectly) | VR-JIT recipients with serious mental illnesses and long periods of disability faced some barriers staying engaged with VR-JIT sessions. IPS staff identified engagement barriers that they perceived as directly related to clients’ psychiatric symptoms or to ancillary issues, such as low-frustration tolerance. |

Intervention Characteristics

The first theme suggested VR-JIT provided a relative advantage to IPS (i.e., VR-JIT provides direct, unapologetic feedback that IPS staff don’t feel they can provide; employment specialists can shift attention to job development). The second theme centered on potential VR-JIT adaptations to enhance uptake within IPS (i.e., staff need working knowledge of any tech troubleshooting, translate ‘virtual’ aspect of VR-JIT during orientation, reduce duration and frequency of sessions).

Outer Setting

A single theme emerged on community characteristics that emphasized the use of public transportation as a barrier to attending multiple visits (Table 2).

Individuals

A single theme emphasized psychiatric symptoms and long periods of disability as potential barriers to VR-JIT engagement for individuals with serious mental illness receiving this innovative treatment (Table 2).

Mixed Methods Results

Our mixed methods approach enabled us to complement the quantitative findings by comparing them with their qualitative results (31). Thus, findings from IPS staff (acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility) were matched with quotes from the focus groups or interviews (Figure 1). For example, IPS staff quantitatively reported VR-JIT was highly appropriate (M=22.18, SD=2.44), while qualitatively they indicated “it [VR-JIT]’s been a great tool for members who have been enrolled [in IPS] and were able to use it.” Meanwhile, quantitative findings from VR-JIT recipients (acceptability, usability) were matched with quotes from the focus groups or interviews (Figure 2). For example, VR-JIT recipients reported VR-JIT was highly acceptable (M=30.38, SD=4.03), while qualitatively we heard “I didn’t have a challenge, I enjoyed the Molly Program. Made all of my appointments, of course I made them on time.” See supplemental results and table for supporting quotes.

Figure 1.

Joint display of IPS staff quantitative and qualitative data

Figure 2.

Joint display of VR-JIT recipient quantitative and qualitative data

Discussion

This initial implementation process evaluation of VR-JIT enhanced our understanding of how to implement and potentially adapt VR-JIT for IPS in an urban setting. Quantitative and mixed methods results suggested that IPS staff found VR-JIT to be acceptable, appropriate, and expected its implementation to be mostly feasible. Notably, a minority of employment specialists suggested it would take time to strategize how VR-JIT would fit into their workflow. Meanwhile, VR-JIT recipients reported VR-JIT to be highly acceptable and usable. Qualitative findings suggested that VR-JIT offered a relative advantage for IPS employment specialists regarding the addition of a focused and direct intervention for job interview training. Additionally, general technology skills were needed to be sure the program would run smoothly in a community setting. Finally, a minority of clients struggled to sustain VR-JIT engagement due to their psychiatric symptoms or challenges with focus and attention.

To overcome some technology-related barriers, IPS staff and clients suggest adapting VR-JIT delivery for clients with low computer literacy and training to troubleshoot technology challenges. IPS staff also recommended that VR-JIT orientation for clients should better explain that the intervention is a training activity. Further, results suggest that VR-JIT engagement and acceptability can be enhanced by aligning the duration and frequency of sessions with client preference. Finally, public transportation barriers were related to the need for multiple trips to the agency for VR-JIT sessions. Given that reliance on public transportation is the reality for many low-income adults residing in an urban setting, this finding raises the need to consider implementing VR-JIT via self-guided, fully remote, or hybrid (e.g., in-person VR-JIT orientation with remote support) delivery strategies. However, the feasibility of these implementation strategies is unknown and beyond the scope of this paper as we don’t yet know the scale to which clients have access to computing devices at home, in their neighborhood, or if they can check computing devicees out from their agency. However, this scalability is agency specific and speaks to needing agency-level VR-JIT implementation preparation planning, which has associated labor costs (32).

Overall, our findings suggest that technology-assisted interventions offer individuals with serious mental illness more opportunities to achieve their potential for recovery. Over the last decade, research suggests that integrating some technology-based interventions within the existing mental health service delivery system can be done practically, feasibly, and acceptably (33–35). Consistent with these prior studies, the initial implementation outcomes in this study suggest VR-JIT can add value and offer relative advantages to existing service, while considering some potential adaptations to overcome initial barriers. Thus, this study provides an innovation that focused on employment readiness as most existing research on technology-assisted interventions within mental health services focuses on symptoms and treatment adherence (33).

Implications for Practice

There were some suggested adaptations for future VR-JIT delivery. For instance, employment specialists could contextualize the importance of virtual interview practice prior to implementation, which may improve some issues with frustration or disengagement that were observed in a minority of the study participants. In addition, mental health agencies could consider training peer support specialists as VR-JIT implementers as a recent study found that peer support specialists perceived themselves as uniquely positioned to deliver VR-JIT given their lived experience (36).

Additional implications focus on how VR-JIT could enhance IPS. For instance, employment specialists reported that they appreciated the blunt responses from Molly Porter during the virtual interview. This approach gave their clients direct feedback from a third party in addition to their own supportive responses that were often socially desirable. Additionally, a previous qualitative study on IPS employment specialists and VR-JIT indicated clients perceived that working with VR-JIT improved their confidence in real-world job interviewing (37), consistent with prior RCT results (9). Notably, employment specialists perceived their clients’ improved confidence after VR-JIT as helping their IPS engagement and job search activities.

Limitations and Future Directions

The majority of VR-JIT sessions were delivered by trained research staff as opposed to employment specialists. Although employment specialists gave feedback on how VR-JIT assisted their clients and their own work, the results are limited in their ability to forecast implementation by employment specialists. For participants receiving VR-JIT, there is a potential risk to internal validity due to maturation effects. Specifically, VR-JIT recipients completed their acceptability and usability measures and initial focus groups prior to pausing enrollment due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Individual interviews occurred following the study termination due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Lastly, although all VR-JIT recipients were invited to participate in the focus groups, the interview participants were conveniently sampled from approximately 20% (N=8) of the IPS+VR-JIT group still engaged with IPS services during the pandemic and represented views of those with greater VR-JIT engagement.

Conclusion

This sequential, complementary mixed-method evaluation revealed initial implementation processes outcomes regarding VR-JIT delivery within IPS. Quantitative findings suggested that IPS staff and VR-JIT recipients found VR-JIT to be acceptable, usable, and feasible for improving job interviewing skills. Qualitative results from VR-JIT implementers, IPS staff and VR-JIT recipients provided additional depth and context to VR-JIT implementation such as advantages of offering VR-JIT within IPS to assist with obtaining employment more efficiently and recommendations for improving VR-JIT. Implications for future VR-JIT delivery within IPS include several adaptations such as additional training for implementers and alternative delivery strategies to help overcome initial implementation barriers.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

IPS staff reported that Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT) was appropriate and would be feasible to implement within the Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment

IPS employment specialists, team leaders, and program directors; and VR-JIT implementers and VR-JIT recipients reported the intervention to by highly acceptable

IPS employment specialists reported that VR-JIT helped facilitate advantages for their clients, including more productive and efficient 1:1 meetings.

Funding Acknowledgements:

This project was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH110524; PI: M.J. Smith).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Matthew Smith will receive royalties on sales of an adapted version of a virtual reality job interview training tool that will focus on meeting the needs of autistic transition age youth. The data reported in this manuscript were collected as part a trial evaluating the original version of virtual reality job interview training. No other authors report any conflicts of interest.

Previous Presentation: A summary of the results from this study were included in a presentation at the 2023 Society for Social Work and Research meeting.

Contributor Information

Shannon Blajeski, Portland State University School of Social Work, Portland.

Matthew J. Smith, University of Michigan School of Social Work, Ann Arbor

Meghan Harrington, University of Michigan School of Social Work, Ann Arbor

Jeffery Johnson, University of Michigan School of Social Work, Ann Arbor

Brittany Ross, University of Michigan School of Social Work, Ann Arbor.

Addie Weaver, University of Michigan School of Social Work, Ann Arbor

Lisa A. Razzano, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois–Chicago, Chicago; Thresholds, Chicago

Nicole Pashka, Thresholds, Chicago

Adrienne Brown, Thresholds, Chicago

John Prestipino, Thresholds, Chicago

Karley Nelson, Thresholds, Chicago

Tovah Liberman, Thresholds, Chicago

Neil Jordan, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University, Chicago; Center of Innovation for Complex Chronic Healthcare, Edward Hines Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital, Hines, Illinois

Eugene A. Oulvey, State of Illinois Department of Human Services, Chicago

Kim T. Mueser, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University, Boston

Susan McGurk, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University, Boston

Morris D. Bell, Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

Justin D. Smith, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Utah Eccles School of Medicine, Salt Lake City

References

- 1.Drake RE, Bond GR, & Becker DR (2012). IPS Supported Employment: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpine DD, & Alang SM (2021). Employment and economic outcomes of persons with mental illness and disability: The impact of the Great Recession in the United States. Psychiatr Rehabil J, 44(2), 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healthy People 2030. Rockville, MD, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frederick DE & VanderWeele TJ (2019) Supported employment: Meta-analysis and review of randomized controlled trials of individual placement and support. PloS one 4(2), e0212208. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond GR, Drake RE, & Becker DR (2020). An update on individual placement and support. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 390. 10.1002/wps.20784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord SE, McGurk SR, Nicholson J, Carpenter-Song EA, Tauscher JS, Becker DR, Swanson SJ, Drake RE, & Bond GR (2014). The potential of technology for enhancing Individual Placement and Support supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J, 37(2), 99–106. 10.1037/prj0000070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Zeev D, Buck B, Kopelovich S, & Meller S (2019). A technology-assisted life of recovery from psychosis. npj Schizophrenia, 5(1), 15. 10.1038/s41537-019-0083-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Xie H, et al. (2015). Cognitive enhancement treatment for people with mental illness who do not respond to supported employment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 172(9), 852–861. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14030374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MJ, Smith JD, Blajeski S, Ross B, Jordan N, Bell MD, McGurk S, Mueser KT, Burke-Miller J, Oulvey EA, Fleming MF, Nelson K, Brown A, Prestipino J, Pashka N, & Razzano LA (2022). An RCT of virtual reality job interview training for individuals with serious mental illness in IPS supported employment. Psych Serv, 73(9), 1027–1038. 10.1176/appi.ps.202100516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camacho E, Levin L, & Torous J (2019). Smartphone apps to support coordinated specialty care for prodromal and early course schizophrenia disorders: systematic review. J Med Internet Res, 21(11), e16393. 10.2196/16393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauvé G, Buck G, Lepage M et al. Minds@Work: a new manualized intervention to improve job tenure in psychosis based on scoping review and logic model. J Occup Rehabil 32, 515–528 (2022). 10.1007/s10926-021-09995-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curran GM, Landes SJ, McBain SA, Pyne JM, Smith JD, Fernandez ME, Chambers DA, & Mittman BS (2022). Reflections on 10 years of effectiveness-implementation hybrid studies. Frontiers in Health Services—Implementation Science, 2:1053496. 10.3389/frhs.2022.1053496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humm LB, Olsen D, Be M, Fleming M, & Smith M (2014). Simulated job interview improves skills for adults with serious mental illnesses. Stud Health Technol Inform, 199, 50–54. 10.3233/978-1-61499-401-5-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith MJ, Fleming MF, Wright MA, Roberts AG, Humm LB, Olsen D, & Bell MD (2015). Virtual reality job interview training and 6-month employment outcomes for individuals with schizophrenia seeking employment. Schizophr Res, 166(1-3), 86–91. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palinkas LA, & Cooper BR (2017). Mixed methods evaluation in dissemination and implementation science. In Proctor EK, Colditz GA, & Brownson RC (Eds.) Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice, 335–353, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond GR (2004). Supported employment: Evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J, 27, 345–359. 10.2975/27.2004.345.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker DR, Swanson SJ, Reese SL, Bond GR, & McLehman BM (2015). Supported employment fidelity review manual. A Companion Guide to the Evidence-Based IPS Supported Employment Fidelity Scale. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MJ, Ginger EJ, Wright K, Wright MA, Humm LB, Olsen D, Bell MB, & Fleming MF (2014). Virtual reality job interview training in individuals with psychiatric disabilities. J Nerv Ment Dis, 202, 659–667. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huffcutt AI (2011). An empirical review of the employment interview construct literature. Int J Sel Assess 19, 62–81. 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2010.00535.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell MD, & Weinstein A (2011). Simulated job interview skill training for people with psychiatric disability: feasibility and tolerability of virtual reality training. Schizophr Bull, 37 Suppl 2, S91–97. 10.1093/schbul/sbr061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, & Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, Boynton MH, & Halko H (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci, 12, 108. 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherwood K, Smith MJ, Ross B, Johnson J, Harrington M, Blajeski S, DaWalt L, Bishop L, & Smith JD (2023). Mixed methods implementation evaluation of virtual interview training for transition-age autistic youth in pre-employment transition services. J Vocat Rehabil, 58, 139–154. 10.3233/JVR-230004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith MJ, Sherwood K, Ross B, Oulvey EA, Atkins MS, Danielson EA, Jordan N, & Smith JD (2022). Scaling out virtual interview training for transition age youth: a quasi-experimental hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 45(4), 213–227. 10.1177/21651434221081273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith MJ, Smith JD, Jordan N, Sherwood K, McRobert E, Ross B, Oulvey EA, & Atkins MS (2021). Virtual reality job interview training in transition services: results of a single-arm, noncontrolled effectiveness-implementation hybrid trial. J Spec Educ Technol, 36(1), 3–17. 10.1177/0162643420960093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooke J (1986). System Usability Scale (SUS): a “quick and dirty” usability scale. In Jordan PW, Thomas BA, & Weerdmeester AL (Eds.), Usability Evaluation in Industry. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dedoose Version 9.0.17, (2021), Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; www.dedoose.com [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miles MB, & Huberman AM (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, & Lowery J (2022). The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement Sci, 17(1), 75. 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodge AC, Kaufman L, & Stevens Manser S (2017). Barriers to implementing person-centered recovery planning in public mental health organizations in Texas: results from nine focus groups. Adm Policy Ment Health 44(3), 413–429. 10.1007/s10488-016-0732-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MJ, Graham AK, Sax R, Spencer ES, Razzano LA, Smith JD, & Jordan N (2020). Costs of preparing to implement a virtual reality job interview training programme in a community mental health agency: A budget impact analysis. J Eval Clin Pract, 26(4), 1188–1195. 10.1111/jep.13292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry N, Lobban F, Emsley R, & Bucci S (2016). Acceptability of interventions delivered online and through mobile phones for people who experience severe mental health problems: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res, 18(5): e121. 10.2196/jmir.5250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ben-Zeev D (2017). Technology in mental health: creating new knowledge and inventing the future of services. Psych Serv, 68(2), 107–108. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Zeev D, Drake RE, Corrigan PW, Rotondi AJ, Nilsen W, & Depp C (2012). Using contemporary technologies in the assessment and treatment of serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatr, 15(4), 357–376. 10.1080/15487768.2012.733295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Üstel P, Smith MJ, Blajeski S, Johnson JM, Butler VG, Nicolia-Adkins J, Ortquist MJ, Razzano LA, & Lapidos A (2021). Acceptability and feasibility of peer specialist-delivered virtual reality job interview training for individuals with serious mental illness: A qualitative study. J Technol Hum Serv, 219–231. 10.1080/15228835.2021.1915924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blajeski SM, Smith MJ, Harrington M, Johnson J, Oulvey EA, Mueser KT, McGurk SR, & Razzano LA (Accepted, April 2023) Critical elements in the experience of virtual reality job interview training for unemployed individuals with serious mental illness: implications for IPS Supported Employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.