Abstract

Introduction: Aesthetic liposuction represents one of the most commonly performed cosmetic procedures worldwide. The purpose of this article is to examine and synthesize reported complication rates and explore the analytical prospect of possible patient or procedure-related predictive factors associated with specific complications. Methods: A systematic review was performed using the Pubmed, Cochrane, and Embase databases in line with specific criteria set to ensure an accurate assessment of complication rates; extracted data was synthesized through a random-effects model and meta-analysis of proportions. Results: A total of 60 studies were included in the meta-analysis, representing 21,776 patients undergoing aesthetic liposuction. Most studies followed an observational design. The overall complication rate was 12% (95% confidence interval [CI] 8%, 16%). When stratifying according to specific complications, the incidence of contour irregularities was determined to be 2% (95% CI 1%, 2%), seroma 2% (95% CI 1%; 2%), hematoma 1% (95% CI 0%, 1%), surgical site infection 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%), fibrosis or induration 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%), and pigmentary changes 1% (95% CI 1%, 1%), among others. A meta-regression to identify patient- or procedure-related factors associated with greater complication rates proved infeasible given the nature of the available data. Conclusion: Overall, liposuction demonstrated a relatively low complication rate profile, however, a considerable degree of heterogeneity exists within the examined literature preventing the recognition of predictive risk factors. While this calls for efforts to establish consensus on unified methods of outcomes reporting, the present meta-analysis can serve to provide practitioners with an evidence-based reference to improve informed consent and inform clinical guidelines, specifically pertaining to the incidence of commonly encountered complications in aesthetic liposuction, of which presently available survey studies and database queries remain devoid.

Keywords: liposuction, complications, aesthetic, safety, consent

Résumé

Introduction : La liposuccion esthétique est l’une des procédures esthétiques le plus souvent réalisées dans le monde. L’objectif de cet article est d’étudier et synthétiser les taux de complications rapportés et d’explorer la possibilité d’analyse de possibles facteurs prédictifs liés aux patients ou à la procédure en association avec des complications spécifiques. Méthodes : Une revue systématique a été exécutée à partir des bases de données Pubmed, Cochrane et Embase selon un ensemble de critères spécifiques pour assurer une évaluation précise des taux de complications; les données extraites ont été synthétisées par un modèle d’effets aléatoires et une méta-analyse des pourcentages. Résultats : Un total de 60 études a été inclus dans la méta-analyse, représentant 21 776 patients subissant une liposuccion esthétique. La plupart des études étaient observationnelles. Le taux global de complications était de 12% (IC à 95% : 8% à 16%). Après stratification selon des complications spécifiques, les incidences suivantes — parmi d’autres — ont été établies : irrégularités de contour a été établi à 2% (IC à 95% : 1% à 2%), sérome 2% (IC à 95% : 1% à 2%), hématome 1% (IC à 95% : 0% à 1%), infection du site opératoire 1% (IC à 95% : 1% à 2%), fibrose ou induration 1% (IC à 95% : 1% à 2%) et modification de la pigmentation 1% (IC à 95% : 1% à 1%). Une méta-régression visant à identifier des facteurs liés aux patients ou à la procédure pour les taux de complications les plus élevés s’est avérée infaisable, compte tenu de la nature des données disponibles. Conclusion : Globalement, la liposuccion a montré un relativement bas profil en termes de taux de complications. Il existe cependant une hétérogénéité considérable dans les publications étudiées, empêchant d’identifier des facteurs de risque prédictifs. Cela appelle à des efforts en vue de l’établissement d’un consensus sur des méthodes uniformisées de déclaration des résultats, mais la présente méta-analyse peut permettre aux praticiens de disposer d’une référence basée sur des constatations probantes pour améliorer le consentement éclairé et enrichir les lignes directrices cliniques, en particulier pour ce qui concerne l’incidence des complications fréquemment vues dans la liposuccion esthétique. En effet, les études, enquêtes et bases de données actuellement disponibles en sont dépourvues.

Introduction

Since Illouz's landmark presentation in 1982 during the American Society of Plastic Surgery meeting, liposuction has experienced a remarkable rise.1–4 Today, liposuction represents one of the most commonly performed aesthetic procedures with a 31.9% rise in frequency from 2014, and ∼1 billion dollars spent annually in the United States alone. 5 Throughout its evolution, suction-lipoplasty has undergone a variety of modifications and additions as newer technologies, knowledge of anatomy, fluid dynamics, instruments, and techniques continue to evolve. 6

Although generally seen as a relatively benign intervention, the procedure is not without its complications. Multiple publications, each with their respective focus, design, and limitations, have provided unique insight on adverse events associated with liposuction, including a host of minor and major complications, both local and systemic, and procedure-specific or anesthesia-related. 7 A database inquiry of 4534 patients undergoing liposuction reported a total complication rate of 1.5%. 8 In contrast, a survey study encompassing 1249 procedures reported an overall complication rate of 9.3%, 9 while a retrospective analysis of 655 patients reports an overall complication rate of 22.3%, 10 with no major complications when liposuction was performed alone. While such large-scale primary studies can shed valuable insight into the rate of major complications and adverse sequelae encountered in aesthetic liposuction, by nature of study design and publication bias, these efforts may fall short in providing accurate insight into the rate of common complications frequently encountered in aesthetic surgery practice.

The objective of this study is thus to quantify the reported rate of relatively common complications associated with aesthetic liposuction through a meta-analysis of published primary clinical studies, with an emphasis on local cosmetic-related adverse events, and to address any inherent limitations in the evaluated literature which may pose a challenge to this effort.

Methods

Search Strategy

A systematic review and subsequent meta-analysis were carried out in full accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 11 as well as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 12

The MEDLINE via Pubmed, Embase, and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases were queried. The following keywords were used: (“Liposuction” or “suction lipectomy” or “lipoplasty”) in combination with (“complications” or “adverse events”). A manual citation search followed through relevant retrieved articles and key journals to supplement the initial protocolized search.

Primary screening was conducted based on title and abstract review, and relevant articles subsequently underwent full-text review. Screening was performed by 2 independent reviewers. The authors resolved eligibility disagreements by means of consensus. Data extraction was carried out by 2 reviewers for analysis. Key data, such as study design, nature of intervention, sample size and patient factors, perioperative setting, anesthesia protocol, mean lipoaspirate volume, and proportion of patients with outcomes of interest were extracted (ie contour irregularities, seroma, hematoma, infection, tissue loss or necrosis, pigmentary changes, as well as other complications in addition to the total number of patients with complications), when available.

Eligibility Criteria

Original primary research articles, including experimental and observational designs, containing patient cohorts that underwent exclusive aesthetic liposuction of any body site (including liposuction-only breast interventions), utilizing any invasive modality, with sufficient, extractable, unambiguous reporting on complications, published in English after the year 2000 were included. Publications were excluded if substantial data was missing, or if the patient cohort underwent liposuction for nonaesthetic purposes, liposuction with cointerventions, or the pooling of outcomes with concomitant procedures was done. Case reports, reviews, surveys, background, and database articles were also excluded, as were publications with <1 month of follow-up. If a study contained multiple arms, data from only those that fit the inclusion criteria were extracted. Cohorts containing patients selected based on a specific outcome were excluded, as were cohorts with <10 patients to avoid publication bias and overreporting on complication rates, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis is Presented Herein.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Primary cohorts undergoing aesthetic liposuction (human subjects) only | Case reports, database or survey inquiries, and reviews |

| English language publications | Concomitant procedures performed |

| Publications in or following the year 2000 | Pooled outcomes (with a proportion of cohort undergoing nonliposuction procedures) |

| Sample size (n = 10 or larger) | Studies prior to the year 2000, or non-English publications |

| Any invasive liposuction modality | Less than 1 month follow-up |

| Sufficient proportional data | Ambiguous data (incomplete and nonspecific reporting) |

Defining Complications

Major complications were aggregated and defined mainly as a systemic adverse event that may potentially be life-threatening, or require urgent pharmaceutical or surgical intervention. Included as well were “organ-threatening” complications, for example. direct visceral organ injury, optic neuropathy, or named major nerve-sectioning (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of Complications, as Either Major or Minor, is Presented. Major Complications Were Defined Mainly as a Systemic Adverse Event, Potentially Life-Threatening or Requiring Urgent Pharmaceutical or Surgical intervention.

| Minor complications | Major complications |

|---|---|

| Contour irregularities (including overresection and asymmetry) | Overwhelming infection (eg sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, or toxic shock syndrome) or abscess formation |

| Seroma | Anesthesia-related (cardiopulmonary or airway complications) including local anesthesia-related toxicity |

| Hematoma | Tumescent fluid-related fluid or electrolyte imbalance |

| Localized infection | Visceral structure or vital organ injury (including major nerve injury or inflammation) |

| Thermal injury | Deep venous thrombosis or embolism |

| Ecchymosis or bruising | Significant hypovolemia or hypotension |

| Edema or swelling | Other embolic events (ie fat or microscopic fat embolism syndrome) |

| Pigmentary changes | Disseminated intravascular coagulation or major hemorrhage |

| Entry site complications (aberrant scarring or dehiscence) | Pulmonary (including pneumonia and pulmonary edema), cardiac or renal problems |

| Sensory changes | Hospital readmission or emergency room visits |

| Minor allergic reactions | Death |

| Garment-related complications (eg ulcers) | — |

Minor complications were defined as local adverse events, which may or may not require surgical intervention on a nonurgent basis. Pain or “recurrence” of the condition was not considered a complication given the subjective nature of this outcome and heterogeneity in reporting strategies employed. Infections were considered minor if they were deemed localized and did not require surgical drainage of an abscess. A designation of overcorrection, as well as asymmetry, was added to the contour irregularity category. Undesirable entry site complications were defined as unsightly scar formation or dehiscence of a primarily approximated incision site. Paresthesia was defined as any sensory change of the treated sites, including temporary changes. If complete sensory loss or pain was attributed to a direct nerve injury, this was considered a major complication. Skin loss was defined as tissue necrosis, not due to a thermal injury, that is directly associated with the procedure (ie separate from pressure-related ulceration).

Minor complications were reported separately, when statistically feasible. These were defined as local adverse events that may or may not require surgical intervention on a nonurgent basis (Table 2). Pain or “recurrence” of the condition was not considered a complication given the subjective nature of this outcome and heterogeneity in reporting strategies employed. Infections were considered minor if they were deemed localized and did not require surgical drainage of an abscess.

Undesirable entry site complications were defined as unsightly scar formation (eg hypertrophic or widened scars) or dehiscence of a primarily approximated incision site. Paresthesia was defined as any sensory change (ie hypo or hyperalgesia, dysesthesia) of the treated sites, including temporary changes. If complete sensory loss or pain was attributed to a direct nerve injury, this was added to the major complication incidence. Skin loss was defined as tissue necrosis, not due to a thermal injury, that is directly associated with the procedure (ie separate from pressure-related ulceration). A designation of overcorrection, as well as asymmetry, was added to the contour irregularity category. Suction-assisted and power-assisted liposuction (PAL) cohorts were excluded from the analysis of thermal injury incidence to avoid underestimation of incidence, given that this complication is unique to laser- and ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL). Infrequent complications were not reported separately, however, were still included in the calculation of the overall complication rate. The overall complication rate was calculated as the total number of complications (as per the author’s criteria) as a weighted proportion of the total number of patients within each cohort.

Statistical Analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using the aggregated data. Proportions were calculated as the ratio of the number of affected patients to the total sample size. Proportions are provided with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For all studies, a meta-analysis was performed for each outcome. Combined with the inspection of forest plots, the I2 index, and the τ2 statistics were utilized to investigate statistical heterogeneity. Heterogeneity based on the I2 statistic was defined as low (25%), moderate (50%), and high (75%). Given the high degree of heterogeneity, the authors proceeded with a random-effects model for overall complications with a logit transformation. Studies from which a specific complication rate was not extractable with confidence were excluded from a subgroup analysis of that particular outcome. Publication bias was not statistically pursued given the substantial heterogeneity in addition to the design of a meta-analysis of proportions. Meta-analyses and sub-analyses were performed using the R software (The R Project for Statistical Computing, R version 3.2.1). 13

Results

A total of 3768 papers were retrieved after the removal of duplicates; 60 papers were included in the final synthesis following abstract and full-text review. An elaboration on the search strategy, as well as the inclusion and exclusion process, is presented in Figure 1. Table 3 provides a summary of all primary articles included in the meta-analysis.6,14–74 Most studies were of an observational design. Within included cohorts, the majority of procedures utilized either suction-assisted liposuction (SAL) or laser-assisted liposuction (LAL), followed by UAL, radiofrequency-assisted liposuction (RFAL), and PAL. Among studies that provided sufficient procedural and patient demographic data, the overwhelming majority performed low to moderate volume aspiration (<5 L) and female patients constituted the vast majority of included subjects. Twelve studies strictly used general anesthesia for all patients, while the majority used a combination tumescent anesthesia with or without sedation, and 7 cohorts were variable.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy, conducted in accordance with the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, as well as the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines

Table 3.

Synthesis of Studies and Outline of Study Characteristics That met the Inclusion Criteria for the Meta-Analysis.

| Author | Year | Study design | Country of origin | n | Type of liposuction | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz and McBean 35 | 2008 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 537 | LAL | Not specified |

| Duncan 22 | 2012 | Prospective randomized-controlled trial | USA | 12 | SAL versus SAL + RFAL | Abdomen |

| Giugliano et al 24 | 2004 | Prospective comparative | Italy | 60 | SAL | Variable: abdomen, hips, and thighs |

| Roland 56 | 2012 | Prospective series | Switzerland | 320 | SAL | Neck and other sites |

| Boeni 16 | 2011 | Prospective series | Switzerland | 4380 | SAL | Variable: neck, arms, female breast, abdomen, flanks, back, buttocks, and lower extremity |

| Valizadeh et al 69 | 2016 | Randomized clinical trial | Iran | 18 | LAL | Submental region |

| 18 | SAL | |||||

| Keramidas and Rodopoulou 37 | 2016 | Prospective series | Greece | 55 | RFAL | Neck and lower face (jowls) |

| Leclère et al 44 | 2015 | Prospective series | Spain | 10 | LAL | Submental region |

| Hurwitz and Smith 30 | 2012 | Prospective series | USA | 17 | RFAL | Variable: Arms, abdomen, and thighs |

| Moskovitz et al 49 | 2007 | Prospective series | USA | 20 | UAL | Female breast |

| Cohen et al 20 | 2012 | Prospective series | USA | 23 | SAL | Abdomen |

| Habbema 26 | 2009 | Prospective series | Netherlands | 151 | PAL | Female breast |

| Boni 17 | 2006 | Prospective series | Switzerland | 38 | PAL | Male breast |

| Wall and Lee 71 | 2016 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 129 | PAL | Variable: Face, neck, upper extremity, chest, lower extremity, abdomen, and flanks |

| Chia and Theodorou 19 | 2012 | Prospective series | USA | 581 | LAL | Variable: Neck, upper extremity, male breast, abdomen, flanks, back, pubic region, and lower extremity |

| Jacob et al 34 | 2000 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 20 | SAL | Neck |

| Kim et al 38 | 2011 | Retrospective chart review | Korea | 682 | PAL | Variable; not specified in detail |

| 884 | PAL + UAL | |||||

| 832 | PAL + UAL | |||||

| Commons et al 21 | 2001 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 514 | SAL | Variable; not specified in detail |

| 117 | UAL | |||||

| Omranifard 50 | 2003 | Cross-sectional study | Iran | 20 | UAL | Abdomen |

| Habbema 27 | 2009 | Retrospective chart review | Netherlands | 3240 | SAL | Variable: Neck, upper extremity, male and female breast, abdomen, flanks, back, buttocks, and lower extremity |

| Wang et al 72 | 2018 | Retrospective chart review | China | 83 | SAL | Variable: Abdomen, waist, flanks, back, and lower extremity |

| Roustaei et al 57 | 2009 | Prospective series | Iran | 609 | UAL | Variable: Abdomen, back, buttocks, breast, upper extremity, and lower extremity |

| Blugerman et al 15 | 2010 | Prospective series | Argentina | 23 | RFAL | Variable: Abdomen and hips |

| Katz et al 36 | 2003 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 207 | PAL | Variable; not specified in detail |

| Innocenti et al 31 | 2014 | Retrospective chart review | Italy | 118 | SAL | Neck |

| Zoccali et al 74 | 2012 | Prospective series | Italy | 797 | UAL | Variable: Chest, breast, chin, abdomen, flanks, hips, gluteal, upper extremity, and lower extremity |

| Perez and Tetering 53 | 2003 | Retrospective chart review | USA and Netherlands | 351 | UAL | Variable: Abdomen, flank, back, lower extremity, and face |

| Mellul et al 47 | 2006 | Case series | USA | 14 | SAL | Female breast |

| Saleh et al 60 | 2009 | Prospective series | Egypt | 60 | SAL | Variable: Waist, hips, buttocks, and lower extremity |

| Zhang et al 73 | 2015 | Retrospective chart review | China | 4000 | SAL | Variable: Hips, flanks, and lower extremity |

| Goldman 25 | 2006 | Prospective series | Brazil | 82 | LAL | Submental region |

| Trelles et al 68 | 2013 | Prospective series | France | 28 | LAL | Male breast |

| Branas and Moraga 18 | 2013 | Retrospective chart review | Spain | 330 | LAL | Variable: Lower extremity, hip |

| 100 | SAL | |||||

| Scuderi et al 62 | 2000 | Prospective, randomized comparative series | Italy | 15 | SAL | Lower extremity |

| 15 | UAL | |||||

| 15 | PAL | |||||

| McBean and Katz 46 | 2009 | Prospective series | USA | 20 | LAL | Variable; not specified in detail |

| Hodgson et al 28 | 2005 | Retrospective chart review | United Kingdom | 13 | UAL | Male breast |

| Leclère et al 41 | 2014 | Prospective series | France | 30 | LAL | Neck and submental region |

| Leclère et al 42 | 2014 | Prospective series | France | 30 | LAL | Lower extremity |

| Walden et al 70 | 2004 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 12 | SAL | Male breast |

| Theodorou and Chia 67 | 2013 | Prospective series | USA | 40 | RFAL | Upper extremity |

| Sun et al 65 | 2009 | Case series | China | 35 | LAL | Variable: Face, neck, mental region, upper extremity, and abdomen |

| Reynaud et al 55 | 2009 | Retrospective chart review | France | 334 | LAL | Variable: Chin, abdomen, hips, flanks, back, buttocks, upper extremity, and lower extremity |

| Fulton et al 23 | 2001 | Case series | USA | 15 | SAL | Female breast |

| Moreno-Moraga et al 48 | 2012 | Prospective series | France | 30 | LAL | Lower extremity |

| Saariniemi et al 58 | 2015 | Prospective series | Finland | 61 | WJAL | Variable: Abdomen and thigh |

| Swanson 66 | 2013 | Prospective series | USA | 384 | UAL | Variable; not specified in detail |

| Leclère et al 39 | 2015 | Prospective series | Spain | 45 | LAL | Upper extremity |

| Sadove 59 | 2005 | Retrospective chart review | Israel | 25 | SAL | Female breast |

| Sasaki 61 | 2012 | Prospective series | USA | 19 | LAL | Midface and neck |

| Hong et al 29 | 2012 | Prospective series | Korea | 57 | LAL | Upper extremity |

| Paul et al 51 | 2011 | Prospective series | USA | 24 | RFAL | Variable: Abdomen and hips |

| Duncan 22 | 2012 | Prospective series | USA | 11 | RFAL | Upper extremity |

| Ion et al 32 | 2011 | Case series | United Kingdom | 42 | RFAL | Variable: Abdomen, flanks, cervicodorsal, and breast |

| Paul and Mulholland 52 | 2009 | Case series | USA | 20 | RFAL | Variable: Hips, abdomen, flanks, male breast, upper extremity, and lower extremity |

| Song et al 63 | 2014 | Retrospective chart review | China | 331 | SAL and UAL | Male breast |

| Petty et al 54 | 2010 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 50 | UAL | Male breast |

| Licata et al 45 | 2013 | Retrospective chart review | Italy | 230 | LAL | Variable: Neck, flanks, hips, male breast, upper extremity, and lower extremity |

| Leclère et al 43 | 2012 | Prospective series | France | 359 | LAL | Variable: Neck, jowls, abdomen, flanks, back, buttocks, pubic region, male breast, upper extremity, and lower extremity |

| Alexiades-Armenakas 14 | 2012 | Prospective, randomized comparative series | USA | 12 | LAL | Neck and submental region |

| Leclère et al 40 | 2016 | Prospective series | France | 22 | LAL | Upper extremity |

Abbreviations: LAL, laser-assisted liposuction; SAL, suction-assisted liposuction; RFAL, radiofrequency-assisted liposuction; WJAL, water jet-assisted liposuction; UAL, ultrasound-assisted liposuction; PAL, power-assisted liposuction.

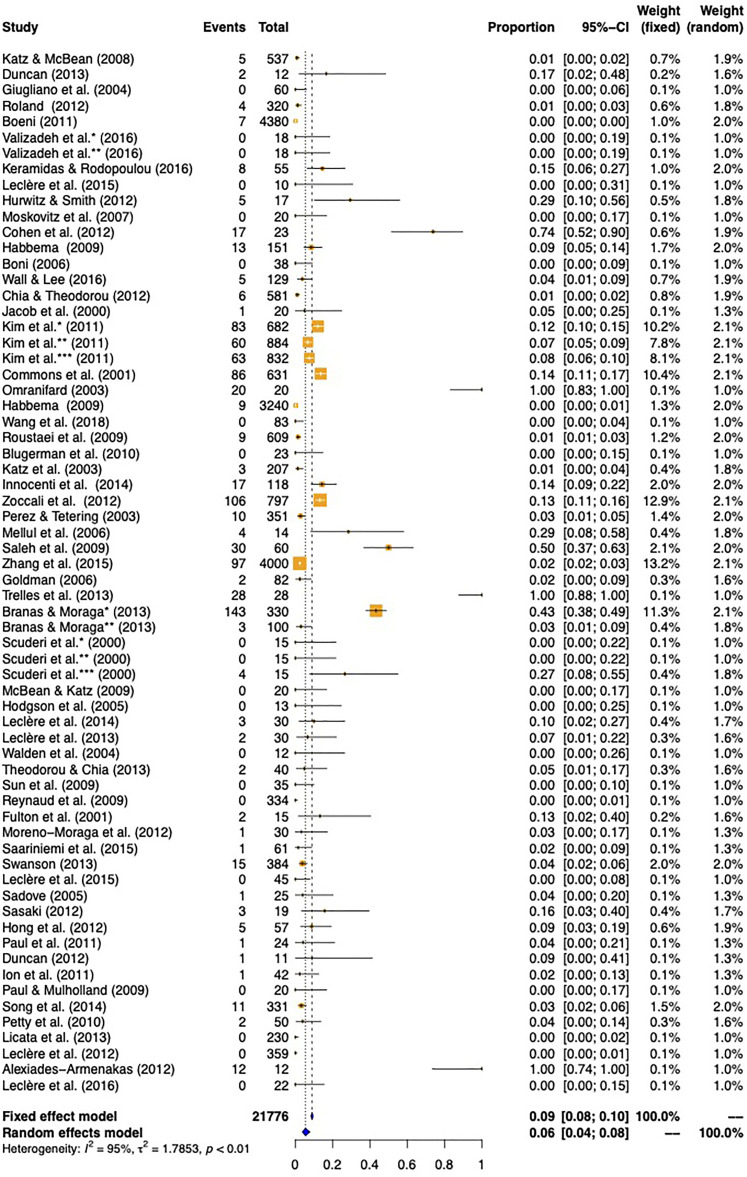

Overall complications: The rate of total complications (including major and minor complications) was 12% (95% CI 8%, 16%). When the incidence of ecchymosis and edema were removed from the analysis, the total rate was reduced to 6% (95% CI 4%, 8%). In accordance with the definitions set for the present study, the total major complication rate was 1% (95% CI 0%, 1%) and the total minor complication rate was 5% (95% CI 4%, 8%) (Table 2). Forest plots are presented in Figures 2 to 4, and Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Total complication rate, excluding ecchymosis and edema.

Figure 3.

Total major complication rate as determined using both the fixed-effects and random-effects models for meta-analysis of articles meeting the inclusion criteria for review.

Figure 4.

Total minor complication rate as determined using both the fixed-effects and random-effects models for meta-analysis of articles meeting the inclusion criteria for review.

Specific complications: The reported rate of ecchymosis was established to be 3% [95% CI 1%, 7%); swelling as 2% (95% CI 1%, 3%), contour irregularity as 2% (95% CI 1%, 2%); seroma 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%); hematoma 1% (95% CI 0%, 1%); surgical site infection 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%); and thermal injury as 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%). Naturally, no patients in the SAL or PAL groups suffered any thermal injury, in contrast to 7 out of 2809 patients in the LAL group (0.25%), 22 out of 4092 in the UAL group (0.54%), 4 out of 250 patients in the RFAL (1.6%) affected. Pigmentary changes occurred at a rate of 1% (95% CI 1%, 1%), with no incidence in the RFAL treatment group. Paresthesia occurred at rate of 1% (95% CI 0%, 2%); fibrosis, nodularity, and induration at 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%); skin loss at 1% (95% CI 1%, 2%); and undesirable entry site complication at 1%, as per the definition established in the current study (95% CI 1%, 1%) (Supplementary Figures 2-13; Table 4). No deaths were reported; 1 case of thrombophlebitis was acknowledged with no embolic event. 74 Other infrequent complications not included in specific outcome analysis are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4.

Overall, Major, Minor, and Individual Complication Rates, as Identified and Synthesized in the Present Meta-Analysis Using a Random-Effects Model and Meta-Analysis of Proportions, are Presented Herein.

| Complication | Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Total (overall) complication rate | 12 |

| Total complication rate* | 5 |

| Major complication rate | 1 |

| Minor complication rate* | 5 |

| Ecchymosis | 3 |

| Edema | 2 |

| Contour irregularity | 2 |

| Seroma | 1 |

| Hematoma | 1 |

| Surgical site infection | 1 |

| Thermal injury | 1 |

| Pigmentary changes | 1 |

| Fibrosis or induration | 1 |

| Paresthesia | 1 |

| Skin loss | 1 |

| Undesirable entry site events | 1 |

*Excluding ecchymosis and edema.

Table 5.

Incidence of Infrequent Complications Identified in the Present Study From Articles Meeting the Inclusion Criteria.

| Complication | Total incidence (n) |

|---|---|

| Hypotension or orthostatic hypotension50,57 | 17 |

| Garment-induced pressure necrosis21,60 | 9 |

| Contact dermatitis or urticaria21,26,57,66 | 8 |

| Drug allergic reaction16,27,66 | 5 |

| Pulmonary edema21,66 | 5 |

| Pneumonia 21 | 1 |

| Deep venous thrombosis 74 | 1 |

| Major mycobacterial infection 73 | 1 |

| Urinary retention 27 | 1 |

| Hemorrhage 34 | 1 |

| Globus pharyngeus 56 | 1 |

| Nerve inflammation 56 | 1 |

Discussion

This study seeks to provide further insight into the complication profile associated with aesthetic liposuction and aid clinicians in providing full disclosure within the spirit of informed consent, as well as explore the present state of the literature to identify procedure- and patient-specific factors associated with higher complications. Given the high degree of heterogeneity identified, the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted in consideration of complication rates established in previous reports, all the while acknowledging the contrast between authors and centers, and potential subjectivity as to what constitutes a complication, as opposed to an undesirable aesthetic result, or an inevitable consequence of the operation (eg in the case of ecchymosis or edema).

As alluded to by Matarasso, 1 the lack of a central registry impairs exact reporting on complications associated with liposuction. Indeed, the published complication rate of certain adverse events may display a dramatic variability. 8 Nevertheless, the underlying factor common to many published cohorts is that liposuction tends to be a safe procedure when performed by trained hands.10,75 In a database inquiry of 4534 patients who underwent liposuction, Chow et al 8 reported a total complication rate of 1.5%. Contrasted to 9.3% in a survey encompassing 1249 procedures, 9 to 22.3% in a retrospective analysis 10 of 655 patients, with no major complications when liposuction was performed alone. The results of this study, including major, minor, and overall complications are within the range of reported rates in the literature.

As noted, the exclusion of edema and ecchymosis from aggregated analyses stems from the nature of included data; while some authors may mention that all patients experienced some degree of edema or bruising, culminating in 100% “complication rate,” others may disregard these as being an inevitable consequence of the operation, and not a complication per se (unless severe enough or persistent beyond a certain subjective limit). Thereby, the inclusion or exclusion of these complications may effectively inflate, or deflate the results, respectively, depending on the surgeon’s point of view. The rate of complications associated with the different liposuction modalities was not included given the notable difference in the number of studies and patients related to each group, precluding reliable interpretation.

Contour irregularities have been cited as the most common complication in suction lipectomy.76,77 In a large database study, Matarasso et al 77 demonstrated a 9.2% rate of irregularities, while another large survey study maintained a rate of 0.26%. 78 Cardenas-Camarena 10 reported a palpable irregularity rate of 7.36% and a visible irregularity rate of 3.25% (although some patients within the cohort underwent concomitant abdominoplasty).

In a commonly cited survey, Pitman and Teimourian 9 reported results of 612 plastic surgeons (1249 liposuction procedures) with the following rates: hypoesthesia (2.6%), seroma (1.6%), edema (1.4%), pigmentation (1%), hematoma (0.8%), infection (0.6%), and skin slough (0.2%). The previously mentioned rates are by no means an exhaustive coverage of all published figures. They do, however, serve to demonstrate the tangible discrepancy within the literature, as well as the fact that although subject to heterogeneity, the results of this study are not anomalous.

Finally, it remains pertinent to consider that while these complications are reported on in terms of prevalence, the severity of these complications, measures necessary for their rectification, and their financial burden, in addition to the patient-specific perception of these complications and their detriment on patient satisfaction and quality of life were all not taken into account. These factors remain essential aspects to consider alongside the incidence data presented to adequately assess the risk–benefit profile of this procedure on a patient-by-patient basis.

Limitations

To appreciate and adequately infer the results of this study, a thorough elaboration of its limitations should be noted. The inclusion and exclusion criteria chosen will undoubtedly introduce bias, such as limiting results to the English language, for example. Due to the set limitation on follow-up time (as the primary aim of the study was to look for aesthetic and local outcomes), some cohorts were excluded, effectively eliminating certain studies with shorter follow-up which may have provided more complete insight on intraoperative or immediate postoperative outcomes such as blood loss, need for transfusion, metabolic derangements, anesthetic-related events or immediate postoperative pain, for example.

The current state of the literature on this specific topic, with a relative lack of randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) and a general dominance of lower quality studies, dictates the quality of evidence and nature of pooled analysis characteristics. Given the type of desired outcome, namely complications, and the relative deficiency in experimental designs in this domain, it was not feasible to restrict study designs to RCTs alone, or even case-control designs. A substantial portion of our data set was retrieved from retrospective or prospective cohorts and case series, which, by design, are better equipped to capture the incidence of complications among a patient population. However, these studies tend to carry biases inherent to their designs (eg underreporting or information bias, publication bias), besides the frequent occurrence of incomplete data. In fact, multiple cohorts were excluded due to incomplete data, but could have been included should further (presumably readily available) data would have been provided. To that end, the authors recommend that future studies report on the incidence of each of the major and minor complications discussed in this manuscript, as presented in Table 2. Furthermore, should there exist an absence of certain complications, the authors recommend that the incidence is reported on and specified as zero, rather than omitting their mention as a whole. This serves to provide the readership with confidence in the authors’ reporting on complications and would permit the more detailed and inclusive synthesis and meta-analysis of data from future cohorts.

The decision to exclude case reports rests within the fact that these, albeit valuable in providing insight into rare, possibly catastrophic events, cannot be used to estimate proportional data. The detriment, however, is that rare adverse events: massive infections, visceral perforation, anesthetic complications, and fatalities, among others, will be invariably missed or understated. This accentuates the importance of interpreting the findings of the present study in consideration of data provided by previous reports using different strategies, such as database queries or large-scale surveys, which may better capture these complications. On the other hand, owing to the method of calculation of proportions with the available data, a certain amount of inflation will likely occur, considering that while some patients will have more than 1 complication, the total number of complications was still calculated out of a proportion of the total sample size. Surveys and database studies were excluded to limit duplication, and subsequent overstating, of complication rate, which again was detrimental to the major complication rate.

Studies conducted prior to the year 2000 were excluded; the rationale being an attempt to add a sense of homogeneity given the differences in techniques, instruments, technologies, and operative protocols that have evolved and changed over the years. Yet the authors recognize that although some studies were published after the year 2000, multiple included cohorts did, in fact, encompass patients that underwent surgery as far back as 1994.

The main challenge faced in the present study was the inconsistency pertaining to what constitutes a true complication according to the primary articles assessed. While some authors might mention a detailed summary of undesirable outcomes and proportions of which, others would acknowledge the presence of adverse events with broad, nonspecific descriptions. Data from the latter cases were avoided. Moreover, some may consider a complication exclusively as an undesirable outcome that requires a corrective intervention, operative or otherwise. Some publications did not provide numeric, prevalence data concerning specific complications, rather, provided measures of central tendency concerning visual analog or Likert scales. Data from these studies were not considered since no insight on incidence could be provided for the meta-analysis.

Finally, the authors acknowledge the heterogeneity pertaining to within-cohort and between-cohort differences in patient characteristics (eg age, body mass index, gender or race), perioperative protocols (eg anesthetic medications and techniques, warming, antibiotics, chemical or mechanical venous thromboembolism prophylaxis), intraoperative technique or site involved (eg breast vs abdomen) and amount of aspirate (low-volume vs high-volume), employed modality of ultrasound, settings of which (hospital or private practice), in addition to instruments as well as differences in the amount and constituents of wetting solutions. All of which coalesce, culminating in a state of heterogeneity that cannot be ignored when interpreting the results of this study; a variability that has been elaborated on by other authors as well. 79 Due to these limitations, the authors were unable to confidently proceed with a meta-regression to explore possible predictive factors of certain or overall complications such as the amount of aspirated fat, type of anesthesia, facility, modality of liposuction or specific patient demographics, among others.

Conclusion

In experienced hands, liposuction continues to be a safe aesthetic procedure; the overall complication rate was determined to be 12% in the present study by means of a meta-analysis of primary clinical studies. Special attention to full-disclosure in operative consent is paramount for maintaining a solid physician–patient relationship and appropriately managing patient expectations. Plastic surgeons should continue to probe the most recent evidence and employ appropriate judgment regarding patient selection, operative protocols, and technologies. Substantial heterogeneity in outcome reporting for liposuction exists which may impair reliable data synthesis. Although not always feasible, further large-scale, robust, and collaborative efforts are needed to clearly define and establish complication rates, as well as predisposing patient- and procedure-specific factors, which may require further attention to continue improving the safety profile of this procedure.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-2-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-3-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-4-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-5-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-6-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-7-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-8-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-9-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-10-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-11-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-12-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-13-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jad Abi-Rafeh https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7483-1515

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Matarasso A, Hutchinson OH. Liposuction. JAMA. 2001;285(3):266-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Illouz YG. History and current concepts of lipoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23(4):721-730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis CM. Early history of lipoplasty in the United States. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;14(2):123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teimourian B, Adham MN. A national survey of complications associated with suction lipectomy: what we did then and what we do now. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(5):1881-1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.surgery.org/media/news-releases/the-american-society-for-aesthetic-plastic-surgery-reports-americans-spent-largest-amount-on-cosmetic-surger. Accessed June 2019. ASfAPSAsocsAa.

- 6.Stephan PJ, Kenkel JM. Updates and advances in liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(1):83-97. quiz 98-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chia CT, Neinstein RM, Theodorou SJ. Evidence-based medicine: liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(1):267e-274e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow I, Alghoul MS, Khavanin N, et al. Is there a safe lipoaspirate volume? A risk assessment model of liposuction volume as a function of body mass index. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(3):474-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitman GH, Teimourian B. Suction lipectomy: complications and results by survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(1):65-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardenas-Camarena L. Lipoaspiration and its complications: a safe operation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(5):1435-1441. discussion 1442-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R Core Team (2013). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing V, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexiades-Armenakas M. Combination laser-assisted liposuction and minimally invasive skin tightening with temperature feedback for treatment of the submentum and neck. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(6):871-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blugerman G, Schavelzon D, Paul MD. A safety and feasibility study of a novel radiofrequency-assisted liposuction technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):998-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boeni R. Safety of tumescent liposuction under local anesthesia in a series of 4,380 patients. Dermatology. 2011;222(3):278-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boni R. Tumescent power liposuction in the treatment of the enlarged male breast. Dermatology. 2006;213(2):140-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branas EB, Moraga JM. Laser lipolysis using a 924- and 975-nm laser diode in the lower extremities. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37(2):246-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chia CT, Theodorou SJ. 1,000 Consecutive cases of laser-assisted liposuction and suction-assisted lipectomy managed with local anesthesia. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(4):795-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SR, Weiss ET, Brightman LA, et al. Quantitation of the results of abdominal liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32(5):593-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Commons GW, Halperin B, Chang CC. Large-volume liposuction: a review of 631 consecutive cases over 12 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1753-1763. discussion 1764-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duncan DI. Improving outcomes in upper arm liposuction: adding radiofrequency-assisted liposuction to induce skin contraction. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32(1):84-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.JE Fulton, Jr, Rahimi AD, Abuzeni P. Breast reduction with tumescent liposuction. Am J Cosmet Surg. 2001;18(1):15-20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giugliano G, Nicoletti G, Grella E, et al. Effect of liposuction on insulin resistance and vascular inflammatory markers in obese women. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(3):190-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldman A. Submental Nd:YAG laser-assisted liposuction. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38(3):181-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Habbema L. Breast reduction using liposuction with tumescent local anesthesia and powered cannulas. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(1):41-50. discussion 50-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habbema L. Safety of liposuction using exclusively tumescent local anesthesia in 3,240 consecutive cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(11):1728-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgson EL, Fruhstorfer BH, Malata CM. Ultrasonic liposuction in the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(2):646-653. discussion 654-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong YG, Sim HB, Lee MY, et al. Three-dimensional circumferential liposuction of the overweight or obese upper arm. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(3):497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurwitz D, Smith D. Treatment of overweight patients by radiofrequency-assisted liposuction (RFAL) for aesthetic reshaping and skin tightening. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(1):62-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Innocenti A, Andretto Amodeo C, Ciancio F. Wide-undermining neck liposuction: tips and tricks for good results. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38(4):662-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ion L, Raveendran SS, Fu B. Body-contouring with radiofrequency-assisted liposuction. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2011;45(6):286-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D ID. Nonexcisional tissue tightening: creating skin surface area reduction during abdominal liposuction by adding radiofrequency heating. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(8):1154-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacob CI, Berkes BJ, Kaminer MS. Liposuction and surgical recontouring of the neck: a retrospective analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(7):625-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz B, McBean J. Laser-assisted lipolysis: a report on complications. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10(4):231-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz BE, Bruck MC, Felsenfeld L, Frew KE. Power liposuction: a report on complications. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(9):925-927; discussion 927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keramidas E, Rodopoulou S. Radiofrequency-assisted liposuction for neck and lower face adipodermal remodeling and contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg Global Open. 2016;4(8):e850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YH, Cha SM, Naidu S, Hwang WJ. Analysis of postoperative complications for superficial liposuction: a review of 2398 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):863-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leclere FM, Alcolea JM, Vogt P, et al. Laser-assisted lipolysis for arm contouring in Teimourian grades I and II: a prospective study of 45 patients. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(3):1053-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leclère FM, Alcolea JM, Vogt PM, et al. Laser-assisted lipolysis for arm contouring in Teimourian grades III and IV: a prospective study involving 22 patients. Plast Surg. 2016;24(1):35-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leclere FM, Moreno-Moraga J, Alcolea JM, et al. Laser assisted lipolysis for neck and submental remodeling in Rohrich type I to III aging neck: a prospective study in 30 patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(6):284-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leclere FM, Moreno-Moraga J, Mordon S, et al. Laser-assisted lipolysis for cankle remodelling: a prospective study in 30 patients. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(1):131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leclere FM, Trelles M, Moreno-Moraga J, Servell P, Unglaub F, Mordon SR. 980-nm laser lipolysis (LAL): about 674 procedures in 359 patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14(2):67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leclere FM, Vogt PM, Moreno-Moraga J, et al. Laser-assisted lipolysis for neck and submental remodeling in Rohrich type IV patients: fact or fiction? J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2015;17(1):31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Licata G, Agostini T, Fanelli G, et al. Lipolysis using a new 1540-nm diode laser: a retrospective analysis of 230 consecutive procedures. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15(4):184-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McBean JC, Katz BE. A pilot study of the efficacy of a 1,064 and 1,320 nm sequentially firing Nd:YAG laser device for lipolysis and skin tightening. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41(10):779-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mellul SD, Dryden RM, Remigio DJ, Wulc AE. Breast reduction performed by liposuction. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(9):1124-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreno-Moraga J, Trelles MA, Mordon S, et al. Laser-assisted lipolysis for knee remodelling: a prospective study in 30 patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012;14(2):59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moskovitz MJ, Baxt SA, Jain AK, Hausman RE. Liposuction breast reduction: a prospective trial in African American women. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(2):718-726. discussion 727-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Omranifard M. Ultrasonic liposuction versus surgical lipectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27(2):143-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul M, Blugerman G, Kreindel M, Mulholland RS. Three-dimensional radiofrequency tissue tightening: a proposed mechanism and applications for body contouring. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35(1):87-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paul M, Mulholland RS. A new approach for adipose tissue treatment and body contouring using radiofrequency-assisted liposuction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(5):687-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez JA, van Tetering JP. Ultrasound-assisted lipoplasty: a review of over 350 consecutive cases using a two-stage technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27(1):68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petty PM, Solomon M, Buchel EW, Tran NV. Gynecomastia: evolving paradigm of management and comparison of techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(5):1301-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reynaud JP, Skibinski M, Wassmer B, Rochon P, Mordon S. Lipolysis using a 980-nm diode laser: a retrospective analysis of 534 procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(1):28-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roland B. Safety of liposuction of the neck using tumescent local anesthesia: experience in 320 cases. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(11):1812-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roustaei N, Masoumi Lari SJ, Chalian M, Chalian H, Bakhshandeh H. Safety of ultrasound-assisted liposuction: a survey of 660 operations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(2):213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saariniemi KM, Salmi AM, Peltoniemi HH, Charpentier P, Kuokkanen HO. Does liposuction improve body image and symptoms of eating disorders? Plastic Reconstr Surg Global Open. 2015;3(7):e461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadove R. New observations in liposuction-only breast reduction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;29(1):28-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saleh Y, El-Oteify M, Abd-El-Salam AE, Tohamy A, Abd-Elsayed AA. Safety and benefits of large-volume liposuction: a single center experience. Int Arch Med. 2009;2(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki GH. Early clinical experience with the 1440-nm wavelength internal pulsed laser in facial rejuvenation: two-year follow-up. Clin Plast Surg. 2012;39(4):409-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scuderi N, Paolini G, Grippaudo FR, Tenna S. Comparative evaluation of traditional, ultrasonic, and pneumatic assisted lipoplasty: analysis of local and systemic effects, efficacy, and costs of these methods. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24(6):395-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song YN, Wang YB, Huang R, et al. Surgical treatment of gynecomastia: mastectomy compared to liposuction technique. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73(3):275-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun Y, Wu SF, Yan S, Shi HY, Chen D, Chen Y. Laser lipolysis used to treat localized adiposis: a preliminary report on experience with Asian patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(5):701-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swanson E. Prospective clinical study of 551 cases of liposuction and abdominoplasty performed individually and in combination. Plast Reconstr Surg Global Open. 2013;1(5):e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Theodorou S, Chia C. Radiofrequency-assisted liposuction for arm contouring: technique under local anesthesia. Plast Reconstr Surg Global Open. 2013;1(5):e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trelles MA, Mordon SR, Bonanad E, et al. Laser-assisted lipolysis in the treatment of gynecomastia: a prospective study in 28 patients. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28(2):375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Valizadeh N, Jalaly NY, Zarghampour M, Barikbin B, Haghighatkhah HR. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of 980-nm diode laser-assisted lipolysis versus traditional liposuction for submental rejuvenation: a randomized clinical trial. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18(1):41-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walden JL, Schmid RP, Blackwell SJ. Cross-chest lipoplasty and surgical excision for gynecomastia: a 10-year experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2004;24(3):216-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wall SH, Jr., Lee MR. Separation, aspiration, and fat equalization: SAFE liposuction concepts for comprehensive body contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(6):1192-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang G, Cao WG, Zhao TL. Fluid management in extensive liposuction: a retrospective review of 83 consecutive patients. Medicine. 2018;97(41):e12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang YX, Lazzeri D, Grassetti L, et al. Three-dimensional superficial liposculpture of the hips, flank, and thighs. Plast Reconstr Surg Global Open. 2015;3(1):e291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zoccali G, Orsini G, Scandura S, Cifone MG, Giuliani M. Multifrequency ultrasound-assisted liposuction: 5 years of experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(5):1052-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rohrich RJ, Beran SJ. Is liposuction safe? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(3):819-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahmad J, Eaves FF, 3rd, Rohrich RJ, Kenkel JM. The American society for aesthetic plastic surgery (ASAPS) survey: current trends in liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(2):214-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matarasso A, Swift RW, Rankin M. Abdominoplasty and abdominal contour surgery: a national plastic surgery survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(6):1797-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hanke CW, Bernstein G, Bullock S. Safety of tumescent liposuction in 15,336 patients. National survey results. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(5):459-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guest RA, Amar D, Czerniak S, et al. Heterogeneity in body contouring outcomes based research: the Pittsburgh body contouring complication reporting system. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;38(1):60-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-2-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-3-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-4-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-5-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-6-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-7-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-8-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-9-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-10-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-11-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-12-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-13-psg-10.1177_22925503221078693 for Complications of Aesthetic Liposuction Performed in Isolation: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis by Albaraa Aljerian, Jad Abi-Rafeh, Thomas Hemmerling and Mirko S. Gilardino in Plastic Surgery