Abstract

Background

Image-guided tumor ablation is the first-line therapy for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with ongoing investigations into its combination with immunotherapies. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibition demonstrates immunomodulatory potential and reduces HCC tumor growth when combined with ablative treatment.

Purpose

To evaluate the effect of incomplete cryoablation with or without MMP inhibition on the local immune response in residual tumors in a murine HCC model.

Materials and Methods

Sixty 8- to 10-week-old female BALB/c mice underwent HCC induction with use of orthotopic implantation of syngeneic Tib-75 cells. After 7 days, mice with a single lesion were randomized into treatment groups: (a) no treatment, (b) MMP inhibitor, (c) incomplete cryoablation, and (d) incomplete cryoablation and MMP inhibitor. Macrophage and T-cell subsets were assessed in tissue samples with use of immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence (cell averages calculated using five 1-μm2 fields of view [FOVs]). C-X-C motif chemokine receptor type 3 (CXCR3)– and interferon γ (IFNγ)–positive T cells were assessed using flow cytometry. Groups were compared using unpaired Student t tests, one-way analysis of variance with Tukey correction, and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn correction.

Results

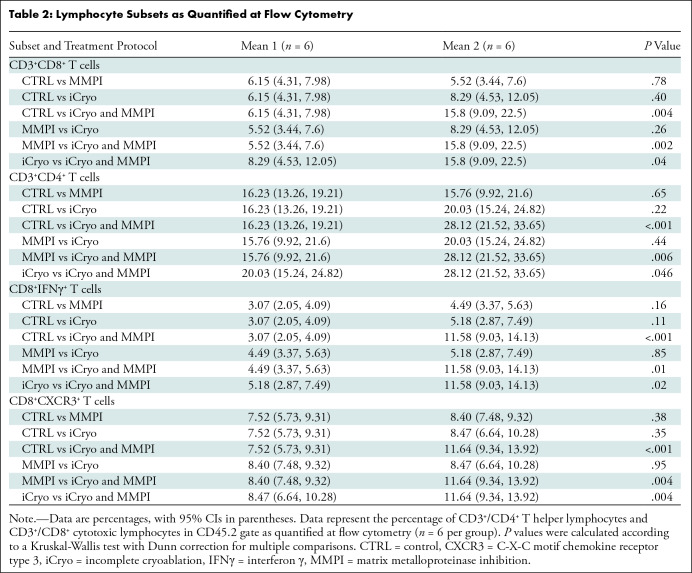

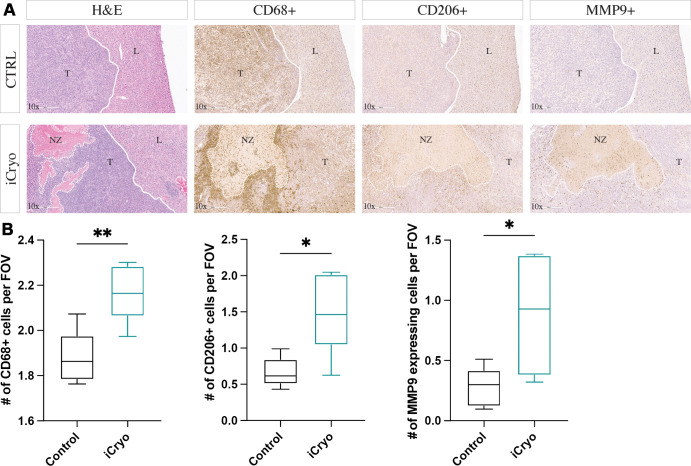

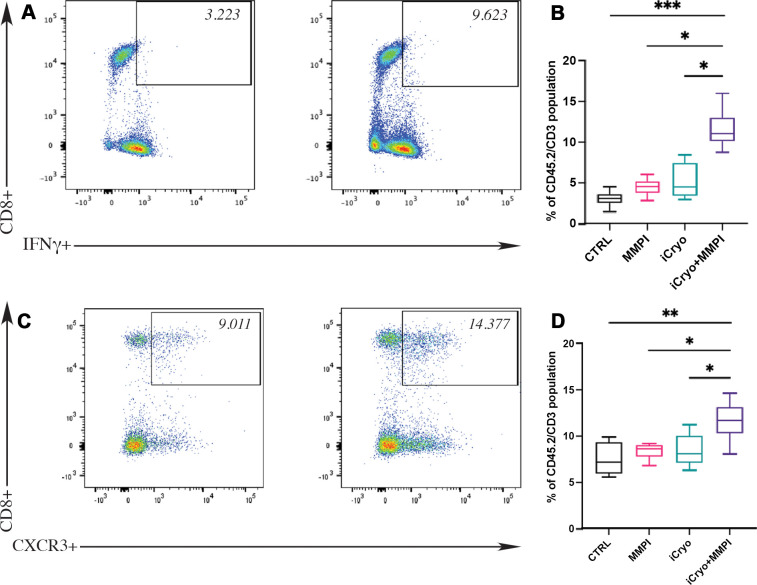

Mice treated with incomplete cryoablation (n = 6) showed greater infiltration of CD206+ tumor-associated macrophages (mean, 1.52 cells per FOV vs 0.64 cells per FOV; P = .03) and MMP9-expressing cells (mean, 0.89 cells per FOV vs 0.11 cells per FOV; P = .03) compared with untreated controls (n = 6). Incomplete cryoablation with MMP inhibition (n = 6) versus without (n = 6) led to greater CD8+ T-cell (mean, 15.8% vs 8.29%; P = .04), CXCR3+CD8+ T-cell (mean, 11.64% vs 8.47%; P = .004), and IFNγ+CD8+ T-cell infiltration (mean, 11.58% vs 5.18%; P = .02).

Conclusion

In a mouse model of HCC, incomplete cryoablation and systemic MMP inhibition showed increased cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell infiltration into the residual tumor compared with either treatment alone.

© RSNA, 2024

Supplemental material is available for this article.

See also the editorial by Gemmete in this issue.

Summary

In an animal model of hepatocellular carcinoma, incomplete cryoablation followed by systemic matrix metalloproteinase inhibition led to greater CD8+ T-cell infiltration into the tumor compared with either treatment alone.

Key Results

■ In a murine hepatocellular carcinoma model, incomplete cryoablation (n = 6) versus no treatment (n = 6) led to greater tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration in residual tumors (mean, 1.52 cells per FOV vs 0.64 cells per field of view [FOV]; P = .03).

■ Incomplete cryoablation with (n = 6) versus without matrix metalloproteinase inhibition (n = 6) led to decreased TAM (mean, 1040 cells per FOV vs 1786 cells per FOV; P = .046) and increased CD8+ T-cell (mean, 15.8% vs 8.29%; P = .04) infiltration in residual tumors.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is projected to be the sixth-leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States, and more than 40 000 cases were newly diagnosed globally in 2023 (1). The majority of individuals diagnosed with HCC present at advanced disease stages, precluding the possibility of curative interventions (2). The most recent Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging guidelines have incorporated immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as the first-line treatment for advanced-stage HCC, following the phase III IMbrave150 trial (3). ICIs target tumorigenic immune tolerance mechanisms that restrict intratumoral cytotoxic CD8+ T cells from tumor cell apoptosis (4). However, the objective response rates to these therapies remain relatively low, ranging from 2% to 30% (5), likely due to the immunologically cold nature of most HCC tumors, characterized by limited tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and an inhibitory immune microenvironment (6,7).

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) recruited to tumors accelerate tumor progression by suppressing immune responses to tumor cells (8) and upregulating expression of the enzyme matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9 upon immunologic challenge (9–11). MMP9 can cleave ligands of the C-X-C motif chemokine receptor type 3 (CXCR3) and thus potentially impact T-cell trafficking and an effective cytotoxic T-cell response during immunotherapy treatment (12–14). Accordingly, MMP9 inhibition in a murine model was shown to increase the trafficking of effector and memory cells into tumors induced by T helper cell 1–type cells secreting interferon (IFN) γ (10). Additionally, local-regional therapies, including ablative techniques, have shown promise for augmenting the antitumor immune response (15). For instance, heat-based ablative therapies lead to protein denaturation, which can reduce the availability of intact antigens capable of eliciting an immune response (16,17). In contrast, due to its unique ability to destroy tumors by freezing, cryoablation releases preserved antigenic structures, improving the ability of immune cells to detect and respond to tumor-specific antigens (18). Despite its limited use in HCC (19), cryoablation could improve patient response to immunotherapy and lead to a resurgence of this technology in liver-directed treatments (20).

Combinations of local-regional therapy and ICIs that can potentially increase immune cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment are under active investigation (21,22). Several ongoing phase III trials are exploring the use of ICIs as adjuvant therapy following ablation for localized HCC (Table S1). The phase I/II study by Duffy et al (23) using subtotal ablation in an advanced setting revealed that the immune stimulation induced in the peripheral region by the ablation procedure could be amplified with the use of ICIs. In the same vein, combining MMP9 inhibition with incomplete radiofrequency ablation was found to decrease tumor invasiveness in an animal liver tumor model (24). Given the well-documented immunologic role of MMP9, it was hypothesized that inhibiting MMP9 may enhance the local immune response in advanced tumors that cannot be ablated completely with use of cryoablation. Thus, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of incomplete cryoablation alone or in combination with MMP inhibition on the local immune response in residual tumors in a Tib-75 HCC murine tumor model.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Model of HCC

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (animal protocol identifier 2022–20262) at Yale University. Animal testing and research conformed to all relevant ethical regulations. Briefly, an immunocompetent orthotopic murine model of HCC was generated by subcapsular injection of 2 million Tib-75 cells of the syngeneic Tib-75 cell line (BNL 1ME A.7R.1, ATCC) suspended in a biologically active matrix material into the liver of BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories). Tib-75 models of HCC have been shown to have a high proportion of TAMs with the potential to diminish antitumor immunity and relatively few T cells (6). This makes the Tib-75 model well suited for studying immune evasion mechanisms in the treatment of HCC. See Appendix S1 and Figure S1 for additional details.

Animal Use and Experiment Design

A total of 60 8- to 10-week-old female BALB/c mice with a single targetable lesion were used. To determine the therapeutic effect of incomplete cryoablation on HCC, six mice received no treatment, and six mice received incomplete cryoablation. Livers and spleens were harvested 7 days after treatment and assessed at histopathologic examination. To assess the impact of MMP inhibition, six mice were administered phosphate-buffered saline, and six mice were administered 30 mg per kilogram of body weight of the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor batimastat (BB-94, catalog no. S7155; Selleck Chemicals) via intraperitoneal injection every 2 days for a total of seven injections (see Appendix S1 and Figure S2 for additional details) (24). Livers and spleens were harvested 48 hours after the last treatment and assessed at histopathologic examination. To assess the combinatorial effect of incomplete cryoablation and MMP inhibition, six mice received incomplete cryoablation and phosphate-buffered saline, and six mice received incomplete cryoablation and MMP inhibitor treatment. The first dose of phosphate-buffered saline or batimastat, respectively, was administered 24 hours after incomplete cryoablation treatment. Livers and spleens were harvested 48 hours after the last treatment and assessed at histopathologic examination. Twenty-four additional mice (n = 6 per group) were randomly assigned to receive (a) no treatment, (b) MMP inhibitor, (c) incomplete cryoablation, or (d) incomplete cryoablation and MMP inhibitor. All animals in this model were killed at day 17, tissues were harvested, and immune cells were assessed using flow cytometry. The experimental study design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Schematic overview of the study design. Approximately 2 million Tib-75 cells suspended in a biologically active matrix material were injected subcapsularily into the liver of 8- to 10-week-old female BALB/c mice to induce hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Mice were randomly divided into four groups 7 days after tumor inoculation. Incomplete cryoablation (iCryo or Cryo) was performed in groups 3 (n = 6) and 4 (n = 6) at day 0 (red diamond). Groups 2 and 4 received intraperitoneal injection of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (n = 6) or a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (n = 6) every 2 days for a total of 7 doses (blue shading). Animals were killed on day 17, and spleen and liver tissues were collected. Flow cytometry was performed on tumor and tumor-adjacent tissue from four different groups: control mice (no treatment), mice treated with the MMP inhibitor (n = 6), mice treated with incomplete cryoablation (n = 6), and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor (n = 6). Histopathologic examination (immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining) was performed on spleen and whole-liver tissue from six different groups: the aforementioned four groups, in addition to phosphate-buffered saline–treated mice (n = 6) and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and phosphate-buffered saline (n = 6).

Ablation Technique

Incomplete cryoablation was performed using a custom-made 17-gauge IceSeed cryoprobe (Visual ICE Cryoablation System, Boston Scientific) with a 1.5-cm active tip inserted in a superficial intrahepatic location. The cryoprobe tip was situated at the quarter-point of the long axis of the tumor for an incomplete ablation, with a target ablation zone covering half of the tumor. Cryoablation was administered twice for 50 seconds at the target temperature of −80°C with a 1-minute pause between the two cycles. The cryoablation ice ball was thawed passively (Fig S3).

Histopathologic Analysis

Tissue harvest and processing.—Mice were killed by inhalation of an isoflurane solution (identifier 029405, Covetrus) with a nonsurvival flow rate. The tumor, along with its adjacent tissue and the spleen, were immediately harvested, sectioned in slices of 3–5 mm, fixed in 10% formaldehyde (identifier UN334, Avantik) overnight, and embedded in paraffin. Tissue samples were cut into 2-μm slices, dewaxed in food-grade distilled essential oil (Histo-Clear, catalog no. 101412–876; Electron Microscopy Sciences), and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes. Following rinsing with deionized water, tissue samples underwent hematoxylin and eosin staining using a nuclei stain (Shandon Gill Hematoxylin, catalog no. 6765009; Epredia) and a cytoplasmic counterstain (Shandon Eosin-Y Stain, catalog no. 6766008; Epredia). For immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence staining, tissue samples, after deionized water wash, underwent heat-mediated antigen retrieval in a sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes at 95°C.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining and analysis.—Standard immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence protocols were used to stain tissues fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Staining was performed using antibodies for cytotoxic T cells (CD8, clone ab217344; Abcam), macrophages (CD68, clone 2449D; R&D Systems), M2-polarized macrophages (CD206, clone AF2535; Novus Biologicals), and MMP9 (clone ab228402, Abcam). See Appendix S1 for additional details.

Cell counting was performed in a blinded manner, where digitally scanned slides were anonymized using a unique identifier to conceal the initial treatment assignment. Quantitative analyses were performed using Aperio ImageScope software (version 12.3, Leica Biosystems) for immunohistochemistry samples and Zeiss Axio Observer fluorescence microscopy (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) for immunofluorescence samples. The average cell count was calculated by analyzing five distinct fields of view (FOVs), with each FOV measuring 1 μm2. See Appendix S1 for additional details.

Flow Cytometry

Mouse tumor and tumor-adjacent tissue was prepared for flow cytometry in accordance with established protocols for the analysis of immune cells in intrahepatic tumor tissue (25). The resulting cell suspension was subjected to a viability stain (7-aminoactinomycin D, clone 420403; BioLegend). Intrahepatic immune cells were stained for hematopoietic cells (Brilliant Violet 510–labeled CD45.2, clone 104; BioLegend), T lymphocytes (Alexa Fluor 488–labeled CD3, clone 17A2; eBioscience), cytotoxic T cells (phycoerythrin-cyanine7–labeled CD8, clone 53–6.7; BioLegend), T helper cells (Alexa Fluor 647–labeled CD4, clone RM4–5; Invitrogen), CXCR3 (phycoerythrin-labeled CXCR3, clone CXCR3–173; BioLegend), and IFNγ (allophycocyanin-cynine7–labeled 52 IFNγ, clone XMG1.2; BioLegend). Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 10.9, Tree Star). The gating strategy is shown in Figure S4, and additional details are reported in Appendix S1.

Statistical Analysis

With use of a randomized block design, mice were divided into subgroups (blocks) based on the date of inoculation. Mice within each block were randomly assigned to treatment conditions to compensate for model-related variations in tumor size. Subgroups consisted of six and four mice for histopathologic and flow cytometric analyses, respectively, with each treatment condition present once per group. Data are presented as means, with 95% CIs provided in Tables 1 and 2. Comparisons were assessed using two-tailed unpaired Student t tests. Analysis of experiments with more than two groups were performed using either a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey correction or a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn correction. Data were analyzed using Prism software (version 9.5.0, GraphPad). P < .05 was considered indicative of statistically significant difference.

Table 1:

Macrophage and Lymphocyte Subsets as Quantified at Immunofluorescence

Table 2:

Lymphocyte Subsets as Quantified at Flow Cytometry

Results

Effects of Incomplete Cryoablation on Macrophage Infiltration and MMP9 Release in the Tumor Microenvironment

All cryoablations conducted on tumor-bearing mice were performed successfully from a technical standpoint, aligning with the objective of intentionally achieving incomplete ablation (Fig 2). Immune cell infiltration in residual Tib-75 tumors was compared between mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and untreated mice (Fig 3). Hematoxylin and eosin stains (Fig 3A) show tumor and adjacent normal liver tissues in treated and untreated mice. They also depict a necrotic zone, centrally displaying disintegrated eosinophilic tissue in the incomplete cryoablation group. Immunohistochemistry showed that on day 7, relative to untreated tumors, residual tumors after incomplete cryoablation displayed a greater proportion of CD68+ myeloid cells (mean, 1.88 cells per FOV vs 2.17 cells per FOV; P = .005) (Fig 3B). An increase in the absolute number and relative percentage of CD206+ TAMs was also observed (mean, 0.64 cells per FOV vs 1.52 cells per FOV [P = .03]; 34.30% vs 69.08% [P = .01]). Immunohistochemistry staining results further revealed diffuse infiltration of CD68+ and CD206+ TAMs in both the residual tumor and the necrotic zone (Fig 3A). Immunohistochemistry also showed increased expression of MMP9 in residual tumor cells adjacent to the necrotic zone 7 days after incomplete cryoablation treatment (mean, 0.11 cells per FOV vs 0.89 cells per FOV; P = .03) (Fig 3).

Figure 2:

Positive and negative control stainings (20× magnification). Staining specificity of the surface markers in BALB/c mice spleen tissue (positive control) and BALB/c mice liver tissue (negative control) was verified before staining experimental tissue. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CD8+), macrophage (CD68+), M2-polarized macrophage (CD206+), and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9+) (A) immunohistochemistry staining and (B) immunofluorescence staining.

Figure 3:

(A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry staining of hepatocellular carcinomas at 7 days in the control group (CTRL) (top row) and incomplete cryoablation group (iCryo) (bottom row). CD68+, CD206+, and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9+) staining was performed to analyze macrophage infiltration, M2-positive macrophage infiltration, and MMP9 expression, respectively. The necrotic ablation zone (NZ) is inside the dotted white line. Tumor (T) and nontumorous (L) tissue are separated with a continuous white line. Magnification, 10×. (B) Box and whisker plots compare the average number of CD68+, CD206+, and MMP9+ intratumoral cells at 7 days in control mice that did not receive ablation (n = 6) and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation (n = 6). Whiskers indicate maximum and minimum values. Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. The line in the middle of the box is plotted at the median. * = P < .05 and ** = P < .01, according to an unpaired t test. FOV = field of view.

Impact of MMP Inhibition on Intratumoral MMP9 Expression and TAM Infiltration

Relative to phosphate-buffered saline–treated mice, mice treated with the MMP inhibitor displayed lower MMP9 expression in the tumor center 48 hours after the last dose (mean, 22 cells per FOV vs 321 cells per FOV; P = .03) (Fig 4A, 4B). Furthermore, mice treated with the MMP inhibitor showed decreased CD206+ TAM infiltration in Tib-75 tumors (mean, 94 cells per FOV vs 813 cells per FOV; P = .02) (Fig 4A, 4C). Decreased MMP9 expression and decreased infiltration of CD206+ TAMs was also seen in tumors of mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and phosphate-buffered saline versus mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor (MMP9: mean, 685 cells per FOV vs 390 cells per FOV [P = .04]; CD206: mean, 1786 cells per FOV vs 1040 cells per FOV [P = .046]) (Fig 4B, 4C). Additional group comparisons are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 4:

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibition (MMPI) decreases intratumoral MMP9 expression and tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration. (A) Representative low-magnification (10×) hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images show Tib-75–induced tumors in BALB/c mice after MMP inhibition with the broad-spectrum inhibitor batimastat (bottom row) relative to control mice receiving injection with the vehicle phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (top row). L = healthy liver, T = tumor. Representative images of immunofluorescence costaining of intratumoral MMP9 expression and infiltration of TAMs (CD206+). Magnification, 20×. DAPI = 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (B, C) Box and whisker plots show quantification of intratumoral (B) MMP9-expressing cells and (C) CD206+ cells in Tib-75 induced–hepatocellular carcinomas. A decrease in intratumoral MMP9+ cells and CD206+ cell infiltration is seen in mice treated with the MMP inhibitor (n = 6) relative to phosphate-buffered saline–treated control mice (n = 6 per group) and in mice treated with incomplete cryoablation (iCryo) and the MMP inhibitor (n = 6) versus mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and phosphate-buffered saline (n = 6). Whiskers indicate maximum and minimum values. Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. The line in the middle of each box is plotted at the median. * = P < .05 and *** = P < .001, according to a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn correction for multiple comparisons. FOV = field of view.

Effect of MMP Inhibition, Incomplete Cryoablation Treatment, and Their Combination on T-Cell Infiltration into Tumors

Compared with untreated controls, mice treated with either incomplete cryoablation or the MMP inhibitor alone showed no difference in the number or percentage of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells as evaluated at immunofluorescence and flow cytometry, respectively (Fig 5A, 5B) (Tables 1, 2). The residual tumors of mice treated with a combination of incomplete cryoablation and MMP inhibition had a mean of 257 CD8+ T cells per FOV at immunofluorescence and a mean of 15.8% CD8+ T cells at flow cytometry, which were both higher compared with untreated control tumors (immunofluorescence: mean, 46 cells per FOV [P = .002]; flow cytometry: mean, 6.15% [P = .004]), tumors treated with the MMP inhibitor only (immunofluorescence: mean, 44 cells per FOV [P = .003]; flow cytometry: mean, 5.52% [P = .002]), and tumors treated with incomplete cryoablation only (immunofluorescence: 91 cells per FOV [P = .04]; flow cytometry: mean, 8.29% [P = .04]) (Fig 5C, 5D).

Figure 5:

Combination treatment with incomplete cryoablation (iCryo) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibition (MMPI) modulate lymphocyte populations in the tumor microenvironment. (A) Representative low-magnification (10×) hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images show the necrotic ablation zone (NZ) in Tib-75–induced tumors in BALB/c mice after treatment with incomplete cryoablation and the vehicle phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (top row) and after treatment with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor batimastat (bottom row). Representative images of immunofluorescence costaining of tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) (magnification, 20×). DAPI = 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, L = healthy liver, T = tumor. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots (n = 1) for CD3 and CD8 coexpression in CD45.2 (hematopoietic) gate show higher infiltration of CD8+ cells in mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor relative to no treatment (CTRL), the MMP inhibitor only, and incomplete cryoablation only. (C) Box and whisker plot shows the average number of CD8+ cells in five random fields of view (FOVs) from the tumor center in immunofluorescence images under 20× magnification (n = 6 per group). (D) Box and whisker plot shows the percentage of CD3+/CD4+ T helper lymphocytes and CD3+/CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes in CD45.2 gate as quantified at flow cytometry (n = 6 per group). Whiskers indicate maximum and minimum values. Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentiles. The line in the middle of each box is plotted at the median. * = P < .05 and ** = P < .01, according to a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn correction for multiple comparisons.

The percentage of CD4+ T cells measured at flow cytometry in residual tumors was higher in the combination therapy group compared with the untreated control group (mean, 28.12% vs 16.23%; P < .001), the MMP inhibitor–treated group (mean, 28.12% vs 15.76%; P = .006), and incomplete cryoablation–treated group (mean, 28.12% vs 20.03%; P = .046) (Fig 5D).

In addition, mice treated with the combination treatment of incomplete cryoablation and MMP inhibitor showed a higher percentage of CD8+ IFNγ-expressing T cells in the residual tumor (mean, 11.58%) compared with untreated control animals (mean, 3.07%; P < .001), animals treated with the MMP inhibitor only (mean, 4.49%; P = .01), and animals treated with incomplete cryoablation only (mean, 5.18%; P = .02) (Fig 6A, 6B). Additional group comparisons are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 6:

Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibition (MMPI) promotes interferon γ (IFNγ)– and chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3)–expressing CD8+ T cells in tumors treated with incomplete cryoablation (iCryo). (A) Representative flow cytometry plot (n = 1) of CD8+IFNγ+ T cells in CD45.2/CD3 gate in tumors treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor compared with mice treated with incomplete cryoablation only. (B) Box and whisker plot compares the percentage of CD8+IFNγ+ T cells (gate on CD45.2+/CD3+ cells) in four treatment groups: control (CTRL) mice (no treatment), mice treated with the MMP inhibitor (n = 6), mice treated with incomplete cryoablation (n = 6), and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor (n = 6). * = P < .05 and *** = P < .001, according to a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn correction for multiple comparisons. (C) Representative flow cytometry plot (n = 1) of CD8+CXCR3+ T cells in CD45.2/CD3 gate in tumors treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor compared with mice treated with incomplete cryoablation only. (D) Box and whisker plot compares the percentage of CD8+CXCR3+ T cells (gate on CD45.2+/CD3+ cells) in the aforementioned four treatment groups. * = P < .01 and ** = P < .001, according to a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons.

The Role of the C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10/CXCR3 Pathway in T-Cell Infiltration through Combined Incomplete Cryoablation and MMP Inhibition

Mice that received the combination treatment showed increased infiltration of CXCR3+CD8+ T cells in the residual tumor (mean, 11.64%) compared with untreated controls (mean, 7.52%; P < .001), mice treated with the MMP inhibitor only (mean, 8.40%; P = .004), and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation only (mean, 8.47%; P = .004) (Fig 6C, 6D). Additional group comparisons are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

Increasing evidence has shown that the combination of local-regional ablative treatment with immunotherapy is a promising strategy for cancers (21,26–28). However, there is a paucity of data characterizing the interaction of cryoimmunologic treatments on the immune landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (18). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of incomplete cryoablation alone or combined with matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibition on the local immune response in residual tumors in a murine HCC model. This study found that incomplete cryoablation (n = 6) versus no treatment (n = 6) led to increased tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration (mean, 1.52 cells per field of view [FOV] vs 0.64 cells per FOV; P = .03) and increased MMP9 expression (mean, 0.11 cells per FOV vs 0.89 cells per FOV; P = .03) in the residual tumor. Compared with animals treated with incomplete cryoablation alone (n = 6), mice treated with incomplete cryoablation followed by administration of an MMP inhibitor (n = 6) showed decreased TAM (mean, 1786 cells per FOV vs 1040 cells per FOV; P = .046) and increased CD8+ T-cell (mean, 8.29% vs 15.8%; P = .04) infiltration in the residual tumor.

After incomplete cryoablation, both infiltration of M2-skewed TAMs and increased tumor MMP9 expression were observed, which align with findings from previous animal studies. Gazzaniga et al (29) reported a peak macrophage infiltration at 7 days in their longitudinal analysis of inflammatory changes after cryoablation in a murine melanoma model. Liu et al (30) reported that M2-skewed macrophages may influence progression of HCC by inducing increased expression of MMP9. Further research indicates that MMP potentially impacts T-cell trafficking (10) and precludes CD8+ T cells from mounting an effective antitumor immune response (11). Similarly, our study shows that incomplete cryoablation alone fails to induce substantial CD8+ T-cell (mean, 5.18% vs 3.07%; P = .11) or CD4+ T-helper-cell (mean, 20.03% vs 16.23%; P = .22) infiltration in comparison with untreated mice.

The findings in our study hold important implications for ongoing clinical trials investigating the use of local-regional ablative treatment in combination with ICIs for the treatment of HCC (31). Though not the standard of care for HCC ablation (19), the advantage of cryoablation lies in its potential to induce a robust tumor-targeted immune response by preserving antigenic structures, rendering it a therapeutic option for patients in more advanced stages of the disease (18). To enhance its antitumoral immune effects, immune adjuvants may be incorporated into cryoablation strategies (22,32). The potential of targeting MMP9 in cancer has been demonstrated by reports showing that MMP9−/− mice exhibited decreased tumor growth and/or reduced metastases in several cancer models (33,34). Although these and other published observations suggest that MMP9 is a compelling therapeutic target, previous efforts to independently target MMPs (including MMP9) showed a general lack of clinical benefit (35). Our study demonstrates that MMP inhibition after incomplete cryoablation effectively inhibits the infiltration of tumor-suppressive mediators into the residual tumor (mean CD206+ cells, 1040 cells per FOV vs 1786 cells per FOV after incomplete cryoablation alone; P = .046). Consequently, adjuvant MMP inhibition aided in overcoming the resistance to immune penetration induced by incomplete cryoablation, as demonstrated by increased CD8+ T-cell immune cell infiltration after combination treatment (mean, 15.8% vs 8.29%; P = .04). Increased CXCR3+CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the residual tumor after combination treatment (mean, 11.64% vs 8.47%; P = .004) suggests that the CXCR3 may be needed for an effective antitumor CD8+ T-cell response. The increase in CD8+IFNγ+ T-cell infiltration (mean, 11.58% vs 5.18%; P = .02) further corroborates this, as IFNγ can induce the chemokine ligands of CXCR3.

This study has several limitations. First, the murine HCC model was established by subcapsular injection of Tib-75 cells into the healthy mouse liver. Human HCC is a heterogeneous cancer that commonly arises in a cirrhotic background, aspects not fully mimicked in our model, potentially affecting the resemblance of the immune response to ablation seen in patients. Second, incomplete cryoablation of a solitary localized lesion may not precisely simulate changes observed in advanced-stage disease, where complete tumor ablation is more challenging and tumor biologic characteristics may differ. Third, the choice of a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor, batimastat, was based on its extensive use in the literature compared with other drugs (36,37). Effects due to the specific inhibition of MMP9 should be validated against the effects mediated by the inhibition of other MMPs. Fourth, we investigated the immune response at 7 days after ablation or 48 hours after the last dose of BB-94. More frequent or prolonged tissue sampling might provide better temporal information on the dynamics of immune response. Finally, although mice were assigned to treatment groups following a randomized block design, replicate experiments at separate times were not conducted for each group; thus, repeatability remains unknown.

In conclusion, our study found that incomplete cryoablation followed by systemic matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibition led to increased cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell infiltration into the residual tumor compared with either treatment alone in an animal model of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The results of this study suggest that cryoablation can modulate the tumor microenvironment directly and that MMP inhibition may enhance the tumor-specific immune responses of cryoablation. These findings hold important implications for the ongoing development of therapeutic strategies combining local-regional therapy with immunomodulators in advanced-stage HCC. In a clinical context, the combination of incomplete cryoablation and adjuvant MMP inhibition shows potential for treating immunologically resistant, or “cold,” tumors in advanced-stage HCC that do not respond to systemic immunotherapy. When complete ablation is challenging to achieve due to the size of the lesion, advanced stage of disease, or adjacent anatomic at-risk structures, incomplete cryoablation with MMP inhibition could be considered as a viable approach to both debulk the tumor and stimulate an immune response, potentially priming the tumor for subsequent adjuvant immunotherapy. Further research on optimizing cryoimmunologic response and translating laboratory results to clinical benefit in the treatment of liver cancer is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Yale Liver Center Award (NIH P30 DK034989) Morphology Core for their support with resources and expertise and Boston Scientific and Guerbet for providing materials for this study.

Supported by the Society of Interventional Oncology (grant 19-001324) and National Institutes of Health (grant R01 CA206180).

Data sharing: Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: A.S. Grants from the Heinrich Hertz Foundation, Ministry of Culture and Science of the German State of North Rhine-Westphalia, and Rolf W. Günther Foundation for Radiological Sciences; recipient of the Dr. Constantine Cope Medical Student Award from the Society of Interventional Radiology and Trainee Research Award from the RSNA. J.G.S. No relevant relationships. D.N. Grants from the RSNA, Society of Interventional Oncology, Yale School of Medicine (Fellowship for Medical Student Research), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5T35DK104689-07), and Yale Liver Center (NIH P30 DK034989) Cellular and Molecular Physiology Core and Morphology Core. A.B. No relevant relationships. J.T. No relevant relationships. V.K. No relevant relationships. S.K.M. Patent planned, issued, or pending with Yale University. D.C. No relevant relationships. J.D. Grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01HL121226, R01NS035193, and T32HL098069) and grant to institution from the National Science Foundation; honorarium from Elsevier; patent issued with Yale University and Philips; general chair of the 2023 Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention Conference. S.J.R. No relevant relationships. A.W. No relevant relationships. D.C.M. Consulting fees from Arsenal Medical, Boston Scientific, Embolx, GE HealthCare, Guerbet, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Sirtex, and Siemens Healthineers; patent planned, issued, or pending with Yale School of Medicine; data safety monitoring board member for Sirtex (DOORwaY-90) and advisory board member for CAPS Medical, Microbot Medical, and Quantum Surgical; secretary-treasurer of the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists. J.C. Consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Genentech, Eisai, Bayer, Guerbet, and Philips.

Abbreviations:

- CXCR3

- C-X-C motif chemokine receptor type 3

- FOV

- field of view

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- ICI

- immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IFNγ

- interferon γ

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- TAM

- tumor-associated macrophage

References

- 1. Siegel RL , Miller KD , Wagle NS , Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2023 . CA Cancer J Clin 2023. ; 73 ( 1 ): 17 – 48 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang JD , Hainaut P , Gores GJ , Amadou A , Plymoth A , Roberts LR . A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management . Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019. ; 16 ( 10 ): 589 – 604 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finn RS , Qin S , Ikeda M , et al . Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma . N Engl J Med 2020. ; 382 ( 20 ): 1894 – 1905 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gnjatic S , Bronte V , Brunet LR , et al . Identifying baseline immune-related biomarkers to predict clinical outcome of immunotherapy . J Immunother Cancer 2017. ; 5 ( 1 ): 44 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kelley RK , Sangro B , Harris W , et al . Safety, efficacy, and pharmacodynamics of tremelimumab plus durvalumab for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: randomized expansion of a phase I/II study . J Clin Oncol 2021. ; 39 ( 27 ): 2991 – 3001 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zabransky DJ , Danilova L , Leatherman JM , et al . Profiling of syngeneic mouse HCC tumor models as a framework to understand anti-PD-1 sensitive tumor microenvironments . Hepatology 2023. ; 77 ( 5 ): 1566 – 1579 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Y , Zhao Q , Zhao B , et al . Remodeling tumor-associated neutrophils to enhance dendritic cell-based HCC neoantigen nano-vaccine efficiency . Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022. ; 9 ( 11 ): e2105631 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shi L , Wang J , Ding N , et al . Inflammation induced by incomplete radiofrequency ablation accelerates tumor progression and hinders PD-1 immunotherapy . Nat Commun 2019. ; 10 ( 1 ): 5421 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanania R , Sun HS , Xu K , Pustylnik S , Jeganathan S , Harrison RE . Classically activated macrophages use stable microtubules for matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) secretion . J Biol Chem 2012. ; 287 ( 11 ): 8468 – 8483 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Juric V , O’Sullivan C , Stefanutti E , et al . MMP-9 inhibition promotes anti-tumor immunity through disruption of biochemical and physical barriers to T-cell trafficking to tumors . PLoS One 2018. ; 13 ( 11 ): e0207255 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ding H , Hu H , Tian F , Liang H . A dual immune signature of CD8+ T cells and MMP9 improves the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma . Biosci Rep 2021. ; 41 ( 3 ): BSR20204219 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chow MT , Ozga AJ , Servis RL , et al . Intratumoral activity of the CXCR3 chemokine system is required for the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy . Immunity 2019. ; 50 ( 6 ): 1498 – 1512.e5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. House IG , Savas P , Lai J , et al . Macrophage-derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 are required for antitumor immune responses following immune checkpoint blockade . Clin Cancer Res 2020. ; 26 ( 2 ): 487 – 504 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shigeta K , Matsui A , Kikuchi H , et al . Regorafenib combined with PD1 blockade increases CD8 T-cell infiltration by inducing CXCL10 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma . J Immunother Cancer 2020. ; 8 ( 2 ): e001435 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zeng P , Shen D , Zeng CH , Chang XF , Teng GJ . Emerging opportunities for combining locoregional therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma . Curr Oncol Rep 2020. ; 22 ( 8 ): 76 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shao Q , O’Flanagan S , Lam T , et al . Engineering T cell response to cancer antigens by choice of focal therapeutic conditions . Int J Hyperthermia 2019. ; 36 ( 1 ): 130 – 138 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mauda-Havakuk M , Hawken NM , Owen JW , et al . Comparative analysis of the immune response to RFA and cryoablation in a colon cancer mouse model . Sci Rep 2022. ; 12 ( 1 ): 18229 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yakkala C , Chiang CLL , Kandalaft L , Denys A , Duran R . Cryoablation and immunotherapy: an enthralling synergy to confront the tumors . Front Immunol 2019. ; 10 : 2283 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reig M , Forner A , Rimola J , et al . BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update . J Hepatol 2022. ; 76 ( 3 ): 681 – 693 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waitz R , Solomon SB , Petre EN , et al . Potent induction of tumor immunity by combining tumor cryoablation with anti-CTLA-4 therapy . Cancer Res 2012. ; 72 ( 2 ): 430 – 439 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greten TF , Mauda-Havakuk M , Heinrich B , Korangy F , Wood BJ . Combined locoregional-immunotherapy for liver cancer . J Hepatol 2019. ; 70 ( 5 ): 999 – 1007 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Machlenkin A , Goldberger O , Tirosh B , et al . Combined dendritic cell cryotherapy of tumor induces systemic antimetastatic immunity . Clin Cancer Res 2005. ; 11 ( 13 ): 4955 – 4961 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Duffy AG , Ulahannan SV , Makorova-Rusher O , et al . Tremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma . J Hepatol 2017. ; 66 ( 3 ): 545 – 551 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiang AN , Liu JT , Zhao K , et al . Specific inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase decreases tumor invasiveness after radiofrequency ablation in liver tumor animal model . Front Oncol 2020. ; 10 : 561805 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu YRA , O’Koren EG , Hotten DF , et al . A protocol for the comprehensive flow cytometric analysis of immune cells in normal and inflamed murine non-lymphoid tissues . PLoS One 2016. ; 11 ( 3 ): e0150606 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McArthur HL , Diab A , Page DB , et al . A pilot study of preoperative single-dose ipilimumab and/or cryoablation in women with early-stage breast cancer with comprehensive immune profiling . Clin Cancer Res 2016. ; 22 ( 23 ): 5729 – 5737 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dendy MS , Ludwig JM , Stein SM , Kim HS . Locoregional therapy, immunotherapy and the combination in hepatocellular carcinoma: future directions . Liver Cancer 2019. ; 8 ( 5 ): 326 – 340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shi L , Chen L , Wu C , et al . PD-1 blockade boosts radiofrequency ablation-elicited adaptive immune responses against tumor . Clin Cancer Res 2016. ; 22 ( 5 ): 1173 – 1184 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gazzaniga S , Bravo A , Goldszmid SR , et al . Inflammatory changes after cryosurgery-induced necrosis in human melanoma xenografted in nude mice . J Invest Dermatol 2001. ; 116 ( 5 ): 664 – 671 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu G , Yin L , Ouyang X , Zeng K , Xiao Y , Li Y . M2 macrophages promote HCC cells invasion and migration via miR-149-5p/MMP9 signaling . J Cancer 2020. ; 11 ( 5 ): 1277 – 1287 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Valery M , Cervantes B , Samaha R , et al . Immunotherapy and hepatocellular cancer: where are we now? Cancers (Basel) 2022. ; 14 ( 18 ): 4523 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Udagawa M , Kudo-Saito C , Hasegawa G , et al . Enhancement of immunologic tumor regression by intratumoral administration of dendritic cells in combination with cryoablative tumor pretreatment and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin cell wall skeleton stimulation . Clin Cancer Res 2006. ; 12 ( 24 ): 7465 – 7475 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martin MD , Carter KJ , Jean-Philippe SR , et al . Effect of ablation or inhibition of stromal matrix metalloproteinase-9 on lung metastasis in a breast cancer model is dependent on genetic background . Cancer Res 2008. ; 68 ( 15 ): 6251 – 6259 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marshall DC , Lyman SK , McCauley S , et al . Selective allosteric inhibition of MMP9 is efficacious in preclinical models of ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer . PLoS One 2015. ; 10 ( 5 ): e0127063 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang H . Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a cancer biomarker and MMP-9 biosensors: recent advances . Sensors (Basel) 2018. ; 18 ( 10 ): 3249 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rasmussen HS , McCann PP . Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition as a novel anticancer strategy: a review with special focus on batimastat and marimastat . Pharmacol Ther 1997. ; 75 ( 1 ): 69 – 75 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sledge GW Jr , Qulali M , Goulet R , Bone EA , Fife R . Effect of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor batimastat on breast cancer regrowth and metastasis in athymic mice . J Natl Cancer Inst 1995. ; 87 ( 20 ): 1546 – 1550 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

![Schematic overview of the study design. Approximately 2 million Tib-75 cells suspended in a biologically active matrix material were injected subcapsularily into the liver of 8- to 10-week-old female BALB/c mice to induce hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Mice were randomly divided into four groups 7 days after tumor inoculation. Incomplete cryoablation (iCryo or Cryo) was performed in groups 3 (n = 6) and 4 (n = 6) at day 0 (red diamond). Groups 2 and 4 received intraperitoneal injection of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (n = 6) or a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (n = 6) every 2 days for a total of 7 doses (blue shading). Animals were killed on day 17, and spleen and liver tissues were collected. Flow cytometry was performed on tumor and tumor-adjacent tissue from four different groups: control mice (no treatment), mice treated with the MMP inhibitor (n = 6), mice treated with incomplete cryoablation (n = 6), and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and the MMP inhibitor (n = 6). Histopathologic examination (immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining) was performed on spleen and whole-liver tissue from six different groups: the aforementioned four groups, in addition to phosphate-buffered saline–treated mice (n = 6) and mice treated with incomplete cryoablation and phosphate-buffered saline (n = 6).](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/02e8/10902598/85e5c6ad85ce/radiol.232365.fig1.jpg)