Abstract

First characterized in Trypanosoma brucei, the spliced leader-associated (SLA) RNA gene locus has now been isolated from the kinetoplastids Leishmania tarentolae and Trypanosoma cruzi. In addition to the T. brucei SLA RNA, both L. tarentolae and T. cruzi SLA RNA repeat units also yield RNAs of 75 or 76 nucleotides (nt), 92 or 94 nt, and ∼450 or ∼350 nt, respectively, each with significant sequence identity to transcripts previously described from the T. brucei SLA RNA locus. Cell fractionation studies localize the three additional RNAs to the nucleolus; the presence of box C/D-like elements in two of the transcripts suggests that they are members of a class of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) that guide modification and cleavage of rRNAs. Candidate rRNA-snoRNA interactions can be found for one domain in each of the C/D element-containing RNAs. The putative target site for the 75/76-nt RNA is a highly conserved portion of the small subunit rRNA that contains 2′-O-ribose methylation at a conserved position (Gm1830) in L. tarentolae and in vertebrates. The 92/94-nt RNA has the potential to form base pairs near a conserved methylation site in the large subunit rRNA, which corresponds to position Gm4141 of small rRNA 2 in T. brucei. These data suggest that trypanosomatids do not obey the general 5-bp rule for snoRNA-mediated methylation.

Posttranscriptional modifications to the rRNAs, including endonucleolytic cleavage, 2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridinylation, are mediated by small, nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs). The most abundant snoRNA, U3, has been identified in numerous eukaryotes, including the kinetoplastids (27) and Euglena sp. (23). A requirement for U3 snoRNA in endonucleolytic cleavages of precursor rRNA transcripts has been established in yeast and vertebrate systems (31, 36). Multiple other snoRNAs have been identified that are involved in the 2′-O-ribose methylation and pseudouridinylation of the 18S and 25/28S rRNAs (3, 22, 42, 43), although the precise function of many snoRNAs remains unclear.

Several criteria have been used to identify snoRNAs (24, 36, 50), including the presence of conserved sequence motifs, association with nucleolar proteins (fibrillarin, Gar1p, and Pop1p), complementarity to pre-rRNAs, and localization to the nucleolus. Like other cellular RNAs, snoRNAs are believed to exist as ribonucleoprotein complexes (36, 50) and have been divided into two major classes based on conserved sequence elements and protein associations. The box C/D snoRNAs usually contain box C and box D elements near their 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively; these elements are required for snoRNP interaction with the abundant nucleolar protein, fibrillarin. In vertebrates, box C/D snoRNAs are frequently processed from the introns of protein-encoding mRNAs (54), while in plants and yeasts they may be transcribed polycistronically (32, 50). The other class, the box H/ACA snoRNAs, contains two conserved sequence motifs: box H resides in a hinge region between two stem-loop structures, and the “ACA” trinucleotide motif resides 3 nucleotides (nt) from their 3′ ends (3, 22). Box H/ACA snoRNAs of yeasts associate with the essential Gar1 protein (22). Most members of each class of snoRNAs function in modification of rRNA sequences: box C/D snoRNAs guide 2′-O-ribose methylation, and box H/ACA snoRNAs are involved in pseudouridinylation (21). Box C/D snoRNAs direct modification of rRNAs through stretches of sequence complementarity. The region of base pairing between box C/D snoRNAs and the site of methylation in the rRNA always lies immediately upstream from a D box or a D′ box, which is a slightly degenerate version of the D box (29, 43, 55). A number of other snoRNAs containing box C and D elements (U3, U8, U14, and U22) or box H/ACA elements (for example, U17/E1 [19] and snR30 [42]) do not appear to play roles in rRNA nucleotide modification, but they may be required for pre-rRNA cleavages or have roles in pre-RNA folding and ribosome assembly (50).

A number of small nuclear RNAs have been described in the kinetoplastids: the spliced leader (SL) RNA (12, 30, 38), four U small nuclear RNAs involved in trans splicing (U2, U4, and U6 [39, 51, 52] and U5 [18, 60]), the SL-associated (SLA) RNA (44, 46, 58), the mitochondrial guide RNAs (6, 49), the 7SL RNAs (37), the tRNAs (11, 40), the six large-subunit (LSU) rRNA fragments (15, 28), and the U3 snoRNA (27, 39). The U3 RNA is the only snoRNA identified in this group of organisms.

We have characterized four small RNAs in Leishmania tarentolae and Trypanosoma cruzi that are similar to those originally identified as transcripts of unknown function from the SLA RNA repeat in T. brucei (46). We present evidence that three transcripts fractionate with nucleolar markers. Two of the transcripts are bona fide snoRNAs: the 75/76- and 92/94-nt RNAs contain box C, D, and D′ elements and 10- to 14-bp stretches with complementarity to sites in the small-subunit (SSU) or LSU rRNAs. We show that one nucleotide within each of these blocks is ribose methylated. The positions of methylated nucleotides relative to the D or D′ box in the complementary snoRNA differ from the canonical 5-bp spacing seen in higher eukaryotes; in the two sites described here the methylated ribose is the first in the stretch of complementarity. This suggests that the 5-bp rule that directs rRNA methylation in the higher eukaryotes may not be conserved among the early-diverging kinetoplastids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, sequencing, and computer analyses.

Cosmid clones containing the L. tarentolae SLA locus were selected by hybridization with the oligonucleotide probe TGR10 (Table 1) from a library as described previously (20). PvuII, XbaI, and XhoI fragments of one cosmid were subcloned into pBluescript (Stratagene) for further analysis. DNA sequencing was performed with Sequenase (Amersham), and the sequence was submitted to GenBank (accession number AF016399).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | GenBank accession no. | Position, 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lt75.1 | 5′-TCATC GCGAC TCAAA GTCTG TGAT | AF016399 | 594–571 |

| Lt75.2 | 5′-TCAAA GTCTG TGATG T | AF016399 | 584–569 |

| Lt92 | 5′-CAACG TCCAT CTGCG ACGGC TTTA | AF016399 | 767–744 |

| Lt250.1 | 5′-ACACA GGATA TGCGT AACGG GA | AF016399 | 1138–1117 |

| Lt250.2 | 5′-GCCCA GCATG CGCCG GCAAG | AF016399 | 960–941 |

| LtSLA.1 | 5′-CTCCA GTTTC ATGCA CGGTG CC | AF016399 | 1279–1258 |

| LtSLA.2 | 5′-TGGGT CTTGC GGCAC GCGCA | AF016399 | 1255–1236 |

| LtSLA.4 | 5′-TTCAT GCACG GTGCC TGTGG GTCTT G | AF016399 | 1282–1247 |

| LtSLA.5 | 5′-GCGCA CTACA GTGAG CGCGT | AF016399 | 1240–1221 |

| SLAs1 | 5′-GGAAT TCCGA CGCGC TCACT GTAGT G | AF016399 | 1220–1237 |

| T | |||

| TGR10 | 5′-TCTTG C CTC CAGTT TC | AF016399 | 327–311 |

| G | |||

| LtSLexon | 5′-ACTGA TACTT ATATA GCGTT | X73121 | 125–106 |

| LtSLintron1 | 5′-GTTCC GGAAG TTTCG CATAC | X73121 | 160–141 |

| LtSLintron2 | 5′-CGCTT CCAAA ATCTT GCCGG | X73121 | 187–168 |

| TbU2 | 5′-TATCA GGAGT TACTC TGATA AGAAC A | X04678 | 176–151 |

| LtU3 | 5′-CTTTT CAATT AAGAG GTTGT ACTC | L20948 | 2075–2098 |

| LtU4.2 | 5′-GGATA TAGTA TTGCA CTAGT GAACA AA | X97621 | 386–371 |

| TbU6.2 | 5′-AGCCT TGCGC AGGGA GAGTG CTAA | X13017 | 223–200 |

| 75/SSU | 5′-TTCTC ACTGA CATTG TAGTG | M84225 | 1885–1866 |

| 94/LSU | 5′-TTCGA CAAAC TCCAG AAACC | X14553 | 4027–4008 |

The T. cruzi SLA locus-containing clone (51H20) was selected from filters provided by the T. cruzi genome project cosmid library (26) and analyzed as a XhoI fragment (GenBank accession number AF016400).

Cell culture.

L. tarentolae (UC strain) was grown at 27°C with slow rotation in brain heart infusion medium supplemented with hemin (10 μg/ml), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Procyclic-form T. brucei (IsTat1.1 or strain 427) was grown in BSM (5) or SDM-79 (8) containing 5% fetal bovine serum. Cell lysates of T. cruzi Tulahuèn were a kind gift from Jaime M. Santana, University of Brasilia, Brasilia, Brazil.

DNA and RNA extraction and analysis.

DNA and RNA were isolated with TRIzol reagent (Gibco-BRL) as directed by the manufacturer except that the cell density was increased to approximately five times that recommended by the manufacturer in order to compensate for the smaller cell volume of the kinetoplastids. DNA was isolated with DNAzol (Gibco-BRL) as directed by the manufacturer.

Electrophoresis of DNA and RNA on polyacrylamide and agarose gels and transfer to nylon membranes for hybridization analyses were performed as described previously (47) unless otherwise indicated. Hybridizations with oligonucleotides were performed at 42°C. Wash conditions were 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 39°C unless otherwise specified. The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Primer extension on RNA templates was performed with Superscript reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL) as described earlier (46). 3′-end determination of the SLA RNA was performed with total RNA that had been tailed by poly(A) polymerase (Gibco-BRL) and copied into a cDNA with an oligo(dT) primer and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco-BRL); this was followed by PCR with the sense oligonucleotide SLAs1 (Table 1).

Cell fractionation.

The isolation of cytoplasmic, nucleoplasmic, and nucleolar fractions was adapted from published methods (27, 53). Leishmania cultures were grown to a density of 108 cells/ml, and the cells were harvested after centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline and washed twice. The pellet was then resuspended in 3 volumes of ice-cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]; pepstatin, 1 μg/ml; leupeptin, 0.5 μg/ml; 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and incubated on ice for 10 min. The cell suspension was transferred to a 15-ml glass Dounce homogenizer (Wheaton), Nonidet P-40 was added to a final concentration of 0.2%, and the cells were lysed by repeated strokes with a type A pestle. The extent of lysis was monitored by staining 10 μl of the lysate with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) followed by fluorescence microscopic examination to determine the release of nuclei. The lysate was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, flash frozen in an ethanol-dry ice bath, and stored at −80°C as “cytoplasm.”

The nuclear pellet was suspended in 5 volumes of sucrose buffer (0.25 M sucrose; 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9; 3.3 mM MgCl2; 10 mM KCl; 0.5 mM DTT; pepstatin, 1 μg/ml; leupeptin, 0.5 μg/ml; 0.5 mM phenymethylsulfonyl fluoride) and centrifuged in a swinging bucket rotor at 1,100 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was suspended in 2.5 volumes of sucrose buffer and layered over an equal volume of 0.35 M sucrose buffer (i.e., sucrose buffer adjusted to 0.35 M sucrose) for centrifugation at 1,100 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was suspended in 2.5 volumes of 0.35 M sucrose buffer. One-tenth of the volume was removed, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C as “nuclei.”

The remaining suspension was sonicated on ice to disrupt the nuclear structures by using a Bransonic sonicator with a microtip at setting 3 and with five 10-s pulses followed by 30-s intervals or until the organellar structures were fully destroyed. The sonicate was layered over an equal volume of 0.88 M sucrose buffer and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The upper two-thirds of the volume was removed, aliquoted into small volumes, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C as “nucleoplasm,” and the lower third was stored as “nucleoli” at −80°C.

Protein analysis.

Immunoblotting of the cellular fractions was performed following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of samples from each fraction and electrotransfer to the nitrocellulose membrane (2). Anti-fibrillarin monoclonal antibody P2G3 (the kind gift of M. Christensen, University of Kentucky [14]) was used as the primary antibody and was followed by donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson Laboratories) as the secondary antibody. Antibody reactions were detected with the ECL system (Amersham).

Mapping of 2′-O-methylation sites.

Primer extension reactions on SSU rRNA (L. tarentolae) or LSU rRNA (T. brucei) used total L. tarentolae or T. brucei cellular RNA as substrate and 75/SSU or 92/LSU as primers, respectively. For both species, ribose methylations in the vicinity of snoRNA-rRNA complementarity were detected by the deoxyribonucleotide titration method (35). Oligonucleotides complementary to L. tarentolae SSU rRNA (75/SSU; see Table 1) or T. brucei LSU rRNA (94/LSU) were used as primers. For each primer, four extension reactions were performed with concentrations of each dNTP of 1, 0.2, 0.04, or 0.004 mM. Reactions were carried out in a solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM DTT with 0.5 pmol of 32P-labeled oligonucleotide primer and 5 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase at 43°C. The ribose methylation sites in the vicinity of RNA/SSU rRNA complementarity in L. tarentolae were also mapped by primer extension with radiolabeled primer 75/SSU on partially hydrolyzed RNA, which was generated by alkaline hydrolysis as described previously (55).

RESULTS

The L. tarentolae and T. cruzi SLA RNA genes are tandemly arrayed.

The cloned SLA RNA loci were isolated from cosmid libraries of L. tarentolae and T. cruzi (26). The genomic organization of the L. tarentolae and T. cruzi SLA RNA loci (Fig. 1) was similar to that described for T. brucei (46): the SLA RNA genes were in tandem arrays containing greater than 10 copies of approximately 1.45-kb units in L. tarentolae and 0.85-kb units in T. cruzi (data not shown). Thus, the organization of the SLA RNA gene in tandem arrays appears to be common among the kinetoplastids. The difference in the unit length of the three SLA RNA repeats was almost entirely due to variation in the spacer between the SLA RNA and the 75/76-nt RNA.

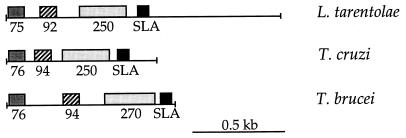

FIG. 1.

The SLA RNA locus organization is conserved in L. tarentolae, T. brucei, and T. cruzi. Repeat units from each species are aligned relative to the 75/76-nt RNA.

Multiple conserved RNAs are transcribed from the SLA RNA locus.

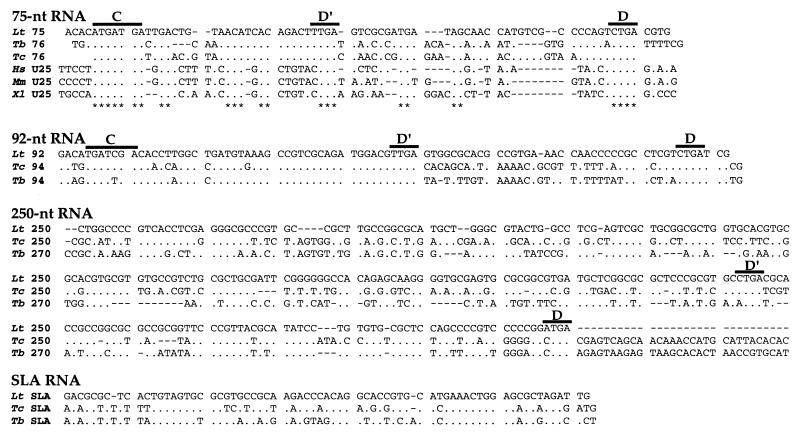

Sequence alignments of the entire SLA RNA repeat units from L. tarentolae, T. cruzi, and T. brucei prepared by using the PILEUP routine revealed an overall sequence similarity of 41% between L. tarentolae and T. brucei. Further alignments between the individual T. brucei SLA RNA repeat transcripts and the entire L. tarentolae and T. cruzi SLA repeat sequences revealed more pronounced similarities (66 to 82% [Fig. 2]) that included short blocks of complete identity. These conserved blocks invariably corresponded to regions within the transcripts mapped in T. brucei (46). The transcripts from the SLA RNA repeats showed no obvious similarity to sequences with known function as determined from the major databases with the BLAST algorithm (1); however, blocks of identity within the 75/76- and 92/94-nt RNAs contained box D motifs, CUGA, which had been described for the box C/D class of snoRNAs in higher eukaryotes (36); sequences with near consensus to the box C were also found (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Conservation of sequence blocks and motifs in the SLA RNA repeat. Shown is a sequence alignment of L. tarentolae (Lt: accession number AF016399) and T. cruzi (Tc: AF016400) repeats with the T. brucei (Tb: Z50171) transcripts. Alignments were generated with the Wisconsin package PILEUP (17) by using a gap weight of 1 and a length weight of 0.6. The 75/76-nt RNAs are aligned with U25 snoRNAs from human (Hs: U40580), mouse (Mm: U40654), and Xenopus sp. (Xl: U72853). Periods denote sequence matches. Gaps introduced into sequences are denoted by dashes. Asterisks indicate positions conserved between phyla in the 75/76-nt RNA alignment. Box C, D, and D′ elements are overlined; no potential box C was obvious within the 250/270-nt RNAs.

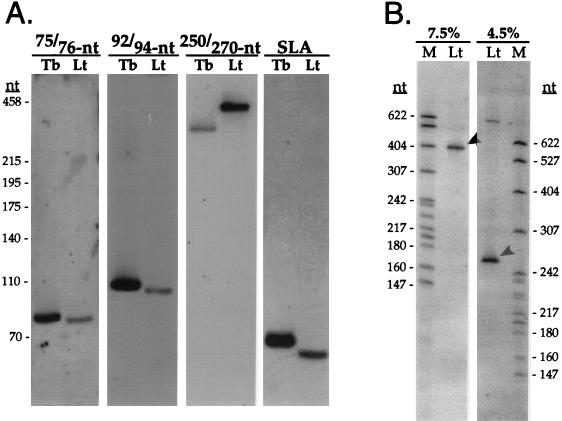

To determine whether the L. tarentolae SLA RNA repeat yielded transcripts homologous to those seen in T. brucei (46), oligonucleotides with complementarity to the core of each of the four regions of interspecies similarity were used to probe total RNA blots from both organisms. At least four small RNAs hybridized to these oligonucleotide probes in both T. brucei and L. tarentolae (Fig. 3A). On 8% polyacrylamide gels the L. tarentolae RNAs have apparent lengths of 75, 92, >400, and 69 nt, the smallest being the SLA RNA. The four L. tarentolae transcripts are located within 750 nt of the repeat and are more tightly clustered than in the T. brucei SLA RNA repeat (Fig. 1).

FIG. 3.

Four stable RNAs from the L. tarentolae SLA RNA repeat. (A) RNA blot analysis of total RNA from T. brucei (lanes Tb) and L. tarentolae (lanes Lt) hybridized with the γ-32P-labeled antisense oligonucleotides Lt75.2, Lt92, Lt250, and LtSLA.1. Sizes are relative to pUC19/HaeIII fragments. (B) Aberrant electrophoretic mobility of the L. tarentolae 250-nt RNA. Total L. tarentolae RNA was separated on 8 M urea and polyacrylamide gels of either 7.5 or 4.5% (denoted at the top of each panel). Lanes: M, pBR322 MspI digest; Lt, L. tarentolae RNA. The position of the 250-nt RNA is denoted by arrowheads.

The L. tarentolae >400-nt transcript migrated through polyacrylamide gels with aberrant mobility, as indicated by a discrepancy between the apparent size of the RNA and the size available for the transcript within the SLA RNA repeat. Direct comparison of the electrophoretic mobilities on 4.5 and 7.5% gels revealed that this RNA migrated as ∼400 nt on 7.5% gels and as 250 nt on 4.5% gels (Fig. 3B), while other RNAs transcribed from this locus migrated consistently with the denatured DNA markers. The effect on relative mobility of modified RNAs (34) appeared to be minimized in gels with lower concentrations of polyacrylamide; therefore, this transcript was subsequently referred to as the 250-nt RNA. The nature of this modification has not been pursued; its biological relevance is uncertain, since the T. brucei counterpart did not show anomolous migration (data not shown). A high-molecular-weight species (>622 nt) in L. tarentolae that appeared in the RNA blot of the 4.5% gel may represent an unprocessed precursor as proposed for T. brucei (46).

The corresponding transcripts were also detected in T. cruzi total RNA (data not shown) and were approximately the same size as in T. brucei (46), except for the 270-nt RNA that migrated at 350 nt in 7.5% gels (see below). The T. cruzi transcripts possessed regions of extensive identity with the corresponding transcripts from T. brucei and L. tarentolae (Fig. 2). The order of the transcript sequences in the repeats was conserved (Fig. 1), and the T. cruzi transcripts were more closely spaced than in either L. tarentolae or T. brucei. The homologous RNAs showed multiple blocks of sequence conservation (Fig. 2). The region upstream of the D′ box was extensively conserved in the 74/75- and 92/94-nt RNAs, whereas the region upstream of the D box was better conserved between the two Trypanosoma species than between either of the Trypanosoma spp. and L. tarentolae.

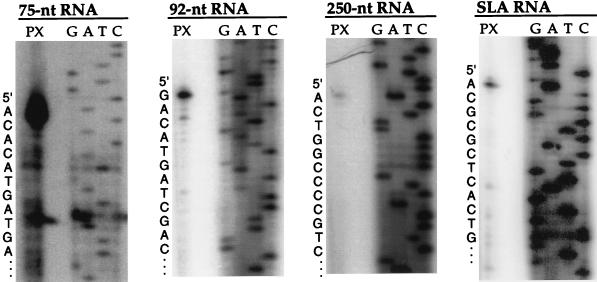

The 5′ end of each L. tarentolae RNA was mapped by primer extension (Fig. 4). The primer extension termination products from all four RNAs mapped to a position similar to that of the corresponding T. brucei transcripts (46). The 3′ end of the L. tarentolae SLA RNA transcript was mapped by using a PCR strategy (see Materials and Methods) to give a precise size of 69 nt (data not shown). Whether these RNAs are primary transcripts or derived from a precursor RNA as suggested by the detection of lower-mobility species remains to be determined.

FIG. 4.

Determination of the 5′ ends of the RNA transcripts from L. tarentolae. Antisense oligonucleotide primers for each RNA (see Table 1; Lt75.2, Lt92, Lt250.2, and LtSLA.1) were used in both primer extensions on total L. tarentolae RNA (PX) and sequencing reactions on the repeat-containing plasmid pLtSLA. The sequence leading up to the primer extension stop position is shown in the left margin of each panel.

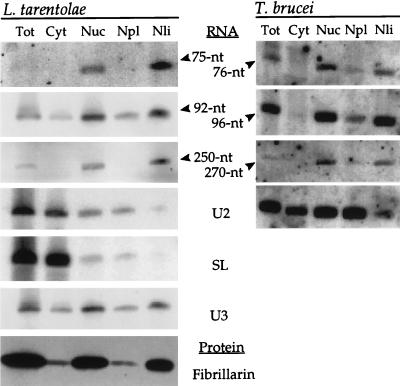

The candidate snoRNAs partition to the nucleolus.

We examined how these small RNAs were distributed in the cytoplasmic, nuclear, nucleoplasmic, and nucleolar compartments of L. tarentolae and T. brucei (Fig. 5). The 75-, 92-, and 250-nt L. tarentolae transcripts and the T. brucei homologs were recovered primarily in the nucleolar fractions, as predicted for snoRNAs. The profiles of the negative controls, U2 and SL RNA (which were predominantly cytoplasmic, although the majority of the nuclear material is nucleoplasmic) (27), and the nucleolar positive controls, U3 snoRNA (27) and the snoRNA-associated protein, fibrillarin (13, 53), were consistent with successful subcellular fractionation.

FIG. 5.

Candidate snoRNAs localize to the nucleolus. The cellular fractions generated for L. tarentolae or T. brucei are abbreviated as follows: Tot, whole cell; Cyt, cytoplasmic; Nuc, nuclear; Npl, nucleoplasmic; and Nli, nucleolar. RNA blots were hybridized with antisense oligonucleotides against RNAs designated in the center margin. Homologous RNAs were hybridized with the same antisense oligonucleotide and are shown in adjacent panels. A protein blot containing L. tarentolae fractions was incubated with the monoclonal antibody P2G3 against Physarum fibrillarin (bottom left panel). Control blots showing nucleoplasmic localization of T. brucei SL RNA and nucleolar localization of U3 and fibrillarin have been published elsewhere (27).

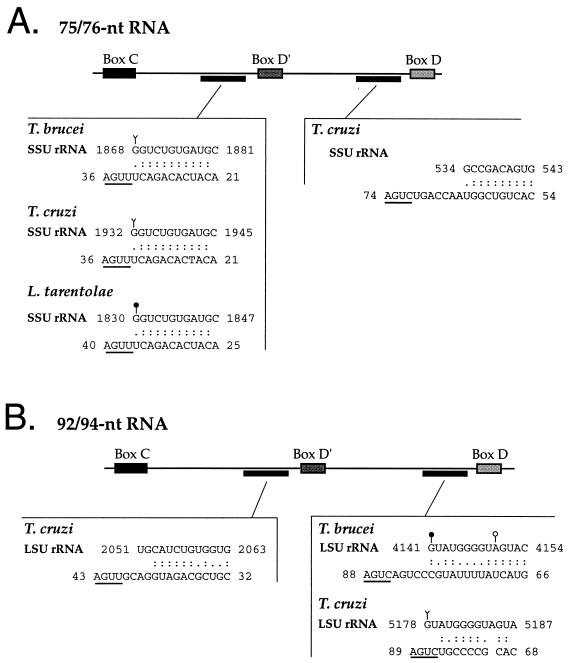

Two of the small RNAs have sequence complementarity with rRNAs.

In higher eukaryotes, the region of snoRNA interaction with the rRNA lies within the 25-nt region upstream of a D or D′ box (29, 43, 55). By using a modified matrix (6), regions of complementarity to the kinetoplastid rRNAs were found for both the 75/76- and 92/94-nt RNAs. Invariably, complementarity fell within the 25 nt upstream of the potential D or D′ boxes in these RNAs (Fig. 6). An 11-nt stretch of complementarity was present upstream of box D′ in the 75/76-nt RNA (Fig. 6A) that corresponded to helix 36′ of the SSU rRNA (16). A region of complementarity (9 to 14 bp) upstream of box D in the 92/94-nt RNA (Fig. 6B) indicated an interaction within domain VI of the LSU rRNA that corresponded to small rRNA 2 in kinetoplastids (10, 59). The sequences of the SSU rRNAs from L. tarentolae, T. brucei, and T. cruzi and those of the LSU rRNAs from T. brucei and T. cruzi were available; thus, a complete analysis could not be made for L. tarentolae. The rRNA sequences in helix 36′ and domain VI are conserved throughout the kinetoplastid, vertebrate, and fungal phyla and are documented sites of 2′-O-ribose methylation in the vertebrates (LSU and SSU) and yeasts (SSU) (34). The vertebrate U25 snoRNAs implicated in the methylation of this SSU rRNA site have been described and are shown in alignment with the 75/76-nt RNA in Fig. 2. These experiments were controlled by using sequences outside of the 25-nt region upstream of boxes D and D′ and throughout the 250/270-nt RNAs and the SLA RNAs in searches for complementarity to rRNA sequences. These searches consistently resulted in less than 10 nt of complementarity (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

The 75/76- and 92/94-nt RNAs are complementary to the SSU and LSU rRNAs. Each candidate snoRNA sequence was compared to the respective SSU and LSU rRNA by using the Wisconsin package BESTFIT (17) and allowing for G-U base pairing with a gap weight of 5 and a length weight of 0.3. Schematics of the 75/76-nt RNA (A) and the 92/94-nt RNA (B) indicate the regions of complementarity with rRNA. For each region of complementarity the rRNA is shown above the reversed partial sequence of the putative snoRNA. Box D and D′ elements are underlined. Standard Watson-Crick base pairs are indicated by colons (:); G-U base pairs are indicated by periods. Filled circles represent 2′-O-methylation sites mapped in this study that are conserved among higher eukaryotes. The open circle represents a nonconserved methylation site in T. brucei. Y represents the equivalent position in kinetoplastid rRNAs of 2′-O-methylation sites conserved among higher eukaryotes (Gm1448 in X. laevis SSU rRNA [33] in panel A and Am3713 in X. laevis and Am4550 in human LSU rRNA [34] in panel B). The accession numbers for the rRNA sequences were as follows: T. brucei SSU, M12676; T. cruzi SSU, M31432; L. tarentolae SSU, M54225; T. brucei LSU, X14553; and T. cruzi LSU, L22334.

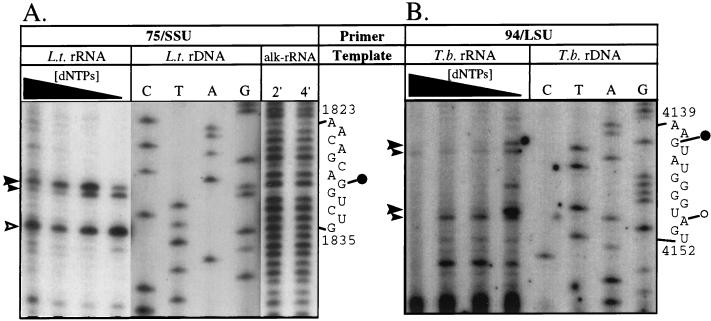

Ribose methylations occur within the regions of complementarity between the kinetoplastid snoRNAs and rRNAs.

The significance of complementarity between the putative snoRNAs and the rRNAs depends on the presence of a ribose methylation on the rRNA in the appropriate regions; therefore, methylation mapping studies were done. 2′-O-Methylations inhibit reverse transcription at low nucleotide concentrations (35), so primer extension reactions were performed from sites 3′ of the complementarity in the SSU and LSU rRNAs with decreasing concentrations of dNTPs (Fig. 7). These reaction mixtures were electrophoresed alongside a sequencing reaction mixture to allow the bases to be assigned. In the case of the 75/76-nt RNA (Fig. 7A), extension reactions on L. tarentolae RNA with the oligonucleotide primer 75/SSU produced two sets of bands. One, a stop (Fig. 7, open arrowhead) at all nucleotide concentrations at position G1835 of the L. tarentolae SSU rRNA (7), is most likely template sequence dependent. The other set was a doublet (solid arrowheads) that is most likely due to a ribose-methylated site because of concentration dependence of the stops (increased abundance at low concentrations of nucleotide). The larger arrowhead denotes the position of the methylated nucleotide G1830. The small arrowhead appears to be “stuttering,” a common outcome of reverse transcription across ribose-methylated nucleotides (35). To determine whether the complete stop at position G1835 was due to a methylation site, a second method of 2′-O-methylation mapping was done. This method takes advantage of the fact that the 2′ modification prevents the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond of RNA under heated alkaline conditions. L. tarentolae RNA was partially hydrolyzed and used as a substrate for primer extensions with the same primer (75/SSU). The extension reaction produced a ladder of stops at each nucleotide, including U1836, but with a strongly diminished stop at G1831, a finding consistent with 2′-O-methylation of G1830 and no ribose methylation at G1835.

FIG. 7.

Regions of complementarity are associated with conserved 2′-O-methylated positions. Primer extension mapping of the ribose methylation sites in the region of complementarity between the L. tarentolae (L.t.) 75-nt RNA and the SSU rRNA (A) and between the T. brucei (T.b.) 94-nt RNA and the LSU rRNA (B) is shown. Primer extension reactions were done with decreasing concentration of dNTPs. Concentration-dependent stops are denoted by filled arrowheads, with the larger arrowhead marking the position of the ribose methylation. An open arrowhead marks a concentration-independent stop. Positions of modified nucleotides are shown by sequencing reactions on rDNA-containing plasmids (pL8, L.t. SSU rRNA [9]; pRB3, T.b. LSU rRNA [10]) primed with the same oligonucleotides used in the primer extension reactions (as labeled at the top of each panel). Positions of ribose methylations in the L. tarentolae SSU rRNA were additionally determined by primer extension of partially hydrolyzed total L. tarentolae RNA (alk-rRNA). RNA was exposed to heated alkaline conditions for 2 min (2′) or 4 min (4′) as labeled. Positions of 2′-O-methylations are indicated by circles to the right of the rRNA sequences; filled circles denote positions that are methylated in the higher eukaryotes (see Fig. 6 for references).

The region of complementarity between the T. brucei LSU rRNA and the 94-nt RNA corresponded to a ribose methylation site conserved in higher eukaryotes (34). Due to the unusual processing of the T. brucei LSU, Gm4141 (Fig. 7B) corresponds to position 40 of srRNA 2 (59). In addition, ribose methylation of Am4150, which is not phylogenetically conserved, was observed in this experiment.

DISCUSSION

Characterization of the SLA RNA locus revealed that the three additional small transcripts were conserved in the kinetoplastids. We present evidence identifying three of these transcripts as snoRNAs. The gene organization is similar in the related kinetoplastids L. tarentolae, T. brucei, and T. cruzi; the SLA RNA genes are tandemly arrayed, with ≥12 copies per haploid genome. The relative order of the four transcripts templated within the SLA RNA repeat is identical: 75/76-, 92/94-, and 250/270-nt and SLA RNA (Fig. 1). The 250/270-nt RNA is a candidate snoRNA based on subcellular localization in L. tarentolae and T. brucei, although conserved elements or structural features that would allow it to be categorized among the known groups of snoRNAs are not apparent. The 75/76- and 92/94-nt RNAs contained box C, D, and D′ motifs and fractionated with nucleolar markers. Consistent with this observation, RNAs of similar size are immunoprecipitated from T. brucei extracts by antifibrillarin antiserum (27). The sequence immediately upstream of the D′ box in the 75/76-nt RNA shows conserved complementarity with SSU rRNA sequences in L. tarentolae, T. brucei, and T. cruzi, which corresponds to a 2′-O-methylation site that is known to also be present in human, mouse (54), and yeast (29) SSU rRNA and in Xenopus sp. (33). In these higher organisms this ribose methylation (equivalent to nucleotide Gm1448 in Xenopus laevis) is guided by the U25 snoRNA (55). Likewise, sequences upstream of the D box in the 92/94-nt RNA appear to interact with the T. brucei LSU rRNA to guide the methylation of the position equivalent to nucleotide Am3717 in the Xenopus LSU rRNA (34). Potential snoRNA-rRNA interactions upstream of box D in the 75/76-nt RNA (Fig. 5A) and upstream of box D′ in the 92/94-nt RNA are predicted only for T. cruzi. The lack of support for homologous interactions in T. brucei and L. tarentolae may be due either to interaction with variable regions of the rRNA or to divergence of functional domains within the snoRNAs. The homologous modifying domains may be coupled with different functional domains in the various trypanosomatids.

The kinetoplastid LSU rRNA is processed through a cleavage pathway analogous to the processing seen in higher eukaryotic rRNAs. It is further cleaved into two large and four small fragments that remain associated in the ribosome (28) and form the same core LSU structure found in higher eukaryotes (48). Methylation of rRNA is also a conserved phenomenon: an estimated 1.4% of the Crithidia fasciculata rRNA is conserved compared to 3.0% of human and 2.1% of yeast rRNA (34). snoRNAs appear to have two functional domains (43); thus, the divergence between the sequences upstream of the D′ and D boxes in the different kinetoplastid species may represent the independence of function in the two halves of each molecule. While many of the 2′-O-methylated positions seen in the rRNAs of higher eukaryotes are conserved among vertebrates and fungi, others are conserved only among vertebrates and still others appear to be specific to particular taxa (34). The populations of snoRNAs may reflect these differences, and a similar variation in methylation patterns among the divergent kinetoplastid species may account for the variation in sequences of these small RNAs.

The rRNA 2′-O-methylations identified in the proposed 75/76- and 92/94-nt RNA interaction sites correspond to sites within the rRNA of vertebrates (34). In vertebrates and yeasts the site of methylation is typically complementary to 5 nt downstream of the D or D′ box; these 5 nt generally have 4 to 5 bp of complementarity with the rRNA. It is notable that the corresponding methylated nucleotides in the kinetoplastids are positioned at the first base pair of complementarity proximal to the D or D′ box and are 1 nt downstream of the D′ box (75/76-nt RNA) or 6 nt downstream of the D box (92/94-nt RNA). Thus, the mechanism of recognition (snoRNA base pairing with rRNA) is probably conserved in all eukaryotes; however, the selection of the specific modification site may follow an altered rule in trypanosomatids. We cannot rule out the possibility that as-yet-unidentified snoRNAs bring about the rRNA modifications we have mapped or that these snoRNAs modify RNA molecules other than rRNA. The definitive assignment of snoRNA function awaits deletion and/or modification of these multicopy genes and rescue with mutated or episomal snoRNAs.

Base and ribose methylations can have a wide range of effects, both stabilizing and destabilizing RNA secondary structure (25, 34). Although individual methylations are generally nonessential for viability or rRNA processing, their importance may be cumulative or synergistic. The role of box C/D snoRNAs in 2′-O-ribose methylation involves base pairing with the target rRNA site, in contrast to bacterial methyltransferase activities, which require only the secondary structure of the rRNA (4, 61). The secondary structure may also be the determining feature for eukaryotic nonnucleolar structural RNAs that are methylated outside of their 7-methyl-G cap structures, as in some snRNAs. These internal methylation sites on small nuclear RNAs are located in regions that are functionally important and postulated to facilitate RNA-RNA interactions within the spliceosome (25). An RNA methyltransferase activity has been identified in trypanosomatids (56), and the elucidation of the enzymatic components will allow comparisons with higher eukaryotes.

The clustering and conserved order of the four transcripts may reflect constraints such as polycistronic transcription (45). The major difference in size among the repeats occurs in the region between the SLA RNA transcript and the 75-nt RNA (725 bp in L. tarentolae, 34 bp in T. brucei, and 115 bp in T. cruzi). This spacing and the presence of the 75-nt RNA as the first transcript in the array (Fig. 1) creates a working model for the order of transcripts within the repeat. In higher eukaryotes the box C/D-containing class of snoRNAs are often processed from the introns of protein-encoding genes in vertebrates (43, 54) or are transcribed polycistronically in some yeast genera and plants (32, 50). Kinetoplastids do not have typical introns in their protein-coding genes; given the precedents of polycistronic transcription of protein-coding genes, divergent transcription of small RNA genes in trypanosomatids (41, 57), and the unusual nature of transcription of snoRNAs in higher eukaryotes, in vivo expression studies will be necessary to determine whether the SLA-repeat RNAs are transcribed individually or they are processed from a common precursor molecule, as suggested by the observation of larger, potential precursor molecules in RNA blots (Fig. 3) and S1 nuclease protection assays (46).

The multicopy, tandemly repeated nature of the trypanosomatid SLA RNA locus-derived snoRNAs may not represent the only arrangement for snoRNAs in this lineage. Identification and analysis of additional snoRNAs will reveal if this is a characteristic feature of the kinetoplastids or whether other snoRNAs can be found in the introns of polycistronic pre-mRNAs, analogous to the vertebrate arrangement. Why does the cell maintain 10 to 12 copies of the genes for these snoRNAs yet only one copy of the U3 snoRNA gene? The linkage of the snoRNAs and the SLA RNA may be indicative of the SLA RNA function; the SLA RNA was identified by psoralen cross-linking to a methylated molecule, the SL RNA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shula Michaeli and Jan Dungan for helpful discussions and Jörg Hoheisel, Jaime M. Santana, Marc Christensen, and Roberto Hernández for providing invaluable reagents and information for this study. We also thank Aparche Yang for contributions to the project.

This work was funded by NIH grants AI34536 to D.A.C., AI21975 to N.A., and AI34093 to T.H. The Microbial Pathogenesis Training Grant, 5-T32-AI-07323, supported trainees N.R.S. and B.K.Y.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Meyers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology, suppl. 19. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balakin A G, Smith L, Fournier M J. The RNA world of the nucleolus: two major families of small RNAs defined by different box elements with related functions. Cell. 1996;86:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bechthold A, Floss H G. Overexpression of the thiostrepton-resistance gene from Streptomyces azureus in Escherichia coli and characterization of recognition sites of the 23S rRNA A1067 2′-methyltransferase in the guanosine triphosphatase center of 23S ribosomal RNA. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bienen E J, Hammadi E, Hill G C. Trypanosoma brucei: biochemical and morphological changes during in vitro transformation of bloodstream- to procyclic-trypomastigotes. Exp Parasitol. 1981;51:408–417. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(81)90128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum B, Bakalara N, Simpson L. A model for RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria: “guide” RNA molecules transcribed from maxicircle DNA provide the edited information. Cell. 1990;60:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90735-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briones M R, Nelson K, Beverley S M, Affonso H T, Camargo E P, Floeter-Winter L M. Leishmania tarentolae taxonomic relatedness inferred from phylogenetic analysis of the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;53:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90014-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brun R, Schönenberger M. Cultivation and in vitro cloning or procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei in a semi-defined medium. Acta Trop. 1979;36:289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell, D. A. Unpublished data.

- 10.Campbell D A, Kubo K, Clark C G, Boothroyd J C. Precise identification of cleavage sites involved in the unusual processing of trypanosome ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:113–124. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell D A, Suyama Y, Simpson L. Genomic organisation of nuclear tRNAGly and tRNALeu genes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;37:257–262. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell D A, Thornton D A, Boothroyd J C. Apparent discontinuous transcription of Trypanosoma brucei variant surface antigen genes. Nature. 1984;311:350–355. doi: 10.1038/311350a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappai R, Osborn A H, Handman E. Cloning and sequence of a Leishmania major homologue to the fibrillarin gene. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;64:353–355. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen M E, Moloo J, Swischuk J L, Schelling M E. Characterization of the nucleolar protein, B-36, using monoclonal antibodies. Exp Cell Res. 1986;166:77–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordingley J S, Turner M J. 6.5S RNA: preliminary characterisation of unusual small RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1980;1:91–96. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(80)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dams, E., L. Hendriks, Y. Van de Peer, J. M. Neefs, G. Smits, I. Vandenbempt, and R. De Wachter. 1988. Compilation of small ribosomal subunit RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 16(Suppl.):87–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dungan J M, Watkins K P, Agabian N. Evidence for the presence of a small U5-like RNA in active trans-spliceosomes of Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 1996;15:4016–4029. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enright C A, Maxwell E S, Sollner-Webb B. 5′ETS rRNA processing facilitated by four small RNAs: U14, E3, U17, and U3. RNA. 1996;2:1094–1099. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleischmann J, Campbell D A. Expression of the Leishmania tarentolae ubiquitin-encoding and mini-exon genes. Gene. 1994;144:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganot P, Bortolin M L, Kiss T. Site-specific pseudouridine formation in preribosomal RNA is guided by small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1997;89:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganot P, Caizergues F M, Kiss T. The family of box ACA small nucleolar RNAs is defined by an evolutionarily conserved secondary structure and ubiquitous sequence elements essential for RNA accumulation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:941–956. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray M W. The ribosomal RNA of the trypanosomatid protozoan Crithidia fasciculata: physical characteristics and methylated sequences. Can J Biochem. 1979;57:914–926. doi: 10.1139/o79-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenwood S J, Schnare M N, Gray M W. Molecular characterization of U3 small nucleolar RNA from the early diverging protist, Euglena gracilis. Curr Genet. 1996;30:338–346. doi: 10.1007/s002940050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu J, Patton J R, Shimba S, Reddy R. Localization of modified nucleotides in Schizosaccharomyces pombe spliceosomal small nuclear RNAs: modified nucleotides are clustered in functionally important regions. RNA. 1996;2:909–918. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanke J, Sanchez D O, Henriksson J, Aslund L, Pettersson U, Frasch A C, Hoheisel J D. Mapping the Trypanosoma cruzi genome: analyses of representative cosmid libraries. BioTechniques. 1996;21:686–688. doi: 10.2144/96214rr01. , 690–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartshorne T, Agabian N. RNA B is the major nucleolar trimethylguanosine-capped small nuclear RNA associated with fibrillarin and pre-rRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:144–154. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasan G, Turner M J, Cordingley J S. Ribosomal RNA genes of Trypanosoma brucei: mapping the regions specifying the six small ribosomal RNAs. Gene. 1984;27:75–86. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiss-László Z, Henry Y, Bachellerie J P, Caizergues F M, Kiss T. Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1996;85:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kooter J M, De L T, Borst P. Discontinuous synthesis of mRNA in trypanosomes. EMBO J. 1984;3:2387–2392. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lafontaine D, Tollervey D. Trans-acting factors in yeast pre-rRNA and pre-snoRNA processing. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:803–812. doi: 10.1139/o95-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leader D J, Sanders J F, Waugh R, Shaw P, Brown J W. Molecular characterisation of plant U14 small nucleolar RNA genes: closely linked genes are transcribed as polycistronic U14 transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5196–5203. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.24.5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maden B E. Identification of the locations of the methyl groups in 18S ribosomal RNA from Xenopus laevis and man. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:681–699. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maden B E. The numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990;39:241–303. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maden B E, Corbett M E, Heeney P A, Pugh K, Ajuh P M. Classical and novel approaches to the detection and localization of the numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Biochimie. 1995;77:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)88100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell E S, Fournier M J. The small nucleolar RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:897–934. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.004341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michaeli S, Podell D, Agabian N, Ullu E. The 7SL RNA homologue of Trypanosoma brucei is closely related to mammalian 7SL RNA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;51:55–64. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milhausen M, Nelson R G, Sather S, Selkirk M, Agabian N. Identification of a small RNA containing the trypanosome spliced leader: a donor of shared 5′ sequences of trypanosomatid mRNAs? Cell. 1984;38:721–729. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mottram J, Perry K L, Lizardi P M, Luhrmann R, Agabian N, Nelson R G. Isolation and sequence of four small nuclear U RNA genes of Trypanosoma brucei subsp. brucei: identification of the U2, U4, and U6 RNA analogs. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1212–1223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mottram J C, Shafi Y, Barry J D. Sequence of a tRNA gene cluster in Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3995. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.14.3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakaar V, Dare A O, Hong D, Ullu E, Tschudi C. Upstream tRNA genes are essential for expression of small nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA genes in trypanosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6736–6742. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni J, Tien A L, Fournier M J. Small nucleolar RNAs direct site-specific synthesis of pseudouridine in ribosomal RNA. Cell. 1997;89:565–573. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicoloso M, Qu L H, Michot B, Bachellerie J P. Intron-encoded, antisense small nucleolar RNAs: the characterization of nine novel species points to their direct role as guides for the 2′-O-ribose methylation of rRNAs. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:178–195. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palfi Z, Xu G L, Bindereif A. Spliced leader-associated RNA of trypanosomes: sequence conservation and association with protein components common to trans-spliceosomal ribonucleoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30620–30625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pays E, Vanhamme L, Berberof M. Genetic controls for the expression of surface antigens in African trypanosomes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:25–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts T G, Dungan J M, Watkins K P, Agabian N. The SLA RNA gene of Trypanosoma brucei is organized in a tandem array which encodes several small RNAs. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;83:163–174. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito R M, Elgort M G, Campbell D A. A conserved upstream element is essential for transcription of the Leishmania tarentolae mini-exon gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:5460–5469. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schnare M N, Damberger S H, Gray M W, Gutell R R. Comprehensive comparison of structural characteristics in eukaryotic cytoplasmic large subunit (23S-like) ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:701–719. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sturm N R, Simpson L. Kinetoplast DNA minicircles encode guide RNAs for editing of cytochrome oxidase subunit III mRNA. Cell. 1990;61:879–884. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90198-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tollervey D, Kiss T. Function and synthesis of small nucleolar RNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:337–342. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tschudi C, Krainer A R, Ullu E. The U6 small nuclear RNA from Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:11375. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.23.11375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tschudi C, Richards F F, Ullu E. The U2 RNA analogue of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense: implications for a splicing mechanism in trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:8893–8903. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.22.8893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyc K, Steitz J A. U3, U8, and U13 comprise a new class of mammalian snRNPs localized in the cell nucleolus. EMBO J. 1989;8:3113–3119. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tycowski K T, Shu M D, Steitz J A. A mammalian gene with introns instead of exons generating stable RNA products. Nature. 1996;379:464–466. doi: 10.1038/379464a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tycowski K T, Smith C M, Shu M D, Steitz J A. A small nucleolar RNA requirement for site-specific ribose methylation of rRNA in Xenopus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14480–14485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ullu E, Tschudi C. Accurate modification of the trypanosome spliced leader cap structure in a homologous cell-free system. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20365–20369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vanhamme L, Pays E. Control of gene expression in trypanosomes. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:223–240. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.223-240.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Watkins K P, Dungan J M, Agabian N. Identification of a small RNA that interacts with the 5′ splice site of the Trypanosoma brucei spliced leader RNA in vivo. Cell. 1994;T6:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.White T C, Rudenko G, Borst P. Three small RNAs within the 10 kb trypanosome rRNA transcription unit are analogous to domain VII of other eukaryotic 28S rRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:9471–9489. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.23.9471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu Y, Ben-Shlomo H, Michaeli S. The U5 RNA of trypanosomes deviates from the canonical U5 RNA: the Leptomonas collosoma U5 RNA and its coding gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8473–8478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhong P, Pratt S D, Edalji R P, Walter K A, Holzman T F, Shivakumar A G, Katz L. Substrate requirements for ErmC′ methyltransferase activity. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4327–4332. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4327-4332.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]