Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated an uptick in poor mental health outcomes, including Coronavirus-related anxiety and distress. Preliminary research has shown that intolerance of uncertainty (IU) and worry proneness, two transdiagnostic risk factors for anxiety and related disorders, are associated cross-sectionally with pandemic-related fear and distress. However, the extent to which IU and worry proneness prospectively predict Coronavirus-related anxiety and distress is unclear. Whether IU and worry may also interact in prospectively predicting Coronavirus-related anxiety and distress is also unknown. To address this knowledge gap, the present study examined IU and trait worry as prospective predictors of the level and trajectory of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome over time, as well as the extent to which worry moderated the relation between IU and pandemic-related outcomes. Participants (n=310) who completed self-report measures of IU and trait worry in 2016 were contacted following the onset of COVID-19 in 2020 and completed biweekly measures of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome for 30 weeks. Multilevel models revealed that IU assessed in 2016 significantly predicted the severity of both Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome throughout the study period in 2020. Worry also moderated the link between IU and Coronavirus anxiety, such that individuals with high levels of trait worry and high IU in 2016 experienced the most Coronavirus anxiety in 2020. Results suggest that IU and worry functioned as independent and interactive vulnerability factors for subsequent adverse psychological reactions to COVID-19. Clinical implications and future directions are discussed.

Keywords: intolerance of uncertainty, worry, anxiety, stress, coronavirus

In January of 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported the first cases of a severe pneumonia in Wuhan, China. The disease’s etiology, course, and mode of transmission were yet unknown. Eventually, a novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) was identified. Cases began spreading outside of China beginning in January of 2020, and by March of 2020, the WHO declared the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) to be a pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020). What ensued constituted a multifaceted, enduring stressor affecting the global population: rampant disease spread, high mortality rates, government-mandated lockdowns, social distancing and quarantine measures, and disruption to the global economy perturbed people’s lives in meaningful, unforeseen ways (da Silva et al., 2021; Dubey et al., 2020). Accordingly, the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated an uptick in poor mental health outcomes, particularly those related to anxiety. Significant increases in panic, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, and post-traumatic stress symptoms following the onset of the pandemic have been documented globally (Dubey et al., 2020). Almost one third (29%) of the general population in China endorsed moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (C. Wang et al., 2020), and almost half (46%) of the general global population endorsed an increase in anxiety following the pandemic’s onset (da Silva et al., 2021). What’s more, new psychological conditions emerged representing maladaptive responses to the pandemic, including anxiety specifically triggered by COVID-19 (Lee, 2020) and pandemic-related adjustment disorders (Taylor, 2021).

Given the increased prevalence and severity of mental health problems resulting from the pandemic, there is interest in identifying vulnerability factors that predict adverse psychological reactions to COVID-19. Pinpointing vulnerability factors has important implications for informing targeted interventions and public health messaging to improve outcomes of individuals suffering from adverse psychological reactions to the pandemic. One potential vulnerability factor is intolerance of uncertainty (IU). IU is a dispositional tendency to react negatively to uncertain or ambiguous states, and it is thought to be rooted in the belief that uncertain or new things are potentially dangerous (Dugas et al., 1998; Gentes & Ruscio, 2011). This perception of uncertainty as threatening predisposes individuals high in IU towards anxiety responses in the face of ambiguity (Carleton, 2012). As such, IU is a robust, transdiagnostic risk factor for anxiety and related disorders (Carleton, 2012; Gentes & Ruscio, 2011).

Since COVID-19 was ripe with uncertainty and ambiguity (e.g., about the etiology and course of the virus, duration of lockdowns, economic consequences, etc.), IU may similarly function as a vulnerability factor for anxious responding to the pandemic. Consistent with this view, cross-sectional data demonstrate that IU significantly predicted coronavirus fear (Millroth & Frey, 2021; Wheaton et al., 2021), psychological distress (Reizer et al., 2021), and state anxiety during the pandemic (Mallett et al., 2021). Furthermore, IU during earlier stages of the pandemic has been shown to prospectively predict subsequent Coronavirus anxiety and safety behavior use (Jessup et al., 2022), changes in anxiety sensitivity and health anxiety (Bredemeier et al., 2023), and symptoms of COVID-related distress (Taylor et al., 2021). Although the extant literature supports a link between IU during the pandemic and anxiety-related outcomes, most existing studies were cross-sectional in nature, and/or measured IU during the COVID-19 pandemic when uncertainty was heightened. Accordingly, it remains unclear whether pre-pandemic IU confers risk for anxiety-related outcomes following the onset of COVID-19. Further, prior prospective research on the effects of IU is limited by assessing anxiety-related outcomes at only one or two time points, compromising our ability to examine trends in anxiety levels over time (Bredemeier et al., 2023; Jessup et al., 2022).

Another important consideration is that the extent to which IU may contribute to pandemic-related anxiety may be partially contingent on the regulatory strategies one is prone to employ. Prior research suggests that individuals high in IU who experience uncertain scenarios as aversive often recruit worry (a form of repetitive, future-oriented negative thinking) as a means to resolve ambiguity and its associated distress (Buhr & Dugas, 2002; Freeston et al., 1994; Meyer et al., 1990). This use of worry is thought to negatively reinforce the avoidance of negative internal states, thus preventing healthy processing and regulation of emotions (McLaughlin et al., 2007). In the context of COVID-19, excessive worry among those high in IU may function to increase risk for anxiety-related outcomes. Prior research on the interaction between worry and IU supports this hypothesized moderation effect. In a cross-sectional study of a mixed clinical sample, Dar et al. (2017) found that worry moderated the effect of IU on symptoms of anxiety and depression, such that higher levels of trait worry corresponded to a stronger relationship between IU and symptom severity. Similarly, worry was found to moderate the relationship between IU and post-traumatic stress symptoms, such that the combination of high IU and high worry corresponded to more severe symptoms (Bardeen et al., 2013). Although these results suggest that the combined effect of IU and worry may confer specific, elevated risk for anxiety-related outcomes, no prior research has examined the interaction between these two traits in predicting anxious responding to COVID-19 over time. Worry may also be an independent predictor of maladaptive responses to COVID-19, given its pathogenic effects on anxious activation (Newman et al., 2019) and its established relationship with anxiety, stress, and depression (Olatunji et al., 2010). Indeed, prior studies have found that worry predicted symptoms of anxiety during the pandemic in samples of health care workers (Yıldırım & Özaslan, 2022) and students (Belen, 2021). However, whether trait worry was a prospective predictor of poor mental health outcomes during COVID-19 remains unknown.

The unique and interactive effects of IU and worry may be especially relevant in predicting Coronavirus anxiety. Coronavirus anxiety may be conceptualized as consisting primarily of affective (e.g., fear) and physiological/somatic (e.g., nausea, insomnia, appetite disturbance) symptoms of anxiety specifically experienced in response to Coronavirus-related stimuli or thoughts. For some, these symptoms reached clinically significant levels of severity and contributed to functional impairment (Lee, 2020; Lee et al., 2020). However, the psychological sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic have also been hypothesized to be much broader than these “pure” anxiety symptoms. “Covid Stress Syndrome” describes a state of excessive anxious-distress in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that consists of intercorrelated symptoms across five dimensions: (1) fears of danger and contamination (e.g., concerns about the consequences of infection), (2) fears about economic consequences (e.g., anxiety about the risk of layoffs), (3) xenophobia (e.g., fears about foreigners spreading COVID-19), (4) compulsive checking and reassurance seeking (e.g., frequent symptom monitoring), and (5) traumatic stress (e.g., re-experiencing traumatic COVID-19 experiences) (Taylor et al., 2020b, 2020a). In 2020, 16% of American and Canadian adults fell within the severe range of Covid Stress Syndrome, suggesting clinically significant levels of distress that necessitated psychological intervention (Taylor et al., 2020a). It is unclear, however, the extent to which the unique and interactive effects of IU and worry confer risk for Coronavirus anxiety specifically and/or a broader Covid Stress Syndrome following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding risk factors for these psychological conditions is of particular importance given their novelty, as well as their potential applicability to future pandemics or similar widespread, chronic, multifaceted stressors.

The present study addresses important gaps in the literature by examining if pre-pandemic differences in IU and trait worry prospectively predict the overall level and trajectory of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome over time. Indeed, previous research examining the relationship between IU, worry, and anxious responding during the COVID-19 pandemic is limited by measuring associations concurrently rather than longitudinally. While prior research suggests that IU and worry are each associated with poor psychological outcomes during the pandemic, it is unknown if pre-pandemic IU and trait worry prospectively predict anxious and distressed responses to COVID-19. Not only is it important to consider predictors of the overall severity of COVID-related anxiety and distress, but also of their trajectories over time. Evidence suggests that the severity of Covid Stress Syndrome and COVID-related fear, on average, decreased throughout the course of the pandemic (Asmundson et al., 2022; Bendau et al., 2021). However, if and how individual differences in IU and trait worry affected this overall adaptive trajectory is unknown. Finally, while IU and worry have each been shown to individually predict poor mental health outcomes during COVID-19, the interaction between these two mechanisms in the context of the pandemic has yet to be examined. In the present study, participants were assessed for levels of IU and trait worry in 2016, and then followed biweekly for 30 weeks in 2020 to assess for trajectories of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome. It was predicted that IU and worry would uniquely predict higher overall levels of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome. While prior research has shown a decrease in Covid-related fear and anxiety over time (Asmundson et al., 2022; Bendau et al., 2021), it was predicted that higher IU and worry would predict either an elevated and stable trajectory or an increasing linear trajectory of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome. It was also predicted that worry would moderate the relationship between IU and higher overall levels of Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome.

Material and Methods

Participants

The sample (n=310) consisted of adults in the United States who completed a 2016 survey study and were re-contacted in May of 2020 to participate in the present study. In the original 2016 study, participants were unselected community adults who completed four waves of monthly online questionnaires on insomnia and anxiety-related constructs. 1612 participants completed the study in 2016, and 310 participants completed both the 2016 and 2020 waves of data collection. The mean age of participants was 44.29 years (SD = 13.38) and ranged from 19 to 65 years. Most participants were female (n = 273, 88.24%) and the racial and ethnic composition was as follows: 90.16% White (n = 275), 2.30% Black/African American (n = 7), 1.97% Asian (n = 6), 3.93% Hispanic (n = 12), and 1.64% other (n = 5).

Measures

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Short (IUS-S; Carleton et al., 2007).

The IUS-S is a 12-item self-report measure of IU. Items are rated on a five-point Likert-style scale. Composite scores range from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater intolerance of uncertainty. The IUS-S has been shown to have good construct validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability (Carleton et al., 2007). Internal consistency in the sample was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = .91).

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al., 1990).

The PSWQ is a self-report measure of trait worry, or the general tendency to engage in excessive or uncontrollable worry. 16 items are rated on a five-point Likert-style scale. Scores range from 16 to 80, with higher scores indicating higher propensity towards maladaptive worry. The PSWQ has been demonstrated to have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity (Meyer et al., 1990). Internal consistency of the PSWQ in the current sample was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = .95).

Covid Stress Scales (CSS; Taylor et al., 2020b).

The CSS is a self-report measure of “Covid Stress Syndrome,” or a set of co-occurring anxious-distressed symptoms in response to the COVID-19 pandemic across five dimensions: danger and contamination fears, fears of socioeconomic consequences, xenophobia, traumatic stress symptoms, and compulsive checking and reassurance-seeking. The CSS is made up of 36 items that are rated on a five-point Likert scale. Composite scores range from 0 to 144 and reflect the broader Covid Stress Syndrome. The CSS has demonstrated strong reliability and validity in samples across various cultures and translations (e.g., Khosravani et al., 2021; Mahamid et al., 2022; Milic et al., 2021; Noe-Grijalva et al., 2022; Taylor et al., 2020b). The reliability of the CSS at the first wave of follow-up data collection was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = .95).

Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS; Lee, 2020).

The CAS is a five-item self-report measure of Coronavirus anxiety, or symptoms of anxiety specifically related to the COVID-19 pandemic. CAS scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. The CAS has high demonstrated validity and internal consistency (Lee, 2020). In the present sample, reliability of the CAS at the first wave of follow-up data collection was very good (Cronbach’s alpha= .87).

Procedure

Participants were recruited in 2016 through ResearchMatch, a U.S. National Institute of Health-backed registry of volunteers who have consented to be contacted for participation in health-related research studies. In the baseline wave of data collection, participants completed the IUS, PSWQ, and a demographic questionnaire. Participants were re-contacted on May 27, 2020 to participate in the present longitudinal study. Every two weeks for a total of 30 weeks (constituting 16 follow-up time points through December 2020), participants were emailed a link to complete the CSS and CAS. Data were collected remotely via REDCap, a secure, web-based application for research study data collection (Harris et al., 2009). Surveys remained open for eleven days at each time point. Participants received a reminder email if they had not completed the surveys within one day. At each time point, participants were compensated via a $25 gift card drawing. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved all study procedures

Data analytic strategy

Our first aim was to test whether pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty and worry predicted the level and trajectory of Covid Stress Syndrome over time. To accomplish this aim, we used multi-level modeling with time (i.e., days since the first wave of 2020 data collection) nested within person. The model included time as a level one predictor, and baseline IUS, PSWQ, and the IUS × PSWQ interaction as level two predictors. As shown in the equations below, we tested the within-person main effect of time, and the between-person effects of IUS, PSWQ, and the IUS × PSWQ interaction:

Level 1:

Level 2: .

In the equations, γ01 represents the main effect of IUS, γ02 represents the main effect of PSWQ, γ03 represents the IUS × PSWQ interaction, γ10 represents the main effect of time, γ11 represents the IUS × time interaction, and γ12 represents the PSWQ × time interaction.

Our second aim was to test whether pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty and worry predicted the level and trajectory of Coronavirus anxiety over time. We repeated the same multilevel model but with CAS scores as the level one dependent variable:

Level 1:

Level 2: .

In all analyses, when interactions were nonsignificant, we eliminated the interaction term, re-ran the model, and examined the main effects. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 28.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Participants completed between 2 and 17 waves of data collection, with an average of 10.47 timepoints (mode = 17, SD = 5.61). We included participants with partial data in the primary analyses using full information maximum likelihood estimation. Missingness was not significantly associated with any study variable (ps ≥ .28). At the first wave of COVID-19 data collection in May of 2020, 38.11% (n = 117) of the sample was working from home, and 3.26% (n = 10) reported testing positive for COVID-19.

Summary statistics for all study measures are presented in Table 1. Correlations among the IUS, PSWQ, CSS (at wave 1 in 2020), and CAS (at wave 1 in 2020) all were positive and significant (ps < .01). Of note, there were small-sized associations between pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty (IUS) and Covid Stress Syndrome (CSS), r(237) = .29, p < .001, as well as between pre-pandemic worry (PSWQ) and Covid Stress Syndrome (CSS), r(257) = .25, p < .001. There were also small-sized associations between pre-pandemic IU (IUS) and Coronavirus anxiety (CAS), r(244) = .23, p < .001, as well as between pre-pandemic worry (PSWQ) and Coronavirus anxiety (CAS), r(264) = .17, p = .005. Pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty (IUS) and worry (PSWQ) were moderately correlated with each other, r(308) = .53,p < .001.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | IUS | PSWQ | CSS | CAS | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUS-S | 1.00 | 31.19 | 9.38 | |||

| PSWQ | .53** | 1.00 | 50.27 | 15.44 | ||

| CSS | .29** | .25** | 1.00 | 24.92 | 17.29 | |

| CAS | .23** | .17* | .57** | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.81 |

Note: IUS-S = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Short, PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire, CSS = Covid Stress Scales, CAS = Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Correlations reflect IUS and PSWQ in 2016, and CSS and CAS scores at wave 1 of 2020 data collection.

p < .001,

p < .01

Trajectory of Covid Stress Syndrome

We examined the level and trajectory of Covid Stress Syndrome as a function of pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty and trait worry. We used unstructured covariance for the random effects, and a scale identity covariance structure for the repeated effects. We first tested a model including all hypothesized main effects and interactions (i.e., time, IUS, PSWQ, IUS × time, PSWQ × time, and IUS × PSWQ). No interactions were significant, so we re-ran the model including only main effects. Results of the main effects multi-level model appear in Table 2. As hypothesized, both IUS and PSWQ were significant between-person predictors of CSS. The main effect of IUS showed that individuals with higher levels of IU in 2016 reported higher severity of Covid Stress Syndrome on average throughout the study in 2020 (see γ01, p = .001). The main effect of PSWQ showed that individuals with higher levels of trait worry in 2016 also reported higher severity of Covid Stress Syndrome on average throughout the study (see γ02, p = .001). The main effect of time was non-significant (p = .743), indicating that there was no clear linear trend of increasing or decreasing Covid Stress Syndrome over the 30 weeks of follow-up data collection.

Table 2.

Multi-level Model Results for Trajectory of Covid Stress Syndrome (CSS) as a Function of Pre-pandemic Intolerance of Uncertainty and Trait Worry

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept: γ00 | 26.895 | 0.981 | 294.65 | 27.42 | <.001 |

| Time: γ10 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 202.76 | −0.33 | .743 |

| IUS-S: γ01 | 0.396 | 0.120 | 295.96 | 3.29 | .001 |

| PSWQ: γ02 | 0.209 | 0.073 | 298.14 | 2.87 | .004 |

Note: CSS = Covid Stress Scales, IUS-S = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Short, PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire.

Trajectory of Coronavirus Anxiety

We next examined the level and trajectory of Coronavirus anxiety as a function of pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty and trait worry. The same model parameters were used as in the previous analysis. Results of the multi-level model appear in Table 3. The negative main effect of time indicated that CAS scores decreased slightly for all participants throughout the course of the study (see γ10, p < .001). The main effect of IUS showed that individuals with higher levels of pre-pandemic IU reported more severe Coronavirus anxiety on average throughout the study in 2020 (see γ01, p = .005). Unlike when predicting Covid Stress Syndrome, the main effect of PSWQ only reached marginal significance in predicting CAS (see γ02, p = .058). This suggested that when accounting for the effect of IU, trait worry only marginally predicted Coronavirus anxiety.

Table 3.

Multi-level Model Results for Trajectory of Coronavirus Anxiety (CAS) as a Function of Pre-pandemic Intolerance of Uncertainty and Trait Worry

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept: γ00 | 0.891 | 0.132 | 295.11 | 6.75 | <.001 |

| Time: γ10 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 203.89 | −3.34 | <.001 |

| IUS-S: γ01I | 0.042 | 0.015 | 274.29 | 2.80 | .005 |

| PSWQ: γ02 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 273.54 | 1.90 | .058 |

| IUS-S × PSWQ: γ03 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 259.35 | 2.03 | .044 |

| IUS-S × Time: γ11 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 194.52 | −0.72 | .476 |

| PSWQ × Time: γ12 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 203.77 | −0.58 | .565 |

Note: CAS = Coronavirus Anxiety Scale, IUS-S = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Short, PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire.

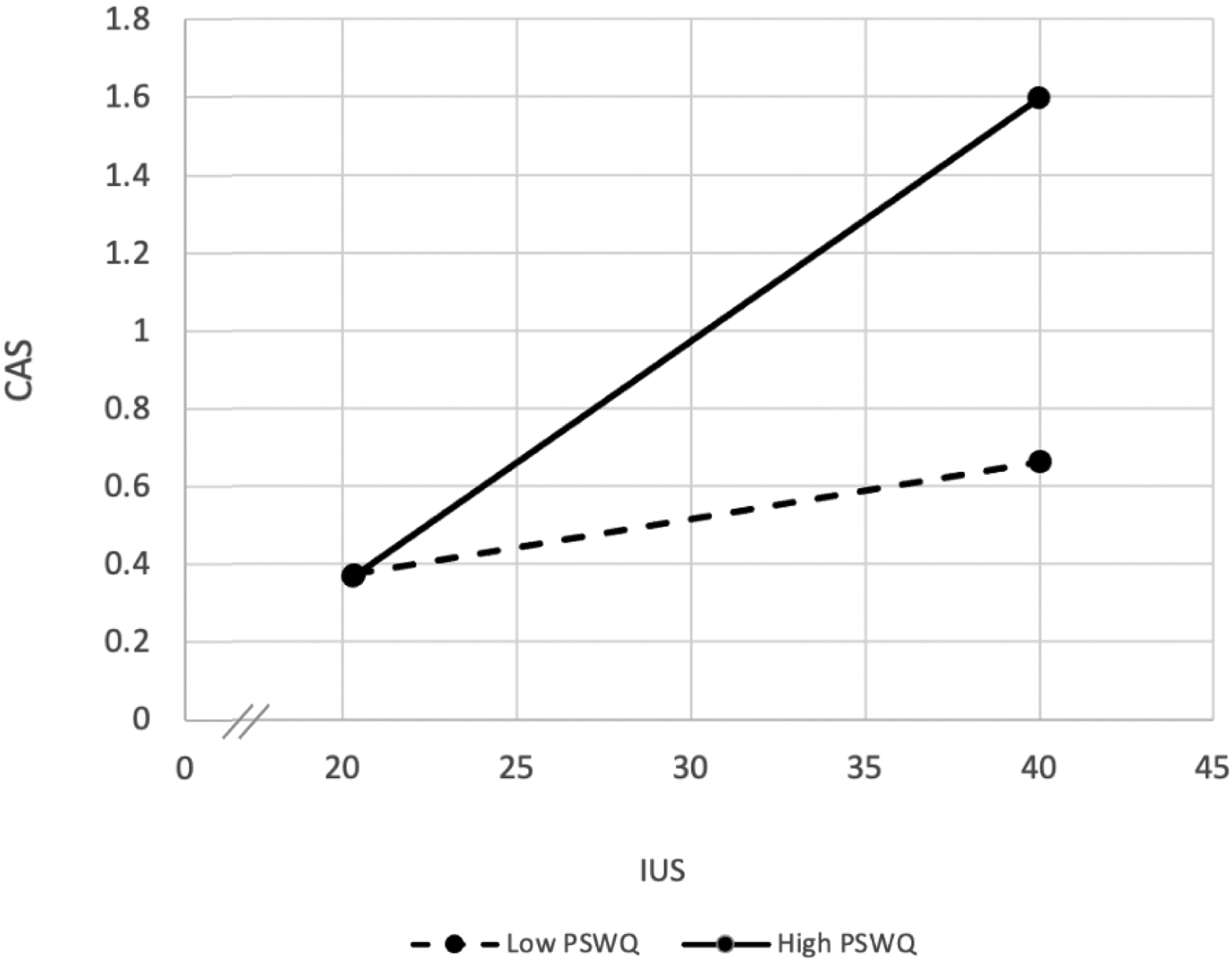

The IUS × PSWQ interaction was significant, showing that pre-pandemic trait worry moderated the relation of IU to Coronavirus anxiety (see γ03, p = .044). This interaction is displayed in Figure 11. At low levels of trait worry, IU had a nonsignificant relation to Coronavirus anxiety. At high levels of trait worry, the positive relation of intolerance of uncertainty to Coronavirus anxiety was larger in magnitude and significant. A regions of significance analysis revealed that at PSWQ values of 44.78 or higher, the effect of IUS on CAS was significant (Preacher et al., 2006). Contrary to prediction, the IUS × time and PSWQ × time interactions were nonsignificant (ps ≥ .47), providing no evidence that that pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty or trait worry moderated the overall downward trajectory of Coronavirus anxiety throughout the pandemic.

Figure 1.

Interaction of pre-pandemic intolerance of uncertainty (IUS) and trait worry (PSWQ) in predicting Coronavirus anxiety (CAS).

Discussion

The present study found that pre-pandemic IU significantly predicted the severity of both Covid Stress Syndrome and Coronavirus anxiety throughout 30 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a highly uncertain and ambiguous event, COVID-19 may have triggered anxious-distressed responding for individuals high in IU, who tend to perceive uncertainty as threatening (Carleton, 2012; Dugas et al., 1998). Results also extend prior research showing a cross-sectional relation between IU and poor mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic by demonstrating that pre-pandemic IU was predictive of anxiety-related responses to COVID-19 over time (Bredemeier et al., 2023; Jessup et al., 2022; Mallett et al., 2021, 2021; Millroth & Frey, 2021; Reizer et al., 2021). Such prospective prediction is important in evaluating IU as a vulnerability factor for maladaptive responding to COVID-19. Indeed, according to Koerner and Dugas’s (2008) criteria, processes may function as cognitive vulnerabilities if they (1) increase risk for a mental disorder, (2) have causal effects on the manifestation of a disorder or its underlying mechanisms, and (3) are stable and trait-like, yet also intervenable. The longitudinal approach employed in the present study demonstrates that IU increased risk for both Covid Stress Syndrome and Coronavirus anxiety. While causality cannot be inferred due to the lack of random assignment, results can be interpreted alongside prior experimental research demonstrating that IU has causal effects on anxiety, negative affect, and worry, all mechanisms associated with Covid-related distress (Rosser, 2019). Lastly, IU is a stable, yet modifiable construct (Boswell et al., 2013; Knowles et al., 2022) that may be relevant for predicting (and treating) adverse psychological reactions to future pandemics.

The present study also examined if habitual use of excessive worry uniquely conferred risk for anxious-distressed responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that pre-pandemic worry proneness significantly predicted the level of Covid Stress Syndrome, but only marginally predicted Coronavirus anxiety, throughout 30 weeks of the pandemic. Prominent models suggest that worry functions as a cognitive avoidance response to perceived future threats (Borkovec et al., 2004). Since Covid Stress Syndrome is largely comprised of concern over potential threats (e.g., regarding the pandemic’s socioeconomic consequences, sources of contamination, foreigners contributing to viral spread, etc.), preexisting tendencies to cope with threat via excessive worry may have conferred particular risk for experiencing distress in relation to these potential threats (Freeston et al., 1996; Taylor et al., 2020a). Whereas, Coronavirus anxiety more prominently features physiological symptoms of fear/anxiety (e.g., sleep and appetite disturbances, dizziness, nausea) that do not directly reflect the sources of worry (Lee, 2020).

The observed link between trait worry and Covid Stress Syndrome is consistent with the broader literature showing that worry functions as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy rooted in avoidance that confers risk for psychological distress (Borkovec et al., 1983, 2004; Newman et al., 2013). The present findings also expand prior research showing a cross-sectional relationship between worry and poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic by pointing to habitual worry as a prospective predictor of COVID-related anxious-distress four years later (Belen, 2021; Yıldırım & Özaslan, 2022). Accordingly, the evidence suggests that individual differences in the propensity to worry are a stable factor involved in people’s ability to successfully or unsuccessfully cope with the ongoing stress of the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, there is now evidence showing that pre-infection psychological distress, including worry proneness, may be a risk factor for post-COVID-19 conditions (sometimes called long COVID) in individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection (S. Wang et al., 2022). This suggests that preexisting levels of worry proneness may have important implications for COVID-related mental and physical health.

In conceptualizing vulnerability factors for anxious responding to COVID-19, it is important to consider specific contexts in which the effects of such vulnerabilities may be magnified or diminished. As worry is often recruited to regulate the emotional distress provoked by ambiguity for those high in IU, a co-occurring high propensity to worry may function as a context in which the harmful effects of IU are enhanced (Dugas et al., 2001). As such, an additional aim of the present study was to examine if trait worry moderated the relation between IU and anxiety-related outcomes during the pandemic. We found that worry significantly moderated the relation between IU and Coronavirus anxiety, but not Covid Stress Syndrome, over 30 weeks of the pandemic. For individuals high in trait worry, IU had a significant positive relationship with the severity of Coronavirus anxiety over time. For those low in trait worry, the effects of IU on Coronavirus anxiety were nonsignificant. These results suggest that IU is increasingly more likely to result in heightened Coronavirus anxiety when excessive worry is regularly employed as an emotion regulation strategy. The absence of excessive worry, however, may buffer against the vulnerability conferred by IU.

Contrary to prediction, worry did not moderate the link between IU and Covid Stress Syndrome. This may be because Covid Stress Syndrome encompasses a more heterogeneous set of cognitive and behavioral symptoms of distress whereas Coronavirus anxiety is more symptom-specific. The finding that worry did not moderate the link between IU and Covid Stress Syndrome may also suggest that the interaction of excessive worry and IU may be a process that is a unique signature for anxiety-specific outcomes during the pandemic rather than general distress. This view is consistent with prior research showing that IU moderated the relation between worry and arousal (a central feature of anxiety), but not the relation between worry and other symptom clusters (Bardeen et al., 2013). The finding that worry moderated only the link between IU and Coronavirus anxiety does contribute to our understanding of the functional relationship between IU and worry. For example, prior research suggests that this relationship is bidirectional: IU has been shown to significantly predict worry (Dugas et al., 2001; Koerner & Dugas, 2008; Sexton et al., 2003) and excessive worry, in turn, prevents non-threatening appraisals of uncertain scenarios, thus maintaining IU (Britton et al., 2019; Ladouceur et al., 2000). Our findings expand this understanding by suggesting that high trait worry may be a specific context in which the harmful effects of IU on Coronavirus anxiety are more strongly expressed.

The present study also found that the level of worry at which IU’s relationship with Coronavirus anxiety became significant (PSWQ score of 44.78) fell within the “moderate” range, and corresponded to an established cutoff score for identifying clinically significant generalized anxiety (PSWQ score of 45) (Behar et al., 2003; Dear et al., 2011). Prior research suggests that worry is best conceptualized dimensionally, with higher levels of worry being positively associated with symptoms of anxiety, stress, and depression (Olatunji et al., 2010). Thus, at elevated levels, worry seems to shift from being normal to maladaptive, and confers additive risk for psychopathology. Since the regions of significance findings converge with an established cutoff for clinically significant levels of worry, this suggests that there is a replicable tipping point at which habitual worry becomes a context in which other vulnerability factors, such as IU, may confer risk for adverse mental health outcomes.

Another major aim of the study was to examine predictors of the trajectory of COVID-related anxiety and distress over time. Consistent with prior research, there was a significant negative main effect of time on Coronavirus anxiety, showing that across the entire sample, COVID-related anxiety decreased throughout the 30-week study period (Asmundson et al., 2022; Bendau et al., 2021). Contrary to prediction, IU and worry did not interact with time to attenuate this downward trajectory in Coronavirus anxiety. This null finding may be due to the four year time lag between the assessment of the predictors and outcomes. While both IU and worry are largely stable and trait-like predictors, both variables have state, or time-variant, components (Knowles et al., 2022; Verkuil et al., 2007). Perhaps assessment of IU and trait worry in closer proximity to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (vs. four years prior) may have resulted in the prediction of subsequent longitudinal trends in anxiety and distress. Furthermore, there was no clear linear trend of increasing or decreasing Covid Stress Syndrome severity throughout the study period, nor significant moderation of the Covid Stress Syndrome trajectory by IU or trait worry. This contrasts with prior research showing a downward trajectory of Covid Stress Syndrome throughout the pandemic; however such prior research was limited by assessing Covid Stress Syndrome at only two time points with different samples (Asmundson et al., 2022). This may suggest that while physiological symptoms of fear/anxiety in response to COVID decreased during the pandemic, psychological distress reactions may have remained stable.

Given the high rates of poor mental health outcomes experienced by individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic, the present study’s findings have important clinical implications (da Silva et al., 2021; C. Wang et al., 2020). While some level of anxiety in response to stressors is normative and even adaptive, excessive anxiety and distress following the onset of COVID-19 could contribute to functional impairment and societal costs (e.g., via excess doctor’s appointments, lost productivity, etc.) (Taylor, 2021). The present findings suggest that IU and trait worry may have conferred vulnerability for excessive anxiety and distress following the onset of COVID-19, and accordingly may be potent treatment targets for individuals suffering from prolonged pandemic-related anxiety and distress. Further, understanding what factors increased individuals’ risk of poor mental health following COVID-19 also has implications for improving the broader health care system’s preparedness for future pandemics, as preventative care can be triaged towards those at the greatest risk (i.e., individuals high in IU and trait worry). Fortunately, there are evidence-based treatments like IU-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (IU-CBT) for excessive worry (Wahlund et al., 2020) that can be leveraged for such high-risk individuals. In future pandemics, screening tools such as the IUS-S and PSWQ could be disseminated in primary care settings and/or via public health messaging, and individuals who are identified as high-risk could be referred for targeted preventative interventions. Such public health measures might lower the prevalence and severity of adverse psychological adjustments to future pandemics (or similar wide-scale, chronic stressors) to reduce public burden.

Although the present findings suggest that IU and trait worry assessed in 2016 increased risk for anxiety and distress following the onset of COVID-19 in 2020, results should be interpreted in the context of several study limitations. The sample was predominantly white, female, and middle-aged. This restricted demographic diversity may limit the generalizability of results, particularly given research showing that IU predicted worse mental health outcomes for Black than White individuals during COVID-19 (Sadeh & Bounoua, 2023). Given the heightened racial stress experienced by non-White people during COVID-19 (Dush et al., 2022) and prior research showing that IU and worry are significantly associated with racial stress among Black individuals (Rucker et al., 2010), examining IU and worry as risk factors among people from diverse racial backgrounds may prove to be very informative. Additionally, the study relied on a restricted range of self-report measures to assess the constructs of interest. This is an important limitation given that predictors not assessed in the present study may explain meaningful variance in the trajectory of COVID-related distress. For example, Morales and colleagues (2022) found that pre-pandemic generalized anxiety predicted higher initial levels and maintenance of anxiety, stress, and COVID-related worries during the pandemic. This suggests that assessment of a broader array of predictors may facilitate our understanding of how pre-pandemic individual differences influence responses during (and after) the pandemic. One recent study found that while anxiety and depression increased during the pandemic, functional impairment remained stable (Gallagher et al., 2022). Assessment of a broader array of outcomes may facilitate a more precise understanding of COVID-relevant symptom trajectories and their predictors. Future research would also benefit from incorporating clinical and/or objective behavioral assessments of the predictor and outcome variables. Finally, while the present study does employ a longitudinal design, causality cannot be inferred given the observational nature of the data. Despite these study limitations, the present findings highlight the importance of preexisting levels of IU and worry in forecasting responses to stressful events like a global pandemic.

Highlights.

IU prospectively predicted Coronavirus anxiety and Covid Stress Syndrome

Worry prospectively predicted Covid Stress Syndrome

Worry moderated the link between IU and Coronavirus anxiety

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health [F31MH113271]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Because time was not part of the interaction between IUS-S and PSWQ, values are plotted at the mean time (95.55 days after the first day 2020 data collection). Consequently, the figure depicts the IUS-S × PSWQ interaction at the middle of the study.

References

- Asmundson GJG, Rachor G, Drakes DH, Boehme BAE, Paluszek MM, & Taylor S (2022). How does COVID stress vary across the anxiety-related disorders? Assessing factorial invariance and changes in COVID Stress Scale scores during the pandemic. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 87, 102554. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen JR, Fergus TA, & Wu KD (2013). The Interactive Effect of Worry and Intolerance of Uncertainty on Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(4), 742–751. 10.1007/s10608-012-9512-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behar E, Alcaine O, Zuellig AR, & Borkovec TD (2003). Screening for generalized anxiety disorder using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 34(1), 25–43. 10.1016/S0005-7916(03)00004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belen H (2021). The Impacts of Propensity to Worry and Fear of COVID-19 on Mental Health of University Students. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, Special Issue, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bendau A, Kunas SL, Wyka S, Petzold MB, Plag J, Asselmann E, & Ströhle A (2021). Longitudinal changes of anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: The role of pre-existing anxiety, depressive, and other mental disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 79, 102377. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Alcaine O, & Behar E (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice, 2004, 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Robinson E, Pruzinsky T, & DePree JA (1983). Preliminary exploration of worry: Some characteristics and processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(1), 9–16. 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90121-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Thompson-Hollands J, Farchione TJ, & Barlow DH (2013). Intolerance of Uncertainty: A Common Factor in the Treatment of Emotional Disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(6). 10.1002/jclp.21965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredemeier K, Church LD, Bounoua N, Feler B, & Spielberg JM (2023). Intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety sensitivity, and health anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring temporal relationships using cross-lag analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 93, 102660. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton GI, Neale SE, & Davey GCL (2019). The effect of worrying on intolerance of uncertainty and positive and negative beliefs about worry. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 62, 65–71. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr K, & Dugas MJ (2002). The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 931–945. 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00092-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN (2012). The intolerance of uncertainty construct in the context of anxiety disorders: Theoretical and practical perspectives. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 12(8), 937–947. 10.1586/ern.12.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Norton MAPJ, & Asmundson GJG (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva ML, Rocha RSB, Buheji M, Jahrami H, & Cunha K. da C. (2021). A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms during coronavirus epidemics. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(1), 115–125. 10.1177/1359105320951620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar KA, Iqbal N, & Mushtaq A (2017). Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: Examining the indirect and moderating effects of worry. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 129–133. 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, McMillan D, Anderson T, Lorian C, & Robinson E (2011). Psychometric Comparison of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Measuring Response during Treatment of Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40(3), 216–227. 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lahiri D, & Lavie CJ (2020). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 14(5), 779–788. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Gagnon F, Ladouceur R, & Freeston MH (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(2), 215–226. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Gosselin P, & Ladouceur R (2001). Intolerance of uncertainty and worry: Investigating specificity in a nonclinical sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 551–558. 10.1023/A:1005553414688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dush CMK, Manning WD, Berrigan MN, & Hardeman RR (2022). Stress and Mental Health: A Focus on COVID-19 and Racial Trauma Stress. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 8(8), 104–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston MH, Dugas MJ, & Ladouceur R (1996). Thoughts, images, worry, and anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 20(3), 265–273. 10.1007/BF02229237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, & Ladouceur R (1994). Why do people worry? Personality and Individual Differences, 17(6), 791–802. 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90048-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MW, Smith LJ, Richardson AL, & Long LJ (2022). Six Month Trajectories of COVID-19 Experiences and Associated Stress, Anxiety, Depression, and Impairment in American Adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(3), 457–469. 10.1007/s10608-021-10277-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentes EL, & Ruscio AM (2011). A meta-analysis of the relation of intolerance of uncertainty to symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 923–933. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup SC, Knowles KA, & Olatunji BO (2022). Linking the Estimation of Threat and COVID-19 Fear and Safety Behavior Use: Does Intolerance of Uncertainty Matter? International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 10.1007/s41811-022-00148-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravani V, Asmundson GJ, Taylor S, Bastan FS, & Ardestani SMS (2021). The Persian COVID stress scales (Persian-CSS) and COVID-19-related stress reactions in patients with obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders. Journal of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, 28, 100615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles KA, Cole DA, Cox RC, & Olatunji BO (2022). Time-Varying and Time-Invariant Dimensions in Intolerance of Uncertainty: Specificity in the Prediction of Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 53(4), 686–700. 10.1016/j.beth.2022.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner N, & Dugas MJ (2008). An investigation of appraisals in individuals vulnerable to excessive worry: The role of intolerance of uncertainty. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(5), 619–638. 10.1007/s10608-007-9125-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur R, Gosselin P, & Dugas MJ (2000). Experimental manipulation of intolerance of uncertainty: A study of a theoretical model of worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(9), 933–941. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00133-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA (2020). Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Studies, 44(7), 393–401. 10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC, & Pappalardo EA (2020). Clinically significant fear and anxiety of COVID-19: A psychometric examination of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113112. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamid FA, Veronese G, Bdier D, & Pancake R (2022). Psychometric properties of the COVID stress scales (CSS) within Arabic language in a Palestinian context. Current Psychology, 41(10), 7431–7440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett R, Coyle C, Kuang Y, & Gillanders DT (2021). Behind the masks: A cross-sectional study on intolerance of uncertainty, perceived vulnerability to disease and psychological flexibility in relation to state anxiety and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 22, 52–62. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Mennin DS, & Farach FJ (2007). The contributory role of worry in emotion generation and dysregulation in generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(8), 1735–1752. 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, & Borkovec TD (1990). Development and validation of the penn state worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milic M, Dotlic J, Rachor GS, Asmundson GJ, Joksimovic B, Stevanovic J, … & Gazibara T (2021). Validity and reliability of the Serbian COVID Stress Scales. PLoS One, 16(10), e0259062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millroth P, & Frey R (2021). Fear and anxiety in the face of COVID-19: Negative dispositions towards risk and uncertainty as vulnerability factors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 83, 102454. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales S, Zeytinoglu S, Lorenzo NE, Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Almas AN, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2022). Which Anxious Adolescents Were Most Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic? Clinical Psychological Science, 10(6), 1044–1059. 10.1177/21677026211059524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Jacobson NC, Zainal NH, Shin KE, Szkodny LE, & Sliwinski MJ (2019). The effects of worry in daily life: An ecological momentary assessment study supporting the tenets of the contrast avoidance model. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(4), 794–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Llera SJ, Erickson TM, Przeworski A, & Castonguay LG (2013). Worry and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Review and Theoretical Synthesis of Evidence on Nature, Etiology, Mechanisms, and Treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 275–297. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Grijalva M, Polo-Ambrocio A, Gómez-Bedia K, & Caycho-Rodríguez T (2022). Spanish translation and validation of the COVID stress scales in Peru. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Broman-Fulks JJ, Bergman SM, Green BA, & Zlomke KR (2010). A Taxometric Investigation of the Latent Structure of Worry: Dimensionality and Associations With Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Behavior Therapy, 41(2), 212–228. 10.1016/j.beth.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational Tools for Probing Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression, Multilevel Modeling, and Latent Curve Analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448. 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reizer A, Geffen L, & Koslowsky M (2021). Life under the COVID-19 lockdown: On the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and psychological distress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13, 432–437. 10.1037/tra0001012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BA (2019). Intolerance of Uncertainty as a Transdiagnostic Mechanism of Psychological Difficulties: A Systematic Review of Evidence Pertaining to Causality and Temporal Precedence. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(2), 438–463. 10.1007/s10608-018-9964-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker LS, West LM, & Roemer L (2010). Relationships among perceived racial stress, intolerance of uncertainty, and worry in a black sample. Behavior therapy, 41(2), 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, & Bounoua N (2023). Race moderates the impact of intolerance of uncertainty on mental health symptoms in Black and White community adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 93, 102657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton KA, Norton PJ, Walker JR, & Norton GR (2003). Hierarchical model of generalized and specific vulnerabilities in anxiety. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 32, 82–94. 10.1080/16506070302321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S (2021). COVID Stress Syndrome: Clinical and Nosological Considerations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(4), 19. 10.1007/s11920-021-01226-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Fong A, & Asmundson GJG (2021). Predicting the Severity of Symptoms of the COVID Stress Syndrome From Personality Traits: A Prospective Network Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.632227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, & Asmundson GJG (2020a). COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety, 37(8), 706–714. 10.1002/da.23071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, & Asmundson GJG (2020b). Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 72. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuil B, Brosschot JF, & Thayer JF (2007). Capturing worry in daily life: Are trait questionnaires sufficient? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(8), 1835–1844. 10.1016/j.brat.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund T, Andersson E, Jolstedt M, Perrin S, Vigerland S, & Serlachius E (2020). Intolerance of Uncertainty–Focused Treatment for Adolescents With Excessive Worry: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 27(2), 215–230. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2019.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, & Ho RC (2020). Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Quan L, Chavarro JE, Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Kang JH, Weisskopf MG, Branch-Elliman W, & Roberts AL (2022). Associations of Depression, Anxiety, Worry, Perceived Stress, and Loneliness Prior to Infection With Risk of Post–COVID-19 Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(11), 1081–1091. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton MG, Messner GR, & Marks JB (2021). Intolerance of uncertainty as a factor linking obsessive-compulsive symptoms, health anxiety and concerns about the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 28, 100605. 10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Retrieved January 4, 2023, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- Yıldırım M, & Özaslan A (2022). Worry, Severity, Controllability, and Preventive Behaviours of COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health of Turkish Healthcare Workers Working at a Pandemic Hospital. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2306–2320. 10.1007/s11469-021-00515-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]