Abstract

Background

The Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale and its short-form were developed in Canada and have been used internationally among numerous maternal populations. However, the psychometric properties of the scales have not been reviewed to confirm their appropriateness in measuring breastfeeding self-efficacy in culturally diverse populations. The purpose of this research was to critically appraise and synthesize the psychometric properties of the scales via systematic review.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. Three databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO) were searched from 1999 (original publication of the Scale) until April 27, 2022. The search was updated on April 1, 2023. Studies that assessed the psychometric properties of the BSES or BSES-SF were included. Two researchers independently extracted data and completed the quality appraisals.

Results

Forty-one studies evaluated the psychometrics of the BSES (n = 5 studies) or BSES-SF (n = 36 studies) among demographically or culturally diverse populations. All versions of the instrument demonstrated good reliability, with Cronbach's alphas ranging from .72 to .97. Construct validity was supported by statistically significant differences in mean scores among women with and without previous breastfeeding experience and by correlations between the scales and theoretically related constructs. Predictive validity was demonstrated by statistically significant lower scores among women who ultimately discontinued breastfeeding compared to those who did not.

Conclusion

The BSES and BSES-SF appear to be valid and reliable measures of breastfeeding self-efficacy that may be used globally to (1) assess women who may be at risk of negative breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., initiation, duration and exclusivity), (2) individualize breastfeeding support, and (3) evaluate the effectiveness of breastfeeding interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-17805-6.

Keywords: Breastfeeding self-efficacy, Systematic review, Psychometric evaluation

Article summary

The BSES and BSES-SF appear to be valid and reliable measures of breastfeeding self-efficacy that can be used globally to identify women at-risk for poor breastfeeding outcomes.

Background

The benefits of breastfeeding for disease prevention and health promotion are undisputed. If breastfeeding exclusivity occurred at a near universal level among young infants, it is estimated that 823,000 deaths in children under the age of five could be prevented annually [1]. Due to the beneficial effects, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months postpartum is recommended internationally. While the overall global rate of exclusive breastfeeding for infants less than six months of age is currently 44% [2], the World Health Organization has set a goal to achieve at least a 50% exclusivity rate by 2025 [3]. One potential highly effective strategy to improve exclusive breastfeeding rates is to tailor supportive resources among women at risk of poor breastfeeding outcomes [4]. Breastfeeding self-efficacy is one possible modifiable variable that has been consistently associated with positive breastfeeding outcomes, including exclusivity [5, 6].

Breastfeeding self-efficacy is defined as a mother’s confidence in ability to breastfeed [7] and predicts “whether a mother chooses to breastfeed, how much effort she will expend, whether she will persevere in her attempts until mastery is achieved, whether she will have self-enhancing or self-defeating thought patterns, and how she will emotionally respond to breastfeeding difficulties” (p. 736). Consistent with Bandura’s Social Learning Theory [8], Dennis’ breastfeeding self-efficacy theory [7] hypothesizes that maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy may be affected by four primary sources (e.g., antecedents) including [1] performance accomplishments (e.g., past breastfeeding experiences), [2] vicarious experiences (e.g., watching other women breastfeed), [3] verbal persuasion (e.g., encouragement from influential others such as friends, family, and lactation consultants), and [4] physiological responses (e.g., pain, fatigue, stress, depression, anxiety). Thus, an individual’s self-efficacy may be enhanced by altering the sources of information.

The 33 item five-point Likert Scale Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale (BSES) was developed by Dennis [9]. Each item was preceded by the phrase I can always…, with responses ranging from not at all confident to always confident. A psychometric evaluation of the BSES were initially conducted with a sample of 130 Canadian women, resulting in a Cronbach's alpha of 0.96 and 73% of all item-total correlations falling within the 0.30-0.70 range [9]. Factor analysis revealed two distinct factors: (1) Breastfeeding Technique Subscale, and (2) Intrapersonal Thoughts Subscale. In the initial sample, BSES scores were predictive of breastfeeding duration at 6 weeks postpartum. Internal consistency data, however, suggested the presence of redundant items and so the scale was retested in a larger Canadian sample [10]. After a detailed item analysis, 19 items were deleted, culminating in the 14-item BSES-Short Form (SF) [10]. Total scores range from 14–70 with lower scores indicating lower breastfeeding self-efficacy. Today, the BSES-SF is widely used internationally to identify women who may be at-risk for prematurely discontinuing breastfeeding.

In a meta-analysis of 11 trials evaluating breastfeeding self-efficacy interventions among women of term infants, researchers found that intervention groups participants were 1.56 times more likely to be breastfeeding at 1 month increasing to 1.66 times more likely at 2 months postpartum [5]. The researchers concluded that interventions that began in the postpartum period that used combined delivery settings (e.g., hospital and community) or were theoretically derived, had the largest effect on breastfeeding self-efficacy and rates of breastfeeding. Further, meta-regression analysis suggested the odds of exclusive breastfeeding increased by 10% among intervention participants for each 1-point increase in mean BSES scores between the intervention and control groups. Similarly, another systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 trials [11] revealed that women receiving breastfeeding support interventions had significantly improved breastfeeding self-efficacy scores during the first 4 to 6 weeks postpartum (SMD = 0.40, p = 0.006, 95% CI [0.11, 0.69]) and decreased perceptions of insufficient milk supply (median, 3.3, p < 0.001).

While a general review of the BSES-SF was completed [12], no systematic review has been undertaken to examine the application of both the BSES and BSES-SF in culturally and demographically diverse populations. The cross-cultural adaptation of the scale, as well as the validation among mothers with specific demographic or clinical characteristics, is crucial for enabling the instrument to serve as a useful international measure of breastfeeding self-efficacy. Furthermore, the development of modified versions of the instrument with sound psychometric properties facilitates an awareness of—and sensitivity to—the needs and perceptions of mothers with varied cultural, socioeconomic, and medical histories. Thus, the objective of this review was to appraise the validated BSES and BSES-SF in culturally and demographically diverse contexts.

Methods

Design

We performed a systematic review of quantitative studies using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13]. A protocol was not registered.

Sample: Defining the articles reviewed

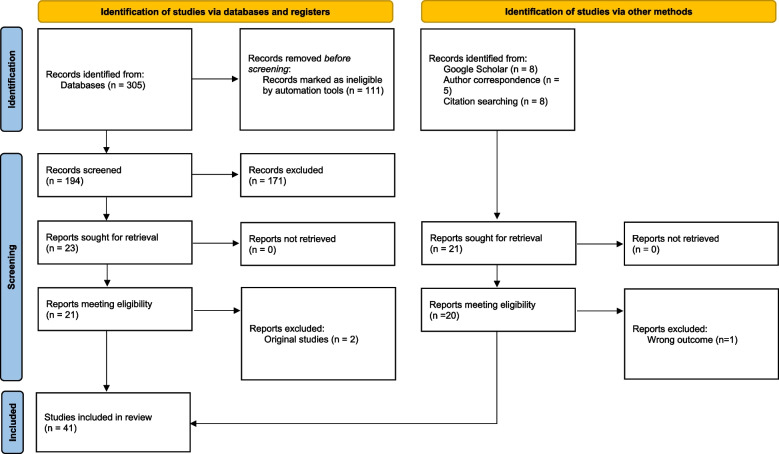

Quantitative studies (e.g., methodological, cross-sectional, cohort) were included if they used the BSES or BSES-SF and provided data concerning both the reliability and validity of the scale. Studies that aimed to determine predictive cut-off scores for the scale were also included if they analyzed the sensitivity and specificity of the scale at the identified cut-off. A total of 41 studies were included in the review. All studies were published in English; thus, there were no exclusions for language. Figure 1 displays a flowchart of the search strategy and the study selection process.

Fig.1.

PRISMA Flow diagram

Data collection: The search strategy and process

The initial search was conducted for published studies between 1999 (the publication year of the original BSES) and December 2021. Additional studies were identified via reference list searches and doing a ‘cited by’ search on Google Scholar and Medline as of April 1, 2023. We also contacted experts in the field to retrieve any data from recently completed studies not yet published. Searches of the literature were conducted using EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. The term “Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale” was searched and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms for “breastfeeding”, “self-efficacy”, “cultural adaptation”, “psychometric”, and “validated” were broadened to capture relevant literature. The search strategy is presented in Table S1.

Measurement

A structured data extraction form was developed to organize data from the studies by publication year, study location, objectives, population, validation of the BSES or BSES-SF, language used for the scale, time of administering the scale, and means and standard deviations (SD) of BSES or BSES-SF scores. Study quality was assessed using criteria suggested by Shrestha et al. [14] and Mirza and Jenkins [15] and included: (1) clarity of the study aim, (2) sample size justification, (3) sample representativeness, (4) clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, (5) description of maternal demographic data, (6) reporting of a response rate, (7) appropriate statistical analyses, and (8) evidence of participant informed consent. Possible scores of 1 (e.g., sample size justified) or 0 (e.g., sample size not justified) were used and combined to give a possible total score of 8 for each study. Quality criteria specific to the translation and validation of psychometric tools such as the BSES and the BSES-SF were adapted from Shrestha et al.’s [14] additional quality assessment parameters, which included an assessment of the translation methods used, cultural adaptation, as well as any modifications made to items in the scale. Two authors independently extracted data and completed the quality appraisals. When information was unclear authors reviewed the data and/or had a third author review to achieve consensus.

Data analysis

Data pertaining to the psychometrics of the scales were summarized and included internal consistency, factor analyses, known groups analyses, and predictive validity of the scales, as well as the correlation of the scores with other theoretically related constructs, negative and positive predictive value, and sensitivity and specificity. As no other measure of breastfeeding self-efficacy was used in these studies for comparison, instruments to which BSES or BSES-SF scores were compared differed slightly among the analyzed studies. Additional scales administered in several studies included the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [16] and the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) [17]. Since self-efficacy has been shown to be negatively influenced by psychological disorders such as depression; a negative correlation between BSES and EPDS scores was hypothesized. Based on the rationale that breastfeeding self-efficacy should be enhanced among mothers with higher overall self-efficacy, a positive correlation between BSES and GSES scores was also hypothesized.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The search yielded 305 studies, with 194 screened after duplicates were removed through automation. Of these screened studies, 171 did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 21 eligible studies after Dennis’ two original BSES [9] and BSES-SF [10] studies were excluded. Sixteen additional studies were identified via reference searches and reverse Google Scholar searches and five studies were identified pre-publication through author correspondence, with one not meeting the inclusion criteria. In total, 41 studies were included in the review with five focused on the original BSES and 36 presenting data on the BSES-SF. Of the BSES-SF studies, three reported on a modified scales for fathers [18–20] and three reported on a modified scale for mothers of preterm infants [21–23]. All included studies were of high quality with scores ranging from four to 8 eight (see Table S2).

Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. For the five studies validating the BSES, sample sizes ranged from 100 to 276 participants, with 60% falling within the recommended sample size for psychometric assessments of 5–10 subjects per item (Nunnally and Bernstein: Psychometric theory, unpublished). The 36 studies assessing the BSES-SF had sample sizes ranging from 18–1,524, all except two [24, 25] surpassing the minimum recommended sample size. Participants were primarily recruited from maternity wards of urban hospitals and most sample characteristics were representative of the regional population. The most common time to assess breastfeeding self-efficacy was in-hospital during the postpartum period (n = 17; 41%). However, the timing of assessment varied among some studies with assessment of breastfeeding self-efficacy conducted during the third trimester of pregnancy [26, 27], postnatally (time not reported) [28, 29], at 1 week [27], or open time periods such as two to six weeks [20].

Table 1.

Language of validation, objective, sample population and mean BSES/BSES-SF scores for all included studies

| Author (Year) | Study Aim | City/Region, Country | Study Population/Sample Size | Scale Language | Time of BSES Assessment | Mean BSES / BSES-SF Scores (SD) | aQuality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale (BSES) | |||||||

| Creedy 2003 [26] | To psychometrically test the BSES antenatally and at 1 and 16 weeks postpartum | Brisbane, Australia | 276 women at 36 + weeks gestation recruited from a university hospital | English |

Antenatal: 3rd trimester Postnatal: 1 and 16 weeks |

Antenatal: 126.16 (23.85) 1 week postnatal: 139.86 (23.87) 16 weeks postnatal: 142.26 (21.25) |

8 |

| Dai 2003 [30] | To translate the BSES into Mandarin and determine its psychometric properties | Tianjin, China | 186 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from an obstetric hospital | Mandarin Chinese | Postnatal: In-hospital | 118.78 (16.53) | 6 |

| Eksioglu 2011 [31] | To translate the BSES into Turkish and assess its psychometric properties | Altındağ, Izmir, Turkey | 165 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from two mother and child health-care units | Turkish | Postnatal: 1, 4 and 8 weeks |

1 week: 151.22 (12.39) 4 weeks: 154.99 (11.51) 8 weeks: 155.52 (11.35) |

6 |

| Molina Torres 2003 [32] | To translate the BSES into Spanish and determine its psychometric properties | San Juan, Puerto Rico | 100 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from a private hospital | Spanish | Postnatal: In-hospital | 131.8 (22.07) | 6 |

| Oriá 2009 [33] | To translate and psychometrically assess the BSES among women living in Fortaleza, Brazil | Fortaleza, Brazil | 117 women 30 + weeks gestation recruited during a prenatal visit at a teaching hospital | Portuguese | Antenatal: third trimester | NR | 5 |

| Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale- Short Form (BSES-SF) | |||||||

| Amini 2019 [28] | To evaluate the reliability and validity of the BSES-SF among Iranian mothers | Tehran, Iran | 379 mothers recruited from a health centre | Persian | Postnatal: NR | 50.80 (8.91) | 6 |

| Asgarian 2020 [34] | To explore the validity and reliability of BSES-SF among Iranian Farsi-speaking mothers | Qom, Iran | 174 women recruited from teaching hospital | Iranian Farsi | Postnatal: In-hospital | 54.32 (10.5) | 8 |

| Balaguer- Martinez 2022 [35] | To assesses the relationship between the BSES-SF score and the risk BF cessation and determine the cut-off point in the scale | Spain | 1845 mothers with an infant born at term (> 37 weeks) part of the LAyDI cohort | Spanish | Postnatal: within 15 days post birth, plus 1-, 2-, 4-, and 6-months post birth | 59.76 (9.95) | 7 |

| Basu 2020 [36] | To translate into Hindi and to psychometrically test the BSES-SF | North-East Delhi, India | 210 women with a child under 1 year recruited from well-baby and immunization clinics at health centers | Hindi | Postnatal: timing not reported | 54.7 (16.1) | 7 |

| Boateng 2019 [37] | To adapt the BSES-SF to emphasize EBF for use in a setting where continued, but not exclusive breastfeeding is common; to conduct psychometric testing of this adapted scale | Gulu, Uganda | 239 women recruited between 10–26 weeks gestation from a regional hospital | Acholi and Langi | Postnatal: 4 and 12 weeks |

4 weeks: Cognitive Subscale: 13.5 (4.1) Functional Subscale: 17.2 (4.3) 12 weeks: Cognitive Subscale: 13.6 (4.1) Functional Subscale: 17.7 (4.3) |

6 |

| Brandão 2018 [38] | To examine the psychometric characteristics of an antenatal version of the BSES-SF among pregnant Portuguese women | Northern Portugal | 373 women between 30 and 34 gestational weeks, recruited from two public hospitals | Portuguese | Antenatal: 3rd trimester | 57.93 (7.90) | 6 |

| Chipojola 2022 [18] | To examine the psychometric properties of the paternal BSES-SF in Malawian fathers | Lilongwe, Malawi | 180 fathers recruited from a hospital | Chichewa | Postnatal: In-hospital | 50.2 (11.9) | 7 |

| Dennis 2011 [39] | To psychometrically assess the BSES-SF antenatally and postnatally among adolescents | Winnipeg, Canada | 100 adolescents (15–19 years) 37 + weeks gestation recruited from two prenatal clinics at a teaching hospital | English |

Antenatal: 3rd trimester (34 weeks) Postnatal: 1 and 4 weeks |

Antenatal: 51.72 (7.69) 1 week postnatal: 56.23 (12.27) |

6 |

| Dennis 2018 [19] | To assess the psychometric properties of the BSES–SF among fathers | Toronto, Canada | 214 fathers recruited from a postpartum unit in a large teaching hospital | English | Postnatal: In-hospital and 6 weeks |

In-hospital: 48.96 (NR) 6 weeks: 54.54 (NR) |

6 |

| Dodt 2012 [40] | To psychometrically assess the BSES-SF among women living in northeast-Brazil | Fortaleza-CE, Brazil | 294 low-income women were recruited from a teaching university hospital | Brazilian Portuguese | Postnatal: In-hospital | NR | 6 |

| Dos Santos 2016 [41] | To verify the reliability and validity of the BSES-SF in Brazilian adolescent mothers | Brazil | 79 adolescent (13–19 years) mothers were recruited from a public maternity institution | Brazilian Portuguese | Postnatal: In-hospital | 56.58 (6.11) | 7 |

| Gerhardsson 2014 [42] | To translate and psychometrically test the Swedish version of the BSES-SF | Uppsala, Sweden | 120 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited at routine follow-up visits at the postnatal unit in a university hospital | Swedish | Postnatal: 1 week | 57.4 (8.8) | 7 |

| Gregory 2008 [43] | To psychometrically assess the BSES-SF among a multicultural sample of mothers living in the United Kingdom | Birmingham, United Kingdom | 165 women 36 + weeks gestation recruited from the maternity ward in a hospital | English | Postnatal: in-hospital and 4 weeks | In-hospital: 46.46 (12.75) | 7 |

| Handayani 2013 [24] | NR | Yogyakarta, Indonesia | 18 women recruited with a child between 0–6 months | Indonesian | Postnatal: timing not reported | NR | 6 |

| Husin 2017 [27] | To translate and assess psychometrics of the Malay version of BSES-SF in both antenatal and postnatal mothers | Malaysia | 101 antenatal women 32 + weeks gestation recruited from maternal and child health clinic and 104 postnatal women 37 + weeks gestation recruited at first postnatal home visit | Malay |

Antenatal: 3rd trimester Postnatal: 1 week |

Antenatal: 56.20 (8.75) Postnatal: 58.97 (8.68) |

7 |

| Iliadou 2020 [44] | To conduct psychometric testing of the Greek version of BSES-SF | Athens, Greece | 173 women 32 + weeks gestation recruited from an outpatient maternity department at a hospital | Greek |

Antenatal: 3rd trimester Postnatal: 3 days |

Antenatal: 44.2 (11.1) Postnatal: 47.7 (12.1) |

8 |

| Ip 2012 [45] | To translate the BSES-SF into Chinese and to examine its psychometric properties | Hong Kong | 185 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from a hospital postpartum unit | Hong Kong Chinese | Postnatal: In-hospital, 4 and 24 weeks | In-hospital: 41.1 (10.7) | 7 |

| Ip 2016 [46] | To establish the construct validity and prognostic ability of the Mandarin version of BSES-SF | Guangzhou, China | 562 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from a teaching hospital | Chinese Mandarin | Postnatal: In-hospital | In-hospital: 47.3 (10.5) | 6 |

| Küçükoğlu 2023 [20] | To translate and psychometrically test the PBSES-SF among Turkish fathers | Konya, Turkey | 221 fathers with an infant aged 2–6 weeks recruited from pediatric outpatient clinics at 2 research hospitals | Turkish | Postnatal: 2–6 weeks | 47.32 (NR) | 6 |

| Maurer (n.d.) (Maurer, et al.: The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form (BSES): German translation and psychometric assessment, unpublished) | To translate the BSES-SF into German and assess its psychometric properties | Germany and Austria | 355 postpartum mothers via social media | German | Postnatal: up to 12 weeks | 58.46 (8.42) | 7 |

| McCarter-Spaulding 2010 [47] | To assess the psychometric properties of the BSES-SF in Black women in the United States | Northeastern United States | 153 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from an urban teaching hospital | English | Postnatal: 1 and 4 weeks | Mean BSES-SF not reported | 7 |

| McQueen 2013 [48] | To test the reliability and validity of the BSES-SF among Aboriginal women | Ontario, Canada | 130 Aboriginal women recruited from an urban tertiary care hospital or a rural community hospital | English | Postnatal: In-hospital | In-hospital: 51.32 (11.74) | 8 |

| Mituki 2017 [25] | To translate, validate and adapt the BSES‐SF tool in a resource restricted urban setting in Kenya | Kenya | 42 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from prenatal clinic at a hospital | Kiswahili | NR | 60.95 (10.36) | 6 |

| Oliver-Roig 2012 [49] | To translate the BSES-SF into Spanish and assess its psychometric properties | Orihuela, Spain | 135 women 36 + week gestation recruited from a public hospital | Spanish | Postnatal: In-hospital | 51.94 (11.22) | 6 |

| Otsuka 2008 [50] | To examine the relationship between maternal perceptions of insufficient milk and breastfeeding confidence using the BSES | Tokyo and Kusatsu, Japan | 262 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from 2 obstetric hospitals | Japanese | Postnatal: In-hospital, 4-weeks |

In-hospital: 44.7 (11.9) 4-weeks: 43.8 (12.3) |

6 |

| Pavicic-Bosnjak 2012 [51] | To translate and psychometrically assess the Croatian version of the BSES-SF | Zagreb, Croatia | 190 women recruited from a teaching hospital | Croatian | Postnatal: In-hospital | 55 (7) | 6 |

| Petrozzi 2016 [52] | To translate the BSES-SF into Italian and investigate its predictive ability | Lido di Camaiore, Italy | 122 women recruited from a hospital | Italian | Postnatal: In-hospital | 54.8 (9.4) | 4 |

| Radwan 2022 [53] | To translate and examine the psychometric properties of the BSES-SF among mothers in the United Arab Emirates | Dubai, Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, and Fujairah, United Arabic Emirates | 457 women recruited from postpartum ward in 10 hospitals | Arabic | Postnatal: In-hospital | 55.22 (11.93) | 8 |

| Sandhi 2022 [29] | To assess the psychometric properties of the BSES-SF among Indonesian mothers | Yogyakarta City, Indonesia | 237 mothers 37 + weeks gestation recruited from five public health centers | Bahasa Indonesia | Postnatal: timing not reported | 56.4 (7.2) | 6 |

| Tokat 2010 [54] | To translate and psychometrically assess the BSES-SF among pregnant and postpartum women in Turkey | Izmir, Turkey | 144 pregnant women recruited during a regular antenatal visit at two private and two public outpatient clinics, and 150 women recruited from the postpartum ward at two public and one private hospital | Turkish |

Antenatal: during their antenatal visit in the third trimester Postnatal: In-hospital |

Antenatal: 58.52 (8.8) Postnatal: 60.09 (8.2) |

8 |

| Tokat 2020 [21] | To psychometrically assess the Turkish version of the modified BSES-SF among mothers of preterm infants | Izmir, Turkey | 135 mothers < 37 weeks’ gestation were recruited from a NICU | Turkish | Postnatal: 1 week | 43.32 (5.76) | 7 |

| Wheeler 2013 [22] | To psychometrically assess the modified BSES-SF among mothers of ill or preterm infants | Winnipeg, Canada | 144 women of ill or preterm infants recruited from 2 hospitals | English | Postnatal: 1 week post hospital discharge | 79.39 (9.98) | 5 |

| Witten 2020 [55] | To translate and psychometrically test the reliability and validity of the BSES-SF in the context of South Africa | Northwest province, South Africa | 180 mothers with an infant < 2 weeks were recruited from 8 primary health care clinics | Setswana | Postnatal: < 2 weeks | Median = 66 (IQR 62–68) | 8 |

| Wutke 2007 [56] | To translate the BSES-SF into Polish and assess its psychometric properties | Lodz, Poland | 105 women 37 + weeks gestation recruited from postpartum units in 5 hospitals | Polish | Postnatal: In-hospital | 55.5 (8.4) | 8 |

| Yang 2020 [23] | To translate, transculturally adapt and assess the psychometric properties of the modified BSES-SF among Chinese mothers of preterm infants | Hubei Province, China | 153 women < 37 weeks gestation recruited from postpartum ward from two hospitals | Chinese | Postnatal: In-hospital | 62.2 ± 16.1 | 6 |

| Zubaran 2010 [57] | To translate and psychometrically assess a Portuguese version of the BSES-SF | Brazil | 89 women living in southern Brazil, recruited from a university teaching hospital | Brazilian Portuguese | Postnatal: Between 2 and 12 weeks | (6.22) | 7 |

aThe quality assessment score was derived from criteria suggested by Shrestha et al. [14] and Mirza and Jenkins [15]. Scores can range from 0 to 8 with higher scores indicating higher quality

BSES Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale, BSES-SF Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form, NR not reported

The study samples included in the review were diverse in both cultural and demographic characteristics (see Table 1). Six studies assessed the scale in a clinically specific maternal sample including adolescents [39, 41], Canadian Indigenous women [48], black women in the United States [47], and low-income women [25, 40]. In two studies the authors assessed the English version in diverse populations in Australia [26] and the UK [43]. In most studies researchers reported that the scale was used with mothers of term infants. However, three studies reported on the use of the BSES-SF specifically in mothers of ill and preterm infants (< 36 weeks) in Canada [22], Turkey [21], and China [23]. Three studies reported on the use of the BSES-SF for fathers in Canada [19], Malawi [18], and Turkey [20]. Modifications for the BSES-SF scale for mothers of ill and preterm infants included, the addition of four new items, some items were changes to be applicable to mothers of preterm infants, and the item stem was changed from I can to I think I can. Similarly, for the BSES version for fathers, some items were changed to reflect the partner’s experience in assisting the breastfeeding mother.

The scale was translated into 24 different languages, including but not limited to Spanish, Turkish, Swedish, Croatian, Acholi and Langi, Japanese, Portuguese, Italian, Polish, and Malay (Table 2). In 20 studies, there were minor item word modifications. The translation methods were comparable across all studies with most completing back-translation (n = 28; 84.8%) to ensure semantic equivalency. However, there were variations noted in the quality of the translation process. Among the studies translated into English (n = 33), only 13 (approximately 40%) had at least two qualified personnel doing the forward and back translation with some not specifying if they were independent groups of translators. Eight studies were classified as not applicable regarding translation as they were psychometric studies conducted in English or the tool had been previously translated to English. Pilot testing was conducted in most of the translated studies (n = 27; 77.1%) with samples sizes ranging from 5 to 31. A few studies did not report data on pilot testing or translation procedures.

Table 2.

Translation methods and modifications for all included studies

| Author Year | Translated Language | Forward Translation | Back Translation | Pilot-Testing | Other Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale (BSES) | |||||

| Creedy 2003 [26] | NA | NA | NA | NA | None |

| Dai 2003 [30] | Mandarin Chinese | Yes, by one professional translator | Yes, by two bilingual lay-people | Yes, n = 21 | Minor wording changes to eight items and removal of one item “I can always keep my baby awake at my breast during a feeding” |

| Eksioglu 2011 [31] | Turkish | Yes, by five bilingual health professionals | Yes, by a linguist | Yes, n = 25 | Minor wording changes to three items |

| Molina Torres 2003 [32] | Spanish | Yes, by three professional translators | Yes, by two bilingual lay-people | Yes, n = NR | None |

| Oriá 2009 [33] | Portuguese | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, two bilingual translators | Yes, n = 15 pregnant and n = 15 postpartum women | Minor wording changes and changes to Likert response options |

| Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale- Short Form (BSES-SF) | |||||

| Amini 2019 [28] | Persian | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, by one bilingual translator | No | None |

| Asgarian 2020 [34] | Iranian Farsi | Yes, by two bilingual researchers | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, n = 10 | Minor wording changes to two items |

| Balaguer- Martinez 2022 [35] | Spanish | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Basu 2020 [36] | Hindi | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, by one native translator | Yes, n = 10 | Sample size included women up to 1 year postpartum; 50% conducted via interview at the request of participants |

| Boateng 2019 [37] | Acholi and Langi | Yes, by four experts on nutrition, public health, breastfeeding, and medicine | Yes, the same four experts | No | Initially, two items were modified and five items were added to reflect EBF; then up analysis, 7 from the original items and 3 from the added items were dropped, resulting in a 9-items scale |

| Brandão 2018 [38] | Portuguese | Yes, by two independent bilingual translators | Yes, by two independent bilingual translators | Yes, n = 15 | Antenatal version (e.g., items stem changes from “I can” to “I think I can”) |

| Chipojola 2022 [18] | ChiPacewa | Yes, by one bilingual speaker | Yes, by one bilingual speaker | Yes, n = 20 fathers | Paternal version minor word changes |

| Dennis 2011 [39] | NA | NA | NA | NA | Antenatal version: Stem of each question changed from “I can” to “I think I can” |

| Dennis 2018 [19] | NA | NA | NA | NA | Paternal version: All item stems were changed from “I can always” to “I can always help mom”; the word “my baby” was changed to “our baby”; and finally, an item was changed to acknowledge that the mother breastfeeds |

| Dodt 2012 [40] | Brazilian Portuguese | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Dos Santos 2016 [41] | Brazilian Portuguese | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gerhardsson 2014 [42] | Swedish | Yes, by four breastfeeding experts | Yes, by a professional translator | Yes, n = 5 | None |

| Gregory 2008 [43] | NA | NA | NA | NA | None |

| Handayani 2013 [24] | Indonesia | Yes, by five bilingual translators | Yes, but unclear | No | None |

| Husin 2017 [27] | Malay | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, n = NR | None |

| Iliadou 2020 [44] | Greek | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ip 2012 [45] | Hong Kong Chinese | Yes, by 1 of the authors, with reference to Chinese version of the original BSES (Dai and Dennis) | No | Yes, n = 12 | Minor modifications (unspecified) |

| Ip 2016 [46] | Mandarin Chinese | NA | NA | Yes, n = 10 | None – relevant items for the BSES-SF taken from the validated Mandarin version of the full scale |

| Küçükoğlu 2023 [20] | Turkish | Yes, by three bilingual translators | Yes, by three bilingual translators | Yes, n = 20 fathers | None |

| Maurer (n.d.) (Maurer, et al.: The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form (BSES): German translation and psychometric assessment, unpublished) | German | Yes, by three independent teams | Yes | Yes, by breastfeeding experts (n = 7) and breastfeeding mothers (n = 11) | None |

| McCarter-Spaulding 2010 [47] | NA | NA | NA | NA | None |

| McQueen 2013 [48] | NA | NA | NA | NA | None |

| Mituki 2017 [25] | Kiswahili | Yes, by one native speaker | Yes, by one native speaker | NR | Minor wording changes to seven items and the Likert scale phases were modified |

| Oliver-Roig 2012 [49] | Spanish | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, n = 9 | Minor changes, e.g., changed “confidence” in the English version to “self-confidence” in the Spanish version |

| Otsuka 2008 [50] | Japanese | Yes, separately by first author and a bilingual breastfeeding mother | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, n = 11 | Two minor wording modifications |

| Pavicic-Bosnjak 2012 [51] | Croatian | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, by two bilingual lay translators | Yes, n = 20 | Minor wording modifications on 2 items, and change of Likert-scale from “very confident / not confident” to “strongly agree / strongly disagree” |

| Petrozzi 2016 [52] | Italian | Yes, by the authors | Yes, by an English-speaker fluent in Italian | Yes, n = NR | None |

| Radwan 2022 [53] | Arabic | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, n = 10 | Yes, some questions reworded for clarity |

| Sandhi 2022 [29] | Bahasa Indonesia | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, n = 10 | None |

| Tokat 2010 [54] | Turkish | Yes, by three bilingual translators | Yes, by one lay bilingual translator | Yes, n = 11 pregnant and n = 16 postpartum women | Minor change to one item |

| Tokat 2020 [21] | Turkish | Yes, by three bilingual translators | Yes, by one bilingual translator | Yes, n = 12 | None |

| Wheeler 2013 [22] | NA | NA | NA | Yes, n = 10 | Preterm version: 4 items added to make scale applicable to mothers with ill or pre-term infants |

| Witten 2020 [55] | Setswana | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, by two bilingual translators | Yes, n = 6 | Minor wording changes to Likert scale |

| Wutke 2007 [56] | Polish | Yes, by 5 bilingual graduate students not associated with the project | Yes, by 5 different bilingual graduate students | Yes, n = 31 | Wording modified for some items to improve clarity |

| Yang 2020 [23] | Chinese | Yes, by 2 bilingual translators | Yes, by 2 bilingual translators | Yes, n = 15 | None |

| Zubaran 2010 [57] | Brazilian Portuguese | Yes, by 2 bilingual investigators | Yes, by the same two investigators | Yes, n = 10 | None |

BSES Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale, BSES-SF Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form, NA Not Applicable (Scale was in English or not translated), NR Not Reported, EBF Exclusive Breastfeeding

Psychometric assessments of BSES and BSES-SF

Reliability

Five studies that evaluated the BSES reported Cronbach's alphas ranging from 0.88 to 0.97 while the remaining 36 studies that assessed the BSES-SF reported Cronbach's alphas ranging from 0.72 to 0.96. Studies validating non-English versions (n = 34) had a wider range in Cronbach's alpha’s (0.72—0.95) than the seven studies analyzing English versions (0.88—0.96). The original BSES reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96 [9] and the BSES-SF reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94 [10], indicating that the translated and modified versions are comparable. The reliability of all modified tools was further supported by the fact that deletion of any single item did not lead to an increase in Cronbach's alpha of more than 0.10, except one [37]. For studies validating the BSES-SF, the majority of item-total correlations were above the recommended 0.30 criterion.

Construct validity

Five studies validated the construct validity of the BSES using factor analysis [26, 30–33], in addition to the original development by Dennis and Faux [9]. The five studies reported a 2-factor solution with eigenvalues ranging from 4.75 to 11.99 and the combined two factors contributing to 29.2% to 57% of the variance. In the original development of the BSES, the 2-factor solution had eigenvalues of 2.75 and 16.87 and the combined two factors contributed to 45.6% of the variance [9]. The 2-factor solution in all cases was consistent with the original BSES factor analysis and congruent with the theorized breastfeeding technique and intrapersonal thoughts subscales [9]. In the studies that completed a factor analysis of the BSES-SF, a single-factor solution was frequently reported, consistent with the original BSES-SF’s unidimensional structure [10].

Construct validity was further assessed in 32 studies using known-groups analysis. It was hypothesized that women who have successfully breastfed in the past would have higher self-efficacy scores than those with no prior breastfeeding experience. All studies (n = 18) except two [21, 41] reported significant differences in mean BSES or BSES-SF scores among women who had previously breastfed compared to those with no previous breastfeeding experience (Table 3). Nineteen studies compared mean breastfeeding self-efficacy scores between primiparous and multiparous women, with only half reporting a statistically significant difference based on parity. This finding is consistent with the breastfeeding self-efficacy theory [7] and supports the importance of the information source of performance accomplishment and that previous breastfeeding experience, not parity, is an important indicator of breastfeeding self-efficacy.

Table 3.

Psychometric properties of the modified versions of the BSES AND BSES-SF for all included studies

| Author Year | Cronbach’s alpha | Predictive Validity Assessment | Construct Validity Assessments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known groups analysis | Correlation with related constructs | ||||||||

| Behaviour / factor predicted | Predictive ( p < 0.05) | Comparator groups | Construct validity supported | Related construct used | Time of assessment of related construct | Correlation coefficient ® ( p < 0.001 unless specified) | Construct validity supported? | ||

| Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale (BSES) | |||||||||

| Creedy 2003 [26] | Antenatal = .97 | Antenatal BSES vs. 1-week BF practices and 16 weeks EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas with BF experience | Yes | HHLS | Antenatal | 0.73* | Yes |

| Postnatal = .96 | 1-week BSES vs. 16 weeks EBF | Yes | 4-weeks | 0.88* | Yes | ||||

| 16-weeks | 0.88* | Yes | |||||||

| Dai 2003 [30] | .93 | Feeding method, 4 and 8 weeks | Yes | NA | NA | EPDS | 4-weeks | -0.35 | Yes |

| 8-weeks | -0.20** | Yes | |||||||

| Eksioglu 2011 [31] |

1 week = .91 4 weeks = .92 |

1, 4, 8 weeks BSES vs. EBF | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Milina Torres 2003 [32] | .96 | BSES vs. EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas with BF experience | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Oriá 2009 [33] | .88 | NI | NA | Primiparas vs. multiparas | No | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Satis vs. unsatisfactory BF experiences | Yes | ||||||||

| Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale- Short Form (BSES-SF) | |||||||||

| Amini 2019 [28] | .91 | NI | NA | Primiparas vs. multiparas | No | EPDS | NR | -0.273 | Yes |

| PSS-10 | NR | -0.068 (NS) | No | ||||||

| Asgarian 2020 [34] | .92 | NI | NI | Primiparas vs Multiparas | No | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Balaguer-Martinez 2022 [35] | NR | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Basu 2020 [36] | .87 | NI | NI | Primiparas vs Multiparas | No | EPDS | NR | NR | Yes |

| MSPSS | NR | NR | Yes | ||||||

| Boateng 2019 [37] |

4-week: Cognitive = .82 Functional = .77 12-week: Cognitive = .85 Functional = .79 |

4-week: BSES-SF vs. 4, 12, 24 weeks EBF 12-week: BSES-SF vs. 12 and 24 weeks EBF |

Yes, but not at 24 weeks Yes |

Primiparas vs Multiparas Correct vs. Incorrect BF knowledge |

No Yes -Cognitive Subscale No-Functional Subscale |

EBFSS | 4 and 12 weeks |

Cognitive Subscale Informational EBFSS: 0.23; Emotional EBFSS:0.28 BSES-SF Functional Subscale Instrumental EBFSS:0.31; Informational EBFSS: 0.39; Emotional EBFSS:0.47 |

Yes |

| CESD | 4 and 12 weeks | BSES-SF Functional Subscale and depression: -.014 | Yes | ||||||

| Brandão 2018 [38] | .92 | Antenatal BSES-SF vs. 4 weeks EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas with BF experience | Yes | STAI | Antenatal and 4, 12, 24 weeks | NI | Yes |

| Antenatal BSES-SF vs. 12- and 24-weeks EBF | No | Intention to BF for > 24 weeks vs. < 24 weeks | Yes | EPDS (> 9) | Antenatal and 4, 12, 24 weeks | NI | Yes | ||

| Chipojola 2022 [18] | .90 | NI | NI | Primiparas vs. multiparas | Yes | WHOQoL-BREF | NR |

Psychological well-being = 0.23 Social relations = 0.28 The environment = .30 Physical well-being = .01 |

Yes, except for physical well-being |

| Dennis 2011 [39] | Antenatal = .84 | Antenatal BSES-SF vs. BF initiation | Yes | Adolescents with prior BF experience vs. those without | Yes (for antenatal but not postnatal) | BAQ | Antenatal | .41 | Yes |

| Postnatal = .93 | Antenatal and postnatal BSES-SF vs. 4-week BF duration and exclusivity | Yes | Decided to BF before vs during pregnancy | Yes (for antenatal but not postnatal) | |||||

| Dennis 2018 [19] |

Antenatal = .91 Postnatal = .92 |

Paternal in-hospital BSES–SF vs. 6-weeks and 12-week EBF | No | Paternal in-hospital BSES–SF vs. Maternal in-hospital BSES–SF | Yes | IIFAS | Antenatal & in-hospital |

Antenatal = .26 In-hospital = .40 |

Yes |

| Fathers’ perception of breastfeeding importance (designed for study) | In-hospital | .27 | Yes | ||||||

| 6-week BSES–SF vs. 12-week EBF | Yes | Involvement in decision making (yes/no) | In-hospital | NR | Yes | ||||

| Breastfeeding progress in-hospital (designed for study) | In-hospital | .27 | Yes | ||||||

| Dodt 2012 [40] | .74 | NI | NI | Primiparas vs. multiparas | No | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Previous BF experience vs. none | Yes | ||||||||

| Dos Santos 2016 [41] | .82 | NI | NI | Primiparas vs. multiparas | No | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Previous BF experience vs. none | No | ||||||||

| Gerhardsson 2014 [42] | .91 | BSES-SF vs. EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas | Yes | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Positive vs. negative BF experiences | Yes | ||||||||

| Gregory 2008 [43] | .90 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 4-week EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas with BF experience | Yes | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Handayani 2013 [24] | .77 | NI | NA | NI | NA | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Husin 2017 [27] |

Antenatal: .94 Postnatal: .95 |

NI | NA | NA | NA | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Iliadou 2020 [44] | .93 | 3-day BSES-SF vs. 6-month EBF | Yes | NI | NA | EPDS | Antenatal | .23 * | Yes |

| Postnatal (3 ddp) | -.22 * | Yes | |||||||

| Ip 2012 [45] | .95 | BSES-SF and BF duration | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| BSES-SF vs. 4-week EBF | Yes | ||||||||

| BSES-SF vs. 24 weeks EBF | Yes, compared to bottle feeding but not partial BF | ||||||||

| Ip 2016 [46] | .94 | BSES-SF at 3 dpp predicted EBF | Yes | NI | NA | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Küçükoğlu 2023 [20] | .93 | NI | NA | NI | NA | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Maurer (n.d.) (Maurer, et al.: The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form (BSES): German translation and psychometric assessment, unpublished) | .88 | NI | NA | vs. women with two, three or more children | Yes | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| McCarter-Spaulding 2010 [47] | .94 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 4-week BF duration | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | NSB | 1-week and 4-weeks postpartum |

1 week = .44 4-weeks = .40 |

Yes |

| In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 4-week EBF | Yes | Intention to BF for > 24 weeks vs. < 24 weeks | Yes | ||||||

| In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 24-weeks BF duration | Yes | ||||||||

| McQueen 2013 [48] | .95 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 4-week EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas with BF experience | Yes | EPDS | 4 weeks postpartum | NR | Yes |

| In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 8-week EBF | Yes | ||||||||

| Mituki 2017 [25] | .91 | BSES-SF vs. 6-week EBF | Yes | NI | NA | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Oliver-Roig 2012 [49] | .92 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 3 weeks EBF | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | GSEI | 2 dpp | .5 | Yes |

| GSES | 2 dpp | .24†† | Yes | ||||||

| SMSE | 2 dpp | .41 | Yes | ||||||

| Women with positive vs. negative BF experiences | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Otsuka 2008 [50] | .95 | BSES-SF vs. 4-week EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas | Yes | PIM | 4 weeks | -.45 | Yes |

| Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | ||||||||

| Intention to EBF vs. not | Yes | ||||||||

| Pavicic-Bosnjak 2012 [51] | .86 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 4- and 24-weeks BF duration | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas | Yes | SOC | In-hospital | .32 | Yes |

| In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 4 and 24 weeks EBF | Yes | Multiparas with > 24 weeks vs. ≤ 24 weeks of BF | Yes | ||||||

| Petrozzi 2016 [52] | .92 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas | No | EPDS | In-hospital | − .18*** | Yes |

| Radwan 2022 [53] | .95 | BSES-SF vs. 24-week EBF | Yes | Primiparas vs. multiparas | Yes | EPDS | NR | -.23 | Yes |

| Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | ||||||||

| Sandhi 2022 [29] | .90 | NI | NR | Primiparas vs. multiparas | Yes | EPDS | NR | -.213 | Yes |

| HADS – depression subscale | NR | -.171 * | Yes | ||||||

| Tokat, 2010 [54] |

Antenatal = .87 Postnatal = .86 |

Antenatal BSES-SF vs. 12-weeks BF duration and EBF | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | HADS – Anxiety subscale | NR | -.147 *** | Yes |

| In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 12-weeks BF duration and exclusivity | Yes | ||||||||

| Tokat 2020 [21] | .72 | 1-week BSES-SF vs. 4-week EBF | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | No | BAI | 1 week postpartum | -.219 *** | Yes |

| Wheeler 2013 [22] | .88 | 1-week BSES-SF vs. 6 weeks BF duration | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | HHLS | 1 week | − .84 | Yes |

| Witten 2020 [55] | .83 | BSES-SF vs. 4–8 weeks BF duration and exclusivity | Yes | Primiparous vs. multiparas | Yes | EPDS | NR | -.17 | No |

| Wutke 2007 [56] | .89 | In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 8- and 16-weeks BF duration | Yes | Primiparous vs. multiparas | Yes | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| In-hospital BSES-SF vs. 8 and 16-week EBF | Yes | Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | ||||||

| Yang 2020 [23] | .973 | NI | NA | Primiparous vs. multiparas | Yes | NI | NA | NA | NA |

| Women with BF experience vs. those without | Yes | ||||||||

| Zubaran 2010 [57] | .71 | BSES-SF vs. EBF | Yes | Primiparous vs. multiparas | No | EPDS | Between 2–12 weeks postpartum | -.41 | Yes |

BAQ Breastfeeding Attitudes Questionnaire, BAI Beck Anxiety Inventory, BSES Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale, BSES-SF Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form, CESD Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, dpp days postpartum, EPDS Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, GSEI Global Self-Efficacy Index, GSES General Self-efficacy Scale, HAS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HHLS Hill & Humenick Lactation Scale, MSPSS Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, NA Not Applicable, NI Not Indicated, NSB Network Support for Breastfeeding Tool, PIM Perception of Insufficient Milk, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, PSS Perceived Stress Scale, QMIDAT Questionnaire Measure of Individual Differences in Achieving Tendency, RSES Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, SMSE Stress Management Self-Efficacy Scale, SOC Sense of Coherence Scale, week weeks postpartum

* p = < 0.01

** p = 0.04

*** p = < 0.05

†† p = 0.005

Mean breastfeeding self-efficacy scores were compared across the other known-group variables including: (1) accurate versus inaccurate breastfeeding knowledge [37]; (2) intended breastfeeding duration more than 6 months versus less than 6 months [38, 47]; (3) positive versus negative previous breastfeeding experience [33, 42, 49]; (4) timing of decision to breastfeeding comparing early versus late pregnancy [39]; and, (5) exclusive versus partial breastfeeding (Maurer, et al.: The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form (BSES): German translation and psychometric assessment, unpublished). In all studies, researchers reported significant group differences in mean breastfeeding self-efficacy scores and the scale’s ability to accurately predict group membership. When in-hospital BSES-SF scores were examined between maternal-paternal pairs, a significant correlation (r = 0.53, p < 0.001) was found [19].

Correlations between breastfeeding self-efficacy scores and other theoretically related constructs were examined in several studies. Constructs for which a hypothesized positive correlation was found included the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) [49]; the Sense of Coherence (SOC) subscales of comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness [51]; the Stress Management Self-Efficacy Scale (SMSE) [49]; the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [58]; the Hill and Humenick Lactation Scale (HHLS) [22, 26]; the Breastfeeding Attitudes Questionnaire (BAQ) [39]; the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) [19]; the Exclusive Breastfeeding Social Support scale (EBFSS) [59]; the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [36]; the Network Support for Breastfeeding Tool [47]; the WHO Quality of Life (QoL)-BREF [18]; maternal perceptions of breastfeeding progress [19]; and paternal perceptions of breastfeeding importance [19] (Table 3). Researchers in eleven studies reported a significant negative association between EPDS and BSES scores [28–30, 36, 38, 44, 48, 52, 53, 55, 57]. In particular, women with higher scores on the EPDS had significantly lower BSES scores. Using other measurements of depression, Boateng et al. [37] reported a negative correlation between Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [60] and BSES-SF scores and two researchers [29, 54] reported a negative correlation between the HADS depression subscale and BSES-SF scores. All three studies that examined the correlation between anxiety and BSES-SF, researchers found a negative correlation between anxiety and BSES-SF scores, using different measurement tools [21, 29, 38]. Lastly, Otsuka et al. [50] reported a negative correlation between BSES-SF scores and maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply as measured by the PIM tool. Notably, translated scales also displayed significant construct validity and convergent validity with translated versions of other theoretically related constructs. Thus, evidence of construct and convergent validity in these studies conducted with non-English speaking participants adds to the strength of the psychometric analysis and provides further support for the use of the translated version in the tested population.

Predictive validity

The utility of BSES and BSES-SF scores as a means of predicting actual breastfeeding outcomes was assessed in most of the studies, wherein prior mean scores of mothers who breastfed were compared to those who discontinued breastfeeding. In the original BSES validation assessment, mothers still exclusively breastfeeding at six weeks postpartum had significantly higher mean scores (M = 173.5, SD = 20.9) than those engaging in combination feeding (M = 161.9, SD = 37.1) or exclusively bottle-feeding (M = 145.3, SD = 22.4) [9]. Two studies assessed predictive validity of the BSES-SF with regard to breastfeeding initiation outcomes [10, 39] (Table 3). Thirteen studies evaluated the utility of the BSES (n = 2) and BSES-SF (n = 11) as predictors of breastfeeding duration, and 25 studies reported results on the predictive validity of BSES (n = 4) or BSES-SF (n = 21) scores as indicators of breastfeeding exclusivity. Statistical significance was reached in all 25 studies except four.

Sensitivity and specificity

In two studies [35, 45], researchers evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of the BSES-SF at particular cut-off points using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Sensitivity provides an estimate of the tool’s accuracy in identifying mothers at risk of premature breastfeeding cessation (i.e., the proportion of the sample that discontinued breastfeeding prior to the time period in question and scored below the identified cut-off). In contrast, specificity refers to the proportion of the sample that did not discontinue breastfeeding before the assessed time period and scored above the identified cut-off. In the Hong Kong Chinese version of the BSES-SF, Ip et al. [45] identified the optimal cut-off for predicting early breastfeeding cessation (before 6 months) to be a score of 45.5 out of 70. Sensitivity at this cut-off score was 77%, and specificity was 73%. The negative predictive value of the scale indicated that 92% of mothers who scored below 45.5 discontinued breastfeeding prior to 6 months postpartum. In the Spanish version of the BSES-SF, Balaguer-Martinez et al. [35] found that the area under the curve was above the threshold for good predictive power for mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding at 1 and 2 months. To achieve 80% sensitivity the BSES-SF cut-off score was 59 at 1 month and 58 at 2 months. These findings demonstrate the utility of the BSES-SF as a tool to identify mothers at risk of prematurely discontinuing breastfeeding.

Discussion

In this systematic review, an evaluation of the reliability and validity of the BSES and BSES-SF scales in multiple languages, as well as their psychometric assessments in specific perinatal populations, including fathers [18–20] and parents with an ill or preterm infant [21–23], was conducted to appraise their effectiveness in identifying women and partners at risk of poor breastfeeding outcomes. This review is the first to evaluate the psychometrics of translated and adapted versions of the BSES and BSES-SF among demographically and culturally diverse populations. Additionally, this is the first review to assess the rigour and quality of the studies that have adapted and applied the BSES or BSES-SF for measuring breastfeeding self-efficacy. The BSES and BSES-SF have been psychometrically tested in 41 studies and translated into 26 languages other than English. Psychometric properties of the BSES and BSES-SF reported in the included studies were comparable to the original studies completed by Dennis [9, 10] indicating the utility of the instrument as an adaptable and reliable tool for measuring breastfeeding self-efficacy in diverse populations and settings. However, our review also found that some studies had deficiencies in their translation and cultural adaptation processes. Thus, while the BSES and BSES-SF appear to have sound psychometric properties across studies, caution in the interpretation of the findings should be considered as cultural aspects may not have been captured by the instruments [14]. Future studies should use established methodological approaches [14, 61] for translating and adapting the BSES-SF for use in cross-cultural research to ensure important cultural nuances are included in translated and culturally adapted tools.

Reliability was indicated with all Cronbach alphas coefficients exceeding the recommended 0.70 for established instruments (Nunnally and Bernstein: Psychometric theory, unpublished). There was variability between studies with some translated studies having wider Cronbach alpha coefficients than the non-translated studies. This could be due to the sample size, slight modifications made during the translation or adaptation process, cultural nuances that might not be captured in the translated version or varying sample characteristics of the included studies. We anticipated some variability and do not believe that this is an appreciable difference as all studies exceeded the recommendation. As such, this does not impact the overall reliability of the BSES-SF to be used in diverse samples effectively to guide interventions.

The modified versions of the BSES and the short form were shown to be conceptually valid with the majority of the studies reporting expected correlations with other widely used and theoretically related constructs such as the depression, anxiety, general self-efficacy, breastfeeding attitude, and sense of coherence. Moreover, considering the main results from across all studies, the BSES and BSES-SF and their adapted versions demonstrated significant predictive validity at various time points in the postpartum period. This finding supports the notion that even after translation or modification of these scales, they remain useful tools for identifying mothers at risk of negative breastfeeding outcomes in terms of all three breastfeeding parameters: initiation, duration, and exclusivity. This has significant implications for applying the BSES and BSES-SF in future studies across various cultural and demographic contexts.

Conceptual equivalence was another key indicator in measuring the comparability of the original English BSES and BSES-SF with its adapted, translated versions. While most of the studies identified used forward and back-translation, it is important to note that some studies used lower quality translation processes with only one individual performing the translation and in other studies limited details were provided. Back-translation to English may have been influenced by translators possessing knowledge of the original English version of the scale, especially if forward and back-translations were conducted by the same group. This method may result in conceptual disparities between the original English BSES and its short form and their translated versions. Thus, it is important that rigorous translation and adaptation processes be used to enhance the validity and reliability of the instrument (e.g., BSES-SF) for use among individuals of diverse cultures and languages [61].

While the BSES and BSES-SF were widely used globally, we found that middle to higher income countries have predominantly adapted and validated the tool. This is important to acknowledge as cultural and demographic influences may have led to higher breastfeeding self-efficacy in some studies. In countries with higher rates of breastfeeding, women are typically more often exposed to the primary sources of self-efficacy (e.g., antecedents) [7] such as vicarious experience (seeing others breastfeed) and verbal persuasion (receiving positive reinforcement). Furthermore, women may have received more assistance (e.g., education and support) [5] with breastfeeding in some settings thereby enhancing others sources of information such as performance accomplishment.

In many low and middle-income countries, there is a growing burden of breastfeeding attrition and increased reliance on formula use [62]. Major contributing factors to this trend are the influence of the private sector in promoting formula as an alternative to breastfeeding, lack of access to health care professionals and support from caregivers, limited education, and poor awareness stemming from broader political and economic disadvantages [4, 61, 63]. These contributing factors highlight the need for continued analyses of the factors associated with low breastfeeding initiation, duration and exclusivity, and underline the importance of developing reliable and valid instruments for identifying mothers most at risk of developing suboptimal breastfeeding practices. The psychometrics of such tools should be assessed in a wide range of languages, demographic contexts, and cultural settings. While our review found that the BSES and BSES-SF are adaptable, reliable, and validated tools globally, the benefits of the tool have not been tested and evaluated in resources poor settings.

Overall, these findings have important implications globally for clinical practice. The BSES and BSES-SF appear to be reliable and valid tools that may be used to assess mothers’ breastfeeding self-efficacy and plan interventions that are based on maternal need [7]. While our review included studies that assessed breastfeeding self-efficacy at various time periods, the antenatal period and the early postpartum period, soon after delivery, have the most clinical utility for assessing breastfeeding self-efficacy. As the main purpose in administering the BSES-SF is to identify women who may be at risk for early breastfeeding discontinuation, assessment of breastfeeding self-efficacy later in the postpartum period is not as clinically relevant as infant feeding has typically been established.

The total BSES score (14 – 70) may be used to identify mothers with low breastfeeding self-efficacy who may be at risk for negative breastfeeding outcomes (e.g., initiation, duration and exclusivity) and may benefit from additional supportive interventions [64]. Conversely, mothers who have high breastfeeding self-efficacy may be recognized as being more likely to succeed with breastfeeding; however, additional assistance may still be required, particularly when experiencing breastfeeding difficulties [7]. It is noteworthy that we do not recommend a specific cut-off score (e.g., total score) to delineate high versus low breastfeeding self-efficacy as breastfeeding self-efficacy scores can be culturally specific and vary. The single item BSES scores (1 – 5) can also be used to assess maternal perceptions of self-efficacy regarding specific components of breastfeeding (e.g., determine the baby is getting enough, proper latch, exclusive breastfeeding, etc.). Individual items scores (1 – 5) can be used to identify perceptions of low self-efficacy (item score ≤ 3) and items where the mother feels efficacious (item score ≥ 4) so that support specific to individual maternal needs can be provided [64]. The BSES has also been utilized to develop and/or evaluate the efficacy of various types of supportive interventions [5, 6]. Finally, the BSES assessment may provide health care professionals with a better of understanding of where mothers lack breastfeeding confidence and why they may be unsuccessful despite additional support [7].

Limitations

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, we found that only two studies included sensitivity and specificity data and reported negative and positive predictive values. Hence, we were not able to conduct a comprehensive analysis of these parameters. Second, the quality of the translation and cultural adaptation among several studies was lacking. Some studies also had missing data (e.g., not reported) affecting the assessment of reliability and validity. Finally, while most studies in this review employed very similar validation methods, the timing of assessment varied among studies as did the characteristics and geographic location of the study participants. The heterogeneity of the samples can make comparison across studies difficult; however, the consistency of the findings between studies also suggests the versatility of the tool among diverse groups.

Conclusion

Breastfeeding is a practice that is approached and perceived differently among different cultures, and premature discontinuation of breastfeeding is a global public health concern. Continued efforts are needed in the cross-cultural adaptation of the BSES and BSES-SF to effectively serve diverse populations and provide contextually appropriate measures of breastfeeding self-efficacy. We recommend that future studies validating translated or adapted versions of the BSES and BSES-SF adopt more systematic approaches to empirical validation, cultural adaption, and translation of the scales that are consistent with those used in the original analysis of the psychometric properties of the BSES and BSES-SF. Considering the extent to which the BSES and BSES-SF take into account the needs and perceptions of non-English-speaking mothers’ self-efficacy, further efforts should be made to translate the BSES into other languages.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:Table S1. Search strategy.

Additional file 2:Table S2. Study quality assessment for all included studies (and the original scales).

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Abbreviations

- BAQ

Breastfeeding Attitudes Questionnaire

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- BSES

Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale

- BSES-SF

Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form

- CESD

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- Dpp

Days postpartum

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- GSEI

Global Self-Efficacy Index

- GSES

General Self-efficacy Scale

- HAS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HHLS

Hill & Humenick Lactation Scale

- MSPSS

Multidimensional scale of perceived social support

- NA

Not Applicable

- NI

Not Indicated

- NSB

Network Support for Breastfeeding Tool

- PIM

Perception of Insufficient Milk

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- PSS

Perceived Stress Scale

- QMIDAT

Questionnaire measure of individual differences in achieving tendency

- RSES

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

- SMSE

Stress Management Self-Efficacy Scale

- SOC

Sense of Coherence Scale

Authors’ contributions

CLD and KM conceptualized the manuscript, did the initial search, critical appraisal and draft. JD, SS and KM updated the search and critical appraisal. CB assisted with the writing of the paper and critical review. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding. 2021. Accessed 5 Jan 2022.

- 3.World Health Organization. Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/113048/WHO_NMH_NHD_14.1_eng.pdf. 2014. Accessed 5 Jan 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387:491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brockway M, Benzies K, Hayden KA. Interventions to improve breastfeeding self-efficacy and resultant breastfeeding rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Lact. 2017;33(3):486–99. doi: 10.1177/0890334417707957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chipojola R, Chiu HY, Huda MH, Lin YM, Kuo SY. Effectiveness of theory-based educational interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;109:103675. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis CL. Theoretical underpinnings of breastfeeding confidence: a self-efficacy framework. J Hum Lact. 1999;15(3):195–201. doi: 10.1177/089033449901500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennis CL, Faux S. Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22(5):399–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199910)22:5<399::AID-NUR6>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis CL. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: psychometric assessment of the short form. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(6):734–44. doi: 10.1177/0884217503258459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galipeau R, Baillot A, Trottier A, Lemire L. Effectiveness of interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and perceived insufficient milk supply: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(3):e12607. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghazanfarpour M, Afiat M, Babakhanian M, Akrami FS, Kargarfard L, Dizavandi FR, et al. A systematic review of psychometric properties of breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form (BSES-SF) Int J Pediatr. 2018;6(12):8620. doi: 10.22038/ijp.2018.33254.2935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrestha SD, Pradhan R, Tran TD, Gualano RC, Fisher JRW. Reliability and validity of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) for detecting perinatal common mental disorders (PCMDs) among women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:72. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0859-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirza I, Jenkins R. BMJ. 2004;328(7443):794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherer M, Maddux JE, Mercandante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, Rogers RW. The self-efficacy scale: construction and validation. Psychological Reports. 1982;51(2):663–71. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chipojola R, Dennis C, Kuo S. Psychometric assessment of the paternal breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: a confirmatory factor analysis of Malawian fathers. J Hum Lact. 2022;38(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennis CL, Brennenstuhl S, Abbass-Dick J. Measuring paternal breastfeeding self-efficacy: a psychometric evaluation of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale–short form among fathers. Midwifery. 2018;64(March):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Küçükoğlu S, Sezer H, Dennis CL. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the paternal breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form for fathers. Midwifery. 2023;116(103513). 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103513 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Tokat MA, Semra E, Hulya O, Meryem OH. Psychometric assessment of Turkish modified breastfeeding self-efficacy scale for mothers of preterm infants. J Organ Behav. 2020;1(1):29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler BJ, Dennis CL. Psychometric testing of the modified breastfeeding self-efficacy scale (short form) among mothers of ill or preterm infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neontal Nurs. 2013;42(1):70–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Guo L, Shen Z. Psychometric properties of the modified breastfeeding self-efficacy scale–short form (BSES-SF) among Chinese mothers of preterm infants. Midwifery. 2020;91:102834. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Handayani L, Kosnin AMD, Jiar YK, Solikhah G. Translation and validation of breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form (BSES-SF) into Indonesian: a pilot study. Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat (Journal of Public Health) 2013;7(1):21–6. doi: 10.12928/kesmas.v7i1.1023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mituki D, Tuitoek P, Varpolatai A, Taabu I. Translation and validation of the breast feeding self-efficacy scale into the Kiswahili language in resource restricted setting in Thika-Kenya. GJMEDPH. 2017;61(3):1-9.

- 26.Creedy DK, Dennis CL, Blyth R, Moyle W, Pratt J, De Vries SM. Psychometric characteristics of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: data from an Australian sample. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(2):143–52. doi: 10.1002/nur.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Husin H, Isa ZM, Ariffin R, Rahman SA, Ghazi HF. The Malay version of antenatal and postnatal breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: reliability and validity assessment. Malaysian Health Med. 2017;17(2):62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amini P, Omani-Samani R, Sepidarkish M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Hosseini M, Maroufizadeh S. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form (BSES-SF): a validation study in Iranian mothers. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandhi A, Dennis CL, Kuo SY. Psychometric assessment of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form among Indonesian mothers. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(8):1520–8. doi: 10.1177/10547738221112756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai X, Dennis CL. Translation and validation of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale into Chinese. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2003;48(5):350–6. doi: 10.1016/S1526-9523(03)00283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eksioglu AB, Ceber E. Translation and validation of the breast-feeding self-efficacy scale into Turkish. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):e246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molina Torres MM, Torres RRD, Rodríguez AMP, Dennis CL. Translation and validation of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale into Spanish: data from a Puerto Rican population. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(1):35–42. doi: 10.1177/0890334402239732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oriá MOB, Ximenes LB, de Almeida PC, Glick DF, Dennis CL. Psychometric assessment of the Brazilian version of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale. Public Health Nurs. 2009;26(6):574–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asgarian A, Hashemi M, Pournikoo M, Mirazimi TS, Zamanian H, Amini-Tehrani M. Translation, validation, and psychometric properties of breastfeeding self-efficacy scale—short form among Iranian women. J Hum Lact. 2020;36(2):227–35. doi: 10.1177/0890334419883572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balaguer-Martínez JV, García-Pérez R, Gallego-Iborra A, Sánchez-Almeida E, Sánchez-Díaz MD, Ciriza-Barea E. Predictive capacity for breastfeeding and determination of the best cut-off point for the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition). 2022;96(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anpede.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu S, Garg S, Sharma A, Arora E, Singh M. The Hindi version of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: reliability and validity assessment. Indian J of Community Med. 2020;45(1):348–52. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_378_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boateng GO, Martin SL, Tuthill EL, Collins SM, Dennis CL, Natamba BK, et al. Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale to assess exclusive breastfeeding. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2217-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandão S, Mendonça D, Dias CC, Pinto TM, Dennis CL, Figueiredo B. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: psychometric characteristics in Portuguese pregnant women. Midwifery. 2018;66:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dennis CL, Heaman M, Mossman M. Psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form among adolescents. Journal of Adolesc Health. 2011;49(3):265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dodt RCM, Ximenes LB, Almeida PC, Batista Oriá MO, Dennis CL. Psychometric and maternal sociodemographic assessment of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale - short form in a Brazilian sample. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2012;2(3):66–73. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v2n3p66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.dos Santos LMD, Silveira Rocha R, Lopes Chaves AF, Dodou HD, Pimentel Castelo AR, Rodrigues Feitoza S, et al. Application and validation of breastfeeding self-efficacy scale – short form BSES - SF in adolescent mothers. Int Arch Med. 2016 doi: 10.3823/2078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerhardsson E, Nyqvist KH, Mattsson E, Volgsten H, Hildingsson I, Funkquist EL. The Swedish version of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: reliability and validity assessment. J Hum Lact. 2014;30(3):340–5. doi: 10.1177/0890334414523836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gregory A, Penrose K, Morrison C, Dennis CL, MacArthur C. Psychometric properties of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale- short form in an ethnically diverse U.K. sample. Public Health Nurs. 2008;25(3):278–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]