Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia and lacks highly effective treatments. Tau-based therapies hold promise. Tau reduction prevents amyloid-β–induced dysfunction in preclinical models of AD and also prevents amyloid-β–independent dysfunction in diverse disease models, especially those with network hyperexcitability, suggesting that strategies exploiting the mechanisms underlying Tau reduction may extend beyond AD. Tau binds several SH3 domain–containing proteins implicated in AD via its central proline-rich domain. We previously used a peptide inhibitor to demonstrate that blocking Tau interactions with SH3 domain–containing proteins ameliorates amyloid-β–induced dysfunction. Here, we identify a top hit from high-throughput screening for small molecules that inhibit Tau-FynSH3 interactions and describe its optimization with medicinal chemistry. The resulting lead compound is a potent cell-permeable Tau-SH3 interaction inhibitor that binds Tau and prevents amyloid-β–induced dysfunction, including network hyperexcitability. These data support the potential of using small molecule Tau-SH3 interaction inhibitors as a novel therapeutic approach to AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer, Tau, Drug development, SH3, Hyperexcitability

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia worldwide and age is the greatest risk factor, so its impact is increasing dramatically as the global population ages. Key evidence providing a mechanistic link between amyloid-β (Aβ) and Tau, the two proteins most implicated by AD pathology, was that primary neurons from Tau knockout mice are protected from Aβ-induced neurite degeneration [1]. This protective effective of Tau reduction translated to mouse models of AD [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]], preventing both cognitive deficits and network hyperexcitability without affecting Aβ plaque load, indicating that Tau is a key downstream regulator of Aβ toxicity. These findings demonstrate that targeting Tau could be highly effective for preventing Aβ-induced neuronal dysfunction. Studies of Tau reduction suggest that its beneficial effects may even extend beyond AD. Tau reduction confers resistance to hyperexcitability and seizures induced by Aβ [3,4] and also induces resistance to hyperexcitability outside the context of Aβ, with protective effects against hyperexcitability in models of epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and autism spectrum disorder [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Thus, therapies harnessing the mechanisms underlying Tau reduction may be beneficial in multiple neurological conditions.

Diverse evidence suggests that Tau's interactions with proteins containing Src homology 3 (SH3) protein-protein interaction domains are important for Aβ-induced pathophysiology. One extensively studied Tau-SH3 interaction is Tau's interaction with Fyn kinase. Fyn's SH3 domain directly binds Tau's proline-rich domain, and the affinity of their interaction is increased when Tau is hyperphosphorylated or contains disease-associated mutations [3,16,17]. Disease-associated mutant Tau also promotes trapping of Fyn within dendrites where it is locked in an activated state [18]. Fyn levels are increased in AD brain [19,20] and Aβ increases Fyn levels at the synapse and activates its kinase activity [3]. Tau reduction [1,2,21] and Fyn reduction [22,23] produce convergent phenotypes, each protecting against Aβ both in vivo and in cultured neurons. Tau reduction also reduces Fyn levels at the synapse, which could counteract the synaptic increases in AD models [3]. Additionally, Fyn overexpression exacerbates cognitive deficits in an AD mouse model, and these Fyn-mediated deficits are ameliorated by Tau reduction [4]. Finally, a truncated form of Tau, which binds Fyn but prevents its dendritic localization, prevents cognitive deficits and network hyperexcitability in an AD mouse model [3].

Beyond Fyn, there are multiple SH3 domain–containing proteins implicated in AD that bind Tau, such as AD risk factor BIN1, which also controls network hyperexcitability [24]. Tau may act postsynaptically as a scaffold for its interactors, permitting Aβ to transduce toxic signaling into neurons. Thus, reducing levels of Tau or its binding partners may be beneficial because of reduced interaction between them, so we hypothesize that inhibiting Tau-SH3 interactions will reduce Aβ-induced neuronal dysfunction.

We recently developed a peptide inhibitor of Tau-SH3 interactions to directly test that hypothesis [21]. We used two high-content measures of Aβ toxicity in primary neurons and a proximity ligation assay to measure Tau-Fyn binding. We found that the peptide inhibits endogenous Tau-Fyn interaction in neurons and ameliorates Aβ toxicity [21], validating the Tau-Fyn interaction as a therapeutic target to prevent Aβ-induced dysfunction. We also developed an AlphaScreen assay for Tau-FynSH3 interaction inhibitors, used it to perform a high-throughput screen (HTS) of ∼50,000 compounds, and found several with promising drug-like properties [25].

Here, we set out to identify cell-permeable small molecules that potently inhibit Tau-SH3 interactions and determine if they ameliorate Aβ toxicity and network hyperexcitability. To do so, we identified the top HTS hit and used iterative medicinal chemistry to produce a lead compound. We then identified the lead compound's effect on Aβ-induced dysfunction, its binding partner, and whether it inhibited multiple Tau-SH3 interactions. Finally, we determined whether inhibiting Tau-SH3 interactions was sufficient to prevent Aβ-induced network hyperexcitability. Altogether, our findings support the hypothesis that inhibiting Tau-SH3 interactions is an attractive therapeutic approach to prevent Aβ-induced neuronal dysfunction and demonstrate that cell-permeable small molecules can be developed that inhibit Tau-SH3 interactions.

Methods

Primary neuron amyloid-β toxicity assays

Primary neuron cultures: All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). As before [21,24], primary rat neurons were isolated from timed-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats. Dams were euthanized with isoflurane anesthesia asphyxiation, and hippocampal tissue was isolated from E19 embryos in Hibernate E, then digested in papain for 10 min at 37 °C. Neurons were triturated into a single cell suspension in Neurobasal supplemented with B-27, l-Glutamine, and 10 % FBS, then plated in 96-well plates coated with PDL and laminin at 30,000 neurons per well in 200 μL medium or in 24-well coated plates with or without coverslips at 50,000 per well. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Twenty-four hours after plating (DIV1), two 50 % media changes with Neurobasal plus B-27 and l-Glutamine without FBS, and 5 μM cytosine β-d-arabinofuranoside was added to prevent glial proliferation. 50 % media changes were performed at DIV7 and DIV14 with serum-free supplemented Neurobasal, and experiments were started at DIV19.

Aβ oligomer preparation: As before [21], lyophilized recombinant Aβ42 was dissolved in HFIP, dried overnight, and then stored at −20 °C until oligomerization. To oligomerize, Aβ was dissolved in DMSO to 1 mM, then diluted to 100 μM in PBS, then sonicated and left on ice for 24 h. Immediately prior to use, Aβ was centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 14,000×g. Vehicle was prepared as well in identical fashion except lacking the Aβ peptide.

Aβ toxicity assays: The modified MTT and MAP2 assays were adapted from our recent study [21]. Briefly, at DIV19, media on the neurons was reduced to 100 μL, then compound was added to final concentration of 0 μM, 0.3 μM, 3 μM, or 15 μM with even amounts of DMSO. After 90-min pretreatment with compound, 2.5 μM Aβ was added.

The modified MTT assay was performed 24 h after Aβ application. 100 μM MTT was applied to neurons and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Media was removed, then replaced with 15 μL 1.6 % Tween20 in PBS and incubated on a shaker at 100 rpm for 5 min. The Tween was then removed and transferred to a 384-well clear-bottom plate and replaced with 15 μL isopropanol. Plates were again agitated for 5 min at RT, then isopropanol was transferred to the 384-well plate. Absorbance was then read at 590 nm on a plate reader, with 660 nm used as a reference. The ratio of Tween soluble MTT to isopropanol soluble (Tween-insoluble) MTT was calculated for each sample, then normalized to the vehicle group average.

For the MAP2 ICC assay, neurons were fixed in 4 % PFA and 4 % sucrose at 37 °C for 30 min, then washed 3 × 5 min in PBS. Neurons were blocked (5 % normal horse serum, 5 % normal goat serum, 1 % bovine serum albumin, and 0.5 % saponin in 1xPBS) for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with MAP2 (1:5000) antibody. Neurons were washed 3 × 5 min in rinse buffer (0.5 % normal horse serum, 0.5 % normal goat serum, 0.05 % saponin in 1× PBS), then secondary antibody was applied for 1 h at RT. Neurons were washed 2 × 5 min, then 3 × 5 min in PBS, and stored in the dark at 4 °C until imaging. Images were taken on an Operetta high-content imager. Intact neurite length was measured in an unbiased, automated manner using Harmony software, averaged from four images from each well. For analysis, total intact neurite length for each well from each condition was normalized to the vehicle group average.

Oral administration of drugs

Compounds were sent to Pharmaron to determine if they were blood–brain barrier permeable. Compounds were formulated to 1 mg/mL in 10 % NMP, 60 % PEG400, 30 % saline, then male CD1 mice were treated PO at 5 mg/kg. Brain and plasma concentrations were measured using HPLC-MS at 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h post-treatment.

Proximity ligation assays

Endogenous Tau-Fyn PLA in primary neurons: All PLA protocols were adapted from our recent study [21].

For the endogenous Tau-Fyn PLA, we grew neurons on coverslips as described above to DIV20, then treated with SRI-42667 or vehicle, and fixed with PFA 24 h later. We used Dako Tau (1:1000) and Fyn15 (1:250) antibodies. Duolink In Situ Fluorescence kit was used for PLA. Briefly, coverslips with fixed cells were permeabilized for 10 min in 0.25 % Triton X-100, then blocked in 5 % NGS in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody in 1 % NGS, then washed 3 × 5 min in PBS. Coverslips were then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in PLA probes (Anti-Mouse minus, Anti-Rabbit plus). Coverslips were washed in Wash Buffer A at room temperature 2 × 5 min, then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in Ligation Buffer, then washed 2 × 2 min in Wash Buffer A. Coverslips were incubated in Amplification Buffer for 100 min at 37 °C, then washed with Wash Buffer B 2 × 10 min, 0.01 Wash Buffer B for 1 min, then PBS for 5 min, then mounted in Prolong Diamond with DAPI. After setting, 5–7 images of each coverslip were taken on an epifluorescent microscope. To quantify PLA puncta, PLA fluorescence was thresholded, then ImageJ particle analyzer was run, specifying size and circularity to exclude any non-punctate signal. Quantified values were then normalized to values for vehicle-treated slides from that experiment. Experimenters were blinded during image acquisition and analysis.

Tau-Fyn PLA screening in HEK-293 cells: For Tau-Fyn PLA in HEK-293 cells, we used the same plasmids as before [21]: human 4R2N Tau with an N-terminal mKate2 tag in a pcDNA3.1 vector and human Fyn with an N-terminal Myc tag in a pCMV-Sport6 vector grown in Stellar E. coli. HEK-293 cells were plated on coverslips coated with PDL and laminin in a 24-well plate in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % PenStrep. Cells were transfected with 125 ng of Tau-mKate2 and Fyn plasmids with 1.5 μL Fugene in plain DMEM. After 24 h, compound was applied at 15 μM. Twenty-four hours after application, cells were fixed. PLA protocol was the same as above except for different primary antibodies (Tau5 1:500, Fyn3 1:250). After image acquisition, PLA density was calculated as PLA puncta (as above) divided by cell area to account for differences in confluency. Cell area was defined with ImageJ as %Area after theresholding Tau-mKate2 fluorescence because it filled the cells evenly. Puncta/cell area was then normalized to vehicle-treated slides from that experiment.

Tau-Flag PLA for Tau-SH3 interactions: To clone the SH3 constructs, we added a C-terminal Flag tag to the Tau construct using PCR, then replaced the Tau sequence with the desired SH3 domain using In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Takara Bio). We then added an N-terminal GST tag to help expression using In-Fusion, resulting in GST-SH3-Flag plasmids. As a negative control, we used restriction enzymes to remove the FynSH3 from the FynSH3 construct, resulting in GST-Flag. We confirmed all sequences with Sanger sequencing and verified expression in HEK-293 cells by Western blot and immunocytochemistry. Plating and experimental timeline was the same as above. Cells were transfected with 125 ng of Tau-mKate2 and 500 ng SH3 plasmid with 1.5 μL Fugene. SRI-42667 was applied to final concentration 15 μM. For Tau-SH3 PLA, we used Dako Tau (1:1000) and Flag (1:1000) primary antibodies.

Tau-tubulin PLA: Untransfected HEK-293 cells were used to measure endogenous Tau-tubulin interaction. Cells were grown for 48 h before applying 15 μM SRI-42667 for 24 h. Cells were fixed and PLA was run as above except with Dako Tau (1:1000) and α-tubulin (1:2000) primary antibodies.

Western blot

Like before [21], at DIV13, neurons were treated with 15 μM SRI-42667 or Vehicle. 24 h later, cells were harvested in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1 % SDS, 0.1 % Triton-X-100 and 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate) and centrifuged to remove cellular debris. Samples were diluted in LDS and reducing agent and heated at 70 °C for 10 min. Samples were run on 4–12 % bis-tris gels in MOPS buffer with 5 μg protein per well, determined by a Bradford assay, and then transferred to a PDVF membrane. Membrane was blocked for 1 h in 50 % Odyssey blocking buffer then probed overnight with Fyn3 (1:1000) antibody at 4 °C. Membrane was washed 3× in TBST, then incubated for 1 h at RT in IRDye 700 or 800 conjugated secondary and scanned on an Odyssey Scanner. Images were quantified in ImageJ. After probing for GAPDH (1:5000), the blot was stripped with Restore PLUS Western Blot Stripping Buffer for 30 min at room temperature, washed in TBST, and probed for DAKO Tau (1:10,000).

Kinase panel

Compounds were dissolved in 100 % DMSO to 1000× testing concentration: 3 mM for SRI-42667 and SRI-43400 and 30 μM for saracatinib/AZD0530. Compounds were tested on Eurofins DiscoverX ScanEDGE panel, which tested kinase activity of 97 kinases. Since Fyn was not included in that panel, we also completed a custom panel for Fyn kinase activity. Activity was defined as compound leading to <35 % of control activity to control for multiple comparisons. Interaction maps were generated with the TREEspot tool by DiscoverX.

Protein purification

Human Fyn-SH3 domain with GST-tag at the N-terminus and a Strep-tag II (WSHPQFES) at the C-terminus (GST-Fyn-SH3-Strep) was cloned into pPR-IBA1 vector (IBA Lifesciences) [25]. Codon-optimized human 4R2N Tau for E. coli expression with a Strep-tag II at the C-terminus (His-Tau-Strep) was cloned into pET-28a(+) vector (Novagen). The constructs were transformed into E. coli BL-21(DE3) competent cells (Novagen). For GST-Fyn-SH3-Strep purification, a single colony was inoculated in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37 °C overnight. 10 mL cell culture was added into 500 mL LB medium and cultured at 37 °C. 0.5 mM Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added into the culture when OD600 reached 0.7. Cells were further cultured at 25 °C for 4 h and harvested. Cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP) with 1 tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitors (ThermoFisher) and 1 mg/mL lysozyme. Cells were disrupted by sonication and debris was removed by centrifugation at 9500 rpm for 1 h. Supernatant was loaded onto a glutathione-sepharose column (Cytiva). The column was washed in lysis buffer and protein eluted in lysis buffer containing 25 mM reduced glutathione. For His-Tau-Strep protein purification, cells were inoculated in LB broth medium and cultured at 37 °C overnight. A 10 mL overnight culture was added to 500 mL of auto-induction medium [26] and cells were cultured at 37 °C for about 5 h. The temperature was lowered to 18 °C and cells were cultured overnight. Cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer with 20 mM imidazole, protease inhibitors and lysozyme. Cells were disrupted by sonication and cell pellets were spun down at 9500 rpm for 1 h. Supernatant was loaded onto Ni-NTA column (Cytiva) and the column was washed in lysis buffer with 20 mM imidazole. His-Tau-Strep protein was eluted in lysis buffer containing 400 mM imidazole. Both eluted GST-Fyn-SH3-Strep and His-Tau-Strep protein solutions were passed through G-25 desalting column (Cytiva) with lysis buffer and loaded onto high capacity Strep-Tactin column (IBA Lifesciences). The columns were washed in Buffer W (IBA Life sciences) and proteins were eluted in Buffer E (IBA life sciences). The eluted proteins were passed through G-25 desalting column again. Both GST-Fyn-Strep and His-Tau-Strep proteins were concentrated and diluted 1:1 in ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant for storage at −80 °C.

AlphaScreen preincubation assay

AlphaScreen was conducted with 10 μg/mL of glutathione donor beads (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and nickel chelate acceptor beads (PerkinElmer) in 10 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.0), 1 mM TCEP, 0.02 % casein, and 0.1 % Tween-20. Compounds were plated first followed by addition of one the proteins at 600 nM and incubation for 30 min. The second protein was added and incubated for 30 min, then the beads were added simultaneously and the final mixture was incubated for 2 h. Experiments were conducted in 384-well plates (6007290; PerkinElmer) and results were read on a PHERAstar plate reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Purified full-length Tau and FynSH3 were dialyzed into 20 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 with Slide-A-Lyzer G2 Dialysis Cassettes with 10K MWCO (ThermoFisher #87729). Cassettes were hydrated in buffer for 2 min before purified protein was injected using an 18-gauge needle. Cassettes were placed in 500 mL buffer with a stir bar and stirred for 2 h. Buffer was discarded and replaced for two more hours, then replaced again and the samples were dialyzed overnight, all at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured on a Nanodrop2000 (ThermoFisher) based on absorbance at 280 nm. Before ITC, solutions were brought to 5 % DMSO to match amount needed for SRI-42667 preparation.

ITC experiments were performed on an Auto-iTC200 system (Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA). ITC sample cell contained ∼120 μM full-length Tau, FynSH3, or Tau-PxxP5/6 (titrand), and the syringe contained 1 mM SRI-42667 (titrant). Each titration experiment consisted of 16 injections of 2.5 μL of titrant into titrand at 25 °C. Background mixing heat was determined from injections of titrant into the same buffer without titrand. Data analysis was performed using the built-in analysis module in Origin 7 provided by the ITC manufacturer. The normalized titration heat was fitted to a “one set of sites” model to determine the best-fit binding parameters.

Molecular docking and dynamics

Fyn structure and ligand preparation: A 2.6 Å crystal structure of human FynSH2/SH3 domains (PDBID: 1G83) [27] was energy minimized by steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient in AMBER18 using the ff14sb force field in preparation for virtual docking. The minimized structure of Fyn was loaded into AutoDockTools, where nonpolar hydrogen atoms, water molecules, and counterions were removed and Kollman charges appended. This prepared Fyn was then output in PDBQT format for molecular docking. We used a model of synthetic VSL12 peptide (PDBID: 4EIK) as a positive control analogue for the known PxxP binding site on FynSH3.

OpenBabel software was used to generate 3D SDF structures of SRI-42667 for docking. The conformationally randomized 3D structures were loaded into AutoDockTools, where nonpolar hydrogen atoms, water molecules, and counterions were removed and Gasteiger charges added to convert from SDF to PDBQT format. AutoDock Vina molecular docking software was run to predict top binding modes for SRI-42667 bound to FynSH2/SH3. Docking was performed in a grid box centered on, and fully containing, the entire SH3 domain with an exhaustiveness setting of 32. In molecular docking, SRI-42667's rotatable bonds were treated as flexible while the Fyn model was rigid. Docked conformations for SRI-42667 were ranked according to the calculated binding energy (in kcal/mol) from Vina.

Molecular dynamics simulations: The top conformation of SRI-42667 docked to Fyn was used for MD simulations in AMBER18 [28], using the ff14SB force field [29] to parameterize Fyn and VSL12 and the generalized AMBER force field [30] for SRI-42667. MD simulations were performed in a periodic box with 2 nm of solvent between the protein edge and the box boundary to reduce periodicity artifacts. The periodic box was filled with TIP3P computational water and 150 mM NaCl added at random positions to approximate physiologic conditions. Additional Cl− ions were added to neutralize the protein charge. We first performed steepest descent minimization of the solvent water with the protein, counterions, and ligand molecule restrained. We then equilibrated the solvent with the protein, counterions, and ligand molecule restrained at constant number-pressure-temperature at 50 K and 1 bar for 20 ps. The system was heated via 10 ps constant number-volume-temperature MD simulations at 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 K. MD production simulations of 150 ns at 300 K and 1 bar were performed. For all MD simulations, SHAKE constraints with relative tolerance of 1 × 10−5 were used on all hydrogen–heavy atom bonds to permit time steps of 2 fs. Electrostatic interactions were calculated by the particle-mesh Ewald method. Lennard-Jones cutoffs were set at 1.0 nm. To determine the initial simulation time needed to reach equilibration, RMSD was calculated over the trajectory using the cpptraj program of AMBER 19.05 [31] and its rate of stabilization was compared to stabilization of binding free energy. Hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bond formations, and electrostatic interactions between Fyn and the docked molecules were analyzed using PyMol [32] and trajectories were rendered for visualization using VMD software. During the unbiased docking of SRI-42667 to Fyn, the top pose for SRI-42667 that we selected was in the same binding pocket that the PxxP motif of VSL12 uses when binding FynSH3. This pose was used as our starting point for the MD run for SRI-42667. We also ran the VSL12-FynSH3 binding with the same parameters as a positive control. Virtual docking and MD simulations were performed on the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Cheaha Supercluster using 32 conventional 2.5 GHz Intel Xeon E5 series cores in parallel with OpenMPI v1.10.2.

Multi-electrode arrays

As in a prior study [24], 30,000 neurons were plated per well in a 48-well MEA plate. At DIV 5 and DIV 9, 50 % media changes were completed with BrainPhys supplemented with SM1 and l-Glutamine. Recording and treatments were completed DIV13. A 20-min baseline recording was done using Axion AxIS Navigator software. Neurons were then treated with SRI-42667 for 1 h, then 500 nM oligomeric Aβ was applied and neurons were returned to the incubator for 4 h before being recorded for 20 more minutes. All recordings were dual filtered at 0.01 and 5000 Hz Butterworth filters. Action potentials were set using an adaptive threshold >6 standard deviations from the electrode's mean signal. Waveforms were exported from AxIS Navigator to Offline Sorter, where individual units were identified and sorted. Analysis of action potential frequency was completed in NeuroExplorer. Mean baseline frequency for each well was calculated from unit frequencies, then each unit in the post-treatment recording was normalized to the baseline average of its well. Data were log transformed before analysis. Researchers were blind to experimental conditions during analysis.

Statistics

Statistics and sample sizes are described in each figure legend. Except where noted, t-test or ANOVA was used, usually with main effects of drug and Aβ for 2-way ANOVA. Data were organized in Microsoft Excel and analyses were completed in GraphPad Prism 9. One-tailed t-test was used for each Tau-SH3 interaction in Fig. 5, as we had evidence that SRI-42667 would decrease rather than increase Tau-SH3 interactions. For all, α was 0.05. Data were presented as mean ± SEM.

Fig. 5.

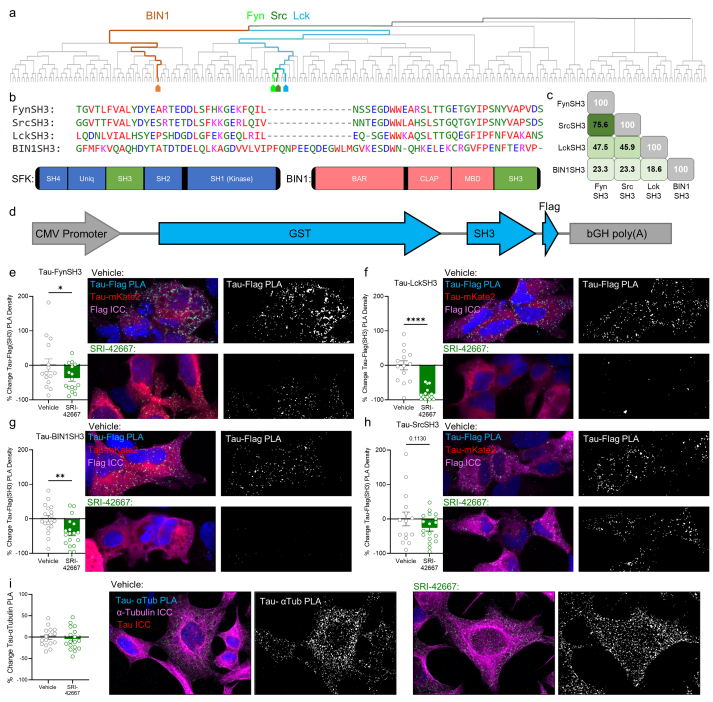

SRI-42667 is a selective Tau-SH3 interaction inhibitor.a: Phylogenetic tree of the 306 SH3 domains in 225 genes in the human genome identified in the UniProt database, produced by ClustalOmega. SFKs Fyn (light green), Src (dark green), and Lck (blue) are closely related, while BIN1 (brown) is distantly related. b: Multiple sequence alignment of the SH3 domains examined. c: Percent identity matrix of the SH3 domains. d: Diagram of plasmids expressing FynSH3, SrcSH3, LckSH3, and BIN1SH3. e: SRI-42667 inhibits Tau-FynSH3 interaction 37 % (n = 16 per group, ∗p = 0.04). f: SRI-42667 inhibits Tau-LckSH3 interaction (n = 14–15 per group, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). g: SRI-42667 inhibits Tau-BIN1SH3 interaction (n = 18 per group, p = 0.003). h: SRI-42667 does not inhibit Tau-SrcSH3 interaction (n = 15–18 per group, p = 0.11). i: SRI-42667 does not inhibit Tau-tubulin interaction (n = 16–17 per group, p = 0.30). e-i: N = 3 unique passages of HEK-293 cells, one-tailed t-test. Data displayed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Prioritization of Tau-FynSH3 inhibitor hits from HTS

We previously screened ∼50,000 compounds from the Enamine and Southern Research libraries to identify Tau-FynSH3 interaction inhibitors using an AlphaScreen assay [25]. We selected compounds that were >3 standard deviations above mean inhibition, yielding 1852 hits (Fig. 1a). We further screened those hits using four assays: a repeat Tau-FynSH3 AlphaScreen with fresh compound, a counterscreen with covalently linked GST-His to identify compounds that nonspecifically inhibited AlphaScreen chemistry, and two toxicity assays in LL47 and THP-1 cells. We advanced compounds showing >50 % inhibition in the repeat Tau-FynSH3 AlphaScreen that also had IC50 in the counterscreen and EC50 in both toxicity assays >2-fold higher than the IC50 for Tau-FynSH3. 64 compounds met all four criteria, with many displaying no activity in the counterscreen and toxicity assays. These 64 compounds were then rerun through the Tau-FynSH3 AlphaScreen in triplicate and 39 compounds with IC50 < 100 μM were advanced. These 39 compounds were tested in a live-cell BRET assay to measure Tau-Fyn interaction in cells. Seven compounds were active by BRET, five of which had promising modifiable structures [25].

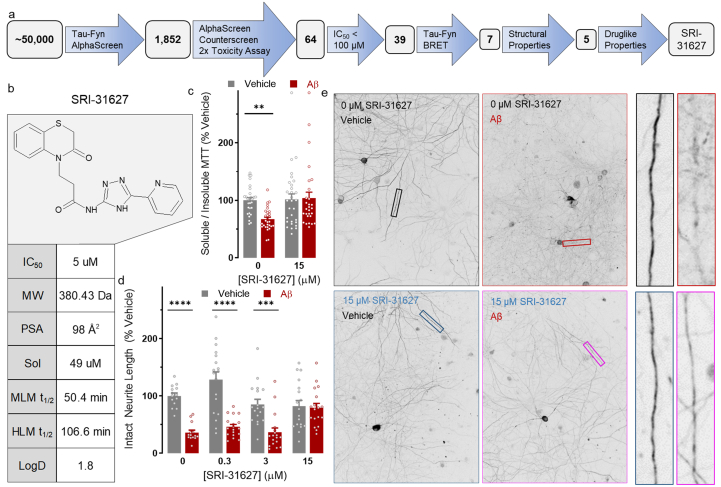

Fig. 1.

Top hit compound SRI-31627 prevents Aβ toxicity.a: Workflow for identification of SRI-31627 as a top hit from a HTS of ∼50,000 compounds. b: SRI-31627 structure and druglike properties. c: 15 μM SRI-31627 ameliorates Aβ toxicity in a modified MTT assay (n = 28–30 wells per group from N = 3 dissections. 2-way ANOVA main effect of Aβ p = 0.043, F(1,111) = 4.20, ∗∗p < 0.01 by Sidak posthoc). Gray bars are vehicle control and red bars are Aβ-treated neurons. d: 15 μM SRI-31627 ameliorates Aβ-induced neurite degeneration (n = 14–18 wells per group from N = 2 dissections. 2-way ANOVA main effect of Aβ p < 0.0001, F(1,128) = 66.65, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by Sidak posthoc). Gray bars are vehicle control and red bars are Aβ-treated neurons. e: Representative images of MAP2-stained neurites for neurite degeneration assay. Data displayed as Mean ± SEM.

We then completed a computational analysis of the top five hits to assess the physical attributes of the compounds emerging from the HTS. Our target profile for drug-like properties included evaluation of molecular weight (MW), total polar surface area (PSA, the surface sum of all polar atoms on the molecule), solubility, metabolic stability, and partition coefficient (LogD). In general, we targeted MW < 500 kDa and PSA <70 Å2, which generally allows for blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Compounds with PSA >100 Å2 are generally poor at permeating cell membranes. We targeted solubility >10 μM at pH 7.4 and 40–60 % of compound remaining after 60 min of incubation in mouse or human liver microsomes (an indicator of compound stability after first-pass metabolism). LogD is the log of the ratio of concentrations of a compound in two immiscible solvents at equilibrium. We targeted values ranging from 2 to 4, typical for CNS drugs. Based on these criteria, we selected SRI-31627 (1) as our top hit for optimization. SRI-31627 had an IC50 of 5.0 μM in the Tau-FynSH3 AlphaScreen and demonstrated acceptable drug-like properties, with a MW of 380.43 kDa, PSA of 96 Å2, solubility of 49 μM, metabolic stability in liver microsomes (Mouse t1/2 = 50.4 min; Human t1/2 = 106.6 min), and LogD of 1.8 (Fig. 1b).

We next tested whether SRI-31627 was biologically active in assays with relevance to AD. We used two assays of Aβ toxicity in primary neurons with which we had previously identified protective effects of a Tau-SH3 inhibitor peptide [21]. SRI-31627 prevented Aβ-induced membrane trafficking dysfunction using a modified MTT assay (Fig. 1c) and prevented Aβ-induced neurite degeneration using a MAP2 ICC–based neurite measuring algorithm (Fig. 1d and e). Altogether, these results support SRI-31627 as a promising compound with micromolar potency as a Tau-Fyn interaction inhibitor, reasonable drug-like properties, and biological activity in reducing Aβ toxicity.

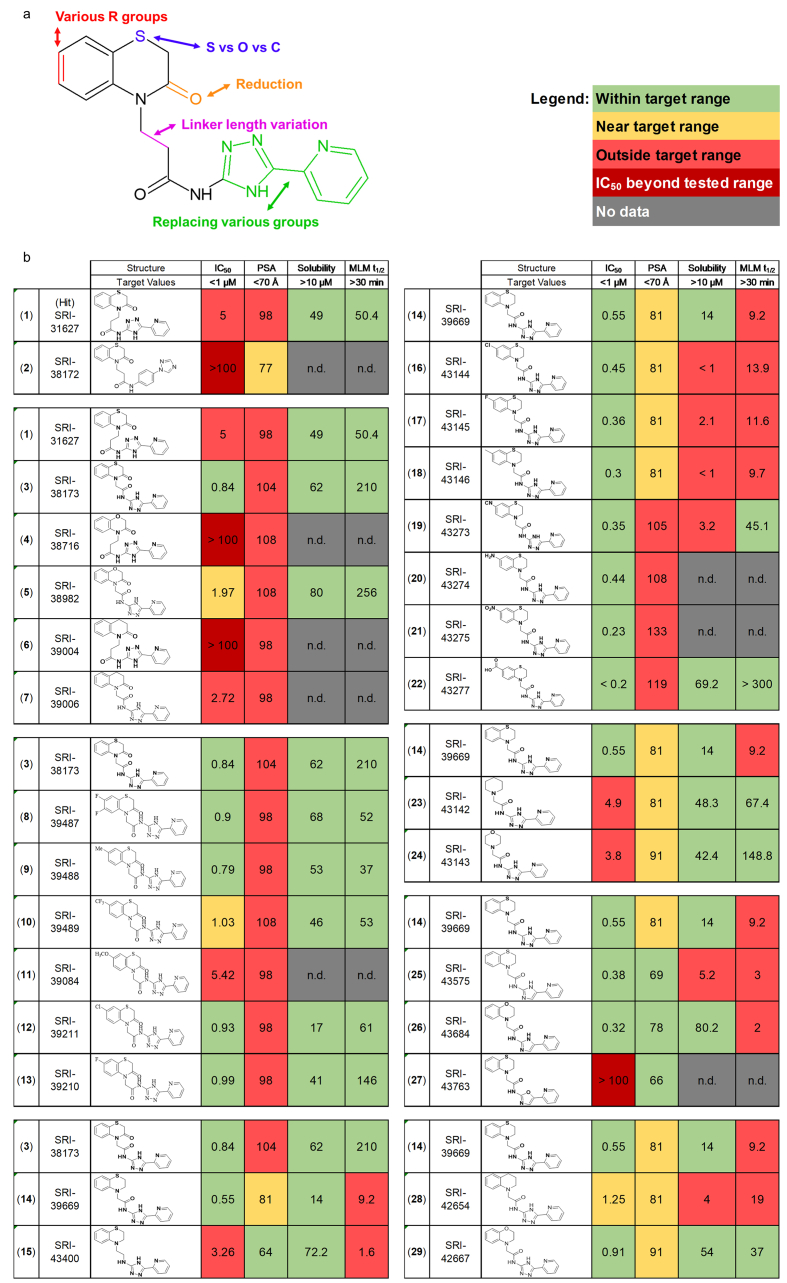

Medicinal chemistry optimization of SRI-31627

After identifying SRI-31627 as the most promising HTS hit and verifying its biological activity, we began a medicinal chemistry optimization program. To generate structure–activity relationships and to improve overall drug-like properties, we designed, synthesized, and tested 92 analogs with diverse modifications of SRI-31627 for Tau-FynSH3 inhibitory activity in the AlphaScreen, of which 29 are shown in Fig. 2. We identified several moieties in SRI-31627 to modify (Fig. 2a): the 5-(pyridin-2-yl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine moiety was replaced with various groups (green in Fig. 2a), the ethyl linker was replaced with a methylene linker (magenta), the ring sulfur was replaced with oxygen and carbon (blue), the cyclic ketone was removed (orange), and various aromatic R groups were introduced in the left-hand phenyl ring (red).

Fig. 2.

Development of derivatives of SRI-31627 with improved drug-like properties.a: Structure of SRI-31627 (1) with modified moieties highlighted. b: Structure and drug-like properties of 28 derivatives of SRI-31627 detailing the medicinal chemistry pipeline resulting in lead SRI-42667.

We first replaced the 5-(pyridine-2-yl)-4H-1,2,4-triazole moiety (green) of SRI-31627 with substituted aryl, heteroaryl or biphenyl rings. These modifications abolished all AlphaScreen activity, as shown for SRI-38172 (2) (Fig. 2b), demonstrating the importance of that moiety.

We next determined if the ethyl linker (magenta) could be shortened and if replacing the ring sulfur (blue) with carbon or oxygen improved drug-like properties. We developed five new compounds (3–7), with all possible combinations of these modifications. Modification of the ethyl linker of SRI-31627 to a methylene linker gave SRI-38173 (3), which showed a five-fold improvement in activity, along with improved solubility and metabolic stability in liver microsomes. However, there was no activity with an ethyl linker with either oxygen or carbon in the ring (4,6). With a methylene linker, there was activity with both oxygen (5) and carbon (7), though less than with sulfur. Solubility and metabolic stability, however, were improved by the ring oxygen. Thus, a methylene linker improves activity and a ring sulfur has the highest AlphaScreen activity (0.84 μM). From these modifications, we identified SRI-38173, which in addition to a five-fold improvement in activity in the Tau-FynSH3 AlphaScreen also had better solubility and metabolic stability than SRI-31627.

Third, we introduced various substituents such as Cl, F, CF3, and CH3 at the 6- and 7- positions of the left-hand phenyl ring (red) to create additional analogs (8-13). While none of the substitutions dramatically increased activity, several had lower PSA, an indicator of better potential brain permeability. The most interesting compound was SRI-39210 (13), with a 7-fluoro substituent, which had the lowest PSA, submicromolar IC50, and the highest metabolic stability of the daughters (MLM t1/2 = 146 min). We next empirically determined whether the PSA was sufficiently low to allow BBB permeability by orally administering SRI-39210 to mice (5 mg/kg). While we were able to detect SRI-39210 in plasma, it did not cross the BBB and was not present in brain (data not shown).

To further reduce PSA, the cyclic ketone (orange) of SRI-38173 (3) was removed, resulting in SRI-39669 (14), which showed inhibition in the AlphaScreen (IC50 = 0.55 μM) and low PSA, but had low solubility and metabolic stability. Since SRI-39669 was promising, we also made a negative control, SRI-43400 (15), with an ethyl linker that, as predicted, had six-fold lower activity. When orally administered, SRI-39669 was detected in both plasma and brain, though relatively little crossed into the brain, with a maximum brain/plasma ratio of 0.06.

We next modified SRI-39669 to optimize its other drug-like properties for further biological testing. We began by introducing various groups in the aromatic ring (red), though all resulting compounds were either insufficiently soluble (16–19) or had high PSA (19–22). We then removed the left-hand phenyl ring, which maintained low PSA and improved solubility and metabolic stability, but reduced activity 8–10-fold (23, 24). Additional modifications of the 5-(pyridin-2-yl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-amine moiety (green) yielded some analogs with improved activity, but also had reduced metabolic stability (25,26), or lost activity (27).

Finally, we replaced the ring sulfur (blue) of SRI-39669 with oxygen and carbon (28, 29). We expected that this would result in slightly less activity, but improved solubility and metabolic stability, as in the second series. As expected, analogs with oxygen and carbon in the ring were less active. The analogue with the oxygen substitution, SRI-42667 (29), had improved solubility and metabolic stability while retaining submicromolar activity. Orally administered SRI-42667 was observed in both plasma and brain with a brain/plasma ratio of 0.067, similar to SRI-39669. Though this series resulted in compounds with some ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, brain permeability of this series should be improved. In summary, we synthesized 92 analogs of SRI-31627 and identified SRI-42667 as the lead compound for further testing.

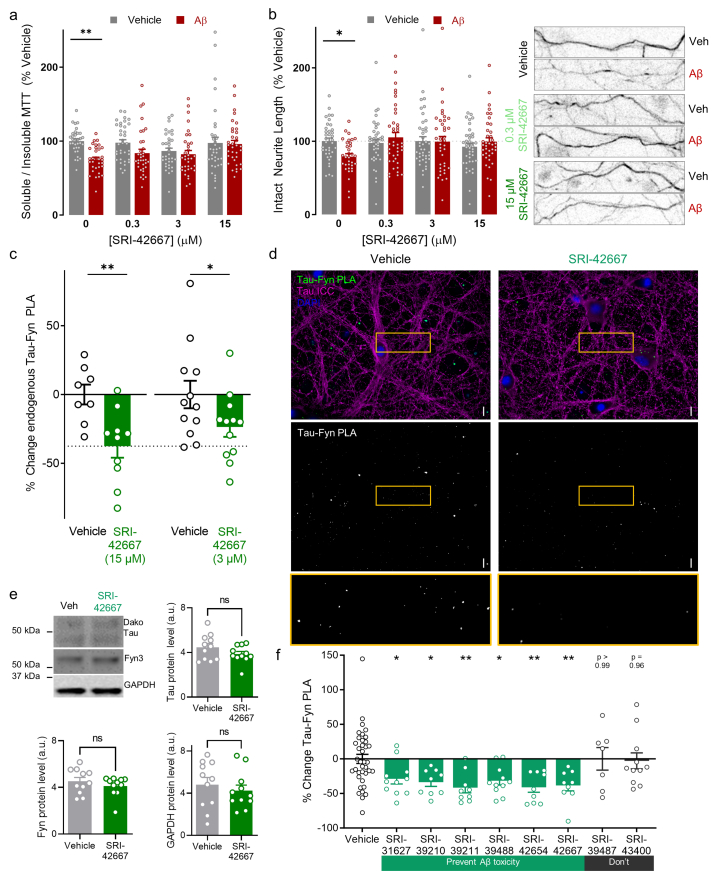

SRI-42667 blocks Aβ-induced neuronal dysfunction

We proceeded to determine whether SRI-42667 prevented Aβ toxicity using the two primary neurons assays. SRI-42667 prevented Aβ-induced membrane trafficking dysfunction in the MTT assay (Fig. 3a) and Aβ-induced neurite degeneration in the MAP2 assay (Fig. 3b), like SRI-31627 but with submicromolar potency.

Fig. 3.

Compounds that inhibit Tau-Fyn interaction in cells also ameliorate Aβ toxicity.a: SRI-42667 ameliorates Aβ toxicity (n = 32–36 wells per group from N = 3 dissections. 2-way ANOVA main effect of Aβ p = 0.0017, F(1, 268) = 10.06, ∗∗p < 0.01 by Sidak posthoc). Gray bars are vehicle control and red bars are Aβ-treated neurons. b: SRI-42667 ameliorates Aβ-induced neurite degeneration. (n = 33–42 wells per group from N = 4 dissections. 2-way ANOVA interaction p = 0.04, F(1,304) = 2.76, ∗p < 0.05 by Sidak posthoc), with representative images of MAP2-stained neurites. Gray bars are vehicle control and red bars are Aβ-treated neurons. c: Both 15 μM (n = 8–10 per group from N = 2 dissections; t-test p = 0.0046) and 3 μM (n = 12 per group from N = 2 dissections; one-tailed t-test p = 0.034) SRI-42667 reduces endogenous Tau-Fyn PLA in primary neurons. d: Representative images of endogenous Tau-Fyn PLA in primary neurons treated with 15 μM SRI-42667. Yellow box is inset on right. Scale bar = 10 μm. e: 15 μM SRI-42667 does not reduce Tau, Fyn, or GAPDH levels in primary neurons (n = 11 per group from N = 2 dissections; t-test p > 0.05). f: Compounds that prevent Aβ toxicity significantly reduce Tau-Fyn PLA while compounds that do not prevent Aβ toxicity do not reduce Tau-Fyn PLA in HEK-293 cells (n = 7–11 per group from N = 2–3 passages; ANOVA p = 0.0002, F(8,105) = 4.22, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 by Holm-Sidak posthoc). Data displayed as mean ± SEM.

We next evaluated target engagement of the Tau-Fyn interaction using a proximity ligation assay (PLA) in primary neurons. SRI-42667 inhibited endogenous Tau-Fyn interaction at both 3 μM and 15 μM (Fig. 3c and d). Importantly, SRI-42667 did not lower Tau or Fyn levels in neurons (Fig. 3e), supporting a mechanism based on true inhibition of the protein-protein interaction, not simply reduction of the interaction by lowering expression of Tau or Fyn.

Effects on Aβ toxicity associate with Tau-SH3 inhibition

To further explore the relationship between preventing Aβ toxicity and inhibiting Tau-SH3 interactions in cells, we selected eight compounds with varying druglike properties to test in cells. We tested each compound in two assays: the MTT assay in primary neurons to assess Aβ toxicity and Tau-Fyn PLA in HEK-293 cells to assess interaction inhibition. Six of these compounds inhibited Aβ toxicity (SRI-31627 (1), SRI-39210 (13), SRI-39211 (12), SRI-39488 (9), SRI-42654 (28), SRI-42667 (29)) while two did not (SRI-39487 (8), SRI-43400; (15)) (Supplementary Figure 1). Each of the compounds that ameliorated Aβ toxicity also reduced Tau-Fyn interaction in cells. On the other hand, the two compounds that did not ameliorate Aβ toxicity also did not reduce Tau-Fyn interaction in cells. These results are consistent with an association between the ability of compounds to inhibit Tau-Fyn interaction and to ameliorate Aβ toxicity.

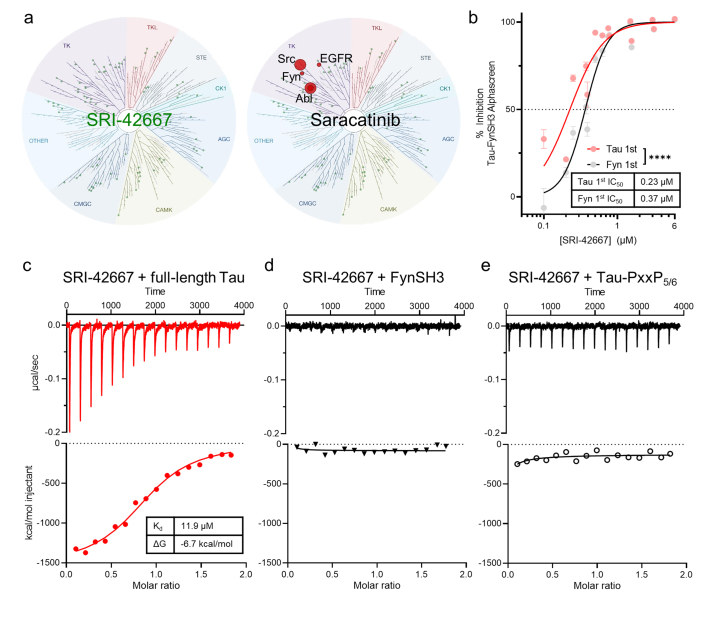

SRI-42667 binds Tau not FynSH3

Having identified SRI-42667 (29) as a novel Tau-FynSH3 interaction inhibitor that ameliorates Aβ toxicity in neurons, we explored several aspects of its mechanism of action. First, we tested whether SRI-42667 acts as a kinase inhibitor, as Fyn kinase inhibition is a potential therapeutic approach under investigation for AD [33]. At 3 μM, which is sufficient to ameliorate Aβ toxicity and inhibit Tau-SH3 interaction, SRI-42667 did not inhibit Fyn or any of the 97 kinases in the DiscoverX KINOMEscan™, while a positive control, saracatinib, inhibited several Src family kinases (SFKs) as expected (Fig. 4a, full data in Supplementary Table 1). Thus, SRI-42667's amelioration of Aβ toxicity is not due to inhibition of Fyn or other kinases and is likely due to inhibition of Tau-SH3 interactions.

Fig. 4.

Lead compound SRI-42667 binds Tau not FynSH3.a: SRI-42667 is not a kinase inhibitor while positive control SFK inhibitor saracatinib inhibits Src, Fyn, Abl, and EGFR kinase activity. b: Preincubating SRI-42667 with Tau in the Tau-FynSH3 AlphaScreen resulted in more potent inhibition than preincubating SRI-42667 with FynSH3 (n = 3 wells per group in N = 2 runs; 2-way ANOVA main effect of preincubation p < 0.0001, F(1,75) = 80.22). Data displayed as mean ± SEM. c-e: ITC reaction heat and fitting curves of SRI-42667 with full-length Tau (c), FynSH3 (d), and Tau-PxxP5/6 (e). For SRI-42667 with full-length Tau, n = 0.9, Kd = 11.9 μM, ΔG = −6.7 kcal/mol, ΔH = −1.5 kcal/mol. Results were confirmed with three independent experiments.

Next, we examined the structural basis for SRI-42667 effects, specifically whether it inhibits Tau-Fyn interaction by binding to Tau or to Fyn. Since Tau is natively unstructured and FynSH3 has a well-structured binding pocket, we initially suspected that SRI-42667 would be more likely to bind FynSH3. We tested this prediction first with molecular docking and dynamics, which showed no strong binding of SRI-42667 to FynSH3 (Supplementary Video 1), while a positive control, the PxxP-containing and Fyn-binding VSL12 peptide, did bind as expected (Supplementary Video 2). Thus, to our surprise, molecular docking and dynamics predicted that SRI-42667 does not bind FynSH3.

We next used an AlphaScreen preincubation assay, which distinguishes between compounds that bind Tau or FynSH3 because compounds show greater potency when preincubated with their binding partner than when preincubated with the other protein [25]. SRI-42667 was significantly more potent when pre-incubated with Tau than with FynSH3, further suggesting that SRI-42667 more likely binds Tau (Fig. 4b).

Finally, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to definitively quantify SRI-42667 binding to Tau and to Fyn. SRI-42667 bound full-length Tau with Kd = 11.9 μM and ΔG = −6.7 kcal/mol (Fig. 4c), while it did not bind FynSH3 (Fig. 4d). Altogether, these data demonstrate that SRI-42667 inhibits Tau-Fyn interaction by binding to Tau rather than FynSH3.

To begin addressing the location of the SRI-42667 binding site on Tau, we tested whether the compound could bind the peptide incorporating Tau's 5th/6th PxxP (amino acids 209–225), which is the primary site for Fyn interaction [17,25]. We observed no interaction between SRI-42667 and the Tau-PxxP5/6 peptide by ITC (Fig. 4e), suggesting that the compound either requires additional tertiary structural elements or allosterically inhibits the interaction by binding another region of Tau.

SRI-42667 is a selective Tau-SH3 interaction inhibitor

Since SRI-42667 (29) binds Tau, we next determined whether it inhibits other Tau-SH3 interactions besides Tau-Fyn. We identified three other SH3 domains of interest: Src-family kinases with either type A SH3 (Src) or type B SH3 (Lck) domains, and BIN1, a non-kinase SH3 domain–containing protein that is a genetic risk factor for AD and has less homology to the Src family kinases (Fig. 5a–c). We designed plasmids for each of these SH3 domains fused to GST and Flag tags (Fig. 5d) and used PLA with antibodies for Tau and Flag to measure each Tau-SH3 interaction (Supplementary Figure 2). SRI-42667 again inhibited Tau-FynSH3 (Fig. 5e). It also strongly inhibited Tau-LckSH3 (Fig. 5f) and moderately inhibited Tau-BIN1 (Fig. 5g) but did not significantly inhibit Tau-SrcSH3 (Fig. 5h). Interestingly, a recent modeling study predicted that Fyn, Lck, and BIN1 bind most strongly at Tau's 5th PxxP motif, while Src binds strongly at the 7th PxxP [34]. Thus, SRI-42667 may primarily inhibit interactions that occur at the 5th/6th motif.

Given the finding that SRI-42667 inhibits multiple Tau-SH3 interactions, we asked whether it inhibits other Tau interactions. Tau's interaction with tubulin via the more carboxy-terminal microtubule-binding domain mediates its canonical function as a microtubule-stabilizing protein. We measured endogenous Tau-tubulin interactions in cultured cells using PLA. SR42667 did not inhibit Tau-tubulin binding (Fig. 5i). Thus, SRI-42667 does not broadly inhibit all Tau protein-protein interactions, but rather selectively inhibits its interactions with certain SH3 domain–containing proteins.

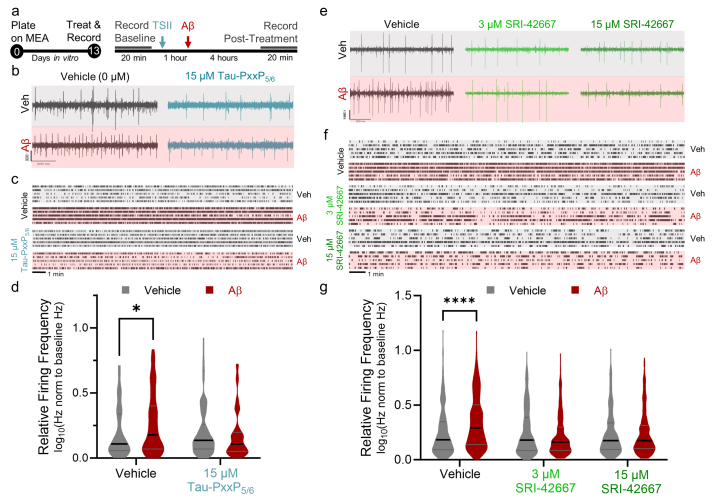

Tau-SH3 inhibition prevents Aβ-induced hyperexcitability

Network hyperexcitability is a common feature in AD that can be prevented by Tau reduction, but the effects of Tau-SH3 inhibitors on Aβ-induced hyperexcitability have not been examined. We utilized a 48-well multi-electrode array to measure changes in neuronal activity after application of 500 nM Aβ oligomers (Fig. 6a). In vehicle-treated neurons, Aβ induced an increase in neuronal activity (Fig. 6b). We first examined the effects of the Tau-SH3 inhibitor peptide based on the 5th/6th PXXP motif that we previously described [21]. Preincubation with Tau-PxxP5/6 for 1 h prevented Aβ-induced hyperactivity (Fig. 6b–d). We then tested whether SRI-42667 had a similar effect. SRI-42667 also prevented Aβ-induced network hyperexcitability at both 3 and 15 μM (Fig. 6e–g). The results demonstrate that Tau-SH3 inhibition prevents multiple hallmarks of AD pathogenesis induced by Aβ in neurons, namely metabolic dysfunction (MTT), neurite degeneration, and network hyperexcitability.

Fig. 6.

SRI-42667 ameliorates Aβ-induced neurite degeneration and network hyperexcitability.a: Timeline of MEA experiments completed on DIV13. TSII, Tau-SH3 interaction inhibitor, either Tau-PxxP5/6 (b–d) or SRI-42667 (e–g). b: Representative 1-s traces from post-treatment recordings in each of the four conditions (Veh/Veh, Veh/Aβ, Tau-PxxP5/6/Veh, Tau-PxxP5/6/Aβ). c: Representative raster plots from five neurons per group firing over the 20-min post-treatment recording. d: Quantification of neuronal firing, expressed as log-transformed ratio of post-treatment firing frequency relative to baseline. Tau-PxxP5/6 ameliorated Aβ-induced network hyperexcitability (n = 63–115 neurons per group; 2-way ANOVA interaction p = 0.02, ∗p < 0.05 by Sidak posthoc, no other significant differences on posthoc testing). Gray bars are vehicle control and red bars are Aβ-treated neurons. e: Representative 1-s traces from post-treatment recordings in each of the six conditions. f: Representative raster plots from five neurons per group firing over the 20-min post-treatment recording. g: Quantification of neuronal firing, expressed as log-transformed ratio of post-treatment firing frequency relative to baseline. SRI-42667 ameliorates Aβ-induced network hyperexcitability (n = 257–326 neurons per group from N = 2 dissections; 2-way ANOVA interaction p < 0.0001, F(2,1709) = 13.47, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by Sidak posthoc, no other significant differences on posthoc testing). Gray bars are vehicle control and red bars are Aβ-treated neurons.

Discussion

This study addresses the potential of inhibiting Tau-SH3 interactions with small-molecule compounds as a therapeutic approach for Aβ-induced dysfunction. We identified several novel compounds that inhibit Tau-SH3 interactions, and those with inhibitory activity in cell-based assays also ameliorated Aβ toxicity in neurons. The optimized compound, SRI-42667, bound to Tau and inhibited endogenous Tau-SH3 interaction in neurons without inhibiting Tau-tubulin interactions. Both SRI-42667 and a peptide inhibitor of Tau-SH3 interactions prevented Aβ-induced increases in neuronal firing, providing evidence for a role of Tau-SH3 interactions in AD-related network hyperexcitability.

Small molecules make attractive therapeutics as they are generally less expensive and more easily administered than biologics. Traditionally, protein-protein interactions have been considered challenging targets for small molecule drug discovery, particularly when the interaction involves large surface areas. However, many protein-protein interactions depend on a small “hot spot” on the larger binding surface [35], and a variety have been successfully targeted by small molecule compounds with several even progressing to clinical trials [36]. Another interaction between proline-rich and SH3 domain-containing proteins, Sam68(PxxP)-FynSH3, is inhibited by UCS15A, a unique SFK-targeting small molecule that does not inhibit SFK kinase activity or stability [37] and is structurally distinct from SRI-42667 [38]. UCS15A inhibits Sam68(PxxP)-FynSH3 interaction by binding the proline-rich domain of Sam68 rather than FynSH3 [37]. Together with our finding that SRI-42667 binds Tau, this demonstrates that proline-rich domains can serve as targets for small-molecule inhibitors of SH3 interactions, even without particularly high-affinity binding. While the relatively low blood-brain permeability of SRI-42667 may limit the utility of this specific series, our results clearly support the idea that small molecules can inhibit Tau-SH3 interactions and have biologically meaningful impacts.

Interestingly, SRI-42667 does not impact all Tau interactions and seems to be selective for certain Tau-SH3 interactions. SRI-42667 did not affect Tau-tubulin interaction, which is mediated by the more carboxy-terminal microtubule-binding domain. SRI-42667 inhibited Tau interactions with FynSH3, LckSH3, and BIN1SH3, without inhibiting interactions with SrcSH3. Notably, both FynSH3 and BIN1SH3 primarily bind Tau's 5th/6th PxxP motif in cells [25,39,40], and FynSH3, BIN1SH3, and LckSH3 all are predicted to have strongest binding at the 5th PxxP in silico [34]. In contrast, SrcSH3 binds most strongly at the 7th PxxP [34]. Thus, SRI-42667 may selectively inhibit interactions with the 5th/6th PxxP. SRI-42667 did not bind a peptide containing this sequence (Fig. 4e), so it may act allosterically or require other elements of Tau sequence to bind at that site (perhaps through interaction events such as the “paperclip” conformation of Tau, which is compacted by proline-targeting kinases [41]).

There are potential liabilities to targeting Tau-SH3 interactions. For example, Tau-Fyn interaction in oligodendrocytes promotes their maturation [42], so it will be important to determine if SRI-42667 causes oligodendrocyte dysfunction. Alternatively, other SH3-PxxP interactions could be impacted by SRI-42667. For example, Lck's interaction with the proline-rich domain of T cell–specific adapter (TSAd) promotes immune activation [43], so it will be important to determine if SRI-42667 disrupts TSAd-Lck interactions or immune function. Though this series of compounds still need to be tested in vivo, the fact that SRI-42667 binds Tau diminishes these concerns because Tau reduction has not been demonstrated to cause oligodendrocyte or immune dysfunction. Even the minor abnormalities caused by full Tau ablation are not present in Tau heterozygous mice [11,15,44,45], so partially inhibiting Tau's interaction with a subset of proteins is not likely to raise major safety concerns. Tau reduction with antisense oligonucleotides is safe in preclinical models [9,10,21], and a Tau antisense oligonucleotide, BIIB080, has been in clinical trials since 2017 and the Phase IIb results demonstrate that it lowers total Tau and phosphorylated Tau in cerebrospinal fluid in a dose-dependent manner with no severe adverse effects reported [46].

The best-studied Tau-SH3 interaction is Tau-Fyn, which occurs postsynaptically in larger complexes that include PrP/mGluR5 and PSD-95/NMDAR. Aβ oligomers activate Fyn through coreceptors PrP/mGluR5 [47,48], and targeting PrP to prevent this ameliorates Aβ toxicity [[49], [50], [51], [52]]. Fyn phosphorylates NMDARs [53], and this Tau/Fyn/NMDAR/PSD-95 complex [54] could be disrupted by Tau-SH3 inhibitors as both Fyn and PSD-95 have SH3 domains. Disrupting this complex with either a peptide interaction inhibitor [[55], [56], [57]] or genetic approaches [10,56,[58], [59], [60], [61], [62]] also prevents Aβ toxicity and network hyperexcitability. In particular, the MAP kinase p38γ disrupts this complex by phosphorylating Tau at T205 and prevents AD-associated dysfunction in vivo [63,64]. Beyond AD models, p38γ gene therapy prevents dysfunction in a mouse model of epilepsy [65]. Altogether, the postsynaptic role of Tau as a scaffold complexing with SH3 domain-containing proteins is clear, and this work demonstrates that Tau-SH3 interactions can be inhibited to prevent neuronal dysfunction and network hyperexcitability.

Targeting Tau-SH3 interactions may have fewer downsides than directly targeting SH3 proteins like Fyn. Fyn kinase inhibition with saracatinib prevented dysfunction in preclinical AD models [33]. However, there is likely a relatively narrow therapeutic window for Fyn inhibition, and a Phase IIa clinical trial with saracatinib showed no clinical benefit in AD at a tolerable dose [66]. Interestingly, saracatinib was recently reported to reduce Tau-Fyn interaction in cells [67], so it is possible that its beneficial effects in preclinical models result (at least in part) from inhibiting Tau-Fyn interaction in addition to or rather than by inhibiting Fyn kinase. However, this inhibition was observed at high concentrations that are unlikely to be achieved in clinical trials, so it is unlikely that saracatinib significantly inhibited Tau-Fyn interaction in human brains.

An important finding in our study is that Tau-SH3 inhibition prevents Aβ-induced network hyperexcitability. This is the first evidence directly relating Tau-SH3 interactions to network hyperexcitability and adds to the evidence that Tau is critical for pathogenic network hyperexcitability in neurodegeneration. Network hyperexcitability occurs early in AD pathogenesis, can be driven by Aβ, and contributes to neuronal excitotoxicity [68]. Tau reduction prevents network hyperexcitability [3,4,9,[11], [12], [13]], and the effects of SRI-42667 support the idea that prevention of Tau-SH3 interactions may underlie the beneficial effects of Tau reduction in the context of neurodegeneration and network hyperexcitability.

This study provides preclinical evidence supporting the idea of inhibiting Tau-SH3 interactions as a potential novel therapeutic strategy for AD. It provides a broad outline of a pipeline for identifying and optimizing small molecule protein-protein interaction inhibitors for use in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer's disease that ultimately could be used in the clinic. Finally, this study provides mechanistic insights into Aβ-induced dysfunction, indicating that Tau's interactions with SH3 domain–containing proteins are critical for Aβ toxicity and network hyperexcitability, which could underlie the beneficial effects of Tau reduction.

Author contributions

JRR, TR, JNC, JJD, JRB, MJS, CEAS, and EDR developed assays and designed experiments. JRR, TR, SJT, ARA, TBD, JSM, JNC, NRB, HBD, ZY, VP, PR, and MW performed experiments. JRR and EDR led data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from the other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data in this study is presented in the manuscript, supplementary materials, and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of competing interest

EDR is an owner of intellectual property relating to Tau.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Herskowitz and Arrant labs at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and the Drug Discovery Division at Southern Research for valuable input to study design and discussion. Access to the Auto-iTC200 instrument was provided by the Biocalorimetry Lab supported by the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant and Shared Facility Program of the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS075487, RF1AG059405, UL1TR001417, P20AG068024, T32NS061455, T32NS095775, and F31AG064868, BrightFocus Foundation grant A2015693S, the Alabama Drug Discovery Alliance, the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, and a Weston Brain Institute advisor fellowship. ITC work completed in the Biocalorimetry lab was supported by NIH grant S10RR026478 and the Structural Biology Shared Facility of the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center, supported by P30CA013148. This work was also supported in part using hardware maintained with funding from the National Science Foundation under grant number OAC-1541310, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and the Alabama Innovation Fund.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurot.2023.10.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

2

3

References

- 1.Rapoport M., Dawson H.N., Binder L.I., Vitek M.P., Ferreira A. Tau is essential to β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(9):6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092136199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberson E.D., Scearce-Levie K., Palop J.J., Yan F., Cheng I.H., Wu T., et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316(5825):750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ittner L.M., Ke Y.D., Delerue F., Bi M., Gladbach A., van Eersel J., et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142(3):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberson E.D., Halabisky B., Yoo J.W., Yao J., Chin J., Yan F., et al. Amyloid-beta/Fyn-induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):700–711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4152-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leroy K., Ando K., Laporte V., Dedecker R., Suain V., Authelet M., et al. Lack of tau proteins rescues neuronal cell death and decreases amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1 mice. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(6):1928–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meilandt W.J., Yu G.-Q., Chin J., Roberson E.D., Palop J.J., Wu T., et al. Enkephalin elevations contribute to neuronal and behavioral impairments in a transgenic mouse model of alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28(19):5007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0590-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nussbaum J.M., Schilling S., Cynis H., Silva A., Swanson E., Wangsanut T., et al. Prion-like behaviour and tau-dependent cytotoxicity of pyroglutamylated amyloid-β. Nature. 2012;485(7400):651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature11060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palop J.J., Chin J., Roberson E.D., Wang J., Thwin M.T., Bien-Ly N., et al. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2007;55(5):697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVos S.L., Goncharoff D.K., Chen G., Kebodeaux C.S., Yamada K., Stewart F.R., et al. Antisense reduction of tau in adult mice protects against seizures. J Neurosci: J Society Neurosci. 2013;33(31):12887–12897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2107-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVos S.L., Miller R.L., Schoch K.M., Holmes B.B., Kebodeaux C.S., Wegener A.J., et al. Tau reduction prevents neuronal loss and reverses pathological tau deposition and seeding in mice with tauopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(374) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z., Hall A.M., Kelinske M., Roberson E.D. Seizure resistance without parkinsonism in aged mice after tau reduction. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(11):2617–2624. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gheyara A.L., Ponnusamy R., Djukic B., Craft R.J., Ho K., Guo W., et al. Tau reduction prevents disease in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(3):443–456. doi: 10.1002/ana.24230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holth J.K., Bomben V.C., Reed J.G., Inoue T., Younkin L., Younkin S.G., et al. Tau loss attenuates neuronal network hyperexcitability in mouse and Drosophila genetic models of epilepsy. J Neurosci: J Society Neurosci. 2013;33(4):1651–1659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3191-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh B., Covelo A., Martell-Martinez H., Nanclares C., Sherman M.A., Okematti E., et al. Tau is required for progressive synaptic and memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of alpha-synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02032-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tai C., Chang C.W., Yu G.Q., Lopez I., Yu X., Wang X., et al. Tau reduction prevents key features of autism in mouse models. Neuron. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee G., Newman S.T., Gard D.L., Band H., Panchamoorthy G. Tau interacts with src-family non-receptor tyrosine kinases. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:3167–3177. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.21.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds C.H., Garwood C.J., Wray S., Price C., Kellie S., Perera T., et al. Phosphorylation regulates tau interactions with Src homology 3 domains of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cgamma1, Grb2, and Src family kinases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):18177–18186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-Mármol R., Small C., Jiang A., Palliyaguru T., Wallis T.P., Gormal R.S., et al. Fyn nanoclustering requires switching to an open conformation and is enhanced by FTLD-Tau biomolecular condensates. Mol Psychiatr. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01825-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirazi S.K., Wood J.G. The protein tyrosine kinase, fyn, in Alzheimer's disease pathology. Neuroreport. 1993;4:435–437. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199304000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho G.J., Hashimoto M., Adame A., Izu M., Alford M.F., Thal L.J., et al. Altered p59Fyn kinase expression accompanies disease progression in Alzheimer's disease: implications for its functional role. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(5):625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rush T., Roth J.R., Thompson S.J., Aldaher A.R., Cochran J.N., Roberson E.D. A peptide inhibitor of Tau-SH3 interactions ameliorates amyloid-beta toxicity. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert M.P., Barlow A.K., Chromy B.A., Edwards C., Freed R., Liosatos M., et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chin J., Palop J.J., Yu G.Q., Kojima N., Masliah E., Mucke L. Fyn kinase modulates synaptotoxicity, but not aberrant sprouting, in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci: J Society Neurosci. 2004;24(19):4692–4697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0277-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voskobiynyk Y., Roth J.R., Cochran J.N., Rush T., Carullo N.V., Mesina J.S., et al. Alzheimer's disease risk gene BIN1 induces Tau-dependent network hyperexcitability. eLife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.57354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cochran J.N., Diggs P.V., Nebane N.M., Rasmussen L., White E.L., Bostwick R., et al. AlphaScreen HTS and live-cell bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays for identification of Tau-Fyn SH3 interaction inhibitors for Alzheimer disease. J Biomol Screen. 2014;19(10):1338–1349. doi: 10.1177/1087057114547232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Studier F.W. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41(1):207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arold S.T., Ulmer T.S., Mulhern T.D., Werner J.M., Ladbury J.E., Campbell I.D., et al. The role of the Src homology 3-Src homology 2 interface in the regulation of Src kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(20):17199–17205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Case DA, Berryman JT, Betz RM, Cerutti DS, Cheatham III TE, Darden TA, et al. AMBER 2015. University of California, San Francisco2015.

- 29.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K.E., Simmerling C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theor Comput. 2015;11(8):3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(9):1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roe D.R., Cheatham T.E., 3rd PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theor Comput. 2013;9(7):3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrodinger L.L.C. 2015. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nygaard H.B. Targeting fyn kinase in alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatr. 2018;83(4):369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Chang C., Wang D., Hong S. Systematic profiling of SH3-mediated Tau–Partner interaction network in Alzheimer's disease by integrating in silico analysis and in vitro assay. J Mol Graph Model. 2019;90:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arkin M.R., Tang Y., Wells J.A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality. Chem Biol. 2014;21(9):1102–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong G., Sheng C. In: Targeting Protein-Protein Interactions by Small Molecules. Sheng C., Georg G.I., editors. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2018. Overview of protein-protein interactions and small-molecule inhibitors under clinical development; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oneyama C., Nakano H., Sharma S.V. UCS15A, a novel small molecule, SH3 domain-mediated protein-protein interaction blocking drug. Oncogene. 2002;21(13):2037–2050. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma S.V., Oneyama C., Yamashita Y., Nakano H., Sugawara K., Hamada M., et al. UCS15A, a non-kinase inhibitor of Src signal transduction. Oncogene. 2001;20(17):2068–2079. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lasorsa A., Malki I., Cantrelle F.X., Merzougui H., Boll E., Lambert J.C., et al. Structural basis of tau interaction with BIN1 and regulation by tau phosphorylation. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:421. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Usardi A., Pooler A.M., Seereeram A., Reynolds C.H., Derkinderen P., Anderton B., et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of tau regulates its interactions with Fyn SH2 domains, but not SH3 domains, altering the cellular localization of tau. FEBS J. 2011;278(16):2927–2937. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeganathan S., Hascher A., Chinnathambi S., Biernat J., Mandelkow E.M., Mandelkow E. Proline-directed pseudo-phosphorylation at AT8 and PHF1 epitopes induces a compaction of the paperclip folding of Tau and generates a pathological (MC-1) conformation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(46):32066–32076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein C., Kramer E.M., Cardine A.M., Schraven B., Brandt R., Trotter J. Process outgrowth of oligodendrocytes is promoted by interaction of fyn kinase with the cytoskeletal protein tau. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):698–707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00698.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen T.C.B., Kristiansen P.E., Huszenicza Z., Johansson M.U., Gopalakrishnan R.P., Kjelstrup H., et al. The SH3 domains of the protein kinases ITK and LCK compete for adjacent sites on T cell-specific adapter protein. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(42):15480–15494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ikegami S., Harada A., Hirokawa N. Muscle weakness, hyperactivity, and impairment in fear conditioning in tau-deficient mice. Neurosci Lett. 2000;279(3):129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00964-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei P., Ayton S., Moon S., Zhang Q., Volitakis I., Finkelstein D.I., et al. Motor and cognitive deficits in aged tau knockout mice in two background strains. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mummery C.J., Börjesson-Hanson A., Blackburn D.J., Vijverberg E.G.B., De Deyn P.P., Ducharme S., et al. Tau-targeting antisense oligonucleotide MAPTRx in mild Alzheimer's disease: a phase 1b, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nat Med. 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Um J.W., Nygaard H.B., Heiss J.K., Kostylev M.A., Stagi M., Vortmeyer A., et al. Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(9):1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Um J.W., Kaufman A.C., Kostylev M., Heiss J.K., Stagi M., Takahashi H., et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a coreceptor for Alzheimer aβ oligomer bound to cellular prion protein. Neuron. 2013;79(5):887–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gunther E.C., Smith L.M., Kostylev M.A., Cox T.O., Kaufman A.C., Lee S., et al. Rescue of transgenic alzheimer's pathophysiology by polymeric cellular prion protein antagonists. Cell Rep. 2019;26(1):145–158.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cox T.O., Gunther E.C., Brody A.H., Chiasseu M.T., Stoner A., Smith L.M., et al. Anti-PrP(C) antibody rescues cognition and synapses in transgenic alzheimer mice. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(3):554–574. doi: 10.1002/acn3.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spurrier J., Nicholson L., Fang X.T., Stoner A.J., Toyonaga T., Holden D., et al. Reversal of synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models by targeting mGluR5 to prevent synaptic tagging by C1Q. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(647) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi8593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ali T., Klein A.N., Vu A., Arifin M.I., Hannaoui S., Gilch S. Peptide aptamer targeting Aβ–PrP–Fyn axis reduces Alzheimer's disease pathologies in 5XFAD transgenic mouse model. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2023;80(6):139. doi: 10.1007/s00018-023-04785-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tezuka T., Umemori H., Akiyama T., Nakanishi S., Yamamoto T. PSD-95 promotes Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(2):435–440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mondragón-Rodríguez S., Trillaud-Doppia E., Dudilot A., Bourgeois C., Lauzon M., Leclerc N., et al. Interaction of endogenous tau protein with synaptic proteins is regulated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent tau phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(38):32040–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aarts M., Liu Y., Liu L., Besshoh S., Arundine M., Gurd J.W., et al. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor- PSD-95 protein interactions. Science. 2002;298(5594):846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ittner L.M., Ke Y.D., Delerue F., Bi M., Gladbach A., van Eersel J., et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142(3):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rush T., Roth J.R., Thompson S.J., Aldaher A.R., Cochran J.N., Roberson E.D. A peptide inhibitor of Tau-SH3 interactions ameliorates amyloid-β toxicity. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;134 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberson E.D., Halabisky B., Yoo J.W., Yao J., Chin J., Yan F., et al. Amyloid-β/Fyn-induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):700–711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4152-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeVos S.L., Goncharoff D.K., Chen G., Kebodeaux C.S., Yamada K., Stewart F.R., et al. Antisense reduction of tau in adult mice protects against seizures. J Neurosci. 2013;33(31):12887–12897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2107-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chin J., Palop J.J., Yu G.-Q., Kojima N., Masliah E., Mucke L. Fyn kinase modulates synaptotoxicity, but not aberrant sprouting, in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24(19):4692–4697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0277-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberson E.D., Scearce-Levie K., Palop J.J., Yan F., Cheng I.H., Wu T., et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316(5825):750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Putra M., Puttachary S., Liu G., Lee G., Thippeswamy T. Fyn-tau ablation modifies PTZ-induced seizures and post-seizure hallmarks of early epileptogenesis. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.592374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ittner A., Chua S.W., Bertz J., Volkerling A., van der Hoven J., Gladbach A., et al. Site-specific phosphorylation of tau inhibits amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer's mice. Science. 2016;354(6314):904–908. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ittner A., Asih P.R., Tan A.R.P., Prikas E., Bertz J., Stefanoska K., et al. Reduction of advanced tau-mediated memory deficits by the MAP kinase p38γ. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140(3):279–294. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morey N., Przybyla M., van der Hoven J., Ke Y.D., Delerue F., van Eersel J., et al. Treatment of epilepsy using a targeted p38γ kinase gene therapy. Sci Adv. 2022;8(48) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.add2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Dyck C.H., Nygaard H.B., Chen K., Donohue M.C., Raman R., Rissman R.A., et al. Effect of AZD0530 on cerebral metabolic decline in alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(10):1219–1229. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang S.J., Fesharaki-Zadeh A., Takahashi H., Nies S.H., Smith L.M., Luo A., et al. Fyn kinase inhibition reduces protein aggregation, increases synapse density and improves memory in transgenic and traumatic Tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-00976-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Palop J.J., Mucke L. Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(12):777–792. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

2

3

Data Availability Statement

All data in this study is presented in the manuscript, supplementary materials, and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.