Abstract

Purpose

Research-based theater uses drama to communicate research findings to audiences beyond those that typically read peer-reviewed journals. We applied research-based theater to translate qualitative research findings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on different segments of U.S. society.

Approach

Theater artists and public health researchers collaborated to create a collection of eight monologues from systematically sourced, peer-reviewed publications. Following three virtual performances in Spring, 2021, audience members were invited to complete a survey.

Setting/Participants

Audience survey respondents (n = 120) were mostly U.S.-based and were diverse in terms of age, race/ethnicity, gender, profession, and experience attending theater.

Method

We summarized closed-ended responses and explored patterns by demographic characteristics. We synthesized themes of open-ended responses with inductive coding.

Results

Audience members somewhat/strongly agreed that COVID Monologues increased their knowledge (79.4%), represented the reality of the U.S. COVID-19 epidemic (95.7%), and offered new perspectives on what people had been experiencing (87.5%). Most also agreed research-based theater is an effective means of understanding health research (93.5%) and can promote community resilience in times of public health crisis (83.2%). Mann-Whitney U tests suggested less positive reactions from demographics that were not well-represented in monologue characters (cisgender men, Hispanics). Qualitative comments suggested audience members valued monologues that offered self-reflection and validation of their own COVID-19 experiences through relatable characters as well as those that offered insight into the experiences of people different from themselves.

Conclusion

This work adds to evidence that research-based theater can help build knowledge and emotional insight around a public health issue. As these elements are foundational to pro-social, preventative health behaviors, research-based theater may have a useful role in promoting collective response to public health crises like COVID-19. Our method of systematically-sourcing research for theater-based dissemination could be extended to target more specific audiences with actionable behaviors.

Keywords: research-based theater, COVID-19, dissemination, knowledge translation, qualitative research

Background

The early months of the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic ignited a dramatic shift in how people engaged with their social world. Social distancing guidelines sharply limited opportunities for in-person interaction, impeding empathetic attitudes and behaviors according to some studies.1,2 At the same time, most people sought information about the pandemic from media designed for quick consumption, 3 which offered limited opportunity to develop insight into the experience of others and often fueled the spread of misinformation. Arguably, the loss of familiar opportunities to develop social consciousness and express empathy may have contributed to divisiveness over the pro-social behaviors that the pandemic response depended on (i.e., masking, vaccinations, support for policies to address disparities).

Theater and qualitative research are two powerful tools for opening empathetic windows into the experiences of others. 4 In times of social crisis throughout history, theater has been used to evoke understanding and empathy, generate social commentary, and inspire collective action. 5 Qualitative research has also served these purposes, and in epidemics specifically, has contributed to better understanding of social issues behind disease trends, as well as the needs of populations most affected.6,7

Theater and qualitative research are natural partner disciplines, as both commit to interpreting human experience and co-constructing meaning.8,9 Research-based theater is an umbrella term for the various ways of integrating theater and research to produce, interpret, and/or disseminate findings.8,10 In using research-based theater for dissemination, researchers and artists are challenged with creating theater that is both credible as research and aesthetically valuable as art. 10 Various forms of research-based theater have taken different approaches to striking this balance. For example, research-based theater can incorporate varying degrees of verbatim dialogue and performance meant to directly reproduce the words or behaviors of research participants, 11 as well as more fictional or interpretive elements.

A common goal of research-based theater is to engage audiences in both an intellectual and emotional understanding of data.10,12 As a tool for knowledge translation, research-based theater can be useful in reaching audiences beyond those that typically read peer-reviewed articles. 13 Past research-based theater has had measurable impact on audience knowledge and empathetic perspectives about public health topics including traumatic brain injury, breast cancer, and dementia.14,15 In times of social crisis, it has facilitated audience reflection on complex and diverse perspectives, such as in Anna Deavere Smith’s plays exploring racial conflict and inequities in healthcare and criminal justice.16-18

We sought to create research-based theater about the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. society. We aimed to create theater that offered audience members an empathetic perspective on the experiences of multiple affected groups. We also aimed to produce the work rapidly, so that the content remained timely and relatable during the constantly evolving pandemic. Further, we wanted to capitalize on existing knowledge that qualitative researchers had co-constructed on COVID-19 and society. Thus, instead of collecting primary data, we conducted a systematic review to identify published studies. In public health, systematic reviews identify, appraise, and synthesize scientific literature on a particular topic using predefined search and screening criteria. 19 We used such a review to identify qualitative peer-reviewed research that could be transformed into theater to translate knowledge about the societal impact of COVID-19 in the United States.

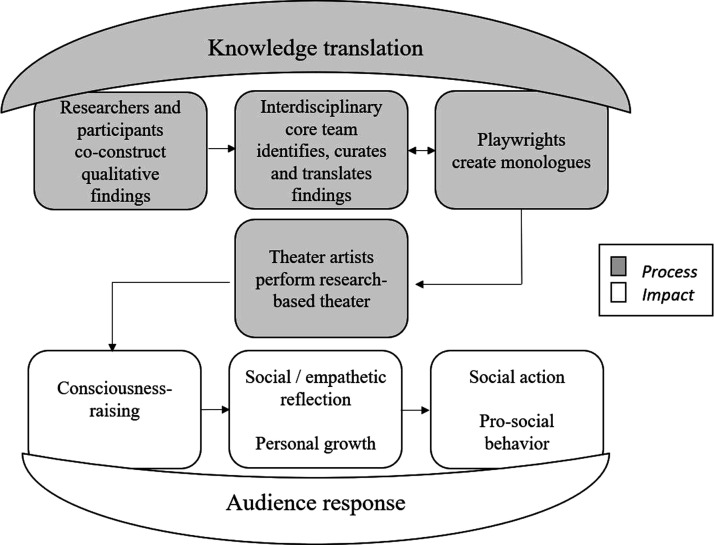

This paper describes our process and assesses audience response to the resulting performances. Our conceptual model (Figure 1) illustrates our goals in bringing together the meaning-making processes of qualitative research and playwrighting to produce research-based theater. Our goals in audience impact reflect leading theories on the potential functions of research-based theater. 20 Through the performances, we aimed to raise consciousness on the societal impact of COVID-19, with particular interest in assessing resulting social reflection and personal growth. These elements, in turn, can serve as foundation for social action and pro-social behavior. 4

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of intended process and impact of research-based theater dissemination of qualitative findings.

Methods

Project Overview

COVID Monologues consisted of eight 10-minute filmed monologue performances created from systematically sourced peer reviewed research. The project was led by an interdisciplinary core team consisting of two public health researchers with theater backgrounds (EAH, ST) and two theater artists (GDM, JR). This team worked with a group of selected playwrights (see below) as well as actors, directors, and support staff from five partner theater companies in Baltimore, MD. Partner theater companies were selected to cover diverse areas of focus (e.g., new works, works by Black women) and had previous successful partnerships with members of the core team.

Rather than a full-length play, we chose to create monologues, as they could be disseminated individually (highlighting findings related to distinct, diverse sub-topics) or as a collection (presenting audiences with cross-cutting themes related to COVID-19’s societal impact). Shorter, stand-alone pieces also offered more opportunities for collaboration between multiple playwrights and theater companies. Further, the monologue as an art form is closely aligned with live theater, allowing artists to work within their existing skill set.

Sourcing Research

The two public health researchers in the core team conducted a systematic search to identify qualitative research about the U.S. COVID-19 epidemic. Working with a medical library informationist, the researchers created a search string to retrieve articles that met these eligibility criteria in abstracts, titles, or medical subject heading (MeSH) terms. An initial search in PubMed on August 17th, 2020 identified 62 articles. These were reviewed and excluded if they (1) did not use qualitative methods, (2) were based on data collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and/or (3) were not U.S.-focused. On November 2nd, 2020, we performed the search and review again to add any new publications. We categorized the resulting 31 articles into topic areas and ranked each on the richness of qualitative quotes and overall theatrical potential. We then ranked topics by assessing overall availability of rigorous, rich qualitative research and relevance to public health priorities informed by conversations with leaders of COVID-19 response in the Baltimore, MD public health department.

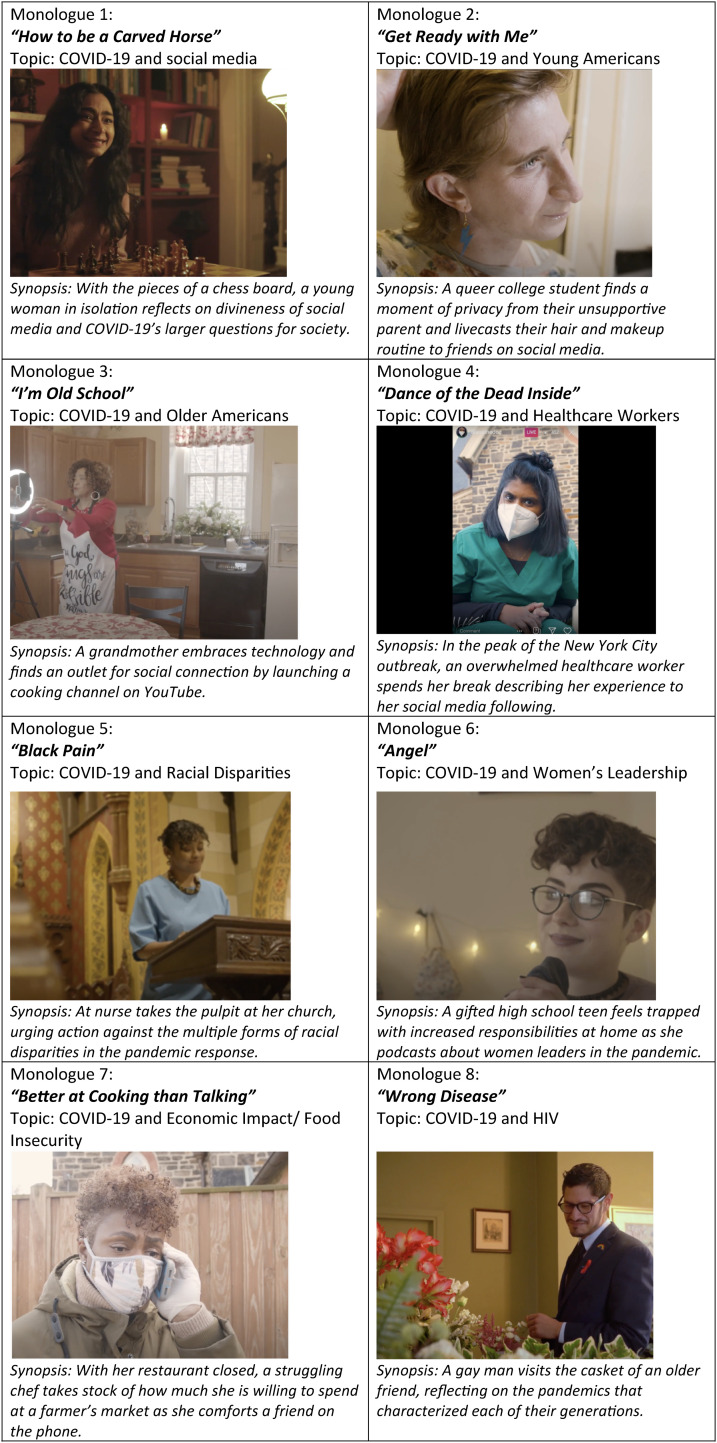

We selected eight final topics after determining that eight monologues of ∼10 minutes each could be feasibly presented as a collection in a virtual performance. The final topics were COVID-19 and: social media, young adults, older adults, healthcare workers, racial disparities, women’s leadership, economic impact/food insecurity, and HIV. With the 19 related articles, we created research packets for each topic with the 1-3 key main qualitative articles and short summaries of their key messages. We also reached out to all corresponding authors and indicated to playwrights the researchers who agreed to be available for feedback on the monologue's development and those that gave permission to use direct quotations from their papers. To enhance understanding of each topic, research packets also included references and summaries of supplemental quantitative articles and scientific commentary published in top medical and public health journals (JAMA collection, New England Journal of Medicine, and American Journal of Public Health).

Selecting Playwrights

In summer 2020, the core team launched an open call for playwright applications, based on an application and evaluation model by an established playwrighting fellowship program. The call for applications was disseminated through mid-Atlantic and national playwrighting Facebook groups, project partner theaters, theatre industry professional groups (e.g. Theatre Communications Group), as well as colleges and universities in the mid-Atlantic region. The core team and an additional ten volunteers from the Baltimore theater community reviewed a total of 61 applications. Four reviewers scored each application for commitment to the project objective, experience and qualifications of the playwright, and quality of a playwriting sample. Final selection was based on score and ability to match playwrights with research topics specific to their interests and/or lived experience. The eight chosen playwrights represented diversity in racial, ethnic, and gender identity: White female (n = 2), White male, Black/Afro-Latina female, Black/Latino male, Asian-American female, White transgender male, White non-binary. They also ranged in age (mid-20s to mid-40s) and professional background (from playwrights with more than a decade of professional experience to early career and hobbyist playwrights). Upon completion of the monologue script, playwrights were compensated $500.

Creating and Performing “COVID Monologues”

In translating findings, creators of research-based theater must situate each project along a continuum of factual/verbatim presentation and artistic interpretation. 13 For this project, playwrights first attended a masterclass with experts in research-based theater and related playwrighting technique. We then gave them artistic license with instructions to communicate one or more key messages from the main articles in their research packets. Some chose to incorporate direct quotes from publications; others did not. The playwrights workshopped early drafts with one another, their assigned partner theaters, and the project leaders. Actors and directors staged the monologues, which were filmed and edited by professional videographers.

We aired three free virtual performances of the COVID Monologues in late February and early March, 2021. Each event included a streaming of all eight recorded monologues and a post-performance open question-and-answer session with the core team, as well as actor, playwright, and director representatives. While each performance was open to all, we focused advertising for one as a general performance, one as a public health professional performance, and one as a high school/college performance to accommodate a suitable time of day for each audience and recognize that students and professionals may appreciate joining the post-performance discussion with peers. Performances were promoted through partner theater companies, social media advertisements, and university/professional listservs. Local high school and college classes were invited to the student performance through instructors who previously worked with the core team and/or partner theaters. Performances were streamed on Zoom and partner theater companies’ social media accounts (Facebook, YouTube). All recorded monologues were made publicly available online following the first streamed performance.

Audience Survey

Audiences were invited to complete a 5-minute online REDCap survey on their reactions to COVID Monologues. Announcements about the survey were made throughout each live performance and posted on the website. Audience members 13 years or older who had viewed one or more of the monologues and had not previously completed the survey were eligible to participate. Participants were offered a $5 electronic gift card upon completion of the survey or the opportunity to decline. All survey methods were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children's Mercy Kansas City. Upon entering the online survey, participants were required to electronically indicate their consent before proceeding to the survey questions.

Survey questions covered demographics (age, race, ethnicity, gender, geographic location, professional role, experience attending theater), and the survey participant’s level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale that COVID Monologues (1) “represented the reality of COVID-19 in the U.S.”; (2) “increased my knowledge about one or more aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.”; and (3) “gave me a new perspective on what people have been experiencing in the pandemic.” Participants were also asked the extent to which they agreed that research-based theater, like COVID Monologues, “is an effective way for people to understand public health research” and “can help communities become more resilient in times of public health crises”. Participants were also asked which monologue made the strongest impression on them and why, and to provide general comments on the performance.

Participants who self-identified as making decisions, rules, guidelines, or actions about the pandemic that affect the lives of others were invited to complete a 1-month follow-up survey in order to identify if and how the performance affected their decisions related to pandemic response. These decision-makers were asked to describe their role, how they typically access and use research, and the extent they agreed with three statements: (1) “I found myself thinking about the COVID Monologues performance in my professional life”; (2) “The COVID Monologues performance influenced a decision I made in the last month” and (3) “The COVID Monologues performance affected the way I think about my work moving into the future”.

Data Analysis

Quantitative survey data were transferred from REDCap to STATA version 15 for analysis. Demographics and Likert-scale responses were summarized with descriptive statistics. A series of Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to compare distribution of Likert scale responses among participants who did and did not belong to each demographic category of role, age category, race, ethnicity and gender.

Qualitative responses were transferred from REDCap to Dedoose. The first author applied an inductive coding strategy to label free responses, then synthesized codes into broader themes. Memoing and team debriefing guided the selection of major themes and representative quotes presented in the results.

Results

Monologues and Performances

Eight filmed monologues were shown at three performances and posted on www.covidmonologues.com. Figure 2 presents each monologue’s title and a photo. Research references for each monologue are included as Supplementary Material. Based on logons and estimations of joint viewing, we estimate the three performances drew a total audience of around 400 people.

Figure 2.

COVID Monologues: Titles, topics, and synopsis.

Audience Survey Participants

The 120 survey participants were mostly from the U.S. (representing 18 states and Washington D.C.) with two from the UK and two from Canada. Participants were diverse in terms of professional role, age, race, ethnicity, and gender (Table 1). One-third reported attending theater five or more times per year, another third attended two-four times per year, 25.8% attended once a year or less, and for 8%, COVID Monologues was their first-time attending theater.

Table 1.

Audience Survey Participant Demographic (n = 120).

| Gender | |

| Male | 27 (24.8%) |

| Female | 76 (69.7%) |

| Non-binary/Other | 6 (5.5%) |

| Age range | |

| 13-19 years | 24 (22.2%) |

| 20- 29 years | 32 (29.6%) |

| 30- 39 years | 18 (16.7%) |

| 40- 49 years | 9 (8.3%) |

| 50- 59 years | 12 (11.1%) |

| 60- 69 years | 11 (10.2%) |

| 70 years or older | 2 (1.9%) |

| Race a | |

| American Indian | 3 (2.8%) |

| Asian | 15 (14.0%) |

| Black/African-American | 26 (24.3%) |

| White | 63 (58.9%) |

| Other | 9 (8.4%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 19 (19.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 78 (80.4%) |

| Role/Occupation a | |

| Public health researcher | 22 (18.3%) |

| Public health professional | 17 (14.2%) |

| Theatre arts professional | 14 (11.7%) |

| High school student | 29 (24.2%) |

| College student | 10 (8.3%) |

| None of the above | 37 (30.8%) |

| How often do you attend theatre? | |

| Once a month or more | 16 (13.3%) |

| 5-11 times per year | 24 (20.0%) |

| 2-4 times per year | 39 (32.5%) |

| Once a year or less | 31 (25.8%) |

| This was my first time attending theatre | 10 (8.3%) |

aParticipants had the option to select more than one category.

Quantitative Responses

Table 2 details responses to the five Likert-scale opinion questions. Most participants felt that COVID Monologues increased their knowledge on one or more aspects of the pandemic in the U.S., represented the reality of COVID-19 in the US, and gave them a new perspective of what people have been experiencing in the pandemic. Participants also generally felt that research-based theater is an effective way for people to understand public health research and that it can contribute to community resilience in times of public health crises.

Table 2.

Responses to Likert Scale Opinion Questions and Associations With Demographic Characteristics.

| “COVID monologues… | “Research-based theater like COVID monologues… | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … increased my knowledge on one or more aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S” | …represented the reality of COVID-19 in the U.S.” | …gave me a new perspective on what people have been experiencing in the pandemic” | … is an effective way for people to understand public health research” | …can help communities become more resilient in times of public health crises” | ||||||

| [N, (%)] | Mann-Whitney Test (z, P) | [N, (%)] | Mann-Whitney Test (z, P) | [N, (%)] | Mann-Whitney Test (z, P) | [N, (%)] | Mann-Whitney Test (z, P) | [N, (%)] | Mann-Whitney Test (z, P) | |

| Strongly Agree | Strongly Agree | Strongly Agree | Strongly Agree | Strongly Agree | ||||||

| Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Agree | ||||||

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | ||||||

| Somewhat Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | ||||||

| Strongly Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Strongly Disagree | ||||||

| Total | 53 (47.3) | - | 76 (67.9) | - | 64 (57.1) | - | 77 (70.6) | - | 58 (53.2) | - |

| 36 (32.1) | 31 (27.8) | 34 (30.4) | 25 (22.9) | 39 (35.8) | ||||||

| 11 (9.8) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (4.5) | 2 (1.8) | 10 (9.2) | ||||||

| 7 (6.3) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (4.5) | 4 (3.7) | 2 (1.8) | ||||||

| 5 (4.5) | 0 (.0) | 4 (3.6) | 1 (.9) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Role/Occupation | ||||||||||

| Public health researcher or professional | 12 (38.7) | −1.129 a (.26) | 21 (67.7) | .100 (.92) | 17 (54.8) | −.220 (.83) | 25 (83.3) | 1.613 (.17) | 16 (53.3) | −.322 (.75) |

| 11 (35.5) | 8 (25.8) | 10 (32.3) | 3 (10.0) | 9 (30.0) | ||||||

| 4 (12.9) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (.0) | 4 (.0) | ||||||

| 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | ||||||

| 1 (3.2) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| High school or college student | 18 (54.6) | .523 (.60) | 19 (57.6) | −1.360 (.17) | 21 (63.6) | .803 (.42) | 21 (63.6) | −1.080 (.28) | 16 (48.5) | −.640 (.52) |

| 7 (21.2) | 13 (39.4) | 8 (24.4) | 9 (27.3) | 13 (39.4) | ||||||

| 4 (12.1) | 0 (.0) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (3.0) | 3 (9.1) | ||||||

| 3 (9.1) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (3.0) | ||||||

| 1 (3.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (3.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Theater arts professional | 3 (21.4) | −2.211 (.03) | 11 (78.6) | .781 (.43) | 7 (50.0) | −1.132 (.26) | 7 (50.0) | −1.852 (.06) | 6 (42.9) | −.809 (.42) |

| 6 (42.9) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (42.9) | ||||||

| 2 (14.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (14.3) | ||||||

| 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 2 (14.3) | 0 (.0) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| None of the above | 21 (58.3) | 2.234 (.03) | 27 (75.0) | 1.145 (.25) | 20 (55.6) | .221 (.82) | 26 (76.5) | 1.116 (.26) | 21 (61.8) | 1.548 (.12) |

| 13 (36.1) | 8 (22.2) | 14 (38.9) | 8 (23.5) | 12 (35.3) | ||||||

| 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (.0) | 1 (2.9) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0 | 1 (2.8) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 13-19 | 12 (50.0) | −.180 (.86) | 15 (62.5) | −.595 (.56) | 17 (70.8) | 1.512 (.13) | 16 (66.7) | −.495 (.62) | 12 (50.0) | −.604 (.55) |

| 5 (20.8) | 8 (33.3) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (25.0) | 8 (33.3) | ||||||

| 5 (16.7) | 0 (.0) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 3 (12.5) | ||||||

| 2 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | ||||||

| 1 (4.2) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 20-29 | 15 (46.9) | .257 (.80) | 22 (68.8) | .323 (.75) | 18 (56.3) | −.251 (.80) | 23 (71.9) | .305 (.76) | 19 (59.4) | 1.014 (.31) |

| 12 (37.5) | 10 (31.3) | 9 (28.1) | 8 (25.0) | 11 (34.4) | ||||||

| 2 (6.3) | 0 (.0) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (.0) | 2 (6.3) | ||||||

| 2 (6.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 1 (3.1) | 0 (.0) | 2 (6.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 30-49 | 8 (29.6) | −1.636 (.10) | 18 (66.7) | −.258 (.80) | 15 (55.6) | −.326 (.74) | 17 (63.0) | −.977 (.33) | 12 (44.4) | −1.120 (.26) |

| 13 (48.2) | 7 (25.9) | 8 (29.6) | 8 (29.6) | 11 (40.7) | ||||||

| 3 (11.1) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 3 (11.1) | ||||||

| 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | ||||||

| 1 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 50 and older | 11 (64.7) | 1.303 (.19) | 11 (64.7) | −.338 (.74) | 9 (52.9) | −.256 (.80) | 11 (78.6) | .591 (.55) | 10 (71.4) | 1.400 (.16) |

| 3 (17.7) | 5 (29.4) | 6 (35.3) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (21.4) | ||||||

| 2 (11.8) | 0 (.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (.0) | 1 (7.1) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 1 (5.9) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (33.3) | −1.215 (.22) | 1 (33.3) | −1.589 (.11) | 1 (33.3) | −1.027 (.30) | 2 (66.7) | −.511 (.61) | 1 (33.3) | −.930 (.35) |

| 0 (.0) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (.0) | 1 (33.3) | ||||||

| 1 (33.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (33.3) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 1 (33.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Asian | 9 (60.0) | 1.318 (.19) | 12 (80.0) | 1.146 (.25) | 12 (80.0) | 2.053 (.04) | 14 (93.3) | 2.086 (.04) | 11 (73.3) | 1.850 (.06) |

| 5 (33.3) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (6.7) | 4 (26.7) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 1 (6.7) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Black or African American | 13 (50.0) | .045 (.96) | 19 (73.1) | .650 (.52) | 16 (61.5) | .358 (.72) | 21 (80.8) | 1.436 (.15) | 14 (53.9) | .012 (.99) |

| 6 (23.1) | 6 (23.1) | 6 (23.1) | 5 (19.2) | 9 (34.6) | ||||||

| 5 (19.2) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (.0) | 2 (7.7) | ||||||

| 2 (7.7) | 0 (.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (.0) | 1 (3.9) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| White | 30 (47.6) | .525 (.60) | 46 (73.0) | 1.221 (.22) | 37 (58.7) | .546 (.59) | 42 (66.7) | −1.116 (.26) | 32 (50.8) | −.134 (.89) |

| 23 (36.5) | 14 (22.2) | 20 (31.8) | 16 (25.4) | 26 (41.3) | ||||||

| 4 (6.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 5 (7.9) | ||||||

| 3 (4.8) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (3.2) | 3 (4.8) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 3 (4.8) | 0 (.0) | 3 (4.8) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Other | 1 (11.1) | −2.580 (.01) | 3 (33.3) | −2.334 (.02) | 3 (33.3) | −1.824 (.07) | 3 (33.3) | −2.652 (<.01) | 2 (22.2) | −2.328 (.02) |

| 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (33.3) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) | ||||||

| 1 (11.1) | 0 (.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | ||||||

| 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (11.1) | ||||||

| 2 (22.2) | 0 (.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 7 (36.8) | −1.802 (.07) | 9 (47.4) | −2.350 (.02) | 9 (47.4) | −1.579 (.11) | 7 (36.8) | −3.577 (<.01) | 4 (21.1) | −3.802 (<.01) |

| 4 (21.1) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (21.1) | 9 (47.4) | 8 (42.1) | ||||||

| 4 (21.1) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (26.3) | ||||||

| 1 (5.3) | 2 (10.5) | 4 (21.1) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (10.5) | ||||||

| 3 (15.8) | 0 (.0) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 12 (44.4) | −1.152 (.25) | 15 (55.6) | −1.912 (.06) | 16 (59.3) | −.104 (.92) | 18 (66.7) | −.696 (.49) | 14 (51.9) | −.983 (.33) |

| 5 (18.5) | 8 (29.6) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (22.) | ||||||

| 5 (18.5) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 5 (18.5) | ||||||

| 4 (14.8) | 3 (11.1) | 5 (18.5) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | ||||||

| 1 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Female | 37 (48.7) | .924 (.36) | 58 (76.3) | 2.965 (<.01) | 44 (57.9) | .436 (.66) | 56 (73.7) | 1.237 (.22) | 43 (56.6) | 1.763 (.08) |

| 27 (35.5) | 17 (22.4) | 24 (31.6) | 17 (22.4) | 29 (38.2) | ||||||

| 5 (6.6) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (5.3) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (5.3) | ||||||

| 3 (4.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 5 (5.3) | 0 (.0) | 4 (5.3) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| Nonbinary or other | 2 (33.3) | −.341 (.73) | 2 (33.3) | −1.678 (.09) | 4 (66.7) | .671 (.50) | 3 (50.0) | −1.175 (.24) | 1 (16.7) | −1.690 (.09) |

| 3 (50.0) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | ||||||

| 1 (16.7) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

| 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | 0 (.0) | ||||||

Notes. Analyses conducted with complete responses; missing data should be assumed wherever totals do not equal those for the appropriate denominator according to Table 1. P-values examined on a gradience to assess highest importance with bolded boxes representing associations at the P < .05 level. These tests were performed examining each group against all other groups combined.

aAdditional analysis by performance attended suggested respondents who attended the public health professionals performance (n = 14) were less likely to agree that the performance increased their knowledge (z = −2.048; P = .04).

Mann-Whitney U tests suggest some differences in responses based on demographics (Table 2). For example, participants identifying as female were more likely than males or other genders to agree that COVID Monologues represented the reality of the pandemic in the U.S. Compared to non-Hispanic, participants identifying their ethnicity as Hispanic gave more negative responses to all five questions, while participants identifying as Asian generally gave more positive responses.

Participant selections of “which monologue had the strongest impression on you” were fairly well distributed among the eight monologues (votes per monologue: median = 13, min = 7, max = 21). Most participants (87.2%) said they would be interested in attending research-based theater again.

Six decision-makers responded to the one-month follow-up survey, in the non-mutually exclusive sectors of healthcare (n = 2), research (n = 2), education (n = 1), non-profit (n = 1), and government/civil service (n = 1). Five somewhat or strongly agreed that they found themselves thinking about COVID Monologues in their professional lives and that the performance affected the way they thought about their work moving into the future. Two somewhat agreed that the performance influenced a decision they had made in the previous month (neither agree nor disagree [n = 2], somewhat disagree [n = 1], strongly disagree [n = 1]).

Qualitative Responses

In explaining their selection for which monologue had the “strongest impression” on them, audiences most often described how the central character helped them better understand what others or they themselves were going through during the pandemic. Often, these comments included an appreciation for how “real” the character and their situation seemed. Many participants explained how a character brought them a viewpoint that they had not yet considered:

“[‘Get Ready With Me’ was an] insightful snapshot of what teens, especially diverse teens are going through. Broke my heart when they had to quickly remove their makeup before their mom saw them” (Female, 50-59 years old).

“Hearing a character with HIV talk about COVID was a powerful perspective that I hadn't previously encountered” (Female, 20-29 years old).

Others described how the character reminded them of someone they knew, often adding that the monologue aided them in understanding the experiences of their family or friends.

“Really enjoyed this piece [‘I’m Old School’] because it made me think of my own family members and how we aren't able to see each other in person but we zoom call frequently. This reminded me to check up on my friends and family even if it's a quick hello, how are you” (Female, 13-19 years old).

“I don't often get to catch up with friends that are healthcare workers to hear their experiences” (Female, 30-39 years old, White, explaining why ‘Dance of the Dead Inside’ made the strongest impression on her).

Many described how a character in a monologue increased their self-awareness.

“It [‘How to be a Carved Horse’] tapped into thoughts and feelings I've had on the pandemic, but in a more eloquent and effective manner than I could muster” (Male, 20-29 years old).

“I'm in high school and the way they portrayed a girl and social media made me realize how I felt. This is why I can relate to that monologue [‘Angel’] so much” (Female, 13-19 years old).

In other responses to the “strongest impression” as well as the open comments box, audiences commented on the emotional tone and impact of the production, the diversity of characters and topics, new information they learned, their thoughts about research-based theater, and the artistic quality of the production. Many audience members described watching the monologues as emotional and even cathartic, often in how the character’s perspective or insight reflected their own pandemic experience.

“I had to take some time after viewing to pull myself together enough to answer this survey - the experience brought up pain and grief that I hadn't allowed myself to feel in a while. As a single mom with an autistic daughter, I have to 'keep it together,' so I compartmentalize my pain away. This brought it out. It's good - good to help process, good to be reminded of the many faces of pain throughout this pandemic” (Female, 50-59 years old).

“It is a very glowing reminder of how we use our hope as an outreach to each other […] to watch that actor talk about this reminded me of how strong we all are together and apart” (Female, 13-19 years old).

A few, however, thought the tone was too pessimistic, too political, or compromised its emotional, educational, and artistic goals by reflecting reality too closely.

“If I want to see the same, regurgitated narrative of the liberal media and misquoting of President Trump, I'll turn on CNN” (Male, 60-69 years old).

“Actually, the thing that stood out to me is how there wasn’t anything new […] The characters would monologue about their struggles and I just kind of felt like ‘yeah, you and everyone else,’ and was tired’ (Female, 20-29 years old).

Audience members sometimes commented on the diversity of characters and topics presented, some with appreciation, and others with reservations.

“I also think that (like any other audience) some in a non-public health, non-academic, white heteronormative audience are likely to see the issues addressed in these dialogues as irrelevant to them if they are completely unrepresented” (Male, 50-59 years old).

Some commented on new information they learned or the effectiveness of research-based theater in general in knowledge dissemination or fostering empathy.

“I didn't know about the aspects of the CARES Act and how that affected already marginalized and underfunded communities […]. I felt like this monologue showed me how much I still don't know. […] I think this is really important for any topics where there is shame or stigma that affects outcomes, because you really get to associate yourself with what the character is going through” (Female, 40-49 years old).

“I think this format is a beautiful method of educating a lot of people, and I think it will make a much larger impact than expected. These performances are still true-to-life (not over-dramatized) so I think they will be relatable and ‘hit home’ for many people” (Female, 20-29 years old).

Among those that said they would be interested in attending research-based theater again, some wanted to see an extension of the COVID-19 topics explored in this production (HIV, LGBTQ issues) or new, emerging issues (vaccines). Many were interested in research-based theater´s potential for exploring mental health issues, both related and unrelated to COVID-19. Other topics suggested included the climate crisis, sexual health, police violence, and immigrant and refugee health issues.

While decision-makers did not claim the monologues directly influenced a specific decision they made in their professional role in the one-month follow-up survey, they commonly reported valuing the way the monologues helped them “think of the pandemic and our response to it from different perspectives” (Religious organization leader, Female, 40-49 years old).

“[COVID Monologues] served as a prompt for me to explore specific social factors facing different demographic groups, and the intersectionality of factors at play” (Mental health professional, Female, 40-49 years old).

“I work in health communication, and we think about segmentation of messaging and how the same message and same approach to encouraging a behavior may not resonate for all. Seeing 'lives' of people grappling with the prevention messages and trying to apply them to their own situation was powerful in really driving home the reality of how prevention messaging needs to be contextualized” (Public health researcher, Female, 30-39 years old).

Discussion

COVID Monologues was a unique collaboration between public health researchers and theater professionals that aimed to disseminate research findings and foster empathetic understanding on the societal impact of COVID-19 in the U.S. The project piloted a novel method of knowledge dissemination through research-based theater, as scripts were inspired by published research selected from a systematic review, rather than primary data from a single research project as is typical to the genre. After extracting the main findings, we gave playwrights artistic license to communicate these main findings in a monologue. Through virtual performances, the eight monologues reached a diverse group of viewers. Survey responses suggested that through the performances, audience members gained knowledge, emotional connection to their own experience, and empathetic perspective into the experience of others. Audience members also wished to see research-based theater on other topics of importance in their society.

Survey results suggested that for many audience members, COVID Monologues increased perceived knowledge and fostered empathetic perspective on COVID-19’s societal impact. Further, audience members sometimes saw their own struggles in the characters and valued the opportunity for self-reflection and validation. COVID Monologues was not tailored for any specific audience demographic, but as the characters were created from a wide-scoping literature review and a diverse artistic team, they naturally represented a range of backgrounds and experiences. Yet, character representation did appear to affect audience response by demographic. Quantitative and qualitative data suggested that people who did not see themselves explicitly represented by characters in the monologues (e.g., Hispanics, cisgender men, political conservatives) were more negative in their evaluation of the show. On the other hand, audience members identifying as Asian were more positive in their response, which may be related to one monologue featuring a healthcare worker of Asian ethnicity. At the time, healthcare workers were seen as the pandemic’s heroes in the public eye, a potentially validating role for Asian audience members and a stark contrast to the widespread hostility directed toward Asians since the beginning of the pandemic.

While COVID Monologues did not explicitly seek to promote any behavior change goals, it did have an impact on perceived knowledge, empathy, and self-reflection, which can all lay groundwork for health behavior change. In COVID-19 specifically, empathetic attitudes have been related to behaviors with both societal and individual benefits, like masking and social distancing.21,22 In this way, COVID Monologues may have extended beyond research dissemination (its original intended form) and begun to resemble a work of narrative health communication. Narrative communication can be effective when intentionally created to promote specific behaviors, including avoiding unproven COVID-19 treatments or getting vaccinated. 23 Carefully constructed narratives based on scientific evidence may also be powerful in advocacy, 24 and while our sample of decision-makers was small, they did provide evidence that the monologues changed the way they thought about their work one month later. Narratives are most effective when they feature relatable characters, which COVID Monologues portrayed for some, but not all segments of the audience. In the future, incorporating more elements of narrative communication as well as elements of entertainment-education theory 25 may help us create theater that extends beyond the goal of knowledge translation to move specific audiences toward specific actions.

Limitations to our work lie in both the process of creating COVID Monologues and the audience survey. COVID Monologues was based on a systematic search, though the literature published reflects experiences early in the pandemic when we still knew little about transmission, prevention, treatment, and long-term consequences of COVID-19. Further, publication can be a slow process, particularly for qualitative studies. Because our review took place relatively early in the pandemic, we inevitably missed qualitative insights that were not yet published. Ethical questions are inherent to any research-based theater endeavor, 10 and one limitation of creating work based on published literature is it did not allow direct engagement with original participants to help inform decisions on how findings were represented on stage. Our audience survey represents a doubly self-selected sample (those who chose to attend the performance and those who chose to complete the survey). Publicity on the show was fairly limited, and potential reactions among those unaware of the event or who did not attend might have been different than those who saw it advertised through the channels available to the project team (partner theaters, professional groups, and schools). We estimate survey respondents only represented about one-third of performance attendees, so these responses are not fully generalizable even to those who did see a performance and may over- or under-represent particular views. Additionally, the one-time survey did not allow us to ask follow-up questions to participants when additional explanation could have been helpful in interpreting their responses. Opportunities to engage with different segments of the audience after analyzing initial responses might have furthered our understanding of their reasons for viewing the performance, what they expected from it, and the perspectives they may have wished to see represented. Further, while the 1-month follow-up was designed to learn about the impact of the performance on decision-makers, we may have missed an opportunity to learn about the impact on individual behavior change by not inviting all types of participants to a one-month follow-up.

COVID Monologues aimed to translate central findings of systematically sourced, published qualitative research related to COVID-19 to audiences that do not typically read peer-reviewed journal articles. In providing audiences with new perspectives and allowing them to connect with relatable characters, the performance fulfilled a key objective of qualitative research: deeper, richer insight into the human experience of a public health phenomenon. The products of this insight, perceived knowledge, self-reflection and empathy, which can positively influence pro-social health behaviors. We also recognize that “impact” of research-based theater is challenging to define, as it often reflected beyond measurable audience response, in the experiences of those who created, performed and shared the work. 26 Further research on the perspectives of researchers and artists involved is needed to evaluate the strengths, limitations, and impact of this novel process of research translation. Responding to audience calls to extend this format to other topics, creators of theater based on systematically-sourced research may advance both ends of a spectrum: exploring unexpected impacts that may be harder to measure, while also working toward more specific behavior change outcomes.

So What?

What is Already Known on This Topic?

Qualitative research findings have been successfully shared with a variety of audiences through research-based theater.

What Does This Article Add?

“COVID Monologues” was created with a novel method: using systematically-sourced published studies to inspire a monologue collection. Audience members reported increased knowledge, self-reflection, and empathetic insight from the performance, with more positive reactions from demographics well-represented in monologue characters.

What Are the Implications for Health Promotion Practice or Research?

Research-based theater can be an effective means of disseminating systematically-sourced research, promoting perceived knowledge and fostering emotional insight during public health crises like COVID-19.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Audience Response to COVID Monologues: Research-Based Theater on the Societal Impact of COVID-19 by Emily A. Hurley, Saraniya Tharmarajah, Genevieve de Mahy, Jess Rassp, Joe Salvatore, Jonathan P. Jones, and Steven A. Harvey in American Journal of Health Promotion.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the many collaborators who made this project possible. Playwrights Lane Stanley, Kelleen Conway Blanchard, Reynaldo Piniella, Jessica Kim, Shawn Reddy, Christin Eve Cato, Alli Hartley-Kong, and Tristan B. Willis wrote the monologues. Partner theaters Single Carrot Theatre, Arena Players, Inc, Strand Theater Co, Fells Point Corner Theatre, and Two Strikes Theatre Collective produced the monologues. Ben Pierce, Erin Riley, Mari Andrea Travis, Jess Rassp, Genevieve de Mahy, Aladrian C. Wetzel, Noah Silas, and Lauren Erica Jackson directed the monologues. Actors Christian Gonzalez, O’Malley Steuerman, Karen Chase, Saraniya Tharmarajah, Surasree Das, Marjuan Canady, Valerie Lewis, and B. Kleymeyer performed the monologues. Devin McKay and Mike Jon filmed and edited the performances. Special thanks to Barbara Madison Hauck, Elena Kostakis, Donald Owens, Cori Dioquino, and Alan Rosenberg. The authors also thank audience members who viewed the monologues and shared their opinions in this research.

Author Contributions: EAH, ST, GM, JR, JS, JPJ contributed to the conceptualization and design of the work. EAH and ST contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data. GM, JR, JS, JPJ and SH contributed to the interpretation of the data EAH drafted the manuscript. ST, GM, JR, JS, JPJ and SH revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work funded by a Citizen’s Diplomacy Action Fund by the U.S. Department of State and Children’s Mercy Kansas City. Funding supported artistic consultancies, including co-authors de Mahy and Rassp.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s Mercy Kansas City (#1696).

ORCID iDs

Emily A. Hurley https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1806-075X

Saraniya Tharmarajah https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6186-9995

Joe Salvatore https://orcid.org/0009-0008-1376-6343

Jonathan P. Jones https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2352-8177

Steven A. Harvey https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6936-0213

References

- 1.Eddy CM. The social impact of COVID-19 as perceived by the employees of a UK mental health service. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(S1):1366-1375. doi: 10.1111/inm.12883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van de Groep S, Zanolie K, Green KH, Sweijen SW, Crone EA. A daily diary study on adolescents’ mood, empathy, and prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(10 October):e0240349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali SH, Foreman J, Tozan Y, Capasso A, Jones AM, DiClemente RJ. Trends and predictors of COVID-19 information sources and their relationship with knowledge and beliefs related to the pandemic: nationwide cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Heal Surveill. 2020;6(4):e21071. doi: 10.2196/21071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathje S, Hackel L, Zaki J. Attending live theatre improves empathy, changes attitudes, and leads to pro-social behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2021;95:104138. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossiter K, Kontos P, Colantonio A, Gilbert J, Gray J, Keightley M. Staging data: theatre as a tool for analysis and knowledge transfer in health research. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):130-146. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vindrola-Padros C, Chisnall G, Cooper S, et al. Carrying out rapid qualitative research during a pandemic: emerging lessons from COVID-19. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(14):2192-2204. doi: 10.1177/1049732320951526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teti M, Schatz E, Liebenberg L. Methods in the time of COVID-19: the vital role of qualitative inquiries. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:160940692092096. doi: 10.1177/1609406920920962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belliveau G, Lea GW. Research-Based Theatre: An Artistic Methodology. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray RE. Graduate school never prepared me for this: reflections on the challenges of research-based theatre. Reflective Pract. 2000;1(3):377-390. doi: 10.1080/14623940020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox S, Guillemin M, Nichols J, Prendergast M. Ethics in research-based theater: why stories matter. Qual Inq. Published online June. 2022;1:107780042210976. doi: 10.1177/10778004221097641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vachon W, Salvatore J. Wading the quagmire: aesthetics and ethics in verbatim theater Act 1. Qual Inq. Published online June 6, 2022;29:383-392. doi: 10.1177/10778004221098988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keen S, Todres L. Strategies for disseminating qualitative research findings: three exemplars. Forum Qual Sozialforsch/Forum Qual Soc Res 2007;8(3). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck JL, Belliveau G, Lea GW, Wager a. Delineating a spectrum of research-based theatre. Qual Inq. 2011;17(8):687-700. doi: 10.1177/1077800411415498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray R, Sinding C, Ivonoffski V, Fitch M, Hampson A, Greenberg M. The use of research-based theatre in a project related to metastatic breast cancer. Health Expect. 2000;3(2):137-144. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2000.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell GJ, Jonas-Simpson C, Ivonoffski V. Research-based theatre: the making of I’m Still Here. Nurs Sci Q. 2006;19(3):198-206. doi: 10.1177/0894318406289878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deavere Smith A. Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Other Identities. New York, NY: Dramatists Play Service, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deavere Smith A. Let Me Down Easy. New York, NY: Dramatists Play Service, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deavere Smith A. Notes from the Field. Mumbai: Anchor; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uman LS. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(1):57-59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leavy P. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galang CM, Johnson D, Obhi SS. Exploring the relationship between empathy, self-construal style, and self-reported social distancing tendencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12;588934. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.588934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfattheicher S, Nockur L, Böhm R, Sassenrath C, Petersen MB. The emotional path to action: empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Sci. 2020;31(11):1363-1373. doi: 10.1177/0956797620964422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iles IA, Gaysynsky A, Sylvia Chou WY. Effects of narrative messages on key COVID-19 protective responses: findings from a randomized online experiment. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36(6):934-947. doi: 10.1177/08901171221075612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadlallah R, El-Jardali F, Nomier M, et al. Using narratives to impact health policy-making: a systematic review. Health Res Pol Syst 2019;17(1):1-22. doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0423-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-Education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge; 2012. 10.4324/9781410607119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons JA, Gladstone BM, Gray J, Kontos P. Re-conceptualizing ‘impact’ in art-based health research. J Appl Arts Health. 2017;8(2):155-173. doi: 10.1386/jaah.8.2.155_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Audience Response to COVID Monologues: Research-Based Theater on the Societal Impact of COVID-19 by Emily A. Hurley, Saraniya Tharmarajah, Genevieve de Mahy, Jess Rassp, Joe Salvatore, Jonathan P. Jones, and Steven A. Harvey in American Journal of Health Promotion.