Abstract

Objectives

This study explores the incidence and trends of breast (Bca), corpus uteri (CUca), and ovarian (Oca) cancer in Lebanon, a Middle Eastern country. It compares the Bca rates to regional and global ones and discusses Bca risk factors in Lebanon.

Introduction

Globally, Bca is the premier cause of cancer morbidity and mortality in women.

Methods

Data on female Bca, CUca, and Oca published by the Lebanese national cancer registry were obtained (ie, for the years of 2005 to 2016). The age-standardized incidence rates (ASIRw) and age-specific rates per 100,000 female population were computed.

Results

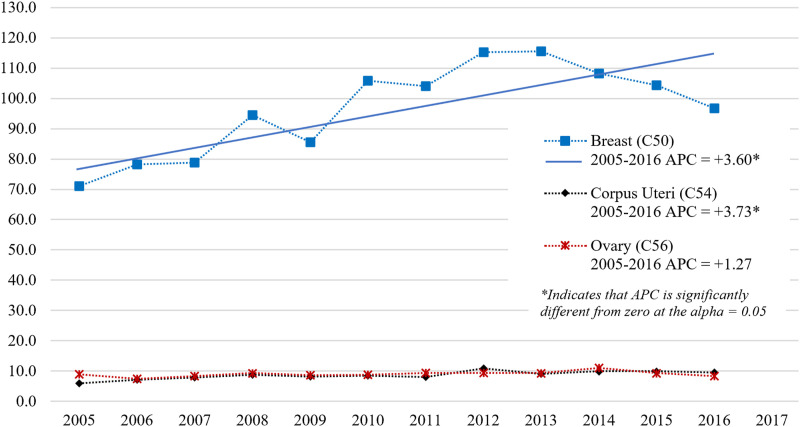

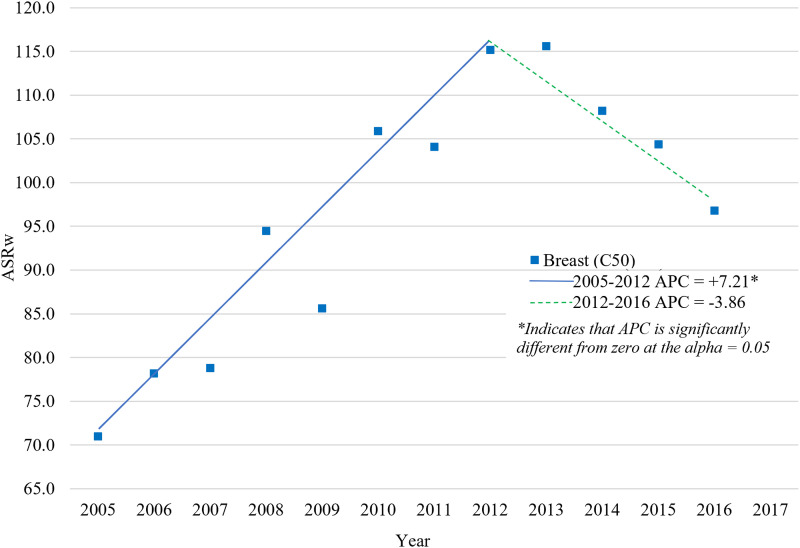

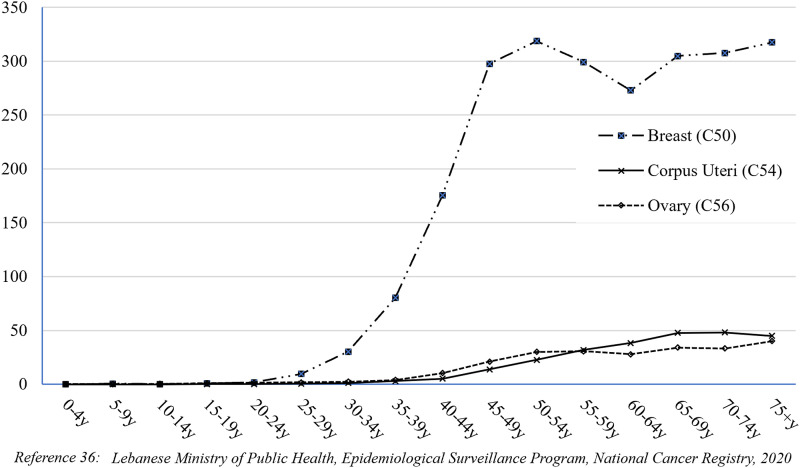

From 2005 to 2016, Bca, Oca, and CUca ranked first, sixth, and seventh, respectively, for cancer incidence among women in Lebanon. Bca alone accounted for 39.4% of all new female cancer cases. The ASIRw increased significantly for Bca and CUca (APC: 3.60 and 3.73, P < .05) but not for Oca (APC: 1.27, P > .05). The Bca ASIRw (per 100,000) increased significantly from 71.0 in 2005 to 115.6 in 2013 (P < .05), then decreased steadily but non-significantly to reach 96.8 in 2016 (P > .05). Lebanon’s Bca ASIRw is comparable to developed countries. This may reflect altered sociological and reproductive patterns as the country transitions from regional to global trends. The five-year age-specific rates analysis revealed that Bca rates rose steeply from 35-39 to 50-54, dropped slightly between 55 and 64, then rose till 75+. The five-year age-specific rates between 35 and 54 among Lebanese women were amongst the highest worldwide from 2008 to 2012, even higher than the rates in Belgium, which had the highest ASIRw of Bca worldwide in 2020.

Conclusion

Lebanon’s Bca ASIRw is among the highest globally. It’s important to investigate the contributing factors and develop a national Bca control strategy. This study supports the national recommendation in initiating Bca screening at age 40 for women.

Keywords: breast cancer, epidemiology, incidence, prevention, risk-factors, screening, early detection

Introduction

Breast cancer (Bca) is the most common cancer in women (24.5% of all female cancers), and has recently surpassed lung cancer as the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world for the first time in 2020 (representing 11.7% of all new cancer cases).1,2 Bca incidence increased from 1.38 million in 2008 to 1.67 million in 2012, 2.1 million in 2018, and 2.3 million new cases in 2020 (ie, a 130% increase since 2008).1–5 Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Estimates 2016, cancers are the leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for women, of which 18% (19.6 million DALYs) are due to Bca. 6 Bca is also the leading cause of female cancer-related mortality worldwide (15.5% of female cancer deaths and 6.9% of cancer deaths in all people in 2020), accounting for around 458,000 deaths in 2008, 522,000 in 2012, 626,679 in 2018, and 685,000 deaths in 2020 (ie, a 50% increase since 2008).1–5 Bca projected Age-Standardized incidence Rate adjusted to the world population (ASIRw) per 100,000 female years also increased over time (ASIRw: 47.8 in 2020, 46.3 in 2018, 43.3 in 2012, and 39.0 in 2008).1–5

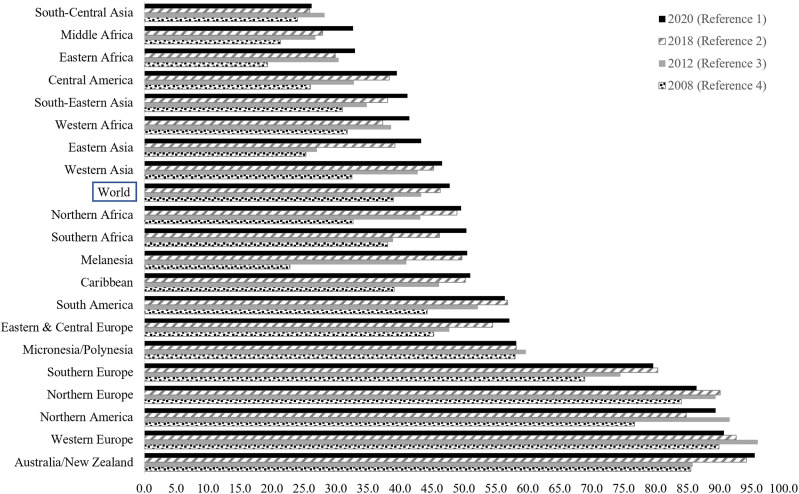

The ASIRw of Bca varies by a factor of four across regions.1,2 It is strongly associated with the population standard human development index (HDI). HDI measures a country average achievement in three core dimensions of human development (ie, having a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable, and having a decent standard of living). 7 Very-high and high HDI countries had the highest estimated ASIRw of Bca in 2020 (55.9) compared to medium- and low-HDI countries (29.7). 2 In 2020, developed Western countries had the highest Bca incidence (>80 per 100,000 females). The highest Bca incidence for 2020 (>80 per 100,000 females) was in developed Western countries, that is, Australia/New Zealand (ASIRw: 95.5), followed by Western Europe (ASIRw: 90.7), Northern America (ASIRw: 89.4), and Northern Europe (ASIRw: 86.4). Bca lowest incidence for 2020 (<40 per 100,000 female) were in South-Central Asia, Eastern and Middle Africa, and Central America (Figure 1).1,2 The elevated ASIRw of Bca in the higher HDI countries is mainly attributed to higher exposure to reproductive, hormonal, and lifestyle risk factors, besides advances in early detection and diagnosis and better reporting.2,8 Reproductive and hormonal risk factors include a younger age of menarche, an older age of first full-term pregnancy, decreased parity, less breastfeeding, an older age of menopause, and the use of exogenous hormones like menopausal hormone replacement therapy and oral contraceptives. 2,8 Risk factors associated with lifestyle encompass increased alcohol consumption, excessive postmenopausal body weight, lack of physical activity, both active and passive smoking, and elevated fasting plasma glucose levels.2,8,9 Additionally, better Bca detection facilitated by widespread mammographic screening contributes to the elevated ASIRw in countries with high HDI. 2,8 In specific European subpopulations and Israel, the high incidence is partially attributed to a notable prevalence of mutations in high-penetrance genes, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, particularly among women of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage, ranging from 1% to 2.5%. 10 Finally, growing evidence indicates that ambient air pollution is a risk factor for Bca.11–19

Figure 1.

Projected Age-Standardized incidence rates per 100,000 (ASRw) of Breast cancer by regions based on Globocan 2008, 2012, 2018 and 2020.

Lebanon is a six million-person developing country in the Middle East (including around 1.6 million displaced people, refugees, and migrants). 20 During the period covered by the data in this manuscript, Lebanon possessed a high Human Development Index (HDI) according to the standard HDI formula, with a value of .757 in 2017. 7 In 2012, it had health indices almost comparable to those of developed countries (eg, Fertility Rate of 2.0, Infant Mortality Rate of 8 per 1000 live births, Maternal Mortality Ratio of 25 per 100,000 live births, and a Female Life Expectancy at Birth of 80.3 years.20–23 Between 2004 and 2008, Bca was the leading female cancer in the country. 24 According to available data, Lebanon had by far the highest rate of BCa incidence among countries in its respective geographic region, whether the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) or the Eastern Mediterranean regions (EMR).24–28 In the period 2004-2008, the five-year age-specific rates for women aged 35 to 49 in Lebanon were among the highest observed globally.24,25 For women at average risk, the Lebanese MoPH recommends screening for Bca annually, starting at the age of 40, whereas most Western countries recommend, starting Bca screening later at the age of 50.24,29–33 Actually, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) drafted a new recommendation statement in May 2023 to start screening at the age of 40 (ie, similar to Lebanon) instead of the age of 50. 34

Objectives

This study examines the 12-year incidence rates and temporal trends of invasive hormone-related women’s cancers in Lebanon, including breast, corpus uteri, and ovarian cancers. It also compares the incidence rates of Bca in Lebanon to its respective geographic region (ie, the MENA region) and other countries/regions worldwide. This study also discusses the various factors contributing to the Bca ASIRw in Lebanon and concludes with recommendations for effective Bca prevention and screening.

Materials & Methods

The Lebanese National Cancer Registry (NCR)

Following years of war, the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) officially reinstated the national cancer registry (NCR) in 2002. While covering over 90% of cancer cases in Lebanon, the NCR does not register in-situ lesions.35,36 For the period 2005-2016, the NCR consistently gathered histologically confirmed data through two systems: the capture system (involving passive data collection from physicians’ reports) and the recapture system (entailing active data collection from histopathological and hematological laboratories).35,36 The NCR publicly disseminates cancer incidence data on the MoPH website, including information from 2005 to 2016. 36

Cancer Incidence Rates from 2005 to 2016

In this cohort study, data include diagnosis with the code of invasive Bca (C50), CUca (C54), and Oca (C56) of the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10). The Age-Standardized Incidence Rate (ASIRw adjusted to the world-standard population by Doll as the reference population), 37 and the age-specific incidence rates, 38 expressed per 100,000 females, were calculated based on figures published by the Lebanese NCR on the MoPH website 36 for twelve consecutive years from 2005 to 2016.

The ASIRw is a weighted mean of age-specific incidence rates per 100,000 individuals, where the weights reflect the proportions of individuals in respective age groups within a standard population. Standardization is crucial when comparing populations with different age distributions. The widely adopted standard population for such comparisons is the “world standard population,” derived from a combined population across various countries. In this investigation, Doll’s modified world standard population was employed to compute the ASIRw. 37 The age-specific incidence rate is determined by dividing the count of new cancer cases within a particular time frame in a population belonging to a specific age and gender category by the mid-year population count of that age and gender group. 38

Statistical Analyses

Twelve-Year Trend Analysis From 2005 Until 2016

The analysis of observed cancer ASIRw trends was conducted using the Joinpoint Regression Program (JRP) version 4.7.0.0. 39 This method utilizes a Monte Carlo permutation approach to identify statistically significant points of trend change (joinpoints) and determine the rate of change (annual percent change) within each identified trend segment. 39 The JRP calculated the annual percent change (APC) and average annual percent change (AAPC) for Bca, CUca, and Oca incidence rates across the studied years. Additionally, it computed the AAPC for age-specific Bca incidence rates. A P-value less than .05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. 39

Projections of the Bca Incidence Using Population Growth and Bca Trends

Projections were derived from the existing Bca data spanning from 2005 to 2016. In this study, linear and log-linear regression models were identified as the most suitable models. The linear model was employed to project future trends in Bca incidence. Both of these models, assuming a Poisson distribution for the observed incident cases, are recognized as practical approaches for estimating cancer incidence patterns for up to a 10-year period, under the assumption that there is no alteration in the underlying trends. 40 Linear regression model was also used by Globocan 2020 for short-term estimates. 41

The R-squared (R2 or coefficient of determination) and the Standard Error of Estimate were utilized to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit. R2 enables the measurement of how effectively the model accounts for overall variations, indicating the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable (ASIRw) explained by the independent variable (year). Essentially, R2 reflects the degree to which the data align with the regression model, representing the model’s goodness of fit. Additionally, the P-value for the model was calculated to assess its significance in comparison to a null model, indicating whether there is a meaningful relationship between the independent and dependent variables as defined by the model. Both the linear and log-linear models yielded P-values less than .001, signifying statistical significance (below .05).

Projections of female Bca incidence rates from 2005-2016 to 2020 were conducted using the female population distribution by age group estimated by the Central Agency for Statistics (CAS) for 2019, as utilized by the MoPH Epidemiological Surveillance Program (ESP), 42 and excluding Syrian refugees. These figures were the best estimates of the Lebanese population at that time.

Comparison of Bca, Oca and CUca Incidence Rates in Lebanon to Other Countries

Subsequently, this study compared the ASIRw and age-specific rates of Bca in Lebanon with rates from various regional and global countries. The selected countries had available cancer data for a similar timeframe, sourced from databases such as Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Time Trends (CI5plus), 43 Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Volume XI (CI5XI), 44 or from Regional or Country National Cancer Registries.45–47 Notably, the reported rates in CI5plus and CI5XI were derived from high-quality, population-based cancer registries. For comparison purposes, this study encompassed countries located in close proximity to Lebanon, along with randomly chosen countries from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and other global regions. The selection process did not exclude countries with the highest global ASIRw for Bca. 1

Results

Twelve-Year Trend Analysis from 2005 until 2016

Over 12 years (2005-2016), Bca was the most common cancer in Lebanon (20.5% of all new cancer cases) and leading cancer in females (39.4% of all new female cancer cases). Other female cancers were also common, with Oca ranking sixth and CUca ranking seventh.

During the study period, there was a 56.0% increase in the total count of female Bca incidence cases, rising from 1451 cases in 2005 to 2264 cases in 2016. Concurrently, the total count of CUca cases surged by 81.7%, rising from 120 cases in 2005 to 218 cases in 2016. In contrast, the total count of Oca cases saw a more modest 6.6% increase, rising from 182 cases in 2005 to 194 cases in 2016.

The APC was calculated for all participants in the study to represent the trends in ASIRw for female Bca, CUca, and Oca over the entire 12-year study duration. With a 0 Joinpoints model, Bca and CUca ASIRw increased significantly during the period 2005-2016 (AAPC = APC: +3.60 and +3.73, respectively, P-value <.05), while the Oca ASIRw increased insignificantly in the same period (APC: +1.27, P-value >.05) (Figure 2). The best model, however, was the 1 Joinpoint model, which identified two trends in the Lebanese ASIRw of Bca in females: a significant increase in the period 2005-2012 (APC: 7.21, P-value <.05) with peaks in 2012 and 2013 (115.2 and 115.6, respectively), followed by a non-significant decrease during the period 2013-2016 (APC: −3.86, P-value >.05) to reach 96.8 in 2016 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Age-Standardized Incidence Rates (World Population) per 100,000 Females for Breast, Corpus Uteri and Ovary Cancers in Lebanon for the Years 2005-2016 Model: 0 JoinPoints.

Figure 3.

Age-Standardized Incidence Rates (World Population) per 100,000 Females for Breast, Corpus Uteri and Ovary Cancers in Lebanon for the Years 2005-2016 Final selected model: 1 JoinPoints.

The APC was also calculated for the age-specific Bca incidence rates and revealed that female Bca in Lebanon increased significantly in all age groups over 50 during the study period (Table 1). Bca rates rose sharply between the ages of 35 and 39 and reached their first peak between 50 and 54 years. They then dropped a little between 55 and 64 years old before rising again to a second peak at 75+ age group (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Breast cancer Age-Standardized Incidence Rate (World Population) and Age-Specific Incidence Rates among Females in Lebanon in the years 2005-2016.

| Year | ASRw | 25-29y | 30-34y | 35-39y | 40-44y | 45-49y | 50-54y | 55-59y | 60-64y | 65-69y | 70-74y | 75+y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 71.0 | 9.7 | 31.6 | 75.3 | 149.8 | 175.9 | 246.3 | 202.8 | 207.2 | 215.5 | 226.0 | 217.5 |

| 2006 | 78.2 | 9.0 | 27.1 | 86.1 | 136.4 | 226.8 | 222.7 | 264.3 | 231.4 | 238.4 | 236.1 | 289.9 |

| 2007 | 78.8 | 4.2 | 35.8 | 80.9 | 171.2 | 213.2 | 246.0 | 271.1 | 227.6 | 209.9 | 258.1 | 225.5 |

| 2008 | 94.5 | 9.9 | 19.3 | 77.8 | 199.7 | 329.6 | 273.6 | 270.7 | 257.3 | 317.9 | 302.7 | 266.5 |

| 2009 | 85.6 | 10.8 | 29.5 | 87.7 | 167.9 | 280.2 | 237.1 | 239.2 | 240.2 | 290.9 | 261.5 | 283.8 |

| 2010 | 105.9 | 11.6 | 33.9 | 82.0 | 200.5 | 366.6 | 338.6 | 344.3 | 295.7 | 324.4 | 299.3 | 282.7 |

| 2011 | 104.1 | 6.8 | 26.4 | 91.6 | 184.8 | 362.8 | 349.6 | 314.1 | 244.5 | 313.4 | 340.9 | 374.0 |

| 2012 | 115.2 | 9.7 | 34.9 | 84.6 | 228.1 | 374.1 | 405.0 | 318.3 | 301.9 | 362.0 | 357.7 | 390.1 |

| 2013 | 115.6 | 7.1 | 29.0 | 87.6 | 177.2 | 388.7 | 399.8 | 346.0 | 361.0 | 393.2 | 359.5 | 341.8 |

| 2014 | 108.2 | 13.8 | 35.0 | 69.0 | 165.8 | 294.2 | 382.7 | 336.9 | 328.9 | 346.5 | 373.9 | 419.2 |

| 2015 | 104.4 | 10.0 | 32.8 | 73.2 | 160.8 | 311.7 | 387.0 | 352.2 | 278.0 | 308.7 | 374.9 | 369.8 |

| 2016 | 96.8 | 11.8 | 28.1 | 66.2 | 161.4 | 247.0 | 336.6 | 331.8 | 302.2 | 339.6 | 303.3 | 349.6 |

| Average | 96.5 | 9.5 | 30.3 | 80.2 | 175.3 | 297.6 | 318.8 | 299.3 | 273.0 | 305.0 | 307.8 | 317.5 |

| APC | 3.60* | 3.2 | 0.9 | -1.2 | 0.81 | 3.75 | 5.40* | 4.11* | 3.76* | 4.48* | 4.26* | 5.10* |

*Indicates that APC is significantly different from zero at the alpha = 0.05 level.

Figure 4.

Age-specific incidence rates (per 100,000 Females) for breast, Corpus Uteri and Ovary Cancers in Lebanon 2005-2016.

Projected ASIRw of Bca in 2020

Using a linear regression model (R2: .85, Standard error of estimate: 153.9, P < .001), the ASIRw of female Bca was projected to be 102.7 per 100,000 female population in 2020, with an uncertainty interval (UI) ranging from 73.8 to 131.9. The total number of Bca cases is expected to rise from 2264 in 2016 to around 2616 in 2020.

Comparison of Bca, Oca and CUca Incidence Rates in Lebanon to Other Countries

Lebanon has a high Bca ASIRw that is comparable to developed countries. Between 2008 and 2012, Lebanon’s ASIRw of Bca was 101.1, the highest in the MENA region and among the highest worldwide (Table 2).43–47 Lebanon’s ASIRw of Oca (9.1 in 2008-2012) was the highest in the MENA region, one of the highest worldwide, and almost comparable to some Western countries (eg, 9.0 in the US in 2008-2012).43–47 In 2008-2012, the ASIRw of CUca in Lebanon (8.9) was one of the highest in the MENA region (after Israeli Jews: 14.9, Israeli non-Jews: 14.1, and Kuwaiti female population: 9.4), but much lower than the ASIRw reported in Western countries (eg, 19.8 in the US).43–47 Again, the comparison was with studies of some countries in the MENA region that are not representative of the entire population (eg, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Morocco and Algeria).44–46

Table 2.

Annual Incidence Rates (per 100,000) of Breast Cancer in Females of different Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and non-MENA countries.

| Country(reference) | Year(s) | Annual Incidence per 100,000 by Age Group: Females | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASRw | 20-24y | 25-29y | 30-34y | 35-39y | 40-44y | 45-49y | 50-54y | 55-59y | 60-64y | 65-69y | 70-74y | 75+y | ||||

| MENA Countries | West Asia | Lebanon 36 | 2008-2012 | 101.1 | 1.9 | 9.8 | 28.8 | 84.7 | 196.2 | 342.7 | 320.8 | 297.3 | 267.9 | 321.7 | 312.4 | 319.4 |

| Israeli Non-Jews 43 | 2008-2012 | 63.4 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 28.0 | 58.6 | 96.3 | 144.8 | 187.8 | 189.7 | 236.8 | 239.8 | 258.1 | 220.5 | ||

| Israeli Jews 43 | 2008-2012 | 89.1 | 2.2 | 8.4 | 32.9 | 76.5 | 127.7 | 194.8 | 238.9 | 256.8 | 341.3 | 397.3 | 403.5 | 320.7 | ||

| Jordan, Jordanians 44 | 2008-2012 | 51.5 | 0.9 | 6.3 | 19.7 | 45.3 | 94.7 | 140.6 | 154.0 | 142.0 | 196.8 | 166.1 | 156.2 | 148.9 | ||

| Kuwait-Kuwaiti 43 | 2008-2012 | 58.2 | 1.1 | 6.5 | 22.5 | 32.6 | 81.8 | 151.4 | 157.6 | 199.9 | 244.4 | 226.1 | 211.3 | 179.1 | ||

| Bahrain, Bahraini 43 | 2008-2012 | 50.3 | 0.8 | 6.8 | 21.1 | 55.7 | 83.6 | 113.5 | 174.9 | 164.0 | 176.8 | 161.3 | 169.7 | 134.8 | ||

| Qatar, Qatari 44 | 2008-2012 | 53.8 | 1.9 | 10.4 | 21.4 | 46.1 | 115.4 | 106.0 | 180.9 | 217.8 | 131.6 | 177.9 | 230.8 | 127.0 | ||

| Saudi Arabia, Riyadh: Saudi 44 | 2008-2012 | 24.5 | 1.4 | 6.8 | 14.6 | 23.0 | 48.0 | 64.9 | 55.9 | 69.1 | 89.5 | 99.0 | 78.5 | 58.8 | ||

| Iran (Golestan) 44 | 2008-2011 | 30.5 | 4.6 | 10.8 | 23.6 | 48.4 | 78.0 | 88.2 | 97.4 | 82.6 | 71.0 | 57.2 | 42.9 | 66.3 | ||

| North Africa | Egypt (Minia Governorate) 45 | 2009 | 35.7 | 4.2 | 14.0 | 28.3 | 42.5 | 56.0 | 83.1 | 109.7 | 112.2 | 145.9 | 85.9 | 81.6 | 83.5 | |

| Egypt (Aswan Governorate) 45 | 2008 | 63.9 | 4.2 | 13.7 | 28.9 | 57.8 | 140.0 | 99.1 | 220.7 | 220.6 | 184.4 | 181.7 | 215.1 | 296.9 | ||

| Egypt (Damietta Governorate) 45 | 2009 | 41.4 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 29.5 | 49.6 | 78.2 | 116.7 | 107.8 | 142.3 | 127.1 | 151.7 | 93.5 | 89.9 | ||

| Algeria (Setif) 44 | 2008-2011 | 44.7 | 2.9 | 9.5 | 34.9 | 72.7 | 115.7 | 134.4 | 124.6 | 103.7 | 134.7 | 122.3 | 76.4 | 57.9 | ||

| Algeria (Batna) 44 | 2008-2012 | 25.9 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 18.8 | 43.3 | 71.4 | 83.9 | 70.1 | 76.4 | 60.8 | 48.4 | 65.3 | 43.7 | ||

| Morocco (Casablanca) 46 | 2005-2007 | 36.4 | 0.5 | 6.8 | 18.1 | 52.8 | 96.8 | 106.1 | 108.2 | 108.5 | 103.2 | 86.5 | 85.9 | 53.2 | ||

| Non-MENA Countries | Europe | Cyprus 43 | 2008-2012 | 78.6 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 25.1 | 68.5 | 130.0 | 197.2 | 218.9 | 233.3 | 296.1 | 301.7 | 291.6 | 288.5 |

| Turkey (2 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 44.9 | 1.1 | 8.0 | 24.2 | 51.5 | 87.8 | 119.0 | 127.0 | 126.3 | 142.7 | 158.3 | 142.9 | 127.5 | ||

| Bulgaria 43 | 2008-2012 | 54.5 | 1.0 | 7.8 | 23.7 | 54.0 | 89.3 | 128.6 | 141.8 | 170.7 | 207.5 | 210.8 | 197.0 | 178.0 | ||

| Croatia 43 | 2008-2012 | 63.2 | 1.2 | 8.5 | 23.3 | 46.7 | 94.7 | 131.4 | 175.0 | 205.2 | 253.5 | 261.8 | 235.2 | 247.6 | ||

| Czech Republic 43 | 2008-2012 | 65.3 | 1.4 | 8.2 | 20.7 | 43.2 | 79.6 | 142.7 | 168.5 | 196.7 | 260.0 | 281.1 | 297.4 | 314.5 | ||

| Poland, Kielce 43 | 2008-2012 | 43.4 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 10.4 | 31.2 | 69.5 | 110.4 | 130.5 | 159.0 | 173.3 | 158.9 | 129.2 | 119.7 | ||

| Malta 43 | 2008-2012 | 81.2 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 23.2 | 50.5 | 110.1 | 188.0 | 220.1 | 314.0 | 274.8 | 297.5 | 344.6 | 401.5 | ||

| Italy (8 registries) 43 | 2008-2010 | 92.7 | 1.8 | 9.6 | 31.5 | 67.0 | 147.3 | 240.2 | 264.2 | 269.0 | 329.6 | 404.3 | 327.0 | 339.1 | ||

| Switzerland (6 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 87.5 | 0.3 | 8.0 | 26.8 | 64.6 | 113.7 | 191.3 | 242.8 | 252.0 | 332.0 | 429.5 | 376.3 | 355.0 | ||

| Germany (2 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 95.7 | 1.4 | 10.9 | 28.1 | 60.4 | 124.3 | 196.9 | 255.5 | 317.9 | 393.3 | 469.8 | 372.5 | 370.5 | ||

| Belgium 44 | 2008-2012 | 109.2 | 1.9 | 12.3 | 37.2 | 80.0 | 161.7 | 258.0 | 320.5 | 349.0 | 424.8 | 440.8 | 389.2 | 391.8 | ||

| France (9 registries) 43 | 2008-2011 | 97.0 | 1.9 | 10.7 | 34.8 | 79.2 | 160.1 | 243.2 | 270.4 | 281.1 | 355.8 | 401.1 | 394.8 | 303.6 | ||

| Spain (9 registries) 43 | 2008-2010 | 65.2 | 1.4 | 7.9 | 23.2 | 56.3 | 118.0 | 181.3 | 201.9 | 195.5 | 216.9 | 227.2 | 186.9 | 227.0 | ||

| Denmark 43 | 2008-2012 | 101.3 | 1.1 | 8.2 | 29.9 | 57.3 | 114 | 181.9 | 294.5 | 347.8 | 456.3 | 521.1 | 364.6 | 387.0 | ||

| Nordic Countries 47 | 2008-2012 | 86.3 | 1.1 | 7.2 | 24.0 | 50.8 | 106.8 | 179.9 | 253.6 | 282.5 | 370.1 | 406.7 | 332.0 | 313.0 | ||

| UK, England 43 | 2008-2012 | 87.4 | 1.6 | 8.9 | 26.1 | 60.4 | 118.5 | 203.8 | 264.7 | 260.8 | 334.1 | 376.9 | 300.7 | 382.9 | ||

| America | Canada (excl. Nunavut, Quebec and Yukon) 43 | 2008-2012 | 79.4 | 1.8 | 8.0 | 22.9 | 53.2 | 106.4 | 164.0 | 202.9 | 238.6 | 308.3 | 365.3 | 380.8 | 360.2 | |

| USA, SEER (9 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 85.7 | 1.6 | 8.8 | 27.1 | 61.9 | 123.1 | 187.4 | 218.2 | 246.6 | 323.8 | 388.3 | 400.5 | 375.9 | ||

| Colombia, Cali 43 | 2008-2012 | 44.5 | 2.6 | 7.3 | 16.7 | 33.9 | 57.1 | 104.3 | 113.5 | 139.3 | 161.4 | 183.5 | 176.5 | 198.9 | ||

| Costa Rica 43 | 2008-2011 | 42.3 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 14.2 | 30.2 | 63.3 | 86.2 | 106.6 | 134.1 | 163.3 | 191.4 | 181.0 | 180 | ||

| Ecuador, Quito 43 | 2008-2012 | 38.5 | 1.0 | 3.5 | 15.7 | 30.1 | 48.6 | 87.1 | 112.8 | 140.1 | 133.2 | 148.0 | 171.8 | 138.5 | ||

| Brazil, Goiania 43 | 2008-2012 | 51.4 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 26.9 | 37.1 | 77.3 | 116.3 | 127.1 | 161.0 | 176.5 | 256.8 | 189.9 | 191.0 | ||

| Asia | India, Chennai 43 | 2008-2012 | 33.8 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 11.2 | 27.8 | 54.9 | 75.8 | 105.7 | 118.7 | 117.9 | 137.9 | 116.7 | 102.2 | |

| China (5 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 44.3 | 1.4 | 5.7 | 18.6 | 44.6 | 87.7 | 129.7 | 136.9 | 132.3 | 141.7 | 137.4 | 131.2 | 118.5 | ||

| Thailand (4 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 25.5 | 0.5 | 5.1 | 14.2 | 33.8 | 49.7 | 76.8 | 84.2 | 83.2 | 75 | 63.7 | 61.6 | 46.8 | ||

| Philippines, Manila 43 | 2008-2012 | 53.6 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 20.6 | 40.8 | 85.1 | 120.2 | 154.7 | 164.9 | 207.5 | 172.8 | 211.3 | 237 | ||

| Korea (5 registries) 43 | 2008-2012 | 44.5 | 1.7 | 9.3 | 27.2 | 63 | 110 | 154 | 141.5 | 123.9 | 118.4 | 98.1 | 83.4 | 51.1 | ||

| Japan (4 registries) 43 | 2008-2010 | 54.0 | 1.0 | 6.2 | 22.9 | 51.1 | 113.1 | 176.7 | 158.4 | 164.3 | 167.8 | 164.4 | 143.8 | 129.7 | ||

| Africa | Uganda, Kampala 43 | 2008-2012 | 29.1 | 1.6 | 6.2 | 15.8 | 33.0 | 37.5 | 84.8 | 94.6 | 91.6 | 103.0 | 90.9 | 65.0 | 62.6 | |

| Kenya, Nairobi 44 | 2008-2012 | 59.0 | 1.4 | 6.2 | 17.9 | 40.1 | 70.6 | 119.2 | 155.1 | 210.9 | 217.7 | 279.0 | 334.9 | 184.6 | ||

| Zimbabwe, Harare: African 44 | 2010-2012 | 41.4 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 8.4 | 33.4 | 72.0 | 88.5 | 94.9 | 140.8 | 140.6 | 183.9 | 218.5 | 87.3 | ||

| South African Republic, Eastern Cape 44 | 2008-2012 | 12.7 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 11.6 | 9.8 | 26.5 | 26.4 | 27.0 | 40.4 | 50.0 | 32.5 | 38.9 | 38.0 | ||

| Australia 43 | 2008-2012 | 85.9 | 1.3 | 6.2 | 25.9 | 61.0 | 122.7 | 197.6 | 246.2 | 260.8 | 343.0 | 380.6 | 321.8 | 316.5 | ||

ASRw: Age Standardized Rate (world); MENA: Middle East and North Africa.

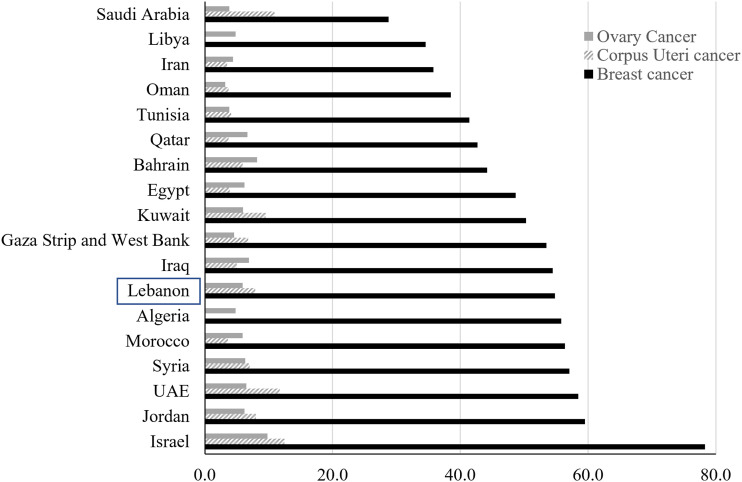

Global Cancer Statistics (IARC/Globocan) revealed that between 2008 and 2020, Bca ASIRw has been increasing worldwide, including in Western Asia, where Lebanon is located (Figure 1).1–5 Figure 5 shows that in 2020, Lebanon continues to have a high Bca ASIRw compared to other Arab countries in the MENA region (Figure 5). 1 However, Globocan 2020 projection figure for Lebanon (Bca ASIRw: 54.8) is much lower than our projection using a linear regression model and the NCR data (Bca ASIRw: 102.7, UI: 73.8 to 131.9). In this study, we projected Bca incidence rates from 2005-2016 to 2020, using the female population distribution by age group estimated by the Central Agency for Statistics (CAS) for 2019, excluding Syrian refugees. 42 On the other hand, Globocan employed a Linear regression model to project Bca incidence rates from 2007-2016 to 2020 and applied them to the 2020 population. 48 Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether they included refugees in their statistics.

Figure 5.

Projected Age-Standardized incidence rates (World Population) per 100,000 of Breast, Corpus Uteri and Ovary Cancers in MENA Countries-Globocan 2020 (Reference 1).

Based on the Lebanese NCR data used in this study, the five-year age-specific rates of Bca among Lebanese women between 35 and 54 years were among the highest observed worldwide during the years 2008 to 2012 (Table 2), even higher than the rates observed in Belgium which is reported to have the highest estimated ASIRw of Bca worldwide by Globocan 2020. 1 Based on the published reports, the peak incidence of Bca in the Middle East occurs at a younger age than in Western countries.25,49–52

Discussion

Bca is the leading female cancer in Lebanon and is still rising. Lebanon’s ASIRw of Bca is among the highest worldwide. It is higher than other countries in the MENA region but remains lower than a few European countries (eg, Belgium, known for having the highest ASIRw of Bca worldwide). The high Bca rates in Lebanon reflect the potential impact of changing social, reproductive, hormonal, and lifestyle patterns from regional standards to Western trends, in addition to advancements in screening/diagnosis, data collection, and environmental pollution. In Lebanon, the relatively high age-specific incidence rates found in age groups younger than 50 years support the current national recommendation to begin screening for Bca at age 40.

Several currently known factors have been described in the literature as being associated with the international variation in the ASIRw of Bca. These factors may not explain all of the Bca cases, and their interactions are not well known. They include the availability and accuracy of cancer registry, discrepancies in the availability and uptake of mammographic screening, differences in population size and age structure, and in the prevalence of Bca genetic mutations and reproductive, hormonal, and lifestyle risk factors (Table 3).2,8,53–65 Environmental and dietary factors may also play a role in this variation.55,61–63 The following currently known factors might have influenced the rise in the female Bca incidence rate in Lebanon (between 2005 and 2016) across all broad age groups (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Table 3.

Female hormone-related cancer risk factorsreference.

| Breast cancer | Corpus Uteri cancer | Ovarian cancer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premenopausal | Postmenopausal | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Females54,55 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Aging54-56 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ||

| Family History and Genetics | ||||

| Family history of Bca or Oca (first-degree relative(s)54-56 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ||

| Family history of CUca53,57,58 or Colon cancer 53 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Inherited mutations in BRCA1, BRCA253-56,59 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ||

| Inherited mutations in DNA repair genes that can interact with BRCA genes including ATM, PALB2, BRIP1, or CHEK2 54 | ||||

| Inherited mutations in TP53 (Li–Fraumeni syndrome)54,59 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Inherited mutations in PTEN (Cowden syndrome)54,59 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ||

| Inherited mutations in MLH1 or MSH2 or MSH6 or PMS2 (Lynch syndrome)53,56,59 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ||

| Inherited pathogenic variants in the STK11 gene (Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome)54,59 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | |

| Inherited neurofibromatosis type 1 syndrome caused by NF1 mutations 59 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Inherited germline mutations in CDH1 (Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer)54,59 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Reproductive factors | ||||

| Early menarche (before the age of 12)53-57 | ↑ the risk* | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk* | |

| Late menarche53-58 | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk* | |

| Late natural menopause (after the age of 55)53-57 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk* | |

| Early menopause53-57 | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk* | |

| Nulliparity53-58 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | |

| First full-term pregnancy over the age of 3053-55 | ↑ the risk** | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Late age at last birth57,58 | ↓ the risk* | |||

| High parity (bearing children)53-59 | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk** | ||

| Medications/Hormones | ||||

| Hormonal contraceptive methods (estrogen & progesterone)^53,58 | ↑ the risk* | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk** | |

| Hormonal contraceptive methods (progesterone only) 42 | ↓ the risk** | |||

| Ovulation Stimulating Drugs55,56 | ↑ the risk? | ↑ the risk* | ||

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy (estrogen & progesterone)53-56,60 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk* | ||

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy (estrogen only)53-58,60 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk* | |

| Tamoxifen53,57,58 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Tubal ligation (sterilisation) 56 | ↓ the risk** | |||

| Bilateral ovariectomy 55 | ↓ the risk** | |||

| Ionising Radiation | ||||

| Ionising radiation exposure particularly during puberty, even at low doses53-55 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Treatment with Radiation Therapy to the pelvis 46 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Lifestyle, Diet and Exercise | ||||

| Greater birthweight 53 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Being tall53,55 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | |

| Breastfeeding53-56 | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Vigorous physical activity 53 | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Physical activity53-55,58 | ↓ the risk* | ↓ the risk** | ↓ the risk** | |

| Sedentary habits53-58 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk* | ↑ the risk* | |

| Body fatness (BMI≥25)53,58 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ||

| Body fatness (BMI≥25) in young adulthood (18 and 30 years) 53 | ↓ the risk** | |||

| Body fatness (BMI≥25) through adulthood (before the menopause)53,58 | ↓ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk** | |

| Adult weight gain 53 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Alcoholic drinks53-55 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Non-starchy vegetables (greater intake)53,56 | ↓ the risk* | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Foods containing carotenoids (greater intake) 53 | ↓ the risk* | |||

| Dairy products53,56 | ↓ the risk* | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Diets high in calcium53,56 | ↓ the risk* | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Cholesterol or Saturated fat (higher intake)55,56 | ↑ the risk** | ↑ the risk* | ||

| Plant-based phytoestrogens 56 | ↓ the risk* | |||

| Coffee (greater intake)53,58 | ↓ the risk** | |||

| Glycemic load 53 | ↑ the risk** | |||

| Smoking Tobacco53-58 | ↑ the risk* | ↓ the risk* | ↑ the risk** | |

| Pre-existing Medical Conditions | ||||

| Serum Vitamin D (within normal ranges)54,56 | ↓ the risk* | ↓ the risk* | ||

| Diabetes Mellitus55,57,58 | ↑ the risk* | ↑ the risk* | ||

| Hypertension57,58 | ↑ the risk* | |||

| Metformin use 58 | ↓ the risk* | |||

| Others | ||||

| Air pollution11-17,55 | ↑ the risk* | |||

| Night work 55 | ↑ the risk* | |||

**strong evidence; *some evidence; ?controversial.

Enhanced Technology and Improved Bca Screening Rates in Lebanon

The Lebanese MoPH has held annual awareness campaigns since 2002, which recommend yearly screening starting at the age of 40. These campaigns increased Lebanese women awareness of early signs of Bca and increased mammography screening rates. 24 By 2013, ever-utilization was 43%, and recent mammography was 20% nationwide, far behind a nationally defined goal of 80% screening coverage. 66

In developed nations, organized mammographic screening programs led to higher detection rates of Bca.61–63 Furthermore, changes in reproductive factors (eg, increased use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapies (HRT),61–63 as well as the introduction of population screening in the 1980s and 1990s, have resulted in a sharp increase in incidence rates for several Western countries.61–64 Since around 2000, the overall incidence rates have remained significantly higher than expected worldwide, despite a decrease or stabilization in several developed countries till 2007, partly due to the lower use of combined postmenopausal HRT, a plateau in participation rates for mammographic screening, and a decline in the pool of cases diagnosed by screening before becoming symptomatic.61–65 In Lebanon, Bca ASIRw did not did not show signs of reaching a plateau by 2013, and Bca screening participation rates continued to rise, particularly among those aged 50 to 59. 66 However, Figure 3 indicated a non-significant decreasing trend from 2012 to 2016, suggesting a possible plateau, although forthcoming data will provide clarification on this trend. Furthermore, because postmenopausal HRT was not used as widely used in Lebanon 67 as it was in Western countries (eg, the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK), France, and Australia), 62 its effect on the rise in incidence rates between 1998 and 2006 was minimal, even among women aged 50 to 59.

Another factor contributing to the rise in incidence rates is the introduction of advanced Bca screening methods into the Lebanese market, such as digital mammography, which improved cancer detection rates. Digital mammography outperforms conventional film mammography in terms of accuracy and cancer detection in women under the age of 50, women with dense breast tissue, and women who are premenopausal or perimenopausal.68–70 Mammography remains the gold standard for Bca screening. 29 The United States Preventive Services Taskforce does not recommend adjunctive Bca screening tests. 29 However, patients and healthcare professionals have become more aware of mammography limitations, particularly in women with high-density breast tissue. This awareness, as in developed countries, led to increase adjunctive Bca screening/early detection in Lebanon, using digital breast tomosynthesis, breast ultrasonography, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).68–71 Moreover, several software-based models were also introduced to estimate a woman’s lifetime risk for Bca based on family history and other risk factors to detect women at high risk for Bca (ie, those eligible for screening breast MRI annually starting at age 30 if their lifetime risk is 20%–25% or more).72–74

In Lebanon, the steepest increase in Bca incidence by age group was primarily in women over 40 (between 2005 and 2016), which corresponds to the target population of national awareness campaigns. The aforementioned factors all played a role in the high Bca ASIRw in women aged 40 to 49. Furthermore, the elevated ASIRw in women aged 35 to 39 years can be explained in part by some Lebanese gynecologists’ recommendation to begin screening at the age of 35 and by increasing women’s awareness of the early signs of Bca (ie, after the campaigns), particularly in those with a family history of Bca.

Incomplete reporting and limited screening have probably resulted in the low rates seen in the Arab countries of the MENA region.49,54,65,75,76

High-Density Breast Tissue

Mammographic density is an independent Bca risk factor. 77 Breast density (heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts) is the most prevalent risk factor for premenopausal and postmenopausal women in the USA. 78 It had the largest effect on population attributable risk proportion fraction (PAF: 39.3% of premenopausal and 26.2% of postmenopausal). 78 Around 50% of 40-and-older women in the US with mammograms have heterogeneously or extremely dense breast tissue. 77 Genes and other factors can affect breast density. Increasing age, having children, and using Tamoxifen lower breast density. A higher breast density is associated with using postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT), having a low body mass index (BMI), a high alcohol intake (more than 7 servings per week, especially in those with a BMI of less than 25 kg/m2), a high dependence on western diet patterns, and a high protein and fat intake. 77 By increasing breast density, these factors may also increase Bca risk. 77 A retrospective multicenter study found that the distribution of breast density in Lebanon is comparable to Western countries. 79 It also showed that high breast density was statistically associated with Bca, particularly in older and menopausal women. 79 Since screening mammography has lower sensitivity and specificity for women with increased breast density, supplemental screening for this group is a common practice in Lebanon. A systematic review for the USPTF in 2016 concluded that in general, supplemental screening of women with dense breasts will lead to the identification of more breast cancers (mostly invasive), but may be associated with higher recall rates and additional biopsies. 80

Lebanese Women Demographics

The worldwide number of new Bca cases was almost similar in more developed and less developed countries in 2008, and slightly higher in less developed countries in 2012. Nonetheless, different population sizes and age structures resulted in lower ASIRw in less developed countries than in developed ones (29.3 vs 71.7 in 2008, 31.3 vs 74.1 in 2012).3,4 The proportion of women younger than 50 years in Lebanon in the years 2008-2012 (82.1%) is higher than the ones reported in the same period in western countries with the highest ASIRw of Bca like Belgium (61.3%), the Netherlands (62.9%), France (61.6%), Denmark (62.3%), the UK (63.8%), the US (66.4%), and Australia (67.6%). 81 This may partly explain the highest age-specific rates among women below 50 in Lebanon.

Since 1998, the demographics of Lebanese women have shifted, primarily due to an increase in life expectancy at birth,23,81,82 which may have contributed to the high rate of Bca among elderly women.

In 2008-2012, the average life expectancy at birth for females was 80.3 years in Lebanon, compared to 76.1 years in the MENA region. It is among the highest in the region (following Israel at 83.4 years and Qatar at 80.7 years) and slightly lower than in Western countries (like the USA: 81.0 years). 23

Changes in Reproductive and Hormonal and Lifestyle Risk Factors

These Bca risk factors are more prevalent in more developed countries than in less developed ones. These risk factors include reproductive risk factors that increase a woman’s lifetime estrogen exposure (ie, early menarche before the age of 12, having children (if any) at an older age, and menopause after the age of 55, and exogenous hormone use (HRT in postmenopausal women, and probably oral contraceptive pills ‘OCP’ in premenopausal women); lack of breastfeeding; excess body weight (body fatness); poor physical activity; excessive alcohol consumption; and environmental pollution.53–60,62–64 These Bca risk factors are also prevalent in Lebanon,83–88 except for alcohol consumption, 89 OCPs 90 and HRT use. 67

Changes in Reproductive Risk Factors

Reproductive factors among females in Lebanon differ from those in neighboring Arab countries and share more similarities with those in Western developed countries. The age at which natural menopause occurs in Lebanon aligns with the median ages reported for women in industrialized countries, ranging from 49.3 to 51.4 years. 91 During the period of 2008-2012, the average total fertility rate per woman in Lebanon was 2.0, lower than the regional average of 2.9 and the global average of 2.5. 22 In Lebanon, the median age for females at marriage was 28.9 years, and there was a relatively high number of single nulliparous women. 82 The latest WHO STEPS survey in 2016-2017 revealed that 29.3% of Lebanese aged 18-44 and 17.9% of Lebanese women aged 18-69 had never been married. 83

Exogenous Hormone Use

Various modern contraceptive methods are easily accessible at low prices and without a prescription in Lebanon (ie, products or medical procedures that interfere with reproduction from acts of sexual intercourse to space or limit birth). Despite this accessibility, Lebanon’s any and modern contraceptive-use rates among women aged 15 to 49 years in 2009 were relatively low (53.7% and 46.8%, respectively) compared to the rates in the MENA region (63.3% and 51.6% in 2010) and in some regional countries (eg, Egypt: 60.3% and 57.6% in 2008, Iran: 77.4% and 57.0% in 2010, and Morocco: 67.4% and 58.6% in 2011) and in some Western countries (eg, Belgium: 70.4 and 69.1% in 2009, France: 78.4% and 72.7% in 2010, UK: 84.0% and 84.0% in 2008, and USA: 76.4% and 70.4% in 2010). 90 The most commonly used modern contraception methods in Lebanon were oral contraceptives (22.2%) followed by intrauterine devices (17.4%) in 2009, surpassing their use in 2004 (7.4% and 8.0%, respectively).86,90

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

A Mendelian randomization analysis indicated that PCOS is likely a risk factor for Bca, mainly estrogen-receptor-positive Bca. 92 A previous systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the risk of Bca increased in women with PCOS, although not significantly, even when excluding those over 54 years from the analysis. 93 The worldwide prevalence of PCOS is estimated to be 8%–21% among women of reproductive age, depending on the definition used for diagnosis. In the MENA region, the estimated ASIRw per 100,000 women for PCOS in 2019 was 77.2 (95% UI: 51.6 to 105.4), reflecting a 33.7% increase (95% UI: 27.7 to 40.3) since 1990. 94 Additionally, the age-standardized point prevalence for PCOS in the same year was 2079.7 (95% UI: 1392.0 to 2812.3), marking a 37.9% rise (95% UI: 31.7 to 45.0) since 1990. 94 Kuwait and Saudi Arabia had the highest age-standardized point prevalence in 2019, while Afghanistan, Yemen, and Sudan had the lowest, with Lebanon falling in the mid-range with a point prevalence of 2357.8 (95% UI: 1607 to 3206.1). 94

Changes in Lifestyle Risk Factors

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding can lower the risk in pre- and post-menopausal Bca.53–55 Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates in parous women in Lebanon were estimated at 10.1% at 6 months in 2004, 12.3% at 6 months in 2012, and 16.5% at 4-6 months in 2016.95–97 According to the World Bank data, the EBF of children under 6 months in Lebanon was 14.8% in 2009, making it less prevalent than in most Arab countries in the MENA region, with the exception of Tunisia (8.5% in 2011) and Yemen (9.7% in 2013). 87

Physical Inactivity

Physical inactivity can lower the risk in pre- and post-menopausal Bca.53–55 A national household survey in Lebanon in 2009 found a significant rate of sedentary female respondents. 85 The rate increased with the age group, from 25.4% in the 18-39 group to 31.8% in the 40-69 group and 47.3% in the 60+ group. 85 According to WHO recommendations in 2008, 40.3% of Lebanese adult women 18-65 fell into the low level of physical activity category (less than 150 minutes of moderate activity per week or equivalent). This prevalence rate increased to 61.3% in 2016-2017.83,84 Among adult females in the MENA region, the highest pooled prevalence measures of sufficient physical activity participation (ie, at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week or equivalent for adults) were found in Jordan (95.5%) and Tunisia (81.8%), and the lowest in Bahrain (1.3%), compared to 59.8% in Lebanon. 98

Excess Body Weight in Adulthood

Excess body weight in adulthood (ie, overweight defined as 25.0 kg/m2 ≤ BMI <30.0 kg/m2 and obesity defined as BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2), particularly before menopause, increases the Bca risk among postmenopausal women.53,55,63,64 A large case-control study in the US have reported that 22.8% of Bca could be avoided if all overweight and obese postmenopausal women attained a BMI below 25. 78 A national 12-year population-based study published in 2009 highlighted an alarming rise in obesity prevalence in the Lebanese population, approaching the rates observed in developed countries such as the US. 99 According to the WHO Global Health Observatory, the prevalence rate (age-standardized estimate) of obesity (BMI ≥30) among female adults in Lebanon in 2010 was 34.3%, slightly higher than the MENA regional average (33.3%), and much higher than the rates in Western countries with high Bca ASIRw. 100 The most recent WHO STEPs surveys in 2016-2017 revealed that 27.5% and 31.4% of Lebanese female adults 18-69 years were obese and overweight, respectively, compared to 26.5% and 32.9% in 2008.83,84

Diabetes Mellitus (DM)

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a suggested postmenopausal Bca risk factor,55,101 is also prevalent and on the rise in Lebanon. Comparing regions worldwide, the MENA region had the highest diabetes age-standardized prevalence in adult females (aged 18 years and older), with rates of 13.4% in 2014 and 12.1% in 2010, while Europe had the lowest rates at 6.7% in 2014 and 6.5% in 2010. 102 Lebanon’s prevalence of DM in adult females (aged 18 and older) is below the average for the MENA region (10.8% vs 13.3% in 2010 and 12.2% vs 14.4% in 2014) according to WHO. 102 However, Lebanon had a higher rate of raised fasting glycemia in adult females (aged 18 years and older) compared to several Western countries, including Belgium, Denmark, France, the UK, the US, and Australia. 102 According to the 2016-2017 WHO STEPS survey, 8.3% of Lebanese adult females (aged 18-69) had DM (ie, raised fasting glycemia ≥126 mg/dL or on anti-diabetic medications), and 2.8% had impaired fasting glycemia (≥110 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL). 83

Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption is associated with increased Bca risk.53–55,63,64 According to the 2016-2017 WHO STEPS survey, the rates of Lebanese females aged 25-64 who consumed alcohol in the past 30 days and 12 months were, respectively, 10.7% and 30.3% in 2009 and 18.9% and 24.7% in 2016-2017. 83 In 2008-2009, only .9% of female alcohol consumers reported daily consumption. 84 According to the World Bank, total alcohol consumption (liters of pure alcohol) per female aged 15 years and older in 2010 was .60 in Lebanon, higher than the other Arab countries in the MENA region (regional average: .22) but lower than Israel (1.42), and much lower than Western countries (5.4 in Belgium, 4.8 in the Netherlands, 5.2 in Denmark, 5.9 in France, 6.1 in Australia, and 4.4 in the US). 89

Smoking

Smoking (active and passive) is likely a risk factor for Bca, even in women who did not drink alcohol.56,58,103,104 Lebanon has one of the highest rates of female tobacco use worldwide (36.5% in 2010) (ranking 7 in 2010 and 5 in 2016). 88 It is by far the highest in the MENA region (regional average: 4.2% in 2010) and higher than the rates reported in Western countries with high Bca ASIRw. 88 Tobacco smoking among Lebanese females aged 15 years and older has increased over the last decade,83–85,88,105 rising from 26% in 2009 to 29% in 2016,83–85 and projected to reach 37.7% in the year 2025. 105 Another research study revealed elevated cigarette pack consumption among adult individuals in Lebanon, amounting to 12.4 packs per person per month. 106 Moreover, numerous residents face the threat of passive smoking due to elevated levels of indoor air pollution resulting from smoking in various public locations in Lebanon. 107 Unlike other Arab countries, smoking in Lebanon is socially acceptable and does not have such a bad social stigma. The regulatory framework for tobacco control in Lebanon is among the least stringent, and tobacco use (hookah pipe or cigarettes) is highly prevalent among teen girls, unlike in other Arab countries (eg, the rates of tobacco use and cigarette smoking among Lebanese females aged 13-15 were reported in 2017 to be 27.9% and 7.2%, respectively). 108 Lebanon became a signatory to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCCT) in 2004 and officially ratified it in 2005. Nevertheless, Lebanon’s Tobacco Control Law 174 took effect at the end of 2011, aiming to accomplish several objectives, including the establishment of 100% smoke-free public places, the prohibition of tobacco advertising, and the implementation of 40% health warnings on cigarette packs. 109 Yet, a Lebanon needs assessment mission conducted by the WHO in April 2016 found that there is considerable interference from the tobacco industry, which has led to the weakened implementation of the Tobacco Control Law. 109 Challenges arise from the tobacco industry’s influence and strong ties between policymakers. Political disruptions hinder Law 174 enforcement, impacting compliance and monitoring. Inadequate inspectors limit coverage across Lebanese regions. High smoking rates persist due to insufficient funding for tobacco control, keeping prevalence among the region’s highest.

Environmental Risk Factors

Evidence indicates that air pollution is a Bca risk factor.11–19 Nitrogen oxides (NOx: NO and NO2), fine particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have all been linked to Bca incidence. A nationwide ecological study in South Korea to investigate the associations between CO, NO2, SO2, O3, PM10, and Bca incidence and mortality rates discovered a significant positive association between the female Bca incidence rate and NO2 and PM10 concentrations. 13 Air pollutants have an impact on Bca via two major physiological pathways. First, carcinogenic air pollution can directly alter genes. Second, air pollution (eg, PM2.5, O3) exhibits endocrine-disrupting properties like xenoestrogens which in turn increase breast density, a known risk factor for Bca. 13

Several studies conducted in Greater Beirut have identified consistently high annual average concentrations of PM10 (averages between 2003 and 2007: 55.1 and 103.8 μg/m³), PM2.5 (averages between 2003 and 2007: 27.6 and 41.0 μg/m³), and NO2 (average in 2005: 67.0 μg/m³), surpassing the WHO 2005 guidelines (20 μg/m³, 10 μg/m³, and 40 μg/m³, respectively) and the WHO 2021 guidelines (15 μg/m³, 5 μg/m³, and 10 μg/m³, respectively).110–114 Lebanon’s air pollution sources emit carbon monoxide (CO) and dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOX: NO and NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), fine particulate matters (mainly PM10 and PM2.5), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOX: NO and NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), fine particulate matter (mainly PM10 and PM2.5), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are all increasing sources of air pollution in Lebanon.112–124 In partnership with university researchers, the Lebanese Ministry of Environment initiated the national air quality monitoring network (AQMN) in 2013, later expanding it in 2017. The data on various air pollutants in Lebanon, reported intermittently by the AQMN over the past decade, indicate that levels of gas pollutants like NO2, particulate matters (PMs) along with their chemical components, and volatile organic carbons consistently exceed the annual average limits recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).115,116 Lebanon experiences some of the most severe air pollution in the MENA region. 123 The predominant sources of petrochemical-based air pollution in residential areas are unregulated private diesel-fueled power generators located in streets and buildings, compounded by heavy traffic in Greater Beirut. Other contributors include small businesses neglecting precautions and uncontrolled power plants. Different incidents, such as the Beirut blast in August 2020, have worsened air pollution in Lebanon. Following the blast, private diesel generators operated nearly continuously to fulfill power demand after the government power grid failure, contributing to environmental health degradation. Regional transportation also influences Lebanon’s ozone levels. 119 In 2018, Lebanon replaced its 1996 air quality law with a new one, Law No. 78 of 2018 on Air Quality Protection. 125 The new law set annual standards for PM2.5, PM10, CO, NOx, O3, and other things based on WHO 2005 guidelines.110,125 However, there has been minimal action to mitigate air pollution, especially considering the current economic challenges confronting Lebanon’s state power company, and the law needs update based on WHO 2021 more stringent guidelines.111,125

Genetic Risk Factors

Researchers identified several Bca-linked genes (Table 3).54,55,126 These genes may account for a small portion of the global variation in Bca incidence.125–127 Inherited gene pathogenic variants or mutations, mostly BRCA1/2 mutations, are thought to be responsible for 5%–10% of all Bca cases and 20%–25% of hereditary Bca cases in the US. 126 Although the median age of Bca diagnosis in the Lebanese population is significantly lower than in Europe and North America, studies in Lebanon suggest that the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in the Lebanese population is lower (5.6 to 15.5%) or similar to those reported in the Western literature.128–131 Based on two cohorts, BRCA1 and 2 mutations were found in 5.6% of the 250 Lebanese women with Bca who met high-risk criteria, 128 and in 15.5% of the 45 high-risk Lebanese women referred for genetic testing. 130 One of these cohorts detected 40% pathogenic mutations in 13 different genes (including 13.3% BRCA1 and 2.2% BRCA2 deleterious mutations). 129 A third cohort of 117 high-risk Lebanese women referred for genetic testing detected 16.2% pathogenic mutations (including 9.4% BRCA1 and .8% BRCA2 deleterious mutations). 130 In this cohort, 13 of the 19 women who had pathogenic mutations were Bca, one was Oca, and five were healthy. 130 A fourth cohort of 281 high-risk Lebanese women referred for genetic testing detected 16.2% pathogenic mutations (including 6.0% BRCA1 and 1.8% BRCA2 deleterious mutations). 131

Limitations of This Study

Our study relied on Bca data published on the MoPH’s official website. Although the NCR’s current data collection is valuable, changes are required to account for missing information on the cases gathered, such as risk factors, mortality and survival rates. Data of precancerous and in-situ cancers remain a gap and should also be reported to the registry. The enhancement of Lebanon’s National Cancer Registry requires funding and increased capacity building, which is difficult because of the current economic crisis. Another limitation of this study is the comparison with the findings of studies conducted in some countries that are not representative of the entire population (eg, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Morocco and Algeria). Furthermore, countries such as Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Iraq reported significant barriers to cancer registration owing to chronic and recurring conflicts and displaced populations. 76

Conclusion

Female Bca rates in Lebanon are among the highest in the world. They are increasing significantly above 50 years of age, and non-significantly between 40 and 49 years of age. To manage and prevent the rise in Bca incidence rates in Lebanon, we must address and investigate potential risk factors such as lifestyle modernization, reproductive changes, and environmental and genetic variables. This study highlights the urgency of addressing the most significant modifiable Bca risk factors, which are growing obesity and air pollution problems in Lebanon, as they have significant implications for Bca risk and overall public health. The development of a comprehensive national Bca control strategy can decrease Bca incidence. The findings of this research support the current national screening recommendation, which is to initiate Bca screening at the age of 40. However, a cost-effectiveness analysis of this screening is still lacking. Furthermore, the Lebanese NCR, which has been collecting excellent data since 2003-2004, could benefit from a more comprehensive database that include precancerous and in-situ cases, location of cancer in the breasts, staging TNM, hormonal receptors, therapy provided, and outcome, namely mortality/survival rates at 1, 2, and 5 years.

Appendix.

Abbreviation Description

- APC

Annual percent change

- AAPC

Average annual percent change

- ASIRw

Age-standardized incidence adjusted to the world population

- Bca

Breast cancer

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI5Plus

Cancer incidence in five continents time trends

- CI5XI

Cancer incidence in five continents volume XI

- EMR

Eastern Mediterranean region

- HDI

Human development index

- HRT

Hormone replacement therapy

- IARC

International agency for research on cancer

- ICD10

International classification of diseases, tenth revision

- JRP

Joinpoint regression program

- MENA

Middle East and North Africa

- MoPH

Ministry of public health

- NCR

National cancer registry

- Oca

Invasive ovary cancer

- STI

Sexually transmitted infection

- Uca

Invasive corpus uteri cancer

- UIs

Uncertainty intervals

- UK

United Kingdom

- US

United States of America

- USD

United States dollars

- USPSTF

United States preventive services taskforce

- WHO

World health organization

- WHO STEPs

WHO STEPwise approach for non-communicable diseases risk factor surveillance

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval

Ethical approval is not applicable to this article. There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable. The National Cancer Registry Data used in the manuscript is published on the website of the Lebanese ministry of public health (https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/2/193/esu).

ORCID iDs

Najla A. Lakkis https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8967-5789

Hanane G. Issa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6650-3928

Mona H. Osman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6364-6541

Data Availability Statement

Data is available for the public on the website of the Ministry of Public Health, Republic of Lebanon: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/2/193/esu.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F. et al. GLOBOCAN 2020. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today. Accessed Feb 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893-2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359-E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Global Health Estimates 2016: Disease Burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2016. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/esti-mates/en/index1.html. Accessed July 09, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Development Programme . Human Development Reports. Human Development Indices and Indicators. 2018 Statistical Update. https://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-indices-indicators-2018-statistical-update. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinton LA, Gaudet MM, Gierach GL. Breast cancer. In: Thun M, Linet MS, Cerhan JR, Haiman CA, Schottenfeld D, eds. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2018:861-888. [Google Scholar]

- 9.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223-1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metcalfe KA, Poll A, Royer R. et al. Screening for founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in unselected Jewish women. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):387-391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang J, Bae H, Choi S, Yi H, Ko B, Kim N. Impact of air pollution on breast cancer incidence and mortality: a nationwide analysis in South Korea. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62200-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White AJ, Bradshaw PT, Hamra GB. Air pollution and breast cancer: a review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5(2):92-100. doi: 10.1007/s40471-018-0143-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen ZJ, Stafoggia M, Weinmayr G. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and incidence of postmenopausal breast cancer in 15 European cohorts within the ESCAPE Project. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(10):107005. doi: 10.1289/EHP1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei Y, Davis J, Bina WF. Ambient air pollution is associated with the increased incidence of breast cancer in US. Int J Environ Health Res. 2012;22(1):12-21. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2011.588321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White AJ, Fisher JA, Sweeney MR. et al. Ambient fine particulate matter and breast cancer incidence in a large prospective US cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;116:53-60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djad170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Society for Medical Oncology Air Pollution and Breast Cancer Risk - A Link that Calls for Political Action. Date: 17 Oct 2023. https://www.esmo.org/newsroom/press-releases/air-pollution-and-breast-cancer-risk-a-link-that-calls-for-political-action [Accessed November 20, 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fervers B, Duboeuf M, Amadou A. et al. 238MO Long-term residential and workplace exposure to air pollution and breast cancer risk: a case-control study nested in the French E3N cohort from 1990 to 2011. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(Supplement 2):S278. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.09.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amadou A, Praud D, Coudon T. et al. Long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide air pollution and breast cancer risk: a nested case-control within the French E3N cohort study. Environ Pollut. 2023;317:120719. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotake R, Yamauchi H, Kimura T, Tsunoda H, Lee M. An association between mammographic breast density and fine particulate matter among postmenopausal women. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(10):25953-25958. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-23529-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank Group . The World Bank. Indicators. Mortality Rate, Infant (Per 1,000 Live Births). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN. Accessed February 24, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Bank Group . The World Bank. Indicators. Maternal Mortality Ratio (Modeled Estimate, Per 100,000 Live Births). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT. Accessed February 24, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Bank Group . The World Bank. Indicators. Fertility Rate, Total (Births Per Woman). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN. Accessed February 24, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Bank Group . The World Bank. Indicators. Life Expectancy at Birth, Female (Years). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.FE.IN?view=chart. Accessed February 24, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adib SM, El Saghir NS, Ammar W. Guidelines for breast cancer screening in Lebanon public health communication. J Med Liban. 2009;57(2):72-74. PMID: 19623881 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakkis NA, Adib SM, Osman MH, Musharafieh UM, Hamadeh GN. Breast cancer in Lebanon: incidence and comparison to regional and Western countries. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34(3):221. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fares MY, Salhab HA, Khachfe HH, Khachfe HM. Breast cancer epidemiology among Lebanese women: an 11-year analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(8):463. doi: 10.3390/medicina55080463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zahedi R, Molavi Vardanjani H, Baneshi MR. et al. Incidence trend of breast Cancer in women of eastern Mediterranean region countries from 1998 to 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Wom Health. 2020;20(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00903-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safiri S, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA. et al. Burden of female breast cancer in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990-2019. Arch Publ Health. 2022;80(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s13690-022-00918-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siu AL. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279-296. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estrada SS. Review of the New American cancer society guidelines for breast cancer screening for women at average risk. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2016;7(5):563-566. PMID: 29282431 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care . Breast Cancer Update. Recommendations on Screening for Breast Cancer in Women 40-74 Years of Age Who Are Not at Increased Risk; 2018. https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/breast-cancer-update/. Accessed April 19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schünemann HJ, Lerda D, Quinn C. et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis: a synopsis of the European breast guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(1):46-56. doi: 10.7326/M19-2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duffy SW, Vulkan D, Cuckle H. et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(9):1165-1172. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30398-3. https://www.thelancet.com/article/S1470-2045(20)30398-3/fulltext [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Draft Recommendation Statement; 2023. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/breast-cancer-screening-adults#bcei-recommendation-title-area. Accessed November 11, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adib S, Daniel J. Cancer in Lebanon 2004 with an Update of Cancer 2003. Beirut, Lebanon: Ministry of Public Health, National Cancer Registry; 2008. https://www.moph.gov.lb/DynamicPages/download_file/571. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Cancer Registry . Lebanon. Republic of Lebanon: Ministry of Public Health; 2020. https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/2/7164/national-cancer-registry#/en/Pages/2/193/esu. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bray F, Ferlay J. Age standardization (chapter 7). In: Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L. et al. , eds. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. XI (electronic version). Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2017. https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5-XI/Pages/Chapter7.aspx. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 38.United States Cancer Statistics (USCS) . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Website. Updated August 20, 2014 https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/technical_notes/stat_methods/rates.htm. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joinpoint Help System 4.7.0.0 (Online)- Surveillance Research Program. USA: National Cancer Institute (NCI), Division of cancer control and population sciences. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/help/joinpoint/setting-parameters/method-and-parameters-tab. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dyba T, Hakulinen T. Comparison of different approaches to incidence prediction based on simple interpolation techniques. Stat Med. 2000;19(13):1741-1752. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñ M. Annex A. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Data: Sources and Methods by Country. GLOBOCAN 2020 annexes. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/methods/GLOBOCAN2020_annexes.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Statistical Bulletins. Lebanon: Ministry of Public Health, Republic of Lebanon; 2019. https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/8/327/statistical-bulletins. Accessed November 29, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Bray F. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Time Trends (CI5plus): IARC CancerBase No. 9 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2018. https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5plus/Pages/table4_sel.aspx. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bray F, Colombet M, Mery L. et al. , editors. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. XI [electronic version]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2017. https://ci5.iarc.fr/CI5-XI/Pages/registry_summary.aspx. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Cancer Registry Program of Egypt (NCRPE) . https://mcit.gov.eg/en/Publication/Publication_Summary/554. Accessed February 23, 2021.

- 46.Registre des Cancers de la Région du Grand Casablanca pour la période 2008 - 2012. Edition 2016. https://www.contrelecancer.ma/site_media/uploaded_files/RCRGC.pdf. Accessed March 03, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 47.The NORDCAN Project. https://www-dep.iarc.fr/NORDCAN/english/frame.asp. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cancer Today . International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); World Health Organization (WHO). Data & Methods. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data-sources-methods. Accessed November 13, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 49.El Saghir NS, Khalil MK, Eid T. et al. Trends in epidemiology and management of breast cancer in developing Arab countries: a literature and registry analysis. Int J Surg. 2007;5(4):225-233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El Saghir NS, Seoud M, Khalil MK. et al. Effects of young age at presentation on survival in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarabeia J, Baron-Epel O, Barchana M. et al. A comparison of trends in incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer, incidence to mortality ratio and stage at diagnosis between Arab and Jewish women in Israel, 1979-2002. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2007;16(1):36-42. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000228407.91223.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nissan A, Spira RM, Hamburger T. et al. Clinical profile of breast cancer in Arab and Jewish women in the Jerusalem area. Am J Surg. 2004;188(1):62-67. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research . Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. dietandcancerreport.org. Accessed February 23, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies-an updated review. Cancers. 2021;13(17):4287. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press); 2019;11:151-164. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S176070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:287-299. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S197604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lortet-Tieulent J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Jemal A. International patterns and trends in endometrial cancer incidence, 1978-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(4):354-361. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raglan O, Kalliala I, Markozannes G. et al. Risk factors for endometrial cancer: an umbrella review of the literature. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(7):1719-1730. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piombino C, Cortesi L, Lambertini M, Punie K, Grandi G, Toss A. Secondary prevention in hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer syndromes other than BRCA. JAMA Oncol. 2020;2020:6384190. doi: 10.1155/2020/6384190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer . Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1159-1168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31709-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Youlden DR, Cramb SM, Dunn NA, Muller JM, Pyke CM, Baade PD. The descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: an international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:237-248. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69-90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer in women: burden and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(4):444-457. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.American Cancer Society . Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 3rd ed. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015:37-51. Special Section: Female Breast Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM. et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. The lancet. 2011;378:1461-1484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61351-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haddad FG, Kourie HR, Adib SM. Trends in mammography utilization for breast cancer screening in a Middle-Eastern country: Lebanon 2005-2013. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39(6):819-824. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Obermeyer CM, Ghorayeb F, Reynolds R. Symptom reporting around the menopause in Beirut, Lebanon. Maturitas. 1999;33(3):249-258. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hou N, Huo D. A trend analysis of breast cancer incidence rates in the United States from 2000 to 2009 shows a recent increase. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(2):633-641. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2434-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pisano ED, Hendrick RE, Yaffe MJ. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of digital versus film mammography: exploratory analysis of selected population subgroups in DMIST. Radiology. 2008;246(2):376-383. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461070200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E. et al. Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]