Abstract

Innovation in material design to regulate cell behavior and function is one of the primary tasks in materials science. Integrins, a family of cell surface-adhesion receptors that mechanically connect the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the intracellular cytoskeleton, have long served as primary targets for the design of biomaterials because their activity is not only critical to a wide range of cell and tissue functions but also subject to very tight and complex regulations from the outside environment. To review the recent progress of material innovations targeting the spatial distribution of integrins, we first introduce the interaction mechanisms between cells and the ECM by highlighting integrin-based cell adhesions, describing how integrins respond to environmental stimuli, including variations in ligand presentation, mechanical cues, and topographical variations. Then, we overview the current development of soft materials in guiding cell behaviors and functions via spatial regulation of integrins. Finally, we discuss the current limitations of these technologies and the advances that may be achieved in the future. Undoubtedly, synthetic soft materials that mediate the spatial distribution of integrins play an important role in biomaterial innovations for advancing biomedical applications and addressing fundamental biological questions.

I. INTRODUCTION

Biomaterial innovation and engineering aiming to control cell behavior and function is an actively growing field attracting investigations of both fundamental biological questions and biotechnological applications. Nevertheless, a major challenge in developing biomaterials has arisen from the incomplete understanding of how environmental cues regulate a cell. Credit to scientists' continued efforts, it was revealed that the cellular response to environmental cues goes far beyond the chemical sensing of ECM ligands and encompasses a wide range of physical cues that are generated at, or acted on at, the adhesive interface between cells and the surrounding ECM.1–3 Thereafter, modulating the mechanics and surface topography of soft materials has become a feasible and practical approach with promising potentials in the development of biomaterials to regulate cell behaviors achieving various functions.4–6

Integrins are the major family of cell receptors responsible for cell adhesion,7,8 and have long served as the primary targets for the design of biomaterials in order to facilitate cell attachments. Cumulative investigations on integrins laid the foundations for understanding their remarkable complexity and mighty functions, leading to the advancement of biomaterials for the control of cell behaviors and the promotion of cellular functions.9–12 Meanwhile, advances in fabrication techniques also enable the engineering of materials with great versatility and highly controlled spatial geometries.12,13 Recent studies on highly engineered surfaces of biomaterials have indicated that precision control of ligand presentation is a powerful approach to regulate cell–matrix interaction, attracting increasing attention in the field of both material design and fundamental biology research.14–20 In this review, we will first discuss how environmental stimuli are detected and responded to by the cells via integrins, which will elucidate the cell–biomaterial interactions and provide insightful information for biomaterials design and engineering. After briefly summarizing the development of integrin-targeted biomaterials, we will focus on innovations in the design of biomaterials to mediate the spatial distribution of integrins.

II. ENVIRONMENTAL SENSING THROUGH INTEGRINS

Cell–matrix adhesion is a critical process by which cells communicate with their surrounding environment mediated by specialized multi-protein complexes such as nascent adhesions (NAs), focal adhesions (FAs), fibrillar adhesions, and podosomes.21 The ECM is a mesh network composed of cell-adhesive molecules to ensure cell cohesion, as well as signaling molecules that direct cell morphology and behavior.22 Integrins are the major family of cell receptors, consisting of alpha and beta subunits, which regulate cell adhesion dynamically in response to the surroundings, especially the ECM.23 The 24 heterodimeric members that have been discovered by far are classified into four subfamilies including the collagen-binding integrins (α1β1, α2β1, α10β1, and α11β1);24 the laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1, α6β4, and α7β1);25 the RGD-binding integrins (αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ1, αvβ8, α5β1, αIIbβ3, and α8β1) and leukocyte integrins26 that bind to intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAMs) (β2 integrins); polysaccharides (αMβ2 and αXβ2); and plasma proteins (αDβ2). In regard to the critical constituents of ECM glycoproteins, besides laminin and collagen-binding integrins, fibronectin-binding integrins (α5β1, and αvβ3)27 are the main targets for biomaterial design to regulate cell–matrix adhesion. In addition to anchoring cells to the ECM, integrins recruit adhesion complexes and stimulate actin polymerization to comprise the cellular machinery that recognizes not only the biochemical stimuli but also the physical and topographical properties of ECM.8 Such environmental sensing mechanisms, based upon the well-oiled crosstalk between the dynamics of integrin-based adhesion complex and the forces generated by the associated cytoskeleton networks such as actin polymerization and actomyosin contraction, as it is presently understood, are described below.28,29

A. The actin-integrin linkage and integrin activation in mechanotransduction

In response to extracellular or intracellular stimuli initiating mechanotransduction, integrins recruit multi-protein complexes that form mechanical links between actin bundles in the cytosol and the ECM.30,31 The formation and function of such links can be divided into a few defined steps, including activation, clustering, growth, maturation, and disassembly, which are regulated by the ligand affinity to integrins temporally and spatially,32 while mediated by an array of co-receptors, transmembrane proteins, and crosstalk between distinct integrin heterodimers.33 The mediation effects of co-receptors leads to diversified integrin functions. Structural and functional studies indicate that integrins exist in different states with diverse affinity to ligands.34 For instance, the inactive integrin has a bent conformation with its transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains closely connected.34 In contrast, the inactive integrin can undergo rapid and reversible conformational switch while receiving activation signals, including the extension of extracellular domains and the separation of cytoplasmic leg domains (Fig. 1).34

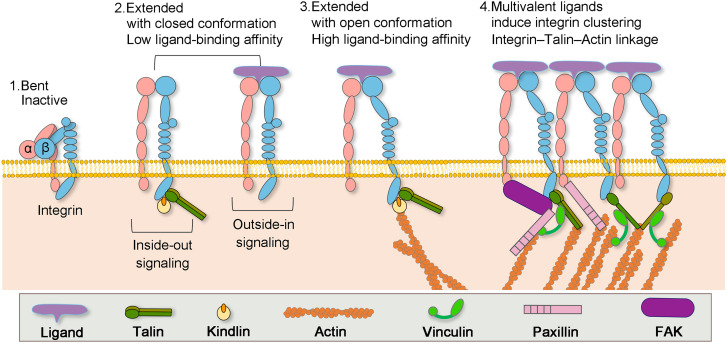

FIG. 1.

Formation of actin–integrin linkage and integrin activation. Step 1: low-affinity integrin has an inactive, bent conformation. Step 2: inside-out integrin activation by cytoplasmic proteins or outside-in integrin activation via ECM ligands leads to complete extension of the extracellular domains. Step 3: the open, high-affinity activated integrin has the cytoplasmic leg domains separated and links to actin cytoskeleton via talin. Step 4: multivalent ligand binding induces clustering of integrins.

Integrin activation can be achieved via two approaches: the outside-in approach and the inside-out approach. Ligand binding is by far the most feasible extracellular approach, while intracellular activation is realized through the binding of adaptor proteins to the cytoplasmic tails of integrin (Fig. 1).32 Specifically, single ligand binding to the external domain of integrin will induce conformational changes in its cytoplasmic domains to recruit adaptor and signaling proteins.35 In contrast, multivalent ligand binding may lead to clustering of integrins, enhancing the adhesion strength and activating outside-in signaling.17 On the other hand, it has been reported that once the recruitment of talin or kindlin from the cytosol to the integrin cytoplasmic domain was fostered by signals initiated from other receptors, vinculin and F-actin were recruited to stabilize talin–integrin binding and promote integrin activation from inside.32 These two mechanisms are conceptually separated; however, they are mutually cooperative, and combined manipulation of both mechanisms will promote the conformational transition of integrins from a closed, low-affinity structure to an open, high-affinity state. The critical step in forming the actin–integrin linkage is the binding of talin to the integrin cytoplasmic tail.36 Following that, integrins are indirectly connected to the actin cytoskeleton through adaptor proteins, including α-actinin, vinculin, FAK, and VASP.36 Remarkably, the recruiting of vinculin to talin triggers the clustering of activated integrin and strengthens the integrin–actin linkage through the connection between vinculin tail and actin.37

B. The spatial distribution of integrins and adhesion dynamics

The temporal and spatial distribution of integrins together with the interactions between integrins and actin cytoskeleton control the formation and dynamics of integrin-based adhesions.38 There are four types of adhesions, namely, nascent adhesions (NAs), focal adhesions (FAs), fibrillar adhesions, and sliding adhesions, as presented in Fig. 2. NAs are the smallest integrin-adhesion complexes that are detectable under a microscope.39 They appear in small dots with a diameter around 250 nm forming underneath the lamellipodia—the thin-sheet protrusion at the leading edge of the cell generated by actin polymerization and filled with a highly dynamic branched network of actin filaments.40 Although the composition inside NAs is not well-characterized yet, besides integrins, many well-studied adhesion molecules, including adaptor proteins such as talin and vinculin and signaling molecules such as FAK and paxillin, appear to enter NAs.40 Actin polymerization is also required for the formation of NAs. Treating cells with cytochalasin D, which inhibits actin polymerization and induces depolymerization of actin filaments, always leads to complete disintegration of NAs.41 In contrast, the inhibition of myosin II, a critical component of the actin–myosin system, barely disrupts the formation or persistence of NAs.41

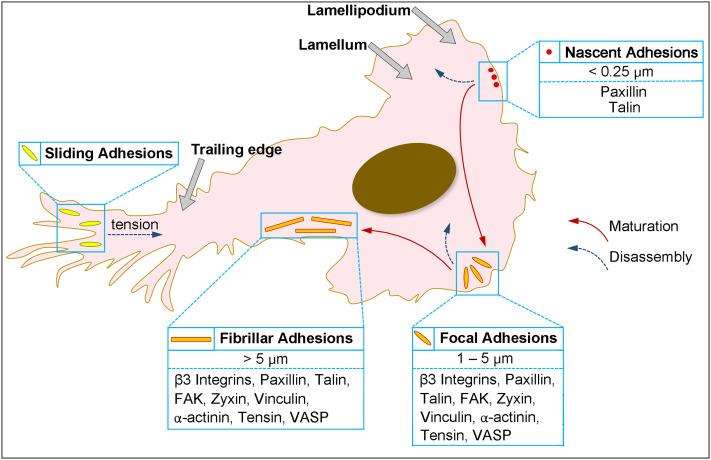

FIG. 2.

Dynamics of integrin-based adhesion: typical localizations and hallmarks of nascent adhesions, focal adhesions, fibrillar adhesions, and sliding adhesions. The hierarchy of their maturation (red arrows) or disassembly (blue arrows).

During cell spreading or migration, the lamellipodia continue to move forward, whereas NAs remain immobile; they either disappear after a lifespan of less than 1 min or grow into long-lived micrometer-sized FAs at the boundary between the lamellipodium and the lamella.38 During this transition, differences in protein composition, phosphorylation, and dynamics have been reported in various studies.42–44 For instance, zyxin was recruited into FAs during the maturation process but did not localize to the NAs (Fig. 2).44 Matured FAs are highly integrated with the bulk of the actin cytoskeleton. They are consistently found at the end of stress fibers, which are actin bundles containing filamentous actin and myosin II.45 Myosin II activity is required for FA maturation and responsible for the contractile nature of stress fibers.44 The continuous contraction force generated by the stress fibers is found to then be transmitted to the ECM through FAs.46 The matured FAs typically disassemble within 20 minutes or evolve further into a very large (>5 μm) and elongated structure located toward the center of a cell, termed fibrillar adhesions.38 Fibrillar adhesions associate with large stable actomyosin bundles with a lifespan of several hours and participate actively in ECM remodeling.47 Most of the components present in NAs and FAs are also involved in fibrillar adhesions; however, the high level of tensin (one type of actin-binding tyrosine-phosphorylated protein) and low level of phosphotyrosine-containing signaling proteins make the fibrillar adhesions distinguishable with NAs and FAs (Fig. 2).47

Adhesion complexes in both central regions and near the rear of cells can undergo disassembly to promote cell spreading and migration.38 Disassembly of adhesions is primarily mediated through tyrosine phosphorylation events and changes in cytoskeletal tension.48 Moreover, several other mechanisms also contribute to this process, including microtubule targeting, proteolytic activation, and actomyosin-based contraction force.48–51 Turnover of NAs located at the leading edge is dependent on the forces generated by actin depolymerization and reorganization.41 By contract, microtubule- and FAK-dynamics-mediated endocytic mechanisms play essential roles in the disassembly of central adhesions.48 For adhesion disassembly during retraction of the trailing edge, the adhesions at the rear usually slide inwards as the trailing edge moves forward.52 Large protein aggregates are known to disassociate from the adhesion site in a Rho/myosin II-dependent manner during “sliding,” leaving integrin trails on the substrate (Fig. 2).52

The adhesion dynamics, including the transitions between adhesions, involved with diverse range of changes in the morphology, molecular constituents, and locations, regulate cell–matrix interactions and correlated cellular functions. For example, it's revealed that fibrillar adhesions are enriched in α5β1 integrin that is associated with fibronectin, while the focal adhesions contain relatively high level of integrin αvβ3. Therefore, covalent immobilization of substrate-fibronectin blocks the formation of fibrillar adhesions. It was also demonstrated that the formation of fibrillar adhesions is affected by the rigidity or deformability of the ECM too. Therefore, regulation of a specific integrin isoform distribution may lead to the control of adhesion dynamics, while the regulation of adhesion formation may result into a control of integrin distribution. And both ways guide the materials design to control cell behavior and cellular functions.

III. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL CUES REGULATE SPACIAL DISTRIBUTION OF INTEGRINS

Studies combining state-of-the-art fabrication technology, surface chemistry, and cell biology imply that cells respond differentially to various parameters of the artificial ECM, including the chemical nature of the ligands presenting on the surface, the precise spatial and temporal distribution of the ligands, as well as the physical properties of ECM scaffold, such as its stiffness, rigidity, and topography.2,3,7,11,12,16

A. Nanospacing of bioactive ligands

One common strategy for generating cell adhesive biomaterials is to functionalize nonfouling materials such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) with integrin-binding molecules.12 Regularly, peptide or protein ligands are covalently tethered onto nonfouling biomaterials with uniform distribution.53 However, such a presentation of monovalent integrin ligands solely promotes integrin occupancy but not integrin aggregation, which is not sufficient to trigger a full cell adhesion response.17 It was claimed that regardless of the quantitative control of the “global” distribution of ligands on the surface of biomaterials, the concentration of ligands over the length scale of sub-cellular FAs, termed the “local” ligand density, is critical to trigger a full cell adhesion response.17 For example, αvβ3 integrin-mediated cell adhesion is crucially influenced by how far ligands are spaced apart. “Local” ligand density is commonly achieved through clustered ligands on the surface of biomaterials, in which the ligands are grouped into small, isolated areas.54 Biomaterials with clustered integrin ligands are proved to initiate both the activation and aggregation of integrins, trigger the formation of NAs and FAs, and promote cell proliferation as well as mobility[Fig. 3(a)].14

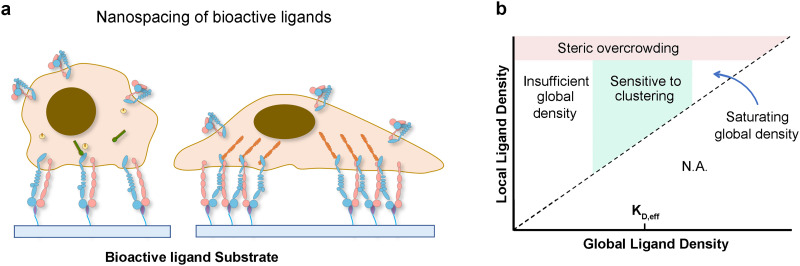

FIG. 3.

Chemical perturbations in the ECM regulate cell function via integrin: When cells are adherent to biomaterials presenting monovalent ligands, focal adhesion formation and cell spreading are impaired; however, culturing cells on surfaces functionalized with multivalent ligands promotes the formation of adhesion complexes and cell spreading (a). Phase diagram of integrin signaling in various global and local ligand density regimes (b).

Nevertheless, nonlinear responses to increasing local ligand density are also observed [Fig. 3(b)]. Several studies have reported that overcrowding of integrin ligand cannot effectively trigger a full cell adhesion response.55 To elucidate the underlying principles, scientists used protein-engineered fabrics for their exploration and proposed two mechanisms: first, clustering of ligands enhances integrin-dependent signals when the global ligand density is near the ligand's effective dissociation constant (KD,eff); second, clustering of ligands enhances integrin activation when the local ligand density is less than an overcrowding threshold. For RGD ligand, at a local density of 122 000 μm−2, the focal adhesion number and focal adhesion kinase expression are significantly reduced. Following that, the cellular responses, including cell migration and division, are suppressed confirming the significant impact of ligand overcrowding on integrin signaling.55 Such general principles of cellular responses to ligand clustering at the cell–matrix interface provide guidance for the development of future generations of biomaterials.

B. Mechanical cues

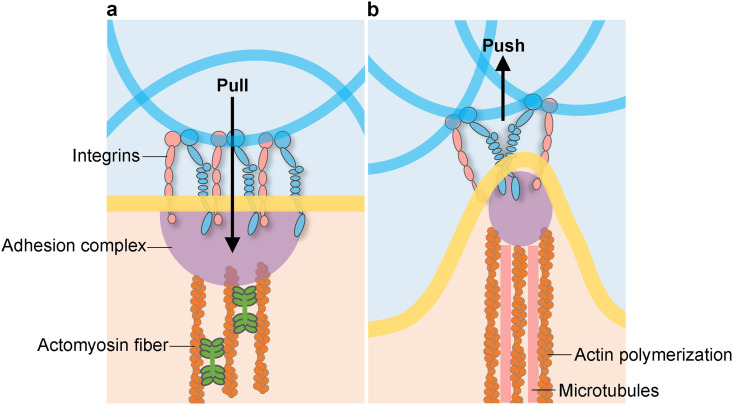

The recognition of directing cell morphology and function via the control of ECM's physical properties has a long history in cell biology and biomaterials science.56 Such an approach has been identified through many experimental studies as well as computational modeling. As the cells adhere to the ECM scaffold via integrin-mediated adhesions, they pull on the scaffold through their actomyosin contraction fibers, sense the mechanical stimuli, and actively respond to this force through their cytoskeleton (Fig. 4).57 Such mechanical responses inspired material scientists to manufacture bio-scaffolds mimicking the mechanical conditions of natural ECM.57 By culturing cells on or within the bio-scaffold, scientists observe and study cell behaviors and functions, such as morphology, migration, proliferation, as well as gene expression. Over the past two decades, substantial research has established that the ECM elasticity, or stiffness, affects fundamental cellular processes. However, ECMs are not linearly elastic materials. They exhibit far more complex mechanical behaviors, including viscoelasticity. Recent studies have revealed that ECM viscoelasticity not only affects the same fundamental cellular processes as elasticity but also promotes behaviors that are not promoted by elasticity.58

FIG. 4.

Mechanical interactions between cells and the ECM. Cells interact with the ECM mechanically, for example, by pulling induced by actomyosin-based contractility via integrin adhesions on the ECM (a), and by pushing through actin polymerization and microtubules (b), resulting in mechanotransduction affecting cell behaviors.

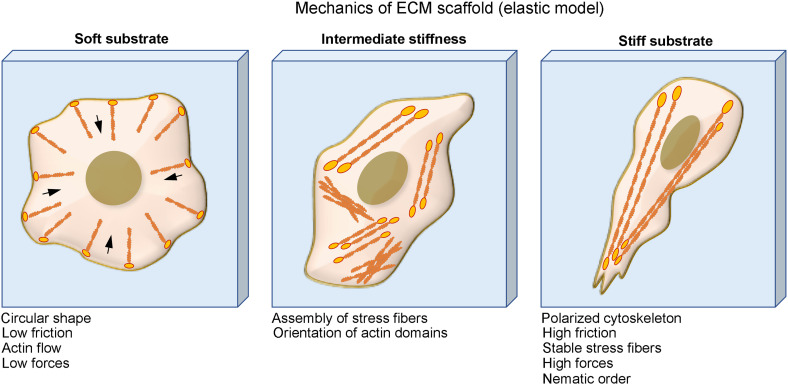

Regarding the mechanical property of cell culture substrate, earlier studies have demonstrated that cells on soft substrates have less-spreading morphologies, lower friction, lower traction force, and less-organized cytoskeleton. The cell spreading, cytoskeleton organization, as well as the stability of adhesions are promoted upon increasing the substrate stiffness (Fig. 5).59 Meanwhile, the ECM stiffness might also direct cell functions such as anchorage-dependent cell growth and viability.60 For example, fibroblast cultured on soft substrates undergoes less proliferation and more apoptosis compared to stiff substrates.61 In addition to that, cell migration, which is central to many biological processes, including wound healing and cancer progression, is also affected by substrate stiffness.62 Many cell types may achieve maximum migration speed at certain stiffness optimum.63 This prediction has been verified experimentally by comparing cell traction and F-actin retrograde. Furthermore, stiffness can also direct lineage commitment and the differentiation state of stem cells.64–66 For example, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) express more chondrogenic and adipogenic markers on the soft substrate but express more smooth muscle cell markers on stiffer substrates.65 Therefore, scientists later expanded the concept of stiffness optimum to the maximum promotion of various cellular responses. For example, neurons preferentially branch on soft substrates while glial cells prefer to grow on relatively stiffer substrates.67,68 Myocytes, although they require substrates of about 12 kPa for optimal striation, spread almost equally in a wide range of stiffness.69

FIG. 5.

Physical perturbations in the ECM regulate cell function via integrin: Cells on soft substrates have circular shape, low friction, and actin flow. Cells form stress fiber and more organized cytoskeleton when culturing on substrate with intermediate stiffness and cells on stiff substrate have polarized cytoskeleton, high friction, stable stress fibers, and high traction force.

Cell–matrix interactions are dynamic processes that span a range of forces and a range of timescales. ECMs exhibit complex mechanical properties, including viscoelasticity, which is a time-dependent response. An emerging body of evidence has demonstrated that complex mechanical characteristics affect cells. Not only has viscoelasticity been found to be a near-universal characteristic of ECMs, but also nonlinear elasticity is observed in cytoskeletal filament networks. Therefore, the previous understanding of mechanotransduction based on a purely elastic model is not adequate for an in-depth study. Viscoelasticity is applied to elucidate mechanotransduction of ECM on cells. The effect of substrate viscoelasticity on cells has been demonstrated via two-dimensional (2D) culture studies. It was found that increased loss, or creep, in the substrates promoted MSC spreading, focal adhesion formation, proliferation, and differentiation toward adipogenic, osteogenic, and smooth muscle cell lineages.70 With higher loss and creep, increases in motility and lamellipodial protrusions were observed.71 Via fibroblast cell culture, it was demonstrated that an increased loss modulus, or faster stress relaxation, diminished fibroblast stiffness and cell spreading area. By comparing elastic substrate and viscoelastic substrate, scientists found that although cells were unable to spread on soft elastic gels, they were able to spread on soft viscoelastic gels.72 The effects of matrix viscoelasticity on cells are explored in three-dimensional culture too. It was demonstrated that increased stress relaxation, enhanced creep, or higher loss modulus promotes spreading of adherent cells. Faster stress relaxation and increased loss also promote cell cycle progression and completion of mitosis in single cancer cells, fibroblasts, and osteogenic differentiation of MSCs.73–75 Although the understanding of mechanotransduction in viscoelastic matrix is still limited, these findings have been highlighted as important parameters for the design of biomaterials with potential applications in regenerative medicine.

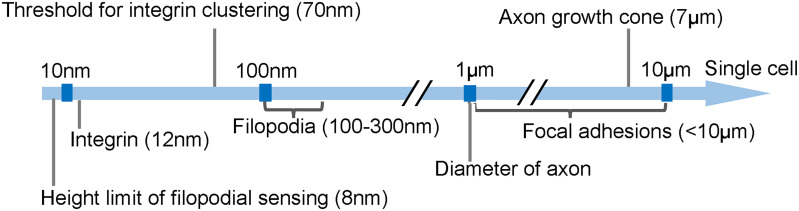

C. Nano/micrometric topographical cues

In addition to mechanical conditions, the surrounding ECMs are consisted of micro- and nano-scale topographical patterns, which are also considered as important factors that can influence cell behaviors.76 Before proceeding to discussing how topography affects cell behaviors at the cellular level, it would also be essential to understand the natural topographic structures, such as corneal epithelium basement membrane,77 heart myocardium,78 blood vessel, and native collagen I fiber,79 are the mimicking objects of engineered topographical substrates. Later, scientists made a breakthrough finding demonstrating that topographical factors including size, shape, and geometric arrangement could exert strong effects on cell behaviors, such as adhesion, migration, alignment, and differentiation.80–85 Regardless of the uncertainty of cell response to topography, which is highly dependent on cell type, the topographical size exhibited crucial influence on all types of cells. Several studies regarding the correlation between topographical size and cellular response indicate that microtopography (feature size larger than 10 μm) mainly exerts effects on whole cell morphology, while nanotopography is particularly involved in subcellular sensing mechanisms (Fig. 6). An optimal size of topographical features in both scales can induce the strongest cell response.67,86,87

FIG. 6.

Correlation between size of substratum topography and cellular sensing organelles.

Early studies on fibroblast cells, osteoblast cells,88 and neuron cells have shown that at the nanoscale, surface roughness, height, and lateral spacing all have a bearing on cell adhesion;87 while, at the microscale, cell adhesion is sensitive to the diameter, height, and pitch of microtopographical features. Following adhesion on the substrate, the conformation of cells is influenced by the geometry, arrangement, and dimensions of topography.89 For example, cells showed a spreading morphology with isotropic fibrous F-actin networks on unpatterned substrates but aligned to the substrate axis on anisotropic substrates. Both nanoscale and microscale topographical features with dimensions ranging from lower than 100 nm to a few hundred micrometers all showed sensitivity to cell alignment.90 Compared with changes in individual dimensions, varying multi-dimension topographical features can enhance cell alignment more profoundly. For neurons that are morphologically distinct from other cell types, topographical features stimulate neuronal guidance through contact guidance, and neurons can distinguish nanotopography. For example, the diameter and arrangement of anisotropic electrospun nanofiber, and the height, radius, and spacing of isotropic structures such as nanopillars strongly affect neural cell morphology, differentiation,91,92 neurite length, and neurite alignment.93

Because the ECMs and tissues in nature have topographical patterns ranging from nano- to micrometer scale, the synergistic effect of hierarchical topographical features on cell behaviors is also studied.94 From cell adhesion and alignment to differentiation and subtype fate determination, the synergistic nature of hierarchical structures promotes cell response in various ways. For example, micrograting substrates with nanofibrous matrices deposited on top enhance endothelial cell elongation;95 incorporation of nanomodules to micropits promotes osteoblast adhesion, differentiation, and proliferation; and the combination of micrograting patterns and nanopore patterns promotes cell differentiation.96,97 Micropatterns of wells connected by grooves of micrometer width on nanofiber mats guide neurite growth to greater lengths, exhibiting a positive effect on cell attachment and confinement. Although no universal rules are applicable as guidance for material design with hierarchical topographical features, mimicking the fine structures in natural environment by far works the best.

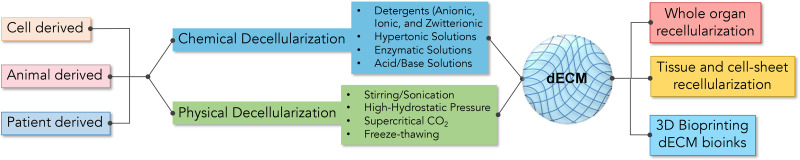

IV. BIOMATERIALS MEDIATE THE SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF INTEGRINS

Targeting integrin has long served as a focus in the development of biomaterials since the presentation of a cell adherent interface is the initiation of cell manipulation from outside-in via biomaterials, and integrins are essential to adhesions. The first generation of cell adherent materials is decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) (Fig. 7).22 By far, cell-derived ECMs have been used for the generation of blood vessels and heart valve constructs,98 and tissue-derived matrices were fabricated as surgical mesh or patch graft in clinical use.99 In order not to trigger any adverse inflammatory responses, an efficient decellularization is essential and critical to the application of dECMs in clinical applications.98 However, a thorough decellularization process inevitably disrupts the biochemical and physical properties of natural ECMs, including their thickness, stiffness, ligand distribution, and 3D configuration,100 in a substantial way.101 In addition to that, a mechanistic understanding of how cell or tissue-derived matrices affect the growth and function of cultured cells is still limited. At present, cutting-edge techniques such as proteomics have been applied to map the repertoire of the components of dECM, which will not only offer insights into dECM but also guide in the design of synthetic ECMs.

FIG. 7.

Fabrication of decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM): The ECM derived from cell, animal, or patient via chemical or physical decellularization can be used for whole organ recellularization, tissue and cell culture, and 3D bioprinting.

A. Biomaterials with tunable mechanical properties—Regulate integrin-based adhesions

It has been demonstrated that the mechanics is an important physical factor of biomaterials regardless of how adhesive ligands are presented. Therefore, after summing up the substantial studies on the influence of mechanical properties of ECMs, such as elasticity and viscoelasticity, on integrin-mediated cell adhesion, we then overviewed the production of bioengineered materials with tunable elasticity102 or viscoelasticity that were mainly polymers. The materials can be attributed to natural polymers, synthetic polymers, and hybrid polymers by combining both natural and synthetic polymers.

1. Biomaterials with tunable elasticity

The fibrous component of ECM mainly consists of collagen and elastin. Collagen fibers serve to provide strength and structural support while elastin provides elasticity. To tailor the elasticity of biomaterials, both native elastin derivatives and synthetic elastomers have been adopted. Although obtaining elastin from natural sources can preserve the ECM structure, low reproducibility is the main concern of using such native elastin, due to its large batch-to-batch variations. To improve that, recombinant techniques are applied to provide controllable and well-defined results for elastin synthesis. In 1990, the complete tropoelastin molecule was expressed in Escherichia coli.103 However, the location of crosslinks between synthetic tropoelastins and the alignment of tropoelastin fibers are not the same as native ones.104 By changing the genetic code on the vectors, elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) with modified elastin amino acid sequence are obtained. Although crosslinked ELPs exhibited tunable elasticity, non-adhesive properties limited their applications.105 The combination of ELPs with cell-adhesive molecules became a feasible approach in the engineering of elastic proteins.106,107 Synthetic elastomers are game changers in the development of elastic biomaterials. Although they have no structural link to elastin, they can exhibit the same mechanical functionalities. Due to their synthetic nature, synthetic elastomer-based materials can be easily modified at larger scales and molded into virtually any shape and size.

Poly(glycerol-co-sebacate) (PGS); poly(1,8-octanediol-co-citrate) (POC); polyurethanes; poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL); poly(4-hydroxybutyrate) (P4HB); poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB); and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx) are the synthetic elastomers that have been investigated for tissue engineering purposes exhibiting promising potentials. In tissue engineering, these elastomers are generally mixed or covalently connected with various materials—including nanosilicates, PEG crosslinkers, degradable polymers, native elastin, and so on—to obtain hybrid elastic materials with proper elasticity, high biocompatibility, and biodegradability, which are necessary to create specific tissues. Elastic polymers have been widely applied in tissue engineering. Although various elastic materials have been investigated, different measurement methods and different circumstances under which the measurements are carried out have made the mechanical properties of these materials incomparable.

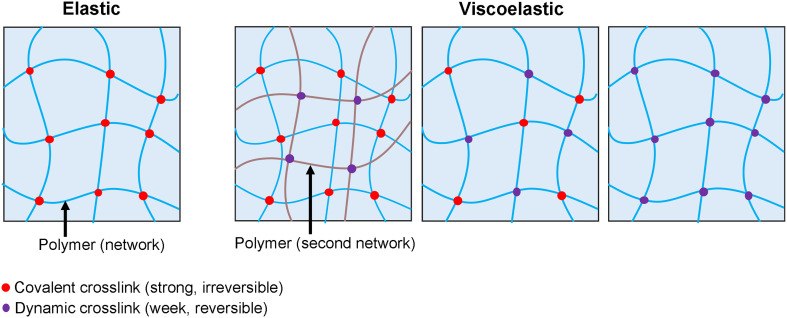

2. Biomaterials with tunable viscoelasticity

Viscoelastic materials exhibit a combination of storage of elastic energy, as a solid, and loss of mechanical energy, as a fluid. They exhibit stress relaxation in response to a constant deformation, and increased strain, or creep, in response to a constant stress.58 Different from the development of elastic materials focusing mainly on their application outcomes, the development of viscoelastic materials is still at the stage driven by fundamental biophysical studies. Based on the principles of polymer physics, several approaches have been developed to produce biomaterials with tunable viscoelastic features (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Schematic demonstration of a synthetic polymer network with tunable elasticity or viscoelasticity.

Polymers that are inert to cell binding and not susceptible to biodegradation are applied as the scaffold of viscoelastic materials. Compared with elastic materials that are composed of stable polymer networks crosslinked via strong covalent bonds, dynamic crosslinkers will markedly affect the stress–relaxation behavior of polymers (Fig. 8). For example, alginate hydrogels crosslinked by ionic and covalent bonds;108,109 alginate hydrogels covalently grafted by polyethylene glycol (PEG) crosslinked by ionic bonds;110 hyaluronic acid (HA) crosslinked with dynamic covalent hydrazone and collagen I;111,112 and artificial protein EPE covalently crosslinked via terminal cysteines and physically crosslinked via midblock domain P derived from the N-terminal fragment of the rat cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP)113 all exhibited tunable viscoelasticity independent of the initial elastic modulus through various combinations of reversable crosslinkers (weak bonds) and irreversible crosslinkers (strong covalent bonds). To validate the concept of ideal reversible polymer networks exhibiting viscoelastic behavior, dynamic covalent phenylboronic acid–diol chemistry was applied,114 and examined using hMSCs.115 Ionically, crosslinked polysaccharide alginate polymers also behaves as reversible polymer networks exhibiting tunable stress relaxation with applications in stem cell fate regulation.116 The design concept of viscoelastic polymers via the engineering of dynamic crosslinkers is also applicable to the development of active materials that offer external control over physical and chemical properties in both space and time, thus achieving adaptive functions.117

B. Biomaterials with tunable ligand density—Regulate distribution of integrins

In addition to mechanical property, the distribution of ligand is also critical for guiding the phenotypes of cultured cells. According to the underlying mechanism of integrin activation and integrin–matrix interactions, it is believed that a precisely controlled ligand distribution will lead to a functional biomaterial with similar bioactivity as natural ECM.6 Decorating a non-fouling material that resists the adsorption of protein and/or adhesion of cells with the ligand of interest is a common strategy for developing precisely controlled integrin-binding materials.118 PEG and polyethylene oxide (PEO); sulfobetaine-,119 carboxybetaine-,120 or phosphorylcholine-based zwitterionic materials; and alginate have been widely applied as non-fouling materials due to their high hydration capacity and high level of protein resistance. Therefore, the biological interactions with these materials are exclusively guided by ligands.

1. 2D substrate with tunable ligand density

Traditionally, cell adhesion surfaces were made by coating a non-fouling surface with adhesive ligands randomly. The modulation of surface bioactivity is achieved by the control of the global density of surface ligands. Nowadays, to generate an adhesive surface, besides global density—which relates to the integrin occupancy—the regulation of local density (creating ligand clustering island) for the promotion of integrin clustering is critical because clustered integrins are critical to form stable adhesion [Fig. 9(a)]. The additional level of control introduces several parameters in the material design, including the local ligand density of each nanoscale “island,” the size of island, and the spacing between islands.

FIG. 9.

Fabrication of 2D substrate with tunable ligand density. (a) Schematic illustration of fabrication strategy regarding the ligand distribution on 2D substrates. (b) Blending strategy using functionalized star polymers and crosslinked PEO polymers. (c) Blending strategy using functionalized comb polymers and nonfunctionalized bulk polymer. Fabrication of biomaterials via nanopatterning and nanolithography: during the lithographic process, the ligand is first coated to the substrate, and covered by PEG hydrogel, after pressing the photomask onto the substrate, ultraviolet light is applied to polymerize the PEG hydrogel and form the designed pattern, and the cells can be then cultured on the substrate (d). An elastomeric stamp can be first coated with an ECM material, which is then stamped onto a substrate surface to create micropatterns of the biomaterial (e). Nanofibrous networks can be created from electrically charged jets of biopolymer solutions or ECM hydrogels that are deposited onto a grounded collector (f).

The first generation of materials displaying multivalent ligands were synthesized by blending polymers functionalized with ligands to various degrees with nonfunctionalized materials. Upon film casting, a 2D substrate displaying ligand islands is obtained. By changing the ratio of the functionalized polymer and nonfunctionalized material, the spacing between islands is changed. For example, Maheshwari et al. blended a YGRGD-functionalized water-soluble star polymer with PEO arms to a crosslinked PEO hydrogel to produce cell culture surfaces [Fig. 9(b)].121 Based on the stoichiometry of the applied reactions, the researchers claimed to generate surfaces with islands containing an average of one, five, or nine ligands, with 6–300 nm distance between islands, and a global density of 1000–200 000 ligands per μm2. The adhesion capacity, cytoskeletal arrangement, migration speed, and adhesion strength of WT NR6 fibroblasts were evaluated on these substrates. The experiment results confirm that a high local density of ligands promotes integrin clustering and facilitates the formation of adhesion complexes. For a given global density, greater local density leads to higher migration speeds and higher adhesion strength.

In addition to star polymers, comb polymers are also applied for producing bioactive surfaces. Griffith et al. synthesized amphiphilic comb copolymers that served as nonfouling interfaces via free radical polymerization of methyl methacrylate (MMA) and methacrylate bearing a PEO pendant group. N-hydroxysuccinimide chemistry was used to couple RGD ligands to the polymer chain [Fig. 9(c)]. By changing the ratio of ligand to PMMA-based polymer during coupling, a series of co-polymers containing an average of 1.7–5.4 peptides per polymer chain were obtained.122,123 By blending different ratios of functional and nonfunctional polymers, polymer films with global ligand density ranging from 12.4 to50.9 μg ligands per mg polymer were obtained. Since it was assumed that the comb polymers would form random coils, the random distribution of functional polymers with various local density generated ligand islands. A size control of the functional polymer was considered as the approach to control the size of the islands. Through the blending technique, polymer films with an island distance in the range ≈ 50–300 nm were produced. Adhesion experiments of WT NR6 fibroblasts implied that ligand clustering resulted in adhesion reinforcement. By adjusting the length of PEO tether, it was discovered that longer lengths improved the integrin–ligand binding ability. To achieve a better control of the local density, Heath et al. used reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization for the synthesis of methyl methacrylate/polyethylene glycol methacrylate/acrylate-PEG-RGD comb copolymer. Bioactive films with global density ranging from 0.4 to 4.4 μg ligands per mg polymer and local density of 0–2.4 ligands per island were produced for application in blood-contacting.

Suo and Mooney et al. developed ionically crosslinked alginate hydrogels as nonfouling substrates for ligand decoration.108,125–129 The carboxylic acid groups on the sodium alginate chains are applied for coupling reaction with RGD-containing peptides. Through NHS/EDC catalyzed coupling reactions, linear alginate chains with an average of 1–25 ligands were synthesized. Blending ligand-functionalized alginate chains with unfunctionalized alginate chains and crosslinking them through the addition of calcium sulfate led to the formation of a bioactive surface [Fig. 9(d)]. Similar to the blending of comb polymers, the ligand island size was controlled by the size of the functionalized alginate chain, which was about 36 nm. Changing the blend ratio led to average island spacing ranging from 36 to 168 nm. A 2D Monte Carlo simulation predicted that the global density of RGD ligands varied between 0.125 and 80 μg RGD per mg alginate. Mouse preosteoblasts, primary human fibroblasts, and myoblasts were cultured on the alginate substrates, and it was found that the cell growth rate increased as the global density of the ligand increased; osteogenesis was significantly increased with closely spaced islands for a given global density.

Alternative to the coupling reactions that have been widely applied for the synthesis of functional polymers, Cooper-White et al. applied a noncovalent approach to spatially conjugate β-cyclodextrin modified ligands onto adamantane-terminated polystyrene-b-poly(ethylene oxide) (PS-PEO-Ada) via “host–guest” chemistry.129 Blending the adamantane-functionalized polymer with nonfunctionalized polymer led to a control of ligand amount that could be conjugated to the material surface ranging from 1000 to 3500 RGD μm−2. Although such a method presented better control of ligand occupancy, the hydrophobicity of polystyrene resulting in protein absorption limited the application of these materials. Overall, although the blending method exhibited certain control over the ligand occupancy and distribution on the 2D surface, it does not enable precise control of the distribution of ligand islands and the correlated local density of ligands. Therefore, although the produced bioactive surfaces promoted a variety of cell behaviors, they are inadequate to address fundamental biophysical questions.

To achieve a higher degree of spatial control on ligand presentation, several micropatterning techniques have been developed to print ECM components onto synthetic materials producing desired patterns.3 Photolithography, which uses light to transfer a geometric pattern from an optical mask to a photosensitive chemical photoresist on the substrate, can design differential ligand presentation on the substrate with a resolution of a few micrometers, which is comparable to the size of FA [Fig. 9(d)].130 By taking advantage of the nanometer scale of micelles formed by self-assembly of a polystyrene-block-poly(2-vinylpyridine) copolymer, Möller et al. produced planar non-fouling surfaces patterned with biofunctionalized arrays of gold nanoparticles. The size of the gold particles between 1 and 15 nm was controlled via the reduction reaction of tetrachloroaurate (HAuCl4). The interparticle distance ranging from 30 to 250 nm was tuned by varying the arm length or concentration of micelles. Regarding the size of integrin receptor with a diameter of 8–12 nm, the researchers adjusted the size of gold particle to tune the possible number of integrin ligands that could be coupled to the particle and this eventually led to the control of global and local density. To precisely control gold particle arrays without using micelles, Sheetz et al. also developed a nanoimprint lithography131 technique for producing a surface of uniformly spaced gold nanoparticles with size ≤10 nm. Through such approaches, a series of precisely controlled bioactive surfaces were produced and applied in the study of fundamental questions, for example, the critical spacing between ligands for improved cell spreading, focal adhesion assembly, and migration speed. However, the high cost of photolithographic equipment and the requirement of special, clean rooms limits its popularity.

An alternative technique is the elastomeric stamp. The microstamp can be first coated with ECM components, then stamped onto a substrate to create micropatterns.132 Elastomeric stamping can take advantage of microchannels and microfluidics techniques to improve the precision of ligand spatial presentation and this is much cheaper and procedurally more simple compared to photolithography [Fig. 9(e)].133 To further increase the resolution of ligands presentation, nanofiber lithography has been developed. Fibrous nanopatterned scaffolds can be printed on a scale of 200–1000 nm to control the spatial distribution of integrin precisely [Fig. 9(f)].134

2. Self-assembled integrin ligands—Adaptive matrix

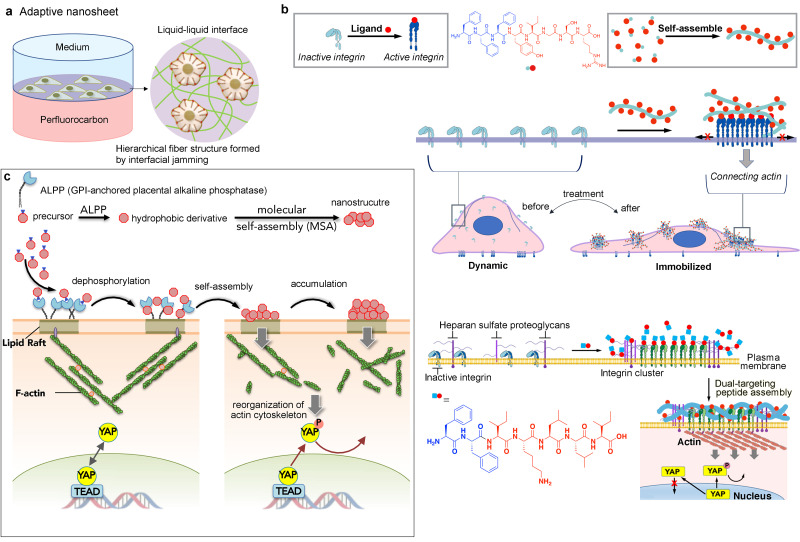

Recently, Ariga et al. reported their efforts to use cell mediation at early stages of biomaterial construction. By applying a liquid interfacial technique in the production of bioactive substrates, they constructed a dynamic 2D substrate mediated by cells that are cultured on the surface. Particularly, fibronectin on liquid interface is continuously remodeled by MSC traction force-induced interfacial jamming, which eventually leads to the self-assembly (SA) of fibronectin forming matrix fibers adaptive to the MSCs [Fig. 10(a)].135 Inspired by the reciprocal interactions between cells and the ECM, together with the upregulated expression of integrin in metastatic tumors and the interplay between heparan sulfate (HS) and integrin signaling, Zhang et al. formulated a series of aromatic peptide-based ligands.136 Through molecular self-assembly in aqueous environments instructed by the distribution of integrin or heparan sulfate (HS) on the plasma membrane, fibrous matrices adaptive to several types of cancer cells were formed.138–140 Specifically, by conjugating the tripeptide self-assembly building block FFF to the N-terminal of laminin-derived peptide YIGSR, a self-assembling version of an integrin ligand was synthesized. Through its strong affinity and adhesiveness, the self-assembled ligands formed fibrous-structured microdomains selectively adhering to the apical membrane of glioma cell F98. The synthetic matrix further led to F98 cell elongation and reduction of focal adhesion, which eventually inhibited migration and invasion in vitro. [Fig. 10(b)] By conjugating the dipeptide self-assembly building block FF to the N-terminal of laminin α1 chain-derived IKLLI motif representing a binding site for both integrin β1 and HS, a self-assembling version of a dual-targeting ligand was synthesized. The peptide self-assembled into nanofibrous microdomains specifically on the cancer cell membrane, triggering spatial organization of integrins. Through the actin cytoskeleton that physically connects to integrin clusters, the oncogene yes-associated protein,71 which regulates cancer metastasis, is deactivated [Fig. 10(b)].

FIG. 10.

Construction of ECM-mimicking biomaterials regulating integrin distributions via (a) fluid–fluid interface technique, (b) integrin-instructed peptide self-assembly, and (c) lipid raft-targeted self-assembly instructed by enzyme.

Lipid raft, being a spatial platform for activated integrins, provides another peptide assembly binding site for the regulation of integrin distribution.140 Inspired by reports that ovarian cancer cells specifically accumulate the phosphatase protein ALPP on lipid rafts that physically link to actin cytoskeleton, Zhang et al. developed a molecular self-assembly63 technology that selectively halts cancer cell proliferation by inactivating YAP—a ruthenium-complex-peptide precursor molecule that, upon cleavage of phosphate groups, undergoes self-assembly to form nanostructures specifically on lipid rafts of ovarian cancer cell. The MSAs exert potent, cancer cell-specific antiproliferative effects in multiple cancer cell lines and in mouse xenograft tumor models [Fig. 10(c)].140,141 Although the outcome of molecular self-assembly techniques is intriguing and promising, the underlining mechanism, especially the direct correlations between the packing mode of integrin ligands on the surface of nanostructures and the integrin activation, requires further and in-depth exploration. In regard to the nature of synthetic molecular self-assembly, which is a true bottom-up approach for the fabrication of biomaterials, there are great potentials in creating unique features that cannot be achieved by top-down techniques that have been widely employed in the field of materials design.

V. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The native ECM presents an ideal microenvironmental niche to support tissue growth and organ maintenance. The inherent biochemical and mechanical cues existing in ECMs regulate cell phenotype and function via integrin receptors in tissue development, in cancer progression, and in response to wound healing. In accordance with a great body of previous studies and what is highlighted in the current articles, recent advances in innovative material design provide promising opportunities to regulate integrin spatial distribution and mediate cell function. However, major hurdles remain for the development and use of integrin-targeting biomaterials, including the insufficient understanding of ECM composition, topography, dynamics, as well as the related cell response, and the difficulty of recreating the complex ultrastructure and composition of the native matrix.

To further understand and control adhesion-mediated cell behavior, both a precise characterization of the matrix and a detailed investigation of the cellular sensory machinery will be critical. In recent years, a remarkable breakthrough has been achieved in both aspects: novel techniques of gene modulation provide access to selectively remove, mutate, and overexpress individual genes while optogenetics enables the precise control of protein activity, which helps us to understand the fundamental mechanisms of cellular behaviors. In parallel, proteomic and bioinformatic techniques have begun to provide a more rigorous mapping of ECM components, enabling a detailed investigation of ECM molecules and their integration into biomaterials. Together with the rapid development of nanotechnology, we believe that the era of tailoring synthetic biomaterials for high-dimensional control of cellular functions and applications in biomedical science via regulating integrins accurately and combinatorically is coming.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by the Takeda Science Foundation for Medical Science and JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 21H02063).

AUTHOR DECLARATION

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1. Ruprecht V., Monzo P., Ravasio A., Yue Z., Makhija E., Strale P. O., Gauthier N., Shivashankar G. V., Studer V., Albiges-Rizo C., and Viasnoff V., J. Cell Sci. 130(1), 51–61 (2017). 10.1242/jcs.196162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kai F., Drain A. P., and Weaver V. M., Dev. Cell 49(3), 332–346 (2019). 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Geiger B., Spatz J. P., and Bershadsky A. D., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10(1), 21–33 (2009). 10.1038/nrm2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang Y., Wang K., Gu X., and Leong K. W., J. Eng. 3(1), 36–54 (2017). 10.1016/J.ENG.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nasrollahi S., Banerjee S., Qayum B., Banerjee P., and Pathak A., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3(11), 2980–2986 (2017). 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amani H., Arzaghi H., Bayandori M., Dezfuli A. S., Pazoki-Toroudi H., Shafiee A., and Moradi L., Adv. Mater. Interfaces 6(13), 1900572 (2019). 10.1002/admi.201900572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kechagia J. Z., Ivaska J., and Roca-Cusachs P., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20(8), 457–473 (2019). 10.1038/s41580-019-0134-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harburger D. S. and Calderwood D. A., J. Cell Sci. 122(Pt. 2), 159–163 (2009). 10.1242/jcs.018093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li S., Nih L. R., Bachman H., Fei P., Li Y., Nam E., Dimatteo R., Carmichael S. T., Barker T. H., and Segura T., Nat. Mater. 16(9), 953–961 (2017). 10.1038/nmat4954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clark A. Y., Martin K. E., Garcia J. R., Johnson C. T., Theriault H. S., Han W. M., Zhou D. W., Botchwey E. A., and Garcia A. J., Nat. Commun. 11(1), 114 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-019-14000-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim S. H., Turnbull J., and Guimond S., J. Endocrinol. 209(2), 139–151 (2011). 10.1530/JOE-10-0377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dhavalikar P., Robinson A., Lan Z., Jenkins D., Chwatko M., Salhadar K., Jose A., Kar R., Shoga E., Kannapiran A., and Cosgriff‐Hernandez E., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 9(23), 2000795 (2020). 10.1002/adhm.202000795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao J., Santino F., Giacomini D., and Gentilucci L., Biomedicines 8(9), 307 (2020). 10.3390/biomedicines8090307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cavalcanti-Adam E. A., Volberg T., Micoulet A., Kessler H., Geiger B., and Spatz J. P., Biophys. J. 92(8), 2964–2974 (2007). 10.1529/biophysj.106.089730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang X., Yan C., Ye K., He Y., Li Z., and Ding J., Biomaterials 34(12), 2865 (2013). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oria R., Wiegand T., Escribano J., Elosegui-Artola A., Uriarte J. J., Moreno-Pulido C., Platzman I., Delcanale P., Albertazzi L., Navajas D., Trepat X., Garcia-Aznar J. M., Cavalcanti-Adam E. A., and Roca-Cusachs P., Nature 552(7684), 219–224 (2017). 10.1038/nature24662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karimi F., O'Connor A. J., Qiao G. G., and Heath D. E., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 7(12), e1701324 (2018). 10.1002/adhm.201701324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saux G. L., Magenau A., Gunaratnam K., Kilian K. A., Bocking T., Gooding J. J., and Gaus K., Biophys. J. 101(4), 764–773 (2011). 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Welf E. S., Naik U. P., and Ogunnaike B. A., Biophys. J. 103(6), 1379–1389 (2012). 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ekerdt B. L., Segalman R. A., and Schaffer D. V., Biotechnol. J. 8(12), 1411–1423 (2013). 10.1002/biot.201300302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. R., and Schwartz M. A., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11(9), 633–643 (2010). 10.1038/nrm2957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hussey G. S., Dziki J. L., and Badylak S. F., Nat. Rev. Mater. 3(7), 159–173 (2018). 10.1038/s41578-018-0023-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frantz C., Stewart K. M., and Weaver V. M., J. Cell Sci. 123(Pt 24), 4195–4200 (2010). 10.1242/jcs.023820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. White D. J., Puranen S., Johnson M. S., and Heino J., Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36(8), 1405–1410 (2004). 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stipp C. S., Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 12, E3 (2010). 10.1017/S1462399409001355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris E. S., McIntyre T. M., Prescott S. M., and Zimmerman G. A., J. Biol. Chem. 275(31), 23409–23412 (2000). 10.1074/jbc.R000004200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Danen E. H. J., Sonneveld P., Brakebusch C., Fassler R., and Sonnenberg A., J. Cell Biol. 159(6), 1071–1086 (2002). 10.1083/jcb.200205014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mui K. L., Chen C. S., and Assoian R. K., J. Cell Sci. 129(6), 1093–1100 (2016). 10.1242/jcs.183699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papusheva E. and Heisenberg C. P., EMBO J. 29(16), 2753–2768 (2010). 10.1038/emboj.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winograd-Katz S. E., Fassler R., Geiger B., and Legate K. R., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15(4), 273–288 (2014). 10.1038/nrm3769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zaidel-Bar R., Itzkovitz S., Ma'ayan A., Iyengar R., and Geiger B., Nat. Cell Biol. 9(8), 858–867 (2007). 10.1038/ncb0807-858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun Z., Costell M., and Fassler R., Nat. Cell Biol. 21(1), 25–31 (2019). 10.1038/s41556-018-0234-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chastney M. R., Conway J. R. W., and Ivaska J., Curr. Biol. 31(10), R536–R542 (2021). 10.1016/j.cub.2021.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Su Y., Xia W., Li J., Walz T., Humphries M. J., Vestweber D., Cabanas C., Lu C., and Springer T. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113(27), E3872–3881 (2016). 10.1073/pnas.1605074113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miyamoto S., Akiyama S. K., and Yamada K. M., Science 267(5199), 883–885 (1995). 10.1126/science.7846531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klapholz B. and Brown N. H., J. Cell Sci. 130(15), 2435–2446 (2017). 10.1242/jcs.190991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Humphries J. D., Wang P., Streuli C., Geiger B., Humphries M. J., and Ballestrem C., J. Cell Biol. 179(5), 1043–1057 (2007). 10.1083/jcb.200703036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vicente-Manzanares M. and Horwitz A. R., J. Cell Sci. 124(Pt 23), 3923–3927 (2011). 10.1242/jcs.095653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ibata N. and Terentjev E. M., Biophys. J. 119(10), 2063–2073 (2020). 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun Z., Lambacher A., and Fassler R., Curr. Biol. 24(17), R801–803 (2014). 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi C. K., Vicente-Manzanares M., Zareno J., Whitmore L. A., Mogilner A., and Horwitz A. R., Nat. Cell Biol. 10(9), 1039–1050 (2008). 10.1038/ncb1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oakes P. W., Beckham Y., Stricker J., and Gardel M. L., J. Cell Biol. 196(3), 363–374 (2012). 10.1083/jcb.201107042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Legerstee K., Geverts B., Slotman J. A., and Houtsmuller A. B., Sci. Rep. 9(1), 10460 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-46905-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuo J. C., Han X., Hsiao C. T., J. R. Yates, 3rd , and Waterman C. M., Nat. Cell Biol. 13(4), 383–393 (2011). 10.1038/ncb2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lehtimaki J. I., Rajakyla E. K., Tojkander S., and Lappalainen P., eLife 10, e60710 (2021). 10.7554/eLife.60710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kassianidou E., Probst D., Jager J., Lee S., Roguet A. L., Schwarz U. S., and Kumar S., Cell Rep. 27(6), 1897–1909 e1894 (2019). 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barber-Perez N., Georgiadou M., Guzman C., Isomursu A., Hamidi H., and Ivaska J., J. Cell Sci. 133(12), jcs242909 (2020) 10.1242/jcs.242909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ezratty E. J., Partridge M. A., and Gundersen G. G., Nat. Cell Biol. 7(6), 581–590 (2005). 10.1038/ncb1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kerstein P. C., Patel K. M., and Gomez T. M., J. Neurosci. 37(6), 1568–1580 (2017). 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2769-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gupton S. L. and Waterman-Storer C. M., Cell 125(7), 1361–1374 (2006). 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carragher N. O. and Frame M. C., Trends Cell Biol. 14(5), 241–249 (2004). 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Broussard J. A., Webb D. J., and Kaverina I., Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20(1), 85–90 (2008). 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Huettner N., Dargaville T. R., and Forget A., Trends Biotechnol. 36(4), 372–383 (2018). 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deeg J. A., Louban I., Aydin D., Selhuber-Unkel C., Kessler H., and Spatz J. P., Nano Lett. 11(4), 1469–1476 (2011). 10.1021/nl104079r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Benitez P. L., Mascharak S., Proctor A. C., and Heilshorn S. C., Integr. Biol. 8(1), 50–61 (2016). 10.1039/C5IB00258C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu W. F. and Chen C. S., Mater. Today 8(12), 28–35 (2005). 10.1016/S1369-7021(05)71222-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lampi M. C. and Reinhart-King C. A., Sci. Transl. Med. 10(422), eaao0475 (2018). 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao0475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chaudhuri O., Cooper-White J., Janmey P. A., Mooney D. J., and Shenoy V. B., Nature 584(7822), 535–546 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2612-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Doss B. L., Pan M., Gupta M., Grenci G., Mege R. M., Lim C. T., Sheetz M. P., Voituriez R., and Ladoux B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117(23), 12817–12825 (2020). 10.1073/pnas.1917555117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tilghman R. W., Cowan C. R., Mih J. D., Koryakina Y., Gioeli D., Slack-Davis J. K., Blackman B. R., Tschumperlin D. J., and Parsons J. T., PLoS One 5(9), e12905 (2010). 10.1371/journal.pone.0012905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wells R. G., Hepatology 47(4), 1394–1400 (2008). 10.1002/hep.22193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Seewaldt V., Nat. Med. 20(4), 332–333 (2014). 10.1038/nm.3523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bangasser B. L., Shamsan G. A., Chan C. E., Opoku K. N., Tuzel E., Schlichtmann B. W., Kasim J. A., Fuller B. J., McCullough B. R., Rosenfeld S. S., and Odde D. J., Nat. Commun. 8, 15313 (2017). 10.1038/ncomms15313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wen J. H., Vincent L. G., Fuhrmann A., Choi Y. S., Hribar K. C., Taylor-Weiner H., Chen S., and Engler A. J., Nat. Mater. 13(10), 979–987 (2014). 10.1038/nmat4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Park J. S., Chu J. S., Tsou A. D., Diop R., Tang Z., Wang A., and Li S., Biomaterials 32(16), 3921–3930 (2011). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Charrier E. E., Pogoda K., Wells R. G., and Janmey P. A., Nat. Commun. 9(1), 449 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-018-02906-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Teixeira A. I., Ilkhanizadeh S., Wigenius J. A., Duckworth J. K., Inganas O., and Hermanson O., Biomaterials 30(27), 4567–4572 (2009). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Moshayedi P., Ng G., Kwok J. C., Yeo G. S., Bryant C. E., Fawcett J. W., Franze K., and Guck J., Biomaterials 35(13), 3919–3925 (2014). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Engler A. J., Griffin M. A., Sen S., Bonnemann C. G., Sweeney H. L., and Discher D. E., J. Cell Biol. 166(6), 877–887 (2004). 10.1083/jcb.200405004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cameron A. R., Frith J. E., and Cooper-White J. J., Biomaterials 32(26), 5979–5993 (2011). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cameron A. R., Frith J. E., Gomez G. A., Yap A. S., and Cooper-White J. J., Biomaterials 35(6), 1857–1868 (2014). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chaudhuri O., Gu L., Darnell M., Klumpers D., Bencherif S. A., Weaver J. C., Huebsch N., and Mooney D. J., Nat. Commun. 6, 6365 (2015). 10.1038/ncomms7365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nam S., Gupta V. K., Lee H. P., Lee J. Y., Wisdom K. M., Varma S., Flaum E. M., Davis C., West R. B., and Chaudhuri O., Sci. Adv. 5(8), eaaw6171 (2019). 10.1126/sciadv.aaw6171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Nam S. and Chaudhuri O., Nat. Phys. 14(6), 621–628 (2018). 10.1038/s41567-018-0092-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chaudhuri O., Gu L., Klumpers D., Darnell M., Bencherif S. A., Weaver J. C., Huebsch N., Lee H. P., Lippens E., Duda G. N., and Mooney D. J., Nat. Mater. 15(3), 326 (2016). 10.1038/nmat4489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nguyen A. T., Sathe S. R., and Yim E. K. F., J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 28(18), 183001 (2016). 10.1088/0953-8984/28/18/183001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Abrams G. A., Goodman S. L., Nealey P. F., Franco M., and Murphy C. J., Cell Tissue Res. 299(1), 39–46 (2000). 10.1007/s004410050004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kim D. H., Lipke E. A., Kim P., Cheong R., Thompson S., Delannoy M., Suh K. Y., Tung L., and Levchenko A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107(2), 565–570 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.0906504107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Monaghan P., Warburton M. J., Perusinghe N., and Rudland P. S., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 80(11), 3344–3348 (1983). 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Metavarayuth K., Sitasuwan P., Zhao X., Lin Y., and Wang Q., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2(2), 142–151 (2016). 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hoffman-Kim D., Mitchel J. A., and Bellamkonda R. V., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 12, 203–231 (2010). 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jeon H., C. G. Simon, Jr. , and Kim G., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 102(7), 1580–1594 (2014). 10.1002/jbm.b.33158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tawfick S., De Volder M., Copic D., Park S. J., Oliver C. R., Polsen E. S., Roberts M. J., and Hart A. J., Adv. Mater. 24(13), 1628–1674 (2012). 10.1002/adma.201103796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Teo B. K., Ankam S., Chan L. Y., and Yim E. K., Methods Cell Biol. 98, 241–294 (2010). 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)98011-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Yim E. K. and Leong K. W., Nanomedicine 1(1), 10–21 (2005). 10.1016/j.nano.2004.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Washburn N. R., Yamada K. M., C. G. Simon, Jr. , Kennedy S. B., and Amis E. J., Biomaterials 25(7–8), 1215–1224 (2004). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Arnold M., Cavalcanti-Adam E. A., Glass R., Blummel J., Eck W., Kantlehner M., Kessler H., and Spatz J. P., ChemPhysChem 5(3), 383–388 (2004). 10.1002/cphc.200301014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lamers E., van Horssen R., te Riet J., van Delft F. C. M. J. M., Luttge R., Walboomers X. F., and Jansen J. A., Eur. Cells Mater. 20, 329–343 (2010). 10.22203/eCM.v020a27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lee J., Abdeen A. A., Wycislo K. L., Fan T. M., and Kilian K. A., Nat. Mater. 15(8), 856 (2016). 10.1038/nmat4610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Luu T. U., Gott S. C., Woo B. W. K., Rao M. P., and Liu W. F., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7(51), 28665–28672 (2015). 10.1021/acsami.5b10589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Christopherson G. T., Song H., and Mao H. Q., Biomaterials 30(4), 556–564 (2009). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yang F., Murugan R., Wang S., and Ramakrishna S., Biomaterials 26(15), 2603–2610 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tonazzini I., Meucci S., Faraci P., Beltram F., and Cecchini M., Biomaterials 34(25), 6027–6036 (2013). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Seonwoo H., Bae W. G., Park S., Kim H. N., Choi K. S., Lim K. T., Hyun H., Kim J. W., Kim J., and Chung J. H., IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 15(8), 835–842 (2016). 10.1109/TNB.2016.2631641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Moffa M., Sciancalepore A. G., Passione L. G., and Pisignano D., Small 10(12), 2439–2450 (2014). 10.1002/smll.201303179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kim J., Bae W. G., Choung H. W., Lim K. T., Seonwoo H., Jeong H. E., Suh K. Y., Jeon N. L., Choung P. H., and Chung J. H., Biomaterials 35(33), 9058–9067 (2014). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kubo K., Tsukimura N., Iwasa F., Ueno T., Saruwatari L., Aita H., Chiou W. A., and Ogawa T., Biomaterials 30(29), 5319–5329 (2009). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Aamodt J. M. and Grainger D. W., Biomaterials 86, 68–82 (2016). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Moroni F. and Mirabella T., Am. J. Stem Cells 3(1), 1–20 (2014), see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3960753/. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Taylor D. A., Sampaio L. C., Ferdous Z., Gobin A. S., and Taite L. J., Acta Biomater. 74, 74–89 (2018). 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gilpin A. and Yang Y., Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 9831534. 10.1155/2017/9831534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Coenen A. M. J., Bernaerts K. V., Harings J. A. W., Jockenhoevel S., and Ghazanfari S., Acta Biomater. 79, 60–82 (2018). 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Indik Z., Abrams W. R., Kucich U., Gibson C. W., Mecham R. P., and Rosenbloom J., Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 280(1), 80–86 (1990). 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90521-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bedell-Hogan D., Trackman P., Abrams W., Rosenbloom J., and Kagan H., J. Biol. Chem. 268(14), 10345–10350 (1993). 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)82207-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Nettles D. L., Chilkoti A., and Setton L. A., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 62(15), 1479–1485 (2010). 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Annabi N., Zhang Y. N., Assmann A., Sani E. S., Cheng G., Lassaletta A. D., Vegh A., Dehghani B., Ruiz-Esparza G. U., Wang X., Gangadharan S., Weiss A. S., and Khademhosseini A., Sci. Transl. Med. 9(410), eaai7466 (2017). 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai7466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Muiznieks L. D. and Keeley F. W., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3(5), 661–679 (2017). 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Zhao X. H., Huebsch N., Mooney D. J., and Suo Z. G., J. Appl. Phys. 107, 063509 (2010). 10.1063/1.3343265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Vining K. H., Stafford A., and Mooney D. J., Biomaterials 188, 187–197 (2019). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Nam S., Stowers R., Lou J., Xia Y., and Chaudhuri O., Biomaterials 200, 15–24 (2019). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Lou J., Stowers R., Nam S., Xia Y., and Chaudhuri O., Biomaterials 154, 213–222 (2018). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Loebel C., Mauck R. L., and Burdick J. A., Nat. Mater. 18, 883 (2019). 10.1038/s41563-019-0307-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Dooling L. J., Buck M. E., Zhang W. B., and Tirrell D. A., Adv. Mater. 28, 4651–4657 (2016). 10.1002/adma.201506216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Parada G. A. and Zhao X., Soft Matter 14(25), 5186–5196 (2018). 10.1039/C8SM00646F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Tang S., Ma H., Tu H.-C., Wang H.-R., Lin P.-C., and Anseth K. S., Adv. Sci. 5, 1800638 (2018). 10.1002/advs.201800638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Chaudhuri O., Gu L., Klumpers D., Darnell M., Bencherif S. A., Weaver J. C., Huebsch N., Lee H.-P., Lippens E., Duda G. N., and Mooney D. J., Nat. Mater. 15, 9 (2016). 10.1038/nmat4489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ozkale B., Sakar M. S., and Mooney D. J., Biomaterials 267, 120497 (2021). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Place E. S., Evans N. D., and Stevens M. M., Nat. Mater. 8(6), 457–470 (2009). 10.1038/nmat2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Goldfinger L. E., Han J., Kiosses W. B., Howe A. K., and Ginsberg M. H., J. Cell Biol. 162(4), 731–741 (2003). 10.1083/jcb.200304031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Brown T. E., Carberry B. J., Worrell B. T., Dudaryeva O. Y., McBride M. K., Bowman C. N., and Anseth K. S., Biomaterials 178, 496–503 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Maheshwari G., Brown G., Lauffenburger D. A., Wells A., and Griffith L. G., J. Cell Sci. 113(Pt 10), 1677–1686 (2000). 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Irvine D. J., Mayes A. M., and Griffith L. G., Biomacromolecules 2, 85–94 (2001). 10.1021/bm005584b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Koo L. Y., Irvine D. J., Mayes A. M., Lauffenburger D. A., and Griffith L. G., J Cell Sci. 115, 1423–1433 (2002). 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Hsiong S. X., Carampin P., Kong H. J., Lee K. Y., and Mooney D. J., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 85(1), 145–156 (2008). 10.1002/jbm.a.31521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Comisar W. A., Kazmers N. H., Mooney D. J., and Linderman J. J., Biomaterials 28(30), 4409–4417 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Huang J., Grater S. V., Corbellini F., Rinck S., Bock E., Kemkemer R., Kessler H., Ding J., and Spatz J. P., Nano Lett. 9(3), 1111–1116 (2009). 10.1021/nl803548b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Karimi F., McKenzie T. G., O'Connor A. J., Qiao G. G., and Heath D. E., J. Mater. Chem. B 5(30), 5942–5953 (2017). 10.1039/C7TB01298E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Lee K. Y., Alsberg E., Hsiong S., Comisar W., Linderman J., Ziff R., and Mooney D., Nano Lett. 4(8), 1501–1506 (2004). 10.1021/nl0493592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Li H., Frith J., and Cooper-White J. J., Biomarcromolecules 15, 43–52 (2014). 10.1021/bm4012562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Ermis M., Antmen E., and Hasirci V., Bioact. Mater. 3(3), 355–369 (2018). 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Brody S., Anilkumar T., Liliensiek S., Last J. A., Murphy C. J., and Pandit A., Tissue Eng. 12(2), 413–421 (2006). 10.1089/ten.2006.12.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Thery M. and Piel M., Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009(7), pdb prot5255. 10.1101/pdb.prot5255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Tien J., Nelson C. M., and Chen C. S., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99(4), 1758–1762 (2002). 10.1073/pnas.042493399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Changede R., Cai H., Wind S. J., and Sheetz M. P., Nat. Mater. 18(12), 1366–1375 (2019). 10.1038/s41563-019-0460-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Jia X., Minami K., Uto K., Chang A. C., Hill J. P., Nakanishi J., and Ariga K., Adv. Mater. 32(4), 1905942 (2020). 10.1002/adma.201905942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Wu X., Hu X., and Zhang Y., Chem. Lett. 50(3), 405–410 (2021). 10.1246/cl.200788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Roy S. R., Li G., Hu X., Zhang S., Yukawa S., Du E., and Zhang Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12(17), 19277–19284 (2020). 10.1021/acsami.0c02235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Mang D., Roy S. R., Zhang Q., Hu X., and Zhang Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13(15), 17236–17242 (2021). 10.1021/acsami.1c00934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Mang D., Roy S. R., Hoh H. H., Wu X., Zhang J., Jin C., and Zhang Y., Langmuir 36(14), 3750–3757 (2020). 10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c00291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Li G., Sasaki T., Asahina S., Roy M. C., Mochizuki T., Koizumi K., and Zhang Y., Chem 2(2), 283–298 (2017). 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Li G., Hu X., Nie P., Mang D., Jiao S., Zhang S., Roy S. R., Yukawa S., Asahina S., Sugasawa H., Cortes W., Zhou Z., and Zhang Y., Nano Lett. 21(1), 747–755 (2021). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c04435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.