Abstract

Short-chain fatty acids are known modulators of host–microbe interactions and can affect human health, inflammation, and outcomes of microbial infections. Acetate is the most abundant but least well-studied of these modulators, with most studies focusing on propionate and butyrate, which are considered to be more potent. In this mini-review, we summarize current knowledge of acetate as an important anti-inflammatory modulator of interactions between hosts and microorganisms. This includes a summary of the pathways by which acetate is metabolized by bacteria and human cells, the functions of acetate in bacterial cells, and the impact that microbially derived acetate has on human immune function.

Keywords: acetate, host–microbe interactions, metabolism, microbiology, short-chain fatty acid

Introduction

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are molecules with fewer than six carbon atoms in the aliphatic tail, and in biological systems the most commonly found representatives are acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4). These SCFAs are ubiquitously found in natural environments, produced by bacterial, fungal, and mammalian cells during anaerobic fermentation and aerobic fermentative respiration [1–10].

In the human body, SCFAs are found in the highest concentrations in the intestinal tract, where bacteria metabolize indigestible saccharides and other molecules and release SCFAs as end products. SCFA concentrations in the intestine range from 20 to 140 mM, with acetate accounting for 60–75% of this and exceeding propionate and butyrate at least twofold in concentration [11,12]. It has been estimated that 36% of colonic-derived acetate becomes systemically available, reaching 50–200 μM in venous serum [11,13–18]. In other bacterially colonized body sites such as the oral cavity and urogenital tract, acetate is detected at 6–38 mM and up to 120 mM (depending on the presence or absence of infection/inflammation), respectively [19]. Acetate is particularly suited to exerting systemic effects, as, unlike propionate or butyrate, it can traverse cell membranes without requiring a specific uptake system [20,21].

Bacterial acetate metabolism pathways are redundant and tightly regulated

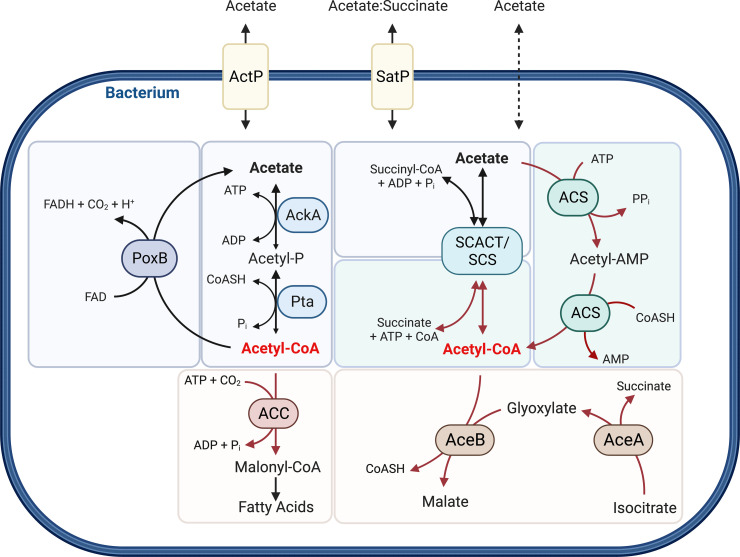

Acetate production by bacteria is mediated by two main pathways that often occur together in the same microorganism and show functional redundancy. These pathways either involve acetate kinase and phosphotransacetylase (AckA-Pta), a set of reactions that allows ATP production via substrate-level phosphorylation, or a pyruvate : menaquinone oxidoreductase denoted PoxB or CidC [22–35] (Figure 1). In addition to passive membrane permeability, acetate release and uptake can be effected by either an acetate permease (encoded by actP) or an acetate/succinate symporter (encoded by satP) [36,37] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the bacterial acetate metabolism pathways, at which acetyl-CoA (red) is a central metabolite.

Acetate can be imported into the cell by acetate permease (ActP), an acetate/succinate symporter (SatP), and/or passive diffusion. Acetate formation (blue) can occur via the reversible acetate kinase (AckA) and phosphotransacetylase (Pta) reaction, a pyruvate:menaquinone oxidoreductase (PoxB), or the reversible succinyl-CoA : Ac-CoA transferase and succinyl-CoA synthetase (SCACT/SCS). Acetate assimilation into Acetyl-CoA (green) can occur via acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) and/or SCACT/SCS. Assimilation of Acetyl-CoA into biomass (yellow) can use multiple pathways, including assimilation into fatty acids (ACC, acetyal-CoA carboxylase) of TCA cycle intermediates (AceA, isocitrate lyase; AceB, malate synthase). Abbreviations: AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CoASH/CoA, coenzyme A; Pi, phosphate; PPi, diphosphate; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide (quinone); FADH, flavin adenine dinucleotide (semiquinone); CO2, carbon dioxide; H+, proton. This figure was created using BioRender.

While acetate is mostly a metabolic endproduct in bacteria, there are also several mechanisms by which bacteria can assimilate acetate into biomass, usually via the formation of acetyl-coenzyme A (Ac-CoA) that can then be assimilated via the glyoxylate cycle and the TCA cycle, contributing to biosynthetic intermediate production and energy generation [32,33,38–41]. A typical enzyme in Ac-CoA production is Ac-CoA synthetase (ACS, also known as Ac-CoA ligase), which is found in diverse bacteria such as Enterobacteria, Pseudomonads, Neisseria spp., and Mycobacterium spp. [24–32,34,39–49] (Figure 1). An additional, reversible pathway that uses succinyl-CoA : Ac-CoA transferase and a succinyl-CoA synthetase has been identified in flagellate protozoans [50], eukaryotes [51,52], and bacteria [53,54] (Figure 1). In bacteria, the succinyl-CoA : Ac-CoA transferase can be used to consume acetate, e.g. in Acetobacter [54] while Cutibacteria spp., present on skin and mucosal surfaces, use it to produce acetate [53]. Other mechanisms for acetate assimilation include the methyl malonyl-CoA pathway [55–57] or glutamate-dependent acetate uptake into the TCA cycle in Neisseria meningitidis, an organism that lacks isocitrate lyase and malate synthase [32,34] (Figure 1). The AckA-Pta pathway that usually leads to acetate production has also been shown to be reversible. However, it exhibits low overall activity in the reverse direction [42–45].

For the majority of bacteria, acetate is not the most preferred carbon source, and its utilization can be subject to catabolite repression if glucose is present [26,27,58–62]. There is also evidence of RpoS-mediated activation of acetate consumption during post-exponential growth [59,63–67]. During anaerobic/fermentative growth, up-regulation of ackA-pta expression has been linked to the global anaerobic regulator Anr (Fnr homolog) and integration host factor subunit alpha (lhfA) in bacteria such as Pseudomonas spp. and Neisseria spp. [31,34,66,68], but there are also other known regulators, such as the CrbS/R two-component system [28,29] that controls acetate consumption via ACS, and a LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CidR, for acetate production via the pyruvate:menaquinone oxidoreductase [22,69,70].

While many bacteria can tolerate acetate reasonably well, acetate accumulation can impair growth and inhibit the production of proteins and plasmid DNA [71–76]. This is best studied in Escherichia coli and common human pathogens, Staphylococcus spp. and Pseudomonas spp., where acetate metabolism results in intracellular acidification and respiratory inhibition [22,23,59,60,66,70,76–78]. Additionally, the production of Ac-CoA and acetyl-phosphate can alter protein acetylation non-enzymatically, which has been shown to modulate bacterial virulence and metabolism [79,80].

Acetate is a host cell nutrient involved in epithelial barrier integrity

As in bacteria, acetate is also a host cell nutrient, and its role has been best studied in the tumor microenvironment [81]. Tumor cells show increased glucose uptake and pyruvate formation due to the predominance of ‘Warburg’ metabolism. This results in a metabolic imbalance with excess carbon being directed to lactate and acetate formation via pyruvate decarboxylases or hydrolysis reactions that use protein deacetylases and Ac-CoA hydrolase [4,81].

External acetate, that can be present both in a tumor environment and as a result of microbial action, is transported into mammalian cells by members of the monocarboxylate transporter family, where it can then be converted to Ac-CoA by Ac-CoA synthetases (ACSS) that are present in both mitochondrial (ACSS1) and cytosolic forms (ACSS2) [4,81]. The acetate-derived Ac-CoA can be used for ATP production, protein acetylation via lysine acetyltransferases, and fatty acid synthesis [4,82,83].

In addition to being an energy source, acetate has also been shown to have beneficial effects on epithelial integrity [84,85]. In intestinal epithelial cells, acetate triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which, as shown in nlrp3−/− mice, plays a key role in protection against colitis [86]. Wound healing, tight junction repair, and changes to the actin cytoskeleton can also be induced by acetate [87–90].

Acetate is detected by GPCR-dependent and independent mechanisms

Most molecular effects of acetate are mediated by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), expressed on intestinal enterocytes and other cell types found throughout the body, that can sense environmental acetate [91–95]. Both GPCR43 (also known as free fatty acid receptor (FFA2)) and GPCR41 (also known as FFA3) can sense acetate, but most acetate signaling is mediated by GPCR43 that, unlike GPCR41, binds acetate preferentially over other SCFAs. GPCR-dependent signaling mediates acetate-based chemoattraction [12,92,96,97] but has also been shown to suppress chemoattractant ligands (CCLs) CCL1 and CCL2 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractants (CINC) CINC-1 and CINC-2αβ [88,92,98–101]. Additional mechanisms for sensing acetate are likely to exist, as GPCR43-independent acetate signaling via an as-yet-unknown mechanism has been demonstrated [102].

Acetate affects host cell inflammation through post-translational modification of histones and the NLRP3 inflammasome

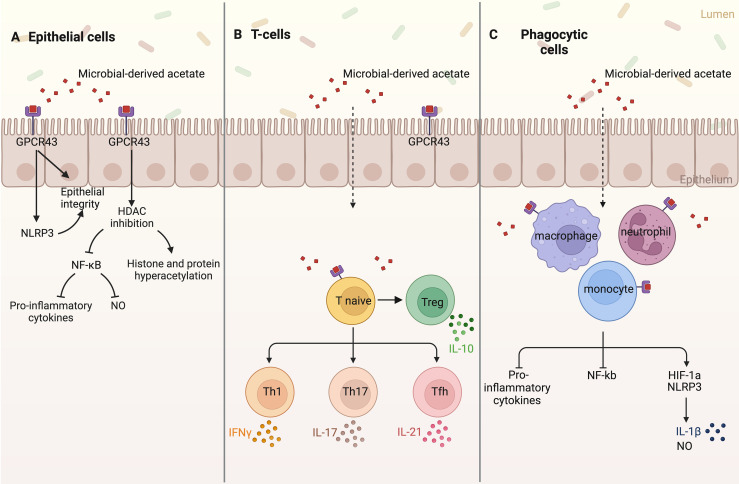

High concentrations of acetate in or around the host cell can result in changes in protein acetylation following Ac-CoA formation via ACSS1/ACSS2 [103–105]. Acetylation is a common post-translational modification on a wide range of histone and non-histone proteins [106–108]. Acetylation of histones changes gene expression [106], while acetylation of non-histone proteins affects their subcellular localization, DNA binding, transcriptional activity, protein–protein interaction, and stability [107,108]. Protein acetylation depends on the formation of Ac-CoA from acetate and is moderated by histone acetylases (HACs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) which are ubiquitously expressed by host cells [18,109,110]. Previously it had been believed that acetate has no HDAC modulatory activity. However, there is increasing evidence that histone hyperacetylation, particularly on histones H3 and H4, may not only be due to increased Ac-CoA concentrations, but is promoted by acetate-mediated inhibition of HDACs [18,109–115]. HDAC inhibition has been linked to NF-κB inactivation and the subsequent suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-18, and IL-6, and nitric oxide (NO) production in different human epithelial cells (Figure 2) [18,88,99,116].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) 43-dependent and independent acetate signaling pathways in host epithelia and immune cells.

(A) Acetate signaling in host epithelial cells triggers NLRP3 and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition, resulting in increased epithelial integrity and wound healing, reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide (NO), and histone and non-histone protein hyperacetylation. (B) Acetate triggers the differentiation of naïve T-cells to T-regulatory (Treg) and T-helper (Th1, Th17, and Tfh) cells, increasing the expression of interferon-gamma (IFNγ), interleukin 17 (IL-17), interleukin 21 (IL-21), and interleukin 10 (IL-10). (C) Phagocytic cells including macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes, after sensing acetate, reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-κβ but increase the expression of NLRP3 and HIF-1α, resulting in increased interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and NO production. This figure was created using BioRender.

This acetate-based suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, primarily TNFα, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18, and NF-κβ activation via HDAC inhibition has been demonstrated in activated macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 2) [18,86,98,102,117–121]. In contrast, HIF-1α and the NLRP3 inflammasome are activated by acetate, particularly lower concentrations (0.2–2 mM), as observed in neutrophils [122], leading to increased IL-1β and NO production (Figure 2) [102,123]. However, NLRP3 expression can be down-regulated by acetate signaling under hypoxic conditions, demonstrating that environmental oxygen availability influences downstream responses to acetate, and this should be investigated further [99,100].

The presence of acetate also increases the production of prostaglandin E [2] (PGE(2)), which can have both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects in neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells [98,124]. Lastly, while acetate appears to have no effect on dendritic cell development and function [125], it has been shown to modulate the function of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells through mTOR activation [110,126,127], PGE(2) up-regulation, and HDAC inhibition, specifically increasing the expression of the anti-inflammatory IL-10 [110,124]. Additionally, acetate aids CD4+ T cell differentiation to Th1 and Th17 effector cells, which results in increased expression of IFN-γ and IL-17, respectively (Figure 2) [110,124].

Acetate modulates inflammation in major microbially colonized organs

Being primarily a microbial-derived metabolite, immunomodulatory effects of acetate generally occur in the host where there is extensive microbial colonization, including major organs such as the skin, oral cavity, gastrointestinal (GI), urogenital and respiratory tracts [128–132]. Acetate-mediated host–microbe interactions are essential for the functioning of several physiological host processes, including tissue development, nutrient absorption and metabolism, and the proper function of the immune system [12]. This has been best studied for the GI tract [87–90].

The nutrient-rich human GI tract is inhabited by complex bacterial communities reaching up to 1011 bacteria/ml in the colon. In healthy individuals, these communities are dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes with lower abundances of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria [128]. Small populations of organisms such as Clostridioides difficile that cause disease if they overgrow may also be present. The predominant acetate-producing bacteria are Bacteroidetes as well as Prevotella spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Akkermansia muciniphila [1]. Acetate produced by these microbes can be used by GI tract inhabiting Firmicutes to produce butyrate, another SCFA [91,92]. The composition of gut bacterial communities can be impacted by host diet, where a high-fibre diet is associated with communities capable of greater SCFA production and other microbial-derived metabolites [133]. In addition to dietary effects, drug treatments such as the administration of antibiotics and host genetic factors can affect the prevalence of acetate-producing microorganisms in the GI tract [86,134].

In healthy hosts, the same immunomodulatory mechanisms that control inflammation in response to the normal microbiota also protect the bowel from invasion by pathogens [135]. In the GI tract, microbial-derived acetate is associated with epithelial maintenance, wound healing, and improved barrier function [87–90]. Acetate also lowers colonic inflammation in mice [19,71,86,136] and has been shown to exert a probiotic effect against enteropathogens [137]. Alterations in the microbial composition, particularly an increase in Proteobacteria and/or Firmicutes, have been linked to multiple pathologies, such as obesity, colorectal cancer, and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). In fact, acetate supplementation has been shown to alleviate the severity of IBD in acetate-fed, germ-free, GPCR43−/− mice and high-fibre diet mouse models [110,133,138].

The healthy skin microbiota have essential roles in protection against pathogens and the breakdown of natural products such as lipids and proteins [139]. Similar to the GI tract, skin microbiota are comprised of bacteria from the same four main phyla, Actinobacteria (36–51%), Firmicutes (24–34%), Proteobacteria (11–16%), and Bacteroidetes (6–9%) [132]. However, in contrast with the GI tract, Bacteroidetes are not dominant in a healthy skin microbiome. The specific composition of the microbiota differs depending on the physiology of the skin site, where, for example, humid skin sites primarily harbor Staphylococcus (Firmicutes) and Corynebacterium (Actinobacteria), while in oily sites, Cutibacterium (Actinobacteria) species are the most common [129,139]. In this environment, microbial-derived acetate, primarily from Cutibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis, can decrease microbial biofilm formation; however, if present in excess, it can drive inflammation observed e.g. in acne [140,141].

In the respiratory tract, the microbiota composition and relative abundance of each microbe are isolation site-specific and reflect the health status and age of the host [142]. However, there are clear differences between the microbiota of the upper and lower respiratory tract (LRT). The upper respiratory tract (URT), which consists of the nasal and oral cavities, harbors commensals and opportunistic pathogens such as Staphylococcus spp., C. acnes, Corynebacterium spp., Moraxella spp., Haemophilus spp., and Dolosigranulum spp. [130,131]. In contrast, in the LRT, Prevotella, Veillonella spp., and Streptococcus spp. are the main bacterial colonizers in healthy individuals [131,143–146]. Opportunistic nasal pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis are less commonly isolated from a healthy LRT, but their presence is associated with diseases such as cystic fibrosis, pneumonia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [142,144–146].

In vitro, acetate can increase the ability of alveolar macrophages to kill bacteria and viruses, such as Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [102,117–119,147–149], i.e. it appeared to show pro-inflammatory rather than anti-inflammatory action in these assays. There are few detailed studies of the effects of acetate on lung microbiota; however, it is known that some common respiratory tract colonizers, such as H. influenzae, produce high amounts of acetate as a metabolic endproduct, while other species, such as Moraxella, use acetate as a preferred carbon source [150–154]. Additionally, increasing acetate concentrations in the LRT have been associated with dysbiosis and proposed to be drivers of persistent neutrophilic inflammation [146]. However, there is also evidence that the cellular effects of acetate can be actively modified by bacteria such as H. influenzae. A recent study showed that acetate (7 mM) had an anti-inflammatory effect on human bronchial cells when live H. influenzae were present, but increased inflammation when the bronchial cells were stimulated antigenically with heat-killed H. influenzae [150]. This suggests that active metabolic interactions between bacteria and epithelial cells may be required for an anti-inflammatory effect [150]. Similar results have also been reported for A549 lung carcinoma cells, where H. influenzae culture supernatants induced a pro-inflammatory response [151]. Given that H. influenzae is a commensal of the human nasopharynx, but not the LRT, one could speculate that in the nasopharynx H. influenzae acetate production is a common process that promotes persistence. In contrast, acetate is an uncommon metabolite in the LRT, and its production by H. influenzae or other microbes then drives dysbiosis and neutrophilic airway inflammation.

Compared with the well-documented role of microbial-derived acetate in the GI tract, the role of acetate and acetate-producing microbiota in the respiratory tract is less defined, with the switch between pro- and anti-inflammatory effects and the dependency on the type of bacterial species present requiring further examination.

Contrary to what has been observed for the human GI tract, skin, and respiratory system, acetate is not associated with a healthy microbiome in the human urogenital tract. Here, lactate is normally present in high concentrations and is produced by a combination of Firmicutes, Lactobacillus and Streptococcus spp., which are the dominant genera of the urogenital tract microbiota [132]. In addition to lactate, small amounts of acetate and succinate have also been observed, and their concentrations increase during disease [155]. During disease, such as neurogenic bladder dysfunction, interstitial cystitis, and urinary tract infection, there is a shift in the microbiota composition, with a particular increase in SCFA-producing bacteria, including Lactobacillus, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus [156,157]. While little is known about the molecular effects of acetate on the epithelia of the urogenital tract, its presence is a consistent disease marker, and the measurement of acetate in vaginal fluid samples has even been suggested as a diagnostic tool for bacterial vaginosis [155].

In summary, while in the GI tract and skin acetate prevents inflammation and promotes the health of the host tissue, the role of microbial-derived acetate in the respiratory tract is ambiguous, and in the urogenital tract, it is a marker for inflammation. Further work is needed, especially in the respiratory and urogenital tract to clarify the association of acetate with disease development.

Microbiota-derived acetate can have systemic effects on the human body

In addition to local effects on individual organ systems, metabolites such as acetate can drive cross-talk between GI tract microbiota and other organs, including the frequently discussed ‘gut-brain axis’ where acetate guides microglial maturation and regulation during disease [111,141,148,158–163]. In other organs, for example, despite evidence that local acetate production in the lung can drive dysbiosis [146], attenuation of allergic airway inflammation was observed in parallel with an increase in the gut of SCFA-producing Bacteroidaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae, particularly Bifidobacterium longum 51A, enhanced by a high-fibre diet [164,165]. Similarly, a reduction in lung tissue injury during bronchopulmonary dysplasia was associated with an increase in gut Ruminococcaceae, known to be important SCFA producers [100]. It has been proposed, based on the studies presented above as well as extensive reviews [160,166–171], that this cross-talk is mediated by SCFAs that originate from the GI tract and circulate systemically, as well as the conditioning of GI tract immune cells by a healthy gut microbiota, resulting in the improved function of the overall immune system.

Conclusions and research gaps

Despite being less studied than the more potent SCFAs, propionate and butyrate, recent studies have documented the importance of acetate homeostasis for maintaining a healthy state, particularly in the GI tract. This is mediated by bidirectional interactions between microbiota, host epithelia, and the host immune system, where, in many contexts, microbial-derived acetate reduced inflammation, improved epithelial barrier function, and increased wound healing capabilities [86–90]. Moreover, acetate, which acts primarily through GPCR43, in many cases, exerts an anti-inflammatory response by suppressing NF-κβ activation and HDAC activity to attenuate downstream production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a wide variety of cell types and may be manipulated by host microbiota.

However, several aspects of these interactions need to be studied in more detail. Most research to date has been performed using in vitro or ex vivo infection models, often using only abiotic stimulation or treatment with exogenous acetate at different concentrations [41,70,102,116,121,149,172]. This makes understanding the systemic effects of acetate, why acetate in the respiratory tract and urogenital tract can be a disease marker, and the complex role of NLRP3 and how it responds to acetate challenging. To overcome this, the development of coculture models that use differentiated primary cells as well as using complex bacterial communities that reflect the in vivo environment and models that include epithelial and immune cells will be essential for future research in this field.

Additionally, while numerous studies explore the role of acetate in disease states for organ systems such as the URT/LRT or the urogenital tract, little is known about the role of acetate in healthy individuals. Particularly intriguing is the currently little-studied molecular basis for the ability of acetate to cause both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects. Similarly, more research is needed on the cross-feeding mechanisms between the gut microbiota and other host organs, and on the therapeutic potential of acetate in different disease models.

Summary

Acetate is an abundant, mostly microbial-derived SCFA in the human body.

Acetate signaling occurs through GPCR43-dependent and independent methods and leads to suppression of HDAC and NF-κβ activity, thus exerting an anti-inflammatory effect.

Despite the overall anti-inflammatory effects of acetate, conditions have been identified where acetate derived from human bacterial pathogens can trigger a pro-inflammatory response.

Microbial-derived SCFAs from the GI tract can have systemic, immunomodulatory effects on other major host organs, including the respiratory tract.

Acknowledgements

J.H. is the recipient of an Australian Commonwealth Government Research Training Program Award and has received additional disability support through the UQ Graduate School and Student Services. Figures were prepared using BioRender.

Abbreviations

- Ac-CoA

acetyl-coenzyme A

- AckA-Pta

acetate kinase and phosphotransacetylase

- ACS

Ac-CoA synthetase

- CCL

chemoattractant ligand

- CINC

cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractants

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GPCRs

G-protein coupled receptors

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- IBD

inflammatory bowel diseases

- LRT

lower respiratory tract

- NO

nitric oxide

- SCFAs

short-chain fatty acids

- URT

upper respiratory tract

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council grants [GNT1043532] and [GNT1158451] to U.K. and A.G.M.

Open Access

Open access for this article was enabled by the participation of the University of Queensland in an all-inclusive Read & Publish agreement with Portland Press and the Biochemical Society under a transformative agreement with CAUL.

Author Contributions

J.H. carried out the literature review, drafting, and editing of all manuscript sections and created the figure. U.K. provided help with the initial conception, structuring of the manuscript, contributed to manuscript writing, and the generation of figures. A.G.M. provided critical analysis of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

References

- 1.Rey, F.E., Faith, J.J., Bain, J., Muehlbauer, M.J., Stevens, R.D., Newgard, C.B.et al. (2010) Dissecting the in vivo metabolic potential of two human gut acetogens. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22082–22090 10.1074/jbc.M110.117713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng, W., Ao, H. and Peng, C. (2018) Gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and herbal medicines. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1354 10.3389/fphar.2018.01354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curiel, J.A., Salvadó, Z., Tronchoni, J., Morales, P., Rodrigues, A.J., Quirós, M.et al. (2016) Identification of target genes to control acetate yield during aerobic fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Factories 15, 156 10.1186/s12934-016-0555-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu, X., Cooper, D.E., Cluntun, A.A., Warmoes, M.O., Zhao, S., Reid, M.A.et al. (2018) Acetate production from glucose and coupling to mitochondrial metabolism in mammals. Cell 175, 502–513.e13 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulaiman, I., Wu, B.G., Li, Y., Tsay, J.C., Sauthoff, M., Scott, A.S.et al. (2021) Functional lower airways genomic profiling of the microbiome to capture active microbial metabolism. Eur. Respir. J. 58, 2003434 10.1183/13993003.03434-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch, A.A., Biesbroek, G., Trzcinski, K., Sanders, E.A. and Bogaert, D. (2013) Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003057 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jama-Kmiecik, A., Frej-Madrzak, M., Sarowska, J. and Choroszy-Krol, I. (2016) Pathogens causing upper respiratory tract infections in outpatients. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 934, 89–93 10.1007/5584_2016_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappelletty, D. (1998) Microbiology of bacterial respiratory infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 17, S55–S61 10.1097/00006454-199808001-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspi, R., Altman, T., Billington, R., Dreher, K., Foerster, H., Fulcher, C.A.et al. (2014) The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D459–D471 10.1093/nar/gkt1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karp, P.D., Weaver, D., Paley, S., Fulcher, C., Kubo, A., Kothari, A.et al. (2014) The EcoCyc database. EcoSal Plus 6. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0009-2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings, J.H., Pomare, E.W., Branch, W.J., Naylor, C.P. and Macfarlane, G.T. (1987) Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 28, 1221–1227 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Correa-Oliveira, R., Fachi, J.L., Vieira, A., Sato, F.T. and Vinolo, M.A. (2016) Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 5, e73 10.1038/cti.2016.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards, R.H., Dowling, J.A., Vreman, H.J., Feldman, C. and Weiner, M.W. (1976) Acetate levels in human plasma. Proc. Clin. Dial. Transplant. Forum. 6, 73–79 PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies, P.G., Venkatesh, B., Morgan, T.J., Presneill, J.J., Kruger, P.S., Thomas, B.J.et al. (2011) Plasma acetate, gluconate and interleukin-6 profiles during and after cardiopulmonary bypass: a comparison of Plasma-Lyte 148 with a bicarbonate-balanced solution. Crit. Care 15, R21 10.1186/cc9966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pomare, E.W., Branch, W.J. and Cummings, J.H. (1985) Carbohydrate fermentation in the human colon and its relation to acetate concentrations in venous blood. J. Clin. Invest. 75, 1448–1454 10.1172/JCI111847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tollinger, C., Vreman, H.J. and Weiner, M.W. (1979) Measurement of acetate in human blood by gas chromatography: effects of sample preparation, feeding, and various diseases. Clin. Chem. 25, 1787–1790 10.1093/clinchem/25.10.1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva, Y.P., Bernardi, A. and Frozza, R.L. (2020) The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 25 10.3389/fendo.2020.00025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinolo, M.A., Rodrigues, H.G., Hatanaka, E., Sato, F.T., Sampaio, S.C. and Curi, R. (2011) Suppressive effect of short-chain fatty acids on production of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils. J. Nutr. Biochem. 22, 849–855 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venegas D, P., De la Fuente, M.K., Landskron, G., Gonzalez, M.J., Quera, R., Dijkstra, G.et al. (2019) Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front. Immunol. 10, 277 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Axe, D.D. and Bailey, J.E. (1995) Transport of lactate and acetate through the energized cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 47, 8–19 10.1002/bit.260470103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero, A.A., Gomez, R.F., Snedecor, B., Tolman, C.J. and Roberts, M.F. (1985) Growth inhibition of Clostridium thermocellum by carboxylic acids: a mechanism based on uncoupling by weak acids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22, 53–62 10.1007/BF00252157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadykov, M.R., Thomas, V.C., Marshall, D.D., Wenstrom, C.J., Moormeier, D.E., Widhelm, T.J.et al. (2013) Inactivation of the Pta-AckA pathway causes cell death in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 195, 3035–3044 10.1128/JB.00042-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall, D.D., Sadykov, M.R., Thomas, V.C., Bayles, K.W. and Powers, R. (2016) Redox imbalance underlies the fitness defect associated with inactivation of the Pta-AckA pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Proteome Res. 15, 1205–1212 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enjalbert, B., Millard, P., Dinclaux, M., Portais, J.C. and Letisse, F. (2017) Acetate fluxes in Escherichia coli are determined by the thermodynamic control of the Pta-AckA pathway. Sci. Rep. 7, 42135 10.1038/srep42135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe, A.J. (2005) The acetate switch. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69, 12–50 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grundy, F.J., Waters, D.A., Allen, S.H. and Henkin, T.M. (1993) Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis acetate kinase gene by CcpA. J. Bacteriol. 175, 7348–7355 10.1128/jb.175.22.7348-7355.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonenshein, A.L. (2007) Control of key metabolic intersections in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 917–927 10.1038/nrmicro1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kretzschmar, U., Khodaverdi, V. and Adrian, L. (2010) Transcriptional regulation of the acetyl-CoA synthetase gene acsA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Microbiol. 192, 685–690 10.1007/s00203-010-0593-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob, K., Rasmussen, A., Tyler, P., Servos, M.M., Sylla, M., Prado, C.et al. (2017) Regulation of acetyl-CoA synthetase transcription by the CrbS/R two-component system is conserved in genetically diverse environmental pathogens. PLoS One 12, e0177825 10.1371/journal.pone.0177825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sepulveda, E. and Lupas, A.N. (2017) Characterization of the CrbS/R two-component system in Pseudomonas fluorescens reveals a new set of genes under its control and a DNA motif required for CrbR-mediated transcriptional activation. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2287 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eschbach, M., Schreiber, K., Trunk, K., Buer, J., Jahn, D. and Schobert, M. (2004) Long-term anaerobic survival of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa via pyruvate fermentation. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4596–4604 10.1128/JB.186.14.4596-4604.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, W., Reitzer, L., Rasko, D.A., Pearson, M.M., Blick, R.J., Laurence, C.et al. (2007) Metabolic analysis of Moraxella catarrhalis and the effect of selected in vitro growth conditions on global gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75, 4959–4971 10.1128/IAI.00073-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speeleveld, E., Fossepre, J.M., Gordts, B. and Van Landuyt, H.W. (1994) Comparison of three rapid methods, tributyrine, 4-methylumbelliferyl butyrate, and indoxyl acetate, for rapid identification of Moraxella catarrhalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32, 1362–1363 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1362-1363.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baart, G.J., Zomer, B., de Haan, A., van der Pol, L.A., Beuvery, E.C., Tramper, J.et al. (2007) Modeling Neisseria meningitidis metabolism: from genome to metabolic fluxes. Genome Biol. 8, R136 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morse, S.A., Stein, S. and Hines, J. (1974) Glucose metabolism in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 120, 702–714 10.1128/jb.120.2.702-714.1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gimenez, R., Nunez, M.F., Badia, J., Aguilar, J. and Baldoma, L. (2003) The gene yjcG, cotranscribed with the gene acs, encodes an acetate permease in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6448–6455 10.1128/JB.185.21.6448-6455.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sa-Pessoa, J., Paiva, S., Ribas, D., Silva, I.J., Viegas, S.C., Arraiano, C.M.et al. (2013) SATP (YaaH), a succinate-acetate transporter protein in Escherichia coli. Biochem. J. 454, 585–595 10.1042/BJ20130412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enjalbert, B., Cocaign-Bousquet, M., Portais, J.C. and Letisse, F. (2015) Acetate exposure determines the diauxic behavior of Escherichia coli during the glucose-acetate transition. J. Bacteriol. 197, 3173–3181 10.1128/JB.00128-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arias-Barrau, E., Olivera, E.R., Sandoval, A., Naharro, G. and Luengo, J.M. (2006) Acetyl-CoA synthetase from Pseudomonas putida U is the only acyl-CoA activating enzyme induced by acetate in this bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 260, 36–46 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kretzschmar, U., Khodaverdi, V., Jeoung, J.H. and Gorisch, H. (2008) Function and transcriptional regulation of the isocitrate lyase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Arch. Microbiol. 190, 151–158 10.1007/s00203-008-0381-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dolan, S.K., Kohlstedt, M., Trigg, S., Vallejo Ramirez, P., Kaminski, C.F., Wittmann, C.et al. (2020) Contextual flexibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa central carbon metabolism during growth in single carbon sources. mBio 11, e02684-19 10.1128/mBio.02684-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castano-Cerezo, S., Pastor, J.M., Renilla, S., Bernal, V., Iborra, J.L. and Canovas, M. (2009) An insight into the role of phosphotransacetylase (pta) and the acetate/acetyl-CoA node in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Factories 8, 54 10.1186/1475-2859-8-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kakuda, H., Hosono, K., Shiroishi, K. and Ichihara, S. (1994) Identification and characterization of the ackA (acetate kinase A)-pta (phosphotransacetylase) operon and complementation analysis of acetate utilization by an ackA-pta deletion mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. 116, 916–922 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumari, S., Beatty, C.M., Browning, D.F., Busby, S.J., Simel, E.J., Hovel-Miner, G.et al. (2000) Regulation of acetyl coenzyme A synthetase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4173–4179 10.1128/JB.182.15.4173-4179.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumari, S., Tishel, R., Eisenbach, M. and Wolfe, A.J. (1995) Cloning, characterization, and functional expression of acs, the gene which encodes acetyl coenzyme A synthetase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2878–2886 10.1128/jb.177.10.2878-2886.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hang, S., Purdy, A.E., Robins, W.P., Wang, Z., Mandal, M., Chang, S.et al. (2014) The acetate switch of an intestinal pathogen disrupts host insulin signaling and lipid metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 16, 592–604 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao, J. and Rock, C.O. (2017) Exogenous fatty acid metabolism in bacteria. Biochimie 141, 30–39 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng, S., Xu, C., Yang, K., Wang, H., Fan, H. and Liao, M. (2017) Either fadD1 or fadD2, which encode acyl-CoA synthetase, is essential for the survival of Haemophilus parasuis SC096. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 72 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li, R., Gu, J., Chen, P., Zhang, Z., Deng, J. and Zhang, X. (2011) Purification and characterization of the acetyl-CoA synthetase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 43, 891–899 10.1093/abbs/gmr076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mochizuki, K., Inaoka, D.K., Mazet, M., Shiba, T., Fukuda, K., Kurasawa, H.et al. (2020) The ASCT/SCS cycle fuels mitochondrial ATP and acetate production in Trypanosoma brucei. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1861, 148283 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tielens, A.G., van Grinsven, K.W., Henze, K., van Hellemond, J.J. and Martin, W. (2010) Acetate formation in the energy metabolism of parasitic helminths and protists. Int. J. Parasitol. 40, 387–397 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muller, M., Mentel, M., van Hellemond, J.J., Henze, K., Woehle, C., Gould, S.B.et al. (2012) Biochemistry and evolution of anaerobic energy metabolism in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 444–495 10.1128/MMBR.05024-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, B., Lingga, C., Bowman, C. and Hackmann, T.J. (2021) A new pathway for forming acetate and synthesizing ATP during fermentation in bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e0295920 10.1128/AEM.02959-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mullins, E.A., Francois, J.A. and Kappock, T.J. (2008) A specialized citric acid cycle requiring succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA):acetate CoA-transferase (AarC) confers acetic acid resistance on the acidophile Acetobacter aceti. J. Bacteriol. 190, 4933–4940 10.1128/jb.00405-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Filatova, L.V., Berg, I.A., Krasil'nikova, E.N., Tsygankov, A.A., Laurinavichene, T.V. and Ivanobsky, R.N. (2005) A study of the mechanism of acetate assimilation in purple nonsulfur bacteria lacking the glyoxylate shunt: acetate assimilation in rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiology 74, 265–269 10.1007/s11021-005-0061-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petushkova, E.P. and Tsygankov, A.A. (2017) Acetate metabolism in the purple non-sulfur bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. Biochemistry 82, 587–605 10.1134/S0006297917050078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tasaki, M., Kamagata, Y., Nakamura, K., Okamura, K. and Minami, K. (1993) Acetogenesis from pyruvate by Desulfotomaculum thermobenzoicum and differences in pyruvate metabolism among three sulfate-reducing bacteria in the absence of sulfate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 106, 259–263 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05973.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Somerville, G.A. and Proctor, R.A. (2009) At the crossroads of bacterial metabolism and virulence factor synthesis in Staphylococci. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 233–248 10.1128/MMBR.00005-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Somerville, G.A., Chaussee, M.S., Morgan, C.I., Fitzgerald, J.R., Dorward, D.W., Reitzer, L.J.et al. (2002) Staphylococcus aureus aconitase inactivation unexpectedly inhibits post-exponential-phase growth and enhances stationary-phase survival. Infect. Immun. 70, 6373–6382 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6373-6382.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patton, T.G., Rice, K.C., Foster, M.K. and Bayles, K.W. (2005) The Staphylococcus aureus cidC gene encodes a pyruvate oxidase that affects acetate metabolism and cell death in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1664–1674 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04653.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warner, J.B. and Lolkema, J.S. (2003) CcpA-dependent carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 475–490 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.475-490.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stulke, J. and Hillen, W. (1999) Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 195–201 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80034-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chang, Y.Y., Wang, A.Y. and Cronan, Jr, J.E. (1994) Expression of Escherichia coli pyruvate oxidase (PoxB) depends on the sigma factor encoded by the rpoS(katF) gene. Mol. Microbiol. 11, 1019–1028 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abdel-Hamid, A.M., Attwood, M.M. and Guest, J.R. (2001) Pyruvate oxidase contributes to the aerobic growth efficiency of Escherichia coli. Microbiology (Reading) 147, 1483–1498 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moreau, P.L. (2004) Diversion of the metabolic flux from pyruvate dehydrogenase to pyruvate oxidase decreases oxidative stress during glucose metabolism in nongrowing Escherichia coli cells incubated under aerobic, phosphate starvation conditions. J. Bacteriol. 186, 7364–7368 10.1128/JB.186.21.7364-7368.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schobert, M. and Jahn, D. (2010) Anaerobic physiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the cystic fibrosis lung. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 549–556 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bergman, J.M., Wrande, M. and Hughes, D. (2014) Acetate availability and utilization supports the growth of mutant sub-populations on aging bacterial colonies. PLoS One 9, e109255 10.1371/journal.pone.0109255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arai, H. (2011) Regulation and function of versatile aerobic and anaerobic respiratory metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2, 00103 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang, S.J., Rice, K.C., Brown, R.J., Patton, T.G., Liou, L.E., Park, Y.H.et al. (2005) A LysR-type regulator, CidR, is required for induction of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC operon. J. Bacteriol. 187, 5893–5900 10.1128/JB.187.17.5893-5900.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rice, K.C., Nelson, J.B., Patton, T.G., Yang, S.J. and Bayles, K.W. (2005) Acetic acid induces expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB murein hydrolase regulator operons. J. Bacteriol. 187, 813–821 10.1128/JB.187.3.813-821.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aristidou, A.A., San, K.Y. and Bennett, G.N. (1995) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli to enhance recombinant protein production through acetate reduction. Biotechnol. Prog. 11, 475–478 10.1021/bp00034a019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waegeman, H., De Lausnay, S., Beauprez, J., Maertens, J., De Mey, M. and Soetaert, W. (2013) Increasing recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli K12 through metabolic engineering. New Biotechnol. 30, 255–261 10.1016/j.nbt.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wong, M.S., Wu, S., Causey, T.B., Bennett, G.N. and San, K.Y. (2008) Reduction of acetate accumulation in Escherichia coli cultures for increased recombinant protein production. Metab. Eng. 10, 97–108 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Borja, G.M., Meza Mora, E., Barron, B., Gosset, G., Ramirez, O.T. and Lara, A.R. (2012) Engineering Escherichia coli to increase plasmid DNA production in high cell-density cultivations in batch mode. Microb. Cell Factories 11, 132 10.1186/1475-2859-11-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cunningham, D.S., Koepsel, R.R., Ataai, M.M. and Domach, M.M. (2009) Factors affecting plasmid production in Escherichia coli from a resource allocation standpoint. Microb. Cell Factories 8, 27 10.1186/1475-2859-8-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pinhal, S., Ropers, D., Geiselmann, J. and de Jong, H. (2019) Acetate metabolism and the inhibition of bacterial growth by acetate. J. Bacteriol. 201, e00147-19 10.1128/jb.00147-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomas, V.C., Sadykov, M.R., Chaudhari, S.S., Jones, J., Endres, J.L., Widhelm, T.J.et al. (2014) A central role for carbon-overflow pathways in the modulation of bacterial cell death. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004205 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Behrends, V., Ryall, B., Zlosnik, J.E., Speert, D.P., Bundy, J.G. and Williams, H.D. (2013) Metabolic adaptations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during cystic fibrosis chronic lung infections. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 398–408 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ren, J., Sang, Y., Qin, R., Su, Y., Cui, Z., Mang, Z.et al. (2019) Metabolic intermediate acetyl phosphate modulates bacterial virulence via acetylation. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 8, 55–69 10.1080/22221751.2018.1558963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Verdin, E. and Ott, M. (2013) Acetylphosphate: a novel link between lysine acetylation and intermediary metabolism in bacteria. Mol. Cell 51, 132–134 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hosios, A.M. and Vander Heiden, M.G. (2014) Acetate metabolism in cancer cells. Cancer Metab. 2, 27 10.1186/s40170-014-0027-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Galdieri, L., Zhang, T., Rogerson, D., Lleshi, R. and Vancura, A. (2014) Protein acetylation and acetyl coenzyme a metabolism in budding yeast. Eukaryot. Cell 13, 1472–1483 10.1128/EC.00189-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shi, L. and Tu, B.P. (2015) Acetyl-CoA and the regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 33, 125–131 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yap, Y.A., McLeod, K.H., McKenzie, C.I., Gavin, P.G., Davalos-Salas, M., Richards, J.L.et al. (2021) An acetate-yielding diet imprints an immune and anti-microbial programme against enteric infection. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 10, e1233 10.1002/cti2.1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakajima, A., Nakatani, A., Hasegawa, S., Irie, J., Ozawa, K., Tsujimoto, G.et al. (2017) The short chain fatty acid receptor GPR43 regulates inflammatory signals in adipose tissue M2-type macrophages. PLoS One 12, e0179696 10.1371/journal.pone.0179696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Macia, L., Tan, J., Vieira, A.T., Leach, K., Stanley, D., Luong, S.et al. (2015) Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat. Commun. 6, 6734 10.1038/ncomms7734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakano, T., Uchiyama, K., Ushiroda, C., Kashiwagi, S., Toyokawa, Y., Mizushima, K.et al. (2020) Promotion of wound healing by acetate in murine colonic epithelial cell via c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35, 1171–1179 10.1111/jgh.14987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hung, K.Y., Wu, S.Y., Pao, H.P., Liao, W.I. and Chu, S.J. (2022) Acetate, a gut bacterial product, ameliorates ischemia-reperfusion induced acute lung injury in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 111, 109136 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lyu, J., Pirooznia, M., Li, Y. and Xiong, J. (2022) The short-chain fatty acid acetate modulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol. Biol. Cell 33, 1–11 10.1091/mbc.E22-02-0066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xiong, J., Kawagishi, H., Yan, Y., Liu, J., Wells, Q.S., Edmunds, L.R.et al. (2018) A metabolic basis for endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol. Cell 69, 689–698.e7 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van der Hee, B. and Wells, J.M. (2021) Microbial regulation of host physiology by short-chain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol. 29, 700–712 10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maslowski, K.M., Vieira, A.T., Ng, A., Kranich, J., Sierro, F., Yu, D.et al. (2009) Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 461, 1282–1286 10.1038/nature08530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brown, A.J., Goldsworthy, S.M., Barnes, A.A., Eilert, M.M., Tcheang, L., Daniels, D.et al. (2003) The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11312–11319 10.1074/jbc.M211609200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brestoff, J.R. and Artis, D. (2013) Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 14, 676–684 10.1038/ni.2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim, S., Kim, J.H., Park, B.O. and Kwak, Y.S. (2014) Perspectives on the therapeutic potential of short-chain fatty acid receptors. BMB Rep. 47, 173–178 10.5483/bmbrep.2014.47.3.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Le Poul, E., Loison, C., Struyf, S., Springael, J.-Y., Lannoy, V., Decobecq, M.-E.et al. (2003) Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25481–25489 10.1074/jbc.m301403200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vinolo, M.A., Ferguson, G.J., Kulkarni, S., Damoulakis, G., Anderson, K., Bohlooly, Y.M.et al. (2011) SCFAs induce mouse neutrophil chemotaxis through the GPR43 receptor. PLoS One 6, e21205 10.1371/journal.pone.0021205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cox, M.A., Jackson, J., Stanton, M., Rojas-Triana, A., Bober, L., Laverty, M.et al. (2009) Short-chain fatty acids act as antiinflammatory mediators by regulating prostaglandin E(2) and cytokines. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 5549–5557 10.3748/wjg.15.5549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xu, M., Jiang, Z., Wang, C., Li, N., Bo, L., Zha, Y.et al. (2019) Acetate attenuates inflammasome activation through GPR43-mediated Ca2+-dependent NLRP3 ubiquitination. Exp. Mol. Med. 51, 1–13 10.1038/s12276-019-0276-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang, Q., Ran, X., He, Y., Ai, Q. and Shi, Y. (2020) Acetate downregulates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and attenuates lung injury in neonatal mice with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front. Pediatr. 8, 595157 10.3389/fped.2020.595157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Halnes, I., Baines, K.J., Berthon, B.S., MacDonald-Wicks, L.K., Gibson, P.G. and Wood, L.G. (2017) Soluble fibre meal challenge reduces airway inflammation and expression of GPR43 and GPR41 in asthma. Nutrients 9, 57 10.3390/nu9010057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Machado, M.G., Patente, T.A., Rouille, Y., Heumel, S., Melo, E.M., Deruyter, L.et al. (2022) Acetate improves the killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae by alveolar macrophages via NLRP3 inflammasome and glycolysis-HIF-1alpha axis. Front. Immunol. 13, 773261 10.3389/fimmu.2022.773261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ariyannur, P.S., Moffett, J.R., Madhavarao, C.N., Arun, P., Vishnu, N., Jacobowitz, D.M.et al. (2010) Nuclear-cytoplasmic localization of acetyl coenzyme a synthetase-1 in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 518, 2952–2977 10.1002/cne.22373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fujino, T., Kondo, J., Ishikawa, M., Morikawa, K. and Yamamoto, T.T. (2001) Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2, a mitochondrial matrix enzyme involved in the oxidation of acetate. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11420–11426 10.1074/jbc.M008782200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xu, W.J., Wen, H., Kim, H.S., Ko, Y.J., Dong, S.M., Park, I.S.et al. (2018) Observation of acetyl phosphate formation in mammalian mitochondria using real-time in-organelle NMR metabolomics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 4152–4157 10.1073/pnas.1720908115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Strahl, B.D. and Allis, C.D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403, 41–45 10.1038/47412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Glozak, M.A., Sengupta, N., Zhang, X. and Seto, E. (2005) Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene 363, 15–23 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Polevoda, B. and Sherman, F. (2002) The diversity of acetylated proteins. Genome Biol. 3, reviews0006 10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-reviews0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Waldecker, M., Kautenburger, T., Daumann, H., Busch, C. and Schrenk, D. (2008) Inhibition of histone-deacetylase activity by short-chain fatty acids and some polyphenol metabolites formed in the colon. J. Nutr. Biochem. 19, 587–593 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Park, J., Kim, M., Kang, S.G., Jannasch, A.H., Cooper, B., Patterson, J.et al. (2015) Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 80–93 10.1038/mi.2014.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Soliman, M.L., Smith, M.D., Houdek, H.M. and Rosenberger, T.A. (2012) Acetate supplementation modulates brain histone acetylation and decreases interleukin-1beta expression in a rat model of neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 51 10.1186/1742-2094-9-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kasubuchi, M., Hasegawa, S., Hiramatsu, T., Ichimura, A. and Kimura, I. (2015) Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients 7, 2839–2849 10.3390/nu7042839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bolduc, J.F., Hany, L., Barat, C., Ouellet, M. and Tremblay, M.J. (2017) Epigenetic metabolite acetate inhibits class I/II histone deacetylases, promotes histone acetylation, and increases HIV-1 integration in CD4(+) T cells. J. Virol. 91, e01943-16 10.1128/jvi.01943-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li, M., van Esch, B., Henricks, P.A.J., Folkerts, G. and Garssen, J. (2018) The anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on lipopolysaccharide- or tumor necrosis factor alpha-stimulated endothelial cells via activation of GPR41/43 and inhibition of HDACs. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 533 10.3389/fphar.2018.00533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Olaniyi, K.S. and Amusa, O.A. (2020) Sodium acetate-mediated inhibition of histone deacetylase alleviates hepatic lipid dysregulation and its accompanied injury in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 128, 110226 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Masui, R., Sasaki, M., Funaki, Y., Ogasawara, N., Mizuno, M., Iida, A.et al. (2013) G protein-coupled receptor 43 moderates gut inflammation through cytokine regulation from mononuclear cells. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 19, 2848–2856 10.1097/01.mib.0000435444.14860.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Antunes, K.H., Fachi, J.L., de Paula, R., da Silva, E.F., Pral, L.P., Dos Santos, A.A.et al. (2019) Microbiota-derived acetate protects against respiratory syncytial virus infection through a GPR43-type 1 interferon response. Nat. Commun. 10, 3273 10.1038/s41467-019-11152-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Antunes, K.H., Singanayagam, A., Williams, L., Faiez, T.S., Farias, A., Jackson, M.M.et al. (2022) Airway-delivered short-chain fatty acid acetate boosts antiviral immunity during rhinovirus infection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 151, 447–457 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Antunes, K.H., Stein, R.T., Franceschina, C., da Silva, E.F., de Freitas, D.N., Silveira, J.et al. (2022) Short-chain fatty acid acetate triggers antiviral response mediated by RIG-I in cells from infants with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. EBioMedicine 77, 103891 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tedelind, S., Westberg, F., Kjerrulf, M. and Vidal, A. (2007) Anti-inflammatory properties of the short-chain fatty acids acetate and propionate: a study with relevance to inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 2826 10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ang, Z., Er, J.Z., Tan, N.S., Lu, J., Liou, Y.C., Grosse, J.et al. (2016) Human and mouse monocytes display distinct signalling and cytokine profiles upon stimulation with FFAR2/FFAR3 short-chain fatty acid receptor agonists. Sci. Rep. 6, 34145 10.1038/srep34145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mirmonsef, P., Zariffard, M.R., Gilbert, D., Makinde, H., Landay, A.L. and Spear, G.T. (2012) Short-chain fatty acids induce pro-inflammatory cytokine production alone and in combination with toll-like receptor ligands. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 67, 391–400 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01089.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Park, J.W., Kim, H.Y., Kim, M.G., Jeong, S., Yun, C.H. and Han, S.H. (2019) Short-chain fatty acids inhibit Staphylococcal lipoprotein-induced nitric oxide production in murine macrophages. Immune Netw. 19, e9 10.4110/in.2019.19.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yao, C., Sakata, D., Esaki, Y., Li, Y., Matsuoka, T., Kuroiwa, K.et al. (2009) Prostaglandin E2–EP4 signaling promotes immune inflammation through TH1 cell differentiation and TH17 cell expansion. Nat. Med. 15, 633–640 10.1038/nm.1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Singh, N., Thangaraju, M., Prasad, P.D., Martin, P.M., Lambert, N.A., Boettger, T.et al. (2010) Blockade of dendritic cell development by bacterial fermentation products butyrate and propionate through a transporter (Slc5a8)-dependent inhibition of histone deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27601–27608 10.1074/jbc.M110.102947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Seljeset, S. and Siehler, S. (2012) Receptor-specific regulation of ERK1/2 activation by members of the “free fatty acid receptor” family. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. 32, 196–201 10.3109/10799893.2012.692118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Thorburn, A.N., Macia, L. and Mackay, C.R. (2014) Diet, metabolites, and “western-lifestyle” inflammatory diseases. Immunity 40, 833–842 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Iraporda, C., Errea, A., Romanin, D.E., Cayet, D., Pereyra, E., Pignataro, O.et al. (2015) Lactate and short chain fatty acids produced by microbial fermentation downregulate proinflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells and myeloid cells. Immunobiology 220, 1161–1169 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Carmona-Cruz, S., Orozco-Covarrubias, L. and Sáez-de-Ocariz, M. (2022) The human skin microbiome in selected cutaneous diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 834135 10.3389/fcimb.2022.834135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kumpitsch, C., Koskinen, K., Schöpf, V. and Moissl-Eichinger, C. (2019) The microbiome of the upper respiratory tract in health and disease. BMC Biol. 17, 87 10.1186/s12915-019-0703-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yatera, K., Noguchi, S. and Mukae, H. (2018) The microbiome in the lower respiratory tract. Respir. Investig. 56, 432–439 10.1016/j.resinv.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Aragón, I.M., Herrera-Imbroda, B., Queipo-Ortuño, M.I., Castillo, E., Del Moral, J.S.-G., Gómez-Millán, J.et al. (2018) The urinary tract microbiome in health and disease. Eur. Urol. Focus 4, 128–138 10.1016/j.euf.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lobionda, S., Sittipo, P., Kwon, H.Y. and Lee, Y.K. (2019) The role of Gut microbiota in intestinal inflammation with respect to diet and extrinsic stressors. Microorganisms 7, 271 10.3390/microorganisms7080271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Al Bander, Z., Nitert, M.D., Mousa, A. and Naderpoor, N. (2020) The gut microbiota and inflammation: an overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 7618 10.3390/ijerph17207618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cheng, H.-Y., Ning, M.-X., Chen, D.-K. and Ma, W.-T. (2019) Interactions between the gut microbiota and the host innate immune response against pathogens. Front. Immunol. 10, 607 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cait, A., Hughes, M.R., Antignano, F., Cait, J., Dimitriu, P.A., Maas, K.R.et al. (2018) Microbiome-driven allergic lung inflammation is ameliorated by short-chain fatty acids. Mucosal Immunol. 11, 785–795 10.1038/mi.2017.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fukuda, S., Toh, H., Hase, K., Oshima, K., Nakanishi, Y., Yoshimura, K.et al. (2011) Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature 469, 543–547 10.1038/nature09646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Deleu, S., Machiels, K., Raes, J., Verbeke, K. and Vermeire, S. (2021) Short chain fatty acids and its producing organisms: an overlooked therapy for IBD? EBioMedicine 66, 103293 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Byrd, A.L., Belkaid, Y. and Segre, J.A. (2018) The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 143–155 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Claesen, J., Spagnolo, J.B., Ramos, S.F., Kurita, K.L., Byrd, A.L., Aksenov, A.A.et al. (2020) A Cutibacterium acnes antibiotic modulates human skin microbiota composition in hair follicles. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaay5445 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay5445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chinnappan, M. and Harris-Tryon, T.A. (2021) Novel mechanisms of microbial crosstalk with skin innate immunity. Exp. Dermatol. 30, 1484–1495 10.1111/exd.14429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Huffnagle, G.B., Dickson, R.P. and Lukacs, N.W. (2017) The respiratory tract microbiome and lung inflammation: a two-way street. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 299–306 10.1038/mi.2016.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Dickson, R.P., Erb-Downward, J.R., Martinez, F.J. and Huffnagle, G.B. (2016) The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 481–504 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Li K-J, Chen Z-L, Huang Y, Zhang R, Luan X-Q, Lei T-T, et al. (2019) Dysbiosis of lower respiratory tract microbiome are associated with inflammation and microbial function variety. Respir. Res. 20, 272 10.1186/s12931-019-1246-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Campbell, C.D., Barnett, C. and Sulaiman, I. (2022) A clinicians’ review of the respiratory microbiome. Breathe (Sheff) 18, 210161 10.1183/20734735.0161-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Natalini, J.G., Singh, S. and Segal, L.N. (2022) The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 222–235 10.1038/s41579-022-00821-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Schlatterer, K., Beck, C., Schoppmeier, U., Peschel, A. and Kretschmer, D. (2021) Acetate sensing by GPR43 alarms neutrophils and protects from severe sepsis. Commun. Biol. 4, 928 10.1038/s42003-021-02427-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sencio, V., Barthelemy, A., Tavares, L.P., Machado, M.G., Soulard, D., Cuinat, C.et al. (2020) Gut dysbiosis during influenza contributes to pulmonary pneumococcal superinfection through altered short-chain fatty acid production. Cell Rep. 30, 2934–2947.e6 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Galvão, I., Tavares, L.P., Corrêa, R.O., Fachi, J.L., Rocha, V.M., Rungue, M.et al. (2018) The metabolic sensor GPR43 receptor plays a role in the control of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in the lung. Front. Immunol. 9, 142 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hosmer, J., Nasreen, M., Dhouib, R., Essilfie, A.T., Schirra, H.J., Henningham, A.et al. (2022) Access to highly specialized growth substrates and production of epithelial immunomodulatory metabolites determine survival of Haemophilus influenzae in human airway epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010209 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.López-López, N., Euba, B., Hill, J., Dhouib, R., La, C., Leiva, J.et al. (2020) Haemophilus influenzae glucose catabolism leading to production of the immunometabolite acetate has a key contribution to the host airway–pathogen interplay. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 406–421 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Muda, N.M., Nasreen, M., Dhouib, R., Hosmer, J., Hill, J., Mahawar, M.et al. (2019) Metabolic analyses reveal common adaptations in two invasive Haemophilus influenzae strains. Pathog. Dis. 77, ftz015 10.1093/femspd/ftz015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Easton, D.M., Maier, E., Benz, R., Foxwell, A.R., Cripps, A.W. and Kyd, J.M. (2008) Moraxella catarrhalis M35 is a general porin that is important for growth under nutrient-limiting conditions and in the nasopharynges of mice. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7994–8002 10.1128/jb.01039-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Spaniol, V., Wyder, S. and Aebi, C. (2013) RNA-Seq-based analysis of the physiologic cold shock-induced changes in Moraxella catarrhalis gene expression. PLoS One 8, e68298 10.1371/journal.pone.0068298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Baldewijns, S., Sillen, M., Palmans, I., Vandecruys, P., Van Dijck, P. and Demuyser, L. (2021) The role of fatty acid metabolites in vaginal health and disease: application to candidiasis. Front. Microbiol. 12, 705779 10.3389/fmicb.2021.705779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Whiteside, S.A., Razvi, H., Dave, S., Reid, G. and Burton, J.P. (2015) The microbiome of the urinary tract—a role beyond infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 12, 81–90 10.1038/nrurol.2014.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Flores-Mireles, A.L., Walker, J.N., Caparon, M. and Hultgren, S.J. (2015) Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 269–284 10.1038/nrmicro3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Du, Y., Gao, X.R., Peng, L. and Ge, J.F. (2020) Crosstalk between the microbiota-gut-brain axis and depression. Heliyon 6, e04097 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Srikanth, C.V. and McCormick, B.A. (2008) Interactions of the intestinal epithelium with the pathogen and the indigenous microbiota: a three-way crosstalk. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2008, 626827 10.1155/2008/626827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Zhang, D., Li, S., Wang, N., Tan, H.-Y., Zhang, Z. and Feng, Y. (2020) The cross-talk between Gut microbiota and lungs in common lung diseases. Front. Microbiol. 11, 301 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Ma, W., Nguyen, L.H., Song, M., Wang, D.D., Franzosa, E.A., Cao, Y.et al. (2021) Dietary fiber intake, the gut microbiome, and chronic systemic inflammation in a cohort of adult men. Genome Med. 13, 102 10.1186/s13073-021-00921-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Trompette, A., Pernot, J., Perdijk, O., Alqahtani, R.A.A., Domingo, J.S., Camacho-Muñoz, D.et al. (2022) Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids modulate skin barrier integrity by promoting keratinocyte metabolism and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 15, 908–926 10.1038/s41385-022-00524-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Erny, D., Dokalis, N., Mezö, C., Castoldi, A., Mossad, O., Staszewski, O.et al. (2021) Microbiota-derived acetate enables the metabolic fitness of the brain innate immune system during health and disease. Cell Metab. 33, 2260–76.e7 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Mendes, E., Acetturi, B.G., Thomas, A.M., FdS, M., Crisma, A.R., Murata, G.et al. (2017) Prophylactic supplementation of Bifidobacterium longum 51A protects mice from ovariectomy-induced exacerbated allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1732 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Trompette, A., Gollwitzer, E.S., Yadava, K., Sichelstiel, A.K., Sprenger, N., Ngom-Bru, C.et al. (2014) Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 20, 159–166 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Shastry, R.P. and Rekha, P.D. (2021) Bacterial cross talk with gut microbiome and its implications: a short review. Folia Microbiol. 66, 15–24 10.1007/s12223-020-00821-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Clemmensen, C., Müller, T.D., Woods, S.C., Berthoud, H.R., Seeley, R.J. and Tschöp, M.H. (2017) Gut-brain cross-talk in metabolic control. Cell 168, 758–774 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Ma, Y., Liu, X. and Wang, J. (2022) Small molecules in the big picture of gut microbiome-host cross-talk. EBioMedicine 81, 104085 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Ghezzi, L., Cantoni, C., Rotondo, E. and Galimberti, D. (2022) The gut microbiome-brain crosstalk in neurodegenerative diseases. Biomedicines 10, 1486 10.3390/biomedicines10071486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Tlaskalová-Hogenová, H., Štěpánková, R., Kozáková, H., Hudcovic, T., Vannucci, L., Tučková, L.et al. (2011) The role of gut microbiota (commensal bacteria) and the mucosal barrier in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and cancer: contribution of germ-free and gnotobiotic animal models of human diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 8, 110–120 10.1038/cmi.2010.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Lukiw, W.J. (2020) Gastrointestinal (GI) tract microbiome-derived neurotoxins—potent neuro-inflammatory signals from the GI tract via the systemic circulation into the brain. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 22 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Davie, J.R. (2003) Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J. Nutr. 133, 2485S–2493S 10.1093/jn/133.7.2485s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]